- 1School of Nursing, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States

- 2School of Nursing, Molloy University, Rockville Centre, NY, United States

- 3Department of the Sciences of Public Health, Nursing & Pediatrics, University of Turin, Piedmont, Italy

1. Introduction

Agricultural work is the most hazardous and grueling area of employment open to youth in the United States of America (US) (1–3). Farming is the only work setting where youth of all ages are legally permitted to work across all fifty states. A 2018 US Government Accountability Office study found that more than half of work-related youth fatalities occurred among youth working in agriculture (4). For most industries, the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) sets minimum standards of protection for hired workers, which individual states can exceed if they so choose. Agriculture, however, is exempted from provisions of the FLSA due to outdated exceptions from when the FLSA was enacted in 1938 (5). As a result, youth working in US agriculture are not as legally protected as youth working in other industries.

1.1. Lax federal and state child labor laws in agriculture

For all US industries excluding agriculture, the basic minimum age for employment is 16, employment under 14 is prohibited and 14- to 15-year-old youth can only work limited hours in certain occupations (6, 7). Under federal law, hired workers under 12 years old may legally work in agriculture with no limits on hours worked per day or days worked per week (8). The FLSA agricultural exemptions permit youth working on farms to do work that the US Department of Labor has deemed “particularly hazardous … or detrimental to their health or wellbeing” at younger ages than working youth in other industries (9). Youth workers in agriculture can engage in these hazardous occupations and perform dangerous tasks at 16 years old while workers in all other industries must be 18 years old to do similarly hazardous work (6, 10). Without the legal redress afforded to all other working youth, those working on farms are not guaranteed overtime pay, leading employers to give them longer hours. These young, hired workers in agriculture experience interruptions in their education and risk serious preventable injury, illness, or death from exposure to heat, chemicals, hazardous machinery, and environmental perils, all of which can cause deleterious health effects leading to life-long, negative consequences for their health and wellbeing.

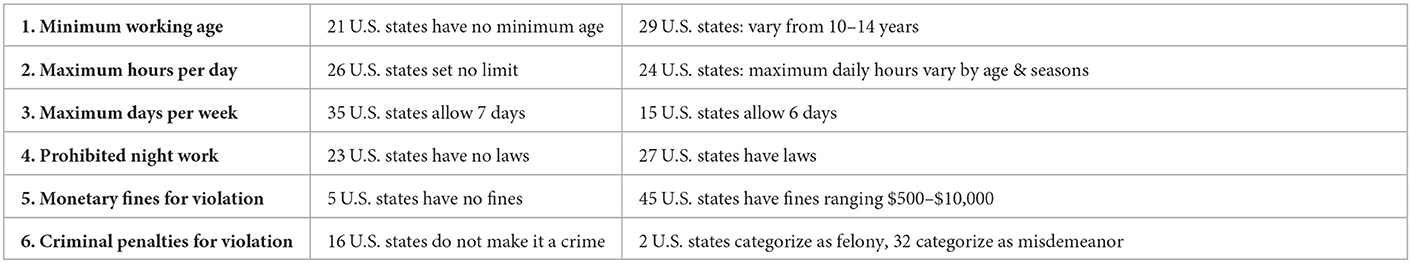

As a result of these lax federal standards, the fifty individual states have significant discretion to provide—or fail to provide—legal protections for young, hired workers in agriculture. Laws can vary from state to state, but most states' laws do not set more stringent standards than the FLSA does for young, hired workers in agriculture—and those that do are still more permissive than the FLSA is for other industries. Just a taste: 21 states permit youth of any age to work in agriculture, and age minimums in the other 29 states vary from 10 to 14 years old; 26 states set no limit on the maximum number of hours hired youth can work each day; 35 states allow hired youth to work seven days a week, while the other 15 states only require a single day off; and 23 states have no laws prohibiting hired youth from working nights. Levels and severity of enforcement vary even more between states: five states have no fines for violations, while, in the other 45 states, fines range from $500 to $10,000; furthermore, 34 states categorize violations as criminal acts, with 32 categorizing violations as misdemeanors, i.e., a criminal offense punishable with imprisonment for up to 364 days, and only two states categorizing them more severely as felonies, i.e., criminal offenses punishable with imprisonment for 365 days or longer (11, 12) (Table 1).

