Abstract

Background:

Microplastic pollution has emerged as a global environmental crisis with potential adverse consequences on human health. Mixtures of microplastics with fungal particles including mycelial fragments or spores are highly probable exposure scenarios occurring in various occupational settings or in moldy built indoor environments. However, immunotoxic outcomes associated with such exposure remain poorly characterized. Most studies have focused on single‐exposure components. Here, we investigated, for the first time, the immunotoxic effects of microplastics mixed with spores or mycelial fragments from Aspergillus fumigatus on human neutrophil-like cells.

Materials and methods:

Differentiated HL60 neutrophil-like cells were exposed to 0–100 μg/mL HDPE microplastics mixed with 106 heat-inactivated mycelial fragments or spores for 24 h.

Results and discussion:

HDPE combined with fungal fragments induced significant release of IL‐6 and IL‐8 while the mixtures with fungal spores induced only IL‐6 release from the neutrophil-like cells. Most importantly, we observed a trend of decreasing IL‐6 levels with increasing doses of HDPE microplastics in mixture with fungal particles, indicating possible dysregulation of the pro-inflammatory response. The tested doses of HDPE microplastics in mixture with fungal particles showed no significant acute effects on the cell viability. Using HEK293‐TLR reporter cells, we found no significant activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by HDPE microplastics, fungal particles, or their combination, suggesting that the release of IL‐6 and IL‐8 is induced through other innate immune-signaling pathways. Taken together, fungal particles as microbial contaminants, seem to be the main drivers of the immune responses triggered by exposure to mixed HDPE microplastics and fungal particles. Among these, fungal mycelial fragments appear to be the most potent compared to fungal spores that are typically monitored for risk assessments.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

Mixtures of microplastics with fungal fragments induced stronger and more complex pro-inflammatory responses than mixtures with fungal spores.

Increasing doses of microplastics seem to reduce the levels of released IL-6.

The tested doses had no acute effect on cell viability.

The tested doses induced no TLR2 and TLR4 activation through the NF-κB pathway, indicating the involvement of other pathways leading to IL-6 or IL-8 release

1 Introduction

Plastic production, use, and improper plastic waste management constitute major drivers of the emerging planetary pollution crisis. Plastic degradation releases micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) that infiltrate and bioaccumulate across diverse biomes, including human tissues. Although health impact assessments remain in preliminary stages, human biomonitoring studies revealed the presence of MNPs in feces (Yan et al., 2022), placenta (Ragusa et al., 2022), blood (Leslie et al., 2022), lung tissues (Jenner et al., 2022), testes (Hu et al., 2024), and brain tissues (Amato-Lourenço et al., 2024; Nihart et al., 2025). Epidemiological evidence links MNP exposure to a 4.5-fold increased risk of myocardial and cerebral infarcts and mortality (Marfella et al., 2024). Studies have been shown that microorganisms and other contaminants can effectively adsorb onto MNPs (Joo et al., 2021; McCormick et al., 2014) that function as vectors, contributing to the spread of pathogenic, allergenic, and antigenic microbial components. In this regard, available data are limited to bacterial biofilm formation, while less attention has been devoted to such interaction with fungal particles (Gkoutselis et al., 2021).

High-density polyethylene (HDPE) represents a significant source of microplastics due to its widespread application in packaging, construction, and household products, with degradation and fragmentation occurring through mechanical use and environmental weathering (Chinglenthoiba et al., 2025). The persistent environmental presence of HDPE microplastics and their cross-species health implications have emerged as a critical research domain (Naz et al., 2024; Polenogova et al., 2025). The primary concerns are the immunotoxicity and immunomodulatory effects caused by HDPE microplastics (MPs), which have been identified as one of the predominant polymer types contributing to environmental contamination (Beijer et al., 2022; Polenogova et al., 2025). Despite documented immune alterations across fish, invertebrate, and mammalian models, mechanistic understanding at molecular and cellular levels remains limited (Huang et al., 2023; Islam et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024). Moreover, conflicting findings exist on whether HDPE MPs suppress or activate immune responses, with some studies reporting immune suppression and others indicating pro-inflammatory activation (Park et al., 2024; Polenogova et al., 2025; Wolff et al., 2023). Additional uncertainty surrounds the modulatory role of particle size, weathering-induced surface modifications, and co-transported contaminants. This knowledge gap limits both exposure risk assessment and intervention development as immune dysfunction can lead to increased susceptibility to pathogens and chronic inflammation (Xu et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2023).

Both MPs and fungal components independently induce adverse cellular and systemic responses, including oxidative stress, inflammation, genotoxicity, and immune dysregulation. Co-exposure amplifies these concerns as microplastics act as vectors that enhance fungal pathogen and mycotoxin transport, cellular uptake, and bioavailability, potentially altering their pathogenic mechanisms (Gkoutselis et al., 2024; Gkoutselis et al., 2021; Klauer et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024). Since available data are limited to pristine polystyrene test materials, the specific molecular mechanisms induced by environmentally relevant microplastics and the health-associated hazards remain unknown (Jiang et al., 2020; Mitrano and Wohlleben, 2020; Prata et al., 2020). In contrast, the molecular key events induced by fungal exposure and related disease outcomes are well characterized. For example, tissue damage through oxidative stress and inflammatory responses upon exposure to fungal spores, mycotoxins, and volatile organic compounds has been reported (Holme et al., 2020). Aspergillus spp. with Aspergillus fumigatus, in particular, are among the most frequently studied fungal species as their spores and fragments are highly prevalent in various indoor and occupational settings (Li et al., 2022; Mousavi et al., 2016). A. fumigatus is also a well-studied pathogenic fungus, often associated with fungal infection and negative health outcomes in subjects with altered immune systems (Latgé, 2001; Latgé and Chamilos, 2019). Spores from A. fumigatus have been measured in working environments, such as industrial composting and waste treatment facilities (Kontro et al., 2022; Schlosser et al., 2016). Inhaled fungal particles can easily reach the alveoli where they interact with alveolar epithelial cells and macrophages through pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs), initiating inflammatory cascade reactions with the subsequent release of chemokines and cytokines (Adler et al., 1994; Allermann and Poulsen, 2000; Devalia, 1993). The chemokine IL-8 is known as a neutrophilic chemotactic factor as it induces the recruitment of neutrophils and other granulocytes to the particle deposition site (Kolaczkowska and Kubes, 2013). Sustained neutrophilic/granulocyte accumulation in the lungs is associated with an oxidative burst that, during chronic exposure, leads to progressive tissue damage (Johansson and Kirsebom, 2021; McGovern et al., 2016).

Given neutrophils’ central role in innate immunity and their numerical predominance (55%–60%) among circulating leucocytes, characterizing the effects of particulate matter on these cells represents a critical research priority (Johansson and Kirsebom, 2021). Their infiltration into the lungs, as hallmark of inflammatory responses, following airway exposure to polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) microplastics has been documented in rodents (Jung et al., 2025; Tomonaga et al., 2024). Similarly, A. fumigatus spore exposure induces neutrophil migration in Transwell-based in vitro lung models (Feldman et al., 2020). However, neutrophil responses to co-exposure scenarios involving microplastics and fungal particles remain unexplored. Many in vitro studies have used granulocyte-like differentiated human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells as a surrogate for human granulocytes (Blanter et al., 2021; Timm et al., 2009). These cells possess key neutrophil functions, including pathogen and exogenous particle detection via PRRs, particularly Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that recognize fungal cell wall components (Hayashi et al., 2003; Sato et al., 2003; Shuto et al., 2007).

The complex physicochemical properties of microplastics, particularly their ability to simultaneously bind organic compounds and contaminants, demand a holistic assessment approach for potential human health risk evaluation (Galloway et al., 2017; Ramsperger et al., 2020). Current toxicological research has predominantly focused on the isolated effects of individual polymers or single contaminants, often overlooking the prevailing real-world scenarios involving complex environmental mixtures. This reductionist approach likely underestimates health risks as interactions between different pollutants can lead to synergistic or antagonistic effects not predictable from single-exposure studies. There is paucity of immunotoxicity data on MPs in combination with microbial contaminants, particularly from fungi (Hirt and Body-Malapel, 2020; Prata et al., 2020). This knowledge gap is critical given that airborne particulate matter in both indoor and outdoor environments consistently contains microplastics alongside fungal particles (Dris et al., 2017; Zhai et al., 2018), representing the actual human exposure profile.

To explore the neutrophilic immunotoxic effects associated with the complex mixture of microplastic and fungal particles, we exposed neutrophil cells differentiated from HL-60 cells to HDPE particles mixed with spores or mycelial fragments from A. fumigatus. We evaluated the toxic effects on cell viability and the cellular pro-inflammatory responses at protein levels. Moreover, we assessed the NF-κB-induced response through the activation of TLR2 and TLR4 in reporter cells.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Test particles

High-density polyethylene (HDPE) particles (with size characteristics using DLS: number-based median hydrodynamic size, Dn50 = 2.7 µm; 10th percentile hydrodynamic size, Dn10 = 1.3 µm; 90th percentile hydrodynamic size, Dn90 = 5.8 µm) were provided by the University of Torino (UNITO), under the PlasticsFatE consortium, as HDPE particles suspended in sterile endotoxin-free water (Alfa Aesar #J-65589-K2) containing 0.025% BSA. For the fungal particle, A. fumigatus 1863 (strain A1258 FGSC) from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (University of Missouri, Kansas City, United States) was used. Fungal spores (AFS) and mycelial fragments (AFM) were prepared as previously described by Afanou et al. (2014). The fungal spores and fragments were heat-inactivated at 90 °C for 40 min following the protocol from Beisswenger et al. (2012).

