Abstract

Background and importance:

Healthcare professionals face significant workloads, as their roles are among the most demanding and stressful. Resilience serves as a crucial factor in helping them cope with the challenges encountered in their work environment and effectively manage stress. Assessing the level of resilience among healthcare workers and identifying potential variations across different groups is essential for effective public health management, preventing burnout, and ultimately enhancing patient care.

Objective:

To assess the resilience of various categories of workers operating within a tertiary care multisite hospital and understanding if there are any differences in resilience, based on their characteristics, the type of department they work in, and personality traits.

Design, setting and participants:

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in January 2024 at EOC, a multi-site tertiary care hospital located in Southern Switzerland. 1,197 hospital workers answered an online survey which included: (1) an ad hoc questionnaire on personal and job characteristics, well-being-related activities, satisfaction level regarding communication, collaboration, support, and training opportunities in the workplace, (2) the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10-Item on resilience, and (3) the Big Five Personality Inventory 10-item on personality traits.

Outcome measures and analysis:

Proportion of resilient and highly resilient individuals within the various categories of workers were analyzed with Bayesian approach and Bayesian robust regression.

Main results:

Being part of the hospitality staff, working as a doctor, and having a male sex were associated to the highest scores of resilience. Surgery and emergency departments had the highest proportion of highly resilient individuals. Male sex, older age, seniority, higher hierarchical rank, engagement in physical activities, relaxation or mindfulness practices, religiosity, perception of good collaboration, communication, support, and physical activity correlated with higher resilience skills.

Conclusion:

This cross-sectional study found that physicians and hospitality staff within our multi-site Swiss hospital are more resilient compared to other categories of hospital workers, and among departments, those working in surgery and Emergency Medicine. Enhancing our comprehension of resilience is crucial for more precise management of healthcare systems and the development of employment policies aimed at sustaining the capacity of healthcare systems to serve patients effectively, while also mitigating shortages of healthcare professionals.

Introduction

Resilience reflects the ability to bounce back after adversity (1–3). It is a dynamic process that can evolve over the course of life and vary depending on the circumstances (1, 4).

It correlates with mental health and well-being (5) as well as with work performance (6) and is influenced by both individual factors (such as personality traits and socioeconomic status) (7, 8) and other variable factors. These variable factors, which can be cultivated, encompass demographic characteristics (such as age, marital status, and level of education), practices of relaxation or mindfulness, engagement in physical activity, as well as aspects of well-being such as sleep quality, work-life balance, and the availability of social support (4, 9–17).

In the workplace, effective collaboration and communication within the team, coupled with organizational factors (favorable shifts, adequate staffing, etc.) and opportunities for teaching technical and non-technical skills, are known to foster resilience. This is particularly true for healthcare workers (4, 18–23).

Healthcare workers are a highly at-risk category to adversities and stressful/traumatic condition, both acutely and chronically, due to their constant exposure to people sufferance, necessity of rapidly responding to requests for help, and the possibility of severe adverse disease outcomes (24).

In recent years, there has been a noticeable shortage of healthcare professionals across all high-income nations, primarily due to many doctors and nurses leaving the profession. The trend is primarily driven by high rates of burnout and challenges in balancing work and personal life. While the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate change related events may have exacerbated this situation, early signs of these issues were present prior to their occurrence (24–33).

This has prompted the proposal and development of various interventions aimed at supporting healthcare staff in self-care and also adjustments in medical education programs (25, 29, 34, 35).

For these reasons, resilience emerges as a highly desirable characteristic in healthcare staff, as it may serve as a protective factor against abandoning the profession.

There is limited and fragmented literature on the resilience levels of healthcare personnel, often encompassing only some aspects of this complex construct (4, 19, 20, 22, 23, 33, 36, 37).

Indeed in some healthcare sector a higher level of intrinsic resilience seems to be necessary. For instance, critical care or surgery departments have the highest rates of workers burnout (24, 37–40).

In line with the demand-resources job model (28), these departments entail high demands (night and weekend shifts, highly stressful and emotional situations) while resources remain similar to those available to other healthcare professionals (12).

There is, however, only little information on this topic (37, 41) and there is not a clear understanding of the level of resilience required for these roles. Understanding of clinician resilience has predominantly stemmed from convenience samples of organizations and clinicians, frequently through surveys targeting either physicians or nurses exclusively.

A hospital is a unique environment where various categories of workers, not just healthcare providers, coexist, allowing for potential differences to be assessed based on job type. Within the same setting, there are roles that inherently require the ability to handle extreme situations, while others do not. Despite numerous confounding factors, several variables such as differences in location, administration, and working conditions are eliminated.

Aim of this study was to assess whether there are differences in resilience among various categories of workers within a hospital, and among healthcare providers.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

This cross-sectional study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol underwent review and was deemed exempt by the Ethical Committee of Canton Ticino and the participating hospitals. Participants were invited via email to take part and provided with information regarding the study’s objectives, design, voluntary participation, and the confidentiality of responses. Completion of the survey implied explicit informed consent as participants had to express their consent before starting the questionnaire and it was impossible to fill it in without giving explicit consent. The questionnaire was anonymous: inserting personal data that could lead to individual identification was not required and the responses were only visible to investigators. The study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines for cross-sectional studies.

Study design, data collection, and sample

The participants were employees of EOC (Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale), a multi-site hospital located in Canton Ticino, southern Switzerland. EOC comprises three hospitals spread across three different cities, all operating under a unified administration. These hospitals encompass all surgical and medical specialties, as well as critical care area, that is Emergency Department (ED), anaesthesia, intensive care units.

Data collection took place between the 23rd of January and the 6th of February, 2024.

The study entailed the distribution via email of electronic surveys completed by 1,197 respondents (out of 3,907 individuals invited via email), resulting in a response rate of 30% (specific rate for physicians 43% - 277/634, nurses 35% - 455/1283, administrative personnel 38% - 203/567, technical personnel 20% - 137/654, hospitality staff 21% - 54/249, medical practice assistants 15% - 50/322, other 10% - 21/198). Attendance was voluntary and anonymous.

