- 1Department of Biotechnology and Food Technology, Faculty of Science, University of Johannesburg, Doornfontein Campus, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 2Department of Environmental, Water and Earth Sciences, Faculty of Science, Tshwane University of Technology, Pretoria, South Africa

Introduction: Access to safe drinking water remains a critical challenge in rural developing regions, including South Africa, where naturally occurring fluoride and anthropogenic heavy metals (Pb2+, Cd2+, As, Cr6+) pose significant public health risks. Low-cost adsorbents derived from agricultural and natural materials have emerged as a promising solution for decentralized water treatment in resource-limited areas.

Methods: This systematic review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines and registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251084775). A total of 29 studies published between 2008 and 2025 were included. Eligible studies investigated the use of low-cost adsorbents—such as biochar, activated carbon, bone char, clay minerals, and agricultural residues—for the removal of fluoride and heavy metals from water sources. Key variables extracted included removal efficiency, adsorption capacity, operational conditions, and regeneration potential.

Results: Across the 29 studies, most adsorbents achieved removal efficiencies exceeding 90% for Pb2+, Cd2+, and Cr6+, with adsorption capacities ranging from 10 to >200 mg/g. Biochar and activated carbon demonstrated the highest performance, including superior regeneration potential, while agricultural by-products and clays contributed significant affordability and accessibility advantages. Approximately 40% of the included studies validated adsorbent performance using pilot- or field-scale testing, with slightly reduced but still effective removal compared to laboratory findings.

Discussion/Conclusion: Findings confirm that low-cost adsorbents offer practical, sustainable, and scalable treatment options for rural water contamination in South Africa. However, gaps remain in long-term regeneration, field durability, and treatment of emerging contaminants such as pharmaceuticals and microplastics. The review highlights the importance of context-specific, low-cost technologies for advancing water security and supporting public health. Overall, the evidence promotes the adoption of locally sourced adsorbents as viable technologies for improving rural water supply management in South Africa.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD420251084775, CRD420251084775

Highlights

• Safe water is essential for health, yet contaminants threaten rural communities.

• Low-cost adsorbents remove over 90% of Pb2+, Cd2+ and Cr6+, from water.

• Biochar and activated carbon demonstrate superior adsorption and regeneration potential.

• About 40% of included studies validated adsorbents in laboratory or real-world use.

1 Introduction

Access to safe drinking water is a basic human right and a prerequisite for public health, as it reduces the burden of waterborne diseases such as diarrhoeal, especially among young children (Needs, 2024). However, many rural communities in South Africa and Africa continue to face major challenges in safeguarding drinking water due to fluoride, heavy metals and other contaminants (Edokpayi et al., 2018; Bazaanah and Mothapo, 2023). Access to potable water is recognized as a fundamental human right; however, numerous rural communities in South Africa continue to experience persistent water quality challenges arising from both geogenic and anthropogenic sources. Elevated fluoride concentrations in groundwater, particularly within Limpopo, Northwest, and sections of the Eastern Cape provinces, have been linked to widespread occurrences of dental and skeletal fluorosis (Edokpayi et al., 2018; Onipe, 2018; Rammal et al., 2025). Concurrently, mining activities, industrial discharges, and agricultural runoff contribute to elevated levels of toxic metals such as lead, cadmium, arsenic, and chromium, posing severe health risks including neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and multi-organ impairment that ultimately hinder national development priorities (Edokpayi et al., 2018; Onipe, 2018).

Although conventional water treatment technologies, including reverse osmosis, ion exchange, and advanced oxidation processes, exhibit high removal efficiencies, their substantial capital costs, intensive energy requirements, and operational complexity constrain their feasibility in rural South African settings (Gregory and Sovacool, 2019; Atangana, 2020). Consequently, many rural households continue to depend on untreated or partially treated water sources, increasing the likelihood of chronic exposure to hazardous contaminants. In response, low-cost, locally derived adsorbents such as bone char, biochar, activated carbon, clay minerals, and agricultural by-products (e.g., banana peels, moringa seeds, macadamia shells, and maize tassels) have gained prominence as sustainable and context-appropriate alternatives for decentralized water purification systems (Fan et al., 2020; Afolabi and Musonge, 2023).

Conventional water treatment strategies such as reverse osmosis, ion exchange, and advanced oxidation processes, are highly efficient but often unaffordable or impractical for rural South African communities due to high capital costs, energy demands, technical complexity, and maintenance requirements (Gregory and Sovacool, 2019; Atangana, 2020). Consequently, many rural households continue to rely on untreated or minimally treated water, leading to persistent health burdens and increasing the risk of chronic exposure to toxic pollutants (Afolabi and Musonge, 2023). To address these limitations, low-cost, locally available adsorbers have emerged as sustainable alternatives for decentralized water purification. Materials such as bone char, biochar, activated carbon, clay minerals, and agricultural by-products (e.g., banana peels, moringa seeds, macadamia shells, maize tassels) have been widely studied for their ability to remove fluoride and heavy metals from contaminated water (Fan et al., 2020; Afolabi and Musonge, 2023).

These adsorbents offer notable advantages, including low cost, local availability, environmental sustainability, and potential for regeneration, making them particularly suitable for community-level applications. Moreover, many of these materials are derived from agricultural residues and natural resources abundant in South Africa, thereby providing the dual opportunities of waste valorization and water purification (Godfrey et al., 2022; Matsedisho et al., 2025). Conventional adsorbents, such as activated carbon and synthetic resins, are widely used due to their high efficiency and well-characterized performance. However, they are often costly, energy-intensive to produce, and may not be readily accessible in low-resource settings. In contrast, low-cost adsorbents derived from agricultural waste, natural minerals, or industrial by-products offer a more affordable and locally available alternative. They are environmentally friendly and promote resource recovery, but their adsorption capacity, regeneration potential, and long-term stability may vary depending on the source material and water chemistry. Overall, while conventional adsorbents are highly effective, low-cost adsorbents present a more sustainable and context-appropriate solution for vulnerable populations, provided that site-specific optimization and field validation are conducted.

