- Department of Health Sciences, College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate diet quality (DQ) using the Short Healthy Eating Index (sHEI) and explore the relationship between DQ and sociodemographic factors among young adults in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: This observational cross-sectional study was conducted in Saudi Arabia among young adults aged 18–25 years, through a questionnaire distributed online using social media. The participants provided consent and demographic information, and DQ was assessed using a validated sHEI questionnaire. The questionnaire was translated to Arabic and adapted for local relevance Data analyses were performed. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

Results: A total of 605 participants (average age 20.8 ± 2.0 years old) were recruited. More than half of the participants had a normal body mass index. The average total sHEI score, adequacy, and moderation scores were 44.98 ± 9.36, 29.56 ± 7.16, and 15.40 ± 5.71, respectively. BMI was negatively associated (weak association) with the adequacy score (p < 0.05). There were significant associations between the adequacy score, total sHEI score, sex, and region (p < 0.05). Being female was associated with good adequacy scores (p = 0.010). Being female (p = 0.001) and residing in the southern region area (p = 0.028) were associated with good total sHEI scores (p = 0.005).

Conclusion: Most individuals had a low sHEI, indicating poor DQ. Nutrition education should focus on DQ, sustainable nutrition, and eating behaviors. Future studies should assess the association between DQ and sociodemographic factors such as gender region and other lifestyle factors such as physical activity, sleep pattern, and smoking.

Introduction

Diet quality (DQ) is crucial for food security and a vital metric in nutrition, wellness, and preventive programs because of its association with chronic illnesses (1). Changing diets, increasing malnutrition concerns, and measuring DQ instead of focusing on energy sufficiency or single nutrient is gaining momentum. A high DQ is linked to a lower risk of chronic diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, serving as a protective factor. Conversely, low DQ is associated with a higher risk of obesity and chronic diseases (2).

A balanced diet is crucial for health, and meets various nutritional needs (3). DQ measures the variety and quality of food according to dietary guidelines (4). These guidelines recommend a high-quality diet rich in vegetables, fruits, seeds, legumes, and whole grains while limiting sodium, saturated fats, and sugars, indicating a low-quality diet (5). In Saudi Arabia, dietary habits include high consumption of fats, salt, and sugar, with a low intake of vegetables, fruits, dairy, nuts, and fish, raising concerns about DQ (6, 7). This unhealthy pattern is prevalent among Saudi adolescents, who often consume high-energy foods and beverages while skipping nutritious meals (8). Additionally, recent research has indicated that female university students fail to meet the recommended intake of vegetables and fruits (4).

Several tools are available to validate and measure overall DQ in the global population. The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is one of the oldest tools used to assess dietary adequacy. It evaluates the intake of nutrient adequacy; in addition, it estimates the overall balance of the diet and energy intake (9). HEI was evaluated and compared with the US Dietary Guidelines (10). HEI have undergone major developments and may be useful for intervention studies (9). Therefore, experts developed the Short Healthy Eating Index (sHEI) tool for assessing DQ, which is easy to use for both respondents and researchers. It is a 22-item tool that measures consumption in terms of nutrients and quantity; it includes (fruits, vegetables, dairy, added sugar, sugar from sugar-sweetened beverages, and calcium) (2).

Although DQ is a critical measure of overall diet and health status, to the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed DQ using the sHEI among young adults of both sexes in Saudi Arabia. Young adulthood is recognized as a critical developmental stage wherein long-term dietary habits and lifestyle behaviors are established. It is accompanied by major transitions including increased autonomy, changes in living arrangements, academic or occupational demands, and exposure to new social environments. These factors collectively contribute to a heightened risk of adopting unhealthy dietary patterns and sedentary behaviors, which may persist into later adulthood and influence long-term health outcomes. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the DQ using the sHEI and explore the relationship between the sHEI and sociodemographic factors among young female and male adults in Saudi Arabia. This study provides valuable insights into dietary habits and guides public health efforts to enhance DQ, prevent diet-related chronic diseases, and promote nutritional wellbeing.

Materials and methods

Participants and sample size

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board committee (IRB# Exempt Approval 22–0935 dated 27 Nov 2022). A detailed consent form was given to all participants that included data confidentiality and voluntary participation information. The sample size was estimated based on a population of 4–800 individuals aged 18–25 years by 2022 (11). The sample size calculation was conducted assuming a prevalence of 50% (p ≤ 0.05) due to the lack of established information regarding the prevalence of DQ. The final sample size was 384. However, 605 participants were recruited to increase the statistical power, representativeness and generalizability of the results.

This cross-sectional study included young adults aged 18–25 years, living in Saudi Arabia. The exclusion criteria included pregnant or lactating females or people with chronic diseases that alters food behaviors (such as food allergies, celiac disease, and diabetes mellitus). An online questionnaire was distributed in Arabic through social media platforms (WhatsApp, Twitter, and Telegram), using snowball sampling.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected by asking participants to provide specific demographic information including age, sex, education level, nationality, occupation, marital status, and region of residence in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, participants were asked to record their weight (kg) and height (cm) to calculate body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2). BMI was categorized into three groups: underweight, healthy or normal, and overweight or obese (12).

