- 1Alaska Volcano Observatory, Volcano Science Center, United States Geological Survey, Anchorage, AK, United States

- 2Alaska Volcano Observatory, Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, United States

- 3Alaska Volcano Observatory, Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, Fairbanks, AK, United States

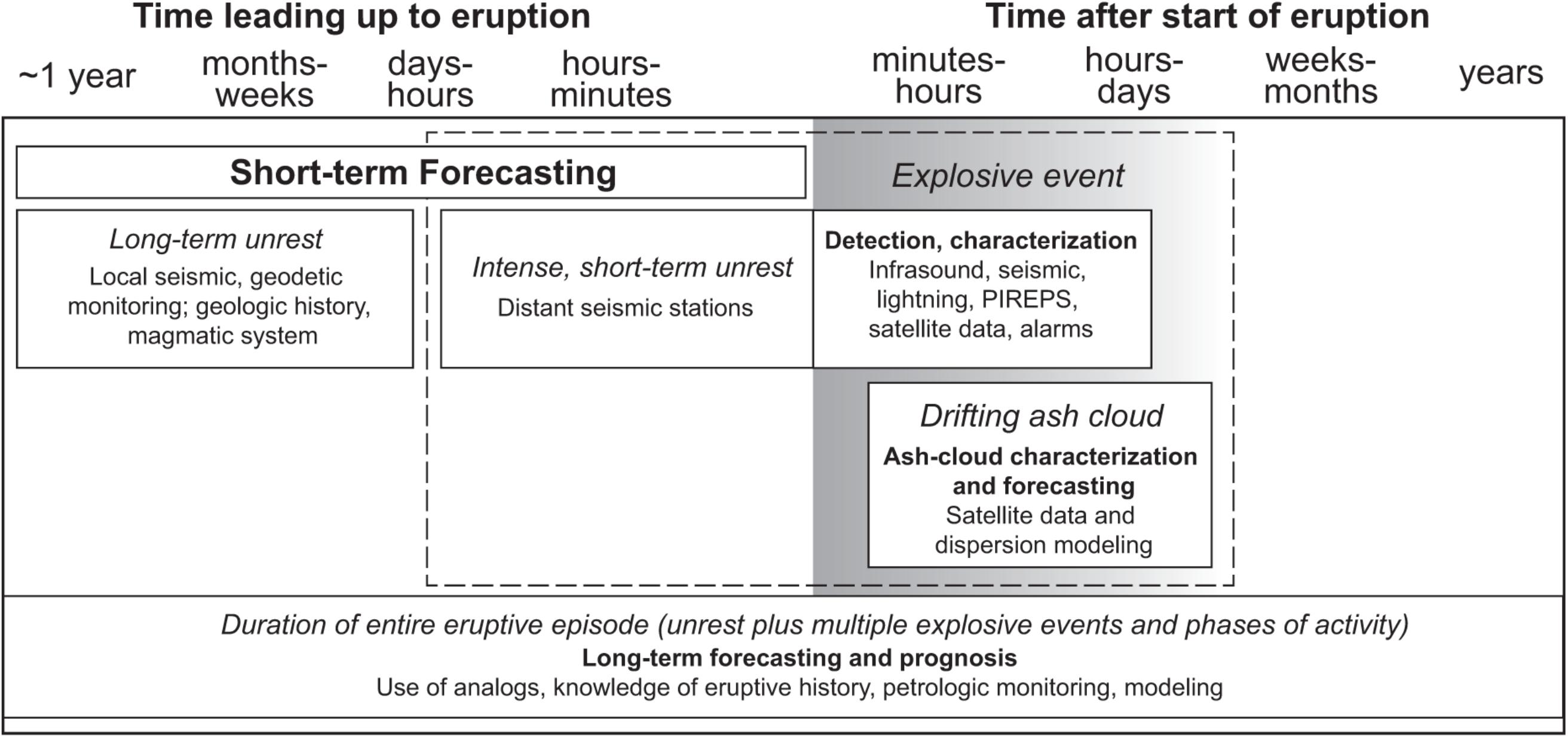

We describe a multidisciplinary approach to forecast, rapidly detect, and characterize explosive events during the 2016–2017 eruption of Bogoslof volcano, a back-arc shallow submarine volcano in Alaska’s Aleutian arc. The eruptive sequence began in December 2016 and included about 70 discrete explosive events. Because the volcano has no local monitoring stations, we used distant stations on the nearest volcanoes, Okmok (54 km) and Makushin (72 km), combined with regional infrasound sensors and lightning detection from the Worldwide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN). Pre-eruptive seismicity was detected for 12 events during the first half of the eruption; for all other events co-eruptive signals allowed for detection only. Monitoring of activity used a combination of scheduled checks combined with automated alarms. Alarms triggered on real-time data included real-time seismic amplitude measurement (RSAM); infrasound from several arrays, the closest being on Okmok; and lightning strokes detected from WWLLN within a 20-km radius of the volcano. During periods of unrest, a multidisciplinary response team of four people fulfilled specific roles to evaluate geophysical and remote-sensing data, run event-specific ash-cloud dispersion models, ensure interagency coordination, and develop and distribute of formalized warning products. Using this approach, for events that produced ash clouds ≥7.5 km above sea level, Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) called emergency response partners 15 min, and issued written notices 30 min, after event onset (mean times). Factors that affect timeliness of written warnings include event size and number of data streams available; bigger events and more data both decrease uncertainty and allow for faster warnings. In remote areas where airborne ash is the primary hazard, the approach used at Bogoslof is an effective strategy for hazard mitigation.

Introduction

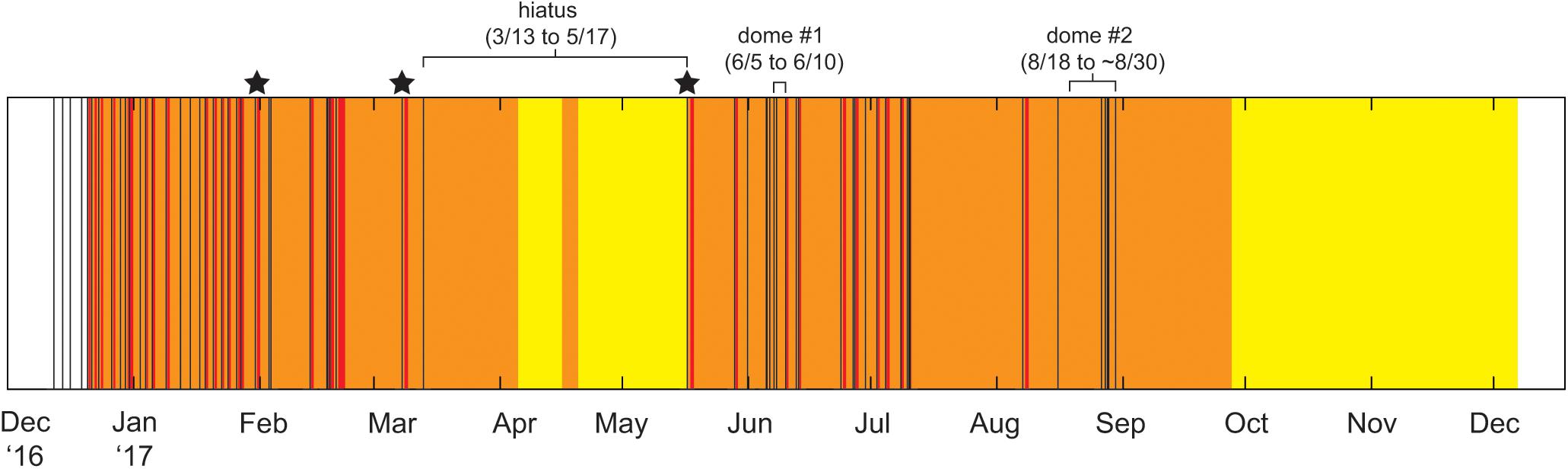

Eruption forecasting can include both long-term forecasting, which provides an overall probability of eruption at a given volcano or region over a time period of years using geologic and historical records, as well as short-term forecasting, which estimates the probability, timing, and magnitude of an impending eruption at a restless volcano (Marzocchi and Bebbington, 2012). The latter relies heavily on local instrumentation and on the interpretation and analysis of real-time or near real-time monitoring data from a volcano (Sparks, 2003). Ideally, successful short-term forecasting can allow volcano observatories to issue warnings of unrest and the possibility of a volcanic eruption hours to weeks in advance.

