Abstract

Global climate change is a major challenge for forestry because it fundamentally alters the growth conditions of tree species. Sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.), often overlooked in forest management, is increasingly recognized as a valuable species for sustainable forestry in Central Europe. This tree species offers a unique combination of high economic and ecological value, characterized by rapid juvenile growth, abundant natural regeneration, and adaptability to diverse environmental conditions, including mountainous regions. Its contribution to biodiversity, nutrient cycling and soil stabilization underlines its ecological importance. Despite its many advantages, sycamore maple faces significant threats from global climate change, such as prolonged drought and increased susceptibility to pathogens. Nevertheless, its genetic diversity and phenotypic plasticity allow it to thrive in diverse habitats, including areas affected by human activities. This review synthesizes current knowledge of the species distribution, site requirements, silviculture, and associated threats and provides an economic evaluation of sycamore maple wood assortments. Its wood is highly valued for its exceptional versatility and quality, underlining its economic attractiveness. To maximize its potential, effective forest management practices are essential. These include strategies such as establishing mixed stands and implementing careful regeneration techniques to ensure the species’ resilience in the face of climate change. By incorporating ecological, economic, and climate-resilience perspectives, this review demonstrates the vital role of sycamore maple in sustainable forestry and biodiversity conservation in Central Europe. The results highlight its ecological and adaptive capacity and economic viability as a resource for future forest ecosystems.

1 Introduction

Global climate change (GCC) poses a major challenge for forestry, as it alters the environmental conditions under which forest tree species grow (Hamrick, 2004; Keenan, 2015; Vacek et al., 2023). Therefore, selecting suitable tree species is crucial for maintaining the productive functions of forests and ensuring the long-term stability of forest ecosystems (Dyderski et al., 2018; Vacek et al., 2023). An optimal tree species should provide high-quality timber while also being resilient to the adverse effects of GCC, such as long-term drought, extreme temperatures, and emerging pests (Allen et al., 2010; Seidl et al., 2017). Additionally, it should have high biomass productivity, including significant carbon sequestration, to contribute to GCC mitigation efforts and the sustainability of forest ecosystems (Nunes et al., 2020; Cukor et al., 2022). In the context of European forests, it is essential to identify tree species that can meet these demanding requirements (Vacek et al., 2023). Often overlooked in forest management, the sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) shows great potential as a species capable of meeting these challenges (Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Pasta et al., 2016).

The sycamore maple is a broad-leaved tree species with high economic and ecological value. It grows widely in mixed forests throughout Central Europe and is classified as a valuable broadleaf tree species (Leslie, 2005; Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Spiecker et al., 2009; Vacek S. et al., 2018; Pretzsch, 2022). Its original distribution was concentrated on the higher altitudes of Central Europe (Ellenberg, 1996). The species has been introduced into Macaronesia, North America (New England and the Pacific Northwest), Argentina (northern Patagonia), Australia, New Zealand, and India (Kölling and Zimmermann, 2007; Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Weidema and Buchwald, 2010). It is expected that forests containing sycamore maple will expand in the future due to its high adaptability and high genetic diversity to a wide range of conditions in mountainous and submontane areas, its competitive ability, and its high natural regeneration potential, particularly in the context of ongoing GCC (Leslie, 2005; Kölling and Zimmermann, 2007; Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Simon et al., 2010; Vacek S. et al., 2018).

A major competitive advantage of the sycamore maple, compared to associated tree species, is its abundant and easy natural regeneration, as well as its rapid juvenile growth, provided it is not damaged by browsing animals (Kupferschmid and Bugmann, 2008; Nagel et al., 2014). With increasing light availability in young stands, it gains significant height growth dominance over European beech (Petritan et al., 2007). The sycamore maple notably enhances the biodiversity and the ecological stability of forest ecosystems (Binggeli, 1993; Pommerening, 1997; Bell, 2009) and acts as an ameliorative species, promoting humus formation and nutrient cycling (Weber et al., 1993; Heitz, 2000; Vacek S. et al., 2018). It produces highly valuable and versatile timber for the wood-processing industry (Núńez-Regueira et al., 1997; Soulčres, 1997; Becker and Klädtke, 2009; Quambusch et al., 2021). For these reasons, it may play a more important role in forestry and the wood industry in Central Europe soon (Spiecker et al., 2009; Thies et al., 2009). On the other hand, in the context of GCC, the invasive potential of the sycamore maple on moist and nutrient-rich sites should be considered, as it can sometimes outcompete native species in forest stands (Lichstein et al., 2004; Weidema and Buchwald, 2010; Straigyte and Baliuckas, 2015; Dyderski et al., 2025). However, their future role must also consider the increasing threat of prolonged droughts and secondary pathogens, which are expected to become more frequent with GCC on sycamore maple (Hemery et al., 2010).

This comprehensive literature review of 205 studies aims to thoroughly assess the role, opportunities, and risks associated with sycamore maple in European forestry. Specifically, the focus is to provide a detailed overview of (i) species morphology and distribution, (ii) site and ecological requirements, (iii) silviculture and forest production, (iv) importance and uses, and (v) threats and diseases, with an emphasis on the impact of the ongoing GCC.

2 Materials and methods

This review was compiled through a thorough examination of both recent and historical scientific literature on sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) in Europe, with a focus on its biology, distribution, ecological range, silvicultural management, wood properties, economic significance, and responses to ongoing global climate change. The final dataset included 205 sources covering the last 100 years (1925–2025), encompassing peer-reviewed journal articles indexed in Web of Science (WoS) or Scopus, scholarly monographs, conference papers, and additional technical materials such as research reports. Non-peer-reviewed or unverified publications were systematically excluded to maintain high scientific credibility. Literature was identified through major academic search platforms, including the WoS Core Collection, Scopus, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and the electronic resources of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague. Specific keyword combinations were employed to retrieve relevant studies, including terms such as Acer pseudoplatanus and sycamore together with silviculture, forest management, production, wood, economic, ecology, diseases, climate change, and Europe. Additional sources were incorporated following recommendations from three independent reviewers to ensure the comprehensiveness of the review article.

3 Morphological description

Sycamore maple is a large deciduous tree that grows to a height of 30–35 (40) m with a diameter at breast height of 60–80 (150) cm (Mitchell, 1974; Musil, 2005). The tree with the largest girth is from Italy, measuring 8.84 m, and the tallest tree is from Poland, standing at 40.7 m. The sycamore maple typically lives for 350–500 years, with the oldest specimen from Switzerland reaching approximately 725 years (Monumental Trees, 2025). Its crown is cylindrical to oval when in dense stands, but very broad and almost spherical when isolated, sometimes exceeding the tree’s height (Musil, 2005; Praciak et al., 2013). In richer, fresher sites, the crown is usually long and narrow, often with strong branches in the lower part of the crown. The trunk is straight and cylindrical. The bark is gray and smooth in young trees, darkening and thickening with age and peeling off in scales or plates (Mitchell, 1974; Úradníček et al., 2001; Musil, 2005). The root system is highly branched (Mauer et al., 2007), which makes the tree quite wind resistant despite its often large crown (Úradníček et al., 2001; Praciak et al., 2013). The buds are oval, covered with several green scales, measuring 8–15 mm, with the largest being the terminal bud. The twigs are greenish gray (Musil, 2005). The leaves are simple, opposite, usually five-lobed, with lobes forming sharp angles, often with hairy veins, a heart-shaped base, and serrated edges (Figure 1). Their shape and size vary considerably with the age and strength of the shoot, with young, strong individuals producing leaves up to 18 cm × 26 cm in size. The upper side of the leaves is dark green, and young trees have a yellowish underside, while older trees have a yellow underside with pink petioles (Mitchell, 1974; Humphries et al., 1992; Úradníček et al., 2001; Musil, 2005).

FIGURE 1

Tree habitus, branch with leaves and inflorescences, fruits (samaras) and seeds of sycamore maple (Author: Josef Macek).

It is a monoecious species that can begin flowering at the age of 10–20 years. The yellow-green flowers, hanging in 6–16 cm long clusters, appear simultaneously with or shortly after leaf bud break (Úradníček et al., 2001; Musil, 2005). They are pollinated by insects, mainly bees, including honeybees, bumblebees, and solitary bees, but inflorescences of sycamore are also visited by various dipterans and beetles (Hegi, 1925; Williams et al., 1993; Chrzanowska et al., 2024). Each cluster can produce up to 30 fruits, and a tree may have more than 800 clusters (Jones, 1945). It reaches fruiting peak between 40 and 60 years of age (El Kateb, 1992). It fruits almost annually, with seed years occurring at 2–3-year intervals (Pagan, 1997). However, at higher altitudes, the flowering and seed production of the sycamore can be highly variable and sparse (Krabel and Wolf, 2013). GCC, especially increased annual mean air temperature, may positively affect this cycle in terms of seed production and the frequency of seed years (Vacek et al., 2023). The fruit is a pair of fused samaras, 3–6 cm long and about 1.5 cm wide, forming a sharp angle of 60–80°. The seed capsules are hemispherical, and the samaras have short green stalks, with the seeds maturing in the autumn (Humphries et al., 1992; Rushforth, 1999; Musil, 2005). The seeds fall from October through the winter and germinate early in the spring. They remain viable for up to 1 year (Musil, 2005). The samaras are dispersed by wind over approximately 200 m from the parent tree (Tillisch, 2001). Hegi (1925) reports wind dispersal distances of up to 4 km. The seeds have high germination rates, ensuring successful natural regeneration (Ammer, 1996; Hérault et al., 2004; Ambrazevicius, 2016).

The sycamore maple is a highly variable tree species. The greatest variability concerns the shape, size, and color of the leaves, the characteristics of the bark, the fruits, and the timing of bud break. Individuals with bark that peels off in large plates are classified as the squamosum form (Figure 2), while those with scaly peeling bark are classified as the conchatum form. Early flushing types are called the praecox form, and late flushing types are referred to as the serotinum form (Svoboda, 1955; Musil, 2005).

FIGURE 2

Sycamore maple individuals with the squamosum bark form (Photo: Igor Štefančík).

