Abstract

Hydraulic redistribution (HR) by deep-rooting trees can provide water from deeper soil layers to shallow-rooted understory plants, yet species-specific and temporal patterns of HR water uptake remain poorly understood. We investigated whether HR water from mature oaks (Quercus robur L./Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) is preferentially taken up by oak seedlings compared to co-occurring understory species, and how HR water use varies over the course of the day. During drought periods in mature oak stands in Germany, two field experiments were conducted. In a deep-soil 2H-labeling experiment of mature oak trees, HR water was detected in the roots of three different understory plants. Six days after labeling, HR water amounted to 16 ± 8% (oak), 13 ± 7% (black cherry, Prunus serotina Ehrh.), and 8 ± 4% (small balsam, Impatiens parviflora DC.) of total root water content. Although intraspecific oak–oak HR was initially the highest, after 60 days all species contained approximately 20% HR water, indicating no persistent species-specific advantage. A second experiment analyzing natural δ18O abundance revealed pronounced diurnal dynamics of HR water use in oak seedlings. Contrary to expectations, the HR water fraction peaked at midday, when transpiration was highest. Overall, 29 ± 6% of the daily transpired water in oak seedlings originated from HR. These results demonstrate that HR can substantially contribute to seedling water use during dry periods, highlighting the ecological importance of HR for understory plant water supply in temperate forests. Future studies should analyze specific pathways through which HR water is transported from redistributing plants to the roots of receiving plants to assess the impact of plant species, degree and type of mycorrhization or soil physical properties on HR.

Introduction

Hydraulic redistribution (HR) of soil water through roots of mature trees occurs along a soil moisture gradient, usually during dry climatic conditions (Prieto et al., 2012; Richards and Caldwell, 1987). Water is transported through the root system from moist to drier soil layers, mainly overnight when stomata are closed and tree water storage is filled (Richards and Caldwell, 1987). Hydraulic lift (HL) from deep moist to surface-dry soils, has been found mainly in deep-rooted plants from mostly Mediterranean and dry climates (Jackson et al., 2000; Prieto et al., 2012). However, due to more frequent drought events in temperate regions, studies have shown that temperate trees are also able to redistribute water in the soil (Hafner et al., 2017, 2025; Nadezhdina et al., 2009; Zapater et al., 2011).

Shallow rooted understory plants (SRUP) are particularly vulnerable to drought events due to their limited access to water in deeper soil layers. HR water transported by mature trees during drought conditions may play a critical role in the water balance of SRUP (e.g., Dawson, 1996; Hafner et al., 2025), potentially enhancing their survival and resilience during extended dry periods (Brooks et al., 2002; Pang et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2006). Although the contribution of redistributed water to the daily transpiration of SRUP remains uncertain, estimates suggest that redistributed water could account for up to one third the daily transpiration (Hafner et al., 2021, 2025). For small Acer saccharum (Marshall) trees, Dawson (1996) showed that during two periods of drought, between 7 and 17% of their transpiration water originated from HR water by bigger trees. However, to our knowledge, no study has investigated the diurnal pattern of HR water in SRUP transpiration. It remains unclear whether HR water enables SRUP to maintain transpiration during peak daily temperature and light intensity, conditions under which sustained gas exchange may be critical for preventing heat stress, or whether HR water is largely depleted during early morning hours, potentially leaving SRUP more vulnerable to midday drought stress. While stomatal closure is a protective response, the timing and extent of water availability may still influence the physiological resilience of SRUP under extreme conditions. However, since HR occurs overnight, it seems plausible that most of the HR water taken up by SRUP is used during early morning transpiration, with its contribution gradually decreasing throughout the day.

Moreover, it is unclear if all SRUP can access HR water equally. There are two main pathways how SRUP can access HR water. One possibility is the direct uptake of water released into the soil (Hafner et al., 2017, 2021; Querejeta et al., 2003; Sun et al., 1999; Warren et al., 2008). However, fine roots of SRUP must be in close proximity (scale of mm) to fine roots of the HR tree, since HR water may not travel far beyond the rhizosphere soil of the redistributing tree, especially under dry soil conditions. Alternatively, HR water may be exchanged over longer distances (scale of cm) via a common mycorrhizal network (Egerton-Warburton et al., 2007; Querejeta et al., 2007). This suggests that seedlings of the redistributing tree may have greater access to HR water since they often establish within the rooting zone of the mature fruiting tree. This is particularly true for oak, where seedlings tend to germinate in the root zone around the mature tree due to the weight of the acorns (Uhl, 2011). Additionally, other species that share mycorrhizal fungi with the redistributing tree, forming a common mycorrhizal network that could facilitate the water transfer, may take up HR water. In this case the amount may depend on the mycorrhizal overlap. While these factors suggest a potential influence of species identity on HR water distribution, it remains uncertain to what extent water redistribution varies depending on the species involved.

In this study HR during natural drought conditions in stands of oak (Quercus robur L. and Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), a tap rooted species with high HR potential (Zapater et al., 2011), was investigated. We conducted two separate field experiments to investigate the transport patterns of HR water from the mature oaks to neighboring SRUP. In a first experiment, the uptake of HR water by different SRUP species was investigated. In a second experiment, we quantified the proportion of HR water in the transpiration of oak seedlings throughout the day. We hypothesized:

H1: The contribution of HR water from mature oak to understory plants’ tissue water is higher in oak seedlings than in other shallow rooted understory plants.

H2: The contribution of HR water to seedlings by mature oaks is highest during the morning and decreases during the day as HR happens overnight.

Materials and methods

Site description and experimental setup

To answer the hypotheses two different field experiments were conducted in 2023 and 2024 during natural periods of drought in Bavaria and Brandenburg, Germany.

HR water uptake across mycorrhizal types (labeling experiment)

