Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a complex neurodegenerative condition and the leading cause of dementia worldwide. Treatments that safely and effectively counteract disease progression are currently lacking. While the formation of amyloid plaques has long been considered the leading hypothesis of disease onset, growing evidence suggests that the emergence of AD could be driven by a combination of underlying factors that promote chronic neuroinflammation, including pathogenic infections, environmental toxicants, and disruptions along the gut-brain axis. Traditional nonclinical models of AD, such as monolayer cell cultures and transgenic mice, struggle to capture the complexity of the disease as it occurs in humans. Human-centered complex in vitro models (CIVMs), including cerebral organoids and microfluidic organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technologies, provide greater physiological relevance by more closely recapitulating key cellular and molecular features of the human brain and disease mechanisms. In this mini review, we evaluate recent advances in CIVMs and how they are being leveraged to investigate emerging hypotheses of AD etiology. Cerebral organoids and OOC platforms can consistently replicate neuropathological hallmarks of neurodegeneration in response to pathogenic or environmental insults, including blood-brain barrier disruption, amyloid-β accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and glial activation. We also highlight early efforts to model the gut–brain axis using organoid and multi-OOC systems, demonstrating how microbiota-derived factors can affect neural processes. Collectively, these studies show that human-centered CIVMs can be applied to both recreate and mechanistically disentangle interrelated pathological processes to an extent beyond that afforded by animal models, thus offering new opportunities to identify causal mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

1 Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) remains one of the most prevalent neurological disorders worldwide, accounting for 60%–70% of all dementia cases1. In 2021, an estimated 57 million people were living with dementia, with this figure being projected to nearly double every 20 years2.

Despite significant investment in basic and translational research, treatments that effectively and safely act on the evolution of the disease are currently lacking. Available drugs such as N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists (memantine) and cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) are largely symptomatic and do not suppress disease progression. Since 2021, the first anti-amyloid antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab, donanemab) have been approved to target amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques, a pathological hallmark of AD3. These are considered disease-modifying therapies as they can slow cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia due to AD, but are associated with significant risks, including brain swelling and bleeding4.

The heterogeneity of patients and absence of reliable early diagnostic biomarkers hinder progress, as demonstrated by age-related shifts in Aβ positivity (Young and Mormino, 2022). Adding to the complexity, AD is a highly multifaceted condition, varying in age of onset, genetic risk factors, pathological processes and progression patterns, as well as the presence of comorbidities (Duara and Barker, 2022). This diversity makes it unlikely that treatments aimed at a single target will be effective across the entire patient population.

Over the past 15 years, new hypotheses beyond the amyloid cascade have emerged to explain the complex etiopathology of AD (Zhang et al., 2024). Several are interrelated, with dysfunctional metabolism, chronic inflammation, and environmental factors playing a critical role, along with ageing and genetics. These hypotheses include: (i) systemic inflammation caused by pathogen infections (Seaks and Wilcock, 2020; Bruno et al., 2023; Brown and Heneka, 2024), (ii) the impact of long-term exposure to environmental pollutants (Dhapola et al., 2024), and (iii) the role of microbiota and gut dysbiosis in the induction of neuroinflammation through the gut-brain axis (GBA) (Logan et al., 2023; Seo and Holtzman, 2024; Dhanawat et al., 2025).

Traditional nonclinical models of AD have relied on both in vivo and in vitro models that replicate key disease hallmarks. Transgenic mice that express genetic variants identified in familial AD (Zhong et al., 2024) can develop amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles, gliosis, and mild cognitive deficits. Yet, even with amyloid accumulation, they frequently fail to show significant neuronal loss (Sanchez-Varo et al., 2022). Moreover, animal models do not replicate disease pathogenesis as it occurs in humans (Veening-Griffioen et al., 2019), failing to develop the comorbidities and risk factors commonly associated with sporadic, late-onset AD (Marshall et al., 2023). Even with optimized or humanized animal models, inherent interspecies differences in metabolism, gut microbiome, immune function, and epigenetic regulation considerably limit their external validity (Pound and Ritskes-Hoitinga, 2018). The inadequacy of traditional research models, coupled with their design being grounded in flawed or reductionist theories of disease etiology, has likely contributed to hindering a full understanding of disease complexity and played a relevant role in AD drug development failures.

In recent years, the use of human-centered complex in vitro models (CIVMs) such as cerebral organoids and organ-on-a-chip (OOC) systems, often derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) or primary cells, have deepened our understanding of AD pathology. CIVMs offer improved physiological relevance over traditional 2D monolayer cell cultures and animal models by better mimicking the complexities of the human brain and disease processes (Sreenivasamurthy et al., 2023; Dolciotti et al., 2025). Although 2D models have contributed significantly to AD research and remain widely used, they fall outside the scope of this review, which focuses on CIVMs that recapitulate multicellular and microenvironmental features more comprehensively. Furthermore, patient-derived CIVMs can be used to study individual differences in disease progression and response to treatment, possibly informing personalized medicine approaches (Lopes and Guil-Guerrero, 2025). These human-centered platforms can also be leveraged to explore novel etiological hypotheses underlying AD onset and to elucidate their potential interconnections.

