- 1Department of Fertility & Social Demography, International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India

- 2Department of Sciences (Mathematics), Indian Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

- 3Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, KAHER, Belgaum, Karnataka, India

Background: Stunting affects nearly one in three children under five in India. While socioeconomic, maternal, and environmental factors are well-established determinants, the role of household structure particularly children living with only their mother remains underexplored. Therefore, the present study aims to examine the association between family structure and stunting among children under 5 years of age in India. Specifically, the objective is to compare the risk of stunting among children living with their mothers only to those living with both parents and to identify the key factors contributing to any observed disparities.

Data and methods: This study analyzed data from 224,218 surviving children aged 0–59 months from the NFHS-5 (2019–21), which is a cross-sectional survey conducted across India and is nationally representative for all key indicators of women and child health. The main outcome of interest stunting was defined as height-for-age Z-score < −2 SD. Children were classified by living arrangement: with both parents or mother alone. Multivariable logistic regression models were sequentially adjusted for child, maternal, household, and community-level factors. Furthermore, Fairlie decomposition analysis quantified the contribution of observed characteristics to stunting disparities.

Results: A total of 1.35% of children lived with their mother alone, among whom stunting prevalence was significantly higher (39.8%) compared to those with both parents (35.43%). In unadjusted models, child with mother alone was associated with 21% higher odds of stunting (OR: 1.21; 95% CI: 1.12–1.30). However, this association gradually weakened after accounting for confounders in the fully adjusted model (OR: 1.07; 95% CI: 0.97–1.18). Fairlie decomposition (model III) revealed that 70.19% of the stunting gap was attributable to observed factors. Household wealth was the largest contributor (28.29%), followed by maternal height (24.23%) and social caste (13.01%), indicating that structural inequities, rather than the family structure per se, drive the observed disparity.

Conclusion: The elevated stunting risk among children living with mothers alone is not intrinsic to single-mother households but is largely associated by socioeconomic disadvantage, maternal undernutrition, and systemic inequities. Policies targeting poverty reduction, maternal health, and education are essential to address stunting in vulnerable family settings.

Introduction

Stunting, defined as impaired linear growth for age, is characterized by a height-for-age measurement that falls at least two standard deviations below the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards (1). This condition primarily results from inadequate dietary intake of energy and essential nutrients necessary to support optimal growth and development (2). Stunting serves as a key indicator of chronic undernutrition, affecting millions of children globally and posing a significant threat to their health and long-term well-being. Compared to their non-stunted peers, stunted children face an elevated risk of mortality and are more susceptible to life-threatening infectious diseases, including diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and measles (3). The condition is particularly prevalent among children exposed to recurrent infections, those residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged households, and those born to mothers who consumed inadequate diets before and during pregnancy (4). The long-term consequences of stunting extend beyond physical growth, encompassing impaired cognitive development, reduced educational achievement, and consequently diminished economic productivity in adulthood (5). Moreover, stunting is associated with an increased risk of overweight and non-communicable diseases later in life, thereby contributing to the dual burden of malnutrition (5).

Addressing malnutrition in all its forms is intrinsically linked to international human rights instruments that affirm the universal right to food. Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights explicitly recognizes the right to an adequate standard of living sufficient to ensure health and well-being, including access to adequate and nutritious food (6). In the recants estimate in 2024, 150.2 million children under the age of five (23.2%) were affected by stunting (7). In the context of India, there has been a significant drop in stunting in the last two decades (8). Stunting reduced from 51.9% in NFHS-1 to 34.1% in NFHS-5 still stunting is persistent within the population (9). Previous studies have highlighted multiple determinants of stunting, including poverty, maternal education, inadequate infant and young child feeding practices, poor sanitation, and recurrent infections (10, 11). However, the role of household structure, particularly the absence of one parent, has received far less attention in India.

In India, evolving family structures—shaped by demographic transition, modernization, and urbanization have introduced new complexities to the challenge of child undernutrition (12). Rising divorce rates (13), the rapid shift from traditional joint families to nuclear households driven by increasing literacy, economic transformation, and greater autonomy for women (12), and the growing prevalence of single-parent households (14, 15), collectively reflect profound changes in familial and social organization. These transformations mirror broader shifts in marriage and partnership dynamics across the country (16). Empirical evidence underscores this trend: Dommaraju (17) documents a marked decline in joint family living arrangements alongside a rise in one-person and nuclear households, fueled by factors such as higher educational attainment, employment in the formal sector, declining fertility, and rural-to-urban migration. More recently, Chakravorty et al. (18) emphasized that these evolving family structures are deeply intertwined with wider socioeconomic, cultural, and behavioral transformations in Indian society.

Children living with only their mother due to widowhood, divorce, or separation are at heightened risk of undernutrition. Single mothers, especially those facing economic hardship, often struggle to provide adequate nutrition due to limited financial resources, restricted healthcare access, and economic instability. Although children in single-mother households are more likely to be undernourished than those in two-parent families (19). Research has largely focused on broad determinants like household income and maternal education (20–22). While a few African studies have differentiated between types of single motherhood—such as widowhood, divorce, or non-marital childbearing in relation to child nutrition (23). This nuance is largely absent in the Indian context (24, 25). Consequently, the specific pathways through which diverse forms of single motherhood affect child nutritional outcomes in India remain underexplored (26). This knowledge gap limits the development of effective interventions to address the economic and social challenges faced by single-mother households. Financial hardship, social stigma, and the emotional burdens of single motherhood can adversely affect children’s nutritional status and overall health (27). Importantly, different forms of single motherhood may exert distinct influences on child nutrition: unmarried mothers often lack spousal financial support, heightening economic insecurity, while divorced or widowed mothers may experience greater psychological stress—both pathways potentially increasing the risk of child stunting (14). Addressing these disparities aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 2 (zero hunger, food security, and improved nutrition) and Goal 3 (healthy lives and well-being for all). This study investigates the association between single motherhood and child stunting in India and decomposes the disparity in stunting outcomes between children living with their mother alone and those living with both parents, aiming to elucidate the unique challenges faced by single-mother households. This study aims to inform evidence-based policies and targeted interventions that improve child health outcomes and reduce the burden of undernutrition among this vulnerable population.

