Abstract

Background:

Sleep disturbances are common among older adults. While pharmacological treatments may offer short-term relief, they are often associated with adverse effects. Non-pharmacological interventions are thus urgently needed. Qigong, a traditional Chinese practice known for its safety and adaptability, has gained attention as a potential intervention to improve sleep. This study aims to systematically review and meta-analyze the existing evidence regarding the effects of Qigong on sleep quality in older adults.

Methods:

Seven databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang) were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published up to October 8th, 2025. The primary outcome was the total score of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and its subcomponents. The methodological quality was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4 and R version 4.2.0.

Results:

We included 15 RCTs involving 1,074 participants. Low certainty of evidence showed that Qigong significantly improved sleep quality compared to control groups, as measured by PSQI total score (MD = −2.47, 95% CI [−3.09, −1.85], p < 0.001). Substantial heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 82.3%). Subgroup analyses showed that Baduanjin demonstrated significant improvement in sleep quality (MD = −2.89, 95% CI [−3.39, −2.39], p < 0.001), while Wuqinxi did not (MD = −0.64, 95% CI [−3.74, 2.46], p = 0.68). Positive effects were observed in participants with sleep disturbances (MD = −3.30, 95% CI [−4.62, −1.98], p < 0.001), depression (MD = −1.96, 95% CI [−3.01, −0.90], p = 0.0003), and hypertension (MD = −2.61, 95% CI [−3.02, −2.20], p < 0.001). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results. However, the overall certainty of the evidence was rated as moderate to low due to the high heterogeneity and risk of bias in some studies.

Conclusion:

Qigong, particularly Baduanjin, may effectively improve sleep quality in older adults. Nevertheless, given the methodological limitations and heterogeneity of the included studies, further high-quality research is needed to validate these findings and inform clinical practice.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024621360, identifier: CRD42024621360.

1 Introduction

In recent years, global population aging has emerged as a major public health challenge. Aging is associated with various physiological and psychological changes, including a decline in sleep quality. Compared to younger individuals, older adults typically experience less restorative sleep, are more likely to wake up early, and suffer from fragmented sleep patterns (1, 2). Neuroimaging studies suggest that the global brain network may be altered in older adults with poor sleep quality (3). Additional risk factors such as female gender, depressed mood, and chronic physical illness further contribute to sleep disturbances in this population (4). Moreover, older adults are more likely to experience chronic diseases and mental health disorders (5, 6), which can lead to significant physical, emotional, and financial burdens.

Although pharmacological treatments for insomnia—such as eszopiclone, zolpidem, and suvorexant—may offer short-term benefits, they are often associated with adverse effects, including cognitive impairment, behavioral changes, and an increased risk of falls (7). Due to these risks, particularly in older populations, there is growing interest in non-pharmacological approaches to improve sleep (8). Exercise-based interventions have demonstrated positive effects on sleep quality in older adults (9), with recent systematic evidence further supporting the efficacy of diverse modalities—including aerobic, resistance, and mind-body exercises such as Tai Chi, Qigong, and Baduanjin—in improving sleep quality among older women (10). One such approach is Qigong, a traditional Chinese mind-body exercise that has received increasing attention. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), “qi” refers to the vital energy that sustains life, while “gong” refers to the cultivation or regulation of this energy through practice (11). The history of Qigong spans over 4,000 years, and the term was officially recognized in China in the 1950s (12). Qigong includes various styles such as Baduanjin, Wuqinxi, Liuzijue, and Yijinjing. It is simple to learn, does not require special equipment, and is well-suited for older adults. According to recent epidemiological studies, the number of Qigong practitioners in the United States has increased steadily over the past two decades (13). Compared to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I), which requires specialist delivery and neuromodulation techniques, which demand equipment and expertise (14), Qigong offers a low-cost, accessible, and culturally accepted intervention suitable for large-scale application among older populations (15, 16).

Qigong has been shown to enhance both cognitive and physical function in older adults (17), and is also recommended for managing sleep-fatigue symptom clusters in individuals with cancer (18). Meta-analyses have demonstrated its effectiveness in improving physical and psychological health outcomes, quality of life, depressive symptoms, and self-efficacy among older adults (16, 19). While prior meta-analyses found that Baduanjin may be a useful complementary therapy for older adults with insomnia (20), few have systematically evaluated Qigong as a standalone intervention. Specifically, no meta-analysis to date has compared the differential effects of qigong styles (e.g., Baduanjin vs. Wuqinxi) on sleep outcomes in this population. Moreover, previous reviews predominantly included English-language trials. This review incorporates a broader body of Chinese-language evidence, offering a culturally contextualized analysis of Qigong's role in sleep enhancement among older adults. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) aims to evaluate the effects of Qigong on sleep quality in older adults. By addressing this knowledge gap, we aim to provide evidence-based recommendations for clinicians and contribute to the development of safe, accessible, and culturally appropriate strategies to enhance sleep health in aging populations.

2 Methods

2.1 Study protocol

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (21) and registered with PROSPERO (Registration ID: CRD42024621360), an international prospective registry for systematic reviews. PRISMA checklist was provided in Supplementary materials 1.2.

2.2 Criteria for inclusion

The inclusion criteria were formulated in accordance with the PICOS principle.

2.2.1 Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCT).

2.2.2 Types of participants

Participants must be older adults with a minimum age of 60 years. We excluded stroke, unstable angina, compensatory heart failure, Parkinson's, severe mental illness, inability to cooperate, and other severe acute and chronic diseases.

2.2.3 Types of interventions

The interventions of our systematic review adopted Qigong exercise as the main intervention method (no limitation to the style)

2.2.4 Types of comparators

The control group received usual care, normal life, health education or other low-intensity exercise.

2.2.5 Types of outcome measures

The main outcome measure was total scores of subjective measures of sleep outcomes at the end point of the intervention. Sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication and daytime function was also analyzed in this review.

2.3 Search strategy

Electronic database searches were conducted using Boolean logic operators (“AND”, “OR”) to combine search terms. A representative example of the search strategy is as follows: (Qigong OR Baduanjin OR Wuqinxi) AND (sleep OR insomnia) AND (aged OR Senior OR Older adult). Seven databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, CNKI, VIP, and Wanfang were selected. Articles should be published until October 8th, 2025. We excluded conference abstracts, conference papers, personal communications, and ongoing trials. A detailed search strategy was shown in Supplementary Table 1.

2.4 Study selection

All identified studies were imported into EndNote 20. After excluding duplicate studies, two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts to select studies that met the inclusion criteria. The full-text versions of the eligible studies were then assessed by the same two reviewers using predefined exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer. Data from all included studies were extracted into a pre-designed Excel sheet.