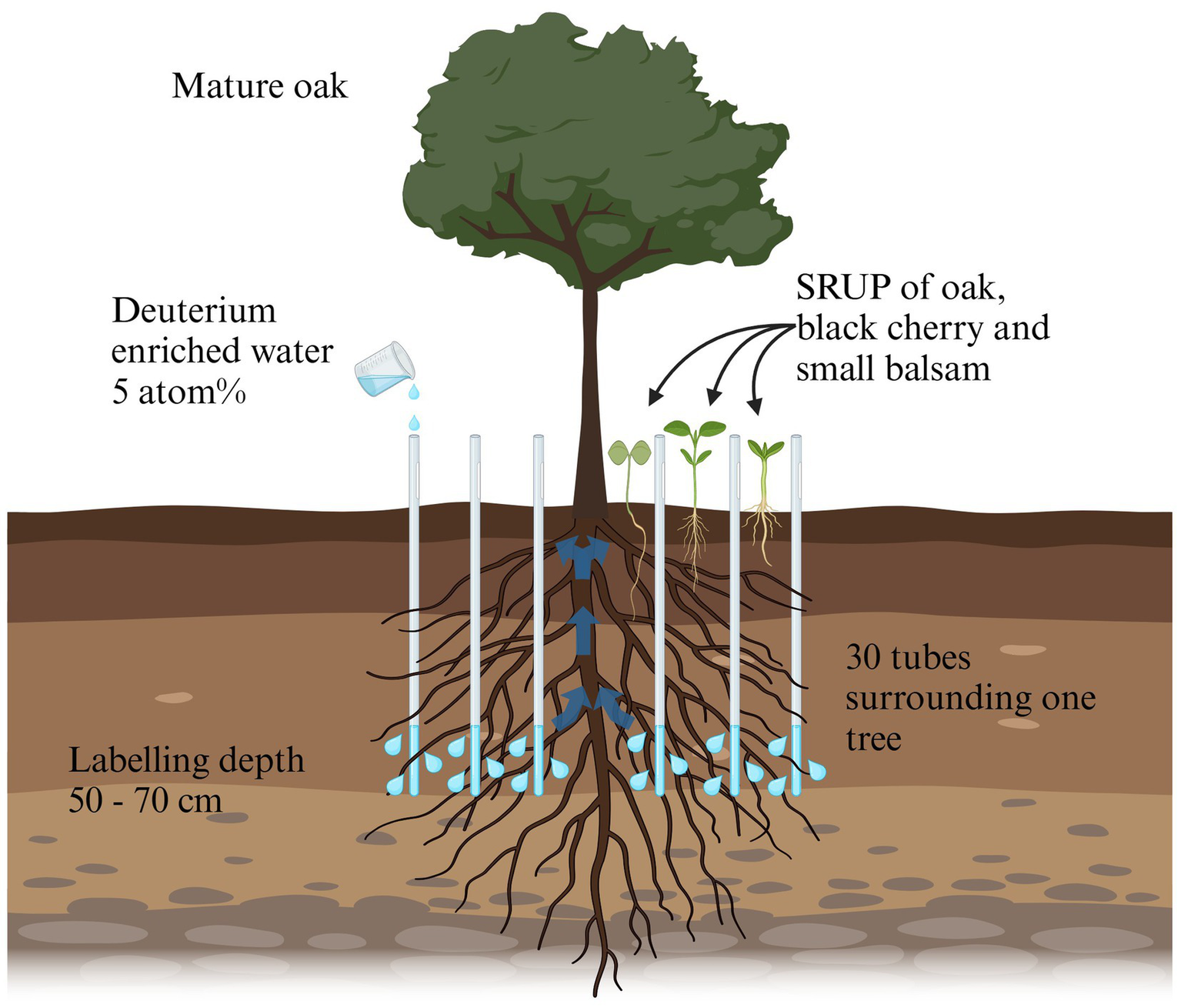

The labeling experiment was conducted in a monocultural oak (Quercus robur L.) stand (0.4 ha) in Brandenburg (Zwillenberg-Tietz-Stiftung, 52°32′17.66″N, 12°40′5.43″E). Five oaks of similar DBH (30.98 ± 2.31 cm) were selected, based on high abundance (>10 per species) of surrounding shallow rooted understory plants (SRUP). We selected three different SRUP species with different predominant mycorrhization types: oak seedlings (ectomycorrhiza, EM), black cherry seedlings (Prunus serotina Ehrh.; arbuscular mycorrhiza, AM and EM) and small balsam (Impatiens parviflora DC.; AM, sometimes no mycorrhization) (Fruleux et al., 2023; Harley and Harley, 1987; Heklau et al., 2022). Per each mature tree, 30 PVC tubes (1 m length, 13 mm inner diameter, MCM Systeme, Viersen, Germany) were inserted for 2H-labeling into the surrounding soil within a radius of 1.5 m from the stem. The tubes were vertically installed in the soil to a depth of 70 cm (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figures S1, S2). Each tube was perforated at the lower 20 cm and the bottom was sealed with a plug (for further details see Hafner et al., 2025).

Figure 1

Schematic figure of the experimental setup of labeling experiment. A total of five mature oaks with surrounding shallow rooted understory plants (SRUP) of oak, black cherry and small balsam were selected. Within a radius of 1.5 m surrounding the mature tree, 30 perforated PVC-tubes were equally distributed in a circle. 21 days after the tubes were installed, a total of 7.2 L of 2H labeled water per tree was inserted through the tubes to a soil depth of 50–70 cm, well below the maximum rooting depth of the SRUP. Six and 60 days after the labeling, soil samples and SRUP roots were sampled, and analyzed for δ2H enrichment due to HR by the mature tree. Created in Biorender (https://BioRender.com/n87t455).

Soil water content (SWC) was recorded every 15 min near each tree with two time-domain-transmission sensors (Supplementary Figures S1, S3, TMS-4, TOMST s.r.o., Prag, Czech Republic, Wild et al., 2019). One sensor was installed in 60 cm depth to monitor SWC within the labeled area and one in 10 cm to monitor SWC in the surface soil where the SRUP had their roots. We sampled soils in 10 and 60 cm depth and analyzed soil particle distribution using the integral suspension pressure method (Pario, Meter Group, Inc., Pullman, USA, Durner and Iden, 2021). Soil particle distribution was used to calculate soil water retention according to the equation of van Genuchten (1980) and with the values of Wessolek et al. (2009). Using the retention curve, measured SWC was transferred to soil matric potentials (SMP) (for calculations and specific values used to determine the retention curve, see Supplementary Figures S4, S5 and Supplementary Equation S1).

During a dry period in July 2023 (<3 mm of rain in 16 days before labeling started, average SWC of 17.6 ± 0.4% in 10 cm depth; Table 1), in total 7.2 L 2H enriched water (5 atom%) was added during a period of 6 days via tubes to 50–70 cm soil depth. Soil and plant material were sampled before labeling (t0) and six (t6) and 60 days (t60) after the labeling started. The sampling was done during dawn. On each sampling day, two soil cores (80 cm depth, 2 cm diameter, Pürkhauer) were taken in the labeled area, ~1 m to the north and to the south side of the labeled tree. Soil samples from 10 to 80 cm were segmented into 10 cm samples, while the surface soil (0–10 cm) was sampled in three labeled tree were taken from the lower stem (30–40 cm height) using an incremental drill (diameter 0.5 cm). Samples were taken from the north side of the stem, and only the conducting sapwood (~2–3 cm depth), assessed using the light transmission method, was sampled. Per labeled tree, three SRUP per species were carefully excavated and roots and shoots photographed before separately sampling them for isotopic analysis. All samples were quickly collected into airtight 12 mL exetainer vials (LabCo, Lampeter, UK), transported to the lab in a Styrofoam box and stored at −18 °C until further analyses. Total root length was measured from images using ImageJ (ImageJ 1.53e). We used this as a proxy for maximum potential rooting depth, acknowledging that this likely overestimates actual depth since roots do not grow strictly vertically. For each species and timepoint, we averaged all root lengths and refer to this parameter as mean rooting depth.

Table 1

| Timepoint | Soil depth (cm) | SWC (vol-%) | SMP (kPa) | Gradient SWC (vol-%) | Gradient SMP (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t0 | 10 | 17.6 ± 0.4aA | −13.7 ± 1.4aA | 4.6 ± 1.3A | 8.9 ± 2.7A |

| 60 | 22.2 ± 0.5bA | −4.9 ± 0.6bA | |||

| t6 | 10 | 15.9 ± 0.3aA | −20.9 ± 1.8aA | 3.8 ± 1.1A | 12.3 ± 3.8A |

| 60 | 19.7 ± 0.5bA | −8.6 ± 1.2bA | |||

| t60 | 10 | 10.9 ± 0.4aB | −118.5 ± 20.7aB | 4.0 ± 0.9A | 89.0 ± 36.6A |

| 60 | 14.9 ± 0.4bB | −29.5 ± 4.2aA |

Volumetric soil water content (SWC, vol-%) and soil matric potential (SMP, kPa) in two soil depths across three sampling times.

