- 1School of Physical Education, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Brain Function and Brain Disease Prevention and Treatment of Guizhou Province, Guiyang, China

Background: Taekwondo involves dynamic kicking and intermittent high-intensity efforts; the quantitative effects of training and supplementation on sport-specific outcomes remain unclear.

Objective: To systematically quantify the effects of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on taekwondo-specific performance indicators—TSAT, FSKT (10-s and multiple-bout), CMJ, VO2max, and heart-rate indices (HRmean, HRmax, HRpeak)—and to explore potential moderators.

Methods: A PRISMA-guided systematic review and random-effects meta-analysis (SMD, 95% CI) were conducted on randomized or quasi-experimental studies involving taekwondo athletes. Risk of bias was assessed using RoB 2.0. Primary outcomes included TSAT and FSKT performance; secondary outcomes included CMJ, VO2max, and HR indices.

Results: Exercise training significantly improved TSAT (SMD = −0.82; 95% CI: −1.43 to −0.21), FSKT-10s (SMD = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.15–1.49), FSKT-mult (SMD = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.55–1.35), and VO2max (SMD = 1.54; 95% CI: 0.58–2.49); CMJ (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI: −0.02–0.45) and HRmax (SMD = −0.02; 95% CI: −0.48–0.44) showed no significant changes. Nutritional supplementation—especially caffeine—improved TSAT (SMD = −1.41; 95% CI: −2.24 to −0.57), FSKT-10s (SMD = 1.82; 95% CI: 1.08–2.57), FSKT-mult (SMD = 1.67; 95% CI: 0.72–2.62), and VO2max (SMD = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.60–1.31), with no effect on HR_mean (SMD = 0.10; 95% CI: −0.28–0.47) or HRpeak (SMD = 0.28; 95% CI: −0.46–1.02).

Conclusion: Both exercise training and nutritional supplementation significantly improve agility, repeated-kick performance, and aerobic capacity in taekwondo athletes. Nevertheless, the findings should be generalized cautiously due to the observed heterogeneity. Future well-designed, adequately powered randomized controlled trials with standardized protocols are warranted.

Systematic review registration: Identifier: CRD420251007058.

1 Introduction

Taekwondo is a dynamic Olympic combat sport characterized by rapid, high-precision kicking techniques and complex tactical execution (1–3). In contrast to boxing, judo, or wrestling, taekwondo performance primarily depends on high-speed, high-accuracy kicks aimed at specific scoring zones to gain tactical superiority or achieve technical knockdowns (4, 5). Since its inclusion in the Olympic Games in 2000, taekwondo has expanded globally, with increasingly demanding competition formats that require athletes to sustain repeated explosive actions interspersed with brief recovery periods—an effort pattern that mirrors a high-intensity interval training (HIIT) profile (6).

These physiological demands necessitate superior aerobic and anaerobic capacities, neuromuscular power, agility, and flexibility to efficiently utilize the glycolytic energy system (2, 3). The sport’s kinematic profile—comprising rapid kicking sequences, intricate footwork, ballistic jumping attacks, and dynamic defensive maneuvers—requires specialized physiological adaptations (4, 5). To evaluate these multidimensional demands, several validated sport-specific and general performance tests are commonly used. The Taekwondo-Specific Agility Test (TSAT) and the Frequency-Speed Kick Test (FSKT) assess agility, technical accuracy, and fatigue resistance (6, 7), while the countermovement jump (CMJ) quantifies lower-limb explosive power, which is crucial for ballistic kicking performance (8, 9). Aerobic capacity indicators, including maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) and heart-rate indices (HR_mean, HR_max, HR_peak), further reflect cardiovascular efficiency and recovery ability (10–12).

This integrative assessment framework has been extensively validated and widely applied in taekwondo sport-science research to capture the foundational determinants of performance (13, 14). Nonetheless, taekwondo performance remains multifactorial, encompassing physiological, technical, tactical, and psychological dimensions (15). Over the past decade, research has increasingly investigated exercise-based and nutritional interventions targeting these performance components. Exercise training—including plyometric, resistance, and HIIT protocols—has been shown to enhance neuromuscular strength, agility, and endurance (16–20). Meanwhile, nutritional supplementation—such as caffeine, creatine, β-alanine, and vitamin D—has demonstrated potential to optimize energy metabolism, delay fatigue, and improve recovery (21–23). However, considerable interindividual variability in response to these interventions persists, influenced by sex, dosage, genetic factors, and training experience (24–28). Approximately 20–30% of athletes are reported to be “non-responders,” underscoring the complexity of tailoring interventions to specific physiological profiles (26, 29, 30).

Previous reviews have often aggregated findings across heterogeneous combat sports or focused on single interventions, limiting sport-specific interpretability for taekwondo. Methodological inconsistencies—including small sample sizes, short intervention durations, and heterogeneous assessment protocols—further constrain the generalization of findings (28, 31–33). Consequently, there remains a lack of comprehensive synthesis evaluating both exercise and nutritional strategies within a unified analytical framework.

To address this gap, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize evidence on the effects of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on taekwondo-specific and general performance outcomes. The primary outcomes were TSAT, FSKT-10s, and FSKT-mult, which directly reflect sport-specific agility and repeated-kick performance. The secondary outcomes included CMJ, VO2max, and heart-rate indices (HR_mean, HR_max, HR_peak), representing broader physiological capacities. Furthermore, methodological and participant-related moderators were explored to identify potential sources of heterogeneity and to inform evidence-based performance enhancement in taekwondo athletes.

2 Methods

2.1 Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. The study protocol was prospectively registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) prior to data collection and literature retrieval (registration number: CRD420251007058).

2.2 Study design

This study adopted a systematic review and meta-analysis design aimed at comprehensively evaluating the effects of exercise and nutritional supplementation on physical performance in taekwondo athletes.

2.3 Data sources and search strategy

The literature search covered studies published from the inception of each database up to February 27, 2025. A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WoS). Keywords related to the study objectives were applied to titles, abstracts, and full texts to maximize the retrieval of potentially eligible studies (detailed search strategies are provided in Appendix 1).

To enhance both accuracy and efficiency, the search syntax was customized for each database: [Title/Abstract] in PubMed, TITLE-ABS-KEY in Scopus, and TS (Topic) in WoS. Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) were employed to refine keyword combinations. Studies involving patient or clinical populations were excluded to ensure that only those focusing on taekwondo athletes were retained.

The search was confined to peer-reviewed English-language journal articles. Grey literature—including theses, dissertations, conference proceedings, and non–peer-reviewed reports—was not considered in order to maintain methodological consistency and ensure data transparency across studies.

2.4 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

2.4.1 Inclusion criteria

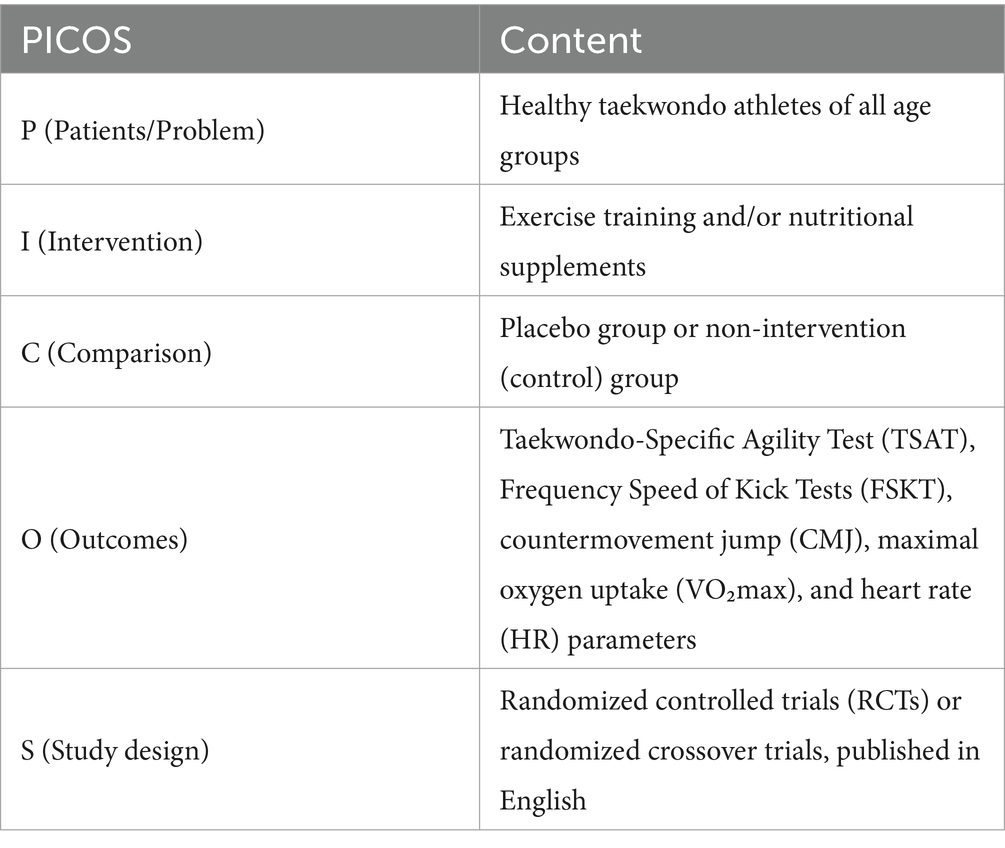

To ensure methodological rigor and practical relevance, studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria (see Table 1).

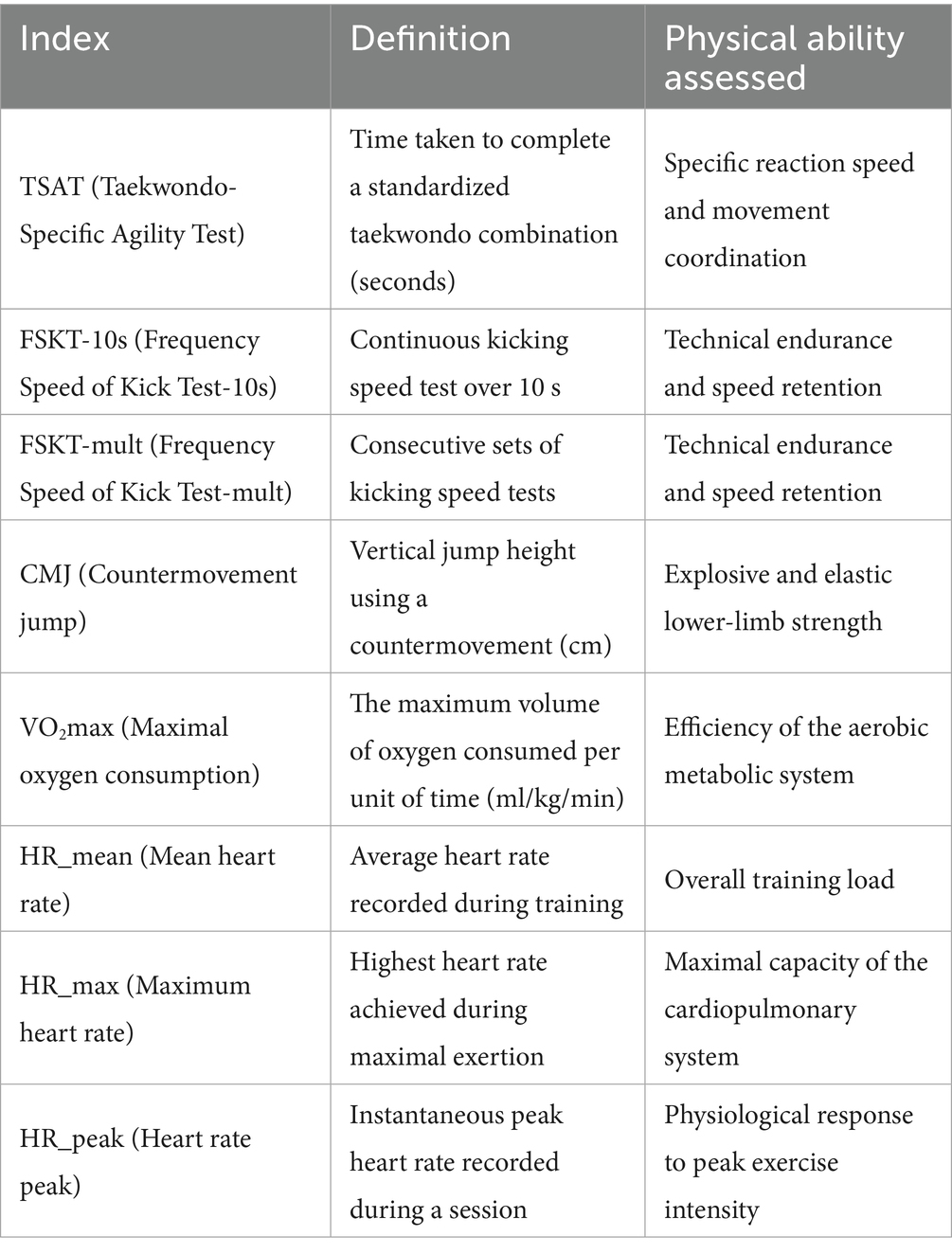

To ensure clarity in the interpretation of study outcomes, operational definitions and their corresponding performance capacities are detailed in Table 2. Primary outcomes were prespecified as taekwondo-specific performance measures (TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult) whereas secondary outcomes were defined as general physical fitness indicators (CMJ, VO₂max) and cardiovascular responses (HR_mean, HR_max, HR_peak). This hierarchy reflects sport-specific relevance and anticipated responsiveness to interventions.

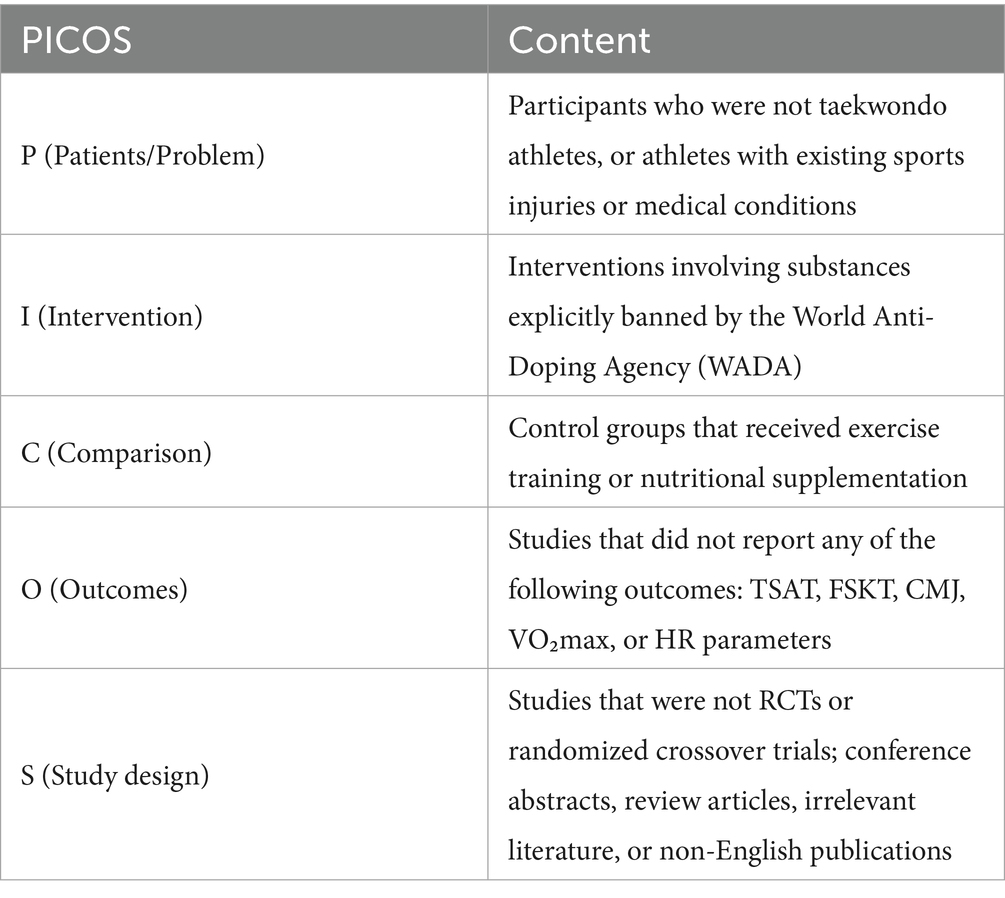

2.4.2 Exclusion criteria

Studies meeting any of the following conditions were excluded (see Table 3).

2.5 Data extraction and processing procedures

To ensure the methodological rigor of this study, a double-blind literature screening procedure was adopted and carried out independently by two reviewers. In the initial screening phase, the two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify studies that either met the inclusion criteria or required further evaluation. Studies that were potentially eligible or presented uncertainties were forwarded to the full-text review stage. Subsequently, the selected full texts were independently assessed by two reviewers (CX and WZ) to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review and meta-analysis. In the event of disagreement between the two reviewers (CX and WZ) during the screening process, consensus was sought through discussion; if consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (LL) was consulted to make the final decision.

The data extraction process was also conducted independently by two reviewers (CX and WZ) using a pre-designed Excel extraction sheet to ensure standardized documentation. Extracted data included: first author, year of publication, study design, participant characteristics (e.g., age, body weight, training experience, and sex), sample size, intervention type (exercise modality and nutritional supplement), duration and frequency of intervention, and reported performance outcomes.

Outcome data were extracted from each study, including TSAT (seconds), FSKT (repetitions), CMJ (centimeters), VO2max (mL/kg/min), and HR (beats per minute, bpm), along with corresponding means and standard deviations (SD), standard errors (SE), or 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). If a study reported only SE without SD, SD was calculated using the formula SD = SE × (for paired/crossover designs, within-subject correlations were accounted for where available).

For studies with incomplete outcome reporting or graphical-only data, the original authors were contacted via email to request raw data. All extracted data were cross-verified by both reviewers to ensure accuracy and reliability.

2.6 Quality assessment and risk of bias evaluation

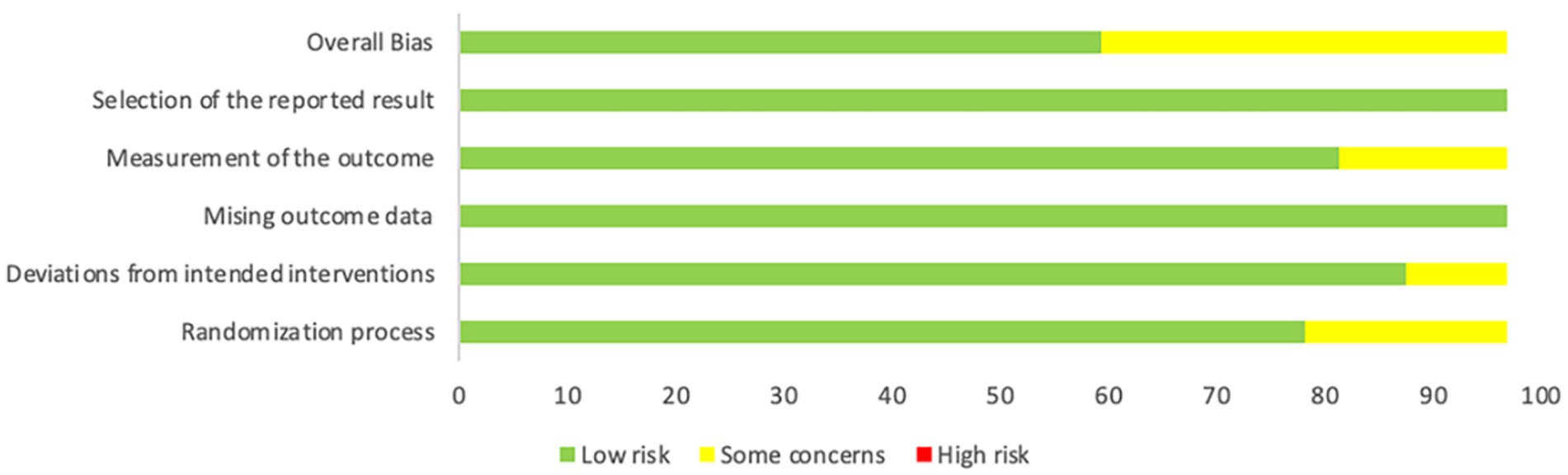

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (RoB 2.0), as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration, was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. The assessment was independently performed by two reviewers (CX and WZ). RoB 2.0 domains include: randomization process; deviations from intended interventions; missing outcome data; measurement of the outcome; selection of the reported result. Each domain was categorized as having a “low risk,” “high risk,” or “some concerns” regarding bias. For each outcome, an overall risk of bias judgment was made following the RoB 2.0 algorithm: “low risk” if all domains were judged as low risk, “high risk” if at least one domain was judged as high risk, and “some concerns” if at least one domain raised some concerns but no domain was at high risk. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer (LL) consulted when necessary.

2.7 Data analysis methods

The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager (RevMan) and Stata 16.0 statistical software. The meta-analysis prioritized primary outcomes (TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult); secondary outcomes (CMJ, VO2max, HR indices) were synthesized to contextualize sport-specific effects. Given the variation in measurement tools and units across the included studies, standardized mean difference (SMD) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were adopted as the effect size metrics to facilitate comparability. SMD was calculated by dividing the difference in means between the intervention and control groups by the pooled standard deviation. A significance threshold of p < 0.05 was applied. The magnitude of the SMD was interpreted according to Cohen’s classification—pre-specified in the analysis plan—as trivial (SMD < 0.2), small (0.2 ≤ SMD < 0.5), moderate (0.5 ≤ SMD < 0.8), and large (SMD ≥ 0.8).