2.5 Data extraction

According to the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook, study details were extracted independently by two reviewers as follows: First Author, Year of publication, Country of origin, Sample size (experimental/control groups), Mean age of participants, Proportion of female participants (%), Participants' health status, Intervention measures (experimental/control groups), Intervention doses (in minutes), Intervention frequency/duration, Primary outcomes, Movement standardization and Adherence monitoring. If a study reported outcomes at several time points, we used the longest follow-up.

2.6 Methodological quality assessment

We used the Cochrane revised tool to assess the risk of bias in randomized trials to evaluate the methodological quality of RCTs (22). Two independent reviewers rated the quality of the RCTs in the following domains: the randomization method, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. Within each domain, one or more signaling questions had one of five response options: yes, possibly yes, possibly no, no, and no information. These answers lead to the judgments of “high risk of bias,” “low risk of bias,” or “some concerns.” Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

2.7 Data analysis

We performed statistical analyses using Review Manager software 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and R version 4.2.0 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Since the included studies used the PSQI as the measurement tool, we used the weighted mean difference (WMD) to assess the effect of the intervention. We applied a random-effects model for the pooled analysis to account for potential confounding factors in the included studies. We reported all effect sizes with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We used forest plots to present the study results and assess heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. The magnitude of heterogeneity was interpreted based on guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration (23): 0%−40%: May not be clinically significant; 30%−60%: May indicate moderate heterogeneity; 50%−90%: May represent substantial heterogeneity; 75%−100%: Implies considerable heterogeneity. When substantial or considerable heterogeneity was detected (I2 > 50%), subgroup analyses were conducted to explore the influence of study characteristics, such as qigong style and participants' health status. Additionally, meta-regression was performed to identify potential sources of heterogeneity, with intervention doses, percentage of female participants, and cumulative practice dose (i.e., practice frequency × duration per session) serving as effect moderators. Subsequently, sensitivity analyses were carried out to evaluate the stability of pooled estimates and determine whether any individual study exerted undue influence on the overall effect size (24). Furthermore, publication bias was assessed via funnel plot visualization and Egger's test.

2.8 Certainty of evidence

We categorize the certainty of evidence for all reported outcomes as high, moderate, low, or very low using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach (25). GRADE evaluated the certainty of evidence for each outcome by considering five potential downgrading factors: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. The default quality of evidence for Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) is high. After applying any necessary downgrades based on these factors, we determined the final quality grade for the evidence of each outcome. We rated down imprecision if trials were <400 patients for continuous outcomes (25).

3 Results

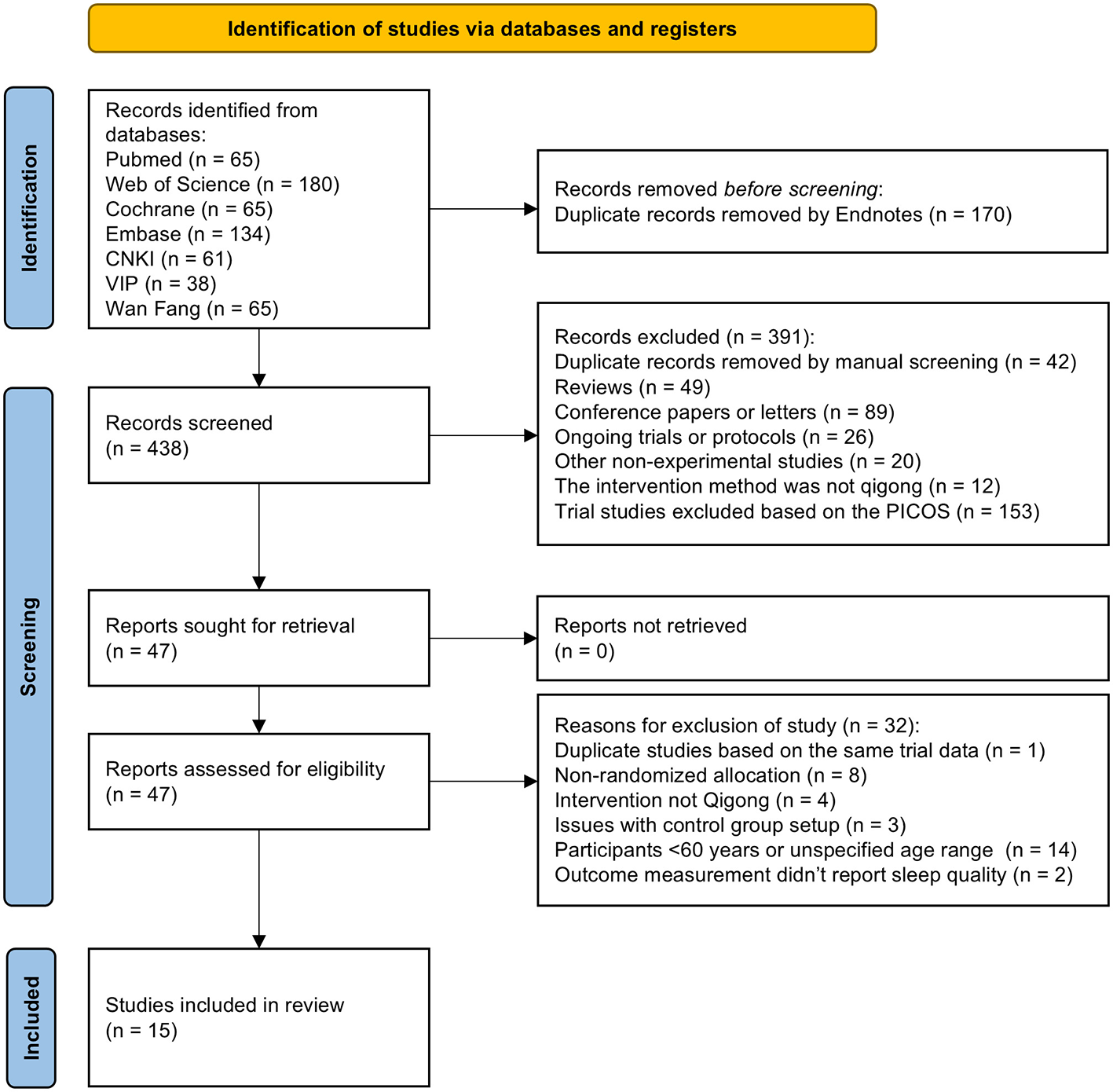

3.1 Literature search

We retrieved a total of 608 records. After removing duplicates and excluding records that did not meet the eligibility criteria, we included 15 studies in the review. The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the study selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2 Study characteristics

