- 1College of Nursing, Rush University, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2College of Nursing, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States

- 4College of Science and Health, DePaul University, Chicago, IL, United States

Introduction: Black Girls Move is a 12-week, race-conscious, multicomponent, mHealth obesity prevention intervention for Black 7th–10th grade daughters and their mothers. The complex experiences of Black female adolescents and adults necessitate tailored recruitment and retention strategies to address structural, programmatic, and interpersonal barriers to participation. We outline culturally responsive recruitment and retention strategies, lessons learned, and their implications.

Methods: A review of recruitment literature highlighted trust-building as essential. We utilized guidelines for evaluating recruitment feasibility in pilot studies and the Community-Informed Recruitment Plan template of diverse populations as frameworks to assess and refine our recruitment and retention approach.

Results: Key findings included: (1) trust was critical for sustaining participant relationships from screening to baseline, (2) weight eligibility criteria were overly restrictive, (3) recruitment targets needed adjustment to prevent school loss, and (4) competing demands impacted engagement. Refinements involved consulting community leaders and an expert community research consultant, leading to (1) broadening eligibility criteria to include daughters of all weight statuses and 7th–8th graders; (2) increasing incentives to align compensation with time commitments for surveys; and (3) hiring a community health worker to address communication and scheduling issues while fostering trust.

Discussion: Strengthening trust, expanding eligibility, and improving incentives enhanced recruitment and participant engagement. We found this culturally tailored, race-conscious approach was valuable in refining recruitment strategies. Future studies should test the guidelines for evaluating the feasibility of recruitment and the Community-Informed Recruitment Plan template of diverse populations in a large-scale randomized control trial.

Introduction

Racism is a system that organizes access to opportunities and assigns worth to individuals based on socially constructed perceptions of physical appearance—commonly referred to as race (1). Race is a social categorization rooted in shared physical traits (e.g., White, Black non-Hispanic, Asian, Native American), while ethnicity refers to common cultural or ancestral backgrounds, (e.g., Hispanic/Latino or other ethnicities) (2, 3). Studies have consistently shown that racial and ethnic discrimination contributes to poorer health outcomes (4). For example, Black adolescent females have the highest rates of obesity when compared to their non-Hispanic White counterparts while Hispanic/Latino adolescent females have the second highest rates (5, 6). Obesity in adolescence is identified as >95th percentile of body mass index (BMI) for sex and age (5). While both Black and Hispanic adolescent females experience disproportionate rates of obesity, the contributing factors that influence lifestyle change may differ for these distinct populations. However, there have been few studies of Black adolescent females, limiting the development of culturally appropriate obesity-prevention interventions.

A systematic review of 74 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) focused on obesity prevention among adolescents aged 12 to 18, revealed that of the 31 studies conducted in the United States, Black adolescent females comprised >10% of the participants in only 12 studies (7). These findings underscore the absence of interventions that prioritize the lived experiences of Black adolescent females which is troubling because they have increased risks for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, elevated body dissatisfaction, lower self-esteem, ADHD, and depressive symptoms as compared to their racial/ethnic counterparts (8).

Lifestyle modification is a critical component of obesity prevention interventions that target Black adolescent females. In this population, obesity is associated with poor dietary practices and limited physical activity (PA), and complicated by socioeconomic status (6). For example, Black females consume more calories from sugar-sweetened beverages than Black males (9), eat fewer vegetables, and have breakfast less often than recommended compared to other racial/ethnic groups (10). Simultaneously, as they pursue independence and individuality, adolescents choose more sedentary behaviors and become less physically active (11–15). National survey data of adolescents aged 12–15 and 16–19 years old indicate that they do not meet national guidelines for moderate to vigorous PA (16). Alarmingly, Black adolescent females had the lowest step counts and highest rates of sedentary behavior when compared to their peers by gender, race, and age (16). One strategy for promoting a healthy lifestyle in Black adolescent females is to actively involve their mothers in supporting behavior change.

Numerous studies have investigated the role of mothers in shaping their daughters’ health behaviors (17–19). In many Black families, mothers are key contributors to children’s health and social development, often taking the lead in nutrition and caregiving responsibilities (20, 21). Yet despite the potential for mothers to support healthy behaviors of their adolescent daughters, there is a lack of obesity prevention research that includes Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads. To address this gap, our team developed the Black Girls Move (BGM) obesity prevention intervention and is currently conducting a Phase I trial to test its feasibility and preliminary change in primary outcomes. Obesity prevention programs for Black adolescent females must consider that as girls transition into adolescence, they are increasingly influenced by the environmental and developmental factors that affect dietary and PA behaviors which place them at high risk for obesity (6).

Environmental factors

Some argue health disparities are merely a function of differences in socioeconomic status; however, there is growing evidence that structural racism contributes to racial health disparities (22). Structural racism includes policies and laws which provide advantages to groups based on race while oppressing another race (23, 24). Black adolescent females living in low-income communities are at particular risk for obesity due to racial residential segregation and its role in creating obesogenic environments characterized by reduced access to healthy foods, heavy marketing of unhealthy food (25, 26), few safe, walkable streets, park areas, and exercise facilities (13, 27–30). To prevent obesity and the associated co-morbidities in this at-risk population, programs must acknowledge the impact of racism on dietary and PA behaviors, rather than simply prescribing interventions that do not consider their lived racialized context.

Developmental factors

Adolescent daughters often rely on their mothers for information, guidance, and support as they work to adopt or maintain healthy behaviors (31). Our cross-sectional, descriptive study to assess the eating behaviors of 10- to 12-year-old Black daughters and their mothers (N = 43) showed strong concordance between daughters’ and mothers’ consumption of discretionary calories, such as sugar sweetened beverages (32). Similarly, the influence of mothers in shaping their daughters’ dietary and PA behaviors has been demonstrated repeatedly in cross-sectional studies (6, 25, 33). We developed BGM by acknowledging the environmental and developmental factors that affect Black adolescent females and their mothers. The complex intersection of environmental and developmental factors has exacerbated barriers to the recruitment of Black adolescents into research studies. These recruitment barriers can be structural (transportation, inconvenience) or cultural (lack of cultural concordance of mistrust) and require innovative and tailored recruitment strategies (34). Similarly, Black women face recruitment barriers, such as inability to miss work or lack of trust in researchers (35).

The need for obesity prevention interventions

A review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of culturally tailored obesity treatment interventions (N = 44 RCTs) for adolescents aged 12–17 years, found low quality evidence for reducing BMI, inconsistent evidence for improving dietary behaviors, and no evidence for improvements in objective or self-report measures of PA (36). Similar findings were reported in two relevant obesity treatment RCTs Go Girls (37) and the Health Improvement Program (HIP) for teens (38), that tested culturally tailored, family-focused interventions (primarily involving mothers) in overweight and obese Black adolescent females in the US. Go Girls (37) was not effective for reducing adiposity, while the HIP for Teens showed an initial reduction that was not maintained. Several factors may account for the limited effects of these two treatment interventions: (1) once obesity is established in childhood it is hard to reverse (39), which supports our intervention to prevent obesity in Black adolescent females; (2) because Black adolescent females may show greater acceptance of heavier bodies (40, 41), weight maintenance may be a more acceptable goal than weight loss; and (3) parents participated in both interventions, but there was no focus on modifying daughter-mother communication, problem solving, role assignment, or relationship quality.

