- 1Yichang Special Care Hospital, Yichang, China

- 2Yichang Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders, Yichang, China

- 3Department of Psychology, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

Background: Suicidal ideation is the most significant risk factor for suicide, and suicide is the third leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 19 years. Interparental conflict has been shown to be associated with adolescents’ suicidal ideation, but the reasons for this association remain underexplored. We investigated whether adolescents’ life satisfaction accounts for this relationship, and whether perceived teacher support moderates the mediation process.

Methods: A total of 649 Chinese adolescents (52% girls; mean age = 15.59 years, SD = 0.70) completed anonymous questionnaires in their classroom to assess interparental conflict, life satisfaction, teacher support, and suicidal ideation. The data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software.

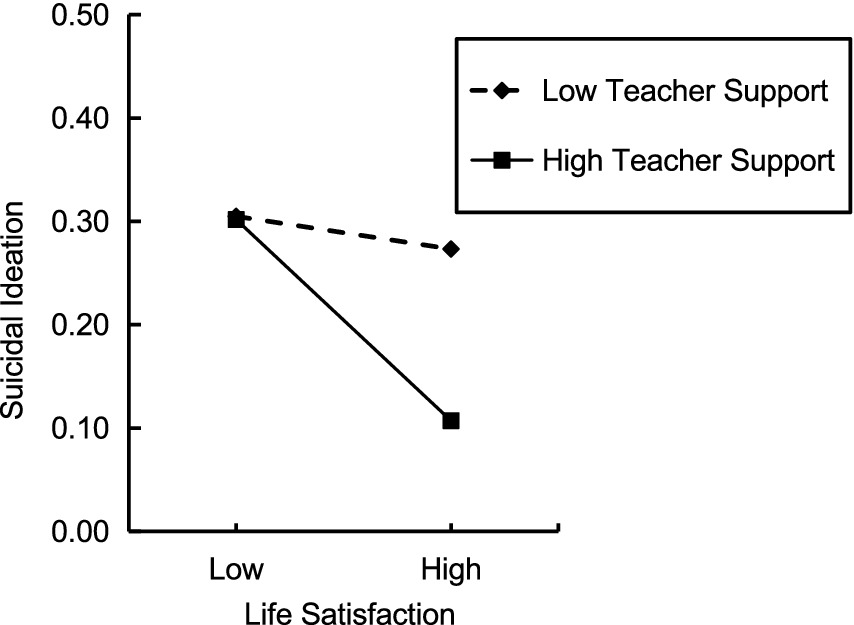

Results: The mediation analysis showed that a significant indirect relationship between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation, mediated by life satisfaction (β = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04]). The moderation analysis revealed that teacher support moderated the relationship between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation (β = −0.03, p < 0.01). The relationship between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation was significant for adolescents who perceived high teacher support (β = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.12, −0.04]) but not for those who perceived low teacher support (β = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03]).

Discussion: The study suggest that life satisfaction and teacher support are important protective factors for adolescent suicidal ideation. Life satisfaction was associated with less suicidal ideation for adolescents with high rather than low teacher support. These findings point to the importance of considering school, family, and individual factors concurrently when developing programs to prevent and reduce adolescents’ suicidal ideation.

Introduction

Suicide is the third most common cause of death among young people aged 15 to 29 (1). The issue of adolescent suicide in China is still alarming (2). Adolescence is characterized by asynchronous brain development, whereby the subcortical limbic system exhibits more accelerated maturation compared to the orbitofrontal cortex. This disproportional development can undermine rational decision-making abilities and potentially elevate the risk of suicidal behavior, driven by heightened sensation seeking and emotional dysregulation (3). Adolescence itself is a risk factor for suicidal ideation and behavior (4). Understanding the risk and protective factors associated with adolescent suicide is essential for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Suicidal ideation encompasses the contemplation of ending one’s life, even if such thoughts do not invariably culminate in an actual suicide. It is an early indicator of future suicidal actions and it is also the most sensitive and significant risk factor contributing to the final behavior (5, 6). Thus, the identification of predictors of ideation might lead to a better understanding of suicide risk, and provide adolescents with the help they need (7, 8).

The influence of interparental conflict on adolescent suicidal ideation has garnered notable attention [(e.g., 5, 9, 10)]. Given the significant emphasis on collectivism and family relations in Chinese culture, the ramifications of interparental conflict on Chinese adolescents may be particularly severe (11). According to emotional security theory (EST), exposure to destructive forms of interparental conflict (e.g., hostile; aggressive; unresolved) may endanger the child’s emotional security, potentially resulting in adjustment problems (12). Several empirical studies have shown a significant relationship between interparental conflict and adolescents’ suicidal ideation (5, 9, 10). For instance, Ai et al. (5) found that interparental conflict posed a significant risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents. Interparental conflict was shown in one study to indirectly predict adolescents’ suicidal ideation via coping-approach strategies, presence of meaning, and their joint serial effects (10).

Although there is evidence of a direct relationship between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation, the mediating effects (i.e., the pathways through which interparental conflict influences suicidal ideation) and the moderating factors (i.e., the factors that affect the strength or direction of this relationship) in this association remain largely unexplored. Most suicidal ideation research focuses on risk factors, and the exploration of protective factors is relatively rare (13). Moreover, there is a lack of research on how external environmental resources interact with individual internal resources to predict suicidal ideation. Addressing these gaps is crucial for understanding the etiology of adolescent suicidal ideation and for creating prevention strategies. In this study, we addressed two key questions: first, whether the relationship between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation can be explained in part by life satisfaction; second, whether this indirect association via life satisfaction is moderated by teacher support.

The mediating role of life satisfaction

There has been considerable research attention to negative psychological factors (e.g., substance abuse; depression) as predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation (14, 15). However, it is also crucial to include positive psychological factors as predictors of lower suicidal ideation (6). Psychologists are interested not just in pathology but also in the well-being of individuals (16). Life satisfaction, an important element of quality of life and subjective well-being, encapsulates the cognitive appraisal of one’s overall quality of life or of specific life domains (17). Life satisfaction, while generally stable over time, exhibits sensitivity to changes in life circumstances (18). We thus used life satisfaction as the indicator of adolescents’ well-being in the current study.

According to the emotional security theory [EST; (12)], interparental conflict leads to adolescents’ negative internal representations of their well-being, thereby increasing their risk of maladaptive outcomes (12). Likewise, the conservation of resources theory (19) posits that individuals strive to retain, protect, and build resources, and that negative stress events decrease an individual’s mental health due to the mediating effects of loss of resources (e.g., lower personal sense of well-being; lower sense of control) loss. In other words, lower life satisfaction may mediate the relationship between interparental conflict and adolescents’ suicidal ideation.

