Abstract

Background:

Long-term or high-dose glucocorticoid administration can markedly impair immune responses, mask clinical indicators of pulmonary infections, and increase the susceptibility to refractory pneumonia, leading to heightened mortality risk. The Prognostic nutritional index (PNI), derived from peripheral lymphocyte count and serum albumin (ALB) levels, serves as a reliable indicator for evaluating nutritional and immune statuses across various clinical populations, including oncology patients, individuals with cardiovascular disorders, and perioperative patients. However, the predictive value of PNI in pneumonia patients receiving glucocorticoids, especially within the Chinese population, has not been sufficiently investigated. This observational analysis aimed to explore the correlation between PNI levels and all-cause mortality (ACM) in patients undergoing prolonged glucocorticoid therapy for pneumonia.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted utilizing data extracted from the Dryad database. Kaplan–Meier curves, multivariable Cox regression, restricted cubic splines (RCS), and subgroup analyses were used to assess the association between PNI and ACM in patients with pneumonia who received glucocorticoids.

Results:

The study incorporated a total of 639 pneumonia patients who received glucocorticoid therapy. The ACM rates were 22.5% at 30 days and rose to 26.0% at 90 days. Multivariable Cox regression showed that, after full adjustment for potential confounders, every 2-unit decrease in PNI was associated with a 10% higher 30-day mortality hazard (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.15, p < 0.001) and a 9% higher 90-day mortality hazard (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.04–1.14, p < 0.001). Compared with patients with PNI ≥ 43, patients with PNI < 43 had a 118% increased risk of 30-day mortality (HR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.28–3.81, p = 0.005) and a 96% increased risk of 90-day mortality (HR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.20–3.19, p = 0.008). Further validation using RCS analysis revealed a robust inverse relationship between PNI scores and ACM, and subgroup analyses revealed no significant interactions.

Conclusion:

Among pneumonia patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy, a decreased PNI was associated with an increased risk of 30-day and 90-day mortality, particularly in those with a PNI < 43.

1 Background

Pneumonia, a prevalent respiratory disorder, is characterized by inflammation of the terminal airways, alveoli, and interstitium, posing a significant challenge to global health and healthcare systems. Data from 2019 revealed that lower respiratory infections, pneumonia included, ranked as the fourth most frequent cause of global mortality (1), resulting in approximately 2.18 million deaths each year (2). Mortality among pneumonia patients is often heightened by concurrent chronic conditions such as atrial fibrillation, and heart failure (3). The coexistence of these chronic illnesses complicates therapeutic strategies and escalates the mortality risk (4). Additionally, immune suppression resulting from extended or high-dose corticosteroid therapy markedly increases susceptibility to infections, further contributing to elevated pneumonia-related mortality (5, 6). Considering the widespread clinical employment of corticosteroids, it is essential to carefully balance their therapeutic efficacy against possible harmful consequences. Therefore, the timely identification of high-risk patients for poor clinical outcomes is crucial.

Mounting evidence has demonstrated that diminished immune responses and inadequate nutritional status significantly increase susceptibility to infectious agents. Thus, timely and accurate evaluation of nutritional and immunological status is essential for prognostic prediction (7, 8). In China, nutritional interventions are increasingly prioritized by healthcare providers, prompting nursing associations across various administrative levels to develop specialized nutritional training for nurses. Currently, the Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 is the only validated assessment method with demonstrated high accuracy and sensitivity (9, 10). However, the method’s practicality is limited in patients with altered consciousness or large pleural effusions, and the results may be influenced by evaluator subjectivity. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop a simplified, objective, and universally applicable tool to accurately assess the nutritional and immune statuses of pneumonia patients receiving glucocorticoid treatment.

The Prognostic nutritional index (PNI), derived from peripheral lymphocyte count and serum albumin (ALB) concentrations, has been clinically validated as an objective indicator for evaluating nutritional and immune conditions (11). Initially introduced by Onodera et al. (12), the PNI has been broadly adopted across numerous clinical settings, such as oncology (13), cardiovascular diseases (8), chronic kidney disease (14), and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) (15), demonstrating predictive capabilities regarding therapeutic effectiveness and surgical outcomes. However, there remains limited research specifically examining the association between PNI levels and clinical prognosis in pneumonia patients undergoing glucocorticoid therapy, particularly within Chinese patient populations. Therefore, this study utilized publicly accessible data from the Dryad database to investigate the correlation between PNI and clinical outcomes in this particular patient demographic.

2 Methods

2.1 Data source

The source data were acquired from the DATA-DRYAD repository,1 originally published by Li et al. (5). Ethical approval for the original dataset was granted by the Ethics Committee of the China-Japan Friendship Hospital (Approval No.: 2015–86). This dataset is openly accessible under the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, allowing for non-commercial usage contingent upon proper acknowledgment of the original authors and the data source. The dataset’s reliability has previously been validated by two separate independent studies (6, 16).

2.2 Study population

Initially, the patient cohort consisted of 716 individuals enrolled between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2017, from six secondary and tertiary academic hospitals across China (5). All participants had undergone oral or intravenous glucocorticoid therapy due to various clinical indications, including connective tissue disorders, chronic glomerulonephritis or nephrotic syndrome, and other clinical contexts such as malignancies, lymphoma. Pneumonia developed after a median treatment duration of 4 months (interquartile range, IQR 2, 18). Diagnosis of pneumonia strictly adhered to the guidelines (17, 18). Inclusion criteria required patients to: (1) have undergone oral or intravenous glucocorticoid therapy before hospital admission, (2) develop pneumonia either at admission or during hospitalization, and (3) be aged 16 years or older. Patients with incomplete data for peripheral blood lymphocyte counts and serum ALB concentrations were excluded (n = 77), leaving a final study population of 639 individuals. Figure 1 delineates the patient selection process and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1

Flowchart of the study cohort.

2.3 Data extraction and PNI

The following variables were extracted for analysis: (1) demographic information including smoking habits, and alcohol intake; (2) vital signs encompassing body temperature and oxygen saturation levels; (3) comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, respiratory failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma, malignancies, septic shock, and altered consciousness states; (4) laboratory parameters including blood pH, hemoglobin levels, ALB, sodium, potassium, lymphocyte count, total bilirubin, white blood cell and neutrophil counts, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), platelet counts, prothrombin time, lactic acid, international normalized ratio (INR), and procalcitonin; (5) severity assessment scores based on the CURB-65 criteria; and (6) treatment interventions such as mechanical ventilation, and the cumulative glucocorticoid dosage administered.

