Abstract

Sustainable management of forest ecosystems requires the use of reliable and easy to implement biodiversity and naturalness indicators. Tree-related microhabitats (TreMs) can fulfill these roles as they harbor specialized species that directly or indirectly depend on them, and are generally more abundant and diverse in natural forests or forests unmanaged for several decades. The TreM concept is however still recent, implying the existence of many knowledge gaps that can challenge its robustness and applicability. To evaluate the current state of knowledge on TreMs, we conducted a systematic review followed by a bibliometric analysis of the literature identified. A total of 101 articles constituted the final corpus. Most of the articles (60.3%) were published in 2017 or after. TreM research presented a marked lack of geographical representativity, as the vast majority (68.3%) of the articles studied French, German or Italian forests. The main themes addressed by the literature were the value of TreMs as biodiversity indicators, the impact of forest management on TreMs and the factors at the tree- and stand-scales favoring TreMs occurrence. Old-growth and unmanaged forests played a key role as a “natural” forest reference for these previous themes, as TreMs were often much more abundant and diverse compared to managed forests. Arthropods were the main phylum studied for the theme of TreMs as biodiversity indicators. Other more diverse themes were identified, such as restoration, remote sensing, climate change and economy and there was a lack of research related to the social sciences. Overall, current research on TreMs has focused on assessing its robustness as an indicator of biodiversity and naturalness at the stand scale. The important geographical gap identified underscores the importance of expanding the use of the TreMs in other forest ecosystems of the world. The notable efforts made in recent years to standardize TreM studies are an important step in this direction. The novelty of the TreM concept can partially explain the thematic knowledge gaps. Our results nevertheless stress the high potential of TreMs for multidisciplinary research, and we discuss the benefits of expanding the use of TreMs on a larger spatial scale.

Introduction

Forests play a key-role in solving the current global issue of biodiversity erosion, as they host about two-thirds of the world's terrestrial biodiversity (World Commission on Forests Sustainable Development, 1999). However, assessing the ability of sustainable forest management strategies to maintain biodiversity is complex (Drapeau et al., 2009; Blicharska et al., 2020) as exhaustive biodiversity surveys are generally time- and money-consuming. Consequently for practical purposes, and despite contradictory evidence of cross-taxa congruent biodiversity patterns in forests (Burrascano et al., 2018; Larrieu et al., 2018a), biodiversity surveys are often focused on a small group of taxa, generally vertebrates and vascular plants. This limits their applicability in forest management and conservation. Reliable biodiversity proxies for undersurveyed taxa, which can be easily monitored, are therefore critically required to assess the sustainability of the current anthropogenic impacts on biodiversity in forest ecosystems. Forest management for timber production, and more generally anthropogenic disturbances, have caused an important degradation of forests worldwide (Puettmann et al., 2009), threatening the habitats, functions, and services forest ecosystems provide. Hence, remnant natural forests now play a key role as references for naturalness in degraded forest landscapes, providing knowledge on development processes of critical habitat elements to be restored in managed forests (Watson et al., 2018).

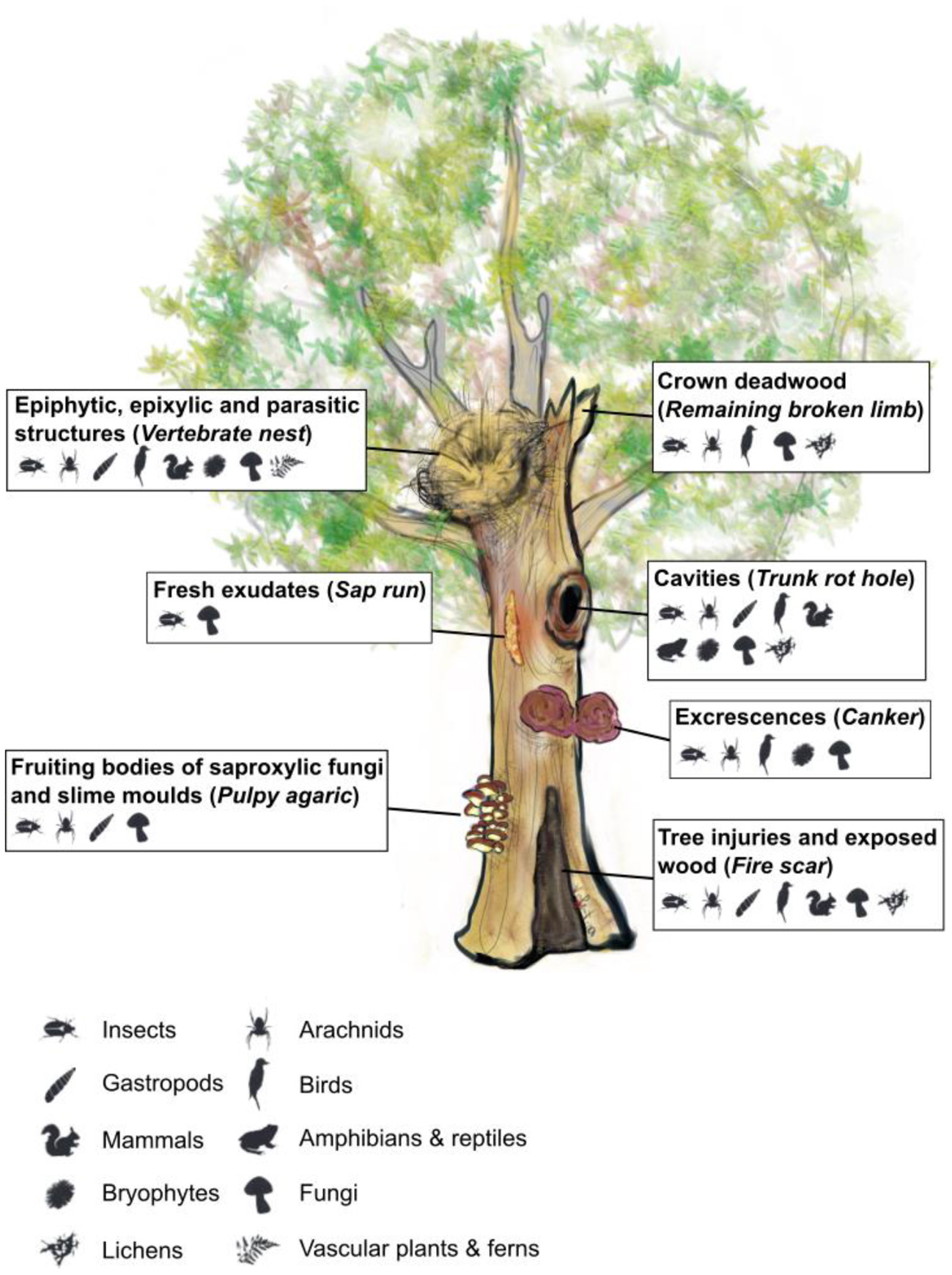

Evaluating the success of “closer to nature” forest management strategies (Messier et al., 2015; Puettmann et al., 2015) requires the use of reliable yet easily applicable indicators. Tree-related microhabitats (TreMs) can fulfill the roles of biodiversity and naturalness indicators. They are defined as “all distinct and well-delineated structures occurring on living or standing dead trees, that constitute a particular and essential substrate or life site for species or species communities during at least a part of their life cycle to develop, feed, shelter or breed” (Larrieu et al., 2018b). They can be regrouped in seven main forms, based on morphological characteristics, and use by the associated taxa: (i) cavities, (ii) tree injuries and exposed wood, (iii) crown deadwood, (iv) excrescences, (v) fruiting bodies of saproxylic fungi and fungi-like organisms, (vi) epiphytic, epixylic, and parasitic structures (e.g., nest), and (vii) exudates (Figure 1; Larrieu et al., 2018b). They thus represent a wide variety of structures, necessary for many animal, vegetal or fungal species, and several species are highly-dependant on specific TreMs. Some TreMs such as cavities can host several hundred taxa, some of which can also live in other TreMs or on deadwood. In contrast, dendrotelms (a cup-shaped concavity that retains water) host very few taxa; however, most of these taxa are strictly associated with this type of TreM (Dajoz, 2007), and dendrotelms are more generally an important resource for hydration and nutrition of animal species (Gossner et al., 2020; Kirsch et al., 2021). For this reason, TreMs have proven to be indicators of forest biodiversity (Paillet et al., 2018; Larrieu et al., 2019; Basile et al., 2020), although the direct links between TreMs and species occurrence at the stand scale are not always clear (Asbeck et al., 2021a). The richness and diversity of TreMs, as well as the occurrence of specific types, are also relevant indicators of naturalness or old-growthness (Winter and Möller, 2008; Michel and Winter, 2009; Vuidot et al., 2011; Larrieu et al., 2012; Paillet et al., 2017; Asbeck et al., 2021b). While some TreMs have been studied for a long time, such as dendrotelms (Kitching, 1971) or cavities (Wesołowski, 2007), the concept of a list of different microhabitats that represent a significant part of the forest biodiversity is more recent. Indeed, the novelty with the current “TreM concept” is to consider TreMs at the stand scale, as a key set of resources for a much wider range of taxa, which are functionally linked to each other as well as to other elements such as deadwood. This more holistic approach therefore aims at, among other purposes, assessing and orienting forest management strategies that conserve biodiversity.

Figure 1

Illustration of the seven TreM forms defined by Larrieu et al. (2018b), and link between TreM forms and taxa in European temperate and Mediterranean forests. Italic text in brackets indicates the specific TreM types represented here. Taxa pictures indicates that several species of the taxonomic group occur; these species are not necessarily strictly associated with the TreM group. Adapted from Larrieu et al. (2018b) and Bütler et al. (2020). Tree drawing by Valentina Buttò and taxa drawings by Celine Emberger.

Forest management and biodiversity conservation both benefit from exchanges among researchers and practitioners, and more generally from the transferability of concepts and the assessment of their robustness in different contexts. A quick look at the literature on TreMs suggests, however, that the concept has developed mainly in Europe, and particularly in the temperate and Mediterranean regions of that continent (Kraus et al., 2016; Larrieu et al., 2018b). Trees and forests in this area demonstrate certain characteristics (e.g., tree size, TreM development dynamics, history of anthropogenic disturbance) that may differ from other territories and current knowledge on TreMs may not be directly applicable outside the regions where they are currently studied. For example, Martin et al. (2021a) highlighted that the TreMs size thresholds commonly used to survey TreMs in temperate forests may not be easily applicable in some boreal regions due to the smaller tree size. Evaluations of the applicability of the TreM concept by comparing new territories (United Sates, Iran) with European forests have however been conducted in recent years (Asbeck et al., 2020a; Jahed et al., 2020). In line with these efforts, this article conducts a systematic review of the scientific literature on TreMs to identify research gaps, for example in terms of geographical coverage or themes. Identification of the scope and limits of the current knowledge on TreMs will facilitate the prioritization of research objectives and the application of this concept in sustainable management of forest ecosystems. We assumed that (1) the study of TreMs currently covers a limited geographical area and few studies are available outside of Europe, and that (2) due to the recent nature of this concept, the majority of studies on TreMs have focused on validating their role as an indicator of biodiversity and naturalness.

