Abstract

Accurate estimation of gross primary production (GPP) and above-ground biomass (AGB) is fundamental to assessing the carbon sequestration potential of artificial mangrove wetlands. However, pronounced spatiotemporal heterogeneity in stand structure, particularly in restored mangrove forests with diverse age compositions, introduces substantial uncertainty in GPP and AGB quantification. This study presents an innovative framework that explicitly incorporates stand age into the light use efficiency (LUE) model as a physiological constraint, thereby enhancing the accuracy of GPP and AGB estimations. Stand age was mapped using Landsat-7 and sentinel-2 time-series imagery and a random forest classification approach on the Google Earth Engine platform, providing high spatial resolution age distributions. Age-dependent productivity constraints, derived from net primary production–age relationships observed in evergreen broadleaf ecosystems, were incorporated into the LUE model to refine photosynthetic efficiency estimations. Application of this framework to mangrove plantations in the Luoyangjiang Estuary (2000–2022) yielded high accuracy in GPP (RMSE = 9.66 g d−1, R2 = 0.95) and AGB (RMSE = 1,051 g·m−2, R2 = 0.63) estimations. The results captured exponential AGB growth with stand development, and spatial analysis demonstrated a strong correspondence between biomass distribution and stand age, with mature stands (≥20 years) contributing disproportionately to carbon accumulation. This stand age–integrated approach delivers fine spatial and temporal resolution, offering a practical and transferable tool for monitoring carbon dynamics and informing adaptive management strategies in restored coastal wetlands, thereby supporting the long-term assessment of blue carbon projects.

1 Introduction

As a vital component of blue carbon ecosystems, mangroves have attracted global attention for their role as a nature-based solution (NbS) in addressing climate change and enhancing coastal resilience (Lovelock et al., 2024). Over the past decades, mangroves worldwide have undergone a dynamic transition from widespread degradation to active restoration (Bourgeois et al., 2024). Driven by both anthropogenic planting and natural expansion, the total mangrove area has been steadily increasing (Chen et al., 2024). However, this recovery has also resulted in mangrove landscapes with highly heterogeneous stand-age structures (Song et al., 2023; Sunil Kumar and Kandasamy, 2019). Systematically evaluating the blue carbon benefits of planted mangroves is essential for identifying priority areas for future restoration and maximizing blue carbon potential in recoverable zones (Gu et al., 2022). Therefore, accurately quantifying the dynamics of aboveground biomass (AGB) is essential to evaluate these carbon benefits and requires reliable estimation methods (Sun et al., 2024; Zheng and Takeuchi, 2022).

Several approaches have been developed to estimate mangrove AGB, each with distinct strengths and limitations (Tian et al., 2017). Currently, mangrove AGB is estimated using field measurements, model-based approaches, or remote sensing techniques (Hu et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2023). Field measurements are often considered the most accurate (Chave et al., 2015). This method relies on species-specific allometric equations derived from parameters such as diameter at breast height (DBH) (Chave et al., 2015). However, field surveys are labor-intensive, costly, and spatially limited (Chou et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2021). Model-based methods establish empirical or process-based relationships between climatic drivers and biomass (Hu et al., 2020). These methods typically represent potential rather than realized distributions (Gouvêa et al., 2022; Hutchison et al., 2013). Remote sensing includes optical vegetation indices, synthetic aperture radar, and LiDAR (Lagomasino et al., 2016; Hamdan et al., 2014). It allows large-scale monitoring and improved spatial resolution (Tahmouresi et al., 2024). it is often constrained to single-time snapshots, with repeated acquisitions hindered by data availability, cost, and temporal inconsistency (Ju et al., 2025). Critically, these approaches struggle to link short-term photosynthetic activity with long-term biomass accumulation (Malhi et al., 2015; Ju et al., 2025; Pham and Brabyn, 2017; Zhao et al., 2023). Given the limitations of conventional methods, light use efficiency (LUE)-based modeling provides a robust framework to estimate gross primary productivity (GPP) and AGB by linking photosynthetic carbon uptake directly with biomass accumulation (Huang et al., 2024; Wu L. et al., 2023). GPP is defined as the total amount of carbon dioxide fixed by plants over a given period (e.g., hour, day, or year) through photosynthesis. Net primary production (NPP) is obtained by subtracting autotrophic respiration (Ra) from GPP. Therefore, GPP and NPP reflect the functional performance of mangrove ecosystems and their carbon sequestration rates (Erofeeva, 2024). LUE model treats GPP as the product of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (APAR) and the actual LUE, defining LUE as the efficiency with which photosystems use absorbed light energy to fix carbon (Pei et al., 2022). Environmental factors affecting photosynthetic efficiency include moisture, radiation, temperature, carbon dioxide concentration, scattered light, salinity and others (Barr et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2023; Pei et al., 2022).

Several approaches have been developed to estimate GPP and NPP, including field-based measurements, process-based models, and statistical modeling frameworks (Liao et al., 2023). Field measurements, such as eddy covariance and gas exchange techniques, provide direct and accurate observations (Gu et al., 2022), although their limited spatial representativeness restricts large-scale and long-term applications. Process-based ecological models simulate various biophysical and biochemical processes, including photosynthesis, transpiration, and soil carbon dynamics (Liao et al., 2023). Representative examples include the 3-PG, Forest-BGC, TEM, InTEC, and Mango-GPP models (Restrepo et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2023). Despite their mechanistic strength, these models require extensive parameterization, long-term ecosystem monitoring, and often exhibit poor transferability across regions (Pei et al., 2022). Statistical models estimate productivity through empirical relationships linking GPP or biomass with climatic and environmental variables using regression or machine-learning algorithms (Virkkala et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2020). While computationally efficient, these models describe correlations rather than causal mechanisms, and thus oversimplify the complexity of ecosystem functioning (Wang et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2025). By contrast, the Light Use Efficiency (LUE) model has been widely adopted for regional and global GPP estimation because it combines a simple structure, low data requirements, and strong ecological foundation (Huang et al., 2024; Sun et al., 2024). Integrating remotely sensed radiation with climatic and environmental constraints, the LUE framework is well suited for long-term, large-scale assessments and effectively captures spatial and temporal heterogeneity (Cheng et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2015).

The LUE model, originally developed by (Monteith 1972), posits a linear relationship between GPP and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR). Based on this framework, enhanced LUE models have been developed specifically for mangrove ecosystems (Xie et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2015; Zheng et al., 2018). Among these refinements is the integration of critical environmental drivers, such as water availability, air and sea surface temperature, and salinity, in addition to key photosynthetic processes (Barr et al., 2013; Zheng and Takeuchi, 2022). Despite these advancements, most LUE applications neglect variations in stand age, which strongly influence mangrove productivity and carbon accumulation. This oversight introduces considerable uncertainty into LUE-based GPP estimates. In reality, stand age directly governs mangrove primary productivity and carbon sequestration potential (Carnell et al., 2022). Numerous studies have documented pronounced differences in photosynthetic capacity, carbon accumulation rates, and biomass structure across different growth stages (Shang et al., 2023; Wang S. et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2011). These findings highlight that light use efficiency is not static but varies significantly with stand development (Li et al., 2024; Richard et al., 2020). Therefore, accounting for the dynamic influence of stand age is crucial for enhancing the accuracy of mangrove GPP and AGB estimations.

Accurate biomass monitoring requires models that capture both spatial and temporal dynamics while reflecting ecological responses to natural and anthropogenic disturbances (Eisfelder et al., 2017; Kennedy et al., 2018). Yet, the insufficient integration of stand-age effects into current modeling frameworks remains a major barrier to understanding growth trajectories and carbon sequestration in mangroves. By explicitly incorporating stand age into the LUE framework, it becomes possible to bridge the gap between photosynthetic activity and long-term biomass accumulation, thereby reducing uncertainty in GPP and AGB estimates. This study addresses this gap by developing a novel LUE-based approach that integrates stand age, offering a more accurate and ecologically grounded representation of mangrove carbon dynamics.

This study presents a novel stand age-informed LUE model designed to enhance the estimation of GPP and AGB in restored mangrove ecosystems. Leveraging multi-temporal satellite imagery, extensive field surveys, and high-resolution GEDI-derived canopy metrics, the model captures mangrove carbon dynamics along the Luoyangjiang Estuary from 2000 to 2022. The study period was set from 2000 to 2022 because 2000 marks the beginning of mangrove planting in the study area, and 2022 corresponds to the most recent year when GEDI data were available for the region. This 2000–2022 interval represents the most complete and continuous period for multi-source datasets, ensuring reliable temporal coverage for the analysis. GEDI delivers global full-waveform LiDAR observations of vegetation, from which canopy height, vertical structure, and detailed vegetation profiles can be derived (Guo et al., 2023). Canopy height serves as a key structural indicator strongly correlated with aboveground biomass, assessing the potential of GEDI-derived canopy height as independent validation data is critical (Lagomasino et al., 2016). Such evaluation also supports the broader transferability and global application of the model. By explicitly incorporating stand age as a key ecological determinant of productivity, this approach reveals age-dependent patterns of carbon accumulation and significantly improves biomass estimation accuracy. The model is rigorously validated using in-situ measurements and other remote sensing products, demonstrating high reliability. Our framework offers a robust tool for supporting blue carbon accounting and guiding adaptive mangrove restoration strategies, providing both scientific and practical insights for local governance and coastal ecosystem management.

2 Materials and methods

Research workflow

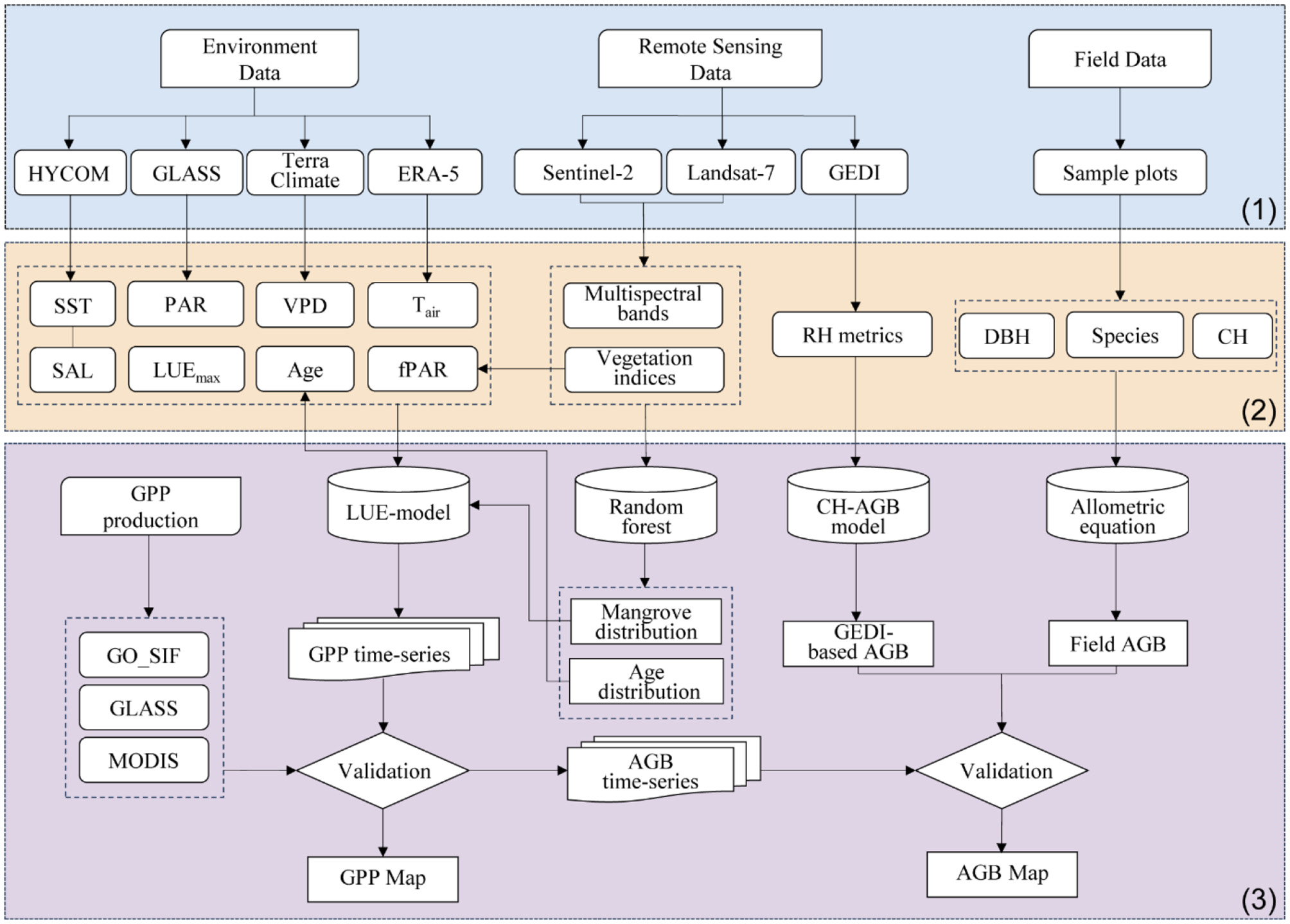

Figure 1 outlines the workflow for estimating GPP using an improved LUE model and deriving AGB) from GPP time-series. Section 1 details input data sources: multispectral imagery from Landsat-7 and Sentinel-2 used to calculate vegetation indices for land cover classification and fPAR estimation. Section 2 describes preprocessing: multi-source data were converted, clipped to the study area's spatiotemporal scope, and integrated into the LUE model. A RF classifier in GEE generated historical mangrove distribution maps, which informed forest age derivation—a novel factor added to the LUE model. Section 3 covers validation: GPP outputs (2000–2022, 8-day intervals) were cross-validated against MODIS, GLASS, and GOSIF products. AGB, derived from GPP time-series, was validated using GEDI satellite data and field measurements.