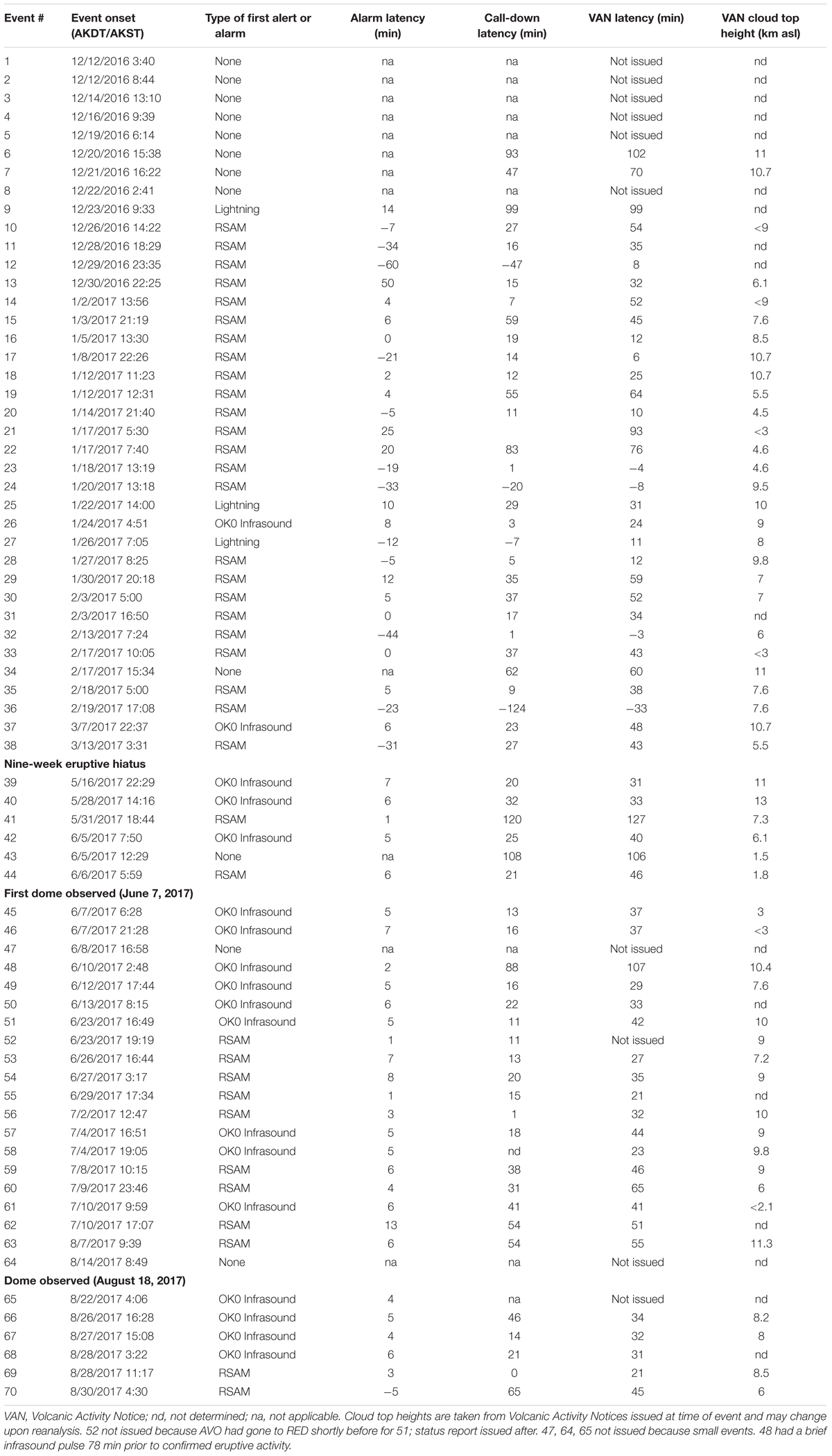

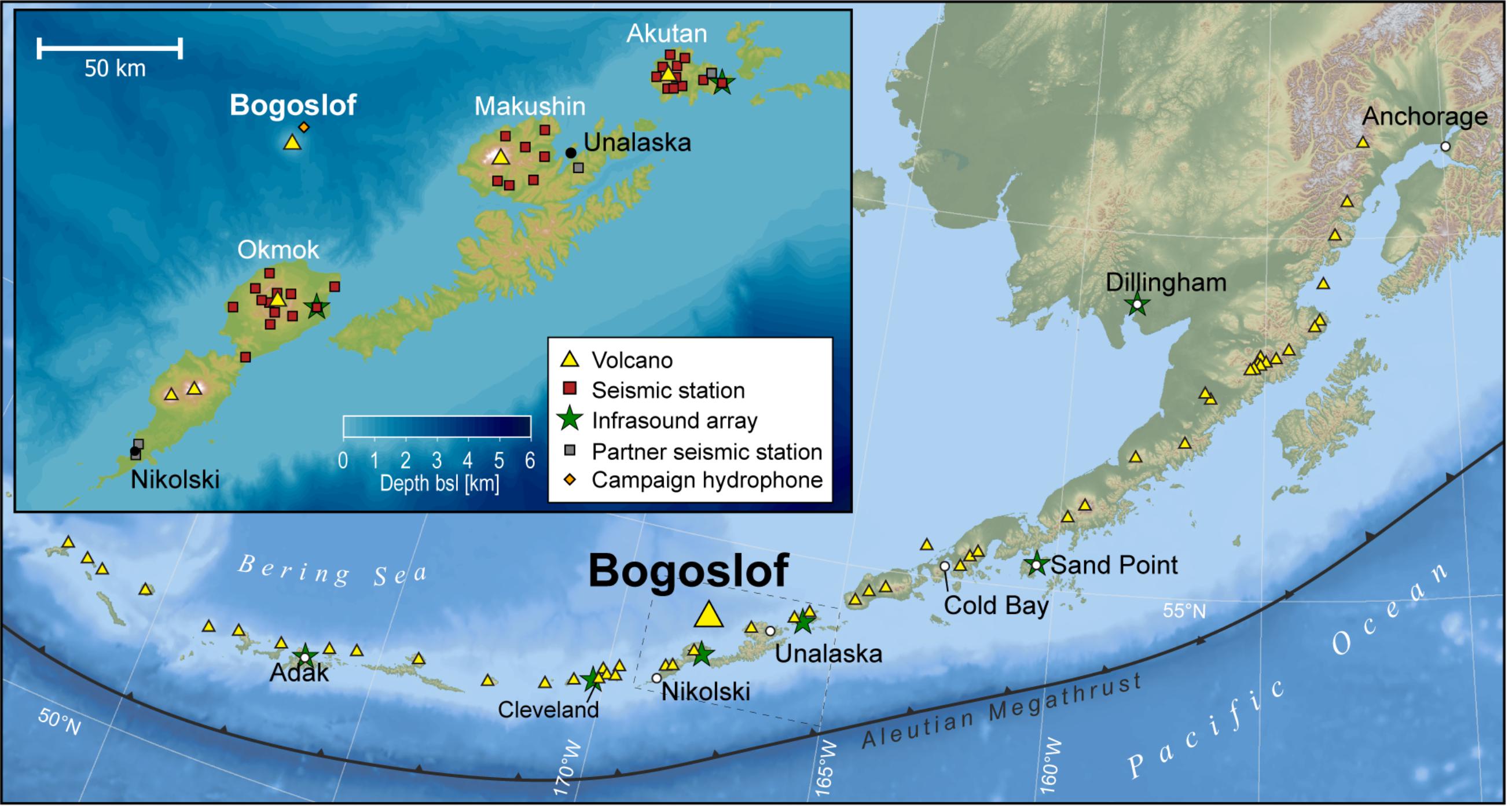

The Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) monitors volcanoes in Alaska and issues notifications and warnings of volcanic unrest and eruption. Of the over 100 volcanoes in Alaska that have been active in the Holocene, only 32 currently have geophysical monitoring networks, making short-term forecasts of volcanic activity extremely challenging (Cameron et al., 2018). In 2016, unmonitored Bogoslof volcano (Figure 1) began a 9-month-long eruptive sequence that included at least 70 explosions, each minutes to tens of minutes long, that sent ash clouds as high as 14 km above sea level (Figure 2 and Table 1). AVO was not able to forecast the beginning of the eruption; retrospective analysis shows that we missed at least four explosions in December of 2016 before being a pilot reported that the volcano was erupting. Immediately after receiving notification of the ongoing eruption, AVO implemented ad hoc, near real-time procedures to detect and forecast future explosive events. The new workflow exploited data from distant (within 100 km) seismic stations and other geophysical data streams.

FIGURE 1. Map of Alaska’s Aleutian volcanic arc, showing historically active volcanoes as yellow triangles and notable communities as white circles. The inset map shows Bogoslof Island and nearby islands with volcano-monitoring equipment used in this study.

FIGURE 2. Timeline of 2016–2017 Bogoslof eruption, showing explosive events as vertical black lines, and the aviation color code as colored bars (no color = unassigned). Stars indicate explosive events that produced reported ashfall on land or mariners.

Because Bogoslof is remote and uninhabited, like many Alaskan volcanoes, the main hazards associated with the 2016–2017 eruption were from airborne ash with potential impacts to regional and trans-Pacific aircraft and ashfall on moderately distant communities and ships navigating along local routes. Similarly to other volcanic crises, during the period of eruption at Bogoslof aviation and civil authorities require answers to some basic, but crucial, questions: When? How long? How big? Where will the ash cloud go, and will ash fall on local communities? Therefore, a timely and coordinated response, ideally providing accurate estimates of atmospheric volcanic ash transport and dispersal, is critical. AVO coordinated the determination of factors such as timing, cloud altitude and dispersal direction with the National Weather Service (NWS) Anchorage Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC), which issues volcanic ash warnings and forecasts to the aviation industry within the Alaska Flight Information Region. AVO also provides guidance about ashfall to the NWS Anchorage Forecast Office, which issues ashfall statements, advisories, and warnings for the public on the ground and marine communities.

This paper describes the geophysical data streams used to evaluate unrest, as well as the protocols to communicate information about volcanic activity and hazards during explosive activity at Bogoslof in 2016 and 2017. We focus on short-term forecasting in the hours to minutes prior to discrete explosive events, detection as soon as possible after onset (typically within minutes), and characterization in the minutes to tens of minutes after event onset (Figure 3). We highlight the combined use of a variety of automated alarms on seismic, infrasound, lightning, and remote sensing data that allowed us to respond to the sequence without 24/7 staffing at the observatory. We also present the timing of our information products relative to event onsets, and analyze the factors that can improve timeliness of warnings.

FIGURE 3. Generalized timeline illustrating different components of short-term volcano forecasting. In this paper, we focus on the events that occur within the hours and minutes just prior to and after the onset of an explosive event (dashed box): very short-term eruption forecasting, event detection, and event and ash-cloud characterization.

The 2016–2017 Eruption of Bogoslof Volcano

