- 1Department of Clinical Laboratory, Aerospace Center Hospital, Beijing, China

- 2Translational Medicine Center, Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Melanoidins, complex brown polymers formed during the Maillard reaction in thermally processed or fermented foods, are increasingly recognized for their nutritional relevance beyond sensory contributions. Emerging evidence suggests that they may act as prebiotic-like compounds that resist human digestion and undergo microbial fermentation in the colon, producing metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). These metabolites are proposed to support intestinal barrier function, inflammation, and host metabolism. This review summarizes current knowledge on the gastrointestinal fate, microbial fermentation, and putative bioactivities of dietary melanoidins, with a focus on their interactions with gut microbiota. We compare the structural diversity among food sources and discuss potential health implications. However, most evidence to date derives from in vitro and animal studies, with limited clinical validation. Key challenges remain in classification, extraction, and the translation of preclinical findings into human applications. Addressing these gaps will be essential to establish the nutritional potential of melanoidin-rich foods in personalized and preventive nutrition strategies for gut health. Future studies integrating standardized extraction, structural characterization, and clinical validation are essential to establish the role of dietary melanoidins in personalized nutrition.

1 Introduction

The human gut harbors a complex and dynamic microbial ecosystem-the gut microbiota-which plays a pivotal role in immunometabolism, nutrient processing, and host defense. Fueled primarily by indigestible dietary components such as non-starch polysaccharides, resistant oligosaccharides, and resistant starch, these microorganisms produce a range of metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, and butyrate) and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), that contribute to maintaining intestinal homeostasis and immune regulation (1). A well-balanced gut microbiota forms a protective ecological barrier, while disruptions in microbial composition-often driven by poor diet-are linked to a range of health disorders. Although the benefits of dietary fibers, polypeptides, saponins, polysaccharides, and probiotics have been widely studied (2), melanoidins have recently emerged as novel modulators of gut health.

Melanoidins are nitrogen-rich brown polymers generated via the Maillard reaction-a non-enzymatic process involving reducing sugars and amino acids under heat. They are widely present in thermally processed or fermented foods such as roasted coffee (3), baked goods (4), grilled meats (5), and fermented foods like soy sauce (6–8). The estimated daily intake of melanoidins is approximately 10–12 g, with only 10–30% being absorbed by the host (9). Once regarded as biologically inert, they are now recognized for their microbiota-mediated health benefits (10).

Accumulating evidence indicates that melanoidins exert antioxidant (11), anti-inflammatory (12), and antimicrobial properties (13). In vitro and animal studies report shifts in microbial taxa (e.g., increases in Bifidobacterium) after exposure to melanoidin-rich substrates (14). Upon reaching the colon undigested, melanoidins are fermented by gut microbes, producing SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate (15). These metabolites contribute to improved mucosal barrier function, reduced inflammation, and provide energy for colonocytes. Melanoidin-rich foods such as coffee, whole grains, and roasted vegetables may therefore support a healthier gut microbiome and overall immune function (16).

Despite promising findings, the structural diversity of melanoidins-affected by food source and processing conditions-and individual differences in microbiota composition may lead to variable biological outcomes. Understanding these interactions is essential for unlocking their full therapeutic potential. In this review, we explore the formation, gastrointestinal fate, microbial fermentation, and health-related effects of dietary melanoidins. We aim to provide a comprehensive overview that supports future applications in functional food design and the dietary management of gut-related diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and colorectal cancer (13).

2 Methods

The manuscript is presented as a narrative review with transparent literature-search and selection procedures. We searched PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar for articles published up to 31 May 2025. Search terms combined keywords and synonyms for melanoidins and gut microbiota, such as “melanoidins,” “Maillard reaction products,” “gut microbiota,” “melanoidin fermentation,” “SCFAs,” “functional foods,” “intestinal health,” and “melanoidin metabolism.” No language restriction was applied at the search stage; however, only articles with an English abstract were screened. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers (J. C. and X. G.), and full texts were retrieved for potentially relevant citations. Inclusion criteria were: (i) original experimental studies (in vitro, animal in vivo, human intervention/observational) examining melanoidins or foods explicitly characterized as melanoidin-containing; (ii) mechanistic studies addressing melanoidin digestion, microbial metabolism, or physiological effects plausibly linked to melanoidins; (iii) reviews addressing melanoidins when providing mechanistic or compositional synthesis. Because the work is a narrative review synthesizing heterogeneous evidence across model systems, no meta-analysis was attempted.

3 The formation and composition of melanoidins

Melanoidins are complex, bioactive compounds formed through the Maillard reaction between reducing sugars and amino acids during food processing (17). They contribute not only to the characteristic color, flavor, and aroma of cooked foods, but are also increasingly associated with several health benefits (17).

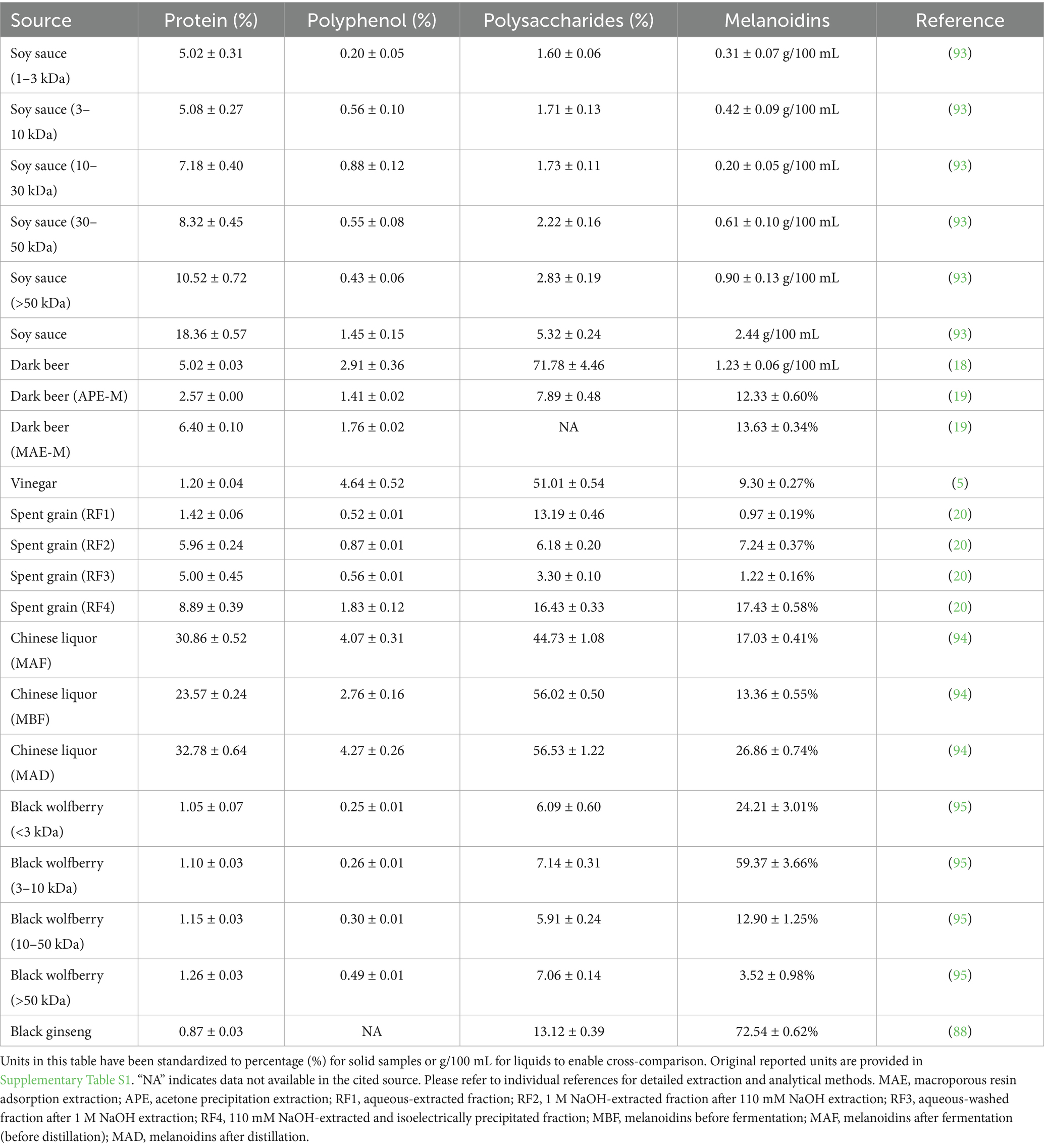

Growing evidence indicates that melanoidins are not inert but may actively promote gut homeostasis (15), which encompasses a balanced microbiota, intestinal barrier integrity, immune regulation, and metabolic health. As summarized in Figure 1, melanoidins support gut homeostasis through multiple mechanisms: (a) Modulating gut microbial composition: They can alter the balance of beneficial and harmful bacteria in the gut, fostering a healthier microbiome. (b) Regulating intestinal homeostasis: Melanoidins have anti-inflammatory properties that help mitigate chronic gut inflammation. (c) Supporting the intestinal mucosal barrier: They enhance the strength and function of the intestinal lining, preventing the leakage of harmful substances into the bloodstream. (d) Adjust intestinal pH value: They help maintain an optimal pH in the intestines, creating an environment that favors beneficial bacteria and inhibits pathogenic organisms.

Figure 1. Melanoidins influence gut homeostasis. Melanoidins promote gut health via four main pathways: (a) modulation of microbial composition (increasing Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus while reducing pathogenic taxa), (b) reinforcement of intestinal barrier function through mucin and tight junction proteins, (c) regulation of intestinal pH that favors beneficial microbes, and (d) exertion of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Created using Biorender, licensed under Academic License.