Figure 1

Study flowchart.

Study area

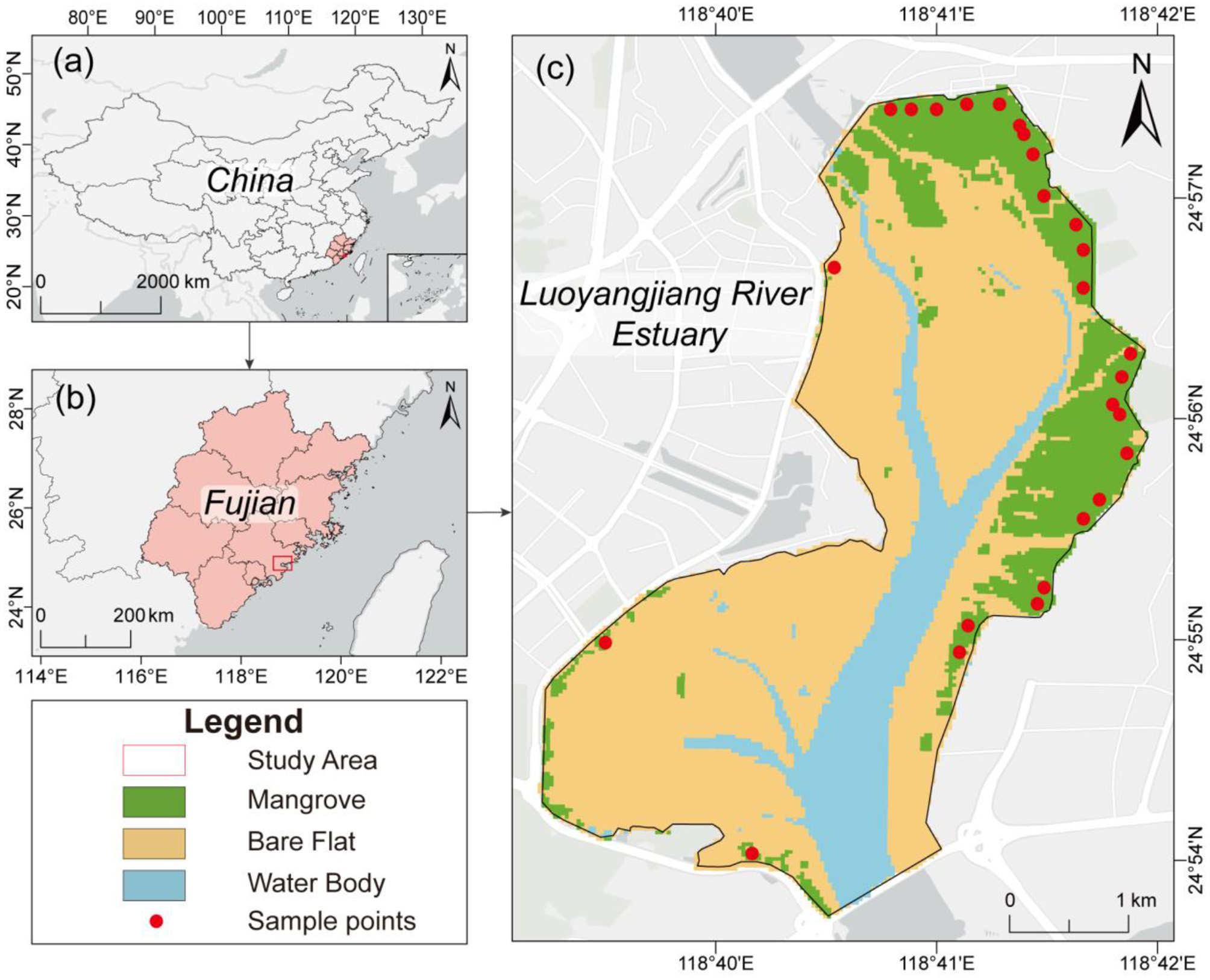

The Luoyangjiang River Estuary (24°53′-24°58′N, 118°39′-118°42′E) is located in Quanzhou Bay, Fujian Province, southeastern China (Figure 2). The region has a southern subtropical monsoonal maritime climate with a mean annual temperature of approximately 20 °C (Lin et al., 2025). The wetland is influenced by a regular semi-diurnal tidal regime, with an average high tide of 4.83 m, low tide of 0.31 m, and a mean tidal range of 4.52 m (Lu et al., 2018). These hydrological conditions shape the physiological responses and growth dynamics of mangroves. Historically, large areas of natural mangroves in the estuary were degraded due to aquaculture expansion and coastal development. Extensive ecological restoration began in the early 2000s, making the site one of the key mangrove restoration regions along the southeast coast of China. As a result, the current mangrove landscape consists of artificially planted and naturally regenerated stands, primarily dominated by Aegiceras corniculatum and Kandelia obovata (Chen et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2023). With more than two decades of restoration activities, the estuary now exhibits a heterogeneous spatial pattern of stand ages, ranging from young regenerating patches to mature stands. This distinct age gradient provides an ideal natural laboratory for evaluating age-adaptive productivity modeling frameworks such as the LUE model applied in this study. The combination of strong environmental gradients, prolonged restoration history, and diverse stand development stages makes the Luoyangjiang Estuary a representative and suitable site for examining how mangrove age structure influences carbon assimilation and biomass accumulation.

Figure 2

The location of the study area. (a) China, (b) Fujian Province, and (c) the Luoyangjiang River Estuary.

Data source

This study integrated three primary data sources to support the modeling and validation of mangrove gross primary productivity (GPP) and aboveground biomass (AGB): (1) remote sensing imagery, (2) environmental variables, (3) GEDI canopy height data and (4) field observations.

-

(1) Multispectral imagery from Landsat-7 (30 m resolution, 2000–2015) and Sentinel-2 (10 m resolution, 2016–2022) was used to delineate mangrove distribution across the study area. Image processing and classification covering the period 2000–2022 were conducted on the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. All remote sensing datasets used in this study were resampled to a uniform spatial resolution of 30 m. To ensure consistency and enable model integration, all variables were further harmonized to a common spatial and temporal scale.

-

(2) Environmental variables were key inputs to the light use efficiency (LUE)-based GPP model. Five variables were selected based on their relevance to mangrove photosynthesis in coastal ecosystems: photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), air temperature (Tair), vapor pressure deficit (VPD), sea surface temperature (SST), and salinity (SAL) (Abatzoglou et al., 2018; Chassignet et al., 2007; Liang et al., 2021; Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S), 2025). These datasets were sourced from gridded satellite products or reanalysis archives with continuous coverage from 2000 to 2022. Where temporal gaps existed, linear interpolation was applied to ensure data continuity. For SST and SAL, values were extracted from neighboring ocean pixels when spatial alignment with mangrove grids was not exact. All variables were harmonized to a common spatial and temporal resolution to enable model integration. Detailed data sources and parameter descriptions are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

-

(3) The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) mission is a spaceborne full-waveform LiDAR system launched by NASA in 2018 aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Its primary objective is to quantify the three-dimensional structure of forests worldwide, including tree height, canopy height, canopy cover, and vegetation vertical profiles. GEDI operates by emitting laser pulses and retrieving waveform returns over a circular footprint of approximately 25 m in diameter, enabling direct measurement of canopy height, vertical structure, and underlying terrain. This capability effectively addresses the limitations of traditional optical remote sensing, which lacks sensitivity to three-dimensional forest structure.

-

(4) In this study, we used the GEDI Level 2A canopy height product released in 2022. Based on the mangrove extent map, we extracted valid GEDI footprints located within mangrove-covered areas. After rigorous filtering to remove outliers and noise, we obtained representative canopy height metrics for mangrove forests across different stand-age classes (Dubayah et al., 2021). The GEDI LiDAR footprint data were spatially matched to the standardized grid system, and each valid footprint was assigned to its corresponding pixel for subsequent analysis.

-

Field surveys were conducted in 2022 to provide independent validation of model outputs. A total of 25 plots (30 m × 30 m) were established across representative mangrove zones. Within each plot, all individual trees were recorded for species identity, diameter at breast height (DBH), canopy height (CH), and stem density. These data supported species-specific allometric estimates of AGB at the tree level, which were aggregated to the plot scale for model evaluation. Based on planting year, planting density, tidal elevation, and dominant species, the artificial mangrove belt in the Luoyangjiang Estuary was divided into eight subregions from south to north. Field plots were established to ensure that each subregion was represented, thereby maximizing sampling representativeness across spatial and ecological gradients. The spatial distribution of field plots is shown in Figure 2.

Modeling spatially explicit mangrove aboveground carbon stock

Spatiotemporal mapping of mangrove age dynamics

Landsat-7 and Sentinle-2 satellite imagery from 2000 to 2022 was used to derive annual land cover maps of the Luoyangjiang wetland. For each year, all available images were first processed using cloud-masking techniques, followed by median compositing to produce a single high-quality, cloud-free composite representative of annual conditions. A random forest classifier, informed by vegetation indices and spectral separability among land cover types, was then applied to categorize the imagery into three classes: mangroves, mudflats (including both unvegetated tidal flats and saltmarshes), and open water. MTWM-TP was integrated into the Random Forest classifier to reduce the influence of tidal fluctuations on classification accuracy (Zhang et al., 2022). This classification strategy was specifically designed to highlight mangrove areas for focused analysis of GPP and AGB.

Based on the annual land cover classifications, a 30 m resolution mangrove stand age map was developed for the period 2000–2022. As large-scale mangrove planting began in 2000, this year was used as the reference point for stand age estimation. Mangrove patches were tracked through time to assign stand age, which was further stratified into 5-year intervals to produce a long-term, spatially explicit age dataset. Additional validation was conducted using field measurements and empirical age–AGB relationships for mangrove.