For multi-arm studies, we addressed potential dependencies between effect sizes through the following approaches: (1) extracting independent comparisons where each intervention group was separately compared with the control group; (2) using shared control group methods with sample size adjustments when appropriate to avoid double-counting of participants; (3) conducting sensitivity analyses excluding multi-arm studies to verify the robustness of results. Random-effects models were prespecified for primary analyses; fixed-effects models were used only in sensitivity analyses when heterogeneity was low (p ≥ 0.05 and I2 < 50%).

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and τ2. When p ≥ 0.05 and I2 < 50%, results were considered to show low heterogeneity; otherwise, substantial heterogeneity (p < 0.05 or I2 ≥ 50%) prompted subgroup/sensitivity analyses. Subgroup variables included intervention duration (≤1 week vs. >1 week), intervention type, sex, study design (RCT vs. crossover), weight category (≤65 kg vs. >65 kg), and training experience (≤5 years vs. >5 years). Subgroup analyses were pre-specified and interpreted cautiously. For subgroups with fewer than five studies (or fewer than 150 total participants), estimates were reported descriptively without emphasizing p-values, and such findings were regarded as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Random-effects meta-regression (REML) was planned only for outcomes with at least 10 effect sizes, using prespecified moderators including intervention type, duration, sex, study design, weight class, and training experience. Because most outcomes involved fewer than 10 contributing studies and CMJ exhibited negligible heterogeneity (I2 ≈ 0%), meta-regression was not performed or was limited to exploratory analyses that were not intended for confirmatory inference.

To characterize between-study variability, a priori subgroup analyses, τ2 estimates, and 95% prediction intervals (PI) were applied. When multiple effects were reported within a single study, potential dependency was minimized through shared-control adjustments and sensitivity analyses. Consideration was also given to the use of robust variance estimation, but this approach was not implemented due to the limited number of available studies.

In addition, when at least 10 studies were included for a given outcome, publication bias was preliminarily assessed by visual inspection of funnel plots generated using Stata 16.0, and by Egger’s test where appropriate; for outcomes with fewer than 10 studies, small-study effects were interpreted qualitatively due to limited power. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted by sequentially removing individual studies to observe changes in the pooled effect size, thereby verifying the robustness and stability of the results and strengthening the evidence supporting the conclusions.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search results

A total of 993 relevant records were identified through a systematic search of three major electronic databases: Web of Science (WoS), PubMed, and Scopus. Specifically, 538 records were retrieved from WoS, 154 from PubMed, and 301 from Scopus. Prior to the initial screening, 376 duplicate records were removed, resulting in 617 unique records eligible for title and abstract screening.

During this initial screening stage, 535 records were excluded based on titles and abstracts due to irrelevance to the research topic, leaving 82 articles for full-text assessment.

After full-text review, 51 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 19 did not report relevant outcome measures; 4 had unavailable full texts; 22 did not meet the required study design criteria; 3 provided incomplete post-intervention data; and 3 were non-English publications.

Following a rigorous and systematic screening process, a total of 31 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the subsequent analyses. A detailed flow diagram of the literature selection process is presented in Figure 1.

3.2 Study characteristics and methodological quality assessment

3.2.1 Study design

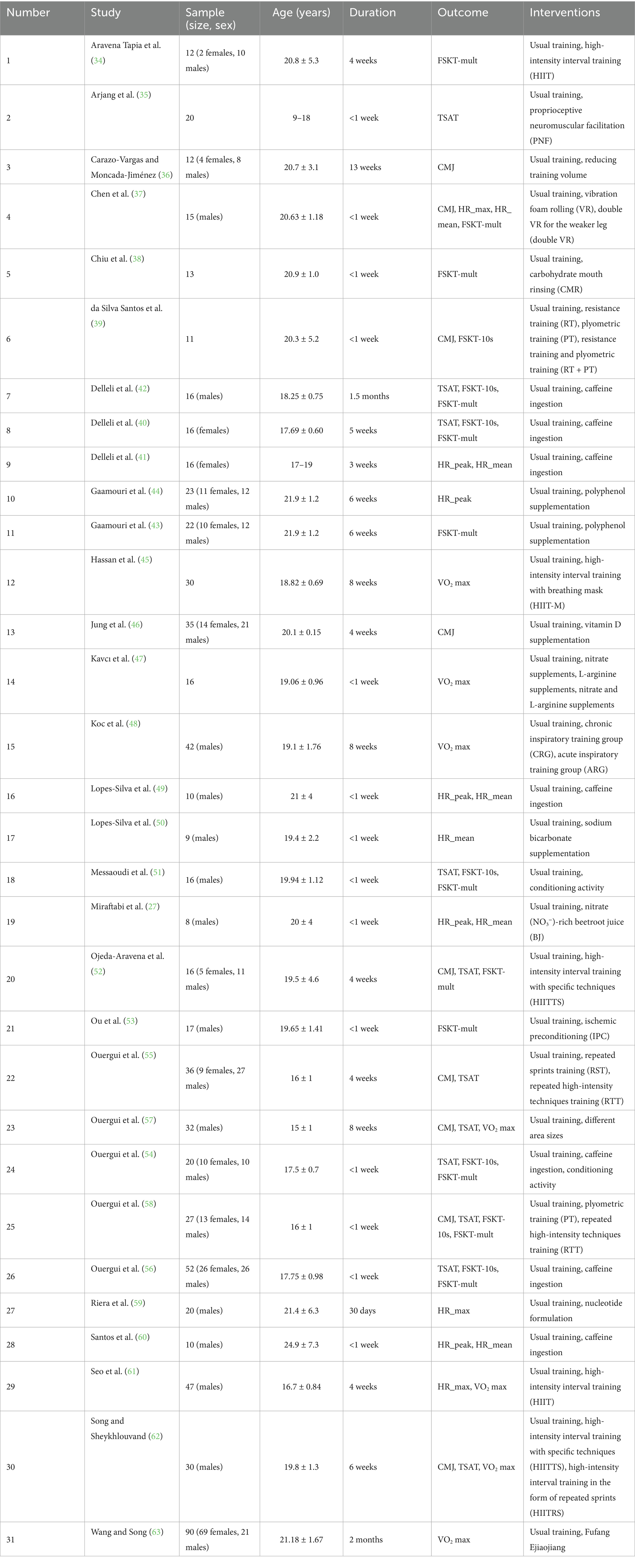

Among the 31 studies included in this meta-analysis, 16 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 15 were randomized crossover trials. Of these, 3 studies employed a four-arm design, 5 employed a three-arm design, and the remaining 23 were two-arm designs (27, 34–63). Detailed study designs and control conditions are presented in Table 4.

3.2.2 Participant characteristics

A total of 739 taekwondo athletes were included, with ages ranging from 15 to 24.9 years. Regarding sex distribution, 13 studies enrolled only male athletes (n = 272), 2 enrolled only female athletes (n = 32), and 11 included both male (n = 172) and female athletes (n = 173). The remaining 5 studies did not specify the sex of participants (n = 90).

3.2.3 Intervention measures

Of the 31 included studies, 15 investigated exercise-only interventions, incorporating 18 different types of exercise strategies (see Appendix 2 for details). Another 15 studies involved nutrition-only interventions, utilizing 11 different types of supplements (see Appendix 3 for details). One study implemented both exercise and nutritional supplementation simultaneously.

3.2.4 Outcome measures

All included studies reported at least one of the following primary outcome measures: TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult, CMJ, VO2max, and HR parameters (HR_mean, HR_max, and HR_peak).

Among studies on exercise training, 9 reported TSAT, 7 reported FSKT-10s, 9 reported FSKT-mult, 14 reported CMJ, 7 reported VO2max, 2 reported HR_mean, 3 reported HR_max, and none reported HR_peak.

Among studies on nutritional supplementation, 4 reported TSAT, 4 reported FSKT-10s, 6 reported FSKT-mult, 1 reported CMJ, 4 reported VO2max, 5 reported HR_mean, 1 reported HR_max, and 5 reported HR_peak.

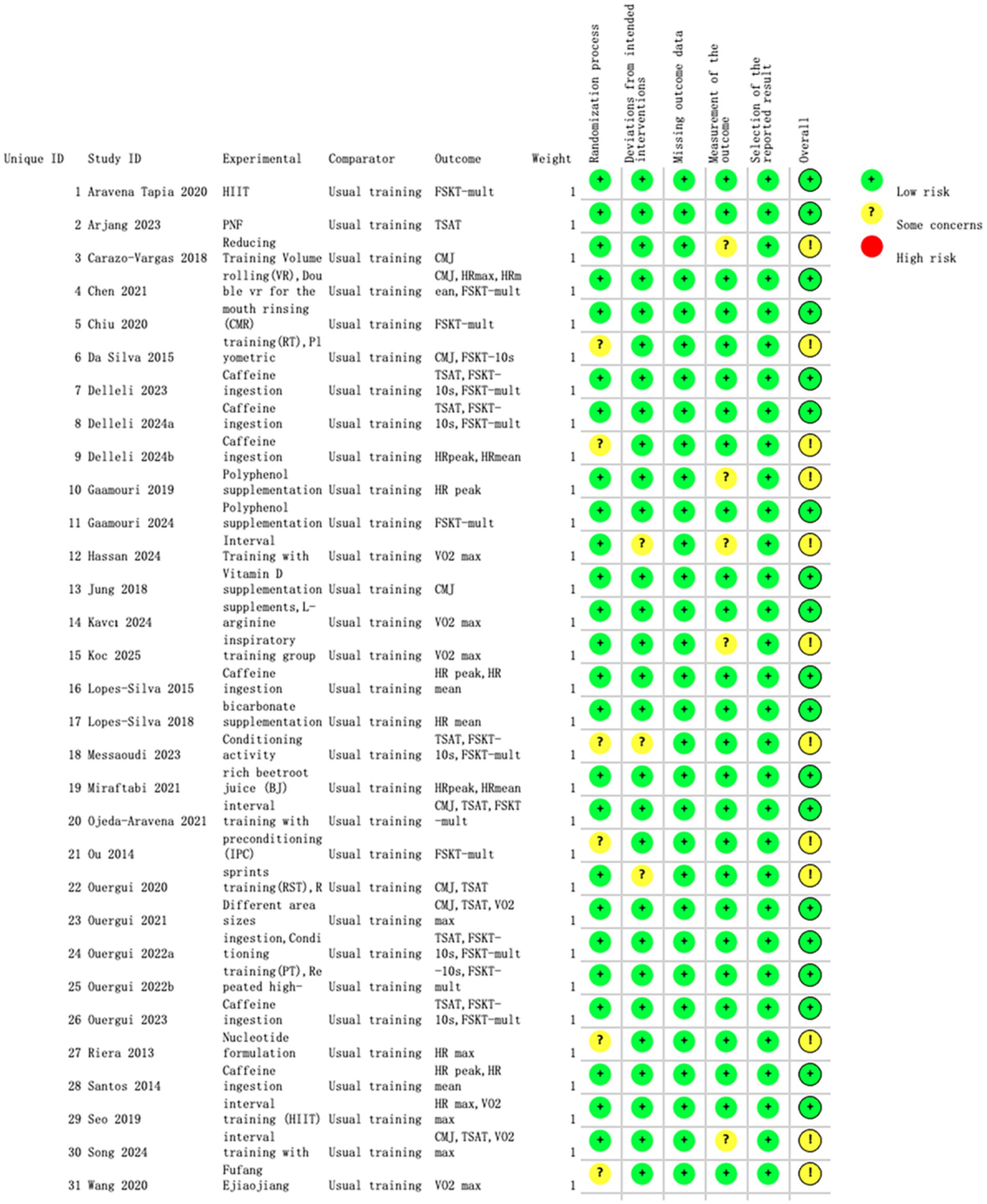

3.3 Risk of bias assessment

According to the RoB 2.0 risk of bias assessment, the overall methodological quality of the 31 randomized controlled trials included in this study was relatively high. Among the six core evaluation domains, the randomization process performed best, with approximately 90% of studies judged as low risk and only 10% rated as having some concerns. Missing outcome data and selective reporting were also well controlled, with more than 85% of studies classified as low risk. By contrast, the measurement of outcome domain was relatively weaker, with about 75% rated as low risk and 25% as having some concerns. For deviations from intended interventions, 80% of studies were rated low risk, 15% had some concerns, and 5% were rated high risk. Overall, 80% of the included studies were judged as having low risk of bias, 20% as having some concerns, and none as high risk.

At the study level, the vast majority of trials demonstrated low risk (green) across key methodological domains, indicating generally acceptable design and implementation quality. The primary methodological concerns were concentrated in the domains of outcome measurement and deviations from intended interventions, where several studies were rated as “unclear risk” (yellow) due to insufficient objectivity in measurement methods or incomplete blinding implementation. Notably, no study was rated as high risk (red) in any domain, which strengthens the credibility of the meta-analysis findings and reflects the strict inclusion criteria applied, effectively minimizing the entry of low-quality studies.

The results of the RoB 2.0 assessment are illustrated in Figures 2, 3.

Figure 3. Summary of risk of bias for each included study (green plus sign = low risk; yellow question mark = unclear risk; red minus sign = high risk).

3.4 Meta-analysis results

3.4.1 Effects of exercise trainings

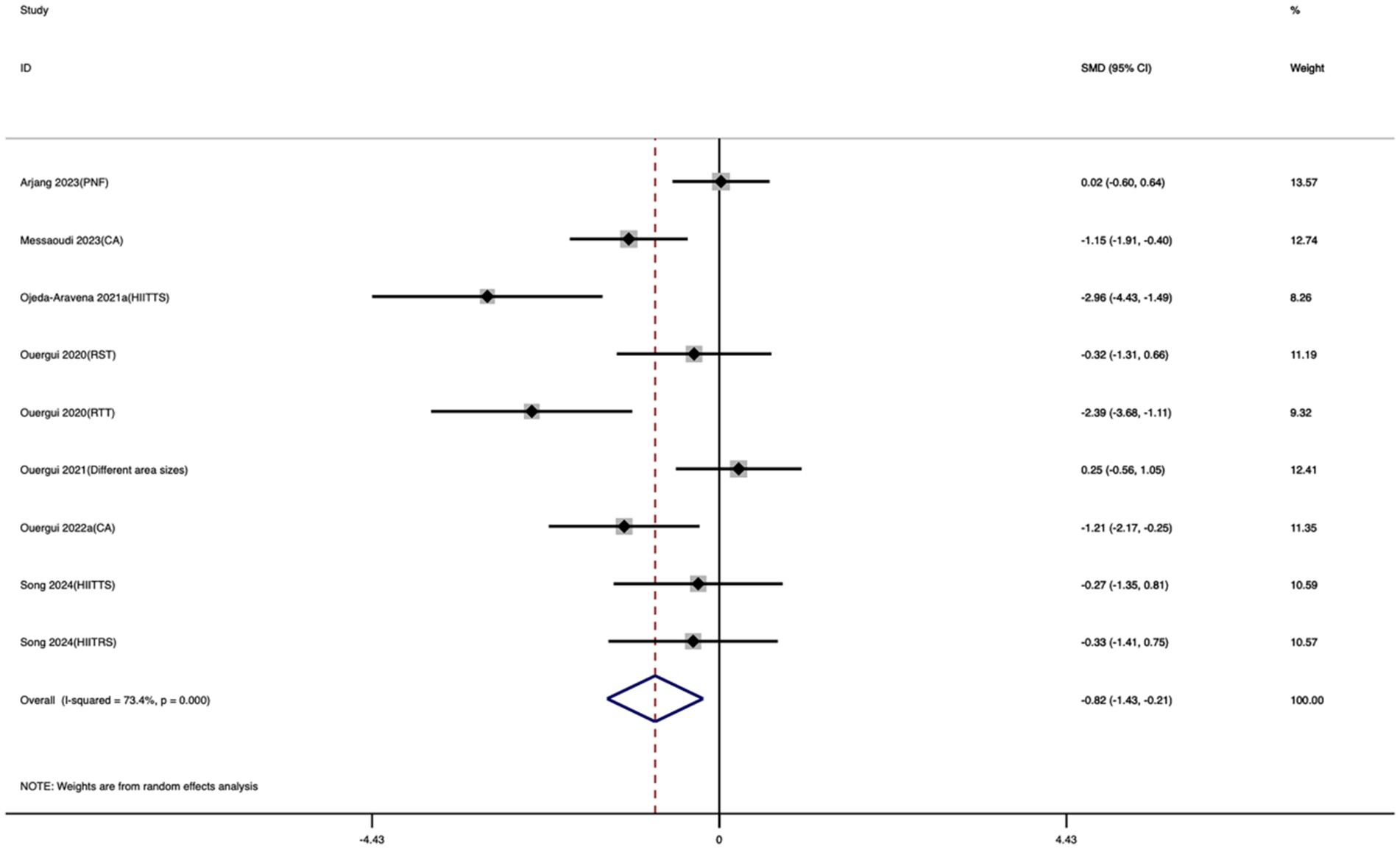

3.4.1.1 Improvement in Taekwondo-Specific Agility Test

A total of 9 studies were included in this meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of exercise training on TSAT. As shown in Figure 4, the meta-analysis results indicated that compared with the control group, exercise training significantly reduced the time required to complete TSAT. The standardized mean difference demonstrated a large and statistically significant effect (SMD = −0.82; 95% CI: −1.43 to −0.21; I2 = 73.4%; p = 0.009).

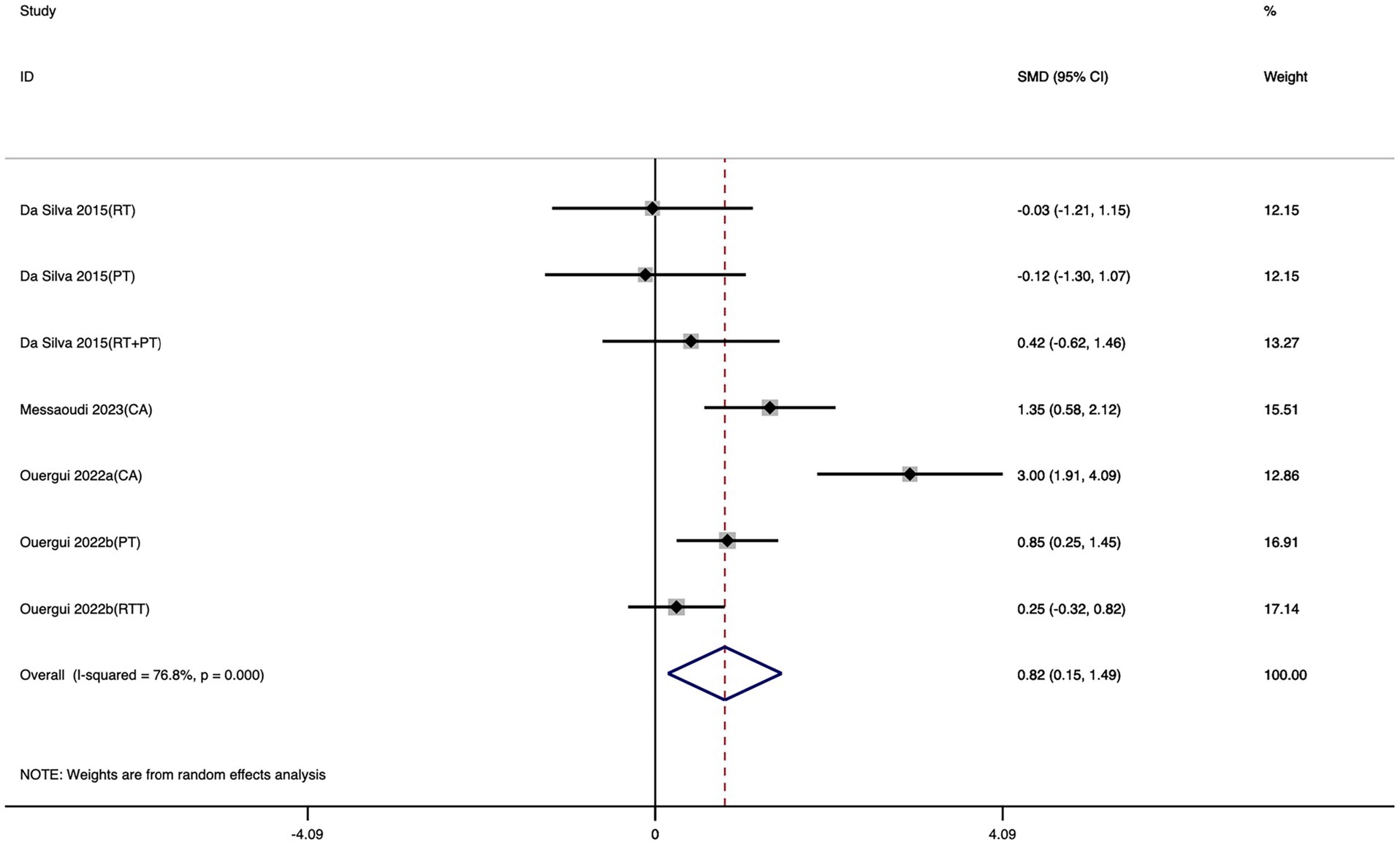

3.4.1.2 Improvement in 10-s Frequency Speed of Kick Test

Seven studies were included in the meta-analysis evaluating the effect of exercise training on FSKT-10s. As shown in Figure 5, taekwondo athletes who received exercise training performed significantly better in FSKT-10s compared with the control group, as reflected by a notable increase in the number of kicks. The effect size was moderate (SMD = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.15 to 1.49; I2 = 76.8%; p = 0.016).