The SWC and SMP gradients are shown for each sampling point. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences between soil depths (10 cm and 60 cm) per sampling time. Uppercase letters indicate significant differences within the same soil depth across sampling times. Values are shown as mean ± 1 SE.

Diurnal dynamics of HR water uptake (diurnal experiment)

The diurnal experiment was conducted in a mixed oak-beech forest in Bavaria (Aura forest, 50°13′21.91″N, 9°39′44.21″E) in August 2024 on two consecutive days under dry, stable weather conditions. Temperature, humidity or VPD did not differ between the 2 days (climate station: Aura im Sinngrund, 50°10′49.8″N, 9°34′27.48″E, ~7.8 km away from the experimental plot, Supplementary Figure S6). Five plots with >15 oak seedlings surrounded by mature oaks (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) were selected. Three seedlings per plot were excavated at each of six timepoints (afternoon “an1”: 04 p.m., sunset “ss”: 09 p.m., predawn “pd”: 05 a.m., sunrise “sr”: 06 a.m., midday “md”: 12 p.m., late afternoon “an2”: 05 p.m.). Samples of an1 and ss were taken on day one, the rest on day two. Since weather conditions were consistent, data were combined into a diurnal window from predawn to sunset. Before excavation, seedlings’ transpiration was measured with a porometer (LI-600, LI-COR Environmental, Lincoln, United States) and daily transpiration rates were calculated assuming linear increase or decrease between sampling times. Seedlings were photographed to measure root length and shoot length and leaf area later with ImageJ (ImageJ 1.53e) as in labeling experiment. Roots and shoots (with leaves) were collected in separate 12 mL exetainer vials. Additionally, soil samples (midday and predawn) were taken in the middle of each plot the same way as in labeling experiment. Finally, also xylem samples from the nearest mature oak at a height of 30–40 cm were collected at each sampling time and plot. All samples were stored at −18 °C until further analyses.

Water extraction and isotope analysis

Water from all samples, except for shoot and leaf samples, from both experiments was extracted for 120 min via cryogenic vacuum extraction (West et al., 2006). In labeling experiment, δ2H, and in diurnal experiment, δ18O values were analyzed using an isotope ratio mass spectrometer coupled to a multiflow system (IsoPrime 100 and IsoPrime Multiflow, Stockport, UK) with a measurement precision of δ2H: SD ≤ 2‰; δ18O: SD ≤ 0.3‰. Samples were corrected with monitoring standards (heavy: δ2H = 127.14‰, δ18O = 14.35‰; light: δ2H = −179.22‰, δ18O = −26.74‰) and expressed in the delta notation against the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW). The measurements were done at the institutional facilities. To determine total water content in the SRUP, shoots with leaves were dried per seedling and water content was calculated as the difference between dry and harvest weight.

Mixing models

To evaluate the fraction of redistributed water in seedlings in labeling experiment six (f_seedling_t6) and 60 (f_seedling_t60) days after the labeling started, two endmember mixing models (Equations 1, 2) were calculated:

The values δ2Hseedling_t0 represent seedling root water composition before labeling. The values δ2Hseedling_t6 and δ2Hseedling_t60 represent the isotopic composition of seedling root water six and 60 days after labeling started. δ2Hxylem_t6 and δ2Hxylem_t60 represent xylem water composition in the mature oaks six and 60 days after the labeling started.

In diurnal experiment, we assumed that as soil depth increased, the δ18O signature of soil water would become more negative. Therefore, we considered HR water uptake by seedlings if δ18O values were lower (i.e., reflecting deeper soil water sources) than those of seedlings sampled at sunset, when we assume that no (or the least amount of) HR water was present in seedlings’ tissue. Indeed, δ18O values were highest and corresponded to surface soil layers. We also assumed that water uptake depth of the seedlings did not change during the day. Accordingly, the fraction of redistributed water in roots of the seedlings at each timepoint (f_seedling_pd/sr/md/an1/an2) was calculated as (Equation 3):

The values δ18Oseedling_sunset represent the composition of the water in the seedling roots at sunset. The values δ18Oseedling_pd_sr_md_an1_an2 and δ18Oxylem_pd_sr_md_an1_an2 represent the composition of the water in the seedling root and xylem of the mature tree at the respective sampling times. Standard errors of the model calculations were assessed for both experiments with the isoerror 1.04 tool (Phillips and Gregg, 2001).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in R using RStudio (R Development Core Team, 2023). In labeling experiment, δ2H values were tested for significant differences between time points t0, t6, and t60. In diurnal experiment, δ18O values were tested for significant differences between all sampling times and the sunset sampling time. For both experiments, homogeneity of variances was assessed using Bartlett’s test and the Fligner–Killeen test, while normality of residuals was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. In labeling experiment, the Shapiro–Wilk test revealed a deviation from normality. In diurnal experiment, Bartlett’s test revealed non-homogeneity of variances for δ18O values. Therefore, the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test was applied in both experiments and pairwise comparisons were performed with Dunn’s post-hoc test using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (package “dunn.test” version 1.3.6; Dunn, 1964). All data are presented as mean ± 1 standard error (SE). In diurnal experiment two exponential soil profiles were calculated correlating δ18O values to the specific soil depth. The first profile shows the correlation between δ18O in soil water and soil depth. The second profile shows the same correlation but without the values in 4.5 cm and 8 cm depth. The mean δ18O values of these two depths were tested for significant differences from the corresponding δ18O values of the estimated soil profile (excluding the values at 4.5 cm and 8 cm) using a paired t-test.

Results

Labeling experiment

The SWC in 10 cm soil depth was significantly lower than in 60 cm depth at all sampling times and the same was observed for SMP (p = 0.067 at t60; Table 1). In 10 cm depth, SWC and SMP were significantly lower at t60 compared to the other sampling times, while in 60 cm, this was observed only for SWC, not for SMP. The gradient in SWC between soil depths was not different between time points (all about 4 vol-%; Table 1). However, the gradient in SMP between 10 and 60 cm was by trend the largest at t60 (89.0 ± 36.6 kPa, p = 0.05 vs. t0 (8.9 ± 2.7 kPa) and p = 0.06 vs. t6 (12.3 ± 3.8 kPa); Table 1).

Soil water samples showed an enrichment of 447 ± 174‰ in 40–80 cm depth at t6 compared to t0 (Figure 2). The upper soil layers (0–30 cm) did not differ significantly from t0 samples, though a trend toward δ2H enrichment was observed in 3–6 cm (−1.0 ± 8.1‰; p = 0.08; Figures 2a,b). At t60, significant enrichment was detected in 30–80 cm, while the 0–20 cm layer remained unchanged to t0 samples. The 20–30 cm layer showed a tendency toward enrichment (p = 0.10; Figure 2c).

Figure 2

δ2H value per soil depth at (a) t0 before labeling started (orange & gray dots and line), (b) at t6–6 days after labeling started (blue dots and line), and (c) at t60–60 days after labeling started (green dots and line). The gray shaded area represents the labeling depth (50–70 cm). Asterisks indicate significant δ2H differences between t0 and post labeling values (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, (*) p = 0.056; blue = t6, green = t60). Vertical dashed-dotted colored lines represent mean δ2H value of xylem water in mature oaks (n = 4, colored shaded area). All values are given as means ± 1 SE. Additional horizontal black lines indicate the mean rooting lengths of excavated SRUP at sampling [showing only the mean without SE per species and sampling time for simplicity; solid = oak (SE at t0 = 1.1 cm, t6 = 1.4 cm, t60 = 1.1 cm), dashed = black cherry (SE at t0 = 1.0 cm, t6 = 0.4 cm, t60 = 0.8 cm), and dotted = small balsam (SE at t0 = 0.3 cm, t6 = 1.1 cm, t60 = 0.9 cm)]. Note: δ2H values on the x-axes are in log scale.

