1 Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are primarily released into the environment by oil spills and incomplete combustion (Sojinu et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2020). Since the presence of these chemical substances causes a significant concern due to their ubiquitous impacts on human health (Mallah et al., 2022), many published research articles have recently been devoted to the occurrence, fate, and associated human health risks of PAHs in the environment (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| No. | Reference | Unitsa | ΣPAHs (ppb) | CSb or TEQb (ppb) | Sample matrix | Csc taken | ILCRd | ILCRe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhang et al. (2019) | mg/kg | 9329 | n.a | urban soil | UCL(90%) | 4.9 × 10−6 | 6.49 × 10−6 |

| 2 | Tarafdar and Sinha (2019) | mg/kg | n.a | 1656 | roadside dust | mean | 1.823 × 10−5 | 1.37 × 10−5 |

| 3 | Priya Ghosh and Maiti (2020) | mg/kg | 1478 | n.a | roadside soil | mean | 1.237 × 10−6 | 1.34 × 10−6 |

| 4 | Qi et al. (2020) | mg/kg | 137 | n.a | soil | mean | 4.77 × 10−6 | 1.99 × 10−7 |

| 5 | Qu et al. (2020) | mg/kg | 460 | 49 | park soil | mean | 1.84 × 10−7 | 1.86 × 10−7 |

| 6 | Zhang et al. (2020) | mg/kg | 499.47 | 20.59 | urban soil | mean | 0.85 × 10−4 | 3.88 × 10−8 |

| 7 | Zhang et al. (2021) | mg/kg | 58.12 | n.a | soil | mean | 4.11 × 10−8 | 8.45 × 10−8 |

| 8 | Siemering and Thiboldeaux (2021) | mg/kg | 2060 | n.a | urban soil | UCL(95%) | 1.67 × 10−6 | 1.88 × 10−6 |

| 9 | Ailijiang et al. (2022) | mg/kg | 3304 | 733 | park soil | mean | 2.783 × 10−6 | 2.73 × 10−6 |

| 10 | Wu et al. (2023) | mg/kg | 149.63 | 14.71 | soil | mean | 4.67 × 10−8 | 1.53 × 10−7 |

| 11 | Tanić et al. (2023) | mg/kg | 55 | n.a | park soil | UCL(95%) | 5.5 × 10−9 | 1.50 × 10−8 |

| 12 | Wang et al. (2024) | mg/kg | 278.91 | n.a | soil | mean | 2.1 × 10−8 | 2.41 × 10−7 |

| 13 | Sun et al. (2024) | mg/kg | 56,420 | 4650 | soil | mean | 1.46 × 10−5 | 3.25 × 10−5 |

| 14 | Wang et al. (2011) | μg/kg | 4800 | 548 | urban dust | UCL(95%) | 2.92 × 10−6 | 4.53 × 10−6 |

| 15 | Chen et al. (2013) | μg/kg | 8171 | n.a | roadside soil | mean | 2.37 × 10−5 | 1.22 × 10−5 |

| 16 | Jiang et al. (2014) | μg/kg | 4630 | 300 | street dust | mean | 1.93 × 10−6 | 2.48 × 10−6 |

| 17 | Soltani et al. (2015) | μg/kg | 1074.58 | 90.88 | road dust | mean | 4.85 × 10−4 | 4.85 × 10−7 |

| 18 | Gereslassie et al. (2018) | μg/kg | 138.72 | 34.55 | soil | mean | 3.5 × 10−6 | 2.68 × 10−6 |

| 19 | Najmeddin et al. (2018) | μg/kg | 2183 | 128.49 | street dust | mean | 6.2 × 10−4 | 2.58 × 10−7 |

| 20 | Wang et al. (2018) | μg/kg | 2052.6 | 423.86 | urban soil | mean | 2.53 × 10−5 | 1.41 × 10−5 |

| 21 | Parra et al. (2020) | μg/kg | 2211 | 307.4 | soil | mean | 3.64 × 10−3 | 3.85 × 10−6 |

| 22 | Mohamadian Geravand et al. (2022) | μg/kg | 557.73 | 19.311 | street dust | mean | 5.52 × 10−5 | 1.53 × 10−7 |

| 23 | Roy et al. (2022) | μg/kg | 13,124 | 1930 | railroad soil | max | 3.81 × 10−5 | 3.09 × 10−5 |