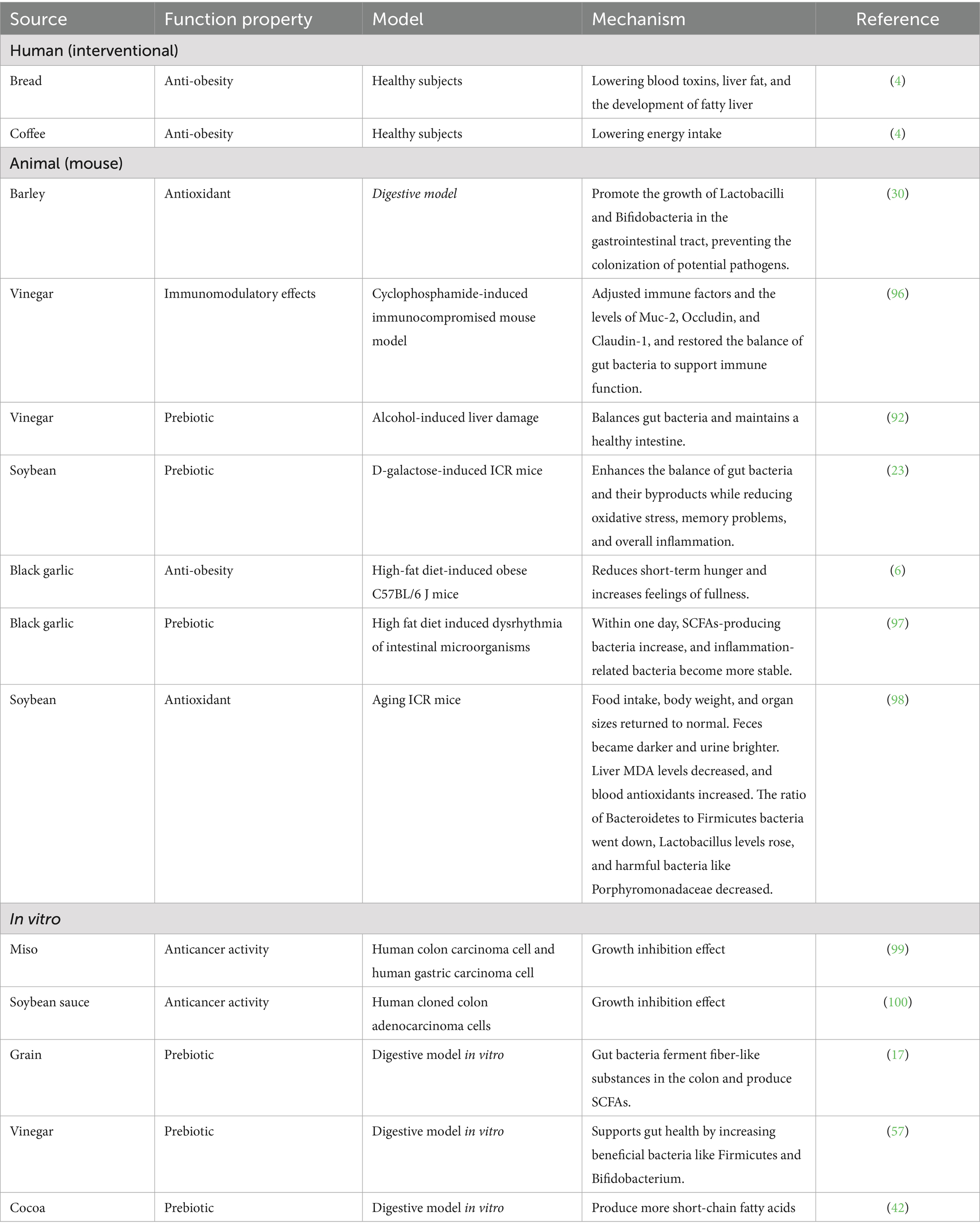

The health effects of melanoidins vary by dietary source due to structural differences and food matrix influences (Table 1). While a food-source categorization (e.g., soy, grain) offers an intuitive framework, it may obscure the fundamental structural heterogeneity of melanoidins. Their functional properties are ultimately governed by structural features such as molecular weight, the nature of incorporated phenolic compounds, and the polysaccharide-to-protein ratio, which vary not only between sources but also within processing conditions of the same food. Therefore, the following discussion, while organized by common dietary sources, will emphasize these underlying structural and functional characteristics.

As summarized in Table 1, the composition of melanoidins varies dramatically across sources. For instance, soy sauce melanoidins are characterized by a relatively high protein content (>5%), whereas melanoidins from dark beer and vinegar are exceptionally rich in polysaccharides (>50%), a feature that likely dictates their strong prebiotic potential (18, 19). The notable variation in polyphenol incorporation, as seen in vinegar (4.64%) compared to spent grain fractions (0.52–1.83%), may contribute to differences in their antioxidant capacities (5, 20). The significant impact of extraction protocols and the food matrix on these compositional profiles underscores that source alone is an inadequate predictor of function. Thus, moving beyond a simplistic food-category classification to a structure- and function-centric understanding is crucial for harnessing the full potential of melanoidins in gut health.

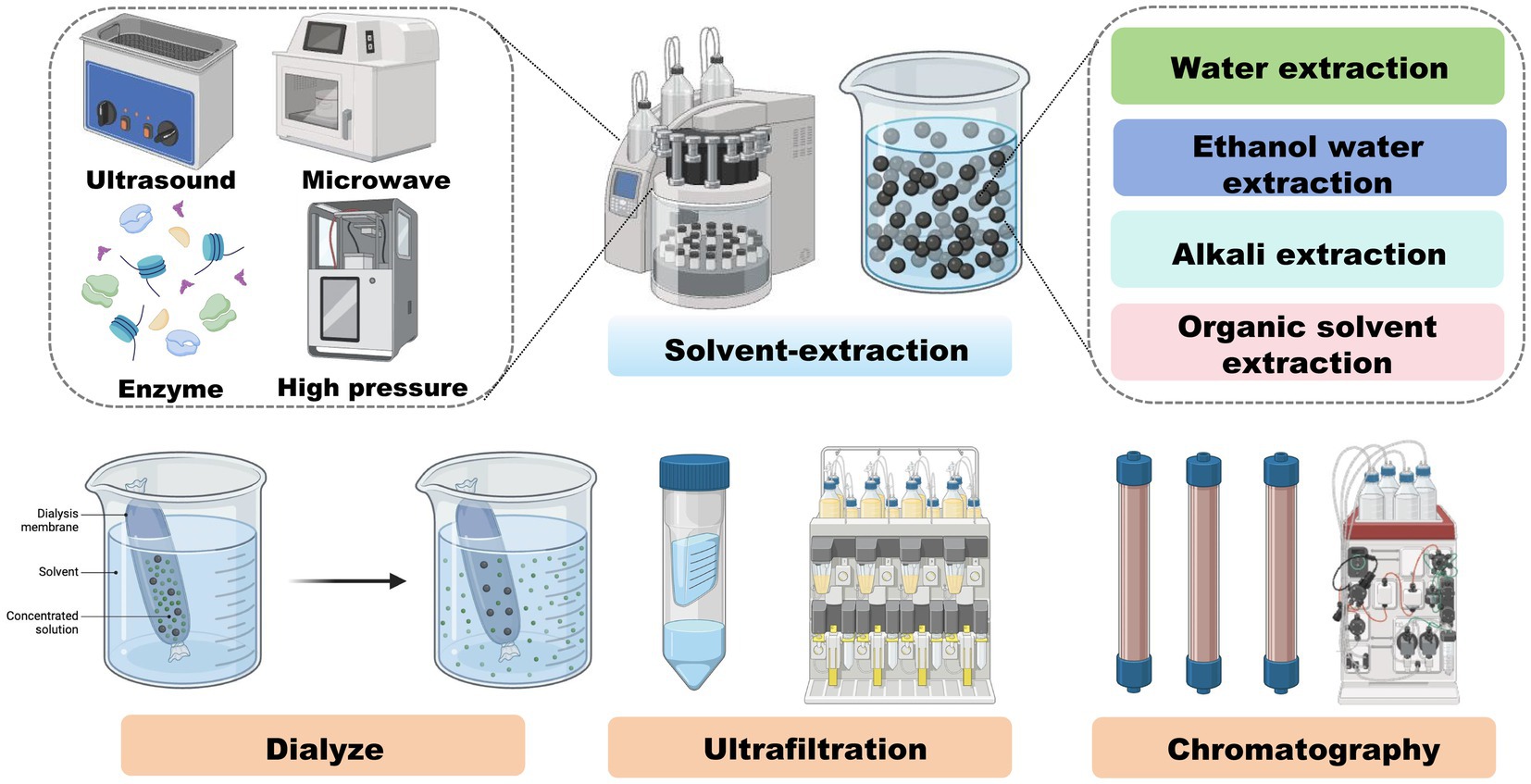

The main processes and analytical techniques applied to isolate and characterize melanoidins are summarized in Figure 2, which highlights the methodological variability contributing to heterogeneous study outcomes. Typical protocols involve aqueous or alkaline solvent extraction under heating, followed by centrifugation and filtration. Further purification may involve dialysis, ultrafiltration, or chromatography (e.g., size-exclusion or ion-exchange). Isolated melanoidins are then characterized using advanced tools such as HPLC and mass spectrometry.

Figure 2. The formation and extraction of melanoidins. Workflow summarizing the Maillard reaction during food processing (soy, grains, coffee, vinegar, etc.) leading to melanoidin formation, followed by extraction methods (aqueous/alkaline extraction, ultrafiltration, chromatography) and structural characterization (HPLC, MS). Created using Biorender, licensed under Academic License.

