- 1Ninghai Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

- 2The Fourth Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Background: This study aimed to further corroborate a previously reported connection between zinc nutritional status and the occurrence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) among children and adolescents.

Methods: Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines, a systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted. The PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and PsyclNFO databases were searched for all relevant case–control studies published until January 2024. Cohen’s kappa was computed to assess reviewer agreement. This meta-analysis used a random-effects model to summarize the overall association between zinc levels and ASD. The Q-test and I2 statistics were used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the studies, while funnel plots, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test were used to evaluate publication bias.

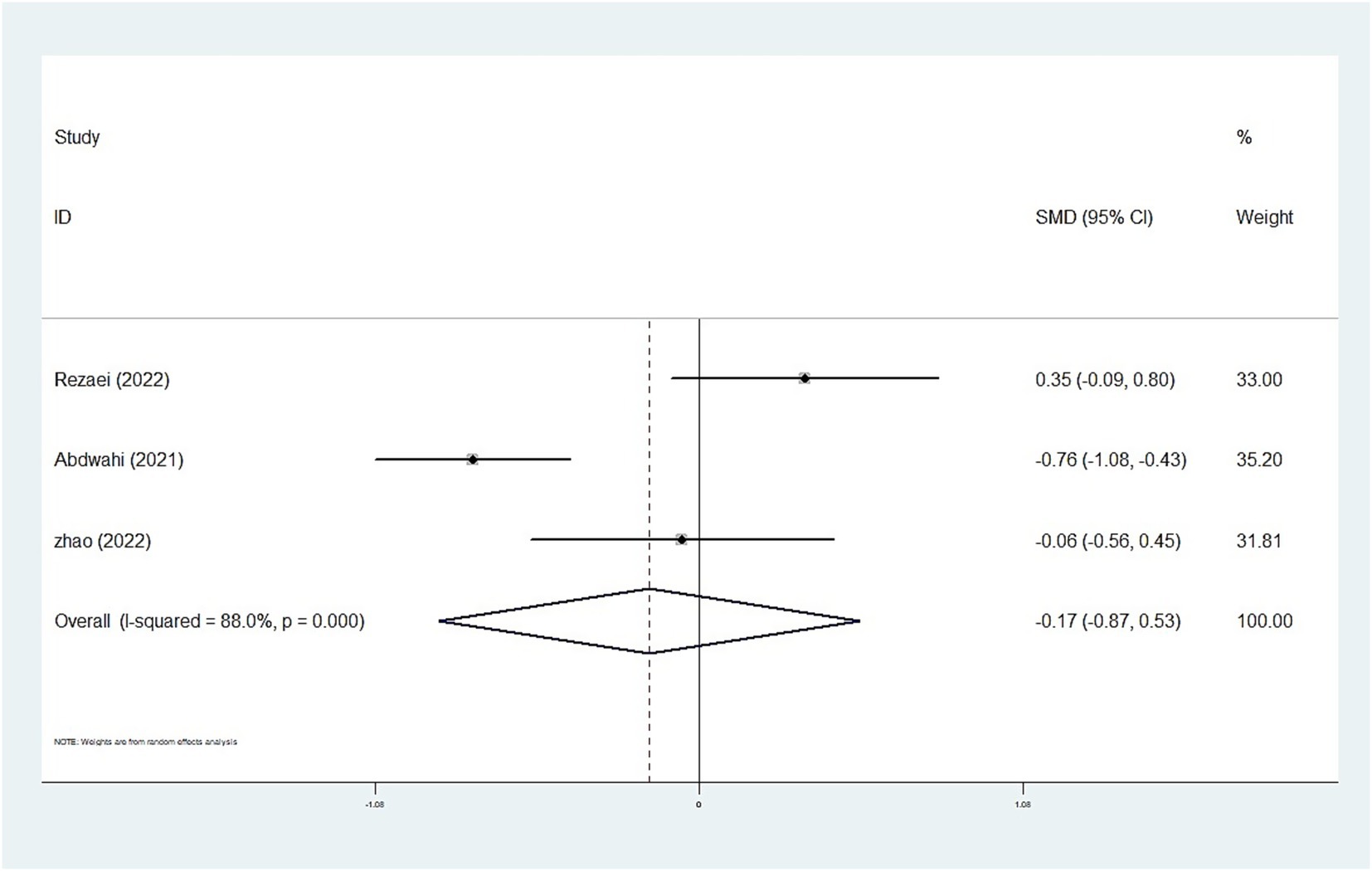

Results: We included 25 case–control studies with 4,763 children and adolescents, comprising 2,499 cases and 2,264 typical controls. The random-effects meta-analysis revealed that whole blood and plasma/serum zinc levels were negatively associated with ASD (standardized mean difference [SMD] = −0.44, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.63 to −0.25; SMD = −1.79, 95% CI: −2.74 to −0.84), whereas hair (SMD = −0.01, 95% CI: −0.40 to 0.37) and urinary (SMD = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.87 to 0.53) zinc levels were not associated with ASD. Moreover, we observed statistically significant heterogeneity among the included studies (plasma/serum zinc: I2 = 98.8%, P<0.001; hair zinc: I2 = 88.4%, P<0.001; urinary zinc: I2 = 88.0%, P<0.001).

Conclusion: Blood zinc levels were associated with ASD among children and adolescents. Therefore, screening blood zinc levels in children with ASD may be warranted. Further prospective studies are warranted to elucidate the role of zinc in the etiology of ASD.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a group of neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by impaired social interaction, repetitive stereotyped behaviors, and narrowed interests, which can lead to substantial disability across the life cycle (1). Recent research suggests that the global prevalence of ASD is 0.6%, with the prevalence in Asia, America, Europe, Africa, and Australia reported as 0.4, 1, 0.5, 1, and 1.7%, respectively (2). Although many studies have shown that genetic, environmental, and immunological factors play important roles in the etiology of ASD, the exact mechanisms remain unclear (3). Research suggests that nutrients, as an important environmental factor, may also be associated with ASD development (4).

Zinc is an essential trace element in the human body. It serves as a component and activator of metalloenzymes and is related to the activity of over 300 enzymes (5). Zinc deficiency can lead to reduced activity of zinc-containing enzymes, such as DNA and RNA polymerases, thereby decreasing the levels of DNA and RNA in nerve cells and affecting cell division and proliferation (e.g., in hippocampal progenitor cells). These effects can consequently influence the development of brain structure and function in children (6, 7). Therefore, zinc plays an important role in maintaining the normal structure and functions of the central nervous system, especially during the first 1,000 days of life (8). Severe zinc deficiency can lead to neuropsychological changes such as emotional instability, irritability, and depression (5, 9). Animal studies have shown that zinc deficiency, including during pregnancy, leads to ASD-related behaviors such as impaired social communication, communication disorders, and repetitive stereotyped behaviors (10, 11). In addition, eating-related problems, such as fussy eating, preference for specific foods, and stereotyped eating behavior, are more common among children with ASD than among those without ASD (12). Therefore, children with ASD may get even less zinc from food, potentially further aggravating ASD-related behaviors.

Epidemiological investigations have shown that serum zinc levels were significantly lower among children with ASD than among those without ASD (13, 14). Clinical trials have reported that zinc supplementation can alleviate clinical symptoms in children with zinc deficiency and ASD (15). Moreover, a clinical study found that zinc supplementation in children with ASD increased cognitive motor ability (16). However, some studies found that the zinc nutritional status was significantly higher among children with ASD than among children in the control group (17). Moreover, other studies did not find any association between zinc nutritional status and ASD (18, 19). Therefore, the association between zinc status and ASD remains inconsistent in population studies.

Although a systematic review of zinc status and ASD has recently been published (6), it only reported lower zinc concentrations among individuals with ASD and lacked a detailed statistical examination, such as a quantitative analysis of the combined effect size. In addition, given the rising prevalence of ASD and the importance of zinc for physical and mental development, further studies on the relationship between zinc nutritional status and ASD in children and adolescents are necessary to corroborate the previously established connection. We believe that our research will be of interest to some researchers. Therefore, we aimed to conduct a meta-analysis to review and summarize the available evidence from observational studies and clarify the association between zinc and ASD and to further provide evidence for zinc supplementation in children with ASD.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted this study in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (20). The study protocol was registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY; registration number: INPLASY202450023). Electronic searches of the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and PsyclNFO databases for English-language literature were conducted from their inception to 13 January 2024. In addition, we manually reviewed the list of references included in the articles to avoid the potential omission of relevant articles. The search included a combination of MeSH words and free text words as follows: “Trace Elements,” “Zinc,” “Zinc levels” or “Trace Element” and “Autism,” “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” “ASD,” or “Autistic Disorder.” Supplementary Table S1 presents the search strategy used for each database.

Study selection

The inclusion criterion was case–control investigations involving children and adolescents aged 2–18 years. The diagnosis relied on either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) (21). The zinc concentrations in eligible ASD children were analyzed by measuring zinc levels in biological specimens. All included studies were required to provide comprehensive data. Reviews, animal experiments, meeting minutes, redundant literature (such as same themes and same cohort), and studies involving additional psychiatric disorders were excluded.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Reviewers independently and redundantly extracted the following details from the studies: surname of the primary author, year of publication, geographical setting of the study, age of the participants, sample size, sample source, analytical method used to detect zinc, and zinc levels (mean ± standard deviation) in both the case and control groups. Three investigators (Hezuo Liu, Ji Chen, and Jia He) independently extracted the literature data. Cohen’s kappa was computed to assess the inter-rater reliability during data extraction. The agreement between the two investigators was 95%. In case of disagreement, the third investigator (Xuening Li) decided to extract the literature data. If supplementary information was needed, direct communication via email was established with the principal authors.