4 Taxonomic classification

The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus was the first to classify this tree species in his seminal work Species Plantarum published in 1753. This species, recognized as the sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.), is the type species of the genus Acer and belongs to the family Sapindaceae (Krabel and Wolf, 2013). This family encompasses approximately 130 species of maples found across diverse regions of the Northern Hemisphere (Bi et al., 2016). From a taxonomic perspective, the sycamore maple exhibits considerable morphological variability. Researchers have described various forms and natural varieties of this species. Notable examples include macrocarpum Spach, which is characterized by its larger fruits; microcarpum Spach, characterized by its smaller fruits; and tomentosum Tausch, distinguished by dense pubescence on its leaves and twigs. Additionally, several specific forms have been described, such as f. erythrocarpum (Carrière) Pax with red-colored fruits, f. purpureum (Loudon) Rehder with purple foliage, and f. variegatum (Weston) Rehder, known for its variegated leaves (Gelderen et al., 1994).

Recent advances in taxonomic studies combining morphological assessments with molecular data have revealed that wide previously described varieties and forms are not independent taxa (Grimm et al., 2007). Instead, these variations represent phenotypic adaptations within a highly versatile species. As a result, most previous classifications have been revised, and these taxa are now synonymized under Acer pseudoplatanus L. (Gelderen et al., 1994). In the past few decades, extensive research has explored the high genetic diversity of the tree species (Luo et al., 2006; Pandey et al., 2012; Neophytou et al., 2019). However, no significant correlation was found between the genetic and geographic distances of populations, which confirms the absence of barriers to gene flow. This genetic diversity underscores the adaptability of the species to different ecological conditions and likely contributes to its wide distribution (Belletti et al., 2007; Rebrean F. et al., 2019).

5 Natural range and distribution

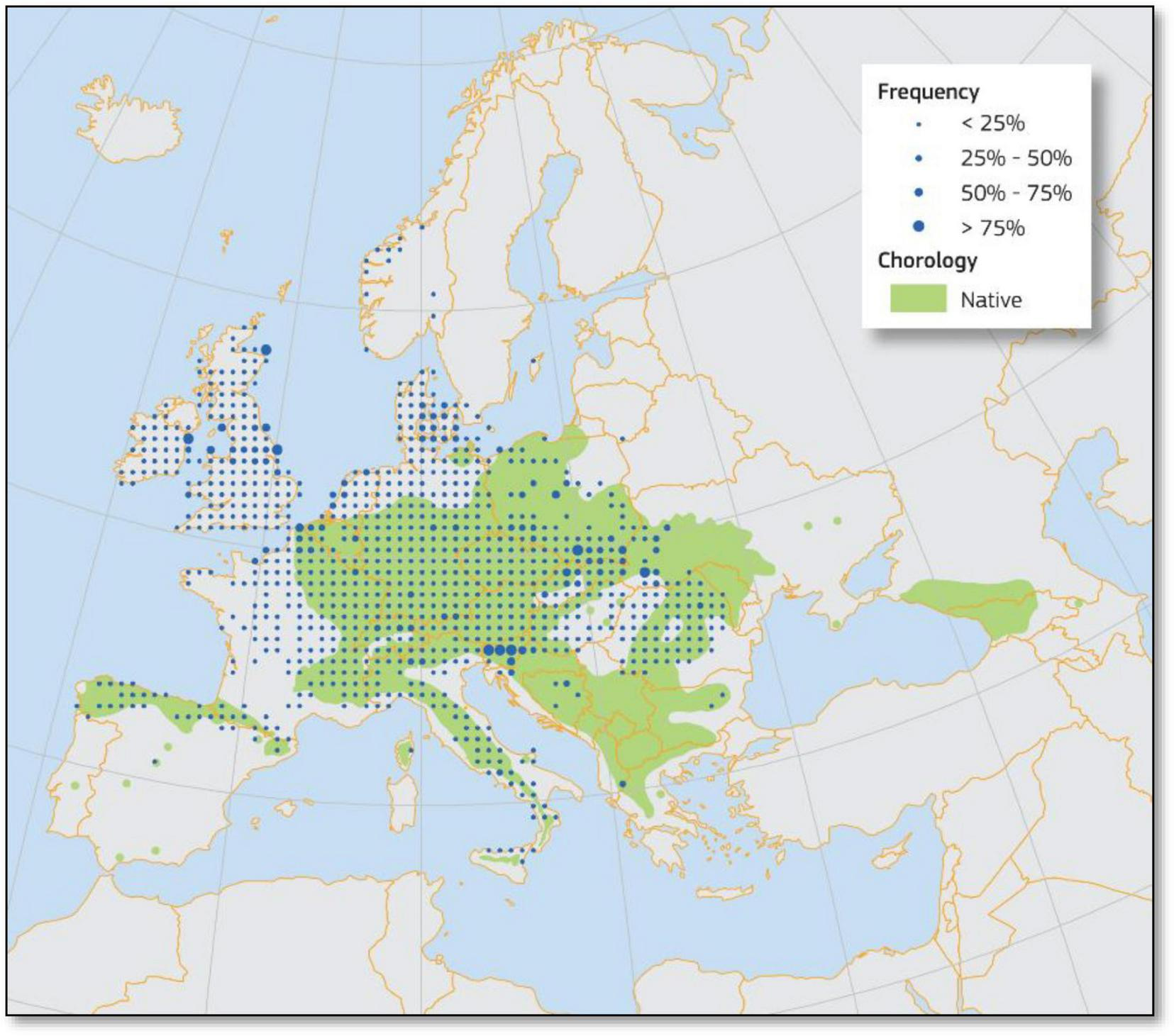

The natural range of sycamore maple is extensive, covering much of Central and Eastern Europe and the mountainous regions of Southern Europe between 51 and 35° north latitude (Figure 3). In the south, its range includes the Apennines, the Dinaric Alps, the Caucasus, and areas north of Asia Minor. Its northern boundary is located in southern Denmark, around 55° N (Meusel and Jäger, 1998). The species’ native range also encompasses regions in Germany (Harz Mountains), Russia (Crimea and the Caucasus), Spain (Pyrenees), southern and central France, the Swiss Alps, Italy, Bosnia, northern Greece, Poland and the Carpathians in Slovakia, Romania, Ukraine, and Serbia. It is typically found at altitudes between 500 and 1,900 m. Its potential post-glacial expansion, particularly the location of its refugia in Southern Europe, remains unclear (Skov and Svenning, 2004). It is not native to the UK, Ireland, Belgium, the Netherlands, northwestern France, northern Germany, or Scandinavia. The species has been extensively planted in Europe since the 18th century, particularly in the UK and Scandinavia (Rusanen and Myking, 2003) and has even been introduced to other continents such as North and South America, New Zealand, Australia, and India (Hills et al., 2008; Weidema and Buchwald, 2010; Ryall, 2010; Shouman et al., 2017).

FIGURE 3

Distribution map of sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) in Europe (Pasta et al., 2016).

In recent decades, GCC has influenced the distribution patterns of many tree species, including sycamore maple. The upward shift of suitable habitats to higher altitudes and latitudes is contributing to the expansion of sycamore maple beyond its historical range, particularly in regions previously too cold for its survival (Hemery et al., 2010; Vacek et al., 2023). This trend is consistent with broader patterns of species range shifts observed globally as ecosystems adapt to changing climatic conditions (Hanewinkel et al., 2013). From the perspective of GCC, sycamore maple appears to be relatively less threatened compared to other species such as Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst), silver fir (Abies alba Mill.), European larch (Larix decidua Mill.) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.; Dyderski et al., 2025). Sycamore is a tree species that is already expanding, especially in the northeastern margin of its natural range (Konatowska et al., 2023). However, future climatic suitability for sycamore is predicted to be limited to Central Europe, with potential niche expansion primarily northwards rather than eastwards (Dyderski et al., 2025).

These range shifts in distribution are further exacerbated by human-mediated factors, including forestry practices and land-use changes, which often facilitate the spread of species like sycamore maple into non-native territories (Straigyte and Baliuckas, 2015). For example, sycamore maple grows faster in its introduced range in New Zealand than in its native range, due to greater shade tolerance and phenotypic plasticity (Shouman et al., 2017). Studies also show that central European provenances of sycamore maple perform better under GCC, and the species shows differential responses along the latitudinal gradient. This suggests that GCC will likely have heterogeneous impacts across Europe, with more pronounced effects in the northern and southern extremes of its distribution (Carón et al., 2015b). Since sycamore does not thrive in drought-prone areas (Pinto and Gégout, 2005), its range in the southern regions is expected to shift northwards as the climate becomes hotter and drier, potentially extending beyond Spain, Italy, and the Balkans (around latitude 44° N; Hemery et al., 2010).

6 Habitat and ecological preferences

Sycamore maple is a semi-shade tree species that tolerates considerable shade when young and full sunlight in mature stages. It shades the ground in forests almost as much as European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). It has higher soil fertility requirements and needs both air and soil moisture, but it does not tolerate flooding or stagnant water. It typically grows on humus-rich, moist soils with a higher rock content and scree soils enriched with nitrogen (Musil, 2005; Pasta et al., 2016). It is usually found on nutrient-rich soils, often accumulating in shady microclimates on the lower parts of slopes and ravines. It frequently occurs on calcareous substrates associated with coarse scree, cliffs, steep rocky slopes, and inaccessible ravines, where it forms scattered areas transitioning into other forest types in flat valley sections and on slopes above them, or narrow strips along stream banks (Svoboda, 1955). Sycamore maple grows successfully across a wide range of soil textures and moisture conditions, but its performance varies with soil properties. Growth is particularly vigorous on well-drained clay-rich soils and on imperfectly drained calcareous sites, whereas soils with stagnant water within 40 cm of the surface are generally unsuitable (Jensen et al., 2008). On acidic soils, where nutrient availability is mediated by subsurface water flow, sycamore maple can still form well-growing stands (Weber-Blaschke et al., 2008). In terms of stand size and productivity, the species typically achieves its best development on limestone and other base-rich substrates, but sycamore can also grow reasonably well on acidic soils. Soil pH typically ranges from 5 to 8, indicating a slight preference for moderately acidic to alkaline substrates (Musil, 2005). In calcareous areas, it typically grows on scree rich in leached humus and in sufficiently moist conditions (Svoboda, 1955).