Despite an expanding body of international research on biosorbents and low-cost adsorbents, systematic evaluations that specifically address the South African context remain limited. Most previous reviews have focused broadly on heavy metal remediation technologies or on single classes of adsorbents, often without integrating fluoride removal and overlooking the socioeconomic realities of rural populations (Matsedisho et al., 2025).

Furthermore, few studies have assessed performance under real-world conditions, where removal efficiencies often decline compared with those reported in controlled laboratory experiments (Hlungwane et al., 2018; Atangana, 2020; Adeeyo et al., 2025).

This knowledge gap has restricted the translation of promising technologies into scalable, sustainable solutions for vulnerable populations. Hence this review systematically evaluates the performance of low-cost adsorbents for fluoride and heavy metal Lead (Pb) Cadmium (Cd), Arsenic (As), Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni), Zinc (Zn), and Mercury (Hg) removal in South Africa between 2000 and 2025. The analysis demonstrates removal efficiency, adsorption capacity, regeneration potential, and field applicability, with the aim of identifying technologies that can bridge the gap between laboratory innovation and rural water security. By providing a comparative synthesis of locally available adsorbents, this work aims to inform evidence-based policy development, guide future research directions, and support the implementation of cost-effective strategies for improving water quality. Through the promotion of evidence-based, cost-effective, and sustainable water treatment strategies, this systematic review aligns with and advances the objectives of Sustainable Development Goal 6 (accessible, affordable clean water and Sanitation) while reinforcing broader commitments to environmental sustainability in South Africa.

2 Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. A predefined protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (registration ID: CRD420251084775) to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor. The research question was structured using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) framework to evaluate the performance of low-cost adsorbents for fluoride and heavy metal removal in rural South African water supplies.

2.1 Eligibility criteria

Peer-reviewed studies published between 1 January 2000 and 30 June 2025, written in English, and either conducted in South Africa or directly applicable to rural Saharan African water contexts were considered. Eligible studies investigated the removal of fluoride and/or toxic heavy metals (Pb, Cd, As, Cr, Ni, Zn, Hg) from drinking water, groundwater, or wastewater using low-cost, natural, or agricultural by-product adsorbents. Both laboratory- and field-based studies (batch and column adsorption) were included.

Exclusion criteria comprised:

• Studies published outside the defined timeframe.

• Articles in languages other than English.

• Research not related to South Africa or rural sub-Saharan contexts.

• Studies addressing only non-metal contaminants (e.g., pesticides, PFAS, microplastics).

• Studies utilizing synthetic, commercial, or high-cost adsorbents.

2.2 Search strategy

A comprehensive search was carried out in Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and PubMed. Search strings combined controlled keywords and Boolean operators, for example, (fluoride or heavy metals or lead or arsenic or cadmium and low-cost adsorbents or biosorbents or biochar or activated carbon or bone char or moringa or fly ash or agricultural waste) and (water treatment or adsorption or removal) and South Africa or rural water supply). Reference lists of relevant articles were also screened manually to capture additional studies.

2.2.1 Search words

Fluoride or heavy metals OR lead OR arsenic OR cadmium AND low-cost adsorbents OR biosorbents OR biochar OR activated carbon OR bone char OR moringa OR fly ash OR agricultural waste AND water treatment OR adsorption OR removal AND South Africa OR rural water supply.

2.3 Screening procedure

All identified studies were imported into Endnote for reference management and subsequently exported to Covidence for screening by two different authors (Richard Fagbohun and Viola Okechwuku). Following de-duplication, a two-stage screening process was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. In the first stage. First, titles and abstracts were screened against the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine relevance. Second stage, the full text of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and assessed for final inclusion. Screening was conducted independently by at least two reviewers to reduce bias. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and, when consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer, Oluwasola A Adelusi was consulted. Reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage were documented.

To reduce publication bias, this review implemented a comprehensive and systematic search across major scientific databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and PubMed. Broad, inclusive search terms incorporating controlled vocabulary and Boolean operators were applied to capture all potentially relevant studies. Only published articles were included, while reference lists of eligible papers were manually examined to identify additional studies that may not have been retrieved through database searches. This rigorous approach ensured balanced representation of both positive and negative outcomes, thereby minimizing the likelihood of selective reporting. The systematic review was limited to studies published in English, as it constitutes the predominant language of scientific communication in South Africa and the broader sub-Saharan African region. Although non-English publications were excluded, this criterion was justified by the scarcity of regional research in other languages and the linguistic competencies of the reviewers. Furthermore, no restrictions were imposed on the country of publication, enabling the inclusion of all studies relevant to the South African or rural sub-Saharan context, irrespective of their geographic origin.

2.4 Study risk of bias or quality assessment

To ensure the reliability and validity, all included studies underwent formal appraisal using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool appropriate for environmental and engineering research. A modified JBI Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies was used to assess methodological quality. Criteria included clarity of research objectives, appropriateness of experimental design, control of confounding variables, accuracy of outcome measurements, and suitability of statistical analysis. Each study was independently rated by two reviewers as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias; disagreements were resolved through discussion. Quality-assessment outcomes informed the weighting of evidence during synthesis and were presented in summary tables to enhance transparency and support evidence-based recommendations.