Modeling mangrove GPP with age-dependent LUE

To improve the accuracy of mangrove ecosystem productivity estimation, this study incorporates stand age as a key biological constraint within the light use efficiency (LUE) framework. As mangrove forests develop, canopy photosynthetic capacity typically increases during early growth, peaks at intermediate stages, and declines thereafter due to structural and physiological limitations such as canopy closure and nutrient depletion (Zheng and Takeuchi, 2022). To capture this non-linear age-dependent response, we introduced an age-based modifier into the LUE formulation, allowing photosynthetic efficiency to vary with stand developmental stage. The revised model builds upon the Mangrove Vegetation Photosynthesis Model (MVP-LUE), which traditionally accounts for environmental limiting factors including air temperature (Tair), salinity (SAL), photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), vapor pressure deficit (VPD), and sea surface temperature (SST) (Barr et al., 2013). Further details are provided in Supplementary Table S2. By explicitly integrating stand age alongside these drivers, the model offers a more physiologically realistic simulation of spatiotemporal variations in mangrove productivity. The age-adjusted LUE is expressed as:

where LUEmax represents the maximum light use efficiency under ideal conditions. f (Age) is an age-dependent modifier introduced to account for the variation in canopy photosynthetic capacity over time. The term represents the combined influence of traditional environmental limiting factors, where xi ∈ {Tair, SAL, PAR, VPD, SST}, corresponding to air temperature, salinity, photosynthetically active radiation, vapor pressure deficit, and sea surface temperature.

The stand age is a critical biological factor influencing ecosystem productivity. In many evergreen broad-leaved and mixed forests, studies have shown that stand-level NPP (or carbon accumulation rate) typically increases during early growth, peaks at intermediate ages, and then declines or stabilizes as stands mature due to canopy closure, increased maintenance respiration, nutrient limitation, and other age-related constraints (He et al., 2012; Shang et al., 2023; Wang B. et al., 2018). Mangroves share key structural and functional characteristics with broad-leaved evergreen forests and recent mangrove chronosequence studies document similar NPP-AGE pattern (Bourgeois et al., 2024; Panda et al., 2025; Walcker et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2024). To represent this process in mangrove ecosystems, we adopt a generalized, normalized growth function originally developed for evergreen broad-leaved forests in China (Wang et al., 2011), which aligns with the characteristics of mangroves.

The age-related adjustment to LUE is expressed as:

where f (AGE) is the normalized efficiency factor associated with stand age, and NPPmax is the maximum net primary productivity.

The growth function G(Age) is defined as:

where Age is the forest stand age (years), a = 365.6 is a scaling constant representing potential productivity, b = 4.12, c = 91.57, and d = 0.30 are empirically derived shape parameters based on flux observations for evergreen broad-leaved forests.

The air temperature can inhibit enzymatic activity, thereby limiting the photosynthetic capacity of mangroves (Barr et al., 2013). The regulation of LUE by sea surface temperature (SST) and air temperature (Tair) can be expressed as (Barr et al., 2013; Raich et al., 1991):

where Tair is the air temperature, Topt, Tmin, Tmax, are the optimum, minimum, and maximum temperatures, respectively for mangrove photosynthesis activity.

Water stress on mangrove photosynthesis can be represented by atmospheric water stress, defined as vapor pressure deficit (VPD), which can be calculated by (Running and Zhao 2021):

where VPDmin and VPDmax are maximum and minimum daytime VPD. If the value of VPD is less than VPDmin, water stress does not inhibit mangrove photosynthesis, such that f (VPD) = 1. If VPD value is greater than VPDmax, mangrove photosynthesis ceases, meaning f (VPD) = 0.

The constraint of PAR and salinity on mangrove GPP can be expressed using same form linear equation (Barr et al., 2013):

where msal and mpar are the rate of decreasing f (SAL) to increasing SAL and rate of decreasing f (PAR) to increasing PAR.

Gross primary productivity (GPP) represents the total carbon fixed through photosynthesis and is commonly estimated using the light use efficiency (LUE) framework. In this approach, GPP is calculated as the product of incident photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), the fraction of PAR absorbed by vegetation (fPAR), and the efficiency of light conversion (LUE):

where fPAR was derived from the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), which has been shown to perform best for forest ecosystems (Zheng et al., 2018).

Aboveground biomass accumulation from net primary productivity

The portion of carbon not lost to autotrophic respiration is allocated to the formation of new biomass, known as net primary productivity (NPP) (Malhi et al., 2015). NPP represents the net carbon gain available for growth and reproduction, and is distributed among various plant components, including stems, leaves, fine roots, and reproductive structures. To estimate the fraction of NPP contributing to aboveground biomass, this study focused on aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) (Twilley et al., 2017). ANPP was derived from gross primary productivity (GPP) using fixed carbon allocation coefficients. The relationship is expressed as:

where CUE is the proportion of GPP allocated to NPP (set to 0.375, Alongi, 2020) and b is the proportion of NPP allocated to ANPP (set to 0.5, Virgulino-Júnior et al., 2020).

Aboveground biomass (AGB) accumulation reflects the net carbon stored in structural plant components over time and can be estimated from the cumulative aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) (Wu W. et al., 2023). In this study, daily ANPP values derived from the LUE-based GPP simulations were aggregated annually, and AGB was calculated by summing ANPP over time and applying a carbon conversion factor to represent the carbon content in dry biomass. The relationship is expressed as:

where AGBt is the aboveground biomass at time t, t0 is the initial time step, ANPPt denotes the aboveground net primary productivity at time t, and C is the carbon fraction of dry biomass, set to 0.48 (Meng et al., 2021).

Model validation

To independently evaluate the accuracy of age-adjusted LUE model outputs, we conducted separate validation analyses for results of GPP and AGB. This approach aimed to assess the robustness and credibility of the proposed age-adjusted light use efficiency (LUE) model in estimating mangrove carbon dynamics.

For GPP, modeled results were compared against three widely used satellite-derived datasets: (1) the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) GPP product (MOD17A2H, 500 m), (2) the Global LAnd Surface Satellite (GLASS) GPP product (500 m), and (3) the GOSIF-GPP product, which is based on sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF). These products are generated using distinct retrieval algorithms and input variables, thus providing complementary perspectives for validating the spatial and temporal patterns of modeled GPP. Due to the coarse spatial resolution of the GPP products, we used the overall mean GPP of the study area for comparative analysis with other GPP datasets to enhance spatial comparability. GPP derived from Landsat-7 imagery was temporally upscaled to an 8-day interval using linear interpolation to improve temporal comparability with other GPP products. To quantitatively assess agreement between the modeled GPP and existing GPP products, multiple statistical metrics were calculated, including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Bias, enabling a more comprehensive comparison of model performance across space and time.

For AGB, model estimates were evaluated against two independent sources: canopy height data derived from the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) mission and field-based measurements. GEDI-based AGB was calculated using an empirical allometric equation based solely on canopy height, enabling consistent estimation at a 25 m footprint across large spatial scales (Lagomasino et al., 2016). Field AGB was estimated using species-specific allometric equations applied to tree height and diameter at breast height (DBH) measurements collected from sample plots dominated by A. corniculatum and K. obovata (Meng et al., 2021). Both GEDI and field-derived AGB values were obtained through established allometric relationships, the details of which are provided in Supplementary Text S1. The agreement between modeled AGB, remote sensing estimates, and field observations supports the robustness and reliability of the proposed biomass estimation approach.

Results

Structural characterization and age-class succession of mangrove

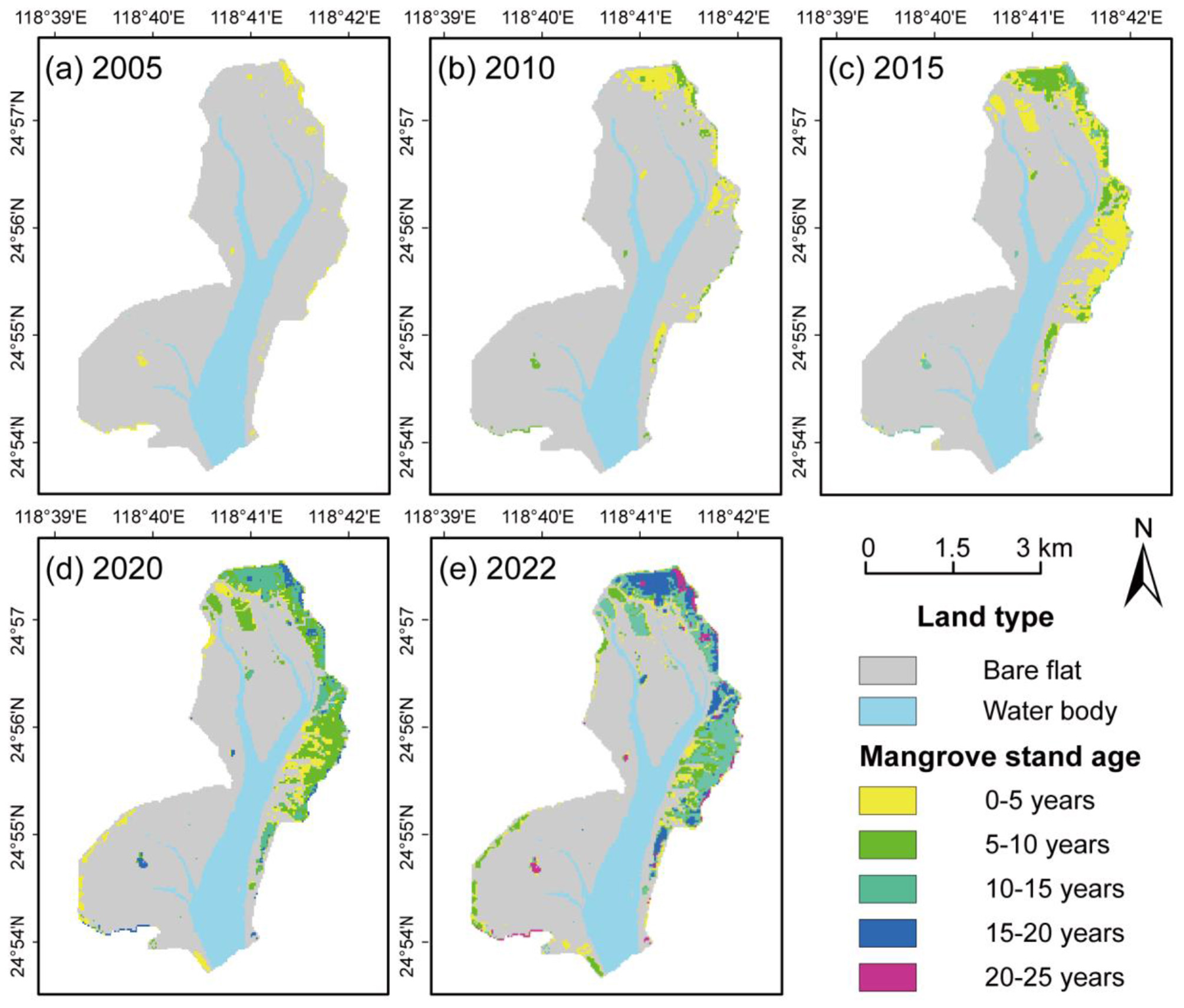

Mangrove structural dynamics require precise spatiotemporal capture for GPP estimation. Using GEE's RF classifier, land cover and mangrove age distribution were mapped (Figure 3). Stand age was determined through a temporal overlay analysis of annual mangrove distribution maps spanning 2000–2022, supplemented by local plantation records to enhance accuracy. For each pixel, the first year in which mangrove cover was detected was defined as the initiation year, and stand age was then calculated based on the number of years elapsed since that first detection. Mangrove area surged 14.5-fold from 26.37 ha (2000) to 410.04 ha (2022), driving pronounced age heterogeneity. Initial planting (2000–2005) dominated by 0–5 years stand age transitioned to 71% 0–5 years and 26% 5–10 years by 2010. The mangroves experienced their most significant area expansion between 2010 and 2015 (increased ~114 ha), with stand age composition shifting to 48% 0–5 years, 26% 5–10 years, and 26% 10–15 year. Subsequent growth to 343.26 ha (2020) showed maturing cohorts: 19% 0–5 years, 39% 5–10 years, 21% 10–15 years, and 13% 15–20 year. By 2022, established stands (≥20 years) comprised 17%, while younger classes (0–15 years) occupied 65%, exhibiting a landward-oceanward age gradient.

Figure 3

Stand age distribution of mangroves in different years. (a) 2005, (b) 2010, (c) 2015, (d) 2020, and (e) 2022.

To evaluate the classification accuracy, we employed overall accuracy (OA), the Kappa coefficient (KC), and the mean User's Accuracy and Producer's Accuracy (Mean UA and Mean PA) derived from the confusion matrix (Table 1). Overall, the results demonstrate a reliable and robust classification performance suitable for long-term mangrove mapping.