Each respondent completed a three-part questionnaire: the first part (see Supplementary material) was an informative part in which subsequent data was collected:

-

Biographical data (age, gender, marital status).

-

Job-related data (profession, department, seniority, hierarchical role).

-

Well-being related data (physical activity; religiosity; mindfulness or other meditation/relaxation practices).

-

Job satisfaction data (satisfaction with time-schedule; perceived collaboration, communication and support by colleagues, work-life balance).

-

Data on continuing education (organization of sessions, debriefings).

The second and third part consisted of two validated questionnaires: the Italian version of CD-RISC 10 (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) (42) and the Italian version of BFI-10 (Big Five Inventory) (43), which assessed resilience and personality traits, respectively.

Measure of resilience

The CD-RISC 10 (42) is a tool used to measure resilience, primarily focusing on hardiness. It comprises 10 statements that reflect various aspects of resilience:

Flexibility (items 1 and 5).

Sense of self-efficacy (items 2, 4, and 9).

Ability to regulate emotion (item 10).

Optimism (items 3, 6, and 8).

Cognitive focus/maintaining attention under stress (item 7).

Each statement is rated on a five-point scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicates the statement is not true at all and 4 indicates it is true nearly all the time. The total score is obtained by summing up all 10 items, resulting in a score ranging from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate greater resilience, while lower scores suggest less resilience or more difficulty in bouncing back from adversity.

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale is one of the most widely used resilience scales in literature. Initially developed for patients with mental disorders, particularly PTSD and anxiety, it has subsequently been demonstrated to have convergent and discriminant validity and reliability across multiple nationalities and populations (12, 44).

The Italian version of the CD-RISC 10 has good psychometric properties, namely reliability and validity, as detailed in the original article (45).

The scale may be insensitive in detecting very high levels of resilience due to a “ceiling effect” toward the upper end. On the other hand, if discrete levels of resilience are detected toward the upper end, the data is reliable (46).

Analysis of personality traits

The BFI-10 is widely represented in studies focusing on personality and resilience. There are many studies that use it to assess which personality traits are associated with greater resilience (46, 47). Specifically, it appears that neuroticism is negatively correlated with this characteristic, while the other four personality traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience) are linked to higher levels of resilience.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using several open-source Python packages, including “Bambi,” “Pandasql,” “NumPy,” “PyMC,” “Seaborn,” “Notebook” and “Matplotlib,” with versions 0.13.0, 0.7.3, 1.25.2, 5.10.3, 0.13.2, 7.0.7 and 3.8.2, respectively, on Mac OS 13.4.1. Statistical significance was determined based on highly credible intervals of parameter estimates, with confidence intervals (CI) calculated at 95%.

A Bayesian approach was employed, with uninformative priors, which does not suffer from the sample size limitations inherent in frequentist methods relying on asymptotics. The Bayesian approach addresses uncertainty by generating wider confidence intervals: narrower when data are abundant and wider when data are scarce. Statistical significance is indicated if the confidence intervals of two different subgroups (e.g., young vs. old) do not overlap, as observed in the second communication study (48).

To assess potential differences in resilience among the various groups under examination, we considered participants with high resilience scores (36–40, fourth quartile) and those with low resilience scores (0–25, first quartile) in the various profession and departments.

We then analyzed this highly resilient subjects with respect to all the variables examined.

To assess the solidity of our findings across different model specifications we conducted a Bayesian robust regression analysis, with the goal of assessing credible intervals for each parameter and evaluating the direction of their overall contribution to the CD-RISC 10 score.

We also performed a similar Bayesian regression analysis to determine potential influence of various personality traits on resilience.

Results

The total sample comprised 1,197 participants, 842 (70.3%) female and 355 (29.7%) male subjects, all collaborators of EOC. The response rate was 28% (1,197/4275 emails sent).

Table 1 describes the responses given with mean CD-RISC score.

Table 1

| Participants (1197) | No. | % | CD-RISC mean score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male Female |

355 842 |

29.7 70.3 |

31.6 30.4 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single Not single |

376 821 |

31.4 68.6 |

30.8 30.6 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 18–25 26–30 31–35 36–40 41–45 46–50 51–55 56–60 >60 |

50 151 205 171 167 143 150 104 50 |

4.2 12.6 17.1 14.3 14 11.9 12.5 8.7 4.7 |

30.1 30.0 30.3 29.8 31.0 31.5 31.7 31.2 31.3 |

| Seniority (years) | |||

| 0–5 6–10 11–15 16–20 >20 |

278 237 180 152 350 |

23.2 19.8 180 152 3.9 |

30.4 30.2 30.5 30.4 31.6 |

| Role (hierarchy) | |||

| Executive Manager Worker |

168 322 707 |

14 26.9 59 |

33.2 30.9 29.9 |

| Profession | |||

| Nurse Physician Hospitality staff Administrative staff Technical staff Medical assistant Other |

455 277 54 203 137 50 21 |

38 23.1 4.5 16.9 11.4 4.1 1.7 |

30.6 31.8 31.7 30.6 30.3 30.0 29.6 |

| Department | |||

| Administration Services Outpatient Surgery Critical Area Internal Medicine Other |

203 168 108 172 253 255 38 |

21.1 14 9 14.3 21.1 21.3 3.1 |

31.4 30.0 30.5 31.8 31.2 30.5 28.6 |

| Physical activity (times per week) | |||

| 0–1 2–3 4–5 >5 |

669 429 76 23 |

55.8 35.8 6.3 1.9 |

30.2 31.2 32.1 32.7 |

| Quality of sleep | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

152 264 397 283 101 |

12.7 22.0 33.1 23.6 8.4 |

30.0 29.5 30.4 31.9 33.2 |

| Religiosity | |||

| 1 - Not religious at all 2 3 4 5 - Very religious |

480 284 236 119 78 |

40.1 23.7 19.7 9.9 6.5 |

30.6 30.7 30.5 30.9 32.2 |

| Meditation/relaxation practice | |||

| Never Seldom Sometimes Often Very often |

152 264 397 283 101 |

12.6 22 33.1 23.6 8.4 |

30.6 30.2 30.9 32.3 32.0 |

| Mindfulness practice | |||

| Never Seldom Sometimes Often Very often |

855 151 117 58 16 |

71.4 12.6 9.7 4.8 1.3 |

30.4 31.0 31.6 32.7 32.9 |

| Collaboration with colleagues | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