Of the 15 eligible trials (26–40), 14 were conducted in China (26–40), and 1 in Thailand (29). Five studies were published in English (26, 28, 29, 32, 37), while the remaining 10 were in Chinese (27, 30, 31, 33–36, 38–40). Sample sizes ranged from 22 to 72 participants per group, and all studies targeted adults aged 60 years or older. The proportion of female participants varied widely, ranging from 0% to 100%. The studies addressed various health conditions, with three focusing on older adults with sleep disturbances (28, 35, 38), two on depression (29, 40), four on hypertension (30, 31, 33, 36), one on chronic physical illness (32), and one on dementia-related fear (39). Regarding the style of Qigong, most studies used Baduajin (26–28, 30–33, 35, 36, 38, 40), while three studies used Wuqinxi (34, 37, 39). One study did not specify the Qigong style and was therefore not classified (29). Participants in the control group received usual care (26, 28, 30, 34, 36, 37), education (27), medication (31, 33, 40), massage (35, 38), other form of exercise (29) or psychological interventions (32, 39). The frequency and duration of the interventions varied, ranging from 25 to 60 min per day, 2–7 times per week, and lasting from 2 to 26 weeks. Details of the included studies are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

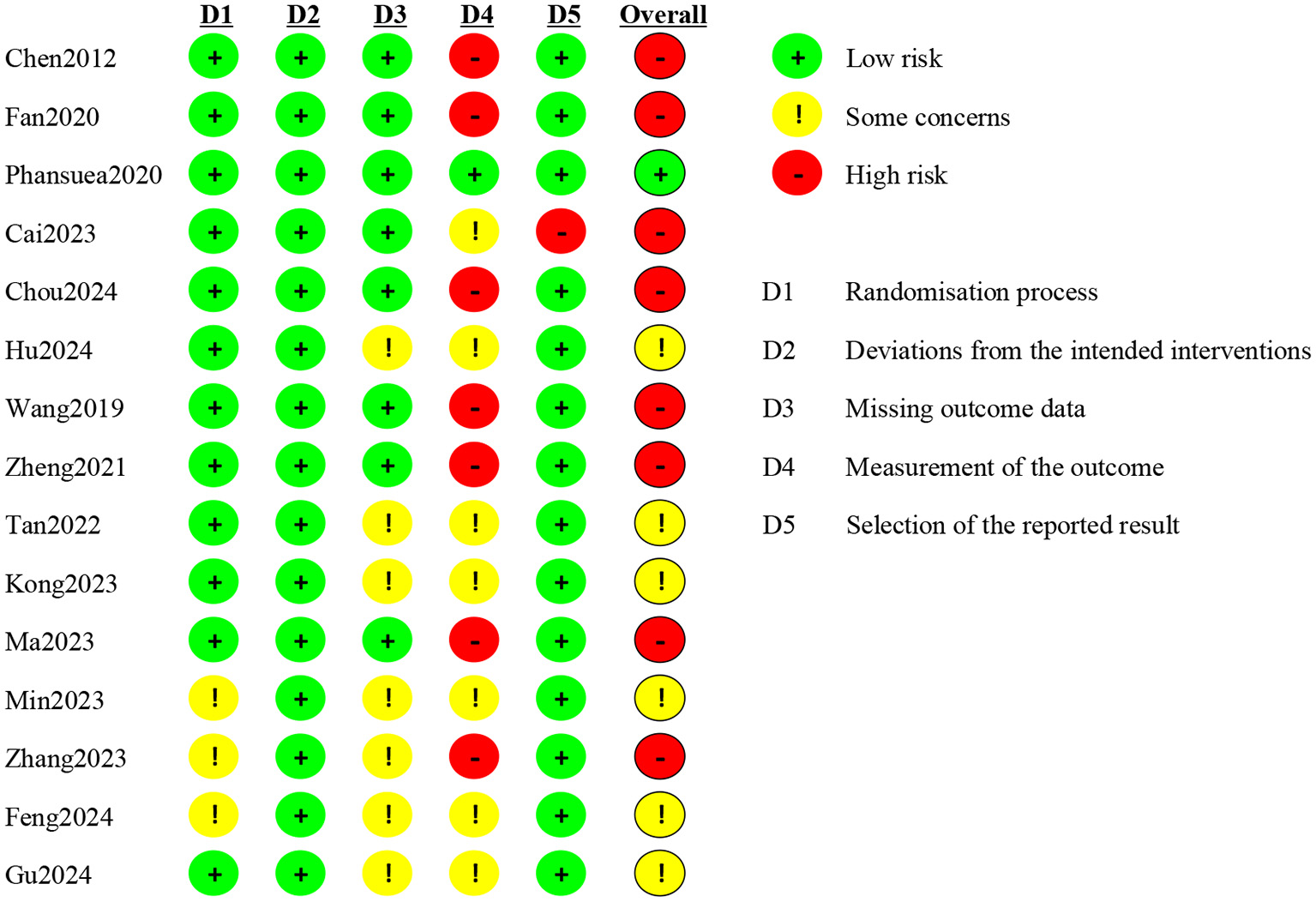

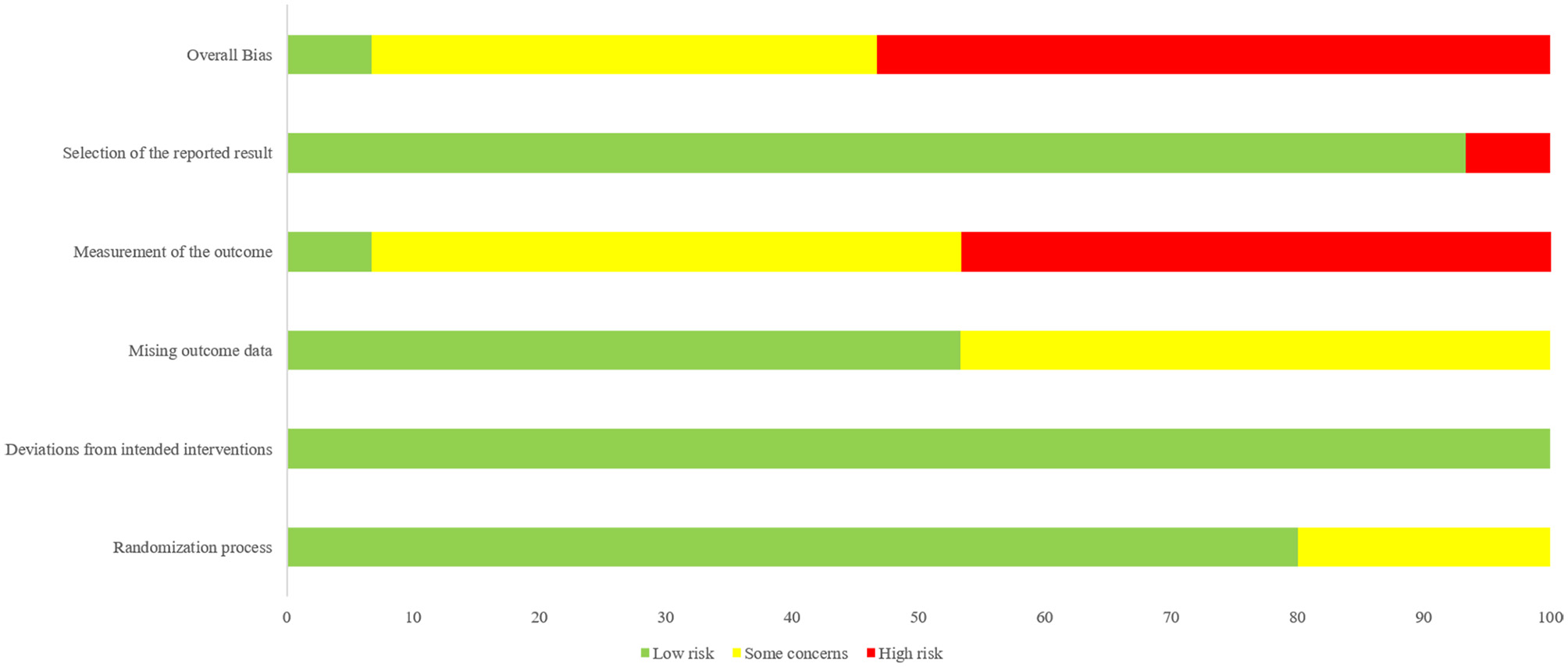

3.3 Quality assessment

Of the 15 eligible trials, 14 (93.3%) exhibited a risk of bias in at least one domain (26–28, 30–40). Three studies (20%) did not describe their random sequence generation (35, 36, 38), and none reported deviations from the intended interventions. Seven studies (46.7%) did not mention dropouts (31, 33, 35, 36, 38–40). Only one study included an active control group (29), while seven (46.7%) used passive controls, potentially introducing non-specific factors. One study failed to report the total Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score due to an error in the “habitual sleep efficiency” subitem, which may have compromised score reliability (32). Overall, 1 study was rated as having “low risk of bias,” 6 as having “some concerns,” and 8 as having “high risk of bias.” The risk of bias in individual trials was shown in Figure 2. The risk of bias in included studies was demonstrated in Figure 3.

Figure 2

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. (“+”, low risk; “–”, high risk; “!”, some concerns.)

Figure 3

Overall risk of bias: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.4 Meta-analysis results