| 24 | He et al. (2023) | μg/kg | 629.83 | 93.65 | urban soil | mean | 1.23 × 10−6 | 1.23 × 10−6 |

| 25 | Odali et al. (2023) | μg/kg | 9810 | 2180 | indoor dust | mean | 4.61 × 10−1 | 2.01 × 10−5 |

| 26 | Ali et al. (2017) | ng/g | 14,200 | 305 | workshop dust | mean | 2.54 × 10−3 | 1.49 × 10−6 |

| 27 | Hu et al. (2017) | ng/g | 463.08 | 32.34 | soil | max | 1.53 × 10−6 | 4.02 × 10−7 |

| 28 | Ke et al. (2017) | ng/g | 890.85 | n.a | park soil | max | 1.13 × 10−2 | 1.25 × 10−5 |

| 29 | Fu et al. (2018) | ng/g | 733.5 | n.a | soil | max | 8.81 × 10−4 | 2.26 × 10−6 |

| 30 | Gope et al. (2018) | ng/g | 9688 | 1422 | street dust | max | 1.5 × 10−5 | 1.56 × 10−5 |

| 31 | Ghanavati et al. (2019) | ng/g | 11,766 | 951 | street dust | max | 5.07 × 10−3 | 5.08 × 10−6 |

| 32 | Dreij et al. (2020) | ng/g | 5466 | n.a | park soil | mean | 4.06 × 10−5 | 1.35 × 10−5 |

| 33 | Gope et al. (2020) | ng/g | 5491 | 693 | street dust | max | 3.4 × 10−6 | 7.62 × 10−6 |

| 34 | Mihankhah et al. (2020) | ng/g | 566 | 36.4 | urban dust | mean | 2.89 × 10−4 | 2.89 × 10−7 |

| 35 | Apiratikul et al. (2021) | ng/g | 4376.93 | 661.03 | urban soil | max | 7.57 × 10−6 | 7.87 × 10−6 |

| 36 | Besis et al. (2021) | ng/g | 4650 | 838 | house dust | median | 9.20 × 10−7 | 1.94 × 10−6 |

| 37 | Jia et al. (2021) | ng/g | 688 | n.a | soil | mean | 2.37 × 10−7 | 2.06 × 10−7 |

| 38 | Shi et al. (2021) | ng/g | 932 | 124 | soil | mean | n.a | 3.19 × 10−7 |

| 39 | Cai et al. (2022) | ng/g | 219 | n.a | soil | mean | 10–6–10–5 | 1.81 × 10−6 |

| 40 | Shukla et al. (2022) | ng/g | 3748.23 | 647.9 | roadside soil | mean | 6.2 × 10−3 | 6.17 × 10−6 |

| 41 | Zhang et al. (2022) | ng/g | 508.41 | n.a | outdoor soil | mean | 1.91 × 10−5 | 6.46 × 10−7 |

| 42 | Bigović et al. (2022) | ng/g | 271.49 | 21.7 | agricultural soil | mean | 1.59 × 10−5 | 2.30 × 10−7 |

| 43 | Wu et al. (2022) | ng/g | 2673 | 268 | road dust | mean | 1.43 × 10−6 | 1.43 × 10−6 |

| 44 | Ambade et al. (2023) | ng/g | 5867.4 | n.a | urban soil | mean | 1.56 × 10−7 | 7.46 × 10−6 |

| 45 | Grmasha et al. (2023) | ng/g | 9723.9 | 1933 | sediment | max | 1.53 × 10−2 | 1.53 × 10−5 |

| 46 | Liang et al. (2023) | ng/g | 434 | 110 | park soil | median | 1.09 × 10−7 | 5.57 × 10−7 |

| 47 | Miao et al. (2023) | ng/g | 593.39 | n.a | sediment | max | 7.35 × 10−4 | 1.29 × 10−6 |

| 48 | Cui et al. (2023) | ng/g | 2441.29 | 213.61 | soil | mean | 8.05 × 10−6 | 3.38 × 10−6 |

| 49 | Sankar et al. (2023) | ng/g | 3256.74 | 430.51 | soil | mean | 3.67 × 10−3 | 3.64 × 10−6 |

| 50 | Gbeddy et al. (2020) | g/g | n.a | 492 | road dust | mean | 1.51 × 10−5 | 2.62 × 10−6 |

PAH concentration levels in soil, sediment, and road/indoor dust and ILCR values derived.