Efficient extraction and separation are essential to advance our understanding of melanoidin structures and their specific interactions within the gut environment, ultimately elucidating their role in sustaining gut homeostasis.

3.1 Melanoidins from plant-based sources: soy and legumes

Soybeans are a dietary staple rich in bioactive compounds, including reducing sugars (21), proteins, and isoflavones (2). Soy-based melanoidins are formed when these components undergo the Maillard reaction during heating, cooking, or fermentation (22). Unlike some other melanoidins, they are derived from a plant-based matrix that also contains fiber, polyphenols, and antioxidants, enhancing their potential bioactivity.

These melanoidins, abundant in fermented soybean products such as soy sauce, douchi, and miso, exhibit several gut health-promoting properties. They function as prebiotics by selectively stimulating beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, thereby supporting microbial balance and reducing dysbiosis risk (23). Additionally, soy melanoidins demonstrate anti-inflammatory activities that may alleviate gut inflammation related to IBS or IBD (24).

Their antioxidant properties further contribute to gut protection by mitigating oxidative stress, which can compromise intestinal barrier integrity and lead to conditions such as leaky gut syndrome (25). Through these combined mechanisms, soy-based melanoidins help maintain mucosal defense and overall gut homeostasis.

3.2 High fiber associated melanoidins: cereals and grains

Grain-based foods such as whole wheat, barley, oats, and rice are excellent sources of dietary fiber, vitamins, and minerals (26). During their processing and cooking, the Maillard reaction occurs, leading to the formation of melanoidins. These melanoidins, found in roasted, baked, or fermented grains, possess a distinctive chemical structure that can specifically influence gut homeostasis. Typically, polysaccharide-based, grain-derived melanoidins are commonly present in products like dark beer (19), vinegar (27), and black bread (28).

Grain-based melanoidins are generally more resistant to digestion by human enzymes, meaning they are likely to reach the colon, where they interact with the gut microbiota (29). Studies have shown that grain-derived melanoidins can act as prebiotics, promoting the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, particularly fiber-fermenting bacteria that contribute to the production of SCFAs (30). Additionally, grain-based melanoidins may help regulate the microbiota’s composition by enhancing the growth of beneficial microbes while inhibiting the growth of harmful bacteria (31). This regulation helps maintain microbial diversity, which is essential for the optimal functioning of the gut microbiome. Grain-based melanoidins, therefore, contribute to gut homeostasis by fostering a balanced microbial environment and supporting the production of metabolites that promote intestinal health. Furthermore, grain-based melanoidins have been shown to possess antioxidant (32) and anti-inflammatory properties (33), which may help mitigate oxidative stress and inflammation within the gut. This action could be particularly beneficial in protecting against chronic diseases, such as colorectal cancer or metabolic disorders, that are associated with gut inflammation and dysbiosis.

3.3 Diverse source melanoidins: coffee, fruits, and herbs with distinct bioactivities

Melanoidins are also derived from diverse sources beyond soy and grains, including coffee, roasted fruits, processed herbs, and fermented blackened foods (6). Their structural and functional properties vary considerably depending on raw materials and processing conditions, leading to distinct impacts on gut health (34). For instance, coffee melanoidins are formed during the roasting process, which involves high temperatures that promote extensive Maillard reactions, resulting in complex polymers rich in aromatic compounds (35). Similarly, roasted fruits such as apples (36) and potatoes (37) develop melanoidins that retain some of their original nutrients while acquiring new bioactive properties. Processed herbs, such as ginseng (38), wolfberry (39), ophiopogonis (40), rehmannia glutinosa (41), etc., contain melanoidins that contribute to their characteristic dark color and robust flavors, while also offering potential prebiotic effects that support beneficial gut bacteria. The chemical structure of melanoidins varies significantly across these different sources, leading to diverse biological activities. For example, coffee melanoidins are known for their high antioxidant capacity (32), which can help reduce oxidative stress in the gut. In contrast, melanoidins from roasted cocoa may be more effective in modulating specific microbial populations (42). These functional differences underscore the need for source-specific research to elucidate how different melanoidins interact with the gut environment. Investigating a broader range of melanoidin-rich materials will facilitate their targeted use in promoting microbiome balance and gut health.

In conclusion, the diverse sources and structural complexity of melanoidins underlie their multifaceted roles in modulating gut homeostasis. The melanoidins exert distinct prebiotic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects, largely mediated through microbial fermentation and metabolic activity in the colon (43). These interactions enhance beneficial microbiota, strengthen intestinal barrier function, and mitigate inflammation-key mechanisms in maintaining gut health (44). However, the efficacy and physiological impact of melanoidins are influenced by their food matrix, chemical structure, and individual gut microbiota composition. However, the effects of different sources vary significantly, but the research methods are inconsistent, making it difficult to compare the results horizontally. Future research should prioritize human trials and multi-omics approaches to clarify dose–response relationships, individual variability, and the synergistic effects of melanoidins with other dietary components. Such insights will be essential for developing targeted nutritional strategies to prevent gut-related disorders and promote health through diet.

4 The biological fate of dietary melanoidins through the gastrointestinal tract

Dietary melanoidins, complex nitrogen-rich compounds formed during the Maillard reaction in foods like roasted coffee, baked goods, and grilled meats, play an intriguing role in human health (45). Unlike many other dietary components, melanoidins are not fully digested by human enzymes in the gastrointestinal tract (46). Instead, they interact with the gut microbiota, which plays a key role in their breakdown and metabolism (47). The biological fate of dietary melanoidins involves several stages in the gastrointestinal tract, where they undergo digestion, fermentation, and modification by microbial activity (48). These processes lead to the formation of various metabolites that can influence gut health, immune function, and even systemic metabolism. Current evidence on the gastrointestinal processing of dietary melanoidins comes predominantly from in vitro simulated digestion and fermentation studies, complemented by animal experiments; human in vivo digestion data are scarce.

4.1 Digestion of melanoidins in the stomach and small intestine

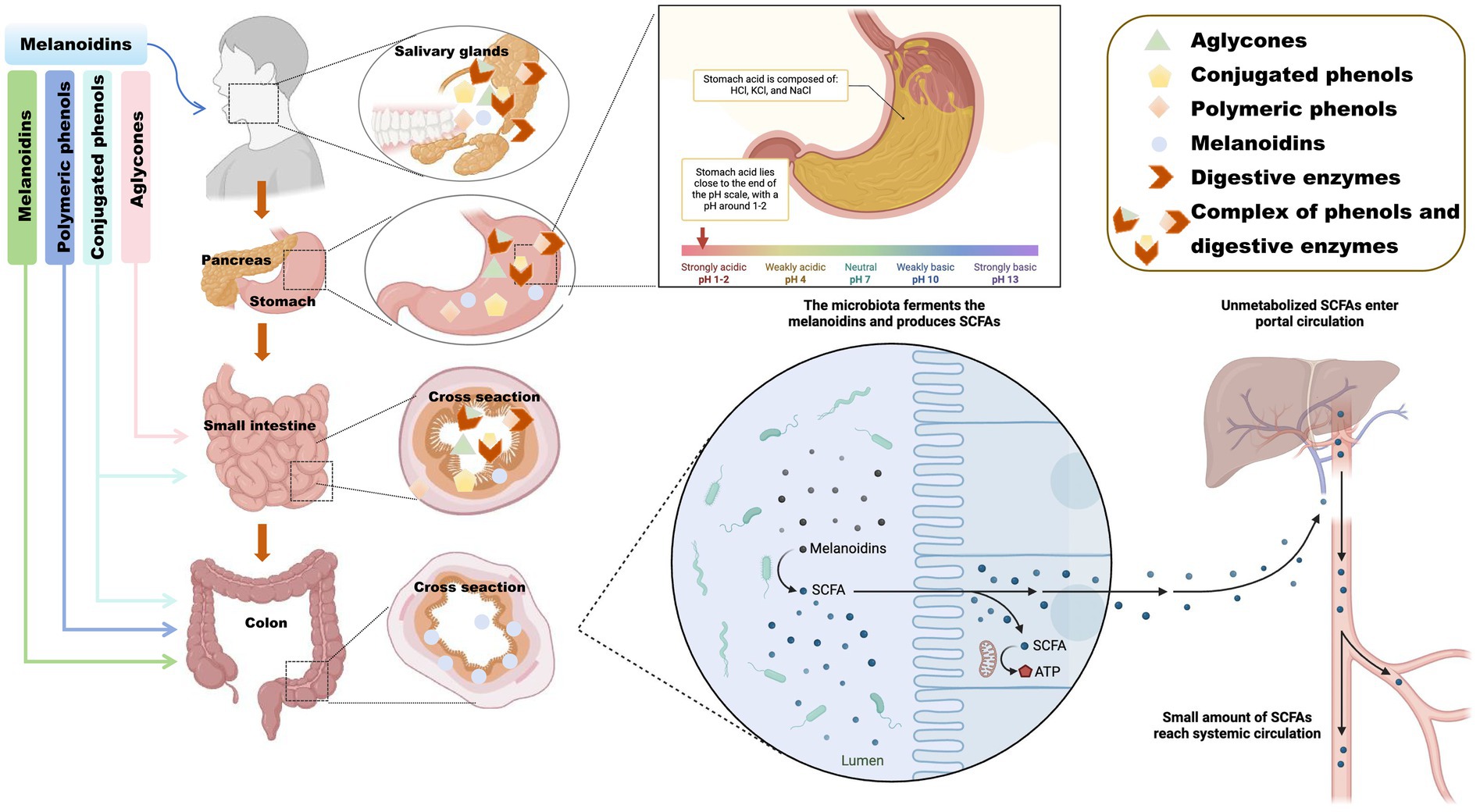

Upon ingestion, melanoidins enter the stomach and are exposed to its acidic environment (pH 1.5–3.5), which facilitates the release of bound phenolics that may exert bioactivity locally (49). Nevertheless, melanoidins remain largely resistant to human digestive enzymes such as amylases, lipases, and proteases (28). As shown in Figure 3, they pass undigested through the stomach and small intestine, where pancreatic enzymes also fail to hydrolyze them significantly (50, 51).