Covariates identified as potential confounders through both literature and clinical judgment were included age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid accumulation, vasoactive drugs, CURB-65 score (5, 11, 15). The calculation for the PNI was performed according to the following formula:

PNI = serum ALB (g/L) + 5 × lymphocyte count (109/L) (19).

The primary outcomes were mortality rates at 30 days and 90 days.

2.4 Management of missing data

Only INR and blood oxygen saturation data had relatively high proportions of missing values (31.3%, 200/639, and 37.9%, 242/639, respectively). Missing data for other variables are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Missing values were imputed by multiple imputation, generating ten datasets for pooled analysis.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics and demographic data of patients were categorized based on PNI levels. Normally distributed continuous variables were summarized as means ± standard deviations (SD), whereas variables demonstrating non-normal distributions were reported as medians with corresponding interquartile ranges (IQR). Frequencies and percentages (%) were utilized to represent categorical data. To evaluate statistical differences between groups, categorical data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact tests or chi-square tests, while continuous variables were assessed using independent-sample t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, depending on their distribution.

The relationship between PNI values and the risk of mortality in pneumonia patients was assessed using Cox regression analysis. Kaplan–Meier analysis complemented by log-rank testing was conducted to determine variations in mortality risk predictions across different PNI categories. Previously reported studies have indicated that optimal PNI thresholds vary significantly according to specific diseases, population characteristics, and disease severity levels (20–23). Given potential nutritional and immune status variations between Chinese and Western populations, a threshold of 43 was adopted based on earlier research conducted in Guangdong, China (24), dividing patients into two distinct groups (PNI < 43 and ≥43). PNI was evaluated both categorically and continuously (with hazard ratios calculated for every two-unit decrement). Model 1 was Crude model (unadjusted). Model 2 adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, respiratory failure, malignancy, and septic shock. Further covariates introduced into Model 3 included blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentration, and INR. Model 4 expanded upon Model 3 by incorporating additional adjustments for mechanical ventilation use, total glucocorticoid dosage, vasoactive drug administration, and CURB-65 scoring. Additionally, RCS analysis was utilized to assess and visualize the nonlinear relationships between PNI values and mortality risks.

To confirm the reliability and consistency of these results, subgroup analyses were executed, with interactions among subgroups evaluated through likelihood ratio tests. Additionally, sensitivity analyses were conducted, excluding subjects with incomplete covariate information.

All analyses were performed utilizing R (version 4.2.2) and the Free Statistics platform (version 2.1). p < 0.05 was established as the criterion for statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

This study enrolled 639 patients with pneumonia who received glucocorticoid treatment, median duration of use (IQR) of glucocorticoid medication was 4 (2, 18) months. Based on their PNI values, patients were divided into two categories (< 43 and ≥ 43), and their initial clinical attributes are detailed in Table 1. In this cohort, 332 patients (52.0%) were aged 60 or older, 334 (52.3%) were male, 169 (26.4%) reported a history of smoking, and 55 (8.6%) were alcohol consumers. Mortality rates recorded at 30 days and 90 days post-admission were 22.5% (144 cases) and 26.0% (166 cases), respectively. Those with reduced PNI (< 43) demonstrated elevated body temperatures, higher incidences of nephrotic syndrome, respiratory failure, COPD, or asthma, and increased reliance on vasoactive drugs and mechanical ventilation. Additionally, lower PNI scores correlated with reduced counts of platelets, white blood cells, lymphocytes, and hemoglobin compared to patients exhibiting PNI scores ≥ 43.

Table 1

| Variables | Total (n = 639) | PNI < 43 (n = 475) | PNI ≥ 43 (n = 164) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year), n (%) | 0.26 | |||

| <60 | 307 (48.0) | 222 (46.7) | 85 (51.8) | |

| ≥60 | 332 (52.0) | 253 (53.3) | 79 (48.2) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.5 | |||

| Male | 334 (52.3) | 252 (53.1) | 82 (50) | |

| Female | 305 (47.7) | 223 (46.9) | 82 (50) | |

| Smoke, n (%) | 0.898 | |||

| No | 470 (73.6) | 350 (73.7) | 120 (73.2) | |

| Yes | 169 (26.4) | 125 (26.3) | 44 (26.8) | |

| Alcoholism, n (%) | 0.494 | |||

| No | 584 (91.4) | 432 (90.9) | 152 (92.7) | |

| Yes | 55 (8.6) | 43 (9.1) | 12 (7.3) | |

| Temperature, Mean ± SD | 37.3 ± 1.0 | 37.5 ± 1.1 | 37.0 ± 0.9 | < 0.001 |

| Heartrate, Mean ± SD | 88.6 ± 24.9 | 89.5 ± 25.1 | 86.0 ± 24.4 | 0.114 |

| MBP, Mean ± SD | 90.6 ± 13.3 | 90.0 ± 13.7 | 92.2 ± 11.9 | 0.074 |

| SPo2, Mean ± SD | 94.2 ± 6.2 | 93.9 ± 6.5 | 95.0 ± 5.0 | 0.038 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0.032 | |||

| No | 473 (74.0) | 362 (76.2) | 111 (67.7) | |

| Yes | 166 (26.0) | 113 (23.8) | 53 (32.3) | |

| Nephrotic syndrome, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 562 (87.9) | 405 (85.3) | 157 (95.7) | |

| Yes | 77 (12.1) | 70 (14.7) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 314 (49.1) | 203 (42.7) | 111 (67.7) | |

| Yes | 325 (50.9) | 272 (57.3) | 53 (32.3) | |

| Tumor, n (%) | 0.255 | |||

| No | 600 (93.9) | 443 (93.3) | 157 (95.7) | |

| Yes | 39 (6.1) | 32 (6.7) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Septic shock, n (%) | 0.708 | |||

| No | 596 (93.3) | 442 (93.1) | 154 (93.9) | |

| Yes | 43 (6.7) | 33 (6.9) | 10 (6.1) | |

| Disturbance of consciousness, n (%) | 0.067 | |||

| No | 606 (94.8) | 446 (93.9) | 160 (97.6) | |

| Yes | 33 (5.2) | 29 (6.1) | 4 (2.4) | |

| CHD, n (%) | 0.688 | |||

| No | 559 (87.5) | 417 (87.8) | 142 (86.6) | |

| Yes | 80 (12.5) | 58 (12.2) | 22 (13.4) | |

| CHF, n (%) | 0.383 | |||

| No | 623 (97.5) | 461 (97.1) | 162 (98.8) | |

| Yes | 16 (2.5) | 14 (2.9) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 0.684 | |||