The concentrations of the test particles (HDPE, AFM, and AFS) were measured using gravimetry and microscopy. For the gravimetric analysis, 100 µL of the diluted stock suspensions of HDPE, AFM, and AFS was transferred dropwise onto conditioned and pre-weighted polycarbonate membrane filters (0.4-µm pores, Millipore #HTTP02500 Merck Darmstadt, Germany) and were then dried for 4 h under sterile conditions. The filters were then conditioned for 24 h, before being weighed using a high-precision scale (Sartorius AG, MC210, Göttingen, Germany). The dry weight of the particles was determined as the average of three replicates, adjusted using control measurements of environmental changes.

A preliminary light microscopy analysis of the fungal particles was performed prior to field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) analysis. In brief, 10 µL of the diluted stock suspensions of AFM and AFS was applied to a hemocytometer, and the spores and fragments were counted using a light microscope (Discover Echo, Revolve, San Diego, United States). The mean concentrations were estimated from particles counted in 10 fields of the hematocytometer.

To prepare the fungal and HDPE particle mixture, 10 µL of AFM or AFS stock suspensions (1010 particles/mL) was added to 10 mL of HDPE at 10, 100, and 1,000 μg/mL in endotoxin-free water (Sigma-Aldrich #A8806 Merck Darmstadt, Germany) containing 0.025% BSA. Additionally, controls were prepared with an equivalent concentration of AFM or AFS in 0.025% BSA. All suspensions were mixed with 200 rpm orbital shaking for 24 h at room temperature (RT).

2.2 FESEM analysis of the particles

FESEM analysis was performed to assess size characterization and distribution of the test materials. In brief, 100 µL of the HDPE and AFM/AFS suspension mixtures was filtered through 0.4-µm pore polycarbonate filters using a membrane vacuum filtration system (Advantec #311220 Mikrolab Frisenette, Danmark). Each membrane was dried for 2 h under sterile conditions, before being transferred to a two-sided adhesive tab mounted onto an aluminum stub. The samples were then coated with 5 nm platinum in a Cressington super coating machine (Cressington Scientific Instruments Ltd., Watford, United Kingdom). Coated samples were visualized using an FESEM (Hitachi High-Tech, SU6600 Analytical FESEM, Tokyo, Japan). The microscope was operated in the secondary electron imaging mode, with an acceleration voltage of 15 keV, an extraction voltage of 1.8 kV, and a working distance of 10–11 mm. Particle numbers were assessed in randomly selected fields to achieve a total of 200 particles. For the particle size characterization, Esprit feature analysis (Quantax EDS for SEM, Bruker) was performed in back-scattered imaging mode, focusing on particle length, width, average diameter, and equivalent diameters in randomly selected FESEM fields. Assuming a homogenic dispersion of particles over the membrane, the number of particles was determined following the method described by Eduard and Aalen (1988). The number of particles was estimated using the following formula:

where C is the number of particle concentration, N is the number of counted particles, Afilter is the filter area (in mm2), K is the number of SEM areas, and ASEM is the imaging area (in mm2) in SEM.

2.3 HL-60 cell culture and differentiation

The human promyelocytic cell line HL-60 (ATCC #CCL-240 LGC, Lancashire, United Kingdom) was cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 (RPMI; Gibco #61870 Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, United States) medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated endotoxin-free FBS. The cells were sub-cultured every 2–3 days at 37 °C in a 5% saturated CO2 atmosphere with 95% relative humidity. The cells were differentiated to mature granulocytes (dHL-60 cells) using 1.25% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; MP Biosciences #196055 Irvine, CA, United States) over 5 days as previously described in the literature (Manda-Handzlik et al., 2018; Sham et al., 1995). dHL-60 cells were harvested by centrifugation at 200 RCF for 5 min and resuspended in RPMI with 10% FBS. The cell concentration was determined using an automated cell counter (ChemoMetec, NucleoCounter NC-200, Gydevang, Denmark) prior to seeding for various exposure treatments.

2.4 Toll-like receptor activation

To evaluate NF-κB activation via TLR2 and TLR4, we used HEK293 reporter cell lines engineered to express TLR2 or TLR4 and produce secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) upon pathway stimulation. In brief, TLR2 (InvivoGen #hkb-htlr2 Toulouse, France) and TLR4 (InvivoGen #hkb-htlr4) HEK-Blue reporter cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco #31966) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated endotoxin-free fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowest #S1860), 100 U/mL penicillin (Biowest #L0022 Nuaillé, France), 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Biowest #L0022), 100 μg/mL normocin (InvivoGen #ant-zn), and 1xHEK Selection-Blue (InvivoGen #hb-sel).

The exposure to particle suspensions was performed following the method previously described by Brummelman et al. (2015). In brief, 180 µL of HEK-Blue hTLR2 or HEK-Blue hTLR4 cells (2.8 × 104 cells/mL) was seeded in a 96-well plate with each condition tested in technical triplicate. Considering the buoyancy properties of the HDPE particles, additional experiments using inverted 12-well inserts were performed. As such, we believed that there was better interaction between floating HDPE particles and the cells grown on the basolateral side of the insert. A detailed description of the inverted insert system is available in the Supplementary Material. Following 24 h of incubation to allow cell attachment, cultures were treated with 20 µL of 10× concentrated particle suspensions or endotoxin-free water (vehicle control), yielding final 1× particle concentrations in a total volume of 200 µL. As positive controls, lipoteichoic acid (LTA, 100 ng/mL) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 100 ng/mL) were used to stimulate TLR2 and TLR4, respectively. After 24 h of exposure, receptor activation was quantified using the QUANTI-Blue colorimetric assay (InvivoGen #rep-qbs). The supernatant of each treatment (20 µL) was transferred to a new 96-well plate containing 180 µL of QUANTI-Blue reagent. The plates were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and the absorbance was measured at 649 nm using a microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, BioTek Synergy Neo2, Santa Clara, United States). The absorbance readings were blank-adjusted before being normalized to the average of negative controls. Final data from the HEK293-TLR reporter cells were based on two independent experiments with three replicates of each treatment.

2.5 Cell viability by Alamar Blue assay

In brief, 100 µL of dHL-60 cells (5 × 104 cells/mL or 5,000 cells/well) was seeded in phenol-free RPMI medium (Gibco #11835) supplemented with 10% FBS in 96-well plates; 15 μL of 10× concentrated particle suspensions and controls was diluted with 35 µL of culture medium, added to each well in technical triplicates, and incubated for 24 h.

Subsequently, 50 µL of 40% Alamar Blue solution (Invitrogen #DAL1100 Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham MA, United States) in culture medium was added to each well and incubated for 3 h. The plate was then centrifuged at 300 RCF for 5 min, and 100 µL supernatant was transferred to a black-walled 96-well plate (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). The fluorescence of the cell-free solution was measured using a plate reader at 590 nm emission and 560 nm excitation. The sample readings were blank-adjusted before being normalized to the average of the reference control. This assay was repeated in three independent experiments.

2.6 Assessment of pro-inflammatory markers (IL-6 and IL-8) by ELISA

To quantify interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) levels, selected as pro-inflammatory markers, dHL-60 cells were seeded in 6-well plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) at 1.2 × 106 cells/well in 1.8 mL complete culture medium and incubated for 15 min prior to the addition of treatment compounds. Then 200 μL of treatment was added to each well in technical replicates and incubated for 24 h. The supernatant was then collected by centrifugation at 300 RCF for 5 min to remove cells and debris and stored at −80 °C prior to analysis. The exposure and subsequent supernatant were collected from three independent experiments. Analysis of the inflammatory markers was performed using ELISA kits from PeproTech (PeproTech #900-K16 for IL-6 and PeproTech #900-K18 for IL-8, Cranbury, NJ, United States). The ELISA kits were used following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, 96-well plates were coated with 100 µL of the capture biotinylated antibody at 1 μg/mL in PBS and incubated overnight at room temperature (RT). The plates were then washed in a microplate washer four times followed by 5 min of incubation with 300 µL of washing buffer (PeproTech #900-K00). The wells were blocked with 100 µL of blocking buffer for 1 h at RT followed by washing as previously described. A measure of 100 µL of the cell supernatant and standards was transferred to the coated microplates and incubated for 2 h at RT. The samples and standards were discarded, and the wells were washed as described previously. Following this, 100 µL of avidin–HRP-conjugated detection antibody (at 1:2000 dilution) was added to the well and incubated for 2 h at RT. The plates were washed again, and 100 µL of substrates was added to the well followed by 30 min of incubation at RT for color development. The absorbance was monitored every 5 min at 405 nm with wavelength correction at 650 nm in Synergy Neo 2 Microplate reader GEN 5 software (BioTek Instruments, United States). All samples were analyzed in triplicate, and final levels of pro-inflammatory markers were estimated using the four-parameter (4-PL) regression (Dotmatics, GraphPad Prism 9, Boston, United States).