Adolescence is a critical transitional period marked by growing autonomy, yet it remains a time when parental influence is still essential. It is important to establish relevant recruitment and retention plans for obesity prevention interventions with Black adolescent females. There are known barriers to recruitment of Black adolescents (42), Black mothers, and even Black youth/parent dyads (43). However, less is known about specific barriers to recruitment of Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads. Further, obesity prevention studies with Black daughter/mother dyads to date have not focused on the pivotal developmental period of adolescence. Given the lack of obesity prevention research with Black adolescent daughter and mother dyads, the purpose of this paper is to describe the lessons learned from recruiting participants into the first 2 years of Black Girls Move (BGM), an obesity prevention/weight maintenance intervention.

Black Girls Move: an obesity prevention/weight maintenance intervention

We designed Black Girls Move (BGM) loosely from the Diabetes Prevention Program, using community engaged research principles of working with communities of interest. We first used interviews and focus groups to draft and refine BGM with Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads and clinical experts (44). We then pilot tested BGM with Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads and incorporated their feedback into its refinement. This iterative process to intervention development produced a culturally tailored and informed intervention (45). Participants provided feedback on placement of content, delivery format, and appropriateness of materials (44). In addition, a culturally acceptable approach in BGM was the concept of weight maintenance, which has shown promise as an effective and culturally relevant strategy to address risk for obesity-related diseases in Black females (46). Based on participant feedback, we defined obesity prevention as encompassing both weight loss and weight maintenance.

