Abstract

Read-across has matured from an expert-driven extrapolation based largely on structural analogy into a rigorously documented, mechanistically informed cornerstone of next-generation risk assessment. Three pivotal frameworks are compared that now shape its regulatory use: the European Food Safety Authority’s (EFSA) 2025 guidance for food and feed safety, the European Chemicals Agency’s (ECHA) Read-Across Assessment Framework (RAAF) for industrial chemicals under REACH, and the community-driven Good Read-Across Practice (GRAP) principles. Using five analytical lenses—conceptual structure, scientific rigor, implementation tools, regulatory acceptance, and practical impact—we identified areas of complementarity and divergence. EFSA provides a seven-step, uncertainty-anchored workflow that actively embeds new approach methodologies (NAMs) and adverse outcome pathway reasoning, offering applicants a transparent “how-to” template. RAAF, in contrast, operates as an evaluator’s rubric: six scenario types and associated assessment elements delineate what evidence must be delivered, thereby standardizing regulatory scrutiny but leaving dossier construction to the registrant. GRAP supplies the conceptual glue, emphasizing mechanistic plausibility, exhaustive analogue selection, explicit uncertainty characterization, and the strategic use of NAMs; its influence is evident in both EFSA’s and ECHA’s evolving expectations. (Terminology note: the acronym “NAM” was popularized at an ECHA workshop in 2016; earlier documents such as RAAF and initial GRAP papers therefore may not use the term explicitly). Regulatory experience under REACH demonstrates that dossier quality and acceptance rates rise markedly when RAAF criteria are met, while EFSA’s new guidance is poised to catalyze similar gains in food and feed assessments. Globally, the convergence of these frameworks—reinforced by OECD initiatives and NAM-enhanced case studies—signals an emerging international consensus on what constitutes defensible read-across. In conclusion, harmonizing EFSA’s procedural roadmap with RAAF’s evaluative rigor and GRAP’s best-practice ethos can mainstream reliable, animal-saving read-across across regulatory domains, paving the way for fully mechanistic, AI-enabled chemical safety assessment.

1 Introduction

Read-across can be implemented via two distinct but complementary modes: analogue and category approaches. In the analogue approach, a single well-justified source substance is used to fill a data gap for a structurally and mechanistically similar target. In the category approach, multiple related substances are grouped a priori and consistent trends (or shared mechanistic features) across the group are used to interpolate or extrapolate the target’s property. Regulatory frameworks considered here accommodate both, but differ in the degree to which they prescribe dossier construction (EFSA), evaluation (RAAF), or best-practice principles (GRAP/OECD GD 194). The read across approach is in principle applied in the same way for both toxicology and ecotoxicology assessment, even though this analysis is mainly focusing to human toxicology in the EU context.

In the evolving landscape of regulatory toxicology, read-across has emerged as a cornerstone strategy for reducing reliance on animal testing while maintaining scientific and regulatory integrity. At its core, read-across allows toxicologists to infer the properties of a chemical substance (the “target”) by leveraging known data from one or more similar substances (the “source”). This can be applied via an analogue approach, in which data from a single well-characterized source chemical are extrapolated to a target, or a category approach, in which multiple related chemicals are considered as a group to identify consistent trends for interpolation of the target’s properties.

The underlying premise—that structural and mechanistic similarity can justify extrapolation of hazard information—has long been practiced informally, but in recent years it has been codified through formal frameworks. These include first the OECD guidance from 2014, revised 20171 (OECD GD 194), and the European Chemicals Agency’s Read-Across Assessment Framework (RAAF) (ECHA, 2017), developed to guide chemical safety assessments under the REACH regulation (Regulation EC 1907/2006 concerning the Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals); the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)’s 2025 guidance on read-across for food and feed safety evaluation (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2025); and the Good Read-Across Practice (GRAP) (Ball et al., 2016) principles, which emerged from academic-industry collaborations to address scientific challenges and improve methodological consistency.

Alongside Bennekou et al. (2025) and ECHA’s RAAF, this analysis is benchmarked against OECD’s Guidance on Grouping of Chemicals (OECD GD 194, 2017)—the international baseline for grouping chemicals via either analogue or category approaches. OECD GD 194 defines grouping as considering more than one chemical at a time to fill data gaps, operationalized as an analogue approach (predicting a target from one or more similar sources) or a category approach (inferring across a set showing similar or trend-based properties). It also codifies the principal data-gap filling tools—read-across, trend analysis and (Q)SAR—and provides stepwise procedures and reporting formats for documenting analogue/category justifications. Importantly, OECD GD 194 includes specific guidance for complex unknown or variable composition, complex reaction products or of biological materials (UVCBs) and how to build defensible categories for them. Therefore OECD GD 194 is used as a common denominator when comparing EFSA’s procedural roadmap, RAAF’s evaluator rubric, and the GRAP best-practice ethos.

Despite their shared goal of promoting scientifically credible read-across, these frameworks differ in structure, emphasis, and regulatory context. The RAAF focuses on standardizing the evaluation of read-across justifications, providing assessors of the REACH registration dossiers, with a scenario-based checklist of critical elements. In contrast, EFSA’s guidance aims to structure the development of a read-across argument for feed and food risk assessment, embedding it within a transparent, stepwise weight-of-evidence framework that explicitly incorporates uncertainty analysis and encourages the integration of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). Notably, the acronym “NAM” was introduced only in 2016 at an ECHA workshop, after RAAF and the initial GRAP guidance were already published. GRAP, by contrast, is not linked to a definitive scope and operates as a conceptual and practical guide, distilling insights from case studies and regulatory experiences to recommend best practices—particularly for incorporating mechanistic reasoning, biological similarity, and toxicokinetic considerations. These differences reflect the distinct regulatory mandates of the respective bodies: EFSA’s focus on direct human exposure via food and feed necessitates more conservative decision thresholds, while REACH applications may place more weight on grouping substances for hazard classification. Understanding how these frameworks align or diverge is essential for practitioners navigating different regulatory landscapes and for harmonizing scientific approaches across sectors.

This article presents a comparative analysis of the Bennekou et al. (2025) guidance, ECHA’s RAAF, and GRAP principles, with the goal of identifying synergies, divergences, and opportunities for integration. Each framework is examined through five analytical lenses: (i) conceptual structure—how each defines and organizes the read-across process; (ii) scientific rigor—how key criteria such as structural and biological similarity, ADME properties, and mechanistic plausibility are addressed; (iii) implementation aspects—including use of case studies, templates, and supporting tools; (iv) regulatory acceptance and impact, and (v) practical utility—namely, whether the frameworks enable or hinder the routine use of read-across in practice. In doing so, the authors also reflect on the development and dissemination of GRAP, to which the authors have directly contributed, and assess its role in influencing or complementing formal regulatory frameworks. This comparison focuses primarily on EU requirements, as both documents are issued by an EU agency and an EU authority, respectively. The aim is not to exclude other approaches, but to provide a direct comparison of the documents in the context of the EU principle of “one substance, one assessment,” which applies to substances that may fall under the scope of both agencies. While the focus is on EU frameworks, the underlying principles have broader applicability, and the considerations outlined are relevant in other regulatory contexts. In this regard, OECD GD 194 provides a complementary perspective. As formally endorsed by the OECD, the guidance is expected to be accepted by all member countries, provided that the use of read-across is permitted under local regulations. Even with this limitation, the approach described in OECD GD 194 represents a wide international harmonization efforts, reinforcing the principles highlighted in the EU context.

This comparison is particularly timely in light of recent advances in toxicological science. The past decade has seen rapid progress in mechanistic toxicology, bioinformatics, and systems-level approaches, including the rise of NAMs, adverse outcome pathways (AOPs), multi-omics, and AI-enhanced predictive models such as Generalized Read-Across (GenRA) and quantitative RASAR. These advances offer powerful new tools to substantiate read-across hypotheses but also raise new questions about how frameworks should evolve to accommodate them. Understanding how EFSA, ECHA, and GRAP respond to these scientific developments is crucial for ensuring that innovation in toxicology translates into regulatory impact. By aligning structured regulatory expectations with the flexibility and scientific depth of GRAP, the field is poised to realize a harmonized, mechanistically informed, and innovation-ready future for read-across in chemical safety assessment. Noteworthy, results from in vivo tests for risk assessment are still necessary in many sectors and the read-across approach represents the only possibility to waive new animal tests, making this opportunity outstanding.

2 Comparative conceptual frameworks for read-across

This section introduces each framework’s overarching approach and philosophy, before delving into detailed comparisons in later sections (Table 1). OECD GD 194 (2014)1 provides the foundational, cross-regulatory blueprint for grouping and read-across, defining two complementary modes: the analogue approach (predicting a target from one or more similar sources) and the category approach (inferring across a group that shows consistent trends or shared mechanisms). Conceptually, OECD GD 194, is hypothesis-driven: a read-across/category rationale must articulate the scientific basis for similarity (structural motifs, functional groups, Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME)/toxicokinetics, bioactivity/Mode of Action (MoA) or Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) links, and relevant physico-chemical domains), set applicability/boundaries (including subcategories), and be supported by transparent data matrices and data adequacy reviews. For data-gap filling it formalizes three tools—read-across (qualitative or quantitative), trend analysis (often a local/internal Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) within a category), and (Q)SAR (external models)—embedded in a weight-of-evidence narrative with explicit handling of uncertainties. The guidance supplies stepwise procedures for both analogue (identify candidates → compile/evaluate data → justify similarity → document) and category formation (develop hypothesis/definition → gather and grade data → fill gaps via read-across/trends/(Q)SAR → propose minimal testing → finalize documentation via Analysis and Research Compendium/case report form (ARF/CRF) formats). Notably, it addresses complex substances/UVCBs, requiring granular composition characterization, marker constituents, and conservative handling of unknown fractions. In this comparative frame, OECD GD 194 functions as the methodological baseline against which EFSA’s procedural roadmap, ECHA’s evaluator-centric RAAF, and GRAP’s best-practice principles can be aligned.