It is a characteristic tree of higher altitudes with an oceanic climate type. Optimum growth is achieved when average annual precipitation exceeds 1,200 mm, and the annual mean air temperature is around 12 °C–13 °C. However, it is highly cold-tolerant, withstanding an absolute minimum of up to −30 °C. It also grows well with average annual precipitation ranging from 600 to 1,600 mm, but only tolerates short dry periods of less than 3 months during the growing season (Tissier et al., 2004; Pinto and Gégout, 2005; Leuschner et al., 2024). Since late-spring frosts have increased in Europe (Zohner et al., 2020) sycamore maple is affected by them due to its early spring budburst (Morecroft and Roberts, 1999). In addition, frost cracks can form in older trunks during harsh winters, similar to European beech (Úradníček et al., 2001). Therefore, it is a suitable tree species for the foothills and mountains in Central Europe, even in drier and warmer climates, where it forms primarily mixed and often highly structured stands with considerable stability and biodiversity (Vacek S. et al., 2018).

In terms of GCC, sycamore maple is more sensitive to drought than field maple (Acer campestre L.) and Norway maple (Acer platanoides L.), as well as European ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) and sessile oak (Quercus petraea [Matt.] Liebl.), representing its main competitors on many sites (Scherrer et al., 2011; Lazic et al., 2022). Given projections of more frequent summer droughts (Scherrer et al., 2011; Spinoni et al., 2017), this suggests that sycamore is likely to decline in many areas in the future (Morecroft et al., 2008; Hemery et al., 2010). On the other hand, sycamore can increase its fine root biomass during water shortages in dry periods. Although it experienced stronger radial growth depression during dry years, possibly related to its sensitive stomatal regulation, it was highly resilient and generally has shown no long-term growth decline in recent decades (Leuschner et al., 2024).

Sycamore maple rarely forms pure stands, and it most commonly occurs in mixed stands with Norway spruce, silver fir, and European beech in Central Europe. Generally, it dominates in cooler, wetter sites, where it supports a diverse ground flora and a wide range of herbivores (Binggeli, 1993; Vacek et al., 2017). The species also provides important microhabitats for specialized organisms, significantly increasing the richness of epiphytic bryophytes and lichens along gradients of tree species composition (Wierzcholska et al., 2024). In addition, aphids feeding on sycamore serve as a valuable resource for various animals, both directly as prey and indirectly through their honeydew, further enhancing the ecological complexity of these stands (Leslie, 2005). Literature on Central European forest ecosystems (Bardat et al., 2004; Berg and Dengler, 2004; Ellenberg and Leuschner, 2010; Chytrý et al., 2013), the Alpine regions (Lasen and Urbinati, 1995; Keller et al., 1998), and southern Europe, including Sicily (Košir, 2005; Biondi et al., 2008; Košir et al., 2008; Angiolini et al., 2012; Brullo et al., 2012; Mucina et al., 2016), indicates that sycamore is often a dominant species in mixed deciduous forests of the Tilio-Acerion type, covering slopes, screes, and ravines (European Commission, 2013). This type of forest belongs to the phytosociological class Querco-Fagetea Br.-Bl. & Vlieger in Vlieger 1937, where sycamore is frequently accompanied by species such as ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.), mountain elm (Ulmus glabra Huds.), and lime trees, particularly small-leaved lime (Tilia cordata Mill.), less frequently large-leaved lime (Tilia platyphyllos Scop.; Biondi et al., 2010; Chytrý et al., 2013). Sycamore maple also often colonizes abandoned meadows, pastures, buildings, walls, and stone piles on property borders, because these secondary biotopes on anthropogenic sites are ecologically similar to scree forests (Vacek et al., 2009; Kalousková and Vacek, 2016).

7 Silviculture and timber production

Sycamore maple is one of the fastest-growing valuable deciduous tree species when grown on suitable sites (Poleno et al., 2009). On rich, moist sites, it can reach a height of 19.5 m at 20 years of age (Claessens et al., 1999), while on the poorest sites, it reaches only 6.5 m (Hein et al., 2009). In addition to the site conditions, the intensity of silvicultural treatments and the choice of thinning methods have a significant impact on the dynamics of height growth (Poleno et al., 2009). Sycamore maple shows the greatest height and diameter growth around the age of 10 and maintains this growth for about 10–15 years before it slows down (Kalousková and Vacek, 2016). Compared to other tree species, it grows faster than beech at a young age, continues its rapid growth until the age of 20–30 years, and stops height growth at 80–100 years of age, while diameter growth continues, allowing it to reach large dimensions (Pagan, 1997).

In stands of suitable origin, natural regeneration dominates due to its abundant fertility (Burschel and Huss, 1997). The density and growth of natural regeneration are strongly influenced by site and stand conditions, particularly the intensity of transmitted light through the parent stand, ground vegetation cover, and damage by wildlife (Nagel et al., 2014). The fastest growth of sycamore maple occurs under full light intensity. When light availability drops below 25%, seedling growth is severely restricted (Dreyer et al., 2005; Delagrange et al., 2006). Even at a light intensity of around 5%, sycamore maple seedlings can survive for more than 15 years (Ammer, 1996; Hättenschwiler and Körner, 2000), although their height growth is very slow, usually 1–2 cm per year (Ammer, 1996), due to the low rate of photosynthesis (Kazda et al., 2004). In gaps larger than 30 m in diameter, natural regeneration tends to be denser along the edges than in the center of the gap (Ammer, 1996). Light requirements increase significantly during the sapling stage (Poleno et al., 2009).

The growth and survival of natural regeneration of sycamore maple can also be influenced by competition from ground vegetation. Especially in fresh sites, seedlings and saplings are very sensitive to competing herbaceous plants, particularly during the early establishment phase (Diaci, 2002; Modrý et al., 2004; Vandenberghe et al., 2007; Vacek et al., 2017). On the other hand, as a fast-growing species, sycamore tolerates competition from ground vegetation relatively well-compared to slow-growing species such as silver fir or yew (Taxus baccata L.), which are strongly negatively affected by dense herbaceous cover that limits seedling survival and establishment (Prokùpková et al., 2021; Bledý et al., 2025). Upon canopy opening, the herbaceous layer typically takes about 2 years to establish, and during this initial period, it does not negatively affect seed germination and early growth of seedlings (Diaci, 2002; Vandenberghe et al., 2007). Therefore, stands should be carefully thinned, i.e., only moderately reducing overstorey density to maintain partial shade, to ensure adequate seedling growth while minimizing the development of undesirable vegetation. In addition to generative natural regeneration, sycamore maple also shows a strong capacity for vegetative regeneration via coppicing, producing vigorous stump shoots that exhibit rapid early height and diameter growth (Henriksen and Bryndum, 1989; Tillisch, 2001; Musil, 2005; Poleno et al., 2009). Single-stem coppice stools can exceed 1 m of annual height increment and show markedly higher diameter growth compared with stools carrying multiple shoots (Nicolescu et al., 2013b). Single-shoot coppices outperform seed-origin trees in height growth up to approximately 12 years of age (up to age 20 for DBH), with the coppice shoots closing canopy already in the second or third year after cutting (Strimbu and Nicolescu, 2023). Group regeneration is suitable for establishing mixed stands of valuable hardwoods, including sycamore maple (Gockel et al., 2001; Harari and Brang, 2007; Saha et al., 2012; Martiník et al., 2021).

Due to its rapid growth and high timber value, there is considerable economic and silvicultural interest in sycamore maple. There are many recommendations for the cultivation of sycamore maple in Europe (Thill, 1970, 1975; Kerr and Evans, 1993; Allegrini et al., 1998; Joyce et al., 1998; Tillisch, 2001; Poleno et al., 2009; Hein et al., 2009). Most of the existing cultivation methods are based on operational experience under specific environmental conditions (Kerr and Evans, 1993; Joyce et al., 1998), only a few are based on detailed research and the synthesis of acquired knowledge (Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Hein et al., 2009; Sjöstedt, 2012; Straigyte and Baliuckas, 2015; Vacek S. et al., 2018). A thorough understanding of the dynamics and adaptability of forest ecosystems (Lindenmayer et al., 2000; European Commission, 2013) is essential, especially for the development of new management practices closely linked to GCC and increasing ecosystem services (Spiecker et al., 2004; Puettmann and Ammer, 2007; Foster et al., 2010; Barbati et al., 2014). In this way, sustainable and nature-based forest ecosystem management practices can be accurately adapted to the ongoing GCC (Kölling and Zimmermann, 2007; Hein et al., 2009; Hemery et al., 2010; Coote et al., 2012; Oxbrough et al., 2014; Carón et al., 2015a; Leuschner et al., 2024).

In the context of GCC, management is primarily focused on creating the highest possible proportion of valuable assortments in mixed, richly structured stands (Spiecker et al., 2004, 2009). To enhance forest stability and continuity, silvicultural practice should be adjusted by promoting species, structural and age diversity, selecting and releasing crop trees across canopy layers, increasing the frequency of early-stage thinning, and combining natural regeneration with assisted planting, thereby reducing vulnerability to pests, diseases, and environmental stressors while supporting sustainable stand functioning (Vacek et al., 2023). On more fertile sites, sycamore maple and other species likely to benefit from GCC, such as wild cherry (Prunus avium L.), should be integrated with European beech and oaks, fostering greater resilience and structural diversity essential for the long-term stability and production of mixed stands (Konatowska et al., 2023).