In mature oak, δ2H value in xylem water increased from −64.6 ± 7.8‰ (t0) to 143.8 ± 79.7‰ (t6) and remained enriched (78.1 ± 39.0‰) at t60 (vertical dashed orange, blue and green lines in Figures 2a–c, respectively).

The mean root length of SRUP did not vary significantly within species. Between species, oak had the deepest and small balsam the shallowest rooting depth (Figure 2). At t6 the measured mean root lengths were 17.0 ± 1.4 cm (oak), 8.6 ± 0.4 cm (black cherry) and 5.8 ± 1.1 cm (small balsam). At t60, the measured mean root lengths were similar in oak (16.1 ± 1.1 cm) and small balsam (6.8 ± 0.9 cm), whereas black cherry (12.8 ± 0.8 cm) had deeper mean root lengths. Mean rooting depths of all three species were more shallow than labeling depth and capillary rise of label on t60 (Figure 2).

Root water δ2H values at t6 and t60 were enriched in all three SRUP species. At t6, δ2H increased by 28‰ in oak, 22‰ in black cherry and 13‰ in small balsam. By t60, enrichment remained at 19‰ in oak and 18‰ in black cherry, showing a slight decrease from t6, while in small balsam, δ2H enrichment increased to 19‰, exceeding its t6 value (Table 2).

Table 2

| Species | Sampling time | δ2H (‰) |

|---|---|---|

| Oak | t0 | −28.9 ± 3.7 |

| t6 | −0.7 ± 6.9*** | |

| t60 | −9.8 ± 4.3* | |

| Black cherry | t0 | −27.1 ± 3.4 |

| t6 | −5.4 ± 8.0* | |

| t60 | −9.2 ± 4.9* | |

| Small balsam | t0 | −21.8 ± 3.2 |

| t6 | −8.2 ± 1.9* | |

| t60 | −2.2 ± 3.2** |

δ2H value of SRUP root water per species at sampling times before labeling (t0), 6 days after labeling started (t6) and 60 days after labeling started (t60).

Statistics indicate significant differences between t0 and after labeling values per species (* < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001). Values represent mean ± 1SE.

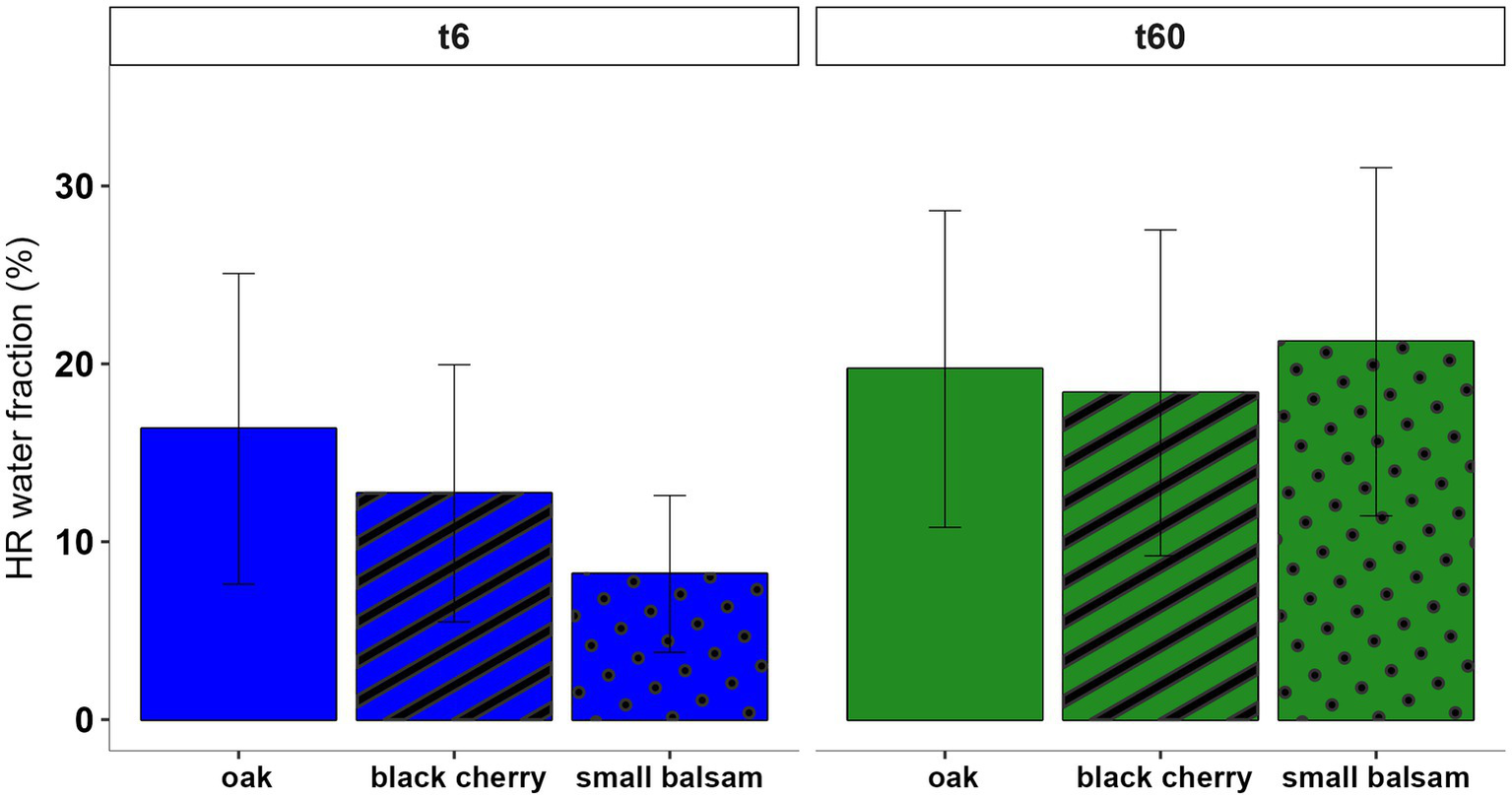

At t6, oak seedlings had the highest fraction of HR water in their roots (16 ± 8% corresponding to 51 ± 9 μL, n = 12), followed by black cherry (13 ± 7% corresponding to 18 ± 3 μL, n = 9) and small balsam (8 ± 4% corresponding to 36 ± 10 μL, n = 7), with no significant differences between species. By t60, approximately 20% of root water in all SRUP originated from redistributed water by mature oak (Figure 3).

Figure 3

HR water in SRUP root water by species (bars with no pattern = oak, bars with stripe pattern = black cherry and bars with dotted pattern = small balsam) at t6 (blue bar) and t60 (green bar). Values represent mean ± 1SE. No significant differences were found between the species at either t6 or t60.