Bogoslof Island sits north of the Aleutian volcanic arc, about 100 km west of Unalaska/Dutch Harbor (Figure 1). It is the tip of a mostly submerged back-arc volcano that had last erupted in 1992, one of at least eight historical eruptions documented at Bogoslof (Waythomas and Cameron, 2018). The 1992 eruption lasted about 3 weeks, produced episodic ash emissions up to 8 km asl, and ended with extrusion of a lava dome (McGimsey et al., 1995). Previous historical eruptions lasted months to years, and were characterized by intermittent explosive and effusive activity (Waythomas and Cameron, 2018). Erupted compositions range from basalt through trachyandesite (Miller et al., 1998).

The most recent eruption of Bogoslof began in mid-December 2016. Between December 2016 and August 2017, activity at Bogoslof was dominated by a series of at least 70 explosive events that lasted minutes to tens of minutes, and lofted volcanic clouds as high as 14 km asl (Figure 2). During the first 2 months, AVO detected 30 such events, occurring every 1–4 days. The pace of explosions slowed in early February, and an eruptive pause from mid-March to mid-May suggested that the sequence may have ended. Activity resumed on May 17 with a series of explosive events and the first observed subaerial lava dome of the sequence. This dome was first observed on June 5 and subsequently destroyed by an explosion on June 10. In mid-August, a second lava dome formed, which was destroyed by the time of the final explosive event on August 30. This marked the apparent end of the eruption, as hot ground and water in the vent area slowly cooled, and the volcano returned to a quiescent state by the end of 2017.

For the largest part of the eruptive period, Bogoslof’s vent was submerged in shallow seawater probably less than 100 m deep, though on several occasions a subaerial edifice grew and the vent migrated above sea level. Most volcanic clouds drifted north over the Bering Sea, but three events produced ashfall on nearby communities and mariners east and south of Bogoslof (January 31, March 8, and May 17). The eruption sequence resulted in dozens of regional flight cancelations and flight diversions around the volcano1.

Materials and Methods

In the following section, we describe the classification scheme used to identify explosions, the monitoring data used in real-time (no latency) or near-real-time (latency of up to tens of minutes) to detect and characterize the events, and the protocols that were developed by AVO during the eruption with regards to internal and external communications and warning products. Other data streams, such as high-resolution satellite imagery and SO2 measurements from satellite, along with petrologic analyses of eruptive products, reveal much about the eruption but did not play a role in the short-term forecasting or detection and thus are not discussed here.

Explosive Event Onset and Classification

Following AVO routine practices during volcanic crises (e.g., Coombs et al., 2010; Bull and Buurman, 2013), explosions were assigned sequential numbers (Table 1). The onset of each event was defined using a combination of seismic and infrasound data. Whereas infrasound is a more reliable indicator that material was injected into the atmosphere (Fee and Matoza, 2013), this data stream was not always available due to wind noise and/or prevailing wind directions (typically more northward in the winter months of December through February) that can carry infrasound signals away from sensors (Figure 1). For events for which infrasound data were not available, the onset of co-eruptive tremor was used as event onset time.

Seismicity

Because of its small size and wilderness designation, Bogoslof is not monitored by a local, on-island geophysical network. In the absence of a local network, AVO used seismic sensors from Okmok (∼50 km) and Makushin (∼72 km) volcanoes on neighboring Umnak and Unalaska Islands (Figure 1) to monitor seismic activity associated with the Bogoslof eruption. Storms are common in the Aleutians, especially during the winter months, and seismic signals were often masked by wind noise. Furthermore, the relatively large distances between the active vent and the closest seismic stations meant that only the more energetic explosions were detected. The interpretation of data was also complicated by the submarine nature of the eruption. Seismograms recorded body (P and S) waves as well as energy that was transmitted acoustically through the water column before coupling back into the solid Earth (T waves; Okal, 2008), a path-dependent process that manifests differently at different stations. Finally, tectonic tremor is common in the region (Li and Ghosh, 2017) and was sometimes mistaken for co-eruptive tremor.