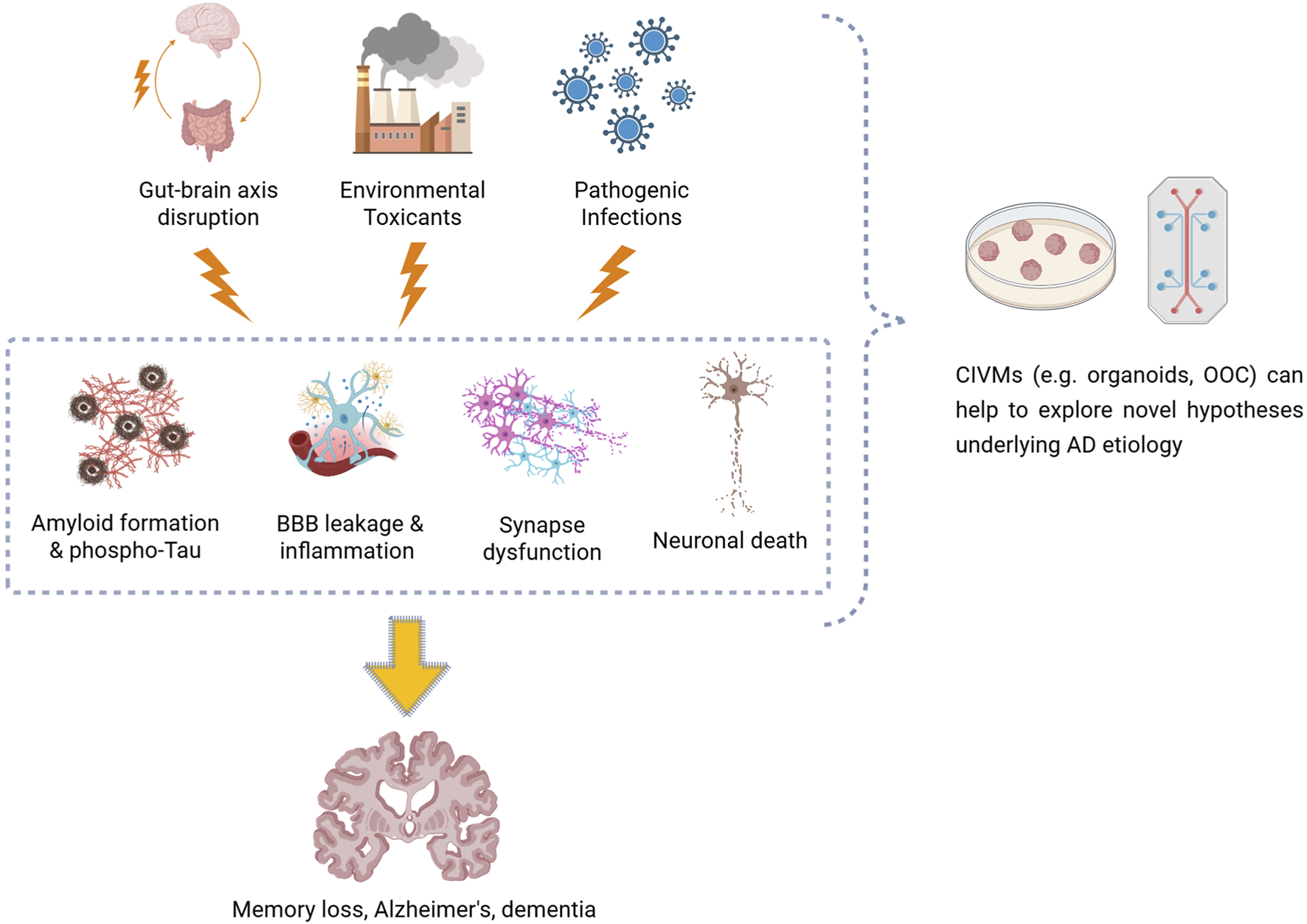

In this mini review, we highlight recent applications of human-centered CIVMs (Figure 1), particularly cerebral organoids and single- or multi-OOC systems, and how they have been applied to investigate: (i) the potential impact of pathogen infections on neuroinflammation and AD; (ii) the effects of environmental pollutants on neurodegeneration and AD risk; and (iii) how alteration of gut microbiota and the GBA may drive neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in AD. Together, these CIVM-based studies (summarized in Table 1) offer valuable human-relevant insights into AD pathogenesis, helping to uncover disease mechanisms and identify potential therapeutic targets.

FIGURE 1

Diagram illustrating how gut–brain axis disruption, environmental toxicants, and pathogen infections could contribute to the development of Alzheimer’s disease–related neuropathology, such as amyloid plaque formation, neurofibrillary tau tangles, blood–brain barrier leakage, neuroinflammation, synaptic dysfunction, and neuronal loss. Complex in vitro models, including brain organoids and organ-on-a-chip systems, enable these mechanisms to be replicated and studied under controlled and human-relevant conditions.

TABLE 1

| CIVM | Operating principles | Cellular composition | Treatment | Key effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Pathogen-related factors | |||||

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HIV-1 |

|

Boreland et al. (2024) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HIV-1 |

|

Dos Reis et al. (2020) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HIV-1 |

|

Kong et al. (2024) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HIV-1 |

|

Martinez-Meza et al. (2025) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HIV-1 |

|

Narasipura et al. (2025) |

| Cortical organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Abrahamson et al. (2021) |

| Cortical brain tissue model (3D) |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Cairns et al. (2020) |

| Brain–like tissue model (3D) |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Cairns et al. (2025) |

| Neuronal cell culture (3D) |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Eimer et al. (2018) |

| Forebrain organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Ijezie et al. (2024) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Oh et al. (2025) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Qiao et al. (2020) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Qiao et al. (2022) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

HSV-1 |

|

Sundstrom et al. (2024) |

| BBB + neurovascular unit-on-a-chip |

|

|

|

|

Zhang et al. (2025) |

| Cortical organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Andrews et al. (2022) |

| Cortical organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Colinet et al. (2025) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Kase et al. (2023) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Kong et al. (2022) |

| Assembloid (cortical + blood vessel organoids) |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Kong et al. (2023) |

| Cortical organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

McMahon et al. (2021) |

| Brain organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Ramani et al. (2020) |

| Brain organoid |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 |

|

Samudyata et al. (2022) |

| BBB-on-a-chip |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 (S1 and S2 subunits) |

|

Buzhdygan et al. (2020) |

| BBB-on-a-chip |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 (S1 subunit) |

|

DeOre et al. (2021) |

| BBB-on-a-chip |

|

|

SARS-CoV-2 envelope (S2E) protein |

|

Ju et al. (2022) |

| BBB + neurovascular unit-on-a-chip |

|

|

TNF-α LPS IL-1β |

|

Brown et al. (2016) |

| BBB-on-a-chip |

|

|

TNF-α |

|

Griep et al. (2013) |

| BBB + neurovascular unit-on-a-chip |

|

|

TNF-α |

|

Pediaditakis et al. (2022) |

| BBB + neurovascular unit-on-a-chip |

|

|

TNF-α IL-1β IL-8 |

|

Vatine et al. (2019) |

| BrainSphere |

|

|

Zika virus Dengue virus Flavivirus |

|

Abreu et al. (2018) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

Zika virus |

|

Lee et al. (2022) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

Zika virus |

|

Xu et al. (2021) |

|

|||||

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

Cadmium |

|

Huang et al. (2021) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

DPM |

|

Park and Choi (2023) |

| Brain-on-a-chip |

|

|

DPM |

|

Kang et al. (2021) |

| Brain-on-a-chip |

|

|

DPM |

|

Seo et al. (2023) |

| BBB-on-a-chip |

|

|

Indoor nanoscale PM |

|

Li et al. (2019) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

Microplastics |

|

Park et al. (2025) |

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

PFAS |

|

Lu et al. (2024) |

| (3) Gut-brain axis and microbiota-related factors | |||||

| Cerebral organoid |

|

|

Pathogenic microbiota |

|

Isik et al. (2025) |

| GBA-on-a-chip |

|

|

Probiotic gut microbe-derived metabolites and exosomes |

|

Kim et al. (2024) |

Summary of studies using complex in vitro models (CIVMs) to investigate (1) pathogenic, (2) environmental, and (3) gut-brain axis mechanisms relevant to Alzheimer’s disease.

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; BBB, blood-brain barrier; DPM, diesel particulate matter; GBA, gut-brain axis; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; hiPSC, human induced pluripotent stem cell; HIV-1, human immunodeficiency virus type 1; hNSC, human neural stem cell; HSV-1, human simplex virus type 1; NPCs, neural progenitor cells; PEGDMA, poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate; PFAS, Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances; PM, particulate matter; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; ZIKV, zika virus.

2 CIVMs to explore novel Alzheimer’s disease etiological hypotheses and risk factors

2.1 CIVMs to explore the impact of pathogen infections on neuroinflammation and AD

The infectious hypothesis posits that pathogens such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi can enter or persist within the central nervous system by crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and eliciting an immune response. Growing evidence suggests that pathogenic infections may contribute to AD pathogenesis by triggering or exacerbating neuroinflammatory responses that eventually develop chronicity, with subsequent microglial dysfunction leading to synaptic loss, neuronal death, and overall cognitive decline (Seaks and Wilcock, 2020; Catumbela et al., 2023). Multiple studies suggest that Aβ itself may function as an antimicrobial peptide by forming aggregates which entrap invading pathogens (Kumar et al., 2016; Gosztyla et al., 2018; Prosswimmer et al., 2024). Amyloidogenicity could subsequently emerge as plaque accumulation outstrips the microglial capacity for clearance, which naturally declines with ageing.