2.5 Data synthesis strategy

Data were synthesized using quantitative evidence tables and narrative analysis. Key variables extracted from each included study, adsorbent type, target contaminant (fluoride or specific heavy metals), removal efficiency (%, or adsorption capacity), operational conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, contact time) and regeneration capability were organized into comparative matrices to enable side-by-side assessment of performance across different studies. Mean removal efficiencies or adsorption capacities was summarized using descriptive statistics. Given the likely heterogeneity in study designs, materials tested, water matrices, and measurement protocols, meta-analysis was not conducted. Instead, a structured narrative synthesis was used to identify recurring patterns, trends, trade-offs, and context-specific findings. The synthesis also evaluated practical feasibility in South African setting including affordability, local availability, ease of use, and sustainability. Where relevant, Subgroup comparisons (e.g., laboratory vs. field studies or fluoride vs. metal removal) were highlighted in the tables. Results are presented in text, tables, and figures to support evidence-based recommendations for rural South Africa.

3 Result

3.1 Study selection and characteristics

The identification process for this systematic review was conducted systematically and rigorously, starting with the screening of 395 studies (see Figure 1). Out of these, 132 were chosen for retrieval, and 130 underwent eligibility assessment. During this phase, 40 references were eliminated, and duplicates were identified one manually and 39 through the Covidence tool. Notably, no studies were classified as ineligible by automation tools, indicating the robustness of the initial evaluation. Ultimately, 263 studies were excluded for several reasons: two were not retrieved, 20 had incorrect outcomes, one had an unsuitable indication, and 80 fell outside the geographical focus of South Africa. This meticulous exclusion process was essential to ensure the relevance and specificity of the review. In total, 29 studies were included, all of which are ongoing, reflecting a focused effort to investigate low-cost adsorbents for the removal of fluoride and heavy metals from rural water supplies. The screening results demonstrate a comprehensive literature evaluation, drawing from a variety of sources across databases such as Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Embase.

Figure 1 PRISMA 2020 flow diagram detailing the systematic identification, screening, eligibility evaluation, and final inclusion of studies. The diagram outlines the comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases, removal of duplicates through both manual and automated methods, title, abstract screening, and full-text assessment based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Following this rigorous multi-stage selection process, a total of 29 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final review.

Research was conducted across multiple provinces, including Limpopo, Gauteng, Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Free State, with most focusing on either synthetic aqueous solutions or real wastewater samples. As shown in Table 1, the characteristics of included studies are summarized. Adsorbents were derived from diverse natural and agricultural sources, such as tobacco dust, rooibos shoot powder, fly ash, macadamia nutshells, banana peels, orange peels, moringa leaves, fennel seeds, and chitosan (from crab shells). Analytical techniques and characterization techniques included atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface analysis, and X-ray diffraction (XRD), indicating robust approaches to quantification and materials characterization.

Table 1. Study Characteristics, including study location, water source, adsorbent type and source, study design and analytical technique.

3.2 Temporal distribution of publication

The temporal distribution of publications on low-cost adsorbents for water treatment in South Africa, as presented in the Figure 2, shows a progressive increase in research attention toward sustainable and economically feasible water purification strategies. From 2008 to 2015, research output has increased steadily but remained low, between 2016 and 2018, the number of studies rose to 2–3 annually, peaking at six publications in 2022. Although there was a slight decline after 2022, annual outputs remained consistent, demonstrating sustained interest in low-cost adsorbents for water treatment.

3.3 Distribution of reported low-cost adsorbents in South Africa

The bar chart (Figure 3) depicts the distribution of reported low-cost adsorbents available in South Africa across five categories, each contributing distinct proportions to the total. The largest share corresponds to 26.7%, followed by 23.3% and 20%, while the smaller categories account for 16.7% and 13.3%, respectively. The distribution pattern appears relatively balanced, with no single category demonstrating clear dominance. This indicates that all reported adsorbent categories contribute meaningfully, thereby offering a comprehensive overview of low-cost adsorbent availability in the South African context.

Figure 3. Percentage distribution of research focus areas on low-cost adsorbents in South Africa (2000–2025).

3.4 Distribution of reported water sources in South Africa

This distribution, illustrated in the pie chart, provides a clear visual representation of the relative research emphasis across different water sources. The included studies have investigated multiple water sources, with wastewater and industrial effluents receiving the greatest attention of 34%, followed by groundwater (31%), surface water (24%), and drinking water (21%) (Figure 4). The results demonstrate the significance of treated water research in South Africa, revealing ongoing efforts to address water quality and pollution challenges.

3.5 Experimental conditions

Operational conditions varied widely across studies the reviewed studies, as summarized in Table 2. The pH values ranged from 2 to 12, comprising conditions typical of acidic mine drainage through alkaline wastewater. Most adsorption experiments were performed at room temperature (≈25 °C), although adsorbent preparation often required high activation temperatures between 200 °C and 800 °C. Contact times ranged from 5 min to 72 h, with optimum contaminant removal generally occurring within 30–120 min, confirming the practicality of these adsorbents for rapid treatment. Removal efficiencies exceeded 90%, with several studies reporting near-complete removal (100%) of Pb (II), Cd (II), and Cr (VI) under optimal conditions. Adsorption capacities varied considerably, from approximately 10 mg/g to more than 200 mg/g.

Biochar and activated carbon consistently demonstrated the highest adsorption capacities (>100 mg/g), attributable to their high surface area and micro/microporosity. In contrast, clays and agricultural wastes exhibited more modest performance (10–60 mg/g), though their availability and low cost make them highly relevant for rural application. The studies demonstrate the overall performance of various low-cost adsorbents under differing experimental conditions. For heavy metals such as lead (Pb2+) and cadmium (Cd2+), reported removal efficiencies ranged from approximately 70%–100%, while adsorption capacities varied considerably, from about 24.5 mg/g to over 200 mg/g, depending on the specific metal ion and adsorbent material employed.

