- 1Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Intelligent Food Logistics and Processing, Institute of Food Science, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou, China

- 2State Key Laboratory for Molecular and Developmental Biology, Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Tangdu Hospital, Air Force Medical University, Xi'an, China

- 4Affiliated Hospital of Changzhi Institute of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Changzhi, China

Tremella fuciformis, commonly known as snow fungus, is a traditional edible and medicinal fungus widely used in Asian countries for centuries. Its main bioactive constituents, Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides (TFPs), have attracted considerable attention in both food and pharmaceutical industries due to their diverse biological activities. TFPs exhibit a broad spectrum of health-promoting effects, including microbial homeostasis, immuno-modulatory, antioxidant, anti-hyperglycemic, anti-hyperlipidemia, and others. This review summarizes recent advances in the extraction, purification, structural characterization, and pharmacological action of TFPs. The findings suggest that TFPs are promising natural bioactive compounds with potential applications in disease prevention and treatment, and they represent valuable candidates for the development of functional foods and therapeutic agents.

1 Introduction

Tremella fuciformis, an edible and medicinal fungus, possess notable medicinal properties and bioactivities in its fruiting bodies. It belongs to the order Tremellaces and the family Tremellaceae, exhibiting numerous clusters of flat, flaky or wavy leaflets (1). Tremella fuciformis is known as “silver fungus” or “white fungus” in China. The Tremella fuciformis was first mentioned in Shennong Bencao Jing (Shennong’s Classic of Materia Medica; 200–300AD). For thousands of years, Tremella fuciformis has been regarded as a precious traditional medicine for nourishing the stomach and lungs, and improving weakness.

Tremella fuciformis contains a variety of bioactive ingredients, including fatty acids, proteins, enzymes, polysaccharides, phenols, flavonoids, dietary fibers, and trace elements (2–4). Among which the most important polysaccharides extracted from Tremella fuciformis were considered as the main active components. Based on their origin and structural features, Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides (TFPs) are generally classified into five major categories: acidic heteropolysaccharides, neutral heteropolysaccharides, acidic oligosaccharides, cell-wall polysaccharides, and exopolysaccharides. Reported molecular weights for different TFPs span a broad range, from 1.08 × 103 Da to 3.74 × 106 Da. Notably, numerous in vitro studies have suggested that low-molecular-weight TFPs exhibit higher antioxidant activity compared to their high-molecular-weight counterparts. However, in vitro models cannot adequately replicate the complex physiological conditions within a living organism. Given the stark differences between data from in vitro assays and the biochemical environment in vivo, investigation using mammalian models is imperative. Such studies are essential to definitively elucidate the structure–activity relationships of TFPs and thereby accelerate their development as functional foods and therapeutic agents.

Significant progress has been made in understanding the chemical and biological activities of TFPs in recent decades. Numerous studies have shown that TFPS exhibits diverse physiological and health-promoting effects, including antioxidant (5–10), antitumor (11–15), immunomodulation (16–21), anti-inflammation (22–25), gastroprotective (26–28), hepatoprotective (29), neuroprotective (30–35), antidiabetic (36–39), anti-obesity (40, 41), anti-radiation (42, 43), and drug delivery (44, 45) activities. In 2002, after been approval by Chinese Food and Drug Administration (CFDA), “Tremella Fuciformis polysaccharide enteric capsules” derived from TFPs were introduced to alleviate leukopenia symptoms in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy (46–50). Additionally, these capsules are widely used as adjuvant therapies for chronic persistent hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis, mycoplasma pneumonia, and subjective cognitive disorders and other conditions (30, 51–53). Medicines derived from TFPs are primarily based on the natural active component glycosyl, offering broad applications, low toxicity, and minimal drug resistance. These characteristics provide a significant advantage over synthetic medicines. Furthermore, TFPs exhibit minimal side effects and are cost-effective, offering significant potential for future applications (54). Therefore, a comprehensive investigation into the physicochemical properties and biological activities of TFPs is crucial.

Although numerous research articles address edible fungi, literature reviews specifically focused on TFPs remain scarce. This study reviews recent advancements in the extraction and purification methods, structural characterization, and biological activities of TFPs, aiming to provide a comprehensive reference for its applications in functional ingredient, flavoring, food, and pharmaceutical industry.

2 Extraction and purification methods

Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides, a class of microbial glycans, can be extracted from the spores, mycelium, or fermentation broth of Tremella fuciformis. They are primarily composed of acidic heteropolysaccharides, neutral heteropolysaccharides, acidic oligosaccharides, cell-wall polysaccharides, and exopolysaccharides. The backbone consists mainly of mannan, with side chains linked at the 2, 4, and 6 positions by glucose, xylose, fucose, and galactose residues. TFPs typically have a molecular weight ranging from 1.3 to 1.8 million Da. Their yield, structural integrity, and biological activity are highly dependent on the extraction process (55). The extraction yield of a TFPs depends on several factors. Structural complexity-TFPs have higher molecular weights, intricate tertiary and quaternary structures, and lower solubility compared to other fungal polysaccharides. Physical properties-in aqueous solution, TFPs adopt an extended conformation and exhibit high viscosity, complicating extraction and purification. Therefore, beyond maximizing yield, preserving structural integrity is essential, making the selection of appropriate extraction methods critical for ensuring bioactivity in subsequent applications.

Common extraction methods for TFPs include hot-water extraction, alkali or acid extraction, ultrasound-assisted extraction (often with polyethylene glycol), and enzymatic hydrolysis. Combining two or more methods can increase TFPs yield by 3–4 fold (56). Among these, hot-water extraction is the most widely used approach (6, 9, 16, 31, 34, 43, 57–59), often combined with auxiliary techniques such as freeze–thaw cycles (6, 34, 35), microwave (60), or ultrasound assistance (1, 61). This method avoids the use of acid, alkali, or organic solvents, making it environmentally friendly and simplifying downstream processing. Consequently, it has become a classical and industrially preferred method for TFPs preparation. However, hot-water extraction typically requires high temperatures and prolonged durations, which can lead to polysaccharide degradation and alter their structural and functional properties. To minimize these effects, extraction is recommended at 90 °C for no more than 5 h (6, 27, 62). Vacuum concentration further helps preserve bioactivity during processing.

Crude aqueous extracts can be purified by ethanol precipitation, gradient fractionation, ion exchange chromatography, gel filtration, and affinity chromatography (63). Gel filtration separates polysaccharides based on molecular weight, with higher molecular weight fractions eluting earlier. Jin et al. used DEAE-52 anion-exchange chromatography followed by Sepharose G-100 gel filtration to isolate a fraction (TL04) with a molecular weight of 2.0 × 106 Da (31). Similarly, Ge et al. employed DEAE-Sepharose ion-exchange chromatography to separate neutral and acidic polysaccharides from fermentation broth, yielding two distinct fractions: TFPA (2.3 × 105 Da) and TFPB (1.1 × 105 Da) (7). TFPB was also isolated using a dialysis membrane with a 3.5 × 104 Da cutoff.