24 82 307 576 224 |

2 6.8 25.6 48.1 18.7 |

29.8 28.8 29.5 31.1 32.2 |

| Communication with colleagues | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

24 109 371 524 169 |

2 9.1 30.9 43.7 14.1 |

30.5 28.9 30.0 31.1 32.7 |

| Support/respect from colleagues (same Dept) | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

24 83 273 529 288 |

2 6.9 22.8 44.2 24.0 |

30.2 28.4 29.6 30.9 32.2 |

| Support/respect from colleagues (other Dept) | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

37 138 418 479 125 |

3.1 11.5 34.9 40.0 10.4 |

28.4 28.6 29.6 31.8 33.7 |

| Work-life balance | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

90 251 401 337 118 |

7.5 20.9 33.5 28.1 9.8 |

31.9 30.5 30.7 31.6 33.5 |

| Technical training | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

147 296 366 280 108 |

12.2 24.7 30.5 23.4 9 |

30.5 29 30.7 31.6 33.5 |

| Non technical training | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

204 313 351 259 70 |

17 26.1 29.3 21.6 5.8 |

29.8 29.9 31.0 31.5 32.9 |

| Organisation of debriefings | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

220 287 311 257 122 |

18.3 23.9 25.9 21.4 10.1 |

30.3 29.6 30.9 31.2 32.6 |

| Organisation of listening moments | |||

| 1 - Very poor 2 3 4 5 - Very good |

239 296 324 238 100 |

19.9 24.7 27 19.8 8.3 |

30.2 29.5 31.2 31.3 33 |

Sample description.

Sample description with Connor-Davidson Reilience Scale mean score for every category.

The majority of participants were female (70.3%) and were married or in a stable relationship (68%). All ages from 18 to 65 were well represented, as were seniority and hierarchical roles. 38% of the respondents were nurses.

Male subjects, the older ones, with greater seniority and higher hierarchical rank, turned out to be more resilient. Executives seemed to demonstrate higher levels of resilience compared to both managers and workers, regardless of gender.

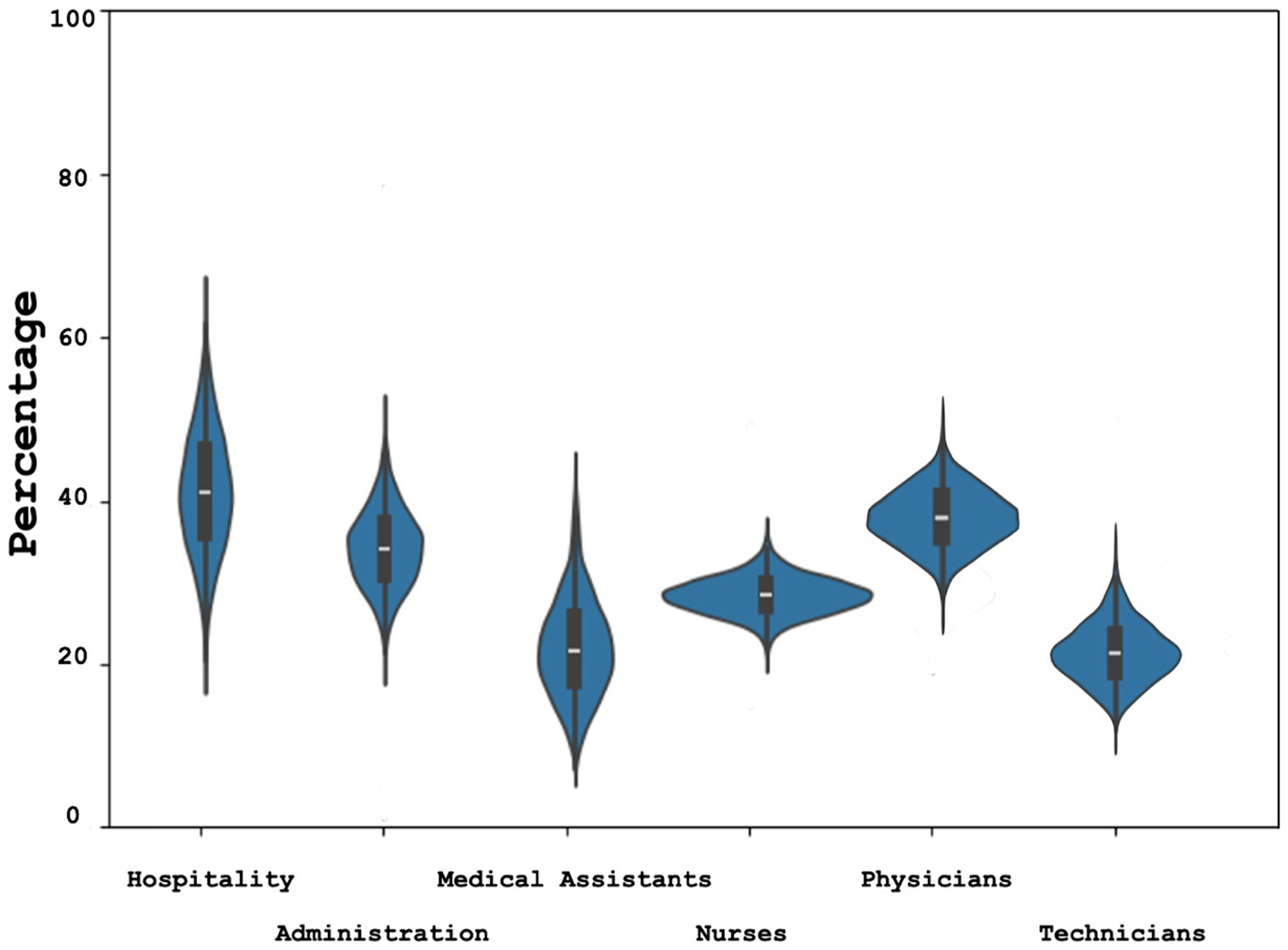

Regarding the profession practiced, respondents who belonged to the hospitality staff and physicians were found to be more resilient compared to other occupations (Figure 1). Moreover, it was observed that surgical departments and the hospitality sector were more resilient.