| No | 632 (98.9) | 469 (98.7) | 163 (99.4) | |

| Yes | 7 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | |

| COPD or Asthma, n (%) | 0.047 | |||

| No | 613 (95.9) | 460 (96.8) | 153 (93.3) | |

| Yes | 26 (4.1) | 15 (3.2) | 11 (6.7) | |

| CRF, n (%) | 0.946 | |||

| No | 593 (92.8) | 441 (92.8) | 152 (92.7) | |

| Yes | 46 (7.2) | 34 (7.2) | 12 (7.3) | |

| Platelets (×109/L) | 183.0 (130.0, 245.5) | 174.0 (119.0, 234.5) | 201.0 (158.0, 259.0) | < 0.001 |

| WBC (×109 /L) | 7.9 (5.7, 11.5) | 7.8 (5.6, 11.4) | 8.5 (6.4, 12.4) | 0.016 |

| Lymphocyte (×109/L) | 0.8 (0.5, 1.4) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.2) | < 0.001 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13.7 (12.6, 15.9) | 13.7 (12.6, 16.1) | 13.5 (12.7, 15.4) | 0.557 |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0, 1.4) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.4) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.5) | 0.49 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.8) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.6) | 0.08 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 9.7 (6.6, 13.6) | 9.7 (6.4, 13.1) | 9.7 (6.8, 14.3) | 0.39 |

| Neutrophils (×109 /L) | 6.5 (4.3, 10.1) | 6.7 (4.3, 10.1) | 6.3 (4.3, 9.9) | 0.643 |

| Serum creatinine (mmol/L) | 64.0 (51.0, 89.0) | 66.0 (50.2, 93.0) | 62.9 (52.0, 78.8) | 0.407 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.0) | < 0.001 |

| PH | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 0.174 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 112.3 ± 23.0 | 110.3 ± 21.3 | 118.2 ± 26.6 | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 32.8 ± 6.4 | 30.6 ± 4.8 | 39.1 ± 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 6.3 (4.7, 9.8) | 6.5 (4.9, 10.3) | 5.8 (4.3, 8.9) | 0.01 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 3.9 (3.6, 4.2) | 3.9 (3.6, 4.2) | 4.0 (3.7, 4.2) | 0.328 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 137.7 ± 7.7 | 136.7 ± 5.4 | 140.7 ± 11.5 | < 0.001 |

| Vasoactive drugs, n (%) | 0.003 | |||

| No | 529 (82.8) | 381 (80.2) | 148 (90.2) | |

| Yes | 110 (17.2) | 94 (19.8) | 16 (9.8) | |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 412 (64.5) | 286 (60.2) | 126 (76.8) | |

| Yes | 227 (35.5) | 189 (39.8) | 38 (23.2) | |

| Curb-65, n (%) | 0.065 | |||

| ≤ 1 | 455 (71.2) | 329 (69.3) | 126 (76.8) | |

| >1 | 184 (28.8) | 146 (30.7) | 38 (23.2) | |

| Glucocorticoid accumulation (g) | 3.6 (1.9, 8.1) | 3.8 (2.2, 8.7) | 3.6 (1.8, 7.9) | 0.31 |

| 30-day mortality, n (%) | 144 (22.5) | 127 (26.7) | 17 (10.4) | < 0.001 |

| 90-day mortality, n (%) | 166 (26.0) | 144 (30.3) | 22 (13.4) | < 0.001 |

Characteristics of the study population (N = 639).

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MBP, mean blood pressure; SPo2, blood oxygen saturation; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CHD, coronary heart disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CRF, chronic renal failure; INR, international normalized ratio; PNI, prognostic nutritional index; WBC, white blood cells.