Data and methods

This study utilizes data from the fifth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), conducted in 2019–21 across all states and union territories in India. NFHS-5 is a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey that collects extensive information on population health, fertility, child nutrition, mortality, family planning and maternal and child healthcare utilization. The analysis is restricted to children aged 0–59 months for whom complete anthropometric, household, and maternal information was available.

Figure 1 illustrates the sample selection process of the analytical sample from the total pool of children aged 0–59 months available in the NFHS dataset (N = 232,920). The first stage excluded children who were not alive at the time of survey. A total of 8,702 children (3.74%) were deceased and therefore not included in further analysis. The remaining 224,218 children (96.26%) were eligible for analysis. Among the surviving children, classification was done based on household composition. Children were categorized as either living with both parents or with their mother alone, based on co-residence information. The majority of children (N = 221,189; 98.65%) were living with both parents. Only a small fraction (N = 3,029; 1.35%) were living with their mother alone.

Variable description

The primary outcome variable is stunting, defined as a child having a height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) less than −2 standard deviations from the WHO reference population. The HAZ scores were pre-calculated in the NFHS dataset using WHO child growth standards. A binary variable was created to distinguish between stunted (HAZ < −2) and non-stunted children (HAZ ≥ −2).

The main explanatory variable is child’s living arrangement, categorized as:

1. Child living with both parents (reference group), and

2. Child living with mother only.

To account for potential confounding factors, a wide range of covariates were included, grouped into child, maternal, household, and community-level characteristics: Child-level variables include sex of the child, age in months (categorized in 15-month intervals), birth order, size at birth (mother’s perception), and birth weight (classified as low or normal). Maternal characteristics consist of age at childbirth, education level, body mass index (BMI), height, age at first birth, number of antenatal care (ANC) visits, place of delivery (institutional or non-institutional), and pregnancy wantedness. Household and community factors encompasses the wealth index (based on household assets), household size, caste group (SC/ST, OBC, others), religion (Hindu, Muslim, Christian, others), place of residence (urban/rural), region (North, South, East, West, Central, Northeast), sex of the household head, distance to healthcare facility, exposure to mass media, and family planning messages.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed to present the background characteristics of the sample by living arrangement and their association with stunting status. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to assess the significance of associations.

To assess the association between living arrangement and risk of stunting, a series of logistic regression models were estimated. Model 1 includes unadjusted odds ratios (UOR). Model 2 adjusts for child-level characteristics. Model 3 includes child and maternal characteristics. Model 4 is the full model adjusted for child, maternal, household, and community characteristics.

The binary logistic is usually put into a more compact form as follows:

Where, are regression coefficients indicating the relative effect of a particular explanatory variable on outcome. The coefficients change as per the context in the analysis.

In order to quantify the contribution of observed differences in characteristics to the gap in stunting between children living with both parents and those living with their mother only, a Fairlie decomposition technique was applied. This non-linear decomposition method is appropriate for binary outcomes and extends the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition to logistic regression frameworks. The method estimates the proportion of the observed difference in stunting that can be explained by group differences in the distribution of explanatory variables. Three decomposition models were applied:

1. Model with child characteristics only

2. Model including child and maternal characteristics

3. Full model including child, maternal, household, and community-level characteristics.

Mathematically, the Fairlie decomposition for two groups A and B can be expressed as:

Where denotes the average predicted probability of stunting in group j, X is a vector of covariates, are coefficient estimates from the pooled logit model, and F (·) is the cumulative logistic function. All the analysis has been done with STATA 16.0 version and also used weight for all the analysis.

Results

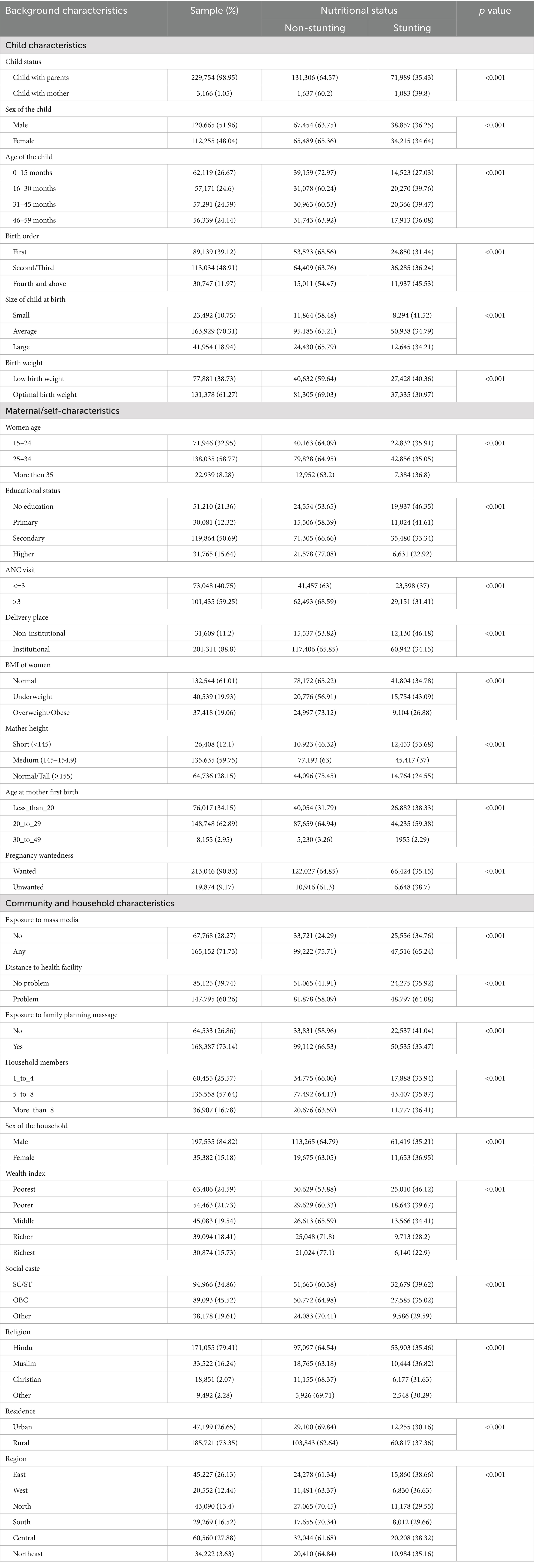

Table 1 shows the distribution of background characteristics and the prevalence of stunting among under-five children by living arrangement and other covariates.