Consistent with these theoretical frameworks, some empirical evidence has demonstrated the mediating effect of life satisfaction in the association between negative environments and adolescent maladaptive outcomes (20, 21). Specifically, Moksnes et al. (21) found that school performance pressure was a positive predictor of Norwegian adolescents’ depressive symptoms, and that this association was mediated by life satisfaction. In a study of 3,522 adolescents in China, Chang et al. (20) found that life satisfaction partially mediated the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation. Although not yet tested, it is reasonable to expect that life satisfaction will also mediate the association between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation.

We will review prior research findings to substantiate our argument. First, adolescents who perceive more interparental conflict are more likely to report lower life satisfaction. High cohesion among family members is associated with higher parental concern for their children, fostering a harmonious family atmosphere and with higher life satisfaction among Chinese young adults (22). Similarly, Zhu et al. (23) found that the frequency of interparental conflict negatively predicted the life satisfaction of Chinese adolescents. Second, adolescents with lower levels of life satisfaction may relate to more suicidal ideation. Several studies have indicated that low life satisfaction serves as a significant predictor of suicidal ideation among adolescents (6, 20). For instance, Morales-Vives and Dueñas (6) found that, potentially due to the stress generated by the physical and emotional transitions during adolescence, Spanish adolescents reported lower life satisfaction compared to younger children, which in turn was associated with more suicidal ideation.

Therefore, building on the emotional security theory (12), the conservation of resources theory (19) and the extant literature, we propose that life satisfaction mediates the relationship between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation.

The moderating role of teacher support

There is variability in how youth are affected by interparental conflict, and further research is needed to identify protective factors that can mitigate the negative impacts of such conflict on adolescents (24). The social support resource theory (25) posits that social support, as a significant external resource, can enhance individuals’ internal resources, exhibiting a “the rich get richer” phenomenon; this mutual enrichment can improve individuals’ capacity to cope with risks. Similarly, according to the protective-protective model (26), teacher support is a crucial external protective factor for adolescents’ healthy development; it can enhance the effect of another promotive factor in producing a certain outcome, and the interaction goes beyond the alone effects of either factor. Based on these theories, we infer that the association between life satisfaction and adolescent suicidal ideation may be moderated by teacher support as an protective factor. The advantageous impact of life satisfaction may be more pronounced in adolescents who receive high levels of teacher support compared to those with low levels of support.

We have the following reasons for examining teacher support as a moderator: (a) Several studies have established teacher support as an important protective factor against adolescent suicidal ideation (27, 28); (b) Given the substantial amount of time that youth spend in educational settings, teachers are uniquely positioned to recognize signs of suicide risk and take appropriate prevention measures (29); (c) Teachers’ attitudes can be changed through suicide intervention programs (30), and as significant others who frequently interact with adolescents, they have a crucial impact on their mental health (31).

Although relatively limited, existing research has provided evidence on the moderating effect of social support in the direct relationship between promotive factors and suicidal ideation [(e.g., 32, 33)]. Specifically, Zhang et al. (33) found that for Chinese older adults with higher support from nursing, resilience was significantly associated with lower suicidal ideation. The association between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation was negatively significant among Spanish adolescents with high family support (32). Compared to peer support, teacher support is a more significant moderator and protective factor for Chinese adolescent suicidal inclination (28). Thus, we anticipate that the association between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation is stronger among adolescents with high rather than low teacher support.

Overview of the study and hypotheses

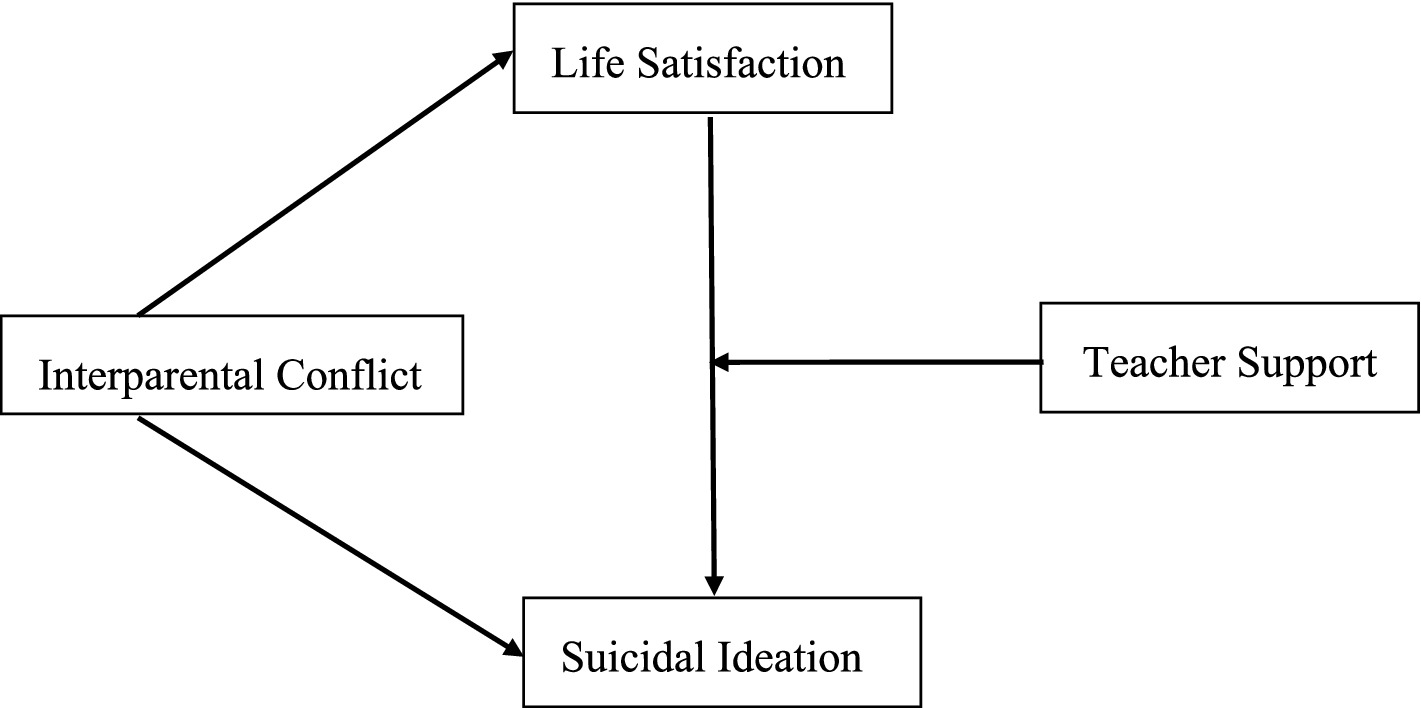

In the present study we tested a moderated mediation model to elucidate the association between adolescents’ reports of interparental conflict and their own suicidal ideation. Adolescents’ self-reported life satisfaction was tested as the mediator. Adolescents’ perception of teacher support was tested as a moderator that would enhance the second mediation link (the association between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation). Hypothesis 1: Life satisfaction will mediate the relationship between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation. Hypothesis 2: Teacher support will moderate the second link in the indirect pathway; that is, the association between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation is stronger among adolescents with high rather than low teacher support. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed research model.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of our institution (approval number AF/SC-05/02.1). Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants from two high schools in Hubei Province, China. The school administrators approved the study and informed consent was obtained from the participants prior to data collection. Assurances were provided regarding the anonymity of their responses. The questionnaires were administered in students’ classrooms by trained research assistants, who followed standardized scripts and procedural manuals to ensure accurateness in data collection. Participants who finished the full survey received a gift of five yuan (about US $0.80).