Diurnal experiment

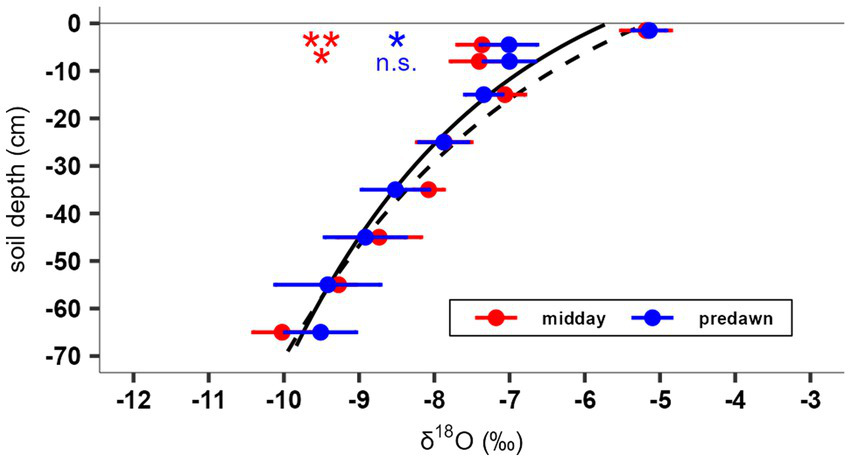

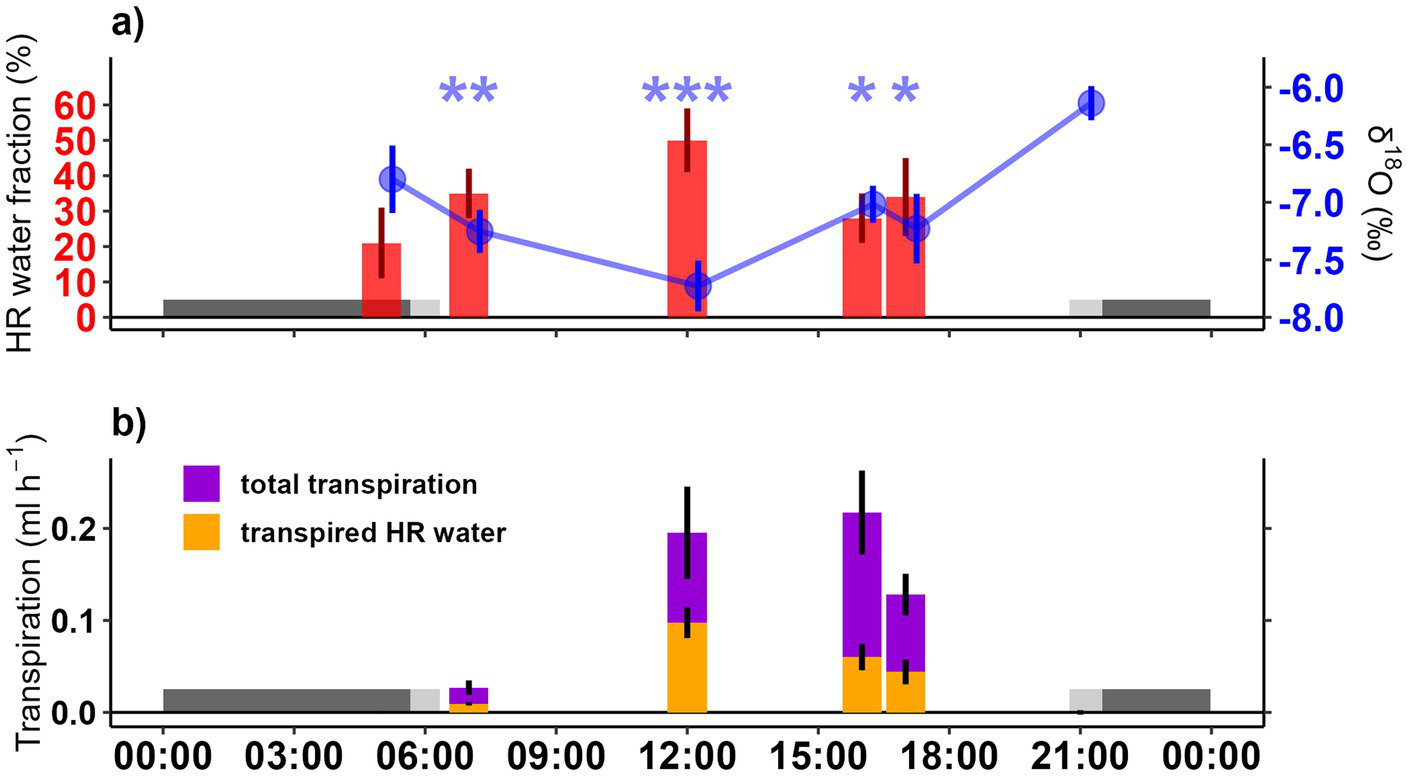

Soil δ18O values did not differ significantly between midday and predawn and decreased exponentially with soil depth. However, δ18O values were significantly deviating from the calculated soil profile (Figure 4) in 4.5 cm depth at midday and predawn and in 8 cm depth only at midday. In sampled seedlings, total water content, leaf area and rooting length (15.2 ± 0.4 cm) remained consistent across sampling times (Table 3). However, δ18O in seedlings’ root water exhibited a diurnal pattern, peaking at sunset. As δ18O values in both afternoons showed no significant differences, all measured values were merged into a single diurnal cycle from predawn to sunset (see Methods and Figure 5). δ18O decreased from predawn to midday, then increased again in the afternoon (Figure 5a). This pattern suggests that seedlings accessed water from progressively deeper soil layers until midday, followed by a shift toward more superficial sources later in the day. Notably, the midday minimum δ18O value corresponded to a soil depth (approximately 25 cm) that exceeded the estimated maximum rooting depth of the seedlings, implying that this water may have originated from hydraulic redistribution by deeper-rooted trees.

Figure 4

δ18O values by soil depth at midday (red) and predawn (blue) ± 1 SE in diurnal experiment. The solid black line represents an exponential fit of the δ18O soil profile using all values, while the dashed black line represents the fit excluding values at 4.5 and 8 cm depth. Red and blue asterisks indicate significant differences between measured values in 4.5 and 8 cm depth from the calculated theoretical soil δ18O value on the dashed line (**p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, n.s. p ≥ 0.05).

Table 3

| Time | n | Rooting depth (cm) | Total plant water (mL) | Leaf area (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predawn (05:00) | 15 | 13.72 ± 0.74 | 0.81 ± 0.05 | 12.40 ± 1.76 |

| Sunrise (07:00) | 15 | 16.95 ± 1.41 | 0.99 ± 0.07 | 11.85 ± 1.32 |

| Midday (12:00) | 15 | 15.37 ± 0.94 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 17.46 ± 1.72 |

| 1. Afternoon (16:00)* | 15 | 15.17 ± 0.58 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 16.81 ± 1.64 |

| 2. Afternoon (17:00) | 15 | 15.27 ± 1.03 | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 12.54 ± 1.08 |

| Sunset (21:00)* | 15 | 14.86 ± 0.72 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 14.53 ± 1.53 |

Mean rooting depth (cm), total water content (mL; including roots, shoots, and leaves) and leaf area (cm2) of seedlings at different sampling times.

Sunset (21:00) and early afternoon (16:00; marked with an asterisk) samples were collected 1 day earlier than the others. Values are presented as mean ± 1 SE. No significant differences in seedling parameters were found between sampling times.