Figure 3. Digestive mechanism diagram of melanoidins. Schematic illustration showing the resistance of melanoidins to enzymatic digestion in the stomach and small intestine, followed by their arrival in the colon where gut microbiota metabolizes them into bioactive compounds, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and phenolic derivatives. The figure highlights two key roles: (1) melanoidins as carriers for polyphenols, protecting them from early degradation, and (2) their fermentation by colonic microbes, leading to SCFA production that supports intestinal health. Created using Biorender, licensed under Academic License.

Thus, most melanoidins proceed intact to the colon and become available for microbial fermentation. The gut microbiota possesses specialized enzymes that degrade melanoidins into absorbable metabolites with potential bioactivity (52). For example, roasted coffee-rich in melanoidins-shows stronger antioxidant activity than green coffee, partly due to Maillard reaction products and modified phenolic profiles (53). Although fermented green coffee yields more total SCFAs, melanoidins in roasted coffee may enhance bioavailability and microbial metabolism through two key mechanisms: acting as carriers that facilitate polyphenol release and absorption in the small intestine, and serving as fermentable carbon sources for colonic microbiota, thereby promoting SCFA production (33).

4.2 Melanoidins metabolism by gut microbiome

The gut microbiota plays a central role in the metabolism of melanoidins (54). Although these compounds are resistant to human digestive enzymes, many gut bacteria can ferment or modify them. Melanoidins can be utilized by gut microbes, leading to the production of SCFAs and shaping their community structure. Many melanoidins promote the growth of beneficial genera such as Bifidobacterium and Faecalibacterium (30). By fermenting melanoidins, gut microbes can release some phenolic compounds initially linked to the melanoidin backbone, which in turn can enhance the absorption of phenolics. Analysis of these polyphenols can be used to investigate the structure of melanoidins and to explore microbial metabolic pathways (17). The breakdown of melanoidins by gut microbes results in the production of various metabolites that significantly impact intestinal health and overall physiological functions (55). While the direct decomposition of melanoidins primarily releases phenolic metabolites, it also significantly stimulates the growth of SCFA-producing bacteria, leading to an increased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (6). These substances have a systemic impact on the host’s energy balance, inflammatory response, and lipid metabolism by regulating the structure and metabolic function of the intestinal flora.

4.2.1 Melanoidin-specific metabolites

4.2.1.1 Phenolic compounds

Polyphenols represent important structural components within melanoidins. Although melanoidins are generally resistant to digestion, they can release polyphenols through microbial fermentation in the colon, allowing these bioactive compounds to exert systemic effects (52). Melanoidins thereby function as a natural carrier for polyphenols, improving their stability and bioavailability throughout the gastrointestinal tract (56). This binding protects polyphenols from premature degradation by digestive enzymes and enables their targeted release in specific gut regions. The gradual liberation of polyphenols from melanoidins supports sustained antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, which are crucial for maintaining gut health. Furthermore, melanoidin-bound polyphenols play a key role in modulating the gut microbiota. They selectively stimulate beneficial bacteria, including Firmicutes and Bifidobacterium, while suppressing pathogenic species, thereby promoting microbial balance and helping to prevent dysbiosis-related disorders (57). Additionally, the antioxidant properties of polyphenols derived from melanoidins help mitigate oxidative stress within the intestinal environment, protecting epithelial cells from damage and supporting the maintenance of the intestinal barrier function (43). By reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, these compounds play a crucial role in preventing the onset and progression of IBD and IBS.

Future research should focus on elucidating the specific mechanisms through which melanoidin-bound polyphenols interact with the gut microbiota and host cells. Understanding these interactions will provide deeper insights into the development of functional foods and therapeutic strategies aimed at enhancing gut health and overall well-being.

4.2.2 General microbial metabolites potentially influenced by melanoidins

4.2.2.1 SCFAs

The microbial fermentation of melanoidins yields SCFAs-mainly butyrate, acetate, and propionate-which play essential roles in gut health (2, 58). Butyrate serves as the primary energy source for colonocytes, strengthens the intestinal barrier, and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects (59). Acetate and propionate contribute to lipid metabolism and modulate gut microbial composition (47). By lowering colonic pH, SCFAs also inhibit pathogens while supporting beneficial bacteria (34).

As signaling molecules, SCFAs bind to receptors such as GPCR41 and GPCR43, helping to regulate immune and metabolic pathways—including cytokine production and inflammation control—which may protect against chronic diseases (60–62). SCFAs also influence the gut–brain axis; butyrate, for example, helps maintain blood–brain barrier function and reduce neuroinflammation, thereby potentially supporting cognitive health (63, 64). Furthermore, SCFAs contribute to appetite regulation and energy homeostasis, suggesting relevance in managing obesity (65).

The benefits of melanoidin fermentation, however, vary with diet, microbial diversity, and other bioactive compounds (29). Future studies should clarify the mechanisms behind melanoidin-host interactions and explore personalized nutrition strategies to maximize their health potential (66).

4.2.2.2 Ammonia

Ammonia is another byproduct of the microbial fermentation of proteins and complex compounds like melanoidins (51). Some bacteria in the gut, particularly proteolytic bacteria, break down amino acids and peptides, releasing ammonia as a byproduct. While small amounts of ammonia are used by the body for the synthesis of urea, excessive ammonia can be toxic and is implicated in gut dysfunction, such as in IBD (67). However, the production of ammonia from melanoidins may be influenced by the specific microbial communities present in the gut, with some strains of bacteria being more efficient at producing ammonia than others (68). In addition, ammonia can also serve as one of the precursors for the formation of melanoidins. The processes of its formation and release may undergo dynamic changes within the body (69), thereby affecting the physicochemical properties of melanoidins (70).

4.2.2.3 BAs (biogenic amines)

BAs, such as putrescine, cadaverine, and histamine, are another class of metabolites produced by the gut microbiota during the fermentation of dietary compounds like melanoidins (71–73). These amines are formed from the decarboxylation of amino acids and are associated with both beneficial and detrimental effects on health (74). At low concentrations, BAs can have positive effects on gut health, such as acting as signaling molecules that regulate gut motility and microbial interactions (75). However, excessive levels of biogenic amines, particularly histamine, can lead to adverse effects such as headaches, digestive disturbances, and allergic reactions (76). Melanoidins are enriched in soy-based fermented foods, and the control of BAs is crucial to ensure the safety of fermented soybean products (22).

4.2.2.4 ICs (indolic compounds)

ICs are produced from the microbial fermentation of tryptophan, an essential amino acid that is present in melanoidins (77, 78). These compounds, including indole and its derivatives, can influence gut health by acting on the gut-brain axis (79). Some ICs have been shown to have neuroactive properties, affecting mood and cognitive function (80). In the gut, indolic compounds can also modulate inflammation and microbial activity, playing a role in maintaining gut homeostasis. However, imbalances in the production of indolic compounds may contribute to the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal disorders.

4.2.2.5 H2S

H2S is a gas that is produced by certain gut bacteria during the fermentation of sulfur-containing compounds, including those found in melanoidins (81). While H2S is often considered a toxic compound due to its strong odor and association with gut dysfunction, recent studies have shown that it also has beneficial roles in gut health (82). At low concentrations, H2S acts as a signaling molecule, helping to regulate mucosal integrity, promote blood flow to the colon, and modulate inflammation (83). However, excessive production of H2S can lead to adverse effects, such as damage to intestinal cells and dysbiosis (microbial imbalance).

4.2.2.6 Other GMMs

In addition to the metabolites mentioned above, the fermentation of melanoidins can lead to the production of a wide range of other GMMs that may influence health (84). These include various organic acids, gases (e.g., methane and carbon dioxide), and peptide derivatives that can impact gut pH, microbial composition, and overall gut function (26). The complex interplay between these metabolites can influence the gut’s immune response, nutrient absorption, and protection against pathogenic bacteria.

In summary, phenolic compounds are directly released from the melanoidin structure and are thus considered core melanoidin-specific metabolites. In contrast, other metabolites such as SCFAs, ammonia, BAs, ICs, and H2S represent general microbial fermentation products. Their production can be influenced by melanoidins, but they are not unique to melanoidin metabolism, as they are derived from common pathways involving proteins, amino acids, and carbohydrates (85). Although existing studies have indicated that melanoidins can release various metabolites through microbial fermentation in the colon, and potentially influence gut health via modulation of the gut microbiota, immune responses, and metabolic pathways, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding their precise mechanisms of action and overall physiological effects (86). Current evidence is largely derived from in vitro or animal models, with a lack of validation in humans, particularly across individuals with varying health statuses. Future research should integrate multi-omics technologies, in vitro fermentation models, and human intervention trials to systematically elucidate the relationship between melanoidins and host-microbiota interactions, with emphasis on their potential application in personalized nutrition and functional food development.