Explosive events were characterized by minutes to tens of minutes of co-eruptive seismic tremor on the neighboring island networks. Explosive events during the first few months of activity often exhibited precursory seismicity as well, which allowed AVO to issue warnings prior to event onset (events with negative latency for calls or written notices; Table 1). Precursory seismicity primarily consisted of repeating earthquakes, which would become more closely spaced in time over a period of hours, culminating in eruption (e.g., Figure 4A). Such events, commonly observed at volcanoes worldwide, are often considered a sign that an explosion may be imminent (e.g., Malone et al., 1983; Powell and Neuberg, 2003; Hotovec et al., 2013). Other explosive events during the Bogoslof eruption may have been preceded by similar precursory seismicity that was not detected by our distant networks. For these, the onset of co-eruptive tremor marked the first seismic indication of unrest for a particular event. Retrospective analysis of data from a campaign hydrophone, deployed in May 2017 near the submarine base of the Bogoslof cone, does indeed show that later events were preceded by seismicity too weak to be detected at the Okmok and Makushin stations.

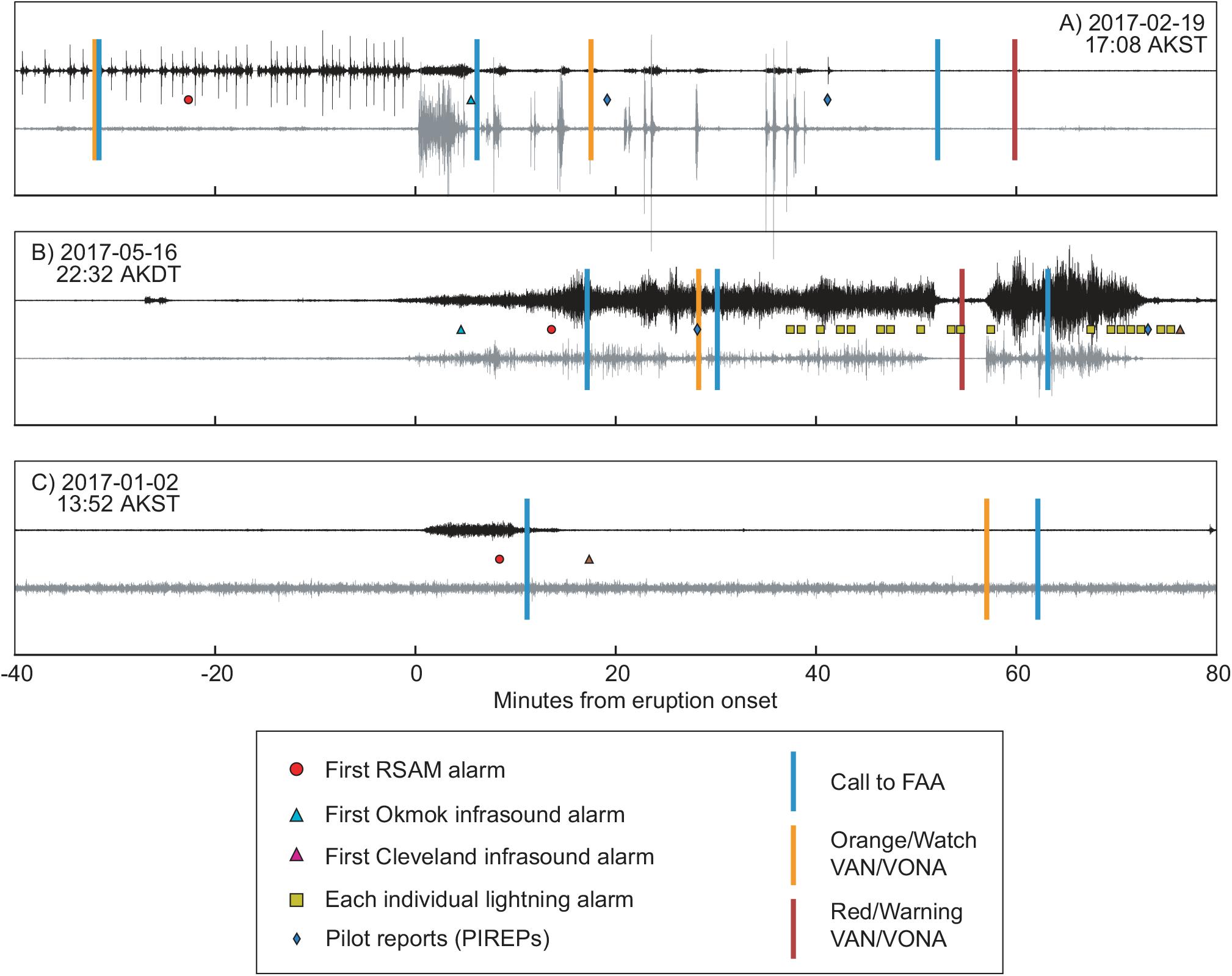

FIGURE 4. Time series of three characteristic events from the Bogoslof eruptive sequence, showing seismic data from Makushin stations MAPS (black line), infrasound from Okmok (gray line), timing of alarms and data receipt (colored symbols), and timing of warnings issued (colored vertical lines). (A) Event 36, February 19, 2017. This event is an example where precursory data allowed us to issue warnings prior to explosive event onset. (B) Event 39, May 16, 2017. This event was detected in multiple real-time data streams and was an example of a significant ash-producing event that was fairly easy to characterize. (C) Event 14 on January 2, 2017, is an example of a short explosion that was detected in seismic and infrasound data only. The initial call to FAA was fairly rapid, but lack of data resulted in difficulty characterizing the event’s magnitude and led to a delay in issuing a written warning.

Infrasound

Although intense seismic tremor is often strongly suggestive of explosive eruptive activity, the atmospheric pressure oscillations produced by violently expanding volcanic gases and recorded on low frequency acoustic (infrasound) sensors unambiguously confirm that explosive activity is occurring (Fee and Matoza, 2013). AVO operates multiple infrasound sensors or arrays along the Aleutian Arc in order to detect volcanic activity and constrain an azimuth to the source (Figure 1). Explosion infrasound was recorded at all AVO arrays over the course of the Bogoslof eruption, including stations more than 800 km from the volcano. The array closest to Bogoslof is located on Okmok volcano (59 km), and was used most frequently for monitoring because it detected a larger number of explosions with greater amplitude and lower latency (∼3 min) than the more distant arrays. As with seismic data, wind noise can mask explosion signals in infrasound data, and seasonal changes in the predominant tropospheric and stratospheric wind directions can affect infrasound propagation and detection at regional distances. These factors resulted in no single AVO array detecting all of the explosive events at Bogoslof.

Lightning

Volcanic eruption columns and drifting clouds from explosive eruptions often produce lightning (Behnke and McNutt, 2014), and lightning detection played an important role in volcano monitoring efforts during this eruption. The World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN2) provided near-real-time automated alerts within minutes of lightning strokes near Bogoslof, detecting lightning from 26 of the 62 events (∼40%). Detections typically occurred within minutes after initiation of the explosive seismic signal, and lasted minutes to tens of minutes. Global lightning networks only capture the most energetic lightning, with WWLLN detecting >50% of all strokes above 40 kA peak current, and only 10–30% of the weaker strokes (Hutchins et al., 2012). Despite this limitation, WWLLN provided important confirmation that significant explosive activity had occurred. Volcanic lightning can be generated by a variety of processes in the ash column and downwind cloud (Behnke et al., 2013; Van Eaton et al., 2016). The timing, location and intensity of the lightning is likely related to a number of factors, including the eruption rate, amount of water in the plume (liquid and ice), and atmospheric temperature gradient. In some instances, AVO also detected volcanic thunder, a previously undocumented phenomenon, in conjunction with lightning on nearby infrasound sensors (Haney et al., 2018).