Materials and Methods

Systematic Review

The systematic review was conducted in three steps. First, we performed a search on the specialized search engines Scopus (www.scopus.com) and Web of Science (www.webofscience.com) to find literature referring to TreMs. Identifying the relevant keywords for the search is a key part of this step (Atkinson and Cipriani, 2018; Foo et al., 2021). A wide diversity of terms, however, has been used to refer to TreMs before the terminology became more homogenized in recent years. We therefore relied on the literature already known by the authors to identify the different terms that have been used to refer to TreMs, here presented in the singular form: TreM (Jahed et al., 2020), tree related microhabitat (Larrieu et al., 2021), tree microhabitat (Paillet et al., 2015), bark microhabitat (Michel et al., 2011), microhabitat (Winter and Möller, 2008), microhabitat-bearing tree (Regnery et al., 2013b), dendromicrohabitat (Madera et al., 2017), special tree structure (Winter et al., 2005) or structural diversity characteristic (Lilja and Kuuluvainen, 2005). We used wildcards (*) to account for various word spellings. Because some of the identified terms were relatively generic (e.g., “microhabitat”) or can be a part of another word (e.g., “TreM”), we also add as a constraint a 5-words proximity with “tree*” or “forest*,” Similarly, for the terms “special tree structure” and “structural diversity characteristics,” constrained these words as a single expression rather than individual words. The literature search was conducted the 27th September 2021 using the following query, here written following the Scopus syntax:

[TITLE-ABS-KEY ((trem OR trems) W/5 (tree* OR forest*)) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (tree W/5 microhabitat*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (dendromicrohabitat*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (bark W/5 microhabitat*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (microhabitat W/1 bearing W/1 tree*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (structural W/1 diversity W/1 characteristic*) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (special W/1 tree W/1 structure*)].

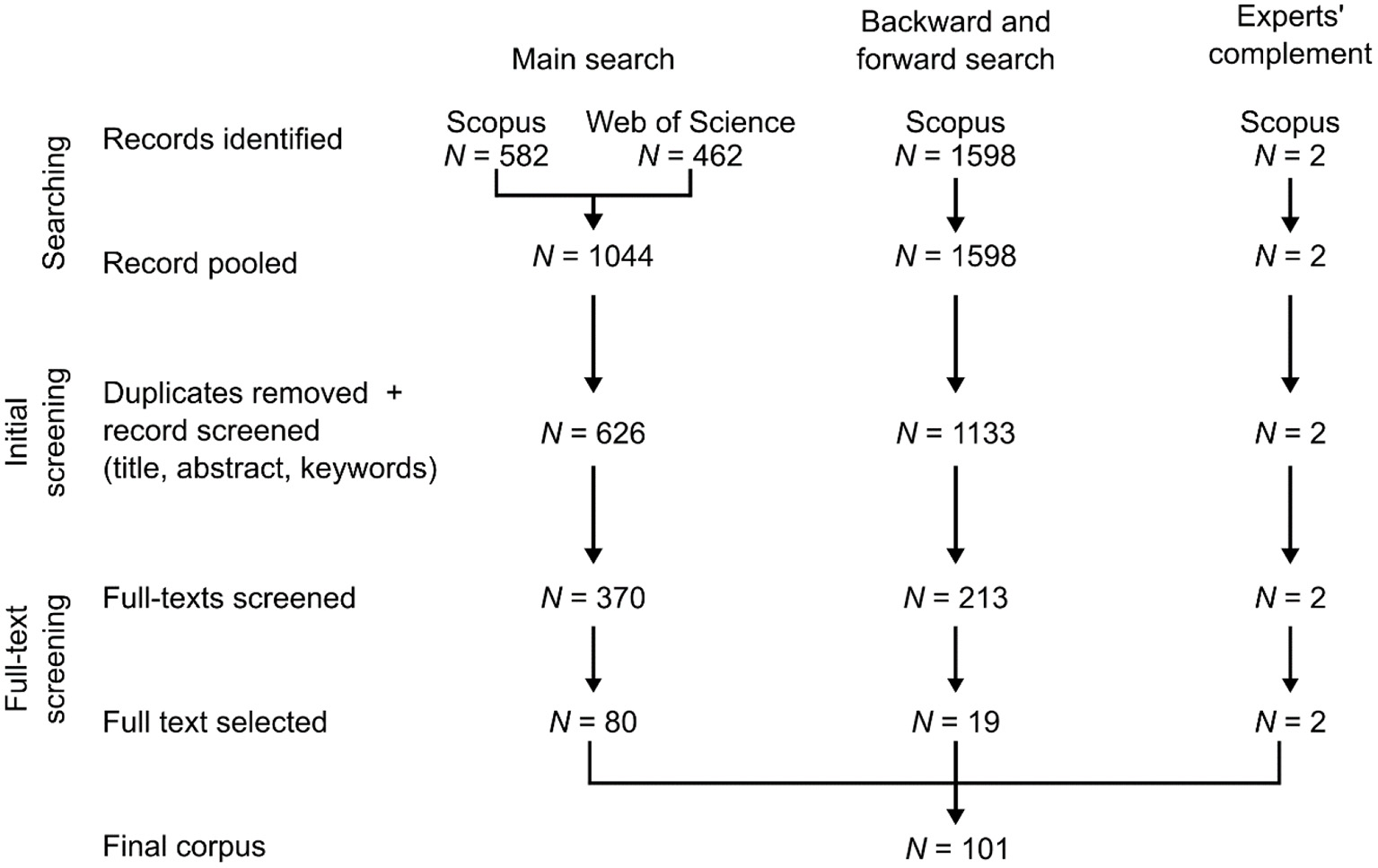

Once the duplicates removed, a total of 626 articles were identified at this stage (Figure 2). We then read the title and the abstract, as well as the full text if necessary, of each articles to determine if they fulfilled the following criteria (hereafter, “selection criterion”): (i) research article; we nevertheless identified literature reviews related to TreMs for a subsequent step, (ii) TreMs had to be studied, not just mentioned, (iii) at least 2 TreM forms following the typology of Larrieu et al. (2018b) were considered, although without any size or abundance limits; this criterion serves to remove all articles focusing specifically on one type of TreM [e.g., cavities Remm and Lõhmus (2011)], without considering TreMs as concepts, (iv) all TreM forms studied are recognized as TreMs as defined by Larrieu et al. (2018b), and not as an element without its own habitat value. A single researcher (M. Martin) reviewed all the articles, but articles for which the correspondence to the criteria was uncertain were identified so that the final selection was made among all the authors. A total of 80 articles constituted the corpus at the end of the first step (Figure 2).

Figure 2

PRISMA diagram of the systematic review conducted.

It was possible that some relevant articles related to TreMs were not identified in the previous step. For this reason, Foo et al. (2021) suggest to perform a backward and forward search based on pertinent reviews and landmark articles, i.e., a review of the references that are cited or that cite these selected articles. We thus performed a backward and forward search as a second step of our review. We identified three relevant literature reviews that specifically study TreMs (Larrieu et al., 2018b; Asbeck et al., 2021a; Kõrkjas et al., 2021a). For other landmark articles that were not reviews, we selected ten research articles presenting a detailed TreM typology [i.e., more than four different TreM forms, so more than half of the seven forms identified by Larrieu et al. (2018b)] and published before Larrieu et al. (2018b) homogenized typology (Winter and Möller, 2008; Michel and Winter, 2009; Michel et al., 2011; Vuidot et al., 2011; Larrieu and Cabanettes, 2012; Regnery et al., 2013a; Larrieu et al., 2014a,b, 2017; Winter et al., 2015). We considered these ten articles as landmark research, because they were more likely to synthetize current knowledge of their time on a wide diversity of TreMs, and to be cited by further TreM-studies. The backward and forward search led to the identification of 1,133 articles, including 543 articles that were absent from the first step. We used the same method and criteria as before to make the article selection. A total of 19 articles were added to the corpus at the end of the second step (total number of articles in the corpus = 99; Figure 2).

As a third step, we finally compared the results of the corpus with the literature related to TreMs already known by the authors and fulfilling our selection criterion. We identified two articles that were absent from the corpus (Larrieu et al., 2019; Gosselin and Larrieu, 2020), probably because TreMs were studied through the Index of Biodiversity Potential (Larrieu and Gonin, 2008), an index that considers TreMs among other forest attributes (Figure 2). These articles were consequently added to the corpus (total number of articles in the corpus = 101).

Bibliometric Analysis

To better highlight the general context of TreMs-related literature we conducted a bibliometric analysis (Donthu et al., 2021) on the 101 articles selected for our corpus. For each article, we extracted the authors name, the date of publication, the “Keywords Plus” (i.e., the keywords defined by the publisher) as well as the countries covered by the data. We consider the countries covered by the data rather than the country of the corresponding author, which is commonly used in bibliometric analyses, because the latter is not necessarily the same as the country studied and several countries can be covered by the same study. Further, we chose to use the Keywords Plus rather than the authors' Keywords because the former are considered to better describe the articles than the latter (Zhang et al., 2016). There were also fewer articles in the corpus from which keywords plus were unavailable (n = 14) compared to authors keywords (n = 22).

The manual creation of a thesaurus based on the keywords plus also allows a better grouping of the themes that revolve around a subject (Yang et al., 1998). First, we identified and grouped keywords whose difference was only due to spelling (e.g., “tree” and “trees,” “Abies alba” and “Abies alba Mill”). Second, we selected only the keywords that occurred at least three times in the corpus. Preliminary tests showed that lowering this threshold strongly increased the occurrence of unique themes, causing noise in the subsequent analyses. Third, we indexed the keywords when deemed relevant to avoid synonyms and to highlight explicit links [e.g., “Abies alba” = “Species/Genera (Tree), “Arthropod” = “Fauna (Invertebrate),” Aitchison et al. (2000)]. Depending on the quality of the links between words, different degrees of clustering were given to the keywords. For example, the word fauna was treated separately because it is a very generic word. On the contrary, the words arthropod, beetle, coleopteran, or diptera were associated with the group Fauna (Invertebrate).