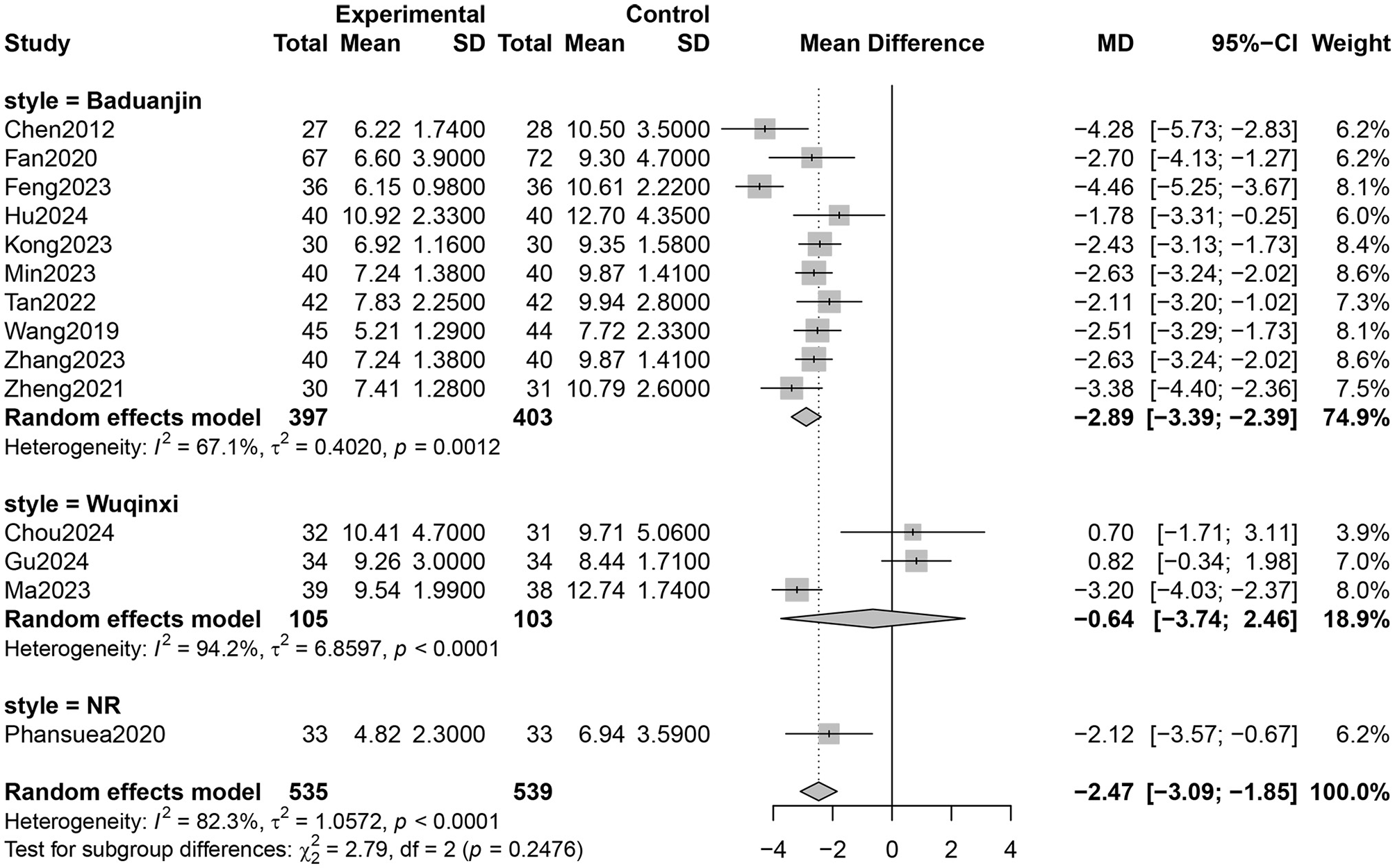

3.4.1 PSQI total scores

Fourteen RCTs involving 1,027 participants reported PSQI total scores (26–31, 33–40). The certainty of evidence evaluated by GRADE was shown in Supplementary Table 2. Low certainty of evidence showed that Qigong probably improved the sleep quality of older adults compared with control groups (MD = −2.47, 95% CI [−3.09, −1.85], p < 0.001; Figure 4). However, high heterogeneity (I2 = 82.3%, p < 0.001) was observed. Subgroup analysis showed that the style of Qigong had different effects on sleep quality. Baduanjin intervention improved sleep quality (MD = −2.89, 95% CI [−3.39, −2.39], p < 0.001) and was associated with high heterogeneity (I2 = 67.1%, p = 0.001), while Wuqinxi did not show a significant improvement in sleep quality (MD = −0.64, 95% CI [−3.74, 2.46], p = 0.68) and also had high heterogeneity (I2 = 94.2%, p < 0.001) (Figure 5). Additionally, subgroup analysis based on participants' disease conditions showed that Qigong significantly improved sleep quality in older adults with sleep disturbances (MD = −3.30, 95% CI [−4.62, −1.98], p < 0.001), depression (MD = −1.96, 95% CI [−3.01, −0.90], p = 0.0003), and hypertension (MD = −2.61, 95% CI [−3.02, −2.20], p < 0.001). The effect on participants with sleep disturbances was associated with high heterogeneity (I2 = 85.1%, p = 0.001), whereas the depression group (I2 = 0.0%, p = 0.752) and hypertension group (I2 = 7.6%, p = 0.355) showed low heterogeneity (Figure 6). Meta-regression showed that proportion of female, mean ages and total intervention time were not significantly associated with the effect size (Table 1). Sensitivity test demonstrated good robustness (Figure 7). Funnel plot (Supplementary Figure 1) and Egger's test (t = 1.09, p = 0.295) indicated no potential risk of publication bias.

Figure 4

![Forest plot displaying mean differences between experimental and control groups across 14 studies from 2012 to 2024. Each study is represented by a square with a horizontal line indicating the confidence interval. The pooled mean difference is -2.47 with a 95% confidence interval of [-3.09, -1.85], shown as a diamond. Heterogeneity is at 82.3% with significance p < 0.0001.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1664055/xml-images/fpubh-13-1664055-g0004.webp)

Effect of Qigong on PSQI total scores.

Figure 5

Subgroup analysis according to style of Qigong on sleep quality (NR, not reported).

Figure 6

![Forest plot showing meta-analysis of different diseases: NR, sleep disorders, depression, and hypertension. Each section displays multiple studies with mean differences (MD), confidence intervals (CI), and weights. Random effects model is applied, indicating heterogeneity for each disease. The overall mean difference across all studies is -2.47 with a confidence interval of [-3.09; -1.85].](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1664055/xml-images/fpubh-13-1664055-g0006.webp)

Subgroup analysis according to health status of older adults on sleep quality (NR, not reported).