Similarly, chromium (Cr(VI)) exhibited high removal efficiencies of up to 99%, with adsorption capacities reaching 114 mg/g in some studies. The optimal contact times necessary to achieve maximum removal typically ranged between 30 min and several hours, reflecting both the kinetics of adsorption and the physicochemical characteristics of the materials used. Notably, many investigations confirmed effective contaminant removal under both laboratory and field conditions, indicating the practical applicability of these materials. Furthermore, results from regeneration experiments demonstrated that several adsorbents retained substantial adsorption capacity after multiple reuse cycles, reinforcing their potential for sustainable water treatment applications.

3.6 Trend in publications on low-cost adsorbents for water treatment in South Africa

The line graph (Figure 5) illustrates a steady increase trend in the number of included articles across the selected years. The values rise progressively from the initial to the final stage. Demonstrating growing research interest and steady progress in studies on low-cost adsorbents for water treatment South Africa. This graphical summary provides a clear temporal perspective and provides insight into potential future research trajectories in this field.

3.7 Water sources and contaminant profiles in South African studies

As shown in Figure 6, more than 75% of these investigations concentrated on toxic heavy metals, particularly lead and cadmium, due to their well-documented health risks. Other contaminants, including dyes (10%), microbial pathogens (5%), arsenic (3%), and fluoride (3%), were less frequently addressed but remain of concern. A smaller proportion of studies examined emerging pollutants such as antibiotics (e.g., sulfamethoxazole), reflecting an increasing recognition of the broader and evolving challenges to water quality.

3.8 Experimental conditions

Adsorption was investigated across a diverse operating condition. The pH levels reported ranged from 2 to 12, covering both acidic and alkaline wastewater environments. Most experiments were conducted at room temperature (25 °C), whereas adsorbent preparation commonly involved high activation temperatures between 200 °C and 800 °C. Contact times varied considerably from a minimum of 5 min to a maximum of 72 h, with optimal removal typically achieved within 30–120 min.

3.9 Regeneration and field applications

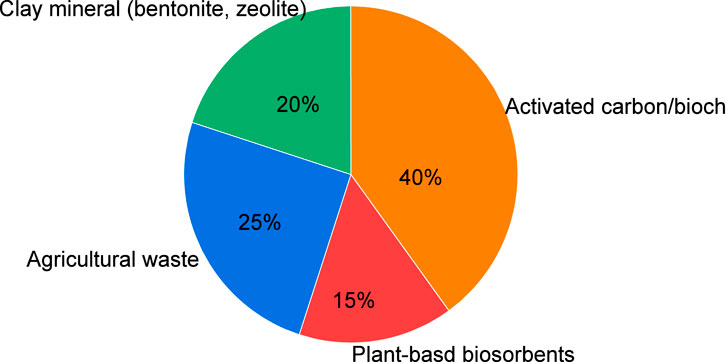

The pie chart (Figure 7) illustrates the percentage distribution of adsorbent types used in the included studies. Activated carbon and biochar represent the highest proportion (40%), followed by agricultural waste (25%), clay minerals such as bentonite and zeolite (20%), and plant-based biosorbents (15%). This distribution demonstrates the predominant reliance on activated carbon and biochar in water treatment research, signalling the growing scientific interest in low-cost adsorbents derived from agricultural and natural materials.

Figure 7. Percentage distribution of adsorbent types for water treatment applications in South Africa.

Herein, nine studies evaluating adsorbents regeneration, materials were effectively reused for three and ten-times cycles before measurable performance decline. Approximately 40% of these studies included field or pilot-scale validations, which yielded removal efficiencies modestly lower than laboratory values yet operationally meaningful. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the importance of both the category distribution shown in Figure 6 and emphasize the practical implications of adsorbent reuse in real-world water treatment applications.

4 Discussion

This systematic review highlights the growing research focus on low-cost adsorbents as viable technologies for removing fluoride and heavy metals from contaminated water in South Africa. The marked rise in publications after 2015, and further consolidation after 2020, reflects increasing global and regional recognition of sustainable, affordable, and context-specific remediation technologies particularly in developing regions where access to safe water remains a critical challenge (Ali et al., 2012; Edokpayi et al., 2017). The expanding research base also suggests a transition of biosorbents and other low-cost adsorbents from laboratory-scale evaluations toward field-scale and community-level applications (Nkhalambayausi-Chirwa et al., 2019; Nguyen et al., 2022). More than 75% of the reviewed studies focused on heavy metals such as lead (Pb2+), cadmium (Cd2+), and chromium (Cr6+), confirming their status as priority pollutants due to their persistence, bioaccumulation, and severe health effects including carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity (Fu and Wang, 2011).

Fluoride contamination in water has received increasing global attention (Yadav et al., 2021; Duggal and Sharma, 2022; Ahmad et al., 2022; Banerjee and Roychoudhury, 2022; Hefferon et al., 2024), including in developing regions such as Africa (Ouro-Sama et al., 2021; Sunkari et al., 2022; Okafor et al., 2023). In South Africa, recent studies (Onipe et al., 2021; Patience et al., 2021; Mutileni et al., 2023) have documented the occurrence of various hazardous contaminants in both surface and groundwater systems, highlighting an escalating threat to public health and reinforcing the urgency of effective water quality management. These reports emphasize the critical need for continuous monitoring, strengthened regulatory frameworks, and the adoption of improved treatment technologies, particularly low-cost adsorbents, to safeguard communities that depend on these water sources for domestic, agricultural, and industrial purposes (Ojedokun and Bello, 2016).