Figure 5

(a) Fraction of HR water (red bars) and δ18O values (blue dots and line) in root water during the diurnal cycle. Fraction of HR water was calculated based on the δ18O values at sunset (Equation 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences in δ18O-values between sunset and the other sampling times (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, and *p < 0.05). Bars and dots are slightly shifted along the x-axis to avoid overlapping SE values and improve visibility. (b) Transpiration rates (ml h−1; purple bars) and the corresponding fraction of transpired HR water (orange bars) at the different sampling times. All values are presented as mean ± 1 SE. Dark gray shaded area indicates nighttime, while light gray shaded area indicates dusk and dawn in both panels. Note that sunset (21:00) and early afternoon (16:00) samples were taken 1 day before the others. Since no significant differences were found between the two afternoon samples and weather conditions remained constant across both days, all samples were merged into a diurnal cycle starting from predawn to sunset.

Mixing model calculations (Equation 3) indicated that at midday, 50 ± 9% of seedlings’ root water originated from HR, compared to ~30% at sunrise and in the afternoons (Figure 5a). Transpiration rates increased from morning to midday, when it reached 1.79 ± 0.24 mmol m−2 s−1 (0.2 mL h−1), remained stable until afternoon and then declined toward the evening (Figure 5b). Assuming root water reflected also transpired water due to limited seedlings water storage, ~0.1 mL h−1 of HR water was transpired during midday (Figure 5b). The total daily transpiration of the seedlings was 1.81 ± 1.67 mL, and overall 29 ± 6% (~0.6 mL) of the daily transpired water originated from HR water of mature oak.

Discussion

In this study we investigated patterns and dynamics of uptake of HR water by SRUP of different species. We quantified diurnal distribution and usage of HR water by SRUP. While oak seedlings initially contained the highest fraction of HR water by mature oaks, HR water contributions to SRUP root water eventually equalized across species. HR water was present in SRUP root water throughout the entire day, accounting for up to 50% of total root water. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, HR water contribution to seedlings’ water peaked at midday and declined afterwards, following the pattern of daily transpiration.

Uptake of HR water by seedlings

In labeling experiment, no SRUP had roots deep enough to reach the soil layers where the label accumulated at t6. At t60, one oak and one black cherry with the longest roots potentially reached the soil depth were label accumulated in soil depth 20–30 cm (Figure 2c). However, most oak and black cherry seedlings had root lengths shorter than the labeled soil depth at t60 (<20 cm). Additionally, at both sampling times the seedlings with longer root lengths were equally enriched in δ2H as the seedling with shorter root lengths, confirming that they took up HR water from the surface soil rather than directly from the labeled soil layers.

The results from diurnal experiment showed no variation in the δ18O soil profile between midday and pre-dawn sampling. This lack of temporal variation likely reflects the large soil water pool relative to the small amount of redistributed water, which may be sufficient to alter the isotopic composition of seedling root water but insufficient to measurably change bulk soil water isotopic signatures. In addition, the absence of detectable differences may indicate that no roots of mature trees were present in the sampled soil cores. Pre-dawn and midday soil cores were intentionally taken in close proximity to each other to minimize spatial variability in soil properties. Consequently, the decrease in δ18O in seedling root water, despite unchanged soil profiles, indicates water uptake from deeper soil layers (Brinkmann et al., 2018; Kahmen et al., 2022). By midday, the measured root water δ18O corresponded to a soil depth of approximately 20 cm. This exceeds the mean root length of the seedlings (Table 3), suggesting that seedlings accessed HR water provided by mature trees from deeper soil layers. These findings align with previous studies where HR was detected in seedlings, reflected by lower δ18O values in the morning compared to the afternoon, when transpiration started (Hafner et al., 2025). This suggests that the water taken up in both experiments likely originated from HR rather than direct uptake from deeper soil layers.

Redistribution of labeled water by mature trees (labeling experiment)

In labeling experiment, at t6 δ2H showed a non-significant enrichment (p = 0.08) in the 3–6 cm surface soil layer, which was not found at t60. This enrichment may reflect localized release of hydraulically redistributed water into the rhizosphere of mature tree roots. Given the strong spatial heterogeneity of HR, soil cores that are not taken in close proximity to active fine roots may fail to capture these localized isotopic signals. Although soil cores at t0, t6, and t60 were taken in close proximity, small differences in sampling position may have resulted in variable proximity to active roots. In addition, a short rain event occurring between t6 and t60 likely contributed to dilution or homogenization of soil water isotopic signatures, further masking potential HR-related enrichment in bulk soil water.

However, since the intermediate soil layers (6–10, 10–20, 20–30, and 30–40 cm) showed no enrichment compared to t0 (Figure 2), capillary rise or diffusion of water can be ruled out as the cause for this increase. Instead, this may indicate the release of HR water into the drier top soil via the root system of the mature trees (Prieto et al., 2012; Zapater et al., 2011), as their xylem δ2H was significantly enriched at t6 (Figure 2).

At t60, a significant δ2H enrichment was observed in upper soil layers (30–40 cm and by trend in 20–30 cm) compared to those at t6 (Figure 2), which could be attributed to diffusion and/or capillary rise. Since labeled water only moved 20 cm (from 40 cm at t6 to 20 cm at t60) over 54 days (t6 to t60), the estimated rate of water traveling via capillary rise in the soil was at about 0.4 cm per day and therefore negligible as a potential transport way of the labeling at t6. In our sandy soil environment, diffusion between H and 2H across the 45 cm distance (i.e., from the labeling depth at 60 cm to the average rooting depth of seedlings at ~15 cm) can be neglected as a relevant transport process, since calculations indicated that it is too slow (see Supplementary material). This further supports our conclusion that HR via mature oak roots was the primary source of labeled water in the surface soil.

The soil matric potential gradient between the labeling depth and the topsoil was not very high (~12 kPa at t6 and ~89 kPa at t60; Table 1). While HR has been observed even under moderate drought conditions (Hafner et al., 2017), its magnitude and the extend of water release into the soil and toward neighboring species likely increases with steeper soil water potential gradients (Hafner et al., 2020).

Mycorrhizae or soil as transport path for redistributed water toward SRUP (labeling experiment)

The fraction of HR water in SRUP was between 8 and 16% at t6 and increased to ~20% at t60 across species. Those values align with previously reported values in Douglas fir seedlings in semi-arid areas (21.6%; Schoonmaker et al., 2007) and several temperate tree species seedlings (16%, Hafner et al., 2025). At t6, oak seedlings had the highest fraction of HR water in their roots, followed by black cherry, while small balsam had the lowest (Figure 3). Previous studies have shown that HR water was transported through mycorrhizal fungi in potted oak seedlings (Querejeta et al., 2003) and water transport between species is generally possible by shared mycorrhizae (Egerton-Warburton et al., 2007; Querejeta et al., 2007). The SRUP species in labeling experiment are associated with different types of mycorrhizae. While oak only forms symbioses with EM (Harley and Harley, 1987), black cherry mostly is found with AM (Heklau et al., 2022), rarely also with EM, especially in Europe (Fruleux et al., 2023). Small balsam is only associated with AM or has no mycorrhization at all (Harley and Harley, 1987). Although we did not assess mycorrhizal associations in this study, a potential mycorrhizal dissimilarity between black cherry and small balsam SRUP to mature oaks could help to explain the observed trend in the fraction of HR water uptake in SRUP root water at t6. By t60, however, all three SRUP species showed similar fractions of HR water in root water. The similar fractions over all SRUP species could be explained by the deeper rooting depth of black cherry, but not for small balsam. This appears contradictory to the clear pattern at t6 and to our hypothesis 1. One possible explanation is that the gradient in SMP between deep and surface soil tended to be higher at t60 than at t6 (Table 1), which could indicate more redistribution of water (Hafner et al., 2020) through mature oaks and explain the generally higher fractions of HR water in SRUP (Figure 3). Additionally, the labeled water may have been mobilized and redistributed in the upper soil during the 54-day period through soil hydraulic conductivity and by rainfall events that promoted water movement within the soil matrix. The δ18O values at 4.5 cm and 8 cm deviated from the fitted soil water profile (Figure 4) and may reflect HR from deeper soil layers. However, soil water isotope profiles can also be influenced by mixing of water and redistribution processes in the root zone, as discussed by von Freyberg et al. (2020). As result, all species may have had more equal opportunities to take up labeled water, regardless of their mycorrhizal associations or spatial proximity to the fine roots of mature oaks. Finally, the label could have also been built up in the plants over 60 days and not all be transpired right away. Patterns of increasing contribution of a tracer to plant tissue water through mycorrhizal transport have been previously described (Kakouridis et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2024) but no clear explanation has been given so far. We summarize that oak seedlings took up a higher fraction of HR water within a shorter period of time than the other two SRUP while in the long term, all species may benefit to a similar extent from HR water. However, pathways need to be investigated in further studies.

