Abstract

Southern Appalachian forests have varied land-use history and are managed with different objectives, including maintenance of ecosystem services and harvesting timber. Concurrently, this region has experienced long-term wildfire suppression, causing shifts in dominant vegetation (i.e., mesophication) and is projected to have more frequent, severe drought and wildfire activity in the future. Regional wildland fire effects are not well understood in the context of the broader set of management activities, such as partial harvesting and prescribed burning, that influence soil microbial communities and the ecosystem processes they regulate. We use a taxonomic and multifunctional approach to compare soil across four watersheds with different management or disturbance histories: low-severity prescribed burning, high-severity wildfire, fire exclusion, or partial harvesting. Soil microbial community structure was influenced by historical disturbance effects, while ecosystem functions are constrained by resource availability following recent disturbance. Prescribed burns did not change microbial community composition relative to the fire excluded watershed; however, they did increase N availability and N acquisition enzyme activity. Microbial community structure of the post-wildfire and partially harvested watersheds was influenced by environmental filters related to disturbance, although microbial multifunctionality in the post-wildfire watershed was not significantly different from fire excluded and prescribed burned watersheds. The partially harvested watershed exhibited elevated NO3− and pH, increased C acquisition enzyme activity, and lowered C use efficiency relative to other watersheds. This study provides context to microbial influences on ecosystem dynamics following both anthropogenic and natural disturbances, helping managers understand the implications of management on forest soils and belowground processes.

1 Introduction

The current state of the Southern Appalachian Mountain forests in the United States is influenced by changing environmental conditions, approximately 100 years of active wildfire suppression, and a variety of landowners (e.g., state, federal, or private) that prioritize different management strategies (Wear and Greis, 2013). This results in a forested mosaic landscape that has experienced disturbance and land-use of varying magnitudes and spatial extent. Consequently, land-use history has a strong effect on the structure and function of these forests at the watershed scale and is a key consideration for understanding how new management or disturbance affects these ecosystems (Osburn et al., 2021a). Common management goals within Southern Appalachia include meeting timber demand, mitigating severe wildfire risk, and maintaining ecosystem services, including carbon (C) sequestration, water quality, biodiversity, and recreation (Wear and Greis, 2013). The use of differing management practices in conjunction with natural disturbance contributes to the complexity of current and future ecosystem dynamics of this region. Therefore, it is beneficial to understand their influences relative to one another and other disturbances.

The southeastern United States is experiencing hydroclimate variability with more prolonged periods of drought (Burt et al., 2018) and warmer temperatures, which reduce soil and vegetation moisture, and increase risk for severe wildfires (Mitchell et al., 2014; Park Williams et al., 2017; Reilly et al., 2022). This region was historically dominated by fire tolerant tree species, i.e., oak-hickory (Quercus-Carya spp.), American chestnut (Castanea dentata), due to management by indigenous communities for wildlife habitat and agriculture (Colenbaugh and Hagan, 2023; Lafon et al., 2017; Waldrop et al., 2016). Over a century of broad-scale fuel accumulation from fire exclusion reinforced by a wet climate has caused a shift in vegetation composition, from oak and pine (Pinus spp.) to less fire-adapted species, such as tulip-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera), red maple (Acer rubrum), and black gum (Nyssa sylvatica) (Elliott et al., 1999; Nowacki and Abrams, 2008; Pederson et al., 2015). While it may be impossible to return these forests to a similar historic state following a century of fire exclusion (Robbins et al., 2022) and the loss or decline of key species, such as the American chestnut and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis; Vandermast et al., 2002; Ford et al., 2012), some management efforts aim to promote fire tolerant species (Vose, 2000). The use of repeated prescribed burns is implemented to reduce fuel loading, alter fuel continuity, and shift vegetation back to more desired species (Elliott et al., 2004; Vose and Elliott, 2016). Often, these practices induce minimal long-term changes to soil properties and biota but are dependent on burn intensity and severity (Boerner et al., 2008; Certini, 2005; Dukes et al., 2020).

Soil microbial communities are sensitive to disturbance events and serve as indicators of ecosystem change because they are essential drivers of biogeochemical cycling and ecosystem function. Considering soil ecosystem process rates in conjunction with microbial properties can help land managers understand nutrient cycling dynamics following management practices or disturbance (Hall et al., 2018; Osburn et al., 2021a). Characterizing these responses is important for determining the future state of forests (Mitchell et al., 2014). While several studies have examined soil properties and biota following wildfires in Southern Appalachia (Brown et al., 2019; Carpenter et al., 2021; Schill et al., 2024), few studies have characterized long-term soil biological, physicochemical, and functional properties following both prescribed burns and severe wildfires relative to other land-use disturbances.

Efforts to determine landscape-level soil responses following both prescribed burning treatments and wildfires have found variable results associated with differing location, fire severity, and vegetation (Certini, 2005; Hahn et al., 2021; Knelman et al., 2015; Lafon et al., 2017). Fire severity directly influences vegetation, soil properties, and microbial communities through combustion, but indirectly affects microbes due to post-fire vegetation and soil property changes (nutrient content, pH, moisture, texture, forest floor mass) (Adkins et al., 2020). Prescribed fires can alter nutrient cycling dynamics, such as balancing loss and release of nutrients, and can increase forest resilience to disturbance concerns like pathogens and wildfires (Vose, 2000). Single prescribed fire treatments in Southern Appalachia have resulted in initially elevated nutrient levels that returned to pre-burned levels within the same year (Knoepp et al., 2009), whereas ericaceous shrub cut and Oi horizon burn resulted in higher soil inorganic N the following summer relative to unburned plots (Osburn et al., 2018). Osburn et al. (2018) and Rietl and Jackson (2012) have reported changes in extracellular enzyme activity following prescribed burns in mesic forests suggesting potential changes in functional diversity of soil communities.

As timber harvesting is a prevalent management goal in this region, understanding the effects of this practice relative to prescribed burn management and severe wildfire can provide insight for managers. Clearcutting has lasting watershed-level effects on soil, including altered microbial community structure, elevated nutrient cycling rates, lower C use efficiency, elevated pH, increased inorganic N mobilization, reduced organic C pools, and the promotion of shade tolerant species (Osburn et al., 2019, 2021a, 2022; Elliott et al., 2020). In contrast, current partial harvesting practices include removal of 60–80% of basal area and can promote the growth of shade tolerant species, but there is limited understanding of the impacts of this practice on biogeochemical processes (Keyser and Loftis, 2021; Elliott et al., 2020).

We sought to determine the potential impacts of wildfires and common management practices on soil microbial composition and function in the Southern Appalachian Mountains of western North Carolina. This was accomplished in the context of four different watershed histories relevant to this region: a managed watershed with repeated low-severity prescribed burns; an undisturbed, fire-excluded watershed; a watershed impacted by a severe wildfire in 2016; and a partially harvested (1986), fire-excluded watershed with evidence of historic skid roads. To accomplish this, we used (1) soil physicochemical properties; (2) 16S and ITS sequencing to determine microbial community composition and corresponding traits; and (3) an ecosystem multifunctional approach with EEA, qCO2, and qNH4 to characterize watershed-level changes in microbial properties and nutrient pools. Our findings contribute to a growing understanding of management consequences and benefits on forest dynamics as fire may become more prevalent in Southern Appalachia.

2 Methods and materials

2.1 Site description and experimental design

This study was conducted within the Southern Appalachian Mountains of Macon County North Carolina, United States. Samples were collected in a total of four watersheds to compare fire regime effects (Figure 1). This included a prescribed fire (PF) and fire-excluded (FE) watershed pair located within the Coweeta Hydrological Laboratory in the Nantahala National Forest (35.052322 N, 83.452694 W) and a wildfire-impacted (WF) and a fire-excluded, partially harvested in 1986 (PH) watershed pair described by Caldwell et al. (2020) also located in the Nantahala National Forest (35.180510 N, 83.541525 W). Mean annual temperature in these locations is 12.8 °C and mean annual precipitation is 240 cm yr.−1, however, both temperature and precipitation vary with elevation (Coweeta Basin Monthly Average Temperature and Precipitation, 2023; Laseter et al., 2012). Vegetation is currently transitioning from xeric-hardwood forest to mesophytic species due to broad-scale fire exclusion and changes in precipitation patterns (Keiser et al., 2013; Laseter et al., 2012; McEwan et al., 2011), and includes hickories, oaks, red maple, tulip-poplar, great rhododendron, and mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia L.) as the dominant species (Caldwell et al., 2020; Miniat et al., 2021).

Figure 1

Watersheds from this study were located in southwestern North Carolina, United States. Nantahala Sites and Coweeta Sites are indicated by black dots within sub watershed units (12 digit hydrological unit codes) designated by the Watershed Boundary Dataset (Jones et al., 2022). Sub watersheds containing sites are shaded dark brown. Camp Branch (WF) and Upper Arrowwood (PH) are “Nantahala Sites” located ~20 km northwest of “Coweeta Sites” Watershed 31 (PF) and Watershed 32 (FE) in the Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory.

2.1.1 Coweeta hydrologic laboratory: prescribed fire sites

Watershed 31 (PF) is approximately 34 ha, east-facing, and ranges in elevation from 869 to 1,146 m a.s.l (Miniat et al., 2021; Ulyshen et al., 2022). It has been treated with three prescribed burns since 2019 (2019, 2021, 2023). Prior to the first burn, Rhododendron maximum and Kalmia latifolia (when present with R. maximum) were cut and slashed. R. maximum stumps were treated with herbicide (50% triclopyr amine; Garlon 3A®, DOWAgroSciences, Indianapolis, IN) and were left in the burn area. Conditions for the first prescribed burn (2019) were western winds blowing at 8 kph, relative humidity of 19%, and an air temperature of 15 °C. The burn was administered via aerial ignition. Of the three prescribed fires administered in Watershed 31, this ignition yielded the highest intensity due to higher fuel loads that were introduced through the cutting of R. maximum and K. latifolia. The second prescribed fire (2021) was conducted via hand ignition during 6–8 mph winds, relative humidity of 25%, and an air temperature of 18 °C. This burn reduced leaf litter by approximately 0.37 kg/m2 throughout the watershed. In 2023, the third burn was implemented in March by hand ignition with light and variable wind conditions, relative humidity of 23–31%, and ambient temperature ranging from 6.6–11.1 °C. Less fuels were observed in open or south-facing areas prior to the burn. Short bursts of head fire were used to ensure burn objectives were met. Watershed 32 (FE) is an adjacent, undisturbed reference site (41 ha) that has had no known fires since at least 1927, is similarly east-facing, and ranges in elevation from 920 to 1,236 m a.s.l (Miniat et al., 2021). Soils in both watersheds are predominantly characterized by cobbly sandy clay loam to fine sandy loam, with soils of the Evard-Cowee complex, Tuckasegee-Whiteside complex, Edneyville-Chestut complex, Cullasaja-Tuckasegee complex, and Plott series (Soil Survey Staff, 2024; Supplementary Data).