5 Effect of melanoidins on gut-associated diseases

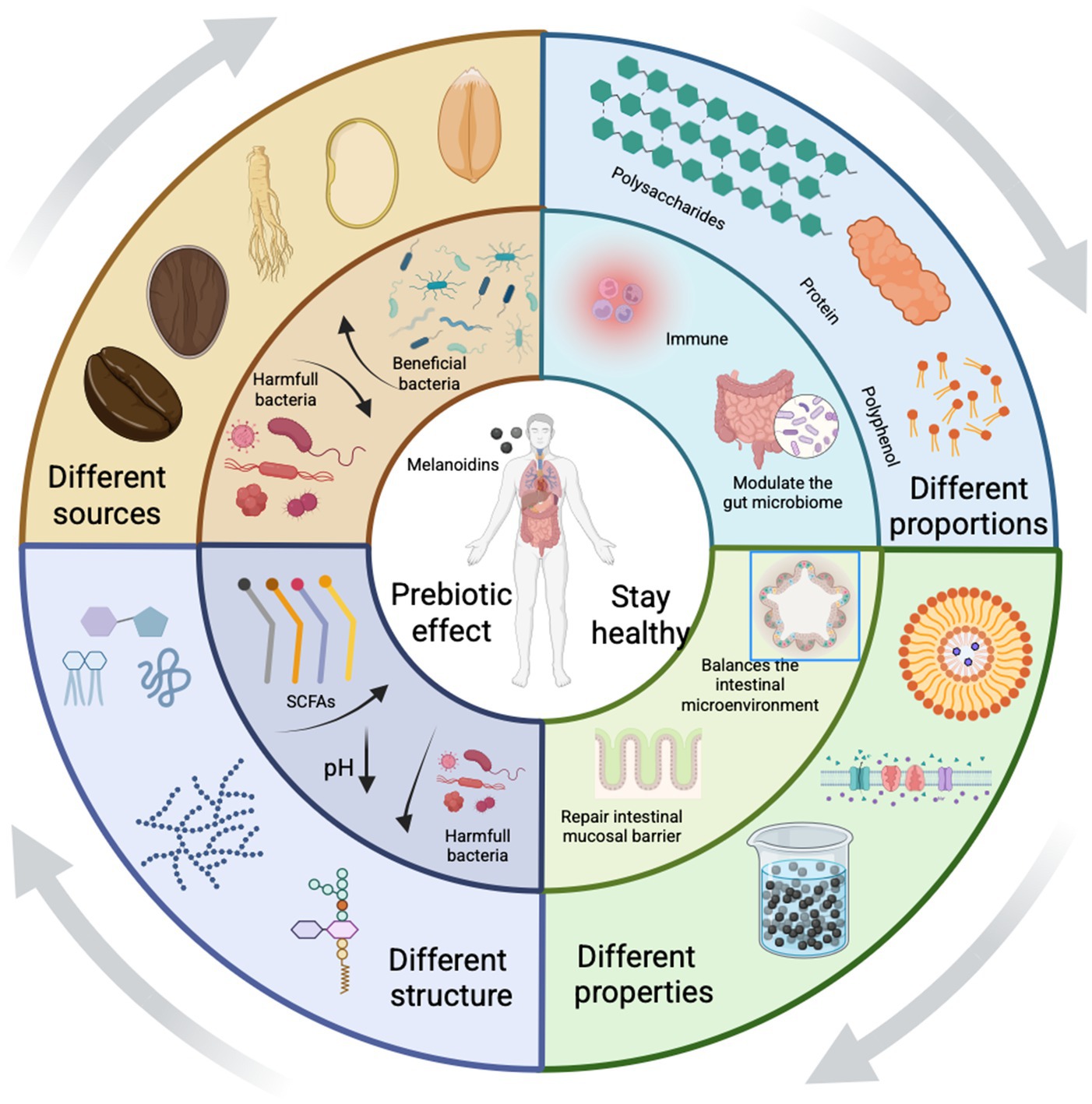

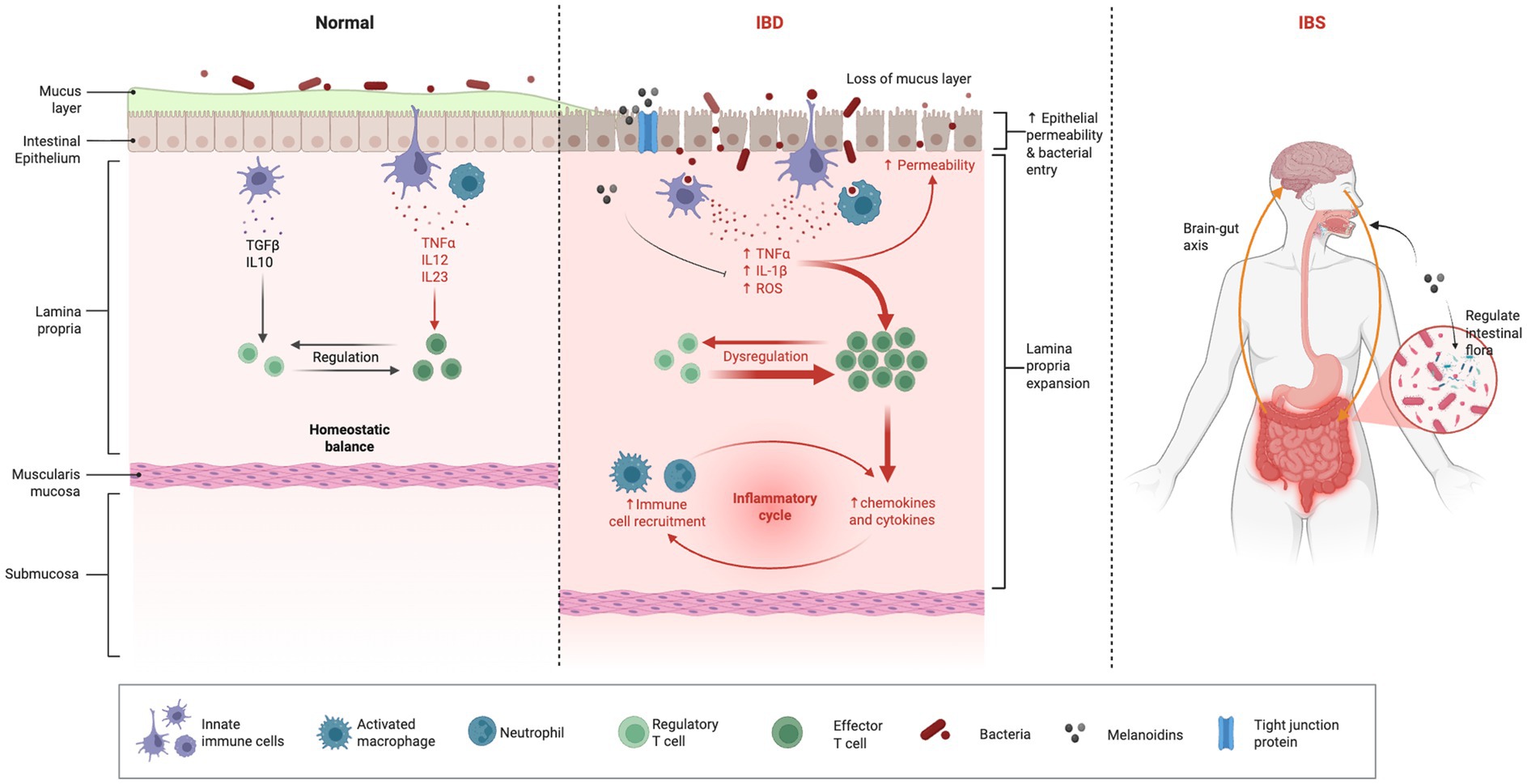

The gut is a complex and dynamic environment where microbial, immune, and epithelial cells interact to maintain health. However, disturbances in this balance can lead to gut-associated diseases (Table 2), such as IBD and IBS. Melanoidins, complex compounds formed during the Maillard reaction in various foods, have emerged as potential modulators of gut health (30). Their influence on the gut microbiota, intestinal barrier integrity, and immune responses suggests that they could play a beneficial role in the prevention and management of these gut-associated diseases. This section explores the potential effects of melanoidins on two common gastrointestinal conditions: IBD and IBS (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effect of melanoidins on gut homeostasis. Diagram showing how melanoidins may alleviate IBD and IBS by restoring microbial balance, enhancing SCFA production, reducing oxidative stress, and reinforcing mucosal barrier function. Created using Biorender, licensed under Academic License.

5.1 IBD

IBD, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, involves chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract driven by dysregulated immune responses, genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers, and gut dysbiosis (Figure 2). Melanoidins offer potential therapeutic benefits in IBD due to their antioxidant (45), anti-inflammatory (27), and prebiotic properties, although current evidence is primarily derived from preclinical studies.

Studies using in vitro and animal models indicate that melanoidins can alleviate gut inflammation and oxidative stress (87). They have been shown to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) and suppress key signaling pathways such as NF-κB (Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells) and AMPK (Adenosine 5’-Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase) (27, 88, 89). Additionally, melanoidins act as prebiotics, promoting beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which produce short-chain fatty acids such as butyrate that are known to enhance barrier function and dampen inflammation (17, 90), potentially enhance intestinal barrier integrity, reduce inflammation, and support mucosal immunity. By restoring microbial balance, melanoidins could help address dysbiosis, a central feature of IBD.

Melanoidins also show potential in strengthening intestinal barrier integrity by stimulating mucin secretion and tight junction proteins (e.g., ZO-1, occludin, claudin-1) in preclinical models. This may reduce permeability and prevent the translocation of pathogens and toxins (91). For instance, vinegar melanoidins were shown to improve gut microbiota composition, inhibit ROS, and suppress pro-inflammatory factors in alcohol-treated mice (92).

