Abstract

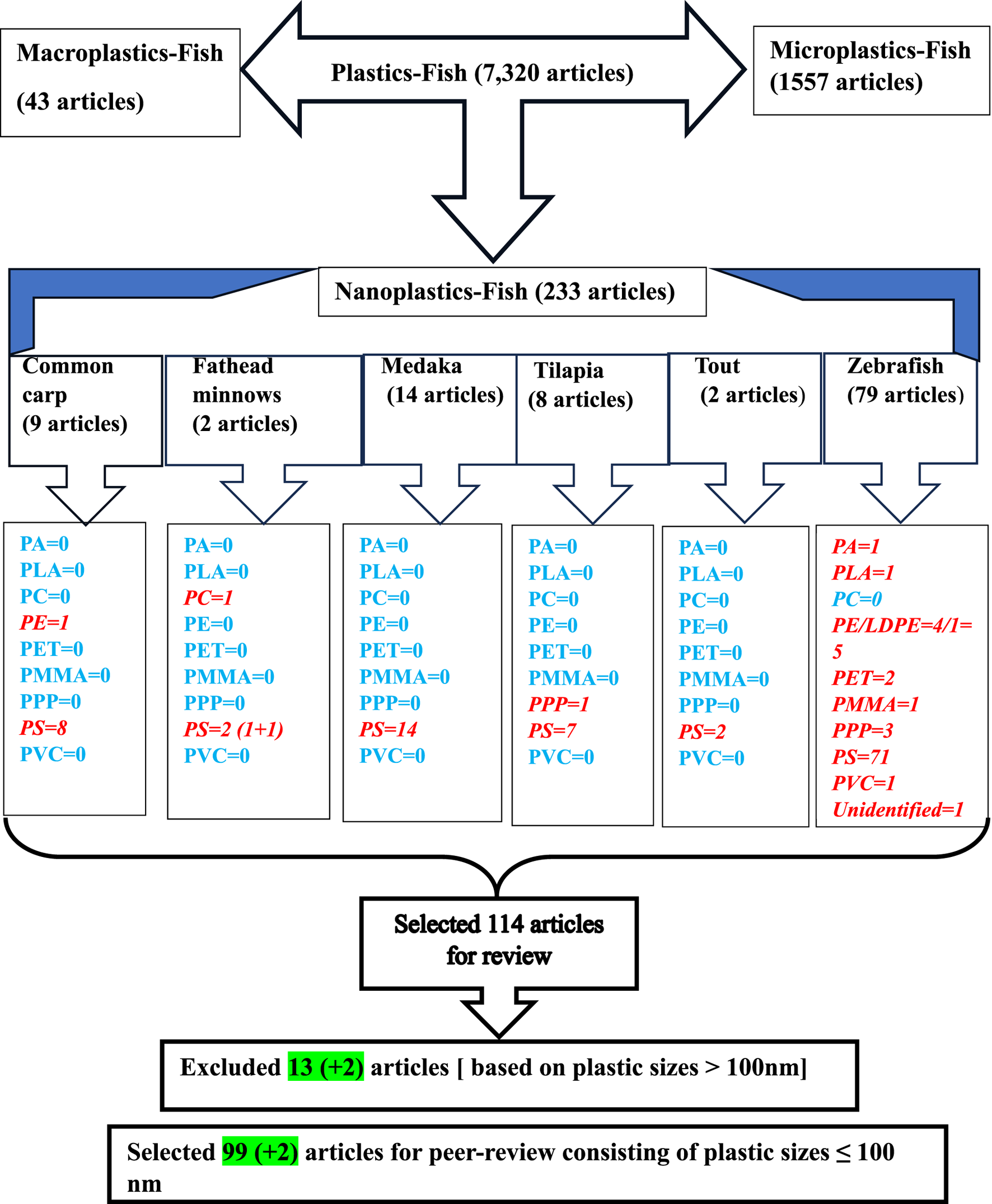

The global concern about plastics has been amplified due to their widespread contamination in the environment and their ability to cross biological barriers in living organisms. However, our understanding of their bioaccumulation, toxicity, and interaction with other environmental pollutants remains limited. Plastics are classified into three categories: macro-(MAP > 5 mm), micro-(MIP, <5 mm), and nanoplastics (NAP≤ 100 nm). Among these, NAPs have superior sorption capacity, a large surface area, and a greater ability to release co-contaminants into tissues, resulting in more complex and harmful effects compared to MAPs and MIPs. To assess the toxic effects of NAPs, particularly their genotoxicity in fish, we carried out a bibliographic search in PubMed using the search terms “nanoplastics” and “fish,” which yielded 233 articles. These studies focused on various polymers including polyamide (PA), polycarbonate (PC), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), polypropylene (PPP), polystyrene (PS), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC). We further refined our search by including fish species such as common carp, fathead minnows, medaka, tilapia, trout, and zebrafish and selected 114 articles for review. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge on the effects of NAPs on fishes, emphasizing their interaction with co-contaminants including metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, antibiotics, plastic additives, and endocrine disruptors found in the aquatic environments. Our findings indicate that among fish species, zebrafish (∼68%) is the most frequently studied, while PS (∼89%) is the most commonly encountered NAP in the aquatic ecosystems. Despite substantial experimental variability, our systematic review highlights that NAPs accumulate in various tissues of fish including the skin, muscle, gill, gut, liver, heart, gonads, and brain across all developmental stages, from embryos to adults. NAP exposure leads to significant adverse effects including increased oxidative stress, decreased locomotor and foraging activities, altered growth, immunity, lipid metabolism, and induced neurotoxicity. Furthermore, NAP exposure modulates estrogen–androgen–thyroid–steroidogenesis (EATS) pathways and shows potential intergenerational effects. Although the USEPA and EU are aware of the global impacts of plastic pollution, the prolonged persistence of plastics continues to pose a significant risk to both aquatic life and human health.

1 Introduction

Plastic particles are introduced into the environment through industrial activities, human practices, and inadequate waste management systems (Chen et al., 2017a; Gigault et al., 2018; Cox et al., 2019; Ebere et al., 2019; Strungaru et al., 2019; Kokalj et al., 2021). In recent decades, plastic pollution has emerged as the second largest environmental challenge, ranking among global threats such as ocean acidification, climate change, and ozone depletion (Amaral-Zettler et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2016; Vethaak and Leslie, 2016; Schymanski et al., 2018; Alimba and Faggio, 2019). The predominant source of plastic pollution stems from poor waste management practices including garbage dumping, improper disposal of waste, and runoff from industrial or agricultural activities (Leslie et al., 2017; Mahon et al., 2017; Triebskorn et al., 2019). The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated plastic contamination with the widespread use of personal protective equipment (e.g., face masks) and single-use packaging materials, contributing to a significant rise in plastic waste (Aragaw, 2020; Fadare and Okoffo, 2020; Yudell et al., 2020; Patricio Silva et al., 2021; Vanapalli et al., 2021; Afrin et al., 2022; Cho et al., 2022). Plastic waste once released into the environment does not decompose rapidly. Instead, it undergoes gradual decomposition, involving photolysis, oxidation, abrasion, hydrolysis, and biodegradation over an extended period of time (Sudhakar et al., 2007; Watters et al., 2010; Andrady, 2011; Maity and Pramanick, 2020). Larger plastic particles eventually break down into microplastics (MIPs; diameter ranging between 100 and 50,00,000 nm) and nanoplastics (NAPs, diameter ≤100 nm) through mechanisms such as wave action, mechanical wear and tear, photooxidation, and microbial degradation (O’Brine and Thompson, 2010; Lambert et al., 2013; Cozar et al., 2014; Gigault et al., 2016; Lambert and Wagner, 2016). NAPs are potentially more hazardous than MIPs (Rochman et al., 2013; Almeida et al., 2019; Domenech et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021; Yang and Wang, 2022; Yang and Wang, 2023; Huang et al., 2023; Huang et al., 2023). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has indicated that particles less than 150 µm (150,000 nm) in diameter may cross the intestinal mucosal barrier, while particles less than 1.5 µm (1,500 nm) in diameter can be transported into deeper tissues, including vital organs. Several types of MIPs (<50,00,000 nm), including polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polyoxymethylene, and polypropylene (PPP), have been found in various environmental compartments (de Sa et al., 2018) and have also been detected in the liver tissue of individuals with liver cirrhosis (Horvatits et al., 2022).

NAPs, often used as raw materials in products such as facial cleaners, scrubs, toothpaste, and other personal care items, are unintentional byproducts of plastic degradation and manufacturing processes (Enfrin et al., 2020; Kim, 2021; Kim et al., 2021). These particles, typically less than 1,000 nm in size, exhibit colloidal behavior and possess distinct chemical and physical characteristics compared to bulk plastics (Sharifi et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2017b; Pitt et al., 2018a; Lee et al., 2019). Due to their small size and high surface area, NAPs are highly efficient at both physical and chemical absorption of other environmental contaminants (Hartmann et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2019; Trevisan et al., 2019; Bhagat et al., 2020; Bhagat et al., 2021). Moreover, they are easily transferred through the food chain (Chae et al., 2018). Once absorbed into the body, NAPs can spread into the organs, including the brain and gonads, by overcoming the biological barriers (Lehner et al., 2019). Therefore, understanding their environmental fate, bioavailability, intake, and the potential effects on different organisms, is critical (Parenti et al., 2019; Lins et al., 2022) for humans. The persistence and degradation of macro- and MIPs contribute to the increase in NAPs in aquatic environments, including seas (Thompson et al., 2004; Cole et al., 2011; Harshvardhan and Jha, 2013; Earni-Cassola et al., 2019; Gigault et al., 2016), shorelines (Browne, 2011), estuaries (Saedi and Thompson, 2014), beach sediments (Imhof et al., 2013), lakes (Eriksen et al., 2013; Free et al., 2014), and freshwater ecosystems (Wagner et al., 2014; Vendel et al., 2017; Brandts et al., 2018; Pitt et al., 2018a; b; Parenti et al., 2019; Barria et al., 2020). These particles not only pose a direct toxicological threat but can also adsorb harmful chemicals, further enhancing their potential for inflicting biological harm (Jinhui et al., 2019; Campanale et al., 2020; Gonzalez-Fernandez et al., 2021). In aquatic organisms, such as zebrafish, NPs can be ingested and bio-fragmented within the body, potentially leading to toxicity and other physiological disruptions (Jovanovic, 2017; Khan and Ali, 2023; Barria et al., 2020; Duan et al, 2020).