Table 1

| Parameters | Coefficient | t | p | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female% | 0.05 | 0.97 | 0.38 | −0.08, 0.17 |

| Age | −0.38 | −1 | 0.36 | −1.35, 0.59 |

| Doses | −0.00003 | −0.01 | 0.92 | −0.0008, 0.0007 |

Results of meta regression.

CI, confidence interval.

Figure 7

![Forest plot displaying the effect sizes and confidence intervals for a series of studies. Each row represents a study, indicating the mean difference (MD), 95% confidence interval (CI), p-value, Tau2, Tau, and I2. The central column shows individual study estimates and their confidence intervals as horizontal lines intersected by squares. A diamond shape at the bottom represents the pooled random effects model estimate, with a mean difference of -2.47 and a 95% CI of [-3.09; -1.85], with a p-value less than 0.0001, suggesting a significant overall effect.](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1664055/xml-images/fpubh-13-1664055-g0007.webp)

Sensitivity test.

3.4.2 PSQI sub-item scores

Qigong probably contributed to positive effect on subjective sleep quality (MD = −0.58, 95% CI [−0.76, −0.40], p < 0.001, 6 studies, Table 2), sleep latency (MD = −0.53, 95% CI [−0.71, −0.36], p < 0.001, 6 studies), sleep duration (MD = −0.44, 95% CI [−0.65, −0.24], p < 0.001, 6 studies), sleep efficiency (MD = −0.53, 95% CI [−0.79, −0.27], p < 0.001, 5 studies), sleep disturbance (MD = −0.24, 95% CI [−0.32, −0.16], p < 0.001, 6 studies), daytime dysfunction (MD = −0.37, 95% CI [−0.46, 0.28], p < 0.001, 6 studies), use of hypnotics (MD = −0.12, 95% CI [−0.18, −0.06], p = 0.002, 6 studies). All of the outcomes of sub-items were categorized to moderate certainty of evidence except for sleep efficiency (low) (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2

| Outcomes | No of trials | MD | 95%CI | I 2 (%) | Z-test for overall effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective sleep quality | 6 (401) | −0.58 | −0.76, −0.40 | 57 | p < 0.001 |

| Sleep latency | 6 (401) | −0.53 | −0.71, −0.36 | 47 | p < 0.001 |

| Sleep duration | 6 (403) | −0.44 | −0.65, −0.24 | 68 | p < 0.001 |

| Sleep efficiency | 5 (356) | −0.53 | −0.79, −0.27 | 80 | p < 0.001 |

| Sleep disturbance | 6 (400) | −0.24 | −0.32, −0.16 | 16 | p < 0.001 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 6 (401) | −0.37 | −0.46, −0.28 | 77 | p < 0.001 |

| Use of hypnotics | 6 (401) | −0.12 | −0.18, −0.06 | 22 | p = 0.002 |

Effect of qigong on sub-items of PSQI.

MD, mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

4 Discussion

This review systematically examined the effectiveness of Qigong in improving sleep quality among older adults. While the overall findings indicate a significant positive effect, the certainty of evidence remains low, primarily due to substantial heterogeneity and the risk of bias in the included studies. Among the Qigong styles, Baduanjin demonstrated the most consistent benefits, whereas Wuqinxi showed limited efficacy, possibly due to the small sample sizes and inconsistent intervention protocols.