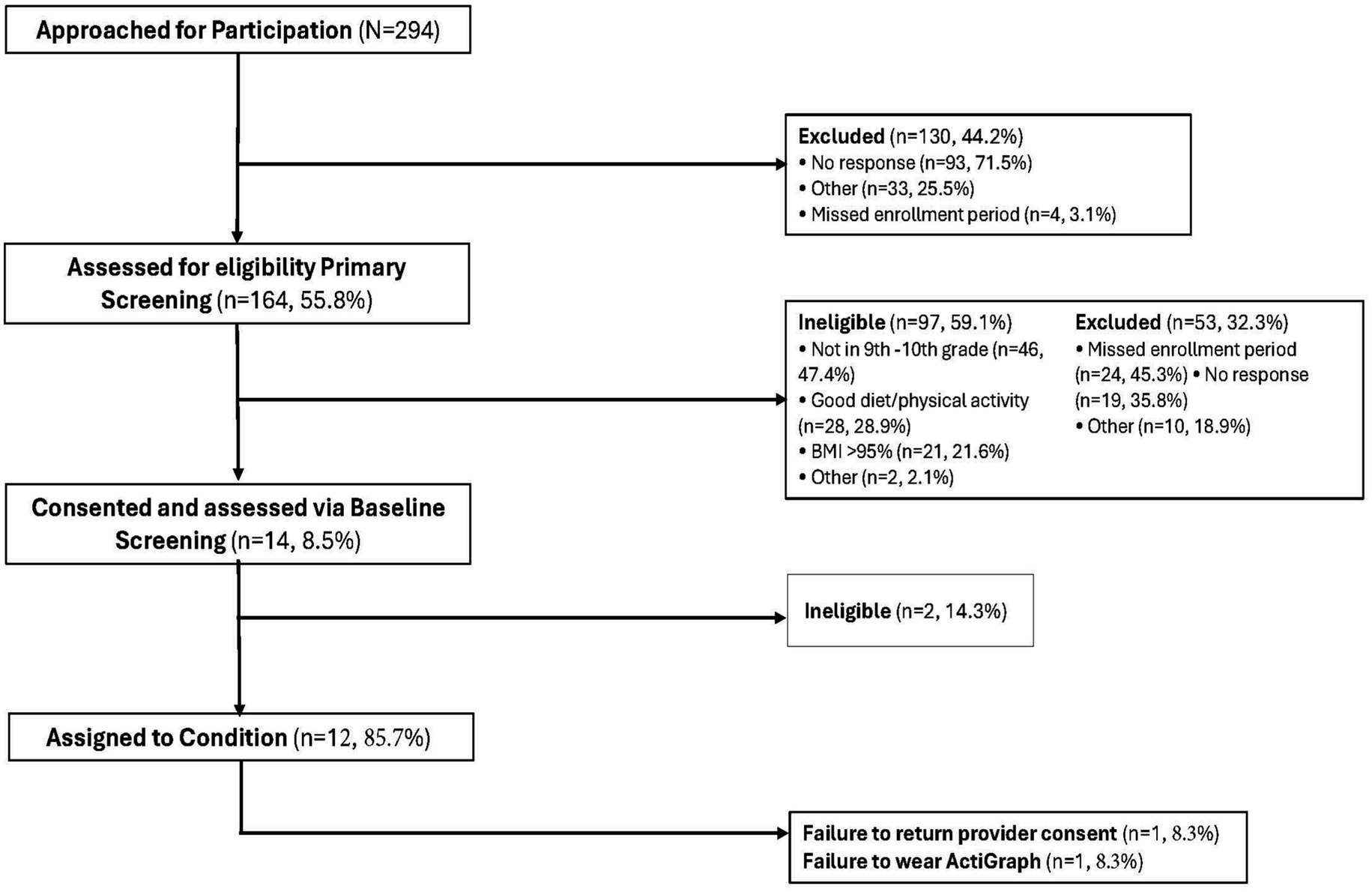

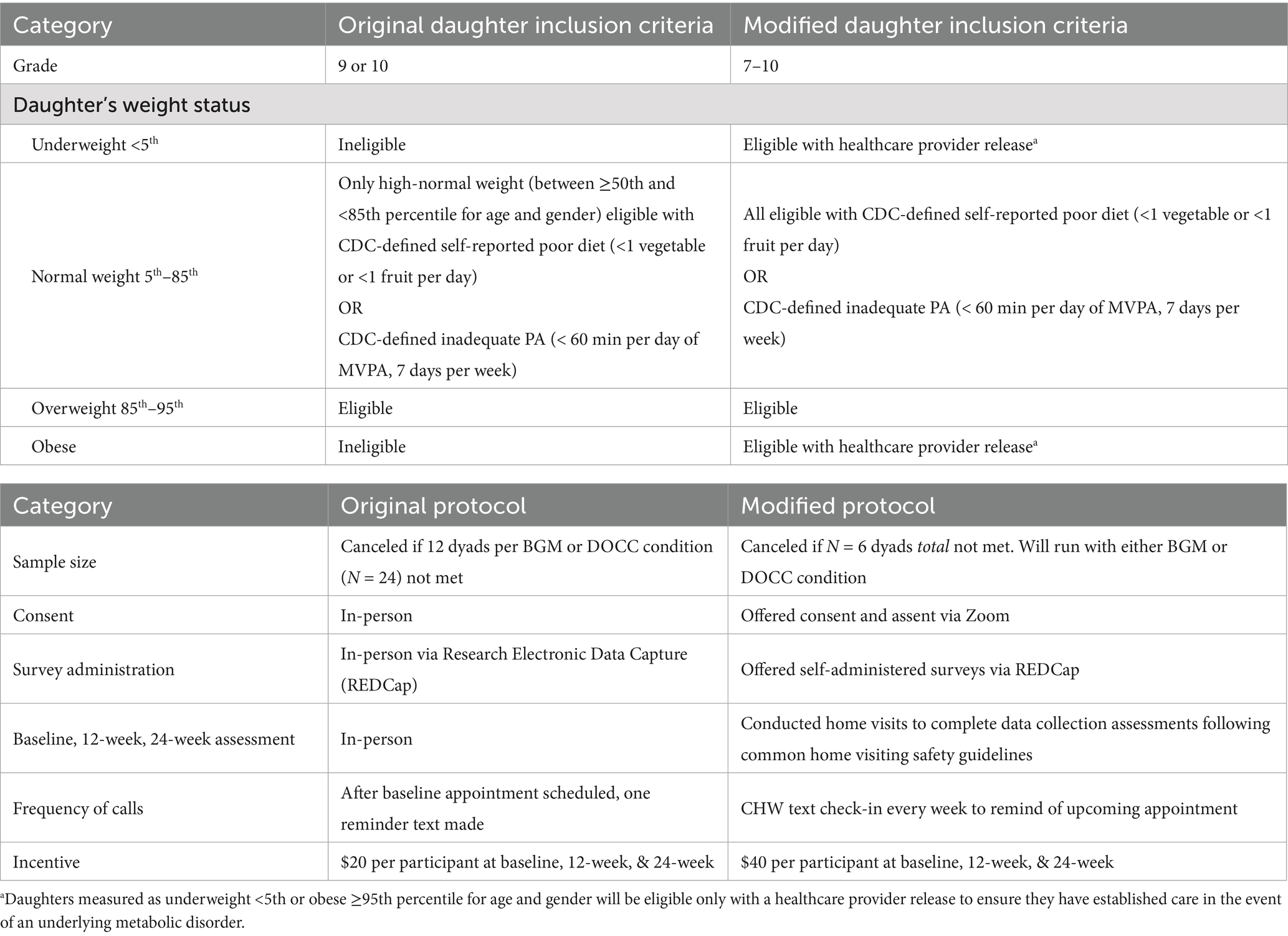

BGM is a 12-week race-conscious, multicomponent, mobile health (mHealth) obesity prevention intervention designed for 7th–10th grade Black adolescent females and their mothers. Inclusion criteria for daughters were (a) English-speaking; (b) Black; and (c) daily access to the internet outside of school and/or work through an iOS or android smartphone, tablet, or personal computer. Inclusion criteria for mothers were (a) English-speaking; (b) Black; (c) co-residing biological mother or mother-figure and legal guardian of the participating daughter; (d) the person primarily responsible for meals in the household; and (e) access to the internet through an iOS or android smartphone, tablet or personal computer. Originally, we only included daughters that measured as overweight to focus on obesity prevention. However, this criterion excluded 21.6% of daughters (Figure 1). Therefore, we modified our study protocol to include all weight categories with medical release. In addition, the original protocol excluded 7th and 8th graders, which resulted in 47.4% of daughters being ineligible for the study. After speaking with key personnel in schools that served 7th–12th grades, we recognized the importance of establishing healthy behaviors in 7th and 8th graders and modified our study protocol to include 7th–10th graders. The initial recruitment results enabled us to refine inclusion and exclusion criteria to optimize participant safety, recruit sufficient numbers of participants, and promote generalizability of findings (47). In a future study we plan to include a longer follow-up period of 11th and 12th graders to assess maintenance of behaviors as adolescents transition to post-secondary activities. The original and modified inclusion criteria are further described in Table 1.

In addition to using mHealth technology, BGM actively engages Black adolescent daughters and their mothers through structured group sessions. The feasibility, preliminary change in outcomes, and impact of BGM will be evaluated against a daughter-only comparison condition (DOCC), which delivers identical content as BGM but excludes maternal participation. In the protocol, eligible participants are randomly assigned 1:1 to either the BGM active treatment or DOCC. BGM is informed by race-conscious, Public Health Critical Race Praxis (PHCRP), Family Systems, and Social Cognitive theories. The intervention development, description of each theoretical component, and outcomes of BGM are described in the BGM protocol (45). The specific aims are to determine in Black adolescent females:

(1) The feasibility (recruitment, retention, and acceptance) of BGM compared to DOCC.; (2) The preliminary change in primary outcomes, including: (a) number of steps per day, and (b) diet quality, measured by the self-reported intake of five components of the Healthy Eating Index-2010 (vegetables, fruit, whole grains, dairy, and protein), as well as secondary outcomes such as: (c) minutes of moderate/vigorous physical activity per week, (d) self-report physical activity, and (e) consumption of sugar sweetened beverages; and (3) The impact of BGM compared to DOCC on differences in theoretical mechanisms of change, including (racial identity, daughter/mother relationship, social cognitions) assessed by self-report measure.

Materials and methods

To monitor recruitment, we followed the eight-step guidelines for evaluating feasibility of recruitment in pilot studies of diverse populations (48).

Step 1: describe recruitment goals

As a feasibility study, we did not perform a formal power analysis to determine sample size. Instead, sample size estimates from the Diabetes Prevention Program were used, which suggested at least 5 participants per group to promote peer support, interaction, and group cohesion (49, 50). The group format with dyads provided a mechanism for mothers to share successes and adaptive response strategies with their daughters. Originally, if a minimum of N = 12 dyads per school/per condition was not met, the school was canceled but based on the challenges of meeting a total of 24 dyads per school we reduced the cancelation criterion to <N = 6 dyads. Six dyads were selected as a minimum recruitment target to account for absences, yet small enough to allow participants time to discuss new foods, ways of preparing foods, or new PA strategies with other dyads.

Step 2: describe recruitment process

Prior to starting recruitment, we reviewed relevant literature to identify successful culturally tailored recruitment strategies with Black adolescents and determined that building trust, combined with active and passive recruitment strategies, was essential (51–53). Culturally tailored strategies to build trust include community engagement and partnerships, effective communication, culturally competent recruitment materials, involvement of role models, accessibility and convenience, ongoing support, and feedback and adaption (34, 54–56).

Building trust requires a thoughtful and respectful approach that integrates clear communication, cultural sensitivity, and meaningful community engagement. Toward that end, we were intentionally mindful of language nuances that could be ambiguous and lead to unintended connotations. We also cultivated trust by becoming familiar with the community—being present in local spaces, such as connecting with schools and consulting community leaders. We employed team members who shared cultural similarities with participants, and we trained them to interact respectfully with families and school personnel to forge and sustain positive relationships. We conducted in-person enrollment and approached informed consent with care and respect (34, 54–56). Finally, we held in-person meetings with key school leaders to assess the communication and language preferences and norms of students, teachers, and staff.

Active recruitment refers to direct interaction with the target population to increase awareness about the study and provide prospective participants the opportunity to approach the researcher(s) (53, 57, 58). Our active recruitment plan consisted of multiple components. First, we obtained endorsements from the school principals. Second, we built relationships through separate recruitment activities for daughters and mothers. Recruitment activities with daughters occurred during lunchroom or after school activities, while activities with mothers occurred during parent report card pick up. Third, we encouraged daughters to fill out a sheet that collected personal information of daughter (first and last name, grade, and phone number) and mother (first and last name, email, phone number, and preferred time of contact). This information was used to contact mothers to begin the screening process for eligibility. During encounters with both daughters and mothers, a research team member screened for eligibility, explained the study, and scheduled a baseline assessment if time permitted. Otherwise, screening and study explanation were completed on a subsequent telephone call. Lastly, in-person presentations were given to mothers at parent advisory board meetings and to daughters and mothers at a college interest fair. The active recruitment strategies allowed us to obtain contact information for subsequent telephone calls to screen for eligibility. In addition to these strategies, we were responsive to school-specific requests related to relationship building. For example, at two of the high schools, the research team held a health careers seminar during the “flexible period.” At another school, health careers information (59) was presented during the school’s parent night.