Although PS is often used in risk assessments due to its commercial availability and varied sizes and surface charges, other plastics such as PE and PPP are also prevalent in environmental debris but have been less studied (Koelmans et al., 2019; de Ruijter et al., 2020). The current research gap necessitates a more comprehensive investigation of NAPs from various plastic types to assess their toxicity and ecological impacts. The aim of this systematic review is to evaluate the toxicological potential of NAPs in relation to plastic type, particle size, and their ability to adsorb hydrophobic pollutants, with a particular focus on the genotoxic effects in aquatic organisms such as fish. We hypothesize that NAPs upon crossing biological barriers and entering cells may trigger oxidative stress, induce DNA damage, and enhance the bioactivity of adsorbed contaminants. These processes may disrupt critical biological functions, including digestion, metabolism, neural activity and behavior, reproduction, and development, and potentially lead to intergenerational/transgenerational effects that could have significant implications on human health.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Literature search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to find journal articles that examine the toxic effects of NAPs on fish, with a special focus on the impacts at the molecular level. The electronic search was performed in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) until 29 February 2024, using the following search terms: “nanoplastics,” “fish,” and the different polymers of NAPs found in the aquatic environment (e.g., PA, PC, PE, PET, PMMA, PPP, PS, and PVC) (Table 1). The search also included the common names of the six fish species: common carp, fathead minnows, medaka, tilapia, trout, and zebrafish, previously followed in the studies by Dasmahapatra et al. (2023), Dasmahapatra et al. (2024). PubMed was selected as the primary database due to its reputation as a reliable and authoritative source for peer-reviewed scientific literature.

TABLE 1

| Serial number | Common name and molecular formula | IUPAC name | Chemical structure | Molecular weight (Da)/molar mass (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polyamide | Poly [imino (alkanedioyl)] |

|

10,000–50,000 Da |

| 2 | Polycarbonate (C16H18O5) | Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene |

|

290.32 |

| 3 | Polyethylene (C2H4) | Poly (methylene) |

|

28.05 |

| 4 | Polyethylene terephthalate (C10H12O6) | Ploy (ethyl benzene-1,4-dicarboxylate) |

|

228.19 |

| 5 | Polypropylene (C22H42O3) | Poly (1-methylethylene) |

|

354.56 |

| 6 | Polyethylene methacrylate (C5H10O2) | Poly (methyl 2-methylpropenoate) |

|

102.13 |

| 7 | Polystyrene (CH2CH(C6H5) | Poly (1-phenylethylene) |

|

2.01 |

| 8 | Polyvinyl chloride (C2H3Cl) | Poly (1-chloroethylene) |

|

62.49 |

Chemical structures of plastic polymers followed in this review.

LDPE = Low-density polyethylene; PA = polyamide; PC = polycarbonate; PE = polyethylene, PET = polyethylene terephthalate; PMMA = polyethylene methacrylate; PPP = polypropylene, PS = polystyrene; PVC = polyvinyl chloride. In two articles, part of the studies used plastic sizes ≤ 100 nm, and part of the studies used plastic sizes ≥ 100 nm. For this reason, these articles are mentioned in the exclusion as well as in the inclusion boxes.

For this review, we focused primarily on bony fish, with the selected species serving as representative examples of the class Osteichthyes (Figure 1). The term carp was used to refer collectively to several species, including common carp (Cyprinus carpio), grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella), silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) and tooth carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis) (Estrela et al., 2021; Guimaraes et al., 2021; Hamed et al., 2022; Liu S. et al., 2022; Wu et al., 2022; Zhang X. et al., 2022; Saemi-Komsari et al., 2023; Li Z. et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024a). Similarly, the term medaka encompassed Chinese rice fish (Oryzias sinensis), Hainan medaka (Oryzias curvinotus), Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes), and marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) (Chae et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024 YT.; He et al., 2022; Chen Y. et al., 2023; Gao D. et al., 2023; Li X. et al., 2023; Wang F. et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023a; Zhou et al., 2023b; Li X. et al., 2024). The term tilapia was used to refer to various species such as red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), and Mozambique tilapia (O. mossambicus) (Ding et al., 2018; Pang et al., 2021; Hao et al., 2023; Wang W. et al., 2023; Zheng and Wang, 2024; Zheng et al., 2024).

FIGURE 1

Flow chart of the literature search in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed).

The search yielded 114 peer-reviewed articles that highlight potential developmental, reproductive, neurological, immunological, and behavioral disorders in fish exposed to NAPs (Figure 1; Tables 2–9). A comprehensive summary of the findings has been compiled in Supplementary Table S1, which has been deposited in a public repository [Figshare (https://figshare.com) for reference and future update, if necessary.

TABLE 2

| Serial number | Authors | Polymer | Fish/stage of Development | Sizes | Concentration /dose |

Duration | Mode of exposure /additives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aliakbarzadeh et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 20-80 nm (average 57.5 nm) | 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 µg/L | 45 days | Waterborne/4- nonylphenol (1µg/L) |

| 2 | Barreto et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 60 nm | 0.015, 1.5, and 150 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne/SIM (0.015-150 µg/L) |

| 3 | Barreto et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 44 nm | 0.015, 1.5 mg/L | 96-120 hpf | Waterborne/DPH (0.01 and 10 mg/L) |

| 4 | Bashirova et al., (2023) | PET | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos (6 and 72 hpf) | Hydrodynamic diameter 70±5 nm | to 5, 10, 50, 100, 200 mg/L | Until 96- 120 hpf | Waterborne |

| 5 | Bhagat et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50 nm | 1 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne/ nAL2O3(1 mg/L) and nCeO3 (1 mg/L) |

| 6 | Brun et al., (2019) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (72 hpf) | 25 nm | 20 mg/L | Until 120 hpf | Waterborne |

| 7 | Chackal et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 100 nm | 2.5 and 25 µg/L | Until 7 dpf | Waterborne/BDE-47 (10 ng/L) |

| 8 | Chae et al., (2018) | PS | Chinese rice fish (Oryzias sinensis)/ adults (F0) and larvae (F1) | 60.39, 57.45, 57.29 nm | 5 mg/L | Adults (F0) exposed for 7 days; larvae (F1) exposed for 24 h | Waterborne |

| 9 | Chen et al., (2017a) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 47 and 41000 nm | 1 mg/L | 120 h | Waterborne /EE2 (2 and 20 µg/L) |

| 10 | Chen et al., (2017b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ adults (6 months old) | 47 nm | 1 mg/L | 3 days | Waterborne/BPA (0.78 µg/L) |

| 11 | Chen et al., (2022) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) /embryos | 50, 500, and 6000 nm | 106 particles/L | 19 days | Waterborne |

| 12 | Chen et al., (2023a) | PS-NH2 and PS-COOH | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) /embryos | 80 nm | 10 µg/L | 10 days with additional 10 days depuration | Waterborne (regular or acidified sea water) |

| 13 | Chen et al., (2023b) | PS, UV-PS, O3-PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos (8 hpf) | 80 nm | 0.5 and 5 mg/L | Until 120 hpf | Waterborne/ penicillin (1 and 10 µg/L) |

| 14 | Chen et al., (2023c) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50 nm | 0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/L | Until 120 hpf; evaluated on 5th, 7th, and 12th day | Waterborne/ Sodium nitroprusside (0.1,1, 10, 20, 30 and 40 µM) |

| 15 | Chen et al., (2024) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos (8hpf) | 80, 200, 500 nm | 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/L | 120 hpf, depurate 10 days | Waterborne |

| 16 | Cheng et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50, 100 nm and micro-PS | 0.1, 0.5, 2 and 10 mg/L | 120 hpf | Waterborne |

| 17 | Clark et al., (2023a) | PS-Pd | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)/juvenile | 200 nm | 10 mg/kg food | 3 and 7 days; depurated 7 days | Dietary |

| 18 | Clark et al., (2023b) | PS | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)/juvenile | 35±8 nm | 5.9 µg/g food | 3,7,14 days | Dietary |

| 19 | Dai et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 20 nm | 2, 5, and 8 mg/L | 22, 46, and 72 hpf | Waterborne |

| 20 | Deng et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 nm | 500 ng/mL | 28 days | Waterborne |

| 21 | De Souza Teodoro et al., (2024) | PET | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 68.06-955 nm and 1305000-2032000 nm | 0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L | 6 days | Waterborne |

| 22 | Ding et al., (2018) | PS | Red Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/juveniles | 100 nm | 1, 10, 100 µg/L | 14 days | Waterborne |

| 23 | Ding et al., (2020) | PS | Red Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/juveniles | 300, 5000, 7000-9000 nm | 100 µg/L | 6 and 14 days | Waterborne |

| 24 | Du et al., (2024) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 50-100 nm | 1000 µg/L | 21 days | Waterborne/dietary exposure to high fat diet (24% crude fat) |

| 25 | Duan et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos (4 hpf) | 50 nm | 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg/L | 72 h | Waterborne |

| 26a | Elizalde-Velazquez et al., (2020) | PS | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)/ adult (males) | 50 nm | 5 µg/L (0.1 ml injected volume) | 48 h | IP |

| 26b | Elizalde-Velazquez et al., (2020) | PS | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)/ adult (males) | 50 nm | 5 µg/L | 48 h | Trophic transfer (fed with daphnia which were consumed PS-exposed green algae) |

| 27 | Estrela et al., (2021) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)/juveniles | 23.03±0.266 nm | 760 µg/L | 72 h | Waterborne/ZnO2 (760 µg/L) |

| 28 | Feng et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 100 nm | 100, 200, and 400 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne |

| 29 | Gao et al., (2023a) | PS | Hainan medaka (Oryzias curvinotus) | 80 nm | 200 µg/L | 7 days | Waterborne/F53B (500 µg/L) |

| 30 | Gao et al., (2023b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (3 hpf) | 80 nm | 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 µg/L | 96 hpf | Waterborne/APAP (2-8 mM) |