3.2 Total mortality in different PNI groups

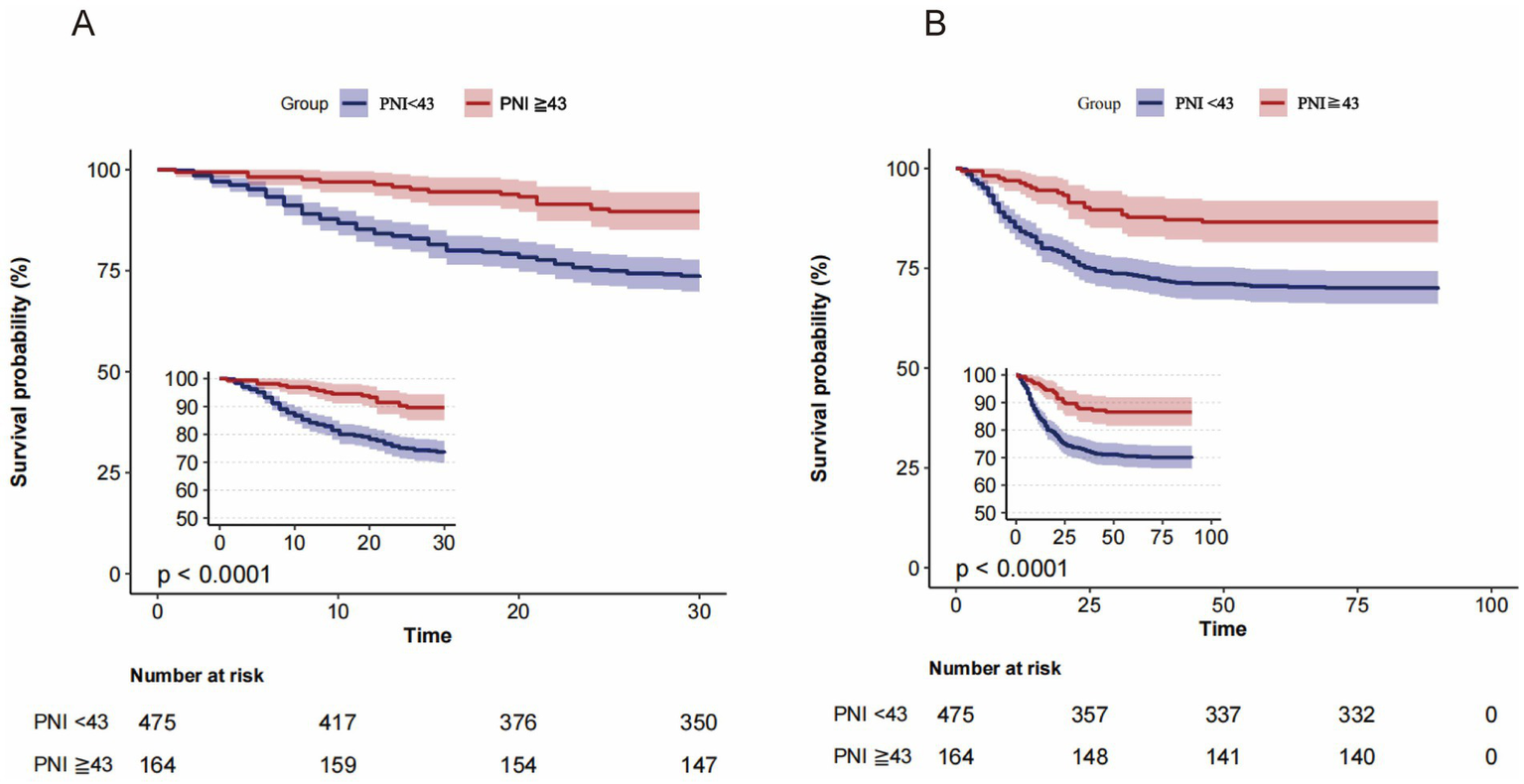

The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher among patients with PNI values below 43 (26.7%) compared to those with scores of 43 or higher (10.4%). At the 90-day mark, mortality rates were similarly higher for patients with lower PNI scores (30.3%) versus those with higher scores (13.4%). As the PNI levels decreased, mortality rates increased, a trend that was further illustrated by the Kaplan–Meier survival analyses (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality according to the PNI dichotomous numerical classification. (A) 30-day and (B) 90-day mortality: patients with PNI < 43 had significantly lower survival compared with those with PNI ≥ 43 (p < 0.0001).

3.3 Relationship between PNI and 30-day mortality

Supplementary Table S2 summarizes results from the initial univariate analysis concerning 30-day mortality among pneumonia patients. Subsequent multivariate Cox regression (Table 2) revealed a robust association between decreasing PNI and higher 30-day mortality. Specifically, an unadjusted model indicated a 17% increase in mortality risk for every two-unit drop in PNI (HR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.11–1.22, p < 0.001). This association persisted even after comprehensive covariate adjustments (HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.05–1.15, p < 0.001, Model 4). Categorically, patients whose PNI scores fell below 43 experienced a 188% higher mortality risk within 30 days in the crude model (HR = 2.88, 95% CI = 1.73–4.77, p < 0.001). After extensive adjustments, this elevated mortality risk remained significant (HR = 2.18, 95% CI = 1.28–3.81, p = 0.005, Model 4).

Table 2

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| 30-day mortality | ||||||||

| Continuousa | 1.17 (1.11–1.22) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | <0.001 | 1.11 (1.05–1.16) | <0.001 | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | <0.001 |

| PNI ≥ 43 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||||

| PNI<43 | 2.88 (1.73–4.77) | <0.001 | 1.80 (1.08–2.99) | 0.027 | 2.13 (1.24–3.67) | 0.007 | 2.18 (1.28–3.81) | 0.005 |

| 90-day mortality | ||||||||

| Continuousa | 1.15 (1.11–1.20) | <0.001 | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | 0.001 | 1.09 (1.05–1.14) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | <0.001 |

| PNI ≥ 43 | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) | ||||

| PNI<43 | 2.55 (1.63–3.99) | <0.001 | 1.59 (1.01–2.5) | 0.047 | 1.87 (1.15–3.02) | 0.012 | 1.96 (1.20–3.19) | 0.008 |

Cox proportional hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause mortality.

aX was entered as a continuous variable per 2 unit decrease.

Model 1: unadjusted.

Model 2: adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock.

Model 3: adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR.

Model 4: adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid accumulation, vasoactive drugs, CURB-65.

aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence intervals; Ref., reference; INR, international normalized ratio.

3.4 Association between PNI and 90-day mortality

The outcomes of the univariate regression for 90-day mortality in pneumonia patients are displayed in Supplementary Table S3. Multivariate Cox regression analyses (Table 2) consistently revealed significant correlations between lower PNI and heightened 90-day mortality risk. When analyzed as a continuous variable, the model 1 showed a 15% increased risk per 2-unit decrease in PNI (HR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.11–1.20, p < 0.001). This association persisted in model 2 (HR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.03–1.13, p = 0.001), model 3 (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.05–1.14, p < 0.001) and model 4 (HR = 1.09, 95% CI = 1.04–1.14, p < 0.001). When PNI was used as a 2-category classification, the 90-day risk of death for patients with PNI < 43 was 2.55-fold higher than that for patients with PNI ≥ 43 (HR = 2.55, 95% CI = 1.63–3.99, p < 0.001, Table 2, Model 1). After adjusting for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid accumulation, vasoactive medications and CURB-65, this association remained signifacant (HR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.20–3.19, p = 0.008, Table 2, model 4).

3.5 RCS analysis of PNI and ACM

Fully adjusted RCS analysis supported a linear association between PNI values and mortality outcomes at both 30 and 90 days (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.6 Subgroup analysis

