- 1School of Physical Education, Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China

- 2Minnan Science and Technology College, Nanchang, China

- 3Jiangxi Normal University, Nanchang, China

- 4Department of Psychological Science, University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley, Edinburg, TX, United States

- 5Chongqing City Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chongqing, China

Introduction: Although physical activity benefits youth development, little is known about how it is related to prosocial behavior over time, especially among structurally disadvantaged groups such as rural left-behind children in China. This longitudinal study examined the bidirectional relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior and the mediating role of psychological resilience.

Methods: A total of 612 children (Grades 5–6; approximately 10–12 years old; 50.5% male) from three schools in Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province, completed measures of physical activity, psychological resilience, and prosocial behavior at three time points over 6 months.

Results: Crosslagged mediation structural equation modeling revealed reciprocal pathways: Time 1 physical activity was related to Time 3 prosocial behavior, and vice versa. In both directions, psychological resilience at Time 2 significantly mediated these associations (indirect effects = 0.07 and 0.04, respectively; ps < 0.001). These findings underscore psychological resilience as a key developmental mechanism linking physical and social functioning.

Discussion: The results highlight the potential for integrated school-based interventions that promote physical activity to enhance psychological resilience and social functioning in vulnerable youth populations, particularly rural left-behind children.

Introduction

Urbanization represents one of the most significant global demographic trends, profoundly reshaping social, economic, and cultural structures worldwide (1). Particularly in China, rapid urbanization has driven unprecedented rural-to-urban migration, resulting in psychosocial challenges (2). Among these challenges is the rising number of rural left-behind children, those whose parents migrate to urban areas for employment opportunities, leaving children behind in rural settings (3). Official statistics indicate that there are approximately 69 million rural left-behind children in China (4) who are subjective to severe emotional distress, delays in psychological and social development, and impaired social adaptability partly due to prolonged parental absence and limited access to support (5). The economic cost associated with managing the consequences of parental migration, including educational support, mental health care, and social services, creates long-term socioeconomic burdens of the country (6). Given the global prevalence of migration and similar challenges in other regions (e.g., child migrants or sent-away children), researchers worldwide should prioritize the psychosocial health of these individuals. Specifically, it is critical to prospectively examine the associations between physical activity, considered as a potential intervention target, and psychosocial outcomes among rural left-behind children (7).

One critical psychosocial concern among rural left-behind children is their reduced display of prosocial behavior (8). Prosocial behavior refers to positive interactions beneficial to others and social harmony and is an essential indicator of mental health and social stability (9). With the severance of emotional ties, left-behind children often experience negative emotions such as stress, anxiety, sadness, depression, and self-isolation, leading to low levels of prosocial behavior and poor social adjustment (10). Neurological research revealed that parental absence significantly impacts brain regions associated with emotional and social functioning. For example, prolonged parental separation correlates with increased amygdala volume (11, 12), a brain structure essential for emotional processing and social interactions, potentially reducing prosocial behaviors. Additionally, adverse experiences disrupt neural synchrony in lateral prefrontal cortex, an area crucial for emotion regulation and social cognition (13). In the same vein, positive parent–child interactions play a critical role in developing neural circuits involved in empathy and prosocial behavior (14). A meta-analysis examining parenting behaviors found significant positive correlations between nurturing parenting practices (i.e., child–mother attachment security) and children’s prosocial behaviors (15).

Given these socio-emotional vulnerabilities, identifying accessible and developmentally appropriate strategies is critical to support prosocial development among rural left-behind children. One promising pathway may lie in the role of physical activity. On one hand, physical activity can promote prosocial behavior by fostering healthy self-perceptions and enhancing emotional intelligence (16–18). For example, a positive campus sports environment has been associated with higher levels of children’s subjective well-being through improved peer relationships and positive emotions (19). These experiences lay the foundation for the development of prosocial tendencies in children. Regular participation in physical activity has also been associated with increased activation in the prefrontal cortex, a region critical for social decision-making and emotional regulation (20, 21). A meta-analytical review among children and adolescent further shows that playing sports can improve their prosocial behaviors (22). Interestingly, emerging evidence suggests that this relationship may be bidirectional: children who display higher levels of prosocial behavior may also engage more frequently in physical activity, particularly in cooperative or socially interactive contexts (23). Such children with high prosocial behaviors may actively seek social participation opportunities that encourage involvement in group-based exercise or sports. Some studies among older adults also showed that incorporating prosocial behaviors can promote physical activity (24). However, due to the cross-sectional designs of most studies, the directionality and temporal dynamics of this association has not been established. Therefore, longitudinal evidence is needed to clarify the bidirectional associations between physical activity and prosocial behavior and to elucidate their underlying mechanisms.

Psychological resilience may serve as a mediating mechanism in both directions of the relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior. Resilience theory (25) posits that individuals with higher psychological resilience are better able to maintain adaptive functioning in the face of adversity, enhancing their capacity to recover from challenges and sustain positive social and health-related behaviors (26). On one hand, physical activity may be associated with greater psychological resilience, which in turn is linked to higher levels of prosocial behavior. Theoretically, physical activities can fulfill psychological needs such as competence, autonomy, and relatedness, which are foundational to building psychological resilience (27, 28). This is supported by empirical and meta-analytical review evidence (29), showing that physical activity is positively associated with psychological resilience among children and adolescents (30–32), by providing structured opportunities to overcome challenges, develop self-regulatory skills, and build coping strategies (33–35). Psychological resilience, in turn, has been identified as a predictor of prosocial behaviors by empirical research (36, 37), likely due to greater empathy and cooperative problem-solving (38). However, a small body of evidence also suggests that prosocial behavior may be associated with greater psychological resilience. For example, a quantitative study among single mothers found that prosocial behaviors predicted higher resilience by fostering a psychological sense of community and promoting positive personal outcomes (39). In the context of sports, resilience-enhancement programs have been implemented to improve athletes’ persistence and performance (40, 41), suggesting that resilience may serve as a predictor of sustained physical activity. However, a notable research gap persists concerning longitudinal studies explicitly investigating psychological resilience as a mediator in the potential bidirectional association between physical activity and prosocial behavior among rural left-behind children. This is particularly important because the development of effective interventions requires a clear understanding of not only the directionality of these relationships but also the underlying psychological mechanisms.