Figure 1

Resilience by profession Bayesian estimate (Confidence Interval) of highly resilient hospital workers estimated with CD-RISC 10 (Connor Davidson Resilience Scale 10 item) divided by profession.

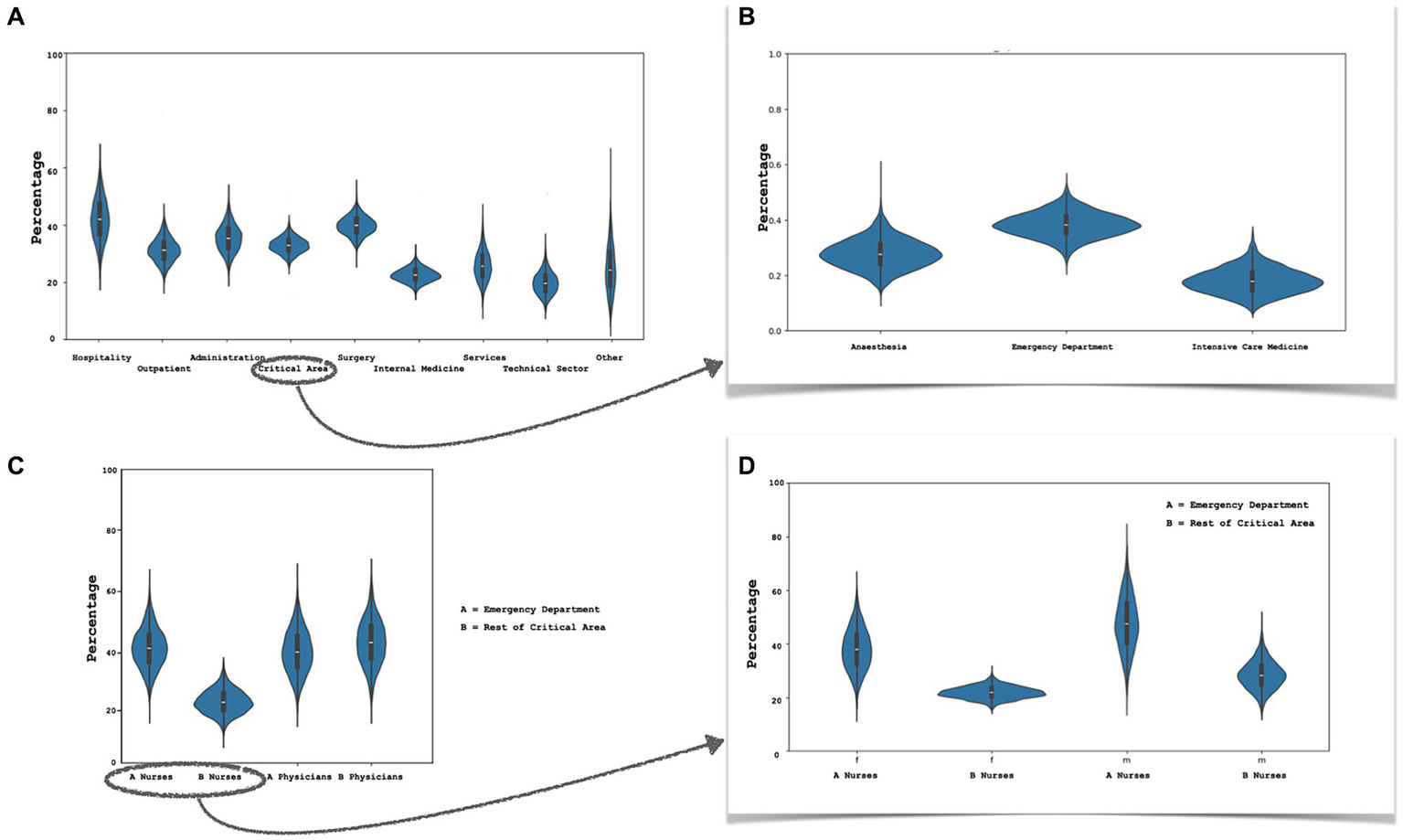

In the critical care area (emergency department, anaesthesia, intensive care), the department as a whole did not exhibit higher resilience scores. However, when the emergency department was separated, it showed more elevated levels of highly resilient subjects, comparable to those of the surgery departments and the hospitality sector (Figures 2A,B). By further segregating the various professions, it was observed that emergency department nurses displayed a higher proportion of highly resilient individuals, even after accounting for gender differences (Figures 2C,D). The difference was no longer present when considering physicians.

Figure 2

Resilience by department. (A) Bayesian estimate (confidence interval) of highly resilient hospital workers estimated with CD-RISC 10 (Connor Davidson Resilience Scale 10 item): (A) proportion of highly resilient individuals among the various departments; (B) workfers of critical area department; (C) comparison between physician and nurses of critical area department: emergency department (A) and the rest of critical area (anaesthesia + intensive care medicine) (B); (D) nurses of emergency department compared to critical area (anaesthesia and intensive care medicine) colleagues, sample divided by gender (f, females; m, males).

Analysing the factors contributing to well-being, physical activity and mindfulness were found to be associated with higher resilience scores.

The same was true for subjects who self-identified as highly religious.

Regarding collaboration, communication, and perceived support from colleagues (both within one’s own department and from other departments), as well as the opportunity for training both technical and non technical skills, these elements were also associated with higher scores on the CD-RISC.

All these differences were significant after Bayesian regression (Table 2).