Passive recruitment refers to increasing awareness about the study without direct contact (53). Our passive recruitment techniques included distributing flyers through e-mail and posting them in the administrative office, library, and gymnasium of 4 high schools (grades 9–12) and one middle-high school (grades 7–12). The flyer included the Black Girls Move logo, Quick Response (QR) code, information about the study, eligibility criteria, amount of participant gift card compensation for their time, and the principal investigator’s contact information. In addition to trust building, active, and passive recruitment (57, 58) study staff completed training specific to recruitment and retention strategies for minoritized populations. These strategies included training on historical fears of participating in research, partnering with community organizations, and tailoring recruitment materials (60).

Steps 3 & 4: establish a tracking system and tracking database

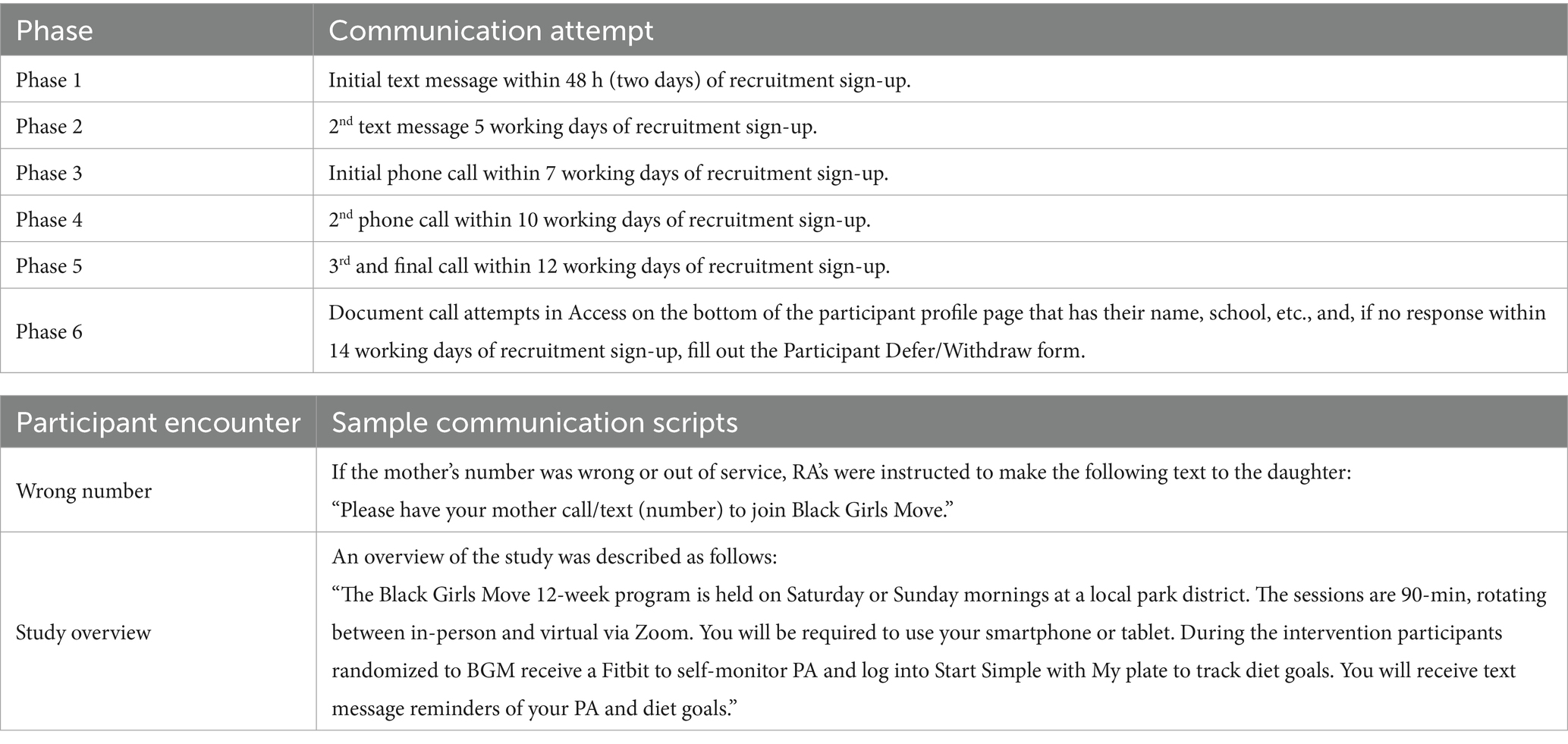

Daughter/mother dyads were recruited from five Chicago Public High Schools (one of the five included a middle school). Each high school had a student body of greater than 80% of Black students, poverty rates above 80%, and was not on academic probation. While these criteria limited the number of schools that were eligible to participate in the study, they assured that we recruited from the targeted population. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) (61), was used to document the flow of participants through the recruitment process. Recruitment data were maintained in a secure Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)-compliant database, created in Access for Microsoft 365. The database contained participants’ names, phone numbers, dates of birth, and daughters’ grades and schools. The data manager trained research assistants (RAs) to input data into the Access database using the RA training manual developed by the principal investigator. RAs used the Access database to document the outcome of calls, the number of call attempts, and enter eligibility criteria. RAs followed a documentation protocol for each recruitment activity. For example, lunchroom recruitment protocol included guidelines for RAs to enter participant data into the Access database within 48 h after lunchroom recruitment and to send text messages to all mothers according to the communication protocol. Once contact was made, RAs would describe the study, answer questions, and screen those interested according to the six phases of the communication protocol (Table 2).

Step 5: tracking individual progress

The principal investigator reviewed the CONSORT diagram weekly. Results were shared with co-investigators in weekly meetings to monitor accrual against targets. Enrollment rates were calculated and reported to the funding agency annually. Assessment periods for each school lasted for 8 weeks. The first 4 weeks included lunchroom and after-school recruitment, followed by 4 weeks of baseline screening. Recruitment and enrollment rates for each school were evaluated at the end of each assessment period. Results of recruitment and enrollment were used to plan potential modifications to recruitment methods.

Steps 6 through 8: summarize recruitment results; summarize feasibility results; utilize tracking data to inform modifications

Two hundred and ninety-four daughters expressed interest and received telephone screening call attempts (Figure 1). Of the 294 dyads, 44.2% (n = 130) could not be reached for telephone screening. Of the 164 mothers screened, 59.1% (n = 97) were ineligible (i.e., not in 9th or 10th grade, or BMI > 95%) and 32.3% (n = 53) were excluded (i.e., missed assessment/enrollment period or no response). Fourteen dyads were consented and assessed for eligibility at baseline screening. Of the 14 dyads that were screened at the in-person baseline screening, 14.3% (n = 2) were ineligible for reasons that were not documented and the remaining 12 dyads were assigned to a condition. Of the 12 dyads, one failed to return provider consent and one failed to wear the initial actigraph. Our feasibility data showed that the recruitment goal of 24 dyads per school (12 dyads per condition) was not met, therefore we canceled the intervention at four schools. The last step of the guidelines for evaluating feasibility of recruitment involves modifying recruitment methods based on the tracking data. Our modifications are described below.

Recruitment and study modifications

Recruitment modifications

Cunningham-Erves et al. (60), applied a community engaged approach to develop the Community-Informed Recruitment Plan Template, hereafter referred to as, the template. The template serves to help increase recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minority groups by engaging community members in targeted discussions. The template includes: (1) Recruitment Strategy; (2) A Stakeholder Communication Plan; (3) Evidence of Recruitment Feasibility; (4) Recruitment and Retention Team; (5) Recruitment and Retention Methods; (6) Recruitment and Retention Timeline; (7) Evaluation; and (8) Budget. We applied the template to develop a plan for study modifications.