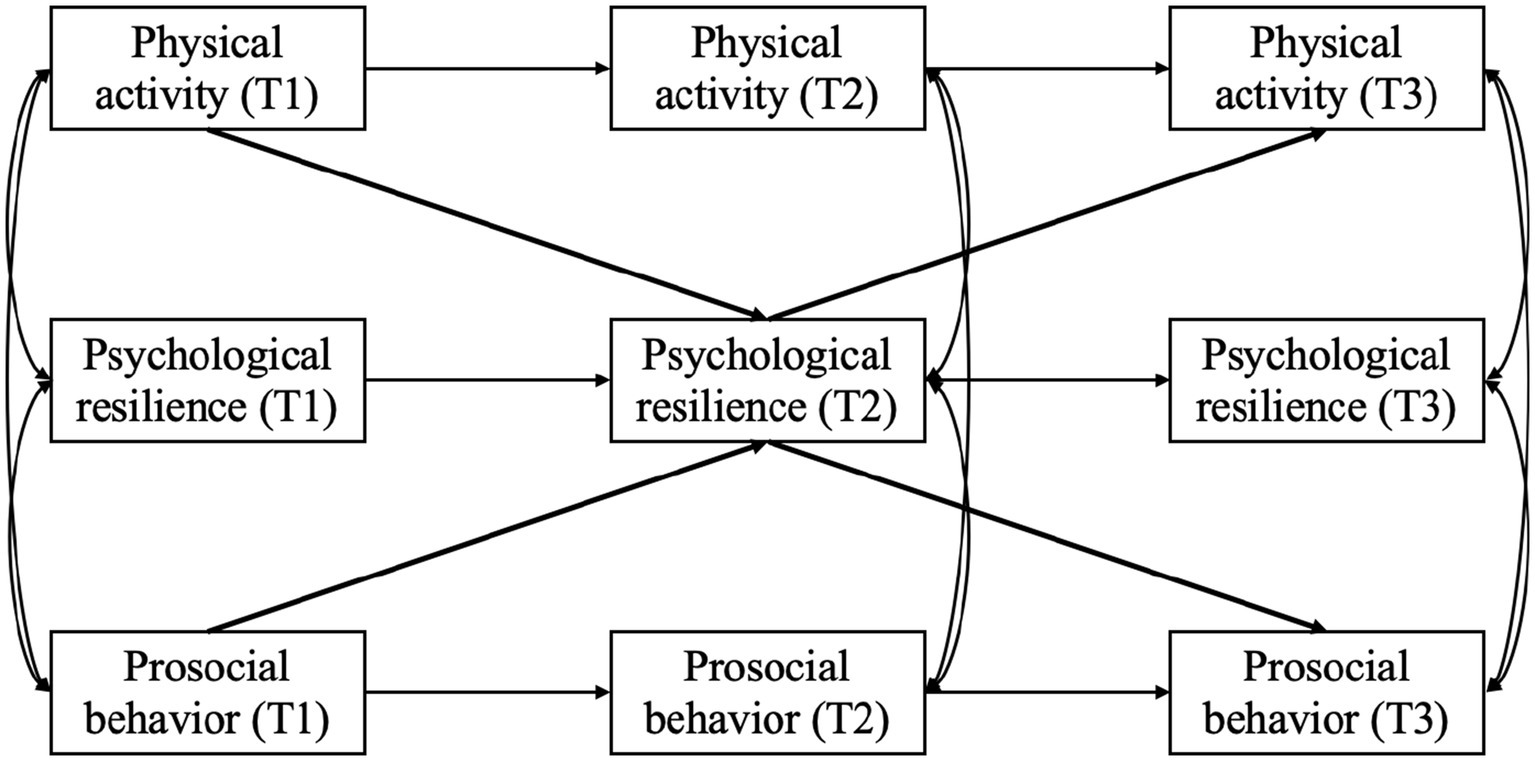

The present study aimed to fill this gap by using a longitudinal design with three measurement points to examine whether psychological resilience mediates the relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior, in both directions, over time among rural left-behind children in China (Figure 1). It was hypothesized that: (1) physical activity is positively related to psychological resilience, which in turn linked to prosocial behavior; (2) prosocial behavior is positively linked to psychological resilience, which in turn, related to physical activity; and (3) psychological resilience serves as a longitudinal mediator in both pathways.

Method

Participants

A convenience sampling method was used. Fifth- and sixth-grade students from three rural primary schools in Ji’an City voluntarily participated this study. Ji’an City’s rural areas are primarily sustained by traditional agriculture, and average household income remains below the national rural average. Many working-age adults migrate to urban centers for employment, leaving a considerable number of children in the care of relatives. Local schools have limited educational resources and less qualified teaching staff compared to urban schools. A convenience sampling method was adopted due to the wide geographic distribution of rural schools and the need for cooperation from both school administrators and parents. This approach ensured feasibility and facilitated participant access under real-world field conditions.

Eligibility was determined using a screening item that explicitly asked whether both parents had been employed away from home for more than 6 months, or whether one parent had been employed away from home while the other lacked caregiving capacity. Participants who responded “Yes” to this item were classified as left-behind children and included in the study.

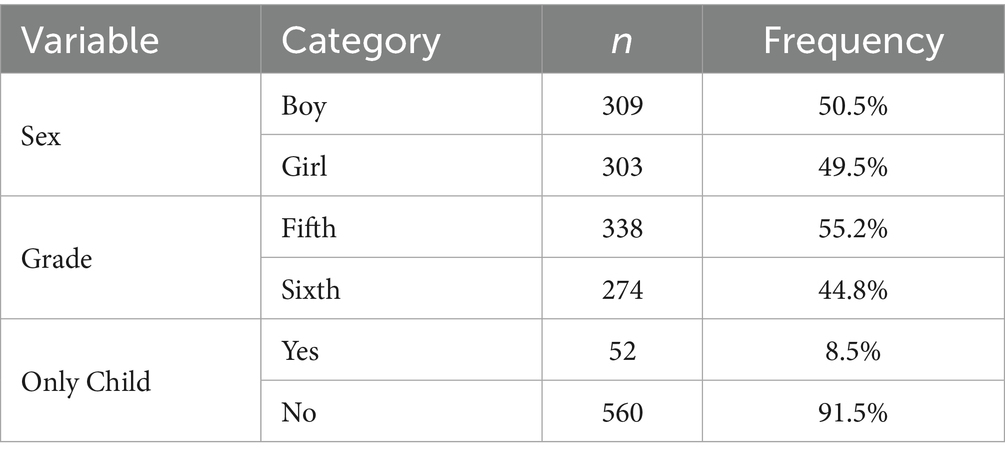

The final sample consisted of 612 participants who completed all three assessments (retention rate: 85%). Among them, 309 participants (50.5%) were male and 303 (49.5%) were female; 338 (55.2%) were in fifth grade and 274 (44.8%) were in sixth grade, corresponding to an approximate age range of 10 to 12 years based on the standard Chinese education system. Participant demographic information is presented in Table 1. The initial pool consisted of 716 valid questionnaires collected in October 2023 (T1), 699 in January 2024 (T2), and 711 in April 2024 (T3). Cases were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: excessive missing data (i.e., more than two-thirds of items unanswered), inconsistencies between positively and negatively worded items, patterned or uniform responses, or missing identification information. Participant attrition was primarily due to school transfers, graduation, or absences. Attrition analyses indicated no significant differences at T1 between participants who dropped out and those who completed all three waves in physical activity (t = −0.017, p > 0.05), prosocial behavior (t = 0.994, p > 0.05), or psychological resilience (t = −1.645, p > 0.05), suggesting that attrition was not systematic.