| 31 | Geum and Yeo, (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50 nm | 5 mg/L | 4,8,12,24,32, 48, 72 hpf | Waterborne/PHE (0.5 and 1 mg/L and mucin from jelly fish (50 µg/L) |

| 32a | Greven et al., (2016) | PC | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)/ neutrophils of adults | 158.7 nm | 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 100 µg/mL | 2h | In vitro |

| 32b | Greven et al., (2016) | PS | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas)/ neutrophils of adults | 41 nm | 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 100 µg/mL | 1-2 h | In vitro |

| 33 | Guimaraes et al., (2021) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon Idella)/juveniles | 23.03±0.266 nm (20-26 nm) | 0.04 ng/L, 34 ng/L, and 34 µg/L | 20 days | Waterborne |

| 34 | Habumugisha et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (males) | 50 nm | 5, 10, 15 mg/L | 30 days; depurated 16 days; evaluated; evaluated on 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46 days. | Waterborne |

| 35 | Hamed et al., (2022) | PE | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio)/juvenile | 100 nm and > 100 nm | 100 mg/L | 15 days | Waterborne |

| 36 | Hao et al., (2023) | PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/ juveniles | 86 and 185 nm | 1 mg/L | 21 days, depurated 7 days | Waterborne |

| 37 | He et al., (2021). | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (males and females) | 46 and 5800 nm | 2 mg/L | 21 days | Waterborne /TPhP (0.08, 0.5, 0.7, 1, 1.2, 1.5 mg/L) |

| 38 | He et al., (2022) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma)/adults | 100 nm | 3.45 mg/g | 30 days [F0]. [F1 offspring were evaluated 60 dph without any exposure) |

Dietary [F0]/ /SMG (94.62 mg/g) |

| 39 | Kang et al., (2021) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma)/larvae (7 dph) | 50 nm and 45 µm (45,000 nm) | 10 µg/mL and 2.5 µg/mL | 24 h (10µg/L). 1, 7, 14, and 120 days (2.5 µg/mL) |

Waterborne |

| 40 | Kantha et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ embryos | 25 nm | 10, 25, and 50 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne |

| 41 | Khan and Ali (2023) | PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ adults | 10-100 µm (10,000-100,000 nm) | Unknown | 24h | Waterborne |

| 42 | Lee et al., (2019) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ embryos | 50, 200, 500 nm | 0.1 mg/L | 6, 24, 96 h | Waterborne |

| 43 | Lee et al., (2022) | PPP | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ embryos (24 hpf and 72 hpf) | 562.15±118.47 nm | 50 mg/L | 24 h | Waterborne |

| 44 | Li et al., (2023a) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ adults | 80 nm | 15 and 150 mg/L | 28 days | Waterborne/vitamin D (280 and 2800 IU/kg) |

| 45 | Li et al., (2023b) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) /juveniles (2 months old) | 100 nm | 1 mg/L | 30 days | Waterborne/SMX (100µg/L) |

| 46 | Li et al., (2023c) | PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 70 and 13500 nm | 20 mg/L | 21 days | Waterborne/PEMIP (20 mg/L) |

| 47 | Li et al., (2024a) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)/juveniles | 80 nm | 10, 100, 1000 µg/L | 8 days; coexposure 3 days with 5 days preexposure with PS | Waterborne/Aeromonas hydrophilia (2X107CFU/mL) |

| 48 | Li et al., (2024b) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) / larvae (3 dph) | 70, 500 and 2000 nm | 20, 200, and 2000 /L | 90 days | Trophic transfer (fed to rotifers and the rotifers were fed by the fish) |

| 49 | Lin et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (males and females) | 70 nm | 2 mg/L | 21 days | Waterborne/DES (1,10, 100 ng/L) |

| 50 | Ling et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (males and females) | 70 nm | 100µg/L | 90 days | Waterborne /MCLR (0.9, 4.5, and 22.5 µg/L) |

| 51 | Liu et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 100 nm | 10 µg/L | Until 120 hpf | Waterborne/BMDBM (1,10, and 100 µg/L) |

| 52 | Liu et al., (2022a) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)/juveniles | 80 nm | 20, 200, 2000 µg/L | 7 days | Waterborne/TC (5000 µg/L) |

| 53 | Liu et al., (2022b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 100 nm | 10 µg/L | 144h and depurated 72 h | Waterborne/AV0 (10 µg/L) |

| 54a | Manuel et al., (2022) | PMMA | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 32 nm | 0.001, 0.01,0.1, 1, 10, 100 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne |

| 54b | Manuel et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 22 nm | 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 100 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne |

| 55 | Martin et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 30 and 100 nm | 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne |

| 56 | Martinez-Alvarez et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50, 500, and 4500 nm | 0.069 µg/L- 50.1 mg/L | 120 h | Waterborne /B(a)P (0.1-10 mg/L) |

| 57 | Martin-Folgar et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 30 nm | 0.1, 0.5 and 3 mg/L | 120 hpf | Waterborne |

| 58a | Monikh et al., (2022) | PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) |

50 nm | 3X1010 particles/L (0.000 25 mg/L) | 24 h | Waterborne |

| 58b | Monikh et al., (2022) | PPP | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) |

50 nm | 3X1010 particles/L (.00022 mg/L) | 24h | Waterborne |

| 58c | Monikh et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) |

200 and 600 nm | 3X1010 particles/L (PS 200 nm =0.13 mg/L; PS 600=3.5 mg/L) | 24 h | Waterborne/B(a)P (10 µg/L) |

| 58d | Monikh et al., (2022) | PVC | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) |

200 nm | 3X1010 particle/L (0.17 mg/L) | 24 h | Waterborne/B(a)P (10 µg/L) |

| 59 | Pang et al., (2021) | PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus)/larvae | 100 nm | 20 mg/L | 7 days and depurated 7 days | Waterborne |

| 60 | Parenti et al., (2019) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (72 hpf) | 500 nm | 1 mg/L | 2 days (until 120 hpf) | Waterborne |

| 61 | Park and Kim (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (1 dpf) | 400 and 1000 nm | 7.5-60 mg/L | 3 days | Waterborne |

| 62 | Pedersen et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) | 50, 200 nm | 10, 100, 1000, 10,000 µg/L | Until 120 hpf | Waterborne |

| 63 | Pitt et al., (2018a) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) | 51 nm | 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L | 120 h | Waterborne |

| 64 | Pitt et al., (2018b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 42 nm | 1 mg/g | 7 days | Dietary |

| 65 | Saemi-Komsari et al., (2023) | PS | Tooth Carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis)/ adults | 100-300 nm (average 185 nm) | 1, 5,10,25, 100, 200 mg/L and 1.1. 0.1, 1, 5 mg/L | 96h (waterborne)/3, 14, 28 days (dietary exposure) | Waterborne and dietary/ TCS (0.5 mg/kg) |

| 66 | Santos et al., (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 44 nm | 0.015, 1.5,15, and 150 mg/L | 96-120 hpf | Waterborne/PHN (0.2, 2, and 20 mg/L) |

| 67 | Santos et al., (2024) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 23.03 ±0.266 nm | 0.04 ng/l, 34 ng/L and 34 µg/L | 144 hpf | Waterborne |

| 68 | Sarasamma et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 70 nm | 0.5, 1.5 and 5 mg/L | 7 days, 30 days, 7 weeks |

Waterborne |

| 69 | Sendra et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /larvae (120 hpf) | 50, 1000, 50,000 nm | 10 mg/L | 7 days | Waterborne |

| 70 | Senol et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 134±2.9 nm | 25 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne at 28°, 29°, and 30° C |

| 71 | Sokmen et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 20 nm | 3 nL of 270 mg/L | 120 h | Injected to fertilized eggs |

| 72 | Sulukan et al., (2022a) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (4 hpf) | 20 nm | 3 nL of 270 mg/L | Grown 6 months and evaluated F1 offspring | Injected to fertilized eggs |

| 73 | Sulukan et al., (2022b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 nm | 25 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne at 28°, 29°, and 30° C |

| 74 | Suman et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 500 nm | 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L | 6 days | Waterborne |

| 75 | Sun et al., (2021) | PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) | Hydrodynamic size 191.10 ±3.13 nm | 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000 µg/mL | 48-96 h | Waterborne |

| 76a | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023)) | LDPE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (4 hpf) | 164-91 nm | 0.001, 0.01,0.1,1, and 10 mg/L | 4h-96 h | Waterborne |

| 76b | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023)) | PLA | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (4 hpf) | 122-712 nm | 0.001, 0.01,0.1,1, and 10 mg/L | 4h-96 h | Waterborne |

| 76c | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023)) | PPP | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (4 hpf) | 164-220 nm | 0.001, 0.01,0.1,1, and 10 mg/L | 4h-96 h | Waterborne |

| 76d | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023)) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (4 hpf) | 91-825 nm | 0.001, 0.01,0.1,1, and 10 mg/L | 4h-96 h | Waterborne |

| 77 | Teng et al., (2022a) | PS-NH2 PS-COOH |

Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 30-51 nm | 30 and 50 mg/L | 120 h | Waterborne |

| 78 | Teng et al., (2022b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/juveniles and adults | 44 nm | 1, 10, and 100 µg/L | 30 and 60 days | Waterborne |

| 79 | Teng et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/ adults | 80 nm | 15 and 150 µg/L | 21 days | Waterborne/ vit D (280-2800 IU/kg, via food) |

| 80 | Trevisan et al., (2019) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) /embryos (6 hpf) | 44 nm | 1.1. 1, 10 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne/PAH (5.07-25.36 µg/L) |

| 81 | Trevisan et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 44 nm | 1 mg/L | 7 days | Waterborne/PAH (5.073 ng/mL) |

| 82 | Van Pomeren et al., (2017) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 25, 50, 250,700 nm | 5-50 mg/L | 48 h | Waterborne |

| 83 | Varshney et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 15 nm | 50 mg/L | 96 h | Waterborne/ p, p’-DDE (100 µg/L) |

| 84 | Wang et al, (2022) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 80 nm | 0.05, 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L | 120 hpf | Waterborne/BDE-47 (0.1 mg/L) |