The carcinogenic risk of PAHs is significant as exposure to these compounds has been linked to an increased risk of developing cancer, i.e., increased incidences of lung, skin, and bladder cancers, which are associated with occupational exposure to PAHs (Mallah et al., 2022). Therefore, cancer health risk assessment (HRA) for PAHs is a critical tool for safeguarding public health by quantifying risk, identifying vulnerable populations, guiding environmental regulations, and evaluating intervention efficacy (Hussain et al., 2018).

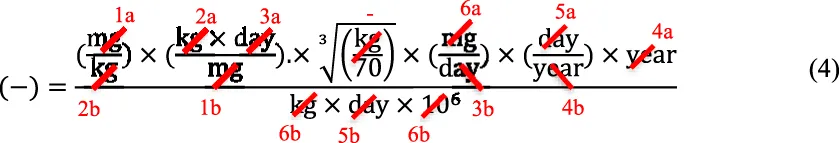

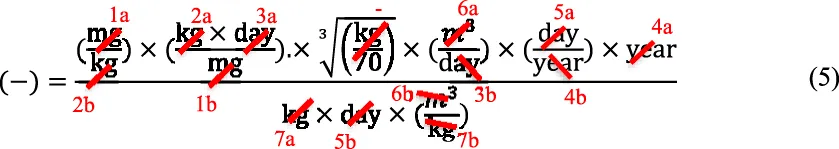

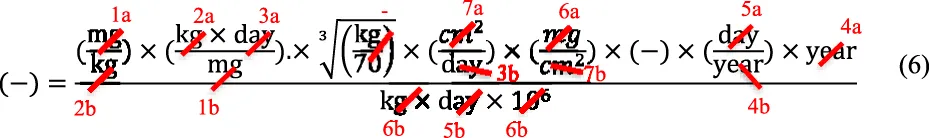

A modern approach to HRA includes a variety of methods (Zhou et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). In any case, the equations that connect the cancer risk index with the concentration levels of PAHs, the duration of exposure, and the frequency of exposure are the basis for risk assessment (Grellier et al., 2015). The vast majority of researchers in the HRA of PAHs in soil and related media (sediment, road dust, and indoor dust) use the USEPA based methodology (USEPA, 1991) for incremental lifetime cancer risk (ILCR) assessment due to exposure to PAHs through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal routes. This exposure is quantified using the following equations:where Cs is the sum of converted PAH concentrations according to toxic equivalents (TEF) of benzo (a) pyrene (BaP) (also reffered to as BaP-TEQ or TEQ), while the exposure factors and their most frequently used values for are as follows: CSFIngestion, CSFInhalation, and CSFDermal are the carcinogenic slope factors of BaP and are 7.3, 3.85, and 25 (kg × day)/mg, respectively; BW is body weight assumed to be 15 kg for children and 70 kg for adults; AT is the average time for carcinogenic effects 70 years × 365 days = 25,550 days; the EF value of 350 days/year is exposure frequency for children and adults; ED is exposure duration (24 years for adults and 6 years for children); IRIngestion is the soil/sediment/dust intake rate at 100 mg/day for adults and 200 mg/day for children; IRInhalation is the inhalation rate (20 m3/day for adults and 10 m3/day for children); SA is the dermal surface exposure (5,700 cm2/day for adults and 2,800 cm2/day for children); AF is the dermal adherence factor (0.07 mg/cm2) for adults and (0.2 mg/cm2) for children; ABS value of 0.13 (unitless) is the absorption efficiency factor of PAHs by the human body through dermal contact of soil particles; PEF is the particle emission factor (1.36 × 109 m3/kg). The aggregate ILCR is the sum of all three ILCR routes.

Eqs 1–3 were used in all cited references in Table 1, except for the correction term , which was omitted in some articles. This term has little influence on the calculated ILCR. Nevertheless, when performing the ILCR for adults and taking the BW to be 70 kg, then is reduced to number one. In the equations for the ingestion and inhalation routes, sometimes, instead of 106, a conversion factor (CF) is written, which has the same value. The exposure factor values for some of the parameters differ depending on the receptor type (resident, worker, recreator, etc.), age and gender, or location in the world. In many articles, the impact of PAHs on residents divided into two age groups (adults and children) has been evaluated.