Organoids comprising neurons and glia display robust astrocytic and microglial activation upon exposure to viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (Dos Reis et al., 2020; Boreland et al., 2024; Kong et al., 2024; Martinez-Meza et al., 2025; Narasipura et al., 2025), human simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (Cairns et al., 2020; Qiao et al., 2020; Qiao et al., 2022; Sundstrom et al., 2024), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Andrews et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2023; Colinet et al., 2025), and Zika virus (ZIKV) (Abreu et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2021), leading to the upregulation of innate immune signaling pathways and increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

Viral infection can also replicate key neuropathological hallmarks of AD in 3D human brain organoids, including increased Aβ accumulation and tau phosphorylation, as seen in HSV-1 (Abrahamson et al., 2021; Ijezie et al., 2024; Cairns et al., 2025; Oh et al., 2025) and ZIKV (Lee et al., 2022) treatments. Additionally, Aβ oligomers bind to HSV-1 surface glycoproteins, leading to increased Aβ production and HSV-1 entrapment (Eimer et al., 2018). In SARS-CoV-2, glia are the predominantly infected cell type in human brain organoids (McMahon et al., 2021; Kase et al., 2023), with microglia-mediated synaptic engulfment increasing by threefold (Samudyata et al., 2022). Neuronal tau hyperphosphorylation and translocation to the soma is also observed (Ramani et al., 2020), highlighting how organoid models can be leveraged to disentangle the cellular and molecular mechanisms of viral infection in the human brain and its potential role in AD onset.

Microfluidic systems have become effective for modeling the BBB under physiologically relevant conditions by recapitulating key biomechanical properties such as flow rate, fluidic shear stress, and the formation of endothelial tight junctions (Shin et al., 2019). Due to their capacity for triggering neuroinflammatory responses, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) are commonly used stimuli to mimic aspects of infection in vitro. In brain-on-a-chip models of the BBB, both have been associated with increased permeabilization. LPS treatment reduces the prevalence of tight junctions (Brown et al., 2016), whereas TNF-α alters the expression of endothelial tight junction markers (Vatine et al., 2019), decreases transendothelial electrical resistance by around tenfold (Griep et al., 2013), and increases cytokine production, all of which contribute to BBB leakage (Pediaditakis et al., 2022). Importantly, BBB damage and impaired cerebral blood flow have been described as early pathological hallmarks of neurodegeneration leading to AD (Nortley et al., 2019; Sousa et al., 2023).

HSV-1 infection of co-cultured human microvascular endothelial cells, astrocytes, microglia, and neurons within a multi-compartment chip induced increased BBB permeability, pro-inflammatory cytokine production, and neuron-glia apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2025). Similarly, SARS-CoV-2 infection perturbs BBB homeostasis, reducing the viability of neurovascular cells and eliciting prolonged pro-inflammatory responses (Buzhdygan et al., 2020; DeOre et al., 2021; Ju et al., 2022). Human brain-on-a-chip systems are also suitable for evaluating antiviral therapeutics (Shin et al., 2019; Boghdeh et al., 2022), some of which may hold potential for AD treatment (Iqbal et al., 2020; Drinkall et al., 2025).

2.2 CIVMs to explore the impact of environmental pollutants on neurodegeneration and AD

Environmental toxicants such as air, water, and soil pollutants are globally pervasive, with chronic human exposure posing considerable risks to long-term neurological health (Nabi and Tabassum, 2022). Evidence from both in vitro and in vivo studies has demonstrated their ability to disrupt neural cell homeostasis (Iqubal et al., 2020). The accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau and Aβ is also observed across multiple studies, suggesting that chronic toxicant-induced neuropathology may contribute to the development of AD (Dhapola et al., 2024). Given the complexity and underlying interrelatedness of these adverse cellular events, CIVMs offer a human-relevant platform for mechanistically unraveling how environmental toxicants contribute to neurodegenerative processes. Examples of studies examining the neurotoxic and neurodegenerative effects of some well-known environmental pollutants in neuronal and glial CIVMs are reported in this section.

Cadmium, a common heavy metal pollutant in industrial emissions and phosphate fertilizers, induces an acute neuroinflammatory response in human embryonic stem cell (hESC)-derived brain organoids, evidenced by widespread glial activation and increased IL-6 production (Huang et al., 2021).

Diesel particulate matter (DPM) is a major ambient air pollutant produced by combustion engines, with hiPSC-derived brain organoid exposure resulting in altered neuronal electrophysiological signaling, synaptic damage, and increases in inflammatory markers (Park and Choi, 2023), all of which have been associated with AD (Nordengen et al., 2019; Meftah and Gan, 2023).

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as ‘forever chemicals’, consist of over 7 million synthetic organofluorine compounds that are widely used to enhance the water-, grease-, and heat-resistance of commercial and industrial products. They have become pervasive in global water sources, with some retaining a half-life of over 8 years within the human body (Buck et al., 2011). Chronic PFAS exposure in hESC-derived cerebral organoids over 35–70 days increased both tau phosphorylation and Aβ accumulation (Lu et al., 2024).

Lastly, the ubiquity of microplastics in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems has become a topic of global interest, raising questions about their potential neurotoxicity. Exposure of hiPSC-derived brain organoids to microplastic beads (50–100 μm) over 3 weeks significantly reduced cellular viability and cholinergic-related acetylcholine levels, indicating disrupted neuronal signaling and potential synaptic dysfunction (Park et al., 2025).

Environmental toxicants can also be incorporated into microfluidic “brain-on-a-chip” systems to investigate their neuropathological mechanisms. In models comprising human brain endothelial cells, neurons, and glia, DPM exposure induced tau hyperphosphorylation, Aβ accumulation, neuronal cell death and astrogliosis, along with microglial activation and overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Kang et al., 2021; Seo et al., 2023).

With people in developed countries typically spending 80%–90% of their time indoors, indoor airborne particulate matter (PM) also constitutes an important source of chronic pollutant exposure (Duffield and Bunn, 2023). Li et al. (2019) treated a human BBB-on-a-chip model comprising astrocytes and endothelial cells with indoor nanoscale PM retrieved from non-smoking residences in Wuhan, China. They demonstrated that indoor nanoscale PM traversed the endothelial barrier before inducing abnormal astrocytic proliferation and elevated ROS production, while also reducing overall cellular viability. This highlights the alarming effects that ambient indoor PM exposure can have on the development of chronic neuroinflammation.

2.3 CIVMs to explore the impact of microbiota and gut-brain axis alteration on AD onset

The GBA is a bidirectional communication network that links the central nervous system with the enteric nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, and gut microbiota. Signaling occurs via metabolic, immune, and neural pathways, with homeostasis across the GBA underpinning normal physiological function (Cryan et al., 2019). GBA disruption can arise through microbial dysbiosis, such as increases in pro-inflammatory bacterial taxa (Ashique et al., 2024), and has been increasingly linked to neurodegenerative processes including neuroinflammation, Aβ deposition, and tau pathology (Wang et al., 2014; Erny et al., 2015; Seo and Holtzman, 2024).