The sample constituted 649 students, with 313 boys and 336 girls. The average age of the participants was 15.59 years (SD = 0.70, range = 14–18). About half (52%) were in Grade 10, and about half (48%) were in Grade 11.

Measures

Interparental conflict

The Chinese version of the Children’s Perception of Marital Conflict Scale (34) was employed. This scale, originally in English (35) and extensively referenced in the literature, comprises 15 items designed to assess interparental conflict across three dimensions: intensity, frequency, and resolution (the latter being reverse coded to reflect effective disagreement resolution without anger or aggression). An example item is “My parents fight when they have a quarrel.” Adolescents rated the veracity of each item on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 = Not True, 2 = A Little Bit True, 3 = Sort of True, 4 = True. The average of the 15 item scores represented the degree of interparental conflict, with higher scores indicating more conflict. The scale demonstrated excellent reliability in this study (α = 0.90).

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale [SWLS; (36)] is a 5-item instrument designed to assess global life satisfaction. Respondents rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An example item is “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” This questionnaire has been utilized in many prior studies and is recognized for its reliability and validity in evaluating Chinese adolescents’ life satisfaction (37). A higher cumulative score on the SWLS indicates a greater level of life satisfaction. In the present study, Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.75.

Teacher support

The Chinese version of Perceived Social Support Scale (38) was utilized in this study. Perceived social support from family, friends, and teacher are measured separately, and we only used the four items on the teacher support subscale. A sample item is “My teacher helps me when I have trouble.” Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was good (α = 0.84).

Suicidal ideation

We used a single item to measure adolescents’ suicidal ideation: “During the last 6 months, I have thought about killing myself.” Respondents rated this item on a three-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 2 (frequently). The item we used has been used in previous studies on adolescents attending high school in China [(e.g., 5, 39)].

Control variables

Chang et al. (2) found that the prevalence of suicidal ideation were significantly higher among Chinese girls than among boys due to the differences in susceptibility to psychosocial distress and emotional issues. The prevalence rates of suicidal ideation significantly increased with age in Chinese adolescents (40). Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that family financial hardships may heighten adolescents’ risk for suicide (41). Therefore, we included gender (dummy coded as 0 for girl and 1 for boy), age (as a continuous variable) and family financial stress as covariates in the analyses. The Family Financial Stress Scale was compiled by Chinese scholars Wang et al. (42). It includes 5 items, such as “My family does not have any remaining money for family entertainment.” Participants are required to report the frequency of economic pressure in their families over the past 12 months. A 4-point scale is used, ranging from “never” (1 point) to “always” (4 points). The average score of all items is calculated, with higher scores indicating greater family financial stress. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.83.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). First, descriptive statistics were generated for the primary study variables, followed by Pearson correlation analysis to examine the relationships among variables. Subsequently, the PROCESS macro (43), a widely used tool for examining complex models involving moderation and mediation effects, was employed to test the moderated mediation model with 5,000 bias-corrected bootstrap samples. These bootstrap samples were used to estimate 95% confidence intervals (CIs), with an effect considered statistically significant if the 95% CI did not include zero. Specifically, Model 4 of the macro was used to test a mediation model with life satisfaction as the mediator. Then, Model 14 of the macro was employed to examine an integrated model with life satisfaction as the mediator and teacher support as the moderator.

Results

Variance inflation factor and common method Bias test

Prior to main analyses, we conducted multicollinearity diagnostics. Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) for all predictor variables were well below the conventional threshold of 5, indicating no significant multicollinearity issues. Since the data were collected via self-report, concerns about common method bias may arise. Harman’s single-factor test revealed that there were 7 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, and the first factor accounted for 21.9% of the variance—below the critical threshold of 40%. Thus, the threat of common method bias appears negligible.

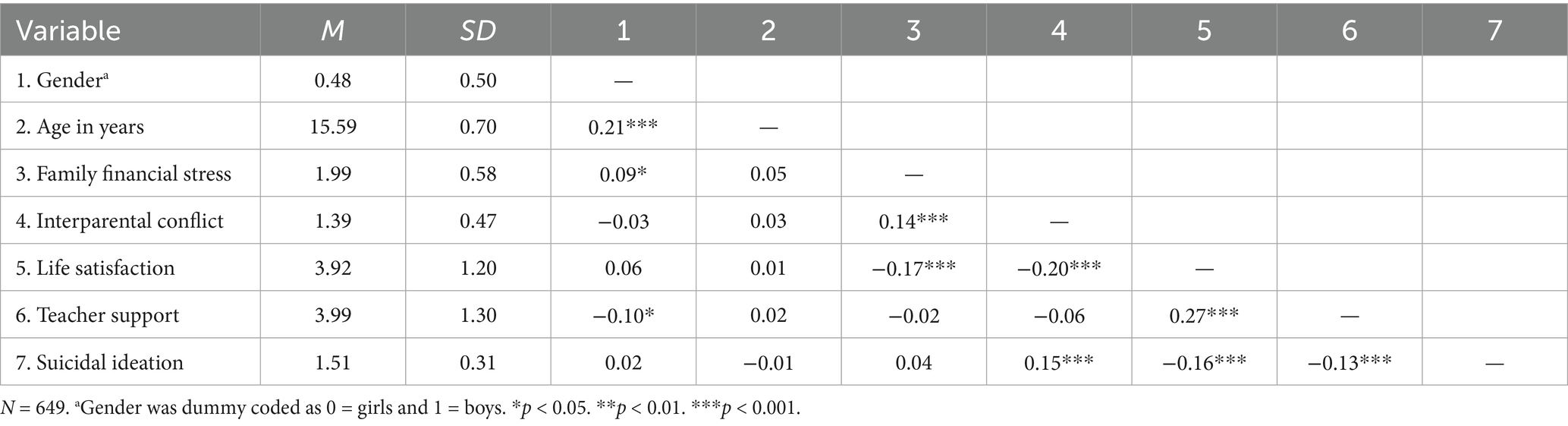

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents univariate and bivariate statistics, including means and standard deviations, for all study variables. Within the total sample, 21.9% (n = 142) of participants reported experiencing suicidal ideation in the preceding 6 months. Specifically, 71.8% (n = 507) of participants gave a rating of 0 (never), 20.2% (n = 131) of participants gave a rating of 1 (occasionally), and 1.7% (n = 11) of participants gave a rating of 2 (frequently). Interparental conflict was positively correlated with suicidal ideation. Both life satisfaction and teacher support were negatively correlated with suicidal ideation. Teacher support was positively correlated with life satisfaction. Results were as expected.