The concentrations of PAHs in soil are typically measured using gas chromatographic separation of individual PAHs followed by quantification of the separated PAHs by mass spectrometry (Soursou et al., 2023). These concentrations are expressed as the mass of an individual PAH (nanograms, micrograms, or milligrams) per soil mass (gram or kilogram), i.e., ng/g, μg/kg, or mg/kg. Also, units written as parts per billion (ppb) or parts per million (ppm) may be encountered.

Having analyzed the published works on the presence of PAHs in the soil, sediment, and road/indoor dust and the associated risk, inconsistencies were encountered in the expression of the concentration levels of PAHs in Eqs 1–3 and the results of the health risk estimates derived. Namely, a critical problem among some published articles arises from the use of different units for the concentration values (Cs) of PAHs in soil, sediment, and/or dust.

2 Dimensional analysis

In addition to published articles in which the concentration of PAHs in Eqs 1–3 was expressed in mg/kg (ppm) (Refs. 1–13 in Table 1); there are a significant number of articles published in reputable international journals in which the concentrations in these equations are expressed in μg/kg (ppb) (Refs. 14–25, Table 1) or ng/g (ppb) (Refs. 26–49, Table 1); and there is one case where the concentration is expressed in g/g (Ref. 50, Table 1) without correctly matching/converting the units of the remaining variables/constants in the equations. Because of these disparities in the units for Cs in Eqs 1–3, the estimated human health risk may be tremendously different.

This article aims to clarify this issue. If we start from the fact that, except for concentration (Cs), there is a consensus in units for all other exposure factors in Eqs 1–3, a simple dimensional analysis can resolve this dilemma. This analysis is shown in Eqs 4–6.

On the left side of Eqs 4–6, we have ILCR, which is a unitless quantity, and on the right side, identical units have been crossed out according to the following methodology: 1a crosses out 1b, 2a crosses out 2b, 3a crosses out 3b, and so on. The conversion of mg to kg in Eqs 1, 3 is made using the conversion factor (106 value).

When Cs is expressed in mg/kg in the equations, this method of subtraction results in the unitless final value on the right side of the equation. Conversely, if the concentration is expressed in μg/kg or ng/g, the dimensional analysis cannot equate the left and right sides of the equations. Based on this, it is correct to express the concentration of PAHs in the soil, sediment, and dust as mg/kg.

A good example is the case where we would have a BaP-TEQ concentration of 600 μg BaP/kg, which is the Canadian soil quality guide value for PAHs (CCME, 2010). Calculated the total ILCR, using the aforementioned exposure factors, for 0.6 mg BaP/kg in Eqs 1–3 equals 5.71 × 10−6, which is an acceptable cancer health risk with caution. However, if we take 600 μg BaP/kg in Eqs 1–3 without any unit corrections, we will get ILCR = 5.71 × 10−3. The latter is an unacceptable risk that requires urgent action.

3 Comparison of the risk assessment results

In line with the above example, the ILCR values from the cited articles were recalculated and compared with the reported ILCR values in the same articles. When the exposure factor values in the cited articles were not reported, the ILCR values were recalculated using the exposure factor values mentioned above.

Because some articles did not report TEQ values, an option that could have been taken was the worst possible case scenario (TEQ = ΣPAHs). However, this option was ruled out because the worst-case scenario was unrealistic. Instead, the TEQ values were approximated as a fraction of ΣPAHs, considering the data in Table 1. Thus, a fraction of 0.13 was derived as the average fraction of ΣPAHs contributing to the TEQ BaP. The standard deviation for this ratio is 0.063. It is important to note that the ratio of TEQ to total PAHs varies depending on the specific soil composition and the sources of contamination.

The calculated ILCR values in most cases differ from the ILCR values reported in the cited references within an order of magnitude. The main cause may lie in the uncertainty of the exposure factor values and the approximation of the TEQ values. Besides, the probabilistic HRA using Monte Carlo simulation used in some cited works resulted in a range of calculated ILCR values, whose mean values differ from the calculated ILCR values in this article. In some cases, ILCR and concentration values at the upper confidence level (UCL) of 90% or 95% were reported instead of the means. However, when the compared ILCR values differ by several orders of magnitude (underlined ILCR values in Table 1), this is primarily attributed to different units for Cs.