Satellite Remote Sensing

Alaska Volcano Observatory uses a variety of near-real-time satellite data to monitor volcanic unrest, detect eruptive activity, characterize eruption style, and track drifting volcanic clouds. Data from the AVHRR, MODIS, and VIIRS sensors aboard polar-orbiting satellites, and from the geostationary GOES-15 and Himiwari-8 satellites were used during the Bogoslof eruption. Visible, shortwave-infrared and thermal-infrared data from these operational satellites were used. Spatial resolution ranges from 375 m for VIIRS, 1 km for AVHRR and MODIS, to more than 8 km for geostationary data. Geostationary data are generally available at 15-min intervals, with a typical data latency of about 20–45 min after collection. Polar-orbiting satellites have higher spatial resolution, but data are available less frequently. Images are typically available within 15–20 min of data collection, but due to orbital constraints there are gaps of about 4 h that occur twice daily (middle of the day and middle of the night local time).

Once an explosive event was detected in seismic, infrasound, and possibly lightning data, we used near-real-time satellite data to determine whether a significant volcanic cloud had been generated, to estimate its altitude, and to track its dispersion. Height estimates were made primarily by using the satellite-derived cloud top temperature and comparing it the atmospheric temperature profile determined from the Global Forecast System data. Bogoslof clouds rose to altitudes of 3 to ∼14 km above sea level, and were often discernible in satellite images for hours after an event.

As is common for explosive eruptions that occur in oceanic, lacustrine, or glacial settings (Mastin and Witter, 2000), Bogoslof produced volcanic clouds that show evidence for entrainment of large amounts of water from the vent region. Eye-witness and satellite observations of the clouds indicate that they were darker at the base, due to ash content, but the upper, higher parts of the cloud were frequently white and ice-rich. These distinctive characteristics affected cloud properties in satellite images, fallout and dispersion, and generation of lightning.

One result of incorporation of seawater into the eruptive column is that the widely used thermal-IR brightness temperature difference technique (Prata, 1989) is poorly suited for discriminating volcanic ash in these clouds. This is likely due to ice formation on ash particles, changing the spectral properties of the cloud. Three explosive events that showed no ash signature in satellite data produced documented ashfall on land (the others dispersed over the ocean and remote islands), supporting the hypothesis that satellite-based discrimination of volcanic ash was masked by ice formation, such as was seen in the 1994 eruption of Rabaul (Rose et al., 1995). Because the typical ash signature was mostly lacking, we identified volcanic clouds during event response primarily by their sudden onset, growth, temperature (i.e., altitude), and location over the volcano.

Pilot and Observer Reports

Pilot reports (PIREPs) or other observer reports sometimes provided details on the eruption including cloud height, dispersal patterns, and simple confirmation of activity during times when satellite views were obscured by cloud cover or no imagery was available. It was initially a PIREP on December 20 that alerted AVO to the Bogoslof eruption. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Anchorage Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) collects and disseminates all PIREPs, including those that describe volcanic activity, in a database that is accessible by AVO staff for use as notification/verification of eruptive activity. In the event of significant volcanic activity, the FAA, or the co-located NWS Center Weather Service Unit (CWSU), will call AVO directly and conversely, AVO may contact the FAA or CWSU to verify or solicit PIREPS during events. During the Bogoslof sequence, AVO reviewed 84 PIREPS during 27 of the approximately 70 explosions.

In addition to PIREPs, AVO received several mariner or citizen reports that proved useful to verifying and characterizing activity. These came via phone, email, or social media. During event 36 on February 19, AVO personnel were on Unalaska Island and observed the eruptive cloud directly.

Alarms and Alerts

Alaska Volcano Observatory is not typically staffed 24/7, which remained the case throughout the Bogoslof eruption. As a result, automated alarms based on geophysical and remote sensing data played a critical role in the eruption response. Within an hour of learning of the eruption, AVO implemented an automated alarm based on regional infrasound data to detect explosion pressure waves from Bogoslof. Seismic data, two additional infrasound arrays, and lightning data were all added to the alarm workflow over the next 48 h. Infrasound array data were processed every minute, with algorithms looking for waveform characteristics consistent with an acoustic wavefield propagating from the direction of Bogoslof during the previous 3 min. Similarly, real-time seismic amplitude measurements (RSAM; Endo and Murray, 1991) were computed for seismic data from neighboring islands every 5 min, and alerts were sent out when enough stations exceeded a designated amplitude threshold. In response to activity at Bogoslof, AVO changed how it processed near-real-time WWLLN lightning data. Previous alerts were passively received via email from WWLLN, and AVO developed a method to actively download the latest data every minute and push alerts to a response team via text message. An algorithm for detecting repeating earthquake sequences was added in late March (Tepp, 2018) to help identify precursory earthquake swarms. AVO also relied on airwave detection alarms from a more distant infrasound array 825 km away in Dillingham (Figure 1). This alert, while less useful for rapid detection, often provided valuable corroborating evidence of emissions into the atmosphere.

All AVO-based alarms were both developed and implemented internally by AVO research staff. Algorithms were initially written in MATLAB programming language and eventually converted to Python code. With a couple of exceptions, alarms are centrally managed on a dedicated alarms server, which handles scheduling, data processing and message dissemination. Alerts are delivered to the AVO’s internal chat tool (named AVO Chat; using commercial platform Mattermost) for observatory-wide access, as well as via text message to recipients included in a centrally managed distribution list, which changes based on staffing and duty rotations. Algorithms processing seismic and infrasound signals also generate images of recent data, which are included in the text messages to allow recipients to rapidly determine whether the alert represents a true or false positive.

Critical to this alarming strategy and AVO’s ability to depend on alarm functionality is a method for ensuring that the alarm system is working. Daily test messages are sent to ensure operability. AVO also uses Icinga, an open-source network monitoring application, to monitor the individual alarm modules themselves and, effectively, alarm the alarms. Upon completion (every 1 or 5 min) and regardless of detection, each alarm algorithm sends a “heartbeat” message to Icinga, which resides on a separate computer system. Using a separate messaging system, Icinga then sends text messages to system managers if a certain number of heartbeats are missed. This approach provides the robustness and assurance required for AVO to rely on geophysical alarms for event detection and has successfully alerted AVO staff of system failures on multiple occasions.

In addition to alerts developed and/or distributed by AVO, alerts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (NOAA-NESDIS/CIMSS) VOLcanic Cloud Analysis Toolkit (VOLCAT) were used by AVO throughout the eruption3. The VOLCAT system autonomously generates alerts of explosive activity worldwide using operational satellite data, identifies volcanic cloud objects, and retrieves cloud properties (height, column mass loading, and effective radii) of those objects. This system uses several different algorithms to identify volcanic cloud objects, but the most useful one during the Bogoslof eruption used anomalous cloud vertical growth rates as observed by geostationary satellites. SMS text, email, and web products were received by AVO staff within 15 min of satellite data collection, and provided a rapid estimate of volcanic cloud top altitude.

Ash Dispersion Models

The potential for ashfall on local communities or mariners depends on wind direction, eruption intensity, cloud height, and the mass of ash that is produced during each explosive event. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) provides forecasts of expected ash dispersion (ash clouds) and deposition (ashfall) from volcanic eruptions using the numerical atmospheric transport model Ash3D (Schwaiger et al., 2012). AVO uses Ash3D model outputs to predict ashfall and ash cloud information based on either hypothetical or actual eruption information (see below). The NWS Anchorage Forecast Office then issues ashfall statements, advisories, and warnings for the public and marine communities.