Table 1. Background characteristics and stunting prevalence among under-five children by household structure, India (NFHS-5, 2019–21).

Child characteristics

In the analytic sample (N = 232,920; children living with both parents = 229,754, 98.95%; children living with mother only = 3,166, 1.05%), the overall prevalence of stunting was higher among children living with their mother only (39.8%) than among those living with both parents (35.43%; χ2, p < 0.001).

By sex, 36.25% of males and 34.64% of females were stunted (p < 0.001). Stunting varied with child age: prevalence was lowest in the youngest group (0–15 months, 27.03%) and highest for children aged 16–45 months (≈39.5% for 16–30 and 31–45 months). Children of higher birth order (≥4) showed higher stunting (45.53%) compared with firstborns (31.44%; p < 0.001). Children perceived as small at birth had higher stunting (41.52%) than those perceived average or large (p < 0.001), and low birth weight children had greater stunting (40.36%) than children with optimal birth weight (30.97%; p < 0.001).

Maternal / self-characteristics

Stunting prevalence varied substantially across maternal characteristics. By maternal age, children of mothers aged 15–24 and 25–34 had similar stunting prevalence (~35–36%), while those of mothers ≥35 years showed 36.8% stunting (p < 0.001). Maternal education showed a clear gradient: children of mothers with no education experienced the highest stunting (46.35%), compared with 33.34% for secondary and 22.92% for higher education (p < 0.001). Children of underweight mothers (BMI < 18.5) had higher stunting (43.09%) than those of normal (34.78%) or overweight mothers (26.88%; p < 0.001). Short maternal stature was strongly associated with child stunting: mothers <145 cm had 53.68% of children stunted versus 24.55% among mothers ≥155 cm (p < 0.001).

Community and household characteristics

Community and household context were also strongly associated with stunting. Children in poorest households had stunting of 46.12% compared with 22.9% in the richest quintile (p < 0.001). Children in rural areas had higher stunting (37.36%) than urban children (30.16%; p < 0.001). Exposure to mass media, distance to health facility, exposure to family planning massage, household size, caste and region showed significant bivariate associations with stunting (all p < 0.001). Regional differences were notable: Central and Eastern regions had higher stunting (~38–39%), while North and South showed lower prevalence (~29–30%; p < 0.001).

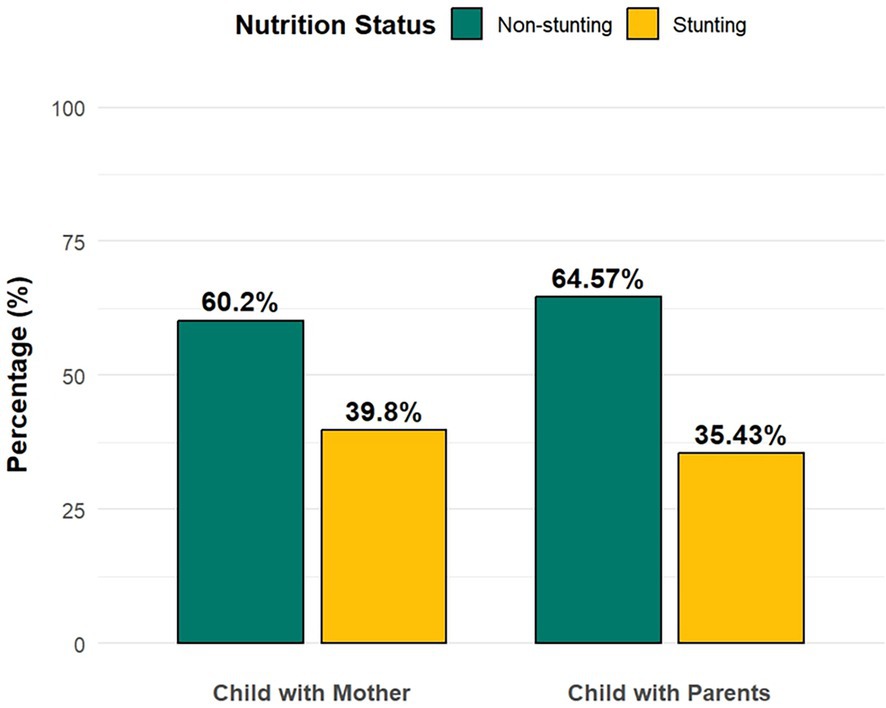

Figure 2 illustrates the prevalence of stunting among under-five children by living arrangement. The figure clearly shows that children living with their mother only experience a higher prevalence of stunting (39.8%) compared with those living with both parents (35.43%). Conversely, the proportion of non-stunted children is lower among those living with mother only (60.2%) compared to their counterparts living with both parents (64.57%). This pattern indicates a measurable nutritional disadvantage among children residing with their mother alone.

Figure 2. Prevalence of stunting among children living with mother only versus those living with both parents. Comparison of stunting and non-stunting percentages between children living with both parents and those living with mother only. Weighted percentages based on NFHS data.