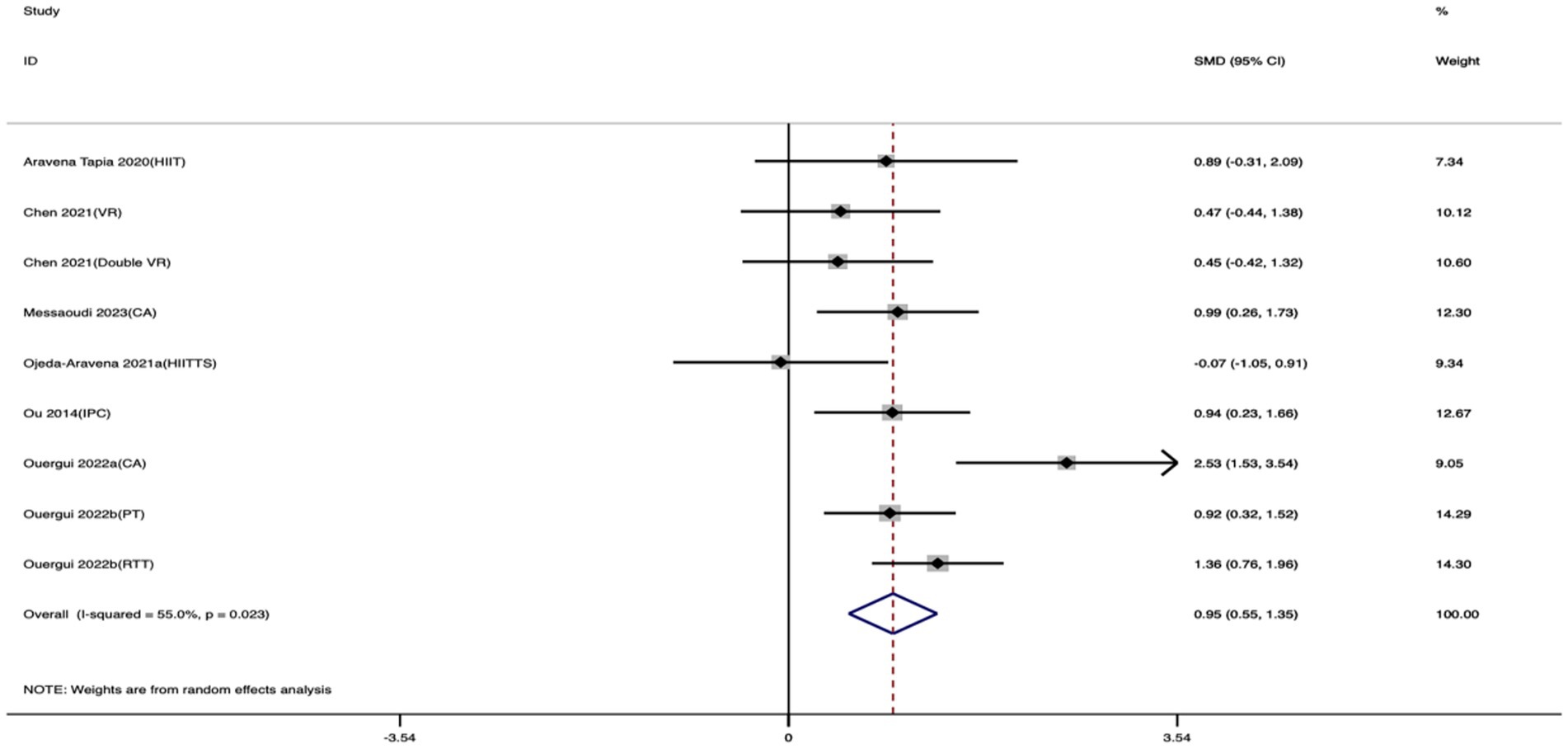

3.4.1.3 Improvement in multiple-bout Frequency Speed of Kick Test

Nine studies were included to evaluate the effect of exercise training on FSKT-mult. As shown in Figure 6, taekwondo athletes who received exercise training performed significantly better than controls, as evidenced by a clear increase in the number of kicks. The standardized mean difference revealed a large and statistically significant effect (SMD = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.55 to 1.35; I2 = 55%; p < 0.001).

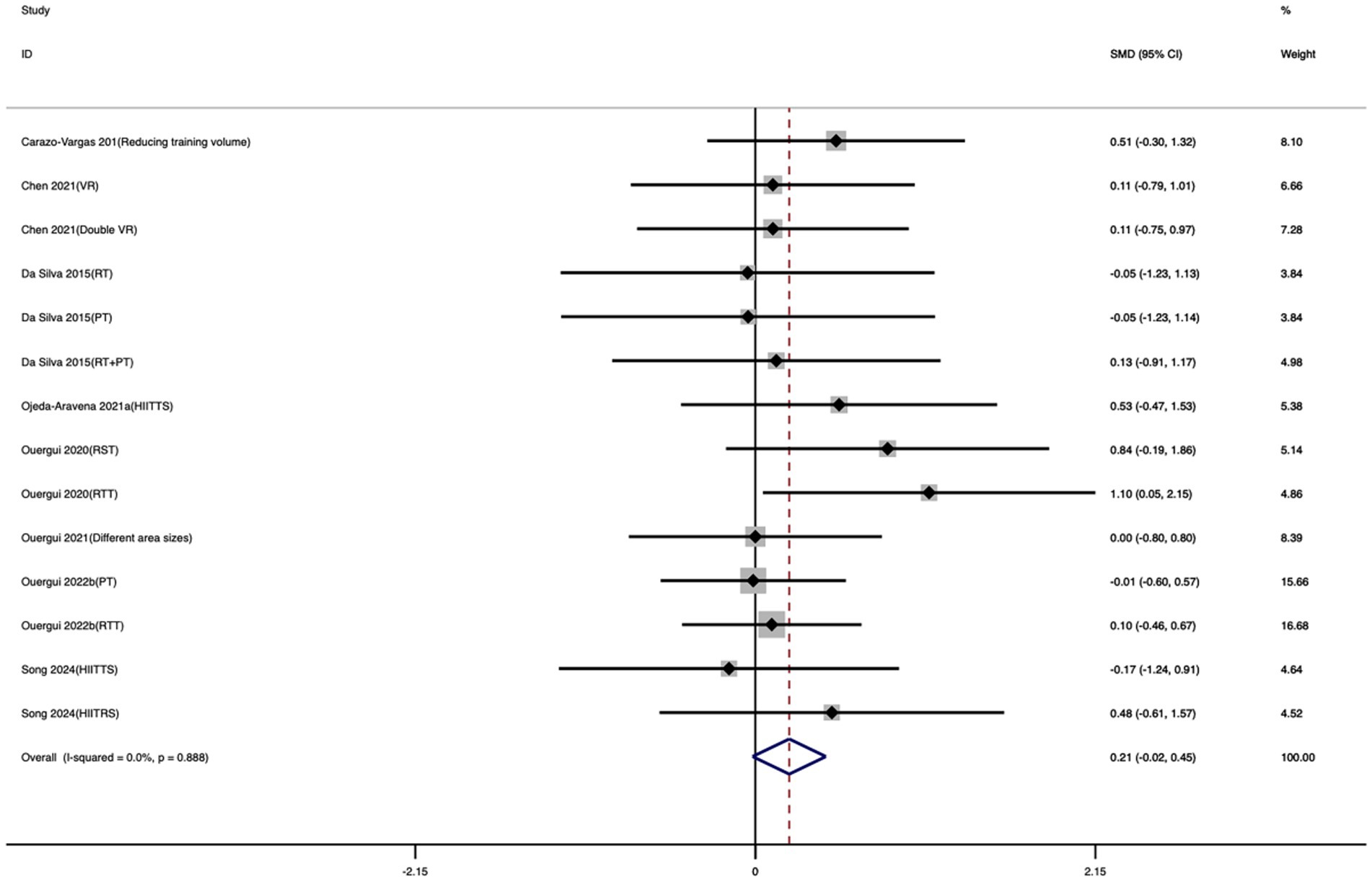

3.4.1.4 Improvement in countermovement jump

Fourteen studies were included in the CMJ meta-analysis. As shown in Figure 7, compared with the control group, exercise training did not produce a statistically significant improvement in CMJ. Only a slight, non-significant trend toward enhancement was observed (SMD = 0.21; 95% CI: −0.02 to 0.45; I2 = 0%; p = 0.07). The heterogeneity across studies was minimal, indicating a high level of result consistency.

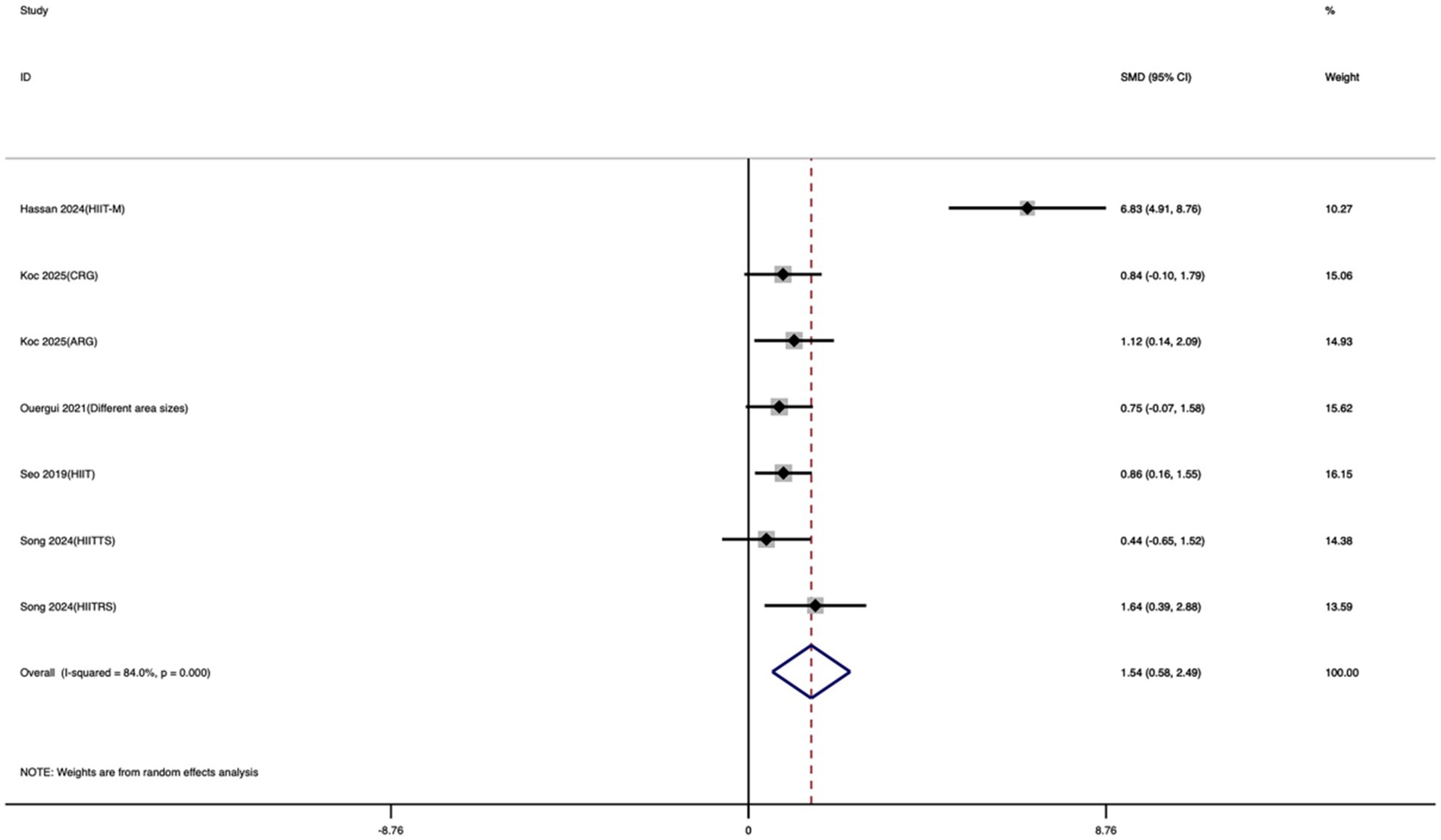

3.4.1.5 Improvement in maximal oxygen uptake

Seven studies were included to evaluate the effect of exercise training on VO2max. As shown in Figure 8, athletes who underwent exercise training demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in VO2max compared with controls, with a large and statistically significant effect size (SMD = 1.54; 95% CI: 0.58 to 2.49; I2 = 84%; p = 0.002). Although there was substantial heterogeneity among studies—reducing the consistency of results—the overall findings clearly demonstrated that exercise training significantly enhanced aerobic metabolic capacity in taekwondo athletes.

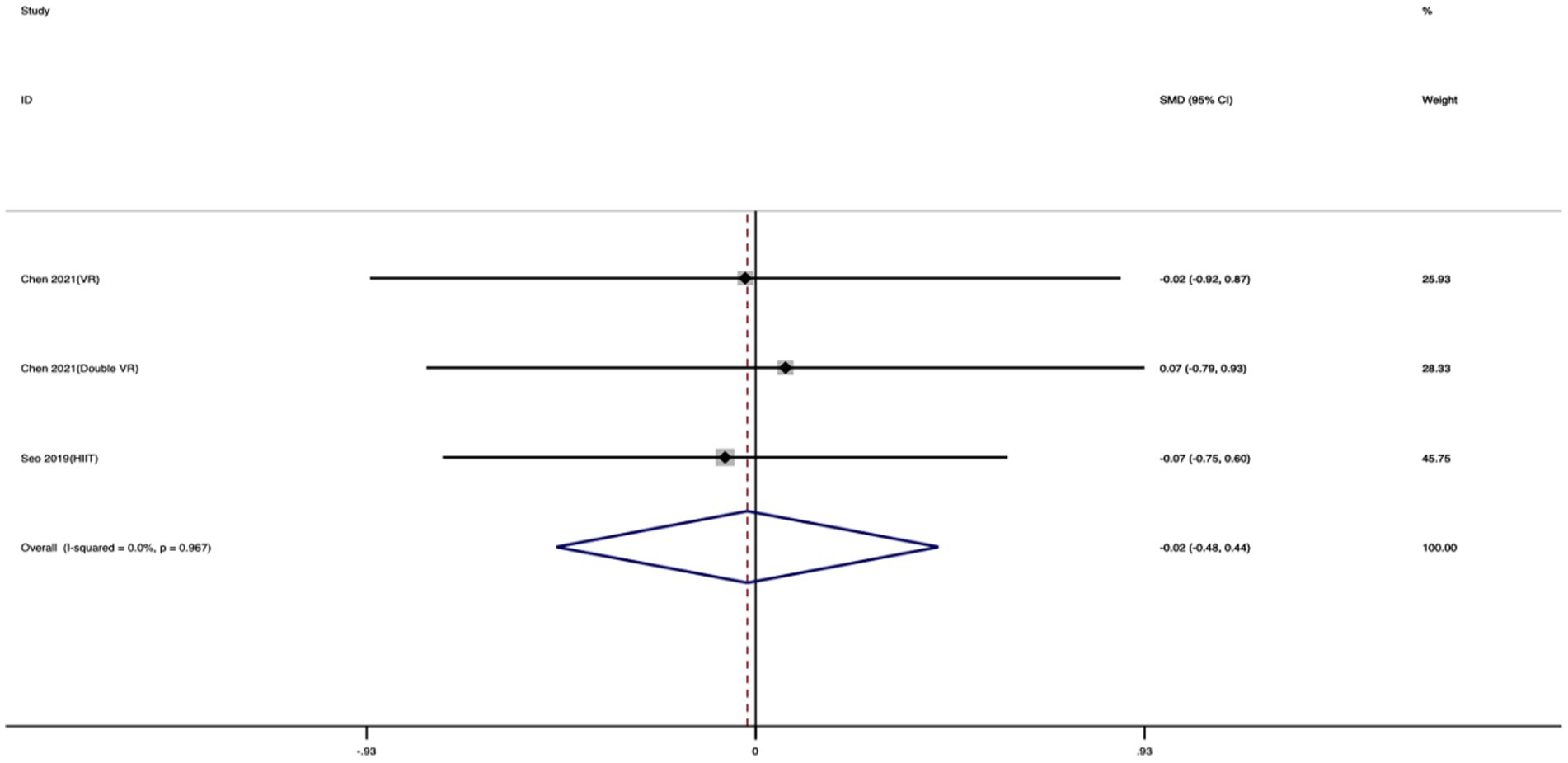

3.4.1.6 Improvement in maximum heart rate

Five studies were included in the HR_max meta-analysis. As shown in Figure 9, no significant between-group difference was observed in HR_max between the exercise and control groups. The standardized mean difference indicated a negligible and statistically non-significant effect (SMD = −0.02; 95% CI: −0.48 to 0.44; I2 = 0%; p = 0.993), with no substantial heterogeneity across studies.

3.4.2 Effects of nutritional supplementations

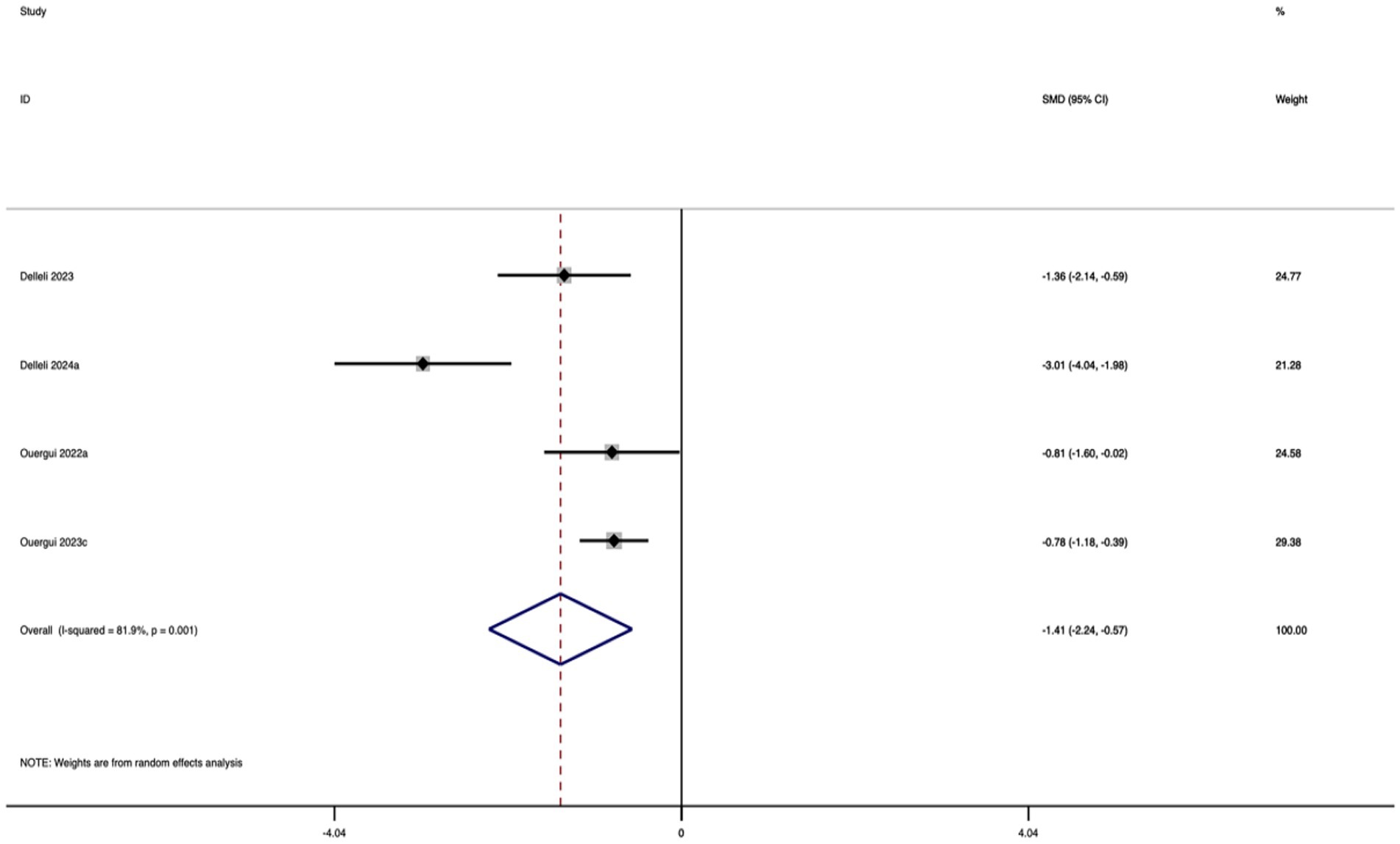

3.4.2.1 Improvement in Taekwondo-Specific Agility Test

A total of four studies were included in this meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of caffeine supplementation on TSAT. As shown in Figure 10, the results indicated that, compared with the control group, the caffeine group exhibited a significantly shorter TSAT completion time, reflecting a notable improvement in agility performance. The effect size was large and statistically significant (SMD = −1.41; 95% CI: −2.24 to −0.57; I2 = 81.9%; p = 0.001). Substantial heterogeneity was observed, suggesting that results should be interpreted with caution.