The majority of studies were conducted under a wide range of conditions, with pH values spanning from 2 to 12 and contact times ranging from a few minutes to several hours. Despite this variability, optimal removal was typically achieved within 30–120 min, supporting the practicality of these materials for decentralized treatment systems. Adsorption capacities varied between 10 and 200 mg/g, with carbonaceous adsorbents particularly biochar and activated carbon consistently demonstrating superior removal and regeneration performance owing to their high surface area, tunable functional groups, and micro-/mesoporosity (Demirbas, 2008; Mohan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). These findings collectively affirm the suitability of carbon-based materials for contaminant immobilization and sustainable water purification.

The regeneration potential of adsorbents is another critical factor influencing their long-term feasibility. In this review, nine studies reported regeneration cycles ranging from three to ten, with adsorption efficiencies largely retained up to five cycles. Acidic eluents such as dilute HCl were commonly used for desorption, although Pb2+ exhibited relatively lower desorption efficiency than other metals. While these results confirm the reusability of many low-cost adsorbents, further optimization is needed to minimize performance deterioration, ensure chemical stability, and prevent secondary pollution from eluents (Bhatnagar and Sillanpää, 2010; Chen et al., 2023).

Another key outcome of this review is that approximately 40% of included studies validated adsorbent performance using real wastewater or field-scale systems. Although removal efficiencies were generally lower than those observed in controlled laboratory conditions, these field evaluations provide crucial evidence of practical applicability an aspect previously underrepresented in earlier reviews (Crini and Lichtfouse, 2019). The observed discrepancies underscore the importance of extended pilot-scale studies that account for complex water matrices, fluctuating contaminant concentrations, and long-term operational sustainability in rural contexts (Vujić et al., 2025). Taken together, these findings support a dual implementation strategy: prioritizing high-performing carbonaceous adsorbents for scalable water treatment while advancing cost-effective agricultural and clay-based materials through surface modification and hybrid material design to improve their efficiency and field durability (Bhatnagar and Sillanpää, 2010; Chen et al., 2023).

5 Knowledge gaps and future research needs

Although significant progress has been made in the development and application of low-cost adsorbents for water purification, several knowledge gaps persist that constrain their practical implementation and long-term sustainability. Firstly, the field durability and stability of most materials remain inadequately explored. Only a limited number of studies have evaluated the structural integrity and adsorption efficiency of adsorbents over extended operational periods. Consequently, uncertainties remain regarding material degradation, biofouling, and performance decline under fluctuating field conditions such as pH variation, temperature shifts, and mixed contaminant loads. Comprehensive long-term field evaluations are therefore required to establish operational lifespans and maintenance protocols suited to rural water systems.

Secondly, optimization of regeneration processes has not been extensively addressed in the literature. Although several studies demonstrated adsorbent reuse for three to five cycles, desorption is frequently achieved using acidic eluents that may contribute to secondary pollution and performance deterioration. Standardized regeneration protocols and environmentally benign reactivation methods such as biological, thermal, or electrochemical approaches are yet to be systematically investigated. These refinements are necessary to enhance cost-effectiveness and ensure the chemical stability of reusable materials under practical conditions.

Finally, there is a marked paucity of long-term cost benefit and life-cycle assessments evaluating the economic, environmental, and social implications of adopting low-cost adsorbents at community or municipal scales. Most existing studies focus on laboratory efficiencies without integrating economic feasibility, maintenance demand, or local governance structures. Future research should therefore incorporate techno-economic evaluations and sustainability assessments to guide policy formulation and large-scale implementation. Addressing these gaps through partnerships with local municipalities and community water boards could support pilot adoption, interdisciplinary approaches will be essential for the advancement of durable, regenerative, and economically viable adsorption technologies for water treatment in rural South Africa.

Despite substantial progress in the development of low-cost adsorbents for water purification, significant knowledge gaps remain concerning their long-term performance, regeneration efficiency, and economic sustainability. Current research is largely confined to short-duration laboratory assessments, providing limited insight into adsorbent stability and removal efficiency under dynamic field conditions influenced by fluctuating pH, temperature, and complex contaminant matrices. Furthermore, existing regeneration practices are often chemically intensive and insufficiently optimized, highlighting the necessity for standardized, eco-friendly reactivation protocols that mitigate secondary pollution risks. In addition, comprehensive evaluations of life-cycle costs, scalability, and socio-economic viability within rural applications are still scarce. Bridging these gaps through coordinated, interdisciplinary investigations will be essential to generate robust evidence that informs national policy, strengthens community-based water treatment initiatives, and advances sustainable water management within South African and broader BRICS research frameworks.

6 Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates that substantial progress has been made in the development and application of low-cost adsorbents for water treatment in South Africa between 2008 and 2025. The evidence identifies carbon-based adsorbents, particularly biochar and activated carbon, as the most promising materials, achieving high removal efficiencies (>90%), adsorption capacities often exceeding 100 mg/g, and regeneration potential of up to 10 cycles. Although agricultural by-products and clay-based materials are generally less efficient, they remain cost-effective and locally accessible, making them particularly suitable for rural communities. The findings further indicate that while laboratory studies dominate the literature, approximately 40% of the included studies validated adsorbent performance under pilot- or field-scale conditions. These studies confirm the practical applicability of low-cost adsorbents, although removal efficiencies are typically lower than those reported in controlled laboratory environments. This demonstrates the importance of bridging the gap between laboratory research and real-world application through long-term pilot studies, standardized regeneration protocols, and durability assessments under field conditions.