Table 2

| Deviation from Intercept Mean | SD* | HDI 3% | HDI 97% | MCSE§ Mean | MCSE SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal data | Gender male | 0.936 | 0.368 | 0.225 | 1.600 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Marital status single | 0.334 | 0.334 | 0.783 | 0.472 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |

| Profession | Administrative staff | −2.046 | 1.608 | −5.135 | 0.012 | 0.029 | 0.031 |

| Medical assistant | −1.965 | 1.782 | −5.347 | 0.424 | 0.031 | 0.032 | |

| Physician | −1.001 | 1.664 | −4.181 | 0.499 | 0.030 | 0.030 | |

| Nurse | −1.714 | 1.635 | −4.806 | 0.032 | 0.030 | 0.030 | |

| Technical sector | −3.129 | 1.664 | −6.418 | −1.402 | 0.030 | 0.030 | |

| Hierarchy | Manager | −1.380 | 0.545 | −2.000 | −0.329 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Worker | −1.834 | 0.468 | −2.250 | −1.008 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| Department | Critical Area | 0.911 | 1.700 | −2.204 | 4.176 | 0.032 | 0.032 |

| Surgery | 1.794 | 1.702 | −1.274 | 5.108 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Internal Medicine | 0.709 | 1.690 | −2.418 | 3.883 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Services | 1.176 | 1.859 | −2.227 | 4.667 | 0.032 | 0.032 | |

| Technical sector | 0.560 | 1.790 | −2.869 | 3.857 | 0.031 | 0.031 | |

| Well being | Physical activity low | 0.733 | 0.335 | 0.122 | 1.376 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Physical activity medium | 1.803 | 0.651 | 0.588 | 2.995 | 0.007 | 0.005 | |

| Physical activity high | 1.290 | 1.148 | 0.858 | 3.442 | 0.011 | 0.009 | |

| Very poor quality of sleep | −0.793 | 0.549 | −1.793 | 0.289 | 0.006 | 0.005 | |

| Poor quality of sleep | 0.058 | 0.516 | −0.921 | 1.024 | 0.006 | 0.005 | |

| Medium quality of sleep | 1.363 | 0.562 | 0.274 | 2.385 | 0.007 | 0.005 | |

| High quality of sleep | 2.905 | 0.718 | 1.590 | 4.266 | 0.008 | 0.006 | |

| Very poor religiosity | 0.053 | 0.408 | −0.7 | 0.809 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| Low religiosity | −0.212 | 0.422 | −1.043 | 0.529 | 0.004 | 0.004 | |

| Medium religiosity | 0.174 | 0.558 | −0.898 | 1.215 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| High religiosity | 1.096 | 0.652 | −0.052 | 2.390 | 0.007 | 0.005 | |

| Rare relaxation/meditation | 0.326 | 0.413 | −1.100 | 0.442 | 0.004 | 0.003 | |

| Some relaxation/meditation | −0.098 | 0.499 | −0.998 | 0.863 | 0.006 | 0.004 | |

| Frequent relaxation/meditation | 0.239 | 0.746 | −1.158 | 1.650 | 0.009 | 0.007 | |

| Very frequent relaxation/meditation | −1.493 | 1.361 | −4.085 | 0.973 | 0.015 | 0.011 | |

| Rare mindfulness | 0.916 | 0.501 | −0.033 | 1.829 | 0.005 | 0.004 | |

| Some mindfulness | 0.983 | 0.617 | −0.166 | 2.163 | 0.007 | 0.005 | |

| Frequent mindfulness | 1.775 | 0.903 | 0.065 | 3.413 | 0.010 | 0.007 | |

| Very frequent mindfulness | 3.227 | 1.708 | 0.129 | 6.526 | 0.018 | 0.013 |

Bayesian robust regression analysis.

SD, standard deviation.

HDI, highest density interval.

MCSE, Monte Carlo standard error.

Missing values are the intercept.