2.7 Data and statistical analysis

Data were organized as metadata with experimental replicates using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was performed in Stata 18.5 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) using the non-parametric Dunn test package for group comparisons followed by false discovery rate (FDR) adjustment (Benjamini–Hochberg method with a significant p-value <0.05). The non-parametric test was used because of the small sample size and the violation of the normality assumption.

3 Results

3.1 Material characteristics

High-resolution micrographs of HDPE microplastics, fungal fragments, and the mixtures are presented in Figure 1. Further characterization of the particle size distribution using FESEM–EDS with Esprit feature analysis of the test materials is summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 1

Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) micrographs of HDPE microplastics (A), along with the mixtures of HDPE MPs and A. fumigatus fragments (B) and spores (C).

TABLE 1

| Test materials | Size characteristic | 10th percentile | 50th percentile | 90th percentile | N particles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFS (0.18 pg/particle)a |

Length (µm) | 1.77 | 2.99 | 6.13 | 346 |

| Width (µm) | 1.22 | 1.96 | 3.71 | ||

| Average diameter (µm) | 1.58 | 2.55 | 5.18 | ||

| Equivalent diameter (µm) | 1.44 | 2.3 | 4.33 | ||

| Aspect ratio | 1.24 | 1.43 | 1.88 | ||

| AFM (1.60 pg/particle)a |

Length (µm) | 4.41 | 6.62 | 11.33 | 643 |

| Width (µm) | 3.06 | 4.29 | 6.52 | ||

| Average diameter (µm) | 3.91 | 5.68 | 9.27 | ||

| Equivalent diameter (µm) | 1.54 | 3.22 | 5.97 | ||

| Aspect ratio | 1.28 | 1.54 | 2.05 | ||

| HDPE (0.05 pg/particle)a |

Length (µm) | 1.97 | 4.13 | 8.36 | 834 |

| Width (µm) | 1.22 | 2.81 | 5.23 | ||

| Average diameter (µm) | 1.71 | 3.6 | 7.05 | ||

| Equivalent diameter (µm) | 1.54 | 3.22 | 5.97 | ||

| Aspect ratio | 1.23 | 1.49 | 2.03 | ||

| AFS–HDPE | Length (µm) | 2.08 | 4.01 | 8.24 | 625 |

| Width (µm) | 1.39 | 2.69 | 5.27 | ||

| Average diameter (µm) | 1.8 | 3.45 | 6.89 | ||

| Equivalent diameter (µm) | 1.6 | 2.99 | 5.84 | ||

| Aspect ratio | 1.25 | 1.49 | 2.00 | ||

| AFM–HDPE | Length (µm) | 2.31 | 5.1 | 10.69 | 458 |

| Width (µm) | 1.65 | 3.43 | 6.55 | ||

| Average diameter (µm) | 2.00 | 4.46 | 8.84 | ||

| Equivalent diameter (µm) | 1.79 | 4.01 | 7.54 | ||

| Aspect ratio | 1.22 | 1.44 | 1.93 |

Average mass per particle by gravimetry and size characteristics and distribution using FESEM.

Average mass of the particles determined using gravimetry.

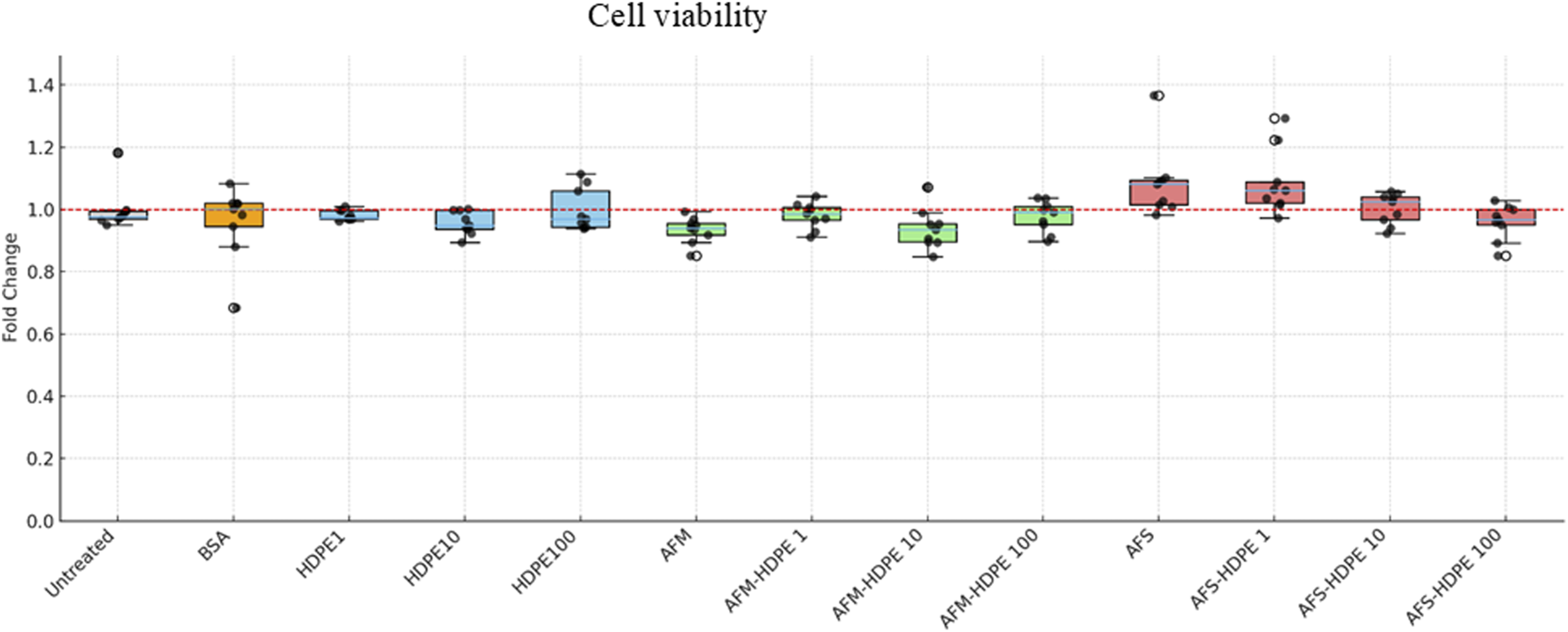

3.2 Cell viability of dHL-60 cells by Alamar Blue assay

The effect of the test materials on cell viability is summarized as box plots in Figure 2. The results reported here are based on changes in the reduction of resazurin following cell exposure to the test materials. All data were adjusted for background signals and normalized to the negative control. Overall, no significant effects on cell viability were detected. However, a slight reduction in cell viability, although not significant, was observed with cells exposed to 106 AFM per mL, mixture of 10 μg/mL HDPE + 106 AFM per mL, and mixture of 100 μg/mL HDPE +106 AFS per mL. Of note, a slight reduction (but not significant) in cell viability was observed in cells exposed to increasing concentrations of HDPE in a mixture with fungal spores.

FIGURE 2

Box plots showing relative changes in reduced resazurin as an indicator of cell viability. Differentiated HL-60 cells were treated with HDPE (1, 10, or –100 μg/mL), or 106 AFM/AFS particles per mL with varying concentrations of HDPE (with HDPE 1 = 1 μg/mL; HDPE 10 = 10 μg/mL; HDPE 100 = 100 μg/mL). Each box represents data from three independent experiments with three technical replicates.