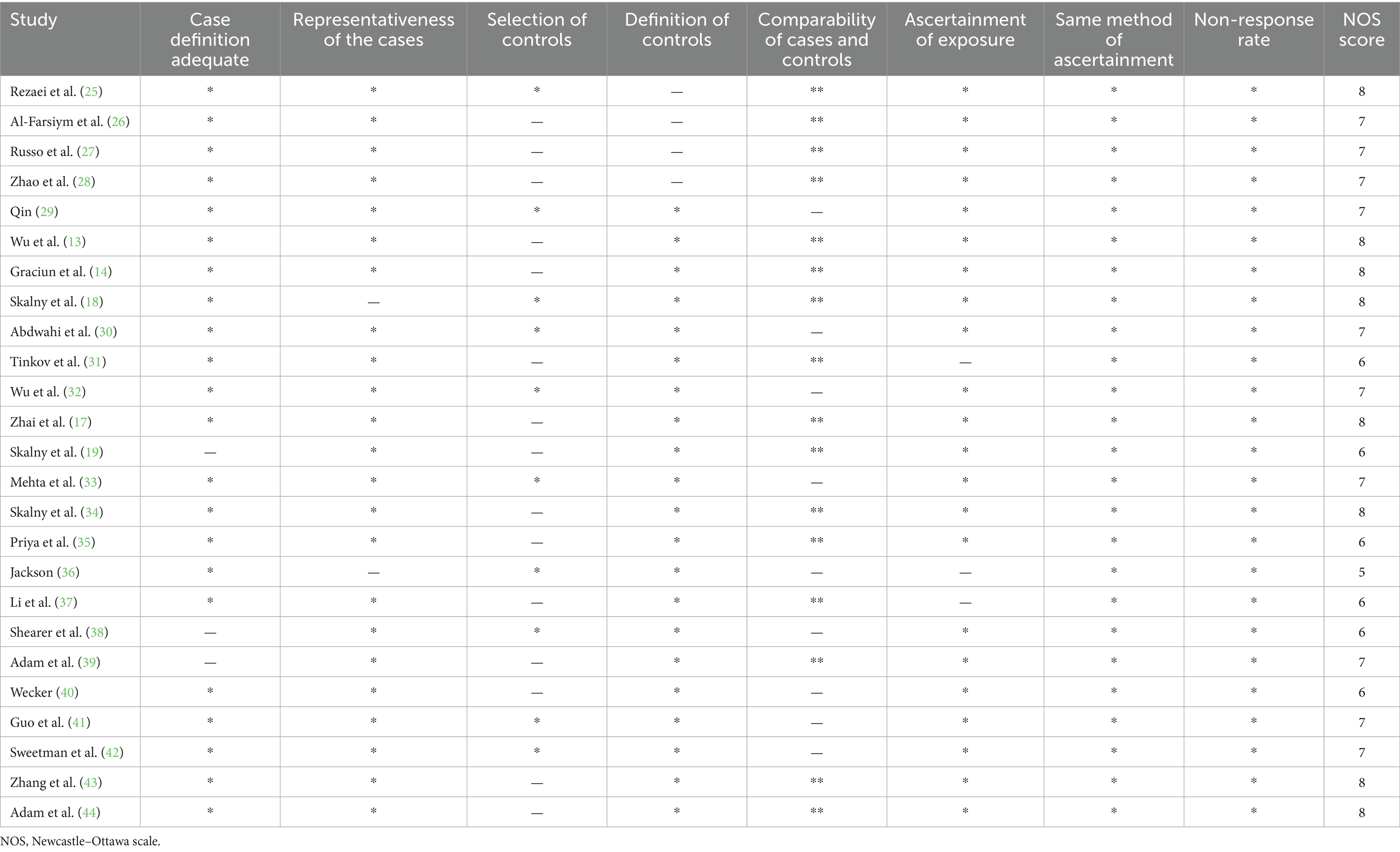

The Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) was used to evaluate each study using six items in three groups, including selection, exposure, and comparability. In addition to the Comparability item, each item could receive 1 point (1 star), with the total range being 0 to 2 stars (22). The final scores for the classification of the risk of bias were as follows: ≥7 stars, high quality; ≥4 and ≤6 stars, moderate quality; and <4 stars, low quality.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 12.0 software (Stata Corporation LLC, College Station, United States). Cohen’s kappa was computed to assess reviewer agreement. Standardized mean differences (SMDs) were pooled in the meta-analysis because the units were uniform across studies (23). Therefore, the association between zinc levels in whole blood, plasma/serum, hair, and urine with ASD was evaluated using a combination of SMDs and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity among the studies was assessed using the I2 test, with I2 > 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Consequently, the random-effects model was used to merge the data due to high heterogeneity (24). Subgroup and sensitivity analyses were also performed to investigate the sources of heterogeneity. The subgroup analysis stratified the studies based on the sample source (serum, plasma, and whole blood), region of study (Europe and America, Russia, and Asia), year of study (≤2010 and >2010), zinc measurement method (inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry [ICP-MS] and other methods), diagnostic criteria, and NOS score (≤6 and ≥7). Sensitivity analyses were performed using the metaninf test to assess the impact of each individual study on the overall result. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, Begg’s test, and Egger’s test. p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant, except for Begg’s test and Egger’s test, where the p-value was less than 0.1.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