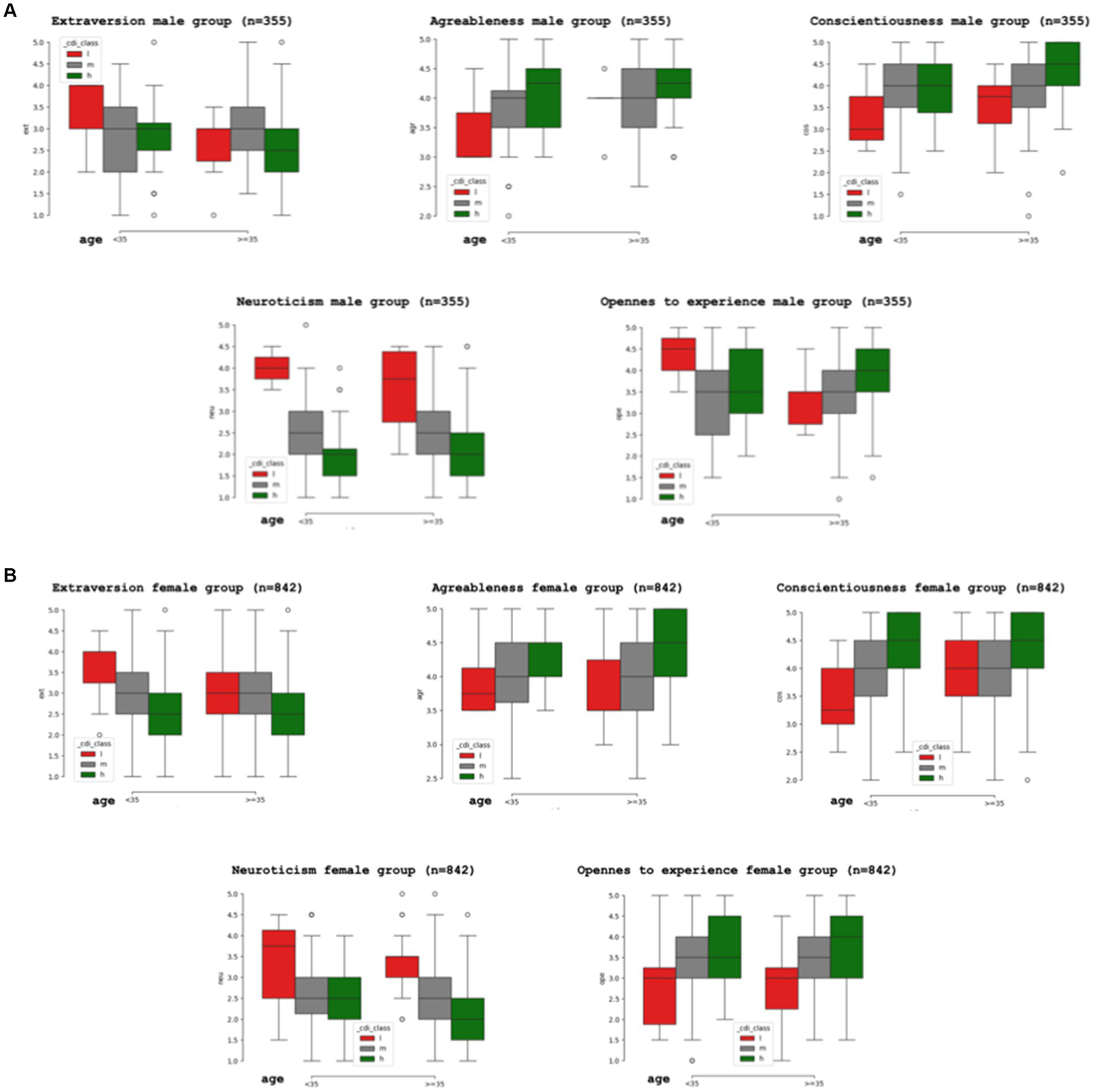

The examination of specific personality traits using the BFI-10 indicated that agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness were positively linked with higher resilience, whereas for neuroticism and extraversion there was a negative association, more pronounced for neuroticism.

Since the reference values of the BFI-10 differ for subjects ≤35 years and those over 35 years old, calculations were conducted separately for the two age groups. The participants were segregated by gender due to the higher resilience reported in the male group. Figures 3A,B illustrate the distribution of scores for different personality traits in the male (Figure 3A) and female (Figure 3B) populations, correlated with high (CD-RISC 10 score 35–40), medium (CD-RISC 10 score 25–34), and low (CD-RISC 10 score 0–25) levels of resilience.

Figure 3

Resilience by gender. (A) Proportion (confidence interval) of high (h), medium (m) and low (l) resilience male individuals linked to personality traits assessed with the BFI-10 (Big Five Inventory 10 item): agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience are associated with higher resilience, neuroticism and extraversion are negatively linked to resilience. (B) Proportion (confidence interval) of high (h), medium (m) and low (l) resilience female individuals linked to personality traits assessed with the BFI-10 (Big Five Inventory 10 item): agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience are associated with higher resilience, neuroticism and extraversion are negatively linked to resilience.

Discussion

In this study, we offer comprehensive evidence of difference in terms of score of the CD-RISC 10 scale and proportion of highly resilient individuals among hospital collaborators based on a large sample of respondents.

Being part of the hospitality staff or working as a doctor, was associated to the highest levels of resilience. Surgery and emergency departments had the highest proportion of highly resilient individuals. Male sex, older age, seniority, higher hierarchical rank, engagement in physical activities, relaxation or mindfulness practices, religiosity, perception of good collaboration, communication, social support, and physical activity correlated with higher resilience skills. The examination of specific personality traits using the Big Five Inventory 10 item (BFI-10) indicated that agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness were positively linked with higher resilience, whereas for neuroticism and extraversion there was a negative association, more pronounced for neuroticism.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing resilience skills on a large sample of hospital workers which includes all job categories and finding that physicians, hospitality staff, and people working in the Emergency Department and Surgery Department are the most resilient hospital workers.

Men appear to be more resilient than women and this in agreement with the literature (49, 50). It’s not clear why this occurs, but it’s known that the stress response differs between males and females, and that women have a higher rate of burnout and anxiety (26, 51). The mechanism with which this happen is obscure, as resilience neural circuits have been only partially identified, with the majority of studies performed on male subjects (52). In a study conducted on rodents, the Authors show how neural reactions are different between male and female subjects (51).

Age, seniority and hierarchical role are predictors of superior resilience, as expected (4, 6, 9, 22). Aging is synonymous with adaptation and experience, not only with senescence (49). At the same time, those who have stayed in a specific position for an extended period and those in leadership roles have likely found the resources to do so, and consequently, they are likely self-selected as more resilient.

Interestingly in our sample there was no statistical difference between male and female executives (females being far less numerous than males).

Hospitality staff and physician were found to be more resilient in comparison to other professionals. There are few studies in the literature on healthcare staff, and even fewer deal with hospitality sector. In particular, the hospitality sector has only recently been studied in relation to the forced closures implemented by numerous governments during the COVID-19 pandemic (52). To become a physician and work in a hospital requires many years of study, while working in the hospitality sector of a health facility means doing humble work, often under-appreciated even by the hospital’s own staff. In both cases, a high level of motivation is required, and perhaps this is why these two categories stand out in the resilience ranking.

It’s possible that motivation also plays a significant role in the presence of highly resilient individuals within emergency departments: working 24/7, overcrowding, and highly stressful situations are part of everyday life, and individuals who are unmotivated or less resilient are not easily found in such environments (53). Unfortunately, we did not assess the motivational aspects and work engagement of our respondents.

Well-being, physical activity and mindfulness as well as the perceived presence of good communication, collaboration and social support among co-workers were all factors that were associated to higher levels of resilience: given that resilience can be nurtured (18, 20–23) clinics’ and hospitals’ administrations should be very attentive to these aspects and develop programs that include a caring vision not only for patients but also for the staff (34, 35, 54). This necessitates a cultural shift that is just starting to emerge within the healthcare sector.

In addition, fostering resilience should involve organising an adequate array of technical and non-technical skills training activities, both of which have been linked in this study to higher resilience scores. Even in this field, studies in the literature are scarce. In this 2022 study (55) involving 111 nursing students, the authors were able to identify a correlation between non-technical skills training and increased resilience, but further studies are needed to confirm the validity of these results.

Finally, there is an evident link between personality traits and resilience, already known in the literature (46) and confirmed by this study, notably the negative correlation with neuroticism (or emotional instability). This highlights implications for both the selection of personnel and the provision of psychological support for healthcare workers.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations:

This paper is based solely on a Swiss context. It is necessary to expand the sample and include other countries in order to generalize the results.