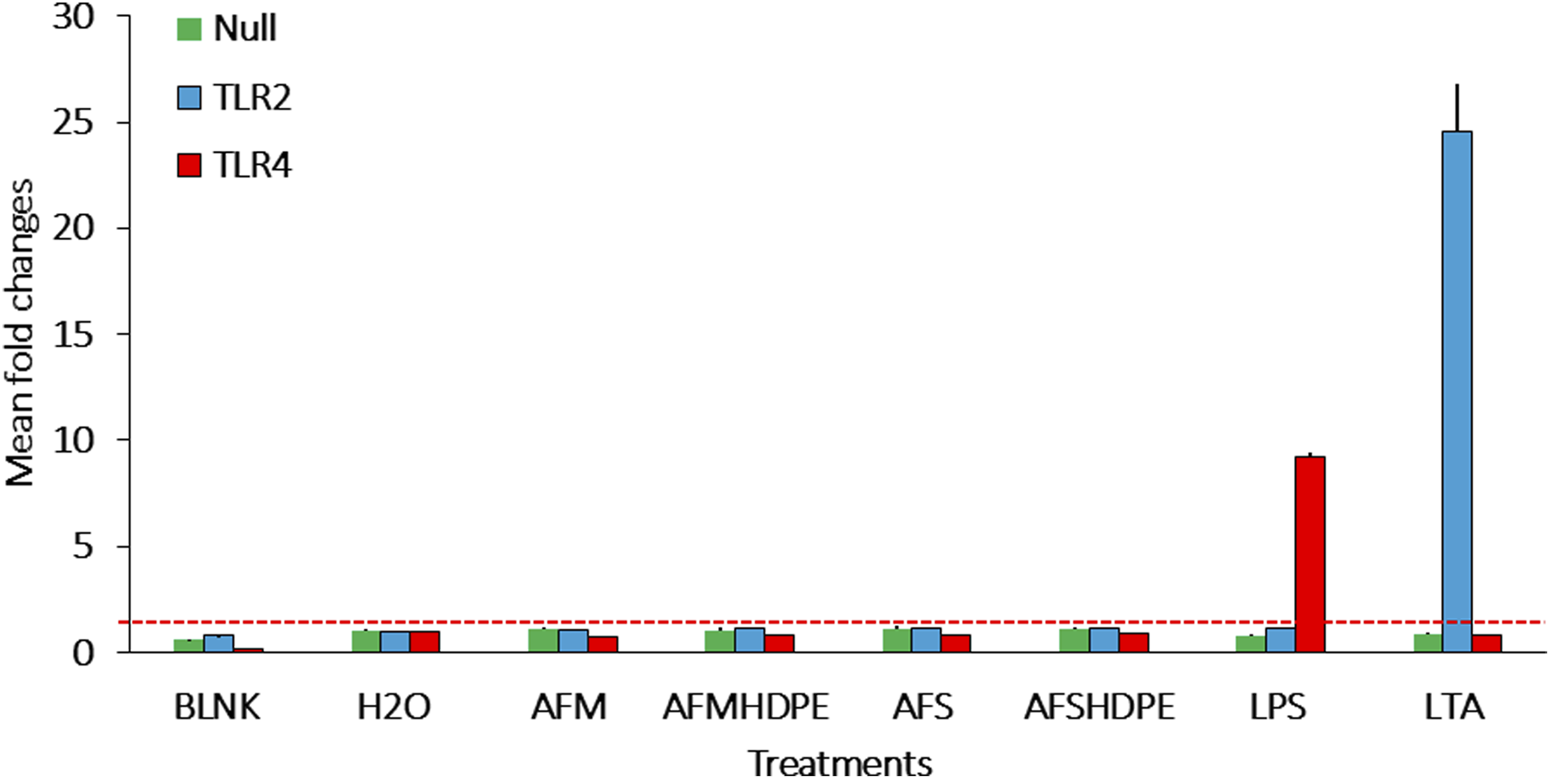

3.3 Toll-like receptor activation by HEK293 reporter cell assay

Figure 3 shows the fold change in SEAP activity after 24-h exposure of reporter cells to 106 AFM/mL or 106 AFS/mL and the mixtures of 106 AFS/mL + HDPE (100 μg/mL) and 106 AFM/mL + HDPE (100 μg/mL). The fold change was calculated by dividing the absorbance of test materials by the average of controls across two independent experiments. Following 24 h of exposure, neither TLR2 nor TLR4 was activated by any of the test materials. However, the positive controls for TLR2 and TLR4 induced significant activation of the respective TLRs. Similarly, data from the inverted insert exposure model revealed that HDPE particles do not significantly activate the two receptors (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 3

Bar plots of the fold changes following submerged exposure of reporter cells to test materials that include AFMHDPE (AFM (106/mL) + HDPE (100 μg/mL)), AFM (106/mL), AFSHDPE [AFS (106/mL) + HDPE (100 μg/mL)], AFS (106/mL) particles, H2O as the negative control, and positive controls [LPS (100 ng/mL) for TLR4 and LTA (100 ng/mL) for TLR2]. The blank control served as the background response without cells. The red stippled line indicates fold change level 2, which was considered the activation threshold. Data from two independent experiments are shown.

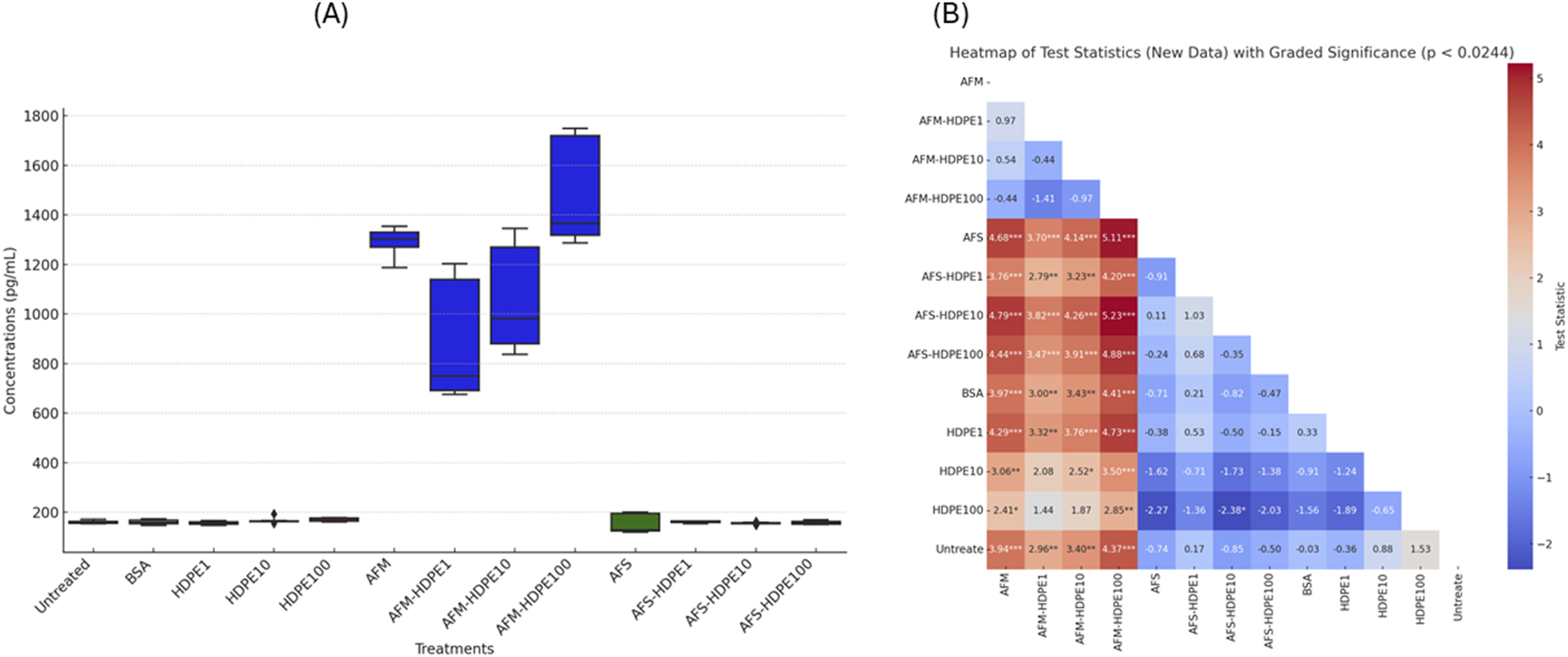

3.4 Measured pro-inflammatory markers by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Figures 4, 5 show the levels of IL-6 and IL-8 measured by ELISA in the cell medium after 24 h of exposure with dHL-60. No detectable levels of IL-6 were measured in the negative (H2O) control-treated and vehicle (BSA) control-treated cells, while levels above the detection limit were measured in the HDPE, AFM, AFS, and mixture treatments. Markedly higher levels of IL-6 and IL-8 were measured in the HDPE mixtures with AFM. With AFS mixtures and HDPE, only IL-6 was significantly released. Importantly, all the mixtures of HDPE with fungal fragments induced higher levels of IL-6 and IL-8 than HDPE alone, while AFS mixture induced only IL-8. Considering the pro-inflammatory potential of the test materials, AFM and AFM mixtures induced the highest levels of IL-6 and IL-8, followed by AFS mixtures and HDPE alone with the lowest response.

FIGURE 4

Box plots of IL-6 concentrations released (A) by the cells after 24 h of exposure to test materials and controls with (B) heatmap of test statistics. Cells were exposed to either HDPE particles alone (1–100 μg/mL) or 106 AFM/AFS particles per mL mixed with varying concentrations of HDPE (1–100 μg/mL). Comparison results of treatments using Dunn test statistics with reported FDR-adjusted p-values provided as heatmap (B). Data analysis and visualization are based on three independent experiments. (*) p-value <0.024; (**) p-value <0.01; (***) p-value <0.001.

FIGURE 5

Box plots of IL-8 concentrations released (A) by the cells after 24 h of exposure to test materials and controls with (B) heatmap of test statistics. Cells were exposed to either HDPE particles alone (1–100 μg/mL) or 106 AFM/AFS particles per mL mixed with varying concentrations of HDPE (1–100 μg/mL). Comparison results of treatments using Dunn test statistics with reported FDR-adjusted p-values provided as heatmap (B). Data visualization and analysis are based on three independent experiments. (*) p-value <0.024; (**) p-value <0.01; (***) p-value <0.001.

No significant levels of IL-6 were particularly detected with cells exposed to the vehicle control (0.0025% BSA) compared to the untreated cell control, but considerably higher levels were measured with cells exposed to 1 μg/mL HDPE. We also observed a decreasing level of IL-6 in response to increasing doses of HDPE, with the highest levels at 1 μg/mL and the lowest at 100 μg/mL. Significantly higher levels of IL-6 were induced by 1 μg/mL (but not at 10 and 100 μg/mL) HDPE alone compared to the untreated cells. IL-6 secretion was also significantly higher in cells treated with the mixtures of AFS + HDPE (1–100 μg/mL) compared to the untreated cells and vehicle controls, but the levels with AFS alone did not differ from those with the controls. Another important observation is that increasing HDPE concentrations (1–100 μg/mL) alone or in mixture with 106 AFM/mL or 106 AFS/mL induced decreasing levels of IL-6 concentrations.