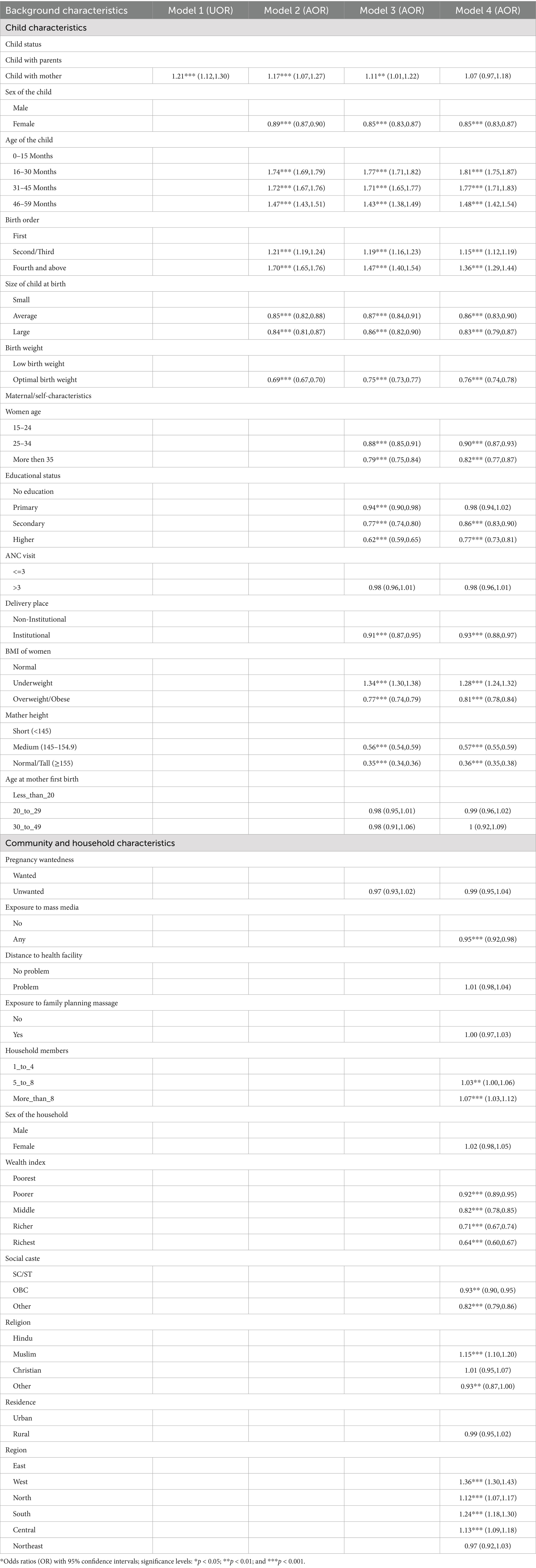

Table 2 presents the logistic regression estimates of the association between child living arrangement and stunting among under-five children in India across four nested models. In the unadjusted model (Model 1), children living with their mothers only had 21% higher odds of being stunted compared to those living with both parents (UOR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.12–1.30; p < 0.001). After adjusting for child-level characteristics, including age, sex, and birth order (Model 2), the association remained statistically significant but slightly attenuated (AOR = 1.17; 95% CI: 1.07–1.27; p < 0.001). With the inclusion of maternal characteristics such as education, body mass index (BMI), height, antenatal care visits, and place of delivery (Model 3), the association was further reduced but continued to be statistically significant (AOR = 1.11; 95% CI: 1.01–1.22; p < 0.05). However, in the fully adjusted model (Model 4), which incorporated household and community-level variables—such as wealth index, caste, religion, residence, region, household size, exposure to mass media, and accessibility to health facilities—the association between living with mother alone and stunting became statistically non-significant (AOR = 1.07; 95% CI: 0.97–1.18; p > 0.05). This finding indicates that the initial association between living arrangement and stunting is largely explained by socioeconomic and contextual factors rather than family structure itself.

Table 2. Logistic regression estimates of the association between living with mother alone and stunting among under-five children in India.

In the fully adjusted model, several covariates were found to be significantly associated with stunting. Female children were less likely to be stunted compared to male children (AOR = 0.85; 95% CI: 0.83–0.87). The risk of stunting increased consistently with child’s age, with children aged 16–30 months (AOR = 1.81; 95% CI: 1.75–1.87), 31–45 months (AOR = 1.77; 95% CI: 1.71–1.83), and 46–59 months (AOR = 1.48; 95% CI: 1.42–1.54) showing significantly higher odds of being stunted compared to those aged 0–15 months. Higher birth order was also associated with increased risk—second or third order (AOR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.12–1.19) and fourth or higher order (AOR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.29–1.44). Children with an average (AOR = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.83–0.90) or large size at birth (AOR = 0.83; 95% CI: 0.79–0.87) and those with optimal birth weight (AOR = 0.76; 95% CI: 0.74–0.78) were significantly less likely to be stunted than children of small size or low birth weight.

Regarding maternal characteristics, the results demonstrated strong protective effects of maternal education. Children of mothers with secondary (AOR = 0.86; 95% CI: 0.83–0.90) and higher education (AOR = 0.77; 95% CI: 0.73–0.81) were considerably less likely to be stunted compared with those whose mothers had no education. Maternal nutritional status also emerged as a key predictor: children of underweight mothers were more likely to be stunted (AOR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.24–1.32), while those of overweight or obese mothers had reduced odds (AOR = 0.81; 95% CI: 0.78–0.84). Maternal height was inversely associated with stunting; children of mothers with medium height (145–154.9 cm) had lower odds (AOR = 0.57; 95% CI: 0.55–0.59), and those of tall mothers (≥ 155 cm) had the lowest odds (AOR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.35–0.38). Furthermore, institutional delivery was significantly protective against stunting (AOR = 0.93; 95% CI: 0.88–0.97).