The 2016–2017 Bogoslof eruption was the first for which Ash3D was used commonly in response mode. AVO runs hypothetical simulations twice per day for each of the volcanoes at elevated color code. These include separate simulations for the anticipated proximal fallout as well as a regional forecast of the drifting volcanic cloud. Results from these hypothetical forecasts are posted to the AVO public website along with output from similar models (puff and hysplit). These are clearly labeled as ‘hypothetical’ and reflect the style of eruption that was observed in the past at a given volcano in terms of plume height and eruption duration.

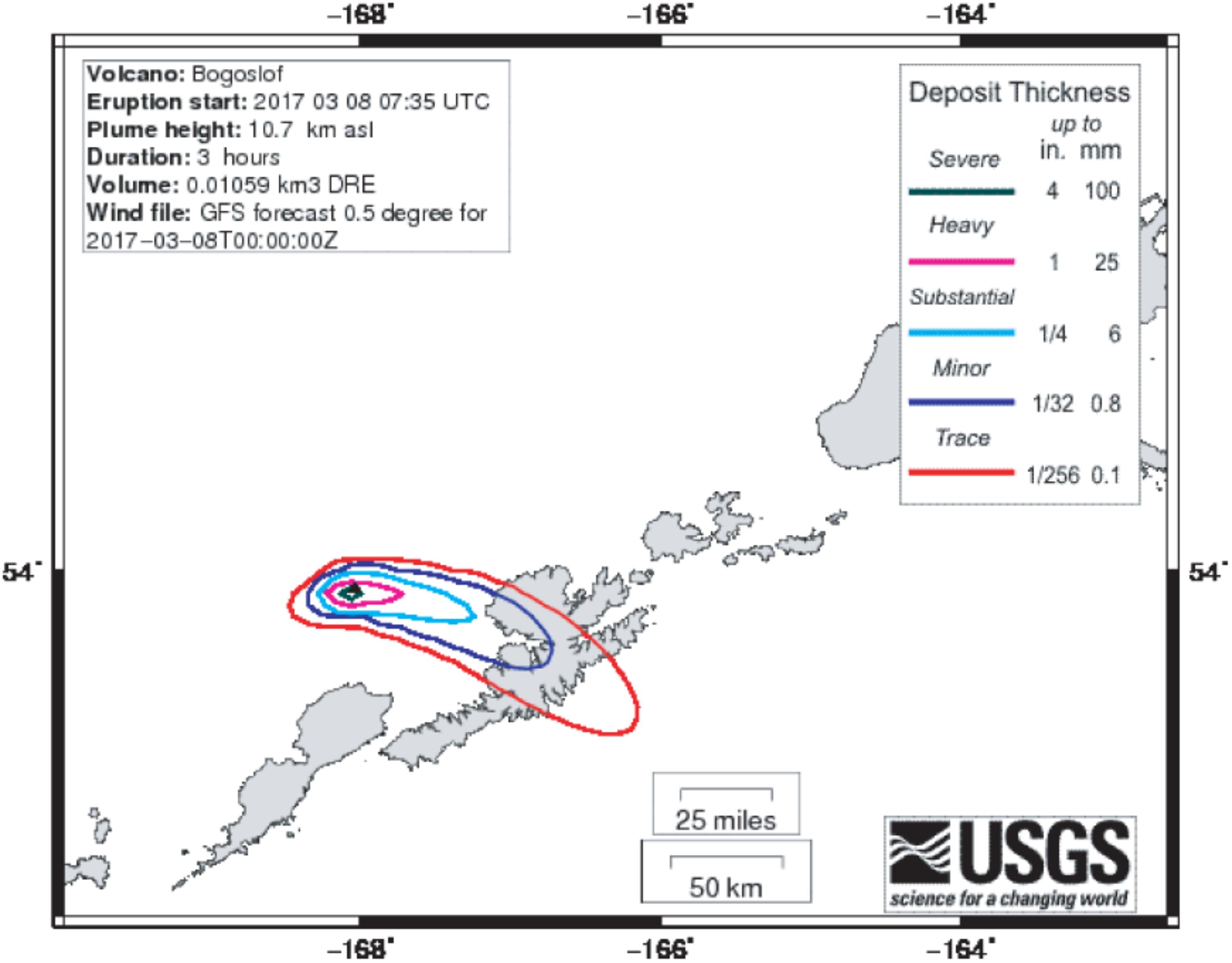

During the Bogoslof eruption, when an explosive event was confirmed, we initiated an event-specific run with the event start time, duration, and cloud height. The satellite-derived cloud altitude was used to initialize the Ash3D model to forecast ash fallout on nearby communities; these forecasts were presented on simple maps (Figure 5). These event-specific simulations were initially run with only a known start time and estimated plume height and duration, but then run iteratively as new information became available. The most recent model output reflecting the best estimate of volcanic cloud and fallout hazards was posted on the AVO public website with a prominent note indicating that these output results correspond to an actual eruption. Output results from the actual events remained on the public website for at least 12 h before reverting to the hypothetical simulations.

FIGURE 5. Map with contours of expected ashfall thickness for the March 7, 2017 event (#37) that had ash fallout near Makushin on Unalaska Island. Contours derived from the numerical atmospheric transport model Ash3D (Schwaiger et al., 2012). Please refer to Figure 1 for place names.

Intra Observatory Roles and Communication

Alaska Volcano Observatory has established protocols for duty roles during routine operations and during eruptions. These were modified to adapt to the Bogoslof eruption in several ways. Generally, duty staff consist of the Scientist-in-Charge, Duty Scientist, Duty Remote Sensor, and Duty Seismologist. In addition, on-call staff are responsible for maintaining web servers and data acquisition systems. Duty roles typically rotate on a weekly basis through a group of 8–10 staff members. Duty science staff perform routine data checks and, when necessary, respond to activity.

During the Bogoslof eruption, it was necessary to develop a second, sometimes overlapping group to respond specifically to Bogoslof events. Called the Primary Response Team, this group consisted of a Response Geophysicist, who received alarms and analyzed infrasound and seismic data; a Response Remote Sensor, who received alarms, analyzed satellite data, and acted as primary liaison with the Anchorage VAAC; an Ash3D specialist, who ran event-specific ash dispersion models and, when necessary, was the primary liaison with the NWS Forecast office responsible for ashfall forecasts; and the Duty Scientist, who integrated all data streams and wrote and distributed formal warning products (typically, Volcanic Activity Notices, see below).

This team was assigned weekly, and team members were on call for that week. Much of the activity took place outside of normal working hours, so communication amongst the team initially occurred via phone and often text messaging. During the eruption, AVO implemented use of an internal chat tool, AVO Chat, accessible on computer or mobile device, which allowed the team to communicate easily while also allowing other observatory staff to remain aware by following the discussion. More formal communication took place over AVO’s internal log system, where staff document event summaries, and post other more in-depth analyses.

External Communication

Internal communication is necessary to bring interdisciplinary data and expertise together to make informed assessments of volcanic activity and hazards, but this information must then be communicated quickly and clearly to interagency partners and the public. A main focus of this study is determining how effectively AVO was able to do this during the Bogoslof eruption. The protocols for external communication during ash-producing eruptions in Alaska is formalized in the Interagency Operating Plan for Volcanic Ash episodes and described in detail elsewhere (Neal et al., 2010). Below, we briefly summarize the USGS Alert Levels and Color Codes, formal Information Products, and call-down procedures. We then describe how formal policy was modified during the Bogoslof eruption to accommodate the high pace of activity and paucity of monitoring data.

Official Warning Products

United States Volcano Observatories utilize a dual system of alerts: an Aviation Color Code to address aviation hazards (Guffanti and Miller, 2013), and a Volcano Alert Level to indicate the overall hazard at a volcano (Gardner and Guffanti, 2006). Changing Aviation Color Codes (GREEN, YELLOW, ORANGE, and RED) and Volcano Alert Levels (NORMAL, ADVISORY, WATCH, and WARNING) indicate increasing severity and likelihood of potential impacts. Unmonitored volcanoes, like Bogoslof, are designated as Unassigned if they are at apparent background levels of activity (not GREEN); when they exhibit unrest, however, elevated color codes and alert levels may be assigned as activity warrants. During the eruption of Bogoslof and other remote volcanoes, the Aviation Color Code and Volcano Alert Levels are almost always coupled (for example, ADVISORY/YELLOW). In this paper, we refer only to the Aviation Color Code for brevity.