2.1.2 Nantahala National Forest: wildfire study sites

The Camp Branch Fire was a wildfire that burned 1,310 ha within the Nantahala National Forest in October 2016. The wildfire was most severe in the upper northwestern corner of the Camp Branch watershed. This upper portion of Camp Branch watershed (WF) is southeast facing, has a mean slope of 64%, and ranges in elevation from 1,185 to 1,628 m a.s.l (Caldwell et al., 2020). The wildfire completely consumed the soil O horizon in this area. Upper Arrowwood (PH) is a watershed 5 km to the east, approximately 976–1,230 m a.s.l in elevation, with a mean slope of 51%, and is southeast facing (Caldwell et al., 2020). It has evidence of skid roads and harvesting within the past century, a history of fire exclusion, and areas that were partially harvested in 1986. Ericaceous shrubs were noticeably absent from areas sampled in this study. Soils in both watersheds are classified as gravelly loam to gravelly fine sandy loam, with soils of the Cleveland-Chestnut-Rock outcrop complex, and Evard-Cowee complex (Soil Survey Staff, 2024; Supplementary Data).

2.1.3 Soil sampling

During the summer of 2023, 12 plots were established in PF and FE and 6 plots in WF and PH. Plots were 4 × 4 m and located in areas identified to have the highest burn severity in PF and WF (Caldwell et al., 2020). Corresponding plots were established to match aspects in the paired watershed. We collected five soil cores (3.8 cm diameter) from each plot, one from the plot center and one from each corner. Cores included up to 10 cm of the O horizon if present and 10 cm of the mineral soil below. Samples were composited by plot and horizon into sterile WhirlPak™ bags, transported to the lab on ice, and stored at 4 °C. All samples were homogenized and sieved to 4 mm. Soil subsamples for each plot and layer were taken and stored in sterile 15 mL falcon tubes at −20 °C within 24 h of collection for enzyme assays and DNA extraction.

2.2 Soil chemical and physical properties

A subsample of soil was dried in an oven for 24 h at 105 °C to determine gravimetric water content. Soil pH was determined by Sension+ 5,014 T pH probe (Hach company, Loveland, CO, United States) by creating a 1:1 slurry of soil and DI H2O. Dissolved inorganic N (NO3− and NH4+) was determined by extracting soils in a 1:5 soil to 2 M KCl ratio for 1 h. Extracts were run on Lachat QuikChem flow injection analyzer (Hach Company, Loveland, CO, United States). A subsample of soil was dried at 60 °C for 24 h and milled into a fine powder for total C (TC), organic C (SOC), and N (TN). SOC samples were acid fumigated with concentrated HCl to remove inorganic C and dried at 60 °C. TC, SOC, and TN samples were measured at the University of Kansas Soil Analyses Services Center on a Thermo FlashSmart Elemental Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA United States). Microbial biomass C (MBC) and N (MBN), dissolved organic C (DOC), dissolved organic N (DON), and total dissolved N (TDN) were measured by the chloroform fumigation extraction method (Vance et al., 1987) using 0.5 M K2SO4 extracts (1:5 soil:solution) and run on an Elementar vario cube TOC/TN (Elementar Americas Inc., Mt. Laurel, NJ, United States). Briefly, each sample was run unfumigated (DOC, DON) and fumigated (MBC, MBN). Fumigated samples were placed in a vacuum desiccator lined with wet paper towels and a beaker containing ethanol-free chloroform and boiling chips. Samples were fumigated for 24 h in the dark. Microbial biomass calculations did not include a correction factor. All processes were performed on mineral soil samples; gravimetric water content, pH, TC, and TN were measured for organic layer samples and can be found in Supplementary Figure S1. Data is available through the Environmental Data Initiative (Snyder and Barrett, 2025).

2.3 Soil microbial community composition

DNA was extracted from ~0.25 g of soil with DNeasy PowerSoil kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) and quantified with a Qubit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Inc., Waltham, MA, United States). We analyzed mineral and organic soil bacterial communities and mineral soil fungal communities. For bacterial communities, we targeted the V4 region of 16S rRNA gene with primers 515F/806R for PCR amplification and sequencing (Caporaso et al., 2011; Parada et al., 2016). 16S library preparation was performed at the Duke Microbiome Core Facility. The fungal community library was prepared targeting the ITS region with the ITS1F/ITS2 primer pair (Bellemain et al., 2010) using the Earth Microbiome Project protocol (Smith et al., 2018). Amplicon sequencing for both 16S and ITS was performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform using 251 bp paired-end reads at Duke Sequencing and Genomic Technologies facility and were returned demultiplexed. Raw sequences are deposited in NCBI’s BioProject database under project #PRJNA1213841. DADA2 was utilized for joining paired end reads, filtering, learning error rates, and removing chimeras (Callahan et al., 2016). Taxonomy was assigned to amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) with the SILVA (138.1) and UNITE (10.0) databases for bacteria and fungi, respectively. An average of 57,738 reads were retained per sample for 16S and 94,669 for ITS. After filtering for mitochondrial and chloroplast sequences for 16S and phylum with low prevalence (<10), 28,494 taxa remained for 16S reads in mineral and organic soil and 6,967 for ITS in mineral soil.

Fungal trophic strategies and guilds were assigned to ITS ASVs using the FungalTraits (Põlme et al., 2020; Tanunchai et al., 2023) database. Percent abundance of each functional category per sample was calculated based on the relative abundance of ASVs. We compared the relative abundances of ectomycorrhiza, arbuscular mycorrhiza, and soil saprotrophic fungi across watersheds. Ectomycorrhiza can have slower C cycling rates and are known to dominate temperate forested ecosystems due to their association with oak and hickory vegetation (Averill and Hawkes, 2016; Phillips et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2005). They typically compete with free living soil fungi for N and are associated with lower abundances of saprotrophs (Eagar et al., 2022). Growing evidence points to ectomycorrhiza dominated systems becoming less resilient to fire following fire exclusion (Carpenter et al., 2021). In contrast, arbuscular mycorrhizae dominated systems are associated with higher SOC turnover, a higher abundance of saprotrophs relative to ectomycorrhiza dominated soil communities, and trees with more labile litter (Eagar et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 2013).

2.4 Microbial ecosystem function

2.4.1 Microbial extracellular enzyme analysis

We estimated extracellular enzyme activity (EEA) for all mineral soil samples. Hydrolytic enzymes included β-1,4-glucosidase (BG), β-1,4-xylosidase (XYL), and β-D-cellobiosidase (CHB) for C acquisition, and β1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) for N acquisition. Oxidative enzymes included phenol oxidase (POX) and peroxidase (PER) for lignin degradation. EEA was measured with modified fluorometric assays and colorimetric assays for hydrolytic and oxidative enzymes, respectively (Saiya-Cork et al., 2002). Approximately 0.5 g of sample was homogenized in 125 mL of a 50 mM sodium acetate buffer adjusted to a pH of 5. Incubation period varied based on enzyme: 2 h for NAG; 3 h for BG, CHB, and LAP; and 18 h for oxidative enzymes. For hydrolytic enzymes, the slurry was pipetted into black 96-well microplate containing substrates fluorescently labeled with 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin for LAP enzyme activity or 4-methylumbelliferone for all other enzymes. Fluorescence was measured using a Tecan Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Mannedorf, Switzerland) at 365 nm excitation and 450 nm emission wavelengths. Each well received 10 μL of 0.5 N NaOH 1 min before reading fluorescence for all hydrolytic enzymes except LAP. For oxidative enzymes, the soil slurry was loaded onto a clear 96-well microplate containing 25 mM 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine and either DI H2O (POX) or 0.3% H2O2 (PER). Activity was measured at wavelength 460 nm. Enzyme activities were calculated per g of dry soil and mg of MBC.

2.4.2 C and NH4-N mineralization rates

We followed procedures described in Osburn et al. (2021a) to measure C mineralization rates and net NH4 mineralization rates. We focused on NH4 mineralization rates over total N mineralization, as 72.2% of KCl extractable NO3− values were below the MDL. For C mineralization rates, we measured ~5–6 g of dry weight equivalent mineral soil into 50 mL falcon tubes fitted with rubber septa caps. Tubes were flushed of CO2 and incubated for 24 h at room temperature and measured for CO2 build-up with an infrared gas analyzer (Li-7000; Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, Nebraska, United States). For NH4 mineralization rates, we extracted DIN with 100 mL of 2 M KCl on two replicates of 20 g of soil prior and post a 24 h incubation period at room temperature. NH4 mineralization replicates were averaged by plot. All rates were calculated per g of dry soil per h and qCO2 and qNH4 to account for MBC.

2.5 Statistical analyses

2.5.1 Soil biogeochemical and physical properties

All statistical analyses were performed using R programming language (v4.4.1) (R Core Team, 2024). Soil physicochemical properties, life strategies, and microbial functions were analyzed using linear models across watersheds and additive models accounting for watershed and elevation. Both models were used because fire activity in this region is known to be more severe on upper slopes and ridges (Reilly et al., 2022). Elevation can have direct effects on both soil biogeochemical characteristics and fire severity (Coates and Ford, 2022; Garten, 2004; Garten et al., 1999; Knoepp et al., 2018; Reilly et al., 2022). Thus, it was difficult to examine the influence of fire on soil microbial communities and biogeochemistry without considering the interactions between fire and elevation. As our wildfire site was higher in elevation than all other watersheds, there was more uncertainty in model comparisons between WF and other watersheds when we accounted for elevation. For this reason, we included models that examined significant differences across watersheds with and without accounting for elevation. We determined model fit with QQ plots generated with the Dharma (v4.6) and performance (v12.6) packages (Hartig, 2022; Lüdecke et al., 2021). When models did not meet normality of residuals, we used generalized linear models with gamma distribution and log link function. We used Pearson correlation to determine soil properties that had a linear relationship with MBC and SOC (Supplementary Figure S2). To determine the best model to predict MBC and SOC in this environment, we used AICc (R package AICcomodavg) with additive linear models using correlated soil properties, including models that account for elevation and watershed (Mazerolle, 2023). Best fitting models were selected based on AICc and R2 values. We tested for significance of watershed with the R package emmeans (v1.10.4) using the Tukey method of multiple comparisons. Model predictions were visualized with original data points overlaid.