Previous reviews have demonstrated the efficacy of Qigong in improving sleep quality across diverse populations. For instance, Qigong has been recommended for breast cancer survivors to enhance sleep quality (41). Additionally, Baduanjin was found to improve physical and mental wellbeing in patients with cardiovascular diseases (42), while traditional Chinese mind-body exercises positively affected sleep quality in individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome (43). Furthermore, our findings are consistent with a recent systematic review, which summarized evidence from randomized controlled trials on the effects of various exercise modalities on sleep quality in older adults, with a focus on older women adults. Their review highlighted that mind-body exercises, including Qigong and Baduanjin, were associated with improvements in sleep latency, efficiency, and overall PSQI scores. While their analysis emphasized older women as a high-risk group, our results extend support for the potential benefits of Qigong in improving sleep quality among the broader older adult population (10). Wu found that both traditional Chinese exercises and general aerobic exercises improved sleep quality in aging people with sleep disturbances [Yang-hao-tian (44)]. Liang found that Baduanjin probably reduced PSQI total and dimension scores, thus improving sleep quality in older adults (20). Furthermore, Ko found that percentage of women and age were significantly associated with the effect size of Qigong on sleep quality (45), while Wu found no relationship, which was in line with current study. Overall, the results of our study were similar to previous meta-analysis, suggesting that qigong may improve sleep quality in the older adults.

Aging is associated with reduced melatonin secretion and disrupted circadian rhythms (46). Insufficient daytime physical activity and a lack of regular exercise were significant contributors to poor sleep quality (47), which may explain why Qigong increased sleep quality in older adults. Moreover, Qigong practice enhances parasympathetic activity and suppresses sympathetic activity through controlled breathing and heart rate regulation (48). This autonomic balance promotes quicker sleep onset and fewer nighttime awakenings, benefiting older adults with hypertension. Older adults are more likely to experience anxiety and depression, which can significantly disrupt sleep (49). Poor sleep, consequently, worsens emotional distress by increasing stress and reducing emotional stability, creating a vicious cycle between sleep problems and mental health issues (50, 51). Qigong helps break this cycle by improving emotional wellbeing and promoting calmness (52), fostering a sense of mindfulness and self-awareness, which enhances resilience to stress and promotes mental wellbeing (53). Furthermore, according to traditional Chinese medicine, Qigong promotes health by regulating the flow of ‘qi' (vital energy) in the body (12). It combines slow movements and controlled breathing to improve circulation, support organ function, and activate the body's natural healing processes. These effects enhance both physical and mental wellbeing (54, 55). When considering Qigong alongside other non-drug sleep treatments, it offers clear practical benefits. Unlike cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia which requires trained therapists (56), or neuromodulation techniques needing special machines, Qigong doesn't need special equipment or places to practice. Its movements are easy to learn at home or in groups (57). In East Asian communities, people are familiar with this practice (58). Compared to exercises like running or aerobics which might be too hard for frail older adults (59), Baduanjin's gentle movements are safer while still helping relaxation through breathing control (60). This makes it a useful option for older people who need low-risk activities (61).

Despite observing positive effects of Qigong, significant heterogeneity was detected across studies. While subgroup analyses and meta-regression failed to identify significant sources of overall heterogeneity, several unmeasured but methodologically and practically relevant factors may still explain the observed variability. First, methodological flaws across studies introduced inherent variability independent of Qigong itself. As noted in the Methods section, 3 of the 15 included RCTs did not report random sequence generation methods, raising concerns about baseline imbalance between intervention and control groups; 7 studies failed to disclose dropout data. Both issues may overestimate intervention efficacy. More critically, only 1 study used an active control (low-intensity aerobic exercise). This lack of active controls means the observed sleep improvements may partially reflect placebo effects rather than the true therapeutic effect of Qigong, thereby amplifying between-study heterogeneity. Second, inconsistencies in Qigong intervention delivery—particularly in movement standardization and adherence monitoring—further contributed to outcome variability. In terms of movement standardization, some relied on full-time guidance from certificated instructors, others used self-guided learning via videos with no verification of movement accuracy; and a few adopted mixed methods. This variability directly affects intervention fidelity. Adherence monitoring methods also varied widely. Different supervision intensities likely influenced participants' adherence to standardized movements—weaker monitoring (or no monitoring) may lead to inconsistent practice quality, while frequent telephone check-ins could prompt more rigorous adherence—ultimately introducing variability in reported effect sizes. Third, protocol inconsistencies within specific Qigong styles exacerbated subgroup heterogeneity, particularly for Wuqinxi. As documented in previous research (62), variations in core practice parameters—including movement speed (e.g., slow, controlled motions vs. rushed execution), range of motion (e.g., full arm extension vs. partial movement), and animal-mimetic technique details (e.g., the degree of “ape-like” agility in Wuqinxi's ape part)—can significantly alter the intervention's intensity and physiological impact. In our sample, the 3 Wuqinxi studies lacked detailed description in these parameters. Such fundamental protocol differences likely explain the subgroup's extremely high heterogeneity (I2 = 94.2%) and non-significant sleep benefits, as the intervention's intended therapeutic components were not uniformly delivered.

Our study offers distinct strengths that enhance its contribution to the field. Given Qigong's cultural roots in China, we comprehensively searched three Chinese databases (CNKI, VIP, Wanfang) to capture evidence often overlooked in English-dominant reviews. We further strengthened methodological rigor by exclusively including randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and employing the GRADE framework to evaluate evidence quality. Finally, our analysis of all Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) subcomponents demonstrates Qigong's broad, positive impact across multiple dimensions of sleep quality in older adults. However, there are limitations to our research. High heterogeneity across studies may be due to differences in Qigong styles, participant health status, and designs of interventions. Most of the included studies were conducted in China, which could introduce cultural or educational biases. Additionally, most of studies fail to set active control. The lack of exercise control groups in many studies makes it difficult to rule out non-specific factors. Many studies did not report long-term follow-up data, which undermines the overall reliability of the findings. Notably, to address these limitations and reduce the variability of results, future research should prioritize conducting high-quality randomized controlled trials with standardized protocols—such as unified specifications for Qigong movements and rigorous adherence monitoring.

5 Conclusions

Qigong, particularly Baduanjin, may effectively improve sleep quality in older adults. Nevertheless, given the methodological limitations and heterogeneity of the included studies, further high-quality research is needed to validate these findings and inform clinical practice.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

XX: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. EZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who participated in this study.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1664055/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Foley DJ Monjan AA Brown SL Simonsick EM Wallace RB Blazer DG et al . Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. (1995) 18:425–32. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.6.425

2.

Crowley K . Sleep and sleep disorders in older adults. Neuropsychol Rev. (2011) 21:41–53. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6

3.