Procedure

This study adopted a three-wave longitudinal design (T1, T2, and T3) conducted over a six-month period, with three-month intervals between waves. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB-JXNU-PEC-20230901). Through three collaborating public schools in Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province, written informed consent forms detailing the nature of this longitudinal study were distributed to the parents or legal guardians of students in Grades 5 and 6. A total of 612 students were included in the final sample after obtaining parental consent. Data were collected at three time points: October 2023 (T1), January 2024 (T2), and April 2024 (T3).

Before each data collection, trained research staff visited the classrooms and explained the study purpose, procedures, and confidentiality protections in age-appropriate language. Students were informed that participation was entirely voluntary and that they could skip any question or withdraw at any time without penalty. After confirming comprehension, the researchers obtained verbal assent from each student before administering the questionnaires.

Participants completed self-report questionnaires assessing physical activity, psychological resilience, and prosocial behavior in a classroom setting, which took approximately 10–15 min to complete. Physical activity was assessed through self-report to ensure a culturally appropriate, feasible, and minimally intrusive method for large-scale, longitudinal data collection among rural left-behind children. To ensure comprehension, all instruments were validated among Chinese children and reviewed for age-appropriate language. A pilot test with 30 students of similar age from non-participating schools was conducted to evaluate comprehension and optimize wording clarity.

During data collection, trained research assistants read standardized instructions aloud, provided sample items to demonstrate the response format, and closely monitored the session. When a student appeared confused, assistants provided neutral clarifications without suggesting answers. For example, when a student did not understand the resilience item “I can recover quickly from unpleasant experiences,” the assistant clarified, “This question is asking whether you can make yourself feel better quickly after something makes you unhappy.”

Measures

Physical activity questionnaire

Physical activity was measured by the Chinese version of the Physical Activity Rating Scale [(42); 4 items] and three additional questions assessing the psychological perception of physical activity (43). The original PARS evaluates behavioral dimensions of physical activity, including intensity, average duration per session, frequency, and subjective feelings after exercise. The three additional items assess emotional preference (e.g., “Do you enjoy physical activity?”), perceived benefits (e.g., “Do you believe regular exercise is beneficial for your health?”), and self-motivation (e.g., “Do you engage in physical activity without being prompted by others?”). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with higher scores indicating greater engagement in and more positive perceptions of physical activity. For example, exercise intensity was assessed on a scale ranging from 1 (light activities such as walking) to 5 (vigorous and sustained activities such as competitive swimming). Frequency ranged from 1 (less than once per month) to 5 (almost daily). Higher total scores indicate greater physical activity engagement. Because both the behavioral and psychological perception components are theoretically relevant to children’s overall engagement in physical activity and have been integrated in prior research (43), the seven items were combined into a single composite score.

This integration was supported by satisfactory internal consistency across all three time points (Cronbach’s α = 0.84 at T1, 0.78 at T2, and 0.78 at T3) and strong construct validity as indicated by confirmatory factor analyses (T1: χ2/df = 1.26, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.02; T2: χ2/df = 2.37, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05; T3: χ2/df = 1.81, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.04). Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values indicated good sampling adequacy (T1 = 0.88; T2 = 0.85; T3 = 0.85), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant across all time points (all p < 0.001).

Adolescent prosocial behavior scale

Prosocial behavior was assessed using the Chinese version of the Adolescent Prosocial Tendencies Scale (44, 45). The scale consists of 26 items measuring six types of prosocial tendencies: anonymous, public (overt), altruistic, emotional, compliant, and urgent. Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely untrue) to 5 (completely true), with higher scores indicating greater prosocial tendencies. An example item is: “I often help others, even when I do not receive any benefit in return.”

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients demonstrated high reliability at all measurement points: 0.92 (T1), 0.93 (T2), and 0.93 (T3). Confirmatory factor analyses showed good structural validity (T1: χ2/df = 2.20, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.04; T2: χ2/df = 3.00, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06; T3: χ2/df = 1.99, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04). KMO values confirmed sampling adequacy (T1 = 0.95; T2 = 0.94; T3 = 0.95), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant across measurement points (all p < 0.001).

Psychological resilience scale

Psychological resilience was evaluated using the Resilience Scale for Adolescents (46). The scale consists of 27 items across five subscales: goal focus, emotional control, positive cognition, family support, and interpersonal assistance. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely untrue) to 5 (completely true). After reverse coding specified items, higher scores reflected greater psychological resilience. An example item is: (“I believe adversity can be motivating for individuals”).

Cronbach’s alpha indicated acceptable internal consistency: 0.83 (T1), 0.87 (T2), and 0.87 (T3). Confirmatory factor analyses supported structural validity (T1: χ2/df = 2.82, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06; T2: χ2/df = 3.53, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.06; T3: χ2/df = 2.73, CFI = 0.90, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.05). KMO values supported good sampling adequacy (T1 = 0.81; T2 = 0.84; T3 = 0.88), with significant Bartlett’s tests at all three time points (all p < 0.001).

Analytical strategy

Data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 and Mplus 8.3. Because all variables were collected via self-report measures, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted to assess common method bias using unrotated exploratory factor analysis across all measurement points (47). Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation analyses were then performed for all primary variables. To determine whether gender should be included as a covariate in the hypothesized cross-lagged mediation model and whether there were significant changes in the study variable across time, a 3 (time: T1, T2, T3) × 2 (gender: male, female) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted separately for physical activity, prosocial behavior, and psychological resilience. In these analyses, assessment time was the within-subjects factor and gender as the between-subjects factor.

To examine the longitudinal relationships among physical activity, psychological resilience, and prosocial behavior, a structural equation model (SEM) was conducted using Mplus 8.3. A bidirectional cross-lagged mediation model was specified, which simultaneously tested whether (1) physical activity at Time 1 was linked to prosocial behavior at Time 3 via psychological resilience at Time 2, and (2) prosocial behavior at Time 1 was related to physical activity at Time 3 via psychological resilience at Time 2. The model was estimated using the robust maximum likelihood estimator (estimator = MLR). Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square statistic (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Comparative model fit was assessed using chi-square difference tests (Δχ2/Δdf) to determine the most appropriate model. Indirect effects in the final model were tested using the bias-corrected bootstrap method with 5,000 resamples and 95% confidence intervals. Anonymized data is available online: https://osf.io/my6nf/?view_only=4d8596e464844167a29a4dbf2e8bee36

Results

Common method bias test

Twelve factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted at each time point. The variance explained by the first factor was 19.73% at T1, 23.99% at T2, and 22.61% at T3, all below the recommended 40% threshold, indicating that common method bias was not a major concern in this study.