2.5.2 Soil microbial community structure

Microbial community analyses were performed utilizing the vegan (2.6–8), phyloseq (v1.48.0) and microeco (v1.9.1) packages in R (Liu et al., 2021; McMurdie and Holmes, 2013; Oksanen et al., 2024). Bray-Curtis distances between ASV abundances normalized by total sum scaling in the watersheds were used for multivariate analyses. Bray-Curtis distances of watershed communities were visualized with non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plots. PERMANOVA was utilized to calculate the magnitude of all watershed community differences by soil layer and kingdom and ANOVA to determine significant differences between relative abundance of taxa between watersheds. We used distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) to visualize variation in mineral soil bacterial and fungal communities over the observed range in environmental variables. Environmental variables were standardized prior to analysis. To reduce collinearity among predictors, we chose to include pH, C: N, DOC, NH4+, moisture, and elevation, and examined linear dependencies by calculating the variance inflation factor using the vif.cca function in R package vegan. Predictors were scaled to zero mean unit variance prior to analysis. The dbRDAs were tested using Monte Carlo permutation tests. Predictors were included as vectors via the envfit function of R package vegan to demonstrate the variables’ associated strength with ordination axes through multiple regression.

2.5.3 Microbial ecosystem multifunctionality

In addition to examining individual process rates, an ecosystem multifunctional approach can help elucidate how these processes work in combination (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2020). This is useful when representing rates per soil MBC to compare how efficiently resources are being utilized across ecosystem types or similar ecosystems with disturbances (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2020; Osburn et al., 2021a; Wu et al., 2023). Microbial ecosystem functions (qCO2, qNH4, MBC weighted EEA) were analyzed using principal components analysis (PCA) with the prcomp function and visualized using the ggfortify package (v4.17) to determine relationships in functionality across watersheds (Horikoshi and Tang, 2016). Prior to analysis, Z scores were calculated for each sample by function. Sample multifunctionality index was calculated following the methods of Maestre et al. (2012) by averaging scaled functional data across samples. PCA was visualized with the ellipse function in ggplot2 (v3.5.2), with a confidence interval set to 0.95. PC axes 1 and 2 were correlated with original functional data and physicochemical properties to contextualize relationships. We used PERMANOVA on the Euclidean distance matrix calculated from ecosystem function data to determine the difference in soil microbial community functionality across watersheds.

3 Results

3.1 Soil chemical and physical properties

Nitrogen availability was highest in the partially harvested (PH) watershed, followed by the wildfire impacted (WF) site, and the prescribed burned site (PF). This is reflected by the lowest mean DOC (304.62 ± 25.13 μg g dry soil−1), and highest pH (5.52 ± 0.28) and NO3− (1.83 ± 1.38 μg g dry soil−1) values. In addition, PH had the lowest ratio of C to N pools (17.31 ± 1.38). Differences in C: N were higher in FE relative to PF, and highest in CB when accounting for elevation (Supplementary Figure S1; Supplementary Data). While mean MBC was the highest in WF (339.50 ± 39.03 μg g dry soil−1), it was not significant when accounting for elevation in the model. PF (281.15 ± 19.99 μg g dry soil−1; p = 0.0277) and FE (278.37 ± 14.59 μg g dry soil−1; p = 0.0271) had higher MBC than PH (207.27 ± 17.03 μg g dry soil−1). Mean TC values were also highest in WF (80.37 ± 8.90 μg g dry soil−1), but only significant when not accounting for elevation (Table 1). The PF watershed had higher N availability compared to FE in the form of TDN (33.83 ± 1.89 μg g dry soil−1, 25.53 ± 1.96 μg g dry soil−1 respectively; p = 0.0137) and DON (31.76 ± 1.77 μg g dry soil−1, 23.98 ± 1.81 μg g dry soil−1 respectively, p = 0.0085), which resulted in a lower ratio of DOC: TDN (12.63 ± 0.50, 15.24 ± 1.07 respectively; p = 0.0217). MBN was also significantly higher in PF (57.23 ± 3.68 μg g dry soil−1; p = 0.0407), and the MBC: MBN was significantly higher in FE (5.81 ± 0.35; p = 0.0072). Organic layer differences in TC and TN were not systematically different between or among watershed pairs.

Table 1

| Property | PF | FE | WF | PH | ~Watershed + Elevation | ~Watershed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.74 (0.04) | 4.84 (0.08) | 5.03 (0.12) | 5.52 (0.28) | – | (31/PH)*** (32/PH)** |

| Moisture g g dry soil−1 | 0.486 (0.02) | 0.441 (0.02) | 0.707 (0.05) | 0.454 (0.06) | – | (31/WF)*** (32/WF)*** (WF/PH)*** |

| NO3 μg g dry soil−1 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.04 (0.02) | 1.83 (1.38) | † | † |

| NH4 μg g dry soil−1 | 2.04 (0.22) | 1.53 (0.21) | 2.48 (0.45) | 1.75 (0.13) | – | – |

| DOC μg g dry soil−1 | 420.00 (14.98) | 369.08 (12.77) | 464.80 (44.69) | 304.62 (25.13) | – | (31/PH)** (32/WF)* (WF/PH)*** |

| TDN μg g dry soil−1 | 33.83 (1.89) | 25.53 (1.96) | 39.53 (2.48) | 38.38 (2.76) | (31/32)* | (31/32)* (32/WF)*** (32/PH)** |

| DOC: TDN | 12.63 (0.50) | 15.24 (1.07) | 11.63 (0.54) | 8.10 (0.84) | (31/32)* (32/PH)* (WF/PH)* | (31/PH)** (32/WF)* (32/PH)*** |

| DON μg g dry soil−1 | 31.76 (1.77) | 23.98 (1.81) | 36.98 (2.25) | 34.80 (1.84) | (31/32)** | (31/32)* (32/WF)*** (32/PH)** |

| TN mg g dry soil−1 | 1.99 (0.11) | 1.68 (0.15) | 3.83 (0.53) | 3.61 (0.66) | (32/PH)* | (31/WF)** (31/PH)** (32/WF)*** (32/PH)*** |

| TC mg g dry soil−1 | 53.77 (2.97) | 43.60 (2.12) | 80.37 (8.90) | 58.88 (8.01) | – | (31/WF)** (32/WF)*** (WF/PH)* |

| OC mg g dry soil−1 | 45.05 (2.76) | 38.38 (2.027) | 63.13 (7.53) | 46.57 (6.77) | – | (31/WF)* (32/WF)*** |

| C: N | 27.25 (1.08) | 27.11 (1.80) | 21.45 (0.87) | 17.31 (1.38) | (WF/PH)** | (31/PH)*** (32/PH)*** |

| MBC μg g dry soil−1 | 281.15 (19.99) | 278.37 (14.59) | 339.50 (39.03) | 207.27 (17.03) | (31/PH)* (32/PH)* | (WF/PH)** |

| MBN μg g dry soil−1 | 57.23 (3.68) | 49.78 (4.18) | 59.47 (8.07) | 48.38 (3.88) | (31/32)* (31/WF)* (31/PH)** | – |

| MBC: MBN | 4.92 (0.14) | 5.81 (0.35) | 6.00 (0.51) | 4.33 (0.30) | (31/32)** (31/WF)** (32/WF)* (WF/PH)** | (32/PH)* (WF/PH)* |

| Soil saprotroph abundance | 18.21 (5.51) | 11.03 (1.79) | 23.69 (3.81) | 25.51 (5.19) | – | – |

| Ectomycorrhiza abundance | 65.99 (5.61) | 63.14 (5.53) | 38.47 (8.50) | 42.11 (12.88) | – | – |

| Arbuscular mycorrhiza abundance | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.01 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.01) | † | † |

Mean physicochemical and microbial properties measured for each watershed.

Values are listed with standard error in parenthesis. Significant differences between watersheds using Tukey method of comparing four estimates from linear model outputs are indicated: *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001. †72% of NO3 values were below MDL (13 μg/L for WF and PH, 14.2 μg/L for PF and FE) per g of dry soil. NO3 and Arbuscular mycorrhiza data do not meet assumptions for glm.