Mediation effect of life satisfaction

Controlling for gender, age and family financial stress, the 95% confidence interval derived via bootstrapping substantiated a significant indirect relationship between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation, mediated by life satisfaction (β = 0.02, 95% CI [0.01, 0.04]). Specifically, interparental conflict demonstrated a significant direct relationship with suicidal ideation (β = 0.12, p < 0.001). Interparental conflict was negatively correlated with life satisfaction (β = −0.37, p < 0.001), and life satisfaction negatively predicted suicidal ideation (β = −0.05, p < 0.001). These results supported H1.

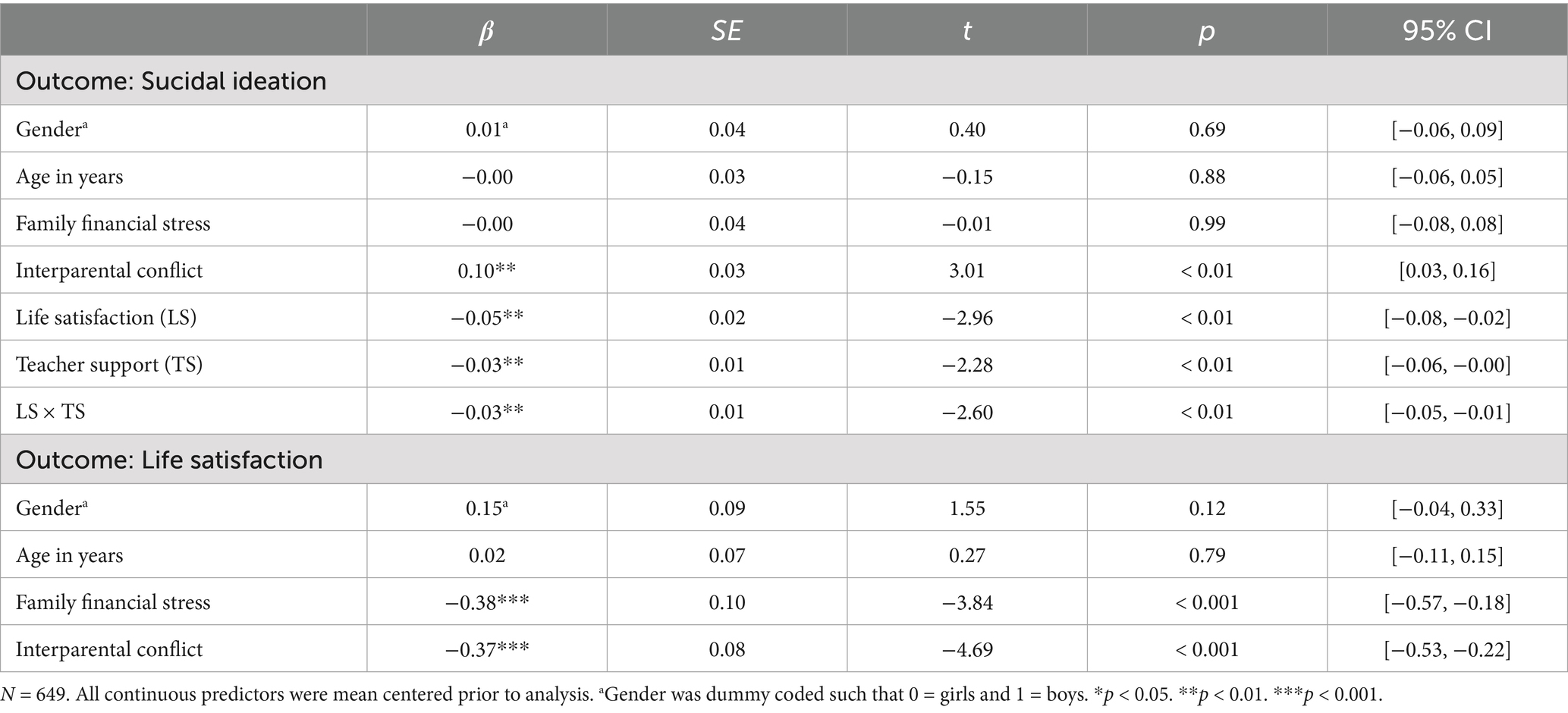

Moderated mediation effects

The results of the moderated mediation model analysis are reported in two parts. First we report the moderation effects. Second, we report the mediation effects (conditional indirect effects). Table 2 shows that the interaction effect of life satisfaction and teacher support on suicidal ideation was significant after controlling for gender, age, and family financial stress, β = −0.03, p < 0.01. Thus, teacher support moderated the association between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation.

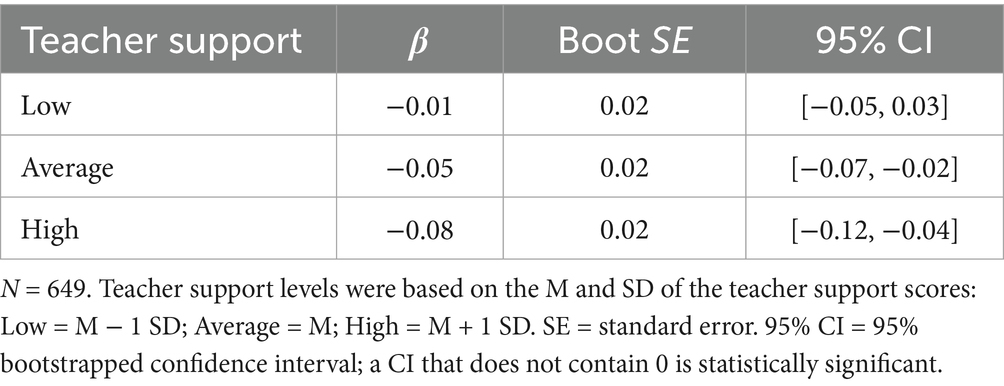

Table 3 shows the mediation effects at +1 SD, M, and −1 SD of teacher support scores. All slopes were negative. However, the 95% confidence interval included zero (was non-significant) when the teacher support score was one standard deviation below the mean, and the 95% confidence interval excluded zero (was significant) when the teacher support score was at the mean and at one standard deviation above the mean. Specifically, the indirect effect of interparental conflict on suicidal ideation through life satisfaction was significant for adolescents with a higher level of teacher support (+1 SD; β = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.12, −0.04]) and an average level of support (M; β = −0.05, 95% CI [−0.07, −0.02]), but was non-significant for adolescents with a lower level of teacher support (−1 SD; β = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.03]). These results supported H2 for purposes of illustration. Figure 2 depicts this interaction when teacher support scores were low (M– 1 SD), average (M) and high (M + 1 SD).