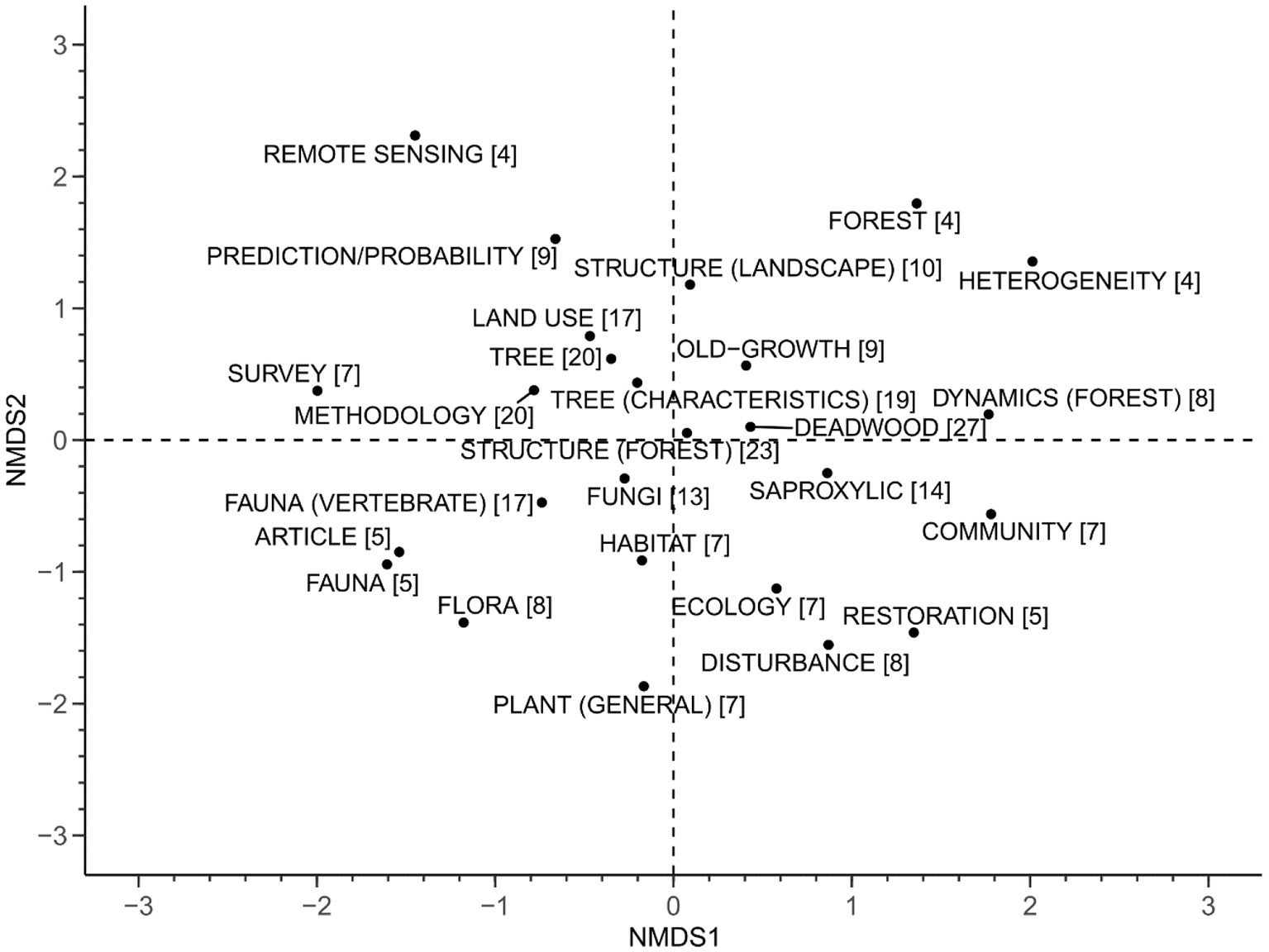

To analyze the co-occurrence of the different themes identified in the thesaurus, we performed a Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis based on the theme occurrence within the articles. To limit the noise caused by rare or very frequent themes we first removed themes for which the frequency in the corpus was below the 20th percentile or above the 80th percentile of theme frequency. We applied a NDMS on two dimensions using the Jaccard distance and 1,000 iterations, with the metaMDS function of the vegan R-package (Oksanen et al., 2018).

To analyze the authors co-occurrence, we first identified the numbers of articles published by each author in the corpus. For this analysis we kept only the authors that published at least three articles in the corpus, as we considered that a lower number of articles published meant low or no co-occurrence. The co-occurrence of the selected authors was identified using Veech's probabilistic model of species co-occurrence (Veech, 2013). The analysis was performed using the cooccur function of the cooccur R-package (Griffith et al., 2016). All the analyses were performed using the R programming language (R Core Team, 2019).

Results

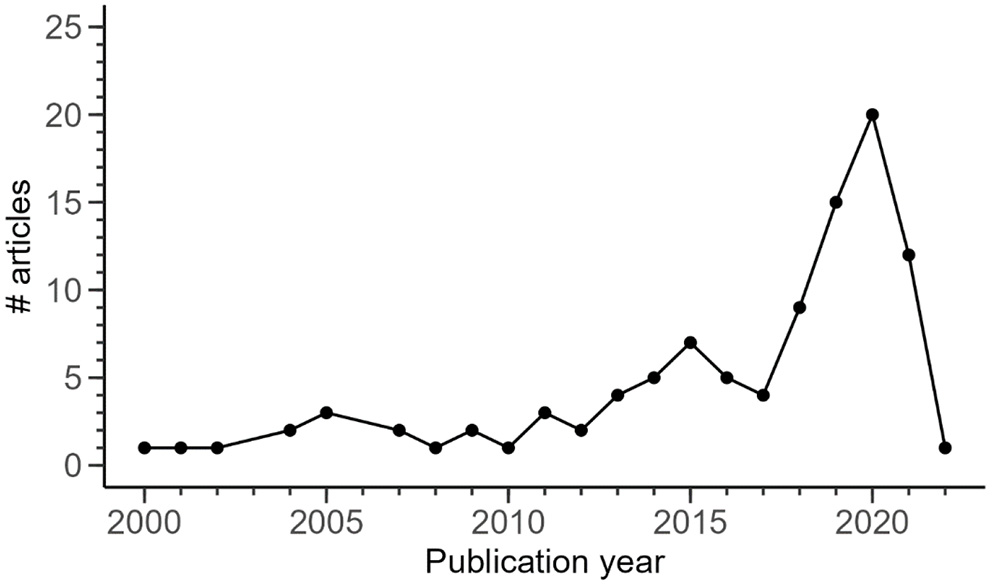

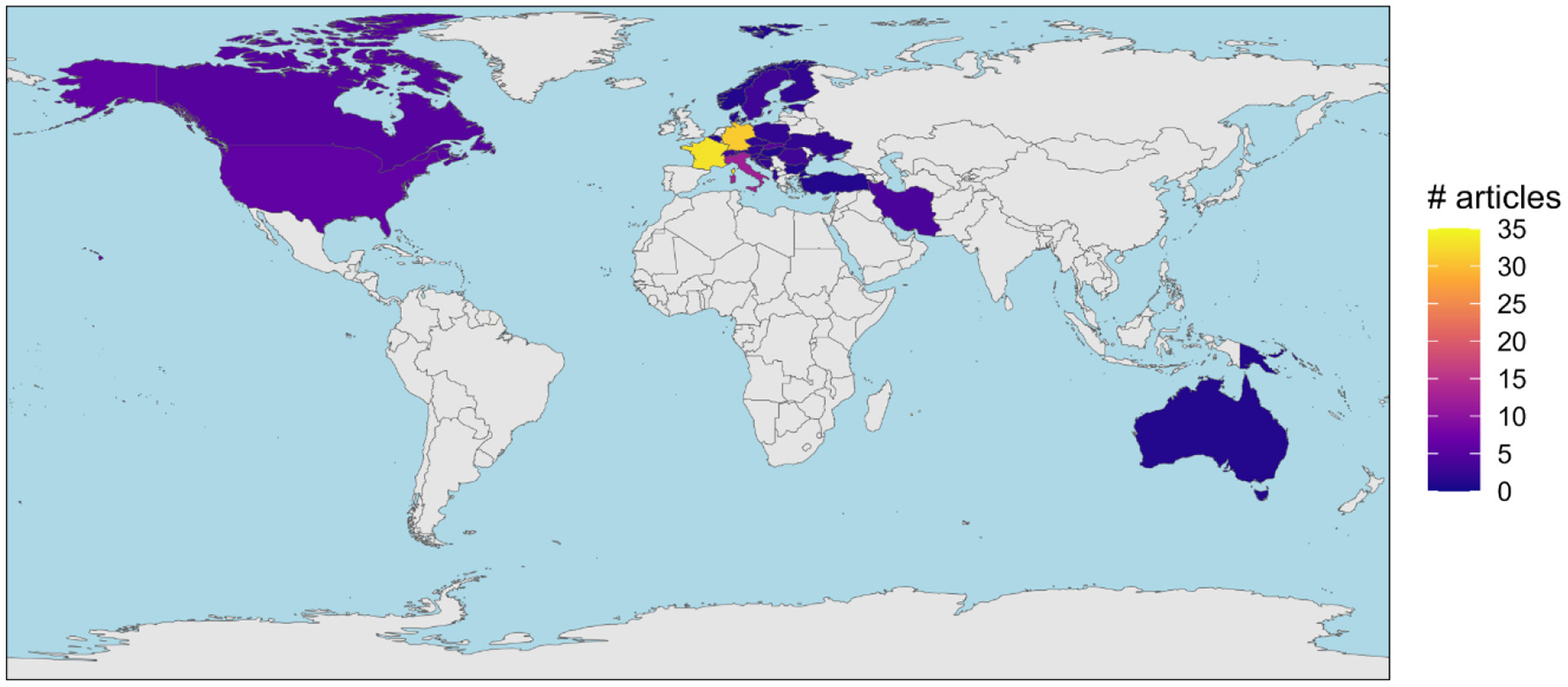

The oldest article identified in the corpus was published in 2000 (Lindenmayer et al., 2000; Figure 3). The number of articles published annually remained low (<4 articles/year) until 2013, where it progressively increased to reach a maximum in 2020 (20 articles published). The study areas of the articles from the corpus were located in 30 different countries (Supplementary Material 1). The dominant countries were France (32.6%), Germany (30.6%) and Italy to a lower extent (11.8%) (Figure 4). For all of the 26 remaining countries, we identified between 1 and 6 articles studying TreMs on their territory.

Figure 3

Number of articles from the corpus by publication year. The year 2021 was still incomplete at the time the bibliometric study was conducted (27th September 2021), which may partly explain a lower value. One article already available at the date of the bibliometric study belongs to an issue for which the publication year is 2022 (Przepióra and Ciach, 2022), explaining the unique value observed for this year.

Figure 4

Map of the number of articles from the corpus covering world countries. Gray fill indicates no article identified for the country, blue indicates seas and oceans.

A total of 351 authors contributed to the articles from the corpus. Among them, 45 authors published at least three articles (12.8% of the total number of authors; Table 1). Using Veech's probabilistic model of species co-occurrence, we identified three author groups: (A) Larrieu L, Cabanettes A, Bouget C, and Deconchat M (all authors main affiliations located in France), (B) Asbeck T and Bauhus J (all authors main affiliations located in Germany), and (C) Paillet Y, Gosselin F, and Archaux F (all authors main affiliations located in France) (Table 1, Supplementary Material 2). For all the 35 remaining authors, we identified no significant associations.