| 85 | Wang et al., (2023a) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) / adults | 100 nm | 5 mg/ g food | 30 days | Feeding/ SMG (0.5 and 5 mg/g food) |

| 86 | Wang et al., (2023b) | PS | Tilapia/juveniles | 100, 500, and 5,000 nm | 1, 10, 100 µg/L | 7 days | Waterborne |

| 87 | Wang et al, (2023c) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 80 nm | 0.05, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L | 12-120hpf | Waterborne/BDE-47 (0.1 and 10 mg/L) |

| 88 | Wang et al., (2023d) | PS-COOH | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 50 nm | 1, 5, and 10 mg/L | 144 h | Waterborne |

| 89 | Wang et al., (2023e) | Nanoplastics (NAPs) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (120 dpf) | 100 nm | 1 mg/L | 45 days | Waterborne/BPAF (200 µg/L) |

| 90 | Wu et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 70 nm | 100 µg/L | 45 days; F1 embryos were evaluated without any further exposure | Waterborne/MCLR (0.9, 4.5, and 22.5 µg/L) |

| 91 | Wu et al., (2022) | PS | Carp /adult | 50, 100, and 400 nm | 1000 µg/L | 28 days | Waterborne |

| 92 | Wu et al., (2023) | PPP | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/juveniles | 100 nm and 100 µm (100,000 nm) | 1, 10, and 100 mg/L | 21 days | Waterborne |

| 93 | Xie et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 80 and 8000 nm | 1 mg/L (80 nm); 10 µg/L (8000 nm) | 21 days | Waterborne |

| 94 | Yang et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 and 20,000 nm | 100 and 1000 µg/L | 4 days, depurate 3 days | Waterborne |

| 95 | Ye et al., (2024) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 50 nm | 1 mg/L | 21 days | Waterborne/ homosolate (0.0262-262 µg/L) |

| 96 | Yu et al., (2022a) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 nm | 20 and 200 µg/L | 3 weeks | Waterbone/lead (50 µg/L) |

| 97 | Yu et al., (2022b) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 40-54 nm; 394-407 nm; 4,000-8,000 nm; 45,000-85,000 nm; 158,000-234,000 nm | 60-338 µg/L | 30 days | Waterborne/tetracycline (100 µg/L) |

| 98 | Yu et al., (2023) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) / embryos (6hpf) | 50 nm | 55 µg/L | 21 days | Waterborne /BPA (100 µg/L) |

| 99a | Zhang et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 70 ± 9.21 nm | Injected 0.52 nL of 1000, 3000, and 5000 mg/L | Hatched larvae depurate 4 weeks | Injected to eggs |

| 99b | Zhang et al., (2020) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 70 ± 9.21 nm | 0.5 and 5 mg/L | Until the hatching, depurate 4 weeks | Waterborne |

| 100 | Zhang et al., (2021) | PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | 100 nm | 5 mg/g food | 30 days | Feeding/SMG 0.5, and 5 mg/g |

| 101a | Zhang et al., (2022b) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)/ embryos (12hpf) | 80 and 8000 nm | 5, 15, and 45 µg/L | 2-8 h | Waterborne |

| 101b | Zhang et al., (2022b) | PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella)/ larvae (24 hph) | 50 and 5000 nm (green fluorescence). 1000 and 5000 (red fluorescence |

10 µg/L | 12-96 h | Waterborne |

| 102 | Zhang et al., (2022c) | Polyamide (PA) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 5-50 µm (5,000-50,000 nm) | 1, 10, and 20 mg/L | 2hpf-10dpf | Waterborne |

| 103 | Zhang et al., (2023) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 nm | 1 mg/L | 30 days | Waterborne/arsenic (200 µg/L) |

| 104 | Zhang et al., (2024a) | PS | Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix)/ adults | 80 nm | 10 and 1000 µg/L | 96 h | Waterborne/Microcystin-LR (1µg/L) |

| 105 | Zhang et al., (2024b) | PS-plain, PS-COOH, PS-NH2 | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) /adults (10-12 months old) | Z-average of plain PS =244.0±11.6 nm, PS-COOH =294.7±8.6 nm, and PS-NH2 = 277.0±15.9 nm | 3.62 mg/g of food | 30 days, depurated for 21 days | Feeding/SMZ (4.62 mg/g food) |

| 106 | Zhang et al., (2024c) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 100 nm | 1 ng/L | 30 days | Waterborne/arsenic (1 mg/L) |

| 107 | Zhao et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults (males and females) | 54.5 ±2.8 nm | 10 mg/L | 120 days; evaluated F0 and F1 larvae without further exposure | Waterborne/TDCIPP (0.47, 2.64, or 12.78 µg/L) |

| 108 | Zheng and Wang (2024) | PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/larvae | 80 nm and 20 µm (20,000 nm) | 100 µg/L | 28 days | Waterborne |

| 109 | Zheng et al., (2024) | PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus)/larvae | 80, 2000, 20,000 nm | 100 µg/L | 28 days | Waterborne |

| 110 | Zhou et al., (2023a) | PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes)/ adults | 100 nm | 10, 104, 106 particles/ L (1.79589 X1013 particles/10 mg concentration) | 3 months | Waterborne |

| 111 | Zhou et al., (2023b) | PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes)/ larvae (9 dph) and adults (60 dph) | 100 nm | Larvae= (1014 items/L or 55 mg/L). Adults= (10 items/L or 5.5X10-12 mg/L; 104/L or 5.5X10-9 mg/L; 106 items/L or 5.5X10-7 mg/L) |

Larvae 48 h. Adults 3 months. |

Waterborne |

| 112 | Zhou et al., (2023c) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/embryos | 100, 500, 1000 nm | 10 mg/L or 2.2 X1012 particles/L for 100 nm;1.76X1010 particles/L for 500 nm; 2.2X109 particle/L for 1000 nm. | 5 days | Waterborne |

| 113 | Zhou et al., (2023d) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 50 ±3 nm | 1 mg/L | 4 weeks | Waterborne |

| 114. | Zuo et al., (2021) | PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio)/adults | 70 nm | 100µg/L | 21 days; F1 (120 hpf) were evaluated without further exposure | Waterborne/MCLR (0.9, 4.5, and 22.5 µg/L) |

List of authors who studied the effects of NAPs on fish.

Blocks highlighted in yellow are coexposure studies. Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) used two different methods ofexposure (injection and trophic transfer) of PS and mentioned inone article. Greven et al. (2016) studied the effects of PC and PS in one article. Manuel et al. (2022) reported the effects of PMMA and PS inzebrafish in one article. Monikh et al. (2022) reported the effects of PE, PPP, PS, and PVC in one article. Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) reported the effects of PLA, PP, PS, and LDPE in one article. Zhang et al. (2020) used two different methods of exposure (injection and waterborne) of PS and mentioned in one article. Zhang C. et al. (2022) used two different life stages of zebrafish(embryo larvae) for PS exposure and described in one article. Wang L. et al. (2023) did not mention the type of NAPs used inthe experiment.AVO = avobenzone; BDE-47 = Polybrominated diphenyl ether: BMDBM = methoxydibenzoylmethane; BPA = bisphenol A; EE2 =17 α-ethynyl estradiol; IP = intraperitoneal injection; LDPE = lowdensitypolyethylene; MCLR = microcystin-LR; PA = polyamide; PC = polycarbonate; PE = polyethylene; PET = polyethyleneterephthalate; PHN = phenmedipham; PLA = polylactic acid; PMMA = polymethylmethacrylate; PPP = polypropylene; PS =polystyrene; SIM = simvastatin; SMZ = sulfamethazine; TDCIPP = tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate; TPhP =triphenyl phosphate; TC = tetracycline; TCS = triclosan.

TABLE 3

| Fish | Polymer (name) | Sizes (mode of exposure) | Developmental stages | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zebrafish | PA | ∼32, 500 nm | Embryos (2 hpf) | Zhang et al. (2022c) |

| 2a | Fathead minnows | PC | 158.7 nm (in vitro) | Adults (neutrophils) | Greven et al. (2016) |

| 2b | Fathead minnows | PC | 41 nm (in vitro) | Adults (neutrophils) | Greven et al. (2016) |

| 3 | Zebrafish | PE | 191.10 ± 3.13 nm | Embryos (6 hpf) | Sun et al. (2021) |

| 4 | Zebrafish | PE | 10,000–100,000 nm | Adults (8–10 months old) | Khan and Ali (2023) |

| 5 | Zebrafish | PPP | 562.15 ± 118.47 nm | Embryos (24 hpf and 72 hpf) | Lee et al. (2022) |

| 6a | Zebrafish | PPP | 164–220 nm | Embryos (4 hpf | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| 6b | Zebrafish | PLA | 122–712 nm | Embryos (4 hpf | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| 7 | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | 244–277 nm | Adult | Zhang et al. (2024b) |

| 8 | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | PS | ∼200 nm | Juveniles | Clark et al. (2023a) |

| 9 | Red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | 300, 500, and 7,000–9,000 nm | Juveniles | Ding et al. (2020) |

| 10 | Zebrafish | PS | 500 nm | Embryos (72 hpf) | Parenti et al. (2019) |

| 11a | Zebrafish | PS | 200 and 600 nm | Embryos (6 hpf) | Monikh et al. (2022) |

| 11b | Zebrafish | PVC | 200 nm | Embryos | Monikh et al. (2022) |

| 12 | Zebrafish | PS | 400–1,000 nm | Embryos (1 dpf) | Park and Kim (2022) |

| 13 | Zebrafish | PS | 500 nm | Embryos | Suman et al. (2023) |

| 14 | Zebrafish | PS | 134 ± 2.9 nm | Adult | Senol et al. (2023) |

| 15 | Zebrafish | Nanoplastics | 100 nm | Adults (120 dpf) | Wang et al. (2023e) |

Articles excluded from reviews (based on the size and the mode of exposure).

Greven et al. (2016) studied the effects of PC and PS on RBCs of adult fathead minnows in vitro. Monikh et al. (2022) studied the effects of PS and PVC on zebrafish and included in one article. Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) described the effects of PPP and PLA on zebrafish embryos in one article; Wang L. et al. (2023) did not mention the types of NAPs used in this study.