To ensure the formation of sycamore high-quality stems, dynamic, high-intensity cleaning, respacing, or thinning is recommended in young and medium-aged stands, targeting the free-growth state of future crop trees (Nicolescu et al., 2013a). In tending operations in sapling stages, negative selection is applied in the upper and middle canopy levels, where unsuitable and forked individuals are removed. There is no intervention in the understory. Thinning is carried out with positive selection, or by releasing target trees. The goal of the silvicultural programs is to achieve about 400 target individuals per hectare in sycamore maple stands (Poleno et al., 2009). In silviculture practice, this typically involves selecting 70–90 final crop trees per hectare, spaced 11–12 m apart, with an additional 140–270 potential trees identified during the thicket stage. Artificial pruning is applied to branches up to 3 cm in diameter, maintaining a green crown of at least 50% of total tree height, with the management goal of reaching 40–60 cm DBH within roughly 60 years (Nicolescu et al., 2013a). Stands should ideally have a stocking of 0.7 to minimize the risk of degradation and provide sufficient space for growth, development of valuable trees, and fertility support, with seed-bearing sycamore maple stands recommended to promote up to 40% of this species (Rebrean F. A. et al., 2019). As heartwood discoloration becomes highly probable once sycamore trees exceed approximately 45 cm DBH, the timing of rotation age should be aligned with this threshold to avoid a sharp decline in the proportion of high-value assortments (Kadunc, 2007).

Regarding timber production, most studies derive the stand stock of sycamore maple from growth tables (Hein et al., 2009), and it has a significant range depending on the site and stand conditions. For example, in Sweden, Sjöstedt (2012) reports a stock of 32–407 m3⋅ha–1, and in Denmark, (Kjølby, 1958) observed a stock of 274–766 m3⋅ha–1. Schober (1975) states that the cumulative volume production of sycamore maple in the best yield class in Germany is about 1,050 m3⋅ha–1, significantly higher than beech, which reaches only 546 m3⋅ha–1 at 80 years of age, and ash, which reaches 555 m3⋅ha–1. Lockow (2004) also states that sycamore maple at a height of 30 m exceeds the volume of ash by 180 m3⋅ha–1, while beech only exceeds sycamore maple’s volume when it exceeds 30 m in height. When comparing the stand volume of sycamore maple and beech stands in the comparable site and stand conditions in the Orlické Mountains in Czechia, they are comparable (sycamore maple 175–392 m3⋅ha–1 and beech 194–384 m3⋅ha–1; Králíček et al., 2017). On the other hand, Henriksen and Bryndum (1989), Schober (1975), Lockow (2004) report that sycamore maple on suitable sites outperforms European beech and common ash in timber production.

According to Kjølby (1958), in the best sites in Denmark, the periodic annual increment of sycamore maple stands reaches a maximum of 19.5 m3⋅ha–1, with the mean annual increment of 15 m3⋅ha–1 at the age of 27. In Bulgaria, sycamore maple stands achieved an annual increment of up to 21 m3⋅ha–1, with a stand volume of 944 m3⋅ha–1 (Iliev et al., 2022). The production potential and dendrometric parameters of sycamore maple stands from nine European countries across a wide altitudinal gradient (0–1,400 m a.s.l.) are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| References | Country | Altitude (m a.s.l.) |

Age (yr) |

DBH (cm) |

H (m) |

BA (m2⋅ha–1) | V (m3⋅ha–1) | Density (trees⋅ha–1) | MAI (m3⋅ha–1⋅yr–1) | Climate classification* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brüllhardt et al., 2020 | Switzerland | 370–860 | 24–44 | 3.3–9.5 | – | 19.8–41.0 | – | – | – | Cfb, Dfb |

| Le Goff et al., 2011 | France | – | 22–62 | 4.3–28.2 | 7.7–22.2 | 25.3–40.5 | – | 650–17,698 | – | – |

| Hájek et al., 2021 | Czechia | 590–620 | 107–121 | 39.7–41.5 | 24.8–28.1 | 42.6–45.8 | 597–640 | 340–344 | 5.3–5.6 | Dfb |

| Iliev et al., 2022 | Bulgaria | 200–1,400 | 40–70 | 20.1–34.7 | 20.0–27.5 | 23.3–98.2 | 216–944 | 566–2,966 | 4.8–21.0 | Cfb, Dfb |

| Pach et al., 2013 | Poland | 930–1,120 | – | – | – | 30.2–40.9 | 129–487 | 387–1,080 | 1.9–6.1 | Dfb |

| Plauborg, 2004 | Denmark | 0–150 | 37–44 | – | – | 35.8–46.2 | – | – | – | Cfb |

| Neirynck et al., 2000 | Belgium | 135 | 65 | – | – | 34.7 | 387 | – | 6.0 | Cfb |

| Sjöstedt, 2012 | Sweden | 35–125 | 16–53 | – | 14.0–21.0 | 8.0–66.0 | 32–407 | 240–1,460 | 2.0–11.6 | Dfb |

| Vacek S. et al., 2018 | Czechia | 595–725 | 61–83 | 29.3–35.2 | 17.9–22.8 | 33.0–48.3 | 378–571 | 376–696 | 6.1–7.4 | Dfb |

| Vacek et al., 2019 | Czechia | 430 | 61 | 25.8 | 17.5 | 37.6 | 340 | 720 | 5.6 | Cfb |

| Vospernik, 2021 | Austria | – | – | 27.0 | – | 36.0 | – | – | – | Cfb, Dfb |

Overview of 11 available publications on production parameters of sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.).

*Climate classification according to Peel et al. (2007). DBH, diameter at breast height; H, tree height; BA, basal area; V, timber volume; MAI, mean annual increment.

As with other tree species, the radial growth and natural crown development of sycamore maple depend on site and stand conditions, which are influenced by silvicultural measures (Stern, 1989; Jørgensen, 1998; Tillisch, 2001; Plauborg, 2004; Hemery et al., 2005; Hein and Spiecker, 2009; Hein et al., 2009). From this perspective, Hein (2003) compares crown width development with radial growth development in sycamore maple. Hein and Spiecker (2009) consider this relationship to be important for the management of stands, particularly during thinning applications. Kerr and Evans (1993); Hein (2003) consider a radial growth of 4–5 mm and a rotation period of 60–75 years as optimal for sycamore maple in European countries. These values are comparable with the study by Vacek S. et al. (2018) from the Czechia, where radial growth at around 60 years of age ranges from 3.0 to 6.4 mm (with an average of 4.8 mm).

8 Importance and use

Sycamore maple is commonly found on highly skeletal soils, including scree, which are prone to high levels of erosion on steep mountain slopes in Europe (Bosco et al., 2015; Leuschner and Ellenberg, 2017). Therefore, it plays an important role in soil protection. Its adventitious roots increase slope stability, thereby reducing erosion Florineth et al. (2002) and preventing rockfall (Norris et al., 2008). Sycamore maple is also frequently used in shelterbelts and windbreaks, often in mixtures with other tree species, to reduce soil erosion and protect agricultural land (Vacek Z. et al., 2018). This tree species is highly tolerant of various environmental conditions, including air pollution, exposed sites, saline winds, and low summer air temperatures. Its striking and attractive appearance also makes it a popular ornamental tree in urban and coastal areas, where it forms stable stands (Weber et al., 1993; Heitz, 2000; Úradníček et al., 2001; Musil, 2005; Praciak et al., 2013). It is also an important ameliorative tree species that increases humus formation and nutrient cycling due to its rapid decomposition (Weber et al., 1993; Heitz, 2000; Vacek S. et al., 2018). Total earthworm biomass was also significantly higher at the sites that supported sycamore as a mull-forming hardwood (Neirynck et al., 2000). Sycamore maple has spread successfully on abandoned agricultural land, creating productive stands with significant biodiversity (Kalousková and Vacek, 2016). Compared to other deciduous trees, the production potential of the sycamore maple plays an important role in carbon sequestration and GCC mitigation (Cukor et al., 2022).

In addition to these ecological functions and the aforementioned uses of its wood, sycamore maple also has several other non-wood applications. Its flowers are an important source of nectar for bees and other pollinators, supporting honey production and maintaining pollinator populations (Williams et al., 1993; Szabó et al., 2016). The nectaries of sycamore flowers produce nectar with an average sugar content of 37.3%, resulting in an estimated sugar yield of 0.65 kg per tree (Dmitruk, 2019). Young shoots and leaves from natural regeneration provide nutritionally rich food for wildlife, particularly hares and ungulates (Skoták et al., 2025). The sap is traditionally harvested in some regions for consumption or as a source of natural sweeteners. Sycamore syrup is not only valued for its flavor but also for its potential health-promoting properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects (McHugh et al., 2024). Despite the considerable economic interest in sycamore maple, the ecological services it provides, and its adaptability to a wide range of site conditions, this tree species occupies a small proportion of European forests, generally not exceeding 3% (Thies et al., 2009; Pasta et al., 2016).

9 Wood properties and price development over time

Its rapid growth and significant demand for timber make it an economically attractive tree species (Hein et al., 2009). It produces valuable and highly usable timber for the wood-processing industry (Aaron and Richards, 1990; Whiteman et al., 1991; Núńez-Regueira et al., 1997; Soulčres, 1997). The wood is soft but strong and light, with an attractive color, and is used for turning, furniture making, joinery, interior flooring, and musical instruments (Praciak et al., 2013; Savill, 2013). Wood with curly grains is particularly valued by luthiers for the construction of violins and other string instruments, as its unique three-dimensional optical effect enhances both the visual appeal and perceived quality of the finished instruments (Dinulina et al., 2023). Its wood density at 12% moisture content ranges from 0.52 to 0.80 g⋅cm–3, depending on growing conditions, moisture, and tree age, ranking among the higher values for European broadleaves. Bending strength and modulus of elasticity (MOE) range from 50–140 MPa to 6.4–18.0 GPa, respectively (Wagenführ, 2006; Ehmcke and Grosser, 2014; Sedlar et al., 2021).