Table 1

| Metrics | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.97 | 1 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| KC | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Mean UA | 0.97 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Mean PA | 0.96 | 0.94 | 0.98 | 1 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

Summary of classification accuracy metrics.

Spatiotemporal dynamics and validation of mangrove GPP

Spatiotemporal dynamics of mangrove GPP

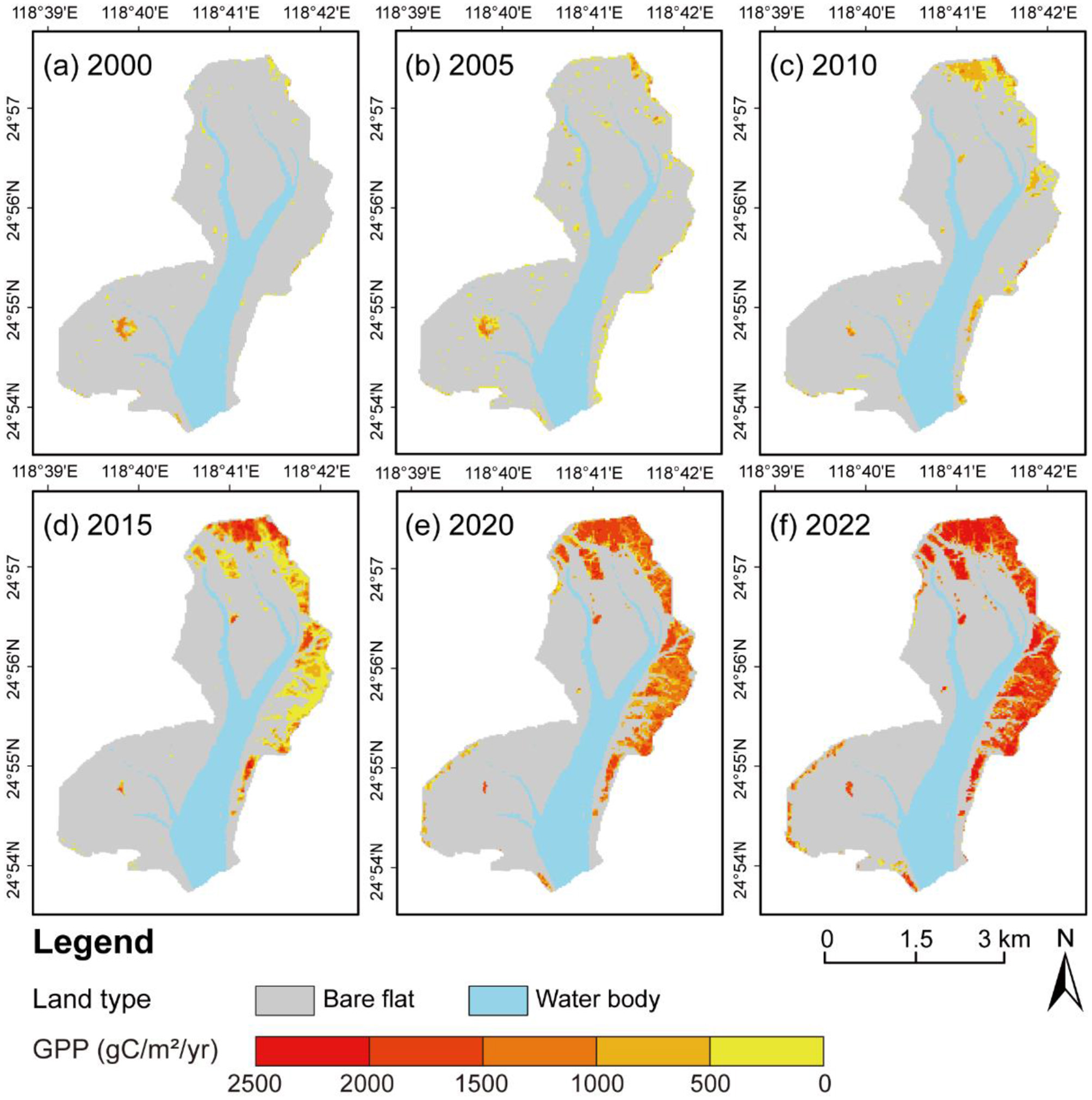

The enhanced LUE model estimated mangrove GPP from 2000 to 2022, with annual distributions shown in Figure 4. Total GPP demonstrated sustained growth from 114,654 (2000) to 5,271,952 gC·m−2·year−1 (2022), exhibiting a 46-fold increase. Annual mean GPP of vegetated cellular rose from 391.31 to 1,600.36 gC·m−2·year−1 despite a transient dip in 2005 (311.52 gC·m−2·year−1), with notable increase phases: 2000–2010 (3.1-fold) and 2015–2022 (2.3-fold). Peak productivity of vegetated cellular increased consistently, reaching 2,776.67 gC·m−2·year−1 in 2022.

Figure 4

Spatiotemporal distribution of mangrove GPP in (a) 2000, (b) 2005, (c) 2010, (d) 2015, (e) 2020, and (f) 2022.

The mangrove GPP exhibited a distinct seaward decline gradient across the study area. Maximum productivity clustered within established mangrove dominated zones near core habitats, whereas minimum values occurred along peripheral tidal flats with juvenile mangrove colonization. The distribution of GPP was highly stand age-class dependence (R2 = 0.87), demonstrating that GPP spatial patterns directly reflected the mangrove age-structure dynamics recorded between 2000 and 2022.

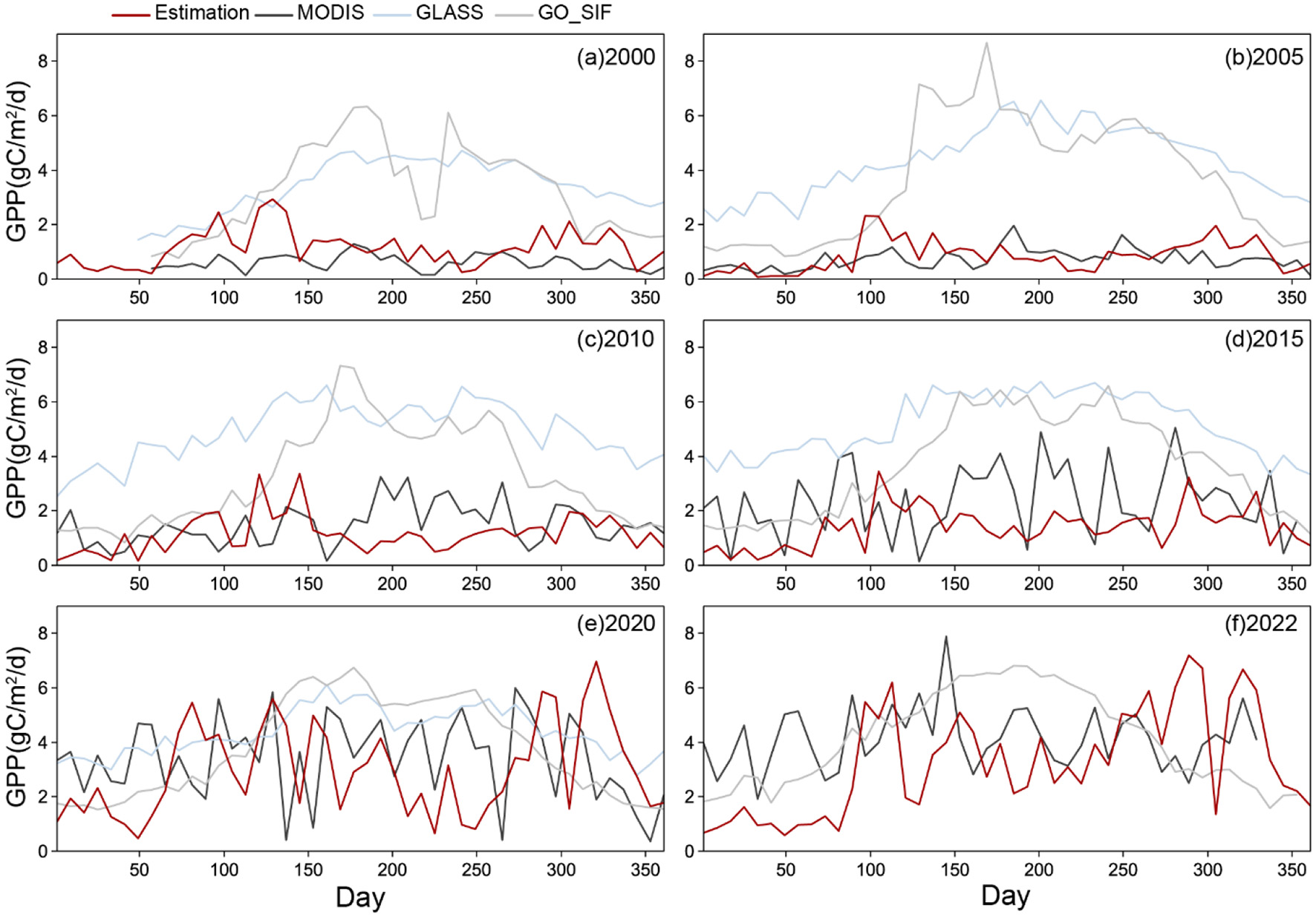

Validation of GPP estimates against existing products

To validate the reliability of the GPP estimations from the improved LUE model, the estimated mangrove GPP was compared established products (MODIS, GO_SIF, and GLASS) within the study area (Figure 5). Annually, GLASS GPP showed the highest values (peak: 1,881.94 gC·m−2·year−1 in 2015), followed by GO_SIF and MODIS, which exhibited a marked upward trend (MODIS: 221.92 to 1510.19 gC·m−2·year−1, 2000–2022). The estimated GPP values (daily spatial data at 8-day intervals) ranged from 0.06–7.19 gC·m−2·d−1 (mean: 0.61–3.26), increasing steadily over time. Relative to the model estimation, GLASS overestimated daily GPP (mean: 3.39–5.16 gC·m−2·d−1), MODIS underestimated (0.61–4.14), and GO_SIF aligned intermediately (3.24–4.13) during 2000–2022. Detailed statistical metrics are provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 5

The daily-scale spatial data at 8-day intervals of estimated mangrove GPP and GPP products (MODIS, GO_SIF, and GLASS) in (a) 2000, (b) 2005, (c) 2010, (d) 2015, (e) 2020, and (f) 2022.