Table 1

| Rank | Author | # Articles | Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Larrieu L | 20 | A |

| 2 | Bouget C | 13 | A |

| 3 | Paillet Y | 12 | C |

| 4 | Asbeck T | 10 | B |

| 5 | Cabanettes A | 10 | A |

| 6 | Bauhus J | 9 | B |

| 7 | Marchetti M | 9 | |

| 8 | Winter S | 9 | |

| 9 | Gosselin F | 7 | C |

| 10 | Lombardi F | 7 | |

| 11 | Tognetti R | 7 | |

| 12 | Archaux F | 6 | C |

| 13 | Muller J | 6 | |

| 14 | Svoboda M | 6 | |

| 15 | Basile M | 5 | |

| 16 | Deconchat M | 5 | A |

| 17 | Parisi F | 5 | |

| 18 | Parmain G | 5 | |

| 19 | Gilg O | 4 | |

| 20 | Kozak D | 4 | |

| 21 | Pyttel P | 4 | |

| 22 | Augustynczik ALD | 3 | |

| 23 | Campanaro A | 3 | |

| 24 | Chirici G | 3 | |

| 25 | Courbaud B | 3 | |

| 26 | Debaive N | 3 | |

| 27 | Frey J | 3 | |

| 28 | Guilbert E | 3 | |

| 29 | Janda P | 3 | |

| 30 | Jonker M | 3 | |

| 31 | Kameniar O | 3 | |

| 32 | Kraus D | 3 | |

| 33 | Lachat T | 3 | |

| 34 | Lasserre B | 3 | |

| 35 | Martin M | 3 | |

| 36 | Michel AK | 3 | |

| 37 | Mikolas M | 3 | |

| 38 | Nagel TA | 3 | |

| 39 | Nusillard B | 3 | |

| 40 | Sarthou JP | 3 | |

| 41 | Schuck A | 3 | |

| 42 | Storch I | 3 | |

| 43 | Svitok M | 3 | |

| 44 | Synek M | 3 | |

| 45 | Trotsiuk V | 3 |

Authors that published at least three articles in the corpus and co-occurrence group.

A same letter indicates a same co-occurrence group.

We indexed the Keywords Plus in a total of 40 themes (Table 2, Supplementary Material 3), with four of them occurring in more than half of the articles from the corpus for which keyword plus were available (Management (Forest), Biodiversity, Microhabitat and Country/Territory) and five of them occurring in three articles or less (Climate, Lichen, Natural, Climate change and Economy). A total of 26 themes, identified in 76 articles were kept for the NMDS (Figure 5). We observed that the NMDS1 axis distributed the themes in two main groups: general forest attributes for the positive values [e.g., Heterogeneity, Dynamics (Forest)], and forest species or their monitoring [e.g., Fauna (Vertebrate), Flora, Fauna, Survey] for the negative values. This suggest that this axis distinguishes studies focused on different scales, from the landscape (positive values) to local habitat (negative values). For the NMDS2 axis, positive values regrouped themes related to the methodology (e.g., Prediction/Probability, Methodology, Survey) while negatives values grouped more ecological concepts (e.g., Ecology, Community, Disturbance). This suggests that this second axis discriminates studies related to the methodological aspects of TreMs research (positive values) from those that are more centered on the ecological perspective. As a result, the combination of the two NMDS axes divides the themes in four main groups: forest complexity and heterogeneity (positive NDMS1 and NDMS2 values), general ecological concepts (positive NDMS1 and negative NDMS2 values), methodological approaches (negative NDMS1 and positive NDMS2 values), and biodiversity (negative NDMS1 and NDMS2 values).

Table 2

| Rank | Theme | # Articles | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Management (forest) | 60 | 59.4 |

| 2 | Biodiversity | 59 | 58.4 |

| 3 | Microhabitat | 57 | 56.4 |

| 4 | Country/territory | 53 | 52.5 |

| 5 | Species/genera (tree) | 49 | 48.5 |

| 6 | Indicator | 48 | 47.5 |

| 7 | Ecosystem | 43 | 42.6 |

| 8 | Protection/conservation | 42 | 41.6 |

| 9 | Fauna (invertebrate) | 28 | 27.7 |

| 10 | Deadwood | 27 | 26.7 |

| 11 | Structure (forest) | 23 | 22.8 |

| 12 | Methodology | 20 | 19.8 |

| 13 | Tree | 20 | 19.8 |

| 14 | Tree (characteristics) | 19 | 18.8 |

| 15 | Fauna (vertebrate) | 17 | 16.8 |

| 16 | Land use | 17 | 16.8 |

| 17 | Saproxylic | 14 | 13.9 |

| 18 | Fungi | 13 | 12.9 |

| 19 | Structure (landscape) | 10 | 9.9 |

| 20 | Old-growth | 9 | 8.9 |

| 21 | Prediction/probability | 9 | 8.9 |

| 22 | Disturbance | 8 | 7.9 |

| 23 | Dynamics (forest) | 8 | 7.9 |

| 24 | Flora | 8 | 7.9 |

| 25 | Community | 7 | 6.9 |

| 26 | Ecology | 7 | 6.9 |

| 27 | Habitat | 7 | 6.9 |

| 28 | Plant (general) | 7 | 6.9 |

| 29 | Survey | 7 | 6.9 |

| 30 | Article | 5 | 5.0 |

| 31 | Fauna | 5 | 5.0 |

| 32 | Restoration | 5 | 5.0 |

| 33 | Forest | 4 | 4.0 |

| 34 | Heterogeneity | 4 | 4.0 |

| 35 | Remote sensing | 4 | 4.0 |

| 36 | Climate | 3 | 3.0 |

| 37 | Lichen | 3 | 3.0 |

| 38 | Natural | 3 | 3.0 |

| 39 | Climate change | 2 | 2.0 |

| 40 | Economy | 2 | 2.0 |

Number and frequency of articles presenting themes identified from the Keywords plus.

The frequency was calculated using the total number of articles for which Keywords plus were available (n = 84 articles), and not the total number of articles in the corpus.

Figure 5

Biplot of the results of the NMDS on the first and second ordination axes (NMDS1 and NDMS2, respectively). Black dots represent themes (n = 26), and the number in brackets indicates the number of articles for which the theme was identified.

Discussion

Tree-Related Microhabitats: A Recent and Developing Ecological Concept

Research on TreMs is concentrated in a narrow number of countries and research groups from Western Europe, supporting our first assumption. This small geographic range of the TreM concept is consistent with its relatively young age, as the oldest study identified was published in 2000 (Lindenmayer et al., 2000) and more than half of the articles from the corpus were published in 2017 or after. The lack of consistent TreM terminology before 2008, e.g., special tree structure (Winter et al., 2005) or structural diversity characteristic (Lilja and Kuuluvainen, 2005), illustrates well the juvenile character of this concept. Admittedly, numerous research projects on individual TreM forms existed before 2000, forming the foundations of what will become the TreM concept. For example, Ricarte et al. (2009) in Mediterranean forest or Ranius and Jansson (2000) in Sweden provided detailed reviews of the different TreMs individually used by saproxylic beetles and hoverflies. During the literature search, we also identified articles studying one specific TreM form in regions for which there was little or no other TreM research, such as Africa (Pringle et al., 2015), South America (Whitfield et al., 2005; Ibarra et al., 2020) or Asia (Patel et al., 2021). Ecological research generally suffers from an important lack of representativeness at the global scale, with Global North countries being dramatically overrepresented in part because of better access to funding sources (Martin et al., 2012; Wohner et al., 2021). The fact that most TreM-related research comes from Western European countries is therefore consistent with this global trend.

Current research on TreMs focuses primarily on the themes of the value of TreMs as biodiversity indicators (37.6% of the corpus; Table 3) or the effect of forest management on TreMs abundance and diversity (34.5% of the corpus; Table 3), supporting our second assumption. These main themes are consistent with the core concept of TreMs, which has been developed as an indicator of forest biodiversity that can be integrated into routine forest surveys (Larrieu et al., 2018b, 2021; Reise et al., 2019; Asbeck et al., 2021a). The importance of the themes “Conservation/protection,” “Fauna (invertebrate),” and “Deadwood” is congruent with both the current threats to many species caused by the depletion of deadwood in European managed forests (Stokland et al., 2012; Burrascano et al., 2013). It is also consistent with the lack of knowledge regarding invertebrate populations compared to vertebrates and vascular plants (Newbold, 2010; Feldman et al., 2020). Interestingly, themes related to fungi, bryophytes and epiphytes (here regrouped under the theme “Flora”) as well as lichen were far less abundant. This implies that knowledge linking these taxa with TreMs is still scarce. It is important to note, however, that research on the relationship between deadwood (standing or downed) and fungi or lichens is abundant (Stokland et al., 2012). It seems likely that much of this knowledge could be at least partially applied to the TreM concept. Similarly, lichens and fungi can be considered in certain cases as TreMs, so it will be important to distinguish between studies where these taxa are considered as TreMs per se or as TreM users.

Table 3

| Topic addressed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article |

Relevance as

biodiversity indicator |

Impact of

management |

Factors

explaining TreM occurrence |

Managed vs.

Natural |

Managed vs.

Unmanaged |

Other topics |

| Asbeck et al. (2019) | X | X | X | |||

| Asbeck et al. (2020b) | X | X | ||||

| Asbeck et al. (2020a) | X | |||||

| Asbeck et al. (2021b) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Asbeck et al. (2021c) | X | |||||

| Augustynczik et al. (2019) | X | X | ||||

| Augustynczik et al. (2020) | X | X | ||||

| Bagaram et al. (2018) | X | |||||

| Basile et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Bouget et al. (2013) | X | |||||

| Bouget et al. (2014b) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Bouget et al. (2014a) | X | X | ||||

| Burgar et al. (2015) | X | X | ||||

| Buse et al. (2007) | X | |||||

| Cosyns et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Cosyns et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Courbaud et al. (2017) | X | |||||

| Cours et al. (2021) | X | |||||

| Demant et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Frey et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Fritz and Heilmann-Clausen (2010) | X | |||||

| Gosselin and Larrieu (2020) | X | |||||

| Großmann et al. (2018) | X | X | ||||

| Großmann et al. (2020) | X | X | X | |||

| Herrault et al. (2016) | X | |||||

| Jahed et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Janssen et al. (2016) | X | |||||

| Joa et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Johann and Schaich (2016) | X | X | ||||

| Kameniar et al. (2021) | X | |||||

| Khanalizadeh et al. (2020) | X | X | X | |||

| Knuff et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Kozák et al. (2021) | X | |||||

| Kozák et al. (2018) | X | X | ||||

| Kõrkjas et al. (2021b) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Langridge et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Larrieu et al. (2009) | X | |||||

| Larrieu and Cabanettes (2012) | X | |||||

| Larrieu et al. (2012) | X | X | ||||

| Larrieu et al. (2014a) | X | |||||

| Larrieu et al. (2014b) | X | X | ||||

| Larrieu et al. (2015) | X | |||||

| Larrieu et al. (2017) | X | X | ||||

| Larrieu et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Larrieu et al. (2021) | X | X | ||||

| Lassauce et al. (2013) | X | X | ||||

| Leidinger et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Lelli et al. (2019) | X | X | X | |||

| Lilja and Kuuluvainen (2005) | X | X | ||||

| Lindenmayer et al. (2000) | X | |||||

| Lombardi et al. (2018) | X | |||||

| Martin and Raymond (2019) | X | X | ||||

| Martin et al. (2021a) | X | |||||

| Martin et al. (2021b) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Marziliano et al. (2021) | X | X | X | |||

| Menkis et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Michel and Winter (2009) | X | X | X | |||