Study modifications

Despite our recruitment efforts, we did not meet recruitment targets in Year 1. Hence, we analyzed tracking data, met with community leaders, and engaged an expert community research consultant to modify our recruitment methods. The consultation yielded four lessons that influenced recruitment changes: (1) the importance of maintaining relationships over time to sustain trusting relationships, (2) prior weight eligibility criteria were too prescriptive, (3) the investigators need to change recruitment targets to minimize school loss, and (4) competing demands influenced engagement. Consequently, we (1) hired a community health worker (CHW) to address communication and scheduling concerns and to maintain trusting relationships with eligible participants until the intervention started; (2) amended eligibility criteria to include daughters of all weight status and 7th & 8th graders; and (3) increased incentives to $40 per participant at each data collection point, from $20 per participant to align compensation with the time requested to engage in the baseline assessment process.

Maintaining relationships over time to sustain trusting relationships

One lesson learned from Year 1 was the importance of maintaining relationships with participants and school partners to sustain trust in all research phases. Partnerships within the targeted school communities were initially established prior to receiving study funding and included the schools’ principals, teachers, and nurses. To facilitate a community engaged approach, the principal investigator and project director met with the designated school leaders to explore modifications to our recruitment strategies. These recruitment-focused conversations reinvigorated the initial partnership, leading to robust recommendations that were incorporated into a new recruitment plan tailored for that school. The plan incorporated recommendations on the optimal timing and locations for recruitment and intervention activities. For example, partners from one school recommended the research team connect with the Parent University Program, a monthly meeting for parents and school faculty to discuss students’ career aspirations and extracurricular activities.

In two schools there was an unanticipated three-month gap between the end of study recruitment and the intervention start, resulting in a start date that coincided with the beginning of summer break. School partners advised that participants would have difficulty engaging in the intervention due to changes in their summer school/work schedules, travel, and other summer-related plans. Therefore, the intervention start date was delayed, resulting in some participants losing interest, being unreachable by phone, or aging out of eligibility. After reflection, we identified opportunities to improve subsequent rounds of BGM recruitment and engagement to sustain trust once established. First, we scheduled recruitment periods to avoid starting the intervention during summer break. Second, to sustain trust, we hired a CHW to address communication and scheduling concerns and maintain close contact with eligible participants. CHWs serve on the front lines of public health and are either deeply trusted by the communities they support or possess an intimate understanding of their needs and experiences (62). In BGM we incorporated the role of the CHW to enhance communication and provide social support from recruitment through start of intervention (63, 64). Examples of enhanced communication strategies included text message check-ins and referring participants to a BGM website with health information.

Changes in eligibility criteria and recruitment sites

Twenty one percent (n = 21) of the adolescent participants and their mothers attended baseline assessments and were found to be outside the initial study weight criteria, i.e., high-normal weight (between ≥50th and <85th percentile for age and gender) or overweight (between ≥85th and <95th percentile for age and gender). These adolescent participants were excluded from the study. In response, we requested and received IRB approval to amend the study protocol to also include daughters with underweight (<5th percentile) or obesity (≥95th percentile) based on BMI for age and gender. The daughters with underweight or obesity were required to provide a healthcare provider release to ensure connection to established care in case of an underlying metabolic disorder. Our modified weight criterion opened eligibility to adolescents with normal weight (≥5th and <85th percentile for age and gender) (65), if they reported either a poor diet (consuming <1 vegetable or <1 fruit per day) (66) or inadequate PA (completing <60 min per day of MVPA, 7 days per week).

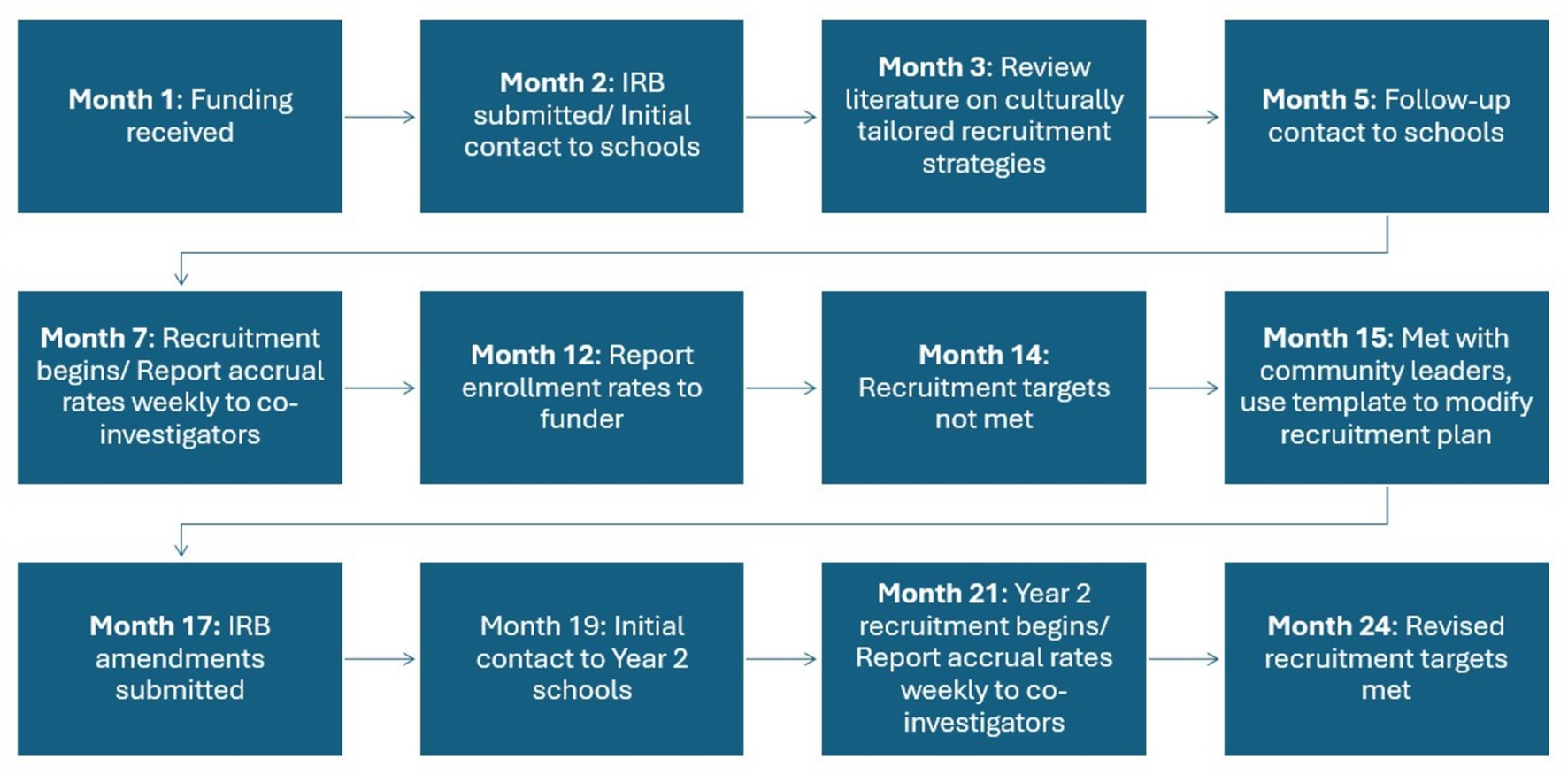

Due to the small number of daughters who initially met the inclusion criteria to participate in the study, it was determined that a wider pool of eligible daughters was needed to meet the study aims. Accordingly, we: (1) received IRB approval to amend the protocol to include 7th–8th graders at least 13-years-old and (2) reduced the recruitment target for dyads from 24 dyads (12 dyads per school/per condition) to 6 dyads per school/per condition. If the total number of recruited dyads was less than 12 we would not cancel the school, but instead proceed with either an intervention or control group to assess feasibility. To ensure opportunity to evaluate the feasibility of the BGM intervention, schools with less than 12 recruited dyads were assigned to BGM until two cohorts received BGM. After that, schools will be assigned to DOCC until one cohort receives DOCC. Additional cohorts will be randomly assigned to BGM or DOCC. A timeline of recruitment events from study start to revision of recruitment targets is depicted in Figure 2. In Year 2, with the revised criteria, the BGM study successfully recruited and ran intervention groups with 10 daughter and mother dyads at one school and 7 dyads at another.