The implementation of 3D human brain organoids to model the GBA remains in its infancy. One promising strategy involves using transwell systems, which allow for vesicle trafficking and molecular diffusion across a semi-permeable membrane (Alam et al., 2024). The co-culture of hiPSC-derived brain organoids and pooled pathogenic microbiota led to reduced neuronal viability, upregulation of AD-associated genes, and disruption of the organoid’s structural integrity (Isik et al., 2025), reflecting how gut dysbiosis may promote neurodegeneration. Other proposed organoid-based GBA models include the direct exposure of cerebral organoids to gut microbiota-conditioned medium, or co-culturing cerebral and intestinal organoids within transwell systems separated by an endothelial cell layer to mimic the BBB (Alam et al., 2024).

Single- and multi-OOC microfluidic systems are increasingly being applied to model the GBA, with the European Research Council-funded MINERVA project (grant agreement ID: 724734) representing a major milestone. The project integrated five interconnected hiPSC-derived OOC modules (microbiota, gut epithelium, immune system, BBB, and brain) to recapitulate communication along the GBA (Raimondi et al., 2019). Other microfluidic models using human-derived cells have also been established to study exosomal transport across the BBB (Kim et al., 2021; Seo et al., 2024). Notably, exosomes and metabolites derived from probiotic Lactobacillus casei and L. plantarum bacteria were shown to promote synaptic plasticity, suggesting the therapeutic potential of microbiota-derived factors in mitigating neurodegenerative processes (Kim et al., 2024). Although direct applications to AD-related mechanisms have been limited, these microfluidic GBA platforms have laid the foundations for investigating microbiota-mediated mechanisms of neuroinflammation and amyloidogenicity under controlled and human-relevant conditions (Kandpal et al., 2024).

3 Discussion

Despite decades of research investment, the number of drugs available for managing AD remains limited, with most providing only symptomatic relief and benefiting a restricted subset of patients (Oxford et al., 2020). The recent approval of amyloid-targeting antibodies marks an important step toward disease-modifying therapies. However, these treatments are indicated primarily for individuals with early-stage AD or mild cognitive impairment, and they are not curative, carrying their own risks and limitations5.

New hypotheses have emerged to explain the complex etiopathology of AD (Zhang et al., 2024), which should be taken into account when designing novel therapeutic and preventive strategies. This is particularly relevant given that nearly half of all dementia cases could be prevented by addressing modifiable risk factors (Livingston et al., 2024).

The high historical failure rate in AD drug development (Cummings et al., 2014) may have stemmed from an overreliance on reductionist disease hypotheses and inadequate preclinical models, including transgenic animals and simplistic in vitro systems. Emerging human-centered models now offer powerful tools to elucidate the role of risk factors in triggering and exacerbating neurodegeneration and AD (Sreenivasamurthy et al., 2023; Lopes and Guil-Guerrero, 2025; Dolciotti et al., 2025). Particularly in the field of AD research, where animal experimentation continues to feature prominently, CIVMs have been at the forefront of a recent paradigm shift towards the broader adoption of human-centered and non-animal methodologies (Taylor et al., 2024; Vashishat et al., 2024) to drive progress and increase the translatability of preclinical research findings (Mehta et al., 2025).

The enhanced applicability of CIVMs for modeling human biology at both cellular and molecular levels has progressively enabled comprehensive investigations into novel hypotheses underlying AD etiology. These include neuroinflammatory responses to pathogens (Seaks and Wilcock, 2020; Catumbela et al., 2023), the effects of environmental toxicants (Dhapola et al., 2024), and the involvement of interactions along the GBA (Seo and Holtzman, 2024), which are increasingly recognized as potential drivers of neurodegeneration. As reported in this review, human-centered CIVMs, particularly cerebral organoids and OOC systems, can be applied to explore these new etiological hypotheses.

Each model has its strengths and weaknesses. CIVMs offer the potential advantage of being patient-specific, preserving individual (epi)genetic traits that support personalized and precision medicine approaches (Lopes and Guil-Guerrero, 2025). While they hold promise for overcoming the constraints of animal and simplistic in vitro models, technical optimization remains essential to realize their full potential. For example, brain organoids model early brain development rather than the aging brain, so their relevance to age-related neurodegeneration remains uncertain and needs rigorous validation through complementary approaches (Cerneckis et al., 2023). In addition, lack of vascularization can lead to internal hypoxia and cellular stress, resulting in necrosis and the impaired specification of cellular subtypes (Parthasarathy et al., 2026). CIVMs also face reproducibility issues due to biological variability, limited standardization and scalability, and poor reporting, hindering their validation and adoption by industry (Pamies et al., 2024).

Despite these limitations, legislation in the EU (European Medicines Agency, 2023), the US (Food and Drug Administration, 2024; Food and Drug Administration, 2025) and other regions is increasingly supporting the integration of non-animal approaches in pharmaceutical development, signaling a broader shift toward human-centered research.

Recent evidence suggests that dynamic culture conditions can substantially improve the physiological relevance of in vitro models. For example, perfusion-based systems have been shown to better recapitulate in vivo vascularization by enhancing nutrient delivery, waste removal, and biomechanical cues compared with static culture (Quintard et al., 2024). Similarly, oxygenation has been identified as a critical determinant of organoid viability and maturation, with insufficient oxygen supply markedly impairing cellular health and disrupting normal tissue development in brain organoids (Leung et al., 2022; Mohapatra et al., 2025). Moreover, variations in extrinsic forces and spatio-temporal dynamics can influence cellular composition and metabolic parameters in brain organoids (Aiello et al., 2025), thereby affecting both synaptogenesis and the proportion of specialized neuronal cells and glia (Saglam-Metiner et al., 2023), which represent critical endpoints for faithfully modeling neurodegenerative conditions and AD. Together, this highlights that microenvironmental parameters are central to maintaining homeostatic and pathophysiological processes in complex 3D cultures. Therefore, it is imperative not only to optimise CIVM culture parameters systematically, but also to implement rigorous, longitudinal characterisation of these test systems. Such characterisation should include quantitative assessment of culture conditions, cell viability, and disease-relevant biomarkers to ensure reproducibility and predictive validity.

To enhance reproducibility, fit-for-purpose guidelines have been introduced to promote the consistent performance of CIVMs (Pamies et al., 2024). Furthermore, minimum reporting standards for in vitro models, including organoids and microphysiological systems (Pamies et al., 2018; Mohapatra et al., 2025), have been proposed to enhance study quality for safety and regulatory assessments, with relevance also for basic and translational research and drug efficacy testing.

We acknowledge two main limitations of this study. Firstly, due to word count constraints, only studies employing organoids and OOC models were considered, whereas other CIVMs such as co-culture models could also be relevant. Secondly, for the same reason, we focused on selected hypotheses regarding AD pathogenesis, while recognizing that CIVMs have also been used to investigate additional etiological hypotheses not addressed in this review.

4 Conclusion and future outlook

CIVMs are playing an increasingly pivotal role in AD research. Their capacity to recapitulate key aspects of human brain physiology and pathology offers unprecedented opportunities to deepen our understanding of AD etiopathogenesis, including the contribution of genetic, molecular, and environmental risk factors.