Spatiotemporal dynamics and validation of mangrove AGB

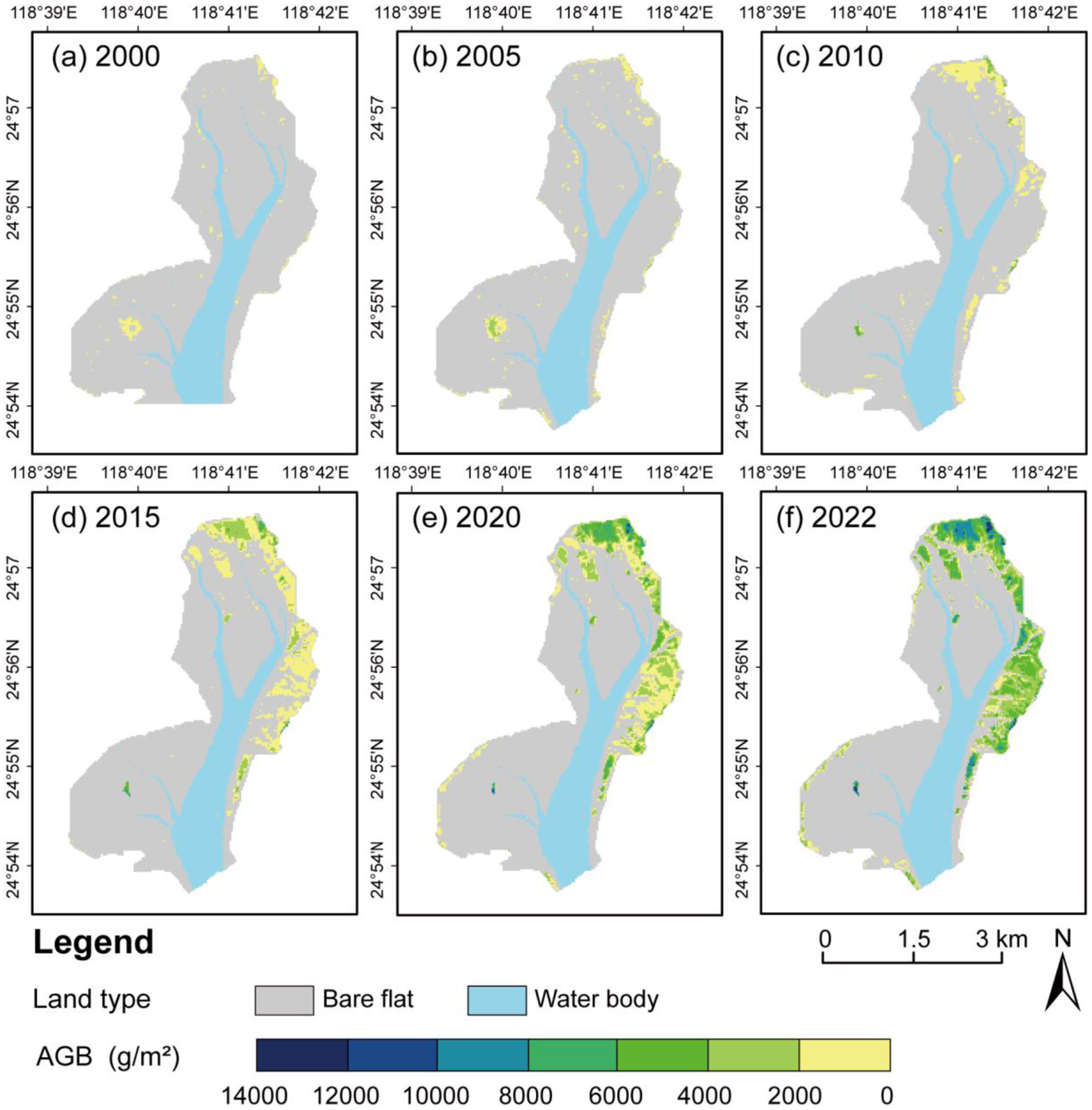

Spatiotemporal distribution of mangrove AGB

The LUE model's daily GPP simulations were aggregated to derive 30 m-resolution AGB maps (2000–2022), capturing spatiotemporal dynamics (Figure 6). The results indicate significant positive correlations between AGB levels and mangrove stand age (R2 = 0.89). Sapling stands (< 5 year) exhibited AGB < 4,000 g·m−2, young stands (5–10 Years) 4,000–7,000 g m−2, mid-rotation stands (10–15 Years) 7,000–9,000 g·m−2, pre-established stands (15–20 years) 9,000–12,000 g·m−2, and established stands (≥20 Years) surpassed 12,000 g·m−2. Spatial patterns of mangrove AGB mirrored mangrove stand age and GPP distributions, with AGB peaking in central zones and declining toward edges and from landward areas to river corridors.

Figure 6

Spatiotemporal distribution of mangrove AGB in (a) 2000, (b) 2005, (c) 2010, (d) 2015, (e) 2020, and (f) 2022.

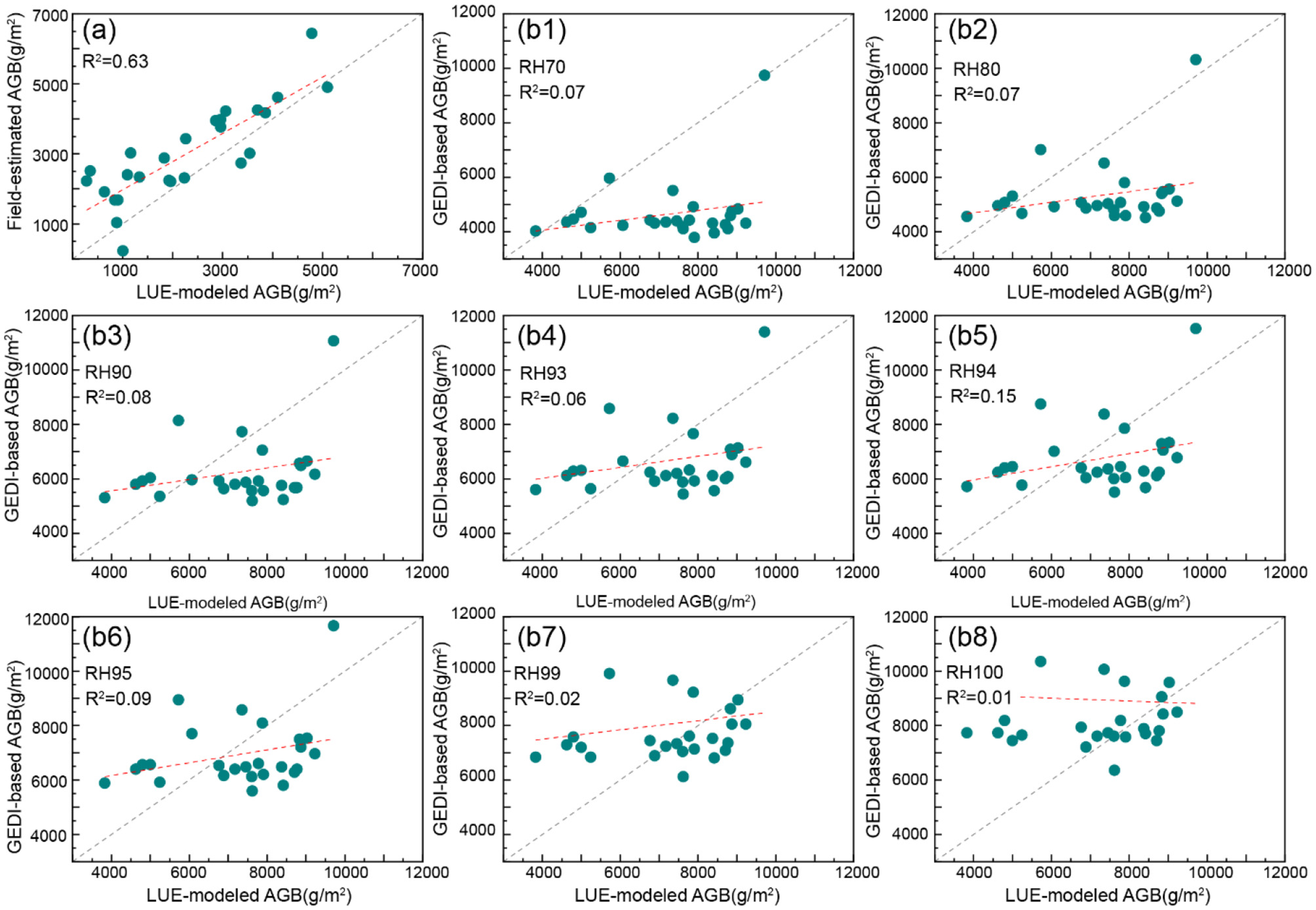

Validation of mangrove AGB using field and GEDI data

The LUE-modeled AGB estimates were validated against in-situ measurements, demonstrating moderate predictive capacity (R2 = 0.63, RMSE = 1,051 g·m−2, MAE = 892.79 g·m−2, MAPE = 44.69%) (Figure 7a). To leverage satellite-based validation, GEDI footprints overlapping decadal-scale mangrove stands (>10 Years) were analyzed using relative height (RH) metrics. Comparative analysis revealed limited correlation between LUE-derived AGB and GEDI RH94-based estimates (R2 = 0.15) (Figure 7b5), suggesting challenges in cross-sensor biomass reconciliation despite GEDI's theoretical validation potential. Linear regression of multiple RH metrics (Figures 7b1–b5) showed progressive sensitivity improvements with increasing height percentiles, though none surpassed field-data validation accuracy. When the RH metric exceeds 94, the correlation decreases with increasing RH (Figures 7b6–b8).

Figure 7

Scatter plots illustrating the coefficient of determination (R2) between (a) LUE-modeled AGB and field-measured AGB, and (b1–b8) LUE-modeled AGB and GEDI-derived AGB across different RH metrics for mangrove stands older than 10 years. The red line represents the fitted regression between LUE-modeled and reference AGB values, while the central gray line denotes the 1:1 reference line.

Mangrove carbon fluxes and AGB dynamics

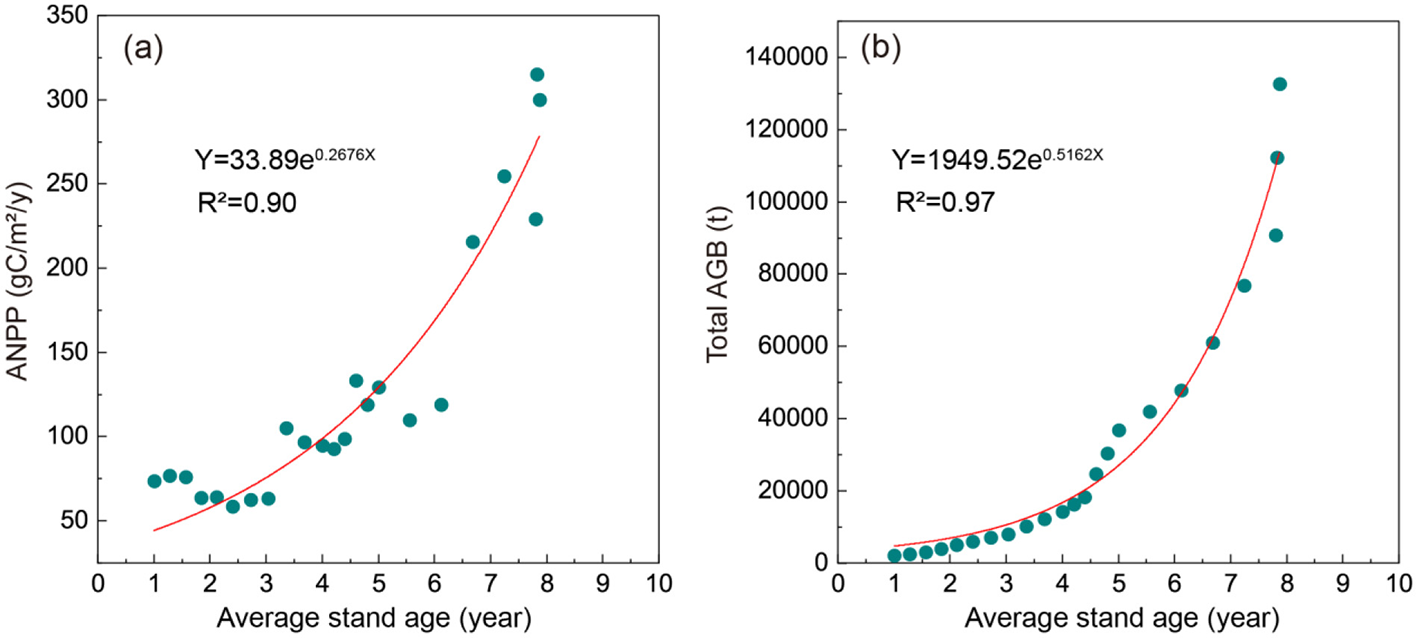

The integrated analysis of LUE-modeled GPP temporal patterns and AGB mapping revealed mangrove carbon flux dynamics and biomass accumulation trajectories. Temporal dynamics of GPP, ANPP fluxes, and AGB increments demonstrated three distinct phases (Table 2). The 2000–2007 period showed stable ANPP (58.41–76.53 gC·m−2·year−1), followed by a mean increase of 42.62 gC·m−2·year−1 during the 2008–2017 period (92.82–133.11 gC·m−2·year−1). The 2018–2022 period exhibited accelerated ANPP growth (215.63–300.07 gC·m−2·year−1). This phased progression aligns with the natural maturation patterns of mangrove stands, particularly the canopy closure phase between 2010 and 2015. ANPP (R2 = 0.90) and total AGB (R2 = 0.97) both increased exponentially with the increase of mangrove average stand age in the study area (Figure 8).