| Michel et al. (2011) | X | |||||

| Müller et al. (2014) | X | |||||

| Ouin et al. (2015) | X | X | ||||

| Ozdemir et al. (2018) | X | |||||

| Paillet et al. (2015) | X | |||||

| Paillet et al. (2017) | X | X | X | |||

| Paillet et al. (2018) | X | X | X | |||

| Paillet et al. (2019) | X | X | ||||

| Parisi et al. (2016) | X | |||||

| Parisi et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Parisi et al. (2020a) | X | |||||

| Parisi et al. (2020b) | X | X | ||||

| Parisi et al. (2021) | X | |||||

| Parmain and Bouget (2018) | X | X | ||||

| Percel et al. (2018) | X | |||||

| Percel et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Plowman et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Prinzing (2005) | X | |||||

| Przepióra and Ciach (2022) | X | |||||

| Puverel et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Regnery et al. (2013a) | X | |||||

| Regnery et al. (2013b) | X | X | X | |||

| Rehush et al. (2018) | X | |||||

| Reise et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Rosenvald et al. (2019) | X | X | X | |||

| Rotheray et al. (2001) | X | |||||

| Rouvinen et al. (2002) | X | X | ||||

| Russo et al. (2004) | X | |||||

| Šálek et al. (2017) | X | |||||

| Santopuoli et al. (2019) | X | |||||

| Santopuoli et al. (2020) | X | |||||

| Schall et al. (2021) | X | X | ||||

| Sefidi and Copenheaver (2020) | X | X | ||||

| Sever and Nagel (2019) | X | X | ||||

| Standovár et al. (2016) | X | |||||

| Vonhof and Gwilliam (2007) | X | |||||

| Vuidot et al. (2011) | X | X | X | |||

| Winter et al. (2005) | X | X | ||||

| Winter and Möller (2008) | X | X | X | |||

| Winter and Brambach (2011) | X | |||||

| Winter et al. (2015) | X | X | X | |||

| Zehetmair et al. (2015b) | X | |||||

| Zehetmair et al. (2015a) | X | |||||

| Zielinski et al. (2004) | X | |||||

List of the articles from the corpus and of the topics addressed.

For reasons of concision, we only included the five most common topics (87% of the articles addressed at least one of these topics) and the remaining ones have been grouped in the “Other topics” column. “Natural forests” refers to forests where there is no evidence of past forest management, while “unmanaged forests” refers to forests that were previously managed but have been abandoned for at least several decades.

There was no theme directly related to the factors explaining TreM presence, abundance and diversity at the tree scale, although it is an important part of TreM research. When reading the manuscripts of the corpus, we notice however that this topic is particularly recurrent (32.7% of the corpus; Table 3). The absence of a specific theme is probably because this subject is often mixed with those of TreMs as an indicator of biodiversity or of the impact of forest management on TreMs (48.4% of the articles identified as addressing the question of TreM presence; Table 3). Overall, larger and senescent or dead tree are more likely to bear many TreMs (e.g., Michel et al., 2011; Paillet et al., 2019; Asbeck et al., 2021b; Kõrkjas et al., 2021b; Martin et al., 2021b;). For a same diameter at breast height, hardwoods tend to present a higher number and diversity of TreMs (Larrieu and Cabanettes, 2012; Bouget et al., 2014a; Paillet et al., 2019; Jahed et al., 2020; Asbeck et al., 2021b; Marziliano et al., 2021). At the stand scale, we generally observe the higher TreMs richness and diversity in old and “natural” (i.e., either old-growth, primary or intact) forests (9.9% of the corpus; Table 3) or formerly managed forests untouched over several decades (16.8% of the corpus; Table 3) compared to younger and managed forests. TreMs in general or some specific TreM types could thus be used as naturalness indicators (Winter, 2012), although the difference between natural or abandoned forest and managed forests can be sometimes more contrasted (Larrieu et al., 2014b; Sever and Nagel, 2019; Martin et al., 2021a,b). For example, the TreM form “Tree injuries and exposed wood” can be abundant in managed forests due to injuries caused by logging activities. Other factors influencing TreMs have been tested, such as local climatic and topographic conditions (Paillet et al., 2019; Asbeck et al., 2021b), spatial patterns (Kozák et al., 2018; Asbeck et al., 2019, 2020b; Martin et al., 2021b) or the influence of tree age (Kõrkjas et al., 2021b), but with less marked results.

Many of the less frequent themes represented rather generic ideas [e.g., “Ecology,” “Habitat,” “Plant (General)”]. Some of these themes, however, indicated specific fields of research that are still little considered from the perspective of TreMs, notably “Remote sensing” (Bagaram et al., 2018; Ozdemir et al., 2018; Rehush et al., 2018; Asbeck et al., 2019; Frey et al., 2020; Santopuoli et al., 2020), “Restoration” (Bouget et al., 2014b; Burgar et al., 2015; Larrieu et al., 2017), “Climate change” (Augustynczik et al., 2019, 2020), and “Economy” (Rosenvald et al., 2019).

We can observe that there are no themes related to social and cultural perspectives of TreM. To a certain extent, it is possible to consider the study related to choice of retention trees, partly based on TreMs, between different professional groups in “marteloscopes” (i.e., tree marking training sites) as social research (Cosyns et al., 2019, 2020; Santopuoli et al., 2019; Joa et al., 2020). TreMs and tree defects are indeed two close concepts (Martin and Raymond, 2019), that can result in conflicts between forest users as they are seen from different perspectives (e.g., production, conservation, aesthetic). The important cultural and social values of very large trees and natural forests, i.e., tree and forests more likely to exhibit TreMs, is also internationally recognized (Blicharska and Mikusiński, 2014; Watson et al., 2018). This result hence underscores the still underdeveloped potential of TreMs for social sciences, e.g., in terms of importance to Indigenous communities or influence on the feeling of naturalness.

The low frequency of the “Old-growth” and “Natural” themes can result to a certain extent from the scarcity of natural forests in Western Europe (Sabatini et al., 2021). This also explains why forests taken as “natural references” were often forests unmanaged for a given period of time (e.g., Vuidot et al., 2011; Packalen et al., 2013; Lelli et al., 2019; Marziliano et al., 2021; Schall et al., 2021). Even if forests, independently of their management status, remain the main study area for TreM research, we identified a few number of studies focusing of TreMs in urban areas (Großmann et al., 2020), in orchards (Parisi et al., 2020b), or in agricultural landscapes (Parmain and Bouget, 2018). This highlights how TreMs can be used in many research projects related to trees, and not only in forests.

Finally, the concentration of TreM research in Europe, and specifically Western Europe, implies that knowledge on TreMs in open biomes with dispersed trees (e.g., savannas) absent or rare in Europe is inexistent. We observed that three forest biomes (i.e., temperate broadleaf or mixed forest, temperate coniferous forest and Mediterranean forest) are overrepresented in the corpus, while for boreal forests a small sample of European and North American research are available (Lilja and Kuuluvainen, 2005; Kõrkjas et al., 2021b; Martin et al., 2021a), and Russia is absent.

Benefits in Expanding the TreM Concept: An Example in North America

As illustrated by our results, few TreM studies have been conducted in North America (Franklin et al., 2000; Zielinski et al., 2004; Vonhof and Gwilliam, 2007; Michel and Winter, 2009; Michel et al., 2011; Martin and Raymond, 2019; Asbeck et al., 2020a; Großmann et al., 2020; Martin et al., 2021a,b). Since most of the authors of this article are more familiar with this area, we will use North America as an example to discuss the value of extending the TreM concept beyond Western Europe. This, however, also applies for all territories with forested biomes similar to those of Western Europe, for example the temperate forests of South America, Asia or Oceania. The numerous research projects conducted in temperate forests in Europe, but also in Iran and North America, point toward emphasizing the relevance of the TreM concept in temperate forests in general. For tropical forests and savannas, specific questions arise with regards to the applicability of the TreM concepts in these ecosystems. For reasons of clarity, this subject is discussed in a dedicated section.

Many North American studies have already identified the microhabitats of specific taxa, for example lichens and fungi (e.g., Goward and Arsenault, 2018), arthropods (e.g., Schowalter, 2017), or birds and mammals (e.g., Drapeau et al., 2009). Similarly, tree defect surveys are regularly used in certain regions of North America to describe forest stand quality and partially capture the TreM concept (Martin and Raymond, 2019). Although TreMs are still little studied as a set of key resources at the stand scale, there is nevertheless a solid scientific basis for the concept, and routine forestry practices already in use could result in the rapid uptake of TreMs in both research and forest management in North America.

Most of Europe's forests either have a long history of management or are recent forests resulting from the abandonment of former agricultural land. Forest management and natural disturbance control also truncate significant parts of natural forests dynamics in European forested landscapes (Kuuluvainen, 2009; Sabatini et al., 2020). In contrast, natural forests and those that have been little influenced by industrialization are much more abundant in North America compared to Europe, particularly in Canada and in the western United States (Ellis, 2011; Venter et al., 2016; Potapov et al., 2017), providing interesting references for TreM research. As a counterpoint to the natural or near-natural forest of North America, the forests of Europe provide varied examples of long-term anthropogenic impacts on TreMs, ranging from close-to-nature silviculture to the alternance between a forest and an agricultural state (Forest Europe, 2015; Jaroszewicz et al., 2019). These studies could therefore help to better estimate how past and current forest management strategies may influence TreMs in North America.

Some forests in North America are defined by specific characteristics that are not found in Europe, but many genera are common to both continents (e.g., Picea, Abies, Acer, or Quercus). This could help to assess the differences, similarities and predispositions for TreM development at the tree genus level. Similarly, the rainforests of northwestern America have few equivalents in Europe in terms of structure and composition, but some tree species have been introduced in Europe for production purposes. Michel et al. (2011) observed very specific bark TreMs (corresponding to the epiphytic, epixylic, and parasitic form) on Douglas fir trees (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) in these forests, due to the large dimensions and characteristics of the bark of this species. These results underline the possibility of further extending our knowledge of TreMs by studying North American forests as new TreMs may be defined and a better understanding of TreMs that are rare in Europe can be gained.

From a social sciences' perspective, there is in North America an increased public awareness to subjects related to trees and forests. Forests must now provide services other than timber production, such as aesthetical, recreational or spiritual services (Sutherland et al., 2016; Siry et al., 2018). Traditional indigenous knowledge is also increasingly considered in forest management planning (McGregor, 2002; Bélisle and Asselin, 2020; Bélisle et al., 2021), with the rationale of moving away from a purely western forest management paradigm. The value of some habitat trees (i.e., cavity trees) is widely recognized in North America (DeGraaf and Shigo, 1985; Tubbs et al., 1987; Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2004) but many TreMs are still seen as defects (Martin and Raymond, 2019). The broader use of the TreM concept in North America could therefore be a step toward improving the balance between ecological, economic and social forest services.

Is the TreM Concept Applicable in Tropical Forests and Savannas?