For IL-8, approximately 160 ng/mL was measured in the untreated cell control, and this level was similar to the levels released by cells treated with vehicle control (0.0025% BSA), HDPE, or AFS alone. Moreover, cells exposed to 106 AFM/mL alone or in mixture with HDPE (1–100 μg/mL) released over 5× more the mean levels of IL-8 compared to the controls, HDPE, or AFS alone. The differences in the IL-8 levels released by cells treated with 106 AFM/mL and controls or HDPE alone (1–100 μg/mL) were statistically significant, but not between AFM alone and AFM mixed with HDPE (1–100 μg/mL). The increasing level of HDPE in the mixture with AFM is positively correlated with IL-8 release.

4 Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated the immunotoxicological effects of HDPE microplastics in combination with A. fumigatus particles (spores and fragments) on neutrophil functions using differentiated HL-60 cells as an in vitro model. Cells were exposed to concentration-dependent HDPE microplastics (1–100 μg/mL) co-administrated with a constant concentration (106 particles/mL) of A. fumigatus conidia (AFS) or mycelial fragments (AFM).

Cytotoxicity assessment revealed no significant acute effects on the cell viability across the tested concentration range. Similarly, pattern recognition receptor activation analysis demonstrated no significant upregulation of TLR2 and TLR4 expression following particle exposure. However, differential pro-inflammatory responses with IL-6 and IL-8 were observed, indicating particle-specific immunomodulatory effects. The secretion of IL-6 showed a bimodal dose–response relationship in AFM–HDPE co-exposures, with peak release at the lowest HDPE concentrations (1 μg/mL + 106 AFM/mL) and significant attenuation at the highest concentration (100 μg/mL HDPE + 106 AFM/mL). In contrast, IL-8 release demonstrated a positive dose-dependent relationship with increasing HDPE concentrations (1–100 μg/mL) exclusively in the presence of AFM particles. Although not statistically significant, the addition of HDPE at two lower doses (1 and 10 μg/mL) seemed to induce a reduction in IL-8 levels relative to AFM alone. This suggests a two-phase effect such as hormesis responses with the HDPE microplastics; however, further experimental studies are required for any consistent conclusion. Notably, HDPE–conidia mixtures did not elicit considerable IL-8 responses, suggesting morphotype-specific inflammatory potential.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to reveal such differential effects of fungal particle morphotypes in the presence of HDPE microplastics. Our findings suggest additive inflammatory effects between HDPE microplastics and A. fumigatus mycelial fragments, as evidenced by enhanced IL-8 release in co-exposure scenarios compared to individual particle treatments. These results highlight the importance of considering particle morphology and co-contaminant interactions in environmental health risk assessments.

None of the tested materials and combinations negatively affected the neutrophil-like cell viability. The tested doses of HDPE particles alone or in mixture with fungal particles revealed no significant alteration of the neutrophil-like cell viability after 24 h of exposure. This result can be explained by the relatively low numbers of fungal particles per neutrophil cells (three fungal particles per cell). In fact, 15 µL of 106 particles/mL was used per well, which is equivalent to 15,000 particles per 5,000 cells per well or 3 particles per cell. Similar results were obtained with even much higher fungal particle concentrations (spores and fragments from A. fumigatus) with THP1 macrophages (1,400 particles per cell) (Øya et al., 2018) and in mature human macrophages exposed to HDPE particles (Xing et al., 2002). However, contradictory results were found by Herrala et al. (2023), who exposed gastrointestinal cells to micro-sized PE particles and ethanol-extracted compounds from the particles. Their results revealed that the micro-sized PE particles and the ethanol-extracted compounds reduced cell viability and increased oxidative stress when intestinal cells were exposed to high concentrations (0.25–1 mg/mL) of test materials. The relatively higher doses (>200 μg/mL) used by Herrala et al. may explain such discrepancy as they only observed decreasing cell viability from 500 μg/mL. Although cytotoxicity is the basic toxicity parameter commonly used to evaluate potential hazards of any suspected component, most of the particulate matter pollutants, at environmentally relevant exposure doses, do not cause acute cell death or alter cell viability in vitro. However, these exposure agents can induce many immune responses that, if not regulated back to homeostasis, can lead to diseases.

As summarized in Figure 3, co-exposure of HEK293 reporter cells to 106 fungal particles/mL and 100 μg/mL HDPE microplastics did not activate TLR2 or TLR4. This result is in contradiction with previously reported data on A. fumigatus, revealing significant TLR2- and TLR4-dependent immune responses in macrophages (Meier et al., 2003). This discrepancy may be attributed to two factors. First, the doses applied in the present study are six times lower than those used by Meier et al. We consider the dose of fungal particles tested in our study as a more environmentally relevant exposure dose (Eduard, 2009). The second factor is heat inactivation applied to the fungal materials, which was implemented as a safety measure during the handling of A. fumigatus particles as well as to prevent invasion of the cell culture medium. As fungal walls are adorned with a variety of proteins that can act as ligands for immune receptors, including TLRs, heat treatment may significantly alter the conformation of such protein ligands, in the way that their affinity to receptors of the immune system was lost (Ibe and Munro, 2021). In fact, thermal denaturation can significantly impact the three-dimensional structure of protein ligands, which are crucial for their recognition by immune receptors, such as TLRs (Van De Veerdonk et al., 2008).

From the cells exposed to HDPE–AFM, the secretion of IL-8 markedly increased compared to the negative control, HDPE microplastics, and AFS treatments. This can be attributed to the A. fumigatus spores’ ability to evade the immune system due to the hydrophobin protecting layer, which is absent in hyphal structures. The exposed mycelium is not protected from detection by PRRs (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020) and thus capable of inducing pro-inflammatory responses (Øya et al., 2018). Data similar to our findings on IL-8 secretion were reported with polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells exposed to fungal particles (Braedel et al., 2004). Although not investigated in the present study, it is likely that IL-8 secretion may be initiated through dectin-1 receptor activation (Meier et al., 2003; Werner et al., 2009), but not through TLR2 and TLR4, as previously reported (Meier et al., 2003). It is well established that binding to TLRs mediates expression and secretion of cytokines in sentinel cells (El-Zayat et al., 2019). It is also known that A. fumigatus antigens activate TLR2 and TLR4, but it remains unclear whether MNPs interact with similar receptors in immune cells (Blackburn and Green, 2022; Braedel et al., 2004).

TLRs are one of the most important receptor families for detection of pathogens and foreign objects among sentinel cells (Seitz, 2003). Neutrophils and the dHL-60 neutrophilic cell model are both reported to express TLR2 and TLR4 (Saegusa et al., 2009; Shuto et al., 2007). In particular, TLR2 and TLR4 are important receptors for detection of cell wall microbial components, such as LPS and LTA from bacteria, along with chitin and zymosan from fungi. LTA (from bacteria) and zymosan (from fungi) can induce immune responses through TLR2 activation (Ikeda et al., 2008), while LPS from bacteria binds to TLR4. As summarized in Figure 3, neither AFM nor AFS bound to any of these receptors. In the case of AFS, this was expected as undamaged and non-germinated A. fumigatus spores are protected by a layer of the immunological insert polymer, thus enabling it to evade most immune receptors (Garcia-Rubio et al., 2020). However, the AFM particles prepared by grinding the A. fumigatus mycelium do not have this type of protective layer. A. fumigatus can induce the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a TLR2- and TLR4-dependent manner in macrophages (Meier et al., 2003). Similarly, neutrophils can detect A. fumigatus via TLR2 and TLR4 receptors in humans (Braedel et al., 2004). No significant stimulation of TLR2 or TLR4 by AFM or AFS was observed using HEK293 reporter cells, suggesting that the doses used here may either be too low or that the pre-treatment of the particles have altered the three-dimensional structure, thus preventing binding to these receptors. In neutrophils and the dHL-60 neutrophil-like cell models, other receptors are responsible for detection of beta-glucans in the A. fumigatus mycelium (Kennedy et al., 2007; Saegusa et al., 2009; Werner et al., 2009), which may drive the release of the pro-inflammatory markers.

Microplastics, consistent with other environmental particulate contaminants, elicit robust inflammatory reactions and immune dysfunction across multiple biological scales, from cellular to systemic responses in human populations. Such states are characterized by elevated secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α) and chemokines (IL-8), and enhanced activation of immune effector cells, particularly tissue-resident macrophages and circulating neutrophils (Pulvirenti et al., 2022; Tomonaga et al., 2024). Chronic inflammation is a well-established contributor to endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis, and the progression of many other chronic diseases (Abbas et al., 2025).

In ambient air and occupational settings, dust exposure generally includes heterogeneous mixtures of diverse particle populations varying in sizes, distribution, morphology, and origins. Although comprehensive characterization of these complex exposure matrices remains incomplete in the scientific literature, mounting evidence suggests that contemporary particulate dust pollution includes microplastics, now recognized as contaminants of emerging concern, alongside fungal bioaerosols with well-characterized immunogenic, allergenic, and toxinogenic properties (Vishwakarma et al., 2023; Yakovenko et al., 2025; Yan et al., 2016).