TABLE 1

| Feature | EFSA guidance (Food/Feed, 2025) | ECHA RAAF (REACH 2015, 2017) | Good read-across practice (GRAP, 2016) | OECD GD 194 (2007, 2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framework Type | Step-by-step procedural guide (6 steps; unified for analogue or category cases) | Scenario-based evaluator tool (6 scenarios with Assessment Elements) used for category building and justification in registrations | Conceptual and flexible best-practice model | Stepwise international guidance document (covers both analogue and category grouping approaches) |

| Key Components | Problem formulation; target characterization; source (analogue) selection; data gap filling; explicit uncertainty analysis | Identification of analogues vs. categories; demonstration of structural and biological similarity; justification for grouping; critical review of uncertainties; assessment criteria and quantification | Emphasis on mechanistic (biological) similarity, comprehensive weight-of-evidence, transparency, and strategic use of NAMs/AOPs | Definition of category or analogue hypothesis; careful composition characterization of each substance; data collection and matrix; evaluation of data adequacy; data gap filling via read-across or testing (including QSAR support); thorough documentation of the justification |

| NAM Integration | NAMs actively encouraged and prioritized (use in vitro/in silico before new animal tests) | Not explicitly integrated (in 2017 RAAF), but compatible with NAM evidence if scientifically justified | Strong encouragement to integrate in vitro and in silico data (omics, AOPs, etc.) to bolster mechanistic plausibility | Implicit use of alternative data (QSAR models, analogues) is discussed; encourages use of SAR/QSAR and other non-animal data as supporting evidence |

| Uncertainty | Dedicated step for uncertainty characterization and predefined acceptability thresholds | Evaluated indirectly within each assessment element (uncertainties must be addressed per element) | Central focus on uncertainty: advocates explicit characterization and discussion of uncertainties and assumptions | Addressed qualitatively via weight-of-evidence – emphasizes scientific justification for predictions but no separate uncertainty quantification step in framework |

| Intended Users | Applicants (dossier submitters) and EFSA risk assessors; domain-specific (food/feed additives, contaminants) | Primarily regulatory evaluators (ECHA staff), though industry uses it as a de facto checklist for dossier preparation; industry primarily uses the RAAF for category building and justification in registrations | Broadly applicable: researchers, industry scientists, and regulators across sectors (general best practices) | Regulators and industry scientists globally; applicable across international programs (e.g., OECD High Production Volume program, REACH) for hazard assessment and data gap filling |

| Regulatory Status | Official guidance document (EFSA Scientific Committee) | Internal evaluator’s tool (ECHA), publicly available to guide submissions and evaluations | Non-binding consensus principles (publication in peer-reviewed literature) – influential via scientific acceptance | Official OECD guidance document – not legally binding but internationally recognized best practice |

| Evolution | New in 2025, incorporating EU-ToxRisk findings and updated uncertainty analysis guidance | First introduced 2015 (updated 2017); may require future revision to fully integrate modern NAM data and approaches | Originated ∼2016; refined through subsequent workshops and case study publications (e.g., Rovida et al., 2020) | First edition in 2007; expanded second edition in 2017; serves as a foundation for later OECD guidance (e.g., grouping approaches for nanomaterials) and ongoing global harmonization efforts |

Comparative summary of read-across frameworks.

2.1 EFSA’s 2025 read-across guidance (food/feed safety)

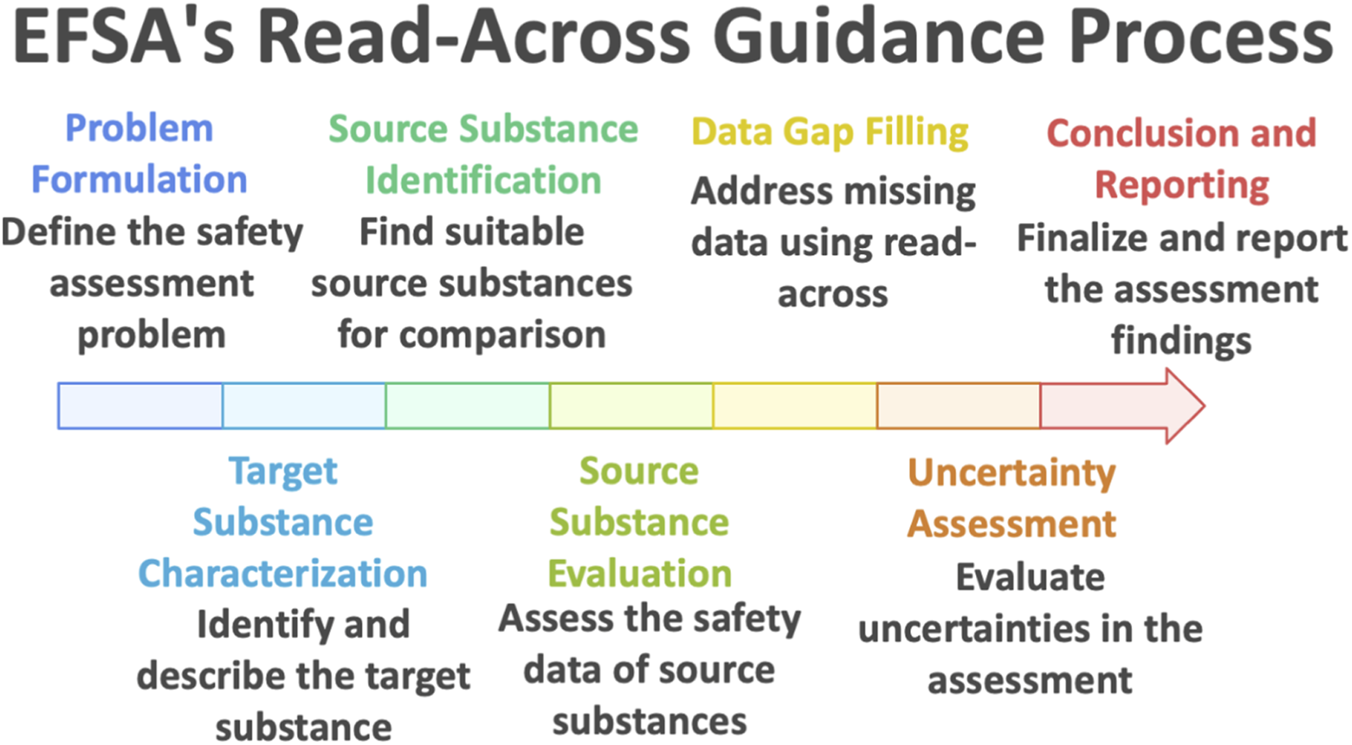

Bennekou et al. (2025) guidance marks a significant step forward in formalizing the use of read-across for food and feed safety assessment. Unlike earlier, more general references to read-across in regulatory practice, this guidance provides a detailed, procedural framework intended to be used both by applicants preparing dossiers and by risk assessors reviewing them. Structured as a seven-step process (Figure 1), the framework guides users from initial problem formulation through to reporting and decision-making. Each phase—(1) Problem formulation, (2) Target substance characterization, (3) Source substance identification, (4) Source substance evaluation, (5) Data gap filling, (6) Uncertainty assessment, and (7) Conclusion and reporting—is tightly embedded within a weight-of-evidence philosophy. By doing so, the guidance ensures that all relevant information is considered and synthesized in a transparent, logical sequence, aligning with EFSA’s general principles for scientific assessment.

FIGURE 1

Read across process according to EFSA (2025).

Conceptually, EFSA’s framework places strong emphasis on transparency, traceability, and scientific neutrality. The process begins with a careful definition of the regulatory context and problem formulation, including the specific decision question, the critical toxicological endpoint(s), and the acceptable level of uncertainty for the risk assessment at hand. This sets the stage for a clearly articulated read-across hypothesis, which must be iteratively evaluated and, if necessary, refined through the subsequent steps. Rather than treating read-across as a binary yes/no decision, the guidance views it as a hypothesis-driven method that must be continuously validated as more evidence—chemical, biological, or mechanistic—is gathered. This iterative and hypothesis-based logic distinguishes the EFSA approach from simpler structural analogies and is critical for building scientific credibility in the prediction.