1.2. Negative health consequences for young, hired workers in agriculture

US laws and policies currently governing child labor leave young hired workers in agriculture unprotected. There is no official nationwide data for children younger than 18 years old who work in agriculture. In a report released in October 2021, the Child Labor Coalition and Lawyers for Good Government estimated that, in the US, 330,000 children younger than 16 years old—including over 80,000 children younger than 10 years old—are hired workers in agriculture (12). The most recent Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey reported approximately 600,000 youth younger than 18 years old (approximately 15% younger than 10 years old, 46% between 10 and 15 years old, and 39% either 16 or 17 years old) working on farms across the US (13). In addition to educational disruption, these young agricultural workers are exposed to many occupational health risks with both short- and long-term consequences, including respiratory disease, neurotoxicity, pesticide toxicity, heat illness, musculoskeletal injuries, traumatic injuries, dermatological injuries, discrimination, and sexual harassment. Youth working on US tobacco farms incur the added risk of exposure to nicotine, a known neurotoxin. These risks are severe and widespread (13–44). Approximately 33 children are injured daily in agriculture (45). On average, one child dies in an agriculture-related incident every 3 days (2). Since 2000, young, hired workers have been killed in agriculture-related incidents in at least 49 states. From 2001 through 2015, 48% of all fatal injuries to young, hired workers occurred in agriculture (3).

But these statistics are all lower-bound estimates of the true figures. Researchers estimate that over 90% of young, hired workers in agriculture are persons of color, typically seasonal migrant Latinx. These youth often work in agricultural settings that either elude or are not subject to the surveillance and data collection procedures of the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; substantial numbers of young, hired workers in agriculture will therefore not be included in the best-available federally supplied data (46).

1.3. US law does not align with international standards

The outdated US agriculture child labor policy and legal regulatory framework is weak and compromising. It does not align with international labor law and global measures to protect the health and safety of children. The International Labor Organization (ILO) as well as other advocates for working children worldwide including the United Nations Children's Fund and Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) establish policy and sustain efforts to eradicate employment that compromises children's opportunities for good health, education, and future potential. The CRC, which the US signed, defines a child as a person under the age of 18 (47). Article 32 states that children are to be protected from economic exploitation and from work that is likely to be hazardous, to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child's health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development (47). The ILO's Convention No. 138 on Minimum Ages to Employment and Work provides the normative rule of international law and defines unlawful child labor as involving any individual younger than 18 years old doing hazardous work, any individual younger than 15 years old doing any other work other than light work, or any individual younger than 13 years old doing even light work (48). This definition was expanded by ILO Convention No. 182, ratified by the US, functionally defining child labor as work that is inappropriate for a child's age, that prevents a child from benefiting from compulsory education, or that is likely to harm a child's health, safety or morals and hinder his or her development and future livelihood (49, 50). The ILO has strongly urged the US government on multiple occasions to address the gaps compromising the health and wellbeing of youth working in US agriculture (50).

2. Discussion

There is much that can and should be done to help these youth. Researchers and academics can use the methodologies of legal epidemiology—the scientific study and deployment of law as a factor in the causation, distribution and prevention of disease and injury in a population—to better inform much-needed changes in policy (51–53). By considering child labor policy and law—as well as workplace environments they create—as social determinants of health, researchers can evaluate differences between state laws regulating young, hired workers in agriculture as a potential contributing factor to health outcomes for these youth. There are large gaps, both in epidemiological data-collection and in our current understanding of the causal links between state child labor laws and injuries and fatalities among young, hired workers in agriculture. Filling in these gaps is crucial for effective changes in policy: policy makers will not only be better informed of the magnitude of the issue but also better positioned to implement more effective changes.