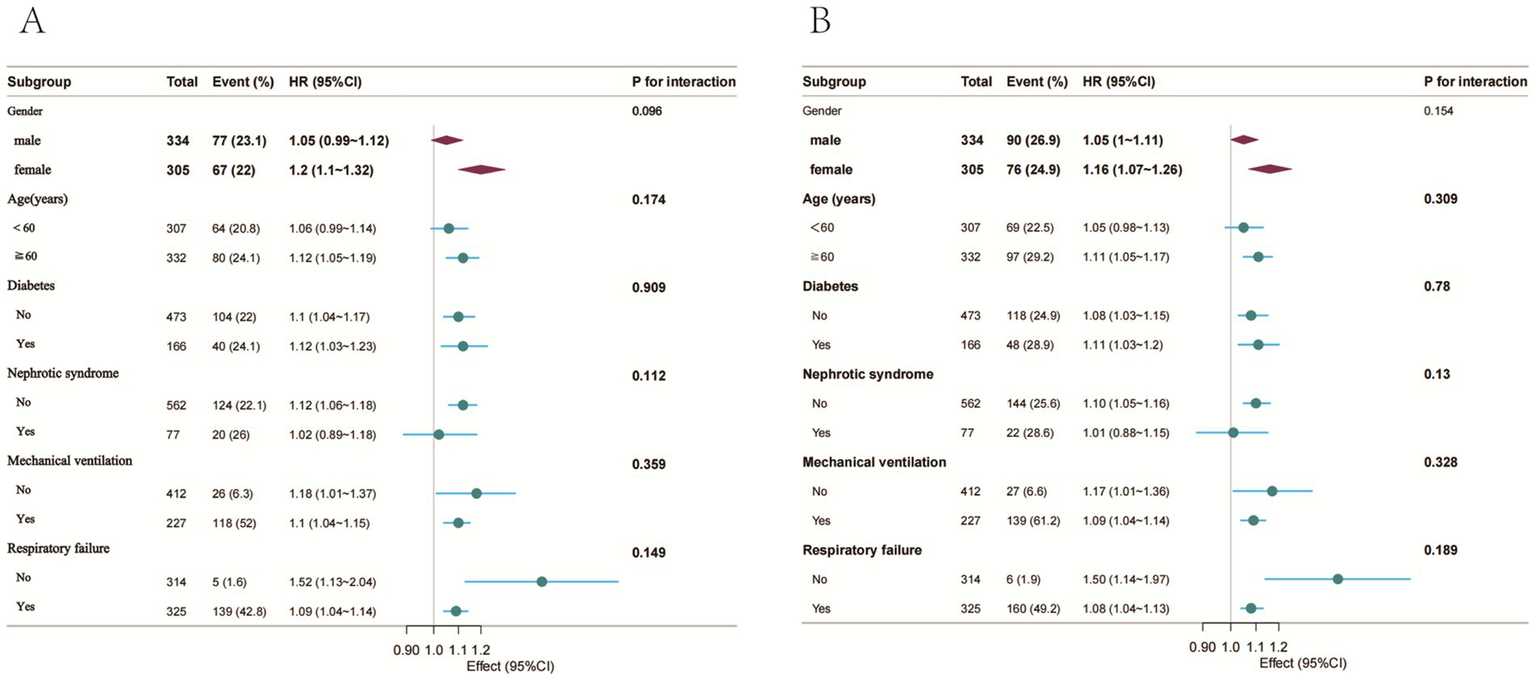

Subgroup evaluations and interaction analyses assessed the consistency of the association between PNI and mortality across various demographic and clinical subpopulations (Figure 3). Consistent inverse associations between PNI values and mortality at both 30 and 90 days were evident across all examined subgroups, with no significant subgroup interactions observed (p > 0.05).

Figure 3

Forest plot of HRs for the 30-day and 90-day mortality in different subgroups. (A) 30-day mortality; (B) 90-day mortality; Adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid accumulation, vasoactive drugs, CURB-65.

3.7 Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analyses, after omitting individuals with incomplete covariate data, the associations between PNI and mortality were stable among 358 pneumonia patients receiving glucocorticoids. Each two-unit reduction in PNI corresponded with a 10% increase in mortality risk at both 30 and 90 days in fully adjusted models. Crude analyses revealed that patients with PNI scores below 43 had a 244% higher risk of 30-day mortality (p = 0.001, Supplementary Table S4, Model 1) and a 210% higher risk of 90-day mortality (p = 0.001, Supplementary Table S5, Model 1) compared to those with PNI ≥ 43. After full adjustments, significantly elevated mortality risks remained, showing a 136% higher risk at 30 days (HR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.08–5.18, p = 0.031, Supplementary Table S4, Model 4) and a 117% higher risk at 90 days (HR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.07–4.41, p = 0.031, Supplementary Table S5, Model 4).

4 Discussion

Prolonged administration of corticosteroids at high doses can significantly suppress immune function, elevating susceptibility to severe infections. Among immunocompromised individuals, pulmonary infections attributable to corticosteroid-induced immune suppression constitute a leading cause of death (5, 25), placing substantial strain on healthcare systems. Currently, there is a scarcity of effective biomarkers for predicting these outcomes. Within our study involving 639 participants, the mortality rates recorded at 30 and 90 days were 22.5 and 26.0%, respectively. Following rigorous adjustment for potential confounders, every two-unit drop in PNI was associated with an increased risk of mortality, 10% at the 30-day checkpoint and 9% at the 90-day checkpoint. Patients with PNI levels less than 43 exhibited substantially elevated risks of mortality, with increases of 118% at 30 days and 96% at 90 days.

Prior study’s have similarly explored the correlation between PNI and clinical outcomes among pneumonia patients. For example, Lisa and colleagues reported a 13.6% increase in mortality risk per unit decrease in PNI for individuals diagnosed with community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, even after adjustments for the Charlson Comorbidity Index and patient age (26). In contrast, our findings indicated a relatively lower risk, possibly attributable to our cohort’s higher median PNI values (median [IQR]: 37.9 [32.1, 43.2]), whereas Lisa et al. reported lower mean PNI scores (survivors: 34.7 ± 4.5, non-survivors: 30.1 ± 6.5). Another previous study (15) confirmed an inverse relationship between PNI and mortality at 30 and 90 days among CAP patients, although their study predominantly involved ICU admissions. Our research specifically targeted hospitalized pneumonia patients who received glucocorticoids either alone or combined with other immunosuppressive therapies. This is a crucial differentiation since prolonged glucocorticoids therapy uniquely increases vulnerability to immunosuppression and severe infectious complications (27). Furthermore, a study utilizing data from the MIMIC-III database indicated that critically ill patients with PNI below 35.07 had increased mortality risks of 21.6 and 23.3% at 30 and 90 days, respectively, compared to those with higher PNI (28).

Furthermore, diminished PNI values have consistently been linked with higher mortality risks in COVID-19 pneumonia cohorts (29–32). Park et al. (33) highlighted the prognostic role of PNI in lung cancer patients undergoing surgery, reporting elevated postoperative complications—including delirium and pneumonia—in those with a preoperative PNI under 50. In contrast, Shimoyama et al., studying a smaller cohort (n = 33), did not detect significant variations in PNI between pneumonia survivors and non-survivors (34), a discrepancy potentially attributable to their limited sample size. Collectively, this evidence supports the potential application of PNI as a reliable biomarker for evaluating nutritional health, facilitating timely interventions, and improving patient stratification in respiratory diseases.

Derived from lymphocyte counts and serum ALB measurements, PNI effectively reflects overall nutritional health, inflammatory conditions, and immune response, thus functioning as an important prognostic tool for patient outcomes (35). These factors critically influence the onset and progression of pneumonia (36–38). Prolonged or high-dose glucocorticoid treatment adversely impacts serum ALB concentration and lymphocyte counts, thereby compromising patient outcomes.