Figure 2. The association between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation at different levels of teacher support. Teacher support levels were created based on the M and SD of the teacher support scores: Low = M − 1 SD; High = M + 1 SD.

Discussion

We developed and evaluated a moderated mediation model based on an integration of existing theories (i.e., EST, the conservation of resources theory, and the protective-protective model) to elucidate the interconnections between suicidal ideation and various influencing factors, including a family factor (interparental conflict), a school factor (teacher support), and an individual-level factor (life satisfaction). Our findings indicated that life satisfaction mediated the relationship between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation, with this indirect effect being moderated by the presence of teacher support. The mediating effect was significant among adolescents with a high or average level of teacher support, but not among adolescents with a low level of teacher support.

In our sample, 21.9% (n = 142) of adolescents reported suicidal ideation in the past 6 months; 1.7% (n = 11) reported frequent thoughts, and 20.2% (n = 131) reported occasional thoughts. These prevalence estimates are higher than those reported in prior studies of Chinese adolescents (5, 39), a difference that may reflect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recent evidence documents worsening adolescent mental health and increases in suicidal ideation and self-harm during and following the COVID-19 pandemic (44). These results emphasize the heightened severity of adolescent suicidal risk in the pandemic context and the imperative for early detection and intervention in the post-pandemic period.

Adolescent life satisfaction mediated the relationship between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation. This finding is congruent with EST (12), the conservation of resources theory (19) and previous research (18, 20, 23). Adolescence is important for the development of internalizing and externalizing problems, and individuals at this stage are particularly sensitive to psychosocial stressors (45). Among the various family stressors, interparental conflict poses the most severe stress on adolescents (18). Interparental conflict can deplete adolescents’ resources, such as parental emotional availability, sensitivity, belongingness, and sense of well-being, and the loss of these resources ultimately impacts mental health (12, 19). Adolescents’ need for belongingness might not be fulfilled in an environment with interparental conflict, and intrinsic motivation diminishes (46). Low intrinsic motivation might in turn reduce creativity and life satisfaction, ultimately exerting a negative impact on mental health (46).

Furthermore, adolescence is a transformative stage of life, characterized by numerous physical, cognitive, and psychosocial changes, and is important for the development of self-identity (47). For adolescents who have developed the ability to self-evaluate, prolonged exposure to high levels of interparental conflict may be closely associated with negative internal self-evaluations and experiences (48). Such negative self-evaluation is related to lower life satisfaction among adolescents (49). Shneidman (50) asserted that low life satisfaction can elevate psychache, and when this psychache exceeds an individual’s tolerance it may lead to suicide as a means of escaping the distress.

Our findings substantiate the assumption that teacher support influences the indirect relationship between interparental conflict and adolescent suicidal ideation. Consistent with the protective-protective model (26), we found that life satisfaction was associated with less suicidal ideation for adolescents with high rather than low teacher support. Person-centered theory (51) can also explain our findings. Rogers asserted that a supportive interpersonal environment (e.g., understanding and support from others) helps individuals in more effectively identifying and utilizing their own resources (e.g., life satisfaction) to cope with various psychological problems (51). In other words, life satisfaction, serving as an individual resource, may have its protective function strengthened due to high levels of teacher support. A good teacher support system can provide favorable environmental conditions for the development of adolescents’ life satisfaction (52, 53).

In addition, Pluess and Belsky (54) proposed the concept of vantage sensitivity, which refers to some individuals benefiting more than others from a positive environmental experience or exposure. This concept is consistent with evidence that American high school students who reported higher levels of life satisfaction benefited more from numerous positive factors, such as higher social support (55). Hence, it is possible that adolescents with higher life satisfaction are more likely to benefit from teacher support, which is associated with less suicidal ideation among adolescents (28). Because adolescents spend most of their time at school (56), teachers play a crucial role in preventing adolescent suicide (30).

However, person-centered theory (51) suggests that low-level interpersonal support greatly restricts individuals’ potential to utilize their own resources to cope with risks. Similarly, social support resource theory (25) indicates that resources tend to enrich each other, but a lack of social support can lead to a cycle of resource loss, thereby reducing an individual’s coping ability. These may explain why the negative correlation between life satisfaction and suicidal ideation was not significant among adolescents with a low level of teacher support. Fergus and Zimmerman (26) pointed out that support from a nonparental adult mentor, as a protective resource for adolescents, the protective effect may not significant when lack of it (26). This finding is similar to the results of a recent study found that the relationship between emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation was significant for Spanish adolescents with medium or high family support but not significant for those with low family support (32).

Teachers can offer crucial intervention and support to adolescents experiencing suicidal ideation (57). Indeed, 36.4% of teachers have reported instances of students (from kindergarten to twelfth grade) revealing suicidal ideation to them (30). Despite this critical role, many teachers may feel reluctant to intervene due to the significant burden and responsibility associated with it (30). Following a student’s suicide, over one-third of primary and secondary school teachers reported a decline in their professional confidence and a need for more support (58). Therefore, it is imperative to deepen our understanding of the importance teachers attribute to their role and give teachers support they need in suicide prevention.

It is noteworthy that the protective role of teacher support against student suicidal ideation may manifest culturally specific functions. In Chinese collectivist culture, relational dependence and intimacy in teacher-student relationships are more socially acceptable and perceived as characteristics of better social adaptation; whereas in Western countries, students’ relational dependence on teachers may conflict with cultural values emphasizing autonomy and independence, thus being regarded as behaviors to be avoided (59). Chen et al. (60) demonstrated that compared to Dutch students, Chinese students exhibit stronger desire to seek validation and assistance from teachers when experiencing distress, with the safe haven function in teacher-student relationships being more prominent in collectivist cultural contexts.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations warrant consideration in interpreting the results. First, the cross-sectional design is a major limitation of this study. Future research should employ longitudinal tracking or experimental interventions (for example, programs aimed at improving life satisfaction) to assess causal impacts on adolescent suicidal ideation. Furthermore, adolescents in early, middle, and late stages differ meaningfully in life satisfaction, social support, and emotion-regulation capacities (53, 61). Therefore, the effect of interparental conflict on suicidal ideation, the mediating role of life satisfaction, and the moderating influence of teacher support may be age-dependent. We recommend that future studies adopt longitudinal, stage-specific designs to examine developmental variation in these mediation and moderation processes, which would enable the development of age-tailored prevention and intervention measures.