Modern research increasingly combines CIVMs with advanced computational approaches, AI, and digital twin technologies to integrate and interpret the rapidly expanding body of biological and clinical data, thereby accelerating target discovery and drug development (Li et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2025). Such integrative frameworks hold great promise for revealing novel disease mechanisms and optimizing therapeutic interventions in a human-relevant context.

Future research should focus on disentangling correlations from causal relationships among risk factors and comorbidities to more precisely identify pathogens and environmental contributors that directly drive neurodegeneration and AD onset. Elucidating these causal pathways at the molecular and cellular levels will be critical for developing effective preventive and therapeutic strategies. These efforts should be underpinned by the broader adoption of human-centered CIVMs and other new approach methodologies which can improve translatability, reduce reliance on animal models, and enable truly patient-centered approaches to AD research, prevention, and treatment development.

Statements

Author contributions

MP: Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization. FP: Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^ https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

2.^ https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/dementia-statistics/

3.^ https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/medications-for-memory

4.^ https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers/art-20048103

5.^ https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/in-depth/alzheimers/art-20048103

References

1

Abrahamson E. E. Zheng W. Muralidaran V. Ikonomovic M. D. Bloom D. C. Nimgaonkar V. L. et al (2021). Modeling Aβ42 accumulation in response to Herpes simplex virus 1 infection: two dimensional or three dimensional?J. Virol.95. 10.1128/JVI.02219-20

2

Abreu C. M. Gama L. Krasemann S. Chesnut M. Odwin-Dacosta S. Hogberg H. T. et al (2018). Microglia increase inflammatory responses in iPSC-Derived human BrainSpheres. Front. Microbiol.9, 2766. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02766

3

Aiello G. Nemir M. Vidimova B. Ramel C. Viguie J. Ravera A. et al (2025). Increased reproducibility of brain organoids through controlled fluid dynamics. EMBO Rep.26, 6209–6239. 10.1038/s44319-025-00619-x

4

Alam K. Nair L. Mukherjee S. Kaur K. Singh M. Kaity S. et al (2024). Cellular interplay to 3D in vitro microphysiological disease model: cell patterning microbiota–gut–brain axis. Bio-Des. Manuf.7, 320–357. 10.1007/s42242-024-00282-6

5

Andrews M. G. Mukhtar T. Eze U. C. Simoneau C. R. Ross J. Parikshak N. et al (2022). Tropism of SARS-CoV-2 for human cortical astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.119, e2122236119. 10.1073/pnas.2122236119

6

Ashique S. Mohanto S. Ahmed M. G. Mishra N. Garg A. Chellappan D. K. et al (2024). Gut-brain axis: a cutting-edge approach to target neurological disorders and potential synbiotic application. Heliyon10, e34092. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34092

7

Boghdeh N. A. Risner K. H. Barrera M. D. Britt C. M. Schaffer D. K. Alem F. et al (2022). Application of a human blood brain barrier Organ-on-a-Chip model to evaluate small molecule effectiveness against Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. Viruses14, 2799. 10.3390/v14122799

8

Boreland A. J. Stillitano A. C. Lin H.-C. Abbo Y. Hart R. P. Jiang P. et al (2024). Sustained type I interferon signaling after human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of human iPSC derived microglia and cerebral organoids. iScience27, 109628. 10.1016/j.isci.2024.109628

9

Brown G. C. Heneka M. T. (2024). The endotoxin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener.19, 30. 10.1186/s13024-024-00722-y

10

Brown J. A. Codreanu S. G. Shi M. Sherrod S. D. Markov D. A. Neely M. D. et al (2016). Metabolic consequences of inflammatory disruption of the blood-brain barrier in an organ-on-chip model of the human neurovascular unit. J. Neuroinflammation13, 306. 10.1186/s12974-016-0760-y

11

Bruno F. Abondio P. Bruno R. Ceraudo L. Paparazzo E. Citrigno L. et al (2023). Alzheimer’s disease as a viral disease: revisiting the infectious hypothesis. Ageing Res. Rev.91, 102068. 10.1016/j.arr.2023.102068

12

Buck R. C. Franklin J. Berger U. Conder J. M. Cousins I. T. De Voogt P. et al (2011). Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag.7, 513–541. 10.1002/ieam.258

13

Buzhdygan T. P. DeOre B. J. Baldwin-Leclair A. Bullock T. A. McGary H. M. Khan J. A. et al (2020). The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alters barrier function in 2D static and 3D microfluidic in-vitro models of the human blood–brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis.146, 105131. 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105131

14

Cairns D. M. Rouleau N. Parker R. N. Walsh K. G. Gehrke L. Kaplan D. L. (2020). A 3D human brain–like tissue model of herpes-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Adv.6, eaay8828. 10.1126/sciadv.aay8828

15

Cairns D. M. Smiley B. M. Smiley J. A. Khorsandian Y. Kelly M. Itzhaki R. F. et al (2025). Repetitive injury induces phenotypes associated with Alzheimer’s disease by reactivating HSV-1 in a human brain tissue model. Sci. Signal.18, eado6430. 10.1126/scisignal.ado6430

16

Catumbela C. S. G. Giridharan V. V. Barichello T. Morales R. (2023). Clinical evidence of human pathogens implicated in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and the therapeutic efficacy of antimicrobials: an overview. Transl. Neurodegener.12, 37. 10.1186/s40035-023-00369-7

17

Cerneckis J. Bu G. Shi Y. (2023). Pushing the boundaries of brain organoids to study Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol. Med.29, 659–672. 10.1016/j.molmed.2023.05.007

18

Cheng F. Sha Z. Zhou Y. Hou Y. Zhang P. Pieper A. A. et al (2025). The role for artificial intelligence in identifying combination therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis.12, 100366. 10.1016/j.tjpad.2025.100366

19

Colinet M. Chiver I. Bonafina A. Masset G. Almansa D. Di Valentin E. et al (2025). SARS-CoV2 infection triggers inflammatory conditions and astrogliosis-related gene expression in long-term human cortical organoids. Stem Cells43, sxaf010. 10.1093/stmcls/sxaf010

20

Cryan J. F. O’Riordan K. J. Cowan C. S. M. Sandhu K. V. Bastiaanssen T. F. S. Boehme M. et al (2019). The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev.99, 1877–2013. 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

21

Cummings J. L. Morstorf T. Zhong K. (2014). Alzheimer’s disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res. Ther.6, 37. 10.1186/alzrt269

22

DeOre B. J. Tran K. A. Andrews A. M. Ramirez S. H. Galie P. A. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 spike protein disrupts blood–brain barrier integrity via RhoA activation. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol.16, 722–728. 10.1007/s11481-021-10029-0

23

Dhanawat M. Malik G. Wilson K. Gupta S. Gupta N. Sardana S. (2025). The gut microbiota-brain axis: a new frontier in alzheimer’s disease pathology. CNS Neurol. Disord. - Drug Targets24, 7–20. 10.2174/0118715273302508240613114103

24

Dhapola R. Sharma P. Kumari S. Bhatti J. S. HariKrishnaReddy D. (2024). Environmental toxins and alzheimer’s disease: a comprehensive analysis of pathogenic mechanisms and therapeutic modulation. Mol. Neurobiol.61, 3657–3677. 10.1007/s12035-023-03805-x