Diurnal dynamics of HR water uptake (diurnal experiment)

The δ18O value in the seedlings at sunset was chosen as endmember for our mixing model, because δ18O at sunset was the highest, reflecting surface water origin (approximately 4 cm soil depth, Figures 4, 5). Although a noticeable fraction (21–35%) of HR water was found already at predawn and at sunrise, respectively, the highest fraction of HR water in seedlings was detected at midday (approximately 50%). In the afternoon, the contribution of HR water to seedlings’ water started to decrease, suggesting that the HR water ‘reservoir’ was getting lower. However, even at 5 p.m., a relevant fraction (30%) of root water originated from HR. Transpiration measurements showed that the seedlings transpired ~1.8 mL of water daily, while their average water content was ~0.9 mL (Table 3). This indicates that the seedlings exchanged nearly twice their water content per day, with 29 ± 6% of the daily transpired water originating from HR. The estimated HR water fractions are slightly higher than those in labeling experiment. This difference could be due to the different sites or slightly different weather conditions, as the experiments were conducted in two different years and locations. Nevertheless, the values remain consistent with previous studies on HR water contributions to seedlings’ transpiration (e.g., Dawson, 1996; Hafner et al., 2021; Richards and Caldwell, 1987). These results reject our hypothesis 2. HR water was utilized throughout the day, with observed accumulation peaking around midday, coinciding with the period of the highest transpiration. While our mixing model attributes the shifts in δ18O solely to HR water uptake, we acknowledge that other physiological processes, such as phloem-mediated exchange or tree-internal water redistribution (Grau et al., 2025; Nehemy et al., 2022; Tierney et al., 2025) might also contribute to the observed diurnal patterns. Therefore, potential daytime redistribution of deep soil or stem stored water by mature trees should be investigated. However, given that we restricted the sampling to roots and the small size of the root systems of the seedlings, such exchange mechanisms are likely to play a minor role, though further research is needed to fully disentangle their potential influence.

Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of HR water for SRUP in temperate forests. Shared mycorrhizal networks may facilitate faster access to redistributed water. However, other pathways, including spatial relationships between interacting root systems of different species should be explored (Paya et al., 2015). Interestingly, HR water is utilized by the seedling throughout the day, peaking at midday and suggesting that HR may indeed support SRUP water consumption under water limited conditions when it is most needed. Future research should explore interactions between shallow-rooted and tap-rooted mature trees to better understand HR water dynamics, as well as how the physical distance and mycorrhizal networks between SRUP and the redistributing tree influence HR water uptake.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DD: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. TGe: Writing – review & editing. PA: Writing – review & editing. TGr: Writing – review & editing. BH: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The work for this content was funded by Fachagentur Nachwachsende Rohstoffe (FNR) and Waldklimafonds (2220WK69X4).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Horst Bachmeier and Thomas Feuerbach for their technical assistance. We would also like to thank Simeon Gotthardt and Lasse Löffelbein for their help with sampling during the experiments. We thank Yessica Stengele, Pere Roc, Barbara Hofmann, and Xenia Koch for their help with sample preparation, water isotope extraction and measurements.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI (ChatGPT, OpenAI, deepL) was used solely to improve the English language and phrasing of the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2025.1742600/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Brinkmann N. Seeger S. Weiler M. Buchmann N. Eugster W. Kahmen A. (2018). Employing stable isotopes to determine the residence times of soil water and the temporal origin of water taken up by Fagus sylvatica and Picea abies in a temperate forest. New Phytol.219, 1300–1313. doi: 10.1111/nph.15255,

2

Brooks J. R. Meinzer F. C. Coulombe R. Gregg J. (2002). Hydraulic redistribution of soil water during summer drought in two contrasting Pacific northwest coniferous forests. Tree Physiol.22, 1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/treephys/22.15-16.1107,

3

Dawson T. E. (1996). Determining water use by trees and forests from isotopic, energy balance and transpiration analyses: the roles of tree size and hydraulic lift. Tree Physiol.16, 263–272. doi: 10.1093/treephys/16.1-2.263,

4

Dunn O. J. (1964). Multiple comparisons using rank sums. Technometrics6, 241–252. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1964.10490181

5

Durner W. Iden S. C. (2021). The improved integral suspension pressure method (ISP+) for precise particle size analysis of soil and sedimentary materials. Soil Tillage Res.213:105086. doi: 10.1016/j.still.2021.105086

6

Egerton-Warburton L. M. Querejeta J. I. Allen M. F. (2007). Common mycorrhizal networks provide a potential pathway for the transfer of hydraulically lifted water between plants. J. Exp. Bot.58, 1473–1483. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm009,

7

Fruleux A. Duclercq J. Dubois F. Decocq G. (2023). First report of ectomycorrhizae in Prunus serotina in the exotic range. Plant Soil484, 171–181. doi: 10.1007/s11104-022-05780-z

8

Grau V. A. Herbohn J. Schmidt S. McDonnell J. (2025). Bark water affects the isotopic composition of xylem water in tropical rainforest trees. Front. For. Glob. Change7:1457522. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2024.1457522

9

Hafner B. D. Hesse B. D. Bauerle T. L. Grams T. E. E. (2020). Water potential gradient, root conduit size and root xylem hydraulic conductivity determine the extent of hydraulic redistribution in temperate trees. Funct. Ecol.34, 561–574. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13508

10

Hafner B. D. Hesse B. D. Grams T. E. E. (2021). Friendly neighbours: hydraulic redistribution accounts for one quarter of water used by neighbouring drought stressed tree saplings. Plant Cell Environ.44, 1243–1256. doi: 10.1111/pce.13852,

11

Hafner B. D. Hesse B. D. Grams T. E. E. (2025). Redistribution of soil water by mature trees towards dry surface soils and uptake by seedlings in a temperate forest. Plant Biol.1, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/plb.13764

12

Hafner B. D. Tomasella M. Häberle K.-H. Goebel M. Matyssek R. Grams T. E. E. (2017). Hydraulic redistribution under moderate drought among English oak, European beech and Norway spruce determined by deuterium isotope labeling in a split-root experiment. Tree Physiol.37, 950–960. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx050,

13

Harley J. L. Harley E. L. (1987). A check-list of mycorrhiza in the BRITISH FLORA*. New Phytol.105, 1–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb00674.x