As the first study of its kind, we investigated the immune-modulating effects of HDPE microplastics and fungal particles in neutrophil-like cells. We hypothesized that mixtures of microplastics and fungal particles, likely representing co-occurring components of outdoor, indoor, and occupational dust, would elicit stronger pro-inflammatory responses than microplastics alone. In fact, particle mixtures consisting of HDPE + AFM (fungal mycelial fragments) induced significantly higher levels of IL-6 and IL-8 than HDPE particles alone. This is not, however, the case with HDPE + AFS (fungal spores) or fungal spores that induced the release of only IL-8. Surprisingly, we observed a decreasing level of IL-6 when the doses of HDPE particles increased, even in combination with fungal particles. These findings are in line with the results reported by Boynton et al. (2000), who also exposed monocyte-derived macrophages to HDPE and reported the release of IL-6. In our study, there is a clear negative trend with measured levels of IL-6 and all treatments containing increasing doses of HDPE. This observation can be attributed to potential loss of secreted IL-6 by adsorption to the test materials, particularly to HDPE, as previously reported for other test materials (Kocbach et al., 2008). Similar findings for IL-6 and TNF-α were reported with PBMCs exposed to PVC and ABS (Han et al., 2020), but not discussed. The cause of such a response remains unclear, and the relationship between increasing microplastic levels and decreasing IL-6 levels, also known as pleiotropic cytokine, cannot be interpreted as a simple cause-and-effect inflammatory response. Instead, it may be a multifaceted reaction influenced by a delicate interplay between various factors of the exposure systems and the microplastic constituents. Although the pro-inflammatory potential of microplastics is commonly reported as a significant concern, evidence also suggests that they can attenuate immune function, especially adaptive immune responses, under specific circumstances (Hua and Wang, 2022). The potential of microplastics to dysregulate the immune system, leaving us more vulnerable to infections and other diseases, represents an insidious threat to human health. As an example, Gupta et al. (2021) showed that increased exposure to particulate matter is associated with increased lethality of COVID-19. Another critical cofounder of this relationship is the increased opportunistic infections such as mucormycosis (Azhar et al., 2022).

Fungal fragments of mycelial origin induced the secretion of the highest levels of IL-6 and IL-8. These results are in line with data reported by Øya et al. (2019) with bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) and macrophages. A. fumigatus is a well-characterized model of mold pathogen with pro-inflammatory properties that differ significantly whether the mold is at the mycelia or spore stage. Treatment with the fungal fragments showed the higher levels of measured pro-inflammatory cytokines than fungal spores. This finding corroborates with previous studies reviewed by Pulvirenti et al. (2022).

Another interesting observation is that fungal spores alone induced the release of IL-6 but not IL-8. When co-exposed with HDPE, the opposite response, with the release of IL-8 but not IL-6, was found. These results can be explained by the fact that fungal spores by themselves elicit weak or marginal IL-6 responses and little to no IL-8 responses (Øya et al., 2019), while plastic particles, as revealed for polystyrene microplastics, tend to induce IL-8 production (Mattioda et al., 2023). It is likely that the fungal spores alone trigger a pyrogenic-like response with IL-6 release, whereas in the presence of microplastics IL-8 release is induced, a response that is often characterized as particle effects (Dinarello, 1999).

The inflammatory reactions observed in the present study cannot be used for risk assessment as the neutrophil-like cells used here were differentiated from HL-60 cells of cancerous origin and therefore do not represent a healthy biological system. The HEK293-TLR reporter cells represent an affordable TLR-specific reporter model that are relatively cheap and effective for studying receptor- and pathway-specific responses of the innate immune system in vitro. The data generated here can help cover, at mechanistic levels, some of the knowledge gaps of hazards associated with exposure to environmentally relevant microplastics and particularly HDPE MPs. It is, however, important to note that the degree of sensitivity of the HEK293 reporter cell model may be less than that of immune cells responsible for innate immune responses (for example, neutrophils) to pathogen-associated microbial patterns.

5 Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the potential immunotoxic effects associated with microplastic particles in mixture with fungal spores or fungal fragments. Although no cytotoxic effects were observed at the tested doses in the neutrophil-like cell model, pro-inflammatory responses characterized by differential release of IL-6 and IL-8 were found when microplastics were mixed with fungal fragments or spores. Our findings suggest that microbial contaminants, here fungal particles, seem to be the main drivers of the immune responses triggered by combined exposure to HDPE microplastics and fungal particles. In particular, fungal mycelial fragments alone or in mixtures were more potent with significant release of both IL-6 and IL-8 compared to fungal spores that induced only significant release of IL-8. Of note, fungal spores are commonly monitored in risk assessments. Altogether, no or limited effects could be found after exposure to the “pristine” HDPE particles, but exposure to complex mixtures of HDPE and fungal fragments induced significant release of pro-inflammatory markers from the neutrophil-like cells.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. FB: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. IZ: Investigation, Writing – review and editing. AC: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. ØH: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. SZ-N: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was funded by the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under the Grant Agreement number 965367 (PlasticsFatE project).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Håkan Wallin for his advice and Hamed Sadeghiankaffash for the help with inverted insert Transwell systems.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. To improve readability.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ftox.2026.1718466/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Abbas G. Ahmed U. Ahmad M. A. (2025). Impact of microplastics on human health: risks, diseases, and affected body systems. Microplastics4 (2), 23. 10.3390/microplastics4020023

2

Adler K. B. Wright D. T. Becker S. (1994). Interactions between respiratory epithelial cells and cytokines: relationships to lung inflammation a. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.28 (725), 128–145. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb00275.x

3

Afanou K. A. Straumfors A. Skogstad A. Nilsen T. Synnes O. Skaar I. et al (2014). Submicronic fungal bioaerosols: high-resolution microscopic characterization and quantification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.80, 7122–7130. 10.1128/aem.01740-14

4

Allermann L. Poulsen O. M. (2000). Inflammatory potential of dust from waste handling facilities measured as IL-8 secretion from lung epithelial cells in vitro. Anal. Occ. Hygen44 (4), 259–269.

5

Amato-Lourenço L. F. Dantas K. C. Júnior G. R. Paes V. R. Ando R. A. De Oliveira Freitas R. et al (2024). Microplastics in the olfactory bulb of the human brain. JAMA Netw. Open7 (9), e2440018. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40018

6

Azhar A. Khan W. H. Khan P. A. Alhosaini K. Owais M. Ahmad A. (2022). Mucormycosis and COVID-19 pandemic: clinical and diagnostic approach. J. Infect. Public Health15, 466–479. 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.02.007

7

Beijer N. R. M. Dehaut A. Carlier M. P. Wolter H. Versteegen R. M. Pennings J. L. A. et al (2022). Relationship between particle properties and immunotoxicological effects of environmentally-sourced microplastics. Front. Water4, 866732. 10.3389/frwa.2022.866732

8

Beisswenger C. Hess C. Bals R. (2012). Aspergillus fumigatusconidia induce interferon-β signalling in respiratory epithelial cells. Eur. Respir. J.39, 411–418. 10.1183/09031936.00096110

9

Blackburn K. Green D. (2022). The potential effects of microplastics on human health: what is known and what is unknown. Ambio51, 518–530. 10.1007/s13280-021-01589-9

10

Blanter M. Gouwy M. Struyf S. (2021). Studying neutrophil function in vitro: cell models and environmental factors. JIR14, 141–162. 10.2147/jir.s284941

11

Boynton E. L. Waddell J. Meek E. Labow R. S. Edwards V. Santerre J. P. (2000). The effect of polyethylene particle chemistry on human monocyte-macrophage functionin vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.52, 239–245. 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2%253C239::aid-jbm1%253E3.0.co;2-r

12

Braedel S. Radsak M. Einsele H. Latgé J. Michan A. Loeffler J. et al (2004). Aspergillus fumigatus antigens activate innate immune cells via toll‐like receptors 2 and 4. Br. J. Haematol.125, 392–399. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04922.x

13

Brummelman J. Veerman R. E. Hamstra H. J. Deuss A. J. M. Schuijt T. J. Sloots A. et al (2015). Bordetella pertussis naturally occurring isolates with altered lipooligosaccharide structure fail to fully mature human dendritic cells. Infect. Immun.83, 227–238. 10.1128/iai.02197-14

14

Chinglenthoiba C. Lani M. N. Anuar S. T. Amesho K. T. T. K L P. Santos J. H. (2025). Microplastics in food packaging: analytical methods, health risks, and sustainable alternatives. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv.18, 100746. 10.1016/j.hazadv.2025.100746

15

Devalia J. L. (1993). Airway epithelial cells and mediators of inflammation. Respir. Med.85, 405–408.