None of the studies included in our literature review focused on tropical forests or savannas, which may raise questions about the applicability of the TreMs concept in these contexts. This does not mean, however, that TreMs are absent from these areas or have no ecological value. As part of our literature review, we identified studies of species dependent on individual TreMs conducted in the tropical forest (Whitfield et al., 2005; Cockle et al., 2012; Carvajal-Ocampo et al., 2019) and in the savanna (Pringle et al., 2015; Haddad, 2016). It is also likely that new TreMs absent from the Larrieu et al. (2018a) typology can be observed in these areas, such as bromeliads (Rogy et al., 2019). However, the high biodiversity and turnover that can characterize some tropical forests can make it more complex to identify clear links between TreMs and different taxa. Identifying these relationships in comparatively “simpler” temperate forests is already challenging, as they demand adapted TreM and species surveys (Asbeck et al., 2021a). The structural complexity that can define tropical forests (i.e., very tall trees, high number of canopy layers) is also a potential challenge for TreM identification, but current research on individual TreMs in these forests demonstrates that such surveys are possible. The research conducted in the temperate rainforest of North America (Michel and Winter, 2009), characterized by very tall trees, also underlines that tree height poses a challenge for TreM surveys but is still feasible. The continuous improvement of technologies such as LiDAR can also greatly facilitate the study of the characteristics of very tall trees (Disney et al., 2020). Regarding savannas, several research on TreMs and the related biodiversity have been carried out on isolated trees in agricultural landscapes in Europe (Parmain and Bouget, 2018; Froidevaux et al., 2022), highlighting that these indicators can also be relevant outside of closed-canopy forests.

Overall, the concept of TreMs is potentially applicable across all forest ecosystems, but some challenges related to these indicators may be exacerbated in certain contexts, in particular the tropical forests. The previously identified gap between the financial resources allocated to research in countries of the Global North compared with other can further reinforce these challenges. Thus, practical constraints seem to be the main limitation to the application or evaluation of the TreM concept in tropical forests and in savannas. The relative novelty and confidentiality of this indicator may also help explain its use only in a limited number of forest ecosystems. A wider dissemination of the TreM concept may facilitate the development of research projects exploring their ecological relevance in more meridional forests.

Conclusion and Perspectives

TreMs is still a recent yet rapidly expanding ecological concept that can serve as a useful biodiversity and naturalness indicator. However, we identified many gaps in current TreM research, both in terms of geographical extent (most of the existing research comes from Western Europe, representing a limited set of biomes, tree genera, and disturbance history) or in themes addressed (focus on the value of TreMs as biodiversity indicators, the impact of forest management on TreMs and the factors explaining TreM occurrence), supporting, respectively, our two assumptions. Extending the TreM concept to a larger geographical scale and a greater diversity of themes will therefore certainly be beneficial in strengthening the robustness and applicability of this indicator.

The homogenized TreM typology proposed by Larrieu et al. (2018b) can be seen as a major step toward a greater utilization of the TreM concept. Previous research often used “ad hoc” typologies, with specific TreM classes and size thresholds, thus limiting comparisons and the possibility of performing syntheses and meta-analyses without degrading the information. Larrieu et al. (2018b) typology is thus expected to serve as a basis for new TreM studies in Europe and beyond. This typology is however designed for temperate and Mediterranean forests, underscoring that research in new areas and biomes will be useful to test its relevance and robustness. The hierarchical structure of this typology is precisely designed to facilitate the inclusion of new TreMs, while avoiding the creation of new sub-typologies that would limit the replicability of studies. Accordingly, it provides a further step toward establishing a relevant typology for all forest ecosystems.

The need to evaluate the robustness of current TreM typologies and to extend their scope to new contexts also highlights the importance of international collaborations. Combining the experience gained from the study of TreMs with knowledge of the local characteristics of forests in different regions will certainly facilitate new collaborations and management strategies. Similarly, interdisciplinary research should be encouraged. Working with forest managers would also help define strategies to better integrate TreMs in forest management planning and daily operations in the field. In this context, a communication and training program for forest managers and practitioners would be essential to reduce the negative perception of some TreMs as “defects” to be removed. The efforts initiated by certain research projects to facilitate the integration of TreMs in routine forest management (Larrieu et al., 2019, 2021; Martin and Raymond, 2019; Reise et al., 2019) should be continued. Finally, the recent growing interest in “citizen” surveys, where data are spontaneously sampled by generally non-professional citizens, offers a good opportunity to complete our knowledge of distribution patterns of TreMs across both continents. Such inventories have the potential to quickly provide a significant amount of data on a large spatial scale. They require, however, sound communication and pedagogical work from the scientific community to ensure data quality. This citizen science approach would also raise public awareness about the importance of TreMs for forest biodiversity and more generally about the importance of natural forests, particularly old seral stages that harbor TreMs.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Data_Systematic_Review_Tree-Related_Microhabitats/17033435.

Author contributions

MM, YP, and LL conceived the ideas, designed methodology, and collected the data. MM performed the analyses and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MM, YP, LL, CK, PR, PD, and NF interpreted the results. YP, LL, CK, PR, PD, and NF contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Valentina Buttò for creating the tree illustration in Figure 1, as well as Celine Emberger and Rita Bütler for sharing the biodiversity illustrations in Figure 1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2022.818474/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aitchison J. Gilchrist A. Bawden D. (2000). Thesaurus Construction and Use: A Practical Manual, 4th Edn.London: Aslib.

2

Asbeck T. Basile M. Stitt J. Bauhus J. Storch I. Vierling K. T. (2020a). Tree-related microhabitats are similar in mountain forests of Europe and North America and their occurrence may be explained by tree functional groups. Trees34, 1453–1466. 10.1007/s00468-020-02017-3

3

Asbeck T. Großmann J. Paillet Y. Winiger N. Bauhus J. (2021a). The use of tree-related microhabitats as forest biodiversity indicators and to guide integrated forest management. Curr. For. Rep. 7, 59–68. 10.1007/s40725-020-00132-5

4

Asbeck T. Kozák D. Spînu A. P. Mikoláš M. Zemlerová V. Svoboda M. (2021b). Tree-related microhabitats follow similar patterns but are more diverse in primary compared to managed temperate mountain forests. Ecosystems25, 712–726. 10.1007/s10021-021-00681-1

5

Asbeck T. Messier C. Bauhus J. (2020b). Retention of tree-related microhabitats is more dependent on selection of habitat trees than their spatial distribution. Eur. J. For. Res.139, 1015–1028. 10.1007/s10342-020-01303-6

6

Asbeck T. Pyttel P. Frey J. Bauhus J. (2019). Predicting abundance and diversity of tree-related microhabitats in Central European montane forests from common forest attributes. For. Ecol. Manage.432, 400–408. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.043

7

Asbeck T. Sabatini F. Augustynczik A. L. D. Basile M. Helbach J. Jonker M. et al . (2021c). Biodiversity response to forest management intensity, carbon stocks and net primary production in temperate montane forests. Sci. Rep.11, 1625. 10.1038/s41598-020-80499-4

8

Atkinson L. Z. Cipriani A. (2018). How to carry out a literature search for a systematic review: a practical guide. BJPsych Adv.24, 74–82. 10.1192/bja.2017.3

9

Augustynczik A. L. D. Asbeck T. Basile M. Bauhus J. Storch I. Mikusiński G. et al . (2019). Diversification of forest management regimes secures tree microhabitats and bird abundance under climate change. Sci. Total Environ.650, 2717–2730. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.366

10

Augustynczik A. L. D. Asbeck T. Basile M. Jonker M. Knuff A. Yousefpour R. et al . (2020). Reconciling forest profitability and biodiversity conservation under disturbance risk: the role of forest management and salvage logging. Environ. Res. Lett.15, 0940a3. 10.1088/1748-9326/abad5a

11

Bagaram M. B. Giuliarelli D. Chirici G. Giannetti F. Barbati A. (2018). UAV remote sensing for biodiversity monitoring: are forest canopy gaps good covariates?Remote Sens.10, 1397. 10.3390/rs10091397

12

Basile M. Asbeck T. Jonker M. Knuff A. K. Bauhus J. Braunisch V. et al . (2020). What do tree-related microhabitats tell us about the abundance of forest-dwelling bats, birds, and insects?J. Environ. Manage.264, 110401. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110401

13

Bélisle A. C. Asselin H. (2020). A collaborative typology of boreal Indigenous landscapes. Can. J. For. Res.51, 1–35. 10.1139/cjfr-2020-0369

14

Bélisle A. C. Wapachee A. Asselin H. (2021). From landscape practices to ecosystem services: landscape valuation in Indigenous contexts. Ecol. Econ.179, 106858. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106858

15

Blicharska M. Angelstam P. Giessen L. Hilszczański J. Hermanowicz E. Holeksa J. et al . (2020). Between biodiversity conservation and sustainable forest management – a multidisciplinary assessment of the emblematic Białowieza Forest case. Biol. Conserv.248, 108614. 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108614

16

Blicharska M. Mikusiński G. (2014). Incorporating social and cultural significance of large old trees in conservation policy. Conserv. Biol.28, 1558–1567. 10.1111/cobi.12341

17

Bouget C. Larrieu L. Brin A. (2014a). Key features for saproxylic beetle diversity derived from rapid habitat assessment in temperate forests. Ecol. Indic.36, 656–664. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.09.031

18

Bouget C. Larrieu L. Nusillard B. Parmain G. (2013). In search of the best local habitat drivers for saproxylic beetle diversity in temperate deciduous forests. Biodivers. Conserv.22, 2111–2130. 10.1007/s10531-013-0531-3

19

Bouget C. Parmain G. Gilg O. Noblecourt T. Nusillard B. Paillet Y. et al . (2014b). Does a set-aside conservation strategy help the restoration of old-growth forest attributes and recolonization by saproxylic beetles?Anim. Conserv.17, 342–353. 10.1111/acv.12101

20

Burgar J. M. Craig M. D. Stokes V. L. (2015). The importance of mature forest as bat roosting habitat within a production landscape. For. Ecol. Manage.356, 112–123. 10.1016/j.foreco.2015.07.027

21

Burrascano S. de Andrade R. B. Paillet Y. Ódor P. Antonini G. Bouget C. et al . (2018). Congruence across taxa and spatial scales: Are we asking too much of species data?Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr.27, 980–990. 10.1111/geb.12766

22

Burrascano S. Keeton W. S. Sabatini F. M. Blasi C. (2013). Commonality and variability in the structural attributes of moist temperate old-growth forests: a global review. For. Ecol. Manage.291, 458–479. 10.1016/j.foreco.2012.11.020

23

Buse J. Schröder B. Assmann T. (2007). Modelling habitat and spatial distribution of an endangered longhorn beetle - a case study for saproxylic insect conservation. Biol. Conserv.137, 372–381. 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.02.025

24

Bütler R. Lachat T. Krumm F. Kraus D. Larrieu L. (2020). Guide de Poche des Dendromicrohabitats. Description et Seuil de Grandeur Pour leur Inventaire. Birmensdorf, Institut fédéral de recherches WSL.