Serum ALB, synthesized exclusively by the liver, is essential for maintaining plasma colloid osmotic pressure, transporting various metabolites, and supporting nutritional status (39). Glucocorticoids enhance protein breakdown through mechanisms involving ubiquitin-proteasome and autophagy-lysosomal pathways (40, 41). Concurrently, they hinder protein synthesis by blocking eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 and ribosomal protein S6 kinase beta-1 (41). Glucocorticoid usage also predisposes individuals to gastrointestinal complications such as gastritis and ulcers, potentially impairing nutrient absorption and subsequently causing hypoproteinemia (42, 43). The reported prevalence of malnutrition among pneumonia patients is highly variable, ranging from 39.4% in community-acquired pneumonia cases (44) to around 71.8% among COVID-19 patients (45). Such nutritional deficits strongly correlate with negative clinical outcomes, including prolonged hospitalizations, increased mortality, and frequent ICU admissions (46).

Inflammation and nutrition exhibit an interdependent relationship, where inflammation may trigger insulin resistance and catabolism, thus exacerbating malnutrition (47). Conversely, nutritional deficits can result in mitochondrial dysfunction, elevated reactive oxygen species generation, and inflammatory pathway activation (48).

Peripheral lymphocytes, encompassing T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells, constitute key immune system components. Glucocorticoids inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and diminish immune functionality, thereby reducing lymphocyte counts and impairing overall immune response efficacy (49). Reduced CD4+, CD8+, and natural killer cells correlate with increased mortality in pneumocystis pneumonia among HIV-negative individuals (50). Lower absolute lymphocyte counts are also associated with increased pneumonia risk in lung transplant recipients, especially when using triple immunosuppression (51). Studies show that even a low-normal lymphocyte count (1–2 × 109cells/L) is associated with higher mortality at 28 days and 1 year (52). Furthermore, following pathogen invasion, neutrophils eliminate the invading pathogens through phagocytosis and release substantial quantities of cytokines possessing antimicrobial activity. However, excessive neutrophil activation can initiate a pathological cascade through the release of cytotoxic mediators, such as proteases and reactive oxygen species. This process concurrently recruits other immune cells, including lymphocytes, monocytes, and natural killer cells, disrupting the body’s anti-inflammatory homeostasis. The resultant amplification of damage-associated responses compromises overall immune function, culminating in clinical deterioration in patients with pneumonia (53).

PNI reflects the patient’s immunonutritional state. For individuals with chronic underlying conditions receiving long-term glucocorticoids prior to pneumonia, an integrated multidisciplinary approach is necessary (54). Maintaining respiratory and hemodynamic stability and promptly assessing PNI to evaluate immunonutritional status are recommended (55). When PNI is <43, intensified nutritional support should begin as outlined by Zhu et al. (56): (1) Establish a dedicated nutritional intervention team comprising attending physicians or higher-level clinicians, clinical dietitians, and specialized nurses. (2) Develop a personalized dietary plan based on the patient’s dietary habits and nutritional requirements. This plan should specify food types, quantities, and implement a combined enteral and parenteral nutritional strategy. Concurrently, administer intravenous supplements including water-soluble vitamins, compound amino acid injections, and lipid emulsion injections. (3) Conduct reassessments every 3 days thereafter, adjusting the nutritional intervention protocol promptly based on the evaluation results. (4) Following discharge, provide dietary guidance via platforms such as WeChat or telephone consultations. However, the timing of PNI assessment should be individualized, weighing both clinical status and socioeconomic factors.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be considered in interpreting these findings. Firstly, given the observational study design, it was impossible to conclusively establish a causal association between PNI values and pneumonia-related mortality. Secondly, our relatively limited sample size restricted our ability to comprehensively examine the potential interactions between multiple clinical variables. Thirdly, although we extensively controlled for known confounding factors in our multivariate models, there remains a possibility of residual confounding from unrecorded variables such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, procalcitonin levels, ALB infusion, or nutritional interventions, which might affect the observed PNI-mortality relationship. It is known that systemic inflammation elevates capillary permeability and hampers lymphocyte proliferation (57), thereby decreasing PNI and establishing a direct inflammation-PNI link. Furthermore, elevated CRP and IL-6 concentrations are known independent predictors of mortality linked to cardiovascular complications and infections, potentially overstating the association between PNI and mortality risk (58). Therefore, careful interpretation of these results is necessary. Subsequent investigations should consider including additional inflammatory biomarkers, such as IL-6 and CRP, to clarify how PNI influences clinical prognosis, determine whether PNI acts as an intermediary linking inflammation to clinical outcomes, and precisely measure the magnitude of any mediation effect. Furthermore, the absence of comprehensive information regarding glucocorticoid dosing protocols and delivery routes (intravenous, oral, or mixed regimens) restricted our ability to accurately evaluate the degree of immunosuppressive effect. Nonetheless, given the relative homogeneity of our patient group and thorough adjustments for critical confounding variables, the lack of granular glucocorticoid treatment details is unlikely to materially affect the validity of our conclusions. This research lays important foundations for future work designed to further confirm the prognostic significance of PNI across broader and diverse patient groups. Future studies should independently validate these findings by leveraging alternate databases or conducting prospective cohort analyses, thereby strengthening confidence in their applicability and robustness.

5 Conclusion

In pneumonia patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy, PNI was inversely associated with 30-day and 90-day mortality rates. Clinicians should carefully monitor pneumonia patients with reduced PNI who are undergoing glucocorticoid treatment, in order to provide optimal care and improve patient prognosis.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: the datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Dryad database repository, https://datadryad.org/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.mkkwh70x2.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of China-Japan Friendship Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

FX: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. QF: Writing – original draft. KY: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. RL: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. XC: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. XQ: Writing – review & editing, Methodology. HX: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JP: Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. SG: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Professor Lijuan Li and her colleagues for providing data and sharing it in DYARD. We thank Dr. Liu Jie (People’s Liberation Army of China General Hospital, Beijing, China) and Dr. Yiren Wang (School of Nursing, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan, China) for helping in this revision.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1625531/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE S1The linear relationship between PNI and all-cause mortality. (A) Fit curves for 30-day mortality, (B) fit curves for 90-day mortality. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted for age, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, respiratory failure, tumor, septic shock, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, white blood cells, hemoglobin, INR, mechanical ventilation, glucocorticoid accumulation, vasoactive drugs, CURB-65. Only 99.5% of the data is shown.