25

Dolciotti C. Righi M. Grecu E. Trucas M. Maxia C. Murtas D. et al (2025). The translational power of Alzheimer’s-based organoid models in personalized medicine: an integrated biological and digital approach embodying patient clinical history. Front. Cell. Neurosci.19, 1553642. 10.3389/fncel.2025.1553642

26

Dos Reis R. S. Sant S. Keeney H. Wagner M. C. E. Ayyavoo V. (2020). Modeling HIV-1 neuropathogenesis using three-dimensional human brain organoids (hBORGs) with HIV-1 infected microglia. Sci. Rep.10, 15209. 10.1038/s41598-020-72214-0

27

Drinkall N. J. Siersma V. Lathe R. Waldemar G. Janbek J. (2025). Herpesviruses, antiviral treatment, and the risk of dementia – systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Res. Ther.17, 201. 10.1186/s13195-025-01838-z

28

Duara R. Barker W. (2022). Heterogeneity in alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and progression rates: implications for therapeutic trials. Neurotherapeutics19, 8–25. 10.1007/s13311-022-01185-z

29

Duffield G. Bunn S. (2023). “Indoor air quality”. Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. London, United Kingdom: Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. 10.58248/PB54

30

Eimer W. A. Vijaya Kumar D. K. Navalpur Shanmugam N. K. Rodriguez A. S. Mitchell T. Washicosky K. J. et al (2018). Alzheimer’s disease-associated β-Amyloid is rapidly seeded by herpesviridae to protect against brain infection. Neuron99, 56–63.e3. 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.06.030

31

Erny D. Hrabě De Angelis A. L. Jaitin D. Wieghofer P. Staszewski O. David E. et al (2015). Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci.18, 965–977. 10.1038/nn.4030

32

European Medicines Agency (2023). Concept paper on the revision of the guideline on the principles of regulatroy acceptance of 3Rs replacement, reduction, refinement testing approaches EMA/CHMP/CVMP/JEG-3Rs/450091/2021. Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/concept-paper-revision-guideline-principles-regulatory-acceptance-3rs-replacement-reduction-refinement-testing-approaches_en.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

33

Food and Drug Administration (2024). H.R.7248 - 118Th congress (2023-2024): FDA modernization act 3.0. Available online at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/7248/text (Accessed November 11, 2025).

34

Food and Drug Administration (2025). Roadmap to reducing animal testing in preclinical safety studies. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/files/newsroom/published/roadmap_to_reducing_animal_testing_in_preclinical_safety_studies.pdf (Accessed November 11, 2025).

35

Gosztyla M. L. Brothers H. M. Robinson S. R. (2018). Alzheimer’s Amyloid-β is an antimicrobial peptide: a review of the evidence. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.62, 1495–1506. 10.3233/JAD-171133

36

Griep L. M. Wolbers F. De Wagenaar B. Ter Braak P. M. Weksler B. B. Romero I. A. et al (2013). BBB ON CHIP: microfluidic platform to mechanically and biochemically modulate blood-brain barrier function. Biomed. Microdevices15, 145–150. 10.1007/s10544-012-9699-7

37

Huang Y. Dai Y. Li M. Guo L. Cao C. Huang Y. et al (2021). Exposure to cadmium induces neuroinflammation and impairs ciliogenesis in hESC-derived 3D cerebral organoids. Sci. Total Environ.797, 149043. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149043

38

Ijezie E. C. Miller M. J. Hardy C. Jarvis A. R. Czajka T. F. D’Brant L. et al (2024). HSV-1 infection alters MAPT splicing and promotes tau pathology in neural models of alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv., 2024.10.16.618683. 10.1101/2024.10.16.618683

39

Iqbal U. H. Zeng E. Pasinetti G. M. (2020). The use of antimicrobial and antiviral drugs in alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.21, 4920. 10.3390/ijms21144920

40

Iqubal A. Ahmed M. Ahmad S. Sahoo C. R. Iqubal M. K. Haque S. E. (2020). Environmental neurotoxic pollutants: review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.27, 41175–41198. 10.1007/s11356-020-10539-z

41

Isik M. Eylem C. C. Erdogan-Gover K. Aytar-Celik P. Enuh B. M. Emregul E. et al (2025). Pathogenic microbiota disrupts the intact structure of cerebral organoids by altering energy metabolism. Mol. Psychiatry. 10.1038/s41380-025-03152-4

42

Ju J. Su Y. Zhou Y. Wei H. Xu Q. (2022). The SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein disrupts barrier function in an in vitro human blood-brain barrier model. Front. Cell. Neurosci.16, 897564. 10.3389/fncel.2022.897564

43

Kandpal M. Baral B. Varshney N. Jain A. K. Chatterji D. Meena A. K. et al (2024). Gut-brain axis interplay via STAT3 pathway: implications of Helicobacter pylori derived secretome on inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Virulence15, 2303853. 10.1080/21505594.2024.2303853

44

Kang Y. J. Tan H. Lee C. Y. Cho H. (2021). An air particulate pollutant induces neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in human brain models. Adv. Sci.8, 2101251. 10.1002/advs.202101251

45

Kase Y. Sonn I. Goto M. Murakami R. Sato T. Okano H. (2023). The original strain of SARS-CoV-2, the Delta variant, and the omicron variant infect microglia efficiently, in contrast to their inability to infect neurons: analysis using 2D and 3D cultures. Exp. Neurol.363, 114379. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2023.114379

46

Kim M.-H. Kim D. Sung J. H. (2021). A gut-brain Axis-on-a-Chip for studying transport across epithelial and endothelial barriers. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.101, 126–134. 10.1016/j.jiec.2021.06.021

47

Kim N. Y. Lee H. Y. Choi Y. Y. Mo S. J. Jeon S. Ha J. H. et al (2024). Effect of gut microbiota-derived metabolites and extracellular vesicles on neurodegenerative disease in a gut-brain axis chip. Nano Converg.11, 7. 10.1186/s40580-024-00413-w

48

Kong W. Montano M. Corley M. J. Helmy E. Kobayashi H. Kinisu M. et al (2022). Neuropilin-1 mediates SARS-CoV-2 infection of astrocytes in brain organoids, inducing inflammation leading to dysfunction and death of neurons. mBio13, e02308-22. 10.1128/mbio.02308-22

49

Kong D. Park K. H. Kim D.-H. Kim N. G. Lee S.-E. Shin N. et al (2023). Cortical-blood vessel assembloids exhibit Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes by activating glia after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Death Discov.9, 32. 10.1038/s41420-022-01288-8

50

Kong W. Frouard J. Xie G. Corley M. J. Helmy E. Zhang G. et al (2024). Neuroinflammation generated by HIV-Infected microglia promotes dysfunction and death of neurons in human brain organoids. PNAS Nexus3, pgae179. 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae179

51

Kumar D. K. V. Choi S. H. Washicosky K. J. Eimer W. A. Tucker S. Ghofrani J. et al (2016). Amyloid-β peptide protects against microbial infection in mouse and worm models of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med.8, 340ra72. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf1059