Second, adolescents are mostly engaged with home and school settings and overall assessments of life satisfaction may obscure differences in adolescents’ relationships with their family and school (62). Chang et al. (20) found that satisfaction with family life exerted the greatest indirect effect in the relationship between cyberbullying and suicidal ideation, followed by satisfaction with peers and academic performance. Future research is recommended to further compare the potential differential effects of various dimensions of life satisfaction (e.g., family life satisfaction, campus life satisfaction) in the association between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation.

Third, this study was conducted in a school-based Chinese sample; therefore, the conclusions of this study may primarily apply to non-clinical adolescent populations in similar cultural contexts. After all, the collectivist culture in China and the independent culture in the West may lead to differences in students’ attitudes and responses toward teacher support (59, 60). Future research should examine the current model in clinical samples and across diverse cultural backgrounds, while also taking into account cultural variations in teacher-student interactions to enhance the applicability and representativeness of the findings.

Fourth, this study concentrates on the relationship between interparental conflict and suicidal ideation; however, other factors may also constitute significant risk factors for suicidal ideation, such as suicide contagion and cyberbullying. Recent research shows that suicide contagion substantially increases the likelihood of suicidal ideation among adolescents (63). Additionally, Maurya et al. (64) found that adolescent cyberbullying victims were at higher risk of suicidal ideation. Consequently, future studies could control for these variables and further examine the relationship between interparental conflict, life satisfaction, and suicidal ideation.

Finally, this study used a single-item measure to assess the frequency of suicidal ideation. Although empirical findings support the validity of single-item assessments for suicidal ideation frequency (65), multi-item instruments can more comprehensively capture the severity, frequency, and qualitative features of suicidal ideation. We recommend future studies use validated multi-item scales [e.g., the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; (66)] to obtain multidimensional and more nuanced measures of suicidal ideation.

Implications

Our findings make several contributions to the literature and have practical implications. First, the results highlight teacher support as a protective factor in predicting suicidal ideation. This extension to the literature is consistent with the call to identify positive psychological factors that are associated with lower suicide risk, not only negative psychological factors that predict higher risk (6, 13).

Second, this study confirms the importance of interactions between multiple ecosystems. The ecological systems theory (67) posits that the mental health of adolescents is influenced by the combined effects of microsystems (such as family and school) and individual characteristics. These factors do not exist in isolation but are intertwined and mutually influential. Suicide is caused by the complex interplay of multiple factors, and prevention strategies should consider broader personal and ecological aspects (68). This study offers a nuanced perspective that integrates personal, family, and school contexts. This comprehensive perspective facilitates a thorough understanding of the factors influencing adolescent suicidal ideation.

Third, our findings suggest that mitigating interparental conflict may contribute to a decrease in adolescents’ suicidal ideation. Interventions that include a focus on suicidal ideation (such as interventions for depression) could include a component for youth and a component for parents. Grych et al. (69) found that self-blame mediated the association between interparental conflict and adolescents’ internalizing problems. Cognitive therapy could help youth to change their assumptions about being to blame for their parents’ destructive conflict or being responsible to fix the problem. Parents could be helped to reduce destructive forms of conflict and increase conflict resolution. Adolescents’ ability to regulate emotions can potentially be enhanced by witnessing constructive conflicts between their parents (12). Encouraging couples to reassess conflicts with their partners is also a concise yet effective approach that can reduce conflicts and enhance marital quality (70).

Fourth, our research also points to life satisfaction as a possible mechanism through which interparental conflict is correlated with adolescent suicidal ideation. This information can be helpful for practitioners in conducting individual therapy with adolescents and in designing targeted interventions that include a component related to life satisfaction. Numerous environmental, familial, and social factors contribute to youth life satisfaction. These include maintaining a healthy lifestyle, achieving good physical health, engaging in regular exercise, participating in sports, living in a secure neighborhood, infrequent relocations, good parental relationships and social support (71).

Finally, it should be noted that in our study, life satisfaction predicted lower suicidal ideation more strongly for students with high teacher support than for those with low teacher support. This suggests a need for teacher training to provide support for adolescents. Considering that many teachers feel reluctant to intervene, training programs for teachers in adolescent suicide prevention should focus on enhancing teachers’ self-efficacy and positive outcome expectations (30). Together, the results suggest that suicide prevention programs should focus not only on the individual adolescent but also on the school and family.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Yichang Special Care Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

LX: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZS: Writing – review & editing, Software, Supervision, Methodology. BX: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Yichang Clinical Research Center for Mental Disorders and the Institute of Mental Health, Three Gorges University (Grant No. YCXL-23-07).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1728911.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. World Health Organization. (2024). Suicide. Available online at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (Accessed January 24, 2025).

2. Chang, Q, Shi, Y, Yao, S, Ban, X, and Cai, Z. Prevalence of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and suicide attempts among children and adolescents under 18 years of age in mainland China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. (2024) 25:2090–102. doi: 10.1177/15248380231205828

3. Méndez-Bustos, P, Fuster-Villaseca, J, Lopez-Castroman, J, Jiménez-Solomon, O, Olivari, C, and Baca-Garcia, E. Longitudinal trajectories of suicidal ideation and attempts in adolescents with psychiatric disorders in Chile: study protocol. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e051749. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051749

4. Sallee, E, Cazares-Cervantes, A, and Ng, KM. Interpersonal predictors of suicide ideation and attempt among middle adolescents. Professional Counselor. (2022) 12:1–16. doi: 10.15241/es.12.1.1

5. Ai, T, Xu, Q, Li, X, and Li, D. Interparental conflict and Chinese adolescents suicide ideation and suicide attempts: the mediating role of peer victimization. J Child Fam Stud. (2017) 26:3502–11. doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0837-y

6. Morales-Vives, F, and Dueñas, JM. Predicting suicidal ideation in adolescent boys and girls: the role of psychological maturity, personality traits, depression and life satisfaction. Span J Psychol. (2018) 21:1–12. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2018.12

7. Gao, F, Bai, X, Zhang, P, and Cao, H. A meta-analysis of the relationship between parenting styles and suicidal ideation in Chinese adolescents. Psychol Dev Educ. (2023) 39:97–108. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2023.01.11

8. Park, S. Predictors of suicidal ideation in late childhood and adolescence: a 5 year follow up of two nationally representative cohorts in the Republic of Korea. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2013) 43:81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00129.x

9. Mushtaque, I, Rizwan, M, Muneer, K, Abbas, M, Khan, AA, Fatima, SM, et al. Inter-parental conflict’s persistent effects on adolescent psychological distress, adjustment issues, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 lockdown. Omega. (2024) 88:919–35. doi: 10.1177/00302228211054316

10. Zhang, R, Li, D, Chen, F, Ewalds-Kvist, B, and Liu, S. Interparental conflict relative to suicidal ideation in Chinese adolescents: the roles of coping strategies and meaning in life. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1010. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01010

11. Chao, R, and Tseng, V. Parenting of Asians In: MH Bornstein, editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 4: Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd ed. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers (2002). 59–93.