16

Dinarello C. A. (1999). Cytokines as endogenous pyrogens. J. Infect. Dis.179, S294–S304. 10.1086/513856

17

Dris R. Gasperi J. Mirande C. Mandin C. Guerrouache M. Langlois V. et al (2017). A first overview of textile fibers, including microplastics, in indoor and outdoor environments. Env. Pollut.221, 453–458. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.013

18

Eduard W. (2009). Fungal spores: a critical review of the toxicological and epidemiological evidence as a basis for occupational exposure limit setting. Crit. Rev. Toxicol.39, 799–864. 10.3109/10408440903307333

19

Eduard W. Aalen O. (1988). The effect of aggregation on the counting precision of mould spores on filters. Ann. Occup. Hyg.32 (4), 445–567. 10.1093/annhyg/32.4.471

20

El-Zayat S. R. Sibaii H. Mannaa F. A. (2019). Toll-like receptors activation, signaling, and targeting: an overview. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent.43, 187. 10.1186/s42269-019-0227-2

21

Feldman M. B. Dutko R. A. Wood M. A. Ward R. A. Leung H. M. Snow R. F. et al (2020). Aspergillus fumigatus cell wall promotes apical airway epithelial recruitment of human neutrophils. Infect. Immun.88 (2), e00813–e00819. 10.1128/IAI.00813-19

22

Galloway T. S. Cole M. Lewis C. (2017). Interactions of microplastic debris throughout the marine ecosystem. Nat. Ecol. Evol.1, 0116. 10.1038/s41559-017-0116

23

Garcia-Rubio R. De Oliveira H. C. Rivera J. Trevijano-Contador N. (2020). The fungal cell wall: candida, cryptococcus, and aspergillus species. Front. Microbiol.10, 2993. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02993

24

Gkoutselis G. Rohrbach S. Harjes J. Obst M. Brachmann A. Horn M. A. et al (2021). Microplastics accumulate fungal pathogens in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Rep.11, 13214. 10.1038/s41598-021-92405-7

25

Gkoutselis G. Rohrbach S. Harjes J. Brachmann A. Horn M. A. Rambold G. (2024). Plastiphily is linked to generic virulence traits of important human pathogenic fungi. Commun. Earth Environ.5, 51. 10.1038/s43247-023-01127-3

26

Gupta A. Bherwani H. Gautam S. Anjum S. Musugu K. Kumar N. et al (2021). Air pollution aggravating COVID-19 lethality? Exploration in Asian cities using statistical models. Environ. Dev. Sustain23, 6408–6417. 10.1007/s10668-020-00878-9

27

Han S. Bang J. Choi D. Hwang J. Kim T. Oh Y. et al (2020). Surface pattern analysis of microplastics and their impact on human-derived cells. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater.2, 4541–4550. 10.1021/acsapm.0c00645

28

Hayashi F. Means T. K. Luster A. D. (2003). Toll-like receptors stimulate human neutrophil function. Blood102, 2660–2669. 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1078

29

Herrala M. Huovinen M. Järvelä E. Hellman J. Tolonen P. Lahtela-Kakkonen M. et al (2023). Micro-sized polyethylene particles affect cell viability and oxidative stress responses in human colorectal adenocarcinoma Caco-2 and HT-29 cells. Sci. Total Environ.867, 161512. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.161512

30

Hirt N. Body-Malapel M. (2020). Immunotoxicity and intestinal effects of nano- and microplastics: a review of the literature. Part Fibre Toxicol.17, 57. 10.1186/s12989-020-00387-7

31

Holme J. A. Øya E. Afanou A. K. J. Øvrevik J. Eduard W. (2020). Characterization and pro‐inflammatory potential of indoor mold particles. Indoor Air30, 662–681. 10.1111/ina.12656

32

Hu C. J. Garcia M. A. Nihart A. Liu R. Yin L. Adolphi N. et al (2024). Microplastic presence in dog and human testis and its potential association with sperm count and weights of testis and epididymis. Toxicol. Sci.200, 235–240. 10.1093/toxsci/kfae060

33

Hua X. Wang D. (2022). Cellular uptake, transport, and organelle response after exposure to microplastics and nanoplastics: current knowledge and perspectives for environmental and health risks. Rev. Env. Contamination Formerly: Residue Rev.260, 12. 10.1007/s44169-022-00013-x

34

Huang H. Hou J. Liao Y. Wei F. Xing B. (2023). Polyethylene microplastics impede the innate immune response by disrupting the extracellular matrix and signaling transduction. iScience26 (8), 107390. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107390

35

Ibe C. Munro C. A. (2021). Fungal cell wall proteins and signaling pathways form a cytoprotective network to combat stresses. JoF7, 739. 10.3390/jof7090739

36

Ikeda Y. Adachi Y. Ishii T. Miura N. Tamura H. Ohno N. (2008). Dissociation of toll-like receptor 2-Mediated innate immune response to Zymosan by organic solvent-treatment without loss of Dectin-1 reactivity. Biol. Pharm. Bull.31, 13–18. 10.1248/bpb.31.13

37

Islam M. Kabir M. Ahmed S. (2024). Immunomodulatory and biochemical alterations in chick embryos exposed to polystyrene microplastics. J. Res. Vet. Sci.2 (4), 182–191. 10.5455/jrvs.20240508055748

38

Jenner L. C. Rotchell J. M. Bennett R. T. Cowen M. Tentzeris V. Sadofsky L. R. (2022). Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ.831, 154907. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154907

39

Jiang B. Kauffman A. E. Li L. McFee W. Cai B. Weinstein J. et al (2020). Health impacts of environmental contamination of micro- and nanoplastics: a review. Environ. Health Prev. Med.25, 29. 10.1186/s12199-020-00870-9

40

Johansson C. Kirsebom F. C. M. (2021). Neutrophils in respiratory viral infections. Mucosal Immunol.14, 815–827. 10.1038/s41385-021-00397-4

41

Joo S. H. Liang Y. Kim M. Byun J. Choi H. (2021). Microplastics with adsorbed contaminants: mechanisms and treatment. Environ. Challenges3, 100042. 10.1016/j.envc.2021.100042

42

Jung W. Yang M.-J. Kang M.-S. Kim J.-B. Yoon K.-S. Yu T. et al (2025). Chronic lung tissue deposition of inhaled polyethylene microplastics may lead to fibrotic lesions. Toxicol. Rep.15, 102111. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.102111

43

Kennedy A. D. Willment J. A. Dorward D. W. Williams D. L. Brown G. D. DeLeo F. R. (2007). Dectin‐1 promotes fungicidal activity of human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol.37, 467–478. 10.1002/eji.200636653

44

Klauer R. R. Silvestri R. White H. Hayes R. D. Riley R. Lipzen A. et al (2024). Hydrophobins from Aspergillus mediate fungal interactions with microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol., 2024.11.05.622132. 10.1101/2024.11.05.622132

45

Kocbach A. Totlandsdal A. I. Låg M. Refsnes M. Schwarze P. E. (2008). Differential binding of cytokines to environmentally relevant particles: a possible source for misinterpretation of in vitro results?Toxicol. Lett.176, 131–137. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.10.014

46

Kolaczkowska E. Kubes P. (2013). Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol.13, 159–175. 10.1038/nri3399

47

Kontro M. H. Kirsi M. Laitinen S. K. (2022). Exposure to bacterial and fungal bioaerosols in facilities processing biodegradable waste. Front. Public Health10, 789861. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.789861

48

Latgé J.-P. (2001). The pathobiology of Aspergillus fumigatus. Trends Microbiol.9, 382–389. 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02104-7

49

Latgé J.-P. Chamilos G. (2019). Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.33. 10.1128/cmr.00140-18

50

Leslie H. A. Van Velzen M. J. M. Brandsma S. H. Vethaak A. D. Garcia-Vallejo J. J. Lamoree M. H. (2022). Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int.163, 107199. 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107199

51

Li X. Liu D. Yao J. (2022). Aerosolization of fungal spores in indoor environments. Sci. Total Environ.820, 153003. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153003

52

Li H. Liu H. Bi L. Liu Y. Jin L. Peng R. (2024). Immunotoxicity of microplastics in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol.150, 109619. 10.1016/j.fsi.2024.109619

53

Manda‐Handzlik A. Bystrzycka W. Wachowska M. Sieczkowska S. Stelmaszczyk‐Emmel A. Demkow U. et al (2018). The influence of agents differentiating HL‐60 cells toward granulocyte‐like cells on their ability to release neutrophil extracellular traps. Immunol. Cell Biol.96, 413–425. 10.1111/imcb.12015

54

Marfella R. Prattichizzo F. Sardu C. Fulgenzi G. Graciotti L. Spadoni T. et al (2024). Microplastics and nanoplastics in atheromas and cardiovascular events. N. Engl. J. Med.390, 900–910. 10.1056/nejmoa2309822

55

Mattioda V. Benedetti V. Tessarolo C. Oberto F. Favole A. Gallo M. et al (2023). Pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic effects of polystyrene microplastics on human and Murine intestinal cell lines. Biomolecules13, 140. 10.3390/biom13010140

56

McCormick A. Hoellein T. J. Mason S. A. Schluep J. Kelly J. J. (2014). Microplastic is an abundant and distinct microbial habitat in an urban river. Environ. Sci. Technol.48, 11863–11871. 10.1021/es503610r

57

McGovern T. K. Chen M. Allard B. Larsson K. Martin J. G. Adner M. (2016). Neutrophilic oxidative stress mediates organic dust-induced pulmonary inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am. J. Physiology-Lung Cell. Mol. Physiology310, L155–L165. 10.1152/ajplung.00172.2015

58

Meier A. Kirschning C. J. Nikolaus T. Wagner H. Heesemann J. Ebel F. (2003). Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 are essential for Aspergillus-induced activation of murine macrophages. Cell Microbiol.5, 561–570. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00301.x

59

Mitrano D. M. Wohlleben W. (2020). Microplastic regulation should be more precise to incentivize both innovation and environmental safety. Nat. Commun.11, 5324. 10.1038/s41467-020-19069-1