3.4.2.2 Improvement in 10-s Frequency Speed of Kick Test

Four studies were included in the meta-analysis evaluating the effect of caffeine supplementation on FSKT-10s. As shown in Figure 11, caffeine intake significantly increased the number of kicks performed during FSKT-10s compared with the control group. The effect size was large and statistically significant (SMD = 1.82; 95% CI: 1.08 to 2.57; I2 = 74.2%; p < 0.001), although moderate heterogeneity was present.

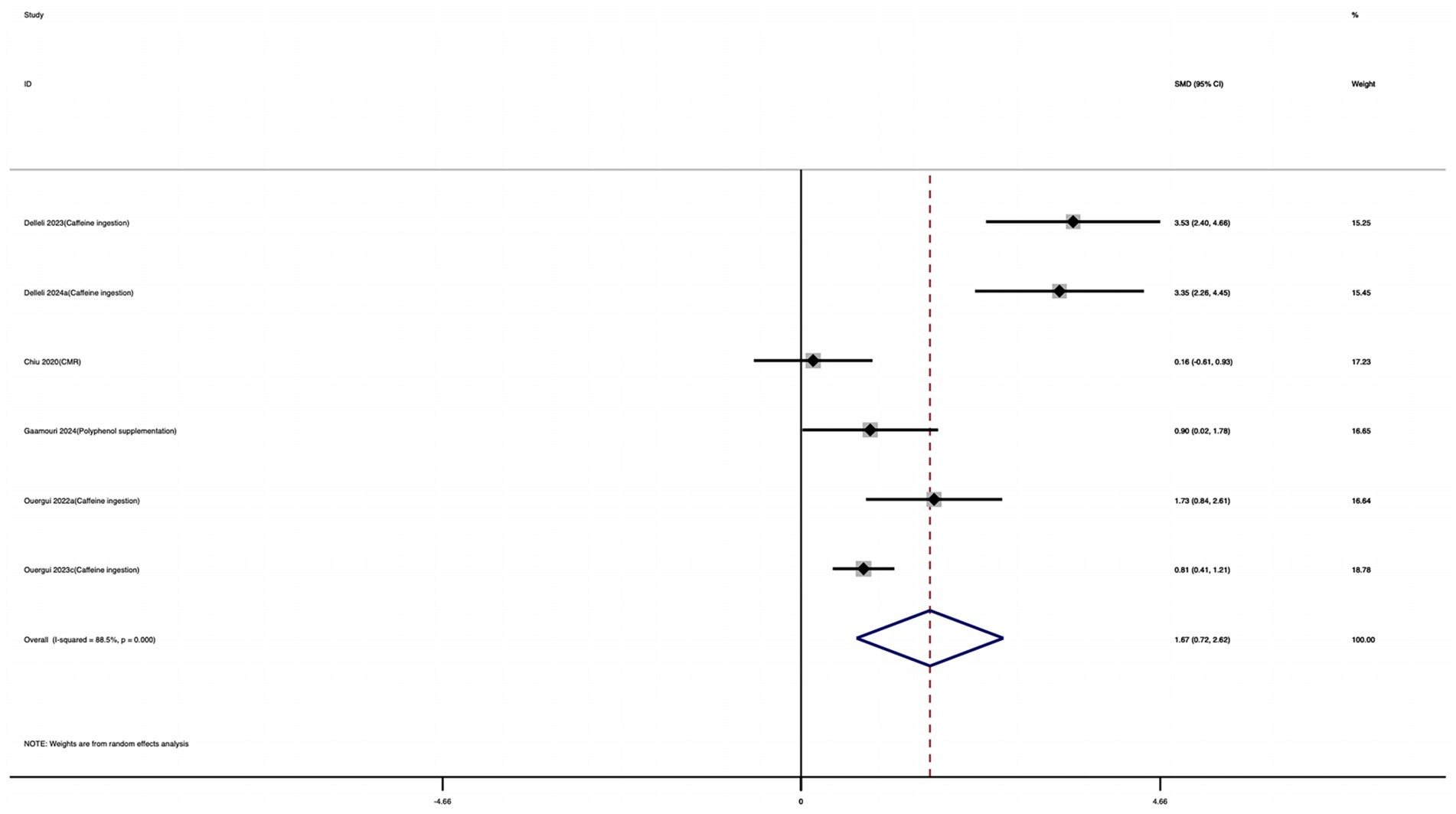

3.4.2.3 Improvement in multiple-bout Frequency Speed of Kick Test

Six studies were included in this meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of nutritional supplementation on FSKT-mult. As shown in Figure 12, athletes who received nutritional supplementation performed significantly better than those in the control group, as indicated by a substantial increase in the number of kicks. The effect size was large and statistically significant (SMD = 1.67; 95% CI: 0.72 to 2.62; I2 = 88.5%; p = 0.001). High heterogeneity was observed, indicating variability among study designs and supplementation protocols.

3.4.2.4 Improvement in maximal oxygen uptake

Four studies were included to assess the effect of nutritional supplementation on VO2max. As shown in Figure 13, taekwondo athletes receiving nutritional supplementation demonstrated significantly greater improvements in VO2max compared with the control group. The effect size was large and statistically significant (SMD = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.60 to 1.31; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001), indicating a consistent enhancement of aerobic capacity across studies.

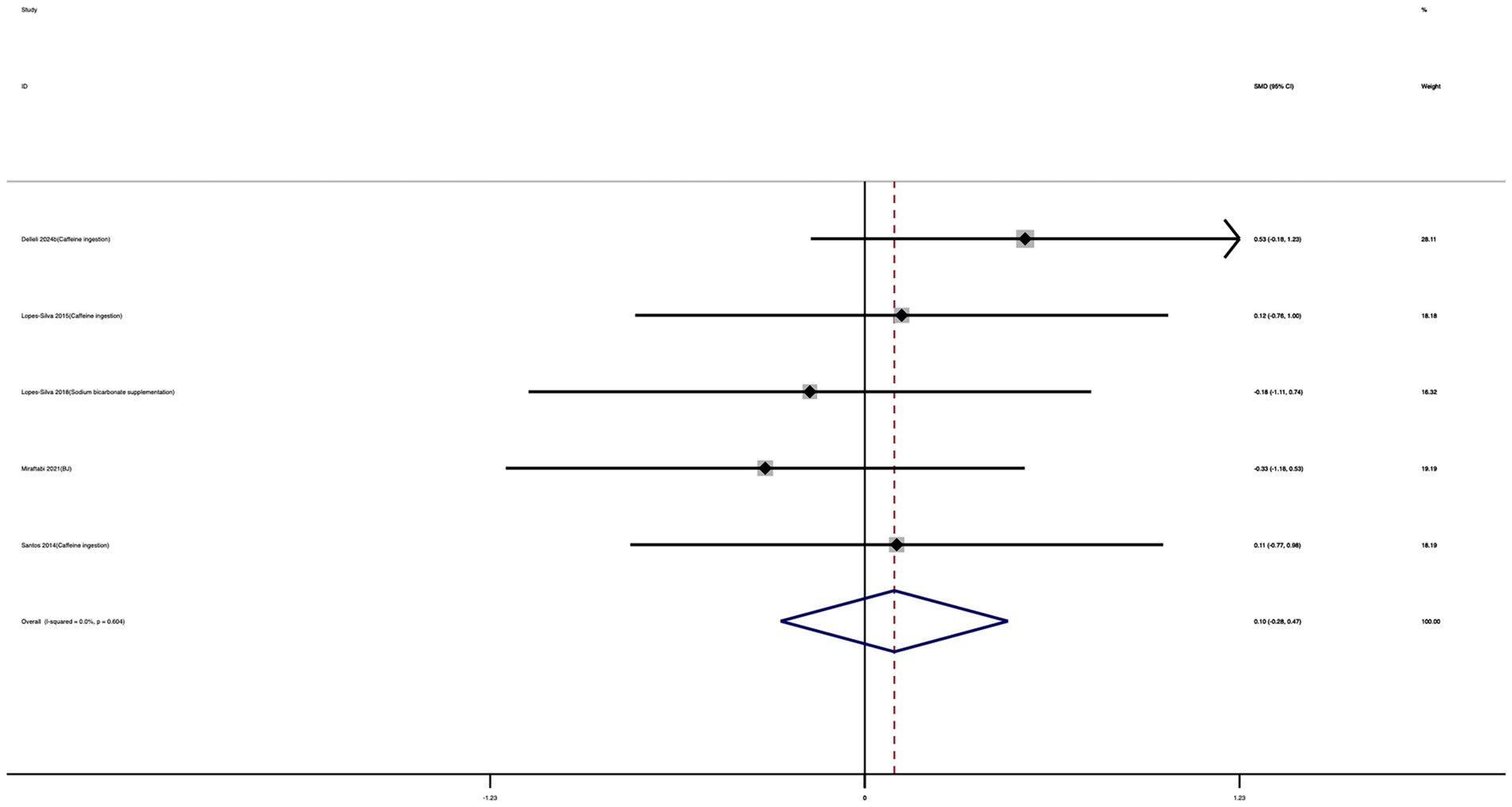

3.4.2.5 Improvement in mean heart rate

Five studies were included to explore the effect of nutritional supplementation on HR_mean. As shown in Figure 14, there was no significant difference between the supplementation and control groups. The effect size was negligible and not statistically significant (SMD = 0.10; 95% CI: −0.28 to 0.47; I2 = 0%; p = 0.611), with no heterogeneity detected.

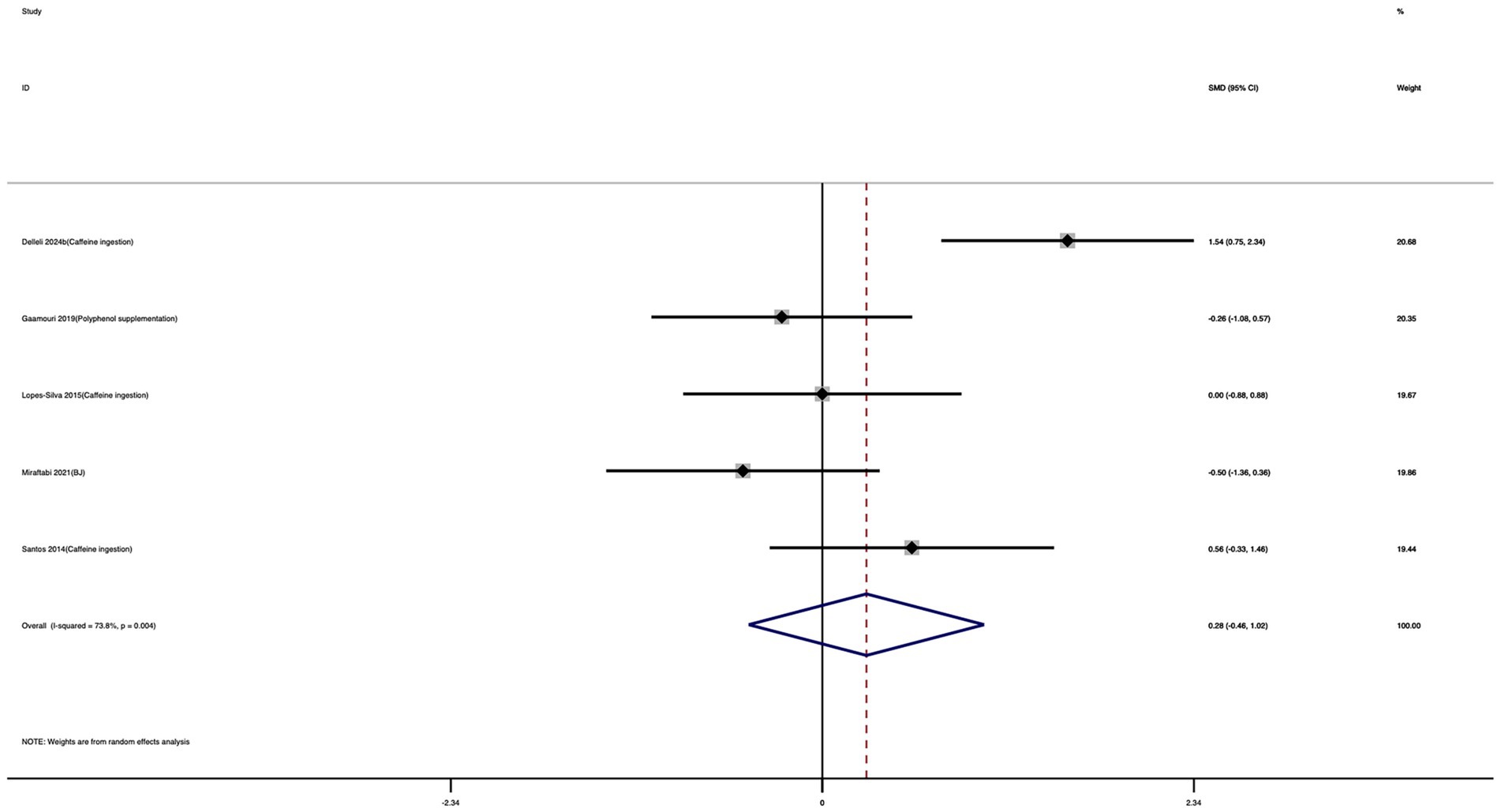

3.4.2.6 Improvement in peak heart rate

Five studies were included in the meta-analysis of HR_peak. As shown in Figure 15, nutritional supplementation did not significantly affect HR_peak compared with the control group. The effect size was small and not statistically significant (SMD = 0.28; 95% CI: −0.46 to 1.02; I2 = 73.8%; p = 0.463). Considerable heterogeneity was observed across studies, which may reflect variations in supplement type, dosage, and assessment protocols.

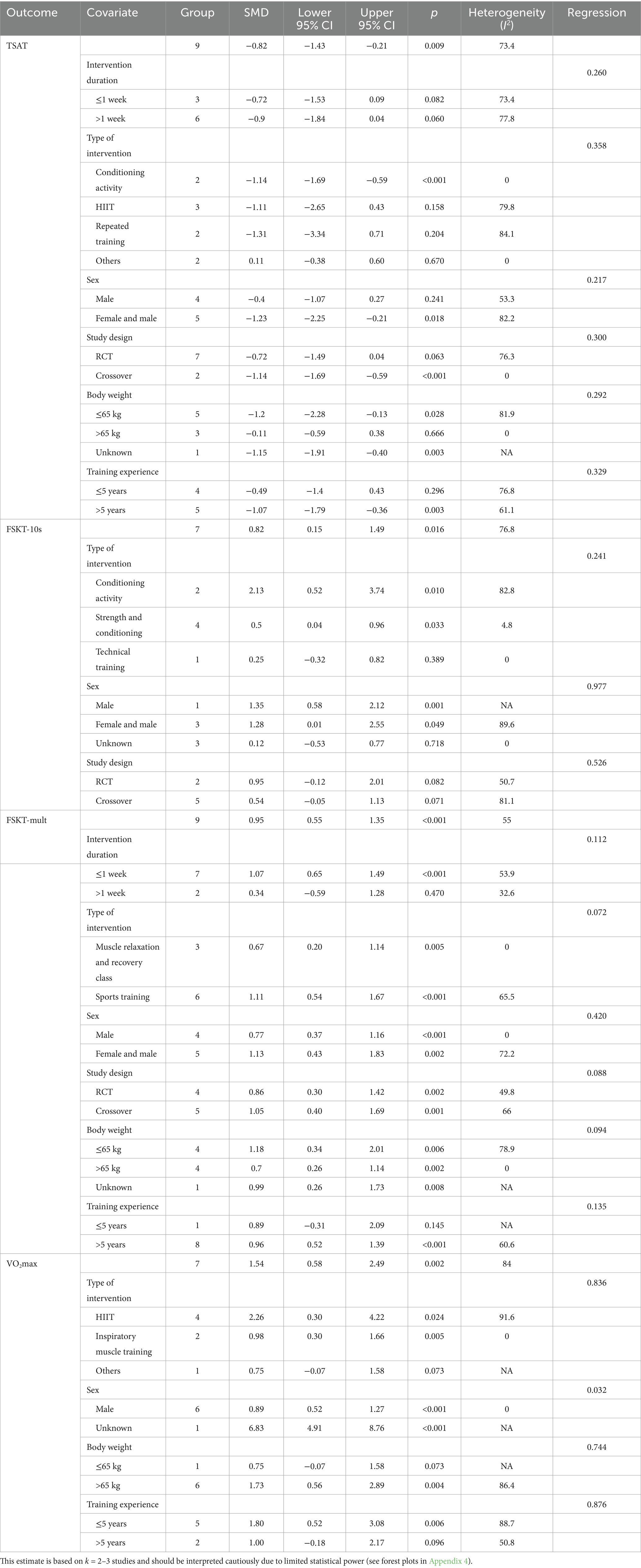

3.5 Subgroup analysis results

Given the substantial heterogeneity identified in the overall analysis, subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Subgroups were categorized based on intervention duration, type of exercise intervention, sex, study design, body weight, and training experience.

3.5.1 Subgroup analysis of exercise trainings

3.5.1.1 TSAT

A detailed subgroup analysis was conducted to examine the effects of exercise training on TSAT (see Table 5).

Intervention duration: When the duration was ≤1 week or >1 week, the effects were not statistically significant (SMD = −0.72; 95% CI: −1.53 to 0.09; I2 = 73.4%; p = 0.082) (SMD = −0.90; 95% CI: −1.84 to 0.04; I2 = 77.8%; p = 0.045), with high heterogeneity.

Type of intervention: Conditioning activity significantly improved TSAT (SMD = −1.14; 95% CI: −1.69 to −0.59; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity. In contrast, HIIT (SMD = −1.11; 95% CI: −2.65 to 0.43; I2 = 79.8%; p = 0.158), repeated training (SMD = −1.31; 95% CI: −3.34 to 0.71; I2 = 84.1%; p = 0.204), and other types (SMD = 0.11; 95% CI: −0.38 to 0.60; I2 = 0%; p = 0.670) showed no significant effects, with high heterogeneity in the former two.

Sex: Mixed-sex groups showed significant improvement in TSAT (SMD = −1.23; 95% CI: −2.55 to −0.21; I2 = 82.2%; p = 0.018), whereas male-only groups did not (SMD = −0.40; 95% CI: −1.07 to 0.27; I2 = 53.3%; p = 0.241), with high heterogeneity in both.

Study design: Crossover studies reported significant effects (SMD = −1.14; 95% CI: −1.69 to −0.58; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity, while RCTs did not reach significance (SMD = −0.72; 95% CI: −1.49 to 0.04; I2 = 76.3%; p = 0.063), with high heterogeneity.

Body weight: Significant effects were observed in studies with body weight ≤65 kg (SMD = −1.20; 95% CI: −2.28 to −0.13; I2 = 81.9%; p = 0.028) and unspecified weight (SMD = −1.15; 95% CI: −1.91 to −0.40; I2 = NA; p = 0.003), while no effect was seen in >65 kg groups (SMD = −0.11; 95% CI: −0.59 to 0.38; I2 = 0%; p = 0.666).

Training experience: Significant improvement in TSAT was found in >5-year experience groups (SMD = −1.07; 95% CI: −1.79 to −0.36; I2 = 61.1%; p = 0.003), while ≤5-year groups did not show significant results (SMD = −0.49; 95% CI: −1.40 to 0.43; I2 = 76.8%; p = 0.296).

3.5.1.2 FSKT-10s

Subgroup analysis results for the effect of exercise training on FSKT-10s are shown in Table 5.

Type of intervention: Conditioning activity and strength-and-conditioning significantly improved performance (SMD = 2.13; 95% CI: 0.52 to 3.74; I2 = 82.8%; p = 0.010) (SMD = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.96; I2 = 4.8%; p = 0.033). No significant effects were found for other types (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI: −0.32 to 0.82; I2 = 0%; p = 0.389).

Sex: Significant effects were observed in male-only groups (SMD = 1.35; 95% CI: 0.58 to 2.12; I2 = NA; p = 0.001) and mixed-sex groups (SMD = 1.28; 95% CI: 0.01 to 2.55; I2 = 89.6%; p = 0.049), with higher heterogeneity in the latter. No effect was found in groups with unspecified sex (SMD = 0.12; 95% CI: −0.53 to 0.77; I2 = 0%; p = 0.718).

Study design: Neither RCTs (SMD = 0.95; 95% CI: −0.12 to 2.01; I2 = 50.7%; p = 0.082) nor crossover designs (SMD = 0.54; 95% CI: −0.05 to 1.13; I2 = 81.1%; p = 0.071) reached statistical significance, both showing moderate-to-high heterogeneity.

3.5.1.3 FSKT-mult

To further clarify the effects of exercise training on FSKT-mult, subgroup analyses were conducted based on intervention duration, type, sex, study design, body weight, and training experience (see Table 5).

Intervention duration: Significant improvements were observed in studies with duration ≤1 week (SMD = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.65 to 1.49; I2 = 53.9%; p < 0.001), with moderate heterogeneity. No significant effect was found for >1 week (SMD = 0.34; 95% CI: −0.59 to 1.28; I2 = 32.6%; p = 0.470).