In conjunction with the alert systems described above, AVO and other United States observatories issue a number of formal warning products to notify the public and other partner agencies of volcano hazards or other important information. All messages are posted on the AVO website, pushed out via email to key partners, and also freely available to anyone via email by subscribing to the Volcano Notification System (VNS)4. All formal notifications are issued via the web-based USGS HAzard Notification System (HANS). HANS facilitates rapid dissemination of information by providing database- and web-form-driven formatted notifications preset with headers and footers, volcano information (ID, location, elevation, existing color codes), issuance time, and other guides (e.g., summary of activity, cloud height, recent observations) allowing duty staff to quickly create and release notifications.

Event-specific messages include the Volcanic Activity Notice (VAN), which we issue to announce alert-level changes or significant volcanic activity. Additional VANs are released as needed, depending on changes in volcanic activity, alert levels, or hazards. VANs also are used to declare the ‘all clear’ when an eruption is waning or has ceased. The Volcano Observatory Notice for Aviation (VONA) is a derivative product of the VAN and contains information emphasizing ash emission hazards in a format specifically intended for aviation users (pilots, dispatchers, air-traffic managers, meteorologists).

Alaska Volcano Observatory typically issues a Current Status Report to provide an update about volcanic behavior or monitoring activities during ongoing events of unrest or eruption. A status report may be issued multiple times in a single day. Finally, AVO issues Information Statements that announce topical information such as new monitored volcanoes, significant operational or monitoring capacity changes, ash resuspension, explanation of non-volcanic events at a volcano, and expanded descriptions of volcanic unrest and likely outcomes.

During the Bogoslof eruption, AVO developed a protocol for information products to be released for each explosion to speed up decision making during an event and release information as quickly as possible. As appropriate, we would release some or all of the following categories of VAN:

(1) Imminent: when precursory unrest was detected, a VAN would describe this activity and be released prior to the onset of the event. This VAN would not involve a color-code change.

(2) Initial: As soon as possible after event onset, a VAN would indicate that an explosive event had occurred. This VAN often did not have information about cloud height, cloud movement, or event duration. Because this VAN was often released prior to a full understanding of the magnitude of the event, sometimes this VAN would not involve a color code change.

(3) Follow-up: This VAN would provide additional information that was not available at the time of the Initial VAN. For example, event duration, cloud height, direction of cloud movement, and any information about possible ashfall on populated areas. For larger events, this VAN could involve a color code change from ORANGE to RED.

(4) Following this series of VANs, AVO would release a status report within 1 to several hours of the event to summarize the event, its impacts, and state future actions on the part of AVO.

(5) Within 24 h of the explosive event, AVO would typically lower the color code from RED to ORANGE (done via another VAN), if the event had prompted the color code to be raised to RED. The Aviation color code remained at ORANGE for most of the eruptive sequence (Figure 2).

To assess the timeliness of these formal notification products, we show the time of the first such VAN, as determined by the automated time stamp provided in the HANS system, with respect to each individual explosive event (Table 1). Depending on the presence or absence of precursory signals, this first VAN would either be of the “imminent” or “initial” variety, as described above.

Call Downs

Upon determination of a significant change in the status of a volcano, whether increased likelihood of eruption, detection of eruption, change in eruption status, end of eruption, or color code change, AVO initiates a formal call down. First on the call-down list is the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Air Traffic Control Facility, followed by NWS offices, and other state and federal agencies. Call-down messages are brief and include the following general information: name of caller; volcano name and location; nature of activity and source of information (seismicity, PIREP, etc.); Aviation Color Code and Volcano Alert Level status or change in status; start and stop time of event or activity (if known); height of eruption cloud, how determined, and direction of cloud motion (if known). When significant unrest or activity is detected, AVO will make “heads up” calls to the FAA and NWS offices prior to the official call down (e.g., Figure 4).

Duty personnel sometimes record call down times on a written sheet, and often record the time that the entire call down was completed in AVO’s internal log system. Because the entire call down can take several minutes to complete, we wanted to investigate the time that the initial call to the FAA was conducted for each event. Using cell phone records of AVO duty personnel, we have determined the timing of the first call to the FAA either immediately prior to, or immediately after, each explosive event (Table 1). The time between the event onset and this call is defined as the call-down latency and is separate from the latency of the written information product described above.

Integration With Other Agencies

The responsibility of providing notifications about volcanic ash is distributed among several agencies in Alaska. AVO and its partners have created an Interagency Operating Plan—an overview of an integrated, multi-agency response to the threat of volcanic ash in Alaska. A description of the roles of all partners is beyond the scope of this paper, but can be found in Neal et al. (2010), and the current plan itself is available online5. Below, we briefly summarize those partners who, in conjunction with AVO, issue formal warning products about volcanic ash and hazards.

The NWS Alaska Aviation Weather Unit (AAWU) also serves as the Anchorage Volcanic Ash Advisory Center (VAAC). The AAWU/VAAC is responsible for issuing Volcanic Ash Advisories (VAAs), which provide information on the distribution and forecast movement of ash, and Significant Meteorological Information (SIGMETs), which serve as the primary warning product to the aviation community for volcanic ash. AVO works closely with the AAWU/VAAC before and during ash-producing events to coordinate on timing and distribution of explosive events, interpretation of ash clouds in satellite imagery, sharing of lightning data and the extent and timing of NWS formal products. The FAA may institute Temporary Flight Restrictions (TFRs), in consultation with AVO.

The NWS Weather Forecast Office (WFO) in Anchorage is responsible for issuing all warnings of ashfall for the public and marine communities in Alaska. If ashfall is expected based on model output, AVO coordinates with the Anchorage WFO on the details of where, when and how much ashfall is expected and NWS warning products are issued accordingly. The United States Coast Guard may issue notices to Mariners about hazards in the marine environment.

Results

Observatory Response to the Eruption

Below we present a brief chronology of the eruption and describe how the operational response evolved with time.

Precursory Phase and Initial, Undetected Explosive Events (September Through Mid-December, 2016)

The first five explosive events, which occurred on December 12, 14, 16, and 19, 2016 (Figure 2), were only detected retrospectively using lightning, infrasound, satellite, and/or seismic data. These events, 1–5, were missed by AVO’s routine data checks and ongoing alarms and thus AVO did not issue any notifications at the time of the events, not did any other partner agency. Seismic signals from the time of Events 4 and 5 on December 16 and 19 were noted during routine seismic checks, as being detected at Akutan, Makushin, and Okmok, but were suspected to be either tectonic tremor or low-level activity at Okmok. Retrospective analysis of the earthquake catalog, combined with match filtering, revealed that precursory volcano-tectonic earthquakes had been occurring since at least September 2016 (Stephen Holtkamp, written communication, 2016).

Rapid Explosive Events, Common Precursors (December 20–March 13)

Event 6 on December 20, 2016, was the first event of which AVO was aware. We were notified by a call from the FAA/CWSU calling to inform us of a PIREP of an ash eruption coming up and out of the Bering Sea. After confirming that this was from Bogoslof, AVO raised the Aviation Color Code from Unassigned to RED. A second, similar event (7) occurred about 24 h later.

An RSAM alarm that focused on Bogoslof was implemented shortly after Event 7. During this first phase of the eruption, the pace of explosions was exceptionally high, with, on average, one event every 58 h (Figure 2). Through late January there were about 29 short-lived events that put ash clouds up to heights of 6–11 km asl. On the night of January 30–31, a longer, ash-rich event resulted in sufficient tephra accumulation to produce a subaerial edifice that raised the vent above sea level for the first time. On January 31, AVO issued an Information Statement that provided an overview of the eruption to that time, status of the monitoring capabilities, and prognosis for future activity (Supplementary File S1).