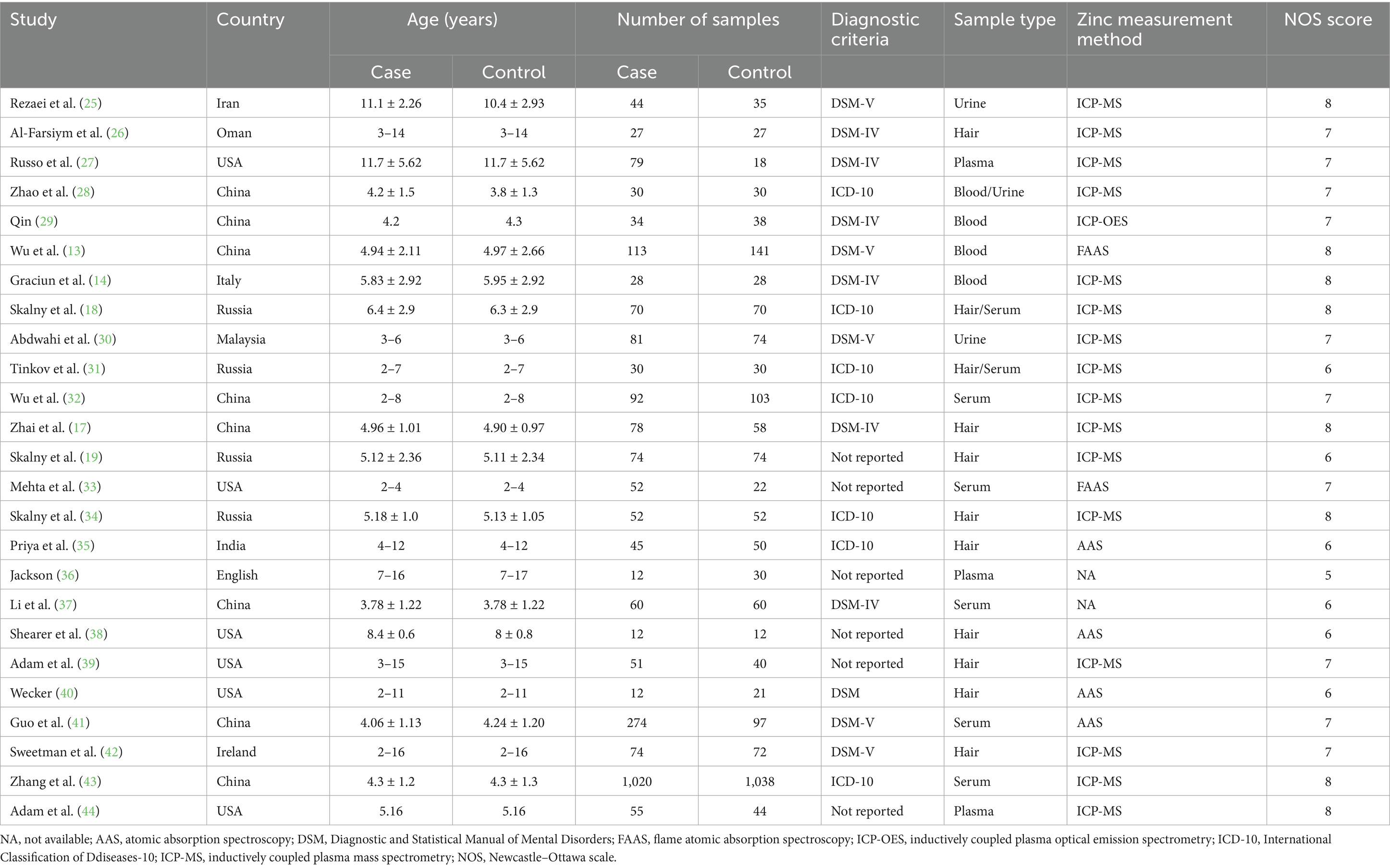

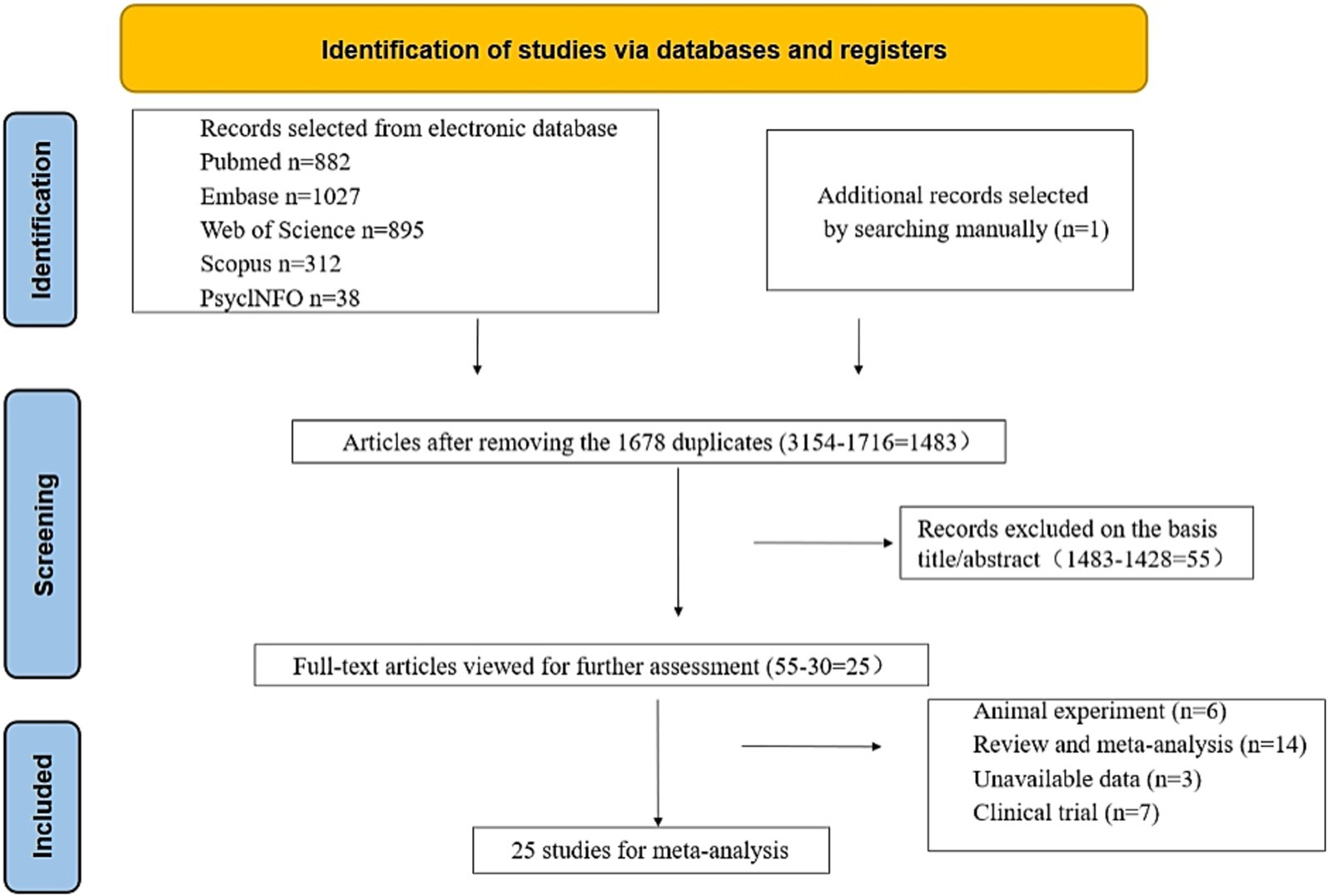

We conducted a comprehensive search of the literature and examined 3,154 articles from various reputable databases, including PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and PsyclNFO. We identified one additional article by reviewing the reference lists of the relevant studies. We eliminated 1,716 duplicate articles through both automated and manual processes. Subsequently, we excluded 1,428 unrelated studies by carefully reviewing the titles and abstracts. Eventually, 55 studies were identified, which merited a thorough examination. After further scrutiny, 30 studies were deemed unsuitable for inclusion; the reasons for exclusion were 6 animal studies, 14 reviews or meta-analyses, 3 with unavailable data, and 7 clinical trials. Ultimately, our meta-analysis included 25 studies (Table 1) (13, 14, 17–19, 25–44). Among these, 14 studies involving 3,698 participants (case: 1,949 and control: 1,749) reported blood zinc levels, 11 studies involving 1,031 participants (case: 525 and control: 506) focused on hair zinc levels, and 3 studies involving 294 participants (case: 155 and control: 139) focused on urine zinc levels (Figure 1).

Table 1 presents the primary features of the 25 case–control studies included in this meta-analysis, which were published between 1978 and 2023. Among the 14 studies (case: 1,949 and control: 1,749) examining the correlation between blood zinc and ASD, 7 focused on serum zinc (case: 1,598 and control: 1,420), 3 focused on plasma zinc (case: 146 and control: 92), and 4 focused on the zinc concentration in whole blood (case: 205 and control: 237). Furthermore, Table 2 provides the quality assessments of the included studies.