At the household and community level, the odds of stunting were slightly higher among children from larger households, with 5–8 members (AOR = 1.03; 95% CI: 1.00–1.06) and more than 8 members (AOR = 1.07; 95% CI: 1.03–1.12) compared to those from smaller households. A distinct socioeconomic gradient was observed across the wealth index, with decreasing odds of stunting among children from richer households: poorer (AOR = 0.92; 95% CI: 0.89–0.95), middle (AOR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.78–0.85), richer (AOR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.67–0.74), and richest (AOR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.60–0.67) compared with the poorest households. Caste-based differences were also evident, as children from “Other” caste groups were less likely to be stunted than those belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (AOR = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.79–0.86). By religion, Muslim children had slightly higher odds of stunting than Hindu children (AOR = 1.15; 95% CI: 1.10–1.20). Regional disparities persisted even after full adjustment, with children from the Central (AOR = 1.13; 95% CI: 1.09–1.18), Western (AOR = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.30–1.43), Northern (AOR = 1.12; 95% CI: 1.07–1.17), and Southern (AOR = 1.24; 95% CI: 1.18–1.30) regions exhibiting higher odds of stunting compared to those from the Eastern region.

Table 3 presents the Fairlie decomposition results explaining the gap in stunting prevalence between children living with both parents and those living with their mothers only. The decomposition sequentially includes child, maternal, and household-level characteristics to identify the major factors contributing to the observed difference in stunting between the two groups.

Table 3. Fairlie decomposition of the gap in stunting prevalence between children living with both parents and those living with mother only in India.

In Model I, which included only child characteristics, approximately 21.09% of the observed difference in stunting was explained by the included variables, while 78.91% remained unexplained. Among child-level factors, the age of the child emerged as the dominant contributor, accounting for nearly all of the explained portion (coefficient = −0.0094; ≈99.9% contribution). This suggests that differences in age composition between the two groups substantially drive the observed stunting gap. Other child-level variables such as sex, birth order, size at birth, and birth weight made smaller notable contributions.

In Model II, which incorporated both child and maternal characteristics, the proportion of the stunting gap explained increased markedly to 55.12%, with the unexplained component declining to 44.88%. The inclusion of maternal variables significantly enhanced the model’s explanatory power. Among these, maternal height and maternal education emerged as the most influential contributors. Maternal height had a large negative coefficient (−0.00695), explaining approximately 25.6% of the gap, while maternal education contributed 22.3%. These findings indicate that disparities in maternal nutritional status and educational attainment are key mediators of the difference in stunting between children living with both parents and those living with their mothers only. Maternal BMI and place of delivery also contributed modestly to explaining the gap, although their effects were smaller in magnitude.

In Model III, which additionally accounted for household and community-level characteristics, the explained share further increased to 70.19%, leaving 29.81% of the gap unexplained. The inclusion of socioeconomic and contextual variables substantially improved the explanatory capacity of the model. Among these, household wealth index (coefficient = −0.0098; contribution = 28.3%) and social caste (coefficient = −0.0045; contribution = 13.0%) were the strongest contributors, reflecting the central role of socioeconomic inequality in driving nutritional disparities. Other contextual factors, such as region (−16.4%) and religion (−4.9%), also contributed to the explained portion, while exposure to mass media and household size showed relatively minor effects.

Discussion

This study examined the association between living arrangements—specifically, whether a child lives with both parents or only with the mother—and the risk of stunting among children under five in India, using nationally representative data from the fifth round of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5, 2019–21). The analysis included 224,218 surviving children aged 0–59 months, of whom 1.35% lived with their mother alone. The primary outcome variable was stunting, defined as a height-for-age Z-score below −2 standard deviations (SD) according to WHO growth standards. Descriptive statistics, logistic regression models (both unadjusted and sequentially adjusted for child-maternal-household, and community-level factors), and Fairlie decomposition analysis were employed to quantify the contribution of various factors to the observed disparities. The key finding revealed that children living with their mother alone had a higher prevalence of stunting (39.8%) compared to those living with both parents (35.43%). However, this association became statistically non-significant after adjusting for socioeconomic and demographic covariates in the fully adjusted model.

Previous studies have shown that single mothers often experience economic and social disadvantages, which increase the risk of undernutrition among their children (14, 28, 29) Our finding from the logistic regression models revealed a progressive attenuation of the association between living with mother alone and stunting. In the unadjusted model, children in mother-only households had 21% higher odds of being stunted. After adjusting for child-level characteristics such as age, sex, birth order, size at birth, and birth weight, the odds ratio decreased slightly to 17%, indicating that these early-life biological and demographic factors partially accounted for the disparity. Further adjustment for maternal characteristics—including education, BMI, height, antenatal care, and delivery place—reduced the odds ratio to 11%, suggesting that maternal health and human capital play a substantial mediating role. However, in the fully adjusted model, which included household wealth, caste, religion, region, and other contextual variables, the association was no longer statistically significant 7%. This indicates that the elevated risk of stunting among children in single-mother households is largely explained by their disadvantaged socioeconomic and structural circumstances rather than the absence of the father per se. These findings align with prior research showing that household poverty, maternal undernutrition, and low educational attainment are stronger predictors of child stunting than family structure alone Factors associated with child stunting, wasting, and underweight in 35 low-and middle-income countries (30, 31). For example, evidence from 137 developing countries showed that maternal undernutrition and infection, adolescent motherhood, short birth intervals, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and child undernutrition and infection—rather than single parenthood—were the main determinants of poor child growth outcomes (10). Similarly, evidence from Uganda Bangladesh suggests that maternal education and household wealth mediate much of the nutritional disadvantage faced by marginalized children (32, 33).

The Fairlie decomposition analysis further illuminated the mechanisms underlying the stunting gap between the two groups. When only child-level characteristics were considered, they explained 21.09% of the disparity, with child age being the dominant contributor This finding aligns with global evidence highlighting a critical window—from conception to the first 2 years of life (0–23 months)—within which nearly 70% of stunting occurs. Growth deficits tend to persist until the age of five, primarily due to ongoing exposure to modifiable risk factors related to nutrition, infections, and psychosocial care (34). However, once maternal characteristics were introduced, the explained portion of the gap nearly tripled to 55.12%, underscoring the pivotal role of maternal factors. Notably, maternal height contributed −25.56%, indicating that short maternal height is strongly associated with increased risk of child stunting because it reflects a mother’s own early-life undernutrition and infections, which limit her skeletal growth. Biologically, shorter mothers are more likely to experience intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery, and smaller birth size of infants. These disadvantages at birth persist into early childhood, raising the likelihood of stunting (35). Maternal education also played a major role (−22.27%), reinforcing the protective effect of women’s schooling on child nutrition, this finding aligns with existing evidence that educated mothers are better equipped with knowledge of appropriate feeding, healthcare-seeking, and hygiene practices, which translate into improved child growth outcomes. Moreover, schooling enhances women’s autonomy and decision-making capacity, allowing them to allocate household resources more effectively toward nutrition and health. Therefore, strengthening female education not only benefits women themselves but also has intergenerational advantages by reducing the risk of stunting among their children (36, 37). The negative contributions suggest that single-mother households are disadvantaged in these key maternal attributes, thereby driving much of the observed stunting gap.