25

Carvajal-Ocampo V. de los Á. Ángel-Vallejo M. C. Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P. D. A. Ospina-Bautista F. Estévez Varón J. V. (2019). A case of communal egg-laying of Gonatodes albogularis (Sauria, Sphaerodactylidae) in bromeliads (Poales, Bromeliaceae). Herpetozoa32, 45–49. 10.3897/herpetozoa.32.e35663

26

Cockle K. L. Martin K. Robledo G. (2012). Linking fungi, trees, and hole-using birds in a neotropical tree-cavity network: pathways of cavity production and implications for conservation. For. Ecol. Manage.264, 210–219. 10.1016/j.foreco.2011.10.015

27

Cosyns H. Joa B. Mikoleit R. Krumm F. Schuck A. Winkel G. et al . (2020). Resolving the trade-off between production and biodiversity conservation in integrated forest management: comparing tree selection practices of foresters and conservationists. Biodivers. Conserv.29, 3717–3737. 10.1007/s10531-020-02046-x

28

Cosyns H. Kraus D. Krumm F. Schulz T. Pyttel P. (2019). Reconciling the tradeoff between economic and ecological objectives in habitat-tree selection: a comparison between students, foresters, and forestry trainers. For. Sci.65, 223–234. 10.1093/forsci/fxy042

29

Courbaud B. Pupin C. Letort A. Cabanettes A. Larrieu L. (2017). Modelling the probability of microhabitat formation on trees using cross-sectional data. Methods Ecol. Evol.8, 1347–1359. 10.1111/2041-210X.12773

30

Cours J. Larrieu L. Lopez-Vaamonde C. Müller J. Parmain G. Thorn S. et al . (2021). Contrasting responses of habitat conditions and insect biodiversity to pest- or climate-induced dieback in coniferous mountain forests. For. Ecol. Manage.482, 118811. 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118811

31

Dajoz R. (2007). Les Insectes et la Forêt, 2nd Edn. Paris: Lavoisier-Tec & Doc.

32

DeGraaf R. M. Shigo A. L. (1985). General Technical Report NE- 101: Managing Cavity Trees for Wildlife in the Northeast.Broomall, PA: Northeastern Forest Experimental Station, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 10.2737/NE-GTR-101

33

Demant L. Bergmeier E. Walentowski H. Meyer P. (2020). Suitability of contract-based nature conservation in privately-owned forests in Germany. Nat. Conserv.42, 89–112. 10.3897/natureconservation.42.58173

34

Disney M. I. Burt A. Wilkes P. Armston J. Duncanson L. (2020). New 3D measurements of large redwood trees for biomass and structure. Sci. Rep. 10, 16721. 10.1038/s41598-020-73733-6

35

Donthu N. Kumar S. Mukherjee D. Pandey N. Lim W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res.133, 285–296. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

36

Drapeau P. Nappi A. Imbeau L. Saint-Germain M. (2009). Standing deadwood for keystone bird species in the eastern boreal forest: managing for snag dynamics. For. Chron.85, 227–234. 10.5558/tfc85227-2

37

Ellis E. C. (2011). Anthropogenic transformation of the terrestrial biosphere. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci.369, 1010–1035. 10.1098/rsta.2010.0331

38

Feldman M. J. Imbeau L. Marchand P. Mazerolle M. J. Darveau M. Fenton N. J. (2020). Trends and gaps in the use of citizen science derived data as input for species distribution models: a quantitative review. PLoS ONE16, e127415. 10.1101/2020.06.01.127415

39

Foo Y. Z. O'Dea R. E. Koricheva J. Nakagawa S. Lagisz M. (2021). A practical guide to question formation, systematic searching and study screening for literature reviews in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol.12, 1705–1720. 10.1111/2041-210X.13654

40

Forest Europe (2015). State of Europe's forests 2015, in Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe (Madrid: Forest Europe).

41

Franklin J. F. Lindenmayer D. Macmahon J. A. Mckee A. Perry D. A. Waide R. et al . (2000). Threads of continuity: ecosystem disturbance, recovery, and the theory of biological legacies. Conserv. Pract.1, 8–17. 10.1111/j.1526-4629.2000.tb00155.x

42

Frey J. Asbeck T. Bauhus J. (2020). Predicting tree-related microhabitats by multisensor close-range remote sensing structural parameters for the selection of retention elements. Remote Sens.12, 867. 10.3390/rs12050867

43

Fritz Ö. Heilmann-Clausen J. (2010). Rot holes create key microhabitats for epiphytic lichens and bryophytes on beech (Fagus sylvatica). Biol. Conserv.143, 1008–1016. 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.01.016

44

Froidevaux J. S. P. Laforge A. Larrieu L. Barbaro L. Park K. Fialas P. C. et al . (2022). Tree size, microhabitat diversity and landscape structure determine the value of isolated trees for bats in farmland. Biol. Conserv.267, 109476. 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109476

45

Gosselin F. Larrieu L. (2020). Developing and using statistical tools to estimate observer effect for ordered class data: the case of the IBP (index of biodiversity potential). Ecol. Indic.110, 105884. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105884

46

Gossner M. M. Gazzea E. Diedus V. Jonker M. Yaremchuk M. (2020). Using sentinel prey to assess predation pressure from terrestrial predators in water-filled tree holes. Eur. J. Entomol.117, 226–234. 10.14411/eje.2020.024

47

Goward T. Arsenault A. (2018). Calicioid diversity in humid inland British Columbia may increase into the 5th century after stand initiation. Lichenologist50, 555–569. 10.1017/S0024282918000324

48

Griffith D. M. Veech J. A. Marsh C. J. (2016). Cooccur: probabilistic species co-occurrence analysis in R. J. Stat. Softw.69, 1–17. 10.18637/jss.v069.c02

49

Großmann J. Pyttel P. Bauhus J. Lecigne B. Messier C. (2020). The benefits of tree wounds: microhabitat development in urban trees as affected by intensive tree maintenance. Urban For. Urban Green.55, 126817. 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126817

50

Großmann J. Schultze J. Bauhus J. Pyttel P. (2018). Predictors of microhabitat frequency and diversity in mixed mountain forests in South-Western Germany. Forests9, 1–22. 10.3390/f9030104

51

Haddad C. R. (2016). Diversity and ecology of spider assemblages associated with vachellia xanthophloea bark in a south african reserve (Arachnida: Araneae). Afr. Entomol.24, 321–333. 10.4001/003.024.0321

52

Herrault P. A. Larrieu L. Cordier S. Gimmi U. Lachat T. Ouin A. et al . (2016). Combined effects of area, connectivity, history and structural heterogeneity of woodlands on the species richness of hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae). Landsc. Ecol.31, 877–893. 10.1007/s10980-015-0304-3

53

Ibarra J. T. Novoa F. J. Jaillard H. Altamirano T. A. (2020). Large trees and decay: suppliers of a keystone resource for cavity-using wildlife in old-growth and secondary Andean temperate forests. Austral. Ecol.45, 1135–1144. 10.1111/aec.12943

54

Jahed R. R. Kavousi M. R. Farashiani M. E. (2020). A comparison of the formation rates and composition of tree-related microhabitats in beech-dominated primeval Carpathian and Hyrcanian forests. Forests11, 1–13. 10.3390/f11020144

55

Janssen P. Cateau E. Fuhr M. Nusillard B. Brustel H. Bouget C. (2016). Are biodiversity patterns of saproxylic beetles shaped by habitat limitation or dispersal limitation? A case study in unfragmented montane forests. Biodivers. Conserv.25, 1167–1185. 10.1007/s10531-016-1116-8

56

Jaroszewicz B. Cholewińska O. Gutowski J. M. Samojlik T. Zimny M. Latałowa M. (2019). Białowieza forest-a relic of the high naturalness of European forests. Forests10, 1–28. 10.3390/f10100849

57

Joa B. Paulus A. Mikoleit R. Winkel G. (2020). Decision making in tree selection – contemplating conflicting goals via marteloscope exercises. Rural Landsc.7, 1–14. 10.16993/rl.60

58

Johann F. Schaich H. (2016). Land ownership affects diversity and abundance of tree microhabitats in deciduous temperate forests. For. Ecol. Manage.380, 70–81. 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.08.037

59

Kameniar O. BalᎠM. Svitok M. Reif J. MikolᚠM. Pettit J. L. et al . (2021). Historical natural disturbances shape spruce primary forest structure and indirectly influence bird assemblage composition. For. Ecol. Manage.481, 118647. 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118647

60

Khanalizadeh A. Rad J. E. Lexer M. J. (2020). Assessing selected microhabitat types on living trees in oriental beech (Fagus orientalis L.) dominated forests in Iran. Ann. For. Sci.77, 91. 10.1007/s13595-020-00996-4

61

Kirsch J. Sermon J. Jonker M. Asbeck T. Gossner M. M. Petermann J. S. et al . (2021). The use of water-filled tree holes by vertebrates in temperate forests. Wildlife Biol. 2021, wlb.00786. 10.2981/wlb.00786

62

Kitching R. L. (1971). An ecological study of water-filled tree-holes and their position in the woodland ecosystem. J. Anim. Ecol.40, 281. 10.2307/3247

63

Knuff A. K. Staab M. Frey J. Dormann C. F. Asbeck T. Klein A. M. (2020). Insect abundance in managed forests benefits from multi-layered vegetation. Basic Appl. Ecol.48, 124–135. 10.1016/j.baae.2020.09.002

64

Kõrkjas M. Remm L. Lõhmus A. (2021a). Development rates and persistence of the microhabitats initiated by disease and injuries in live trees: a review. For. Ecol. Manage.482, 118833. 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118833

65

Kõrkjas M. Remm L. Lõhmus A. (2021b). Tree-related microhabitats on live Populus tremula and Picea abies in relation to tree age, diameter, and stand factors in Estonia. Eur. J. For. Res.140, 1227–1241. 10.1007/s10342-021-01396-7

66

Kozák D. Mikoláš M. Svitok M. Bače R. Paillet Y. Larrieu L. et al . (2018). Profile of tree-related microhabitats in European primary beech-dominated forests. For. Ecol. Manage.429, 363–374. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.07.021

67

Kozák D. Svitok M. Wiezik M. Mikola M. Matula R. Thorn S. et al . (2021). Historical disturbances determine current taxonomic, functional and phylogenetic diversity of saproxylic beetle communities in temperate primary forests. Ecosystems24, 37–55. 10.1007/s10021-020-00502-x

68

Kraus D. Bütler R. Krumm F. Lachat T. (2016). Catalogue of Tree Microhabitats—Reference Field List. Integrate+ Technical Paper. Freiburg: European Forest Institute.