TABLE 4

| Fish | Polymer | MIP (size) | NAP (size) | Developmental stage | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | PE | >5 mm->100 nm | <100 nm | Juvenile | Hamed et al. (2022) |

| 2 | Zebrafish | PE | 13.5 µm (13,500 nm) | 70 nm | Adult | Li et al. (2023c) |

| 3 | Zebrafish | PET | >100 nm −2032 µm (20,32,000 nm) | 68.06–100 nm | Embryos | de Souza Toedoro et al. (2024) |

| 4 | Carp | PS | 400 nm | 50 and 100 nm | Adult | Wu et al. (2022) |

| 5a | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | PS | 8 µm (8,000 nm) | 80 nm | Embryos | Zhang et al. (2022b) |

| 5b | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | PS | 5 µm (8,000 nm) | 50 nm | Larvae | Zhang et al. (2022b) |

| 6 | Tooth carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis) | PS | 300 nm | 100 nm | Adult | Saemi-Komsari et al. (2023) |

| 7 | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | 500 and 6,000 nm | 50 nm | Embryos | Chen et al. (2022) |

| 8 | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | 45 µm (45,000 nm) | 50 nm | Larvae (7 dph) | Kang et al. (2021) |

| 9 | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | 500 nm and 2 µm (2,000 nm) | 70 nm | Larvae (3 dph) | Li et al. (2024b) |

| 10 | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PPP | 100 µm (100,000 nm) | 100 nm | Juveniles | Wu et al. (2023) |

| 11 | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | 2 and 20 µm (2,000 and 20,000 nm) | 80 nm | Larvae | Zheng et al. (2024) |

| 12 | Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | 185 nm | 100 nm | Juveniles | Hao et al. (2023) |

| 13 | Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | 500 and 5,000 nm | 100 nm | Juveniles | Wang et al. (2023b) |

| 14 | Zebrafish | PS | 41 µm (41,000 nm) | 47 nm | Embryos | Chen et al. (2017a) |

| 15 | Zebrafish | PS | 250 and 700 nm | 25 and 50 nm | Embryos | Van Pomeren et al. (2017) |

| 16 | Zebrafish | PS | 200 and 500 nm | 50 nm | Embryos | Lee et al. (2019) |

| 17 | Zebrafish | PS | 200 nm | 50 nm | Embryos | Pedersen et al. (2020) |

| 18 | Zebrafish | PS | 500 and 4,500 nm | 50 nm | Embryos | Martinez-Alvarez et al. (2022) |

| 19 | Zebrafish | PS | 500 and 1,000 nm | 100 nm | Embryos | Zhou et al. (2023c) |

| 20 | Zebrafish | PS | 200 and 500 nm | 80 nm | Embryos and larvae | Chen et al. (2024) |

| 21 | Zebrafish | PS | 1,000 nm and 50 µm | 50 nm | Larvae | Sendra et al. (2021) |

| 22 | Zebrafish | PS | 5,800 nm | 46 nm | Adults (male and female) | He et al. (2021) |

| 23 | Zebrafish | PS | 8,000 nm | 80 nm | Adults | Xie et al. (2021) |

| 24 | Zebrafish | PS | 394–407 nm, 4–8 μm, (4,000–8,000 nm), 45–85 µm (45,000–85,000 nm), and 158–234 µm (158,000–234,000 nm) | 40–54 nm | Adults | Yu et al. (2022b) |

| 25 | Zebrafish | PS | 20 µm (20,000 nm) | 100 nm | Adults | Yang et al. (2023) |

| 26a | Zebrafish | PS | 122, 220, 712, and 825 nm | 91 nm | Embryos (4 hpf–96 hpf) | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| 26b | Zebrafish | LDPE | 164,106, 342, and 122 nm | 91 nm | Embryos (4 hpf–96 hpf) | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

Articles included both MIPs and NAPs during investigations.

MIP , microplastics (diameter of the polymer is > 100 nm); NAPs , nanoplastics (diameter of the polymer is ≤100 nm); Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) measured the diameter of the plastic every day during the exposure period (day 0, day 1, day 2, day 3, and day 4).

TABLE 5

| Name of the plastics | Fish | Developmental stages | Nanoplastic size/diameter | Mode of exposure/duration | Accumulated (tissues/organs) or studied organs | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | Juveniles | 100 nm | Waterborne-(15 mg/L)-15 days) | Brain and eye | Hamed et al. (2022) |

| LDPE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (4 hpf) | 91 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 10 mg/L), 96 hpf | Vitelline membrane | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (3 × 1010 particles/L or 0.00025 mg/L), 24 h | Whole embryo | Monikh et al. (2022) |

| PE | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (3 months) | 70 nm | Waterborne (20 mg/L), 21 days | Gill/gut/intestine /liver | Li et al. (2023c) |

| PET | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 and 72 hpf) | 70 ± 5 nm | Waterborne (5, 10, 50, 100, and 200 mg/L), until 96–120 hpf | Liver, intestine, and kidney | Bashirova et al. (2023) |

| PET | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 68.06 nm and above | Waterborne (0.5, 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/L), 6 days | Chorion surface | de Souza Toedoro et al. (2024) |

| PMMA | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 32 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 mg/L), 96 h | Whole embryo | Manuel et al. (2022) |

| PPP | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Juveniles (10 ± 1 g; length 13 ± 1 cm) | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mg/L), 21 days | Liver | Wu et al. (2023) |

| PPP | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (3 × 1010 particles/L or 0.000022 mg/L), 24 h | Whole embryos | Monikh et al. (2022) |

| PS | Carp | Adults | 50 and 100 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 28 days | Heart | Wu et al. (2022) |

| PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Embryos (12 hpf) | 50–80 nm | Waterborne (0.005–0.045 mg/L); 2,4, and 8 h | On the chorion | Zhang et al. (2022b) |

| PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | 23.03 ± 0.266 nm | Waterborne (0.76 mg/L), 72 h | Blood/liver/brain | Estrela et al. (2021) |

| PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | 20–26 nm | Waterborne (0.00000004–0.034 mg/L), 20 days | Liver/brain | Guimaraes et al. (2021) |

| PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | 80 nm | Waterborne, 0.02, 0.2, and 2 mg/L (7 days) | Liver and intestine | Liu et al. (2022a) |

| PS | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.01, 0.1, and 1 mg/L), 8 days | Gut/intestine | Li et al. (2024a) |

| PS | Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) | Adults | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.01 and 1 mg/L), 96 h | Gut/intestine/liver | Zhang et al. (2024a) |

| PS | Tooth carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis) | Adult | 100 nm | Waterborne (1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 200 mg/L), 96 h Diet (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 5 mg/kg), 3, 14, and 28 days |

Gut, gill, liver, muscle, and skin | Saemi-Komsari et al. (2023) |

| PS | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) | Adult males | 50 nm | IP-injected (0.1 mL of 0.005 mg/L), 48 h | Liver and head kidney | Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) |

| PS | Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) | Adult males | 50 nm | Trophic transfer (0.005 mg/L), 48 h | Liver and head kidney | Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) |

| PS | Chinese rice fish (Oryzias sinensis) | Adults and F1 larvae | 57.29–60.39 nm | Waterborne (5 mg/L); (adults 7 days; F1 larvae 24 h) | Yolk sac | Chae et al. (2018) |

| PS | Hainan medaka (Oryzias curvinotus) | Adults | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.2 mg/L), 7 days | Gills and intestine | Gao et al. (2023a) |

| PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Adults | 100 nm | 10, 104, and 106 particles/L (1.79589 × 1013 particles/10 mg concentration) | Gut | Zhou et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (10, 104, and 106 particles/L) or (5.5 × 10−12, 5.5 × 10−9, and 5.5 × 10−7 mg/L), 3 months | Gonads (ovary/testis) | Zhou et al. (2023a) |

| PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Larvae (9 dph) | 100 nm | Waterborne (1014 items/L or 55 mg/L), 48 h | Gut | Zhou et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | Adults (60 dph) | 100 nm | Waterborne (5.5 × 10−12 mg/L, 5.5 × 10−9 mg/L, and 5.5 × 10−7 mg/L), 90 days | Gut | Zhou et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) | Waterborne (106 particles/L), 19 days | Whole embryo | Chen et al. (2022) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Embryos | PS-NH2 (80 nm); PS-COOH (80 nm) | Waterborne (0.01 mg/L), 10 days (depurated for 10 days) | Gastrointestinal tract and intestinal villi | Chen et al. (2023a) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.055 mg/L), 21 days | Abdominal area/liver/heart | Yu et al. (2023) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Larvae (7 dph) | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.0025–0.01 mg/L); 1, 7, 14, and 120 dph | Gut | Kang et al. (2021) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Larvae (3 dph) | 70 nm | Trophic transfer (0.02, 0.2, and 2 mg/L), 90 days | Intestine/liver /muscle/gonad | Li et al. (2024b) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Juveniles (2 months) | 100 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 30 days | Intestine | Li et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (5 mg/g), 30 days | Gut/intestine | Zhang et al. (2021) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults | 100 nm | Dietary (3.45 mg/g), 30 days | Gut/liver of 60 dph F1 larvae | He et al. (2022) |

| PS | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults (4 months) | 100 nm | Dietary (5 mg/g), 30 days (depurated for 21 days) | Gut | Wang et al. (2023a) |

| PS | Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | Juvenile | 35 ± 8 nm | Dietary (0.0059 mg/g food); 3, 7, and 14 days | Hind intestine and liver | Clark et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Red tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Juveniles | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mg/L), 14 days | Gut, gills, liver, and brain | Ding et al. (2018) |

| PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Larvae | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 28 days | Gills | Zheng and Wang (2024) |

| PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Larvae | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 28 days | Gills | Zheng et al. (2024) |

| PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Larvae (4 weeks old) | 100 nm | Waterborne (20 mg/L), 7 days (depurated for 7 days) | Whole fish | Pang et al. (2021) |

| PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Juveniles | 86 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 21 days (depurated 7 days) | Gill, stomach, intestine, liver, and muscle | Hao et al. (2023) |