Diet quality

Diet Quality was assessed and validated using sHEI. The sHEI is a 22-item tool and was developed and validated in the college population by Colby et al., 2020 (2). The sHEI scoring system depends on 13 components (total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein, seafood, plant protein, fatty acids, refined grains, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats), based on the dietary guidelines (2, 13, 14). Recently, the sHEI was translated into Arabic and its reliability and validity were assessed in a young Saudi adult population (15). The total score was calculated as the sum of the 13 components. The adequacy score reflects food components that should be consumed in sufficient quantities for a healthy diet. The adequacy score was calculated as the sum of nine components (total fruits, whole fruits, total vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, dairy, total protein, seafood and plant protein, and fatty acids) (16). The moderation score reflects the food components that should be consumed in limited amounts to avoid negative health impacts. The moderation score was calculated as the sum of four components (refined grains, sodium, added sugars, and saturated fats) (16). The cutoff points for good and poor DQ scores were above and below the median, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V.26 software was used. The cut-off point for significance was p-value ≤ 0.05. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (n) and percentages (%), whereas continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). To test the association between DQ and sociodemographic characteristics, a chi-square test was conducted between two categorical variables: sociodemographic characteristics (sex, BMI, region, marital status, and education) and sHEI (poor vs. good). After performing chi square, post hoc analysis was performed to pinpoint region of significance. Spearman’s correlation was conducted between sHEI (adequacy, moderation, and total score), age, and BMI. A multinomial logistic regression was conducted between the sHEI (adequacy, moderation, and total scores) and sociodemographic characteristics.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

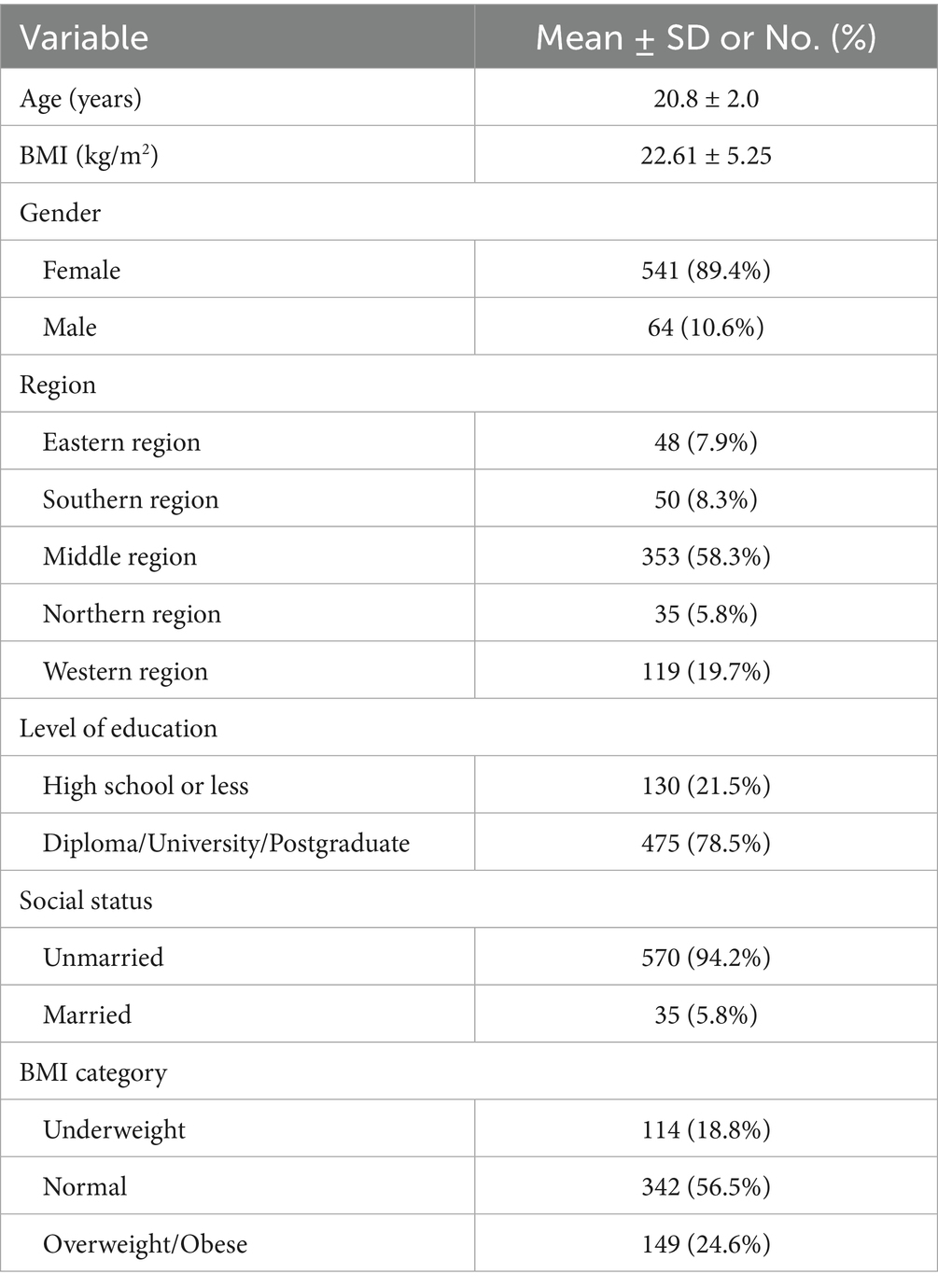

Table 1 presents the participants’ general characteristics. A total of 605 participants were included in the analysis: 89.4% were females, and 10.6% were males. The age varied between 18 to 25 years. More than half of the participants had a normal BMI (56.5%). Most of the participants lived in the middle region of Saudi Arabia (58.3%); had a diploma, university, or postgraduate level of education (78.5%); and were unmarried (94.2%).