Interestingly, in some articles, the Cs units for the equations are written in ng/g or μg/kg, and yet the results obtained are as if mg/kg was used. This means that only the description of the equations was incorrect. However, if one strictly follows the equations and the units reported, which some authors apparently did, then it can easily result in a difference of several orders of magnitude in ILCR values.

4 Conclusion

The reliance on assumptions of consistent exposure factor values and approximation of TEQ values are the main reasons for the differences in the reported and calculated ILCR values. Additionally, the study does not explicitly explore the potential factor and TEQ variations and uncertainties, which are integral components of the HRA equations. However, the mistake in the PAH concentration units in the HRA models may cause a difference of three orders of magnitude in the ILCR estimates for the same concentration level. It may result in inadequate decisions in managing the investigated soil and related media, including sediment, road dust, and household dust. To summarize, it is recommended that PAH concentrations be expressed in ILCR equations as mg/kg. This could help future research to avoid inconsistencies and errors in the units for the concentration of PAHs and, consequently, errors in the associated health risk estimate due to the presence of PAHs in soil, sediment, or dust. It is noteworthy that this article covers only a part of the published works in reputable international journals, mostly recently published articles and a few published quite ago that have been cited many times.

Statements

Author contributions

AO: Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of Serbia (No. 451-03-47/2023-01/200135).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Ailijiang N. Zhong N. Zhou X. Mamat A. Chang J. Cao S. et al (2022). Levels, sources, and risk assessment of PAHs residues in soil and plants in urban parks of Northwest China. Sci. Rep.12, 21448. 10.1038/s41598-022-25879-8

2

Ali N. Ismail I. M. I. Khoder M. Shamy M. Alghamdi M. Al Khalaf A. et al (2017). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the settled dust of automobile workshops, health and carcinogenic risk evaluation. Sci. Total Environ.601, 478–484. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.110

3

Ambade B. Sethi S. S. Chintalacheruvu M. R. (2023). Distribution, risk assessment, and source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) using positive matrix factorization (PMF) in urban soils of East India. Environ. Geochem. Health45, 491–505. 10.1007/s10653-022-01223-x

4

Apiratikul R. Pongpiachan S. Deelaman W. (2021). Spatial distribution, sources and quantitative human health risk assessments of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban and suburban soils of Chile. Environ. Geochem. Health43, 2851–2870. 10.1007/s10653-020-00798-7

5

Besis A. Botsaropoulou E. Balla D. Voutsa D. Samara C. (2021). Toxic organic pollutants in Greek house dust: implications for human exposure and health risk. Chemosphere284, 131318. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131318

6

Bigović M. Đurović D. Nikolić I. Ivanović L. Bajić B. (2022). Profile, sources, ecological and health risk assessment of PAHs in agricultural soil in a pljevlja municipality. Int. J. Environ. Res.16, 90. 10.1007/s41742-022-00472-z

7

Cai H. Yao S. Huang J. Zheng X. Sun J. Tao X. et al (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons pollution characteristics in agricultural soils of the pearl river delta region, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health19, 16233. 10.3390/ijerph192316233

8

CCME (2010). Canadian soil quality guidelines for the protection of environmental and human health: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Can. Environ. Qual. Guidel., 19. Available at: https://ccme.ca/en/res/polycyclic-aromatic-hydrocarbons-2010-canadian-soil-quality-guidelines-for-the-protection-of-environmental-and-human-health-en.pdf.

9

Chen M. Huang P. Chen L. (2013). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils from Urumqi, China: distribution, source contributions, and potential health risks. Environ. Monit. Assess.185, 5639–5651. 10.1007/s10661-012-2973-6

10

Cui X. Ailijiang N. Mamitimin Y. Zhong N. Cheng W. Li N. et al (2023). Pollution levels, sources and risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in farmland soil and crops near Urumqi Industrial Park, Xinjiang, China. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess.37, 361–374. 10.1007/s00477-022-02299-8