Overall meta-analysis

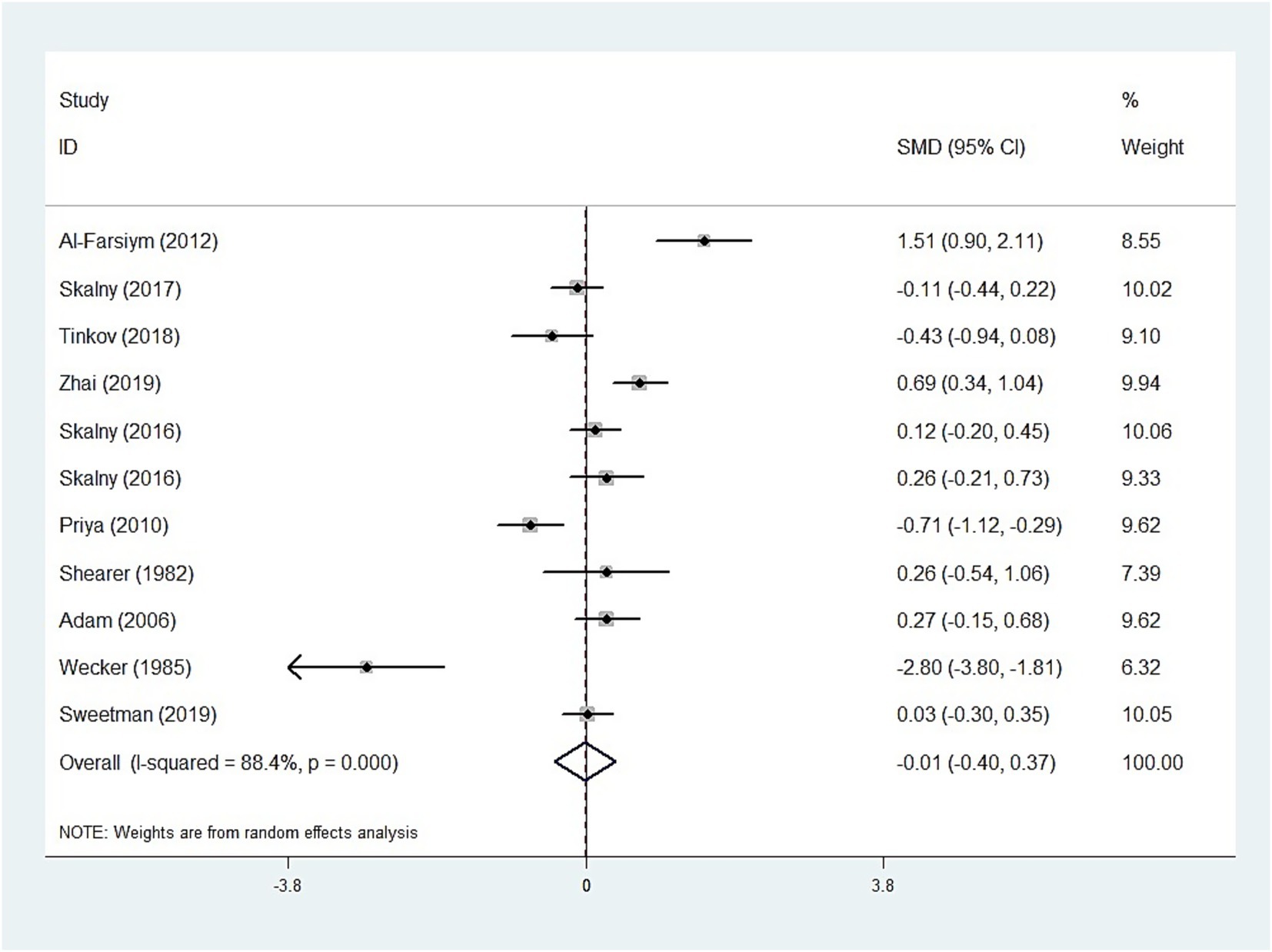

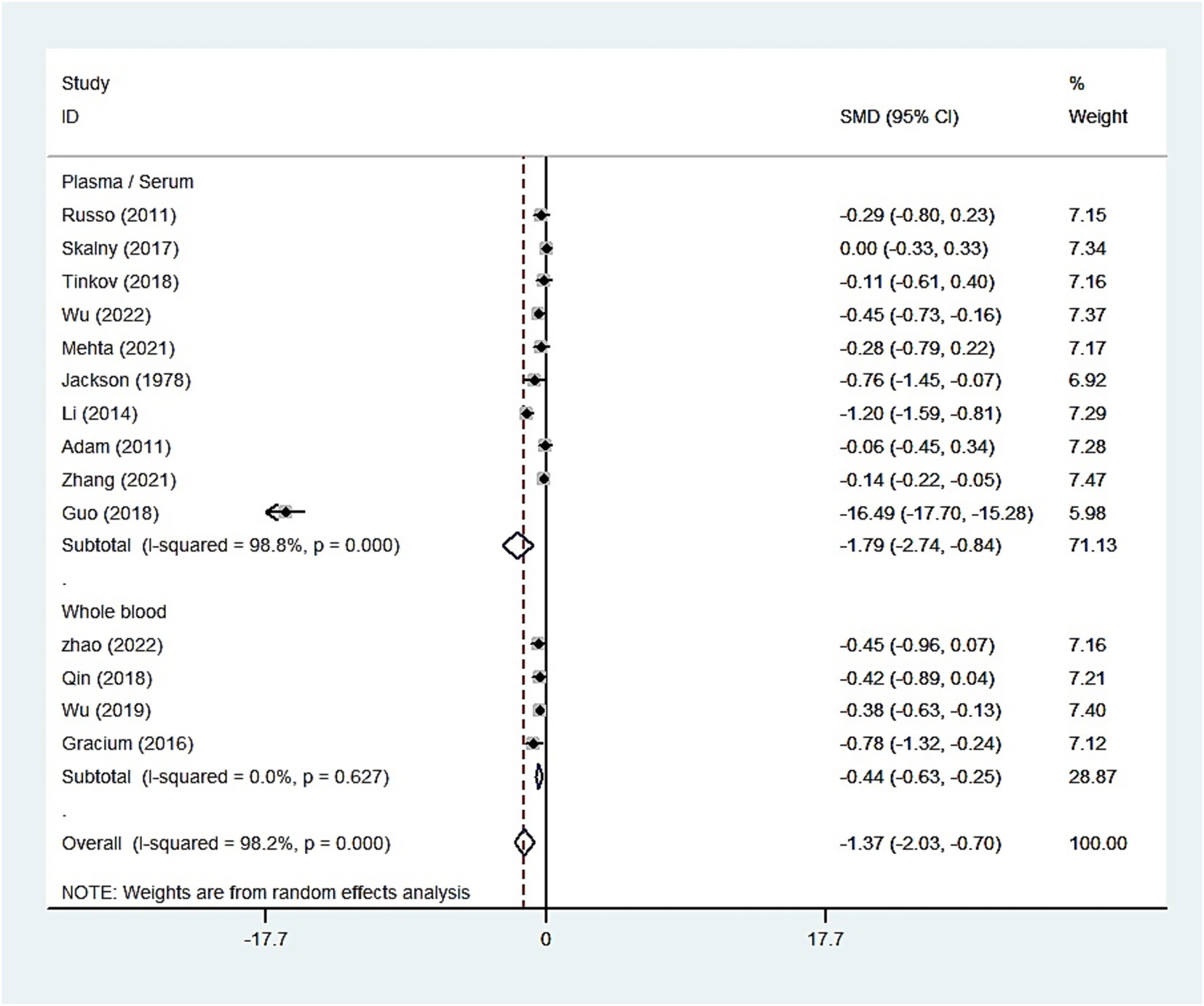

The whole blood and plasma/serum zinc levels were negatively associated with ASD (SMD = −0.44, 95% [CI]: −0.63 to −0.25; SMD = −1.79, 95% CI: −2.74 to −0.84), while hair (SMD = −0.01, 95% CI: −0.40 to 0.37) and urinary (SMD = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.87 to 0.53) zinc levels were not associated with ASD (Figures 2–4). Nevertheless, the included studies exhibited significant heterogeneity (plasma/serum zinc: I2 = 98.8%, P<0.001; hair zinc: I2 = 88.4%, P<0.001; urinary zinc: I2 = 88.0%, P<0.001).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the blood zinc levels in children with autism spectrum disorder and controls.

Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses

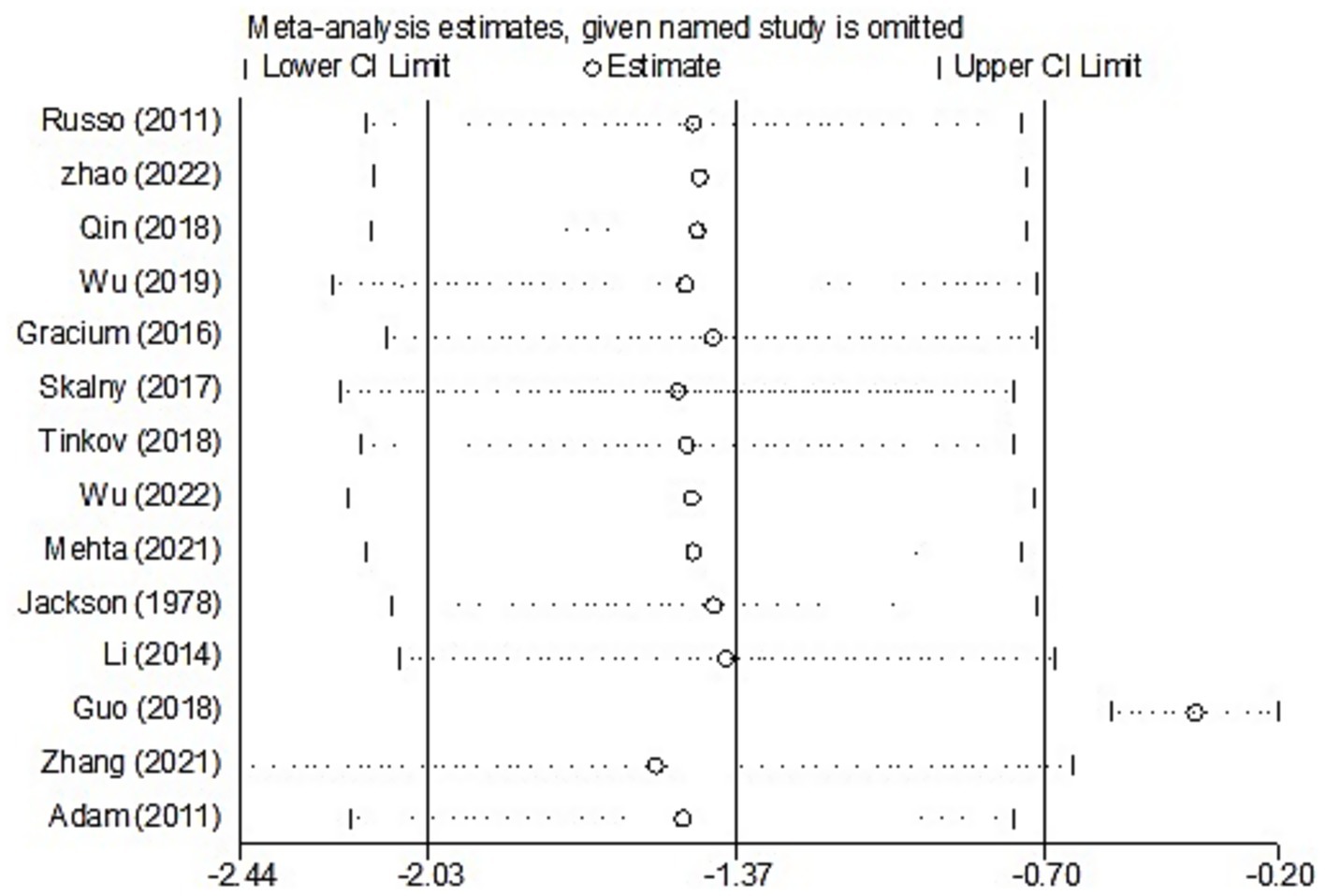

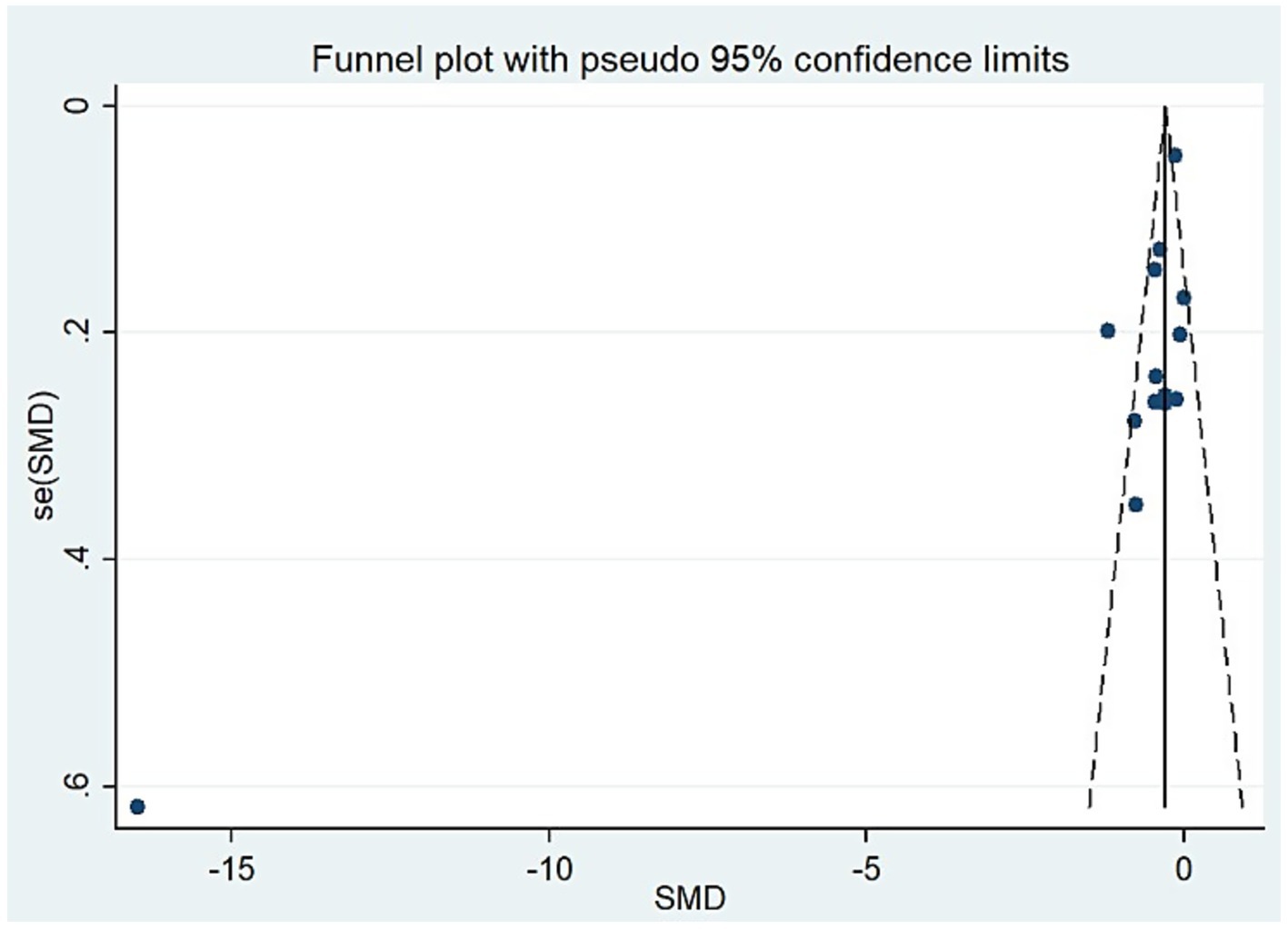

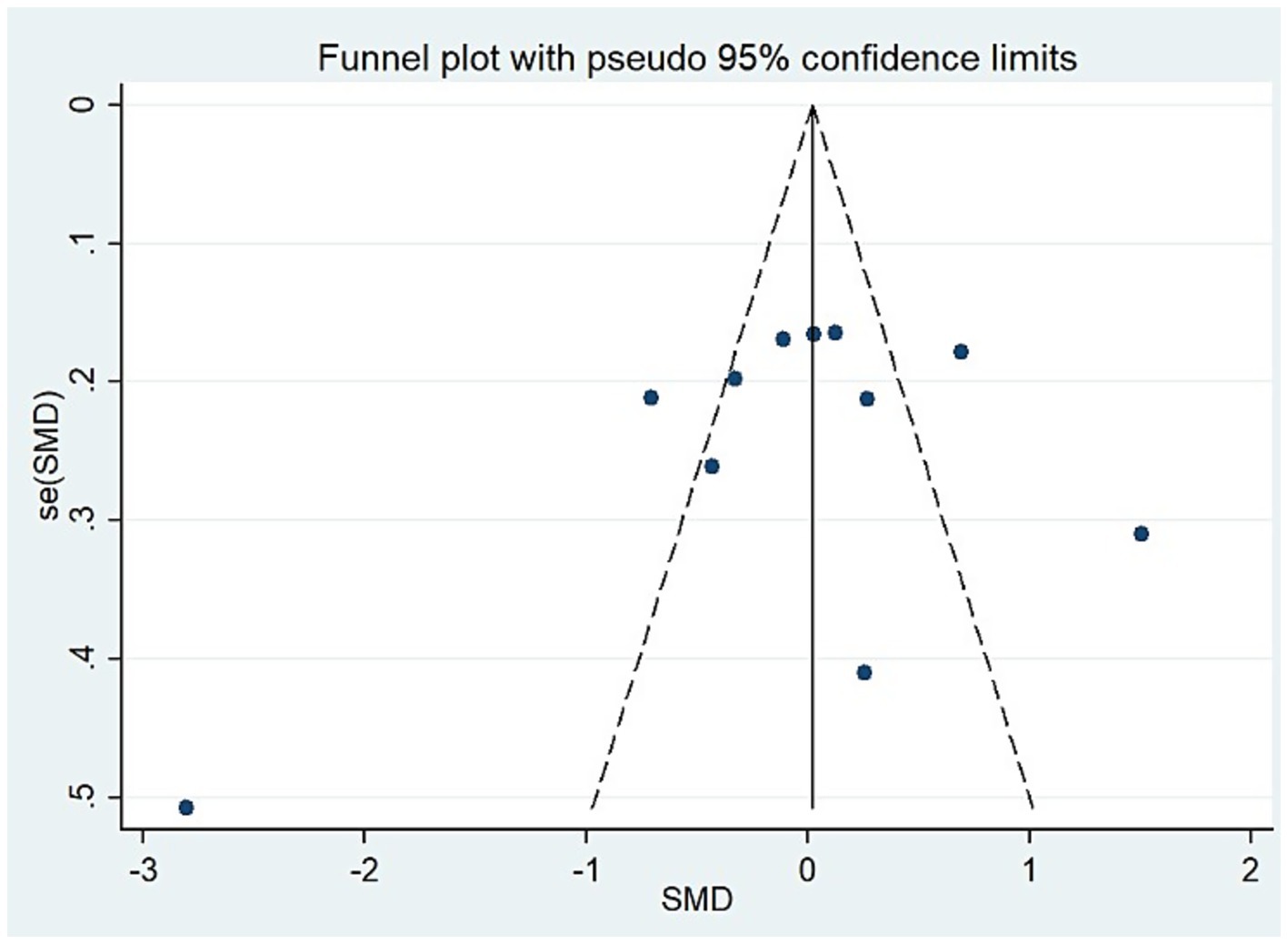

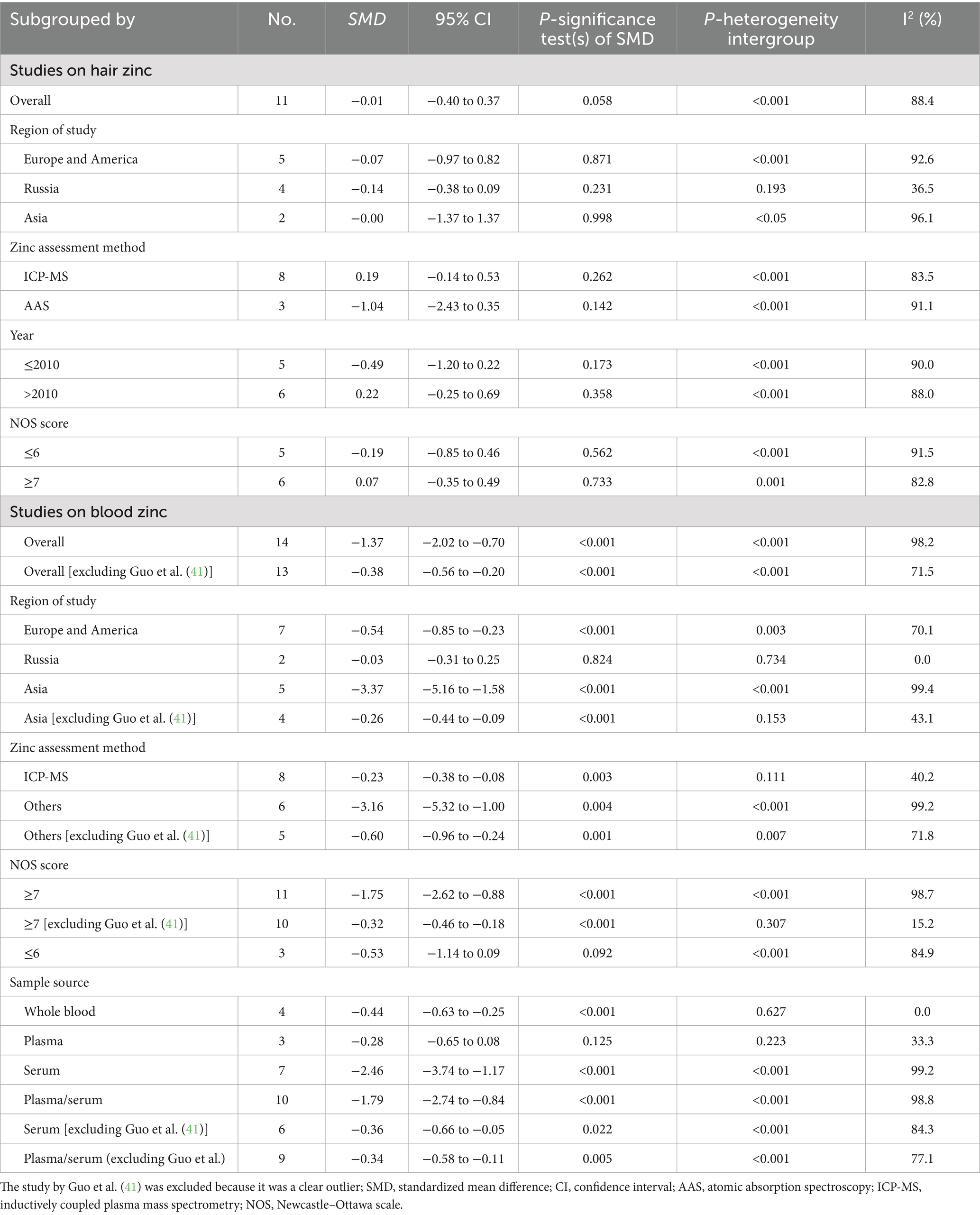

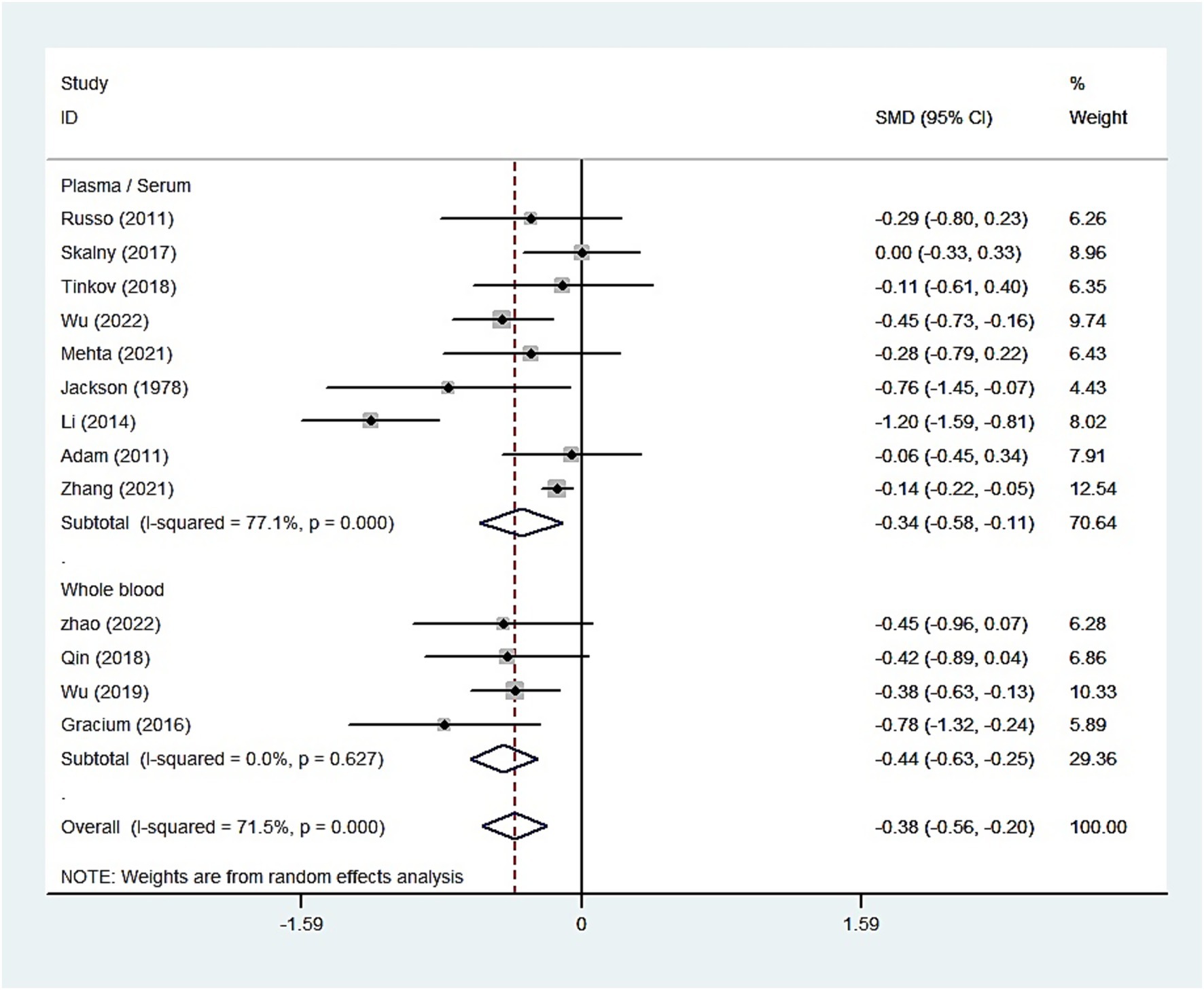

For studies analyzing blood zinc levels, a subgroup analysis was performed. The heterogeneity was reduced for the region of study (Russia), sample source (whole blood), and zinc assessment method (ICP-MS) (Table 3). Given the heterogeneity of our study, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. After removing each article individually, the sensitivity analysis indicated that the study by Guo et al. (41) was a clear outlier (Figure 5). In addition, the results indicated publication bias in the meta-analysis (Begg’s test, p = 0.063; Egger’s test, p = 0.099). The funnel plot was asymmetrical, due to the inclusion of the study (Figure 6), which altered the pooled estimate for plasma/serum (SMD = −0.34, 95% CI: −0.58 to −0.11) and reduced heterogeneity (I2 = 77.1%, P<0.001) (Table 3; Figure 7). However, no substantial modifications were observed (Table 3).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis to assess the blood and hair zinc levels in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Figure 7. Forest plot of the blood zinc levels in children with autism spectrum disorder and controls [excluding Guo et al. (41)].

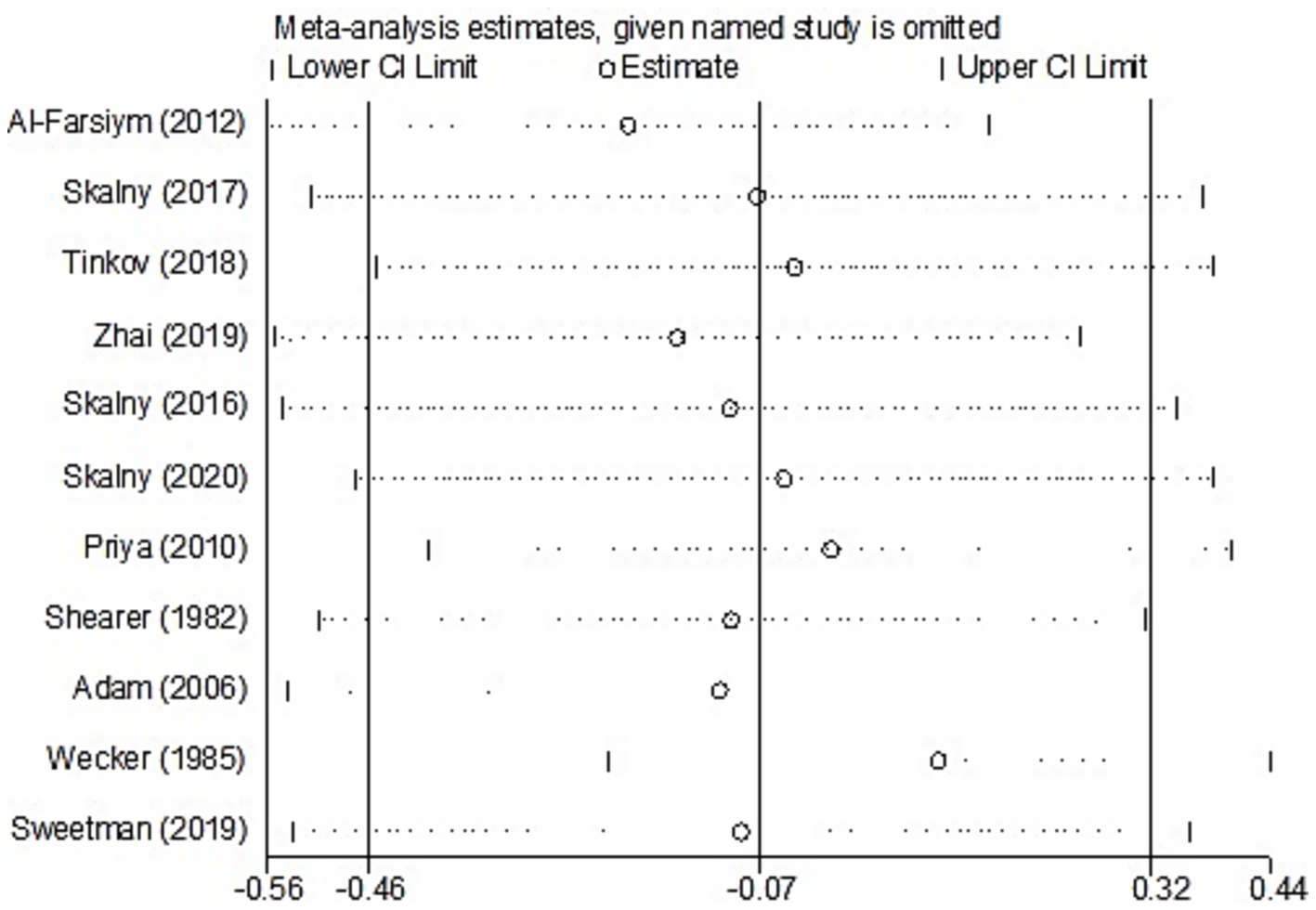

For studies analyzing hair zinc levels, subgroup analysis was performed based on the region of study (Europe and America, Russia, and Asia), year of study (≤2010 and >2010), zinc assessment method (ICP-MS and other methods), and NOS score (≤6 and ≥7). The heterogeneity was reduced for the region of study (Russia) (Table 3). After removing each article individually, the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the combined results remained unchanged (Figure 8). The observations did not indicate any publication bias in the meta-analysis (Begg’s test, p = 0.484; Egger’s test, p = 0.450) (Figure 9).

Discussion

The meta-analysis included 25 studies involving 4,763 participants. The results suggested a statistically significant difference in blood zinc levels between children with ASD and those in the control group, whereas no statistical significance was observed in urine or hair zinc levels. Substantial heterogeneity was present among the included studies. This meta-analysis found that children with ASD have lower blood zinc levels than children in the control group. Another meta-analysis found an association between plasma zinc and ASD, but no subgroup analysis was conducted (45). The majority of studies on zinc and ASD discussed in this meta-analysis were published before 2012; however, subsequent studies examining the correlation between zinc and ASD have been conducted since 2011. Our comprehensive meta-analysis included 25 surveys, 17 of which were published after 2011. Therefore, it was imperative to delve further into the relationship between zinc and ASD.