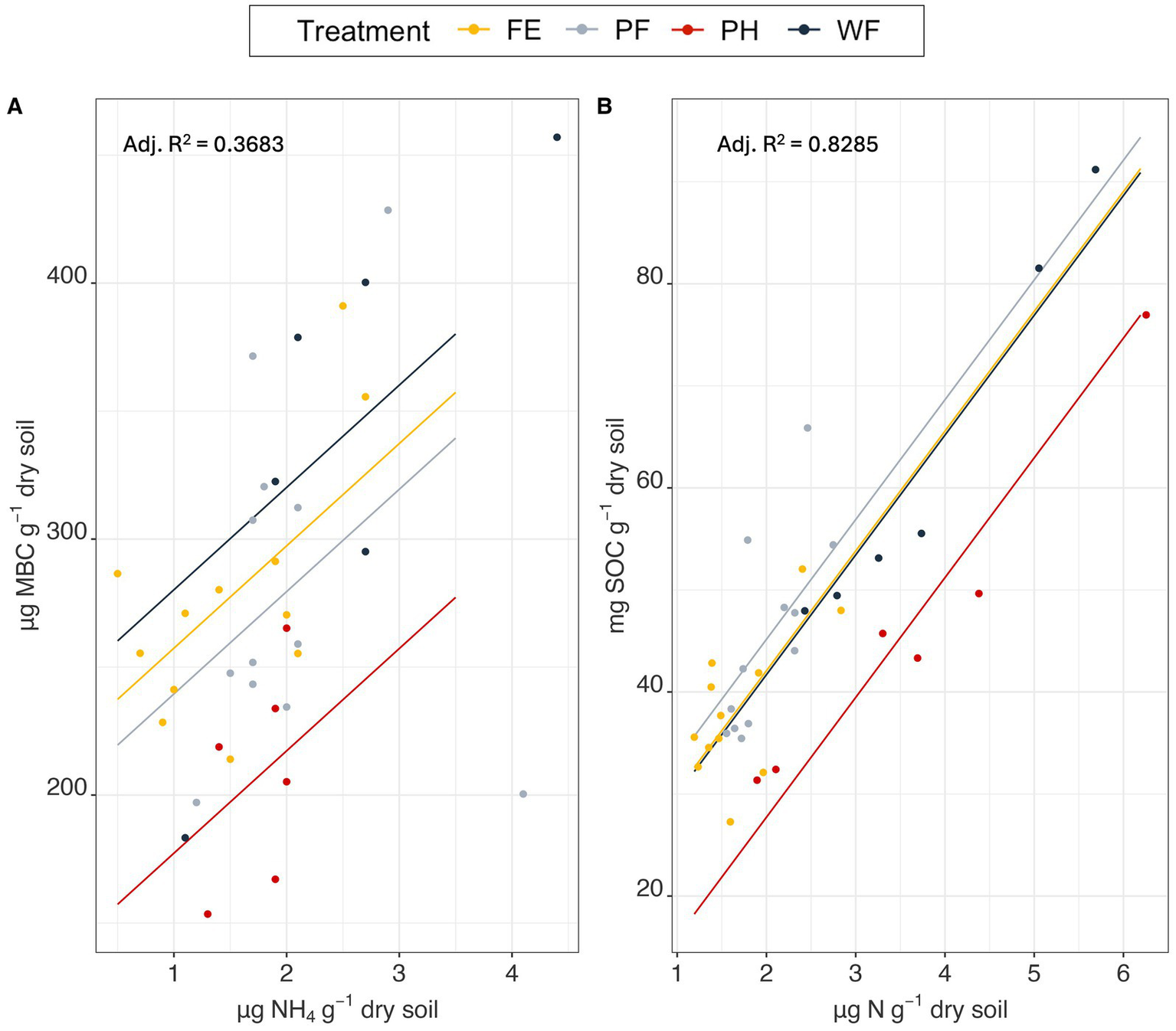

The additive effects of NH4+ and watershed created the best fitting model for MBC (AICc weight = 0.40, adj. R2 = 0.3683, p = 0.001; Figure 2A), followed by DOC (AICc weight = 0.22, adj. R2 = 0.2532, p = 0.001; Supplementary Table S1). Both NH4 (p = 0.00564) and watershed (p = 0.02552) were significant predictors of MBC using ANOVA. PH had significantly lower estimated means than FE (p = 0.0478) and WF (p = 0.0300). SOC was best explained by the additive effects of TN and watershed (AICc weight = 0.69, adj. R2 = 0.8285, p = 2.928e-12; Figure 2B), followed by moisture + watershed (AICc weight = 0.21, adj. R2 = 0.8166, p = 8.164e-12; Supplementary Table S2). Both TN (p = 3.561e-13) and watershed (p = 0.0001) were significant predictors of SOC using ANOVA. PH had significantly lower estimated mean SOC from all other watersheds (p < 0.003) using Tukey HSD test.

Figure 2

Linear model of soil MBC levels in response to NH4 with watershed treatment as an additive predictor (A), and SOC levels in response to TN with watershed as an additive predictor (B). Original sample data was overlayed on predictions as points.

3.2 Soil microbial community composition

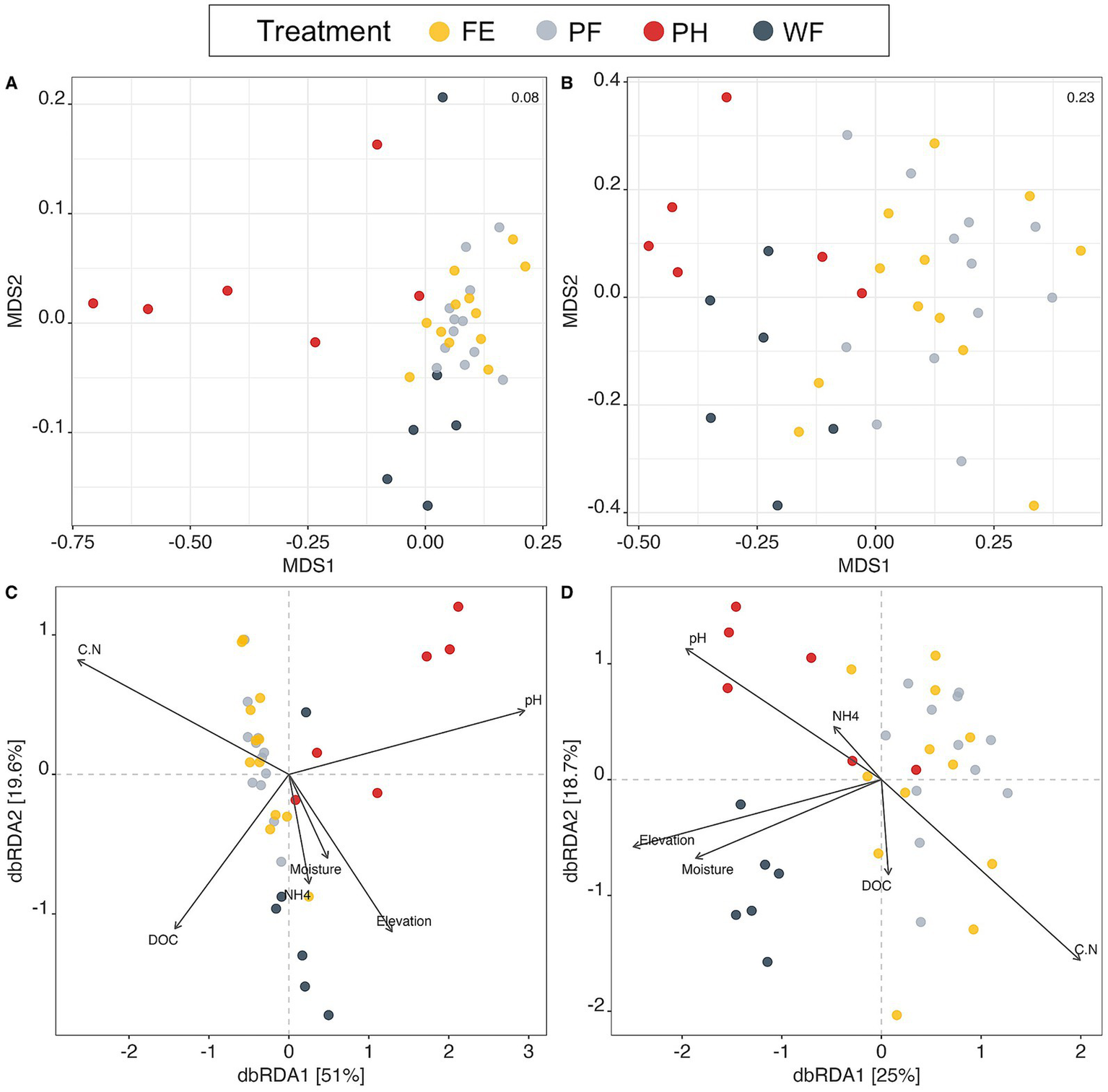

Watershed microbial communities were significantly different from one another, except for both PF and FE mineral soil bacterial and fungal communities (PERMANOVA p < 0.03; Figure 3; Supplementary Tables S3, S4; Supplementary Figure S4). Environmental variables used to construct a dbRDA explained 41.76% of the variation in bacterial communities and 19.23% of the variation in fungal communities (Figure 3). Moisture, pH, NH4+, elevation, and C: N were significant for bacterial community structure (p < 0.04), with the strongest contributions determined by envfit vectors pH, elevation, and C: N (Supplementary Table S5). Significant predictors of fungal community structure included pH and moisture (p < 0.01) with the strongest vector contributions from pH, elevation, and C: N (Supplementary Tables S5, S6). We note that because this is a constrained ordination, variables were included in the creation of axes and, therefore, envfit vectors may have inflated significance values but are still useful for visualizing variables that influence community structure. Bacterial communities from PF and FE were influenced by C: N ratio, where WF communities were structured by NH4+ and elevation, and PH by pH (Figure 3B). Similar to bacterial communities, fungal communities were influenced by C: N in PF and FE, elevation and moisture in WF, and pH in PH (Figure 3D).

Figure 3

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) and distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) using Bray-Curtis distances of both bacterial communities using 16S ASVs (A,B) and fungal communities using ITS ASVs (C,D) on watershed treatments (prescribed fire; PF, fire excluded; FE, wildfire; WF, partial harvested; PH). PERMANOVA on Bray-Curtis distances between watersheds determined that all watershed communities were significantly different from one another (p ≤ 0.003) except for PF and FE bacterial (p = 0.5350; A) and fungal (p = 0.7430; B) communities. 44.7% (C) and 22.2% (D) of community variance is constrained by environmental variables in dbRDA plots. Significant predictors of bacterial communities include moisture, pH, NO3−, elevation, and C: N (C) and pH and moisture for fungal communities (D); see Supplementary Tables S5, S6 for statistical results. Environmental variables for analysis were selected to reduce collinearity.