Competing demands influenced engagement

Competing demands resulted in last minute cancelations or no shows (67) negatively impacting accrual of Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads. Competing demands refer to other priorities that may compete with research participation, such as school, work, family commitments, and social activities (54). Needing to work, being a primary caretaker of children and/or relatives, being the single head of household, and time off work or travel costs related to participation presented conflicts to engaging in research activities (35, 68). To surmount multiple competing demands the following strategies were employed: (1) increased remuneration for time by increasing gift card incentives from $20 to $40 per participant for each data collection period, (2) hosted sessions and appointments at a convenient location in the community on weekends, (3) provided onsite childcare, (4) offered consent and assent via Zoom, (5) offered self-administered surveys via Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), and (6) conducted home visits to complete data collection assessments following common home visiting safety guidelines (69).

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to describe the lessons learned from 2 years of recruiting participants for BGM, an obesity prevention/weight maintenance intervention targeted and tailored for Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads. For recruitment, we learned that: (1) prior weight eligibility criteria were too prescriptive and (2) we needed to change recruitment targets to minimize school loss. For retention we learned that: (1) maintaining relationships with participants from screening to baseline and fostering consistent interactions throughout the study were essential and (2) competing demands influenced engagement.

BGM was designed to focus on obesity prevention/weight maintenance as opposed to weight loss or obesity treatment. Therefore, the original weight criteria excluded adolescent females with obesity to target individuals with high-normal weight or overweight. We revised our sampling criteria to include daughters with underweight (<5th percentile) or obesity (≥95th percentile) based on BMI for age and gender. For these individuals, it is important to frame strategies around weight maintenance rather than loss, as studies suggest lost weight is likely to be regained within 1–5 years (70, 71). Our revised sampling criteria were informed by Health at Every Size (HAES), a weight neutral approach that emphasizes health promoting behaviors rather than size or weight (72). The core principles are weight inclusivity, health enhancement, eating for wellbeing, life enhancing movement, and respectful care. A focus group of 41 Black women aged 18–24 assessed their perceptions of HAES and provided their insights in three themes: health is multidimensional, good health means “taking care of yourself,” and systemic and environmental disparities impact Black women’s health (72). While these perceptions of HAES principles among the young adults in the focus groups align with the BGM strategies of weight maintenance, the perceptions of HAES principles among Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads require investigation.

Although we incorporated strategies to establish trusting relationships for recruitment, we needed additional strategies to maintain trusting relationships for retention. Winter et al. (35), suggest minimizing duration of study components, such as assessment periods, as much as possible to enhance participant retention. Long gaps in engagement may increase dropout rates due to loss of participant interest and trust, or change in availability (35).

The CHW’s previous training gave her a comprehensive understanding of evidence-based health promotion strategies for Black adolescent and adult female populations. Based on her prior experience, the CHW suggested engaging participants through regular check-ins via text messaging and communicating relevant information via easily accessible and sustainable platforms such as the study website. Emerging data suggest that text messaging is associated with increased motivation, knowledge, and comfort in Black mothers participating in behavioral change clinical trials (73, 74). Additionally, using a website with study updates and health information are acceptable strategies to improve retention (60). We recommend that future studies systematically investigate these strategies to determine their efficacy.

Conclusion and limitations of the study

Our experience delivering a race conscious, obesity prevention intervention for Black adolescent females and their mothers resulted in the identification of several recruitment challenges. Leveraging our already established partnerships with key leaders in the study schools, we collaboratively addressed recruitment challenges by implementing community informed strategies. The guidelines for evaluating the feasibility of recruitment in pilot studies of diverse populations and the Community-Informed Recruitment Plan template (i.e., template) both offered a framework for systematically evaluating and measuring recruitment and retention feasibility.

A limitation of this study is that we did not systematically incorporate the template into the initial development of the recruitment plan. Future studies should test the guidelines for evaluating the feasibility of recruitment and the template to increase recruitment and retention in a large-scale randomized control trial. We found that this culturally tailored, race-conscious approach was valuable in enhancing recruitment strategies. However, since we included several strategies, we did not have the capability of evaluating individual strategies to assess which of the changes was most effective. Finally, given the small sample size of this study, the findings cannot be generalized.

Justice in nursing ethics implores nurses to provide equitable treatment to all they serve. In the current research climate there are funding limitations, academic pressures, policy shifts, and possibly institutional barriers to implementing community engaged interventions. Despite these challenges, it is imperative to address health disparities while centering the experiences of marginalized populations. Now, more than ever, justice is needed in the conceptualization, design, implementation, and evaluation of health disparities interventions to achieve equitable health outcomes such as obesity prevention/weight maintenance projects for Black adolescent daughter/mother dyads.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Rush University Medical Center IRB. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

TB: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WJ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SH: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing. BS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KW-R: Investigation, Writing – original draft. KW: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. CY: Investigation, Writing – original draft. MR: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was conducted with the support of R01DK132698 NIH/NIDDK.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Braveman, PA, Arkin, E, Proctor, D, Kauh, T, and Holm, N. Systemic and structural racism: definitions, examples, health damages, and approaches to dismantling. Health Aff. (2022) 41:171–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01394,

2. American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Race and ethnicity. Available online at: https://www.apa.org/topics/race-ethnicity/index (Accessed October 12, 2025).

3. Roberts, D. (2018). Fatal invention: how science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century. New Press/ORIM. Available online at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Fatal%20invention%3A%20How%20science%2C%20politics%2C%20and%20big%20business%20re-create%20race%20in%20the%20twenty-first%20century&author=D.%20Roberts&publication_year=2011 (Accessed October 12, 2025).

4. Forde, A, Crookes, D, Suglia, S, and Demmer, R. The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. (2019) 33:1–18.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.02.011,

5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health. (2025). Obesity and Black/African Americans. Available online at: https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/obesity-and-blackafrican-americans (Accessed October 12, 2025).

6. Winkler, MR, Bennett, GG, and Brandon, DH. Factors related to obesity and overweight among black adolescent girls in the United States. Women Health. (2017) 57:208–48. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2016.1159267,

7. Spiga, F, Tomlinson, E, Davies, AL, Moore, THM, Dawson, S, Breheny, K, et al. Interventions to prevent obesity in children aged 12 to 18 years old. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2024) 5:CD015330. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD015330.pub2

8. Sutherland, ME. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among African American children and adolescents: risk factors, health outcomes, and prevention/intervention strategies. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2021) 8:1281–92. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00890-9,

9. Rosinger, A, Herrick, K, Gahche, J, and Park, S. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among U.S. youth, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. (2017) 271:1–8. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db271.htm (Accessed April 25, 2025).