Diet quality

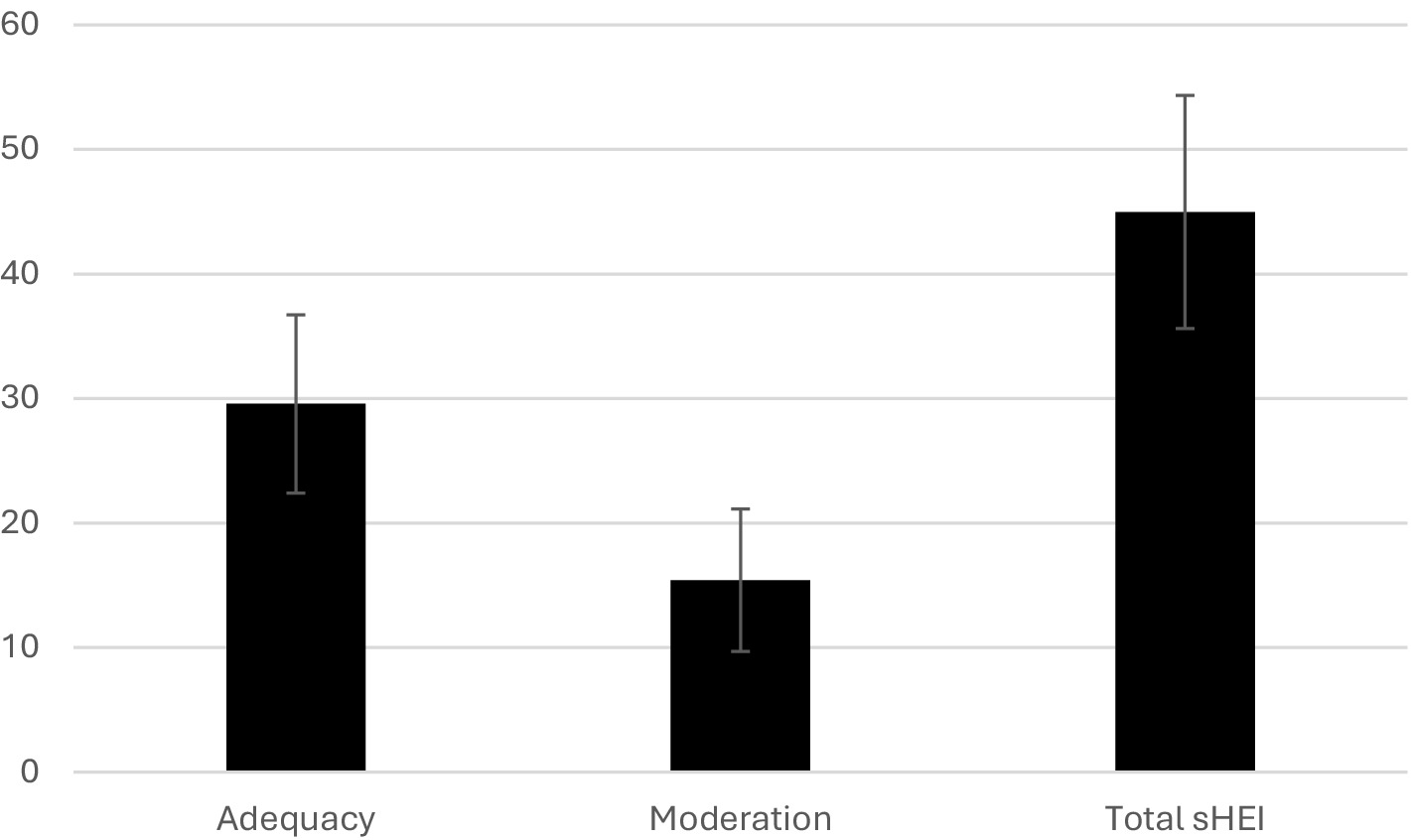

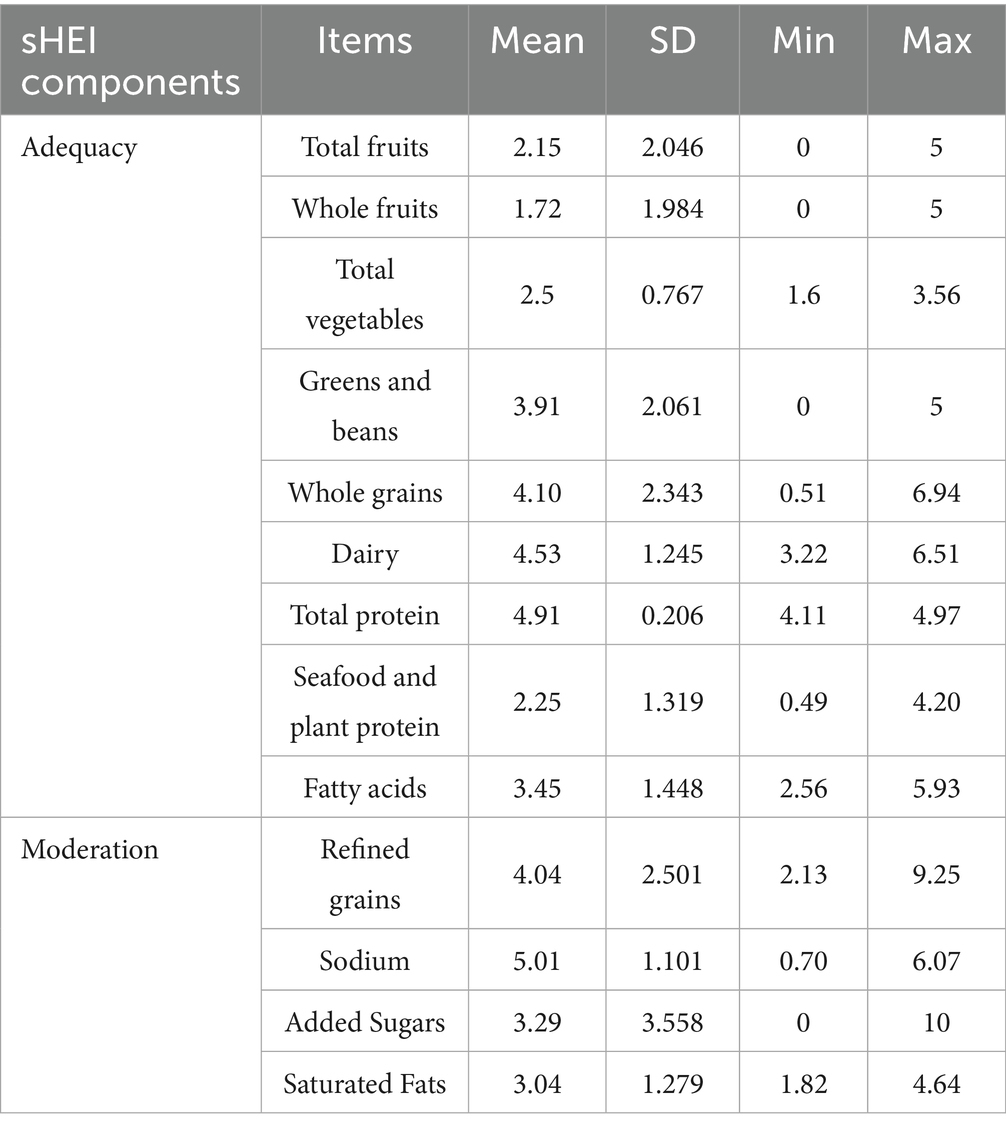

Figure 1 shows the participants’ total sHEI, adequacy, and moderation scores (n = 605). The average total sHEI score was 44.98 ± 9.36 (range 23.42–73.61). The mean adequacy score was 29.56 ± 7.16 (range 14.53–45.09). The mean moderation score was 15.40 ± 5.71 (range 4.65–28.52). Table 2 shows the sHEI component scores (n = 605). Whole fruit consumption was lowest score in the sHEI group.