A distinguishing feature of the 2025 EFSA guidance is its systematic integration of new approach methodologies (NAMs), including in vitro, in silico, and mechanistic data sources. The framework actively encourages applicants to use NAM data to strengthen or clarify key aspects of the read-across hypothesis, such as toxicodynamic similarity, metabolic convergence, or tissue distribution. Indeed, the guidance explicitly recommends exploring the applicability of NAMs as a first option before resorting to additional in vivo testing. This proactive positioning of NAMs reflects EFSA’s broader commitment to the 3Rs principle and aligns with emerging trends in mechanistically informed toxicology. Notably, the guidance acknowledges that while NAMs can reduce uncertainty, their use must be accompanied by appropriate validation and contextualization. To support this, the guidance encourages the incorporation of AOP-based reasoning, kinetic modeling (e.g., Physiologically based pharmacokinetic, (PBPK)), and other lines of evidence that can demonstrate biological relevance and mechanistic plausibility.

The overarching objective of the EFSA framework is to foster a read-across process that is both scientifically robust and practically applicable within the constraints of regulatory decision-making. By providing a clear procedural map, by requiring systematic evaluation of uncertainty, and by explicitly welcoming modern toxicological tools, EFSA aims to increase both the scientific defensibility and regulatory acceptance of read-across. In doing so, the guidance not only strengthens the methodological integrity of read-across within the food and feed sectors but also sets a benchmark for how sector-specific frameworks can incorporate evolving scientific standards without compromising regulatory clarity. As a result, EFSA’s framework functions not merely as a regulatory checklist but as a scientific tool for guiding sound judgment in the face of incomplete data—exactly the condition under which read-across is most often needed.

2.2 ECHA’s Read-Across Assessment Framework (RAAF)

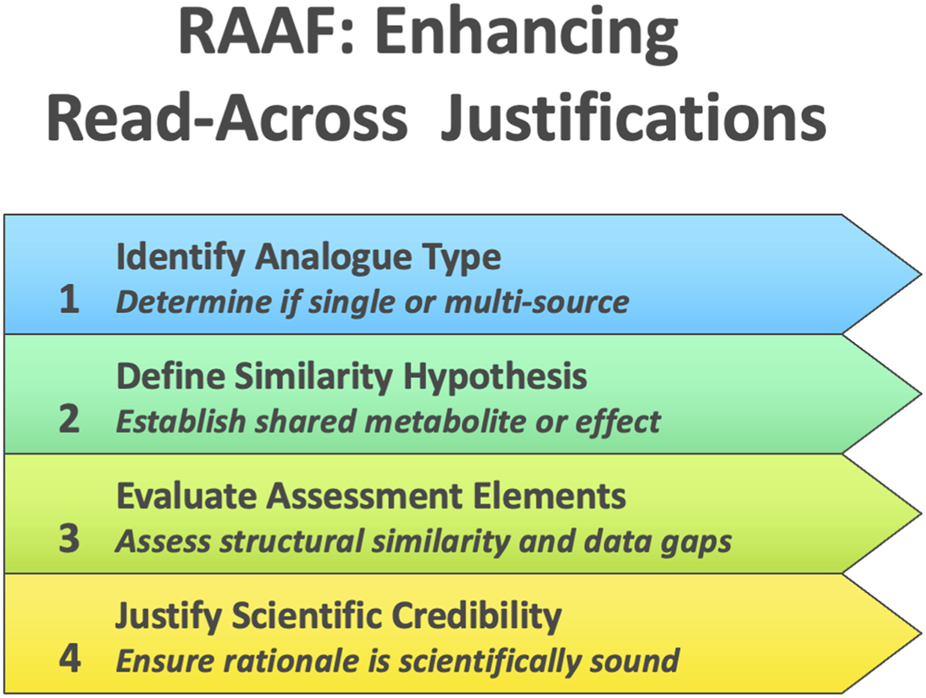

ECHA’s RAAF represents a complementary approach to EFSA’s guidance, functioning not as a how-to manual but as a structured evaluative rubric for read-across under REACH. While not originally intended for submitters, the RAAF was from the outset recognized as shaping how companies structured their read-across arguments, as documented in the 2012 ECHA–Cefic workshop proceedings2. The RAAF codifies common read-across scenarios, each defined by the nature of the analogues (single-source “analogue” vs. multi-source “category”) and the hypothesis underpinning similarity (e.g., shared metabolite vs. common toxicological effect). For each scenario, a set of predefined “assessment elements” (AEs) enumerates the critical scientific considerations that an assessor must scrutinize, such as the adequacy of structural similarity, toxicokinetic comparability, and coverage of data gaps. By guiding experts to judge each element of a read-across case systematically, the RAAF ensures that the fundamental scientific principles behind the read-across are transparently evaluated in a consistent manner (Figure 2). A 2018 meeting report by Chesnut et al. (2018) highlighted regulators’ recognition of read-across as the most frequently used alternative to animal testing, while simultaneously emphasizing key obstacles to its broader use—including lack of guidance, uncertainty communication, and reproducibility concerns that were only partially addressed pre-2025. Crucially, the framework focuses on the scientific credibility of the read-across rationale itself–it delineates what aspects need to be justified, without prescribing how a practitioner should construct the read-across argument. This high-level structure was initially developed for internal use by ECHA to harmonize dossier evaluations, but it was later published to inform registrants of the “rules of the game,” thereby prompting improvements in the quality of read-across justifications submitted under REACH. The intended regulatory impact of the RAAF has been to raise the bar for acceptability by clearly identifying the evidentiary elements a valid read-across must contain. In practice, the introduction of RAAF has translated to more predictable and rigorous scrutiny of read-across cases: if a dossier’s read-across hypothesis is implausible or key supporting evidence is missing for an AE, ECHA will deem the justification inadequate, often leading to requests for additional (in vivo) data. By making the evaluation criteria explicit, the RAAF has thus driven both regulators and industry toward a more scientifically robust read-across process, even as it acknowledges the need for expert judgment and case-by-case flexibility in interpreting its framework.

FIGURE 2

ECHA’s read-across assessment framework (RAAF).

ECHA accepted 49% of submitted read-across hypotheses for chemical toxicity during the testing proposal phase between 2008 and August 2023 (Roe, 2025). The acceptance rate is notably higher for group-based read-across approaches (about 62%) compared to analogue read-across types (about 39%).

Key factors influencing acceptance2 include the structural similarity between target and source substances—read-across proposals with very high similarity had acceptance rates over 75%, while those with lower similarity dropped to about 31%. Acceptance rates were also initially higher (2012–2015) but declined after ECHA’s Read-Across Assessment Framework (RAAF) first publication in 2015 and updated in 2017 as the process became more standardized.

2.3 Good read-across practice (GRAP)

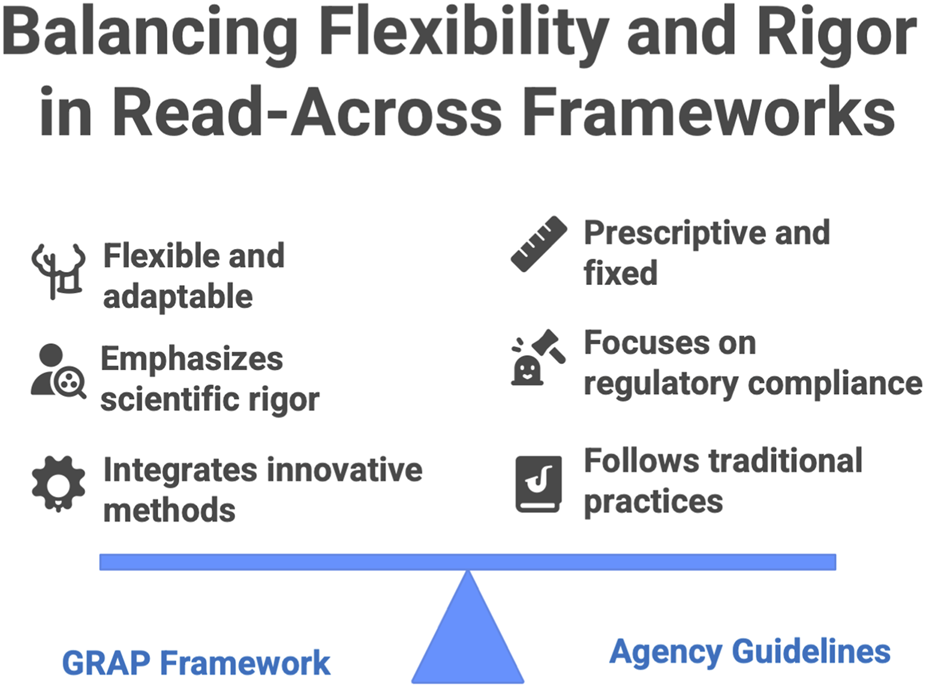

Parallel to these agency-led frameworks, the concept of Good Read-Across Practice (GRAP) emerged from an academic–industry collaboration as a consensus-driven best practice guide for developing read-across arguments. Introduced in 2016 by Ball and colleagues (Ball et al., 2016), GRAP was conceived as a flexible yet rigorous framework to maximize the scientific robustness and transparency of read-across, complementing official guidelines. Instead of a fixed procedural template, GRAP provides overarching principles and a conceptual structure that can be tailored to different regulatory contexts while upholding high standards of evidence. A central tenet is the emphasis on scientific plausibility: a GRAP-compliant read-across must demonstrate a sound rationale for expecting similar hazard outcomes between source and target chemicals, which in turn hinges on a well-substantiated basis for similarity (structural, biological, or both). To this end, the GRAP approach encourages exhaustive and impartial exploration of potential source analogues and data. All plausible source substances should be considered, and any exclusion or inclusion of data must be transparently justified, thereby avoiding cherry-picking of evidence. This comprehensive weight-of-evidence strategy is coupled with an insistence on explicit uncertainty analysis: at each stage, and especially in the final read-across prediction, residual uncertainties should be clearly characterized and quantified where possible. By documenting every step–from initial analog selection criteria to the rationale for rejecting or accepting certain data points–GRAP seeks to make the reasoning process as reproducible and unbiased as possible (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

Good read-across practice aiming to balance flexibility and rigor.