However, it is crucial to interpret these findings with caution. The majority of evidence comes from animal models, which cannot fully recapitulate the complexity of human IBD. Extrapolating these results directly to human patients is premature. Overall, while more clinical studies are needed to fully understand the therapeutic potential of melanoidins in IBD, their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and microbiota-modulating effects suggest that they may be a promising dietary intervention for alleviating the symptoms and reducing the risk of flare-ups in IBD patients.

5.2 IBS

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by chronic abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits-such as diarrhea, constipation, or mixed patterns-without overt inflammation or structural damage. Its pathophysiology involves disrupted gut motility, visceral hypersensitivity, and gut-brain axis dysfunction, often triggered by stress, diet, or gut microbiota imbalance.

Melanoidins may potentially alleviate IBS symptoms through multiple pathways. For instance, black garlic melanoidins have been shown to modulate gut microbiota and reduce systemic inflammation in obese mice (6). By promoting SCFA-producing bacteria, melanoidins could theoretically support normal gut motility and reduce visceral hypersensitivity, thereby improving bloating and abdominal pain. A study in humans indicated that melanoidin intake influences postprandial appetite-regulating peptides and gut-brain signaling molecules (4), which might indirectly relate to gut function and sensation; however, this study was not specifically designed in IBS patients and its direct relevance to core IBS symptoms remains to be established.

However, clinical evidence remains limited, with most data derived from animal or in vitro studies. Individual variations in microbiota and diet also limit generalizability. Moreover, excessive consumption of melanoidins-especially from certain sources-might stimulate harmful microbial metabolites, highlighting the need for further dose–response and safety studies.

6 Conclusions and perspectives

Melanoidins, widely present in heat-processed and fermented foods, are emerging as promising functional food components with diverse biological activities observed primarily in vitro and in animal models. Their resistance to host digestion and subsequent fermentation by gut microbiota suggests a potential mechanism to influence microbial composition and metabolism, particularly through the generation of SCFAs. Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated that melanoidins can exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and prebiotic properties, which may support gut barrier integrity and microbial homeostasis. These preliminary attributes suggest a potential role in the dietary management of gut-associated disorders such as IBD and IBS that warrants further investigation. However, it is premature to overstate their clinical potential, as the current understanding of melanoidin-microbiota interactions remain constrained by significant methodological challenges. Foremost among these is the lack of standardized methods for melanoidin extraction and characterization from complex food matrices, which leads to poorly defined test materials and hinders cross-study comparisons. Furthermore, the substantial variability in melanoidin structure-dependent on food origin and processing conditions-coupled with inter-individual differences in microbiota composition and complex metabolic pathways, poses considerable challenges for predicting consistent health outcomes in humans.

Therefore, future research must first prioritize overcoming these fundamental hurdles. The immediate path forward should focus on the development of standardized, reproducible protocols for the extraction and characterization of food-derived melanoidins to establish a reliable foundation for subsequent research. Building upon this, well-controlled dose–response studies in animal models are essential to establish causal relationships and define effective doses. Ultimately, these efforts must be translated into rigorous human trials, particularly randomized controlled trials, to validate the prebiotic and anti-inflammatory effects observed preclinically and to assess long-term safety and efficacy. Concurrently, investigating the synergistic effects of melanoidins within a whole-diet context, including their interactions with other dietary components like polyphenols and probiotics, will be crucial. Integrating these mechanistic and clinical insights will be essential to translate current findings into validated dietary strategies. Overall, while melanoidins represent a compelling target for future research into gut health, their application in functional foods and clinical nutrition awaits more robust evidence from human studies.

Author contributions

JC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XG: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. YH: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. GL: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1672681/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Wang, Y, Jian, C, Salonen, A, Dong, M, and Yang, Z. Designing healthier bread through the lens of the gut microbiota. Trends Food Sci Tech. (2023) 134:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2023.02.007

2. Cao, ZH, Green-Johnson, JM, Buckley, ND, and Lin, QY. Bioactivity of soy-based fermented foods: a review. Biotechnol Adv. (2019) 37:223–38. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.12.001

3. Ripper, B, Kaiser, CR, and Perrone, D. Use of Nmr techniques to investigate the changes on the chemical composition of coffee Melanoidins. J Food Compos Anal. (2020) 87:103399. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2019.103399

4. Walker, JM, Mennella, I, Ferracane, R, Tagliamonte, S, Holik, A-K, Hölz, K, et al. Melanoidins from coffee and bread differently influence energy intake: a randomized controlled trial of food intake and gut-brain Axis response. J Funct Foods. (2020) 72:104063. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2020.104063

5. Verzelloni, E, Tagliazucchi, D, and Conte, A. From balsamic to healthy: traditional balsamic vinegar Melanoidins inhibit lipid peroxidation during simulated gastric digestion of meat. Food Chem Toxicol. (2010) 48:2097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.05.010

6. Wu, J, Liu, Y, Dou, Z, Wu, T, Liu, R, Sui, W, et al. Black garlic Melanoidins prevent obesity, reduce serum Lps levels and modulate the gut microbiota composition in high-fat diet-induced obese C57bl/6j mice. Food Funct. (2020) 11:9585–98. doi: 10.1039/D0FO02379E

7. Gao, X, Zhao, X, Hu, F, Fu, J, Zhang, Z, Liu, Z, et al. The latest advances on soy sauce research in the past decade: emphasis on the advances in China. Food Res Int. (2023) 173:113407. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113407

8. Gao, X, Liu, E, Zhang, J, Yang, M, Chen, S, Liu, Z, et al. Effects of sonication during moromi fermentation on antioxidant activities of compounds in raw soy sauce. LWT. (2019) 116:108605. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108605

9. Yang, S, Fan, W, and Xu, Y. Melanoidins present in traditional fermented foods and beverages. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. (2022) 21:4164–88. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.13022

10. Rurián-Henares, JA, and Morales, FJ. Antimicrobial activity of Melanoidins against Escherichia Coli is mediated by a membrane-damage mechanism. J Agric Food Chem. (2008) 56:2357–62. doi: 10.1021/jf073300+

11. Xu, Q, Tao, W, and Ao, Z. Antioxidant activity of vinegar melanoidins. Food Chem. (2007) 102:841–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.06.013

12. Nguyen, TMT, Cho, EJ, Song, Y, Oh, CH, Funada, R, and Bae, HJ. Use of coffee flower as a novel resource for the production of bioactive compounds, Melanoidins, and bio-sugars. Food Chem. (2019) 299:125120. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125120

13. Diaz-Morales, N, Ortega-Heras, M, Diez-Mate, AM, Gonzalez-San Jose, ML, and Muniz, P. Antimicrobial properties and volatile profile of bread and biscuits melanoidins. Food Chem. (2022) 373:131648. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131648

14. Arimi, MM, Zhang, Y, Götz, G, Kiriamiti, K, and Geißen, S-U. Antimicrobial colorants in molasses distillery wastewater and their removal technologies. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. (2014) 87:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2013.11.002

15. Chen, H, Chen, T, Giudici, P, and Chen, F. Vinegar functions on health: constituents, sources, and formation mechanisms. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. (2016) 15:1124–38. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12228

16. Echavarría, AP, Pagán, J, and Ibarz, A. Melanoidins formed by Maillard reaction in food and their biological activity. Food Eng Rev. (2012) 4:203–23. doi: 10.1007/s12393-012-9057-9

17. Perez-Burillo, S, Rajakaruna, S, Pastoriza, S, Paliy, O, and Angel Rufian-Henares, J. Bioactivity of food melanoidins is mediated by gut microbiota. Food Chem. (2020) 316:126309. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.126309

18. Tagliazucchi, D, and Verzelloni, E. Relationship between the chemical composition and the biological activities of food melanoidins. Food Sci Biotechnol. (2014) 23:561–8. doi: 10.1007/s10068-014-0077-5

19. Zhang, Q, Chen, M, Emilia Coldea, T, Yang, H, and Zhao, H. Structure, chemical stability and antioxidant activity of Melanoidins extracted from dark beer by acetone precipitation and macroporous resin adsorption. Food Res Int. (2023) 164:112045. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112045

20. Yang, S, Fan, W, and Xu, Y. Melanoidins from Chinese distilled spent grain: content, preliminary structure, antioxidant, and ace-inhibitory activities in vitro. Foods. (2019) 8:516. doi: 10.3390/foods8100516

21. Zhang, L, Wu, JL, Xu, P, Guo, S, Zhou, T, and Li, N. Soy protein degradation drives diversity of amino-containing compounds via Bacillus subtilis natto fermentation. Food Chem. (2022) 388:133034. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133034

22. Chen, Y, Luo, W, Fu, M, Yu, Y, Wu, J, Xu, Y, et al. Effects of selected Bacillus strains on the biogenic amines, bioactive ingredients and antioxidant capacity of shuidouchi. Int J Food Microbiol. (2023) 388:110084. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2022.110084

23. Zhang, Z, He, S, Cao, X, Ye, Y, Yang, L, Wang, J, et al. Potential prebiotic activities of soybean peptides Maillard reaction products on modulating gut microbiota to alleviate aging-related disorders in D-galactose-induced Icr mice. J Funct Foods. (2020) 65:103729. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2019.103729

24. Mesías, M, and Delgado-Andrade, C. Melanoidins as a potential functional food ingredient. Curr Opin Food Sci. (2017) 14:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2017.01.007

25. Wang, H, Jenner, AM, Lee, CY, Shui, G, Tang, SY, Whiteman, M, et al. The identification of antioxidants in dark soy sauce. Free Radic Res. (2007) 41:479–88. doi: 10.1080/10715760601110871