60

Mousavi B. Hedayati M. T. Hedayati N. Ilkit M. Syedmousavi S. (2016). Aspergillus species in indoor environments and their possible occupational and public health hazards. Curr. Med. Mycol.2, 36–42. 10.18869/acadpub.cmm.2.1.36

61

Naz S. Chatha A. M. M. Khan N. A. Ullah Q. Zaman F. Qadeer A. et al (2024). Unraveling the ecotoxicological effects of micro and nano-plastics on aquatic organisms and human health. Front. Environ. Sci.12, 1390510. 10.3389/fenvs.2024.1390510

62

Nihart A. J. Garcia M. A. El Hayek E. Liu R. Olewine M. Kingston J. D. et al (2025). Bioaccumulation of microplastics in decedent human brains. Nat. Med.31, 1114–1119. 10.1038/s41591-024-03453-1

63

Øya E. Afanou A. K. J. Malla N. Uhlig S. Rolen E. Skaar I. et al (2018). Characterization and pro-inflammatory responses of spore and hyphae samples from various mold species. Indoor Air28, 28–39. 10.1111/ina.12426

64

Øya E. Becher R. Ekeren L. Afanou A. K. J. Øvrevik J. Holme J. A. (2019). Pro-inflammatory responses in human bronchial epithelial cells induced by spores and hyphal fragments of common damp indoor molds. IJERPH16 (6), 1085. 10.3390/ijerph16061085

65

Park K.-M. Kim B. Woo W. Kim L. K. Hyun Y.-M. (2024). Polystyrene microplastics induce activation and cell death of neutrophils through strong adherence and engulfment. J. Hazard. Mater.480, 136100. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136100

66

Polenogova O. V. Simakova A. V. Klementeva T. N. Varenitsina A. A. Andreeva Y. V. Babkina I. B. et al (2025). Effects of microplastics on the physiology of living organisms on the example of laboratory reared bloodsucking mosquitoes aedes aegypti L. Physiol. Entomol.50, 128–138. 10.1111/phen.12474

67

Prata J. C. Castro J. L. Da Costa J. P. Duarte A. C. Rocha-Santos T. Cerqueira M. (2020). The importance of contamination control in airborne fibers and microplastic sampling: experiences from indoor and outdoor air sampling in Aveiro, Portugal. Mar. Pollut. Bull.159, 111522. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111522

68

Pulvirenti E. Ferrante M. Barbera N. Favara C. Aquilia E. Palella M. et al (2022). Effects of nano and microplastics on the inflammatory process: in vitro and in vivo studies systematic review. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed)27 (10), 287. 10.31083/j.fbl2710287

69

Ragusa A. Matta M. Cristiano L. Matassa R. Battaglione E. Svelato A. et al (2022). Deeply in plasticenta: presence of microplastics in the intracellular compartment of human placentas. IJERPH19 (18), 11593. 10.3390/ijerph191811593

70

Ramsperger A. F. R. M. Narayana V. K. B. Gross W. Mohanraj J. Thelakkat M. Greiner A. et al (2020). Environmental exposure enhances the internalization of microplastic particles into cells. Sci. Adv.6. 10.1126/sciadv.abd1211

71

Saegusa S. Totsuka M. Kaminogawa S. Hosoi T. (2009). Saccharomyces cerevisiaeandCandida albicansStimulate cytokine secretion from human neutrophil-like HL-60 cells differentiated with retinoic acid or dimethylsulfoxide. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.73, 2600–2608. 10.1271/bbb.90410

72

Sato M. Sano H. Iwaki D. Kudo K. Konishi M. Takahashi H. et al (2003). Direct binding of toll-like receptor 2 to Zymosan, and Zymosan-induced NF- B activation and TNF- secretion are down-regulated by lung collectin surfactant protein A. J. Immunol.171 (1), 417–425. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.417

73

Schlosser O. Robert S. Debeaupuis C. (2016). Aspergillus fumigatus and mesophilic moulds in air in the surrounding environment downwind of non-hazardous waste landfill sites. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health219, 239–251. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2016.02.003

74

Seitz M. (2003). Toll‐like receptors: sensors of the innate immune system. Allergy58, 1247–1249. 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00225.x

75

Sham R. L. Phatak P. D. Belanger K. A. Pa C. H. (1995). Functional properties of HMO cells matured with all-trans-retinoic acid and DMSO: differences in response to interleukin-8 and fmlp. Leukemia Res.19, 1–6. 10.1016/0145-2126(94)00063-g

76

Shuto T. Furuta T. Cheung J. Gruenert D. C. Ohira Y. Shimasaki S. et al (2007). Increased responsiveness to TLR2 and TLR4 ligands during dimethylsulfoxide-induced neutrophil-like differentiation of HL-60 myeloid leukemia cells. Leukemia Res.31, 1721–1728. 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.06.011

77

Timm M. Madsen A. M. Hansen J. V. Moesby L. Hansen E. W. (2009). Assessment of the total inflammatory potential of bioaerosols by using a granulocyte assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.75, 7655–7662. 10.1128/AEM.00928-09

78

Tomonaga T. Higashi H. Izumi H. Nishida C. Kawai N. Sato K. et al (2024). Investigation of pulmonary inflammatory responses following intratracheal instillation of and inhalation exposure to polypropylene microplastics. Part Fibre Toxicol.21, 29. 10.1186/s12989-024-00592-8

79

Van De Veerdonk F. L. Kullberg B. J. Van Der Meer J. W. Gow N. A. Netea M. G. (2008). Host–microbe interactions: innate pattern recognition of fungal pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol.11, 305–312. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.06.002

80

Vishwakarma Y. K. Gogoi M. M. Babu S. N. S. Singh R. S. (2023). How dominant the load of bioaerosols in PM2.5 and PM10: a comprehensive study in the IGP during winter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 112277–112289. 10.1007/s11356-023-29931-6

81

Werner J. L. Metz A. E. Horn D. Schoeb T. R. Hewitt M. M. Schwiebert L. M. et al (2009). Requisite role for the Dectin-1 β-Glucan receptor in pulmonary defense against Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Immunol.182, 4938–4946. 10.4049/jimmunol.0804250

82

Wolff C. M. Singer D. Schmidt A. Bekeschus S. (2023). Immune and inflammatory responses of human macrophages, dendritic cells, and T-cells in presence of micro- and nanoplastic of different types and sizes. J. Hazard. Mater.459, 132194. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132194

83

Xing S. Santerre J. P. Labow R. S. Boynton E. L. (2002). The effect of polyethylene particle phagocytosis on the viability of mature human macrophages. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.61, 619–627. 10.1002/jbm.10078

84

Xu R. Cao J. Lv H. Geng Y. Guo M. (2024). Polyethylene microplastics induced gut microbiota dysbiosis leading to liver injury via the TLR2/NF-κB/NLRP3 pathway in mice. Sci. Total Environ.917, 170518. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.170518

85

Yakovenko N. Pérez-Serrano L. Segur T. Hagelskjaer O. Margenat H. Le Roux G. et al (2025). Human exposure to PM10 microplastics in indoor air. PLoS One20, e0328011. 10.1371/journal.pone.0328011

86

Yan D. Zhang T. Su J. Zhao L.-L. Wang H. Fang X.-M. et al (2016). Diversity and composition of airborne fungal community associated with particulate matters in Beijing during haze and non-haze days. Front. Microbiol.7, 487. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00487

87

Yan Z. Liu Y. Zhang T. Zhang F. Ren H. Zhang Y. (2022). Analysis of microplastics in human feces reveals a correlation between fecal microplastics and inflammatory bowel disease status. Environ. Sci. Technol.56, 414–421. 10.1021/acs.est.1c03924

88

Yang W. Li Y. Boraschi D. (2023). Association between microorganisms and microplastics: how does it change the host–pathogen interaction and subsequent immune response?IJMS24, 4065. 10.3390/ijms24044065

89

Zhai Y. Li X. Wang T. Wang B. Li C. Zeng G. (2018). A review on airborne microorganisms in particulate matters: Composition, characteristics and influence factors. Env. Envir.113, 74–90. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.01.007

90

Zhao H. Hong X. Chai J. Wan B. Zhao K. Han C. et al (2024). Interaction between microplastics and pathogens in subsurface system: what we know So far. Water16, 499. 10.3390/w16030499

Summary

Keywords

fungal particles, high-density polyethylene microplastics, immune responses, mixed particle exposure, Toll-like receptor activation

Citation

Afanou AK, Sagen AS, Barbero F, Zanoni I, Costa A, Haugen ØP and Zienolddiny-Narui S (2026) Microplastics amplify the pro-inflammatory response to fungal mycelial fragments and spores in neutrophil-like cells. Front. Toxicol. 8:1718466. doi: 10.3389/ftox.2026.1718466

Received

03 October 2025

Revised

18 December 2025

Accepted

05 January 2026

Published

10 February 2026

Volume

8 - 2026

Edited by

Teresa Gonçalves, University of Coimbra, Portugal

Reviewed by

Vasco Branco, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Todd Stueckle, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Afanou, Sagen, Barbero, Zanoni, Costa, Haugen and Zienolddiny-Narui.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anani K. Afanou, anani.afanou@stami.no

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.