14

Heklau H. Haider S. Erfmeier A. Bruelheide H. (2022). Untersuchungen zur vesikulär-arbuskulären Mykorrhiza im Nationalpark Müritz (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Nordostdeutschland) Analysis of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in the National Park Müritz (Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Northeast Germany). Hercynia - Ökol. Umwelt Mitteleur.55, 1–44. doi: 10.25673/103140

15

Jackson R. B. Sperry J. S. Dawson T. E. (2000). Root water uptake and transport: using physiological processes in global predictions. Trends Plant Sci.5, 482–488. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01766-0,

16

Kahmen A. Basler D. Hoch G. Link R. M. Schuldt B. Zahnd C. et al . (2022). Root water uptake depth determines the hydraulic vulnerability of temperate European tree species during the extreme 2018 drought. Plant Biol.24, 1224–1239. doi: 10.1111/plb.13476,

17

Kakouridis A. Hagen J. A. Kan M. P. Mambelli S. Feldman L. J. Herman D. J. et al . (2022). Routes to roots: direct evidence of water transport by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to host plants. New Phytol.236, 210–221. doi: 10.1111/nph.18281,

18

Nadezhdina N. Steppe K. De Pauw D. J. Bequet R. Čermak J. Ceulemans R. (2009). Stem-mediated hydraulic redistribution in large roots on opposing sides of a Douglas-fir tree following localized irrigation. New Phytol.184, 932–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03024.x,

19

Nehemy M. F. Benettin P. Allen S. T. Steppe K. Rinaldo A. Lehmann M. M. et al . (2022). Phloem water isotopically different to xylem water: potential causes and implications for ecohydrological tracing. Ecohydrology15:e2417. doi: 10.1002/eco.2417

20

Pang J. Wang Y. Lambers H. Tibbett M. Siddique K. H. M. Ryan M. H. (2013). Commensalism in an agroecosystem: hydraulic redistribution by deep-rooted legumes improves survival of a droughted shallow-rooted legume companion. Physiol. Plant.149, 79–90. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12020,

21

Paya A. M. Silverberg J. L. Padgett J. Bauerle T. L. (2015). X-ray computed tomography uncovers root–root interactions: quantifying spatial relationships between interacting root systems in three dimensions. Front. Plant Sci.6:274. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00274,

22

Pereira J. S. Chaves M. M. Caldeira M. C. Correia A. V. (2006). “Water availability and productivity” in Plant growth and climate change (Blackwell Publishing Ltd), 118–145. doi: 10.1002/9780470988695.ch6

23

Phillips D. L. Gregg J. W. (2001). Uncertainty in source partitioning using stable isotopes. Oecologia128, 304–304. doi: 10.1007/s004420100723,

24

Prieto I. Armas C. Pugnaire F. I. (2012). Water release through plant roots: new insights into its consequences at the plant and ecosystem level. New Phytol.193, 830–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04039.x,

25

Querejeta J. I. Egerton-Warburton L. Allen M. (2003). Direct nocturnal water transfer from oaks to their mycorrhizal symbionts during severe soil drying. Oecologia134, 55–64. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-1078-2,

26

Querejeta J. I. Egerton-Warburton L. M. Allen M. F. (2007). Hydraulic lift may buffer rhizosphere hyphae against the negative effects of severe soil drying in a California oak savanna. Soil Biol. Biochem.39, 409–417. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.08.008

27

Richards J. H. Caldwell M. M. (1987). Hydraulic lift: substantial nocturnal water transport between soil layers by Artemisia tridentata roots. Oecologia73, 486–489. doi: 10.1007/BF00379405,

28

Schoonmaker A. L. Teste F. P. Simard S. W. Guy R. D. (2007). Tree proximity, soil pathways and common mycorrhizal networks: their influence on the utilization of redistributed water by understory seedlings. Oecologia154, 455–466. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0852-6,

29

Sun Y.-P. Unestam T. Lucas S. D. Johanson K. J. Kenne L. Finlay R. (1999). Exudation-reabsorption in a mycorrhizal fungus, the dynamic interface for interaction with soil and soil microorganisms. Mycorrhiza9, 137–144. doi: 10.1007/s005720050298

30

Tierney K. Sobota M. Snarski J. Li K. Knighton J. (2025). Sub-daily variations in tree xylem water isotopic compositions in a temperate northeastern US forest. Hydrol. Process.39:e70137. doi: 10.1002/hyp.70137

31

Uhl A. (2011). Investigation on the distribution of oak seedlings – contribution of the Eurasian jay to natural regeneration. Naturschutz Südl. Oberrhein6, 99–103.

32

van Genuchten M. T. (1980). A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J.44, 892–898. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1980.03615995004400050002x

33

von Freyberg J. Allen S. T. Grossiord C. Dawson T. E. (2020). Plant and root-zone water isotopes are difficult to measure, explain, and predict: some practical recommendations for determining plant water sources. Methods Ecol. Evol.11, 1352–1367. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.13461

34

Warren J. M. Brooks J. R. Meinzer F. C. Eberhart J. L. (2008). Hydraulic redistribution of water from Pinus ponderosa trees to seedlings: evidence for an ectomycorrhizal pathway. New Phytol.178, 382–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02377.x,

35

Wessolek G. Kaupenjohann M. Renger M. (2009). Bodenphysikalische Kennwerte und Berechnungsverfahren für die Praxis. Bodenökologie Und Bodengenese40, 1–82.

36

West A. G. Patrickson S. J. Ehleringer J. R. (2006). Water extraction times for plant and soil materials used in stable isotope analysis. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom20, 1317–1321. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2456

37

Wild J. Kopecký M. Macek M. Šanda M. Jankovec J. Haase T. (2019). Climate at ecologically relevant scales: a new temperature and soil moisture logger for long-term microclimate measurement. Agric. For. Meteorol.268, 40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2018.12.018

38

Wu C. Bi Y. Zhu W. (2024). Is the amount of water transported by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal hyphae negligible? Insights from a compartmentalized experimental study. Plant Soil499, 537–552. doi: 10.1007/s11104-024-06477-1

39

Zapater M. Hossann C. Bréda N. Bréchet C. Bonal D. Granier A. (2011). Evidence of hydraulic lift in a young beech and oak mixed forest using 18O soil water labelling. Trees25, 885–894. doi: 10.1007/s00468-011-0563-9

Summary

Keywords

drought, facilitation, hydraulic redistribution, labeling, seedlings, stable isotopes

Citation

Dluhosch D, Gebhardt T, Annighöfer P, Grams TEE and Hafner BD (2026) Shallow rooted understory plants use hydraulically redistributed water by mature oak trees during drought. Front. For. Glob. Change 8:1742600. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2025.1742600

Received

09 November 2025

Revised

31 December 2025

Accepted

31 December 2025

Published

22 January 2026

Volume

8 - 2025

Edited by

Qing-Wei Wang, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), China

Reviewed by

Xinsheng Liu, Anhui Normal University, China

Haoyu Diao, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL), Switzerland

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Dluhosch, Gebhardt, Annighöfer, Grams and Hafner.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Dluhosch, d.dluhosch@tum.de

ORCID: David Dluhosch, orcid.org/0009-0007-9676-6623; Timo Gebhardt, orcid.org/0000-0003-0047-5949; Peter Annighöfer, orcid.org/0000-0001-8126-5307; Thorsten E. E. Grams, orcid.org/0000-0002-4355-8827; Benjamin D. Hafner, orcid.org/0000-0003-2348-9200

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.