Table 2

| Year | Mangrove forest fluxes (gC·m−2year−1) | Mangrove forest AGB (t) total amounts | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPP | ANPP | ||

| 2000 | 391.31 | 73.37 | 447.87 |

| 2001 | 408.14 | 76.53 | 914.99 |

| 2002 | 404.22 | 75.79 | 1,377.87 |

| 2003 | 339.56 | 63.67 | 2,435.01 |

| 2004 | 340.49 | 63.84 | 3,495.05 |

| 2005 | 311.52 | 58.41 | 4,464.89 |

| 2006 | 333.32 | 62.50 | 5,502.63 |

| 2007 | 336.53 | 63.10 | 6,550.74 |

| 2008 | 560.70 | 105.13 | 8,771.63 |

| 2009 | 515.24 | 96.61 | 10,812.46 |

| 2010 | 505.13 | 94.71 | 12,813.26 |

| 2011 | 495.03 | 92.82 | 14,774.05 |

| 2012 | 525.34 | 98.50 | 16,854.89 |

| 2013 | 709.91 | 133.11 | 23,363.35 |

| 2014 | 634.10 | 118.89 | 29,176.73 |

| 2015 | 689.24 | 129.23 | 35,495.63 |

| 2016 | 585.85 | 109.85 | 40,866.68 |

| 2017 | 634.10 | 118.89 | 46,680.06 |

| 2018 | 1,150.02 | 215.63 | 60,089.47 |

| 2019 | 1,358 | 254.63 | 75,923.98 |

| 2020 | 1,221.41 | 229.01 | 90,189.68 |

| 2021 | 1,680.38 | 315.07 | 111,811.44 |

| 2022 | 1,600.36 | 300.07 | 132,403.59 |

Statistics of interannual averaged mangrove forest GPP, ANPP fluxes, and total AGB dynamics from 2000 to 2022.

Figure 8

ANPP and total AGB dynamics with increasing mangrove average stand age. (a) ANPP, (b) Total AGB.

Discussion

LUE model for mangrove GPP estimation

In the absence of eddy covariance (EC) validation data, our 8-day mangrove GPP estimates (0.84–3.26 gC·m−2·d−1) were cross-validated against global GPP products, revealing systematic overestimations. The GLASS GPP product exhibited the largest deviation (3.39–5.16 gC·m−2·d−1), followed by GOSIF GPP (3.24–4.13 gC·m−2·d−1). The GO_SIF GPP and GLASS GPP products were not specifically developed for mangroves, but rather for global terrestrial vegetation. Due to the different growth environment of mangroves, the GO_SIF GPP did not provide complete coverage for the study area. In contrast, the GLASS GPP product fully covered the study area, but it had a lower spatial resolution. Different model structures and parameterization schemes can result in marked discrepancies in GPP estimates (Xiao et al., 2019). The algorithms used in GLASS GPP and GO_SIF GPP differed from the approach used in this study. GO_SIF GPP was based on linear relationships between solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF) and GPP, while GLASS GPP was derived from an eddy covariance light use efficiency (EC-LUE) model (Li and Xiao, 2019; Liang et al., 2021). These factors can lead to biases in the estimation results and GPP products.

The GPP estimates from the LUE model that took forest age into account, demonstrated strong consistency with MODIS GPP (0.61-4.14 gC·m−2·d−1). This result aligns with the findings of (Zhao et al. 2023), who applied the LUE model to estimate mangrove GPP in the Gaoqiao Mangrove Reserve from 2000 to 2020. Their analysis showed the highest fitting accuracy when compared with the GLASS GPP product. The GPP values in both regions showed an increasing trend from 2000 to 2020. The mean GPP value for the Gaoqiao Mangrove Reserve ranged from 6.35 to 8.33 gC·m2·d−1, which is significantly higher than that of our study area. The annual averages of GPP in Zhangjiang were 1,729 gC·m−2 year−1 in 2012 and 1,924 gC·m−2 year−1 in 2016, while the annual mean value of GPP in Zhanjiang was 1434 gC·m−2 year−1 in 2015 (Chen et al., 2014; Zheng and Takeuchi, 2022; Zhu et al., 2019). The differences in GPP estimates across sites may be attributed to variations in the climate-hydrological conditions of the mangrove growth areas, as well as differences in forest age and species. (Zheng and Takeuchi 2022) used the LUE model to estimate mangrove GPP in China and found that GPP increased with decreasing latitude. The results from (Sun et al. 2024) also showed a geographical pattern in the global multi-year average GPP distribution, with values decreasing from around 3,000 gC·m−2 year−1 near the equator toward the poles. Subtropical regions had GPP values between 1,200 and 2,400 gC·m−2 year−1. Additionally, results based on LUE model from Wu L. et al. (2023), showed that the multi-year average annual GPP of mangroves older than 20 years in Danzhou Bay was 1,824.56 gC·m−2 year−1, which was similar to the average GPP value for this study area (1,600.36 gC·m−2 year−1) in 2022.

Recent research from the Low Isles in the Great Barrier Reef shows that above-ground biomass (AGB) increases continuously with stand age, whereas annual biomass increment (i.e., productivity) peaks during early development and subsequently declines or stabilizes as stands mature (Conroy et al., 2025). Evidence from a 66-year chronosequence in French Guiana provides similar insights: both above- and below-ground carbon stocks accumulate rapidly during the early stages of forest development, yet the annual carbon sequestration rate declines as the ecosystem ages (Walcker et al., 2018). This age–productivity pattern closely resembles the classical age–NPP curve documented for terrestrial evergreen broad-leaved forests, reinforcing the conceptual rationale for incorporating stand-age–dependent growth functions when modeling mangrove productivity. However, mangrove forests exhibit a stronger growth trajectory and greater interannual variability in productivity, likely reflecting their dynamic response to tidal regimes, hydrological conditions, and coastal disturbance processes (Zhang et al., 2024).

The LUE model that accounts for the effects of forest age, showed alignment with MODIS GPP data but has certain limitations. Firstly, it applied a static LUEmax across all mangrove species, unlike dynamic LUEmax approaches that better capture species-specific physiology and improve GPP accuracy (Xie et al., 2023; Zhang H. et al., 2023). The big-leaf (BL) scheme ignored sunlit/shaded leaf radiation heterogeneity. (Huang et al. 2024) proposed a dynamic-leaf (DL) LUE model that improved GPP estimations by more accurately reflecting the dynamically shifting configuration of the canopy under various sky conditions. Instantaneous fPAR from Landsat-7 and Sentinel-2 lacked daily precision, while MODIS temporal upscaling could enhance accuracy (Zhang Y. et al., 2023). Secondly, key drivers of mangrove productivity, such as species distribution, soil salinity, elevation, tidal cycles, and cyclone impacts (Ahmed et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023; Rasquinha and Mishra, 2021), were not included in the LUE model used in this study. Thirdly, global datasets (500 m−1 km resolution) inadequately resolve narrow coastal mangroves. Remote sensing-derived SST/SAL data exhibited spatial gaps and field measurement discrepancies (e.g., overestimated SAL), while monthly VPD averages introduced daily GPP uncertainties.

Future work should integrate dynamic LUEmax, canopy radiation dynamics, and high-resolution environmental scalars (e.g., daily VPD, salinity) to address these gaps. A unified framework incorporating species traits, tidal and climate cycles, and human disturbances (e.g., coastal development) is critical for mangrove GPP modeling. High-resolution data assimilation (e.g., in situ LUE) is essential for small-scale conservation areas, as demonstrated by (Lele et al. 2021).

GPP-converted AGB and GEDI-based AGB

This method, based on a global mangrove carbon mass balance model (Alongi, 2020), converts GPP to NPP and subsequently estimates AGB increment from NPP. A constant GPP fraction is commonly used for modeling (Amthor, 2025; Gifford, 1995; Jay et al., 2016), offering advantages in large-scale applications due to its efficiency and global applicability. In mangrove forests, biomass allocation is influenced by environmental factors such as tree diameter, soil phosphorus, sulfide concentrations, hydroperiod, and drought (CastaÃ, 2013; Virgulino-Júnior et al., 2020). Mangrove wetlands span diverse geographic areas, resulting in varying environmental conditions and tree communities (Komiyama et al., 2008), which likely affect the NPP to GPP ratio in complex ways (Collalti and Prentice, 2019). Biomass allocation is also tied to plants' adaptive ecological strategies (Pan et al., 2023). Future research could refine respiration fractions and carbon allocation ratios based on factors like soil fertility, climate, and salinity.

AGB estimated using the LUE model showed a weak correlation with values derived from allometric equations based on GEDI canopy height data. This discrepancy could stem from errors in the allometric equations, the choice of RH, or the limitations of the hybrid inference approach (which relied solely on GEDI canopy height data and allometric equations based on canopy height). This study applied a general mangrove H-AGB model (Aslan and Aljahdali, 2022), though research indicates that the H-AGB relationship in mangroves varies by location (Suwa et al., 2021). RH performance also varied by region and forest type (Potapov et al., 2021), with high RH correlating strongly with AGB, while low RH appeared more sensitive to canopy cover and terrain slope (Duncanson, 2022). The optimal RH may not have been used in this study. Both hybrid and hierarchical model-based (HMB) inference are effective for predicting AGB density using GEDI data. For study areas between 100 and 1000 ha, HMB is preferred, especially when the GEDI sampling fraction is low (Saarela et al., 2022).

GPP distribution and AGB dynamics

The spatio-temporal distribution of GPP and AGB dynamics is crucial for understanding the carbon cycle in mangrove ecosystems. Results reveal significant spatial heterogeneity in mangrove GPP, with the highest values found in older stands and central areas. Conversely, newly established mangrove zones and those closer to the coast had lower GPP. This variation aligns with mangrove age distribution, as younger stands have lower GPP due to smaller size and reduced canopy cover. These findings highlight the importance of forest age in GPP, with older mangroves showing higher productivity, a pattern consistent with other mangrove ecosystem studies (Zhao et al., 2023; Zheng and Takeuchi, 2022; Carnell et al., 2022).

From a temporal perspective, the total GPP of mangroves in the study area steadily increased from 2000 to 2022, reflecting the expansion of mangrove coverage over time. This trend is attributed to the establishment of protected areas and both artificial and natural mangrove growth. As the mangrove forest established, GPP increased due to the growth of larger trees and more developed canopies, enhancing photosynthetic capacity. This finding aligns with global studies indicating that GPP in mangroves increases with forest maturity (Walcker et al., 2018; Bunting et al., 2022; Sri Rahayu Romadhoni et al., 2022).

In terms of AGB dynamics, the results showed a strong correlation between AGB and mangrove age. AGB values were generally low in younger mangrove stands ( ≤ 5 Years), increasing steadily with forest maturity. By 2022, older mangroves (over 20 Years) had AGB values exceeding 12,000 g·m−2, while younger stands had values below 2,000 g·m−2. The distribution of AGB mirrored that of GPP, with central regions, where older mangroves were more prevalent, having the highest AGB values, and newly established areas showing lower AGB. The changes in AGB reflect the trends in GPP, with total AGB dynamics influenced by both GPP and the expansion of mangrove area. The spatial patterns of GPP and the temporal dynamics of AGB provide a basis for prioritizing restoration areas and guiding species selection. By comparing the observed productivity and biomass accumulation trajectories of restored stands with those of natural mangroves, the effectiveness and ecological equivalence of restoration measures can be evaluated. Furthermore, the integration of stand-age information enables future projections of productivity and AGB under changing climate conditions, offering valuable insights for carbon accounting, blue carbon policy development, and long-term ecosystem management.

Conclusion

This study developed an age-adaptive LUE model for mangroves, integrating forest age as a key modulator of photosynthetic efficiency. Applied to artificial mangroves in China's Luoyangjiang Estuary (2000–2022), the model accurately captured growth trajectories from young plantations to established stands, aligning with satellite-derived GPP products, particularly MODIS-GPP. Cumulative carbon fluxes, combined with species-specific biomass conversion factors, reconstructed aboveground biomass (AGB) dynamics, showing progressive accumulation linked to stand maturation. Established stands (≥20 Years) achieved biomass stocks comparable to natural ecosystems, totaling ~14,000 t by 2022.