52

Lee S.-E. Choi H. Shin N. Kong D. Kim N. G. Kim H.-Y. et al (2022). Zika virus infection accelerates Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in brain organoids. Cell Death Discov.8, 153. 10.1038/s41420-022-00958-x

53

Leung C. M. De Haan P. Ronaldson-Bouchard K. Kim G.-A. Ko J. Rho H. S. et al (2022). A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer2, 33. 10.1038/s43586-022-00118-6

54

Li H. Wang X. Yu H. Zhu J. Jin H. Wang A. et al (2018). Combining in vitro and in silico approaches to find new candidate drugs targeting the pathological proteins related to the alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Neuropharmacol.16, 758–768. 10.2174/1570159X15666171030142108

55

Li Y. Hu C. Wang P. Liu Y. Wang L. Pi Q. et al (2019). Indoor nanoscale particulate matter-induced coagulation abnormality based on a human 3D microvascular model on a microfluidic chip. J. Nanobiotechnology17, 20. 10.1186/s12951-019-0458-2

56

Livingston G. Huntley J. Liu K. Y. Costafreda S. G. Selbæk G. Alladi S. et al (2024). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the lancet standing commission. Lancet404, 572–628. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01296-0

57

Logan K. Ng T. K. S. Wee H. N. Ching J. (2023). Gut-brain axis through the lens of gut microbiota and their relationships with Alzheimer’s disease pathology: review and recommendations. Mech. Ageing Dev.211, 111787. 10.1016/j.mad.2023.111787

58

Lopes P. A. Guil-Guerrero J. L. (2025). Beyond transgenic mice: emerging models and translational strategies in alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.26, 5541. 10.3390/ijms26125541

59

Lu S. Zhu X. Zeng P. Hu L. Huang Y. Guo X. et al (2024). Exposure to PFOA, PFOS, and PFHxS induces Alzheimer’s disease-like neuropathology in cerebral organoids. Environ. Pollut.363, 125098. 10.1016/j.envpol.2024.125098

60

Marshall L. J. Bailey J. Cassotta M. Herrmann K. Pistollato F. (2023). Poor translatability of biomedical research using animals — a narrative review. Altern. Lab. Anim.51, 102–135. 10.1177/02611929231157756

61

Martinez-Meza S. Premeaux T. A. Cirigliano S. M. Friday C. M. Michael S. Mediouni S. et al (2025). Antiretroviral drug therapy does not reduce neuroinflammation in an HIV-1 infection brain organoid model. J. Neuroinflammation22, 66. 10.1186/s12974-025-03375-w

62

McMahon C. L. Staples H. Gazi M. Carrion R. Hsieh J. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 targets glial cells in human cortical organoids. Stem Cell Rep.16, 1156–1164. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.01.016

63

Meftah S. Gan J. (2023). Alzheimer’s disease as a synaptopathy: evidence for dysfunction of synapses during disease progression. Front. Synaptic Neurosci.15, 1129036. 10.3389/fnsyn.2023.1129036

64

Mehta K. Maass C. Cucurull-Sanchez L. Pichardo-Almarza C. Subramanian K. Androulakis I. P. et al (2025). Modernizing preclinical drug development: the role of new approach methodologies. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci.8, 1513–1525. 10.1021/acsptsci.5c00162

65

Mohapatra R. Leist M. Aulock S. von Hartung T. (2025). Guidance for good in vitro reporting standards (GIVReSt) – a draft for stakeholder discussion and background documentation. ALTEX42, 376–396. 10.14573/altex.2507041

66

Nabi M. Tabassum N. (2022). Role of environmental toxicants on neurodegenerative disorders. Front. Toxicol.4, 837579. 10.3389/ftox.2022.837579

67

Narasipura S. D. Zayas J. P. Ash M. K. Reyes A. F. Shull T. Gambut S. et al (2025). Inflammatory responses revealed through HIV infection of microglia-containing cerebral organoids. J. Neuroinflammation22, 36. 10.1186/s12974-025-03353-2

68

Nordengen K. Kirsebom B.-E. Henjum K. Selnes P. Gísladóttir B. Wettergreen M. et al (2019). Glial activation and inflammation along the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. J. Neuroinflammation16, 46. 10.1186/s12974-019-1399-2

69

Nortley R. Korte N. Izquierdo P. Hirunpattarasilp C. Mishra A. Jaunmuktane Z. et al (2019). Amyloid β oligomers constrict human capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease via signaling to pericytes. Science365, eaav9518. 10.1126/science.aav9518

70

Oh S.-J. Kim Y. Y. Ma R. Choi S. T. Choi S. M. Cho J. H. et al (2025). Pharmacological targeting of mitophagy via ALT001 improves Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1)-Mediated microglial inflammation and promotes amyloid β phagocytosis by restricting HSV1 infection. Theranostics15, 4890–4908. 10.7150/thno.105953

71

Oxford A. E. Stewart E. S. Rohn T. T. (2020). Clinical trials in alzheimer’s disease: a hurdle in the path of remedy. Int. J. Alzheimers Dis.2020, 1–13. 10.1155/2020/5380346

72

Pamies D. Bal-Price A. Chesné C. Coecke S. Dinnyes A. Eskes C. et al (2018). Advanced good cell culture practice for human primary, stem cell-derived and organoid models as well as microphysiological systems. ALTEX35, 353–378. 10.14573/altex.1710081

73

Pamies D. Ekert J. Zurich M.-G. Frey O. Werner S. Piergiovanni M. et al (2024). Recommendations on fit-for-purpose criteria to establish quality management for microphysiological systems and for monitoring their reproducibility. Stem Cell Rep.19, 604–617. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2024.03.009

74

Park S. Choi J.-W. (2023). Nanoscale diesel-exhaust particulate matter (DPM) impairs synaptic plasticity of human iPSCs-Derived cerebral organoids. BioChip J.17, 349–356. 10.1007/s13206-023-00107-1

75

Park S. B. Jo J. H. Kim S. S. Jung W. H. Bae M. A. Koh B. et al (2025). Microplastics accumulation induces kynurenine-derived neurotoxicity in cerebral organoids and mouse brain. Biomol. Ther.33, 447–457. 10.4062/biomolther.2024.185

76

Parthasarathy S. Giridharan B. Konyak L. (2026). “Brain organoids – challenges while constructing organoids,” in Fundamentals of brain organoids for neurological diseases (Elsevier), 265–278. 10.1016/B978-0-443-29898-1.00006-X

77

Pediaditakis I. Kodella K. R. Manatakis D. V. Le C. Y. Barthakur S. Sorets A. et al (2022). A microengineered brain-chip to model neuroinflammation in humans. iScience25, 104813. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104813

78

Pound P. Ritskes-Hoitinga M. (2018). Is it possible to overcome issues of external validity in preclinical animal research? Why Most animal models are bound to fail. J. Transl. Med.16, 304. 10.1186/s12967-018-1678-1

79

Prosswimmer T. Heng A. Daggett V. (2024). Mechanistic insights into the role of amyloid-β in innate immunity. Sci. Rep.14, 5376. 10.1038/s41598-024-55423-9

80

Qiao H. Guo M. Shang J. Zhao W. Wang Z. Liu N. et al (2020). Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection leads to neurodevelopmental disorder-associated neuropathological changes. PLOS Pathog.16, e1008899. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008899