10. Kann, L, McManus, T, Harris, WA, Shanklin, SL, Flint, KH, Queen, B, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. (2018) 67:1–114. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1,

11. Alberga, AS, Sigal, RJ, Goldfield, G, Prud'homme, D, and Kenny, GP. Overweight and obese teenagers: why is adolescence a critical period? Pediatr Obes. (2012) 7:261–73. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2011.00046.x,

12. Kimm, SYS, Glynn, NW, Kriska, AM, Barton, BA, Kronsberg, SS, Daniels, SR, et al. Decline in physical activity in black girls and White girls during adolescence. N Engl J Med. (2002) 347:709–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003277,

13. Todd, AS, Street, SJ, Ziviani, J, Byrne, NM, and Hills, AP. Overweight and obese adolescent girls: the importance of promoting sensible eating and activity behaviors from the start of the adolescent period. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2015) 12:2306–29. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120202306,

14. Tomiyama, AJ, Puterman, E, Epel, ES, Rehkopf, DH, and Laraia, BA. Chronic psychological stress and racial disparities in body mass index change between black and White girls aged 10–19. Ann Behav Med. (2013) 45:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9398-x,

15. van Sluijs, EMF, Ekelund, U, Crochemore-Silva, I, Guthold, R, Ha, A, Lubans, D, et al. Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet. (2021) 398:429–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01259-9,

16. Belcher, BR, Berrigan, D, Dodd, KW, Emken, BA, Chou, C, and Spruijt-Metz, D. Physical activity in U.S. youth: effect of race/ethnicity, age, gender, and weight status. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2010) 42:2211–21. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e1fba9,

17. Aronowitz, T, and Eche, I. Parenting strategies African American mothers employ to decrease sexual risk behaviors in their early adolescent daughters. Public Health Nurs. (2013) 30:279–87. doi: 10.1111/phn.12027,

18. Barnes, AT, Young, MD, Murtagh, EM, Collins, CE, Plotnikoff, RC, and Morgan, PJ. Effectiveness of mother and daughter interventions targeting physical activity, fitness, nutrition and adiposity: a systematic review. Prev Med. (2018) 111:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.033,

19. Kulbok, PA, Bovbjerg, V, Meszaros, PS, Botchwey, N, Hinton, I, Anderson, NLR, et al. Mother–daughter communication: a protective factor for nonsmoking among rural adolescents. J Addict Nurs. (2010) 21:69–78. doi: 10.3109/10884601003777604

20. Fielding-Singh, P. Dining with dad: fathers' influences on family food practices. Appetite. (2017) 117:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.06.013,

21. Lachance-Grzela, M, and Bouchard, G. Why do women do the lion’s share of housework? A decade of research. Sex Roles. (2010) 63:767–80. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9797-z

22. Williams, DR, Lawrence, JA, and Davis, BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. (2019) 40:105–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750,

23. Bonilla-Silva, E. Rethinking racism: toward a structural interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. (1997) 62:465–80. doi: 10.2307/2657316

24. Sue, DW, Alsaidi, S, Awad, MN, Glaeser, E, Calle, CZ, and Mendez, N. Disarming racial microaggressions: microintervention strategies for targets, White allies, and bystanders. Am Psychol. (2019) 74:128–42. doi: 10.1037/amp0000296,

25. Haughton, CF, Waring, ME, Wang, ML, Rosal, MC, Pbert, L, and Lemon, SC. Home matters: adolescents drink more sugar-sweetened beverages when available at home. J Pediatr. (2018) 202:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.06.046,

26. Hilmers, A, Hilmers, DC, and Dave, J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. (2012) 102:1644–54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300865,

27. Barr-Anderson, DJ, Adams-Wynn, AW, Orekoya, O, and Alhassan, S. Socio-cultural and environmental factors that influence weight-related behaviors: focus group results from African-American girls and their mothers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2018) 15:1354. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071354,

28. Flores, RL. The determinants of health: neighborhood characteristics, obesity, and the mental health of African American adolescent girls. Open J Soc Sci. (2016) 4:126–36. doi: 10.4236/jss.2016.412012

29. Reed, M, Wilbur, J, and Schoeny, M. Parent and African American daughter obesity prevention interventions: an integrative review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2015) 26:737–60. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0103,

30. Young, MD, Plotnikoff, RC, Collins, CE, Callister, R, and Morgan, PJ. Social cognitive theory and physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. (2014) 15:983–95. doi: 10.1111/obr.12225,

31. Center for the Developing Adolescent. (n.d.). Support from parents & other caring adults. UCLA Center for the Developing Adolescent. Available online at: https://developingadolescent.semel.ucla.edu/core-science-of-adolescence/support-from-parents-and-other-caring-adults (Accessed April 25, 2025).

32. Reed, M, Dancy, B, Holm, K, Wilbur, J, and Fogg, L. Eating behaviors among early adolescent African American girls and their mothers. J Sch Nurs. (2013) 29:452–63. doi: 10.1177/1059840513491784,

33. Hughes, D, Del Toro, J, Harding, JF, Way, N, and Rarick, JRD. Trajectories of discrimination across adolescence: associations with academic, psychological, and behavioral outcomes. Child Dev. (2016) 87:1337–51. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12591,

34. Baxley, S. M., and Daniels, G. (2014). Adolescent participation in research: a model of ethnic/minority recruitment and retention. J Theor Constr Test, 18, 33–39. Available online at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=99011800&site=ehost-live.

35. Winter, SS, Page-Reeves, JM, Page, KA, Haozous, E, Solares, A, Nicole Cordova, C, et al. Inclusion of special populations in clinical research: important considerations and guidelines. J Clin Transl Res. (2018) 4:56–69 doi: 10.1111/cdev.12591

36. Al-Khudairy, L, Loveman, E, Colquitt, JL, Mead, E, Johnson, RE, Fraser, H, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 6:CD012691. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012691,

37. Resnicow, K, Taylor, R, Baskin, M, and McCarty, F. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African American adolescent females. Obesity. (2005) 13:1739–48. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.212,

38. Williamson, DA, Walden, HM, White, MA, York-Crowe, E, Newton, RL, Alfonso, A, et al. Two-year internet-based randomized controlled trial for weight loss in African-American girls. Obesity (Silver Spring). (2006) 14:1231–43. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.140,

39. Lanigan, J. Prevention of overweight and obesity in early life. Proc Nutr Soc. (2018) 77:247–56. doi: 10.1017/S0029665118000411,

40. Lynch, EB, and Kane, J. Body size perception among African American women. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2014) 46:412–4 17. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.03.002,

41. Roberts, A, Cash, TF, Feingold, A, and Johnson, BT. Are black-White differences in females' body dissatisfaction decreasing? A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. (2006) 74:1121–31. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1121,

42. Ellis, DA, Rhind, J, Carcone, AI, Evans, M, Weissberg-Benchell, J, Buggs-Saxton, C, et al. Optimizing recruitment of black adolescents into behavioral research: a multi-center study. J Pediatr Psychol. (2021) 46:611–20. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsab008,

43. Mosavel, M, Ports, KA, and Leighton-Herrmann, E. Mother–daughter dyad recruitment and cancer intervention challenges in an African American sample. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2014) 1:120–9. doi: 10.1007/s40615-014-0019-1,

44. Reed, M, Wilbur, J, Tangney, CC, Miller, AM, Schoeny, ME, and Webber-Ritchey, KJ. Development and feasibility of an obesity prevention intervention for black adolescent daughters and their mothers. J Health Eat Act Living. (2021) 1:94–107. doi: 10.51250/jheal.v1i2.35