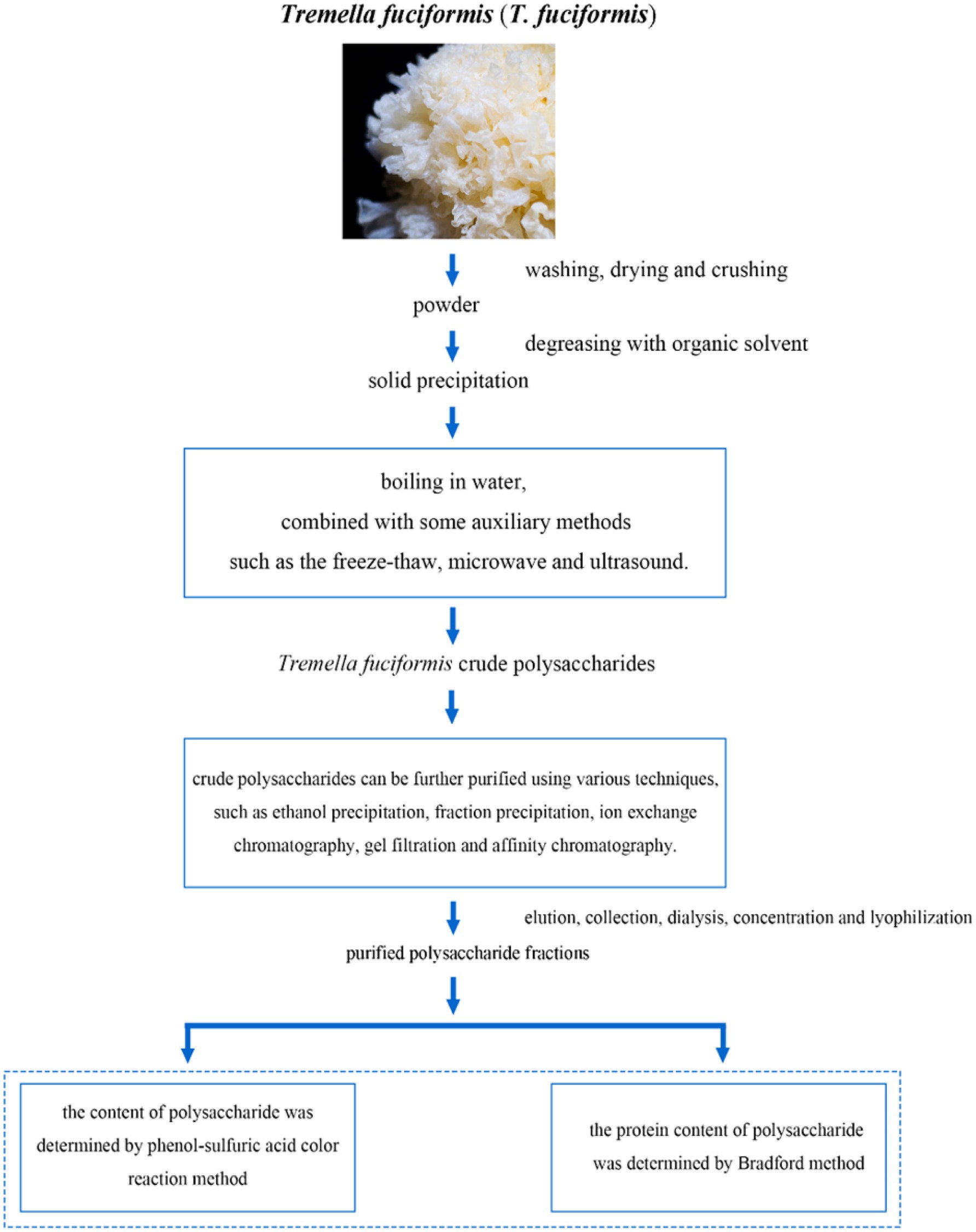

In summary, the extraction of TFPs typically begins with washing the fruiting bodies with distilled water to remove impurities, followed by drying and grinding into powder. The powdered sample is then suspended in water and heated in a water bath. After filtration and centrifugation, the supernatant is collected. To precipitate the polysaccharides, ethanol is added, and the mixture is stirred and refrigerated at 4 °C overnight. The resulting precipitate is centrifuged, dried, and ground to yield crude TFP powder. The crude extract is subsequently redissolved and purified through various chromatographic techniques, including ion exchange and gel filtration chromatography. The eluted fractions are collected, dialyzed, concentrated, and lyophilized to obtain purified polysaccharide fractions. The polysaccharide content is quantified using the phenol-sulfuric acid colorimetric method, while residual protein is determined by the Bradford assay. A schematic overview of the extraction and purification workflow is provided in Figure 1.

3 Physicochemical and structural features

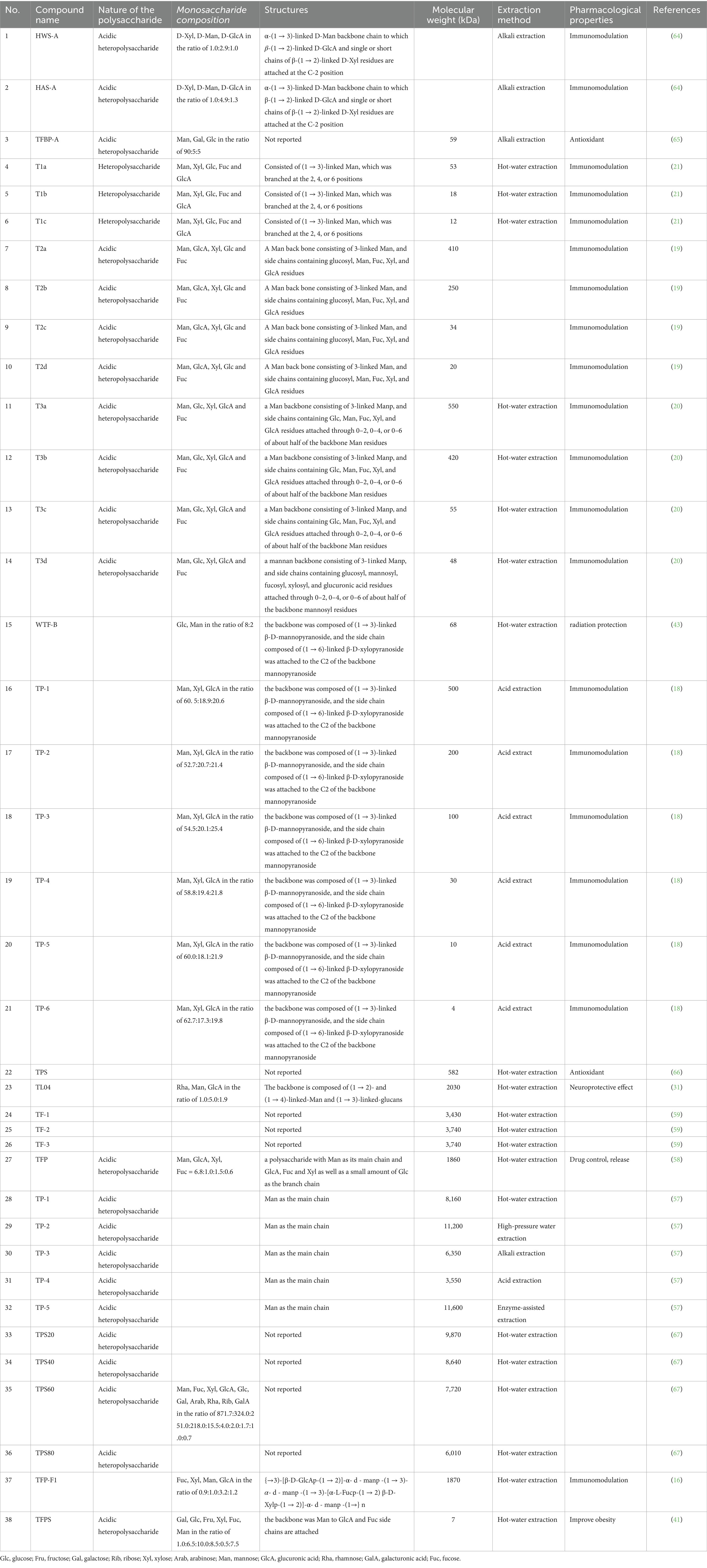

The particle size, glycosidic bonds, chain conformation, degree of branching, molecular weight and chemical composition of polysaccharides significantly affect their natural biological activity. To date, a total of 38 polysaccharides has been identified from Tremella fuciformis. Their main structural features, such as monosaccharide composition and molecular weight, are shown in Table 1, along with their names and corresponding references are included.