11

Dreij K. Lundin L. Le Bihanic F. Lundstedt S. (2020). Polycyclic aromatic compounds in urban soils of Stockholm City: occurrence, sources and human health risk assessment. Environ. Res.182, 108989. 10.1016/j.envres.2019.108989

12

Fu X. W. Li T. Y. Ji L. Wang L. L. Zheng L. W. Wang J. N. et al (2018). Occurrence, sources and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils around oil wells in the border regions between oil fields and suburbs. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.157, 276–284. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.03.054

13

Gbeddy G. Egodawatta P. Goonetilleke A. Ayoko G. Chen L. (2020). Application of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) model in comprehensive human health risk assessment of PAHs, and alkyl-nitro-carbonyl-and hydroxyl-PAHs laden in urban road dust. J. Hazard. Mater.383, 121154. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121154

14

Gereslassie T. Workineh A. Liu X. Yan X. Wang J. (2018). Occurrence and ecological and human health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils from Wuhan, central China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health15, 2751. 10.3390/ijerph15122751

15

Ghanavati N. Nazarpour A. Watts M. J. (2019). Status, source, ecological and health risk assessment of toxic metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in street dust of Abadan, Iran. Catena177, 246–259. 10.1016/j.catena.2019.02.022

16

Gope M. Masto R. E. Basu A. Bhattacharyya D. Saha R. Hoque R. R. et al (2020). Elucidating the distribution and sources of street dust bound PAHs in Durgapur, India: a probabilistic health risk assessment study by Monte-Carlo simulation. Environ. Pollut.267, 115669. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115669

17

Gope M. Masto R. E. George J. Balachandran S. (2018). Exposure and cancer risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the street dust of Asansol city, India. Sustain. Cities Soc.38, 616–626. 10.1016/j.scs.2018.01.006

18

Grellier J. Rushton L. Briggs D. J. Nieuwenhuijsen M. J. (2015). Assessing the human health impacts of exposure to disinfection by-products–A critical review of concepts and methods. Environ. Int.78, 61–81. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.02.003

19

Grmasha R. A. Abdulameer M. H. Stenger-Kovács C. Al-sareji O. J. Al-Gazali Z. Al-Juboori R. A. et al (2023). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the surface water and sediment along Euphrates River system: occurrence, sources, ecological and health risk assessment. Mar. Pollut. Bull.187, 114568. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2022.114568

20

He M. Shangguan Y. Zhou Z. Guo S. Yu H. Chen K. et al (2023). Status assessment and probabilistic health risk modeling of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface soil across China. Front. Environ. Sci.11, 1–9. 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1114027

21

Hu T. Zhang J. Ye C. Zhang L. Xing X. Zhang Y. et al (2017). Status, source and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soil from the water-level-fluctuation zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. J. Geochem. Explor172, 20–28. 10.1016/j.gexplo.2016.09.012

22

Hussain K. Hoque R. R. Balachandran S. Medhi S. Idris M. G. Rahman M. , (2018). “Monitoring and risk analysis of PAHs in the environment,” in Handbook of environmental materials management (Cham: Springer), 1–35. 10.1007/978-3-319-58538-3_29-2

23

Jia T. Guo W. Xing Y. Lei R. Wu X. Sun S. et al (2021). Spatial distributions and sources of PAHs in soil in chemical industry parks in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Environ. Pollut.283, 117121. 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117121

24

Jiang Y. Hu X. Yves U. J. Zhan H. Wu Y. (2014). Status, source and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in street dust of an industrial city, NW China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.106, 11–18. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.04.031

25

Ke C. L. Gu Y. G. Liu Q. (2017). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in exposed-lawn soils from 28 urban parks in the megacity guangzhou: occurrence, sources, and human health implications. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol.72, 496–504. 10.1007/s00244-017-0397-6

26

Liang L. Zhu Y. Xu X. Hao W. Han J. Chen Z. et al (2023). Integrated insights into source apportionment and source-specific health risks of potential pollutants in urban park soils on the karst plateau, SW China. Expo. Heal15, 933–950. 10.1007/s12403-023-00534-3

27

Mallah M. A. Changxing L. Mallah M. A. Noreen S. Liu Y. Saeed M. et al (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and its effects on human health: an overeview. Chemosphere296, 133948. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133948