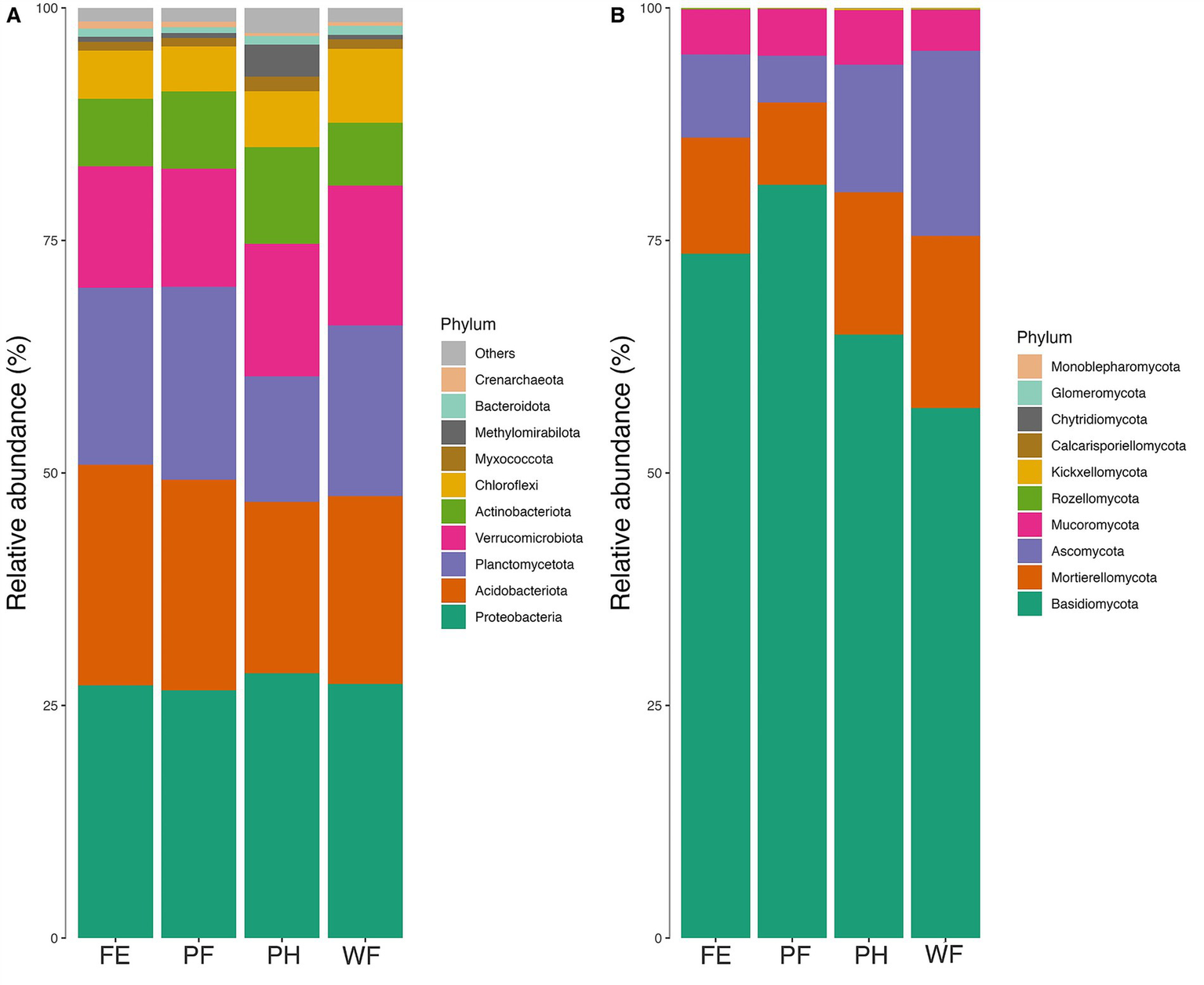

When comparing the relative abundances of mineral soil bacteria phyla across watersheds, Planctomycetota were lowest in PH plots, while Actinobacteria and Methylomirabilota—denitrifying methanotrophs—were elevated compared to the other watersheds (Figure 4A). Soil communities in the organic layer supported higher relative abundance of Acidobacteria in FE and Actinobacteria in PF and PH (Supplementary Figure S3). The elevated abundance of Actinobacteria in PF organic soil was likely in response to the stress of the recent fire treatment. Regarding mineral soil fungal communities, Mortierellomycota was elevated in WF relative to other watersheds (Figure 4B). Soil saprotrophs were significantly higher in PF than FE when accounting for elevation (p = 0.0474). Ectomycorrhizal abundance was significantly lower in WF than PF and FE, but this was no longer true when accounting for elevation (Table 1). Arbuscular mycorrhizae sequences were highest in PH (Table 1).

Figure 4

Mean relative abundance of the top ten bacterial phyla (A) and fungal phyla (B) in mineral soil samples across watershed treatments (prescribed fire; PF, fire excluded; FE, wildfire; WF, partial harvested; PH). Significant differences between phyla in across watersheds can be found in Supplementary Table S7.

3.3 Microbial ecosystem function

Microbial functions expressed as activity per g of dry soil and activity per mg of MBC responded to soil physical and chemical changes following land management or disturbance type (Supplementary Figures S5, S6). POX activity per mg of microbial biomass was significantly higher in PH soils (30.09 ± 5.10 μmol POX mg−1 MBC h−1) than all other watersheds. LAP activity was significantly higher in PH soils (103.20 ± 15.9 nmol LAP mg−1 MBC h−1) than WF (40.64 ± 6.02 nmol LAP mg−1 MBC h−1) and PF (58.97 ± 7.08 nmol LAP mg−1 MBC h−1) and significantly higher in PF soils relative to FE (34.40 ± 5.69 nmol LAP mg−1 MBC h−1). BG activity was significantly lower in PF (1018.10 ± 147.96 nmol BG mg−1 MBC h−1) and FE (814.40 ± 170.16 nmol BG mg−1 MBC h−1) soils relative to PH (1901.80 ± 348.62 nmol BG mg−1 MBC h−1). WF (2.82 ± 0.31 μg CO2 g−1 dry soil h−1) had the highest mean C mineralization rate while FE (1.65 ± 0.13 μg CO2 g−1 dry soil h−1) had the lowest, although there was not a statistically significant difference between any of the watersheds. When comparing qCO2 across watersheds, PH had the highest mean (9.71 ± 0.83 μg CO2 mg−1 MBC h−1) and was significantly higher than FE (6.0842 ± 0.54 μg CO2 mg−1 MBC h−1). Mean net NH4+ mineralization and qNH4 values were negative for PH (−0.20 ± 0.15 μg NH4 g−1 dry soil h−1; −0.63 ± 0.50 μg NH4 mg−1 MBC h−1) and PF (−0.07 ± 0.13 μg NH4 g−1 dry soil h−1; −0.18 ± 0.38 μg NH4 mg−1 MBC h−1), indicating nitrification or net immobilization of NH4+ (Supplementary Figures S5, S6). Direct observation of ecosystem functions across watersheds supports increased C turnover in PH when expressed per unit of MBC.

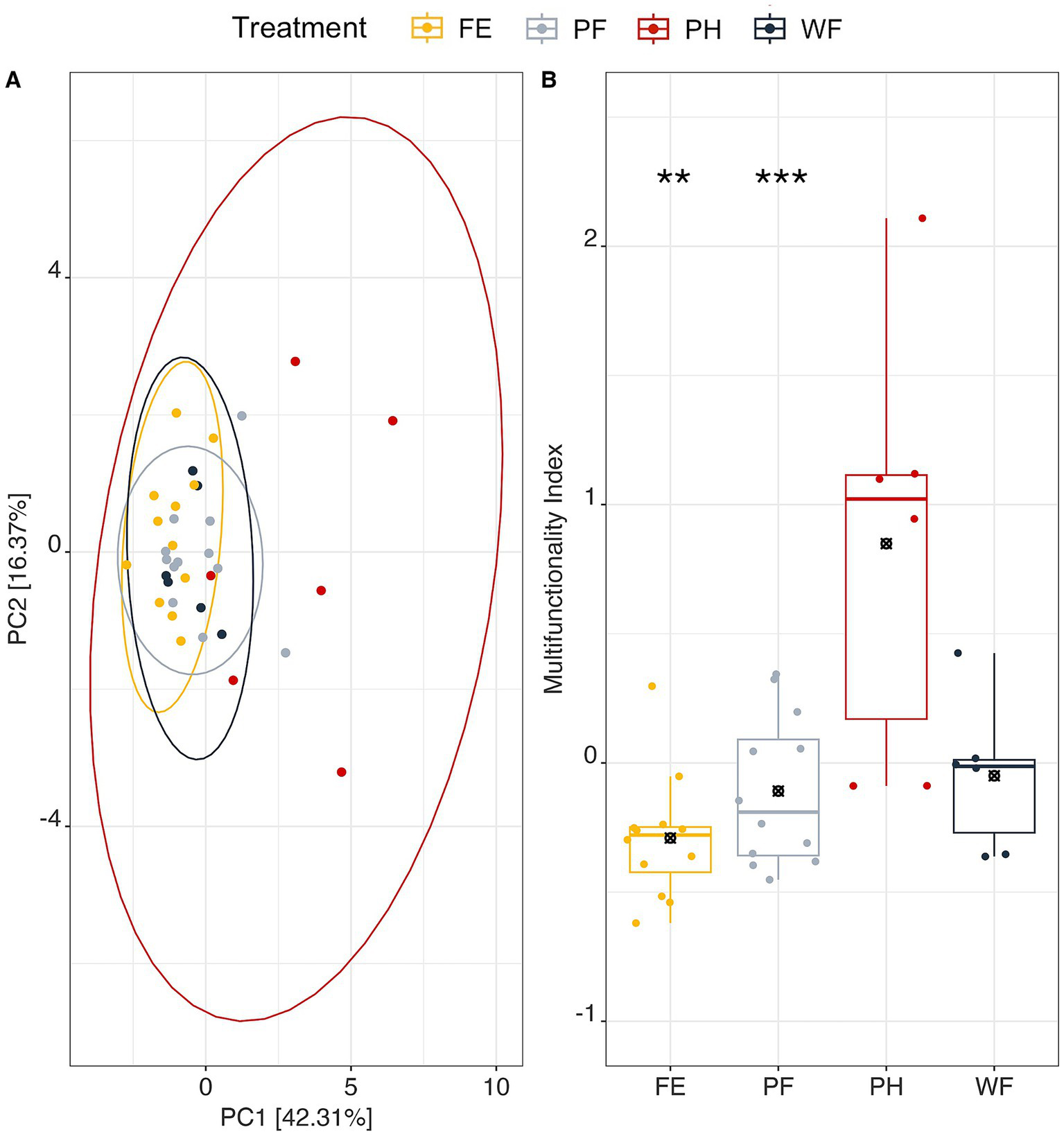

PCA of ecosystem functions resulted in two axes collectively explaining 58.68% of the variation in the data (PC1-42.31% and PC2-16.37%) (Figure 5A). PC1 was positively correlated with BG, CHB, LAP, POX, and qCO2 activity. PC2 was negatively correlated with PER activity (Figure 5A; Supplementary Tables S9, S10). PERMANOVA results indicated that watersheds function differently from one another (p = 0.001), however, the multifunctional index demonstrates that PH multifunctionality was significantly greater than PF and FE when accounting for elevation (Figure 5B). PH multifunctionality index was greater than all three other watersheds when not accounting for elevation. This corresponds with PH separating from the other watersheds in ordination space within the PCA, in relation to higher C acquisition enzyme activity (BG, CHB, LAP, POX) and metabolic quotient. Correlation of PC axes with physicochemical data suggests that these functional differences are related to pH and N availability [DOC: TDN along PC1 (r = −0.68); and pH (r = 0.73), NO3− (r = 0.65), and TN (r = 0.56)].

Figure 5

Principal components analysis of microbial ecosystem functions (extracellular enzyme activity (EEA) corrected for microbial biomass carbon, qCO2, qNH4) across watershed treatments accounting for 58.68% of the variation in multifunctionality. Ellipse shows 0.95 level of confidence. PERMANOVA on Euclidean distances between watershed functions are significant (p = 0.001). PC1 is correlated with BG(+), CHB(+), POX (+), qCO2 (+), LAP(+). PC2 is correlated with PER(−). (A) Multifunctionality index of each watershed with mean and significant differences from partially harvested watershed (PH) indicated *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, all other watershed multifunctionality indices were not significantly different from one another (Supplementary Data). Represented significant values account for elevation (B), however, PH multifunctionality is significantly different from all watersheds when elevation is not included in the model.