Type of intervention: Muscle-relaxation/recovery interventions significantly improved performance with no heterogeneity (SMD = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.20 to 1.14; I2 = 0%; p = 0.005). Sports training also showed significant improvement (SMD = 1.11; 95% CI: 0.54 to 1.67; I2 = 65.5%; p < 0.001), though with moderate heterogeneity.

Sex: Significant improvements were found in both male-only groups (SMD = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.37 to 1.16; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) and mixed-sex groups (SMD = 1.13; 95% CI: 0.43 to 1.83; I2 = 72.2%; p = 0.002), with higher heterogeneity in the latter.

Study design: Both RCTs (SMD = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.30 to 1.42; I2 = 49.8%; p = 0.002) and crossover designs (SMD = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.40 to 1.69; I2 = 66%; p = 0.001) showed significant effects with moderate heterogeneity.

Body weight: Significant effects were observed in ≤65 kg (SMD = 1.18; 95% CI: 0.34 to 2.01; I2 = 78.9%; p = 0.006), >65 kg (SMD = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.26 to 1.14; I2 = 0%; p = 0.002), and unspecified weight groups (SMD = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.26 to 1.73; I2 = NA; p = 0.008), with high heterogeneity in the ≤65 kg group.

Training experience: Significant effects were observed in >5-year groups (SMD = 0.96; 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.39; I2 = 60.6%; p < 0.001) with moderate heterogeneity, while no effect was found in ≤5-year groups (SMD = 0.89; 95% CI: −0.31 to 2.09; I2 = NA; p = 0.145).

3.5.1.4 VO2max

Subgroup analysis of VO2max was conducted based on intervention type, sex, body weight, and training experience (see Table 5).

Type of intervention: Both HIIT (SMD = 2.26; 95% CI: 0.30 to 4.22; I2 = 91.6%; p = 0.024) and inspiratory muscle training (SMD = 0.98 95% CI: 0.30 to 1.66; I2 = 0%; p = 0.005) significantly improved VO2max, though HIIT showed very high heterogeneity. Other types showed no significant effect (SMD = 0.75; 95% CI: −0.07 to 1.58; I2 = NA; p = 0.073).

Sex: Significant improvements were observed in male-only (SMD = 0.89; 95% CI: 0.52 to 1.27; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) and unspecified-sex groups (SMD = 6.83; 95% CI: 4.91 to 8.76; I2 = NA; p < 0.001).

Body weight: Significant improvement was found in >65 kg groups (SMD = 1.73; 95% CI: 0.56 to 2.89; I2 = 86.4; p = 0.004), with high heterogeneity. No significant effect was found in ≤65 kg groups (SMD = 0.75; 95% CI: −0.07 to 1.58; I2 = NA%; p = 0.073).

Training experience: In ≤5-year groups, VO₂max was significantly improved (SMD = 1.80; 95% CI: 0.52 to 3.08; I2 = 88.7%; p = 0.006), though heterogeneity was high. No significant effect was observed in >5-year groups (SMD = 0.99; 95% CI: −0.18 to 2.17; I2 = 50.8%; p = 0.096), with moderate heterogeneity.

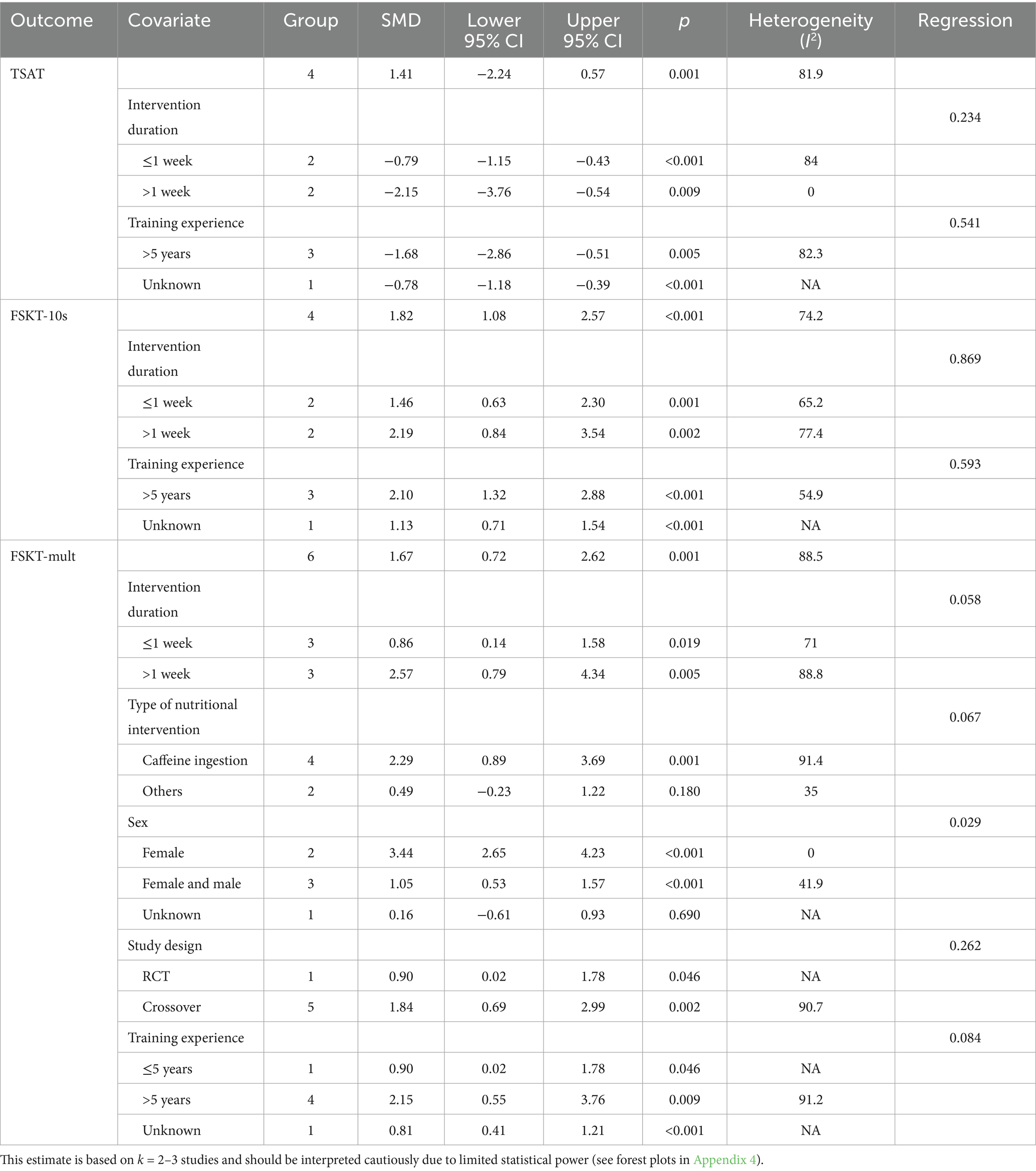

3.5.2 Subgroup analysis of nutritional supplementations

To further explore the effects of nutritional supplementation on TSAT, FSKT-10s and FSKT-mult performance in taekwondo athletes, subgroup analyses were conducted based on intervention duration, type of nutritional intervention, sex, study design, and training experience. Detailed results are presented in Table 6.

3.5.2.1 TSAT

Subgroup analysis of TSAT was based on intervention duration and training experience, with the following results.

Intervention duration: Nutritional supplementation significantly improved TSAT performance in both the ≤1 week subgroup (SMD = −0.79; 95% CI: −1.15 to −0.43; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) and the >1 week subgroup (SMD = −2.15; 95% CI: −3.76 to −0.51; I2 = 84%; p = 0.009), with low heterogeneity in the 1 week subgroup.

Training experience: Significant improvements were observed in the >5 years subgroup (SMD = −1.68; 95% CI: −2.86 to −0.51; I2 = 82.3%; p = 0.005) and the unspecified training experience subgroup (SMD = −0.78; 95% CI: −1.18 to −0.39; I2 = NA; p < 0.001), though the former exhibited high heterogeneity.

3.5.2.2 FSKT-10s

Subgroup analysis of FSKT-10s was based on intervention duration and training experience, with the following results.

Intervention duration: Nutritional supplementation significantly improved FSKT-10s performance in both the ≤1 week subgroup (SMD = 1.46; 95% CI: 0.63 to 2.30; I2 = 65.2%; p = 0.001) and the >1 week subgroup (SMD = 2.19; 95% CI: 0.84 to 3.54; I2 = 77.4%; p = 0.002), although both exhibited moderate-to-high heterogeneity.

Training experience: Significant improvements were observed in the >5 years subgroup (SMD = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.32 to 2.83; I2 = 54.9%; p < 0.001) and the unspecified training experience subgroup (SMD = 1.13; 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.54; I2 = NA; p < 0.001).

3.5.2.3 FSKT-mult

Subgroup analysis of FSKT-mult was conducted across five covariates: intervention duration, type of nutritional intervention, sex, study design, and training experience.

Intervention duration: Nutritional supplementation significantly enhanced FSKT-mult performance in both the ≤1 week subgroup (SMD = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.14 to 1.58; I2 = 71%; p = 0.019) and the >1 week subgroup (SMD = 2.57; 95% CI: 0.79 to 4.34; I2 = 88.8%; p = 0.005), both showing high heterogeneity.

Type of nutritional intervention: Caffeine ingestion significantly improved FSKT-mult performance (SMD = 2.29; 95% CI: 0.89 to 3.69; I2 = 91.4%; p = 0.001), though heterogeneity was high. No significant effect was observed for other supplement types (SMD = 0.49; 95% CI: −0.23 to 1.22; I2 = 35%; p = 0.180).

Sex: Nutritional supplementation significantly improved FSKT-mult in both female groups (SMD = 3.44; 95% CI: 2.65 to 4.23; I2 = 0%; p < 0.001) and mixed-sex groups (SMD = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.53 to 1.57; I2 = 41.9%; p < 0.001), with higher heterogeneity in the latter. No significant effect was found in unspecified-sex groups (SMD = 0.16; 95% CI: −0.61 to 0.93; I2 = NA; p = 0.690).

Study design: Nutritional supplementation was effective in both RCTs (SMD = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.02 to 1.78; I2 = NA; p = 0.046) and crossover studies (SMD = 1.84; 95% CI: 0.69 to 2.99; I2 = 90.7%; p = 0.002), though the latter exhibited high heterogeneity.

Training experience: FSKT-mult performance was significantly improved in the ≤5 years subgroup (SMD = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.02 to 1.78; I2 = NA; p = 0.046), the >5 years subgroup (SMD = 2.15; 95% CI: 0.55 to 3.76; I2 = 91.2%; p = 0.009), and the unspecified experience subgroup (SMD = 0.81; 95% CI: 0.41 to 1.21; I2 = NA; p < 0.001).

For a detailed summary of effect sizes and subgroup comparisons, please refer to Table 6.