In the final decomposition model, which included household and community-level variables, 70.19% of the stunting gap was explained, highlighting the overwhelming influence of structural and socioeconomic factors. The wealth index emerged as the single largest contributor (28.29%), underscoring the central role of household economic status in shaping child nutritional outcomes. Children from poorer households face multiple disadvantages, including inadequate access to diverse diets, poor living and sanitation conditions, and limited healthcare utilization, higher disease burden all of which heighten their risk of stunting. This finding highlights the need for poverty alleviation strategies and equitable access to health and nutrition services as critical interventions to reduce child undernutrition that collectively impair linear growth (33, 38). Social caste also contributed significantly (13.01%), reflecting persistent inequities rooted in India’s social hierarchy, children from Scheduled Castes and Tribes experience overlapping disadvantages of poverty, poor living conditions, limited education, and restricted access to health services, all of which heighten their risk of stunting (39, 40). Geographic variation, captured by region (−16.39%), further emphasized the role of place-based disparities, with Central and Eastern regions bearing a higher burden These states are marked by entrenched poverty, low maternal education, poor sanitation, high fertility, and weaker health infrastructure, which together sustain high levels of stunting (41). Interestingly, while maternal height remained a strong contributor (24.23%), its effect was now positive, suggesting that even after accounting for wealth and caste, the biological disadvantage associated with short maternal stature continues to exert a direct influence on child growth. The unexplained portion of the gap declined from 78.91% in the first model to 29.81% in the full model, indicating that observed socioeconomic and demographic factors account for the majority of the disparity. This is consistent with studies showing that structural inequalities—not individual or familial deficits—are the root causes of child undernutrition (42, 43).

Policy implications

This study reveals that the higher stunting risk among children in mother-only households in India is not due to family structure itself, but to deep-seated structural inequities particularly poverty, maternal undernutrition, and caste-based disadvantage. This demands a shift in policy thinking: existing nutrition programs like POSHAN Abhiyaan must move beyond universal delivery and adopt equity-focused targeting (44). Currently, POSHAN Abhiyaan and ICDS provide supplementary nutrition, growth monitoring, and counseling, but they rarely identify or prioritize single-mother households a group often invisible in administrative data (45). To improve outcomes, Anganwadi workers should be trained to screen for household composition during registration and link single mothers to integrated support: conditional cash transfers (e.g., Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana), maternal nutrition supplements, and mental health services (46).

Moreover, social protection must address root causes: expand widow pensions, ensure access to property rights, and strengthen childcare support to enable livelihood participation. Given that maternal height a marker of intergenerational deprivation—explains 24% of the gap, investments must begin earlier: adolescent nutrition programs (e.g., Kishori Shakti Yojana) should be intensified in high-stunting regions (47). Critically, policies must avoid stigmatizing single mothers as “deficient.” Instead, frame support as correcting systemic exclusion—not fixing families.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study is its use of nationally representative, high-quality data from NFHS-5, enabling robust estimation of stunting disparities among under-five children in India. The large sample size (n = 224,218) allowed for precise analysis of a relatively small but vulnerable group—children living with mothers alone (1.35%)—while comprehensive covariates enabled stepwise adjustment across multiple levels. The application of Fairlie decomposition provided unique insights into the drivers of inequality, revealing how structural factors like wealth, caste, and maternal height explain 70.19% of the stunting gap. However, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and unmeasured factors—such as paternal absence due to migration versus widowhood, household food insecurity, or maternal mental health—may influence results but were not captured. Social desirability bias may also lead to underreporting of single-mother households. Despite these limitations, findings offer critical evidence for addressing structural inequities in child nutrition. Future research should employ alternative methodologies, such as trend analysis using data from the last five rounds of the NFHS, to better capture the temporal dynamics of child undernutrition in the context of single motherhood. It should also examine gender-based nutritional disparities among children and distinguish between widowed, divorced, and separated mothers to assess how these different circumstances influence child undernutrition outcomes, including stunting, wasting, and underweight.

Conclusion

The higher prevalence of stunting among under-five children living with their mother alone compared to those with both parents is not driven by single factor, but by the deep-rooted socioeconomic and structural disadvantages these households face. Regression analysis reveals that even after accounting for child, maternal and household characteristics stunting remains higher among children living with only their mother. The Fairlie decomposition confirms this: 70.19% of the stunting gap is explained by observable inequities, with household wealth (28.29%) and maternal height (24.23%) being the most powerful contributors. This depicts that poverty and maternal height are the true drivers of stunting in this vulnerable group. Children in mother-only households are more likely to belong to poorer, marginalized communities, have undernourished and less-educated mothers, and lack access to quality healthcare and sanitation. Therefore, policies targeting stunting must move beyond a narrow focus on family composition and instead address systemic inequities. Strengthening social protection programs, improving access to education and livelihoods for single mothers, and enhancing maternal and child nutrition services in disadvantaged regions are critical steps toward reducing stunting in India (48).