In terms of technical innovation, GRAP brought attention to integrating NAMs (e.g., high-throughput in vitro assays, computational predictions) into read-across as supportive evidence (Zhu et al., 2016), foreshadowing later regulatory trends toward NAMs. Indeed, the GRAP guidance highlighted how mechanistic bioactivity data and modern cheminformatics tools can bolster the justification for similarity between substances. This forward-looking incorporation of novel data streams, along with its formal strategies for uncertainty communication, marked a step beyond earlier broad guidance by providing a more nuanced template for what a “scientifically rigorous” read-across should entail. Although not a regulatory mandate, GRAP has had a notable influence on the community’s expectations. Its publication and subsequent international workshops (Chesnut et al., 2018; Rovida et al., 2020) underscored that adhering to these best-practice principles could significantly improve the odds of regulatory acceptance of read-across cases. Regulators have indirectly welcomed GRAP insofar as it addresses many shortcomings previously seen in read-across submissions (for example, opaque reasoning or insufficient justification of similarity) by advocating greater clarity, completeness, and methodological discipline. The conceptual flexibility of GRAP means it can be applied across different jurisdictions and chemical domains, serving as a unifying reference that aligns industry practice with the overarching scientific standards valued by bodies like ECHA and EFSA. In summary, GRAP functions as an academic and industry-derived conceptual framework that, while less prescriptive than agency guidelines, reinforces and extends the core principles necessary for credible read-across, ultimately aiming to bridge the gap between innovative hazard prediction approaches and their regulatory trustworthiness.

UVCBs pose specific challenges for read-across due to compositional variability. Recent guidance converges on three pillars: (i) granular composition characterization of both source and target, ideally identifying all ≥1% constituents and bounding the unknown fraction; (ii) a mechanistic hypothesis or category rationale linking constituents or shared structural features to the predicted hazard; and (iii) transparent uncertainty treatment when constituent levels differ or compositional variability is non-negligible. ECHA’s 2022 advice on UVCB read-across highlights that similarity may be established where mixtures share identical constituents in different proportions or distinct, structurally analogous constituents—provided differences do not affect the endpoint. OECD GD 194 (2014) likewise emphasises defining category boundaries (e.g., carbon range, distillation range), identifying marker constituents, and using data matrices, local QSARs or potency-weighted constituent information to support predictions.

2.4 Read-across for UVCB substances (complex mixtures)

Regulatory read-across frameworks have traditionally dealt with defined single- or multi-constituent chemicals, but UVCBs pose unique challenges. UVCBs are characterized by complex, partially undefined compositions and inherent variability, making it difficult to establish the “sufficient similarity” required for read-across. Recent guidance initiatives–notably a 2022 ECHA advisory document on read-across for UVCBs and the OECD’s 2014 chemical grouping guidance–provide direction for applying read-across principles to these complex substances.

ECHA’s 2022 guidance (following a 2021 REACH Annex revision) lays out stringent conditions for UVCB read-across. It emphasizes that structural similarity must be demonstrated on the level of individual constituents. In practice, this means all major constituents of the UVCB need to be identified and compared across substances. The guidance specifies that every constituent present at ≥1% w/w should be identified, and the identified constituents must collectively account for at least 80% of the UVCB’s mass. If more than ∼20% of a UVCB’s composition is unknown or uncharacterized, “it is not possible to establish structural similarity” for the purpose of read-across. Two modes of comparing UVCBs are recognized: in some cases the source and target UVCBs may share identical constituents in different proportions; in others, they may have different constituents that are nevertheless structurally analogous to each other. Both situations require demonstrating that any differences in composition (or in constituent concentrations) do not materially affect the property being predicted. By definition, UVCBs exhibit composition variability; however, the guidance insists that this variability must be bounded and understood. Constituent concentrations should be measured in multiple samples to characterize variability, and differences in the levels of specific constituents between source and target must be factored into the similarity argument. Simply showing that two UVCBs contain a common list of constituents is insufficient–one must also show comparable levels or a rationale why differing concentrations (or unknown fractions) do not alter the hazard in question. Importantly, if a known hazardous constituent is present, its concentration across the category should be carefully considered (and often matched or treated as worst-case) in the read-across justification. These provisions underscore that read-across for UVCBs demands a much more granular understanding of composition than for traditional single-component substances.

OECD GD 194 grouping guidance similarly addresses complex substances by outlining best practices for forming a “category” of analogues when chemicals are multi constituent substances or UVCBs. A key initial step is to clearly define the category and its members, which for UVCBs often means identifying a set of representative single-constituent analogues that span the range of components present in the complex mixtures. The guidance stresses detailed composition characterization to the extent practicable–for example, specifying critical compositional parameters such as carbon-chain length ranges, boiling point or distillation ranges, or other descriptors that delineate category members. Any known or generic description of the mixture’s makeup should be provided, and marker chemicals (signature constituents) should be identified and quantified in each member of the group if possible. This helps ensure that each complex substance in the category can be directly compared via common reference points. The OECD framework also advises identifying representative constituent compounds covering the diversity of structures present, and flagging any constituents with outlying properties (for instance, a particular component known to drive a specific toxicity). Such outliers may need to be addressed with additional data or conservative assumptions. When it comes to filling data gaps for category members, the OECD notes that read-across or trend analysis can often be applied qualitatively within a well-defined category, whereas fully quantitative predictions may be more uncertain for UVCBs. In some cases a “local QSAR” or toxic equivalence factor approach can be developed, using data on individual constituents to predict multi constituent behavior. For example, if each complex substance can be represented as a combination of certain constituent profiles, one might employ potency estimates of those constituents (or surrogate compounds) to estimate the mixture’s overall hazard. The guidance acknowledges that quantitative read-across for UVCBs is challenging, but it is feasible to establish at least a bounding range of hazard values or to use a weighted approach if mechanistic understanding allows. Throughout, transparent documentation is emphasized: the category justification for UVCBs should clearly explain how structural similarity is assessed (e.g., what compositional parameters are considered “similar enough”), how any missing information is extrapolated, and what uncertainties remain due to the unknown fraction or variability of composition.

In summary, both the ECHA 2022 advice and OECD 2014 guidance converge on certain key principles for UVCB read-across. They require a rigorous characterization of composition (to minimize the “unknown” portion and ensure comparability), insist on a mechanistic hypothesis or rationale linking the category members (why their shared constituents or structural features would yield similar toxicological profiles), and provide for careful treatment of uncertainties arising from variable or unidentified constituents. While applying read-across to UVCBs is inevitably more complex than for defined single chemicals, these guidances offer a pathway to do so scientifically. They encourage the use of all available analytical data, computational tools, and theoretical considerations to build a case that even complex, variable substances can be grouped and assessed as a category. With these additional safeguards and explanations in place, regulators can gain confidence in read-across predictions for UVCBs, enabling hazard and risk assessments to proceed with reduced animal testing even for substances that challenge our traditional notions of chemical identity.

Under the European Union’s REACH Regulation, the assessment of UVCBs relies heavily on a clear and consistent definition of substance identity and on the use of structured read-across or category approaches, as articulated in the ECHA RAAF (ECHA, 2017). REACH requires that similarity among UVCBs be scientifically justified, typically through well-characterized composition data, shared manufacturing processes, or demonstrated common mechanisms of toxicity. By contrast, under the U.S. Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has historically addressed UVCBs—through the experience gained in the category-based evaluations under the High Production Volume (HPV) Challenge Program (Stanton and Kruszewski, 2016). These U.S. approaches emphasize pragmatic grouping of substances with comparable source materials and processing histories, sometimes with less reliance on precise compositional characterization than under REACH. Consequently, while both systems aim to facilitate data gap filling and reduce unnecessary testing, their regulatory acceptance criteria, evidentiary expectations, and practical implementation of read-across for UVCBs differ markedly, reflecting divergent regulatory philosophies—one emphasizing formalized justification and documentation (REACH), and the other prioritizing category pragmatism and precedent-based decision-making (TSCA).

EFSA’s read-across guidance was not considered because it explicitly excludes UVCBs from its scope, with their assessment deferred to future revisions. Nevertheless, the guidance notes that read-across may be acceptable when the manufacturing process is highly similar, as is the case for petroleum distillates. It also acknowledges the OECD guideline, which includes UVCBs within its scope.

3 Scientific rigor in read-across: criteria and considerations

This section evaluates how each framework addresses the core scientific issues that determine read-across credibility. Subsections focus on key themes (biological similarity, ADME, uncertainty, NAM/AOP integration), comparing EFSA, ECHA/RAAF, and GRAP side by side.