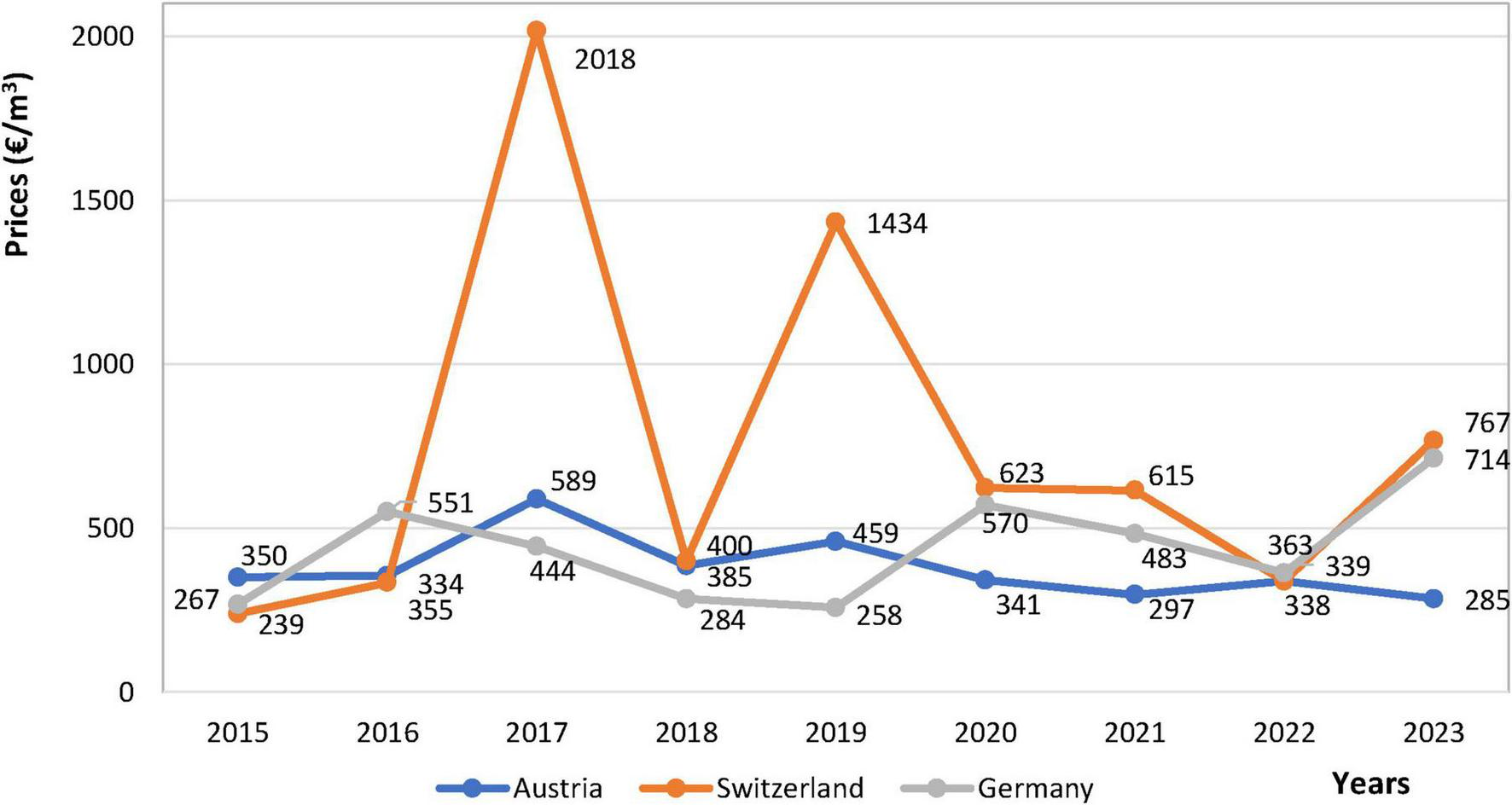

In recent years, there has been an increasing demand for high-quality wood in Europe (Becker and Klädtke, 2009). However, sycamore maple is a rarely traded tree species at auctions. The reason is probably that the benefits of this tree species are undervalued and therefore not widely distributed. And yet the economic potential is great. This is demonstrated in Figure 4, which shows the prices of sycamore timber traded at auctions in Austria, Switzerland and Germany. Figure 4 shows differences between prices (€/m3) of sycamore maple with wavy-grained and straight-grained wood (Eisold et al., 2024). According to the calculated values, the prices of sycamore with straight-grained wood show the highest average price at auction in Switzerland from 2015 to 2023, namely €752/m3, the largest range (€1779/m3) and the highest volatility given by the standard deviation σ of 561.42. On the other hand, the prices of timber in Austria reached the lowest average price of the three monitored countries, specifically €377.78/m3, the smallest range of €304/m3 and the lowest volatility given by σ of 88.53. The average price at auctions in Germany was €437.11/m3, the range of €456/m3 and σ of €148.85/m3. The lowest price for the monitored period was €239/m3 in 2015 at an auction in Switzerland, and the highest price was €2018/m3 in 2017, also in Switzerland. Prices at these auctions do not have a significant upward or downward trend over time (Figure 4). In the last monitored year (2023), prices for sycamore maple timber with straight-grained wood reached €285/m3 in Austria, €767/m3 in Switzerland and €714/m3 in Germany.

FIGURE 4

Prices (€/m3) for timber of sycamore maple with straight-grained wood achieved on auctions in Germany, Switzerland and Austria (Eisold et al., 2024).

Financially appealing are the prices of the already mentioned sycamore maple with wavy grain, traded at auctions in Germany and Switzerland for many times higher prices than straight grain. The data provided in the article (Eisold et al., 2024) from 1997 to 2023 show a minimum price of €1921/m3 in 1999 at one of the German commodity auctions (Kempten – BY) and a maximum price of €25835/m3 at one of the Swiss auctions (Kaltbrunn – SG) in 2017. The data coming from the German and Swiss commodity auctions together show an average price of €10647.44/m3, a range of €23914/m3 and a σ of 5932.1. Therefore, the price is several dozen times the value of sycamore maple with straight grain. However, the occurrence of wavy grain in the sycamore maple population is estimated to be only 3%–7% (Kúdela and Kunštár, 2011; Sopushynskyy and Teischinger, 2013), and recognition that it is a rarer type of sycamore maple occurs only after it is felled.

10 Threats and diseases

Sycamore maple is prone to cracking and peeling of the bark due to frost or sun exposure, creating entry points for phytopathogenic fungi. These fungi can cause local necrosis or spread to the cambium and wood. Persistent necroses block conductive tissues, increasing the risk of breakage. Complete tree death occurs with pathogens such as Phytophthora species (Ginetti et al., 2014; Tkaczyk et al., 2021) and especially Cryptostroma corticale (Kowalski and Materniak, 2007; Ginetti et al., 2012; Lorenc, 2024) which is likely to increase under GCC and causes “cancer disease” in sycamore (Gregory and Redfern, 1998). It is usually fatal, with outbreaks triggered by high summer air temperatures and long-term drought. Therefore, the expected GCC will likely increase the occurrence of this disease in the southern, more continental, and lower parts of its range (Hemery et al., 2010).

Sycamore maple and other Acer species in Central Europe have also been affected in recent years by the fungus Eutypella parasitica, which causes cancerous growths on the trunks and main branches of host plants (Lachance, 1971; Gross, 1984; Jurc et al., 2006; Cech, 2007; Cech et al., 2016; Dubach et al., 2022). Tumors typically form on trunks up to 6 m in height, significantly reducing the quality of their production. Several other bark diseases are caused by fungi such as Nectria cinabarina, Verticillium dahliae, and Verticillium alboatrum (Pasta et al., 2016; Brglez et al., 2024) Sycamore maple leaves are also frequently damaged by fungi such as Rhytisma acerinum, the most common disease of this tree species (Wulf, 1988, 1994; Lorenc, 2024), Pleuroceras pseudoplatani (Butin and Wulf, 1987; Cleary et al., 2018), and Petrakia echinata (Kirisits, 2007; Kehr and Butin, 2008), Cristulariella depraedans (Lang, 2000; Pasta et al., 2016), rarely by Venturia sp. (Schlegel et al., 2018), or by Prosthecium pyrimforme as an associated pathogen (Voglmayr and Jaklitsch, 2008), especially on its deadwood (Lorenc, 2024).

The most important insect pests include (i) Aphididae, such as Drepanosiphum platanoidis or Peryphyllus testudinaceus, which have been identified mainly on sycamore maples growing in urban (Senior et al., 2020; Barczak et al., 2021), (ii) Eriophyidae such as Aceria macrorhyncha, which does not cause mortality but deform the leaves (Lorenc, 2024), thus indirectly affecting the photosynthetic and thus productive capacity of trees, and (iii) Geometridae such as Ennomos subsignaria, whose larvae elucidate defoliation of trees, especially within the municipality (Fry et al., 2008).

In the UK, Ireland, and Italy, sycamore bark is locally damaged by gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) (Bertolino and Genovesi, 2003; Lawton, 2003; Mayle et al., 2003; Mountford, 2006; Signorile and Evans, 2007). According to Rayden and Savill (2004), sycamore is one of the most susceptible broadleaf species to this type of damage, especially for trees up to 30 cm in diameter at breast height. Concerning GCC, the damage caused by gray squirrels in the UK may be increasing due to reduced winter mortality and increased seed availability (Broadmeadow and Ray, 2005; Hemery et al., 2010). However, the greatest damage to sycamore stands is caused by ungulates, whose populations are increasing exponentially due to changing environmental conditions. Browsing significantly reduces height growth and can lead to the loss of regeneration (Burschel et al., 1985; Modrý et al., 2004; Vacek S. et al., 2018). In the context of the GCC, the aforementioned problems associated with prolonged drought should also be emphasized. High air temperatures can cause thermal stress, which affects the growth and development of trees, especially young individuals. Prolonged drought and water scarcity can lead to a decline in vitality and increased susceptibility to disease and pests (Hemery et al., 2010; Leuschner et al., 2024).

11 Conclusion

Sycamore maple is a key tree species in the mixed forests of mountainous and foothill regions of Europe, providing important ecological, environmental, and production functions. Although its wood production and carbon sequestration are very high, its ability to adapt to different habitat conditions and the ecological stability of these stands are also considerable. The importance of sycamore stands lies in their positive effect on biodiversity, water regulation in the landscape and protection against soil erosion, especially in inaccessible and erosion-prone areas, such as mountain slopes and screes. Sycamore maple is currently facing challenges related to GCC in many areas of Europe. The expected rise in air temperatures, increased frequency of droughts, and extreme weather events may affect its growing conditions, requiring adaptation of forest management practices. Although sycamore is relatively resistant to cold, high air temperatures and prolonged droughts can weaken its vitality and promote the spread of pathogens, especially in the southern part of its range. Given the growing economic interest in high-quality sycamore wood and its potential for ecological services, it is essential to focus on the optimal management of these stands. This includes silviculture of mixed stands, genetically and structurally differentiated stands, and wildlife management, which is currently the main limiting factor for the regeneration and sustainability of sycamore stands. A comprehensive approach is needed that takes into account GCC, ecological demands, and innovative silvicultural practices to ensure the long-term stability and productivity of these forest communities. A key element in the successful management of sycamore stands is the integration of environmental, production, and climatic aspects into silvicultural practice, which will not only support ecological stability but also enhance biodiversity and mitigate the impact of GCC on the landscape.