There was substantial heterogeneity among the included studies. The high heterogeneity observed in this meta-analysis may be attributed to various variables, such as demographics, sample source, assessment method, and adjusted statistical parameters. Therefore, the random-effects model was used to pool the data, and subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the sources of heterogeneity (24). The heterogeneity was reduced for the sample source and the zinc assessment method when exploring the sources of heterogeneity in studies on blood zinc. In our analysis, blood zinc levels included whole blood, serum, and plasma, which also accounted for the high heterogeneity observed. Previous studies have suggested that zinc concentrations in platelets, polymorphonuclear cells, mononuclear cells, and erythrocytes are not effective biomarkers of zinc status (9). Furthermore, serum and plasma zinc concentrations do not differ significantly in their relation to zinc nutritional status and are therefore used interchangeably in systematic reviews. Therefore, in addition to conducting a separate analysis of whole blood, we also pooled data from plasma and serum studies. The results from these analyses similarly indicated an association between zinc and ASD. In addition, previous research has compared serum and plasma zinc measurements using the atomic absorption spectrometer (AAS), inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES), and ICP-MS. Despite yielding similar zinc concentrations, accuracy, and precision when standardized materials and methods are applied, serum and plasma zinc measurements consistently show the highest coefficients of variation—regardless of the analytical platform used (AAS, ICP-OES, or ICP-MS) (46). Therefore, future studies should focus on methodological improvements, particularly for ICP-MS, to improve measurement precision. We found that, in the majority of studies, in addition to measuring blood zinc levels, hair zinc measurements are also commonly used in research involving individuals with ASD due to their advantages as a relevant, non-invasive, and easily collectible method (6). However, hair metal measurements can be affected by external contamination that is not easily removed through simple washing; therefore, hair zinc level testing is generally not recommended. In addition, sensitivity analyses identified the study by Guo et al. (41) as a clear outlier. After removing this study, the combined outcome was slightly altered, and heterogeneity was reduced; however, no substantial changes were observed, and the conclusion that blood zinc levels are negatively associated with ASD remained unchanged.