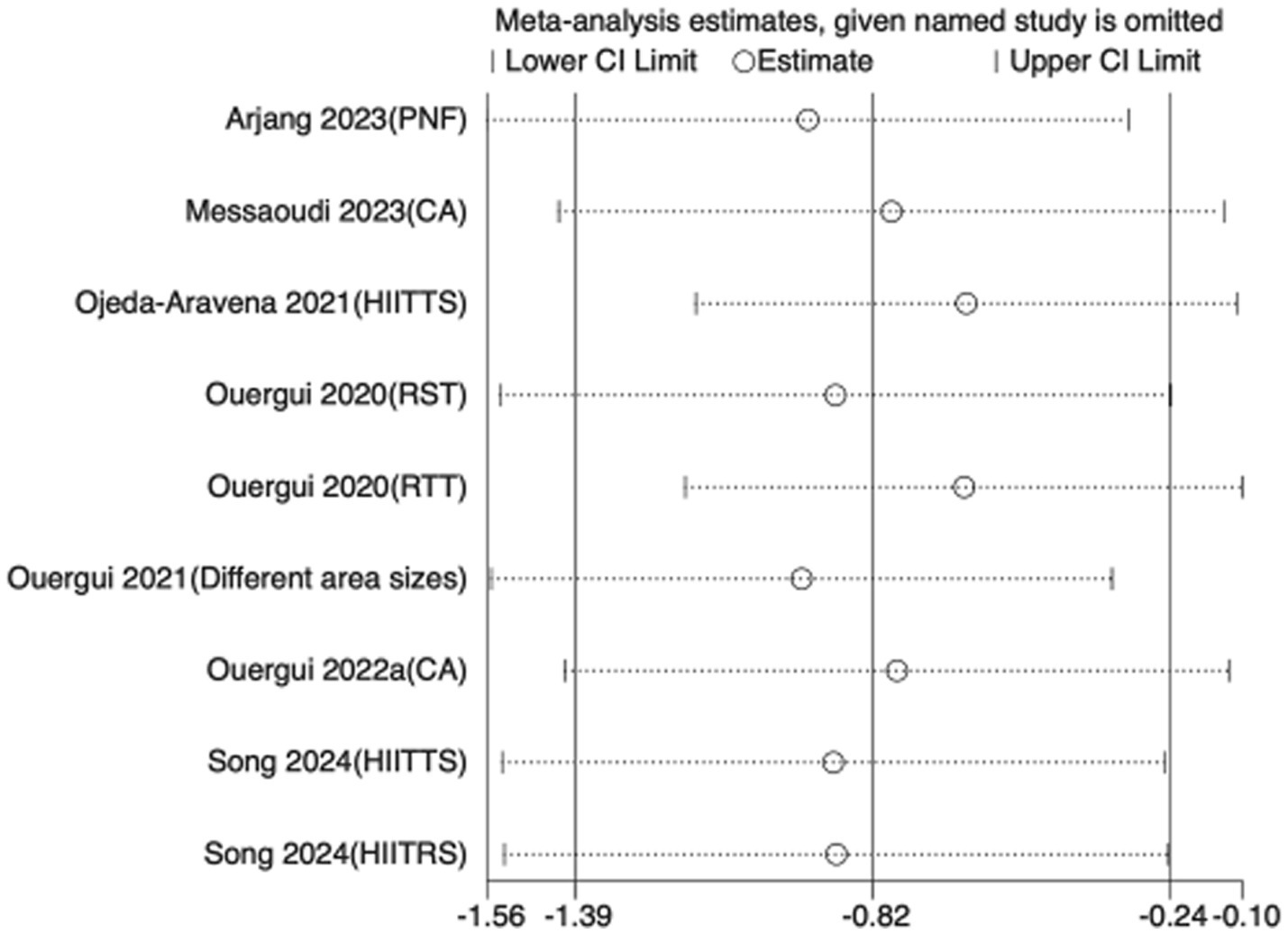

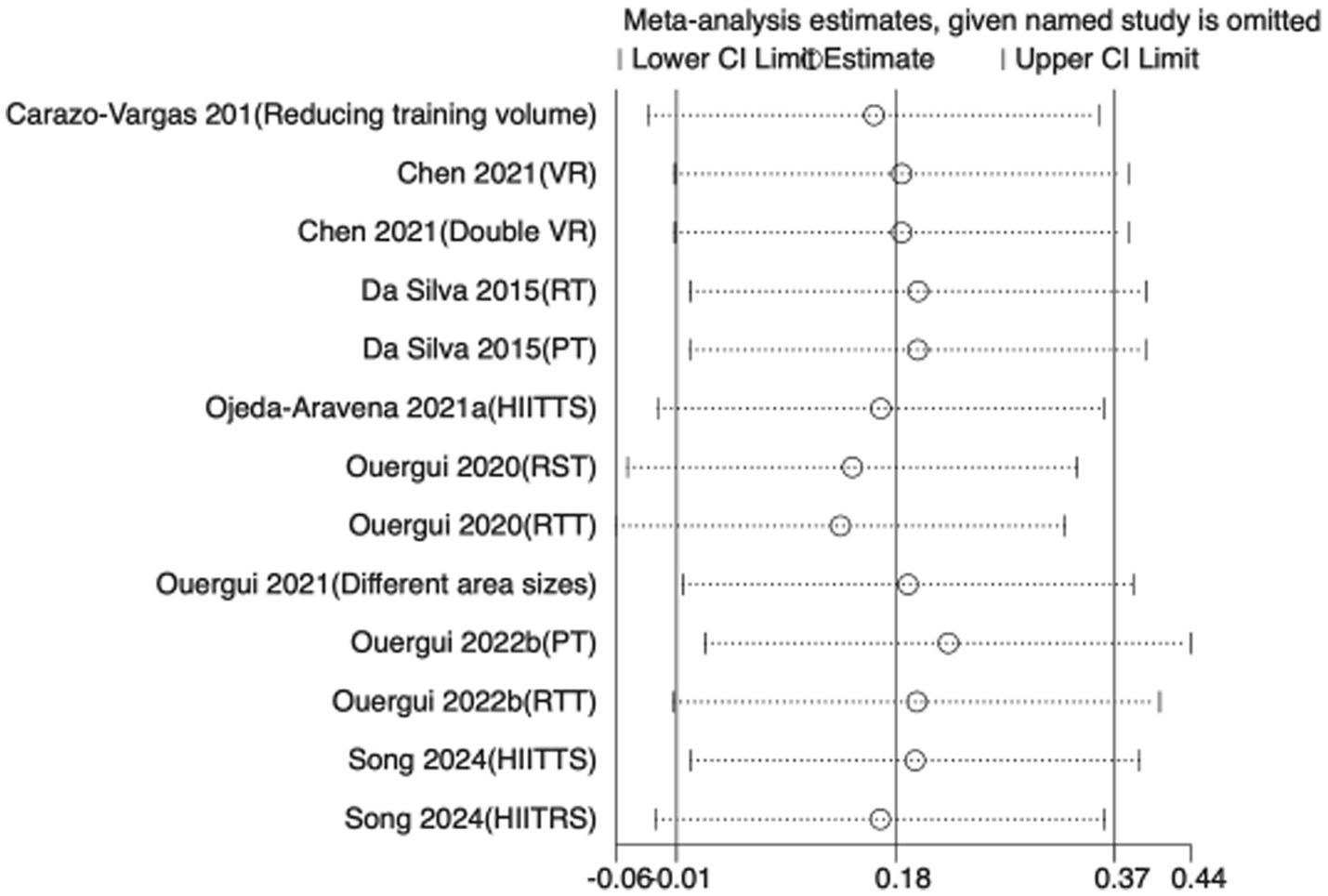

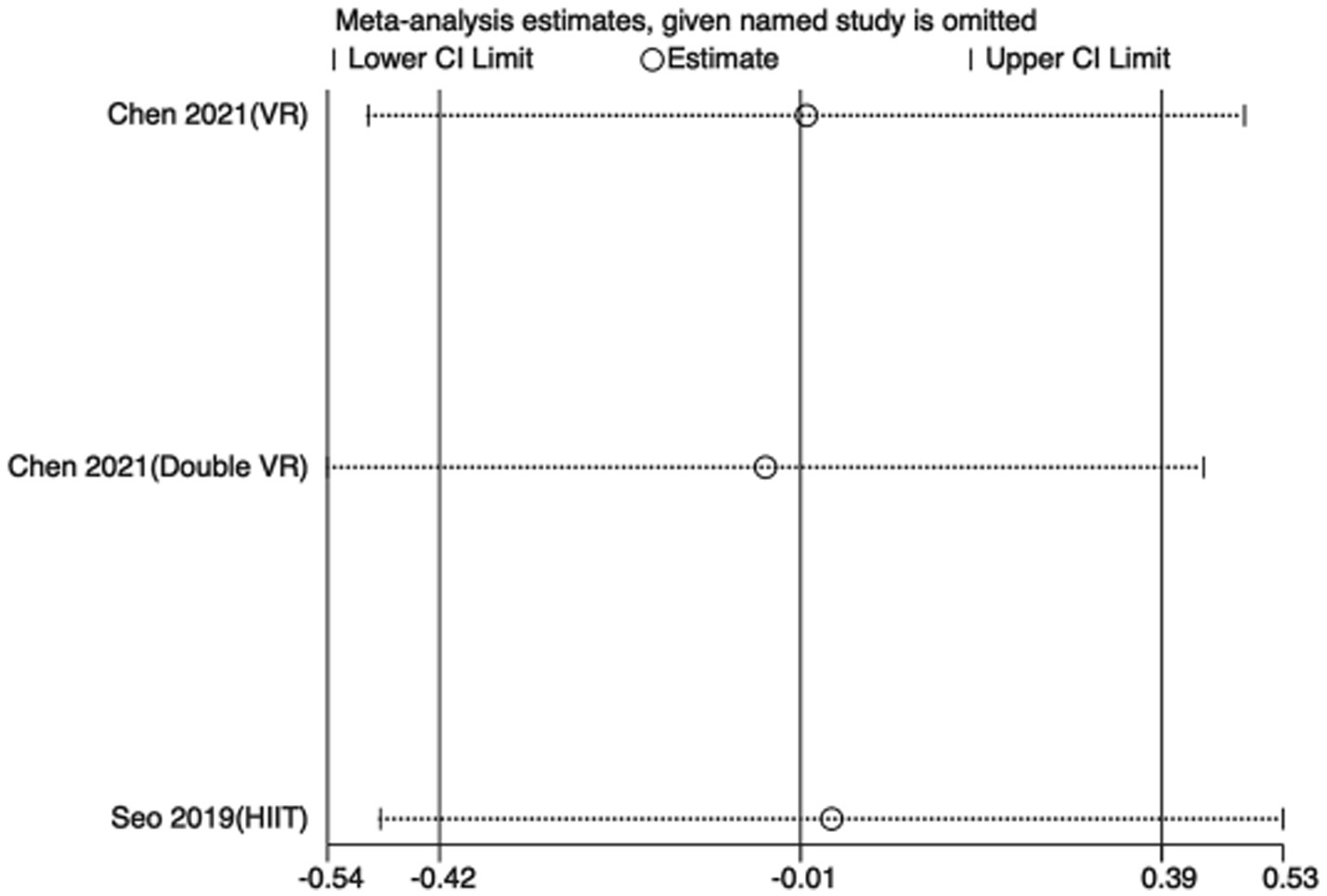

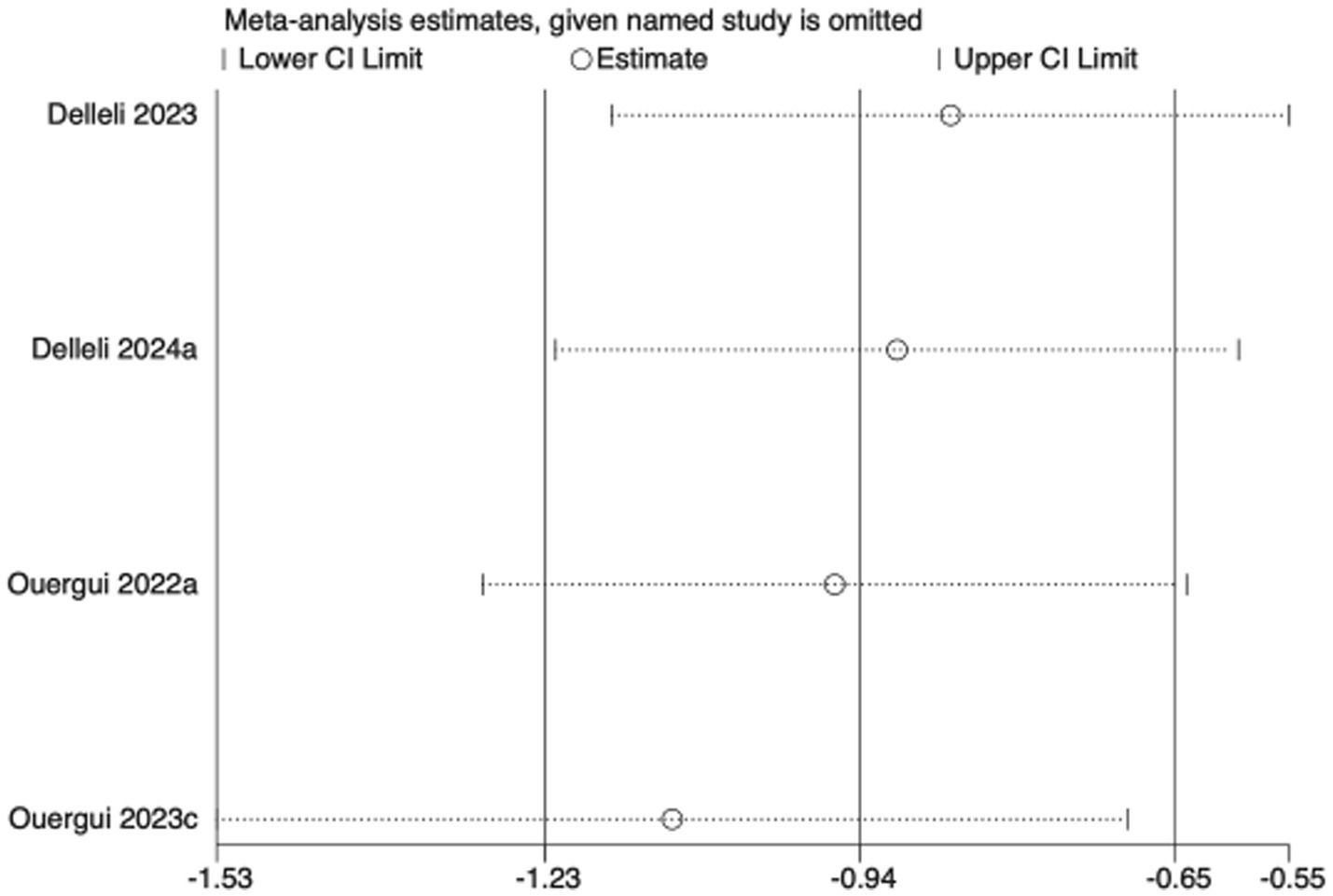

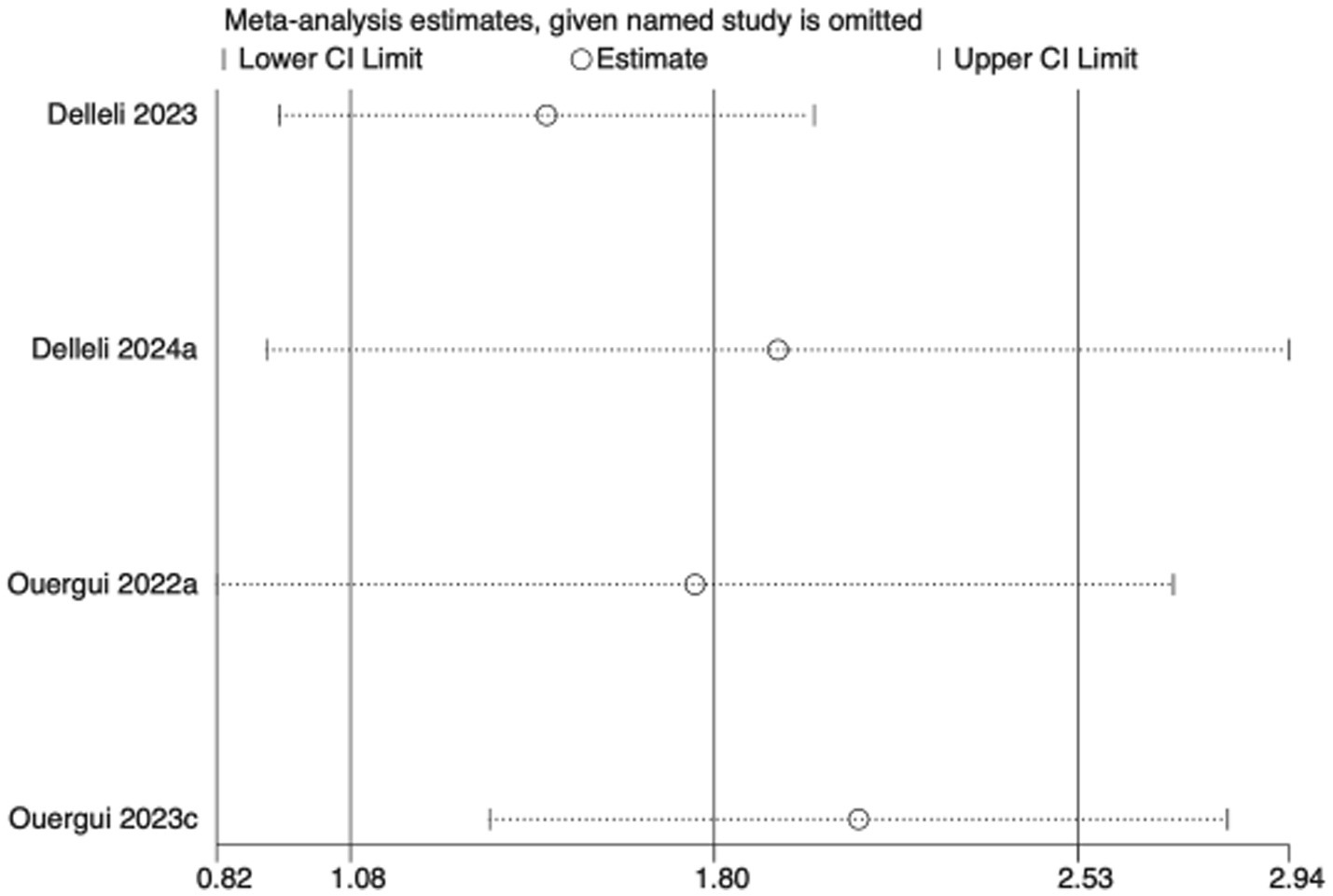

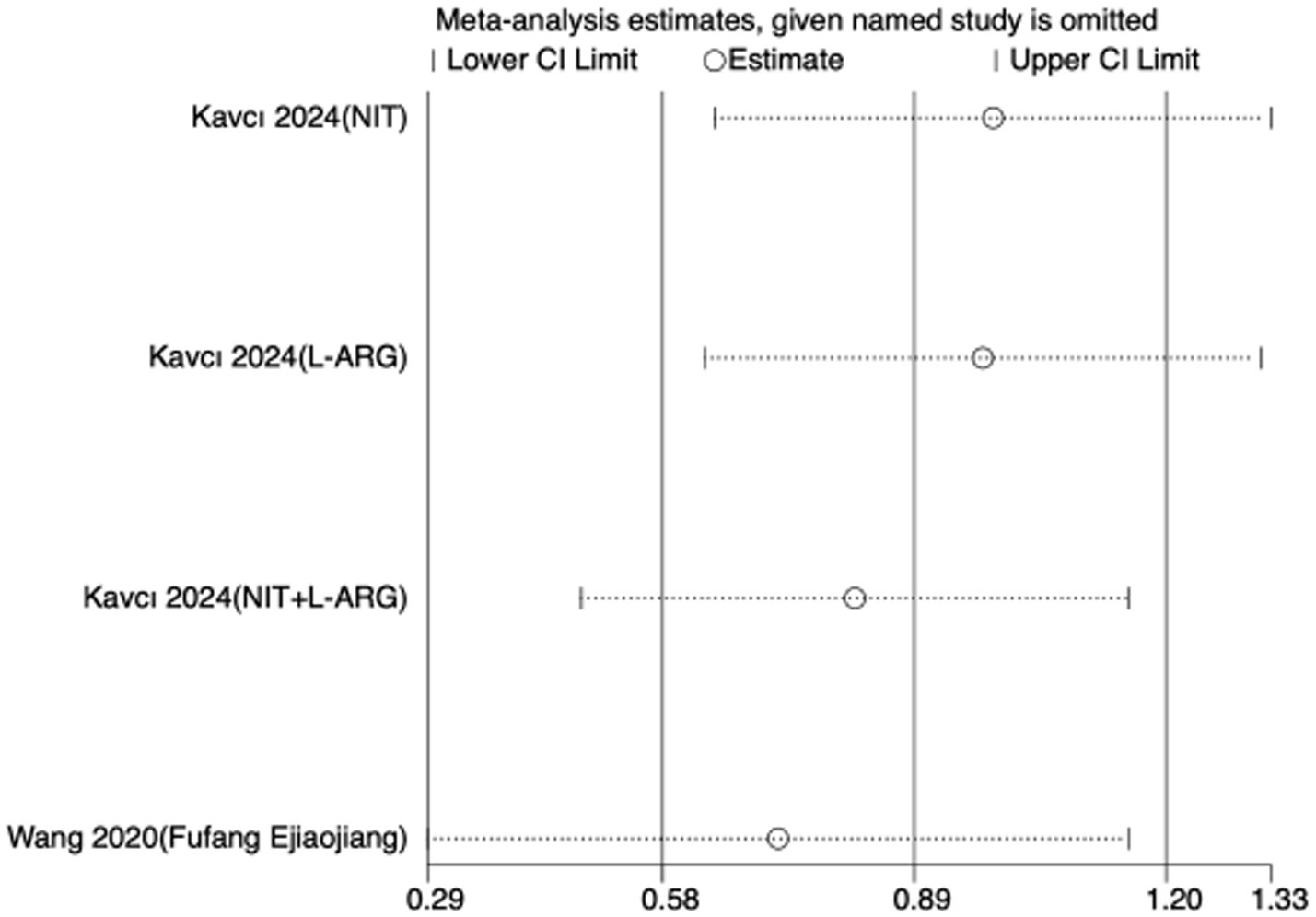

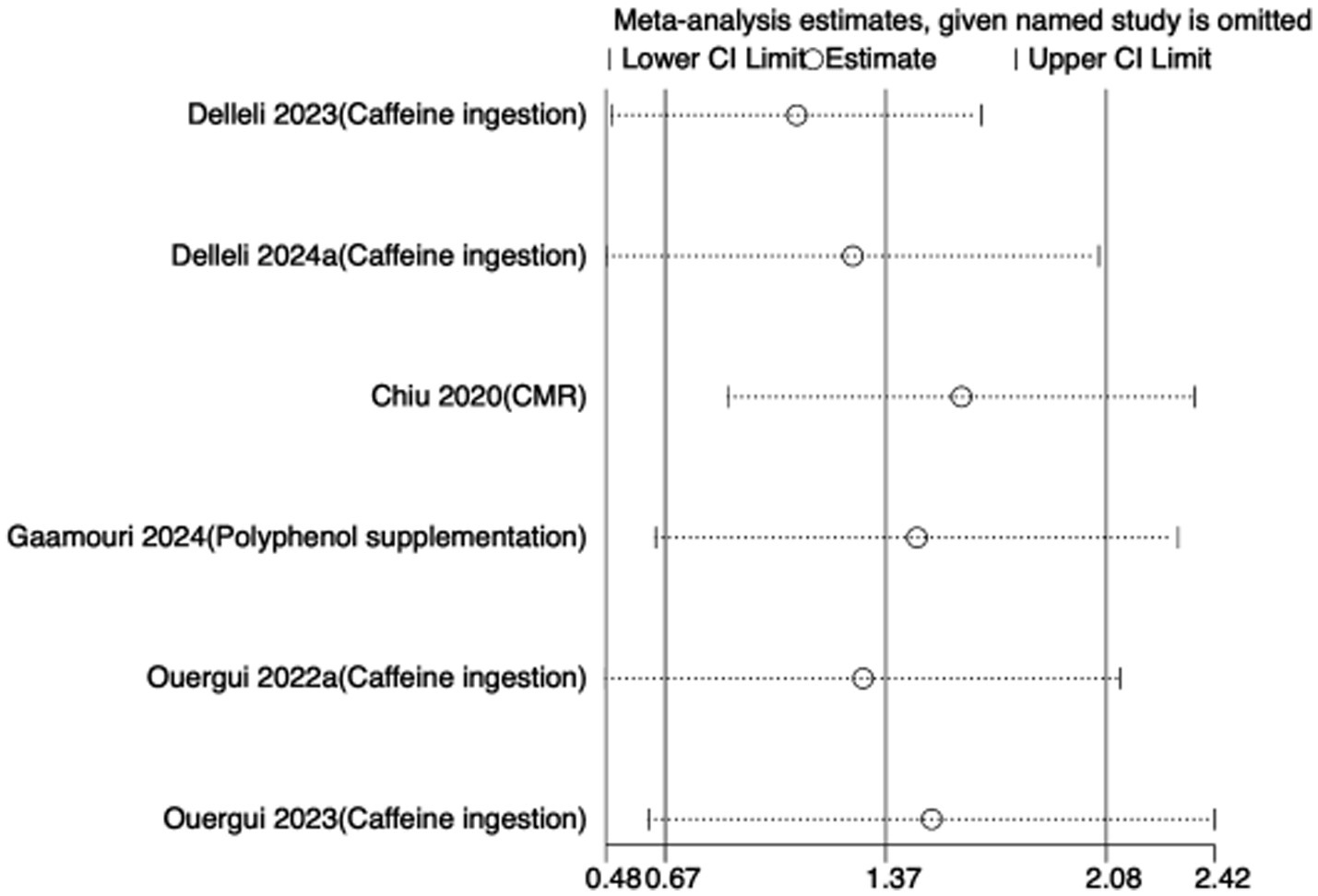

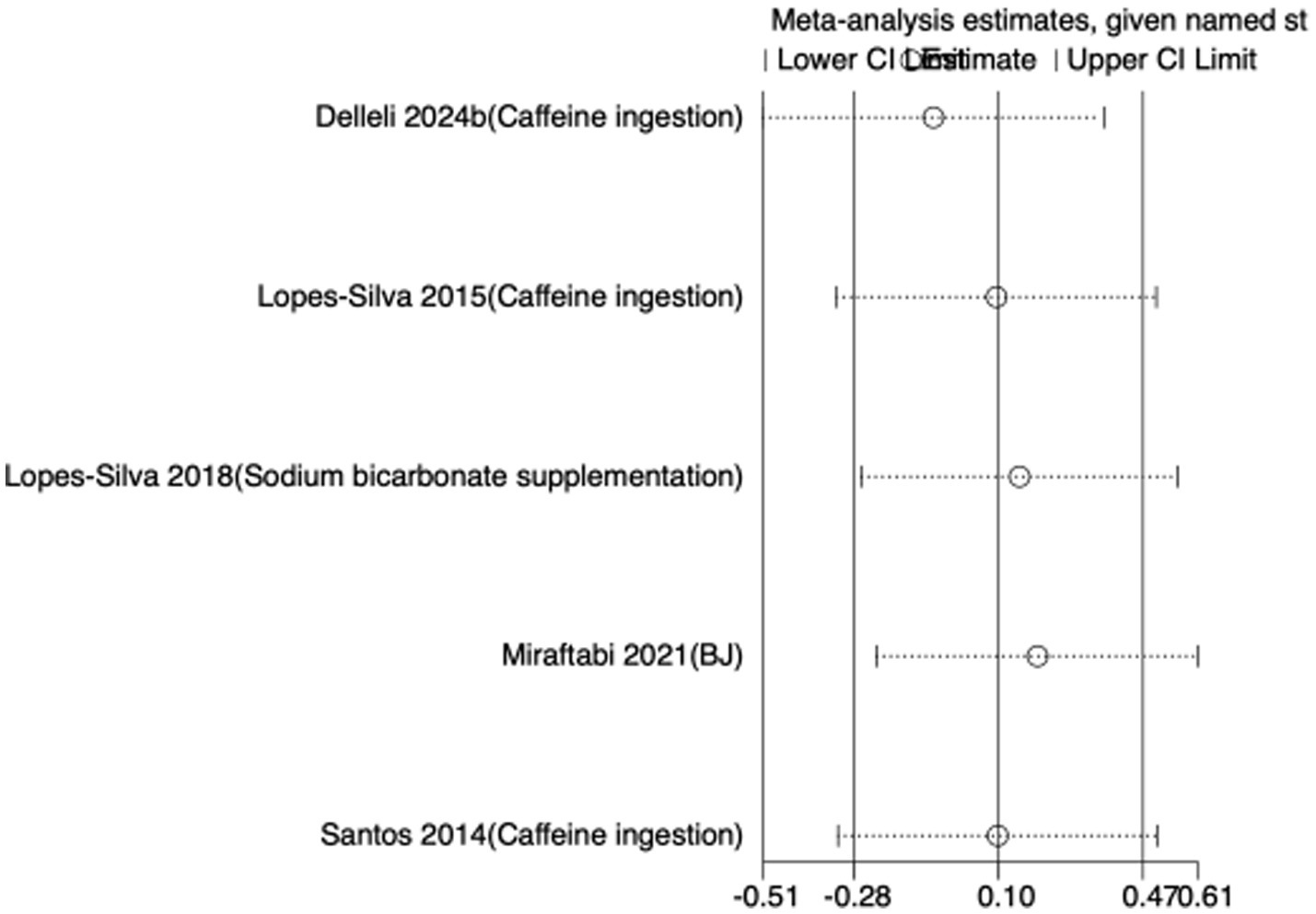

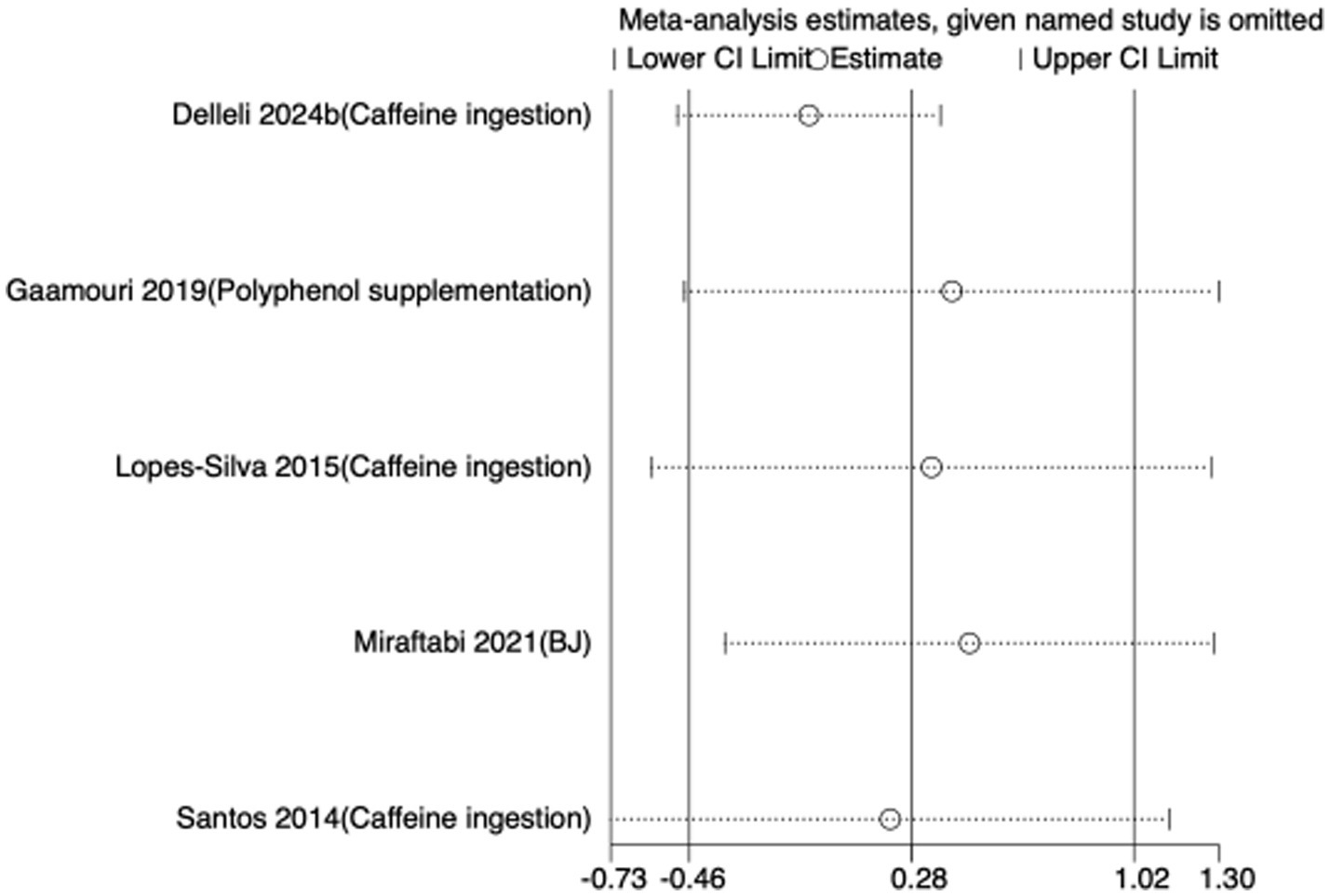

3.6 Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of the meta-analytic findings, sensitivity analyses were performed for all performance-related outcomes in taekwondo athletes. The analyses involved sequentially removing each individual study to examine whether the pooled effect size remained stable—that is, whether the revised estimate after exclusion stayed within the 95% CI of the overall pooled effect.