Statements

Author contributions

ZV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision. SV: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. JČ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. JC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. MK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JG: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. VT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. IŠ: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. IK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This research was funded by the National Agency of Agricultural Research of the Czech Republic (Project No. QL25020059), the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences (Excellent Team 2025), and the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic, institutional support MZE-RO0123.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Josef Macek for preparing the original artwork used in Figure 1 as an external graphic designer.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Aaron J. Richards E. (1990). British woodland produce.London: Stobart Davies.

2

Allegrini C. Boistot-Paillard R. Bouvet J. Bachelet D. McDowell N. Vennetier M. et al (1998). Les feullius précieux en Franche-Comté [Precious hardwoods in Franche-Comté].Besançon: Société Forestičre de Franche-Comté. French.

3

Allen C. Macalady A. Chenchouni H. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests.For. Ecol. Manage.259660–684. 10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001

4

Ambrazevicius V. (2016). Natural regeneration of Sycamore maple in southern Sweden and Lithuania.Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

5

Ammer C. (1996). Konkurrenz um Licht-zur Entwicklung der Naturverjuengung im Bergmischwald [Competition for light – on the development of natural regeneration in mixed mountain forests.Germany: Forstliche Forschungsberichte Muenchen. German.

6

Angiolini C. Foggi B. Viciani D. (2012). Acer-Fraxinus dominated woods of the Italian peninsula: A floristic and phytogeographical analysis.Acta Soc. Botanicorum Poloniae81123–130. 10.5586/asbp.2011.037

7

Barbati A. Marchetti M. Chirici G. Corona P. (2014). European Forest Types and Forest Europe SFM indicators: Tools for monitoring progress on forest biodiversity conservation.For. Ecol. Manage.321145–157. 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.07.004

8

Barczak T. Bennewicz J. Korczyński M. Błażejewicz-Zawadzińska M. Piekarska-Boniecka H. (2021). Aphid assemblages associated with urban park plant communities.Insects12:173. 10.3390/insects12020173

9

Bardat J. Bioret F. Botineau M. (2004). Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris [National Museum of Natural History, Paris].Patrimoines Naturels61:180. French.

10

Becker G. Klädtke J. (2009). Wood properties and wood processing of valuable broadleaved trees demonstrated with common ash and maple in southwest Germany.Leiden: Brill.

11

Bell S. (2009). Valuable broadleaved trees in the landscape.Valuable Broadleaved For. Europe22171–200.

12

Belletti P. Monteleone I. Ferrazzini D. (2007). Genetic variability at allozyme markers in sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus). populations from northwestern Italy.Can. J. For. Res.37395–403. 10.1139/X06-242

13

Berg C. Dengler J. (2004). Von der datenbank zur regionalmonografie–erfahrungen aus dem projekt die pflanzengesellschaften mecklenburg-vorpommerns und ihre gefährdung [from database to regional monograph – experiences from the project “The plant communities of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and their endangerment”].Berichte der Reinhold-Tuxen-Gesellschaft1629–56. German.

14

Bertolino S. Genovesi P. (2003). Spread and attempted eradication of the grey squirrel. (Sciurus carolinensis). in Italy, and consequences for the red squirrel. (Sciurus vulgaris). in Eurasia.Biol Conserv.109351–358. 10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00161-1

15

Bi W. Gao Y. Shen J. He C. Liu H. Peng Y. et al (2016). Traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of the genus Acer. (maple): A review.J. Ethnopharmacol.18931–60. 10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.021

16

Binggeli P. (1993). The conservation value of sycamore.Quart. J. For.87143–146.

17

Biondi E. Blasi C. Burrascano S. (2010). Manuale Italiano di interpretazione degli habitat. (Direttiva 92/43 CEE) [Italian Habitat Interpretation Manual. (Directive 92/43 EEC)]. Rome: Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare.Italian.

18

Biondi E. Casavecchia S. Biscotti N. (2008). Forest biodiversity of the Gargano Peninsula and a critical revision of the syntaxonomy of the mesophilous woods of southern Italy.Fitosociologia4593–127. 10.59269/zlv/2025/1/753

19

Bledý M. Vacek S. Vacek Z. Černý J. Cukor J. Kuběnka M. et al (2025). European yew. (Taxus baccata L.). and its importance in close-to-nature management under climate change conditions – review.Zprávy lesnického vızkumu7033–44.

20

Bosco C. de Rigo D. Dewitte O. Poesen J. Panagas P. (2015). Modelling soil erosion at European scale: Towards harmonization and reproducibility.Natural Hazards Earth Syst. Sci.15225–245. 10.5194/nhess-15-225-2015

21

Brglez A. Devetak Z. Ogris N. Radisek S. Piskur B. (2024). An outbreak of Verticillium dahliae on sycamore maple in a forest stand in Slovenia.J. Plant Pathol.106609–621. 10.1007/s42161-024-01597-0

22

Broadmeadow M. Ray D. (2005). Climate change and British woodland, 69th Edn. Edinburgh: Forestry Commission.

23

Brüllhardt M. Rotach P. Bigler C. Notzli M. Bugmann H. (2020). Growth and resource allocation of juvenile European beech and sycamore maple along light availability gradients in uneven-aged forests.For. Ecol. Manage.474:118314. 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118314

24

Brullo C. Brullo S. Del Galdo G. Guarino R. (2012). The class Querco-Fagetea sylvaticae in Sicily: An example of boreo-temperate vegetation in the central Mediterranean region.Annali di Botanica219–38. 10.4462/annbotrm-9342

25

Burschel P. Huss J. (1997). Lehrbuch des waldbaus: ein leitfaden für studium und praxis [Textbook of silviculture: a guide for study and practice].Berlin: Parley Verlag.

26

Burschel P. el Kateb H. Huss J. Mosandl R. (1985). Die Verjüngung im Bergmischwald [Regeneration in the mixed mountain forest].Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt10465–100. German. 10.1007/BF02740705

27

Butin H. Wulf A. (1987). Asteroma pseudoplatani sp. nov., anamorph of Pleuroceras pseudoplatani. (v. Tubeuf).Monod. Syndowia4038–41.

28

Carón M. De Frenne P. Chabrerie O. (2015b). Impacts of warming and changes in precipitation frequency on the regeneration of two Acer species.Flora – Morphol. Distribution Funct. Ecol. Plants21424–33. 10.1016/j.flora.2015.05.005

29

Carón M. De Frenne P. Brunet J. Chabreie O. Cousins S. Decocq G. et al (2015a). Divergent regeneration responses of two closely related tree species to direct abiotic and indirect biotic effects of climate change.For. Ecol. Manage.34221–29. 10.1016/j.foreco.2015.01.003

30

Cech T. (2007). First record of Eutypella parasitica in Austria.Forstschutz Aktuell10–13.

31

Cech T. Schwanda K. Klosterhuber M. Straber L. Kirsits T. (2016). Eutypella canker of maple: first report from Germany and situation in Austria.For Pathol46336–340. 10.1111/efp.12268

32

Chrzanowska E. Denisow B. Strzałkowska-Abramek M. Dmitruk M. Winiarczyk K. Bożek M. (2024). Nectar and pollen in Acer trees can contribute to improvement of food resources for pollinators.Scientific Rep.14:27705. 10.1038/s41598-024-78355-w

33

Chytrý M. Douda J. Roleček J. (2013). Vegetace České republiky 4. Lesní a køovinná vegetace [Vegetation of the Czech Republic 4. Forest and shrub vegetation].Academia: Praha. Czech.

34

Claessens H. Pauwels D. Thibaut A. Rondeux J. (1999). Site index curves and autecology of ash, sycamore and cherry in Wallonia (Southern Belgium). Forestry72, 171–182. 10.1093/forestry/72.3.171

35

Cleary M. Oskay F. Rönnberg J. Woodward S. (2018). First report of Pleuroceras pseudoplatani on Acer rubrum, A. griseum, A. saccharinum, A. negundo, A. circinatum and A. macrophyllum in Scotland.For. Chronicle94147–150. 10.5558/tfc2018-022

36

Coote L. French L. Moore K. Mitchell F. Kelly D. (2012). Can plantation forests support plant species and communities of semi-natural woodland?For Ecol Manage28386–95. 10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.013

37

Cukor J. Vacek Z. Vacek S. Linda R. Podrazsky V. (2022). Biomass productivity, forest stability, carbon balance, and soil transformation of agricultural land afforestation: A case study of suitability of native tree species in the submontane zone in Czechia.Catena210:105893. 10.1016/j.catena.2021.105893

38

Delagrange S. Montpied P. Dreyer E. Messier C. Sinoquet H. (2006). Does shade improve light interception efficiency? A comparison among seedlings from shade-tolerant and intolerant temperate deciduous tree species.New Phytol.172293–304. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01814.x

39

Diaci J. (2002). Regeneration dynamics in a Norway spruce plantation on a silver fir-beech forest site in the Slovenian Alps.For Ecol Manage16127–38. 10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00492-3

40

Dinulina F. Savin A. Stanciu M. (2023). Physical and acoustical properties of wavy grain sycamore maple. (Acer psedoplatanus L.). used for musical instruments.Forests14:197. 10.3390/f14020197

41

Dmitruk M. (2019). Flowering, nectar secretion, and structure of the nectary in the flowers of Acer pseudoplatanus L.Acta Agrobotanica72:1787. 10.5586/aa.1787

42

Dreyer E. Collet C. Montpied P. Sinoquet H. (2005). Characterisation of beech seedling tolerance to shade-comparison with associated species.Revue Forestičre Française57175–188. 10.1007/s00468-020-02011-9

43

Dubach V. Queloz V. Beenken L. (2022). First record of Eutypella parasitica on Acer in Switzerland.New Dis Rep45:e12074. 10.1002/ndr2.12074

44

Dyderski M. Paź S. Frelich L. Jagodziński A. (2018). How much does climate change threaten European forest tree species distributions?Glob. Chang Biol.241150–1163. 10.1111/gcb.13925

45

Dyderski M. Paź-Dyderska S. Jagodziński A. Puchałka R. (2025). Shifts in native tree species distributions in Europe under climate change.J. Environ. Manage.373:123504. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.123504

46

Ehmcke G. Grosser D. (2014). Das Holz der Eiche–Eigenschaften und Verwendung [Oak wood – properties and uses].LWF Wissen7553–64. German.