Data availability statement

This study is based on secondary analysis of anonymized, publicly available data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21, conducted by the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India, with technical assistance from ICF, under the stewardship of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The survey protocol was approved by the IIPS Institutional Review Board (IRB) in accordance with international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Ethics statement

This study is based on secondary analysis of anonymized, publicly available data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21, conducted by the International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai, India, with technical assistance from ICF, under the stewardship of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The survey protocol was approved by the IIPS Institutional Review Board (IRB) in accordance with international ethical standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, and personal identifiers were removed to ensure confidentiality. As this research involved no direct contact with human subjects and used only de-identified secondary data, additional ethical approval was not required. The dataset is accessible to registered users at: https://www.dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. All analyses were conducted in compliance with data use guidelines, and ethical integrity was maintained throughout the research process. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. MS: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

NFHS-5, National Family Health Survey; SD, standard deviations; WHO, World Health Organization; HAZ, height-for-age Z-score; ANC, antenatal care; SC/ST, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes; OBC, Other Backward Classes; AOR/UOR, Unadjusted odds ratio/adjusted odds ratio.

References

1. Thurstans, S, Sessions, N, Dolan, C, Sadler, K, Cichon, B, Isanaka, S, et al. The relationship between wasting and stunting in young children: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. (2022) 18:e13246. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13246

2. Yani, DI, Rahayuwati, L, Sari, CWM, Komariah, M, and Fauziah, SR. Family household characteristics and stunting: an update scoping review. Nutrients. (2023) 15:233. doi: 10.3390/nu15010233

3. Madewell, ZJ, Keita, AM, Das, PM-G, Mehta, A, Akelo, V, Oluoch, OB, et al. Contribution of malnutrition to infant and child deaths in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. BMJ Glob Health. (2024) 9:e017262. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-017262

4. Saleh, A, Syahrul, S, Hadju, V, Andriani, I, and Restika, I. Role of maternal in preventing stunting: a systematic review. Gac Sanit. (2021) 35:S576–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2021.10.087

5. De Sanctis, V, Soliman, A, Alaaraj, N, Ahmed, S, Alyafei, F, and Hamed, N. Early and Long-term Consequences of Nutritional Stunting: From Childhood to Adulthood: Early and Long-term Consequences of Nutritional Stunting. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis. (2021) 92:11346. doi: 10.23750/abm.v92i1.11346

6. Franco, AMS. Article 25.2: The right to an adequate standard of living – The right to food. In H. Cantú Rivera, editor. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: A Commentary. Brill. 617–645. doi: 10.1163/9789004365148_028

7. WHO. Joint child malnutrition estimates (JME) (UNICEF-WHO-WB). (2024). Available online at: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/joint-child-malnutrition-estimates-unicef-who-wb?utm (Accessed on August 27, 2025)

8. Iips, I. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5): 2019–21 India. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) (2021).

9. Chaudhuri, S, Kumar, Y, Nirupama, A, and Agiwal, V. Examining the prevalence and patterns of malnutrition among children aged 0–3 in India: comparative insights from NFHS-1 to NFHS-5. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. (2023) 24:101450. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2023.101450

10. Danaei, G, Andrews, KG, Sudfeld, CR, Fink, G, McCoy, DC, Peet, E, et al. Risk factors for childhood stunting in 137 developing countries: a comparative risk assessment analysis at global, regional, and country levels. PLoS Med. (2016) 13:e1002164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002164

11. Vilcins, D, Sly, PD, and Jagals, P. Environmental risk factors associated with child stunting: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Glob Health. (2018) 84:551. doi: 10.29024/aogh.2361

12. Dey, T, and Goli, S. Examining the role of modernization and urbanization in family changes in India: evidence from panel data analyses. J Fam Hist. (2025):03631990251376548. doi: 10.1177/03631990251376548

13. Thadathil, A, and Sriram, S. Divorce, families and adolescents in India: a review of research. J Divorce Remarriage. (2020) 61:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10502556.2019.1586226

14. Chileshe, V, and Kamiya, Y. The association between single motherhood and child undernutrition in Zambia: analysis of the 2007, 2013-14 and 2018 demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. (2025) 25:1439. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22651-1

15. Khusaini, M, and Finuliyah, F. Missing pieces: the stunting challenges by single mothers in Indonesia. Widyakala Jl: J Pembangunan Jaya University. (2025) 12:31. doi: 10.36262/widyakala.v12i1.1142

16. Allendorf, K, and Pandian, RK. The decline of arranged marriage? Marital change and continuity in India. Popul Dev Rev. (2016) 42:435–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2016.00149.x

17. Dommaraju, P. One-person households in India. Demogr Res. (2015) 32:1239–66. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2015.32.45

18. Chakravorty, S, Goli, S, and James, KS. Family demography in India: emerging patterns and its challenges. SAGE Open. (2021) 11:21582440211008178. doi: 10.1177/21582440211008178

19. Amadu, I, Seidu, A-A, Duku, E, Okyere, J, Hagan, JE Jr, Hormenu, T, et al. The joint effect of maternal marital status and type of household cooking fuel on child nutritional status in sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of cross-sectional surveys on children from 31 countries. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1541. doi: 10.3390/nu13051541

20. Parida, J, Bagepally, BS, Patra, PK, Pati, S, Kaur, H, and Acharya, SK. Prevalence and associated factors of undernutrition among adolescents in India: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. (2025) 25:819. doi: 10.1186/s12889-025-22054-2

21. Varghese, JS, Gupta, A, Mehta, R, Stein, AD, and Patel, SA. Changes in child undernutrition and overweight in India from 2006 to 2021: an ecological analysis of 36 states. Glob Health Sci Pract. (2022) 10:e2100569. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-21-00569

22. Wali, N, Agho, K, and Renzaho, AM. Hidden hunger and child undernutrition in South Asia: a meta-ethnographic systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. (2022) 31:713–39. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.202212_31(4).0014

23. Nkhoma, B, Ng’ambi, WF, Chipimo, PJ, and Zambwe, M. Determinants of stunting among children < 5 years of age: Evidence from 2018-2019 Zambia Demographic and Health Survey. Public and Global Healt. (2021) doi: 10.1101/2021.05.19.21257389