Preliminary analysis

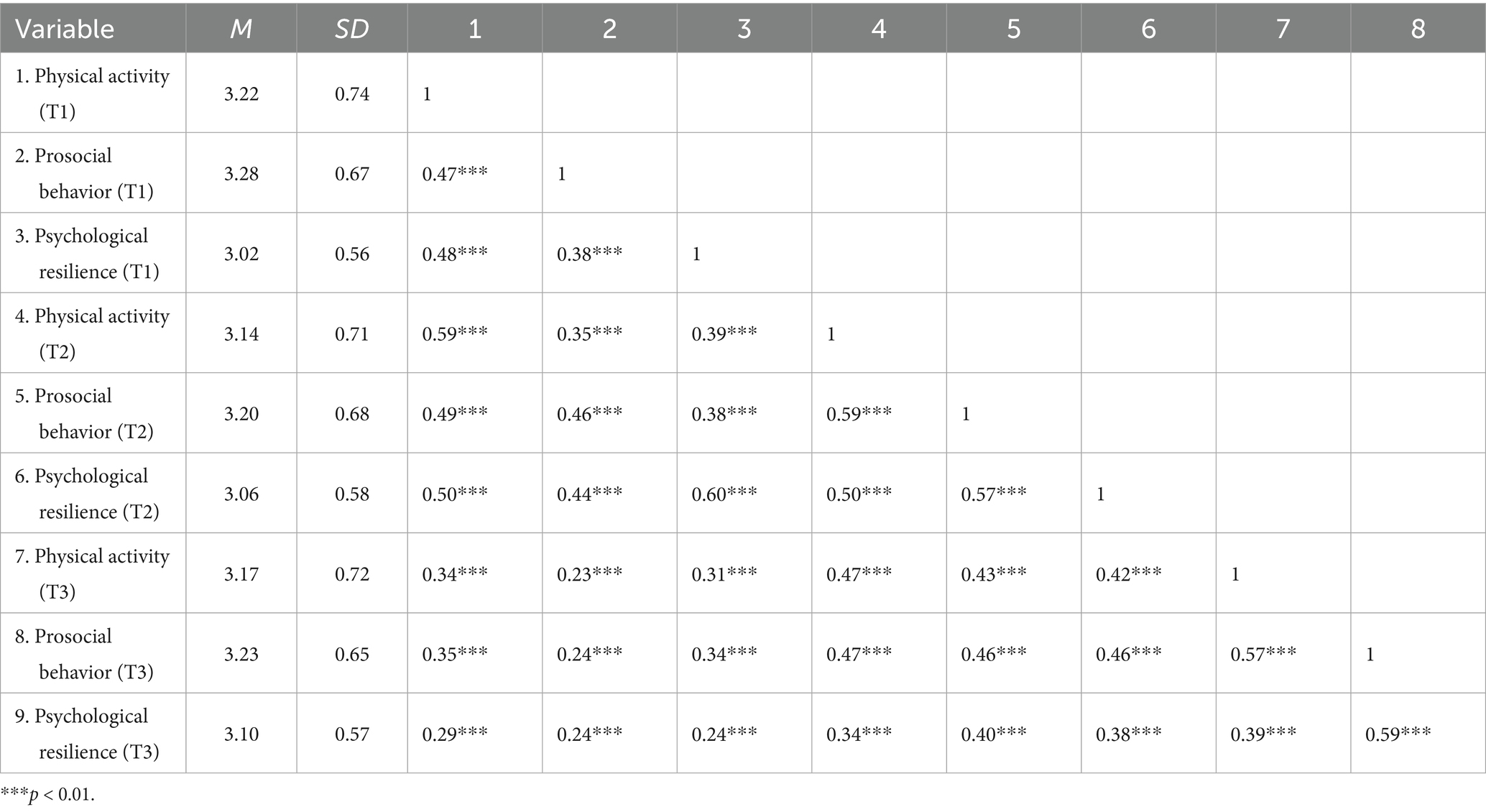

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations among physical activity, prosocial behavior, and psychological resilience across the three time points are presented in Table 2. All variables were significantly correlated with one another at each time point (ps < 0.001), indicating strong concurrent associations. Moreover, significant cross-time correlations were observed between the same constructs measured at different time points, suggesting that physical activity, prosocial behavior, and psychological resilience remained relatively stable over the six-month study period.

Physical activity showed a significant change over time, F(2, 1,220) = 3.24, p = 0.044, η2 = 0.01, indicating that levels of physical activity varied across the three time points. Follow-up Bonferroni analysis indicated that physical activity at T1 was significantly higher than at T2 and T3. The main effect of gender was not significant, F(1, 610) = 0.08, p = 0.782, nor was the interaction between time and gender, F(2, 1,220) = 2.81, p = 0.065. Prosocial behavior also showed significant changes over time, F(2, 1,220) = 4.13, p = 0.018, η2 = 0.01. Follow-up Bonferroni analysis revealed that prosocial behavior at T1 was significantly higher than at T2 and T3. The main effect of gender was not significant, F(1, 610) = 0.74, p = 0.39, nor was the time × gender interaction, F(2, 1,220) = 0.59, p = 0.549. Similarly, psychological resilience showed a significant main effect of time, F(2, 1,220) = 4.51, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.01. Follow-up Bonferroni analysis showed that psychological resilience at T3 was significantly higher than at T1 and T2. The main effect of gender was not significant, F(1, 610) = 2.27, p = 0.133, and the interaction between time and gender was also not significant, F(2, 1,220) = 0.30, p = 0.716. Because changes in the study variables were not related to gender, this variable was not included as a covariate in the subsequent longitudinal mediation analyses.