Abbreviations

ACM, all-cause mortality; ALB, albumin; MBP, mean blood pressure; INR, international normalized ratio; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; RCS, restricted cubic spline; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NRS 2002, Nutrition Risk Screening 2002.; ICU, intensive care unit.

Footnotes

References

1.

Li Z Zhang H Ren L Lu Q Ren X Zhang C et al . Etiological and epidemiological features of acute respiratory infections in China. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:5026. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25120-6

2.

Yu X Wang H Ma S Chen W Sun L Zou Z . Estimating the global and regional burden of lower respiratory infections attributable to leading pathogens and the protective effectiveness of immunization programs. Int J Infect Dis. (2024) 149:107268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2024.107268

3.

Shen L Jhund PS Anand IS Bhatt AS Desai AS Maggioni AP et al . Incidence and outcomes of pneumonia in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2021) 77:1961–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.03.001

4.

Alon D Stein GY Korenfeld R Fuchs S . Predictors and outcomes of infection-related hospital admissions of heart failure patients. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e72476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072476

5.

Li L Hsu SH Gu X Jiang S Shang L Sun G et al . Aetiology and prognostic risk factors of mortality in patients with pneumonia receiving glucocorticoids alone or glucocorticoids and other immunosuppressants: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e37419. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037419

6.

Wang S Ye Q . The glucocorticoid dose-mortality nexus in pneumonia patients: unveiling the threshold effect. Front Pharmacol. (2024) 15:15. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2024.1445979

7.

Hu J Dong J Yang X Ye Z Hu G . Erythrocyte modified controlling nutritional status as a biomarker for predicting poor prognosis in post-surgery breast cancer patients. Sci Rep. (2025) 15:2071. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-83729-1

8.

Fan H Huang Y Zhang H Feng X Yuan Z Zhou J . Association of four nutritional scores with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.846659

9.

Kondrup J . Espen guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. (2003) 22:415–21. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00098-0

10.

Kondrup J . Nutritional risk screening (nrs 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. (2003) 22:321–36. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(02)00214-5

11.

Xu Y Yan Z Li K Liu L Xu L . Association between nutrition-related indicators with the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and all-cause mortality in the elderly population: evidence from nhanes. Front Nutr. (2024) 11:11. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1380791

12.

Onodera T Goseki N Kosaki G . Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery of malnourished cancer patients. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. (1984) 85:1001–5.

13.

Xie H Wei L Yuan G Liu M Tang S Gan J . Prognostic value of prognostic nutritional index in patients with colorectal cancer undergoing surgical treatment. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.794489

14.

Yu J Chen Y Yin M . Association between the prognostic nutritional index (pni) and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. (2023) 45:45. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2023.2264393

15.

Wang G Wang N Liu T Ji W Sun J Lv L et al . Association between prognostic nutritional index and mortality risk in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a retrospective study. BMC Pulm Med. (2024) 24:555. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-03373-3

16.

Xia B Song B Zhang J Zhu T Hu H . Prognostic value of blood urea nitrogen-to-serum albumin ratio for mortality of pneumonia in patients receiving glucocorticoids: secondary analysis based on a retrospective cohort study. J Infect Chemother. (2022) 28:767–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.02.015

17.

Society AT America IDSO . Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2005) 171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST

18.

Sousa D Justo I Domínguez A Manzur A Izquierdo C Ruiz L et al . Community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompromised older patients: incidence, causative organisms and outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2013) 19:187–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03765.x

19.

Zhang J Xiao X Wu Y Yang J Zou Y Zhao Y et al . Prognostic nutritional index as a predictor of diabetic nephropathy progression. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3634. doi: 10.3390/nu14173634

20.

Jia S Yang X Yang D Wang R Yang X Huang M et al . Low pretreatment prognostic nutritional index predicts unfavorable survival in stage iii-iva squamous cervical cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy. BMC Cancer. (2025) 25:377. doi: 10.1186/s12885-025-13752-6

21.

Huang L Chen X Zhang Y . Low prognostic nutritional index (pni) level is associated with an increased risk of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants with different gestational ages: a retrospective study. Int J Gen Med. (2024) 17:5219–31. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S486224

22.

Peng J Nie F Li Y Xu Q Xing S Gao Y . Prognostic nutritional index as a predictor of 30-day mortality among patients admitted to intensive care unit with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Med Sci Monit. (2022) 28:e934687. doi: 10.12659/MSM.934687

23.

Gao QL Shi JG Huang YD . Prognostic significance of pretreatment prognostic nutritional index (pni) in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. (2021) 73:1657–67. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1810715

24.

Wang Z Lin Y Wei X Li F Liao X Yuan H et al . Predictive value of prognostic nutritional index on covid-19 severity. Front Nutr. (2021) 7:582736. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.582736

25.

Ajmal S Mahmood M Abu Saleh O Larson J Sohail MR . Invasive fungal infections associated with prior respiratory viral infections in immunocompromised hosts. Infection. (2018) 46:555–8. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1138-0

26.

De Rose L Sorge J Blackwell B Benjamin M Mohamed A Roverts T et al . Determining if the prognostic nutritional index can predict outcomes in community acquired bacterial pneumonia. Respir Med. (2024) 226:107626. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2024.107626

27.

Agustí C Rañó A Filella X González J Moreno A Xaubet A et al . Pulmonary infiltrates in patients receiving long-term glucocorticoid treatment: etiology, prognostic factors, and associated inflammatory response. Chest. (2003) 123:488–98. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.488

28.

Lu Y Ren C Jiang J . The relationship between prognostic nutritional index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Int J Gen Med. (2021) 14:3619–26. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S318896

29.

Rashedi S Keykhaei M Pazoki M Ashraf H Najafi A Kafan S et al . Clinical significance of prognostic nutrition index in hospitalized patients with covid-19: results from single-center experience with systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Clin Pract. (2021) 36:970–83. doi: 10.1002/ncp.10750

30.

Song F Ma H Wang S Qin T Xu Q Yuan H et al . Nutritional screening based on objective indices at admission predicts in-hospital mortality in patients with covid-19. Nutr J. (2021) 20:20. doi: 10.1186/s12937-021-00702-8

31.

Wei W Wu X Jin C Mu T Gu G Min M et al . Predictive significance of the prognostic nutritional index (pni) in patients with severe covid-19. J Immunol Res. (2021) 2021:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2021/9917302

32.