Association between general characteristics and diet quality

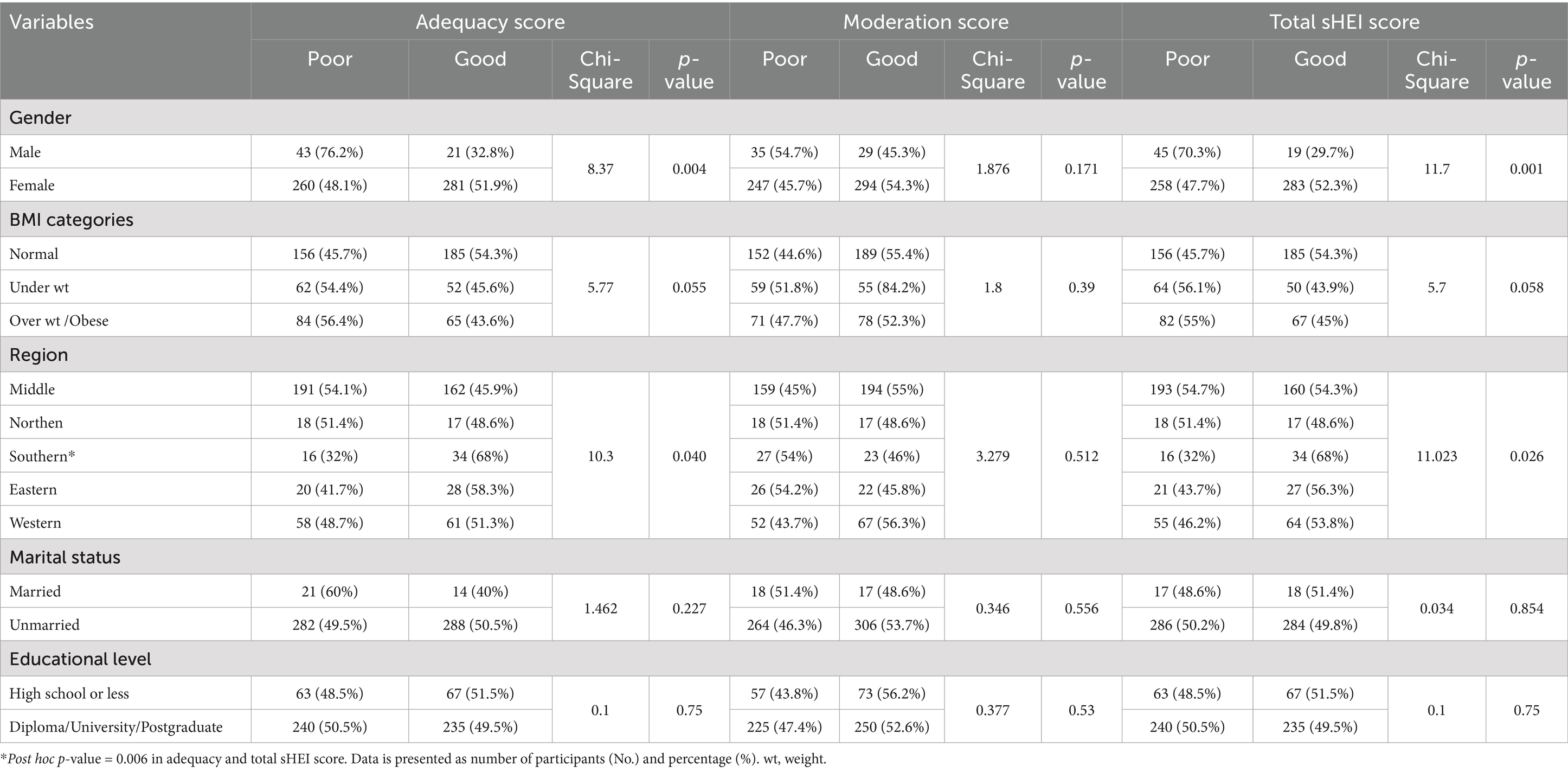

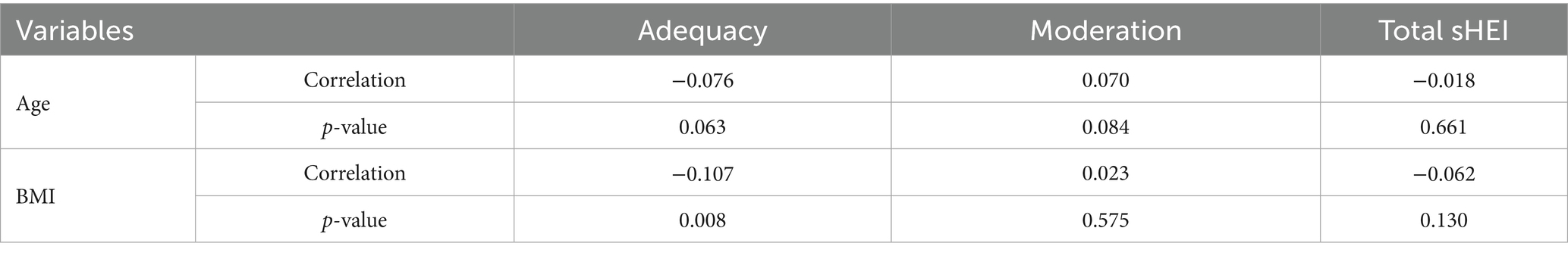

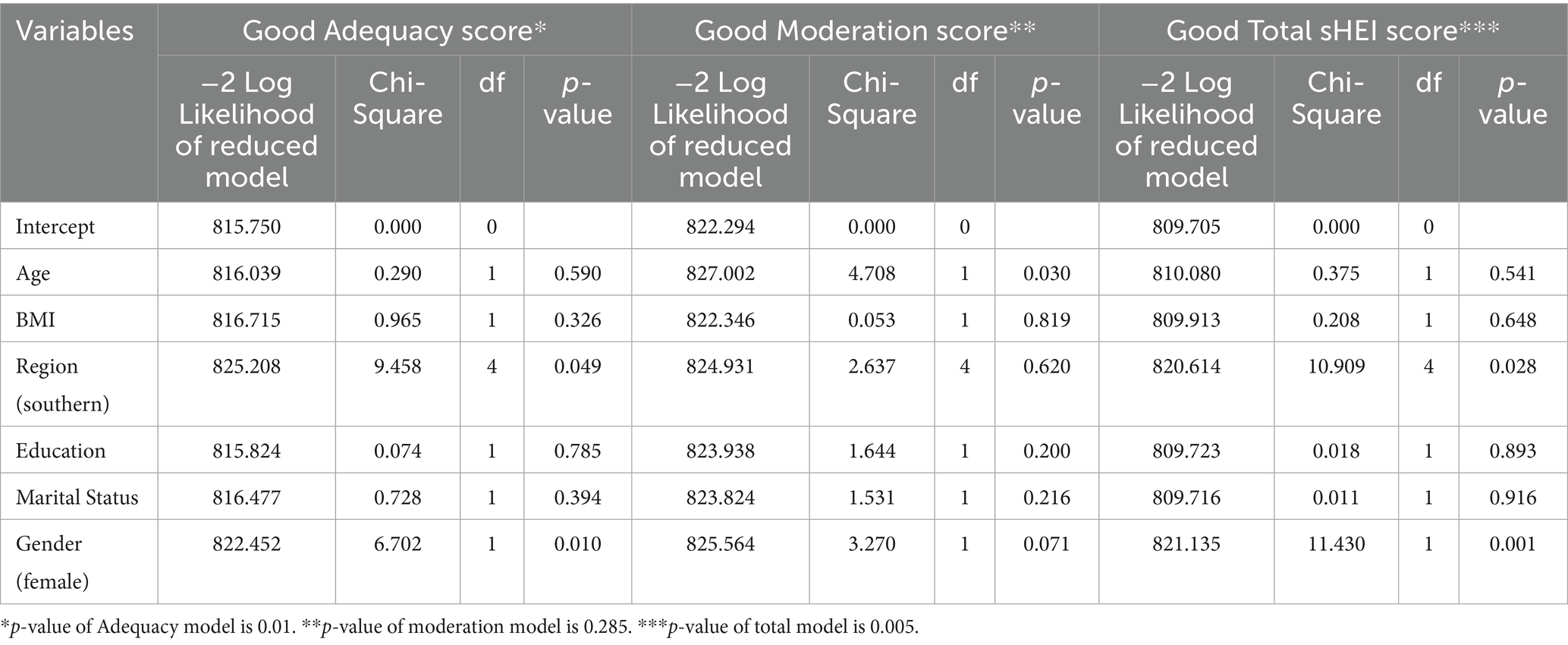

Table 3 shows the associations between adequacy, moderation, total sHEI scores, and sociodemographic characteristics. Sex and region were significantly associated with adequacy and total sHEI scores (p < 0.05). After performing chi square to compare regions regarding adequacy score and total sHEI score, post hoc analysis was performed to pinpoint region of significance. Post hoc analysis shows that southern rejoin were associated with adequacy and total sHEI score (p = 0.006). Table 4 shows the Spearman’s correlation between adequacy, moderation, total sHEI scores, age, and BMI. BMI was negatively associated (weakly associated) with the adequacy score (p < 0.05). Table 5 presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis of adequacy, moderation, total sHEI scores, and sociodemographic characteristics. Being female was associated with good adequacy scores (p = 0.010). Being female (p = 0.001) and residing in the southern rejoint area (p = 0.028) were associated with good total sHEI scores (p = 0.005).