Longitudinal mediation analysis

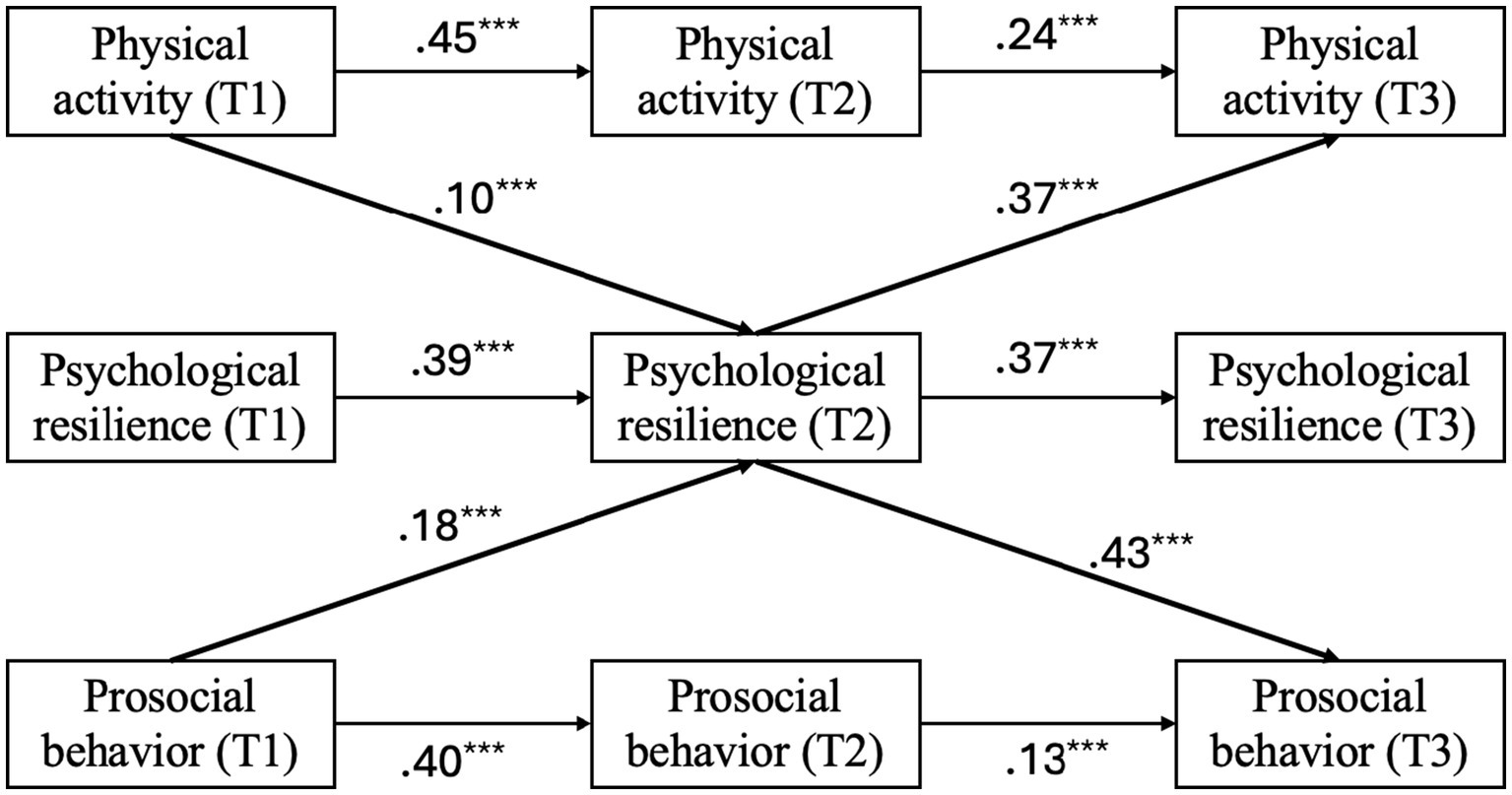

The original model (Figure 2) exhibited suboptimal fit to the data: χ2(17) = 200.71, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.90; TLI = 0.81; RMSEA = 0.13; SRMR = 0.13. Both hypothesized mediation pathways were statistically supported in this initial model: physical activity at T1 was associated with prosocial behavior at T3 via psychological resilience at T2 (indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.02, p = 0.01; 95% CI [0.01, 0.08]), and the reverse path from prosocial behavior to physical activity was also significant (indirect effect = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.04, 0.10]). However, interpretation should be made with caution due to the poor model fit. To improve model specification, three theoretically grounded paths were added based on modification indices: (1) T1 physical activity → T2 prosocial behavior; (2) T2 prosocial behavior → T3 psychological resilience; and (3) T2 physical activity → T3 prosocial behavior.

Figure 2. Original study model with standardized coefficients. Thick paths represent primary paths of research interest. For clarity, error terms and covariances are omitted. ***p < 0.01.

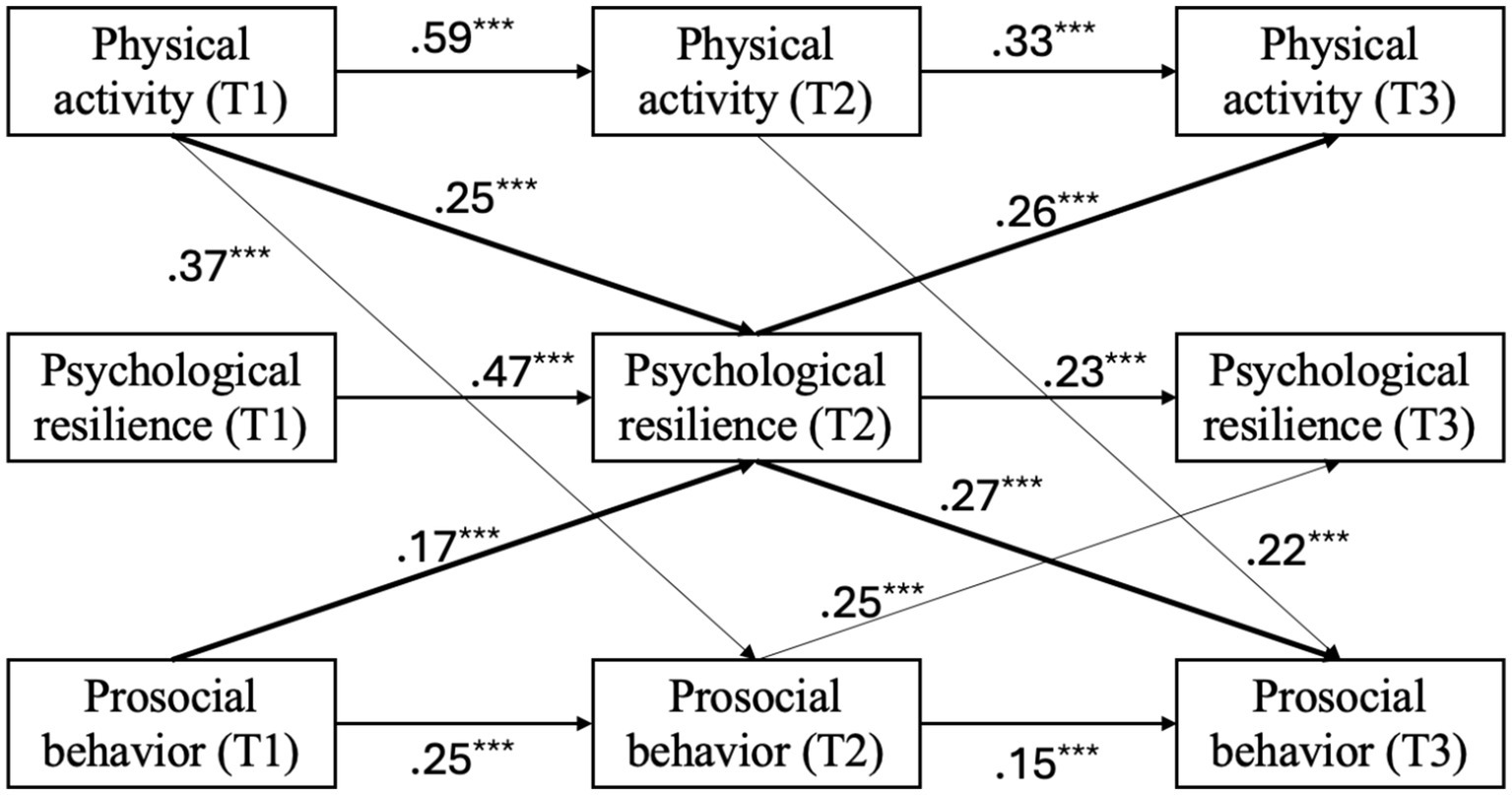

The revised exploratory model (Figure 3) showed an improved fit: χ2(14) = 47.28, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.04. A chi-square difference test indicated that the revised model provided a significantly better fit than the original model, Δχ2(3) = 153.43, p < 0.001. Within this final model, both hypothesized mediation pathways were supported. The path from T1 physical activity to T3 prosocial behavior was significant, with psychological resilience at T2 serving as a significant mediator (standardized indirect effect = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.03, 0.10]). Likewise, the reverse path from T1 prosocial behavior to T3 physical activity was also significant, with psychological resilience again emerging as a significant mediator (standardized indirect effect = 0.04, SE = 0.01, p < 0.001; 95% CI [0.02, 0.07]).