Kakuta et al. (64) isolated the acidic polysaccharides HWS-A and HAS-A through alkali extraction, followed by fractionation and purification, yielding approximately 70% of the total extractable material. The monosaccharide ratios of D-Xyl, D-Man, and D-GlcA were 1.0:2.9:1.0 for HWS-A and 1.0:4.9:1.3 for HAS-A. Ge et al. (65) isolated and purified the acidic heteropolysaccharide TFBP-A from Tremella fuciformis using DEAE-32 cellulose and Sephadex G-200 chromatography. The monosaccharide composition of TFBP-A was Man: Gal: Glc in a molar ratio of 90:5:5, with a molecular weight of 5.9 × 104 Da. Gao et al. (21) isolated and purified three polysaccharides (T1a, T1b, and T1c) from TFPS using hot-water extraction, ethanol precipitation, and DEAE-Sephadex A-50 chromatography. The molecular weights of T1a, T1b, and T1c were 5.3 × 104, 1.8 × 104, and 1.8 × 104 Da, respectively. Acidic hydrolysate fractions of T1a (T1a-1, 2, 3, 4, 5), with molecular weights ranging from 1.0 × 103 to 5.3 × 104 Da, were capable of inducing interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion in monocytes, similar to the parent compound T1a. Additionally, Gao et al. (19) also isolated four polysaccharides (T2a, T2b, T2c, and T2d) from Tremella fuciformis, with molecular weights of 4.1 × 105, 2.5 × 105, 3.4 × 104, and 2.0 × 104 Da, respectively. Gao et al. (20) isolated four acidic polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis by aqueous extraction (T3a, T3b, T3c, and T3d), with relative molecular masses of 5.5 × 105, 4.2 × 105, 5.5 × 104, and 4.8 × 104 Da, respectively. T3a-T3d were shown to induce the production of IL-1, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) in human monocytes in vitro. Acid hydrolysate fragments of T3a (T3a-1, T3a-2, T3a-3, T3a-4, and T3a-5A) also efficiently induced IL-6 secretion in monocytes. Further purification of Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide (WTF-B) using DEAE-Sephadex A-25 and Sephadex G-200 chromatography yielded a radioprotective, water-soluble homogeneous polysaccharide. WTF-B consisted of Glc and Man in a molar ratio of 8:2, with a molecular weight of 6.8 × 104 Da (43). Jiang et al. (18) obtained six fractions of TFPs (TP-1 to TP-6) by hydrolyzing crude TFPs. The average molecular weights of TP-1 to TP-6 were 5.0 × 105 Da, 2.0 × 105 Da, 3.0 × 104 Da, 1.0 × 105 Da, 1.0 × 104 Da, and 4.0 × 103 Da, respectively. The physicochemical properties, monosaccharide composition, and structural analysis of TP-1 through TP-6 revealed similar repeating unit structures. Liu et al. (66) isolated the primary purified polysaccharide fraction (TPS) from Tremella fuciformis seeds using DEAE-52 and Sepharose CL-4B chromatography. The molecular weight of TPS was 5.8 × 105 Da. Jin et al. (31) isolated the neuroprotective Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide TL04 (molecular weight: 2.0 × 106 Da), a heteropolysaccharide composed of Rha, Man, and Glc in a molar ratio of 1.0:5.0:1.9, using hot-water extraction, freeze-drying, and DEAE-52 cellulose anion-exchange followed by Sepharose G-100 chromatography. Wu et al. (59) used asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation to analyze high-molecular-weight branched polysaccharides, isolating three polysaccharides (TF1, TF2, and TF3) from Tremella fuciformis via hot-water extraction, with molecular weights of 3.4 × 106, 3.7 × 106, and 3.7 × 106 Da, respectively. Wang et al. (58) isolated and purified an acidic polysaccharide (TFP) from Tremella fuciformis, which was assembled into a nanostructure with chitosan for controlled release. TFP, with a molecular weight of 1.9 × 106 Da, is composed of Man, GlcA, Xyl, and Fuc in a molar ratio of 6.8:1.0:1.5:0.6. Wang et al. (57) employed various methods to extract crude polysaccharides (TPs) from Tremella fuciformis, including hot-water extraction (TP1), high-pressure water extraction (TP2), alkali extraction (TP3), acid extraction (TP4), and enzyme-assisted extraction (TP5). The molecular weights of crude polysaccharides extracted from Tremella fuciformis were 8.2 × 106, 1.1 × 107, 6.4 × 106, 3.6 × 106, and 1.2 × 107 Da, respectively. Lan et al. (67) fractionated Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides into TPS20, TPS40, TPS60, and TPS80 through stepwise ethanol precipitation. The viscosities of TPS20, TPS40, and TPS60 increased when the sucrose concentration was below 6%. Strongly acidic and strongly alkaline conditions reduced the viscosity of TPS solutions. Huang et al. (16) isolated a bioactive polysaccharide, TFP-F1, with a high molecular weight of 1.9 × 106 Da from Tremella fuciformis. Monosaccharide composition and NMR analysis revealed that the polysaccharide and its derivatives contained Fucp, Xylp, Manp, and GlcAp in a molar ratio of 0.9:1.0:3.2:1.2. Chiu et al. (41) purified and fractionated an ameliorated-obesity polysaccharide from Tremella fuciformis using anion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-650 M column. TFPS, with a molecular weight of 6.8 × 103 Da, is a heteropolysaccharide composed of Gal, Glc, Fru, Xyl, Fuc, and Man in a molar ratio of 1.0:6.5:10.0:18.5:30.5:67.5, as determined by high-performance size-exclusion chromatography (HP-SEC).

The chemical structure of TFPS is primarily composed of a linear 1,3-linked α-D-Man backbone with highly branched β-D-Xyl, α-D-Man, and β-D-GlcA side chains. The common monosaccharides include Man, Xyl, Fuc, Glc, Gal, and GlcA (59, 68). However, Ma et al. (69) suggested that TFPs may not be restricted to the previously reported skeletal structure with Man as the backbone. Additionally, Jin et al. (31) purified the Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide TL04 from its aqueous extract. The backbone of TL04 consists of (1 → 2)- and (1 → 4)-linked Man, as well as (1 → 3)-linked glucans.

Although TFPs contain potential bioactive and functional components, their chain conformation and physicochemical properties remain poorly understood. Beyond molecular weight and monosaccharide composition, limited information is available regarding the structure and conformation of TFPs. Huang et al. (16) reported that the immunomodulatory polysaccharide TFP-F1, isolated from Tremella fuciformis, has a structure of [→3)-[β-D-GlcAp-(1 → 2)]-α-D-Manp-(1 → 3)-α-D-Manp-(1 → 3)-[α-L-Fucp-(1 → 2)-β-D-Xylp-(1 → 2)]-α-D-Manp-(1→]n, with partial C6-OH acetylation on Man residues. Additionally, TFP-F1 stimulated TNF-α and IL-4 secretion in J1A.4 macrophages in vitro by interacting with Toll-like receptor 6 (TLR6) at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. Removal of the O-acetyl group abolished immunomodulatory activity, suggesting its critical role in enhancing pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

Jiang et al. (18) isolated six immunomodulatory polysaccharides (TP-1 to TP-6) from Tremella fuciformis through water decoction, hydrolysis with 0.1 mol/L hydrochloric acid, and Sephadex G-150 column chromatography. TFPs increased peripheral blood leukocyte counts reduced by cyclophosphamide, with lower molecular weight fractions exhibiting superior protective effects. Additionally, TP-1 to TP-6 were homogeneous, with monosaccharide components including Man, Xyl, and GlcA, among which Man was the most abundant. Their structures featured nonreducing β-D-glucopyranuronic terminals, a backbone of (1 → 3)-linked β-D-mannopyranoside, and a side chain of (1 → 6)-linked β-D-xylopyranoside attached to the C2 position of the backbone mannopyranoside. The structures of TP-1 to TP-6 are consistent with those of T. fuciformis polysaccharides, which implies that TFPS have repeating units can be prepared by acid hydrolysis.

The structural characteristics of polysaccharides isolated from Tremella fuciformis were investigated using ethanol precipitation and ion exchange chromatography, followed by HPGPC, HPLC, GC–MS, methylation (MT) analysis, infrared (IR), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (7). The NMR signals were predominantly observed between 20 and 180 ppm. The primary components included Man, GlcA, Glc, Gal, Xyl, and Rha. δ 80.6, 79.8, and 79.3 likely correspond to C4 of → 4)-Xylp-(1→, → 4)-Galp-(1→, and → 4)-Man-(1→, respectively, while δ 76.8 may correspond to → 4)-Glcp-(1→. Furthermore, δ 68.3 and 67.2 shifted to the low field, suggesting C6 substitution. This indicates the possible presence of C6-substituted glycosidic bonds in → 6)-Galp-(1→, → 4,6)-Manp-(1→, → 3,6)-Galp-(1→, and → 3,4,6)-Manp-(1→. The primary linkage types were identified as 1,4-Xylp, 1,4-Manp, 1-Xylp, 1-Manp, 1,4-Glcp, and 1,3,4-Galp.

4 Pharmacological action of TFPs

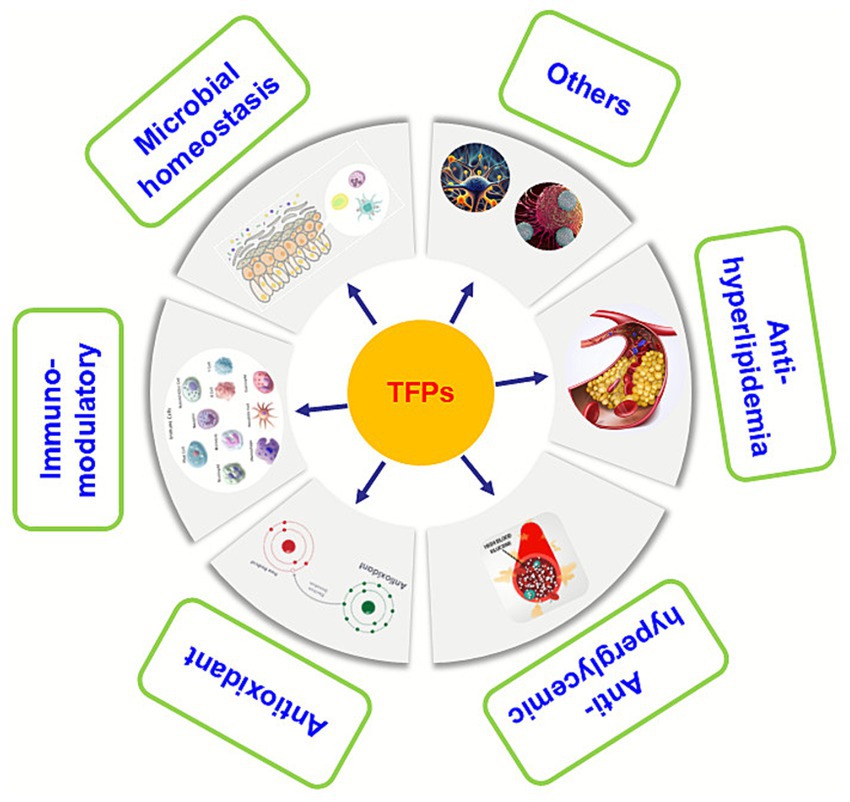

Recently, numerous in vitro and in vivo studies have been conducted to explore the various biological activity and mechanism of action of TFPs, including microbial homeostasis, immuno-modulatory, antioxidant, anti-hyperglycemic, anti-hyperlipidemia, and others (Figure 2). These biological activities and health benefits of TFPs will be discussed one by one in the following paragraphs.