4 Discussion

4.1 Resource availability drives soil microbial multifunctionality

Examining ecosystem multifunctionality enables comparisons of microbial contribution to nutrient cycling dynamics across watersheds and landscapes (Delgado-Baquerizo et al., 2020). The use of the metabolic quotient (qCO2) and microbial biomass-specific NH4+ mineralization rate (qNH4) can indicate microbial effort to cycle key nutrients (Lu et al., 2024; Wardle and Ghani, 1995). By examining these rates with MBC weighted EEA, we sought to describe microbial driven ecosystem processes across watersheds. This can potentially determine if processes are attributed to biomass effects or resource limitation (Allison et al., 2011; Osburn et al., 2018). While the prescribed fire watershed (PF) and the fire excluded watershed (FE) did not have distinct microbial communities from one another, PF had more available N as evidenced by lower DOC: TDN ratios and a higher proportion of N in microbial biomass, or MBN (Table 1). Rafie et al. (2024) determined that low intensity burns in Southern Appalachian mixed-hardwood forests also had increased soil organic N, supporting these findings, although sites were clearcut prior to burning. MBN is a biologically active pool of N (Deng et al., 2000), suggesting activation of microbial communities in response to nutrients released from prescribed burns (Osburn et al., 2018). LAP activity was also higher per MBC in PF than FE. LAP hydrolyzes leucine from peptides within the soil and higher LAP activity was consistent with increased organic N acquisition. A microbial response to greater availability of N was also supported by net negative mean NH4+ mineralization in PF, potentially indicating immobilization of NH4+, in contrast to the net positive mean rate in the unburned FE. NH4+ was higher in PF compared to FE, which has been seen in long-term prescribed burn effects in the area (Knoepp et al., 2004). Together these results illustrate enhanced N cycling in PF soils, while FE soils exhibited the greatest N limitation.

Soils within the partially harvested watershed (PH) had the highest N availability and pH of all the watersheds (Table 1). High N availability in PH is consistent with C limitation. PH had the lowest DOC and MBC of all the watersheds and the highest rate of C acquisition enzyme activity. Mean microbial biomass was higher in the wildfire impacted watershed (WF) than PH and significantly higher in PF and FE than PH. In conjunction, qCO2 was lowest in FE and significantly higher in PH than FE. Our results indicate that microbes in PH could be scavenging for SOC with extracellular enzymes (Sinsabaugh et al., 2009) and using it less efficiently than the other watersheds. This supports previous work that found that ecosystem function was driven by microbial properties, resource availability, and microbial community membership in watersheds affected by logging (Osburn et al., 2021a); and patterns found in disturbed watersheds in this region (Keiser et al., 2016). This was also evidenced by linear model predictions of MBC and SOC—despite availability of N in PH, the constraint of C loss from disturbance may impact efficiency of C cycling. WF and FE had significantly higher MBC than PH, and all three watersheds exhibited significantly higher SOC than PH. MBC has been found to be constrained by N availability in previous studies (Hartman and Richardson, 2013). Our results support this but also indicate it is likely dependent on the ecosystem land-use history and the availability of other resources (Supplementary Table S1).

LAP activity was also elevated in watershed PH. LAP can be positively related to soil pH and negatively related to inorganic N availability (Uwituze et al., 2022). The increase in pH from disturbance was not only important for microbial community structure but potentially encouraged hydrolytic enzyme activity relative to the other watersheds. Severe wildfire effects have been documented to increase C acquisition activity due to combustion of SOC (Knelman et al., 2015). This did not seem to be the case for WF after 7 years, although variability in PH data made BG and CHB activity not significantly different when accounting for elevation. Other potential effects that caused higher qCO2 and enzyme acquisition activity include elevation (Feng et al., 2021). This limited our ability to parse fire effects from activity levels across watersheds, as elevation models increased uncertainty around WF values.

4.2 Soil microbial community structure is influenced by land use or disturbance history

This study supports the assertion that microbial community structure is strongly influenced by land-use legacy effects. Timescales are an important consideration when comparing these watersheds as they have experienced varying times since disturbance. As we did not have samples for the wildfire site on the same time scale following the prescribed burn, we were unable to compare the impacts of prescribed burning vs. wildfire on soil based on time since disturbance. Rather, we provided context of long-term effects of wildfire to the rest of the watersheds used in this study.

Despite increased organic N availability within PF in comparison to FE, mineral soil microbial communities—both bacterial and fungal—did not significantly vary in response to repeated low severity prescribed fires. This was consistent with previous studies that examined the response of soil communities following low to moderate severity prescribed fire and wildfire (Brown et al., 2019; Kranz and Whitman, 2019; Osburn et al., 2018). Short-term biogeochemical changes in response to prescribed fires did not influence bacteria taxonomic diversity at time of sampling. Instead, both PF and FE communities were structured by soil C: N ratio (Figure 3C). The prescribed burning treatment did not affect bulk soil C: N ratios, consistent with previous findings (Knoepp et al., 2004).

Fire severity has been shown to impact microbial community composition in other regions and studies (Adkins et al., 2022; Dove et al., 2022; Nelson et al., 2022; Whitman et al., 2019). Wildfires in this region have exhibited variable effects on soils due to pre-existing soil conditions and fire severity (Brown et al., 2019; Dukes et al., 2020; Thompson et al., 2019). The Camp Branch wildfire of 2016 was classified as high severity in the area we sampled using tree mortality, soil organic layer loss, exposed mineral layer, bole char height, and basal area loss (Caldwell et al., 2020). Caldwell et al. (2020) described elevated export of nutrients in areas impacted by this severe wildfire, and while soil inorganic N levels were not significantly different between reference and burned watersheds, they increased with fire severity. Wildfire (WF) plots for this study were sampled approximately 7 years following the Camp Branch wildfire. Our results indicated that a combination of NH4+ availability, moisture, and elevation influenced microbial community structure 7 years following wildfire. Dove et al. (2022) found microbial selection processes due to environmental filters following wildfire increase over time since fire occurrence in a Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) dominated forest, which may be applicable to this system. WF had the highest mean NH4+ at the time of sampling (2.48 ± 0.45 μg g dry soil−1), which was shown in some studies to increase in soil following fire events (Agbeshie et al., 2022; Prieto-Fernández et al., 2004). When comparing watersheds with elevation excluded in the model, WF had significantly higher soil DOC concentration (464.80 ± 44.69 μg g dry soil−1) than unburned watersheds (FE = 369.08 ± 12.77 μg g dry soil−1; PH = 304.62 ± 25.13 μg g dry soil−1). While DOC was not a significant predictor of mineral soil community structure in this study, the availability of different fractions of C following fire (i.e., pyrogenic C) has been shown to influence microbial communities structure and function over time (Dove et al., 2022; Nelson et al., 2022). In the western United States, wildfire severity influenced the diversity and complexity of dissolved organic compounds in soil and microbial utilization decreased with complexity (Nelson et al., 2024; Roth et al., 2023). Future studies in this region should consider the characterization of dissolved organic compounds in combination with microbial response and time since fire.

It has previously been shown that bacterial community composition can be more sensitive to wildfire effects in Southern Appalachian forests than fungal communities (Brown et al., 2019). Our study demonstrated an importance of landscape characteristics (i.e., moisture and elevation) over soil chemistry on fungal community structure. Moisture is an important variable in the wildfire site in this study and can be attributed to many factors, including loss of overstory vegetation and consequently lower evapotranspiration rates (Dooley and Treseder, 2012). While we did not include vegetation in our analysis, elevation and plant species distribution are documented drivers of fungi functional group composition in Southern Appalachia (Kivlin et al., 2021; Veach et al., 2018). Fungal community assembly has been shown to be influenced by neutral processes, such as drift and dispersion, over environmental filters from different disturbance regimes in this region (Osburn et al., 2021b). However, there is also evidence for fire severity increasing beta diversity of ectomycorhizal fungi, with moderately burned areas sharing taxa with burned and unburned areas within the Great Smoky Mountains (Hughes et al., 2025).

PH had similar bacterial relative abundance patterns to clearcut watersheds from this region, with elevated Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria and lower Acidobacteria abundance (Figure 4A; Osburn et al., 2019). Land-use and pH are important for soil microbial metabolic efficiency in terrestrial and wetland soils, with a threshold of pH 5.5–6.2 toward less efficient C use and observed changes occur in community composition and diversity (Hartman and Richardson, 2013; Lauber et al., 2009; Malik et al., 2018; Wan et al., 2020). This is consistent with our findings from PH. PF had higher saprotrophs than FE, which was also found in previous literature on rhododendron removal and prescribed burning in this region (Osburn et al., 2021c). Microbial community assembly within disturbed watersheds is influenced more by selection than in “undisturbed” areas, which is driven more so by dispersal processes (Osburn et al., 2021b). The partially harvested watershed (PH) exhibited biogeochemical characteristics in plots consistent with watersheds that have been clearcut (elevated pH and NO3− export) (Osburn et al., 2019; Webster et al., 2016; Swank and Vose, 1997). This is reflected in the significant environmental influences on microbial community structure (Figure 3) and corresponds with observations of old skid roads during our time of sampling.

Ectomycorrhiza are typically more abundant in soil receiving low litter quality inputs, such as fire-adapted species like oaks and pines that produce higher C: N ratio litter. PF and FE mineral soils had the highest relative abundance of ectomycorrhiza and C: N ratios, and respective mean organic layer C: N ratios. WF had the lowest relative abundance of ectomycorrhiza. This site experienced complete canopy loss from the 2016 wildfire and was dominated by thick understory vegetation, including blackberries (Rhus spp.), fern spp., and R. maximum shrubs at the time of sampling. Previous work in this region determined that areas dominated by trees with ectomycorrhizal associations due to fire exclusion may result in higher tree mortality following a severe wildfire (Carpenter et al., 2021), and fungal load and mycorrhizal colonization can decline long-term without proper conditions to recover (Caiafa et al., 2023; Dove and Hart, 2017).

4.3 Implications for increased fire activity under global change

Wildfire activity is projected to increase in the southeastern US, stimulated by multiple and interacting environmental changes (e.g., drought, urbanization, and ongoing wildfire suppression) (Lafon et al., 2010.; Mitchell et al., 2014; Vose and Elliott, 2016). Regular prescribed burning is a management strategy employed in response to these changes to limit hazardous accumulations of fuels, reduce vertical and horizontal continuity of fuels, and achieve other management goals (Hubbard et al., 2004; Vose, 2000). This study determined that mineral soil microbial communities (bacterial and fungal) were resistant to the effects of prescribed fire, demonstrating stable community structure following low severity fire disturbance in this ecosystem. However, prescribed burning did result in higher mean C mineralization rates by 34.1% and higher mean LAP activity per microbial biomass by 71.4% relative to the fire excluded watershed. This indicated a functional response to fire due to more available organic N following low severity fire events. Pre-existing landscape history and heterogeneity complicates understanding the response of soil physicochemical properties to fire in this region (Dukes et al., 2020; Coates et al., 2010). The ongoing changes and interactions of these environmental drivers highlight the benefits of a localized and context-dependent understanding of forest soil communities, and the ecosystem functions they regulate for achieving management goals with prescribed fire.