Figure 3. Modified final study model with standardized coefficients. Thick paths represent primary paths of research interest. Thin paths were added based on theoretical rationale and modification indices. For clarity, error terms and covariances are omitted. ***p < 0.01.

Further analyses examined whether specific subdimensions of psychological resilience mediated the longitudinal association between physical activity and prosocial behavior. Neither subdimension showed a significant mediating effect, and thus overall psychological resilience appeared to function as a more integrative construct linking the two. Detailed model information is available in Supplementary Material 1 and Supplementary Table S1.

Discussion

This three-wave longitudinal study among rural left-behind children identified psychological resilience as a key longitudinal mediator in the bidirectional relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior. To our knowledge, this is among the first to demonstrate that psychological resilience can not only explain how physical activity is related to prosocial behavior, but also how prosocial behavior, in turn, is associated with sustained physical activity through psychological resilience. These findings suggest that psychological resilience can be a critical developmental bridge between physical and social functioning, highlighting the potential of integrated approaches that simultaneously promote physical activity and prosocial engagement to support psychological well-being in vulnerable populations.

The novel longitudinal evidence for a bidirectional relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior among rural left-behind children is highlighted. While prior research has primarily emphasized how physical activity is linked to prosocial behavior through mechanisms such as enhanced cooperation, emotional regulation, and group cohesion (17, 22), the current findings contribute to the small but growing literature suggesting that prosocial behavior may also support engagement in physical activity. Extending limited prior research conducted among older adults (24) and other sociocultural context (23, 48), the present findings suggest that left-behind children who exhibit higher levels of prosocial behavior may also be more inclined to engage in physical activity. This idea is similar to past research suggesting prosocial behavior is related to cooperative, group-oriented activities and to seek social connectedness (49) which is beneficial to children’s social adjustment (50). Future research should investigate these mechanisms specific to this population persistence. This reciprocal dynamic underscore the importance of conceptualizing physical and social development as interdependent and mutually reinforcing processes.

Psychological resilience emerged as a key mediating mechanism in the bidirectional relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior over time. Psychological resilience in this context facilitates the translation of behavioral engagement into socioemotional growth, and vice versa. These findings extend resilience theory (51) by situating resilience within a reciprocal developmental process involving both physical and social domains. Specifically, physical activity may foster resilience by providing structured opportunities for overcoming challenges and promoting positive affectivity, capacities that support prosocial behaviors (36, 52, 53). This is consistent with the neurological evidence suggesting that physical exercise contributes to cognitive improvement and stress resilience in humans and animal models (35). Conversely, prosocial engagement may enhance children’s sense of competence, autonomy, and connectedness (54), thereby strengthening psychological resilience and encouraging future participation in physical activity. This is particularly meaningful for rural left-behind children, whose psychological resilience is often tested by prolonged parental absence and limited social support (55). By identifying resilience as both an outcome and a mechanism of change, the current study underscores its role as a developmental catalyst that amplifies the mutually reinforcing benefits of physical activity and prosocial behavior.

Additionally, physical activity and prosocial behavior were higher at Time 1 than at later waves, whereas psychological resilience increased by Time 3. These temporal patterns may reflect contextual influences such as seasonal variation or changes in academic workload, with greater physical activity and social engagement early in the semester and reduced participation as demands intensified. The later increase in resilience may indicate cumulative adaptation, as participants developed coping skills over time or became more self-aware through repeated assessments. These temporal dynamics likely shaped the mediation process, suggesting that the indirect effect of early physical activity on later prosocial behavior through resilience may vary under different seasonal or contextual conditions.

To improve model fit and better capture the dynamic interplay among variables, three theoretically grounded cross-lagged paths were added: T1 physical activity → T2 prosocial behavior, T2 prosocial behavior → T3 psychological resilience, and T2 physical activity → T3 prosocial behavior. These additions were supported by prior research on reciprocal links between physical and social functioning (17, 23) and the role of social–emotional factors in psychological resilience (54). While theory informed these changes, they were introduced post hoc based on modification indices; thus, the final model should be interpreted as exploratory. Replication with pre-registered hypotheses and independent samples is recommended to confirm these pathways.

Implications

These findings carry important implications for rural left-behind children in China, a population at heightened risk for socioemotional challenges due to prolonged parental separation. Physical activity, when embedded in safe and socially supportive environments, can serve as a low-cost, scalable intervention to promote both psychological resilience and social connectedness. For example, schools could integrate 30 min of cooperative team sports (e.g., basketball or badminton) three times per week into physical education classes, complemented by 15-min weekly prosocial skill-building sessions such as peer tutoring, group problem-solving, or empathy-based discussions. Such combined approaches have been shown to improve social functioning and psychological well-being among children and adolescents (37). Beyond the Chinese context, the results have broader relevance for vulnerable youth globally, including those facing displacement, marginalization, or familial disruption [e.g., sent-away children; (56)]. Theoretically, the demonstrated bidirectional links between physical and social functioning challenge static, linear models of development and call for more dynamic, reciprocal frameworks. Practically, this research supports designing interventions that concurrently promote prosocial engagement, physical activity, and psychological resilience, particularly in under-resourced settings, thereby advancing holistic and sustainable well-being among at-risk youth.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Although participants were recruited from multiple schools, the sample was limited to rural left-behind children in Ji’an City, Jiangxi Province. Given the socioeconomic and educational conditions of the study area, the findings should be generalized to other rural regions with caution, especially to areas with higher economic development or different resource structures. Caution is also warranted when applying these results to international contexts with differing sociocultural and institutional environments. The study adopted a convenience sampling approach, as participating schools were selected based on accessibility and administrative permission, which may have influenced the socioeconomic composition of the sample. Future studies should employ random sampling with broader geographic coverage to enhance representativeness and validate the present findings. Only grade level, rather than participants’ exact ages, was recorded, limiting the precision of developmental analyses. Therefore, these results may not extend to left-behind children from other socioeconomic or regional backgrounds to those living in other countries, or to broader populations of vulnerable youth at different developmental stages without careful cultural and contextual adaptation.

Second, all data were obtained through child self-report, which raises concerns regarding the accuracy of behavioral assessments. For instance, physical activity was measured via self-reported recall, which may be subject to memory errors and imprecise estimation of the actual frequency and intensity of engagement. The absence of parent, teacher, or peer reports may affect the validity of behavioral assessments, particularly for prosocial behavior. However, this approach was chosen for its feasibility in large-scale, school-based multiwave data collection. Likewise, prosocial behavior is vulnerable to social desirability bias, with children potentially overreporting helpful or cooperative actions. Future research would benefit from incorporating more objective assessments, such as accelerometers to quantify physical activity or teacher and peer reports to corroborate prosocial behavior ratings, to improve measurement validity. When available, sensitivity analyses comparing self-reported physical activity with school physical education attendance records could further assess self-report bias.