28

Miao X. Hao Y. Cai J. Xie Y. Zhang J. (2023). The distribution, sources and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediments of Liujiang River Basin: a field study in typical karstic river. Mar. Pollut. Bull.188, 114666. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2023.114666

29

Mihankhah T. Saeedi M. Karbassi A. (2020). Contamination and cancer risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban dust from different land-uses in the most populated city of Iran. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.187, 109838. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109838

30

Mohamadian Geravand P. Goudarzi G. Ahmadi M. (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban street dust in Masjed Soleyman, Khuzestan, Iran: sources and health risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.11, 1–11. 10.1080/03067319.2022.2103689

31

Najmeddin A. Moore F. Keshavarzi B. Sadegh Z. (2018). Pollution, source apportionment and health risk of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban street dust of Mashhad, the second largest city of Iran. J. Geochem. Explor190, 154–169. 10.1016/j.gexplo.2018.03.004

32

Odali E. W. Iwegbue C. M. A. Egobueze F. E. Nwajei G. E. Martincigh B. S. (2023). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in dust from rural communities around gas flaring points in the Niger Delta of Nigeria: an exploration of spatial patterns, sources and possible risk. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts26, 177–191. 10.1039/d3em00048f

33

Parra Y. J. Oloyede O. O. Pereira G. M. de Almeida Lima P. H. A. da Silva Caumo S. E. Morenikeji O. A. et al (2020). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils and sediments in Southwest Nigeria. Environ. Pollut.259, 113732. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113732

34

Patel A. B. Shaikh S. Jain K. R. Desai C. Madamwar D. (2020). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: sources, toxicity, and remediation approaches. Front. Microbiol.11, 562813. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.562813

35

Priya Ghosh S. Maiti S. K. (2020). Evaluation of PAHs concentration and cancer risk assessment on human health in a roadside soil: a case study. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess.26, 1042–1061. 10.1080/10807039.2018.1551052

36

Qi P. Qu C. Albanese S. Lima A. Cicchella D. Hope D. et al (2020). Investigation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils from Caserta provincial territory, southern Italy: spatial distribution, source apportionment, and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater.383, 121158. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121158

37

Qu Y. Gong Y. Ma J. Wei H. Liu Q. Liu L. et al (2020). Potential sources, influencing factors, and health risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the surface soil of urban parks in Beijing, China. Environ. Pollut.260, 114016. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114016

38

Roy D. Jung W. Kim J. Lee M. Park J. (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil and human health risk levels for various land-use areas in ulsan, South Korea. Front. Environ. Sci.9, 1–11. 10.3389/fenvs.2021.744387

39

Sankar T. K. Kumar A. Mahto D. K. Das K. C. Narayan P. Fukate M. et al (2023). The health risk and source assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the soil of industrial cities in India. Toxics11, 515. 10.3390/toxics11060515

40

Shi R. Li X. Yang Y. Fan Y. Zhao Z. (2021). Contamination and human health risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface soils from Tianjin coastal new region, China. Environ. Pollut.268, 115938. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115938

41

Shukla S. Khan R. Bhattacharya P. Devanesan S. AlSalhi M. S. (2022). Concentration, source apportionment and potential carcinogenic risks of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in roadside soils. Chemosphere292, 133413. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133413

42

Siemering G. S. Thiboldeaux R. (2021). Background concentration, risk assessment and regulatory threshold development: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin surface soils. Environ. Pollut.268, 115772. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115772

43

Sojinu O. S. S. Wang J. Z. Sonibare O. O. Zeng E. Y. (2010). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments and soils from oil exploration areas of the Niger Delta, Nigeria. J. Hazard. Mater.174, 641–647. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.09.099

44

Soltani N. Keshavarzi B. Moore F. Tavakol T. Lahijanzadeh A. R. Jaafarzadeh N. et al (2015). Ecological and human health hazards of heavy metals and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in road dust of Isfahan metropolis, Iran. Sci. Total Environ.505, 712–723. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.097

45

Soursou V. Campo J. Picó Y. (2023). Revisiting the analytical determination of PAHs in environmental samples: an update on recent advances. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem.37, e00195. 10.1016/j.teac.2023.e00195

46

Sun H. Jia X. Wu Z. Yu P. Zhang L. Wang S. et al (2024). Contamination and source-specific health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil from a mega iron and steel site in China. Environ. Pollut.340, 122851. 10.1016/j.envpol.2023.122851