3.1 Establishing biological similarity and mechanistic plausibility

EFSA: The guidance defines structural and mechanistic similarity as the cornerstone for selecting source analogues. In practice, during Step 2 (Target characterization) and Step 3 (Source identification), EFSA expects assessors to gather all relevant data on the target’s physicochemical properties, toxicodynamic behavior (mode of action, key target organs, etc.), and toxicokinetics. This information shapes a hypothesis for similarity: e.g., “Target and source share a structural motif that is responsible for toxicity” or “Target metabolizes to the same reactive intermediate as Source, leading to the same adverse outcome.” EFSA’s framework encourages an iterative refinement–if during Step 4 (Source evaluation) a mechanistic dissimilarity emerges (say the source has an effect via a pathway not relevant to target), one might refine the hypothesis or select a different source. The guidance explicitly mentions the use of AOPs as a way to frame the similarity rationale. The overarching idea is that EFSA does not treat read-across as a simple structural analogy exercise; it must be biologically plausible that the substances will cause the same effects in the same way.

ECHA (RAAF): The RAAF’s assessment elements put heavy weight on mechanistic plausibility. For any scenario, one of the first elements assessed is typically: “Is the hypothesis of why the substances are expected to have similar properties explained and justified?” This means a registrant must clearly state the basis of the read-across–often a combination of structural similarity and some evidence (or logical argument) of similar mode of action or metabolism. For example, RAAF Scenario 1 (analogue approach) requires checking if the source and target share the functional group or metabolite responsible for the toxicity in question. If a structural difference exists (e.g., one analog has an extra ring or different substituent), RAAF expects an explanation of why that difference is not expected to affect toxicity–possibly by pointing to an AOP or mechanistic understanding. RAAF also distinguishes between toxicity that is explained by a known mechanism versus cases where it’s empirical but consistent; in the former, the read-across is stronger if you can articulate the mechanism (e.g., both chemicals are pro-estrogens that metabolize into an active estrogenic compound). In summary, RAAF operationalizes mechanistic similarity as a checklist item–a read-across without a mechanistic justification is likely to be deemed less robust or even unacceptable. This insistence has pushed registrants to include more biological reasoning, aligning with the GRAP philosophy.

GRAP: From the outset, GRAP has championed a shift “from structural similarity alone to biological similarity”. Zhu et al. (2016) introduced the concept of using broad biological data (e.g., high-throughput screening profiles, toxicogenomics, cell-based assays) to establish common activity between source and target chemicals. A term that arose from these efforts is “bioactivity-based read-across” (sometimes abbreviated as BaBRA), meaning one uses in vitro bioactivity signatures to group chemicals or identify analogues with similar biological profiles. This is essentially leveraging NAM data to bolster the mechanistic plausibility of read-across. GRAP publications encourage constructing an argument that includes known or hypothesized modes of action and even linking those to formal AOPs if available. For instance, if two chemicals trigger similar pathways in vitro (say both activate oxidative stress responses in cells), that can support a hypothesis that they might cause the same in vivo outcome (if that pathway is known to lead to toxicity). Additionally, in the 2020 workshop (Rovida et al., 2020), experts emphasized that demonstrating absence of unexpected “biological activity” is important if one wants to be confident in a negative prediction; this means casting a wide net for mechanistic similarity, including checking multiple endpoints or using omics to ensure no hidden differences. In practical terms, GRAP encourages assembling a mechanistic similarity weight-of-evidence: e.g., similar in vitro assay responses, similar metabolic pathways (enzyme interaction data), and any relevant in vivo info (like both cause liver toxicity in the same pattern). This multi-faceted approach to mechanistic similarity is now reflected in EFSA’s guidance (which explicitly gathers toxico-dynamic and -kinetic info) and is something RAAF implicitly rewards (a strong mechanistic case will satisfy multiple assessment elements).

3.2 Toxicokinetic and ADME considerations

EFSA: The inclusion of toxicokinetic data (ADME) is explicitly mentioned in EFSA’s workflow. In Step 2 (Target characterization), assessors are advised to compile what’s known about the target’s kinetic behavior, and similarly for sources in Step 4. EFSA highlights that differences in ADME between source and target can critically undermine a read-across if not accounted for. For example, if the source compound is poorly absorbed and therefore not toxic, but the target is well absorbed, one cannot read-across the “non-toxic” result unless additional justification is given (perhaps the target is also expected to be low in bioavailability due to some property, or the exposure scenario differs). EFSA’s guidance likely suggests conducting in vitro metabolism studies or using PBK (physiologically based kinetic) modeling as needed to compare kinetic profiles. The iterative nature of EFSA’s process means if a discrepancy in metabolism is found (say, target generates a toxic metabolite that source does not), the approach might shift–maybe exclude that source or generate more data. In short, EFSA requires proactive evaluation of ADME similarity as part of the hypothesis: the target and source should have comparably bioavailable forms at the target site of action, or differences must be quantitatively accounted for in the uncertainty analysis.

ECHA (RAAF): ADME is a recurring theme in the RAAF assessment elements. One specific assessment element (present in several scenarios) asks: “Have differences in metabolism or toxicokinetics between source and target been addressed?” The assessor will look for statements like “Both substances are metabolized via the same pathway,” or “The target has no structural features that would lead to different reactivity or bioactivation than the source.” If a registrant ignores a known kinetic difference (e.g., one is a pro-drug that needs metabolic activation and the other is not), RAAF would flag that as a major flaw. The RAAF guidance (2017) itself was written when NAM-supported ADME data were less commonly provided, but it does incorporate traditional knowledge–for instance, if source and target have significantly different molecular weight or lipophilicity, has the impact on absorption been discussed? If one is rapidly excreted and the other accumulates, how does that affect the prediction? In essence, RAAF enforces that a credible read-across must compare toxicokinetic profiles. Cases exist where ECHA accepted read-across because applicants convincingly argued kinetic similarity or adjusted their hypothesis to account for kinetic differences (one example, as reported by Ball et al., 2016, was a category of substances where bioavailability differences were used to select worst-case testing members–showing regulators do pay attention to these details).

GRAP: The GRAP initiatives identified “ADME differences as one of the most challenging issues in read-across”. In their analysis, even if two chemicals are structurally similar, differences in absorption or metabolism can lead to different toxicity outcomes, which has been a reason some read-across arguments fail. Therefore, GRAP strongly advises practitioners to deeply investigate ADME: use available tools (like in silico predictors for metabolism, in vitro hepatic clearance assays, etc.) to see if the target might behave differently inside the body than the source. If differences are found, GRAP suggests either refining the category (maybe the outlier should not be used as a source) or incorporating the difference into the prediction (for example, applying an uncertainty factor if the target might have higher internal exposure). The 2020 workshop report explicitly notes that NAMs can help with ADME–e.g., performing in vitro metabolic stability or transporter assays to compare substances. It also hints at future use of PBPK modeling fed by NAM data to quantitatively handle kinetic differences. Another GRAP concept relevant here is “toxicokinetic applicability domain” – ensuring the target lies within the domain of sources in terms of kinetics (Patlewicz et al., 2014, described the idea of local validity, which in reverse can be applied to say: if all sources share a kinetic trait, ensure target does too, or otherwise justify). Moreover, when arguing lack of toxicity via read-across, GRAP experts insist on an even more detailed ADME discussion, basically “cover all bases” to show no unaccounted toxic metabolites will appear. Summing up: GRAP pushes for comprehensive ADME evaluation, a practice that EFSA and ECHA frameworks are increasingly incorporating, thereby aligning with GRAP on this front.

3.3 Treatment of uncertainty and weight-of-evidence

EFSA: Uncertainty analysis is a distinct step (Step 6) in EFSA’s read-across workflow, underscoring how central it is. By the time one reaches this step, the guidance expects that all sources of uncertainty from previous steps have been identified and, where possible, quantified or characterized. EFSA explicitly asks whether the overall uncertainty can be reduced to tolerable levels for the decision at hand by using established approaches (e.g., applying assessment factors) or by generating additional data such as NAM outputs. In practical terms, EFSA assessors will look at uncertainties like: differences between source and target (residual questions about mechanism or kinetics), quality of the data used (is the source study reliable or does it introduce uncertainty?), and relevance of the endpoint extrapolation (e.g., read-across from subchronic to chronic toxicity might add uncertainty). The EFSA guidance likely provides a framework or at least discussion on how to document these uncertainties and perhaps an uncertainty table or narrative (see EFSA Scientific Committee general guidance on uncertainty analysis in risk assessment3). Another important aspect: EFSA’s step 1 (Problem formulation) ties into uncertainty by setting an acceptable level of uncertainty at the outset–for instance, a screening assessment might tolerate more uncertainty than a definitive risk assessment for regulatory approval. This contextual approach to uncertainty is something relatively unique in EFSA’s guidance (tailoring the rigor to the context). Finally, EFSA concludes with either accepting the read-across (if uncertainties are within acceptable bounds) or recommending filling the data gap with actual testing if uncertainties remain too high. The emphasis is on transparent communication of uncertainty so decision-makers know how much confidence to place in the read-across conclusion.