Wang X Ke J Cheng R Xian H Li J Chen Y et al . Malnutrition is associated with severe outcome in elderly patients hospitalised with covid-19. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:14. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-76363-4

33.

Park S Ahn HJ Yang M Kim JA Kim JK Park SJ . The prognostic nutritional index and postoperative complications after curative lung cancer resection: a retrospective cohort study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2020) 160:276–285.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2019.10.105

34.

Shimoyama Y Umegaki O Inoue S Agui T Kadono N Minami T . The neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is superior to other inflammation-based prognostic scores in predicting the mortality of patients with pneumonia. Acta Med Okayama. (2018) 72:591–3. doi: 10.18926/AMO/56377

35.

Karimi A Shobeiri P Kulasinghe A Rezaei N . Novel systemic inflammation markers to predict covid-19 prognosis. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.741061

36.

Mizgerd JP . Pathogenesis of severe pneumonia: advances and knowledge gaps. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2017) 23:193–7. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000365

37.

Schauer AE Klassert TE von Lachner C Riebold D Schneeweiß A Stock M et al . Il-37 causes excessive inflammation and tissue damage in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J Innate Immun. (2017) 9:403–18. doi: 10.1159/000469661

38.

Zhao L Bao J Shang Y Zhang Y Yin L Yu Y et al . The prognostic value of serum albumin levels and respiratory rate for community-acquired pneumonia: a prospective, multi-center study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e248002. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248002

39.

Cameron K Nguyen AL Gibson DJ Ward MG Sparrow MP Gibson PR . Review article: albumin and its role in inflammatory bowel disease: the old, the new, and the future. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2025) 40:808–20. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16895

40.

Burt MG Johannsson G Umpleby AM Chisholm DJ Ho KK . Impact of acute and chronic low-dose glucocorticoids on protein metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2007) 92:3923–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0951

41.

Lee M Jeong HH Kim M Ryu H Baek J Lee B . Nutrients against glucocorticoid-induced muscle atrophy. Foods. (2022) 11:687. doi: 10.3390/foods11050687

42.

Gabarre P Desnos C Morin A Missri L Urbina T Bonny V et al . Albumin versus saline infusion for sepsis-related peripheral tissue hypoperfusion: a proof-of-concept prospective study. Crit Care. (2024) 28:43. doi: 10.1186/s13054-024-04827-0

43.

Hu J Lv C Hu X Liu J . Effect of hypoproteinemia on the mortality of sepsis patients in the ICU: a retrospective cohort study. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:24379. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03865-w

44.

Yeo HJ Byun KS Han J Kim JH Lee SE Yoon SH et al . Prognostic significance of malnutrition for long-term mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: a propensity score matched analysis. Korean J Intern Med. (2019) 34:841–9. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.037

45.

Jr RBL Perez BMB Masamayor EMI Chiu HHC Palileo-Villanueva LAM . The prevalence of malnutrition and analysis of related factors among adult patients with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID 19) in a tertiary government hospital: the malnutricov study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2021) 42:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.02.009

46.

Viasus D Pérez-Vergara V Carratalà J . Effect of undernutrition and obesity on clinical outcomes in adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3235. doi: 10.3390/nu14153235

47.

Wunderle C Stumpf F Schuetz P . Inflammation and response to nutrition interventions. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. (2024) 48:27–36. doi: 10.1002/jpen.2534

48.

Bañuls C de Marañon AM Veses S Castro-Vega I López-Domènech S Salom-Vendrell C et al . Malnutrition impairs mitochondrial function and leukocyte activation. Nutr J. (2019) 18:89. doi: 10.1186/s12937-019-0514-7

49.

Cain DW Cidlowski JA . Immune regulation by glucocorticoids. Nat Rev Immunol. (2017) 17:233–47. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.1

50.

Jin F Xie J Wang H . Lymphocyte subset analysis to evaluate the prognosis of HIV-negative patients with pneumocystis pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis. (2021):21. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06124-5

51.

He X Luo Z Han Y Yu J Fang S Guo L . Correlation analysis of the peripheral blood lymphocyte count and occurrence of pneumonia after lung transplantation. Transpl Immunol. (2023) 78:101822. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2023.101822

52.

Hamilton F Arnold D Payne R . Association of prior lymphopenia with mortality in pneumonia: a cohort study in Uk primary care. Br J Gen Pract. (2021) 71:e148–56. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713981

53.

Zahlten J Steinicke R Bertrams W Hocke AC Scharf S Schmeck B et al . Tlr9- and src-dependent expression of krueppel-like factor 4 controls interleukin-10 expression in pneumonia. Eur Respir J. (2013) 41:384–91. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00196311

54.

Prete A Bancos I . Glucocorticoid induced adrenal insufficiency. BMJ. (2021) 374:n1380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1380

55.

Zhou C Zhou Y Wang T Wang Y Liang X Kuang X . Association of prognostic nutritional index with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1530452. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1530452

56.

Zhu Y Fan L Geng X Li J . The predictive value of the prognostic nutritional index to postoperative prognosis and nursing intervention measures for colorectal cancer. Am J Transl Res. (2021) 13:14096–101.

57.

Eckart A Struja T Kutz A Baumgartner A Baumgartner T Zurfluh S et al . Relationship of nutritional status, inflammation, and serum albumin levels during acute illness: a prospective study. Am J Med. (2020) 133:713–722.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.10.031

58.

Tuomisto K Jousilahti P Sundvall J Pajunen P Salomaa V . C-reactive protein, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha as predictors of incident coronary and cardiovascular events and total mortality. A population-based, prospective study. Thromb Haemost. (2006) 95:511–8. doi: 10.1160/TH05-08-0571

Summary

Keywords

prognostic nutritional index, respiratory infections, glucocorticoids, prognosis, all-cause mortality

Citation

Xue F, Fang Q, Yu K, Lu R, Chen X, Qing X, Xiong H, Peng J and Guo S (2025) The impact of decreased prognostic nutritional index on the prognosis of patients with pneumonia treated with glucocorticoids: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Front. Nutr. 12:1625531. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1625531

Received

30 May 2025

Accepted

26 August 2025

Published

15 September 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Ajmer Singh Grewal, Guru Gobind Singh College of Pharmacy, India

Reviewed by

Geeta Deswal, Guru Gobind Singh College of Pharmacy, India

Guangdong Wang, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xue, Fang, Yu, Lu, Chen, Qing, Xiong, Peng and Guo.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianhua Peng, pengjianhua@swmu.edu.cnShengmin Guo, 2930773281@qq.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.