High intensity fire has been linked to oak regeneration after 10 years (Elliott et al., 2009)—a current management goal for this area. However, there is more recent evidence that prescribed fire in conjunction with soil microbial communities and heterogenous vegetation is key for oak regeneration objectives (Beals et al., 2022; Oakman et al., 2019; Waldrop et al., 2016). Management of oak-hickory dominated forests with prescribed fire is currently complicated by increasing pressure from mesophytic vegetative types (Nowacki and Abrams, 2008; Oakman et al., 2019; Waldrop et al., 2016). A. rubrum and L. tulipifera are currently abundant and widespread throughout Southern Appalachia. These species are associated with higher quality litter and increased nutrient cycling (Vose and Elliott, 2016), and regenerate rapidly in response to clearcutting (Elliott et al., 2020). Osburn et al. (2021a) determined that both fungal and bacterial community assembly are significantly impacted by vegetative regeneration after land-use disturbance. This study indicates that 7 years following a severe wildfire, soil microbial efficiency returns to levels observed in prescribed burn and fire excluded watersheds. Further studies could examine the interaction of vegetation, microbial communities, and nutrient cycling dynamics following wildfire succession in this region (Beals et al., 2022; Schill et al., 2024).

We determined that NH4+ is the strongest predictor of microbial biomass and TN is the strongest predictor of SOC. This calls for further study on the long-term storage potential of soil C in response to fire-induced nutrient availability in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. This is supported by Huffman and Madritch (2018) that found soil C may increase over time since fire in wildfire-impacted areas of Linville Gorge, NC, United States. Relative to the other watersheds, the partially harvested watershed had higher pH, lower C availability, and higher C acquisition enzyme activity. This also corresponded with a higher C metabolic quotient—indicating lower microbial metabolic efficiency. This highlights the importance of natural and anthropogenic N availability on C storage potential in Southern Appalachian forests and is important to consider if soil C sequestration is a management goal.

To meet forest management goals, it is essential to understand the multifaceted response of ecosystems to more than a century of fire exclusion (Robbins et al., 2024), in conjunction with current environmental changes and disturbances. This requires understanding the response of soil microbial communities and their impact on nutrient cycling dynamics. Our study used an integrated taxonomic and multifunctional approach to compare watersheds impacted by fire exclusion, repeated prescribed burns, wildfire, and partial harvesting. Relative to the other watersheds, partial harvesting altered soil microbial community structure and decreased carbon use efficiency. Further study is needed on the effects of partial harvesting to elucidate the mechanisms behind these effects. Prescribed fire generally increased organic N availability and microbial biomass N, elevated LAP activity, and increased C mineralization compared to the fire-excluded watershed, despite no significant change in mineral soil bacterial or fungal community structure. Microbial community structure across all watersheds was influenced by land-use history, while ecosystem function corresponded with resource availability. This study contributes to a growing knowledge base surrounding the impacts of fire, both naturally and as a management tool, in Southern Appalachia relative to other anthropogenic disturbance.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, BioProject ID: PRJNA1213841.

Author contributions

MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. TC: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AP: Writing – review & editing. DH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. PC: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. FA: Writing – review & editing. JB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work is funded through grants United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture #2022-67019-36960 and Coweeta LTER National Science Foundation #1637522. Prescribed burn treatments were conducted under United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute of Food and Agriculture #2017-67019-26544. This research was supported in part by the U. S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the United States Forest Service Southern Research Station, Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory, the Nantahala Ranger District Office, and the Nature Conservancy in North Carolina for their collaboration on this study. We also acknowledge Dr. Katherine Elliott, Dr. Chelcy Miniat, Dr. Jennifer Knoepp, and Dr. Paul Bolstad for their contributions to the study design of the Coweeta Hydrologic Laboratory watershed pairs. We thank the Duke University School of Medicine for the use of the Microbiome Core Facility, which provided 16S microbial DNA library preparation and University of Kansas Soil Analysis Service Center for their aid in running samples. A special thank you to Bobbie Niederlehner for her analytical expertise and contribution to this work. Finally, thank you to Morgan Wood and Jonas Guilliano for the time they spent collecting samples and working in the laboratory. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in the material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

DH and FA Associate editors, declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2026.1694825/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Adkins J. Docherty K. M. Gutknecht J. L. M. Miesel J. R. (2020). How do soil microbial communities respond to fire in the intermediate term? Investigating direct and indirect effects associated with fire occurrence and burn severity. Sci. Total Environ.745:140957. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140957,

2

Adkins J. Docherty K. M. Miesel J. R. (2022). Copiotrophic bacterial traits increase with burn severity one year after a wildfire. Front. For. Glob. Change5:873527. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2022.873527

3

Agbeshie A. A. Abugre S. Atta-Darkwa T. AwPHh R. (2022). A review of the effects of forest fire on soil properties. J. For. Res.33, 1419–1441. doi: 10.1007/s11676-022-01475-4

4

Allison S. D. Weintraub M. N. Gartner T. B. Waldrop M. P. (2011). “Evolutionary-economic principles as regulators of soil enzyme production and ecosystem function” in Soil enzymology. eds. ShuklaG.VarmaA. (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer), 229–243.

5

Averill C. Hawkes C. V. (2016). Ectomycorrhizal fungi slow soil carbon cycling. Ecol. Lett.19, 937–947. doi: 10.1111/ele.12631,

6

Beals K. K. Scearce A. E. Swystun A. T. Schweitzer J. A. (2022). Belowground mechanisms for oak regeneration: interactions among fire, soil microbes, and plant community alter oak seedling growth. For. Ecol. Manag.503:119774. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119774

7

Bellemain E. Carlsen T. Brochmann C. Coissac E. Taberlet P. Kauserud H. (2010). ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: an in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC Microbiol.10:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-189,

8

Boerner R. E. J. Coates A. T. Yaussy D. A. Waldrop T. A. (2008). Assessing ecosystem restoration alternatives in eastern deciduous forests: the view from belowground. Restor. Ecol.16, 425–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-100X.2007.00312.x

9

Brown S. P. Veach A. M. Horton J. L. Ford E. Jumpponen A. Baird R. (2019). Context dependent fungal and bacterial soil community shifts in response to recent wildfires in the southern Appalachian Mountains. For. Ecol. Manag.451:117520. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117520

10

Burt T. P. Ford Miniat C. Laseter S. H. Swank W. T. (2018). Changing patterns of daily precipitation totals at the Coweeta hydrologic laboratory, North Carolina, USA: Coweeta daily rainfall. Int. J. Climatol.38, 94–104. doi: 10.1002/joc.5163

11

Caiafa M. V. Nelson A. R. Borch T. Roth H. K. Fegel T. S. Rhoades C. C. et al . (2023). Distinct fungal and bacterial responses to fire severity and soil depth across a ten-year wildfire chronosequence in beetle-killed lodgepole pine forests. For. Ecol. Manag.544:121160. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2023.121160

12

Caldwell P. Elliott K. Vose J. Zietlow D. Knoepp J. (2020). Watershed‐scale vegetation, water quantity, and water quality responses to wildfire in the southern Appalachian mountain region, United States. Hydrol. Process.34, 5188–5209. doi: 10.1002/hyp.13922

13

Callahan B. J. McMurdie P. J. Rosen M. J. Han A. W. Johnson A. J. A. Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods13, 581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869,

14

Caporaso J. G. Lauber C. L. Walters W. A. Berg-Lyons D. Lozupone C. A. Turnbaugh P. J. et al . (2011). Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.108 Suppl 1, 4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107,

15

Carpenter D. O. Taylor M. K. Callaham M. A. Hiers J. K. Loudermilk E. L. O’Brien J. J. et al . (2021). Benefit or liability? The ectomycorrhizal association may undermine tree adaptations to fire after long-term fire exclusion. Ecosystems24, 1059–1074. doi: 10.1007/s10021-020-00568-7

16

Certini G. (2005). Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia143, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00442-004-1788-8,

17

Coates T. A. Ford W. M. (2022). Fuel and vegetation changes in southwestern, unburned portions of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, USA, 2003–2019. J. For. Res.33, 1459–1470. doi: 10.1007/s11676-022-01515-z

18

Coates T. A. Shelburne V. B. Waldrop T. A. Smith B. R. Hill H. S. Simon D. M. (2010). “Forest soil response to fuel reduction treatments in the southern Appalachian Mountains” in Proceedings of the 14th biennial southern silvicultural research conference. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-121. ed. StanturfJ. A. (Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station), 614.

19

Colenbaugh C. Hagan D. L. (2023). After the fire: potential impacts of fire exclusion policies on historical Cherokee culture in the southern Appalachian Mountains, USA. Hum. Ecol.51, 291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10745-023-00395-z

20

Coweeta Basin Monthly Average Temperature and Precipitation . (2023). USDA US Forest Service Southern Research Station. Database. (Accessed December 7, 2024).

21

Delgado-Baquerizo M. Reich P. B. Trivedi C. Eldridge D. J. Abades S. Alfaro F. D. et al . (2020). Multiple elements of soil biodiversity drive ecosystem functions across biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol.4, 210–220. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-1084-y

22

Deng S. P. Moore J. M. Tabatabai M. A. (2000). Characterization of active nitrogen pools in soils under different cropping systems. Biol. Fertil. Soils32, 302–309. doi: 10.1007/s003740000252

23

Dooley S. R. Treseder K. K. (2012). The effect of fire on microbial biomass: a meta-analysis of field studies. Biogeochemistry109, 49–61. doi: 10.1007/s10533-011-9633-8

24

Dove N. C. Hart S. C. (2017). Fire reduces fungal species richness and in situ mycorrhizal colonization: a meta-analysis. Fire Ecol.13, 37–65. doi: 10.4996/fireecology.130237746

25

Dove N. C. Taş N. Hart S. C. (2022). Ecological and genomic responses of soil microbiomes to high-severity wildfire: linking community assembly to functional potential. ISME J.16, 1853–1863. doi: 10.1038/s41396-022-01232-9,

26

Dukes C. J. Coates T. A. Hagan D. L. Aust W. M. Waldrop T. A. Simon D. M. (2020). Long-term effects of repeated prescribed fire and fire surrogate treatments on forest soil chemistry in the southern Appalachian Mountains (USA). Fire3:20. doi: 10.3390/fire3020020

27

Eagar A. C. Mushinski R. M. Horning A. L. Smemo K. A. Phillips R. P. Blackwood C. B. (2022). Arbuscular Mycorrhizal tree communities have greater soil fungal diversity and relative abundances of saprotrophs and pathogens than ectomycorrhizal tree communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.88, e0178221–e0178221. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01782-21,

28

Elliott K. J. Hendrick L. Major A. E. Vose J. M. Swank W. T. (1999). Vegetation dynamics after a prescribed fire in the southern Appalachians. For. Ecol. Manag.114, 199–213. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00351-X

29

Elliott K. J. Vose J. M. Hendrick R. L. (2009). Long-Term Effects of High Intensity Prescribed Fire on Vegetation Dynamics in the Wine Spring Creek Watershed, Western North Carolina, USA. Fire Ecology,5, 66–85. doi: 10.4996/fireecology.0502066

30

Elliott K. J. Miniat C. F. Medenblik A. S. (2020). The long-term case for partial-cutting over clear-cutting in the southern Appalachians USA. New For.51, 273–295. doi: 10.1007/s11056-019-09731-y

31

Elliott K.J. Vose J.M. Clinton B.D. Knoepp J.D. . 2004. Effects of understory burning in a Mesic mixed-oak Forest of the southern Appalachians. Pages 272–283 in EngstromR.T.GalleyK.E.M.de GrootW.J. (eds.). Proceedings of the 22nd tall timbers fire ecology conference: Fire in temperate, boreal, and montane ecosystems. Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, FL.