4.1 Regulation effect of TFPs on microbial homeostasis

Due to the lack of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in the human body, most polysaccharides cannot be directly absorbed. The gastrointestinal tract serves as one of the primary sites for the functional expression of natural polysaccharides. Gut microbiota plays a crucial role by enhancing CAZyme activity, thereby degrading polysaccharides into monosaccharides or oligosaccharides and promoting the growth of probiotics.

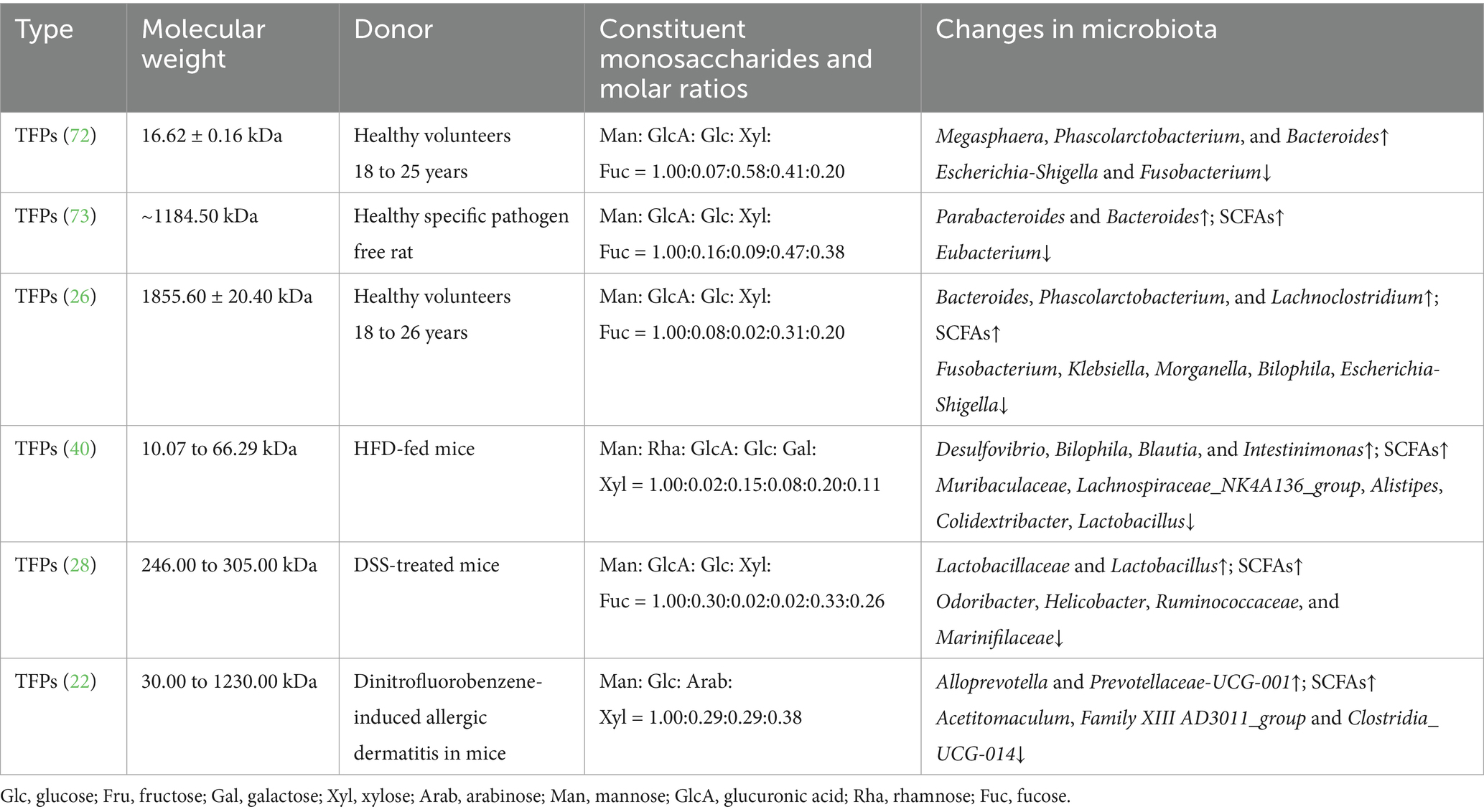

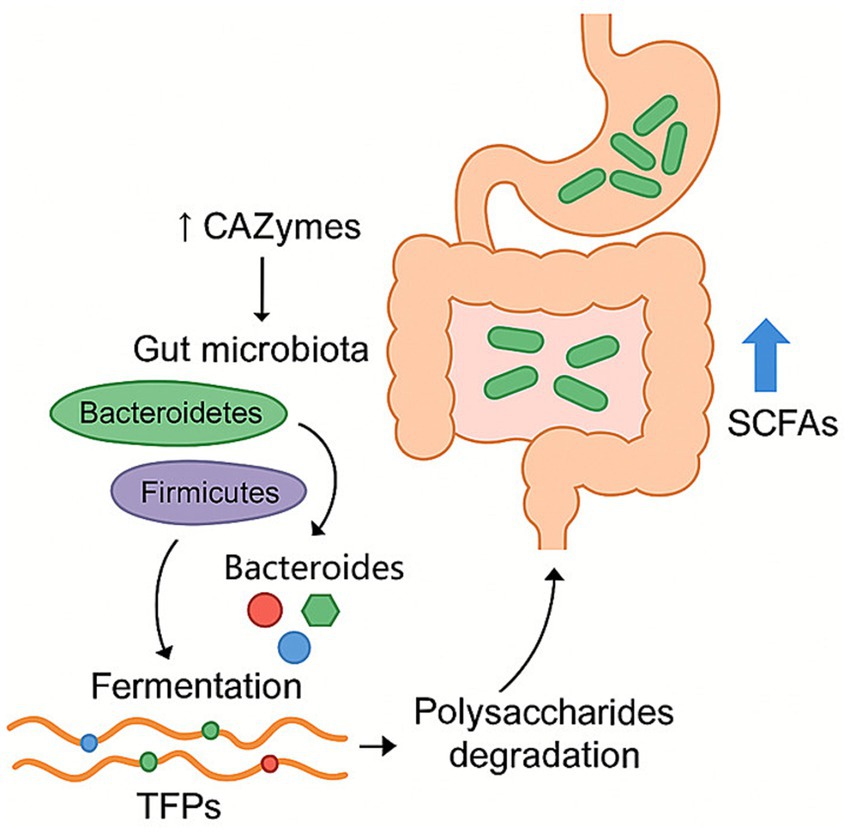

Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides can modulate the gut microbiota, where they are fermented by intestinal microbes, supporting microbial proliferation and increasing the production of short-chain fatty acids (Figure 3). Some reports show changing gut microbiota composition in vitro and in vivo of TFPs by fermentation. TFPs mainly affect the relative abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (22, 26, 28, 40). In the in vitro fermentation environment of healthy volunteers, when the molecular weight of polysaccharide was less than 1800 kDa, the relative abundance of Bacteroides increased, and that of firmicutes decreased. When the molecular weight of polysaccharide was more than 1800 kDa, the relative abundance of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes increased. Bacteroidetes was one of the main gut bacteria that were responsible for degrading polysaccharides. It released polysaccharide hydrolases and glycoside hydrolases for the degradation of the Gal side chain structures along with the backbone of TFPs. The pharmacological actions of TFPs on microbiome are shown in Table 2.

Figure 3. Regulation effect of TFPs on microbial homeostasis. TFPs are fermented by gut microbiota, particularly Bacteroidetes, which degrade them using CAZymes. This process promotes the proliferation of beneficial bacteria and leads to the production of SCFAs, thereby modulating the overall composition of the gut microbiome.