69

Kuuluvainen T. (2009). Forest management and biodiversity conservation based on natural ecosystem dynamics in Northern Europe : the complexity challenge. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ.38, 309–315. 10.1579/08-A-490.1

70

Langridge J. Pisanu B. Laguet S. Archaux F. Tillon L. (2019). The role of complex vegetation structures in determining hawking bat activity in temperate forests. For. Ecol. Manage.448, 559–571. 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.04.053

71

Larrieu L. Brustel H. Cabanettes A. Corriol G. Delarue A. Harel M. et al . (2009). Impact de l'anthropisation ancienne sur la biodiversité d'un habitat de hêtraie-sapinière montagnarde. Rev. For. Franç.61, 351–368. 10.4267/2042/30546

72

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. (2012). Species, live status, and diameter are important tree features for diversity and abundance of tree microhabitats in subnatural montane beech-fir forests. Can. J. For. Res. Can. Rech. For.42, 1433–1445. 10.1139/x2012-077

73

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Brin A. Bouget C. Deconchat M. (2014a). Tree microhabitats at the stand scale in montane beech-fir forests: Practical information for taxa conservation in forestry. Eur. J. For. Res.133, 355–367. 10.1007/s10342-013-0767-1

74

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Courbaud B. Goulard M. Heintz W. Schuck A. et al . (2021). Co-occurrence patterns of tree-related microhabitats : a method to simplify routine monitoring. Ecol. Indic.127, 107757. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107757

75

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Delarue A. (2012). Impact of silviculture on dead wood and on the distribution and frequency of tree microhabitats in montane beech-fir forests of the Pyrenees. Eur. J. For. Res.131, 773–786. 10.1007/s10342-011-0551-z

76

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Gonin P. Lachat T. Paillet Y. Winter S. et al . (2014b). Deadwood and tree microhabitat dynamics in unharvested temperate mountain mixed forests: a life-cycle approach to biodiversity monitoring. For. Ecol. Manage.334, 163–173. 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.09.007

77

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Gouix N. Burnel L. Bouget C. Deconchat M. (2017). Development over time of the tree-related microhabitat profile: the case of lowland beech–oak coppice-with-standards set-aside stands in France. Eur. J. For. Res.136, 37–49. 10.1007/s10342-016-1006-3

78

Larrieu L. Cabanettes A. Sarthou J. P. (2015). Hoverfly (Diptera: Syrphidae) richness and abundance vary with forest stand heterogeneity: preliminary evidence from a montane beech fir forest. Eur. J. Entomol.112, 755–769. 10.14411/eje.2015.083

79

Larrieu L. Gonin P. (2008). L'lndice de biodiversité potentielle (IBP): une méthode simple et rapide pour évaluer la biodiversité potentielle des peuplements forestiers. Rev. For. Franç.60, 727–748. 10.4267/2042/28373

80

Larrieu L. Gosselin F. Archaux F. Chevalier R. Corriol G. Dauffy-Richard E. et al . (2018a). Cost-efficiency of cross-taxon surrogates in temperate forests. Ecol. Indic.87, 56–65. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.12.044

81

Larrieu L. Gosselin F. Archaux F. Chevalier R. Corriol G. Dauffy-Richard E. et al . (2019). Assessing the potential of routine stand variables from multi-taxon data as habitat surrogates in European temperate forests. Ecol. Indic.104, 116–126. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.04.085

82

Larrieu L. Paillet Y. Winter S. Bütler R. Kraus D. Krumm F. et al . (2018b). Tree related microhabitats in temperate and Mediterranean European forests: a hierarchical typology for inventory standardization. Ecol. Indic.84, 194–207. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.08.051

83

Lassauce A. Larrieu L. Paillet Y. Lieutier F. Bouget C. (2013). The effects of forest age on saproxylic beetle biodiversity: implications of shortened and extended rotation lengths in a French oak high forest. Insect Conserv. Divers.6, 396–410. 10.1111/j.1752-4598.2012.00214.x

84

Leidinger J. Weisser W. W. Kienlein S. Blaschke M. Jung K. Kozak J. et al . (2020). Formerly managed forest reserves complement integrative management for biodiversity conservation in temperate European forests. Biol. Conserv.242, 108437. 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108437

85

Lelli C. Bruun H. H. Chiarucci A. Donati D. Frascaroli F. Fritz Ö. et al . (2019). Biodiversity response to forest structure and management: comparing species richness, conservation relevant species and functional diversity as metrics in forest conservation. For. Ecol. Manage.432, 707–717. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.057

86

Lilja S. Kuuluvainen T. (2005). Structure of old Pinus sylvestris dominated forest stands along a geographic and human impact gradient in mid-boreal fennoscandia. Silva Fenn.39, 407–428. 10.14214/sf.377

87

Lindenmayer D. B. Cunningham R. B. Donnelly C. F. Franklin J. F. (2000). Structural features of old-growth Australian montane ash forests. For. Ecol. Manage.134, 189–204. 10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00257-1

88

Lombardi F. Di Lella S. Altieri V. Di Benedetto S. Giancola C. Lasserre B. et al . (2018). Early responses of biodiversity indicators to various thinning treatments in mountain beech forests. IForest11, 609–618. 10.3832/ifor2733-011

89

Madera P. Slach T. Úradnícek L. Lacina J. Cernušáková L. Friedl M. et al . (2017). Tree shape and form in ancient coppice woodlands. J. Landsc. Ecol.10, 49–62. 10.1515/jlecol-2017-0004

90

Martin L. J. Blossey B. Ellis E. (2012). Mapping where ecologists work: Biases in the global distribution of terrestrial ecological observations. Front. Ecol. Environ.10, 195–201. 10.1890/110154

91

Martin M. Fenton N. J. Morin H. (2021a). Tree-related microhabitats and deadwood dynamics form a diverse and constantly changing mosaic of habitats in boreal old-growth forests. Ecol. Indic.128, 107813. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107813

92

Martin M. Raymond P. (2019). Assessing tree-related microhabitat retention according to a harvest gradient using tree-defect surveys as proxies in eastern canadian mixedwood forests. For. Chron.95, 157–170. 10.5558/tfc2019-025

93

Martin M. Raymond P. Boucher Y. (2021b). Influence of individual tree characteristics, spatial structure and logging history on tree-related microhabitat occurrence in North American hardwood forests. For. Ecosyst.8, 1–16. 10.1186/s40663-021-00305-z

94

Marziliano P. A. Antonucci S. Tognetti R. Marchetti M. Chirici G. Corona P. et al . (2021). Factors affecting the quantity and type of tree-related microhabitats in mediterranean mountain forests of high nature value. IForest14, 250–259. 10.3832/ifor3568-014

95

McGregor D. (2002). Indigenous knowledge in sustainable forest management: community-based approaches achieve greater success. For. Chron.78, 833–836. 10.5558/tfc78833-6

96

Menkis A. Redr D. Bengtsson V. Hedin J. Niklasson M. Nordén B. et al . (2020). Endophytes dominate fungal communities in six-year-old veteranisation wounds in living oak trunks. Fungal Ecol.2020, 101020. 10.1016/j.funeco.2020.101020

97

Messier C. Puettmann K. Chazdon R. Andersson K. P. Angers V. A. Brotons L. et al . (2015). From management to stewardship: viewing forests as complex adaptive systems in an uncertain world. Conserv. Lett.8, 368–377. 10.1111/conl.12156

98

Michel A. K. Winter S. (2009). Tree microhabitat structures as indicators of biodiversity in Douglas-fir forests of different stand ages and management histories in the Pacific Northwest, U.S.A. For. Ecol. Manage.257, 1453–1464. 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.11.027

99

Michel A. K. Winter S. Linde A. (2011). The effect of tree dimension on the diversity of bark microhabitat structures and bark use in Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii). Can. J. For. Res.41, 300–308. 10.1139/X10-207

100

Müller J. Jarzabek-Müller A. Bussler H. Gossner M. M. (2014). Hollow beech trees identified as keystone structures for saproxylic beetles by analyses of functional and phylogenetic diversity. Anim. Conserv.17, 154–162. 10.1111/acv.12075

101

Newbold T. (2010). Applications and limitations of museum data for conservation and ecology, with particular attention to species distribution models. Prog. Phys. Geogr.34, 3–22. 10.1177/0309133309355630

102

Oksanen J. Blanchet G. Friendly M. Kindt R. Legendre P. MCGlinn D. et al . (2018). vegan: Community Ecology Package. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan

103

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (2004). Ontario Tree Marking Guide, Version 1.1.Toronto, ON: Ontario Ministry of Natural Ressources. Quenn's Printer for Ontario.

104

Ouin A. Cabanettes A. Andrieu E. Deconchat M. Roume A. Vigan M. et al . (2015). Comparison of tree microhabitat abundance and diversity in the edges and interior of small temperate woodlands. For. Ecol. Manage.340, 31–39. 10.1016/j.foreco.2014.12.009

105

Ozdemir I. Mert A. Ozkan U. Y. Aksan S. Unal Y. (2018). Predicting bird species richness and micro-habitat diversity using satellite data. For. Ecol. Manage.424, 483–493. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.05.030

106

Packalen P. Vauhkonen J. Kallio E. Peuhkurinen J. Pitkänen J. Pippuri I. et al . (2013). Predicting the spatial pattern of trees by airborne laser scanning. Int. J. Remote Sens.34, 5154–5165. 10.1080/01431161.2013.787501

107

Paillet Y. Archaux F. Boulanger V. Debaive N. Fuhr M. Gilg O. et al . (2017). Snags and large trees drive higher tree microhabitat densities in strict forest reserves. For. Ecol. Manage.389, 176–186. 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.12.014

108

Paillet Y. Archaux F. du Puy S. Bouget C. Boulanger V. Debaive N. et al . (2018). The indicator side of tree microhabitats: a multi-taxon approach based on bats, birds and saproxylic beetles. J. Appl. Ecol.55, 2147–2159. 10.1111/1365-2664.13181

109

Paillet Y. Coutadeur P. Vuidot A. Archaux F. Gosselin F. (2015). Strong observer effect on tree microhabitats inventories: a case study in a French lowland forest. Ecol. Indic.49, 14–23. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2014.08.023

110

Paillet Y. Debaive N. Archaux F. Cateau E. Gilg O. Guilbert E. (2019). Nothing else matters ? Tree diameter and living status have more effects than biogeoclimatic context on microhabitat number and occurrence : an analysis in French forest reserves. PLoS ONE14, e0216500. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216500

111

Parisi F. Di Febbraro M. Lombardi F. Biscaccianti A. B. Campanaro A. Tognetti R. et al . (2019). Relationships between stand structural attributes and saproxylic beetle abundance in a Mediterranean broadleaved mixed forest. For. Ecol. Manage.432, 957–966. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.10.040

112

Parisi F. Frate L. Lombardi F. Tognetti R. Campanaro A. Biscaccianti A. B. et al . (2020a). Diversity patterns of coleoptera and saproxylic communities in unmanaged forests of Mediterranean mountains. Ecol. Indic.110, 105873. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105873

113

Parisi F. Innangi M. Tognetti R. Lombardi F. Chirici G. Marchetti M. (2021). Forest stand structure and coarse woody debris determine the biodiversity of beetle communities in Mediterranean mountain beech forests. Glob. Ecol. Conserv.28, e01637. 10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01637

114

Parisi F. Lombardi F. Marziliano P. A. Russo D. De Cristofaro A. Marchetti M. et al . (2020b). Diversity of saproxylic beetle communities in chestnut agroforestry systems. IForest13, 456–465. 10.3832/ifor3478-013

115

Parisi F. Lombardi F. Sciarretta A. Tognetti R. Campanaro A. Marchetti M. et al . (2016). Spatial patterns of saproxylic beetles in a relic silver fir forest (Central Italy), relationships with forest structure and biodiversity indicators. For. Ecol. Manage.381, 217–234. 10.1016/j.foreco.2016.09.041

116