47

Eisold A. Bäucker C. Schneck V. (2024). “Tissue culture as proper tool for forest tree breeding–A case study with wood of value,” in Book of Proceedings, edsFrostF.TeohK.St-HilaireF.DenmanA.LeducC.MuñozM.RipaD. (Granada: EAOHP), 68.

48

El Kateb H. (1992). “Waldbau und Verjüngung im Gebirgswald. Tagungsbericht “Forstbewirtschaftung an der oberen Waldgrenze” Kouty nad Desnou-Jeseníky [Silviculture and regeneration in mountain forests,” in In Conference report “Forest management at the upper tree line” Kouty nad Desnou-Jeseníky], (Albena), 45–74. German.

49

Ellenberg H. (1996). Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen: in ökologischer, dynamischer und historischer Sicht [Vegetation of Central Europe including the Alps: from an ecological, dynamic and historical perspective].Stuttgart: Ulmer. German.

50

Ellenberg H. Leuschner C. (2010). Vegetation Mitteleuropas mit den Alpen. 6. Aufl [Vegetation of Central Europe including the Alps, 6th. Edn, Vol. 1357, Stuttgart: Eugen Ulmer. German.

51

European Commission. (2013). A new EU forest strategy: for forests and the forest-based sector.Brussels: European Commission.

52

Florineth F. Rauch H. Staffler H. (2002). “Stabilization of landslides with bio-engineering measures in South Tyrol/Italy and Thankot/Nepa,” in In Proceedings of the International Congress INTERPRAEVENT 2002 in the Pacific Rim, (Matsumoto).

53

Foster D. Kittredge D. Lambert K. (2010). Wildlands and woodlands: a vision for the New England landscape.Petersham, MA: Harvard Forest, Harvard University.

54

Fry H. Ryall K. Dixon P. Quiring D. (2008). Suppression of Ennomos subsignaria. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). on Acer pseudoplatanus. (Aceraceae). in an Urban Forest with Bole-Implanted Acephate.J. Econ. Entomol.101822–828. 10.1093/jee/101.3.822

55

Gelderen D. van Jong P. Oterdoom H. (1994). Maples of the world.Portland: Timber Press.

56

Ginetti B. Moricca S. Ragazzi A. Jung T. (2012). “Phytophthora acerina sp. nov., a new species from the P. citricola complex causing aerial cankers on Acer pseudoplatanus in Italy,” in Phytophthoras in Forests and Natural Ecosystems, edsJungT.BrasierM. C.SánchezE. M.Peréz-SierraA. (Cordoba: CiteSeerx), 29.

57

Ginetti B. Moricca S. Squires J. Ragazzi A. Jung T. (2014). Phytophthora acerina sp. nov., a new species causing bleeding cankers and dieback of Acer pseudoplatanus trees in planted forests in northern Italy.Plant Pathol63858–876. 10.1111/ppa.12153

58

Gockel H. Rock J. Schulte A. (2001). Aufforsten mit Eichen-Trupppflanzungen [Reforestation with group plantings of oak trees].AFZ/der Wald5223–226. German.

59

Gregory S. Redfern D. (1998). Diseases and disorders of forest trees: A guide to identifying causes of ill-health in woods and plantations.London: HMSO Publications Centre.

60

Grimm G. Denk T. Hemleben V. (2007). Evolutionary history and systematics of Acer section Acer – A case study of low-level phylogenetics.Plant Syst. Evol.267215–253. 10.1007/s00606-007-0572-8

61

Gross H. (1984). Defect Associated with Eutypella Canker of Maple.For. Chronicle6015–17. 10.5558/tfc60015-1

62

Hájek V. Vacek S. Vacek Z. Cukor J. Simunek V. Simkova M. et al (2021). Effect of climate change on the growth of endangered scree forests in Krkonoše National Park. (Czech Republic).Forests12:1127. 10.3390/f12081127

63

Hamrick J. (2004). Response of forest trees to global environmental changes.For. Ecol Manage.197323–335. 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.05.023

64

Hanewinkel M. Cullmann D. Schelhaas M. Nabuurs G. Zimmermann N. (2013). Climate change may cause severe loss in the economic value of European forest land.Nat Clim Chang3203–207. 10.1038/nclimate1687

65

Harari O. Brang P. (2007). Trupppflanzungs-Experimente mit Stieleiche und Bergahorn in der Schweiz. Ergebnisse der Erhebungen [Group planting experiments with pedunculate oak and sycamore maple in Switzerland. Results of the surveys.].Birmensdorf: Eidg. Forschungsanstalt für Wald, Schnee und Landschaft (WSL).German.

66

Hättenschwiler S. Körner C. (2000). Tree seedling responses to in situ CO2-enrichment differ among species and depend on understorey light availability.Glob. Chang Biol.6213–226. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00301.x

67

Hegi G. (1925). Illustrierte Flora von Mittel-Europa: Dicotyledones:(Tl. 5); Sympetalae. (Schluss d. Compositae)/Von Gustav Hegi. Mitarb.: Herbert Beger [ua]. Volkstüml. Pflanzennamen ges. u. bearb [Illustrated Flora of Central Europe: Dicotyledones (Part 5); Sympetalae (End of the Compositae) / By Gustav Hegi. Contributors: Herbert Beger [et al.]. Collected and edited common plant names.]. von Heinrich Marzell.München: JF Lehmann. German.

68

Hein S. (2003). Zur Steuerung von Astreinigung und Dickenwachstum bei Esche. (Fraxinus excelsior L.). und Bergahorn. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) [On the control of branch shearing and diameter growth in ash (Fraxinus excelsior L.) and sycamore maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.)].Freiburg: Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg. German.

69

Hein S. Spiecker H. (2009). “Controlling diameter growth of common ash, sycamore and wild cherry,” in Valuable Broadleaved Forests in Europe, edsSpieckerH.HeinS.Makkonen-SpieckerK.ThiesM. (Joensuu: European Forest Institute), 103–122.

70

Hein S. Collet C. Ammer C. Goff N. (2009). A review of growth and stand dynamics of Acer pseudoplatanus L. in Europe: implications for silviculture.For. Int. J. For. Res.82361–385. 10.1093/forestry/cpn043

71

Heitz R. (2000). Reconversion of Norway spruce. (Picea abies. (L.). Karst.). stands into mixed forests: effects on soil properties and nutrient fluxes.Wien: Institute of Forest Growth Research, 119–125.

72

Hemery G. Clark J. Aldinger E. (2010). Growing scattered broadleaved tree species in Europe in a changing climate: A review of risks and opportunities.For. Int. J. For. Res.8365–81. 10.1093/forestry/cpp034

73

Hemery G. Savill P. Pryor S. (2005). Applications of the crown diameter–stem diameter relationship for different species of broadleaved trees.For. Ecol. Manage.215285–294. 10.1016/j.foreco.2005.05.016

74

Henriksen H. A. Bryndum H. (1989). Zur Durchforstung von Bergahorn und Buche in Dänemark. AFZ Allgemeine Forst Zeitschrift für Waldwirtschaft und Umweltvorsorge44:1043.

75

Hérault B. Thoen D. Honnay O. (2004). Assessing the potential of natural woody species regeneration for the conversion of Norway spruce plantations on alluvial soils.Ann. For. Sci.61711–719. 10.1051/forest:2004057

76

Hills N. Hose G. Canthlay A. Murray B. (2008). Cave invertebrate assemblages differ between native and exotic leaf litter.Austral. Ecol.33271–277. 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01814.x

77

Humphries C. Press J. Sutton D. (1992). The Hamlyn guide to trees of Britain and Europe.London: Hamlyn.

78

Iliev N. Varbeva L. Tonchev T. Alexandrov N. (2022). Growth and productivity of sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) in natural stands and forest plantations in Bulgaria.For. Ideas28, 178–193.

79

Jensen J. Rasmussen L. Raulund-Rasmussen K. Borggaard O. (2008). Influence of soil properties on the growth of sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). in Denmark.Eur. J. For. Res.127263–274. 10.1007/s10342-008-0202-1

80

Jones E. (1945). Biological flora of the British Isles, Acer L.J. Ecol.32215–219. 10.2307/2256711

81

Jørgensen B. (1998). Dyrkningserfaringer for ær baseret på langsigtede forsøg [Cultivation experiences for peas based on long-term trials].Skoven265–69. Danish.

82

Joyce P. Huss J. McCarthy R. (1998). Growing broadleaves: silvicultural guidelines for ash, sycamore, wild cherry, beech and oak in Ireland.Dublin: National Council for Forest Research and Development. (COFORD).

83

Jurc D. Ogris N. Slippers B. Stenlid J. (2006). First report of eutypella canker of Acer pseudoplatanus in Europe.Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

84

Kadunc A. (2007). Factors influencing the formation of heartwood discolouration in sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.).Eur. J. For. Res.126349–358. 10.1007/s10342-006-0151-5

85

Kalousková I. Vacek S. (2016). “Succession of the Sycamore maple on former pastures in the Orlické hory Mts., Czech Republic,” in Rolnictwo XXI wieku–problemy i wyzwania. Idea Knowledge Future, ed. D. Łuczycka (Berlin: Springer), 84–95.