4.2 Regulation effect of TFPs on immunity

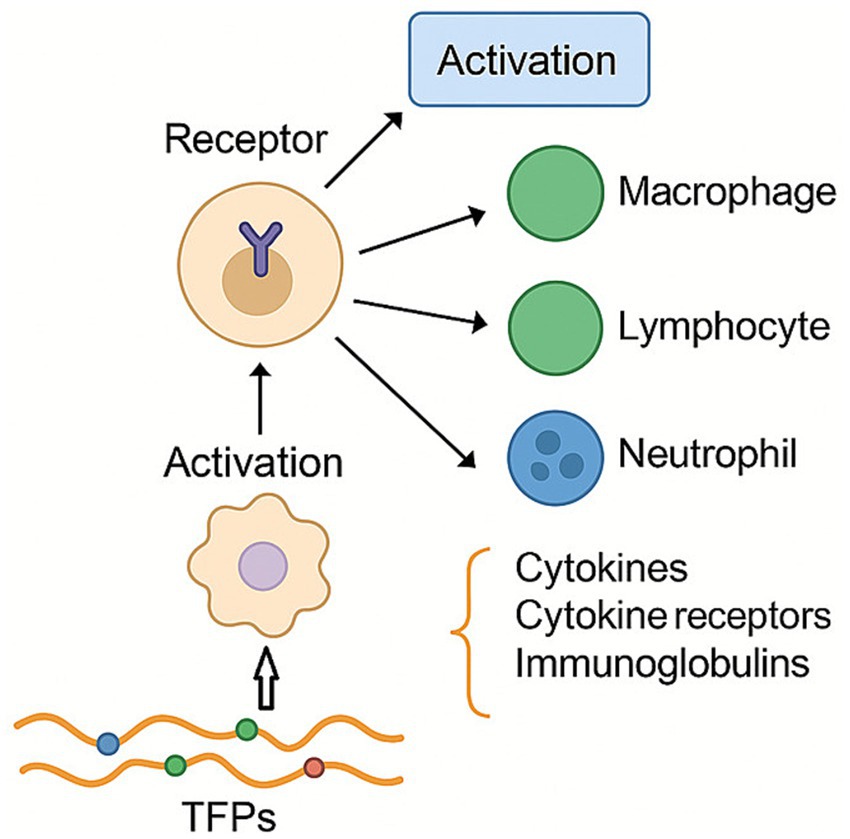

Studies have shown that plant polysaccharides exert their effects by binding to specific receptors on the surface of macrophages, thereby triggering their activation (Figure 4). TFPs not only activate various immune cells-such as macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and natural killer cells-but also stimulate the production of immune mediators, including cytokines, cytokine receptors, and immunoglobulins.

Figure 4. Regulation effect of TFPs on immunity. TFPs exert their effects by binding to immune cell receptors, leading to cell activation and the balanced secretion of cytokines.

Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides enhance cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (17). TFPs can reverse cyclophosphamide-induced reductions in peripheral blood leukocyte counts in rats. Notably, TFPs with lower molecular weight exhibits higher immune response (18). Xie et al. showed that both oral and topical TFPs alleviated symptoms of dinitrofluorobenzene-induced atopic dermatitis in mice by reducing skin barrier dysfunction, ear edema, and epidermal thickening, with oral administration proving more effective (22). TFPs treatment suppressed the activation of p38MAPK pathway, alleviated oxidative stress, reduced inflammatory cytokines, and scavenged reactive oxygen species (ROS) in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages (23). Additionally, TFPs reversed Treg-mediated immune suppression and reduced mortality in burn-induced septic mice by downregulating IL-10 and promoting Th1-to-Th4 transition (25).

Gao et al. (19–21) isolated 11 heteropolysaccharides (T1a-c, T2a-d, and T3a-d) from Tremella fuciformis, which induced IL-1, IL-6, and TNF production in human monocytes in vitro. Acidic hydrolysis products of T1a (T1a-1, T1a-2, T1a-3, T1a-4, and T1a-5) induced IL-6 production in human monocytes. Degradation products of T2a and T2b (T2a-S, T2a-L, and T2b-D) efficiently induced IL-1 secretion in monocytes. Various fragments of T3a acidic hydrolysate (T1a-2, T1a-3, T1a-4, T1a-5, and T1a-6a) induced IL-6 secretion in monocytes. The common (1 → 3)-mannan structure of the three heteropolysaccharides and their fragments likely underpins the immunomodulatory activity of TFPs, with molecular weight having no significant effect.

4.3 Regulation effect of TFPs on antioxidant system

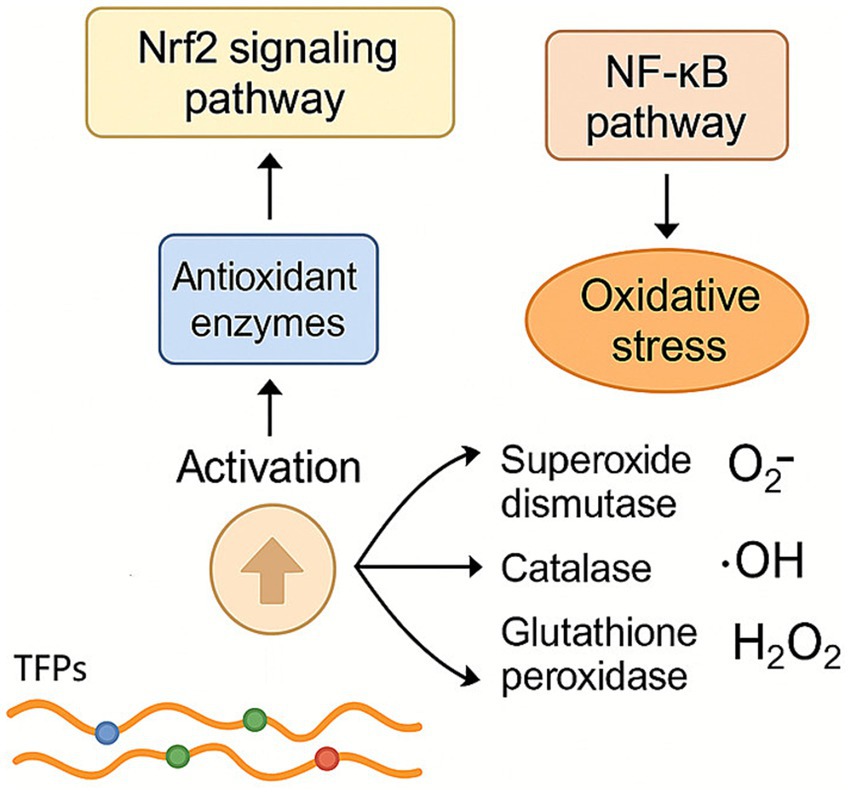

TFPs have demonstrated significant antioxidant regulatory functions through multiple mechanisms (Figure 5). TFPs enhance the activity of key antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, boosting cellular resistance to oxidative stress (6). They also activate the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway, promoting the expression of downstream antioxidant enzymes, while suppressing oxidative stress-induced inflammation via inhibition of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. TFPs also effectively scavenge ROS, such as superoxide anions (O₂−·), hydroxyl radicals (·OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), reducing oxidative damage (7, 8). Low molecular weight TFPs demonstrated strong hydroxyl radical scavenging activity, indicating that reducing molecular weight may enhance their overall antioxidant potential. These multifaceted mechanisms suggest that TFPs hold potential for preventing and treating oxidative stress-related diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes. However, further research is needed to elucidate their precise molecular targets and dose–response relationships.

Figure 5. Regulation effect of TFPs on antioxidant system. TFPs bolster cellular antioxidant defense by upregulating key enzymes (e.g., SOD, CAT) through the Nrf2 pathway, while simultaneously directly neutralizing various ROS. They also inhibit the NF-κB pathway to reduce subsequent inflammation.