Future studies should extend beyond traditional targets such as heavy metals and fluoride to address emerging contaminants, including pharmaceuticals, synthetic dyes, and microplastics, which pose an increasing threat to water security. Moreover, advancements in surface modification, hybrid composites, and nanostructured adsorbents offer promising avenues to enhance performance while preserving affordability and sustainability. In conclusion, low-cost adsorbents represent a viable, sustainable, and scalable solution for improving water quality in rural South Africa. These findings further highlight the potential for community-based adoption of biochar and activated carbon technologies through partnerships with local municipalities and rural water boards, supporting the translation of research innovations into practical, decentralized water treatment solutions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

TF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft. VO: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. OA: Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. JO: Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by the School of Postgraduate Studies, Tshwane University of Technology through the Innovation of Postdoctoral Fellowship, awarded to the corresponding author, Dr. Viola O Okechukwu (Grant No. 1012376).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Tshwane University of Technology (Pretoria, South Africa) for institutional support and access to facilities used in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adeeyo, A. O., Oyetade, J. A., Msagati, T. A., Colile, N., and Makungo, R. (2025). Performance of a wild sesame (sesamum spp) phytochemical extract for water disinfection. Water, Air, and Soil Pollut. 236 (2), 108. doi:10.1007/s11270-024-07666-5

Adeiga, O. I., and Pillay, K. (2024). Adsorptive removal of Cd (II) ions from water by a cheap lignocellulosic adsorbent and its reuse as a catalyst for the decontamination of sulfamethoxazole. ACS Omega 9 (37), 38348–38358. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c08761

Afolabi, F. O., and Musonge, P. (2023). Synthesis, characterization, and biosorption of Cu2+ and Pb2+ ions from an aqueous solution using biochar derived from orange peels. Molecules 28 (20), 7050. doi:10.3390/molecules28207050

Afolabi, F. O., Musonge, P., and Bakare, B. F. (2022). Evaluation of lead (II) removal from wastewater using banana peels: optimization study.

Agboola, O., Nwankwo, O. J., Akinyemi, F. A., Chukwuka, J. C., Ayeni, A. O., Popoola, P., et al. (2024). Adsorptive removal of Fe and Cd from the textile wastewater using ternary bio-adsorbent: adsorption, desorption, adsorption isotherms and kinetic studies. Discov. Sustain. 5 (1), 312. doi:10.1007/s43621-024-00523-9

Ahmad, A., Farrah, N., and Ali, S. (2022). Fluoride contamination in drinking water and associated health risk assessment in the Malwa Belt of Punjab, India. Environmental Advances 8, 100242.

Ali, I., Asim, M., and Khan, T. A. (2012). Low cost adsorbents for the removal of organic pollutants from wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 113, 170–183. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.08.028

Amaku, J. F., and Taziwa, R. (2023). Preparation and characterization of Allium cepa extract coated biochar and adsorption performance for hexavalent chromium. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 20786. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48299-8

Amaku, J. F., and Taziwa, R. (2024). Aqueous removal of Cr (VI) by citrus sinensis juice-coated multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Chem. Pap. 78 (9), 5415–5431. doi:10.1007/s11696-024-03481-8

Ataguba, C. O., and Brink, I. (2022). Application of isotherm models to combined filter systems for the prediction of iron and lead removal from automobile workshop stormwater runoff. Water Sa. 48 (4), 476–486. doi:10.17159/wsa/2022.v48.i4.3971

Atangana, E. (2020). Production, disposal, and efficient technique used in the separation of heavy metals from red meat abattoir wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27 (9), 9424–9434. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06850-z

Banerjee, A., and Roychoudhury, A. (2022). Assessing the rhizofiltration potential of three aquatic plants exposed to fluoride and multiple heavy metal polluted water. Vegetos 35, 1158–1164. doi:10.1007/s42535-022-00405-3

Bayuo, J., Rwiza, M. J., and Mtei, K. M. (2024). Modeling and optimization of trivalent arsenic removal from wastewater using activated carbon produced from maize plant biomass: a multivariate experimental design approach. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 14 (19), 24809–24832. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04494-1

Bazaanah, P., and Mothapo, R. A. (2023). Sustainability of drinking water and sanitation delivery systems in rural communities of the lepelle nkumpi local municipality, South Africa. Environ. Development Sustainability 13 (1), 1–33. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03190-4

Bhatnagar, A., and Sillanpää, M. (2010). Utilization of agro-industrial and municipal waste materials as potential adsorbents for water treatment—A review. Chem. Engineering J. 157 (2-3), 277–296. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2010.01.007

Bunhu, T., Tichagwa, L., and Chaukura, N. (2017). Competitive sorption of Cd2+ and Pb2+ from a binary aqueous solution by poly (methyl methacrylate)-grafted montmorillonite clay nanocomposite. Appl. Water Sci. 7 (5), 2287–2295. doi:10.1007/s13201-016-0404-5

Chen, Y., Li, X., and Zhao, M. (2023). Biochar applications in water treatment: A critical review. J. Env. Manag., 326, 116741. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.11674

Cibati, A., Foereid, B., Bissessur, A., and Hapca, S. (2017). Assessment of miscanthus× giganteus derived biochar as copper and zinc adsorbent: study of the effect of pyrolysis temperature, pH and hydrogen peroxide modification. J. Clean. Prod. 162, 1285–1296. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.06.114

Crini, G., and Lichtfouse, E. (2019). Advantages and disadvantages of techniques used for wastewater treatment. Environ. Chem. Lett. 17, 145–155.