At the very least, however, the outdated agricultural loopholes in the FLSA must be closed. At the federal level, the proposed Children's Act for Responsible Employment, also known as the CARE Act, would do just that: among other things, it would raise the minimum age for especially hazardous work from 16 to 18 years old and prohibit any agricultural work, except on family farms, by anyone younger than 14 years old (53–59). The CARE Act was originally proposed in Congress in 2009 and, despite being reintroduced several times, it has regrettably still not been passed (54–60). Another important legislative attempt to target US tobacco farms specifically is the Children Don't Belong on Tobacco Farms Act, which would prohibit employment of youth younger than 18 years old in tobacco-related agriculture. The bill was first introduced in Congress in 2015 and, though it has also been repeatedly reintroduced, has not been passed (61). But states do not need to wait for Congress to act—they can change their own laws at any time to bring child labor protections for agriculture in line with those for other industries. Whether change comes from the federal level or individual states, it is clear that change is needed. Young hired workers in agriculture are among the most vulnerable and marginalized populations in the US, and they are in dire need of legal protection.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank John Usseglio, MPH, Informationist at the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY, United States for his time and guidance.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Hendricks KJ, Hendricks SA, Layne LA. A national overview of youth and injury trends on U.S. farms, 2001-2014. J Agric Saf Health. (2021) 27:121-134. doi: 10.13031/jash.14473

2. Perritt KR, Hendricks K, Goldcamp E. Young worker injury deaths: a historical summary of surveillance and investigative findings. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2017).

3. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries microdata. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (2019).

4. US Government Accountability Office. Working children: federal injury data compliance strategies could be strengthened. US Government Accountability Office. (2018) 27–28. Available online at: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-26.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022).

5. United States Department of Labor. Reference guide to the fair labor standards act. (2022). Available online at: https://www.dol.gov/whd/regs/compliance/hrg.htm (accessed August 15, 2022).

11. United States Department of Labor. State child labor laws applicable to agricultural employment - historical tables. (2022). Available online at: https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/state/child-labor/agriculture/history (accessed August 15, 2022).

12. Lawyers for Good Government, Child Labor, Coalition,. Child farmworkers: young, vulnerable, unprotected. (2021). Available online at: https://www.lawyersforgoodgovernment.org/child-farmworker-report (accessed August 15, 2022).

13. Arcury TA, Arnold TJ, Quandt SA, Chen H, Kearney GD, Sandberg JC, et al. Health and occupational injury experienced by Latinx Child Farmworkers in North Carolina, USA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 17:248. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010248

14. Arnold TJ, Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Mora DC, Daniel SS. Structural Vulnerability and Occupational Injury among Latinx Child Farmworkers in North Carolina. New Solutions. (2021) 31:125–140. doi: 10.1177/10482911211017556

15. Arnold TJ, Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Quandt SA, Talton JW, Mora DC, et al. Heat-related illness among latinx child farmworkers in North Carolina: A mixed-methods study. New Solutions. (2020) 30:111–26. doi: 10.1177/1048291120920571

16. Arcury TA, Arnold TJ, Sandberg JC, Quandt SA, Talton JW, Malki A, et al. Latinx child farmworkers in North Carolina: study design and participant baseline characteristics. Am J Ind Med. (2018) 62:156–67. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22938

17. Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Latino Farmworkers in the Eastern United States: Health, Safety and Justice. Cham: Springer (2009).

18. Arcury TA, Norton D, Preisser JS, Quandt SA. The Incidence of Green Tobacco Sickness among Latino Farmworkers. J Occupat Environ. (2001) 43:601–9. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200107000-00006

19. Arcury TA, Quandt SA, Preisser JS. Predictors of incidence and prevalence of green tobacco sickness among Latino farmworkers in North Carolina, USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2001) 55:818–24. doi: 10.1136/jech.55.11.818

20. Arcury T, Bernert J, Norton D, Preisser J, Quandt S, Wang J. High levels of transdermal nicotine exposure produce green tobacco sickness in Latino farmworkers. Nicotine Tobacco Res. (2003) 5:315–21. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000094132

21. Arcury TA, Vallejos QM, Schulz MR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Verma A, et al. Green Tobacco Sickness and Skin Integrity among Migrant Latino Farmworkers. Am J Ind Med. (2008) 51:195–203. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20553

22. Arcury TA, Arnold TJ, Mora DC, Sandberg JC, Daniel SS, Wiggins MF, et al. “Be careful!” Perceptions of work-safety culture among hired Latinx child farmworkers in North Carolina. Am J Ind Med. (2019) 62:1091–1102. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23045