ECHA (RAAF): While RAAF does not have a separate “uncertainty” step, uncertainty is woven throughout its assessment elements. Each missing justification or unaddressed difference is essentially an uncertainty. The RAAF document uses language like “it is unclear whether … ” to signal uncertainties that would make the read-across hypothesis weaker. One might say RAAF’s grading of each element (fully addressed vs. not) is a way of qualifying uncertainty: if something is not addressed, the uncertainty in that aspect is unacceptably high. ECHA’s broader guidance on read-across (e.g., Chapter R.6 of the IR&CSA Guidance) also talks about describing uncertainties and using a weight-of-evidence approach. Weight-of-Evidence (WoE) is often how uncertainties are mitigated: if multiple independent pieces of evidence support the prediction, the uncertainty is effectively reduced. Ball et al. (2016) noted that ECHA tends to be more comfortable when read-across is part of a WoE with other data. Indeed, ECHA’s official stance (as also mirrored in OECD guidelines) is that read-across is stronger when combined with other non-test data–for example, if you have two analogues showing the same effect and also a QSAR model predicting the effect, plus perhaps some in vitro test indicating similar activity, then the total WoE is compelling even if each piece alone has uncertainty. In terms of regulatory acceptance, ECHA may accept a read-across argument with some uncertainty if the consequence of being wrong is still protective (e.g., using read-across to confirm a hazard exists might be accepted with less stringent proof than using read-across to assert safety). The EFSA guidance actually cites that point: a weaker justification might suffice to confirm hazard (since regulators default to conservative stance), but a much stronger justification is needed to conclude “no hazard” via read-across. This philosophy is shared by ECHA: declaring something non-toxic by read-across requires high confidence (low uncertainty), whereas identifying a potential hazard by read-across is more readily acceptable, since it errs on the side of caution. In summary, RAAF does not provide a quantitative uncertainty analysis framework, but by ensuring all critical questions are answered, it implicitly demands uncertainties be addressed. If not fully addressed, the case is likely rejected or requires additional data (which is effectively saying the uncertainty was too high).

GRAP: Handling uncertainty is one of GRAP’s central themes. The guidance and related papers emphasize that uncertainty should be explicitly addressed in read-across justifications. This includes acknowledging assumptions (e.g., “we assume impurity profiles of the source and target do not significantly influence toxicity–a source of uncertainty”), data variability, and knowledge gaps. GRAP recommends tools such as Klimisch scores for data reliability (Schneider et al., 2009) and describing confidence in each line of evidence. It also promotes constructing weight-of-evidence (WoE) narratives or scoring systems to balance evidence, approaches further developed in later work (e.g., EFSA Scientific Committee, 2025; R.I.V.M. uncertainty toolbox).

The 2020 Rovida workshop expands on this by proposing a categorical system (low/medium/high) to rate uncertainty across domains and recognizes RAAF’s role in highlighting these elements. Rovida et al. describe this as a “pragmatic solution,” noting that ECHA’s RAAF already captures many of these aspects, even if not labeled as formal uncertainty analysis.

Transparency is another GRAP priority: uncertainties can be acceptable if clearly communicated and the overall approach remains conservative. GRAP also advises supplementing uncertain elements with additional evidence—e.g., in vitro metabolism or mechanistic assays. By proactively addressing uncertainties, submitters strengthen their read-across cases. Overall, GRAP aligns closely with EFSA’s formal uncertainty step and complements RAAF by encouraging applicants to anticipate and mitigate issues assessors would likely flag.

3.4 Incorporation of NAMs (new approach methodologies) and AOP frameworks

EFSA: The 2025 EFSA guidance is one of the first regulatory frameworks to integrate NAM usage into the read-across process. It advocates for exploring new approach methods at multiple junctures: e.g., prior to animal testing for data gap filling (the guidance explicitly notes “new data refer to exploring NAMs first before considering any in vivo testing”, and for reducing uncertainty in various steps. EFSA’s Appendix likely provides examples of NAM integration–for instance, using in vitro bioassays to confirm that target and source elicit similar biological responses, or using computational models (QSARs, read-across tools like the OECD QSAR Toolbox4 (Kuseva et al., 2019) to identify potential analogues and predict properties. The guidance’s emphasis on “standardised approaches” includes the use of internationally recognized NAMs where available (e.g., OECD Test Guidelines for in vitro tests, validated QSAR models) to support read-across. Another modern aspect is incorporation of AOP thinking (Leist et al., 2017): by aligning the read-across hypothesis with an AOP, assessors can see that upstream key events are shared between source and target. EFSA, being a scientific risk assessor, is receptive to AOP frameworks–for example, if a read-across argument is that two pesticides cause liver toxicity through a common AOP involving PPAR-α activation, and one can show NAM evidence of both activating that pathway in vitro, that strengthens the case. In summary, EFSA’s approach not only allows but encourages NAM and AOP use to make read-across more mechanistically anchored and to avoid unnecessary animal tests. This reflects the contemporary shift in toxicology towards Next-Generation Risk Assessment (NGRA) paradigms, and EFSA is signaling that its door is open to such data.

ECHA (RAAF): At the time of RAAF’s development (2015 and 2017), NAMs were not explicitly integrated. RAAF is method-agnostic and it focuses on the quality of the justification, regardless of whether the evidence is from traditional tests or new methods. However, since RAAF is used by expert assessors, they can certainly consider NAM evidence as fulfilling certain assessment elements. For example, one assessment element might be “Is there evidence that the source and target have a similar toxicological profile?“. In classic cases this might be answered with both having, say, a positive in the same in vivo assay. But NAM data like ToxCast5 bioactivity fingerprints could also be used as evidence of similar profiles (if properly rationalized). ECHA has separately been involved in initiatives to incorporate NAMs (such as defining conditions under which in vitro or in silico can suffice), but these are often captured in guidance documents outside the RAAF (like the 2018 guidance on using in vitro/ex vivo for skin sensitization, etc.). It’s worth noting that ECHA and EFSA have collaborated on some NAM fronts (for example, EFSA’s mention of integrating NAMs likely draws from experiences in REACH and research projects like EU-ToxRisk6 (Escher et al., 2019; 2022), which involved ECHA. The RAAF’s structure does not exclude the use of NAMs. When NAM-derived data are used to fill an endpoint for a source substance, the RAAF can still be applied to assess the plausibility of the read-across; however, the registrant must demonstrate that the NAM result is valid and relevant. Noteworthy, RAAF assessors require that NAM data be explicitly linked to the toxicological endpoint being addressed and to the underlying similarity hypothesis. Ongoing discussions (as of 2025) aim to update the RAAF to better accommodate NAM-supported read-across. Regulatory uptake of NAMs remains gradual, but frameworks such as EFSA’s may help accelerate integration by providing practical examples of how mechanistic and in vitro data can be formally incorporated.