| PS | Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | Juveniles | 100 nm | Waterborne (1, 10, and 100 mg/L), 7 days | Gill, liver, intestine, and muscle | Wang et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (3 hpf) | 47 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 120 h | Whole embryo | Chen et al. (2017a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 25 and 50 nm | Waterborne (25 mg/L; 25 nm) (50 mg/L; 50 nm); 0–48 hpf, 24–72 hpf, and 72–120 hpf | Chorion (0 hpf); eye (72 hpf) | Van Pomeren et al. (2017) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 51 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L), 120 hpf | Yolk sac, GI tract, gall bladder, liver, pancreas, heart, and brain | Pitt et al. (2018a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (72 hpf) | 25 nm | Waterborne (20 mg/L), 72–120 hpf, 48 h | Intestine, pancreas, and gall bladder | Brun et al. (2019) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L); 6, 24, and 96 hpf | Whole body | Lee et al. (2019) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 44 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L), 96 hpf | Whole body | Trevisan et al. (2019) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (6 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L), 120 hpf | GI tract, eye, liver, and cranial region | Pedersen et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 20 nm | Microinjected to eggs (3 µL of 270 mg/L), 120 hpf | Brain | Sokmen et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 44 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 7 days | Yolk sac and brain | Trevisan et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 70 ± 9.21 nm | Microinjected to eggs (0.52 nL of 1,000, 3,000, and 5,000 mg/L), 4 weeks | Maximum in the yolk sac and followed by brain > eyes > gut > swim bladder (maximum accumulation in the trunk region | Zhang et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 70 ± 9.21 nm | Waterborne (0.5 and 5 mg/L), exposed until hatching and depurated for 4 weeks | Maximum accumulation in the brain and eyes | Zhang et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 60 nm | Waterborne (0.015, 1.5, and 150 mg/L, 96 h | Whole embryos | Barreto et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (2 hpf) | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.01 mg/L); 12 h (depurated 120 hpf) | Whole embryos | Liu et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne 1 mg/L (96 h) | Whole embryo | Bhagat et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.0025 and 0.025 mg/L) 7 days | Anterior part containing the yolk sac and digestive tract | Chackal et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 and 100 nm | Waterborne ((0.1, 0.5, 2 and 10 mg/L), 120 hpf | Intestine and areas of excretion | Cheng et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 100 nm | Waterborne (100, 200, and 400 mg/L), 96 h | Whole embryo | Feng et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne (5 mg/L), 4–96 hpf | Surface of the chorion and the embryos | Geum and Yeo, (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 25 nm | Waterborne (10, 25, and 50 mg/L), 96 hpf | Whole embryo | Kantha et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (2 hpf) | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.01 mg/L) (144 hpf, depurated for 3 days) | Whole embryo | Liu et al. (2022b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 22 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 100 mg/L), 96 hpf | Whole embryo | Manuel et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.000069, 0.00069, 0.069, 0.687, and 6.87 mg/L), 120 hpf | Chorion, eye, tail, and yolk sac | Martinez-Alvarez et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 44 nm | Waterborne (0.015, 0.15, 1.5, 15, and 150 mg/L), 96–120 hpf | Whole embryo | Santos et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (4 hpf) | 20 nm | Injected (3 nL of 270 mg/L); grown for 6 months; F1 embryos were evaluated | Whole embryo | Sulukan et al. (2022a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS-NH2 (50 nm fluorescent) PS-COOH (30 nm fluorescent) PS-NH2 (51 nm, unlabeled) (+ve charge) PS-COOH (50 nm unlabeled) (-ve charge) |

Waterborne (30 and 50 mg/L to labeled or unlabeled PS-NH2 or PS-COOH), 120 hpf | GI tract, pericardium, and brain | Teng et al. (2022a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.05 mg/L, 0.1 mg/L, 1 mg/L, 5 mg/L, and 10 mg/L) (120 hpf) | Surface of the chorion, brain, gills, mouth, trunk, heart, liver, and digestive tract | Wang et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 44 nm | Waterborne (0.015 and 1.5 mg/L), 96–120 h | Whole embryo | Barreto et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (8 hpf) | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.5 and 5 mg/L), 96 hpf | Yolk sac, eye, head, and nerve tubes | Chen et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/L), 5 days | Whole embryo | Chen et al. (2023c) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 20 nm | Waterborne (2, 5, and 8 mg/L); 22, 46, and 70 h | Whole embryo | Dai et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 50 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg/L); 4–72 h at 24°C, 27°C, and 30°C | Chorion, abdomen, circulatory system, intestinal tract, and excretory regions | Duan et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (3 hpf) | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.005, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, and 0.1 mg/L), 96 h | Whole embryo | Gao et al. (2023b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 30 and 100 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L), 96 h | Chorion, head, trunk, and in the yolk | Martin et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 30 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 0.5, and 3 mg/L), 120 hpf | Whole embryo | Martin-Folgar et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (4 hpf) | PS (91, nm) | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, and 10 mg/L), 96 hpf | Vitelline membrane | Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (2 hpf) | 15 nm | Waterborne (50 mg/L), 96 h | GI tract, pericardium, eye, and cranial regions | Varshney et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.05, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L), 120 hpf | Gills, GI, liver, and heart | Wang et al. (2023c) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (4 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (1, 5, and 10 mg/L), 144 hpf | Whole embryo | Wang et al. (2023d) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (4 hpf) | 100 nm | Waterborne (10 mg/L), 5 days | Chorion, brain, yolk sac, muscle, GI tract, pancreas, gall bladder, liver, and swim bladder | Zhou et al. (2023c) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (8 hpf) | 80 nm | Waterborne (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/L); 120 hpf; some were depurated for 10 days | Chorion, eye, brain, and dorsal trunk | Chen et al. (2024) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (23.03 ± 0.266 nm) | Waterborne (0.00000004 mg/L, 0.000034 mg/L, and 0.034 mg/L), 144 hpf | In embryos, accumulation occurred in the chorion, muscle, gills, and head of the fish; in larvae, accumulation occurred in the digestive system, gills, and somite | Santos et al. (2024) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Larvae (120 hpf) | 50 nm | Waterborne (10 mg/L), 24 h–7 days | Gut, skin, caudal fin, and eyes | Sendra et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (6 months old) | 47 nm | Waterborne 1 mg/L (3 days) | Viscera, gills, head, and muscle | Chen et al. (2017b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 42 nm | Dietary (1 mg/L); 7 days; F1 larvae were evaluated | Yolk sac, GI tract, liver, pancreas, and gall bladder | Pitt et al. (2018b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (6 months old) | 70 nm | Waterborne (0.5, 1.5, and 5 mg/L); 7 days, 30 days, and 7 weeks | Gonads, intestine, liver, and brain tissues (observed after 30 days of exposure) | Sarasamma et al. (2020) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) | 46 nm | Waterborne (2 mg/L), 21 days | Gonads | He et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) | 70 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 45 days; F1 embryos were evaluated | Whole embryos (F1) | Wu et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 80 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 21 days | Gut | Xie et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (90 days old) | 54.5 ± 2.8 nm | Waterborne (10 mg/L), 120 days; both F0 parents and F1 embryos were evaluated | F0 = gut > gills > gonad > liver F1 = whole embryo/larvae |

Zhao et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (90 days old) | 70 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 21 days; F1 larvae were evaluated at 120 hpf | Testis and ovary (F1 larvae) | Zuo et al. (2021) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) | 70 nm | Waterborne (0.1 mg/L), 3 months | Liver | Ling et al. (2022) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (3 months old) | 100 nm | Waterborne (25 mg/L); 96 h at 28°C, 29°C, and 30°C | Brain | Sulukan et al. (2022b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Juveniles and adults | 44 nm | Waterborne (0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mg/L); 30 and 60 days | Gut–brain axis | Teng et al. (2022b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.02 and 0.2 mg/L), 3 weeks | Intestine | Yu et al. (2022a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 40–54 nm | Waterborne (0.06–0.186 mg/L), 30 days | Intestine | Yu et al. (2022b) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 20–80 nm | Waterborne (0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1 mg/L), 45 days | Brain | Aliakbarzadeh et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.5 mg/L0), 28 days | Liver | Deng et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male, 4 months old) | 50 nm | Waterborne (5, 10, and 15 mg/L), exposed for 30 days and depurated for 16 days | Intestine > liver > gill> muscle > brain | Habumugisha et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 80 nm | Waterborne (15 and 150 mg/L) (21 days) | Liver | Li et al. (2023a) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (5 months old; male and female) | 70 nm | Waterborne (2 mg/L), 21 days | Gonads (testis and ovary) | Lin et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (0.1 and 1 mg/L); 4 days (depurated for 3 days) | Gut | Yang et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 30 days | Brain | Zhang et al. (2023) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | (50 ± 3 nm) | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 4 weeks | Brain | Zhou et al. (2023d) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 50–100 nm | Waterborne/dietary exposure to a high-fat diet (21 days) | Gut | Du et al. (2024) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 50 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 21 days | Liver, brain, and gonads (testis and ovary) | Ye et al. (2024) |

| PS | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | 100 nm | Waterborne (1 mg/L), 30 days | Blood, intestine, and brain | Zhang et al. (2024c) |

Accumulation of nanoplastics in the specific organs of fish at various stages of development.

Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) used two different methods of exposure (injection and trophic transfer) of PS in fathead minnows and mentioned it in one article. Manuel et al. (2022) reported the effects of PMMA, and PS in zebrafish in one article. Monikh et al. (2022) reported the effects of PE, and PPP in one article in zebrafish. Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) reported the effects of PS, and LDPE in one article in zebrafish. Zhang et al. (2020) used two different methods of exposure (injection and waterborne) of PS in zebrafish and mentioned in one article.