26. Sharma, JK, Sihmar, M, Santal, AR, Prager, L, Carbonero, F, and Singh, NP. Barley Melanoidins: key dietary compounds with potential health benefits. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:8. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.708194

27. Zhang, X, Zhang, X, Wang, Z, Quan, B, Bai, X, Wu, Z, et al. Melanoidin-like carbohydrate-containing macromolecules from Shanxi aged vinegar exert Immunoenhancing effects on macrophage Raw264.7 cells. Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 264:130088. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130088

28. Helou, C, Jacolot, P, Niquet-Leridon, C, Gadonna-Widehem, P, and Tessier, FJ. Maillard reaction products in bread: a novel semi-quantitative method for evaluating Melanoidins in bread. Food Chem. (2016) 190:904–11. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.032

29. Rajakaruna, S, Pérez-Burillo, S, Kramer, DL, Rufián-Henares, JÁ, and Paliy, O. Dietary Melanoidins from biscuits and bread crust Alter the structure and short-chain fatty acid production of human gut microbiota. Microorganisms. (2022) 10:1268. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10071268

30. Aljahdali, N, Gadonna-Widehem, P, Anton, PM, and Carbonero, F. Gut microbiota modulation by dietary barley malt Melanoidins. Nutrients. (2020) 12:12. doi: 10.3390/nu12010241

31. Ercolini, D, and Fogliano, V. Food design to feed the human gut microbiota. J Agric Food Chem. (2018) 66:3754–8. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00456

32. Delgado-Andrade, C, and Morales, FJ. Unraveling the contribution of Melanoidins to the antioxidant activity of coffee brews. J Agric Food Chem. (2005) 53:1403–7. doi: 10.1021/jf048500p

33. Antonietti, S, Silva, AM, Simões, C, Almeida, D, Félix, LM, Papetti, A, et al. Chemical composition and potential biological activity of Melanoidins from instant soluble coffee and instant soluble barley: a comparative study. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:9. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.825584

34. Kimura, S, Tung, YC, Pan, MH, Su, NW, Lai, YJ, and Cheng, KC. Black garlic: a critical review of its production, bioactivity, and application. J Food Drug Anal. (2017) 25:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.11.003

35. Iriondo-DeHond, A, Rodríguez Casas, A, and del Castillo, MD. Interest of coffee Melanoidins as sustainable healthier food ingredients. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:8. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.730343

36. Hu, J, Bi, J, Wang, W, and Li, X. Comparison of characterization and composition of Melanoidins from three different dried apple slices. Food Chem. (2024) 455:139890. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.139890

37. Langner, E, Nunes, FM, Pożarowski, P, Kandefer-Szerszeń, M, Pierzynowski, SG, and Rzeski, W. Melanoidins isolated from heated potato Fiber (Potex) affect human Colon Cancer cells growth via modulation of cell cycle and proliferation regulatory proteins. Food Chem Toxicol. (2013) 57:246–55. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.03.042

38. Ghafoor, K, Kim, SO, Lee, DU, Seong, K, and Park, J. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on structure and colour of red ginseng (Panax Ginseng). J Sci Food Agric. (2012) 92:2975–82. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5710

39. Xia, T, Qiang, X, Geng, B, Zhang, X, Wang, Y, Li, S, et al. Changes in the phytochemical and bioactive compounds and the antioxidant properties of wolfberry during vinegar fermentation processes. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:15839. doi: 10.3390/ijms232415839

40. Wang, H, Qi, J, Han, D-Q, Xu, T, Liu, J-H, Qin, M-J, et al. Cause and control of Radix Ophiopogonis Browning during storage. Chin J Nat Med. (2015) 13:73–80. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(15)60010-3

41. Cao, G, Zhang, S, and Yang, Y. Progress on the melanoidins produced by the Maillard reaction of fermented food and traditional Chinese medicine. Food Health. (2024) 6:17. doi: 10.53388/FH2024017

42. Peña-Correa, RF, Wang, Z, Mesa, V, Ataç Mogol, B, Martínez-Galán, JP, and Fogliano, V. Digestion and gut-microbiota fermentation of cocoa melanoidins: an in vitro study. J Funct Foods. (2023) 109:105814. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105814

43. Coelho, C, Ribeiro, M, Cruz, AC, Domingues, MR, Coimbra, MA, Bunzel, M, et al. Nature of phenolic compounds in coffee melanoidins. J Agric Food Chem. (2014) 62:7843–53. doi: 10.1021/jf501510d

44. Delgado-Andrade, C, and Fogliano, V. Dietary advanced glycosylation end-products (Dages) and melanoidins formed through the Maillard reaction: physiological consequences of their intake. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. (2018) 9:271–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030117-012441

45. Carvalho, DO, Correia, E, Lopes, L, and Guido, LF. Further insights into the role of melanoidins on the antioxidant potential of barley malt. Food Chem. (2014) 160:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.074

46. Chandra, R, Bharagava, RN, and Rai, V. Melanoidins as major Colourant in sugarcane molasses based distillery effluent and its degradation. Bioresour Technol. (2008) 99:4648–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.09.057

47. Faixo, S, Gehin, N, Balayssac, S, Gilard, V, Mazeghrane, S, Haddad, M, et al. Current trends and advances in analytical techniques for the characterization and quantification of biologically recalcitrant organic species in sludge and wastewater: a review. Anal Chim Acta. (2021) 1152:338284. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2021.338284

48. Goulas, V, Nicolaou, D, Botsaris, G, and Barbouti, A. Straw wine Melanoidins as potential multifunctional agents: insight into antioxidant, antibacterial, and angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibition effects. Biomedicine. (2018) 6:6. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6030083

49. Oracz, J, Nebesny, E, and Zyzelewicz, D. Identification and quantification of free and bound phenolic compounds contained in the high-molecular weight melanoidin fractions derived from two different types of cocoa beans by UHPLC-DAD-ESI-HR-MS (N). Food Res Int. (2019) 115:135–49. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.08.028

50. Kang, OJ. Evaluation of Melanoidins formed from black garlic after different thermal processing steps. Prev Nutr Food Sci. (2016) 21:398–405. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2016.21.4.398

51. Langner, E, and Rzeski, W. Biological properties of melanoidins: a review. Int J Food Prop. (2013) 17:344–53. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2011.631253

52. Liu, J, Gan, J, Nirasawa, S, Zhou, Y, Xu, J, Zhu, S, et al. Cellular uptake and trans-enterocyte transport of phenolics bound to vinegar melanoidins. J Funct Foods. (2017) 37:632–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.08.009

53. Perez-Burillo, S, Mehta, T, Esteban-Munoz, A, Pastoriza, S, Paliy, O, and Angel Rufian-Henares, J. Effect of in vitro digestion-fermentation on green and roasted coffee bioactivity: the role of the gut microbiota. Food Chem. (2019) 279:252–9. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.137

54. Li, Y, Ji, X, Wu, H, Li, X, Zhang, H, and Tang, D. Mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine in modulating gut microbiota metabolites-mediated lipid metabolism. J Ethnopharmacol. (2021) 278:114207. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2021.114207

55. Balcazar-Zumaeta, CR, Castro-Alayo, EM, Cayo-Colca, IS, Idrogo-Vasquez, G, and Munoz-Astecker, LD. Metabolomics during the spontaneous fermentation in cocoa (Theobroma Cacao L.): an Exploraty review. Food Res Int. (2023) 163:112190. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112190

56. Kitchen, B, and Williamson, G. Melanoidins and (poly) phenols: an analytical paradox. Curr Opin Food Sci. (2024) 60:101217. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2024.101217

57. Wang, J, Zhang, N, Xia, T, Nie, Y, Zhang, X, Lang, F, et al. Melanoidins from Shanxi aged vinegar: characterization and behavior after in vitro simulated digestion and colonic fermentation. Food Chem. (2025) 464:141769. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2024.141769

58. Cooper, J, Kavanagh, J, Razmjou, A, Chen, V, and Leslie, G. Treatment and resource recovery options for first and second generation bioethanol Spentwash - a review. Chemosphere. (2020) 241:124975. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124975

59. Donohoe, DR, Garge, N, Zhang, X, Sun, W, O'Connell, TM, Bunger, MK, et al. The microbiome and butyrate regulate energy metabolism and autophagy in the mammalian Colon. Cell Metab. (2011) 13:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.018

60. Chen, T, Xie, L, Shen, M, Yu, Q, Chen, Y, and Xie, J. Recent advances in Astragalus polysaccharides: structural characterization, bioactivities and gut microbiota modulation effects. Trends Food Sci Technol. (2024) 153:104707. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104707

61. Tian, L, Andrews, C, Yan, Q, and Yang, JJ. Molecular regulation of calcium-sensing receptor (Casr)-mediated signaling. Chronic Dis Transl Med. (2024) 10:167–94. doi: 10.1002/cdt3.123

62. Kim, MH, Kang, SG, Park, JH, Yanagisawa, M, and Kim, CH. Short-chain fatty acids activate Gpr41 and Gpr43 on intestinal epithelial cells to promote inflammatory responses in mice. Gastroenterology. (2013) 145:396–406.e10. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.056

63. O'Riordan, KJ, Collins, MK, Moloney, GM, Knox, EG, Aburto, MR, Fulling, C, et al. Short chain fatty acids: microbial metabolites for gut-brain Axis Signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2022) 546:111572. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2022.111572

64. Cavaliere, G, Catapano, A, Trinchese, G, Cimmino, F, Penna, E, Pizzella, A, et al. Butyrate improves neuroinflammation and mitochondrial impairment in cerebral cortex and synaptic fraction in an animal model of diet-induced obesity. Antioxidants. (2022) 12:4. doi: 10.3390/antiox12010004