12. Davies, PT, and Cummings, EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: an emotional security hypothesis. Psychol Bull. (1994) 116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387

13. Siegmann, P, Teismann, T, Fritsch, N, Forkmann, T, Glaesmer, H, Zhang, XC, et al. Resilience to suicide ideation: a cross-cultural test of the buffering hypothesis. Clin Psychol Psychother. (2018) 25:1–9. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2118

14. Poorolajal, J, Haghtalab, T, Farhadi, M, and Darvishi, N. Substance use disorder and risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide death: a meta-analysis. J Public Health. (2016) 38:e282–91. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv148

15. Ribeiro, JD, Huang, X, Fox, KR, and Franklin, JC. Depression and hopelessness as risk factors for suicidal ideation, attempts and death: Meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Br J Psychiatry. (2018) 212:279–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.27

16. Johal, DS, and Sharma, M. Suicide ideation and life satisfaction among adolescents: a correlational study. IOSR J Human Soc Sci. (2016) 21:23–8. doi: 10.9790/0837-21122328

17. Huebner, ES, Suldo, SM, and Valois, RF. Children’s life satisfaction In: L Lippman and KA Moore, editors. What do children need to flourish? New York: Springer Publishing Company (2005). 41–59.

18. Chappel, AM, Suldo, SM, and Ogg, JA. Associations between adolescents’ family stressors and life satisfaction. J Child Fam Stud. (2014) 23:76–84. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9687-9

19. Hobfoll, SE. Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. (1989) 44:513–24.

20. Chang, Q, Xing, J, Ho, R, and Yip, R. Cyberbullying and suicide ideation among Hong Kong adolescents: the mitigating effects of life satisfaction with family, classmates and academic results. Psychiatry Res. (2019) 274:269–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.054

21. Moksnes, UK, Løhre, A, Lillefjell, M, Byrne, DG, and Haugan, G. The association between school stress, life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescents: life satisfaction as a potential mediator. Soc Indic Res. (2016) 125:339–57. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0842-0

22. Ni, L, Li, X, and Wang, Y. The impact of family environment on the life satisfaction among young adults with personality as a mediator. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2021) 120:105653. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105653

23. Zhu, Y, Zhang, H, and Zhang, X. The relationship between interparental conflicts and adolescents’ life satisfaction: the mediating effect of adolescents’ behavioral response. Stud Psychol Behav. (2020) 18:645–51. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0628.2020.05.011

24. Wu, Y. Research progress and prospect of interparental conflict and adolescent behavioral problems. Adv Psychol. (2022) 12:537–43. doi: 10.12677/AP.2022.122061

25. Hobfoll, SE, Freedy, J, Lane, C, and Geller, P. Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. J Soc Pers Relat. (1990) 7:465–78.

26. Fergus, S, and Zimmerman, MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. (2005) 26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357

27. De Luca, SM, Wyman, P, and Warren, K. Latina adolescent suicide ideation and attempts: associations with connectedness to parents, peers, and teachers. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2012) 42:672–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00121.x

28. Lv, S, Wang, Y, Wang, X, Guo, X, and Yao, X. Parenting rejection styles and suicidal inclination of adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Psychol Dev Educ. (2022) 38:869–78. doi: 10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2022.06.13

29. Torok, M, Calear, AL, Smart, A, Nicolopoulos, A, and Wong, Q. Preventing adolescent suicide: a systematic review of the effectiveness and change mechanisms of suicide prevention gatekeeping training programs for teachers and parents. J Adolesc. (2019) 73:100–12. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.04.005

30. Stickl Haugen, J, Sutter, CC, Tinstman Jones, JL, and Campbell, LO. Teachers as youth suicide prevention gatekeepers: an examination of suicide prevention training and exposure to students at risk of suicide. Child Youth Care Forum. (2022) 52:583–601. doi: 10.1007/s10566-022-09699-5

31. Griffin, AM, Sulkowski, ML, Bámaca-Colbert, MY, and Cleveland, HH. Daily social and affective lives of homeless youth: what is the role of teacher and peer social support? J Sch Psychol. (2019) 77:110–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.09.004

32. Galindo-Domínguez, H, and Losada, D. Emotional intelligence and suicidal ideation in adolescents: the mediating and moderating role of social support. Rev Psicol Didact. (2023) 28:125–34. doi: 10.1016/j.psicod.2023.02.001

33. Zhang, D, Wang, R, Zhao, X, Zhang, J, Jia, J, Su, Y, et al. Role of resilience and social support in the relationship between loneliness and suicidal ideation among Chinese nursing home residents. Aging Ment Health. (2021) 25:1262–72. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1786798

34. Chi, LP, and Xin, ZQ. The revision of children’s perception of marital conflict scale. Chin Ment Health J. (2003) 17:554–6. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2003.08.013

35. Grych, JH, Seid, M, and Fincham, FD. Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: the children’s perception of interparental conflict scale. Child Dev. (1992) 63:558–72.

36. Diener, E, Emmons, RS, Larsen, RJ, and Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. (1985) 49:71–5.

37. You, Z, Song, J, Wu, C, Qin, P, and Zhou, Z. Effects of life satisfaction and psychache on risk for suicidal behaviour: a cross sectional study based on data from Chinese undergraduates. Br Med J Open. (2014) 4:e004096. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004096

38. Chen, W, Lu, C, Yang, X, and Zhang, J. A multivariate generalizability analysis of perceived social support scale. Psychol Explor. (2016) 36:75–8. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5184.2016.01.014

39. Peng, W, Li, D, Li, X, Jia, J, and Xiao, J. Peer victimization and adolescents’ suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a moderated mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 112:104888. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104888

40. Liu, X, Tein, JY, Zhao, Z, and Sandler, IN. Suicidality and correlates among rural adolescents of China. J Adolesc Health. (2005) 37:443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.027

41. Kim, S, Park, J, Lee, H, Lee, H, Woo, S, Kwon, R, et al. Global public concern of childhood and adolescence suicide: a new perspective and new strategies for suicide prevention in the post-pandemic era. World J Pediatr. (2024) 20:872–900. doi: 10.1007/s12519-024-00828-9

42. Wang, J, Li, D, and Zhang, W. Adolescence’ family finacial stress and social adaptation: coping efficacy of compensatory, mediation, and moration effects. J Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences). (2010) 4:22–32.