The framework accounted for spatial-temporal heterogeneities, especially delayed canopy closure in early restoration stages. Validation against field measurements and GEDI data confirmed its reliability. Key uncertainties included scale mismatches in patchy mangrove habitats, simplified carbon allocation assumptions, and limited representation of belowground process. Despite these limitations, the temporal coherence between modeled productivity and observed biomass underscores the model's utility for monitoring restoration outcomes. The convergence of artificial and natural mangrove carbon stocks after two decades supports large-scale afforestation as an effective blue carbon strategy.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XW: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WL: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PL: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401110), and the Key Laboratory of Ocean Space Resource Management Technology, MNR (KF-2024-108).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1701038/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abatzoglou J. T. Dobrowski S. Z. Parks S. A. Hegewisch K. C. (2018). TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data5:170191. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.191

2

Ahmed S. Sarker S. K. Friess D. A. Kamruzzaman Md. Jacobs M. Islam Md. A. et al . (2022). Salinity reduces site quality and mangrove forest functions. From monitoring to understanding. Sci. Total Environ. 853:158662. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158662

3

Alongi D. M. (2020). Carbon balance in salt marsh and mangrove ecosystems: a global synthesis. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 8:767. doi: 10.3390/jmse8100767

4

Amthor J. S. (2025). After photosynthesis, what then: importance of respiration to crop growth and yield. Field Crops Res. 321:109638. doi: 10.1016/j.fcr.2024.109638

5

Aslan A. Aljahdali M. O. (2022). Characterizing global patterns of mangrove canopy height and aboveground biomass derived from SRTM data. Forests13:1545. doi: 10.3390/f13101545

6

Barr J. G. Engel V. Fuentes J. D. Fuller D. O. Kwon H. (2013). Modeling light use efficiency in a subtropical mangrove forest equipped with CO2 eddy covariance. Biogeosciences10, 2145–2158. doi: 10.5194/bg-10-2145-2013

7

Bourgeois C. F. MacKenzie R. A. Sharma S. Bhomia R. K. Johnson N. G. Rovai A. S. et al . (2024). Four decades of data indicate that planted mangroves stored up to 75% of the carbon stocks found in intact mature stands. Sci. Adv. 10:eadk5430. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adk5430

8

Bunting P. Rosenqvist A. Hilarides L. Lucas R. M. Thomas N. Tadono T. et al . (2022). Global mangrove extent change 1996–2020: global mangrove watch version 3.0. Remote Sens. 14:3657. doi: 10.3390/rs14153657

9

Carnell P. E. Palacios M. M. Waryszak P. Trevathan-Tackett S. M. Masqué P. Macreadie P. I. (2022). Blue carbon drawdown by restored mangrove forests improves with age. J. Environ. Manage. 306:114301. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114301

10

Castaà E. (2013). Allocation of biomass and net primary productivity of mangrove forests along environmental gradients in the Florida Coastal Everglades, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 307, 226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.07.011

11

Chassignet E. P. Hurlburt H. E. Smedstad O. M. Halliwell G. R. Hogan P. J. Wallcraft A. J. et al . (2007). The HYCOM (HYbrid Coordinate Ocean Model) data assimilative system. J. Mar. Syst.65, 60–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2005.09.016

12

Chave J. Réjou-Méchain M. Burquez A. Chidumayo E. Colgan M. S. Delitti W. B. et al . (2015). Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Global Change Biol.20, 3177-3190. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12629

13

Chen H. Lu W. Yan G. Yang S. Lin G. (2014). Typhoons exert significant but differential impacts on net ecosystem carbon exchange of subtropical mangrove forests in China. Biogeosciences11, 5323–5333. doi: 10.5194/bg-11-5323-2014

14

Chen K. Dong Z GongJ. (2024). Monitoring dynamic mangrove landscape patterns in China: effects of natural and anthropogenic forcings during 1985–2020. Ecol. Inform. 81:102582. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2024.102582

15

Cheng N. Zhou Y. He W. Ju W. Zhu T. Liu Y. et al . (2023). Exploring light use efficiency models capacities in characterizing environmental impacts on paddy rice productivity. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 117:103179. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2023.103179

16

Chou M.-Q. Lin W.-J. Lin C.-W. Wu H.-H. Lin H.-J. (2022). Allometric equations may underestimate the contribution of fine roots to mangrove carbon sequestration. Sci. Total Environ. 833:155032. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155032

17

Collalti A. Prentice I. C. (2019). Is NPP proportional to GPP? Waring's hypothesis 20 years on. Tree Physiol. 39, 1473–1483. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpz034

18

Conroy B. M. Hamylton S. M. Kelleway J. J. Asbridge E. F. Woodroffe C. D. Rogers K. (2025). Mangrove above-ground biomass and production are related to forest age at low isles, great barrier reef. Ecol. Evol. 15:e72048. doi: 10.1002/ece3.72048

19

Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) (2025). ERA5-Land Hourly Time-Series Data on Single Levels from 1950 to Present. Climate Data Store (CDS). Available online at: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land-timeseries

20

Dubayah R. Hofton M. Blair J. Armston J. Tang H. Luthcke S. (2021). GEDI L2A Elevation and Height Metrics Data Global Footprint Level V002. doi: 10.5067/GEDI/GEDI02_A.002

21

Duncanson L. (2022). Aboveground biomass density models for NASA's Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) lidar mission. Remote Sens. Environ. 270:112845. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2021.112845

22

Eisfelder C. Klein I. Bekkuliyeva A. Kuenzer C. Buchroithner M. F. Dech S. (2017). Above-ground biomass estimation based on NPP time-series—A novel approach for biomass estimation in semi-arid Kazakhstan. Ecol. Indic. 72, 13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.07.042

23

Erofeeva E. A. (2024). Interactions of forest carbon sink and climate change in the hormesis paradigm. J. For. Res. 35:144. doi: 10.1007/s11676-024-01795-7

24

Gifford R. M. (1995). Whole plant respiration and photosynthesis of wheat under increased CO2 concentration and temperature: long-term vs. short-term distinctions for modelling. Glob. Change Biol. 1, 385–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.1995.tb00037.x

25

Gouvêa L. P. Serrão E. A. Cavanaugh K. Gurgel C. F. D. Horta P. A. Assis J. (2022). Global impacts of projected climate changes on the extent and aboveground biomass of mangrove forests. Div. Distrib.28, 2349–2360. doi: 10.1111/ddi.13631

26

Gu X. Zhao H. Peng C. Guo X. Lin Q. Yang Q. et al . (2022). The mangrove blue carbon sink potential: evidence from three net primary production assessment methods. For. Ecol. Manage.504:119848. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119848

27

Guo Q. Du S. Jiang J. Guo W. Zhao H. Yan X. et al . (2023). Evidence from three net to estimate forest canopy mean height and aboveground biomass. Ecol. Inform. 78:102348. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoinf.2023.102348

28

Hamdan O. Khali Aziz H. Mohd Hasmadi I. (2014). L-band ALOS PALSAR for biomass estimation of Matang Mangroves, Malaysia. Remote Sens. Environ. 155, 69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2014.04.029

29

He L. Chen J. M. Pan Y. Birdsey R. Kattge J. (2012). Relationships between net primary productivity and forest stand age in U.S. forests. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26:2010GB003942. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003942

30

Hu T. Zhang Y. Su Y. Zheng Y. Lin G. Guo Q. (2020). Mapping the global mangrove forest aboveground biomass using multisource remote sensing data. Remote Sens. 12:1690. doi: 10.3390/rs12101690

31

Huang L. Yuan W. Zheng Y. Zhou Y. He M. Jin J. et al . (2024). A dynamic-leaf light use efficiency model for improving gross primary production estimation. Environ. Res. Lett. 19:014066. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ad1726

32

Huang X. Xiao J. Wang X. (2021). Improving the global MODIS GPP model by optimizing parameters with FLUXNET data. Agricult. Forest Meteorol.300:108314. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2020.108314

33

Hutchison J. Manica A. Swetnam R. Balmford A. Spalding M. (2013). Predicting global patterns in Mangrove forest biomass. Conserv. Biol.7, 233–240. doi: 10.1111/conl.12060

34

Jay S. Potter C. Crabtree R. Genovese V. Weiss D. J. Kraft M. (2016). Evaluation of modelled net primary production using MODIS and landsat satellite data fusion. Carbon Balance Manag. 11:8. doi: 10.1186/s13021-016-0049-6

35

Ju C. Fu D. Lyne V. Xiao H. Su F. Yu H. (2025). Global declines in mangrove area and carbon-stock from 1985 to 2020. Geophys. Res. Lett.52:e2025GL115303. doi: 10.1029/2025GL115303

36

Kennedy R. E. Ohmann J. Gregory M. Roberts H. Yang Z. Bell D. M. et al . (2018). An empirical, integrated forest biomass monitoring system. Environ. Res. Lett.13:025004. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/aa9d9e

37

Komiyama A. Ong J. E. Poungparn S. (2008). Allometry, biomass, and productivity of mangrove forests: a review. Aquat. Bot.89, 128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.006

38

Lagomasino D. Fatoyinbo T. Lee S. Feliciano E. Trettin C. Simard M. (2016). A comparison of mangrove canopy height using multiple independent measurements from land, air, and space. Remote Sens. 8:327. doi: 10.3390/rs8040327

39

Lele N. Kripa M. K. Panda M. Das S. K. Nivas A. H. Divakaran N. et al . (2021). Seasonal variation in photosynthetic rates and satellite-based GPP estimation over mangrove forest. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193:61. doi: 10.1007/s10661-021-08846-0

40

Li P. Li H. Si B. Zhou T. Zhang C. Li M. (2024). Mapping planted forest age using LandTrendr algorithm and landsat 5–8 on the loess plateau, China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 344:109795. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109795

41

Li X. Xiao J. (2019). Mapping photosynthesis solely from solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence: a global, fine-resolution dataset of gross primary production derived from OCO-2. Remote Sens. 11:2563. doi: 10.3390/rs11212563

42

Liang S. Cheng J. Jia K. Jiang B. Liu Q. Xiao Z. et al . (2021). The Global Land Surface Satellite (GLASS) Product Suite. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, 323–337. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0341.1

43

Liao Z. Zhou B. Zhu J. Jia H. Fei X. (2023). A critical review of methods, principles and progress for estimating the gross primary productivity of terrestrial ecosystems. Front. Environ. Sci. 11:1093095. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2023.1093095

44

Lin W. Li S. H. Wei X. et al . (2025). Assessment of wetland sustainability capacity of artificial mangrove wetland on landscape scale: a case of Luoyangjiang River Estuary, China. Ecol. Eng. 214:107561. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2025.107561

45

Lovelock C. E. Bennion V. De Oliveira M. Hagger V. Hill J. W. Kwan V. et al . (2024). Mangrove ecology guiding the use of mangroves as nature-based solutions. J. Ecol. 112, 2139–2154. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.14383

46

Lu C. Liu J. Jia M. Liu M. Man W. Fu W. et al . (2018). Dynamic analysis of mangrove forests based on an optimal segmentation scale model and multi-seasonal images in Quanzhou Bay, China. Remote Sens. 10:2020. doi: 10.3390/rs10122020

47

Malhi Y. Doughty C. E. Goldsmith G. R. Metcalfe D. B. Girardin C. A. J. Marthews T. R. et al . (2015). The linkages between photosynthesis, productivity, growth and biomass in lowland amazonian forests. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2283–2295. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12859

48

Meng Y. Bai J. Gou R. Cui X. Feng J. Dai Z. et al . (2021). Relationships between above- and below-ground carbon stocks in mangrove forests facilitate better estimation of total mangrove blue carbon. Carbon Balance Manag. 16:8. doi: 10.1186/s13021-021-00172-9

49

Monteith J. L. (1972). Solar Radiation and Productivity in Tropical Ecosystems. J. Appl. Ecol. 9:747. doi: 10.2307/2401901

50

Pan Y. Zhang Z. Zhang M. Huang P. Dai L. Ma Z. et al . (2023). Climate vs. nutrient control: a global analysis of driving environmental factors of wetland plant biomass allocation strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 406:136983. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136983