The results indicated that the exclusion of any single study did not substantially alter the direction or magnitude of the overall effects, suggesting that the findings of this meta-analysis are robust and not unduly influenced by any single trial. Sensitivity analysis results for exercise training are presented in Figures 16–21, and those for nutritional supplementation are shown in Figures 22–27.

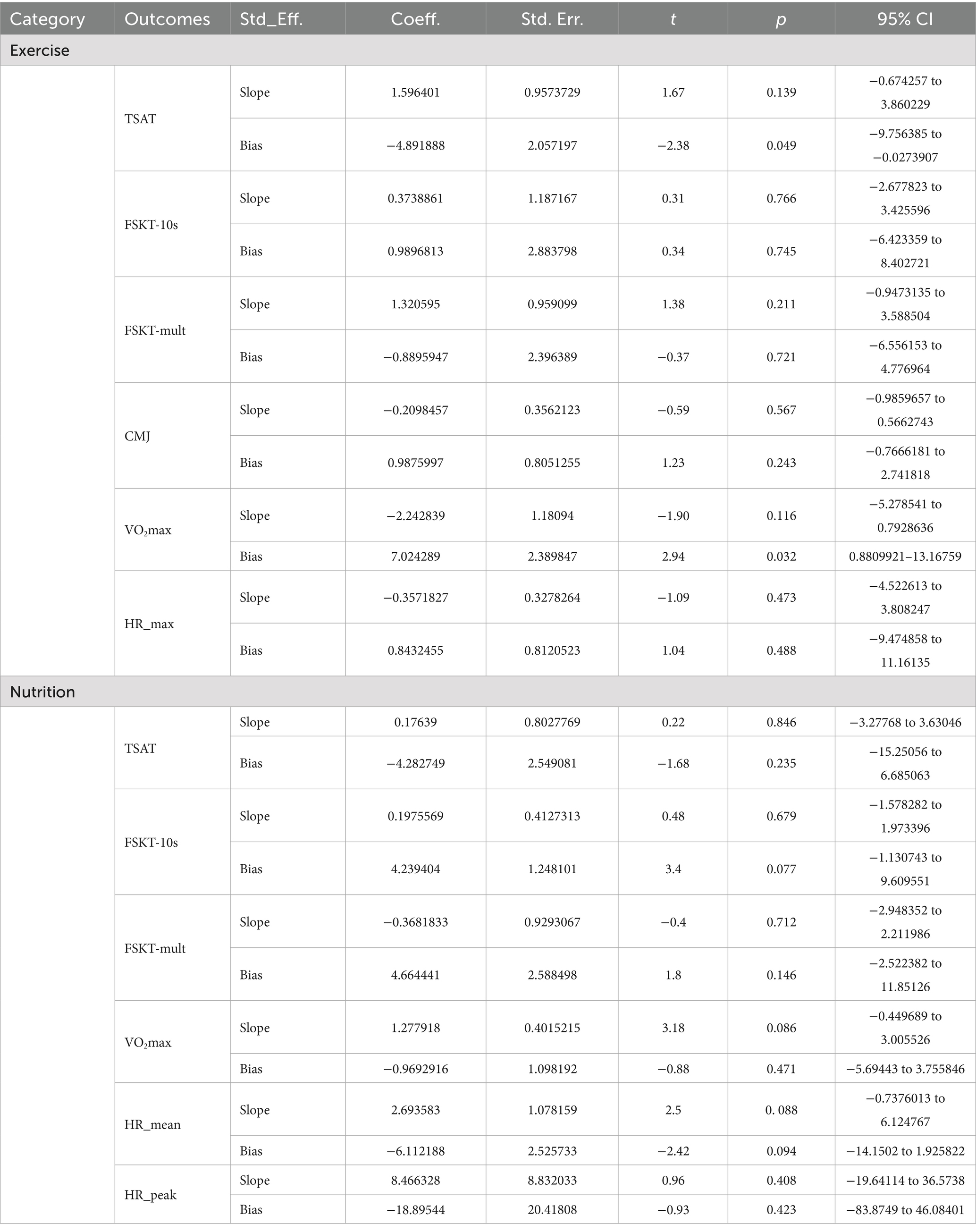

3.7 Publication bias assessment

To further assess the potential presence of publication bias, Egger’s regression test and Begg’s rank correlation test were employed for quantitative evaluation. The Egger’s test results for each outcome are summarized in Table 7.

Overall, all Egger’s test p-values were greater than 0.05—except for TSAT (p = 0.049) and VO2max (p = 0.032) in the exercise intervention subgroup—indicating no significant evidence of publication bias for most outcomes.

For the two potentially biased outcomes (TSAT and VO2max), the trim-and-fill method was applied for adjustment. The results revealed that no missing studies were imputed, and the adjusted pooled estimates changed from TSAT: SMD = −0.82 (95% CI: −1.43 to −0.21; p = 0.009) to SMD = 0.44 (95% CI: 0.24 to 0.81; p = 0.009), and from VO2max: SMD = 1.54 (95% CI: 0.58 to 2.49; p = 0.002) to SMD = 4.65 (95% CI: 1.79 to 12.08; p = 0.002).

The consistency of statistical significance and direction before and after adjustment suggests that the potential publication bias for TSAT and VO2max is minimal and has negligible impact on the final conclusions.

Additionally, Begg’s funnel plots were generated to visually inspect publication bias. Most studies were symmetrically distributed within the 95% CI range, and no substantial asymmetry was detected in the funnel plots, confirming the absence of major bias. Detailed results are presented in Appendix 5.

4 Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the effects of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on physical performance in taekwondo athletes using a meta-analytic approach. Key performance indicators—including TSAT, FSKT, CMJ, VO2max, and HR—were analyzed to provide evidence-based insights into sport-specific and physiological adaptations. Despite the widespread use of both exercise and nutritional interventions in combat sports, their combined or comparative impacts in taekwondo have remained underexplored. The present meta-analysis further examined moderating factors such as intervention duration, type, sex, body weight, and training experience, thereby offering implications for individualized and evidence-based conditioning strategies.

4.1 Main findings

4.1.1 Effects of exercise training

Exercise training significantly improved TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult, and VO2max, confirming its pivotal role in enhancing both agility and aerobic capacity. These findings align with prior evidence showing that resistance, plyometric, and HIIT programs markedly enhance agility and sport-specific speed performance (64–68). Agility, reflecting rapid directional changes and neuromuscular control, is a key determinant of competitive success in taekwondo (67, 68). Improvements in FSKT likely stem from enhanced lower-limb strength, neuromuscular coordination, and anaerobic endurance, as both resistance and HIIT training promote muscle power and fatigue tolerance (69, 70).

The effect on CMJ was small and statistically non-significant, consistent with mixed findings in earlier studies (71–73). This may reflect the limited sensitivity of CMJ to short-term or non-specific interventions that fail to replicate taekwondo’s explosive movement patterns. Conversely, the substantial improvement in VO2max supports prior findings that HIIT elicits superior aerobic adaptations compared with steady-state endurance training (66, 74–76). The non-significant changes in HRmax are consistent with evidence suggesting that short-term interventions may not induce measurable cardiac remodeling (37, 77–80).

Physiologically, exercise-induced performance enhancement is mediated by mitochondrial biogenesis, increased capillary density, elevated cardiac output, and neural activation through resistance or plyometric loading (81–84). Moreover, exercise-induced myokines such as IL-6 and irisin (FNDC5) enhance metabolic efficiency, regulate substrate utilization, and delay fatigue (85, 86). Collectively, these findings underscore that systematic and periodized exercise training is fundamental to improving both agility and aerobic fitness in taekwondo athletes.

4.1.2 Main findings of nutritional supplementations

Nutritional supplementation—particularly caffeine—also produced significant improvements in TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult, and VO2max. The ergogenic effects of caffeine, previously shown to enhance agility, endurance, and fatigue resistance (87–90), are largely mediated by increased calcium release, stimulation of Na+/K+-ATPase activity, and central nervous system arousal (91–93). These effects appear more pronounced in male athletes and occur even at relatively low doses (0.9–2 mg/kg) (88, 89).

The observed increase in VO2max following nitrate or Ejiao supplementation supports evidence that enhanced oxygen transport, improved redox balance, and elevated nitric oxide bioavailability can facilitate endurance performance (94, 95). However, no significant effects were observed for HRmean or HRpeak (96, 97), likely due to small sample sizes, variable testing protocols, and short intervention durations. Similarly, vitamin D supplementation did not improve CMJ, echoing recent findings that vitamin D may exert limited ergogenic influence in well-trained populations (46, 98–100).

Other bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols and dietary nitrates, may further augment performance by promoting vasodilation, reducing oxidative stress, and enhancing muscle oxygenation (101–104). Overall, both exercise and supplementation improved taekwondo performance, though exercise training was more effective for agility and VO2max, while caffeine supplementation provided superior benefits for repeated kicking performance (FSKT).

4.2 Subgroup analysis interpretation

4.2.1 Exercise training subgroups

Subgroup analyses revealed that intervention duration, type, sex, study design, body weight, and training experience moderated the effects of exercise training. Short-term interventions (≤1 week) yielded greater improvements in FSKT-mult, possibly reflecting acute neuromuscular potentiation and fatigue recovery, whereas longer-term programs were required for substantial agility gains (TSAT). Conditioning activities enhanced both TSAT and FSKT-10s, while HIIT and inspiratory muscle training produced the largest VO2max gains (105–107).

Male athletes exhibited smaller improvements in agility, likely due to higher baseline neuromuscular power, while lighter athletes (≤65 kg) achieved greater agility benefits and heavier athletes (>65 kg) improved VO₂max, possibly reflecting differences in body composition and oxygen utilization efficiency. Athletes with >5 years of experience demonstrated superior gains in agility and anaerobic performance, whereas less experienced athletes exhibited larger aerobic adaptations (70, 108, 109).

These results highlight the necessity of experience- and physiology-specific training prescriptions to maximize taekwondo performance.

4.2.2 Nutritional supplementation subgroups

Both short- and long-term nutritional interventions enhanced agility and repeated kicking performance, reflecting improvements in energy metabolism, oxygen utilization, and fatigue resistance (90). Caffeine supplementation produced the most consistent effects on FSKT-mult, attributable to enhanced calcium ion kinetics, increased motor unit recruitment, and delayed central fatigue (110, 111).

Future studies should explore synergistic combinations of ergogenic aids (e.g., caffeine with nitrates or amino acids) to determine additive effects across performance domains and metabolic pathways.

4.3 Strengths, limitations, and future perspectives

This meta-analysis represents the first comprehensive synthesis of both exercise and nutritional interventions targeting taekwondo athletes. It integrated six key physiological and performance indicators, thereby offering an evidence-based framework for optimizing training and supplementation strategies in combat sports.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, considerable heterogeneity in study design, sample size, and measurement protocols may affect the generalizability of findings. Second, most studies investigated single interventions with short-term follow-up, precluding conclusions about long-term or combined effects. Third, several subgroup analyses were based on small samples (k = 2–3), limiting statistical power and precision; these results should therefore be interpreted as exploratory. Fourth, although publication bias was generally low, the restriction to English-language, peer-reviewed studies may still have introduced selection bias.

Future research should focus on large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials employing standardized testing and longitudinal tracking. Integrating physiological, biochemical, and psychological indicators will yield a more comprehensive understanding of performance adaptations. Moreover, AI-driven analytics and wearable technology could enable real-time performance monitoring, predictive modeling, and precision-tailored training or nutrition interventions, ultimately advancing the scientific basis for elite taekwondo performance optimization.

5 Conclusion

Exercise training significantly improved TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult, and VO₂max, while CMJ and HRmax showed no significant effects. Nutritional supplementation, especially caffeine, enhanced TSAT, FSKT-10s, FSKT-mult, and VO₂max but did not affect HRmean or HRpeak.

Despite methodological heterogeneity, these findings offer practical, evidence-based guidance for designing integrated conditioning and supplementation strategies in taekwondo. Tailoring programs to athlete characteristics, experience level, and physiological demands may further enhance performance outcomes.

Data availability statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

CX: Formal analysis, Resources, Visualization, Software, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization, Validation. WZ: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Resources, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization. LL: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project No. 72364006), which covered the article processing charge.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools were utilized to assist with English translation and proofreading in this study (or project) to enhance linguistic accuracy and expression clarity. The final responsibility for the scientific integrity, accuracy, and validity of the work rests solely with the authors.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1618612/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Bridge, CA, da Silva, F, Santos, J, Chaabène, H, Pieter, W, and Franchini, E. Physical and physiological profiles of taekwondo athletes. Sports Med. (2014) 44:713–33. doi: 10.1007/s40279-014-0159-9,

2. Marković, G, Misigoj-Duraković, M, and Trninić, S. Fitness profile of elite Croatian female taekwondo athletes. Coll Antropol. (2005) 29:93–9.

3. Yang, W-H, Grau, M, Kim, P, Schmitz, A, Heine, O, Bloch, W, et al. Physiological and psychological performance of taekwondo athletes is more affected by rapid than by gradual weight reduction. Arch Budo. (2014) 10:169–77.

4. Janowski, M, Zieliński, J, Ciekot-Sołtysiak, M, Schneider, A, Kusy, K, and Zieliński, P. The effect of sports rules amendments on exercise response patterns in taekwondo athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:6779. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186779

5. Ouergui, I, Delleli, S, Bouassida, A, Bouhlel, E, Franchini, E, Gmada, N, et al. Acute effects of different activity types and work-to-rest ratios on post-activation performance enhancement and hemoglobin oxygen saturation recovery in taekwondo athletes. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:805680. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.805680

6. Chaabene, H, Negra, Y, Bouguezzi, R, Capranica, L, Franchini, E, Prieske, O, et al. Validity and reliability of a new test of planned agility in elite taekwondo athletes. J Strength Cond Res. (2018) 32:2542–7. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002129

7. da Silva Santos, JF, Herrera-Valenzuela, T, Ribeiro da Mota, G, and Franchini, E. Test-retest reliability, sensibility and construct validity of the frequency speed of kick test in male black-belt taekwondo athletes. Ido Mov Cult. (2020) 20:53–9. doi: 10.14589/ido.20.4.8

8. de Oliveira Goulart, KN, de Jesus, K, Muniz Caldeira, LF, Dantas, NL, Bezerra, P, and da Silva, SF. Correlation between roundhouse kick and countermovement jump performance. Rev Artes Marciales Asiat. (2016) 11:104–5. doi: 10.18002/rama.v11i2s.4190

9. Antonietto, DÁ, Santos, JFS, Tavares, AF, and Franchini, E. Can the countermovement jump or squat jump be used to predict taekwondo kick performance? Retos. (2024) 51:1056–63. doi: 10.47197/retos.v51.99831

10. Haddad, M, Chaouachi, A, Castagna, C, Wong, DP, Behm, DG, and Chamari, K. Heart rate responses and training load during nonspecific and specific aerobic training in adolescent taekwondo athletes. J Hum Kinet. (2011) 29:59–66. doi: 10.2478/v10078-011-0044-y

11. Rocha, FPS, Louro, H, Matias, R, Costa, AM, and Matias, CN. Determination of aerobic power through a specific test for taekwondo: a predictive equation model. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0151738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151738

12. McLaughlin, A. The physical and physiological demands of taekwondo: a comparison of male and female athletes In: Doctoral dissertation. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University (2020)

13. Ölmez, C, Akyildiz, Z, Açikada, C, Çene, E, Birinci, MC, and Pinar, S. Development of the taekwondo performance protocol to determine aerobic power in taekwondo athletes. Balt J Health Phys Act. (2023) 15:5. doi: 10.29359/BJHPA.2023.15.1.05

14. Apollaro, G, Mascherini, G, Petri, C, Modugno, A, Stamatelopoulou, K, Puce, L, et al. Validity of aerobic capacity indicators derived from the progressive specific taekwondo test in young taekwondo athletes. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. (2025) 17:19. doi: 10.1186/s13102-025-01086-x

15. Sousa, JL, Nunes, C, Iglésias, B, Costa, C, and Sampaio, J. Design and validation of an instrument for technical and tactical performance analysis in taekwondo. Appl Sci. (2022) 12:7675. doi: 10.3390/app12157675

16. Reale, R, Slater, G, and Burke, LM. Acute-weight-loss strategies for combat sports and applications to Olympic success. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2017) 12:142–51. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2016-0211,

17. Barley, OR, Chapman, DW, and Abbiss, CR. Weight loss strategies in combat sports and concerning habits in mixed martial arts. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2018) 13:933–9. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0715,

18. Franchini, E, Cormack, S, and Takito, MY. Effects of high-intensity interval training on Olympic combat sports athletes' performance and physiological adaptation: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res. (2019) 33:242–52. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002957,

19. Cid-Calfucura, I, Herrera-Valenzuela, T, Franchini, E, Falco, C, Alvial-Moscoso, J, Pardo-Tamayo, C, et al. Effects of strength training on physical fitness of Olympic combat sports athletes: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:3516. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043516,

20. Ojeda-Aravena, A, Herrera-Valenzuela, T, Valdés-Badilla, P, Báez-San Martín, E, Thapa, RK, and Ramirez-Campillo, R. A systematic review with meta-analysis on the effects of plyometric-jump training on the physical fitness of combat sport athletes. Sports. (2023) 11:33. doi: 10.3390/sports11020033,

21. Vicente-Salar, N, Fuster-Muñoz, E, and Martínez-Rodríguez, A. Nutritional ergogenic aids in combat sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2588. doi: 10.3390/nu14132588,

22. Wyatt, PB, Reiter, CR, Satalich, JR, O’Neill, CN, Edge, C, Cyrus, JW, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation in elite athletes: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. (2024) 12:23259671231220371. doi: 10.1177/23259671231220371,

23. Luo, H, Kamalden, TFT, Zhu, X, Xiang, C, and Nasharuddin, NA. Advantages of different dietary supplements for elite combat sports athletes: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:271. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-84359-3

24. Burke, LM. Practical issues in evidence-based use of performance supplements: supplement interactions, repeated use and individual responses. Sports Med. (2017) 47:79–100. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0613-9

25. López-González, LM, Moreno-Villanueva, A, López-Samanes, Á, Pallarés, JG, Mora-Rodríguez, R, Ortega, JF, et al. Acute caffeine supplementation in combat sports: does it improve performance? A systematic review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2018) 15:60. doi: 10.1186/s12970-018-0267-2

26. Swinton, PA, Hemingway, BS, Saunders, B, Gualano, B, and Dolan, E. A statistical framework to interpret individual response to intervention: paving the way for personalized nutrition and exercise prescription. Front Nutr. (2018) 5:41. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00041,

27. Miraftabi, H, Avazpoor, Z, Berjisian, E, Sarshin, A, Rezaei, S, Domínguez, R, et al. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on cognitive function, aerobic and anaerobic performances of trained male taekwondo athletes: a pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:10202. doi: 10.3390/ijerph181910202,

28. Grgic, J, Mikulic, P, Schoenfeld, BJ, Bishop, DJ, and Pedisic, Z. The influence of caffeine supplementation on resistance exercise: a review. Sports Med. (2019) 49:17–30. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0997-y,