32

Feng J. Zeng X.-M. Zhang Q. Zhou X.-Q. Liu Y.-R. HPHng Q. (2021). Soil microbial trait-based strategies drive metabolic efficiency along an altitude gradient. ISME Commun.1:71. doi: 10.1038/s43705-021-00076-2,

33

Ford C. R. Elliott K. J. Clinton B. D. Kloeppel B. D. Vose J. M. (2012). Forest dynamics following eastern hemlock mortality in the southern Appalachians. Oikos121, 523–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19622.x

34

Garten C. T. (2004). Potential net soil N mineralization and decomposition of glycine-13C in forest soils along an elevation gradient. Soil Biol. Biochem.36, 1491–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.04.019

35

Garten C. T. Post W. M. Hanson P. J. Cooper L. W. (1999). Forest soil carbon inventories and dynamics along an elevation gradient in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Biogeochemistry45, 115–145. doi: 10.1007/BF01106778

36

Hahn G. E. Coates T. A. Aust W. M. Bolding M. C. Thomas-Van Gundy M. A. (2021). Long-term impacts of silvicultural treatments on wildland fuels and modeled fire behavior in the ridge and Valley Province, Virginia (USA). For. Ecol. Manag.496:119475. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119475

37

Hall E. K. Bernhardt E. S. Bier R. L. Bradford M. A. Boot C. M. Cotner J. B. et al . (2018). Understanding how microbiomes influence the systems they inhabit. Nat. Microbiol.3, 977–982. doi: 10.1038/s41564-018-0201-z,

38

Hartig F. . 2022. DHARMa: ResidPHl Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level / Mixed) Regression Models_. R package version 0.4.6.

39

Hartman W. H. Richardson C. J. (2013). Differential nutrient limitation of soil microbial biomass and metabolic quotients (qCO2): is there a biological stoichiometry of soil microbes?PLoS One8:e57127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057127,

40

Horikoshi M. Tang Y. 2016 ggfortify: Data VisPHlization Tools for Statistical Analysis Results. Available online at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggfortify (Accessed April 17, 2024).

41

Hubbard R. M. Vose J. M. Clinton B. D. Elliott K. J. Knoepp J. D. (2004). Stand restoration burning in oak–pine forests in the southern Appalachians: effects on aboveground biomass and carbon and nitrogen cycling. For. Ecol. Manag.190, 311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2003.10.021

42

Huffman M. S. Madritch M. D. (2018). Soil microbial response following wildfires in thermic oak-pine forests. Biol. Fertil. Soils54, 985–997. doi: 10.1007/s00374-018-1322-5

43

Hughes K. W. Franklin J. A. Schweitzer J. Kivlin S. N. Case A. Aldrovandi M. et al . (2025). Post-fire Quercus mycorrhizal associations are dominated by Russulaceae, Thelephoraceae, and Laccaria in the southern Appalachian Mountains. Mycol. Progress24, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11557-025-02037-8

44

Jones K. A. Niknami L. S. Buto S. G. Decker D. (2022). Federal standards and procedures for the national watershed boundary dataset (WBD). 5th Edn U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods 11-A3.

45

Keiser A. D. Knoepp J. D. Bradford M. A. (2013). Microbial communities may modify how litter quality affects potential decomposition rates as tree species migrate. Plant Soil372, 167–176. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1730-0

46

Keiser A. D. Knoepp J. D. Bradford M. A. (2016). Disturbance decouples biogeochemical cycles across forests of the southeastern US. Ecosystems19, 50–61. doi: 10.1007/s10021-015-9917-2

47

Keyser T. L. Loftis D. L. (2021). Long-term effects of alternative partial harvesting methods on the woody regeneration layer in high-elevation Quercus rubra forests of the southern Appalachian Mountains, USA. For. Ecol. Manag.482:118869. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118869

48

Kivlin S. N. Harpe V. R. Turner J. H. Moore J. A. Moorhead L. C. Beals K. K. et al . (2021). Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal response to fire and urbanization in the great smoky mountains national Park. Elementa Sci. Anthropocene9:00037. doi: 10.1525/elementa.2021.00037

49

Knelman J. E. Graham E. B. Trahan N. A. Schmidt S. K. Nemergut D. R. (2015). Fire severity shapes plant colonization effects on bacterial community structure, microbial biomass, and soil enzyme activity in secondary succession of a burned forest. Soil Biol. Biochem.90, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.08.004

50

Knoepp J. D. Elliott K. J. Clinton B. D. Vose J. M. (2009). Effects of prescribed fire in mixed oak forests of the southern Appalachians: forest floor, soil, and soil solution nitrogen responses. J. Torrey Bot. Soc.136, 380–391. doi: 10.3159/08-ra-052.1

51

Knoepp J. D. See C. R. Vose J. M. Miniat C. F. Clark J. S. (2018). Total C and N pools and fluxes vary with time, soil temperature, and moisture along an elevation, precipitation, and vegetation gradient in southern Appalachian forests. Ecosystems21, 1623–1638. doi: 10.1007/s10021-018-0244-2

52

Knoepp J. D. Vose J. M. Swank W. T. (2004). Long-term soil responses to site preparation burning in the southern Appalachians. For. Sci.50, 540–550. doi: 10.1093/forestscience/50.4.540

53

Kranz C. Whitman T. (2019). Short communication: surface charring from prescribed burning has minimal effects on soil bacterial community composition two weeks post-fire in jack pine barrens. Appl. Soil Ecol.144, 134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.07.004

54

Lafon C.W. Grissino-Mayer H.D. Horn S.P. Klein R.N. 2010 Fire regimes of the southern Appalachian mountains: temporal and spatial variability over multiple scales and implications for ecosystem management. Available online at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/jfspresearch/84 (Accessed April 18, 2023).

55

Lafon C. W. Naito A. T. Grissino-Mayer H. D. Horn S. P. Waldrop T. A. (2017). Fire history of the Appalachian region: a review and synthesis (no. SRS-GTR-219). Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station.

56

Laseter S. H. Ford C. R. Vose J. M. Swift L. W. (2012). Long-term temperature and precipitation trends at the Coweeta hydrologic laboratory, Otto, North Carolina, USA. Hydrol. Res.43, 890–901. doi: 10.2166/nh.2012.067

57

Lauber C. L. Hamady M. Knight R. Fierer N. (2009). Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.75, 5111–5120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00335-09,

58

Liu C. Cui Y. Li X. Yao M. (2021). Microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.97:fiaa255. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiaa255,

59

Lu Q. An Z. Zhang B. Lu X. Mao X. Li J. et al . (2024). Optimizing tradeoff strategies of soil microbial community between metabolic efficiency and resource acquisition along a natural regeneration chronosequence. Sci. Total Environ.946:174337. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174337,

60

Lüdecke D. Ben-Shachar M. S. Patil I. Waggoner P. Makowski D. (2021). Performance: an R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Softw.6:3139. doi: 10.21105/joss.03139

61

Maestre F. T. Quero J. L. Gotelli N. J. Escudero A. Ochoa V. Delgado-Baquerizo M. et al . (2012). Plant species richness and ecosystem multifunctionality in global drylands. Science335, 214–218. doi: 10.1126/science.1215442,

62

Malik A. A. Puissant J. Buckeridge K. M. Goodall T. Jehmlich N. Chowdhury S. et al . (2018). Land use driven change in soil pH affects microbial carbon cycling processes. Nat. Commun.9:3591. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05980-1

63

Mazerolle M.J. (2023). AICcmodavg: Model selection and multimodel inference based on (Q)AIC(c). R package version 2.3.3. Available online at:https://cran.r-project.org/package=AICcmodavg (Accessed March 6, 2025).

64

McEwan R. W. Dyer J. M. Pederson N. (2011). Multiple interacting ecosystem drivers: toward an encompassing hypothesis of oak forest dynamics across eastern North America. Ecography34, 244–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06390.x

65

McMurdie P. J. Holmes S. (2013). Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One8:e61217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061217,

66

Miniat C. F. Oishi A. C. Bolstad P. V. Jackson C. R. Liu N. Love J. P. et al . (2021). The Coweeta hydrologic laboratory and the Coweeta long-term ecological research project. Hydrol. Process.35:e14302. doi: 10.1002/hyp.14302

67

Mitchell R. J. Liu Y. O’Brien J. J. Elliott K. J. Starr G. Miniat C. F. et al . (2014). Future climate and fire interactions in the southeastern region of the United States. For. Ecol. Manag.327, 316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2013.12.003

68

Nelson A. R. Narrowe A. B. Rhoades C. C. Fegel T. S. Daly R. A. Roth H. K. et al . (2022). Wildfire-dependent changes in soil microbiome diversity and function. Nat. Microbiol.7, 1419–1430. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01203-y,

69

Nelson A. R. Rhoades C. C. Fegel T. S. Roth H. K. Caiafa M. V. Glassman S. I. et al . (2024). Wildfire impact on soil microbiome life history traits and roles in ecosystem carbon cycling. ISME Commun.4:ycae108. doi: 10.1093/ismeco/ycae108,

70

Nowacki G. J. Abrams M. D. (2008). The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. Bioscience58, 123–138. doi: 10.1641/B580207

71

Oakman E. C. Hagan D. L. Waldrop T. A. Barrett K. (2019). Understory vegetation responses to 15 years of repeated fuel reduction treatments in the southern Appalachian Mountains, USA. Forests10:350. doi: 10.3390/f10040350

72

Oksanen J. Simpson G. Blanchet F. Kindt R. Legendre P. Minchin P. et al . (2024) vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6-8. Available online at:https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (Accessed January 29, 2025).

73

Osburn E. D. Aylward F. O. Barrett J. E. (2021b). Historical land use has long-term effects on microbial community assembly processes in forest soils. ISME Commun.1, 48–44. doi: 10.1038/s43705-021-00051-x,

74

Osburn E. D. Badgley B. D. Strahm B. D. Aylward F. O. Barrett J. E. (2021a). Emergent properties of microbial communities drive accelerated biogeochemical cycling in disturbed temperate forests. Ecology102:e03553. doi: 10.1002/ecy.3553

75