45. Reed, M, Banks, T, Halloway, S, Julion, K, Kitsiou, S, Schoeny, M, et al. Rationale and design of a race-conscious, school-linked, pilot randomized controlled trial to improve physical activity and dietary behaviors of black adolescent daughter/mother dyads. Contemp Clin Trials. (2025) 156:107996. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2025.107996,

46. Bennett, GG, Foley, P, Levine, E, Whiteley, J, Askew, S, Steinberg, DM, et al. Behavioral treatment for weight gain prevention among black women in primary care practice: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. (2013) 173:1770–7. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9263,

47. El-Kotob, R, and Giangregorio, LM. Pilot and feasibility studies in exercise, physical activity, or rehabilitation research. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2018) 4:137. doi: 10.1186/s40814-018-0326-0,

48. Stewart, AL, Nápoles, AM, Piawah, S, Santoyo-Olsson, J, and Teresi, JA. Guidelines for evaluating the feasibility of recruitment in pilot studies of diverse populations: an overlooked but important component. Ethn Dis. (2020) 30:745–54. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.S2.745,

49. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Diabetes prevention recognition program standards and operating procedures. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes-prevention/media/pdfs/legacy/dprp-standards.pdf (Accessed October 12, 2025).

50. Tickle-Degnen, L. Nuts and bolts of conducting feasibility studies. Am J Occup Ther. (2013) 67:171–6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.006270,

51. Griffith, DM, Bergner, EM, Fair, AS, and Wilkins, CH. Using mistrust, distrust, and low trust precisely in medical care and medical research advances health equity. Am J Prev Med. (2021) 60:442–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.08.019,

52. Griffith, R, Huffhines, L, Jackson, Y, and Nowalis, S. Strategies for longitudinal recruitment and retention with parents and preschoolers exposed to significant adversity: the PAIR project as an example of methods, obstacles, and recommendations. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 110:104770. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104770,

53. Lee, RE, McGinnis, KA, Sallis, JF, Castro, CM, Chen, AH, and Hickmann, SA. Active vs. passive methods of recruiting ethnic minority women to a health promotion program. Ann Behav Med. (1997) 19:378–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02895157,

54. Grape, A, Rhee, H, Wicks, M, Tumiel-Berhalter, L, and Sloand, E. Recruitment and retention strategies for an urban adolescent study: lessons learned from a multi-center study of community-based asthma self-management intervention for adolescents. J Adolesc. (2018) 65:123–32. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.03.004,

55. Graves, D, and Sheldon, JP. Recruiting African American children for research: an ecological systems theory approach. West J Nurs Res. (2018) 40:1489–521. doi: 10.1177/0193945917704856,

56. Mendelson, T, Sheridan, SC, and Clary, LK. Research with youth of color in low-income communities: strategies for recruiting and retaining participants. Res Social Adm Pharm. (2021) 17:1110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.08.011,

57. Hartlieb, KB, Jacques-Tiura, A, Naar-King, S, Ellis, DA, Jen, KC, and Marshall, S. Recruitment strategies and the retention of obese urban racial/ethnic minority adolescents in clinical trials: the FIT families project, Michigan, 2010–2014. Prev Chronic Dis. (2015) 12:E22. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140409

58. Reed, M, Julion, W, McNaughton, D, and Wilbur, J. Preferred intervention strategies to improve dietary and physical activity behaviors among African American mothers and daughters. Public Health Nurs. (2017) 34:461–71. doi: 10.1111/phn.12339,

59. Sundell, K., and Shaughnessy, T (2017). Beginning the bachelor of science in nursing in high school: How Kentucky created a 120-credit hour nursing career pathway. Atlanta, GA. Available online at: https://www.sreb.org/sites/main/files/file-attachments/17v12_beginning_the_bsn_nursing_pathway_report.pdf?1496925461 (Accessed April 25, 2025).

60. Cunningham-Erves, J, Joosten, Y, Kusnoor, SV, Mayers, SA, Ichimura, J, Dunkel, L, et al. A community-informed recruitment plan template to increase recruitment of racial and ethnic groups historically excluded and underrepresented in clinical research. Contemp Clin Trials. (2023) 125:107064. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.107064,

61. Schulz, KF, Altman, DG, and Moher, Dthe CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel-group randomised trials. BMC Med. (2010) 8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18,

62. American Public Health Association (2025) Community health workers. Available online at: https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/member-sections/community-health-workers (Accessed November 3, 2025).

63. Ali-Faisal, SF, Colella, TJ, Medina-Jaudes, N, and Benz Scott, L. The effectiveness of patient navigation to improve healthcare utilization outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. (2017) 100:436–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.10.014,

64. Wells, KJ, Dwyer, AJ, Calhoun, E, and Valverde, PA. Community health workers and non-clinical patient navigators: a critical COVID-19 pandemic workforce. Prev Med. (2021) 146:106464. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106464,

65. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Using the CDC BMI-for-age growth charts to assess growth among children and teens aged 2 to 20 years in the United States. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/training/bmiage/index.html (Accessed April 25, 2025).

66. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013) 2013 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System questionnaire. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/pdf-ques/2013-brfss_english.pdf (Accessed April 25, 2025).

67. Drenkard, C, Easley, K, Bao, G, Dunlop-Thomas, C, Lim, SS, and Brady, T. Overcoming barriers to recruitment and retention of African-American women with SLE in behavioural interventions: lessons learnt from the WELL study. Lupus Sci Med. (2020) 7:e000391. doi: 10.1136/lupus-2020-000391,

68. George, S, Duran, N, and Norris, K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific islanders. Am J Public Health. (2014) 104:e16–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706,

69. Small, TF. Home visiting safety for home healthcare clinicians. Home Healthc Now. (2020) 38:169. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000880,

70. Dodgen, L, and Spence-Almaguer, E. Beyond body mass index: are weight-loss programs the best way to improve the health of African American women? Prev Chronic Dis. (2017) 14:E48. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.160573,

71. Rothblum, ED. Slim chance for permanent weight loss. Arch Sci Psychol. (2018) 6:63–9. doi: 10.1037/arc0000043

72. Adams, V, Gladden, A, and Craddock, J. Perceptions of health among black women in emerging adulthood: alignment with a health at every size perspective. J Nutr Educ Behav. (2022) 54:916–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2022.07.004,

73. Evans, WD, Wallace, JL, and Snider, J. Pilot evaluation of the Text4baby mobile health program. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:1031. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1031,

Keywords: responsive recruitment, Black Girls, adolescent females, mother-daughter dyads, obesity prevention, culture, race-conscious

Citation: Banks T, Julion W, Halloway S, Kitsiou S, Schoeny M, Swanson B, Webber-Ritchey K, Wilhelm K, Yeager C and Reed M (2025) Culturally responsive recruitment of Black daughter-mother dyads through community engagement. Front. Public Health. 13:1634312. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1634312

Edited by:

Lori Edwards, University of Maryland, United StatesReviewed by:

Susan Lee Mayfield-Johnson, University of Southern Mississippi, United StatesMaria Valeria Jimenez-Baez, Mexican Social Security Institute, Mexico

Copyright © 2025 Banks, Julion, Halloway, Kitsiou, Schoeny, Swanson, Webber-Ritchey, Wilhelm, Yeager and Reed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tristan Banks, dHJpc3Rhbl9iYW5rc0BydXNoLmVkdQ==

Tristan Banks

Tristan Banks Wrenetha Julion

Wrenetha Julion Shannon Halloway2

Shannon Halloway2 Kashica Webber-Ritchey

Kashica Webber-Ritchey Monique Reed

Monique Reed