81

Qiao H. Zhao W. Guo M. Zhu L. Chen T. Wang J. et al (2022). Cerebral organoids for modeling of HSV-1-Induced-Amyloid β associated neuropathology and phenotypic rescue. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 5981. 10.3390/ijms23115981

82

Quintard C. Tubbs E. Jonsson G. Jiao J. Wang J. Werschler N. et al (2024). A microfluidic platform integrating functional vascularized organoids-on-chip. Nat. Commun.15, 1452. 10.1038/s41467-024-45710-4

83

Raimondi M. T. Albani D. Giordano C. (2019). An Organ-On-A-Chip engineered platform to study the microbiota–gut–brain axis in neurodegeneration. Trends Mol. Med.25, 737–740. 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.07.006

84

Ramani A. Müller L. Ostermann P. N. Gabriel E. Abida‐Islam P. Müller‐Schiffmann A. et al (2020). SARS ‐CoV‐2 targets neurons of 3D human brain organoids. EMBO J.39, e106230. 10.15252/embj.2020106230

85

Saglam-Metiner P. Devamoglu U. Filiz Y. Akbari S. Beceren G. Goker B. et al (2023). Spatio-temporal dynamics enhance cellular diversity, neuronal function and further maturation of human cerebral organoids. Commun. Biol.6, 173. 10.1038/s42003-023-04547-1

86

Samudyata S. Oliveira A. O. Malwade S. Rufino De Sousa N. Goparaju S. K. Gracias J. et al (2022). SARS-CoV-2 promotes microglial synapse elimination in human brain organoids. Mol. Psychiatry27, 3939–3950. 10.1038/s41380-022-01786-2

87

Sanchez-Varo R. Mejias-Ortega M. Fernandez-Valenzuela J. J. Nuñez-Diaz C. Caceres-Palomo L. Vegas-Gomez L. et al (2022). Transgenic mouse models of alzheimer’s disease: an integrative analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.23, 5404. 10.3390/ijms23105404

88

Seaks C. E. Wilcock D. M. (2020). Infectious hypothesis of alzheimer disease. PLOS Pathog.16, e1008596. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008596

89

Seo D. Holtzman D. M. (2024). Current understanding of the Alzheimer’s disease-associated microbiome and therapeutic strategies. Exp. Mol. Med.56, 86–94. 10.1038/s12276-023-01146-2

90

Seo S. Jang M. Kim H. Sung J. H. Choi N. Lee K. et al (2023). Neuro‐Glia‐Vascular‐on‐a‐Chip System to assess aggravated neurodegeneration via brain endothelial cells upon exposure to diesel exhaust particles. Adv. Funct. Mater.33, 2210123. 10.1002/adfm.202210123

91

Seo G. M. Lee H. Kang Y. J. Kim D. Sung J. H. (2024). Development of in vitro model of exosome transport in microfluidic gut-brain axis-on-a-chip. Lab. Chip24, 4581–4593. 10.1039/D4LC00490F

92

Shin Y. Choi S. H. Kim E. Bylykbashi E. Kim J. A. Chung S. et al (2019). Blood–brain barrier dysfunction in a 3D in vitro model of alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Sci.6, 1900962. 10.1002/advs.201900962

93

Sousa J. A. Bernardes C. Bernardo-Castro S. Lino M. Albino I. Ferreira L. et al (2023). Reconsidering the role of blood-brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease: from delivery to target. Front. Aging Neurosci.15, 1102809. 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1102809

94

Sreenivasamurthy S. Laul M. Zhao N. Kim T. Zhu D. (2023). Current progress of cerebral organoids for modeling Alzheimer’s disease origins and mechanisms. Bioeng. Transl. Med.8, e10378. 10.1002/btm2.10378

95

Sundstrom J. Vanderleeden E. Barton N. J. Redick S. D. Dawes P. Murray L. F. et al (2024). Herpes simplex virus 1 infection of human brain organoids and pancreatic stem cell-islets drives organoid-specific transcripts associated with alzheimer’s disease and autoimmune diseases. Cells13, 1978. 10.3390/cells13231978

96

Taylor K. Modi S. Bailey J. (2024). An analysis of trends in the use of animal and non-animal methods in biomedical research and toxicology publications. Front. Lab. Chip Technol.3, 1426895. 10.3389/frlct.2024.1426895

97

Vashishat A. Patel P. Das Gupta G. Das Kurmi B. (2024). Alternatives of animal models for biomedical research: a comprehensive review of modern approaches. Stem Cell Rev. Rep.20, 881–899. 10.1007/s12015-024-10701-x

98

Vatine G. D. Barrile R. Workman M. J. Sances S. Barriga B. K. Rahnama M. et al (2019). Human iPSC-Derived blood-brain barrier chips enable disease modeling and personalized medicine applications. Cell Stem Cell24, 995–1005.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.05.011

99

Veening-Griffioen D. H. Ferreira G. S. Van Meer P. J. K. Boon W. P. C. Gispen-de Wied C. C. Moors E. H. M. et al (2019). Are some animal models more equal than others? A case study on the translational value of animal models of efficacy for Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol.859, 172524. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.172524

100

Wang X.-L. Zeng J. Feng J. Tian Y.-T. Liu Y.-J. Qiu M. et al (2014). Helicobacter pylori filtrate impairs spatial learning and memory in rats and increases Î2-amyloid by enhancing expression of presenilin-2. Front. Aging Neurosci.6, 66. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00066

101

Xu R. Boreland A. J. Li X. Erickson C. Jin M. Atkins C. et al (2021). Developing human pluripotent stem cell-based cerebral organoids with a controllable microglia ratio for modeling brain development and pathology. Stem Cell Rep.16, 1923–1937. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.06.011

102

Young C. B. Mormino E. C. (2022). Prevalence rates of amyloid positivity—updates and relevance. JAMA Neurol.79, 225–227. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.5225

103

Zhang J. Zhang Y. Wang J. Xia Y. Zhang J. Chen L. (2024). Recent advances in Alzheimer’s disease: mechanisms, clinical trials and new drug development strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.9, 211. 10.1038/s41392-024-01911-3

104

Zhang M. Wang P. Wu Y. Jin L. Liu J. Deng P. et al (2025). A microengineered 3D human neurovascular unit model to probe the neuropathogenesis of Herpes simplex encephalitis. Nat. Commun.16, 3701. 10.1038/s41467-025-59042-4

105

Zhong M. Z. Peng T. Duarte M. L. Wang M. Cai D. (2024). Updates on mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener.19, 23. 10.1186/s13024-024-00712-0

Summary

Keywords

Alzheimer’s disease, complex in vitro models, environmental toxicants, gut-brain axis, infectious hypothesis, neuroinflammation, organoids, organ-on-a-chip

Citation

Price M and Pistollato F (2026) Beyond the amyloid hypothesis: leveraging human-centered complex in vitro models to decode Alzheimer’s disease etiology. Front. Toxicol. 7:1753572. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2025.1753572

Received

25 November 2025

Revised

14 December 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

09 January 2026

Volume

7 - 2025

Edited by

Sara Bridio, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Italy

Reviewed by

Giustina Casagrande, Polytechnic University of Milan, Italy

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Price and Pistollato.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew Price, m.price@soton.ac.uk

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.