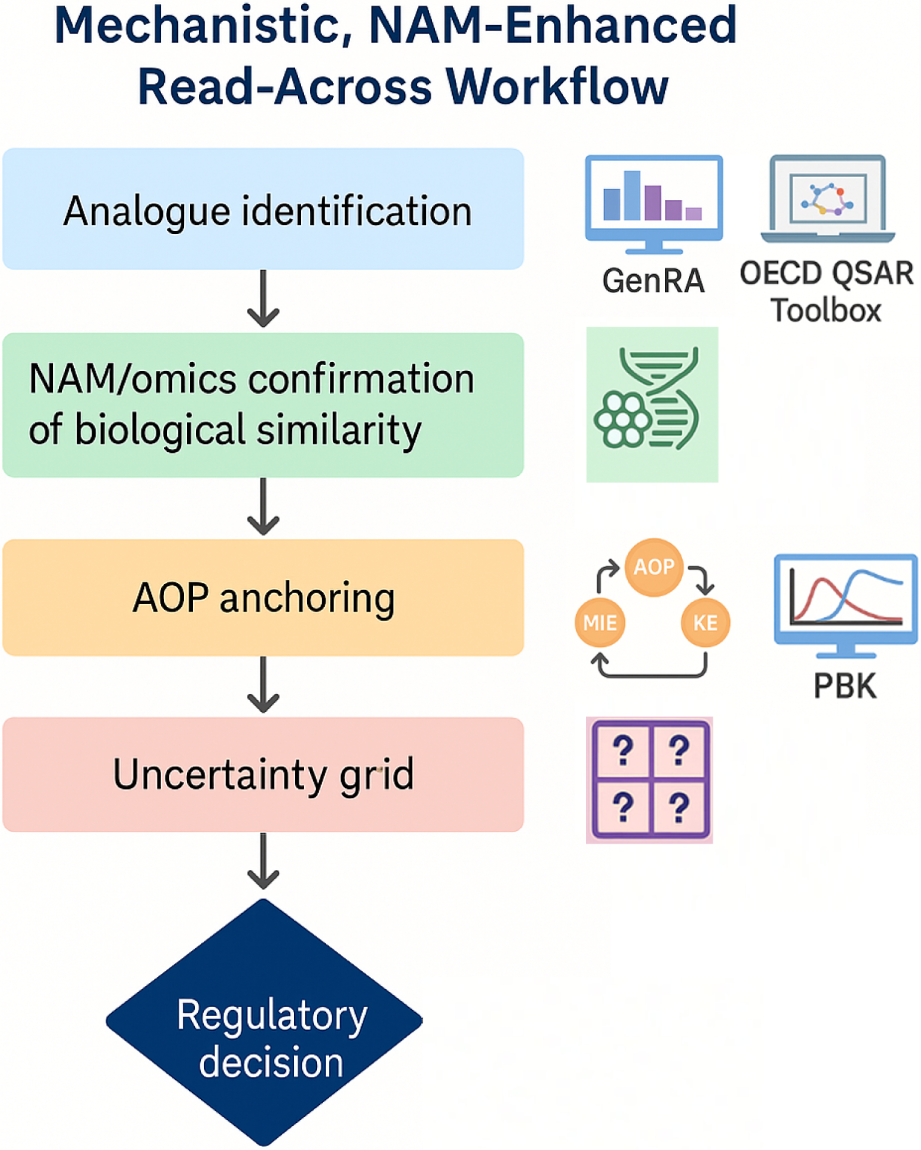

GRAP: The GRAP publications and workshops have been strong proponents of NAMs to enhance read-across. Even in 2016, GRAP discussions included how high-throughput screening data (like those from ToxCast) could identify mechanistic similarities or outliers in categories. Zhu et al. (2016) essentially provided a toolkit of NAM types (in silico predictions, in chemico assays, cell-based assays, -omics technologies) and how each could support various aspects of read-across. Fast-forward to Rovida et al. (2020): they explicitly talk about “NAM-enhanced RAx” as the next evolution. The NAM-enhanced read-across workflow from EU-ToxRisk (featured in that paper) is a concrete outcome of GRAP thinking–it formalizes adding NAM data generation into the process (e.g., after initial analog identification, perform targeted in vitro tests to confirm similarity or probe a hypothesis). GRAP sees NAMs as not just nice-to-have, but often essential for certain read-across cases, especially where traditional data are missing or when trying to demonstrate a negative (no effect) with confidence. For instance, if you want to read-across that a new food additive has no genotoxicity based on an analogue, GRAP would encourage conducting some in vitro genotoxicity screens or mechanistic assays in both compounds to bolster that argument, rather than relying solely on analogue’s in vivo result. Also, GRAP encourages the use of computational NAMs: read-across can be complemented by QSAR predictions (ensuring the target is within the applicability domain of the model) or by docking studies if relevant (say both source and target binding to the same receptor, demonstrated via modeling). In terms of AOPs, GRAP and associated efforts have frequently linked read-across case studies to AOPs to illustrate mechanistic reasoning. The concept of mechanistic applicability domain ties directly to AOPs–essentially ensuring that the chemical group defined makes sense in light of known biological pathways. By doing so, one can argue the read-across has a sound scientific foundation rather than being a blind correlation.

Summary Alignment: All three approaches are increasingly convergent here: EFSA explicitly instructs the use of NAMs/AOPs, ECHA (via RAAF) implicitly accepts them if they strengthen the case, and GRAP has been advocating for them from the start. This alignment is a positive trend–indicating a collective move in toxicology toward modern, mechanism-based safety assessment. Rovida et al. (2020) see NAMs as “the most important innovations to improve acceptability of RAx”, reflecting the consensus in the community that this is the way forward. Confirmation arrived also from a meeting organized by the EU-ToxRisk project, which convened representatives from regulatory institutions and representatives of the industry to discuss how NAMs can be applied to improve acceptability of read-across, by providing experimental justification of similarity (Rovida et al., 2021).

4 Practical implementation and guidance usability

This section compares how each framework handles the “on-the-ground” aspects of applying read-across. It covers the availability of case studies and examples, any tools or templates provided to users, the level of detail and user-friendliness of each guidance, and overall clarity.

4.1 Use of case studies and examples

EFSA: The 2025 EFSA guidance includes or is accompanied by examples to help users understand application. Within the guidance document itself, EFSA might use illustrative examples in appendices or figures–e.g., a figure showing possible situations where read-across can be applied in EFSA’s remit (like regulated products vs. contaminants) and a figure outlining the stepwise process with an example flow. These examples serve to clarify abstract concepts (like what a good source substance evaluation looks like, or how to report uncertainty). The presence of case studies indicates EFSA’s intent to make the guidance practical and didactic, not just theoretical. It’s likely that EFSA drew on cross-sector experience (REACH cases, pesticide assessments, etc.) to shape scenarios relevant to food safety (for example, reading across toxicity from a well-studied flavor chemical to a newly proposed flavor with similar structure). By providing examples, EFSA lowers the barrier for applicants to attempt read-across, because they can model their approach on successful templates.

ECHA (RAAF): In the original RAAF documentation, ECHA provided generic scenario descriptions and included simplified case illustrations for each scenario type. Additionally, since RAAF’s release, various supporting materials have been developed. For example, the OECD QSAR Toolbox4 (a tool widely used for read-across) has built-in guidance for identifying the applicable RAAF scenario and prompts related to those assessment elements. There are also webinars and published case studies demonstrating how to construct a read-across that passes RAAF scrutiny. In literature, retrospective analyses of REACH dossiers (e.g., “A Systematic Analysis of Read-Across Adaptations … ” or specific case analysis papers) effectively act as case studies highlighting why certain read-across proposals succeeded or failed. So while ECHA’s RAAF document itself might not be as tutorial in style as EFSA’s guidance, the community around it (including ECHA’s own publications and third-party guidance) has generated many examples. Notably, ECHA sometimes publishes illustrative decisions or reports (anonymized) – these show, for example, an instance of Scenario four category that was accepted, and what the key reasoning was. The article can mention that industry also contributed to case studies: e.g., ECETOC’s case study reports7, or the OECD’s series of read-across case studies8, many of which involve European regulators. These case studies often reference RAAF in evaluating the outcome. Thus, for a practitioner, resources exist to see how a case similar to theirs was handled. The RAAF framework’s strength is that if you know your situation fits, say, Scenario 3, you can consult published examples of Scenario three read-across to guide your own.

GRAP: The GRAP publications were rich in examples by design. Ball et al. (2016) reviewed ECHA’s decisions on actual dossiers to draw lessons–effectively summarizing dozens of cases in terms of what went right or wrong. Zhu et al. (2016) likely presented example uses of biological data to support read-across (perhaps showing how a toxicity pathway was confirmed in both source and target by in vitro tests). Moreover, GRAP was not just papers–it included two workshops (Chesnut et al., 2018; Rovida et al., 2020) where participants, including regulators, discussed case studies in depth. The 2020 Rovida workshop also collated case study insights on an international scale (bringing in examples from different regulatory regimes like cosmetics, pharma, etc.). Additionally, GRAP thinking has been demonstrated in projects like EU-ToxRisk, which published case study papers (some referenced in Rovida et al., 2020) showcasing NAM-supported read-across in practice (Rovida et al., 2021). All this to say, practical demonstration has been a key part of GRAP–the concept is grounded in learning from real examples. By comparing, EFSA’s foray into read-across is recent and will benefit from these existing examples, whereas GRAP compiled them to push the field forward. Hopefully, EFSA continues to gather and publish case studies as the guidance is implemented, similar to how REACH has built a knowledge base of cases over time.

4.2 Tools and templates for implementation

EFSA: The 2025 EFSA guidance provides a structured, seven-step framework for conducting and documenting read-across in food and feed safety assessment. These steps—ranging from problem formulation to conclusion and reporting—are intended to be followed in sequence and serve as the backbone of a well-documented justification. EFSA expects that each step be addressed in the final report, effectively functioning as a de facto template for applicants. For instance, Step 1 (Problem Formulation) calls for defining the regulatory context, hazard endpoint, and acceptable uncertainty; Step 2 (Target Characterization) requires compiling all relevant identity, physicochemical, and toxicity data for the target substance; and Step 3 (Analogue Identification) involves presenting the criteria and process for selecting appropriate source substances. This structured format promotes transparency, consistency, and scientific traceability.

To support systematic documentation, the guidance encourages the use of tabular tools such as data matrices to compare target and source substances and highlight data gaps. It also includes a dedicated template for uncertainty assessment (Appendix C), based on EFSA’s broader uncertainty guidance, allowing users to categorize uncertainties and evaluate their impact on the read-across conclusion. While EFSA does not provide a stand-alone “read-across report template” or IT interface, it explicitly recommends the use of established tools—such as the OECD QSAR Toolbox—for identifying analogues and compiling supporting data. These tools help facilitate reproducible analogue selection and provide structured formats for data analysis.

The guidance does not contain sector-specific reporting templates for individual regulatory domains (e.g., food additives or pesticides), but it is intended to be broadly applicable across food and feed safety areas. Applicants are expected to integrate the read-across framework into their respective submission formats. Overall, EFSA’s guidance contributes significantly to harmonizing and strengthening the read-across process by providing a clear procedural roadmap, emphasizing comprehensive documentation, and aligning the scientific justification with established principles of uncertainty analysis and weight-of-evidence reasoning.