4.4 Regulation effect of TFPs on lipid metabolism, blood glucose, and insulin resistance

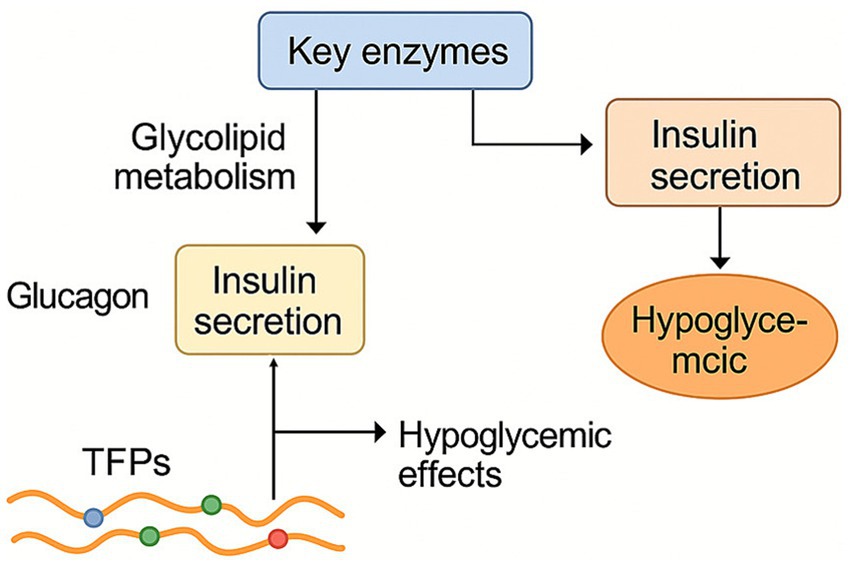

Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides can regulate key enzymes related to glycolipid metabolism and antagonize the elevation of glucagon (Figure 6). Additionally, TFPs promote insulin secretion, modulate the rates of glycogen synthesis and degradation, and contribute to the repair of damaged pancreatic islet cells, thereby exerting hypoglycemic effects. TFPs supplementation significantly alleviated weight gain, fat accumulation, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia induced by high-fat diet (40, 41). Khan et al. (29) evaluated the effects of Tremella fuciformis crude polysaccharide (TFCP) on lipid profiles. TFCP significantly inhibited hepatic lipid accumulation, and enzymes responsible for fat acid synthesis (including HMG-CoA reductase, acetyl-CoA carboxylase, and fatty acid synthase). TFPs treatment significantly also activated peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, a key regulator of insulin action (38). Additionally, glucuronide mannans from T. fuciformis seeds exhibited strong hypoglycemic effects, enhancing insulin secretion and hepatic glucose metabolism (39). The structure of glucuronide mannans is closely associated with its biological function, as glucuronide mannans with removed side chains was less active than natural glucuronide mannans.

Figure 6. Regulation effect of TFPs on lipid metabolism, blood glucose, and insulin resistance. TFPs alleviate hyperglycemia by stimulating insulin secretion and enhancing hepatic glucose metabolism. Concurrently, they reduce lipid accumulation by suppressing the expression and activity of key lipogenic enzymes.

4.5 Other pharmacological action of TFPs

A growing body of research highlights the neuroprotective and cognitive-enhancing effects of TFPs. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Ban et al. demonstrated that TFPs supplementation significantly improved subjective memory complaints, short-term memory, and executive function in individuals with cognitive impairment, accompanied by increased gray matter volume (30). TFPs also improves cognitive function by enhancing hippocampal CREB-positive neurons, glucose uptake, and cholinergic neurons (33, 35). Similarly, TFPs reversed scopolamine-induced memory deficits and promoted axonal growth and cholinergic activity (34).

The anti-tumor activity of TFPs is primarily manifested through the promotion of tumor cell apoptosis and immunostimulatory effects. Li and Xie et al. (13, 14) found that TFPs promoted apoptosis of B16 melanoma cells by inducing G2/M cell cycle arrest, and activating lipid transport and metabolism. TFPs can induces melanoma cell apoptosis by promoting M1 macrophage polarization (14). Han et al. explored the immunomodulatory and antitumor properties of polysaccharides derived from various Tremella fuciformis strains (12). Hot-water-extracted TFPs significantly increased mRNA levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Compared to hot water extracts, cold water-extracted TFPs exhibit stronger inhibitory effects on cancer cell viability and more effectively induce apoptosis.

5 Structure–activity relationship of TFPs

Polysaccharides with diverse biological activities exhibit substantial variation in their chemical composition, conformation, and physicochemical properties. However, elucidating the structure–activity relationships of TFPs remains challenging due to limited research. Nonetheless, several correlations have been reported.

Huang et al. characterized TFP-F1 with the structure [→3)-[β-D-GlcAp-(1 → 2)]-α-D-Manp-(1 → 3)-α-D-Manp-(1 → 3)-[α-L-Fucp- (1 →2)-β-D-Xylp-(1 → 2)]-α-D-Manp-(1→]n, partially acetylated at C6-OH of Man (16). At 1 μg/mL, TFP-F1 induced TNF-α and IL-6 production in J774A cells and promoted macrophage apoptosis via TLR4 signaling. Deacetylation abolished its immunomodulatory activity, highlighting the critical role of O-acetyl groups in cytokine induction.

Uronic acids are essential for TFPS bioactivity. Wu et al. evaluated five TFPs (TFP-I, TFPI-6, TFPI-12, TFPI-24, and TFPI-48), reporting that during human fecal fermentation, total polysaccharides declined from 91.19 to 65.95%, while uronic acid content decreased from 6.79 to 5.66% (26). TFP-I degradation accelerated between 12 and 48 h, with utilization reaching 53.76%, suggesting effective microbial fermentation and preferential use of uronic acids by colonic microbiota. Chiu et al. found that TFPs significantly mitigated HFD-induced obesity in mice (41). This effect was attributed to TFPs’ high viscosity and uronic acid content (26.7%), as uronic acids like galacturonic and glucuronic acids can bind cholesterol, potentially reducing lipid accumulation (70).

Chemical modification further enhances TFPS bioactivity. Sulfated TFPs show improved immunostimulatory, antiviral, and antioxidant properties, underscoring the role of structural modifications in optimizing biological function. Wang et al. synthesized carboxymethylated polysaccharides (CATP) from insoluble crude TFPS (71). Increased degrees of substitution (DS) improved water solubility, antioxidant, and moisturizing activities. Similarly, Liu et al. (68) reported that catechin-grafted TFPs exhibited enhanced thermal stability, crystallinity, and radical-scavenging capacity (66). These findings indicate that functional group grafting can substantially improve the antioxidant properties of TFPs, supporting their potential in food and pharmaceutical applications.

6 Summary

Tremella fuciformis has been traditionally used for thousands of years as a tonic, body builder, and anti-inflammatory agent. Polysaccharides, the primary bioactive components of Tremella fuciformis, have gained global attention for their molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, TPFs side chain positions, and correlations with physiological functions. Numerous studies have demonstrated that T. fuciformis polysaccharides possess diverse biological activities, including anti-tumor effects, antioxidant properties, immune regulation, anti-inflammatory actions, gastric protection, hepatoprotection, neuroprotection, hypoglycemic effects, radiation shielding, and drug delivery capabilities. However, most research on Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides is limited to preclinical studies using in vivo and in vitro animal models. The higher-order structure of TPF active components and their relationships with biological activities remain unclear. Future research should focus on clinical validation, structure–function relationships, gut microbiota interactions, and standardized production processes to support the development of TPF-based functional foods and therapeutics.

Author contributions

SL: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. KZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. JJL: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft. XL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HZ: Visualization, Writing – original draft. RC: Resources, Writing – original draft. JML: Supervision, Writing – original draft. JG: Visualization, Writing – review & editing. XB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Changzhi Traditional Chinese Medicine Inheritance and Innovation Demonstration Pilot Project (Grant Nos. 2023CZSZYY01; 2024CZSZYY01).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Zhang, L, and Wang, M. Polyethylene glycol-based ultrasound-assisted extraction and ultrafiltration separation of polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis (snow fungus). Food Bioprod Process. (2016) 100:464–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2016.09.007

2. Cheng, HH, Hou, WC, and Lu, ML. Interactions of lipid metabolism and intestinal physiology with Tremella fuciformis Berk edible mushroom in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet with or without Nebacitin. J Agric Food Chem. (2002) 50:7438–43. doi: 10.1021/jf020648q

3. Kim, K-A, Chang, H-Y, Choi, S-W, Yoon, J-W, and Lee, C. Cytotoxic effects of extracts from Tremella fuciformis strain FB001 on the human colon adenocarcinoma cell line DLD-l. Food Sci Biotechnol. (2006) 15:889–95.