24. Kumar, P, Chauhan, S, Patel, R, Srivastava, S, and Bansod, DW. Prevalence and factors associated with triple burden of malnutrition among mother-child pairs in India: a study based on National Family Health Survey 2015–16. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:391. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10411-w

25. Mondal, S, and Pradhan, MR. Trends, patterns and determinants of family structure in India: a perspective of three decades. Marriage Fam Rev. (2025) 61:185–225. doi: 10.1080/01494929.2024.2427150

26. Odimegwu, CO, Mutanda, N, and Mbanefo, CM. Correlates of single motherhood in four sub-SaharanAfrican countries. J Comp Fam Stud. (2017) 48:313–28. doi: 10.3138/jcfs.48.4.313

27. He, J, and Wang, J. When does it matter? The effect of three-generational household arrangement on children’s well-being across developmental stages. Child Indic Res. (2021) 14:2471–93. doi: 10.1007/s12187-021-09857-6

28. Scharte, M, and Bolte, GGME Study Group. Increased health risks of children with single mothers: the impact of socio-economic and environmental factors. Eur J Pub Health. (2013) 23:469–75. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks062

29. Van de Walle, D. Lasting welfare effects of widowhood in Mali. World Dev. (2013) 51:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.005

30. Li, Z, Kim, R, Vollmer, S, and Subramanian, S. Factors associated with child stunting, wasting, and underweight in 35 low-and middle-income countries. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e203386. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3386

31. Muche, A, Gezie, LD, Baraki, AG, and Amsalu, ET. Predictors of stunting among children age 6–59 months in Ethiopia using Bayesian multi-level analysis. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:3759. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82755-7

32. Anwar, S, Nasreen, S, Batool, Z, and Husain, Z. Maternal education and child nutritional status in Bangladesh: evidence from demographic and health survey data. Pak J Life Soc Sci. (2013) 11:77–84.

33. Hong, R, Banta, JE, and Betancourt, JA. Relationship between household wealth inequality and chronic childhood under-nutrition in Bangladesh. Int J Equity Health. (2006) 5:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-5-15

34. Leroy, JL, Ruel, M, Habicht, J-P, and Frongillo, EA. Linear growth deficit continues to accumulate beyond the first 1000 days in low-and middle-income countries: global evidence from 51 national surveys. J Nutr. (2014) 144:1460–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.191981

35. Karlsson, O, Kim, R, and Bogin, B. Maternal height-standardized prevalence of stunting in 67 low-and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol. (2022) 32:337–44. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200537

36. Laksono, AD, Wulandari, RD, Amaliah, N, and Wisnuwardani, RW. Stunting among children under two years in Indonesia: does maternal education matter? PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0271509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271509

37. Syah, N, and Yuniarti, E. The relationship between maternal education level and stunting: literature review. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA. (2024) 10:704–10. doi: 10.29303/jppipa.v10i10.9495

38. Beal, T, Tumilowicz, A, Sutrisna, A, Izwardy, D, and Neufeld, LM. A review of child stunting determinants in Indonesia. Matern Child Nutr. (2018) 14:e12617. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12617

39. Raushan, R, Acharya, SS, and Raushan, MR. Caste and socioeconomic inequality in child health and nutrition in India. CASTE: Global J Social Exclusion. (2022) 3:345–64. doi: 10.26812/caste.v3i2.450

40. Van de Poel, E, and Speybroeck, N. Decomposing malnutrition inequalities between scheduled castes and tribes and the remaining Indian population. Ethn Health. (2009) 14:271–87. doi: 10.1080/13557850802609931

41. Bhadra, D. Spatial variation and risk factors of the dual burden of childhood stunting and underweight in India: a copula geoadditive modelling approach. J Nutritional Sci. (2024) 13:e52. doi: 10.1017/jns.2024.49

42. Khan, J, and Mohanty, SK. Poverty induced inequality in nutrition among children born during 2010–2021 in India. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0313596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0313596

43. Krishna, A, Mejía-Guevara, I, McGovern, M, Aguayo, VM, and Subramanian, S. Trends in inequalities in child stunting in South Asia. Matern Child Nutr. (2018) 14:e12517. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12517

44. Verma, A. K., and Joe, W. (2025). Does exposure to POSHAN Abhiyaan reduce the risk of malnutrition among children aged 6-23 months: evidence from high-burden districts of malnutrition in India, 2019-21. Demography India. 5372526.

45. Singh, SK, Chauhan, A, Alderman, H, Avula, R, Dwivedi, LK, Kapoor, R, et al. Utilization of integrated child development services (ICDS) and its linkages with undernutrition in India. Matern Child Nutr. (2024) 20:e13644. doi: 10.1111/mcn.13644

46. Jagannath, R, and Chakravarthy, V. The impact of Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojna scheme on access to services among mothers and children and their improved health and nutritional outcomes. Front Nutr. (2025) 11:1513815. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1513815

47. Arya, PK, Sur, K, Kundu, T, Dhote, S, and Singh, SK. Unveiling predictive factors for household-level stunting in India: a machine learning approach using NFHS-5 and satellite-driven data. Nutrition. (2025) 132:112674. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2024.112674

Keywords: single-mother households, child stunting, structural inequity, maternal height, wealth index, children under 5, India

Citation: Barik S, Singh A and Singh M (2025) Living with mother alone: exploring the risk of stunting among under-five children in India. Front. Nutr. 12:1700655. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1700655

Edited by:

Manzur Kader, Dalarna University, SwedenReviewed by:

Asif Ali, University of Burdwan, IndiaMukesh Vishwakarma, Andaman & Nicobar Islands Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Copyright © 2025 Barik, Singh and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mayank Singh, c2luZ2htYXlhbmsuMjUxMTk1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

†First authorship

‡ORCID: Soumen Barik, orcid.org/0009-0002-9639-0463

Anuj Singh, orcid.org/0000-0002-2582-4052

Mayank Singh, orcid.org/0000-0002-5350-6895

Soumen Barik

Soumen Barik Anuj Singh

Anuj Singh Mayank Singh

Mayank Singh