There are many causes of zinc deficiency among children with ASD. In addition to the physiological factors associated with ASD, specific dietary behaviors, such as rigid and repetitive eating patterns, fussy eating, and refusal to try new foods, can directly affect zinc intake (12). Gastrointestinal changes in children with ASD are another important factor that can affect blood zinc levels (47). A total of eight out of ten children with ASD experience gastrointestinal disturbances or dysfunctions, with the most common symptoms being vomiting, diarrhea, nausea, gastroesophageal reflux, and abdominal pain or distension (6, 47). Gastrointestinal disturbances or dysfunctions can directly and significantly affect zinc status, as zinc is involved in mechanisms that maintain gastrointestinal homeostasis (6). In addition, other factors influencing zinc levels in children’s blood and hair, such as variations in other metals (e.g., copper, lead, and cadmium), should be considered (6, 48). Evidence suggests that low zinc concentrations in children with severe ASD are associated with high concentrations of toxic metals, including lead, mercury, barium, and lithium (6, 49). Zinc is related to metallothionein, which primarily regulates zinc homeostasis within brain cells. Metallothionein also has a detoxification effect when combined with other metals, such as lead, cadmium, and copper (50). Therefore, high levels of toxic metals and trace element deficiencies in children have negative effects on neurodevelopment (51).

Regarding the underlying mechanisms of zinc, recent studies suggest that its interaction with synaptic dysfunction plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ASD (5). Several studies have shown that zinc deficiency damages the synaptic proline-rich synapse-associated protein 2 (ProSAP)/Shank scaffold, leading to alterations in synapse formation, maturation, and plasticity, and is associated with ASD behavior (11, 52). N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) function is highly modulated by zinc, which is co-released with glutamate and concentrated in postsynaptic spines (53). Zinc mobilization increased NMDAR signaling and significantly improved social interaction in a murine model of ASD lacking Shank2 (54). In hippocampal cell cultures, an ASD-like biometal profile leads to a reduction of NMDAR (NR/Grin/GluN) subunits 1 and 2a, as well as Shank gene expression, along with a reduction of synapse density, and zinc supplementation was shown to rescue the aforementioned alterations (55). Some studies have also suggested that other zinc-dependent signaling mechanisms may be involved in the pathogenesis of ASD, such as cytoskeleton-regulating cortactin binding protein 2, P2X7R-mediated signaling, and the gut–brain axis (5).

Generally, the most recent research data demonstrate the critical role of zinc metabolism in the pathogenesis of ASD. Meanwhile, our research also confirms the existence of an association between blood zinc and ASD among children and adolescents. However, there is a lack of information on the potential translation of zinc-targeted therapy in humans, especially studies exploring how zinc supplementation affects human neuronal or synaptic function (53). Animal studies have shown that SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains proteins (SHANKs) and NMDARs are key targets for effective zinc-induced therapy. Therefore, zinc supplementation also needs to be specifically examined in ASD patients involving mutations in SHANKs and NMDARs (53).

This meta-analysis has some limitations. First, as the included studies did not account for gender differences, we cannot determine whether gender influences the observed association. In addition, ASD diagnosis is much more complicated in children under the age of 3 years. However, we were not able to stratify by age groups due to the wide age range in the included studies. Second, the studies analyzed in this article were case–control in design, making it difficult to completely avoid recall bias and preventing any inference of a causal relationship between zinc and ASD. Since the effect of zinc deficiency on ASD is more pronounced in early life (5), including during pregnancy, we attempted to collect cohort studies to examine this relationship; however, only one relevant article was found (56). Therefore, further prospective studies are warranted to elucidate the role of zinc in the etiology of ASD, although the study design is difficult. Given the absence of validated early-life biomarkers, participant ascertainment was necessarily restricted to individuals aged at least 2 years. This limitation precludes direct insights into the prenatal period, which animal model studies implicate as a critical window for initial zinc dysregulation during fetal neurodevelopment (10). Consequently, our assessment of older children—whose zinc status is subject to substantial modulation by postnatal dietary and lifestyle factors—likely captures a confounded and heterogeneous physiological state. This temporal misalignment is a plausible source of the inconsistencies observed in the broader epidemiological literature. The robust group differences measured despite this significant dilution bias underscore the strength and biological significance of the underlying association. Third, due to the considerable time span of the included studies, the diagnostic criteria for ASD varied (for instance, regarding the inclusion of Asperger’s syndrome), which could potentially influence our conclusions. Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with stratification based on diagnostic criteria (DSM, DSM-IV, DSM-V, and ICD-10). The results of this sensitivity analysis for blood zinc remained consistent and did not alter our overall conclusions (Supplementary Table S2).

Conclusion

Our meta-analysis concluded that children and adolescents with ASD have lower blood zinc levels than their typical counterparts and that ASD is associated with zinc nutritional status. Therefore, screening blood zinc levels in children with ASD may be reasonable. Further prospective studies are warranted to elucidate the role of zinc in the etiology of ASD. In addition, in the absence of validated biomarkers for the early diagnosis of ASD, identifying reliable biomarkers remains a priority for future research.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

HL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JC: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JH: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Doctoral Research Startup Fund Project of Liaoning Province (grant number 2025-BS-0564).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the staff of the Child Health Department of Ninghai Maternal and Child Health Hospital and Dr. Dan Xiong for supporting this systematic review. We would also like to thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1710999/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Hyman, SL, Levy, SE, and Myers, SM. Council on children with disabilities, section on developmental and behavioral pediatrics identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics. (2020) 145:e20193447. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3447

2. Salari, N, Rasoulpoor, S, Rasoulpoor, S, Shohaimi, S, Jafarpour, S, Abdoli, N, et al. The global prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. (2022) 48:112. doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01310-w

3. Wang, L, Wang, B, Wu, C, Wang, J, and Sun, M. Autism spectrum disorder: neurodevelopmental risk factors, biological mechanism, and precision therapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 24:1819. doi: 10.3390/ijms24031819

4. Karhu, E, Zukerman, R, Eshraghi, RS, Mittal, J, Deth, RC, Castejon, AM, et al. Nutritional interventions for autism spectrum disorder. Nutr Rev. (2020) 78:515–31. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz092

5. Skalny, AV, Aschner, M, and Tinkov, AA. Zinc. Adv Food Nutr Res. (2021) 96:251–310. doi: 10.1016/bs.afnr.2021.01.003

6. do, PKDSB, Oliveira, DF, de, TLSA, and de, AA. Zinc status and autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Nutrients. (2023) 15:3663. doi: 10.3390/nu15163663

7. Al-Naama, N, Mackeh, R, and Kino, T. C2H2-type zinc finger proteins in brain development, neurodevelopmental, and other neuropsychiatric disorders: systematic literature-based analysis. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:32. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00032

8. Gammoh, NZ, and Rink, L. Zinc in infection and inflammation. Nutrients. (2017) 9:624. doi: 10.3390/nu9060624

9. Lowe, NM, Fekete, K, and Decsi, T. Methods of assessment of zinc status in humans: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. (2009) 89:2040S–51S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27230G

10. Sauer, AK, Hagmeyer, S, and Grabrucker, AM. Prenatal zinc deficient mice as a model for autism spectrum disorders. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:6082. doi: 10.3390/ijms23116082

11. Grabrucker, S, Jannetti, L, Eckert, M, Gaub, S, Chhabra, R, Pfaender, S, et al. Zinc deficiency dysregulates the synaptic ProSAP/Shank scaffold and might contribute to autism spectrum disorders. Brain. (2014) 137:137–52. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt303

12. Bandini, LG, Curtin, C, Phillips, S, Anderson, SE, Maslin, M, and Must, A. Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. (2017) 47:439–46. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2963-6

13. Wu, LL, Mao, SS, Lin, X, Yang, RW, and Zhu, ZW. Evaluation of whole blood trace element levels in Chinese children with autism spectrum disorder. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2019) 191:269–75. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1615-4

14. Crăciun, EC, Bjørklund, G, Tinkov, AA, Urbina, MA, Skalny, AV, Rad, F, et al. Evaluation of whole blood zinc and copper levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. Metab Brain Dis. (2016) 31:887–90. doi: 10.1007/s11011-016-9823-0

15. Bou Khalil, R, and Yazbek, JC. Potential importance of supplementation with zinc for autism spectrum disorder. Encéphale. (2021) 47:514–7. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2020.12.005

16. Meguid, NA, Bjørklund, G, Gebril, OH, Doşa, MD, Anwar, M, Elsaeid, A, et al. The role of zinc supplementation on the metallothionein system in children with autism spectrum disorder. Acta Neurol Belg. (2019) 119:577–83. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01181-9

17. Zhai, Q, Cen, S, Jiang, J, Zhao, J, Zhang, H, and Chen, W. Disturbance of trace element and gut microbiota profiles as indicators of autism spectrum disorder: a pilot study of Chinese children. Environ Res. (2019) 171:501–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.01.060