Table 3. The association between adequacy, moderation and total sHEI score and sociodemographic characteristics of participants (n = 605).

Table 4. The Spearman correlation between adequacy, moderation and total sHEI score and age and BMI of participants (n = 605).

Table 5. The multinomial logistic regression of adequacy, moderation and total sHEI score and general characteristics of participants (n = 605).

Discussion

Several methodologies have been developed and used to assess overall DQ in different populations worldwide one of the earliest DQ instrument is the HEI, that measures adequacy, moderation, and overall DQ (2, 15). This study aimed to measure DQ using sHEI and explore the relationship between sHEI and sociodemographic factors among a sample of young adults in Saudi Arabia. The average sHEi score among the samples was 45, indicating a poor DQ. This result is consistent with a recent study conducted among Saudi colleges in which the average sHEI was 43 (17). Another study assessed global and regional DQ using the Alternative Healthy Eating Index (AHEI) and reported that the AHEI score in the Middle East/North African region ranged from 30 to 40 out of 100 (18). This is considered a poor DQ. However, the study examined national changes in AHEI scores between 1990 and 2018 (18). They concluded that DQ improved between 1990 and 2018 in the Middle East/North African region (18). In addition, the study examined DQ in children and adults, and the DQ did not differ between adults and children. If children have poor DQ early in life, they are more likely to maintain poor dietary habits as they grow older (19).

DQ is influenced by various factors including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), culture, physical activity, smoking status, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, education level, and country (20, 21). One study reported that females had better DQ than males, and children and older adults had better DQ than younger and middle-aged adults (20). Furthermore, socioeconomic status affects DQ. Lower socioeconomic status is associated with poor DQ and nutritional value, whereas higher status is associated with good DQ (22). In addition, DQ improved with education level. Higher education typically leads to better dietary knowledge than lower education (23).

Several studies have provided evidence of unhealthy dietary patterns among adults, adolescents, and children in Saudi Arabia (24–30). Studies have reported high consumption of soft drinks among adults in Saudi Arabia (24, 25). Another study showed a very high consumption of added sugar (73 g of added sugar per day), with the highest consumption in the northern region, followed by the Southern, Western, Central, and Eastern regions (26). Another study reported lower intakes of fruits, vegetables, and fish among in Saudi adults (29). Saudi adults consume approximately six servings/week of fruits and vegetables and one serving/week of each fish (29). A randomized controlled trial reported low consumption of fruits and vegetables among Saudi Adolescents consistent with another study in Saudi females, which reported that 97% of Saudi females consumed one–three fruit and vegetable servings per day (27, 28).

The current study observed significant regional differences in the adequacy and total sHEI scores. Several studies have reported regional differences in eating habits, diet quality and lifestyle factors which may be explained by differences in cultural norms, socioeconomic conditions, and accessibility (26, 31, 32). This leads to notable regional variations in the prevalence of overweight and obesity among Saudi children and adolescents, suggesting that environmental and behavioral factors vary considerably across geographic locations (31). A randomized controlled trial reported that an increase in DQ using the AHEI-2010 was associated with a reduction in body weight and fat mass in overweight adults (33). Individuals with normal body weight were expected to adhere to a healthier DQ.

Studies have indicated sex as a factor influencing DQ (17, 18, 20, 34, 35). A study reported that females presented with 6 points higher HEI than males (17). Similarly, another global study reported females had higher AHEI scores due to healthier dietary intake and dietary patterns (18). Also, 69% of males and 57% of females exceeded their saturated fat intake as per another study (36). While most females (approximately 86%) met the RDA for dietary fiber, only 67% of males met the RDA for dietary fiber (36). Likewise, females also have a higher intake of vitamins A and C (36). The current study observed that females had better DQ than males in adequacy score and total score. Although, the male sample size mandates caution.

In addition, other lifestyle factors may affect diet quality (social media use, sleep pattern, exercise, smoking, and alcohol) (30, 37). Current evidence indicates a positive association between physical activity, sufficient sleep, and diet quality (38–41). Additionally, the use of tobacco and alcohol is linked to negative dietary outcomes (42, 43). Several strengths of this study need to be reported, including the use of a previously valid and reliable tool to assess DQ. The sHEI was previously translated into Arabic and validated in young Arabs (15). The analysis also considered potential confounders. Finally, the sample size calculations indicated that the study size was appropriate.

Study limitations

Despite adding knowledge, the study has a few limitations. This study employed a snowball sampling method, which carries inherent limitations. Thus, the generalizability may be limited. Future studies are encouraged to adopt probability-based sampling techniques to ensure representativeness and external validity. Furthermore, the proportion of males was lower than females which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, the use of self-reported questionnaire and BMI metric.

Conclusion

A poor DQ was observed in a majority of the sample. To address this issue, nutrition education initiatives should specifically target behaviors such as increasing fruit and vegetable intake, reducing consumption of processed and high-sugar foods, and promoting balanced, sustainable eating patterns. These interventions should be implemented in schools, universities, workplaces, and primary healthcare settings to reach different age and social groups effectively. Given the observed gender and regional disparities in diet quality region-specific strategies and gender-responsive interventions are crucial. For instance, tailored programs for females and populations in underrepresented regions can help address specific dietary challenges. The current findings underscore the importance of increasing public health awareness about healthy eating. Nutrition education initiatives tailored to meet context sensitive needs targeting food intake behaviors through educational and work institutes should be promoted to control poor DQ. Finally, future studies should adopt probability-based sampling methods to assess the association between DQ and sociodemographic factors such as gender region and other lifestyle factors such as physical activity, sleep pattern, and smoking to ensure more representative data and improve the generalizability of findings.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Institutional Review Board committee (IRB# Exempt Approval 22-0935). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AbA: Data curation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision. KA: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. HB: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation. RO: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. HA: Methodology, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. ArA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. NB: Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R207), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who took part in the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hernandez-Ruiz, A, Diaz-Jereda, LA, Madrigal, C, Soto-Mendez, MJ, Kuijsten, A, and Gil, A. Methodological aspects of diet quality indicators in childhood: a mapping review. Adv Nutr. (2021) 12:2435–94. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab053