Cheong E-N Rhee Y Kim CO Kim HC Hong N Shin Y-W et al . Alterations in the global brain network in older adults with poor sleep quality: a resting-state fMRI study. J Psychiatr Res. (2023) 168:100–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2023.10.037

4.

Smagula SF Stone KL Fabio A Cauley JA . Risk factors for sleep disturbances in older adults: Evidence from prospective studies. Sleep Med Rev. (2016) 25:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.01.003

5.

Ancoli-Israel S . Sleep and its disorders in aging populations. Sleep Med. (2009) 10:S7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.004

6.

Mander BA Winer JR Walker MP . Sleep and Human Aging. Neuron. (2017) 94:19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.004

7.

Wang L Pan Y Ye C Guo L Luo S Dai S et al . A network meta-analysis of the long- and short-term efficacy of sleep medicines in adults and older adults. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2021) 131:489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.09.035

8.

Schroeck JL Ford J Conway EL Kurtzhalts KE Gee ME Vollmer KA et al . Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther. (2016) 38:2340–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2016.09.010

9.

Hasan F Tu Y-K Lin C-M Chuang L-P Jeng C Yuliana LT et al . Comparative efficacy of exercise regimens on sleep quality in older adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. (2022) 65:101673. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101673

10.

Khaleghi MM Ahmadi F . Effect of different exercises on sleep quality in elderly women: a systematic review. Comp Exercise Physiol. (2024) 20:219–30. doi: 10.1163/17552559-00001049

11.

Feng F Tuchman S Denninger JW Fricchione GL Yeung A . Qigong for the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of COVID-19 infection in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:812–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.012

12.

Jahnke R Larkey L Rogers C Etnier J Lin F . A comprehensive review of health benefits of qigong and tai chi. Am J Health Promot. (2010) 24:e1–e25. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.081013-LIT-248

13.

Wang CC Li K Choudhury A Gaylord S . Trends in Yoga, Tai Chi, and qigong use among US adults, 2002–2017. Am J Public Health. (2019) 109:755–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.304998

14.

Yu DJ Yu AP Li SX Chan RNY Fong DY Chan DKC et al . Effects of Tai Chi and cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on improving sleep in older adults: Study protocol for a non-inferiority trial. J Exerc Sci Fit. (2023) 21:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2022.10.012

15.

Chang P-S Knobf MT Funk M Oh B . Feasibility and acceptability of qigong exercise in community-dwelling older adults in the United States. J Altern Complement Med. (2018) 24:48–54. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0096

16.

Chang P-S Knobf T Oh B Funk M . Physical and psychological health outcomes of qigong exercise in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Chin Med. (2019) 47:301–22. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X19500149

17.

Park M Song R Ju K Shin JC Seo J Fan X et al . Effects of Tai Chi and Qigong on cognitive and physical functions in older adults: systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. BMC Geriatr. (2023) 23:352. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04070-2

18.

Cheung DST Takemura N Smith R Yeung WF Xu X Ng AYM et al . Effect of qigong for sleep disturbance-related symptom clusters in cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. (2021) 85:108–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.036

19.

Gouw VXH Jiang Y Seah B He H Hong J Wang W et al . Effectiveness of internal Qigong on quality of life, depressive symptoms and self-efficacy among community-dwelling older adults with chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. (2019) 99:103378. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.06.009

20.

Liang Q Yang L Wen Z Liang X Wang H Zhang H et al . The effect of Baduanjin on the insomnia of older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Geriatr Nurs. (2024) 60:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2024.09.002

21.

Page MJ McKenzie JE Bossuyt PM Boutron I Hoffmann TC Mulrow CD et al . The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

22.

Flemyng E Dwan K Moore TH Page MJ Higgins JP . Risk of bias 2 in cochrane reviews: a phased approach for the introduction of new methodology. Cochr Database Syst Rev. (2020) 10:ED000148. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000148

23.

Higgins JPT Thompson SG Deeks JJ Altman DG . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

24.

Veroniki AA Jackson D Viechtbauer W Bender R Bowden J Knapp G et al . Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. (2016) 7:55–79. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1164

25.

Guyatt GH Oxman AD Schünemann HJ Tugwell P Knottnerus A . GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:380–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011

26.

Chen M-C Liu H-E Huang H-Y Chiou A-F . The effect of a simple traditional exercise programme (Baduanjin exercise) on sleep quality of older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. (2012) 49:265–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.009

27.

Wang XD Li XD Bi XJ . The effect of Ba Duan Jin fitness qigong on sleep quality and memory function in community-dwelling elderly people. Chin J Gerontol. (2019) 3435–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2019.14.029

28.

Fan B Song W Zhang J Er Y Xie B Zhang H et al . The efficacy of mind-body (Baduanjin) exercise on self-reported sleep quality and quality of life in elderly subjects with sleep disturbances: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath. (2020) 24:695–701. doi: 10.1007/s11325-019-01999-w

29.

Phansuea P Tangwongchai S Rattananupong T Lohsoonthorn V Lertmaharit S . Effectiveness of a Qigong program on sleep quality among community-dwelling older adults with mild to moderate depression A randomized controlled trial. J Health Res. (2020) 34:305–15. doi: 10.1108/JHR-04-2019-0091

30.

Zheng LW Liu WH Zou LY Fan WY Chen F . Effects of Baduanjin on sleep quality in elderly patients with essential hypertension and insomnia. J Guangxi Univ Chin Med. (2021) 24:33–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-4441.2021.04.010

31.

Tan LH Jiang P Ye L . Clinical study on eight-section brocade in adjuvant treatment of essential hypertension complicated with insomnia in senile patients. New Chin Med. (2022) 54:175–8. doi: 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2022.16.038

32.

Cai S Tsang HWH Lu EY Leung MKW Siu DCH Leung SY et al . Enhancing subjective wellbeing through Qigong: a randomized controlled trial in older adults in hong kong with chronic physical illness. Altern Ther Health Med. (2023) 29:12–9.

33.

Kong XZ Gao F Ji BB Su YP . Effect of amlodipine besylate tablets combined with Baduanjin in the treatment of elderly male patients with hypertension. J Doctors Online. (2023) 13:44–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-7165.2023.10.012

34.

Ma CX Fan H Zhou HL Dong L Zhou Y . Effects of the monkey exercise in Wuqinxi on anxiety, depression and quality of sleep in patients with mild cognitive impairment. J Modern Med Health. (2023) 32:3986–90. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-5519.2023.23.006

35.

Min CH Li YF Zhuang J . Effect of Baduanjin combined with plantar acupoint massage in the treatment of community elderly patients with insomnia. Jilin Medical Journal. (2023) 44:1131–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-0412.2023.04.077

36.