Third, while the three-wave design over a six-month period allows for valuable longitudinal insights, future studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to capture more stable developmental trajectories and enduring effects. Fourth, while the model supports bidirectional associations over time, these findings should be interpreted with caution, as statistical reciprocity in SEM does not imply true bidirectional causality. Also, it should be noted that the final model, developed based on modification indices, is exploratory in nature. To verify its robustness and mitigate overfitting risks, future research could adopt pre-registered designs and cross-validation approaches to test the added paths in independent samples. Experimental or intervention-based studies are necessary to confirm the directional mechanisms identified. Finally, although the model offers a strong theoretical foundation for exploring psychological resilience as a dynamic mechanism within developmental cascades, it assumes that psychological resilience functions symmetrically across behavioral and social domains, which may oversimplify the nuanced roles psychological resilience plays in different contexts.

Future directions

Building on the current findings, several avenues warrant further investigation. First, future research should develop and evaluate school- or community-based interventions that combine physical activity with prosocial skill training to enhance psychological resilience among left-behind and other marginalized children. Embedding resilience-building activities within physical education or peer mentoring programs could help establish causal links and inform practical applications. Second, longitudinal studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to assess the stability of the observed developmental pathways across time and contexts. Replicating this model in different regions of China and among diverse youth populations (e.g., migrant or urban low-income children) would clarify the cultural and contextual generalizability of the findings. Third, incorporating multi-informant approaches (e.g., parent, teacher, or peer reports) and objective indicators, such as accelerometers for physical activity or observational assessments of prosocial behavior, would enhance measurement validity. Lastly, examining moderating factors, such as caregiving arrangements, school support, or socioeconomic context, as well as testing additional mediators (e.g., emotion regulation, peer attachment, self-efficacy), could deepen understanding of the mechanisms linking physical activity, psychological resilience, and prosocial behavior.

Conclusion

This study provides novel longitudinal evidence of a bidirectional relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior, with psychological resilience serving as a key mediating mechanism among rural left-behind children in China. By identifying psychological resilience as both a pathway and a product of behavioral and social engagement, the findings advance theoretical models of child development and highlight critical actionable points for intervention. Promoting physical activity and prosocial engagement simultaneously may offer a scalable, low-cost strategy to support the well-being of structurally disadvantaged youth. Future research should build on this foundation to design contextually sensitive, developmentally appropriate, and mechanism-informed programs that foster holistic development across diverse populations.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/my6nf/?view_only=4d8596e464844167a29a4dbf2e8bee36.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Jiangxi Normal University Institutional review board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

DH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. XX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PW: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JX: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of Jiangxi Universities [Grant no. TY21109] and the Innovation Special Fund Project for Graduate Students of Jiangxi Province [Grant no. YC2023-S321]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or decision to publish.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1690603/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Gu, C. Urbanization: processes and driving forces. Sci China Earth Sci. (2019) 62:1351–60. doi: 10.1007/s11430-018-9359-y

2. Gong, P, Liang, S, Carlton, EJ, Jiang, Q, Wu, J, Wang, L, et al. Urbanisation and health in China. Lancet. (2012) 379:843–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61878-3

3. Cheng, J, and Sun, YH. Depression and anxiety among left-behind children in China: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. (2015) 41:515–23. doi: 10.1111/cch.12221

4. UNICEF. Country office annual report 2018- China 2018. Available online at: https://sites.unicef.org/about/annualreport/files/China_2018_COAR.pdf

5. Zhou, Y, Cheng, Y, Liang, Y, Wang, J, Li, C, Du, W, et al. Interaction status, victimization and emotional distress of left-behind children: a national survey in China. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 118:105348. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105348

6. Li, Q, Liu, G, and Zang, W. The health of left-behind children in rural China. China Econ Rev. (2015) 36:367–76. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2015.04.004

7. Wang, M, Sokol, R, Luan, H, Perron, BE, Victor, BG, and Wu, S. Mental health service interventions for left-behind children in mainland China: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Child Youth Serv Rev. (2020) 117:105304. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105304

8. Man, Y, Mengmeng, L, Lezhi, L, Ting, M, and Jingping, Z. The psychological problems and related influential factors of left-behind adolescents (LBA) in Hunan, China: a cross sectional study. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:163. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0639-2

9. Penner, LA, Dovidio, JF, Piliavin, JA, and Schroeder, DA. Prosocial behavior: multilevel perspectives. Annu Rev Psychol. (2005) 56:365–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070141

10. Lan, X, and Wang, W. Is early left-behind experience harmful to prosocial behavior of emerging adult? The role of parental autonomy support and mindfulness. Curr Psychol. (2022) 41:1842–55. doi: 10.1007/s12144-020-00706-3

11. Gee, DG. Sensitive periods of emotion regulation: influences of parental care on Frontoamygdala circuitry and plasticity. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. (2016) 2016:87–110. doi: 10.1002/cad.20166

12. Becker, K, Abraham, A, Kindler, J, Helmeke, C, and Braun, K. Exposure to neonatal separation stress alters exploratory behavior and corticotropin releasing factor expression in neurons in the amygdala and hippocampus. Dev Neurobiol. (2007) 67:617–29. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20372

13. Danese, A, and McEwen, BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. (2012) 106:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

14. Katsantonis, I, and McLellan, R. The role of parent–child interactions in the association between mental health and prosocial behavior: evidence from early childhood to late adolescence. Int J Behav Dev. (2024) 48:59–70. doi: 10.1177/01650254231202444

15. Deneault, A-A, Hammond, SI, and Madigan, S. A meta-analysis of child–parent attachment in early childhood and prosociality. Dev Psychol. (2023) 59:236–55. doi: 10.1037/dev0001484

16. Arbuthnott, KD. Nature exposure and social health: prosocial behavior, social cohesion, and effect pathways. J Environ Psychol. (2023) 90:102109. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2023.102109

17. Lu, TC, Wang, CX, Tao, BL, Sui, HR, and Yan, J. The relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior of college students: a mediating role of self-perception. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0271759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271759

18. Hui, Z, Kelei, G, Chao, L, Qishuai, M, Weiwei, T, and Yao, S. The relationship between physical exercise and prosocial behavior of junior middle school students in post-epidemic period: the chain mediating effect of emotional intelligence and sports learning motivation and gender differences. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2022) 15:2745–59. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S370495

19. Cheng, W, and Jiao, L. The mediation effect of peer relation and positive emotion between campus sports atmosphere and teenagers’ subjective well-being. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1645. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1471645

20. Valkenborghs, SR, Noetel, M, Hillman, CH, Nilsson, M, Smith, JJ, Ortega, FB, et al. The impact of physical activity on brain structure and function in youth: a systematic review. Pediatrics. (2019) 144. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-4032

21. Ishihara, T, Hashimoto, S, Tamba, N, Hyodo, K, Matsuda, T, and Takagishi, H. The links between physical activity and prosocial behavior: an fNIRS hyperscanning study. Cereb Cortex. (2024) 34:509. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhad509

22. Li, J, and Shao, W. Influence of sports activities on prosocial behavior of children and adolescents: a systematic literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:6484. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19116484

23. Moore, QL, Christopher, K, Rachel, K, Daphne, F, and Jackson, F. The role of prosocial behavior in promoting physical activity, as an Indicator of resilience, in a low-income neighborhood. Behav Med. (2020) 46:353–65. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2020.1712647

24. Foy, CG, Vitolins, MZ, Case, LD, Harris, SJ, Massa-Fanale, C, Hopley, RJ, et al. Incorporating prosocial behavior to promote physical activity in older adults: rationale and design of the program for active aging and community engagement (PACE). Contemp Clin Trials. (2013) 36:284–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.07.004

25. Masten, AS. Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Dev. (2014) 85:6–20. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12205

26. Fletcher, D, and Sarkar, M. Psychological resilience. Eur Psychol. (2013) 18:12–23. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

27. Ryan, RM, and Deci, EL. Self-determination theory: basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness Guilford Publications (2017).