We did not assess the dynamic aspect of resilience but merely provided a snapshot. It would be advisable to consider evaluating the longitudinal trends in the future.

The aspect of work engagement was not assessed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this represents the first study that compares various professionals working within the same organization, providing statistically robust data in support of the findings.

The results have implications for enhancing worker resilience, guiding the selection of human resources within a hospital setting, maintaining quality of patients’ care, and stimulating a culture that makes leadership positions accessible to women as well.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the Comitato Etico Cantonale Canton Ticino for the studies involving humans because Comitato Etico Cantonale Canton Ticino. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LU: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. IM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SS: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SU: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work of SU is supported by the #NEXTGENERATIONEU (NGEU) and funded by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), project MNESYS (PE0000006)—A Multiscale integrated approach to the study of the nervous system in health and disease (DN. 1553 11.10.2022).

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our gratitude to Lorenzo Emilitri for his invaluable contribution to the statistical analysis of our data. Without his expertise, this work would not have been possible. Additionally, we extend our thanks to Monica Ghielmetti, Lorenzo Fauth, Simona Minotti, Cristina Sommacal, and Claudia Vascon from the human resources departments of the three hospitals within EOC for their support in conducting the survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1403721/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Aburn G Gott M Hoare K . What is resilience? An integrative review of the empirical literature. J Adv Nurs. (2016) 72:980–1000. doi: 10.1111/jan.12888

2.

Garcia-Dia MJ DiNapoli JM Garcia-Ona L Jakubowski R O'Flaherty D . Concept analysis: resilience. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. (2013) 27:264–70. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.003

3.

Fletcher D Sarkar M . Psychological resilience: a review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. Eur Psychol. (2013) 18:12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

4.

McKinley N Karayiannis PN Convie L Clarke M Kirk SJ Campbell WJ . Resilience in medical doctors: a systematic review. Postgrad Med J. (2019) 95:140–7. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2018-136135

5.

Gao T Ding X Chai J Zhang Z Zhang H Kong Y et al . The influence of resilience on mental health: the role of general well-being. Int J Nurs Pract. (2017) 23. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12535

6.

Walpita YN Arambepola C . High resilience leads to better work performance in nurses: evidence from South Asia. J Nurs Manag. (2020) 28:342–50. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12930

7.

Maltby J Day L Hall S . Refining trait resilience: identifying engineering, ecological, and adaptive facets from extant measures of resilience. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0131826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131826

8.

Eley DS Cloninger CR Walters L Laurence C Synnott R Wilkinson D . The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: implications for enhancing well-being. PeerJ. (2013) 1:e216. doi: 10.7717/peerj.216

9.

Watson AG Saggar V MacDowell C McCoy JV . Self-reported modifying effects of resilience factors on perceptions of workload, patient outcomes, and burnout in physician-attendees of an international emergency medicine conference. Psychol Health Med. (2019) 24:1220–34. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2019.1619785

10.

Cao X Chen L . Relationships among social support, empathy, resilience and work engagement in haemodialysis nurses. Int Nurs Rev. (2019) 66:366–73. doi: 10.1111/inr.12516

11.

Ang SY Uthaman T Ayre TC Mordiffi SZ Ang E Lopez V . Association between demographics and resilience - a cross-sectional study among nurses in Singapore. Int Nurs Rev. (2018) 65:459–66. doi: 10.1111/inr.12441

12.

Lall MD Gaeta TJ Chung AS Chinai SA Garg M Husain A et al . Assessment of physician well-being, part two: beyond burnout. West J Emerg Med. (2019) 20:291–304. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.1.39666

13.

Converso D Sottimano I Guidetti G Loera B Cortini M Viotti S . Aging and work ability: the moderating role of job and personal resources. Front Psychol. (2018) 8:2262. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02262

14.

Martin AJ . Motivation and academic resilience: developing a model for student enhancement. Aust J Educ. (2002) 46:34–49. doi: 10.1177/000494410204600104

15.

Yang Y Lee P Cheng TCE . Operational improvement competence and service recovery performance: the moderating effects of role stress and job resources. Int J Prod Econ. (2015) 164:134–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2015.03.014

16.

Pattnak T Samanta SR Mohanty J . Work life balance of health Care Workers in the new Normal: a review of literature. J Med Chen Sci. (2022):42–54. doi: 10.26655/JMCHEMSCI.2022.1.6

17.

Southwick SM Sippel L Krystal J Charney D Mayes L Pietrzak R . Why are some individuals more resilient than others: the role of social support. World Psychiatry. (2016) 15:77–9. doi: 10.1002/wps.20282

18.

Iattoni M Ormazabal M Luvini G Uccella L . Effect of structured briefing prior to patient arrival on Interprofessional communication and collaboration in the trauma team. Open Access Emerg Med. (2022) 14:385–93. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S373044

19.

Winkel AF Robinson A Jones AA Squires AP . Physician resilience: a grounded theory study of obstetrics and gynaecology residents. Med Educ. (2019) 53:184–94. doi: 10.1111/medu.13737

20.

Cooper AL Brown JA Rees CS Leslie GD . Nurse resilience: a concept analysis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. (2020) 29:553–75. doi: 10.1111/inm.12721

21.

Lyng HB Macrae C Guise V Haraldseid-Driftland C Fagerdal B Schibevaag L et al . Balancing adaptation and innovation for resilience in healthcare - a metasynthesis of narratives. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:759. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06592-0

22.

Robertson HD Elliott AM Burton C Iversen L Murchie P Porteous T et al . Resilience of primary healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. (2016) 66:e423–33. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X685261

23.

Roslan NS Yusoff MSB Morgan K Ab Razak A Ahmad Shauki NI . What are the common themes of physician resilience? A Meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010469

24.

Barasa EW Cloete K Gilson L . From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan. (2017) 32:iii91–4. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx118

25.

Aiken LH Lasater KB Sloane DM Pogue CA Fitzpatrick Rosenbaum KE Muir KJ et al . Physician and nurse well-being and preferred interventions to address burnout in hospital practice: factors associated with turnover, outcomes, and patient safety. JAMA Health Forum. (2023) 4:e231809. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.1809

26.