51

Panda M. Dash B. R. Sahu S. C. (2025). Ecosystem carbon stock variation along forest stand ages: insight from eastern coast mangrove ecosystem of India. Ecol. Process.14:14. doi: 10.1186/s13717-025-00580-6

52

Pei Y. Dong J. Zhang Y. Yuan W. Doughty R. Yang J. et al . (2022). Evolution of light use efficiency models: improvement, uncertainties, and implications. Agric. For. Meteorol. 317:108905. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2022.108905

53

Pham L. T. H. Brabyn L. (2017). Monitoring mangrove biomass change in Vietnam using SPOT images and an object-based approach combined with machine learning algorithms. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 128, 86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2017.03.013

54

Potapov P. Li X. Hernandez-Serna A. Tyukavina A. Hansen M. C. Kommareddy A. et al . (2021). Mapping global forest canopy height through integration of GEDI and Landsat data. Remote Sens. Environ. 253:112165. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2020.112165

55

Rahman M. M. Zimmer M. Ahmed I. et al . (2021). Co-benefits of protecting mangroves for biodiversity conservation and carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 12:3875. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24207-4

56

Raich J. W. Rastetter E. B. Melillo J. M. Kicklighter D. W. Steudler P. A. Peterson B. J. et al . (1991). Potential net primary productivity in south america: application of a global model. Ecol. Appl. 1, 399–429. doi: 10.2307/1941899

57

Rasquinha D. N. Mishra D. R. (2021). Tropical cyclones shape mangrove productivity gradients in the Indian subcontinent. Sci. Rep. 11:17355. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96752-3

58

Restrepo H. I. Montes C. R. Bullock B. P. Mei B. (2022). The effect of climate variability factors on potential net primary productivity uncertainty: an analysis with a stochastic spatial 3-PG model. Agric. For. Meteorol. 315:108812. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2022.108812

59

Richard L. Ruben V. Viviana O. Antoine C. Christophe P. (2020). Structural characterisation of mangrove forests achieved through combining multiple sources of remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ.237:111543. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.111543

60

Running S. W. Zhao M. (2021). Daily GPP and Annual NPP (MOD17A2H/A3H) and Year-end Gap-Filled (MOD17A2HGF/A3HGF) Products NASA Earth Observing System MODIS Land Algorithm (For Collection 6.1).

61

Saarela S. Holm S. Healey S. P. Patterson P. L. Yang Z. Andersen H.-E. et al . (2022). Comparing frameworks for biomass prediction for the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation. Remote Sens. Environ. 278:113074. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2022.113074

62

Shang R. Chen J. M. Xu M. Lin X. Li P. Yu G. et al . (2023). China's current forest age structure will lead to weakened carbon sinks in the near future. Innovation4:100515. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100515

63

Song S. Ding Y. Li W. Meng Y. Zhou J. Gou R. et al . (2023). Mangrove reforestation provides greater blue carbon benefit than afforestation for mitigating global climate change. Nat. Commun. 14:756. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36477-1

64

Sri Rahayu Romadhoni L. As-syakur Abd. R. Hidayah Z. Budi Wiyanto D. Safitri R. Yusuf Satriyana Utama R. et al . (2022). Annual characteristics of gross primary productivity (GPP) in mangrove forest during 2016-2020 as revealed by sentinel-2 remote sensing imagery. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1016:012051. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/1016/1/012051

65

Sun Z. An Y. Kong J. Zhao J. Cui W. Nie T. et al . (2024). Exploring the spatio-temporal patterns of global mangrove gross primary production and quantifying the factors affecting its estimation, 1996-2020. Sci. Total Environ. 908:168262. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168262

66

Sunil Kumar S. Kandasamy K. (2019). The age and species composition of mangrove forest directly influence the net primary productivity and carbon sequestration potential. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 20:101235. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101235

67

Suwa R. Rollon R. Sharma S. Yoshikai M. Albano G. M. G. Ono K. et al . (2021). Mangrove biomass estimation using canopy height and wood density in the South East and East Asian regions. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.248:106937. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2020.106937

68

Tahmouresi M. S. Niksokhan M. H. Ehsani A. H. (2024). Enhancing spatial resolution of satellite soil moisture data through stacking ensemble learning techniques. Sci. Rep. 14:25454. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-77050-0

69

Tang Y. Li T. Yang X.-Q. Chao Q. Wang C. Lai D. Y. F. et al . (2023). Mango-GPP: a process-based model for simulating gross primary productivity of mangrove ecosystems. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 15:e2023MS003714. doi: 10.1029/2023MS003714

70

Tian L. Wu X. Tao Y. Li M. Qian C. Liao L. et al . (2023). Review of remote sensing-based methods for forest aboveground biomass estimation: progress, challenges, and prospects. Forests14:1086. doi: 10.3390/f14061086

71

Tian X. Yan M. van der Tol C. Li Z. L. Su Z. B. Chen E. X. et al . (2017). Modeling forest above-ground biomass dynamics using multi-source data and incorporated models: a case study over the qilian mountains. Agric. For. Meteorol. 246, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.05.026

72

Twilley R. R. Castañeda-Moya E. Rivera-Monroy V. H. Rovai A. (2017). “Productivity and carbon dynamics in mangrove wetlands,” in Mangrove Ecosystems: A Global Biogeographic Perspective, eds. V. H. Rivera-Monroy, S. Y., Lee, E., Kristensen, R. R., Twilley (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 113–162.

73

Virgulino-Júnior P. C. C. Carneiro D. N. Jr W. R. N. Cougo M. F. Fernandes M. E. B. (2020). Biomass and carbon estimation for scrub mangrove forests and examination of their allometric associated uncertainties. PLoS ONE15:e0230008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230008

74

Virkkala A.-M. Aalto J. Rogers B. M. Tagesson T. Treat C. C. Natali S. M. et al . (2021). Statistical upscaling of ecosystem CO2 fluxes across the terrestrial tundra and boreal domain: regional patterns and uncertainties. Global Change Biol.27, 4040–4059. doi: 10.1111/gcb.15659

75

Walcker R. Gandois L. Proisy C. Corenblit D. Mougin É. Laplanche C. et al . (2018). Control of “blue carbon” storage by mangrove ageing: evidence from a 66-year chronosequence in French Guiana. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 2325–2338. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14100

76

Wang A. Zhang M. Chen E. Zhang C. Han Y. (2024). Impact of seasonal global land surface temperature (LST) change on gross primary production (GPP) in the early 21st century21. Sustain. Cities Soc. 110:105572. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2024.105572

77

Wang B. Li M. Fan W. Yu Y. Chen J. (2018). Relationship between net primary productivity and forest stand age under different site conditions and its implications for regional carbon cycle study. Forests9:5. doi: 10.3390/f9010005

78

Wang C. W. Wong S. L. Liao T. S. Weng J. H. Chen M. N. Huang M. Y. et al . (2022). Photosynthesis in response to salinity and submergence in two Rhizophoraceae mangroves adapted to different tidal elevations. Tree Physiol. 42, 1016–1028. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpab167

79

Wang S. Ibrom A. Bauer-Gottwein P. Garcia M. (2018). Incorporating diffuse radiation into a light use efficiency and evapotranspiration model: an 11-year study in a high latitude deciduous forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 248, 479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2017.10.023

80

Wang S. Zhou L. Chen J. Ju W. Feng X. Wu W. (2011). Relationships between net primary productivity and stand age for several forest types and their influence on China's carbon balance. J. Environ. Manage. 92, 1651–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.01.024

81

Wu L. Guo E. An Y. Xiong Q. Shi X. Zhang X. et al . (2023). Evaluating the losses and recovery of gpp in the subtropical mangrove forest directly attacked by tropical cyclone: case study in Hainan Island. Remote Sens. 15:2094. doi: 10.3390/rs15082094

82

Wu W. Zhang J. Bai Y. (2023). Aboveground biomass dynamics of a coastal wetland ecosystem driven by land use/land cover transformation. Remote Sens. 15:3966. doi: 10.3390/rs15163966

83

Xiao J. Chevallier F. Gomez C. (2019). Remote sensing of the terrestrial carbon cycle: a review of advances over 50 years. Remote Sens. Environ. 233:111383. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2019.111383

84

Xie Z. Zhao C. Zhu W. Zhang H. Fu Y. H. (2023). A radiation-regulated dynamic maximum light use efficiency for improving gross primary productivity estimation. Remote Sens. 15:1176. doi: 10.3390/rs15051176

85

Xu X. Zhou G. Du H. Mao F. Xu L. Li X. et al . (2020). Combined MODIS land surface temperature and greenness data for modeling vegetation phenology, physiology, and gross primary production in terrestrial ecosystems MODIS. Sci. Total Environ. 726:137948. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137948

86

Yang Y. Ye X. Wang A. (2023). Dynamic changes in landscape pattern of mangrove wetland in estuary area driven by rapid urbanization and ecological restoration: a case study of the Luoyangjiang River Estuary, Fujian Province, China. Water15:1715. doi: 10.3390/w15091715

87

Yu M. Cao Y. Tian J. Ren B. (2025). Increased contribution of extended vegetation growing season to boreal terrestrial ecosystem GPP enhancement. Remote Sens. 17:83. doi: 10.3390/rs17010083

88

Zhang H. Bai J. Sun R. Wang Y. Xiao Z. Song B. (2023). An improved light use efficiency model by considering canopy nitrogen concentrations and multiple environmental factors. Agric. For. Meteorol. 332:109359. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109359

89

Zhang L.-X. Zhou D.-C. Fan J.-W. Hu Z.-M. (2015). Comparison of four light use efficiency models for estimating terrestrial gross primary production. Ecol. Model. 300, 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.01.001

90

Zhang Z. Luo X. Friess D. A. Wang S. Li Y. Li Y. (2024). Stronger increases but greater variability in global mangrove productivity compared to that of adjacent terrestrial forests. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 239–250. doi: 10.1038/s41559-023-02264-w

91

Zhang Z. Xu N. Li Y. Li Y. (2022). Sub-continental-scale mapping of tidal wetland composition for east asia: A novel algorithm integrating satellite tide-level and phenological features. Remote Sens. Environ. 269:112799. doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2021.112799

92

Zhang Y. Hu Z. Wang J. Gao X. Yang C. Yang F. et al . (2023). Temporal upscaling of MODIS instantaneous FAPAR improves forest gross primary productivity (GPP) simulation. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinform.121:103360. doi: 10.1016/j.jag.2023.103360

93

Zhao D. Zhang Y. Wang J. Zhen J. Shen Z. Xiang K. et al . (2023). Spatiotemporal dynamics and geo-environmental factors influencing mangrove gross primary productivity during 2000–2020 in Gaoqiao Mangrove Reserve, China. For. Ecosyst. 10:100137. doi: 10.1016/j.fecs.2023.100137

94

Zheng Y. Takeuchi W. (2022). Estimating mangrove forest gross primary production by quantifying environmental stressors in the coastal area. Sci. Rep. 12:2238. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-06231-6

95

Zheng Y. Zhang L. Xiao J. Yuan W. Yan M. Li T. et al . (2018). Sources of uncertainty in gross primary productivity simulated by light use efficiency models: model structure, parameters, input data, and spatial resolution. Agric. For. Meteorol. 263, 242–257. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.08.003

96

Zhu X. Song L. Weng Q. Huang G. (2019). Linking in situ photochemical reflectance index measurements with mangrove carbon dynamics in a subtropical coastal wetland. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci.124, 1714–1730. doi: 10.1029/2019JG005022

Summary

Keywords

age dependence, blue carbon, coastal restoration, gross primary production, mangrove, process-based model

Citation

Li S, Wei X, Lin W and Li P (2026) A novel light use efficiency model incorporating stand age to improve monitoring of mangrove productivity and biomass accumulation. Front. For. Glob. Change 8:1701038. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1701038

Received

09 September 2025

Revised

09 December 2025

Accepted

29 December 2025

Published

21 January 2026

Volume

8 - 2025

Edited by

Simona Niculescu, Université de Bretagne Occidentale, France

Reviewed by

Asamaporn Sitthi, Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand

ChiNguyen Lam, Can Tho University, Vietnam

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Li, Wei, Lin and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Lin, ecolinwei@gmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.