65. Ecklu-Mensah, G, Choo-Kang, C, Maseng, MG, Donato, S, Bovet, P, Viswanathan, B, et al. Gut microbiota and fecal short chain fatty acids differ with adiposity and country of origin: the Mets-microbiome study. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:5160. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40874-x

66. Morales, FJ, Somoza, V, and Fogliano, V. Physiological relevance of dietary Melanoidins. Amino Acids. (2012) 42:1097–109. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0774-1

67. Taglialegna, A. Keep calm with ammonia-producing microbiota. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2024) 22:2. doi: 10.1038/s41579-023-00996-x

68. Wang, P, Wu, PF, Wang, HJ, Liao, F, Wang, F, and Chen, JG. Gut microbiome-derived Ammonia modulates stress vulnerability in the host. Nat Metab. (2023) 5:1986–2001. doi: 10.1038/s42255-023-00909-5

69. Wang, Z, Zhao, Y, Wang, D, Zhang, X, Xia, M, Xia, T, et al. Exploring polymerisation of methylglyoxal with Nh(3) or alanine to analyse the formation of typical polymers in melanoidins. Food Chem. (2022) 394:133472. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133472

70. Pavez-Jara, JA, van Lier, JB, and de Kreuk, MK. Accumulating Ammoniacal nitrogen instead of Melanoidins determines the anaerobic digestibility of thermally hydrolyzed waste activated sludge. Chemosphere. (2023) 332:138896. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.138896

71. Matukas, M, Starkute, V, Zokaityte, E, Zokaityte, G, Klupsaite, D, Mockus, E, et al. Effect of different yeast strains on biogenic amines, volatile compounds and sensory profile of beer. Foods. (2022) 11:11. doi: 10.3390/foods11152317

72. Delgado-Ospina, J, Di Mattia, CD, Paparella, A, Mastrocola, D, Martuscelli, M, and Chaves-Lopez, C. Effect of fermentation, drying and roasting on biogenic amines and other biocompounds in Colombian Criollo cocoa beans and shells. Foods. (2020) 9:9. doi: 10.3390/foods9040520

73. Gao, X, Li, C, He, R, Zhang, Y, Wang, B, Zhang, Z-H, et al. Research advances on biogenic amines in traditional fermented foods: emphasis on formation mechanism, detection and control methods. Food Chem. (2023) 405:134911. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134911

74. Claes, L, Janssen, M, and De Vos, DE. Organocatalytic decarboxylation of amino acids as a route to bio-based amines and amides. ChemCatChem. (2019) 11:4297–306. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201900800

75. Jia, X, Jia, M, Gao, X, Li, X, Wang, M, Du, S, et al. Demonstration of safety characteristics and effects on gut microbiota of Lactobacillus Gasseri Hmv18. Food Sci Hum Well. (2024) 13:611–20. doi: 10.26599/fshw.2022.9250052

76. Swider, O, Roszko, ML, Wojcicki, M, and Szymczyk, K. Biogenic amines and free amino acids in traditional fermented vegetables-dietary risk evaluation. J Agric Food Chem. (2020) 68:856–68. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b05625

77. Smaniotto, A, Bertazzo, A, Comai, S, and Traldi, P. The role of peptides and proteins in Melanoidin formation. J Mass Spectrom. (2009) 44:410–8. doi: 10.1002/jms.1519

78. Wang, K, Tang, N, Bian, X, Geng, D, Chen, H, and Cheng, Y. Structural characteristics, chemical compositions and antioxidant activity of melanoidins during the traditional brewing of Monascus vinegar. LWT. (2024) 209:116760. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116760

79. Yan, T, Shi, L, Liu, T, Zhang, X, Yang, M, Peng, W, et al. Diet-rich in wheat bran modulates tryptophan metabolism and Ahr/Il-22 Signalling mediated metabolic health and gut Dysbacteriosis: a novel prebiotic-like activity of wheat bran. Food Res Int. (2023) 163:112179. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.112179

80. Fernandez-Cruz, E, Carrasco-Galan, F, Cerezo-Lopez, AB, Valero, E, Morcillo-Parra, MA, Beltran, G, et al. Occurrence of melatonin and Indolic compounds derived from L-tryptophan yeast metabolism in fermented wort and commercial beers. Food Chem. (2020) 331:127192. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.127192

81. Suzuki, N, and Philp, RP. Formation of melanoidins in the presence of H2s. Org Geochem. (1990) 15:361–6. doi: 10.1016/0146-6380(90)90162-S

82. Gui, DD, Luo, W, Yan, BJ, Ren, Z, Tang, ZH, Liu, LS, et al. Effects of gut microbiota on atherosclerosis through hydrogen sulfide. Eur J Pharmacol. (2021) 896:173916. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.173916

83. Donertas Ayaz, B, and Zubcevic, J. Gut microbiota and neuroinflammation in pathogenesis of hypertension: a potential role for hydrogen sulfide. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 153:104677. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104677

84. Faist, V, and Erbersdobler, HF. Metabolic transit and in vivo effects of Melanoidins and precursor compounds deriving from the Maillard reaction. Ann Nutr Metab. (2001) 45:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000046699

85. Younis, NK, Alfarttoosi, KH, Sanghvi, G, Roopashree, R, Kashyap, A, Krithiga, T, et al. The role of gut microbiota in modulating immune signaling pathways in autoimmune diseases. NeuroMolecular Med. (2025) 27:65. doi: 10.1007/s12017-025-08883-9

86. Fogliano, V, and Morales, FJ. Estimation of dietary intake of Melanoidins from coffee and bread. Food Funct. (2011) 2:117–23. doi: 10.1039/c0fo00156b

87. Song, X, Xue, L, Geng, X, Wu, J, Wu, T, and Zhang, M. Structural characteristics and immunomodulatory effects of Melanoidins from black garlic. Foods. (2023) 12:12. doi: 10.3390/foods12102004

88. Liu, R, Wu, Q, Xu, J, Gao, Y, Zhi, Z, Wu, T, et al. Isolation of Melanoidins from heat-moisture treated ginseng and its inhibitory effect on choline metabolism. J Funct Foods. (2023) 100:105370. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2022.105370

89. Song, Y, Chen, C, Wang, F, Zhang, Y, Pan, Z, and Zhang, R. Physicochemical properties and antioxidant activities of jujubes (Ziziphus jujuba mill.): effect of blackening process on different cultivars. Int J Food Prop. (2022) 25:1576–90. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2022.2093361

90. Silva, JP, Navegantes-Lima, KC, Oliveira, AL, Rodrigues, DV, Gaspar, SL, Monteiro, VV, et al. Protective mechanisms of butyrate on inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Des. (2018) 24:4154–66. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666181001153605

91. Rufián-Henares, JA, and Morales, FJ. Functional properties of melanoidins: in vitro antioxidant, antimicrobial and antihypertensive activities. Food Res Int. (2007) 40:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.05.002

92. Xia, T, Zhang, B, Li, S, Fang, B, Duan, W, Zhang, J, et al. Vinegar extract ameliorates alcohol-induced liver damage associated with the modulation of gut microbiota in mice. Food Funct. (2020) 11:2898–909. doi: 10.1039/C9FO03015H

93. Zhang, Y. Structural identification and preliminary study on antioxidant activity of soy sauce Melanoidins. Jiangsu University (2023). doi: 10.27170/d.cnki.gjsuu.2023.000892

94. Yang, S, Fan, W, Nie, Y, and Xu, Y. The formation and structural characteristics of Melanoidins from fermenting and distilled grains of Chinese liquor (baijiu). Food Chem. (2023) 410:135372. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.135372

95. Pan, Y. The study of extraction, purification and function of Melanoidins form cooked Lycium Barabarum. Tianjin University of Science and Technology (2022). doi: 10.27359/d.cnki.gtqgu.2022.001022

96. Huang, H, Zhao, L, Kong, X, Zhu, J, and Lu, J. Vinegar powder exerts immunomodulatory effects through alleviating immune system damage and protecting intestinal integrity and microbiota homeostasis. Food Biosci. (2025) 63:105687. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.105687

97. Wu, J, Zhou, X, Dou, Z, Wu, T, Liu, R, Sui, W, et al. Different molecular weight black garlic melanoidins alleviate high fat diet induced circadian intestinal microbes dysbiosis. J Agric Food Chem. (2021) 69:3069–81. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07723

98. He, S, Yu, M, Sun, H, Zhang, Z, Zhu, Y, Zhao, J, et al. Potential effects of dietary Maillard reaction products derived from 1 to 3 Kda soybean peptides on the aging Icr mice. Food Chem Toxicol. (2019) 125:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.12.045

99. Kamei, H, Koide, T, Hashimoto, Y, Kojima, T, Umeda, T, and Hasegawa, M. Tumor cell growth-inhibiting effect of melanoidins extracted from miso and soy sauce. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. (1997) 12:405–9. doi: 10.1089/cbr.1997.12.405

Keywords: melanoidins, gut microbiota, short-chain fatty acids, Maillard reaction, prebiotics

Citation: Chen J, Gao X, Hou Y and Liang G (2025) Dietary melanoidins as emerging functional components: interactions with gut microbiota and implications for nutritional modulation of intestinal health. Front. Nutr. 12:1672681. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1672681

Edited by:

Fernando M. Nunes, University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, PortugalCopyright © 2025 Chen, Gao, Hou and Liang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jialiang Chen, Y2hlbmNoZW4xNTk1QDE2My5jb20=; Guowei Liang, bGd3NzIxQDE2My5jb20=

Jialiang Chen

Jialiang Chen Xiaoyi Gao2

Xiaoyi Gao2 Guowei Liang

Guowei Liang