4. Zhu, H, and Sun, SJ. Inhibition of bacterial quorum sensing-regulated behaviors by Tremella fuciformis extract. Curr Microbiol. (2008) 57:418–22. doi: 10.1007/s00284-008-9215-8

5. Mustafa, YF. Harmful free radicals in aging: a narrative review of their detrimental effects on health. Indian J Clin Biochem. (2023) 39:154–67. doi: 10.1007/s12291-023-01147-y

6. Fu, H, You, S, Zhao, D, An, Q, Zhang, J, Wang, C, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides inhibit UVA-induced photodamage of human dermal fibroblast cells by activating up-regulating Nrf2/Keap1 pathways. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2021) 20:4052–9. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14051

7. Ge, X, Huang, W, Xu, X, Lei, P, Sun, D, Xu, H, et al. Production, structure, and bioactivity of polysaccharide isolated from Tremella fuciformis XY. Int J Biol Macromol. (2020) 148:173–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.021

8. Shen, T, Duan, C, Chen, B, Li, M, Ruan, Y, Xu, D, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide suppresses hydrogen peroxide-triggered injury of human skin fibroblasts via upregulation of SIRT1. Mol Med Rep. (2017) 16:1340–6. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6754

9. Zhang, Z, Wang, X, Zhao, M, and Qi, H. Free-radical degradation by Fe2+/Vc/H2O2 and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Tremella fuciformis. Carbohydr Polym. (2014) 112:578–82. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.06.030

10. Gusman, JK, Lin, CY, and Shih, YC. The optimum submerged culture condition of the culinary-medicinal white jelly mushroom (Tremellomycetes) and its antioxidant properties. Int J Med Mushrooms. (2014) 16:293–302. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushr.v16.i3.90

11. Mustafa, YF. Chemotherapeutic applications of folate prodrugs: a review. Neuro Quantol. (2021) 19:99–112. doi: 10.14704/nq.2021.19.8.NQ21120

12. Han, CK, Chiang, HC, Lin, CY, Tang, CH, Lee, H, Huang, DD, et al. Comparison of immunomodulatory and anticancer activities in different strains of tremella fuciformis Berk. Am J Chin Med. (2015) 43:1637–55. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X15500937

13. Li, X, Su, Q, and Pan, Y. Overcharged lipid metabolism in mechanisms of antitumor by tremella fuciformis-derived polysaccharide. Int J Oncol. (2023) 62:1–16. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2022.5459

14. Xie, L, Liu, G, Huang, Z, Zhu, Z, Yang, K, Liang, Y, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide induces apoptosis of B16 melanoma cells via promoting the M1 polarization of macrophages. Molecules. (2023) 28:4018. doi: 10.3390/molecules28104018

15. Shi, X, Wei, W, and Wang, N. Tremella polysaccharides inhibit cellular apoptosis and autophagy induced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide in A549 cells through sirtuin 1 activation. Oncol Lett. (2018) 15:9609–16. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8554

16. Huang, TY, Yang, FL, Chiu, HW, Chao, HC, Yang, YJ, Sheu, JH, et al. An immunological polysaccharide from tremella fuciformis: essential role of acetylation in immunomodulation. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:10392. doi: 10.3390/ijms231810392

17. Zhou, Y, Chen, X, Yi, R, Li, G, Sun, P, Qian, Y, et al. Immunomodulatory effect of tremella polysaccharides against cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression in mice. Molecules. (2018) 23:239. doi: 10.3390/molecules23020239

18. Jiang, RZ, Wang, Y, Luo, HM, Cheng, YQ, Chen, YH, Gao, Y, et al. Effect of the molecular mass of tremella polysaccharides on accelerated recovery from cyclophosphamide-induced leucopenia in rats. Molecules. (2012) 17:3609–17. doi: 10.3390/molecules17043609

19. Gao, Q, Killie, MK, Chen, H, Jiang, R, and Seljelid, R. Characterization and cytokine-stimulating activities of acidic heteroglycans from tremella fuciformis. Planta Med. (1997) 63:457–60. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957733

20. Gao, Q, Seljelid, R, Chen, H, and Jiang, R. Characterisation of acidic heteroglycans from tremella fuciformis Berk with cytokine stimulating activity. Carbohydr Res. (1996) 288:135–42. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(96)90789-2

21. Gao, QP, Jiang, RZ, Chen, HQ, Jensen, E, and Seljelid, R. Characterization and cytokine stimulating activities of heteroglycans from Tremella fuciformis. Planta Med. (1996) 62:297–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-957888

22. Xie, L, Yang, K, Liang, Y, Zhu, Z, Yuan, Z, and Du, Z. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides alleviate induced atopic dermatitis in mice by regulating immune response and gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol. (2022) 13:944801. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.944801

23. Ruan, Y, Li, H, Pu, L, Shen, T, and Jin, Z. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides attenuate oxidative stress and inflammation in macrophages through miR-155. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). (2018) 2018:5762371. doi: 10.1155/2018/5762371

24. Lee, J, Ha, SJ, Lee, HJ, Kim, MJ, Kim, JH, Kim, YT, et al. Protective effect of Tremella fuciformis Berk extract on LPS-induced acute inflammation via inhibition of the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Food Funct. (2016) 7:3263–72. doi: 10.1039/C6FO00540C

25. Shi, ZW, Liu, Y, Xu, Y, Hong, YR, Liu, Q, Li, XL, et al. Tremella polysaccharides attenuated sepsis through inhibiting abnormal CD4+CD25(high) regulatory T cells in mice. Cell Immunol. (2014) 288:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.02.002

26. Wu, D-T, An, L-Y, Liu, W, Hu, Y-C, Wang, S-P, and Zou, L. In vitro fecal fermentation properties of polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis and related modulation effects on gut microbiota. Food Res Int. (2022) 156:111185. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111185

27. Xiao, H, Li, H, Wen, Y, Jiang, D, Zhu, S, He, X, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides ameliorated ulcerative colitis via inhibiting inflammation and enhancing intestinal epithelial barrier function. Int J Biol Macromol. (2021) 180:633–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.03.083

28. Xu, Y, Xie, L, Zhang, Z, Zhang, W, Tang, J, He, X, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides inhibited colonic inflammation in dextran sulfate sodium-treated mice via Foxp3+ T cells, gut microbiota, and bacterial metabolites. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:648162. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.648162

29. Khan, TJ, Xu, X, Xie, X, Dai, X, Sun, P, Xie, Q, et al. Tremella fuciformis crude polysaccharides attenuates steatosis and suppresses inflammation in diet-induced NAFLD mice. Curr Issues Mol Biol. (2022) 44:1224–34. doi: 10.3390/cimb44030081

30. Ban, S, Lee, SL, Jeong, HS, Lim, SM, Park, S, Hong, YS, et al. Efficacy and safety of Tremella fuciformis in individuals with subjective cognitive impairment: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Food. (2018) 21:400–7. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.4063

31. Jin, Y, Hu, X, Zhang, Y, and Liu, T. Studies on the purification of polysaccharides separated from Tremella fuciformis and their neuroprotective effect. Mol Med Rep. (2016) 13:3985–92. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5026

32. Hsu, SH, Chan, SH, Weng, CT, Yang, SH, and Jiang, CF. Long-term regeneration and functional recovery of a 15 mm critical nerve gap bridged by Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide-immobilized polylactide conduits. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2013) 2013:959261. doi: 10.1155/2013/959261

33. Park, HJ, Shim, HS, Ahn, YH, Kim, KS, Park, KJ, Choi, WK, et al. Tremella fuciformis enhances the neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells and restores trimethyltin-induced impairment of memory in rats via activation of CREB transcription and cholinergic systems. Behav Brain Res. (2012) 229:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.017

34. Kim, JH, Ha, HC, Lee, MS, Kang, JI, Kim, HS, Lee, SY, et al. Effect of Tremella fuciformis on the neurite outgrowth of PC12h cells and the improvement of memory in rats. Biol Pharm Bull. (2007) 30:708–14. doi: 10.1248/bpb.30.708

35. Park, KJ, Lee, SY, Kim, HS, Yamazaki, M, Chiba, K, and Ha, HC. The neuroprotective and neurotrophic effects of Tremella fuciformis in PC12h cells. Mycobiology. (2007) 35:11–5. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2007.35.1.011

36. Niu, B, Feng, S, Xuan, S, and Shao, P. Moisture and caking resistant Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides microcapsules with hypoglycemic activity. Food Res Int. (2021) 146:110420. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110420

37. Bach, EE, Costa, SG, Oliveira, HA, Junior, JS, Silva, KM, Marco, RM, et al. Use of polysaccharide extracted from Tremella fuciformis Berk for control diabetes in rats. Emir J Food Agric. (2015) 27:585–91. doi: 10.9755/ejfa.2015.05.307

38. Cho, EJ, Hwang, HJ, Kim, SW, Oh, JY, Baek, YM, Choi, JW, et al. Hypoglycemic effects of exopolysaccharides produced by mycelial cultures of two different mushrooms Tremella fuciformis and Phellinus baumii in Ob/Ob mice. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2007) 75:1257–65. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0972-2

39. Kiho, T, Tsujimura, Y, Sakushima, M, Usui, S, and Ukai, S. Polysaccharides in fungi. XXXIII. Hypoglycemic activity of an acidic polysaccharide (AC) from Tremella fuciformis. Yakugaku Zasshi. (1994) 114:308–15. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.114.5_308

40. He, G, Chen, T, Huang, L, Zhang, Y, Feng, Y, Qu, S, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide reduces obesity in high-fat diet-fed mice by modulation of gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. (2022) 13:1073350. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1073350