28. Milne, HM, Wallman, KE, Guilfoyle, A, Gordon, S, and Courneya, KS. Self-determination theory and physical activity among breast cancer survivors. J Sport Exerc Psychol. (2008) 30:23–38. doi: 10.1123/jsep.30.1.23

29. Qiu, W, Huang, C, Xiao, H, Nie, Y, Ma, W, Zhou, F, et al. The correlation between physical activity and psychological resilience in young students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. (2025) 16:1557347. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1557347

30. Liu, M, Liu, H, Qin, Z, Tao, Y, Ye, W, and Liu, R. Effects of physical activity on depression, anxiety, and stress in college students: the chain-based mediating role of psychological resilience and coping styles. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1396795. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1396795

31. Husain, H, Samsudin, S, Ayub, AFM, Ahmad, MF, and Afwan, N. A systematic literature review on the impact of participation in sport and physical activities on psychological resilience. Int J Public Health Sci. (2024) 13:1727. doi: 10.11591/ijphs.v13i4.24345

32. Xu, S, Liu, Z, Tian, S, Ma, Z, Jia, C, and Sun, G. Physical activity and resilience among college students: the mediating effects of basic psychological needs. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3722. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073722

33. Ozkara, AB, Kalkavan, A, Alemdag, S, and Alemdag, C. The role of physical activity in psychological resilience. Balt J Sport Health Sci. (2016) 3:24–9. doi: 10.33607/bjshs.v3i102.62

34. Deuster, PA, and Silverman, MN. Physical fitness: a pathway to health and resilience. US Army Med Dep J. (2013) 24+. Available online at: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A352490358/AONE?u=acd_galeaccess&sid=googleScholar&xid=ef7cabdf

35. Arida, RM, and Teixeira-Machado, L. The contribution of physical exercise to brain resilience. Front Behav Neurosci. (2021) 14:626769. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.626769

36. Esparza-Reig, J, Martí-Vilar, M, González-Sala, F, Merino-Soto, C, and Toledano-Toledano, F. Social support and resilience as predictors of prosocial behaviors before and during COVID-19. Healthcare. (2022) 10:1669. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10091669

37. Xue, S, Kaufman, MR, Xing, Z, Shunan, X, Chengcheng, N, Rui, Z, et al. Resilience and prosocial behavior among Chinese university students during COVID-19 mitigation: testing mediation and moderation models of social support. Psychol Res Behav Manag. (2022) 15:1531–43. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S364356

38. Padilla-Walker, LM, and Carlo, G. Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press. (2014).

39. Rao, B, and Sharma, V. Prosocial behaviour as a predictor of psychological resilience in single parents: a quantitative exploration. Int J Environ Sci. New York, NY. (2025) 7370–5. doi: 10.64252/bv9eqw66

40. Galli, N, and Gonzalez, SP. Psychological resilience in sport: a review of the literature and implications for research and practice. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol. (2015) 13:243–57. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2014.946947

41. Fletcher, D, and Sarkar, M. A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2012) 13:669–78. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007

42. Liang, D. Stress level of college students and its relationship with physical exercise. Children Mental Health J. (1994) 8:2.

43. Li, R, Huang, D, Li, L, and Liao, H. The effect of physical exercise on prosocial behavior among college students: The mediating role of peer relationships. Proceedings of the 13th National Sports Science Conference – Special session on school sports Chinese Society of Sports Science (2023).

44. Carlo, G, and Randall, BA. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. (2002) 31:31–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440

45. Kou, Y, Hong, H, Tan, C, and Li, L. Revision of the adolescent prosocial tendencies scale. Psychol Dev Educ. (2007) 23:112–7.

46. Hu, Y-Q, and Gan, Y-Q. Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychol Sin. (2008) 902–912. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2008.00902

47. Podsakoff, PM, MacKenzie, SB, Lee, J-Y, and Podsakoff, NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. (2003) 88:879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

48. Galárraga, O, Bohlen, LC, Dunsiger, SI, Lee, HH, Emerson, JA, Boyle, HK, et al. Small sustainable monetary donation-based incentives to promote physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Health Psychol. (2020) 39:265–8. doi: 10.1037/hea0000818

49. Eisenberg, N, and Mussen, PH. The roots of prosocial behavior in children. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press (1989).

50. Crick, NR. The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children's future social adjustment. Child Dev. (1996) 67:2317–27.

51. Van Breda, AD. Resilience theory: A literature review. Pretoria, South Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: South African Military Health Service (2001). 613 p.

52. Dovidio, JF, Piliavin, JA, Schroeder, DA, and Penner, LA. The social psychology of prosocial behavior. New York, NY: Psychology Press (2017).

53. Haller, E, Lubenko, J, Presti, G, Squatrito, V, Constantinou, M, Nicolaou, C, et al. To help or not to help? Prosocial behavior, its association with well-being, and predictors of prosocial behavior during the coronavirus disease pandemic. Front Psychol. (2022) 12:775032. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.775032

54. Deci, EL, and Ryan, RM. Self-determination theory. In: AM Paul, V Lange, AW Kruglanski, and ET Higgins editors. Handbook of theories of social psychology, vol. 1 (2012). 416–36.

55. Su, S, Li, X, Lin, D, and Zhu, M. Future orientation, social support, and psychological adjustment among left-behind children in rural China: a longitudinal study. Front Psychol. (2017) 8:1309. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01309

Keywords: physical activity, prosocial behavior, psychological resilience, rural left-behind children, longitudinal mediation

Citation: Huang D, Xiong X, Wang P and Xu J (2025) The reciprocal relationship between physical activity and prosocial behavior among rural left-behind children: a cross-lagged mediation analysis of psychological resilience. Front. Public Health. 13:1690603. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2025.1690603

Edited by:

Fenghua Sun, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaReviewed by:

Yufei Qi, Central South University, ChinaJing Liu, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Copyright © 2025 Huang, Xiong, Wang and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Peiyi Wang, cGVpeWkud2FuZ0B1dHJndi5lZHU=

†These authors share first authorship

Dawu Huang

Dawu Huang Xin Xiong

Xin Xiong Peiyi Wang

Peiyi Wang Juan Xu

Juan Xu