2. Colby, S, Zhou, W, Allison, C, Mathews, AE, Olfert, MD, Morrell, JS, et al. Development and validation of the short healthy eating index survey with a college population to assess dietary quality and intake. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2611. doi: 10.3390/nu12092611

3. Alfawaz, H, Khan, N, Almarshad, A, Wani, K, Aljumah, MA, Khattak, MNK, et al. The prevalence and awareness concerning dietary supplement use among Saudi adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:3515. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103515

4. Jalloun, RA, and Maneerattanasuporn, T. Comparison of diet quality among female students in different majors at Taibah University. Nutr Health. (2021) 27:133–40. doi: 10.1177/0260106020967846

5. Petersen, KS, and Kris-Etherton, PM. Diet quality assessment and the relationship between diet quality and cardiovascular disease risk. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4305. doi: 10.3390/nu13124305

6. AlHusseini, N, Sajid, M, Akkielah, Y, Khalil, T, Alatout, M, Cahusac, P, et al. Vegan, vegetarian and meat-based diets in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. (2021) 13:e18073. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18073

7. Moradi-Lakeh, M, El Bcheraoui, C, Afshin, A, Daoud, F, AlMazroa, MA, Al Saeedi, M, et al. Diet in Saudi Arabia: findings from a nationally representative survey. Public Health Nutr. (2017) 20:1075–81. doi: 10.1017/S1368980016003141

8. Alasqah, I, Mahmud, I, East, L, Alqarawi, N, and Usher, K. Dietary behavior of adolescents in the Qassim region, Saudi Arabia: a comparison between cities with and without the healthy cities program. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9508. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189508

9. Brauer, P, Royall, D, and Rodrigues, A. Use of the healthy eating index in intervention studies for Cardiometabolic risk conditions: a systematic review. Adv Nutr. (2021) 12:1317–31. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmaa167

10. Carter, P, Gray, LJ, Troughton, J, Khunti, K, and Davies, MJ. Fruit and vegetable intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2010) 341:c4229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4229

11. The General Authority for Statistics (GASTAT) in Saudi Arabia. GASTAT Statistical Database- Population Statistics. (2022). Available at: https://database.stats.gov.sa/home/indicator/535

12. Khanna, D, Peltzer, C, Kahar, P, and Parmar, MS. Body mass index (BMI): a screening tool analysis. Cureus. (2022) 14:e22119. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22119

13. Shams-White, MM, Pannucci, TE, Lerman, JL, Herrick, KA, Zimmer, M, Meyers Mathieu, K, et al. Healthy eating Index-2020: review and update process to reflect the dietary guidelines for Americans,2020-2025. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2023) 123:1280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2023.05.015

14. Haines, PS, Siega-Riz, AM, and Popkin, BM. The diet quality index revised: a measurement instrument for populations. J Am Diet Assoc. (1999) 99:697–704. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00168-6

15. Alzaben, AS, and Bawazeer, NM. Translation, validity, and reliability of an Arabic version of the short healthy eating index tested in young Saudi adults: a questionnaire-based study. Front Public Health. (2025) 13:13. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1581863

16. Reedy, J, Lerman, JL, Krebs-Smith, SM, Kirkpatrick, SI, Pannucci, TE, Wilson, MM, et al. Evaluation of the healthy eating index-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2018) 118:1622–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2018.05.019

17. Shatwan, IM, and Alzharani, MA. Association between perceived stress, emotional eating, and adherence to healthy eating patterns among Saudi college students: a cross-sectional study. J Health Popul Nutr. (2024) 43:144. doi: 10.1186/s41043-024-00637-w

18. Miller, V, Webb, P, Cudhea, F, Shi, P, Zhang, J, Reedy, J, et al. Global dietary quality in 185 countries from 1990 to 2018 show wide differences by nation, age, education, and urbanicity. Nat Food. (2022) 3:694–702. doi: 10.1038/s43016-022-00594-9

19. Abdoli, M, Scotto Rosato, M, Cipriano, A, Napolano, R, Cotrufo, P, Barberis, N, et al. Affect, body, and eating habits in children: a systematic review. Nutrients. (2023) 15:3343. doi: 10.3390/nu15153343

20. Hiza, HA, Casavale, KO, Guenther, PM, and Davis, CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2013) 113:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.011

21. Sotos-Prieto, M, Bhupathiraju, SN, Mattei, J, Fung, TT, Li, Y, Pan, A, et al. Association of changes in diet quality with Total and cause-specific mortality. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:143–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613502

22. Gomez, G, Kovalskys, I, Leme, ACB, Quesada, D, Rigotti, A, Cortes Sanabria, LY, et al. Socioeconomic status impact on diet quality and body mass index in eight Latin American countries: ELANS study results. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2404. doi: 10.3390/nu13072404

23. Darmon, N, and Drewnowski, A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. (2015) 73:643–60. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

24. Alabdulkader, S, Alzaben, AS, Almoayad, F, Mortada, EM, Benajiba, N, Aboul-Enein, BH, et al. Evaluating attitudes toward soft drink consumption among adults in Saudi Arabia: five years after selective taxation implementation. Prev Med Rep. (2024) 44:102808. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2024.102808