Uccella S Mongelli F Majno-Hurst P Pavan LJ Uccella S Zoia C et al . Psychological impact of the very early beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in healthcare workers: a Bayesian study on the Italian and Swiss perspectives. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:768036. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.768036

27.

Scott BA Judge TA . Insomnia, emotions, and job satisfaction: a multilevel study. J Manag. (2006) 32:622–45. doi: 10.1177/0149206306289762

28.

Demerouti E Bakker AB Nachreiner F Schaufeli WB . The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol. (2001) 86:499–512. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

29.

Zaidi SR Sharma VK Tsai SL Flores S Lema PC Castillo J . Emergency department well-being initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic: an after-action review. AEM Educ Train. (2020) 4:411–4. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10490

30.

Mealer M Jones J Meek P . Factors affecting resilience and development of posttraumatic stress disorder in critical care nurses. Am J Crit Care. (2017) 26:184–92. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2017798

31.

Murray E Gidwani S . Posttraumatic stress disorder in emergency medicine residents: a role for moral injury?Ann Emerg Med. (2018) 72:322–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.03.040

32.

Zwack J Schweitzer J . If every fifth physician is affected by burnout, what about the other four? Resilience strategies of experienced physicians. Acad Med. (2013) 88:382–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318281696b

33.

McKinley N McCain RS Convie L Clarke M Dempster M Campbell WJ et al . 32, and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2020) 10:e031765. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031765

34.

West M Coia D . Caring for doctors, caring for patients. Gen Med Council. (2019)

35.

De Wit K Lim R . Well-being and mental health should be top priority for the emergency medicine workforce. CJEM. (2021) 23:419–20. doi: 10.1007/s43678-021-00163-2

36.

Patel VL Shidhaye R Dev P Shortliffe EH . Building resiliency in emergency room physicians: anticipating the next catastrophe. BMJ Health Care Inform. (2021) 28:e100343. doi: 10.1136/bmjhci-2021-100343

37.

West CP Dyrbye LN Sinsky C Trockel M Tutty M Nedelec L et al . Resilience and burnout among physicians and the general US working population. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e209385. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9385

38.

Vanyo L Sorge R Chen A Lakoff D . Posttraumatic stress disorder in emergency medicine residents. Ann Emerg Med. (2017) 70:898–903. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.07.010

39.

Shanafelt TD Boone S Tan L Dyrbye LN Sotile W Satele D et al . Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. (2012) 172:1377–85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

40.

Lu DW Dresden S McCloskey C Branzetti J Gisondi MA . Impact of burnout on self-reported patient care among emergency physicians. West J Emerg Med. (2015) 16:996–1001. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.9.27945

41.

Cai W Lian B Song X Hou T Deng G Li H . A cross-sectional study on mental health among health care workers during the outbreak of Corona virus disease 2019. Asian J Psychiatr. (2020) 51:102111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102111

42.

Connor KM Davidson JR . Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. (2003) 18:76–82. doi: 10.1002/da.10113

43.

Rammstedt B John OP . Measuring personality in one minute or less: a 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. J Res Pers. (2007) 41:203–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

44.

Campbell-Sills L Stein MB . Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. (2007) 20:1019–28. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271

45.

Di Fabio A Palazzeschi L . Connor-Davidson resilience scale: psychometric properties of the Italian version. Counseling Giornale Italiano di Ricerca e Applicazioni. (2012) 5:101–10.

46.

Arias González VB Crespo Sierra MT Arias Martínez B Martínez-Molina A Ponce FP . An in-depth psychometric analysis of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale: calibration with Rasch-Andrich model. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2015) 13:154. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0345-y

47.

Oshio A Taku K Tirano M Saeed G . Resilience and big five personality traits: a meta-analysis. Personal Individ Differ. (2018) 127:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048

48.

Kruschke JK . Bayesian estimation supersedes the t test. J Exp Psychol Gen. (2013) 142:573–603. doi: 10.1037/a0029146

49.

Reed DE Reedman AE . Reactivity and adaptability: applying gender and age assessment to the leader resilience profile. Front Educ. (2020) 5:art 574079. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.574079

50.

Erdogan E Ozdogan O Erdogan M . University students’ resilience level: the effect of gender and faculty. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. (2015) 186:1262–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.047

51.

Hodes GE Epperson CN . Sex differences in vulnerability and resilience to stress across the life span. Biol Psychiatry. (2019) 86:421–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.04.028

52.

Rivera M Shapoval V Medeiros M . The relationship between career adaptability, hope, resilience, and life satisfaction for hospitality students in times of Covid-19. J Hosp Leis Sport Tour Educ. (2021) 29:100344. doi: 10.1016/j.jhlste.2021.100344

53.

Abdolrezapour P Jahanbakhsh Ganjeh S Ghanbari N . Self-efficacy and resilience as predictors of students' academic motivation in online education. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0285984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0285984

54.

van Agteren J Iasiello M Lo L . Improving the wellbeing and resilience of health services staff via psychological skills training. BMC Res Notes. (2018) 11:924. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-4034-x

55.

Jiménez-Rodríguez D Molero Jurado MDM Pérez-Fuentes MDC Arrogante O Oropesa-Ruiz NF Gázquez-Linares JJ . The effects of a non-technical skills training program on emotional intelligence and resilience in undergraduate nursing students. Healthcare. (2022) 10:866. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10050866

Summary

Keywords

resilience, healthcare professionals, healthcare providers, personality traits, hospital, physicians, nurses

Citation

Uccella L, Mascherona I, Semini S and Uccella S (2024) Exploring resilience among hospital workers: a Bayesian approach. Front. Public Health 12:1403721. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1403721

Received

19 March 2024

Accepted

15 August 2024

Published

29 August 2024

Volume

12 - 2024

Edited by

Biagio Solarino, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Italy

Reviewed by

Sagrario Gomez-Cantarino, University of Castilla La Mancha, Spain

Iwona Bodys-Cupak, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Poland

Updates

Copyright

© 2024 Uccella, Mascherona, Semini and Uccella.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Laura Uccella, laura.uccella@eoc.ch

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.