86

Kazda M. Salzer J. Schmid I. Von Wrangell Ph. (2004). Importance of mineral nutrition for photosynthesis and growth of Quercus petraea, Fagus sylvatica and Acer pseudoplatanus planted under Norway spruce canopy.Plant Soil26425–34. 10.1023/B:PLSO.0000047715.95176.63

87

Keenan R. (2015). Climate change impacts and adaptation in forest management: A review.Ann. For. Sci.72145–167. 10.1007/s13595-014-0446-5

88

Kehr R. Butin H. (2008). Deutsche Pflanzenschutztagung in Kiel: 22-25 September, Mitteilungen aus dem Julius Kuhn-Institut 417 [German Plant Protection Conference in Kiel: 22-25 September, Communications from the Julius Kuhn Institute 417].Quedlinburg: Julius Kuhn-Institut. German.

89

Keller W. Wohlgemuth T. Kuhn N. (1998). Waldgesellschaften der Schweiz auf floristischer Grundlage [Forest communities of Switzerland based on floristic principles].Mitt Eidgenöss Forsch.anst Wald Schnee Landsch7393–357. German.

90

Kerr G. Evans J. (1993). Growing broadleaves for timber. Forestry Commission handbook 9.London: H.M.S.O, 95.

91

Kirisits T. (2007). Die Petrakia-Blattbräune des Bergahorns [Petrakia leaf blight of the sycamore maple.Forstschutz Aktuell.4028–31. German.

92

Kjølby V. (1958). Ær Naturhistorie, tilvækst og hugst: Ær. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.) [Maple Natural history, growth and harvesting: Maple (Acer pseudoplatanus L.)].Denmark: Dansk Skovforening, 5–126. Danish.

93

Kölling C. Zimmermann L. (2007). Die anfälligkeit der wälder deutschlands gegenüber dem klimawandel [The vulnerability of Germany’s forests to climate change].Gefahrstoffe-Reinhaltung der Luft67259–268. German.

94

Konatowska M. Młynarczyk A. Kowalewski W. Rutkowski P. (2023). NDVI as a potential tool for forecasting changes in geographical range of sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.).Sci. Rep.13:19818. 10.1038/s41598-023-46301-x

95

Košir P. (2005). Maple forests of the montane belt in the western part of the Illyrian floral province.Hacquetia437–82.

96

Košir P. Ccaronarni A. Di Pietro R. (2008). Classification and phytogeographical differentiation of broad-leaved ravine forests in southeastern Europe.J. Veg. Sci.19331–342. 10.3170/2008-8-18372

97

Kowalski T. Materniak P. (2007). Disease symptoms and their frequency of occurrence in sycamores [Acer pseudoplatanus L.] in the Rymanow Forest Unit stands.Acta Agrobot.60123–133.

98

Krabel D. Wolf H. (2013). “Sycamore Maple. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.),” in Forest Tree Breeding in Europe: Current State-of-the-Art and Perspectives, ed.PâquesL. (Springer: Dordrecht), 373–402.

99

Králíček I. Vacek Z. Vacek S. (2017). Dynamics and structure of mountain autochthonous spruce-beech forests: Impact of hilltop phenomenon, air pollutants and climate.Dendrobiology77119–137. 10.12657/denbio.077.010

100

Kúdela J. Kunštár M. (2011). Physical-acoustical characteristics of maple wood with wavy structure. Ann. Warsaw Univ. Life Sci. SGGW For. Wood Technol. 75, 12–18.

101

Kupferschmid A. Bugmann H. (2008). Ungulate browsing in winter reduces the growth of Fraxinus and Acer saplings in subsequent unbrowsed years.Plant Ecol.198121–134. 10.1007/s11258-007-9390-x

102

Lachance D. (1971). Discharge and germination of Eutypella parasitica ascospores.Can. J. Bot.491111–1118. 10.1139/b71-160

103

Lang K. (2000). New hosts of Cristulariella depraedans.For Pathol.30117–120. 10.1046/j.1439-0329.2000.00193.x

104

Lasen C. Urbinati C. (1995). Typology and ecology of maple-linden and maple-ash forest communities: preliminary consideration in north-eastern Italian prealpine ranges.Sauteria621–56.

105

Lawton C. (2003). Controlling grey squirrel damage in Irish broadleaved woodlands.Dublin: COFORD – Council for Forestry Research and Development.

106

Lazic D. George J. Rusanen M. (2022). Population differentiation in Acer platanoides L. at the regional scale—laying the basis for effective conservation of its genetic resources in Austria.Forests13:552. 10.3390/f13040552

107

Le Goff N. Ottorini J. Ningre F. (2011). Evaluation and comparison of size–density relationships for pure even-aged stands of ash. (Fraxinus excelsior L.), beech. (Fagus silvatica L.), oak. (Quercus petraea Liebl.), and sycamore maple. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.).Ann. For. Sci.68461–475. 10.1007/s13595-011-0052-8

108

Leslie A. (2005). The ecology and biodiversity value of sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L). with particular reference to Great Britain.Scottish For.5919–26.

109

Leuschner C. Ellenberg H. (2017). Vegetation ecology of central Europe.Berlin: Springer.

110

Leuschner C. Fuchs S. Wedde P. (2024). A multi-criteria drought resistance assessment of temperate Acer, Carpinus, Fraxinus, Quercus, and Tilia species.Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst.62:125777. 10.1016/j.ppees.2023.125777

111

Lichstein J. Grau H. Aragón R. (2004). Recruitment limitation in secondary forests dominated by an exotic tree.J. Veg. Sci.15721–728. 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2004.tb02314.x

112

Lindenmayer D. B. Margules C. R. Botkin D. B. (2000). Indicators of biodiversity for ecologically sustainable forest management. Conserv. Biol. 14, 941–950. 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2000.98533.x

113

Lockow K. (2004). Die erste ertragstafel für bergahorn im nordostdeutschen tiefland. Beiträge für Forstwirtschaft und Landschaftsökologie [The first yield table for sycamore maple in the Northeast German Plain. Contributions to forestry and landscape ecology].Hamburg: Paul Parey. German.

114

Lorenc F. (2024). Cryptostroma corticale and its relationship to other pathogens and pests on Acer pseudoplatanus.J. For. Sci.70610–618. 10.17221/41/2024-JFS

115

Luo Z. Zhang Z. Zhang R. Pandey M. Gailing O. Hattemer H. et al (2006). Modeling population genetic data in autotetraploid species.Genetics172639–646. 10.1534/genetics.105.044974

116

Martiník A. Sendecký M. Březina D. (2021). První poznatky ze skupinové obnovy javoru klenu. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). v oblasti rozpadu nepùvodních jehličnatıch porostù.Rep. For. Res.6628–35.

117

Mauer O. Pop M. Palátová E. (2007). Root system development and health condition of sycamore maple. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). in the air-polluted region of Krušné hory Mts.J For Sci.53452–461. 10.17221/2086-JFS

118

Mayle B. Pepper H. Ferryman M. (2003). Controlling grey squirrel damage to woodlands.Edinburgh, UK: Forestry Commission. 1–16.

119

McHugh O. Ayilaran E. DeBastiani A. Jung Y. (2024). Physicochemical and functional properties of black walnut and sycamore syrups.Foods13:2780. 10.3390/foods13172780

120

Meusel H. Jäger E. (1998). Vergleichende Chorologie der Zentraleuropäischen Flora-Band I, II, III [Comparative Chorology of the Central European Flora - Volumes I, II, III].Germany: Gustav Fischer Verlag. German.

121

Mitchell A. (1974). A field guide to the trees of Britain and northern Europe.Charlotte, NC: Collins.

122

Modrý M. Hubenı D. Rejšek K. (2004). Differential response of naturally regenerated European shade tolerant tree species to soil type and light availability.For. Ecol. Manage.188185–195. 10.1016/j.foreco.2003.07.029

123

Monumental Trees (2025). Sycamore Maple (Acer pseudoplatanus). Available online at: https://www.monumentaltrees.com/en/trees/acerpseudoplatanus/(accessed February 27, 2025).

124

Morecroft M. Roberts J. (1999). Photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of mature canopy Oak. (Quercus robur). and Sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus). trees throughout the growing season.Funct. Ecol.13332–342. 10.1046/j.1365-2435.1999.00327.x

125

Morecroft M. Stokes V. Taylor M. Morison J. (2008). Effects of climate and management history on the distribution and growth of sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). in a southern British woodland in comparison to native competitors.For. Int. J. For. Res.8159–74. 10.1093/forestry/cpm045

126

Mountford E. (2006). Long-term patterns and impacts of grey squirrel debarking in Lady Park Wood young-growth stands. (UK).For. Ecol. Manage.232100–113. 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.05.053

127

Mucina L. Bültmann H. Dierßen K. (2016). Vegetation of Europe: hierarchical floristic classification system of vascular plant, bryophyte, lichen, and algal communities.Appl. Veg. Sci.193–264. 10.1111/avsc.12257

128

Musil I. (2005). Listnaté døeviny [Deciduous trees].Praha: Česká zemìdìlská univerzita v Praze. Czech.

129

Nagel T. Diaci J. Jerina K. (2014). Simultaneous influence of canopy decline and deer herbivory on regeneration in a conifer–broadleaf forest.Can. J. For. Res.45266–275. 10.1139/cjfr-2014-0249

130

Neirynck J. Mirtcheva S. Sioen G. Lust N. (2000). Impact of Tilia platyphyllos Scop., Fraxinus excelsior L., Acer pseudoplatanus L., Quercus robur L. and Fagus sylvatica L. on earthworm biomass and physico-chemical properties of a loamy topsoil.For. Ecol. Manage.133275–286. 10.1016/S0378-1127(99)00240-6

131

Neophytou C. Konnert M. Fussi B. (2019). Western and eastern post-glacial migration pathways shape the genetic structure of sycamore maple. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). in Germany.For. Ecol. Manage.43283–93. 10.1016/j.foreco.2018.09.016

132

Nicolescu V. N. Capraru E. Ciubotaru G. Şimon D. C. (2013a). Sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). silviculture, between “classical” and “dynamic”.Rev. Pãdurilor23–10.

133

Nicolescu V. N. Sandi M. Pricop A. Cristea N. (2013b). The biometrical influences of stump stocking on sycamore. (Acer pseudoplatanus L.). coppice trees: A case study.Revista pãdurilor33–13.

134