Demirbas, A. (2008). Heavy metal adsorption onto agro-based waste materials: a review. J. Hazard. Mterials 157 (2-3), 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.01.024

Dimpe, K. M., Ngila, J. C., and Nomngongo, P. N. (2017). Application of waste tyre-based activated carbon for the removal of heavy metals in wastewater. Cogent Eng. 4 (1), 1330912. doi:10.1080/23311916.2017.1330912

Duggal, V., and Sharma, S. (2022). Fluoride contamination in drinking water and associated health risk assessment in the malwa belt of Punjab, India. Environ. Adv. 8, 100242. doi:10.1016/j.envadv.2022.100242

Edokpayi, J. N., Odiyo, J. O., Msagati, T. A., and Popoola, E. O. (2015). A novel approach for the removal of lead (II) ion from wastewater using mucilaginous leaves of diceriocaryum eriocarpum plant. Sustainability 7 (10), 14026–14041. doi:10.3390/su71014026

Edokpayi, J. N., Odiyo, J. O., and Durowoju, O. S. (2017). Impact of wastewater on surface water quality in developing countries: a case study of South Africa. Water Qual. 10 (66561), 10–5772. doi:10.5772/66561

Edokpayi, J. N., Rogawski, E. T., Kahler, D. M., Hill, C. L., Reynolds, C., Nyathi, E., et al. (2018). Challenges to sustainable safe drinking water: a case study of water quality and use across seasons in rural communities in Limpopo province, South Africa. Water 10 (2), 159. doi:10.3390/w10020159

Fan, Z., Li, X., Jiang, B., Wang, X., and Wang, Q. (2020). Mapping atmospheric corrosivity in shandong. Water, Air, and Soil Pollut. 231 (12), 569. doi:10.1007/s11270-020-04939-7

Fu, F., and Wang, Q. (2011). Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewaters: a review. J. Environ. Manag. 92 (3), 407–418. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.011

Gitari, W. M., Petrik, L., Key, D. L., and Okujeni, C. (2013). Inorganic contaminants attenuation in acid mine drainage by fly ash and its derivatives: column experiments. Int. J. Of Environ. And Pollut. 51 (1-2), 32–56. doi:10.1504/ijep.2013.053177

Godfrey, L., Sithole, B., Jacob John, M., Mturi, G., and Muniyasamy, S. (2022). “Transitioning to a circular economy in South Africa: the role of innovation in driving greater waste valorization,” in Circular economy and waste valorisation: theory and practice from an international perspective (Springer), 153–176.

Gregory, J., and Sovacool, B. K. (2019). Rethinking the governance of energy poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: reviewing three academic perspectives on electricity infrastructure investment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 111, 344–354. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.05.021

Harripersadth, C., and Musonge, P. (2022). The dynamic behaviour of a binary adsorbent in a fixed bed column for the removal of Pb2+ ions from contaminated water bodies. Sustainability 14 (13), 7662. doi:10.3390/su14137662

Hefferon, R., Goin, D. E., Sarnat, J. A., and Nigra, A. E. (2024). Regional and racial/ethnic inequalities in public drinking water fluoride concentrations across the US. J. Of Expo. Sci. and Environ. Epidemiol. 34, 68–76. doi:10.1038/s41370-023-00570-w

Hlungwane, L., Viljoen, E. L., and Pakade, V. E. (2018). Macadamia nutshells-derived activated carbon and attapulgite clay combination for synergistic removal of Cr (VI) and Cr (III). Adsorpt. Sci. and Technol. 36 (1-2), 713–731. doi:10.1177/0263617417719552

Hussien, M. T. M., El-Liethy, M. A., Abia, A. L. K., and Dakhil, M. A. (2020). Low-cost technology for the purification of wastewater contaminated with pathogenic bacteria and heavy metals. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 231. doi:10.1007/s11270-020-04766-w

Kanu, S. A., Moyo, M., Zvinowanda, C. M., and Okonkwo, J. O. (2016). Biosorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solution using rooibos shoot powder (RSP). Desalination Water Treat. 57 (12), 5614–5622. doi:10.1080/19443994.2015.1004116

Mabungela, N., Shooto, N. D., Mtunzi, F., and Naidoo, E. B. (2022a). The adsorption of copper, lead metal ions, and methylene blue dye from aqueous solution by pure and treated fennel seeds. Adsorpt. Sci. and Technol. 2022, 5787690. doi:10.1155/2022/5787690

Mabungela, N., Shooto, N. D., Mtunzi, F., and Naidoo, E. B. (2022b). Binary adsorption studies of Cr (VI) and Cu (II) ions from synthetic wastewater using carbon from feoniculum vulgare (fennel seeds). Cogent Eng. 9 (1), 2119530. doi:10.1080/23311916.2022.2119530

Maremeni, L. C., Modise, S. J., Mtunzi, F. M., Klink, M. J., and Pakade, V. E. (2018). Adsorptive removal of hexavalent chromium by diphenylcarbazide-grafted macadamia nutshell powder. Bioinorganic Chem. Appl. 2018 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1155/2018/6171906

Masekela, D., Yusuf, T. L., Hintsho-Mbita, N. C., and Mabuba, N. (2022). Low cost, recyclable and magnetic Moringa oleifera leaves for chromium (VI) removal from water. Front. Water 4, 722269. doi:10.3389/frwa.2022.722269

Masindi, V. (2017). Application of cryptocrystalline magnesite-bentonite clay hybrid for defluoridation of underground water resources: implication for point of use treatment. J. Water Reuse Desalination 7 (3), 338–352. doi:10.2166/wrd.2016.055

Masinga, T., Moyo, M., and Pakade, V. E. (2022). Removal of hexavalent chromium by polyethyleneimine impregnated activated carbon: intra-particle diffusion, kinetics and isotherms. J. Of Mater. Res. And Technol. 18, 1333–1344. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.03.062

Masuku, M., Nure, J. F., Atagana, H. I., Hlongwa, N., and Nkambule, T. T. (2025). The development of multifunctional biochar with NiFe2O4 for the adsorption of Cd (II) from water systems: the kinetics, thermodynamics, and regeneration. J. Environ. Manag. 373, 123705. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123705