47

Tanić M. N. Dinić D. Kartalović B. Mihaljev Ž. Stupar S. Ćujić M. et al (2023). Occurrence, source apportionment, and health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil of urban parks in a mid-sized city. Water. Air. Soil Pollut.234, 484. 10.1007/s11270-023-06504-4

48

Tarafdar A. Sinha A. (2019). Health risk assessment and source study of PAHs from roadside soil dust of a heavy mining area in India. Arch. Environ. Occup. Heal.74, 252–262. 10.1080/19338244.2018.1444575

49

Usepa (1991). USEPA risk assessment guidance for superfund: volume 1 human health evaluation manual (Part B, development of risk-based preliminary remediation goals), publication 9285.7-01B, office of emergency and remedial response. Washington DC, USA: USEPA.

50

Wang H. Liu D. Lv Y. Wang W. Wu Q. Huang L. et al (2024). Ecological and health risk assessments of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soils around a petroleum refining plant in China: a quantitative method based on the improved hybrid model. J. Hazard. Mater.461, 132476. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132476

51

Wang L. Zhang S. Wang L. Zhang W. Shi X. Lu X. et al (2018). Concentration and risk evaluation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban soil in the typical semi-arid city of Xi’an in Northwest China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health15, 607. 10.3390/ijerph15040607

52

Wang W. Huang M. Kang Y. Wang H. Leung A. O. W. Cheung K. C. et al (2011). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in urban surface dust of Guangzhou, China: status, sources and human health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ.409, 4519–4527. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.07.030

53

Wu Y. Zhao Y. Qi Y. Li J. Hou Y. Hao H. et al (2023). Characteristics, source and risk assessment of soil polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons around oil wells in the yellow river delta, China. WaterSwitzerl.15, 3324. 10.3390/w15183324

54

Wu Z. He C. Lyu H. Ma X. Dou X. Man Q. et al (2022). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polybrominated diphenyl ethers in urban road dust from Tianjin, China: pollution characteristics, sources and health risk assessment. Sustain. Cities Soc.81, 103847. 10.1016/j.scs.2022.103847

55

Zhang J. Yang J. Yu F. Liu X. Yu Y. (2020). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban Greenland soils of Nanjing, China: concentration, distribution, sources and potential risks. Environ. Geochem. Health42, 4327–4340. 10.1007/s10653-019-00490-5

56

Zhang S. Han Y. Peng J. Chen Y. Zhan L. Li J. (2023). Human health risk assessment for contaminated sites: a retrospective review. Environ. Int.171, 107700. 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107700

57

Zhang X. Wang X. Zhao X. Tang Z. Zhao T. Teng M. et al (2022). Using deterministic and probabilistic approaches to assess the human health risk assessment of 7 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Clean. Prod.331, 129811. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129811

58

Zhang Y. Chen H. Liu C. Chen R. Wang Y. Teng Y. (2021). Developing an integrated framework for source apportionment and source-specific health risk assessment of PAHs in soils: application to a typical cold region in China. J. Hazard. Mater.415, 125730. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125730

59

Zhang Y. Peng C. Guo Z. Xiao X. Xiao R. (2019). Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in urban soils of China: distribution, influencing factors, health risk and regression prediction. Environ. Pollut.254, 112930. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.07.098

60

Zhou L. Xue P. Zhang Y. Wei F. Zhou J. Wang S. et al (2022). Occupational health risk assessment methods in China: a scoping review. Front. Public Health10, 1035996. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1035996

Summary

Keywords

PAHs, cancer risk, exposure factors, ILCR, dimensional analysis, Monte Carlo

Citation

Onjia A (2024) Concentration unit mistakes in health risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil, sediment, and indoor/road dust. Front. Environ. Sci. 12:1370397. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1370397

Received

14 January 2024

Accepted

06 March 2024

Published

28 March 2024

Volume

12 - 2024

Edited by

Yalçın Tepe, Giresun University, Türkiye

Reviewed by

Sema Yurdakul, Süleyman Demirel University, Türkiye

Sait C. Sofuoglu, Izmir Institute of Technology, Türkiye

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Onjia.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Antonije Onjia, onjia@tmf.bg.ac.rs

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.