41. Chiu, CH, Chiu, KC, and Yang, LC. Amelioration of obesity in mice fed a high-fat diet with uronic acid-rich polysaccharides derived from Tremella fuciformis. Polymers (Basel). (2022) 14:1514. doi: 10.3390/polym14081514

42. Lin, M, Bao, C, Chen, L, Geng, S, Wang, H, Xiao, Z, et al. Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides alleviates UV-provoked skin cell damage via regulation of thioredoxin interacting protein and thioredoxin reductase 2. Photochem Photobiol Sci. (2023) 22:2285–96. doi: 10.1007/s43630-023-00450-0

43. Xu, W, Shen, X, Yang, F, Han, Y, Li, R, Xue, D, et al. Protective effect of polysaccharides isolated from Tremella fuciformis against radiation-induced damage in mice. J Radiat Res. (2012) 53:353–60. doi: 10.1269/jrr.11073

44. Chandra, NS, Gorantla, S, Priya, S, and Singhvi, G. Insight on updates in polysaccharides for ocular drug delivery. Carbohydr Polym. (2022) 297:120014. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.120014

45. Ukai, S, Kiriki, H, Nagai, K, and Kiho, T. Synthesis and antitumor activities of conjugates of mitomycin C-polysaccharide from Tremella fuciformis. Yakugaku Zasshi. (1992) 112:663–8. doi: 10.1248/yakushi1947.112.9_663

46. Guo, Z, and Tan, X. The curative effect of Tremella polysaccharide enteric-coated capsules in preventing and treating acute and chronic liver injury after blood tumor chemotherapy. Infect Dis Inf. (2005) 18:71.

47. Wang, Y, Sun, M, and Li, X. Clinical observation on the treatment of interferon-induced leukopenia by Tremella polysaccharide enteric-coated capsules. Hebei Med J. (2011) 33:411.

48. Huang, Z, Bai, J, and Wu, M. 58 cases of leukopenia treated by Tremella polysaccharides. Chongqing Med. (1982) 5:14–6.

49. Guaugze, C. Clinical study of preventive and curative effects of Tremella fuciforums Berk on tumor patients with leukopnia. Antibiotics. (1982) 7:52–5.

50. Liangfang, P. Clinical study about parenteral solution of Tremella polysaccharide improving quality of life of patients with liver cancer during chemotherapy. J Hubei Univ Chin Med. (2014) 16:2.

51. Zhang, L, Li, H, and Bai, H. Comparison of the determination of polysaccharide with 3, 5-dinitrosalicylic acid and phenol sulfate in Tremella polysaccharide enteric-coated capsules. Tianjin Pharm. (2008) 20:14–7.

52. Li, Q, Huang, C, Jiao, L, and Pan, S. Clinical study on the treatment of chronic active hepatitis with Tremella polysaccharide enteric-coated capsules. Infect Dis Inf. (2006) 19:201–2.

53. Zhao, X. Clinical observation on the treatment of mycoplasma pneumonia by the combination of tremella polysaccharide enteric-coated capsules and azithromycin. Chin Med Mod Dist Educ China. (2009) 7:111.

54. Schepetkin, IA, and Quinn, MT. Botanical polysaccharides: macrophage immunomodulation and therapeutic potential. Int Immunopharmacol. (2006) 6:317–33. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.10.005

55. Chen, G, Chen, K, Zhang, R, Chen, X, Hu, P, and Kan, J. Polysaccharides from bamboo shoots processing by-products: new insight into extraction and characterization. Food Chem. (2018) 245:1113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.059

56. Hou, J, Lan, J, and Guo, S. Studies on the process of the enzymatic reversal extraction of Tremella polysaccharides. Chin J Rehabil Med. (2009) 18:292–3.

57. Wang, L, Wu, Q, Zhao, J, Lan, X, Yao, K, and Jia, D. Physicochemical and rheological properties of crude polysaccharides extracted from Tremella fuciformis with different methods. J Food. (2021) 19:247–56. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2021.1884607

58. Wang, D, Wang, D, Yan, T, Jiang, W, Han, X, Yan, J, et al. Nanostructures assembly and the property of polysaccharide extracted from Tremella fuciformis fruiting body. Int J Biol Macromol. (2019) 137:751–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.198

59. Wu, DT, Deng, Y, Zhao, J, and Li, SP. Molecular characterization of branched polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis by asymmetrical flow field-flow fractionation and size exclusion chromatography. J Sep Sci. (2017) 40:4272–80. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201700615

60. Xu, J, Wang, D, Lei, Y, Cheng, L, Zhuang, W, and Tian, Y. Effects of combined ultrasonic and microwave vacuum drying on drying characteristics and physicochemical properties of Tremella fuciformis. Ultrason Sonochem. (2022) 84:105963. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.105963

61. Zou, Y, and Hou, X. Extraction optimization, composition analysis, and antioxidation evaluation of polysaccharides from white jelly mushroom, Tremella fuciformis (Tremellomycetes). Int J Med Mushrooms. (2017) 19:1113–21. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.2017024590

62. Xu, X, Chen, A, Ge, X, Li, S, Zhang, T, and Xu, H. Chain conformation and physicochemical properties of polysaccharide (glucuronoxylomannan) from fruit bodies of Tremella fuciformis. Carbohydr Polym. (2020) 245:116354. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116354

63. Wasser, S. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of antitumor and immunomodulating polysaccharides. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2002) 60:258–74. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1076-7

64. Kakuta, M, Sone, Y, Umeda, T, and Misaki, A. Comparative structural studies on acidic heteropolysaccharides isolated from "Shirokikurage," fruit body of Tremella fuciformis Berk, and the growing culture of its yeast-like cells. Agric Biol Chem. (2008) 43:1659–68. doi: 10.1080/00021369.1979.10863686

65. Ge, H. Purification, chemical characterization and antioxidant activity of alkaline solution extracted polysaccharide from Tremella fuciformis Berk. Bull Bot Res. (2010) 30:221–7.

66. Liu, J, Meng, CG, Yan, YH, Shan, YN, Kan, J, and Jin, CH. Structure, physical property and antioxidant activity of catechin grafted Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. (2016) 82:719–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.11.027

67. Lan, X, Wang, Y, Deng, S, Zhao, J, Wang, L, Yao, K, et al. Physicochemical and rheological properties of Tremella fuciformis polysaccharide fractions by ethanol precipitation. J Food. (2021) 19:645–55. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2021.1950212

68. Chen, YH, Jiang, RZ, Luo, HM, Wang, Y, and Gao, QP. Studies on establishing specific chromatogram of tremella polysaccharides by HPLC. Chin J Pharm Anal. (2012) 32:136–9.

69. Ma, X, Yang, M, He, Y, Zhai, C, and Li, C. A review on the production, structure, bioactivities and applications of tremella polysaccharides. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. (2021) 35:20587384211000541. doi: 10.1177/20587384211000541

70. Pau-Roblot, C, Courtois, B, and Courtois, J. Interactions between polysaccharides uronic acid sequences and lipid molecules. C R Chim. (2010) 13:443–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2009.10.006

71. Wang, X, Zhang, Z, and Zhao, M. Carboxymethylation of polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis for antioxidant and moisture-preserving activities. Int J Biol Macromol. (2015) 72:526–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.08.045

72. Zhu, X, Su, J, Zhang, L, Si, F, Li, D, Jiang, Y, et al. Gastrointestinal digestion fate of tremella fuciformis polysaccharide and its effect on intestinal flora: an in vitro digestion and fecal fermentation study. Food Innov Advances. (2024) 3:202–11. doi: 10.48130/fia-0024-0018

Keywords: Tremella fuciformis polysaccharides, structure–activity relationship, pharmacological action, functional foods, applications

Citation: Li S, Zhao K, Li J, Li X, Zhao H, Cui R, Li J, Guo J and Bian X (2025) Recent advances in polysaccharides from Tremella fuciformis: isolation, structures, bioactivities and application. Front. Nutr. 12:1663327. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1663327

Edited by:

Jing Gao, National Engineering Research Center for Oil Tea, ChinaReviewed by:

Cheng-Ting Zi, Yunnan Agricultural University, China;Maria Velez, Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAP), Argentina

Copyright © 2025 Li, Zhao, Li, Li, Zhao, Cui, Li, Guo and Bian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinbin Guo, Y2hhbmd6aGl6eW5iQDEyNi5jb20=; Xiangyu Bian, YmlhbmppbmZlbmcxOTkzQDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Siyu Li1,2,3†

Siyu Li1,2,3† Ke Zhao

Ke Zhao Jinjun Li

Jinjun Li Xiaoqiong Li

Xiaoqiong Li Xiangyu Bian

Xiangyu Bian