ECHA: ECHA’s primary contribution to read-across practice has been the RAAF document, which functions as a rigorous evaluation framework rather than a fill-in template. The RAAF (first introduced in 2015 and updated in 2017) defines six scenario-specific approaches (two analogue-based and four category-based) and outlines the critical scientific elements that a valid read-across justification must address. These elements cover key aspects like establishing chemical and mechanistic similarity between source and target, articulating a clear read-across hypothesis, demonstrating data adequacy, and accounting for uncertainties. Notably, RAAF provides high-level principles and a checklist of questions for assessors, but it does not prescribe a reporting format or step-by-step template for registrants. In practice, companies registering chemicals under REACH have translated RAAF’s requirements into their own internal templates. A typical REACH read-across justification document will mirror RAAF’s evaluation criteria and ensure that all necessary evidence is presented for ECHA’s review. ECHA’s IUCLID software, used for dossier submissions, explicitly includes fields for read-across justification in each endpoint record. Registrants must identify analogues and provide a scientific rationale in these fields, guided by ECHA’s instructions (e.g., describing analogue identity, toxicological similarity, etc.). Indeed, ECHA’s technical completeness check will flag a dossier if an endpoint is waived by read-across without an adequate justification text or identified source substances, underscoring that such documentation is mandatory. Tools have also evolved to support the assembly of read-across justifications: for example, the OECD QSAR Toolbox incorporates the RAAF logic, prompting users to select the appropriate RAAF scenario and listing the information needed for that scenario. In summary, while EFSA is now proposing a brand-new formal template, ECHA’s framework comes with a decade of hard-won experience. This has yielded many “informal” templates and digital workflows aimed at satisfying RAAF’s requirements and achieving regulatory acceptance. One persistent gap has been the absence of a publicly available standard template issued by regulators; nonetheless, the strong alignment between EFSA’s stepwise template and ECHA’s RAAF criteria hints at a future convergence, where a common read-across report format might serve both agencies’ need.

GRAP: The GRAP initiative provides a set of guiding principles for crafting scientifically robust read-across justifications. Unlike EFSA’s or ECHA’s formal submission frameworks, GRAP is not tied to a specific dossier format; instead, it outlines the components that any well-founded read-across argument should contain. Key recommendations from GRAP closely parallel the expectations of regulators. For instance, a read-across justification should begin with a clear statement of the read-across hypothesis (the toxicological rationale linking source and target substances) and thoroughly document the analogue selection process. All potential source chemicals should be considered and the reasons for including or excluding each should be transparently reported to avoid any perception of “cherry-picking” data. GRAP emphasizes comprehensive data gathering for each analogue, covering the spectrum of relevant endpoints–especially critical if one is trying to demonstrate an absence of hazard. Any differences or inconsistencies in data between source and target must be openly discussed. In fact, an analysis of ECHA dossier failures showed that the most common reasons for read-across rejections were exactly issues that GRAP seeks to prevent insufficient supporting evidence, poorly justified similarity arguments, and inadequate substance identity characterization. To address such pitfalls, GRAP guidelines enumerate fundamental elements that should underpin every read-across justification: unambiguous identification of both target and source substances, a mechanistic explanation linking chemical structure to the predicted effect, a robust and unbiased dataset supporting the hazard prediction, and an explicit accounting of uncertainties. These tenets map closely to the criteria in ECHA’s RAAF and the content of EFSA’s template, meaning that following GRAP’s advice inherently moves a practitioner toward fulfilling both agencies’ requirements.

Over the years, experts involved in GRAP have also proposed more structured ways to document read-across, moving toward a standardized “read-across report” format. For example, some have suggested creating a formal Read-Across Assessment Report analogous to a QSAR Prediction Reporting Format (QPRF), with predefined sections to ensure completeness and reproducibility of the rationale. The GRAP workshops and subsequent publications introduced tools to improve clarity and transparency, such as visualizing chemical similarity relationships (e.g., using dendrograms or heatmaps of bioactivity) and tabulating side-by-side comparisons of source and target data, so that regulators can easily inspect trends and gaps in the read-across argument. Although GRAP itself did not issue an official template document, it effectively laid the blueprint that both ECHA and EFSA have built upon. In line with GRAP’s concepts, the EU-ToxRisk research program has been developing a next-generation “RAx” guidance aiming to integrate NAMs into read-across justification. This forthcoming guidance–worked out by a consortium of industry, academic, and regulatory experts–is expected to recommend a harmonized reporting structure for read-across that accommodates novel data streams (in vitro assays, -omics, etc.) alongside conventional toxicity data. Indeed, GRAP highlighted the value of structured reporting and even called for publicly available templates and example cases to help practitioners achieve regulatory compliance. A logical recommendation arising from these efforts is the creation of a unified template that merges the strengths of all three approaches: EFSA’s stepwise narrative, ECHA’s RAAF-based checkpoints, and GRAP’s emphasis on comprehensive evidence and clear reasoning. In practice, a scientist who follows the GRAP guidance when assembling a read-across case will likely satisfy the content requirements of EFSA’s template and address ECHA’s RAAF evaluation criteria by default. The convergence of GRAP’s best practices with regulatory frameworks ultimately improves the credibility and acceptance of read-across, steering the field toward a more standardized and transparent future.

4.3 Level of detail and clarity of guidance

EFSA: The Bennekou et al. (2025) guidance is notable for its clarity and completeness, spanning more than 60 pages and systematically detailing each of the seven steps in the read-across workflow. It offers comprehensive explanations of key concepts—such as problem formulation, toxicokinetic and dynamic similarity, and the tolerability of uncertainty—and provides structured expectations for documentation at each stage. By embedding complex topics such as NAM integration and uncertainty quantification within a sequential framework, EFSA ensures that even relatively unfamiliar readers can follow the process step by step. This pedagogical design reflects EFSA’s recognition of its broad stakeholder audience, which includes applicants from the food and feed sectors who may have limited experience with read-across methodologies. The guidance frequently reiterates principles of scientific transparency and impartiality, encouraging applicants to present information in a manner that is not only robust but also independently reproducible. Although the level of detail may appear daunting to some, the document’s structure—augmented by narrative explanations, tabulated summaries, and an appended uncertainty assessment template—supports user navigation and practical application. The clarity of the guidance benefited from a prior round of public consultation and an expert stakeholder workshop in early 2025, which helped refine its terminology and address interpretative ambiguities. In sum, EFSA has achieved a rare balance of procedural precision and scientific nuance, creating a document that is both instructive and operationally relevant.

ECHA (RAAF): In contrast, the ECHA RAAF provides a shorter but more technical framework focused primarily on evaluation. It is composed of a core ∼30-page document and supporting appendices, organized around six scenario types and their associated Assessment Elements (AEs). Each scenario outlines the structure of the read-across to be assessed (e.g., one-to-one analogue vs. category-based prediction), and each AE poses specific questions that an evaluator must answer—for instance, whether the similarity rationale is clearly established or whether uncertainties are adequately addressed. This format offers clarity to experienced evaluators but may appear opaque to newcomers, particularly as it provides minimal guidance on how to actually construct the read-across argument. The RAAF assumes familiarity with underlying toxicological concepts and does not define terms like “common mode of action” or “toxicokinetic similarity,” which may limit accessibility for less experienced users. Supplementary documents, including illustrative examples and explanatory notes, have gradually improved usability, as has the broader context provided by ECHA’s IR&CSA Chapter R.6 guidance9. Nevertheless, users must often triangulate multiple documents to obtain a full understanding of read-across expectations under REACH. This fragmented structure contrasts with EFSA’s consolidated format, making RAAF potentially more challenging to navigate despite its conceptual precision. Still, its logical design and scenario-driven rigor are widely appreciated by practitioners familiar with the REACH regime, and its alignment with formal IUCLID fields and regulatory workflows lends practical coherence to the read-across assessment process.

GRAP: The GRAP publications, beginning with Ball et al. (2016) and Zhu et al. (2016), offer a different type of clarity—one based not on regulatory prescription, but on conceptual guidance and scientific rationale. These documents, published in narrative style aim to educate rather than mandate. They define the major challenges in constructing defensible read-across cases—such as inadequately justified analogue selection, failure to consider biological similarity, or unacknowledged uncertainty—and then propose solutions grounded in best scientific practices. GRAP does not prescribe a specific reporting format but provides detailed examples, tables, and checklists that can serve as de facto templates for practitioners. For instance, Ball et al. outline essential components such as a clearly articulated hypothesis, systematic analogue identification, robust weight-of-evidence construction, and transparent communication of assumptions and uncertainties. The clarity of GRAP lies in its accessibility: it uses plain scientific language, abundant references, and illustrative case discussions to make complex issues understandable, even for those new to regulatory read-across. While it lacks the procedural authority of EFSA or ECHA documents, it fills a critical pedagogical role by explaining why each element matters and how it can be addressed using evolving tools and data types—including NAMs, AOPs, and in silico approaches. This makes GRAP an indispensable resource for improving scientific literacy and reasoning among both applicants and assessors.

Taken together, the three frameworks differ in their orientation but are complementary in practice. EFSA’s guidance tells applicants what to do and how to report it; ECHA’s RAAF explains what regulators will check and why it matters; and GRAP articulates why the underlying science must be rigorous and transparent. By combining EFSA’s procedural roadmap with RAAF’s evaluation logic and GRAP’s conceptual insights, practitioners can assemble scientifically credible and regulatorily compliant read-across arguments. The growing convergence among these sources, particularly around principles of biological similarity, transparency, and uncertainty analysis, suggests an opportunity for future harmonization of guidance that supports both scientific innovation and regulatory clarity.

5 Regulatory acceptance and impact