43. Hayes, AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press (2013).

44. Close, J, Arshad, SH, Soffer, SL, Lewis, J, and Benton, TD. Adolescent health in the post-pandemic era: evolving stressors, interventions, and prevention strategies amid rising depression and suicidality. Pediatr Clin. (2024) 71:583–600. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2024.04.002

45. March-Llanes, J, Marqués-Feixa, L, Mezquita, L, Fafianás, L, and MoyaHigueras, J. Stressful life events during adolescence and risk for externalizing and internalizing psychopathology: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. (2017) 26:1409–22. doi: 10.1007/S00787-017-0996-9

46. Ryan, RM, and Vansteenkiste, M. Self-determination theory In: RM Ryan, editor. The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2023). 3–30.

47. Zhang, Y, and Qin, P. Comprehensive review: understanding adolescent identity. Stud Psycholog Sci. (2023) 1:17–31. doi: 10.56397/SPS.2023.09.02

48. Wu, Y, Deng, L, Zhang, X, and Kong, R. Inter-parental conflict and parent-adolescent communication and adolescents’ self-development. Chin J Clin Psych. (2014) 22:1091–4. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2014.06.030

49. Szcześniak, M, Bajkowska, I, Czaprowska, A, and Sileńska, A. Adolescents’ self-esteem and life satisfaction: communication with peers as a mediator. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:3777. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19073777

50. Shneidman, ES. Anodyne psychotherapy for suicide: a psychological view of suicide. Clin Neuropsychiatry: J Treatment Evaluation. (2005) 2:7–12. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-47976-7_13

51. Rogers, C. On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1961).

52. Koyuncu Dikilitaş, K, Sanberk, İ, and Çolakkadıoğlu, O. The relationship between life satisfaction and perceived social support in the single parent adolescents. Int J Eurasian Educ Culture. (2023) 8:2921–40. doi: 10.51982/bagimli.969479

53. Li, B, and Bian, Y. Junior middle school students’ life satisfaction and effect of social support and self-esteem: 3 years follow up. Chin J Clin Psych. (2016) 24:900–4. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.05.029

54. Pluess, M, and Belsky, J. Vantage sensitivity: individual differences in response to positive experience. Psychol Bull. (2013) 139:901–16. doi: 10.1037/a0030196

55. Suldo, SM, and Huebner, ES. Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Soc Indic Res. (2006) 78:179–203. doi: 10.1007/s11205-005-8208-2

56. Mo, PK, Ko, TT, and Xin, MQ. School-based gatekeeper training programmes in enhancing gatekeepers’ cognitions and behaviors for adolescent suicide prevention: a systematic review. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. (2018) 12:1–24. doi: 10.1186/s13034-018-0233-4

57. Ross, V, Kolves, K, and De Leo, D. Teachers’ perspectives on preventing suicide in children and adolescents in schools: a qualitative study. Arch Suicide Res. (2017) 21:519–30. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2016.1227005

58. Kolves, K, Ross, V, Hawgood, J, Spence, S, and De Leo, D. The impact of a student’s suicide: teachers’ perspectives. J Affect Disord. (2017) 207:276–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.058

59. Spilt, JL, and Koomen, HMY. Three decades of research on individual teacher-child relationships: a chronological review of prominent attachment-based themes. Front Educ. (2022) 7:920985. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.920985

60. Chen, M, Zee, M, Koomen, HM, and Roorda, DL. Understanding cross-cultural differences in affective teacher-student relationships: a comparison between Dutch and Chinese primary school teachers and students. J Sch Psychol. (2019) 76:89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.011

61. Zimmermann, P, and Iwanski, A. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. Int J Behav Dev. (2014) 38:182–94. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515405

62. Moore, PM, Huebner, ES, and Hills, KJ. Electronic bullying and victimization and life satisfaction in middle school students. Soc Indic Res. (2012) 107:429–47. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9856-z

63. Mitchell, KJ, Banyard, V, Ybarra, ML, Jones, LM, Colburn, D, Cerel, J, et al. Understanding contagion of suicidal ideation: the importance of taking into account social and structural determinants of health. Mental Health Sci. (2025) 3:e70029. doi: 10.1002/mhs2.70029

64. Maurya, C, Muhammad, T, Dhillon, P, and Maurya, P. The effects of cyberbullying victimization on depression and suicidal ideation among adolescents and young adults: a three year cohort study from India. BMC Psychiatry. (2022) 22:599. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04238-x

65. Miranda, R, Ortin, A, Scott, M, and Shaffer, D. Characteristics of suicidal ideation that predict the transition to future suicide attempts in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. (2014) 55:1288–96. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12245

66. Campos, AI, Van Velzen, LS, Veltman, DJ, Pozzi, E, Ambrogi, S, Ballard, ED, et al. Concurrent validity and reliability of suicide risk assessment instruments: a meta-analysis of 20 instruments across 27 international cohorts. Neuropsychology. (2023) 37:315–29. doi: 10.1037/neu0000850

68. Arafat, SY, and Saleem, T. Suicide in Bangladesh: an ecological systems analysis. Brain Behavior. (2025) 15:e70233. doi: 10.1002/brb3.70233

69. Grych, JH, Fincham, FD, Jouriles, EN, and McDonald, R. Interparental conflict and child adjustment: testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Dev. (2000) 71:1648–61. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00255

70. Finkel, E, Slotter, EB, Luchies, LB, Walton, GM, and Gross, JJ. A brief intervention to promote conflict reappraisal preserves marital quality over time. Psychol Sci. (2013) 24:1595–601. doi: 10.1177/0956797612474938

Keywords: interparental conflict, life satisfaction, teacher support, suicidal ideation, adolescents

Citation: Xu L, She Z and Xu B (2025) Interparental conflict and adolescents’ suicidal ideation: life satisfaction as a mediator and teacher support as a moderator. Front. Public Health. 13:1637974. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1637974

Edited by:

Wulf Rössler, Charité University Medicine Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Louziela Masana, Cavite State University, PhilippinesButiu Otilia, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Xu, She and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhuang She, emh1YW5nLnNoZUBuanUuZWR1LmNu Baohua Xu eGlhb3lpeHViYW9odWFAc29odS5jb20=

Lu Xu

Lu Xu Zhuang She

Zhuang She Baohua Xu1,2*

Baohua Xu1,2*