TABLE 6

| Fish | Plastic polymers | Developmental stage | Observed effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) | PE | Juvenile |

|

Hamed et al. (2022) |

| Carp | PS | Adults |

|

Wu et al. (2022) |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | PS | Embryos |

|

Zhang et al. (2022b) |

| Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | PS | Juveniles |

|

Estrela et al. (2021), Guimaraes et al. (2021), Liu et al. (2022a), Li et al. (2024a) |

| Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) | PS | Adults |

|

Zhang et al. (2024a) |

| Tooth carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis) | PS | Adults |

|

Saemi-Komsari et al. (2023) |

| Fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) | PS | Adult (male) |

|

Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) |

| Chinese rice fish (Oryzias sinensis) | PS | Adults and F1 embryos |

|

Chae et al. (2018) |

| Hainan medaka (Oryzias curvinotus) | PS | Adults |

|

Gao et al. (2023a) |

| Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) | PS | Adult |

|

Zhou et al. (2023a), Zhou et al. (2023b) |

| Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS, PS-NH2, and PS-COOH | Embryos |

|

Chen et al. (2023a), Yu et al. (2023) |

| Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | Larvae |

|

Kang et al. (2021), Li et al. (2024b) |

| Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | Juveniles |

|

Li et al. (2023b) |

| Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | PS | Adult |

|

Zhang et al. (2021); He et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2023a); Zhang et al. (2024b) |

| Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) | PS | Juveniles |

|

Clark et al. (2023b) |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PPP | Juveniles |

|

Wu et al. (2023) |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | Larvae |

|

Zheng and Wang (2024), Zheng et al. (2024) |

| Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) | PS | Juveniles |

|

Ding et al. (2018), Ding et al. (2020); Hao et al. (2023); Wang et al. (2023b) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | LDPE | Embryos |

|

Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PE | Embryos |

|

Monikh et al. (2022) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PE | Adults |

|

Khan and Ali (2023); Li et al. (2023c) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PET | Embryos |

|

Bashirova et al. (2023); De Souza Toedoro et al. (2024) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PMMA | Embryos |

|

Manuel et al. (2022) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PPP | Embryos |

|

Monikh et al. (2022) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS, PS-NH2, and PS-COOH | Embryos |

|

Chen et al. (2017a); Van Pomeren et al. (2017); Pitt et al. (2018a); Brun et al. (2019); Lee et al. (2019); Trevisan et al. (2019), Trevisan et al. (2020); Pedersen et al. (2020); Sokmen et al. (2020), Zhang et al. (2020), Barreto et al. (2021), Liu et al. (2021); Bhagat et al. (2022); Chackal et al. (2022); Cheng et al. (2022); Feng et al. (2022); Geum and Yeo, (2022); Kantha et al. (2022); Liu et al. (2022b); Manuel et al. (2022); Martinez-Alvarez et al. (2022); Santos et al. (2022), Teng et al. (2022a); Wang et al. (2022); Barreto et al. (2023); Chen et al. (2023b); Chen et al. (2023c); Dai et al. (2023); Duan et al. (2023); Gao et al. (2023b); Martin et al. (2023); Martin-Folgar et al. (2023); Tamayo-Belda et al. (2023); Varshney et al. (2023); Wang et al. (2023d), Wang et al. (2023e); Zhou et al. (2023c); Chen et al. (2024); Santos et al. (2024) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS | Larvae |

|

Sendra et al. (2021) |

| Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | PS | Adult |

|

Chen et al. (2017b); Pitt et al. (2018b); Sarasamma et al. (2020); He et al. (2021); Wu et al. (2021); Xie et al. (2021); Zhao et al. (2021); Zuo et al. (2021); Ling et al. (2022); Sulukan et al. (2022a); Teng et al. (2022b); Yu et al. (2022a); Yu et al. (2022b); Aliakbarzadeh et al. (2023); Deng et al. (2023); Habumugisha et al. (2023); Li et al. (2023a); Lin et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2024c); Zhou et al. (2023d); Du et al. (2024); Ye et al. (2024) |

Effects of NAPs on fish targeting toxicological endpoints.

TABLE 7

| Polymer (name, method of application, and duration) | Fish (name and developmental stage) | Organ and gene types | Upregulated | Downregulated | Unchanged | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS (80 nm) (10, 100, and 1,000 μg/L; waterborne, 8 days) | Grass carp (juveniles) | Gut/intestine | In intestine IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-1β, TNF-α, and INF-γ2 | Li et al. (2024a) | ||

| PS (50 nm) (IP injected) (0.1 mL of 5 μg/L injected volume) exposed for 48 h | Fathead minnows (adult male) | Liver and head kidney |

|

|

Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) | |

| PS (50 nm) (trophic transfer) (48 h) | Fathead minnows (adult male) | Liver and kidney |

|

|

|

Elizalde-Velazquez et al. (2020) |

| PS (100 nm) [(5 mg/g); dietary, 30 days] | Marine medaka (adults) | Gut |

|

Zhang et al. (2021) | ||

| PS (100 nm) (3.5 mg/g; dietary for 30 days) Parental exposure (F0); F1 was not exposed (observed after 60 dpf) | Marine medaka (adults) | Liver |

|

|

|

He et al. (2022) |

| PS (70 nm) (20, 200, and 2000 μg/L trophic transfer, 90 days) | Marine medaka (adults) | Intestine, liver, muscle, and F1 offspring |

|

|

Li et al. (2024b) | |

| PS (100 nm) (20 mg/L, waterborne); exposed for 7 days and depurated for 7 days | Mozambique tilapia (larvae) (4 weeks old) (0.57 ± 0.13 g body weight) | Whole fish |

|

|

Pang et al. (2021) | |

| PS (86 nm) (1 mg/L, (waterborne, exposed for 21 days and depurated for 7 days) | Nile tilapia (juveniles) (10.9 ± 3.9 g body weight) | Gut/intestine |

|

|

Hao et al. (2023) | |

| PS (100 nm) (waterborne, 1, 10, and 100 μg/L for 7 days) | Nile tilapia (juvenile body weight 15 ± 5 g) | Liver |

|

|

Wang et al. (2023b) | |

| PS (47 nm) (1 mg/L, 120 h waterborne) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole larvae |

|

|

Chen et al. (2017a) | |

| PS (70 ± 9.21 nm) (injected 0.52 nL volume of 1,000, 3,000, and 5,000 mg/L and also exposed to 0.5 and 5 mg/L PSNAP waterborne until hatching), depurated until 4 weeks) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole larvae |

|

|

Zhang et al. (2020) | |

| PS (100 nm) (exposed to 10 μg/L; waterborne until 12 hpf) and depurated until 120 hpf) | Zebrafish (embryos 2 hpf) | Whole larvae |

|

Liu et al. (2021) | ||

| PS (50 nm) (exposed to 1 mg/L; waterborne until 96 hpf) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole larvae |

|

|

|

Bhagat et al. (2022) |

| PS (50 and 100 nm) (0.1, 0.5, 2, and 10 mg/L; waterborne exposure 120 hpf | Zebrafish (embryos) | Liver |

|

Cheng et al. (2022) | ||

| PS (100 nm) (100, 200, and 400 mg/L; 24 h waterborne) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole embryo |

|

|

Feng et al. (2022) | |

| PS (100 nm) (10 μg/L, waterborne) exposed for 144 hpf and depurated for 3 days | Zebrafish (embryos, 2 hpf) | Whole embryo |

|

|

Liu et al. (2022b) | |

| PS (80 nm) (50 μg/L, 100 μg/L, 1 mg/L, 5 mg/L, and 10 mg/L; waterborne, 120 hpf) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole larvae |

|

|

|

Wang et al. (2022) |

| PS (50 nm) (0.1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 50 mg/L) (waterborne exposure for 5 days and depurated until 12 days) | Zebrafish (embryos) | Whole larvae |

|

|

Chen et al. (2023c) | |

| PS (20 nm) (2, 5, and 8 mg/L) (waterborne, exposed for 22, 46, and 70 h) | Zebrafish (embryos, 2 hpf) | Whole embryo |

|

|

Dai et al. (2023) | |

| PS (80 nm) (5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/L) (waterborne, exposed until 96 hpf) | Zebrafish (embryos 2 hpf) | Whole larvae |

|

Gao et al. (2023b) | ||

| PS (30 nm and 100 nm) (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L, exposed for 96 h) | Zebrafish (embryos 5 hpf) | Whole larvae |

|

Martin et al. (2023) | ||

| PS (30 nm) (0.1, 0.5, and 3 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 120 hpf) | Zebrafish (embryos, 1 hpf) | Whole larvae |

|

|

|

Martin-Folgar et al. (2023) |

| PS (80 nm) (0.05, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 120 hpf) | Zebrafish (fertilized eggs) | Whole larvae |

|

|

Wang et al. (2023c) | |

| PS (100 nm) (10 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 5 days) | Zebrafish embryos (2 hpf) | Whole larvae |

|

|

|

Zhou et al. (2023c) |

| PS (80 nm) (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/L) (waterborne, exposed for 120 hpf) | Zebrafish embryos (8 hpf)) | Whole larvae |

|

Chen et al. (2024) | ||

| PS (80 nm) (1 mg/L) waterborne, exposed for 21 days | Zebrafish (adults) | Gut |

|

|

Xie et al. (2021) | |

| PS (54.5 ± 2.8 nm) (10 mg/L), waterborne, exposed for 120 days. Both P1 and F1 | Zebrafish (adults) | Brain and liver |

|

Zhao et al. (2021) | ||

| PS (70 nm) (100 μg/L, waterborne, exposed for 3 months | Zebrafish (adult male and female fish) | Liver |

|

Ling et al. (2022) | ||

| PS (100 nm) (25 mg/L; exposed at 28-, 29-, and 30°C for 96 h) | Zebrafish (adults, 3 months old) | Brain |

|

Sulukan et al. (2022a) | ||

| PS (44 nm) (1, 10, and 100 μg/L, waterborne, exposed for 30 and 60 days) | Zebrafish (juveniles and adults) | Intestine |

|

|

Teng et al. (2022b) | |

| PS (100 nm) (500 ng/mL) waterborne, exposed for 28 days | Zebrafish (adults) | Liver (hepatocytes) |

|

|

Deng et al. (2023) | |

| PS (80 nm) (15 and 150 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 21 days | Zebrafish (adults) | Liver |

|

|

Li et al. (2023a) | |

| PS (100 nm) (1 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 30 days) | Zebrafish (adults) | Brain |

|

|

|

Zhang et al. (2023) |

| PS (50 nm) (1.0 mg/L, waterborne, exposed for 21 days) | Zebrafish (adults) | Gonad (ovary) and liver |

|

Ye et al. (2024) |

Genotoxic effects of NAPs on fish.