18. Skalny, AV, Simashkova, NV, Skalnaya, AA, Klyushnik, TP, Bjørklund, G, Skalnaya, MG, et al. Assessment of gender and age effects on serum and hair trace element levels in children with autism spectrum disorder. Metab Brain Dis. (2017) 32:1675–84. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0056-7

19. Skalny, AV, Simashkova, NV, Klyushnik, TP, Grabeklis, AR, Bjørklund, G, Skalnaya, MG, et al. Hair toxic and essential trace elements in children with autism spectrum disorder. Metab Brain Dis. (2017) 32:195–202. doi: 10.1007/s11011-016-9899-6

20. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DGPRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

21. Doernberg, E, and Hollander, E. Neurodevelopmental disorders (ASD and ADHD): DSM-5, ICD-10, and ICD-11. CNS Spectr. (2016) 21:295–9. doi: 10.1017/S1092852916000262

22. Lo, CK, Mertz, D, and Loeb, M. Newcastle-Ottawa scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2014) 14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-45

23. Andrade, C. Mean difference, standardized mean difference (SMD), and their use in meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. (2020) 81:20f13681. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20f13681

24. Barili, F, Parolari, A, Kappetein, PA, and Freemantle, N. Statistical primer: heterogeneity, random- or fixed-effects model analyses? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. (2018) 27:317–21. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivy163

25. Rezaei, M, Rezaei, A, Esmaeili, A, Nakhaee, S, Azadi, NA, and Mansouri, B. A case-control study on the relationship between urine trace element levels and autism spectrum disorder among Iranian children. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2022) 29:57287–95. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-19933-1

26. Al-Farsi, YM, Waly, MI, Al-Sharbati, MM, Al-Shafaee, MA, Al-Farsi, OA, Al-Khaduri, MM, et al. Levels of heavy metals and essential minerals in hair samples of children with autism in Oman: a case-control study. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2013) 151:181–6. doi: 10.1007/s12011-012-9553-z

27. Russo, AJ, and Devito, R. Analysis of copper and zinc plasma concentration and the efficacy of zinc therapy in individuals with asperger's syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) and autism. Biomark Insights. (2011) 6:127–33. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S7286

28. Zhao, G, Liu, SJ, Gan, XY, Li, JR, Wu, XX, Liu, SY, et al. Analysis of whole blood and urine trace elements in children with autism spectrum disorders and autistic behaviors. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2023) 201:627–35. doi: 10.1007/s12011-022-03197-4

29. Qin, YY, Jian, B, Wu, C, Jiang, CZ, Kang, Y, Zhou, JX, et al. A comparison of blood metal levels in autism spectrum disorder and unaffected children in Shenzhen of China and factors involved in bioaccumulation of metals. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2018) 25:17950–6. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1957-7

30. Abd Wahil, MS, Ja'afar, MH, and Md Isa, Z. Assessment of urinary lead (pb) and essential trace elements in autism spectrum disorder: a case-control study among preschool children in Malaysia. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2022) 200:97–121. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02654-w

31. Tinkov, AA, Skalnaya, MG, Simashkova, NV, Klyushnik, TP, Skalnaya, AA, Bjørklund, G, et al. Association between catatonia and levels of hair and serum trace elements and minerals in autism spectrum disorder. Biomed Pharmacother. (2019) 109:174–80. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.051

32. Wu, J, Wang, D, Yan, L, Jia, M, Zhang, J, Han, S, et al. Associations of essential element serum concentrations with autism spectrum disorder. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. (2022) 29:88962–71. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-21978-1

33. Mehta, SQ, Behl, S, Day, PL, Delgado, AM, Larson, NB, Stromback, LR, et al. Evaluation of Zn, cu, and se levels in the north American autism spectrum disorder population. Front Mol Neurosci. (2021) 14:665686. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2021.665686

34. Skalny, AV, Mazaletskaya, AL, Ajsuvakova, OP, Bjørklund, G, Skalnaya, MG, Notova, SV, et al. Hair trace element concentrations in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Trace Elem Med Biol. (2020) 61:126539. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126539

35. Lakshmi Priya, MD, and Geetha, A. Level of trace elements (copper, zinc, magnesium and selenium) and toxic elements (lead and mercury) in the hair and nail of children with autism. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2011) 142:148–58. doi: 10.1007/s12011-010-8766-2

36. Jackson, MJ, and Garrod, PJ. Plasma zinc, copper, and amino acid levels in the blood of autistic children. J Autism Child Schizophr. (1987) 8:203–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01537869

37. Li, SO, Wang, JL, Bjørklund, G, Zhao, WN, and Yin, CH. Serum copper and zinc levels in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Neuroreport. (2014) 25:1216–20. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000251

38. Shearer, TR, Larson, K, Neuschwander, J, and Gedney, B. Minerals in the hair and nutrient intake of autistic children. J Autism Dev Disord. (1982) 12:25–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01531671

39. Adams, JB, Holloway, CE, George, F, and Quig, D. Analyses of toxic metals and essential minerals in the hair of Arizona children with autism and associated conditions, and their mothers. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2006) 110:193–210. doi: 10.1385/BTER:110:3:193

40. Wecker, L, Miller, SB, Cochran, SR, Dugger, DL, and Johnson, WD. Trace element concentrations in hair from autistic children. J Ment Defic Res. (1985) 29:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1985.tb00303.x

41. Guo, M, Li, L, Zhang, Q, Chen, L, Dai, Y, Liu, L, et al. Vitamin and mineral status of children with autism spectrum disorder in Hainan Province of China: associations with symptoms. Nutr Neurosci. (2020) 23:803–10. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1558762

42. Sweetman, DU, O'Donnell, SM, Lalor, A, Grant, T, and Greaney, H. Zinc and vitamin a deficiency in a cohort of children with autism spectrum disorder. Child Care Health Dev. (2019) 45:380–6. doi: 10.1111/cch.12655

43. Zhang, XH, Yang, T, Chen, J, Chen, L, Dai, Y, Jia, FY, et al. Association between serum trace elements and core symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorder: a national multicenter survey. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. (2021) 23:445–50. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2101163

44. Adams, JB, Audhya, T, McDonough-Means, S, Rubin, RA, Quig, D, Geis, E, et al. Nutritional and metabolic status of children with autism vs. neurotypical children, and the association with autism severity. Nutr Metab Lond. (2021) 8:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-34

45. Babaknejad, N, Sayehmiri, F, Sayehmiri, K, Mohamadkhani, A, and Bahrami, S. The relationship between zinc levels and autism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran J Child Neurol. (2016) 10:1–9.

46. Hall, AG, King, JC, and McDonald, CM. Comparison of serum, plasma, and liver zinc measurements by AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS in diverse laboratory settings. Biol Trace Elem Res. (2022) 200:2606–13. doi: 10.1007/s12011-021-02883-z

47. Valenzuela-Zamora, AF, Ramírez-Valenzuela, DG, and Ramos-Jiménez, A. Food selectivity and its implications associated with gastrointestinal disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2660. doi: 10.3390/nu14132660

48. Liu, H, Huang, M, and Yu, X. Blood and hair copper levels in childhood autism spectrum disorder: a meta-analysis based on case-control studies. Rev Environ Health. (2023) 39:511–7. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2022-0256

49. Tabatadze, T, Zhorzholiani, L, Kherkheulidze, M, Kandelaki, E, and Ivanashvili, T. Hair heavy metal and essential trace element concentration in children with autism spectrum disorder. Georgian Med News. (2015) 248:77–82.

50. Mocchegiani, E, Giacconi, R, Cipriano, C, Muzzioli, M, Fattoretti, P, Bertoni-Freddari, C, et al. Zinc-bound metallothioneins as potential biological markers of ageing. Brain Res Bull. (2001) 55:147–53. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00468-3

51. Yasuda, H, Tsutsui, T, and Suzuki, K. Metallomics analysis for assessment of toxic metal burdens in infants/children and their mothers: early assessment and intervention are essential. Biomolecules. (2020) 11:6. doi: 10.3390/biom11010006

52. Grabrucker, AM. A role for synaptic zinc in ProSAP/Shank PSD scaffold malformation in autism spectrum disorders. Dev Neurobiol. (2014) 74:136–46. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22089

53. Lee, K, Mills, Z, Cheung, P, Cheyne, JE, and Montgomery, JM. The role of zinc and nmda receptors in autism spectrum disorders. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). (2022) 16. doi: 10.3390/ph16010001

54. Lee, EJ, Lee, H, Huang, TN, Chung, C, Shin, W, Kim, K, et al. Trans-synaptic zinc mobilization improves social interaction in two mouse models of autism through NMDAR activation. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:7168. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8168

55. Hagmeyer, S, Mangus, K, Boeckers, TM, and Grabrucker, AM. Effects of trace metal profiles characteristic for autism on synapses in cultured neurons. Neural Plast. (2015) 2015:985083. doi: 10.1155/2015/985083

56. Skogheim, TS, Weyde, KVF, Engel, SM, Aase, H, Surén, P, Øie, MG, et al. Metal and essential element concentrations during pregnancy and associations with autism spectrum disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. Environ Int. (2021) 152:106468. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106468

Abbreviations

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CI, confidence interval; DSM, diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders; ICD-10, international classification of diseases-10; ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Keywords: zinc deficiency, autism spectrum disorder, children, adolescents, meta-analysis

Citation: Liu H, Chen J, He J and Li X (2025) Association between zinc status and autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of case–control studies. Front. Nutr. 12:1710999. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1710999

Edited by:

Ismael San Mauro Martín, CINUSA Group, SpainReviewed by:

Andreas Martin Grabrucker, University of Limerick, IrelandAndrew Hall, University of California, Davis, United States

Copyright © 2025 Liu, Chen, He and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuening Li, eG5pbmdsaUBjbXUuZWR1LmNu

Hezuo Liu1

Hezuo Liu1 Ji Chen

Ji Chen Xuening Li

Xuening Li