Zhang YJ . Effects of Baduanjin exercise on blood pressure control, psychological state and sleep quality in elderly patients with hypertension. Chin Sci Technol J Database Med. (2023) 23:1–4.

37.

Chou TW Kuo CC Chen KM Belcastro F . Influence of qigong wuqinxi on pain, sleep, and tongue features in older adults. J Nurs Res. (2024) 32:e358. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0000000000000646

38.

Feng Q . Effect of Baduanjin combined with plantar acupoint massage on senile insomnia. Care Health. (2024) 32:80–2.

39.

Gu YF Chen Y Yu J Shi YN Gao NN Cheng J et al . Effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy combined with Wuqinxi training on the elderly with dementia fear in nursing homes. Chin General Pract Nurs. (2024) 22:327–30. doi: 10.12104/j.issn.1674-4748.2024.02.029

40.

Hu YR Xu YG . Study on the Therapeutic effect of baduanjin exercise therapy combined with duloxetine on elderly female patients with depression. Adv Clin Med. (2024) 14:1132–7. doi: 10.12677/acm.2024.1472123

41.

Chuang C-W Tsai M-Y Wu S-C Liao W-C . Chinese medicines treatment for sleep disturbance in breast cancer survivors: a network meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther. (2024) 23:15347354241308857. doi: 10.1177/15347354241308857

42.

Chen J Zhang M Wang Y Zhang Z Gao S Zhang Y et al . The effect of Ba Duan Jin exercise intervention on cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Public Health. (2024) 12:1425843. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1425843

43.

Kong L Ren J Fang S Li Y Wu Z Zhou X et al . Effects of traditional Chinese mind-body exercises for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. (2023) 13:04157. doi: 10.7189/jogh.13.04157

44.

Wu Y-h-t He W-b Gao Y-y Han X-m . Effects of traditional Chinese exercises and general aerobic exercises on older adults with sleep disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Integr Med. (2021) 19:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.joim.2021.09.007

45.

Ko L-H Hsieh Y-J Wang M-Y Hou W-H Tsai P-S . Effects of health qigong on sleep quality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. (2022) 71:102876. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2022.102876

46.

Castro-Pascual IC Ferramola ML Altamirano FG Cargnelutti E Devia CM Delgado SM et al . Circadian organization of clock factors, antioxidant defenses, and cognitive genes expression, is lost in the cerebellum of aged rats. Possible targets of therapeutic strategies for the treatment of age-related cerebellar disorders. Brain Res. (2024) 1845:149195. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2024.149195

47.

King AC Pruitt LA Woo S Castro CM Ahn DK Vitiello MV et al . Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on polysomnographic and subjective sleep quality in older adults with mild to moderate sleep complaints. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2008) 63:997–1004. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.997

48.

Wang X Xiong H Du S Yang Q Hu L . The effect and mechanism of traditional Chinese exercise for chronic low back pain in middle-aged and elderly patients: a systematic review. Front Aging Neurosci. (2022) 14:935925. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.935925

49.

Zhang C Xiao S Lin H Shi L Zheng X Xue Y et al . The association between sleep quality and psychological distress among older Chinese adults: a moderated mediation model. BMC Geriatr. (2022) 22:35. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02711-y

50.

Baglioni C Battagliese G Feige B Spiegelhalder K Nissen C Voderholzer U et al . Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. (2011) 135:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011

51.

Krystal AD . Psychiatric disorders and sleep. Neurol Clin. (2012) 30:1389–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.08.018

52.

Wang F Man JKM Lee E-KO Wu T Benson H Fricchione G . L, et al. The effects of qigong on anxiety, depression, and psychological wellbeing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2013) 2013:152738. doi: 10.1155/2013/152738

53.

Tsang HWH Fung KMT Chan ASM Lee G Chan F . Effect of a qigong exercise programme on elderly with depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2006) 21:890–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.1582

54.

Li R Jin L Hong P He Z-H Huang C-Y Zhao J-X et al . The effect of baduanjin on promoting the physical fitness and health of adults. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2014) 2014:784059. doi: 10.1155/2014/784059

55.

van Dam K . Individual stress prevention through Qigong. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:7342. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197342

56.

Rossman J . Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: an effective and underutilized treatment for insomnia. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2019) 13:544–7. doi: 10.1177/1559827619867677

57.

Neuendorf R Wahbeh H Chamine I Yu J Hutchison K Oken BS et al . The effects of mind-body interventions on sleep quality: a systematic review. Evid-based Complement Altern Med. (2015) 2015:902708. doi: 10.1155/2015/902708

58.

Cheung DST Chau PH Yeung W-F Deng W Hong AWL Tiwari AFY et al . Assessing the effect of a mind-body exercise, qigong baduanjin, on sleep disturbance among women experiencing intimate partner violence and possible mediating factors: a randomized-controlled trial. J Clin Sleep Med. (2021) 17:993–1003. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9102

59.

Trampisch US Petrovic A Daubert D Wirth R . Fall prevention by reactive balance training on a perturbation treadmill: is it feasible for prefrail and frail geriatric patients? A pilot study. Eur Geriatr Med. (2023) 14:1021–6. doi: 10.1007/s41999-023-00807-9

60.

Liu X Seah JWT Pang BWJ Tsao MA Gu F Ng WC et al . A single-arm feasibility study of community-delivered Baduanjin (Qigong practice of the eight Brocades) training for frail older adults. Pilot Feasibility Stud. (2020) 6:105. doi: 10.1186/s40814-020-00649-3

61.

Fang J Zhang L Wu F Ye J Cai S Lian X et al . The safety of baduanjin exercise: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. (2021) 2021:8867098. doi: 10.1155/2021/8867098

62.

Guo Y Xu M Wei Z Hu Q Chen Y Yan J et al . Beneficial effects of Qigong Wuqinxi in the improvement of health condition, prevention, and treatment of chronic diseases: evidence from a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2018) 2018:3235950. doi: 10.1155/2018/3235950

Summary

Keywords

Qigong, exercise, sleep quality, older adults, systematic review, meta-analysis

Citation

Xiong X, Zhang L and Zhang E (2025) The effects of Qigong exercise on sleep quality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Public Health 13:1664055. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1664055

Received

15 July 2025

Revised

22 October 2025

Accepted

30 November 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Xiaosheng Dong, Shandong University, China

Reviewed by

Mohammad Mehdi Khaleghi, Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran

Yuanpeng Liao, Chengdu Sport University, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xiong, Zhang and Zhang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Enming Zhang, zhangenming@bsu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.