TABLE 8

| Additives (name/concentration) | Type/nature | Fish | Developmental stages | Nanoplastics (name/size/concentrations) | Mode of exposure and duration | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen (APAP) (2 and 8 mM) | Drug | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (3 hpf) | PS (80 nm) (100 μg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) |

|

Gao et al. (2023b) |

| Aeromonas hydrophilia (2 × 107 CFU/mL) | Bacteria | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | PS (80 nm) (10, 100, and 1,000 μg/L) | PS = waterborne (5 days) bacteria = injection; depurated for 3 days |

|

Li et al. (2024a) |

| nAL2O3 (1 mg/L) | Metal | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) |

|

Bhagat et al. (2022) |

| Arsenic (As; 200 μg/L) | Metalloid | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (100 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (30 days) |

|

Zhang et al. (2023) |

| As (1 mg/L) | Metalloid | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adult | PS (100 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (30 days) |

|

Zhang et al. (2024c) |

| Avobenzone (AVO) or butyl methoxydibenzoylmethane (1, 10, and 100 μg/L) | PCP/sunscreen | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (100 nm) (10 μg/L) | Waterborne (2–12 hpf). Depurated until 120 hpf |

|

Liu et al. (2021) |

| Avobenzone (AVO; 10 μg/L) | PCP/sunscreen | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (2 hpf) | PS (100 nm) (10 μg/L) | Waterborne (144 hpf). Depurated for 3 days |

|

Liu et al. (2022b) |

| Benzo [a] pyrene (BAP) (0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L) | PAH | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (0.069, 0.69, 69, 687, and 6,870 μg/L) (120 hpf) | Waterborne (120 hpf) |

|

Martinez-Alvarez et al. (2022) |

| BDE-47 (10 ng/L) | Flame retardant | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (100 nm) (2.5 and 25 μg/L) | Waterborne (7 days) |

|

Chackal et al. (2022) |

| BDE-47 (0.1 mg/L) | Flame retardant | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (80 nm) 0.05, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L | Waterborne (120 hpf) |

|

Wang et al. (2022) |

| BDE-47 (0.1 and 10 μg/L) | Flame retardant | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (80 nm) (0.05, 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 mg/L) | Waterborne (120 hpf) |

|

Wang et al. (2023c) |

| Butylmethoxydibenzoylmethane (BMDBM) or avobenzone (1,10, and 100 μg/L) | PCP/sunscreen | Zebrafish | Embryos (2 hpf) | PS (100 nm) (10 μg/L) | Waterborne (2–12 hpf) |

|

Liu et al. (2021) |

| Bisphenol A (BPA) (100 μg/L) | Plastic additive | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Embryos (6 hpf) | PS (50 nm) (55 μg/L) | Waterborne (21 days) |

|

Yu et al. (2023) |

| BPA (0.78 μg/L) | Plastic additive | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (6 months old) | PS (47 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (3 days) |

|

Chen et al. (2017b) |

| nCeOs (1 mg/L) | Metal | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) |

|

Bhagat et al. (2022) |

| Chloroauric acid (1 μg/mL) | Inorganic compound | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (0.1 mg/L) | Waterborne (6, 24, and 96 hpf) |

|

Lee et al. (2019) |

| p, p’-DDE (100 μg/L) | Insecticide | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (15 nm) (50 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) |

|

Varshney et al. (2023) |

| Diethylstilbesterol (DES) (1,10, and 100 ng/L) | Synthetic hormone (estradiol) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) 5 months old | PS (70 nm) (2 mg/L) | Waterborne (21 days) |

|

Lin et al. (2023) |

| Diphenhydramine (DPH) (0.01 and 10 mg/L) | Antihistamine | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (44 nm) (0.015 and 1.5 mg/L) | Waterborne (96–120 f) |

|

Barreto et al. (2023) |

| 17α-ethinylestradiol (EE2) (2 and 20 μg/L) | Hormone (synthetic estrogen) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (47 nm) (1 mg/L | Waterborne (120 h) |

|

Chen et al. (2017a) |

| F-53B (500 μg/L) | Polyfluoroalkyl substance | Hainan medaka (Oryzias curvinotus) | Adults (length 2.85 ± 0.17 cm; weight 440 ± 90 mg) | PS (80 nm) (200 μg/L) | Waterborne (7 days) |

|

Gao et al. (2023a) |

| Glucose (40 mM) | Carbohydrate | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Larvae (72 hpf) | PS (25 nm) (20 mg/L) | Waterborne (exposed 72–120 hpf) |

|

Brun et al. (2019) |

| Homosolate (0.0262–262 μg/L) | Organic compound/UV filter | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (50 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne days) |

|

Ye et al. (2024) |

| Lead (50 μg/L) | Metal | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (100 nm) (20 and 200 μg/L) | Waterborne (exposed for 3 weeks) |

|

Yu et al. (2022a) |

| Microcystin LR (MCLR) (0.9, 4.5, and 22.5 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (70 nm) (100 μg/L) | Waterborne (96 h) 21 days parental exposure (F0) and F1 larvae (120 hpf) were evaluated without exposure |

|

Zuo et al. (2021) |

| Microcystin LR (MCL) (0.9, 4.5, and 22.5 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) | PS (70 nm) (100 μg/L) | Waterborne (96 h) 3 months |

|

Ling et al. (2022) |

| Microcystin-LR (MSL) (1 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) | Adults (9.33 ± 1.01 cm length, 10.43 ± 3.41 g weight) | PS (80 nm) (10 and 1,000 μg/L) | Waterborne (96 h) |

|

Zhang et al. (2024a) |

| 4-Nonylphenol (1 μg/L) | Nonionic surfactant | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (20–80 nm) average size 57.5 nm (0.1, 1, 10, and 100 μg/L) | Waterborne (45 days) |

|

Aliakbarzadeh et al. (2023) |

| Oxytetracycline (100 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (6 months old) | PS (40–54 nm) (60–338 μg/L) | Waterborne (30 days) |

|

Yu et al. (2022b) |

| Penicillin (1 and 10 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos (8 hpf) | PS (80 nm) (0.5 and 5 mg/L) | Waterborne (120 hpf) |

|

Chen et al. (2023b) |

| Phenanthrene (PHE) (0.1, 0.5, and 1.0 mg/L) and jellyfish mucin (50 μg/mL) | PHE (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon); mucin (biological substance) | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (5 mg/L) | Waterborne (4, 8, 12, 24, 32, 48, and 72 hpf) |

|

Geum and Yeo, (2022) |

| Phenmedipham (PHN) (0.02, 0.2, and 20 mg/L) | Herbicide | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (44 nm) (0.015 and 1.5 mg/L) | Waterborne (96–120 hpf) |

|

Santos et al. (2022) |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) (5.07–25.36 μg/L) | Organic substance | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (44 nm) (0.1, 1, and 10 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) |

|

Trevisan et al. (2019) |

| Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) (1 mg/L) | Organic substance | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (44 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 hpf) (7 days) |

|

Trevisan et al. (2020) |

| Simvastatin (SIM) (0.015–150 μg/L) | Statin | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (60 nm) (0.05 or 1.5 mg/L) | Waterborne (96 h) |

|

Barreto et al. (2021) |

| Sodium nitroprusside (8 µM) | Inorganic compound/ | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Embryos | PS (50 nm) (20 mg/L) | Waterborne (12 days) |

|

Chen et al. (2023c) |

| Sulfamethazine (SMZ) (0.5 and 5 mg/g) | Antimicrobial agent | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults | PS (100 nm) (5 mg/g) | Dietary (30 days) |

|

Zhang et al. (2021) |

| Sulfamethazine (SMZ) (4.62 mg/g) | Antimicrobial agent | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults (580.2 ± 189.5 mg body weight) | PS (100 nm) (3.45 mg/g) | Dietary (30 days) parental (F0) exposure; F1 evaluated after 60 days |

|

He et al. (2022) |

| Sulfamethazine (SMZ) (0.5 and 5 mg/g) | Antimicrobial agent | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Adults (4 months old) | PS (100 nm) (5 mg/g) | Dietary (30 days) depurated 21 days |

|

Wang et al. (2023a) |

| Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) (100 μg/L | Antibiotics | Marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) | Juveniles (2 months old) | PS (100 nm) (1 mg/L) | Waterborne (30 days) |

|

Li et al. (2023b) |

| Tetracycline (TC) (5,000 μg/L) | Antibiotics | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | PS (80 nm) (20, 200, and 2000 μg/L) - | Waterborne (7 days) |

|

Liu et al. (2022a) |

| Triclosan (TCS) (0.01, 0.1, and 1 mg/kg) | Biocide | Tooth carp (Aphaniops hormuzensis) | Adults | PS (100 nm) (0.5 mg/L) | Dietary (3, 14, and 28 days) |

|

Saemi-Komsari et al. (2023) |

| Triphenyl phosphate (TPhP) (0.08, 0.5, 0.7, 1, 1.2, and 1.5 mg/L) | Flame-retardant and plasticizer | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults (male and female) | PSNAP (46 nm) (2 mg/L) | Waterborne (21 days) |

|

He et al. (2021) |

| Tris (1,3-dichloro-2-propyl) phosphate (TDCIPP) (0.47, 2.64, or 12.78 μg/L) | Flame-retardant | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (54.5 ± 2.8 nm) (10 mg/L) | Waterborne (120 days) evaluated F0 and F1 larvae (without exposure) |

|

Zhao et al. (2021) |

| Vitamin D (280 and 2,800 IU/kg body weight) | Vitamin | Zebrafish (Danio rerio) | Adults | PS (80 nm) (15 and 150 mg/L) | Dietary (for 21 days) |

|

Li et al. (2023a) |

| ZnO (760 μg/L) | Metal oxide | Grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) | Juveniles | PS (23.03 ± 0.266 nm) (760 μg/L) | Waterborne (72 h) |

|

Estrela et al. (2021) |

Effects of NAPs and various environmental contaminants used in coexposure studies on the toxicological endpoints of fish.

TABLE 9

| Additives (name/concentration) | Type/nature | Fish | Developmental stages | Nanoplastics (name/size/concentrations) | Mode of exposure and duration | Gene expressions | References |