23. Baker RB, Blanchette J, Eriksson K. Long-Run impacts of agricultural shocks on educational attainment: evidence from the boll weevil. J Econ History. (2020) 80:136–74. doi: 10.1017/S0022050719000779

24. Bartels S, Niederman B, Water TR. Job hazards for musculoskeletal disorders for youth working on farms. J Agric Saf Health. (2000) 6:191–201. doi: 10.13031/2013.1913

25. Bhattacharyya S, Bhattacharyya R, Sanyal D, Chakraborty K, Neogi R, Banerjee BB. Depression, sexual dysfunction, and medical comorbidities in young adults having nicotine dependence. Indian J Commun Med. (2020) 45:295. doi: 10.4103/ijcm.IJCM_153_19

26. Burke RD, Todd SW, Lumsden E, Mullins RJ, Mamczarz J, Fawcett WP, et al. Developmental neurotoxicity of the organophosphorus insecticide chlorpyrifos: from clinical findings to preclinical models and potential mechanisms. J Neurochem. (2017) 142:162–77. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14077

27. Castillo DN, Adekoya N, Myers JR. Fatal work-related injuries in the agricultural production and services sectors among youth in the United States, 1992-96. J Agromedicine. (2000) 6:27–41. doi: 10.1300/J096v06n03_04

28. Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. (2014) 13:330–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3

29. Human Rights Watch (2014). Tobacco's hidden children: Hazardous child labor in United States tobacco farming. Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/13/tobaccos-hidden-children/hazardous-child-labor-united-states-tobacco-farming (accessed March 29, 2022).

30. Human Rights Watch,. Fingers to the Bone: United States Failure to Protect Child Farmworkers. 2, (2009). Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/frmwrkr/ (accessed August 15, 2022).

31. Human, Rights Watch. Fields of Peril: Child Labor in US Agriculture (New York: Human Rights Watch, May 2010), Available online at: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/crd0510webwcover_1 (accessed August 15, 2022).

32. Leslie FM. Multigenerational epigenetic effects of nicotine on lung function. BMC Med. (2013) 11:1–4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-27

33. McCauley LA, Anger WK, Keifer M, Langley R, Robson MG, Rohlman D. Studying health outcomes in farmworker populations exposed to pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. (2006) 114:953–60. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8526

34. McCauley LA, Sticker D, Bryan C, Lasarev MR, Scherer JA. Pesticide knowledge and risk perception among adolescent Latino farmworkers. J Agric Saf Health. (2002) 8:397–409. doi: 10.13031/2013.10220

35. McKnight RH, Spiller HA. Green tobacco sickness in children and adolescents. Public Health Rep. (2005) 120:602–5. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000607

36. National Institute for Occupational Safety Health. Childhood Agricultural Injury Survey. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2014). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/childag/cais/demotables.html (accessed August 15, 2022).

37. Nour MM, Field WE, Ni J-Q, Cheng Y-H. Farm-related injuries and fatalities involving children, youth, and young workers during manure storage, handling, and transport. J Agromedicine. (2021) 26:323–33. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2020.1795034

38. Quandt SA, Arnold TJ, Mora DC, Sandberg JC, Daniel SS, Arcury TA. Hired Latinx child farm labor in North Carolina: The demand-support-control model applied to a vulnerable worker population. Am J Ind Med. (2019) 62:1079–90. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23039

39. Valentine G, Sofuoglu M. Cognitive effects of nicotine: recent progress. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2018) 16:403–14. doi: 10.2174/1570159X15666171103152136

40. Weichelt B, Scott E, Burke R, Shutske J, Gorucu S, Sanderson W, et al. What about the Rest of Them? Fatal Injuries Related to Production Agriculture Not Captured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI). J Agromedicine. (2022) 27:35–40. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2021.1956663

41. Weichelt B, Gorucu S, Murphy D, Pena AA, Salzwedel M, Lee BC. Agricultural Youth Injuries: A Review of 2015-2017 Cases from U.S. News Media Reports. J Agromedicine. (2019) 24:298–308. doi: 10.1080/1059924X.2019.1605955

42. Weichelt B, Salzwedel M, Heiberger S, Lee BC. Establishing a publicly available national database of US news articles reporting agriculture-related injuries and fatalities. Am J Ind Med. (2018) 61:667–74. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22860

43. Wiggins MF, Daniel SS. Health and occupational injury experienced by latinx child farmworkers in North Carolina, USA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 17:248.

44. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Analyses of the 2014 Childhood Agricultural Survey. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Division of Safety Research (2016).

45. Gold A, Fung W, Gabbard S, Carrol D. Findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey (NAWS) 2019-2020: a demographic employment profile of United States farmworkers. US Department of Labor, Employment Training Administration, Office of Policy Development Research (2022) 3–5. Available online at: https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/naws/pdfs/NAWS%20Research%20Report%2016.pdf (accessed August 15, 2022).

46. Convention Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) adopted November 20 1989 G.A. Res. 44/25, annex, 44 U.N. GAOR Supp. (No 49) at 167, U.N. Doc. A/44/49. (1989), entered into force September 2, 1990, art. 32. The United States signed the CRC on February 16, 1995.

47. ILO, convention 138,. Available online at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312283:NO (accessed August 15, 2022).

48. ILO convention 182. Available online at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312327:NO (accessed August 15, 2022).

49. International Labor Organization (ILO). Convention No. 182 concerning the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labor (Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention), adopted June 17, 1999, 38 I.L.M. 1207. (entered into force November 19, 2000), ratified by the United States on December 2, 1999, art. 3.

50. International Labour Organization (ILO). Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations (CEAR), “Observation: Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) - United States (Ratification: 1999),” adopted 2012, published 102nd ILC session. (2013). Available online at: http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:13100:0::NO:13100:P13100_COMMENT_ID:3057769:NO (accessed August 15, 2022).

51. Burris S, Wagenaar AC, Swanson J, Ibrahim JK, Wood J, Mello MM. Making the case for laws that improve health: a framework for public health law research. Milbank Q. (2010) 88:169–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00595.x

52. Burris SC, Anderson ED. Legal regulation of health-related behavior: a half-century of public health law research. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci. (2013) 9:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-102612-134011

53. Burris S, Cloud LK, Penn M. The growing field of legal epidemiology. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2020) 26:S4–9. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001133

54. CARE CARE Act of 2009 H,.R. 3564, 111th Cong. (2009). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/111th-congress/house-bill/3564 (accessed August 15, 2022).

55. CARE CARE Act of 2011 H,.R. 2234, 112th Cong. (2011). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/2234 (accessed August 15, 2022).

56. CARE CARE Act of 2013 H,.R. 2342, 113th Cong. (2013). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/2342 (accessed August 15, 2022).

57. CARE CARE Act of 2015 H,.R. 2764, 114th Cong. (2015). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2764 (accessed August 15, 2022).

58. CARE CARE Act of 2017 H,.R. 2886, 115th Cong. (2017), Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/2886 (accessed August 15, 2022).

59. CARE CARE Act of 2019 H,.R. 3394, 116th Cong. (2019). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3394 (accessed August 15, 2022).

60. CARE CARE Act of 2022 H,.R. 7345, 117th Cong. (2022). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/7345 (accessed August 15, 2022).

61. Children Children Don't Belong on Tobacco Farms Act H,.R. 3229, 116th Cong. (2019). Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/3229 (accessed August 15, 2022).

Keywords: child labor, agriculture, social determinants, legal epidemiology, health outcomes, policy

Citation: Iannacci-Manasia L (2023) Unprotected Youth Workers in US Agriculture. Front. Public Health 11:1064143. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1064143

Received: 07 October 2022; Accepted: 24 January 2023;

Published: 30 May 2023.

Edited by:

Richard Franklin, James Cook University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Erika Scott, Bassett Medical Center, United StatesCopyright © 2023 Iannacci-Manasia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lisa Iannacci-Manasia, bGk0NkBjdW1jLmNvbHVtYmlhLmVkdQ==

Lisa Iannacci-Manasia

Lisa Iannacci-Manasia