29. Wax, B, Kerksick, CM, Jagim, AR, Mayo, JJ, Lyons, BC, and Kreider, RB. Creatine for exercise and sports performance, with recovery considerations for healthy populations. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1915. doi: 10.3390/nu13061915,

30. Vicente-Salar, N, Drehmer, E, and Sanz-Valero, J. Nutritional ergogenic aids in combat sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2588. doi: 10.3390/nu14142588

31. Donovan, T, Ballam, T, Morton, JP, and Close, GL. Β-Alanine improves punch force and frequency in amateur boxers during a simulated contest. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2012) 22:331–7. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.22.5.331,

32. Fernández-Lázaro, D, Fiuza-Luces, C, Seco-Calvo, J, Garrosa, E, Adams, DP, González-Gallego, J, et al. β-alanine supplementation in combat sports: systematic review and meta-analysis of athletic performance outcomes. Nutrients. (2023) 15:3521. doi: 10.3390/nu15163521

33. Kim, KA, Lee, YJ, Park, KM, Kwon, YJ, and Choi, YS. The effects of 10 weeks of β-alanine supplementation on peak power, power drop, and lactate response in Korean national team boxers. J Exerc Sci Fit. (2018) 16:101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2018.07.001

34. Aravena Tapia, DE, Roman Barrera, V, Da Silva Santos, JF, Franchini, E, Valdés Badilla, P, Orihuela, P, et al. High-intensity interval training improves specific performance in taekwondo athletes. Rev Artes Marciales Asiáticas. (2020) 15:4–13. doi: 10.18002/rama.v15i1.6041

35. Arjang, N, Mohsenifar, H, Amiri, A, Dadgoo, M, and Rasaeifar, G. The acute effect of static versus proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching combined with kinesiology taping® of hamstring muscles on functional tests in adolescent taekwondo athletes. Turk J Physiother Rehabil. (2023) 34:21–8. doi: 10.21653/tjpr.974941

36. Carazo-Vargas, P, and Moncada-Jiménez, J. Reducing training volume during tapering improves performance in taekwondo athletes. J Phys Educ Sport. (2018) 18:2221–9. doi: 10.7752/jpes.2018.04334

37. Chen, AH, Chiu, CH, Hsu, CH, Wang, IL, Chou, KM, Tsai, YS, et al. Acute effects of vibration foam rolling warm-up on jump and flexibility asymmetry, agility and frequency speed of kick test performance in taekwondo athletes. Symmetry. (2021) 13:1664. doi: 10.3390/sym13091664

38. Chiu, CH, Chen, CH, Yang, TJ, Chou, KM, Chen, BW, Lin, ZY, et al. Carbohydrate mouth rinsing decreases fatigue index of taekwondo frequency speed of kick test. Chin J Physiol. (2022) 65:46–50. doi: 10.4103/cjp.cjp_99_21,

39. da Silva Santos, JF, Valenzuela, TH, and Franchini, E. Can different conditioning activities and rest intervals affect the acute performance of taekwondo turning kick? J Strength Cond Res. (2015) 29:1640–7. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000808,

40. Delleli, S, Ouergui, I, Messaoudi, H, Bridge, CA, Ardigò, LP, and Chtourou, H. Synergetic effects of a low caffeine dose and pre-exercise music on psychophysical performance in female taekwondo athletes. Rev Artes Marciales Asiát. (2024) 19:55–70. doi: 10.18002/rama.v19i1.2405

41. Delleli, S, Ouergui, I, Messaoudi, H, Bridge, C, Ardigò, LP, and Chtourou, H. Warm-up music and low-dose caffeine enhance the activity profile and psychophysiological responses during simulated combat in female taekwondo athletes. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:14302. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-64880-1,

42. Delleli, S, Ouergui, I, Messaoudi, H, Ballmann, CG, Ardigo, LP, and Chtourou, H. Effects of caffeine consumption combined with listening to music during warm-up on taekwondo physical performance, perceived exertion and psychological aspects. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0292498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0292498,

43. Gaamouri, N, Zouhal, H, Suzuki, K, Hammami, M, Ghaith, A, El Mouhab, EH, et al. Effects of carob rich-polyphenols on oxidative stress markers and physical performance in taekwondo athletes. Biol Sport. (2024) 41:277–84. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2022.106154,

44. Gaamouri, N, Zouhal, H, Hammami, M, Hackney, AC, Abderrahman, AB, Saeidi, A, et al. Effects of polyphenol (carob) supplementation on body composition and aerobic capacity in taekwondo athletes. Physiol Behav. (2019) 205:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.03.003,

45. Hassan, A, Alibrahim, M, and Hammad, B. Influence of HIIT training and breathing mask on physiological, biochemical indicators, and skill performance in taekwondo players. Int J Hum Mov Sports Sci. (2024) 12:872–87. doi: 10.13189/saj.2024.120513

46. Jung, HC, Seo, MW, Lee, S, Jung, SW, and Song, JK. Correcting vitamin D insufficiency improves some but not all aspects of physical performance during winter training in taekwondo athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2018) 28:635–43. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2017-0412,

47. Kavcı, Z, Ozan, M, Buzdağlı, Y, Savaş, A, and Uçar, H. Investigation of the effect of nitrate and L-arginine intake on aerobic, anaerobic performance, balance, agility, and recovery in elite taekwondo athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2025) 22:2445609. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2024.2445609,

48. Koc, M, Saritas, N, Coskun, B, and Akkurt, S. Effects of threshold pressure loading exercises applied to inspiratory muscles in taekwondo athletes on the concentration and utilization of lactate. J Hum Kinet. (2025) 95:55–69. doi: 10.5114/jhk/188542

49. Lopes-Silva, JP, Silva Santos, JF, Branco, BH, Abad, CC, Oliveira, LF, Loturco, I, et al. Caffeine ingestion increases estimated glycolytic metabolism during taekwondo combat simulation but does not improve performance or parasympathetic reactivation. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0142078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142078,

50. Lopes-Silva, JP, Da Silva Santos, JF, Artioli, GG, Loturco, I, Abbiss, C, and Franchini, E. Sodium bicarbonate ingestion increases glycolytic contribution and improves performance during simulated taekwondo combat. Eur J Sport Sci. (2018) 18:431–40. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2018.1424942,

51. Messaoudi, H, Ouergui, I, Delleli, S, Ballmann, CG, Ardigò, LP, and Chtourou, H. Acute effects of plyometric-based conditioning activity and warm-up music stimuli on physical performance and affective state in male taekwondo athletes. Front Sports Act Living. (2023) 5:1335794. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2023.1335794,

52. Ojeda-Aravena, A, Herrera-Valenzuela, T, Valdes-Badilla, P, Cancino-Lopez, J, Zapata-Bastias, J, and Garcia-Garcia, JM. Effects of 4 weeks of a technique-specific protocol with high-intensity intervals on general and specific physical fitness in taekwondo athletes: an inter-individual analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3643. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073643,

53. Ou, Z, Yang, L, Wu, J, Xu, M, Weng, X, and Xu, G. Metabolic characteristics of ischaemic preconditioning induced performance improvement in taekwondo athletes using LC-MS/MS-based plasma metabolomics. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:24609. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-76045-1,

54. Ouergui, I, Delleli, S, Messaoudi, H, Chtourou, H, Bouassida, A, Bouhlel, E, et al. Acute effects of different activity types and work-to-rest ratio on post-activation performance enhancement in young male and female taekwondo athletes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1764. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031764,

55. Ouergui, I, Messaoudi, H, Chtourou, H, Wagner, MO, Bouassida, A, Bouhlel, E, et al. Repeated sprint training vs. repeated high-intensity technique training in adolescent taekwondo athletes—a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4506. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124506,

56. Ouergui, I, Delleli, S, Bridge, CA, Messaoudi, H, Chtourou, H, Ballmann, CG, et al. Acute effects of caffeine supplementation on taekwondo performance: the influence of competition level and sex. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:13795. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40365-5,

57. Ouergui, I, Franchini, E, Messaoudi, H, Chtourou, H, Bouassida, A, Bouhlel, E, et al. Effects of adding small combat games to regular taekwondo training on physiological and performance outcomes in male young athletes. Front Physiol. (2021) 12:646666. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.646666,

58. Ouergui, I, Mahdi, N, Delleli, S, Messaoudi, H, Chtourou, H, Sahnoun, Z, et al. Acute effects of low dose of caffeine ingestion combined with conditioning activity on psychological and physical performances of male and female taekwondo athletes. Nutrients. (2022) 14:571. doi: 10.3390/nu14030571,

59. Riera, J, Pons, V, Martinez-Puig, D, Chetrit, C, Tur, JA, Pons, A, et al. Dietary nucleotide improves markers of immune response to strenuous exercise under a cold environment. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2013) 10:20. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-10-20,

60. Santos, VGF, Santos, VRF, Felippe, LJC, Almeida Jr, J, Bertuzzi, R, Kiss, M, et al. Caffeine reduces reaction time and improves performance in simulated-contest of taekwondo. Nutrients. (2014) 6:637–49. doi: 10.3390/nu6020637,

61. Seo, MW, Lee, JM, Jung, HC, Jung, SW, and Song, JK. Effects of various work-to-rest ratios during high-intensity interval training on athletic performance in adolescents. Int J Sports Med. (2019) 40:503–10. doi: 10.1055/a-0927-6884,

62. Song, Y, and Sheykhlouvand, M. A comparative analysis of high-intensity technique-specific intervals and short Sprint interval training in taekwondo athletes: effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and anaerobic power. J Sports Sci Med. (2024) 23:672–83. doi: 10.52082/jssm.2024.672,

63. Wang, T, and Song, J. Fufang Ejiaojiang improves taekwondo athletes' antioxidant capacity. Int J Clin Exp Med. (2020) 13:8517–25.

64. Huang, Z, Dai, J, Chen, L, Yang, L, Gong, M, Li, D, et al. Effects of progressive and velocity-based autoregulatory resistance training on lower-limb movement ability in taekwondo athletes. Sports Health. (2024) 17:545–55. doi: 10.1177/19417381241262024,

65. Shen, X. The effect of 8-week combined balance and plyometric on the dynamic balance and agility of female adolescent taekwondo athletes. Medicine. (2024) 103:e37359. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000037359,

66. Monks, L, Seo, MW, Kim, HB, Jung, HC, and Song, JK. High-intensity interval training and athletic performance in taekwondo athletes. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. (2017) 57:1252–60. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.06853-0,

67. Sekulic, D, Spasic, M, Mirkov, D, Cavar, M, and Sattler, T. Gender-specific influences of balance, speed, and power on agility performance. J Strength Cond Res. (2013) 27:802–11. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31825c2cb0,

68. Martínez de Quel, Ó, Ara, I, Izquierdo, M, and Ayán, C. Does physical fitness predict future karate success? A study in young female karatekas. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2020) 15:868–73. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0435,

69. Apollaro, G, Panascì, M, Ouergui, I, Falcó, C, Franchini, E, Ruggeri, P, et al. Influence of body composition and muscle power performance on multiple frequency speed of kick test in taekwondo athletes. Sports. (2024) 12:322. doi: 10.3390/sports12120322,

70. Torrealba, TC, Araya, JA, Benoit, N, and Deldicque, L. Effects of high-intensity interval training in hypoxia on taekwondo performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2020) 15:1125–31. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2019-0668,

71. Berton, R, Lixandrão, ME, Pinto E Silva, CM, and Tricoli, V. Effects of weightlifting exercise, traditional resistance and plyometric training on countermovement jump performance: a meta-analysis. J Sports Sci. (2018) 36:2038–44. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1434746,

72. Da Silva Santos, JF, Herrera-Valenzuela, T, Ribeiro Da Mota, G, and Franchini, E. Influence of half-squat intensity and volume on the subsequent countermovement jump and frequency speed of kick test performance in taekwondo athletes. Kinesiology. (2016) 48:95–102. doi: 10.26582/k.48.1.6

73. Casolino, E, Cortis, C, Lupo, C, Chiodo, S, Minganti, C, and Capranica, L. Physiological versus psychological evaluation in taekwondo elite athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2012) 7:322–31. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.7.4.322,

74. Liao, YH, Sung, YC, Chou, CC, and Chen, CY. Eight-week training cessation suppresses physiological stress but rapidly impairs health metabolic profiles and aerobic capacity in elite taekwondo athletes. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0160167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0160167,

75. Tamayo Acosta, J, Sosa Gomez, AE, Samuel, S, Pelenyi, S, Acosta, RE, and Acosta, M. Effects of aerobic exercise versus high-intensity interval training on V̇O2max and blood pressure. Cureus. (2022) 14:e30322. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30322,

76. Taati, B, and Rohani, H. Substrate oxidation during exercise in taekwondo athletes: impact of aerobic fitness status. Comp Exerc Physiol. (2020) 16:371–6. doi: 10.3920/CEP200012

77. Hazell, TJ, Thomas, GWR, DeGuire, JR, and Lemon, PWR. Vertical whole-body vibration does not increase cardiovascular stress to static semi-squat exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2008) 104:903–8. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0847-y,

78. Costill, DL, Flynn, MG, Kirwan, JP, Houmard, JA, Mitchell, JB, Thomas, R, et al. Effects of repeated days of intensified training on muscle glycogen and swimming performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (1988) 20:249–54. doi: 10.1249/00005768-198806000-00006,

79. Ekblom, B, Astrand, PO, Saltin, B, Stenberg, J, and Wallström, B. Effect of training on circulatory response to exercise. J Appl Physiol. (1968) 24:518–28. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.24.4.518,

80. Zavorsky, GS. Evidence and possible mechanisms of altered maximum heart rate with endurance training and tapering. Sports Med. (2000) 29:13–26. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200029010-00002,

81. Ellison, GM, Waring, CD, Vicinanza, C, and Torella, D. Physiological cardiac remodelling in response to endurance exercise training: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Heart. (2012) 98:5–10. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300639,

82. Hoier, B, and Hellsten, Y. Exercise-induced capillary growth in human skeletal muscle and the dynamics of VEGF. Microcirculation. (2014) 21:301–14. doi: 10.1111/micc.12117,

83. Drummond, MJ, Fry, CS, Glynn, EL, Dreyer, HC, Dhanani, S, Timmerman, KL, et al. Rapamycin administration in humans blocks the contraction-induced increase in skeletal muscle protein synthesis. J Physiol. (2009) 587:1535–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163816,

84. Philp, A, Hamilton, DL, and Baar, K. Signals mediating skeletal muscle remodeling by resistance exercise: PI3-kinase independent activation of mTORC1. J Appl Physiol. (2011) 110:561–8. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00941.2010,

85. Boström, P, Wu, J, Jedrychowski, MP, Korde, A, Ye, L, Lo, JC, et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature. (2012) 481:463–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10777,

86. Pedersen, BK, Steensberg, A, Fischer, C, Keller, C, Keller, P, Plomgaard, P, et al. Searching for the exercise factor: is IL-6 a candidate? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. (2003) 24:113–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1026070911202,

87. Delleli, S, Ouergui, I, Messaoudi, H, Trabelsi, K, Ammar, A, Glenn, JM, et al. Acute effects of caffeine supplementation on physical performance, physiological responses, perceived exertion, and technical-tactical skills in combat sports: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2996. doi: 10.3390/nu14142996,

88. Mielgo-Ayuso, J, Marques-Jiménez, D, Refoyo, I, Del Coso, J, León-Guereño, P, and Calleja-González, J. Effect of caffeine supplementation on sports performance based on differences between sexes: a systematic review. Nutrients. (2019) 11:2313. doi: 10.3390/nu11102313,

89. Grgic, J. Exploring the minimum ergogenic dose of caffeine on resistance exercise performance: a meta-analytic approach. Nutrition. (2022) 97:111604. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2022.111604,

90. Merino-Fernández, M, Giráldez-Costas, V, González-García, J, Gutiérrez-Hellín, J, González-Millán, C, Matos-Duarte, M, et al. Effects of 3 mg/kg body mass of caffeine on the performance of jiu-jitsu elite athletes. Nutrients. (2022) 14:675. doi: 10.3390/nu14030675,

91. Davis, JK, and Green, JM. Caffeine and anaerobic performance: ergogenic value and mechanisms of action. Sports Med. (2009) 39:813–32. doi: 10.2165/11317770-000000000-00000,

92. Simmonds, MJ, Minahan, CL, and Sabapathy, S. Caffeine improves supramaximal cycling but not the rate of anaerobic energy release. Eur J Appl Physiol. (2010) 109:287–95. doi: 10.1007/s00421-009-1351-8,

93. Davis, JM, Zhao, Z, Stock, HS, Mehl, KA, Buggy, J, and Hand, GA. Central nervous system effects of caffeine and adenosine on fatigue. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. (2003) 284:R399–404. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00386.2002

94. Larsen, FJ, Weitzberg, E, Lundberg, JO, and Ekblom, B. Dietary nitrate reduces maximal oxygen consumption while maintaining work performance in maximal exercise. Free Radic Biol Med. (2010) 48:342–7. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.006,

95. Li, WL, Han, HF, Zhang, L, Zhang, Y, and Qu, HB. Manufacturer identification and storage time determination of “Dong'e Ejiao” using near infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. (2016) 17:382–90. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500186,

96. Główka, N, Malik, J, Podgórski, T, Stemplewski, R, Maciaszek, J, Ciążyńska, J, et al. The dose-dependent effect of caffeine supplementation on performance, reaction time and postural stability in CrossFit—a randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. (2024) 21:2301384. doi: 10.1080/15502783.2023.2301384,

97. Siegler, JC, and Hirscher, K. Sodium bicarbonate ingestion and boxing performance. J Strength Cond Res. (2010) 24:103–8. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181a392b2,

98. Garthe, I, Raastad, T, Refsnes, PE, and Sundgot-Borgen, J. Effect of nutritional intervention on body composition and performance in elite athletes. Eur J Sport Sci. (2013) 13:295–303. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2011.643923,

99. Dubnov-Raz, G, Livne, N, Raz, R, Cohen, AH, and Constantini, NW. Vitamin D supplementation and physical performance in adolescent swimmers. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. (2015) 25:317–25. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0180,

100. Jastrzębska, M, Kaczmarczyk, M, and Jastrzębski, Z. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on training adaptation in well-trained soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. (2016) 30:2648–55. doi: 10.1519/JSC.00000000000001337

101. Kim, JA, Formoso, G, Li, Y, Potenza, MA, Marasciulo, FL, Montagnani, M, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate, a green tea polyphenol, mediates NO-dependent vasodilation using signaling pathways in vascular endothelium requiring reactive oxygen species and Fyn. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:13736–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609725200,

102. Kingwell, BA. Nitric oxide-mediated metabolic regulation during exercise: effects of training in health and cardiovascular disease. FASEB J. (2000) 14:1685–96. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0896rev,

103. Domínguez, R, Cuenca, E, Maté-Muñoz, JL, Maté-Muñoz, J, García-Fernández, P, Serra-Paya, N, et al. Effects of beetroot juice supplementation on cardiorespiratory endurance in athletes. A systematic review. Nutrients. (2017) 9:43. doi: 10.3390/nu9010043,

104. Moore, AN, Haun, CT, Kephart, WC, Holland, A, Mobley, C, Pascoe, D, et al. Red spinach extract increases ventilatory threshold during graded exercise testing. Sports. (2017) 5:80. doi: 10.3390/sports5040080,

105. Lesinski, M, Muehlbauer, T, Büsch, D, and Granacher, U. Acute effects of postactivation potentiation on strength and speed performance in athletes. Sportverletz Sportschaden. (2013) 27:147–55. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1335414,

106. Ahmadnezhad, L, Yalfani, A, and Gholami Borujeni, B. Inspiratory muscle training in rehabilitation of low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. J Sport Rehabil. (2020) 29:1151–8. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2019-0231,

107. Jones, AM, Grassi, B, Christensen, PM, Krustrup, P, Bangsbo, J, and Poole, DC. Slow component of VO2 kinetics: mechanistic bases and practical applications. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2011) 43:2046–62. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31821fcfc1,

108. Llanos-Lagos, C, Ramirez-Campillo, R, Moran, J, and Sáez de Villarreal, E. The effect of strength training methods on middle-distance and long-distance runners' athletic performance: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2024) 54:1801–33. doi: 10.1007/s40279-024-02018-z,

109. Thurlow, F, Huynh, M, Townshend, A, McLaren, SJ, James, LP, Taylor, JM, et al. The effects of repeated-sprint training on physical fitness and physiological adaptation in athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. (2024) 54:953–74. doi: 10.1007/s40279-023-01959-1,

110. Glaister, M, and Gissane, C. Caffeine and physiological responses to submaximal exercise: a meta-analysis. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. (2018) 13:402–11. doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2017-0312,

Keywords: taekwondo, training, supplementation, agility, repeated-kick, VO2max, meta-analysis

Citation: Xu C, Zhang W and Luo L (2025) The effects of exercise training and nutritional supplementation on taekwondo performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 12:1618612. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1618612

Edited by:

Nora L. Nock, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Kshitij Karki, G.T.A. Foundation, NepalZhengfa Han, Guangdong University of Education, China

Copyright © 2025 Xu, Zhang and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lin Luo, NDYwMDIyODMxQGd6bnUuZWR1LmNu

Chen Xu

Chen Xu Wenxin Zhang1

Wenxin Zhang1 Lin Luo

Lin Luo