Matsedisho, B., Otieno, B., Kabuba, J., Leswifi, T., and Ochieng, A. (2025). Removal of Ni (II) from aqueous solution using chemically modified cellulose nanofibers derived from orange peels. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22 (5), 2905–2916. doi:10.1007/s13762-024-05819-x

Mohan, C., Western, A. W., Wei, Y., and Saft, M. (2018). Predicting groundwater recharge for varying land cover and climate conditions–a global meta-study. Hydrology Earth Syst. Sci. 22 (5), 2689–2703. doi:10.5194/hess-22-2689-2018

Mutileni, N., Mudau, M., and Edokpayi, J. N. (2023). Water quality, geochemistry and human health risk of groundwater in the vyeboom region, Limpopo province, South Africa. Sci. Rep. 13, 19071. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-46386-4

Needs, H. (2024). Interventions to mitigate burdens of waterborne and water-related disease. Textb. Children's Environ. Health, 378–397. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197662526.003.0029

Nguyen, C., Costa, G., Girardi, L., Volpato, G., Bressan, A., Chen, Y., et al. (2022). PARSEC V2. 0: stellar tracks and isochrones of low-and intermediate-mass stars with rotation. Astronomy and Astrophysics 665, A126. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202244166

Nkhalambayausi-Chirwa, E. M., Molokwane, P. E., Lutsinge, T. B., Igboamalu, T. E., and Birungi, Z. S. (2019). “Advances in bioremediation of toxic heavy metals and radionuclides in contaminated soil and aquatic systems,” in Bioremediation of industrial waste for environmental safety: volume II: biological agents and methods for industrial waste management (Springer).

Ojedokun, A. T., and Bello, O. S. (2016). Sequestering heavy metals from wastewater using cow dung. Water Resour. Industry 13, 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.wri.2016.02.002

Okafor, V. N., Omokpariola, D. O., Obumselu, O. F., and Eze, C. G. (2023). Exposure risk to heavy metals through surface and groundwater used for drinking and household activities in ifite ogwari, southeastern Nigeria. Appl. Water Sci. 13, 105. doi:10.1007/s13201-023-01908-3

Onipe, T. A. (2018). Geogenic fluoride source in groundwater: a case study of siloam village, Limpopo province, South Africa. Doctoral Dissertation.

Onipe, T., Edokpayi, J. N., and Odiyo, J. O. (2021). Geochemical characterization and assessment of fluoride sources in groundwater of siloam area, Limpopo province, South Africa. Sci. Rep. 11, 14000. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93385-4

Ouro-Sama, K., Dassanayake, G., and Kulesza, A. (2021). Low-cost adsorbents for heavy metal removal: A mini review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 24, 101896. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2021.101896

Patience, M. T., Elumalai, V., Rajmohan, N., and Li, P. (2021). Occurrence and distribution of nutrients and trace metals in groundwater in an intensively irrigated region, luvuvhu catchment, South Africa. Environ. Earth Sci. 80, 752. doi:10.1007/s12665-021-10021-0

Qi, B., and Aldrich, C. (2008). Biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions with tobacco dust. Bioresour. Technol. 99 (13), 5595–5601. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.10.042

Rammal, M. E., Haddad, R., and Khalil, A. (2025). Emerging trends in sustainable adsorbent materials for contaminant removal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 32, 4412–4426. doi:10.1007/s11356-024

Rouhani, S., Azizi, S., Kibechu, R. W., Mamba, B. B., and Msagati, T. A. (2020). Laccase immobilized Fe3O4-Graphene oxide nanobiocatalyst improves stability and immobilization efficiency in the green preparation of sulfa drugs. Catalysts 10 (4), 459. doi:10.3390/catal10040459

Sunkari, E. D., Adams, S. J., Okyere, M. B., and Bhattacharya, P. (2022). Groundwater fluoride contamination in Ghana and the associated human health risks: any sustainable mitigation measures to curtail the long term hazards? Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 16, 100715. doi:10.1016/j.gsd.2021.100715

Vujić, M., Nikić, J., Vijatovic Petrovic, M., Pejin, Đ., Watson, M., Rončević, S., et al. (2025). End-of-Life management strategies for Fe–Mn nanocomposites used in arsenic removal from water. Polymers 17 (10), 1353. doi:10.3390/polym17101353

Yadav, M., Singh, G., and Jadeja, R. (2021). Fluoride contamination in groundwater, impacts, and their potential remediation techniques. Groundw. Geochemistry Pollution Remediation Methods, 22–41. doi:10.1002/9781119709732.ch2

Keywords: low-cost adsorbents, fluoride and heavy metals removal, water treatment, South Africa, rural water supply

Citation: Fagbohun TR, Okechukwu VO, Adelusi OA and Okonkwo JO (2025) Comparative systematic review of low-cost adsorbents for fluoride and heavy metal removal in rural water supplies in South Africa (1 January 2000 – 30 June 2025). Front. Environ. Sci. 13:1718081. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2025.1718081

Received: 11 October 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025;

Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Arbind Kumar Patel, Jawaharlal Nehru University, IndiaReviewed by:

Gamal Ammar, City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications, EgyptBerhane Desta Gebrewold, Bio and Emerging Technology Institute (BETin), Ethiopia

Copyright © 2025 Fagbohun, Okechukwu, Adelusi and Okonkwo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Viola O. Okechukwu, dmlvbGEub2thZm9yMTVAZ21haWwuY29t

Temitope R. Fagbohun

Temitope R. Fagbohun Viola O. Okechukwu

Viola O. Okechukwu Oluwasola A. Adelusi1

Oluwasola A. Adelusi1