25. Aljaadi, AM, Turki, A, Gazzaz, AZ, Al-Qahtani, FS, Althumiri, NA, and BinDhim, NF. Soft and energy drinks consumption and associated factors in Saudi adults: a national cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1286633. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1286633

26. Alhusseini, N, Ramadan, M, Aljarayhi, S, Arnous, W, Abdelaal, M, Dababo, H, et al. Added sugar intake among the saudi population. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0291136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0291136

27. Alshaikh, MK, Rawaf, S, and Quezada-Yamamoto, H. Cardiovascular risk and fruit and vegetable consumption among women in KSA; a cross-sectional study. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. (2018) 13:444–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2018.06.001

28. Shatwan, IM, Alhefani, RS, Bukhari, MF, Hanbazazah, DA, Srour, JK, Surendran, S, et al. Effects of a smartphone app on fruit and vegetable consumption among Saudi adolescents: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Pediatr Parent. (2023) 6:e43160. doi: 10.2196/43160

29. Naaman, RK. Nutrition behavior and physical activity of middle-aged and older adults in Saudi Arabia. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3994. doi: 10.3390/nu14193994

30. Mumena, WA, Alnezari, AI, Safar, HI, Alharbi, NS, Alahmadi, RB, Qadhi, RI, et al. Media use, dietary intake, and diet quality of adolescents in Saudi Arabia. Pediatr Res. (2023) 94:789–95. doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02505-5

31. El Mouzan, MI, Al Herbish, AS, Al Salloum, AA, Al Omar, AA, and Qurachi, MM. Regional variation in prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Saudi J Gastroenterol. (2012) 18:129–32. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.93818

32. Al-Hazzaa, HM, Abahussain, NA, Al-Sobayel, HI, Qahwaji, DM, and Musaiger, AO. Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and dietary habits among Saudi adolescents relative to age, gender and region. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2011) 8:140. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-140

33. Crosby, L, Rembert, E, Levin, S, Green, A, Ali, Z, Jardine, M, et al. Changes in food and nutrient intake and diet quality on a low-fat vegan diet are associated with changes in body weight, body composition, and insulin sensitivity in overweight adults: a randomized clinical trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2022) 122:1922–1939.e0. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.04.008

34. Worsley, A, Blasche, R, Ball, K, and Crawford, D. Income differences in food consumption in the 1995 Australian National Nutrition Survey. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2003) 57:1198–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601670

35. Kurotani, K, Ishikawa-Takata, K, and Takimoto, H. Diet quality of Japanese adults with respect to age, sex, and income level in the National Health and nutrition survey, Japan. Public Health Nutr. (2020) 23:821–32. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019002088

36. Ye, KX, Sun, L, Lim, SL, Li, J, Kennedy, BK, Maier, AB, et al. Adequacy of nutrient intake and malnutrition risk in older adults: findings from the diet and healthy aging cohort study. Nutrients. (2023) 15:3446. doi: 10.3390/nu15153446

37. Rounsefell, K, Gibson, S, McLean, S, Blair, M, Molenaar, A, Brennan, L, et al. Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: a mixed methods systematic review. Nutr Diet. (2020) 77:19–40. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12581

38. Almoosawi, S, Palla, L, Walshe, I, Vingeliene, S, and Ellis, JG. Long sleep duration and social jetlag are associated inversely with a healthy dietary pattern in adults: results from the UK National Diet and nutrition survey rolling Programme Y1(−)4. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1131. doi: 10.3390/nu10091131

39. Grandner, MA, Jackson, N, Gerstner, JR, and Knutson, KL. Dietary nutrients associated with short and long sleep duration. Data from a nationally representative sample. Appetite. (2013) 64:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.004

40. Beaulieu, K, Oustric, P, and Finlayson, G. The impact of physical activity on food reward: review and conceptual synthesis of evidence from observational, acute, and chronic exercise training studies. Curr Obes Rep. (2020) 9:63–80. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00372-3

41. Joo, J, Williamson, SA, Vazquez, AI, Fernandez, JR, and Bray, MS. The influence of 15-week exercise training on dietary patterns among young adults. Int J Obes. (2019) 43:1681–90. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0299-3

42. Fontan-Vela, J, Ortiz, C, Lopez-Cuadrado, T, Tellez-Plaza, M, Garcia-Esquinas, E, and Galan, I. Alcohol consumption patterns and adherence to the Mediterranean diet in the adult population of Spain. Eur J Nutr. (2024) 63:881–91. doi: 10.1007/s00394-023-03318-2

Keywords: diet quality, short-healthy eating index, sociodemographic, sHEI, Arabic

Citation: Alzaben AS, Alresheedi KR, Bakry HM, Ozayb RA, Aldawsari HA, Alnamshan AO and Bawazeer NM (2025) Assessing the association between diet quality and sociodemographic factors in young Saudi adults. Front. Nutr. 12:1641284. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1641284

Edited by:

Olutosin Ademola Otekunrin, University of Ibadan, NigeriaReviewed by:

Gizem Helvacı, Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, TürkiyeFadime Ovalı, Selçuk University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Alzaben, Alresheedi, Bakry, Ozayb, Aldawsari, Alnamshan and Bawazeer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abeer Salman Alzaben, YXNhbHphYmVuQHBudS5lZHUuc2E=

Abeer Salman Alzaben

Abeer Salman Alzaben Kholoud Rashed Alresheedi

Kholoud Rashed Alresheedi Huny M. Bakry

Huny M. Bakry Rahaf Abdullah Ozayb

Rahaf Abdullah Ozayb Nahla M. Bawazeer

Nahla M. Bawazeer