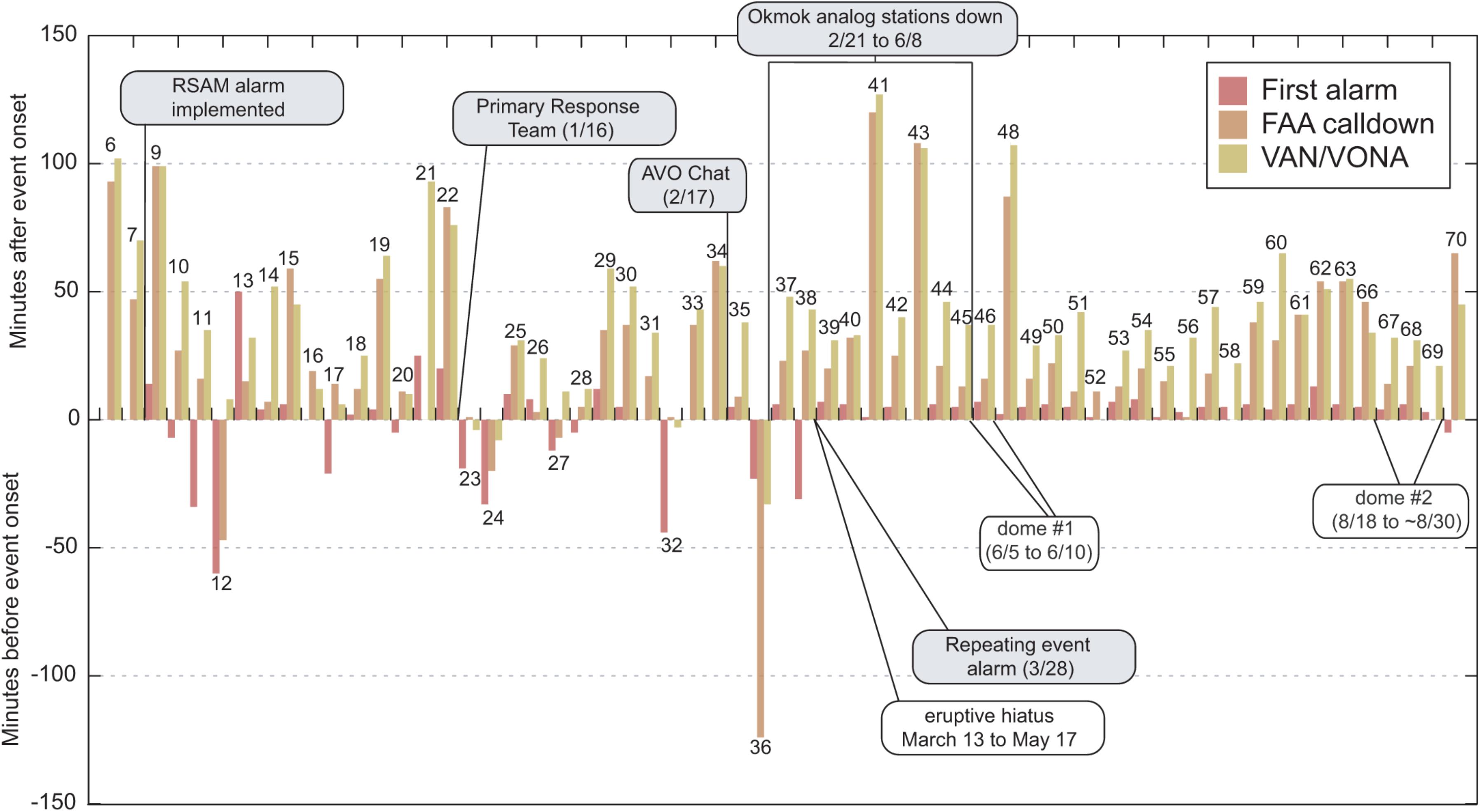

Throughout the period from December through March, 12 events had precursory seismic activity that was detected by the RSAM alarm, as indicated by negative alarm latency (Table 1 and Figure 6). Event 36 on February 19 is an example of such an event (Figure 4A). A classic sequence of coalescing earthquakes served as a prelude to a series of energetic eruptive signals that began at 17:08 and lasted over half an hour. This activity was first recognized during a scheduled duty check at about 13:00. The sequence then kept up with a relatively low rate until about 15:55 when the rate suddenly increased to about 30 earthquakes per hour. The rate then progressively increased over the next hour until the quakes had almost merged to tremor by 17:00. The first RSAM alarm triggered on the quakes at 16:44 pm. Earthquakes ceased at 17:07 and after a 1-min break transitioned to tremor. The eruptive signals consisted of about nine blasts that were clearly captured on multiple infrasound arrays. The infrasound on the Okmok array triggered the airwave alarm several times during the eruption. Because of the relatively long run-up, AVO called the FAA 124 min prior to event onset and issued an “imminent” VAN 33 min prior to the event.

FIGURE 6. Bar plot showing latency, in minutes, between explosive event onset and first alarm received, call to FAA, and release of first Volcanic Activity Notice. Numbers indicate numbered events, in chronological order. Gray labels indicate operational milestones, and white labels describe significant events in the eruptive sequence. Events for which neither call-downs nor written notifications were issued are not shown (for complete list of events, see Table 1).

Hiatus in Explosive Activity (March 13–May 16)

Following event 38 on March 13, there was a 9-week hiatus in explosive activity at Bogoslof. The Aviation Color Code remained at ORANGE until April 5, at which time AVO lowered it to YELLOW. The only detected activity observed during the hiatus was a swarm of volcano-tectonic earthquakes on April 15, which prompted AVO to raise the color code to ORANGE. The swarm lasted for several hours, comprised 118 detected earthquakes with M between ∼0.8 and 2.2, and is interpreted to reflect magmatic intrusion in the mid to upper crust because of the earthquakes’ weak T phases (Wech et al., 2018). Following this swarm, which lasted for several hours, the color code was once again lowered to YELLOW on April 19.

Renewed Explosive Activity and Dome Building (May 16–August 30)

Bogoslof erupted again without precursors on May 16 (event 39; Figure 4B). From May 16 through August 30, AVO detected 32 explosive events at the volcano. Unlike during December–March, none of the explosions in the later phase was preceded by detectable seismic precursors, meaning that AVO was always responding to the onset of explosions rather than issuing warnings of impending activity. An exception was event 48 on June 10, which did not have seismic precursors but did have a brief initial infrasound pulse about an hour before confirmed explosive activity (Table 1).

On June 7, satellite imagery confirmed the presence of a subaerial lava dome at the volcano. It was located in the northern portion of the vent lagoon, had breached sea level, and was about 110 m across. The lava dome was short-lived, as it was completely destroyed during a 2 h and 10-min pulsatory event on June 10 (event 48). A second lava dome was observed on August 18 in the enclosed crater. The exact timing of the destruction of this dome is unclear due to a lack of satellite imagery, although we can infer that it occurred during the final detected event of the entire sequence on August 30 (event 70). Following nearly a month without activity, AVO lowered the aviation color code to YELLOW and Alert Level to ADVISORY on September 27, and finally, to UNASSIGNED on December 2, 2017.

During the 2016–2017 eruption of Bogoslof, AVO raised the aviation color code to RED 32 times, and was at ORANGE for most of the sequence (Figure 2). For eruptive periods of hours or days that included multiple explosions or prolonged seismic or infrasound signals, AVO remained at RED throughout such sequences before downgrading to ORANGE.

Alarm Timeliness and Efficacy

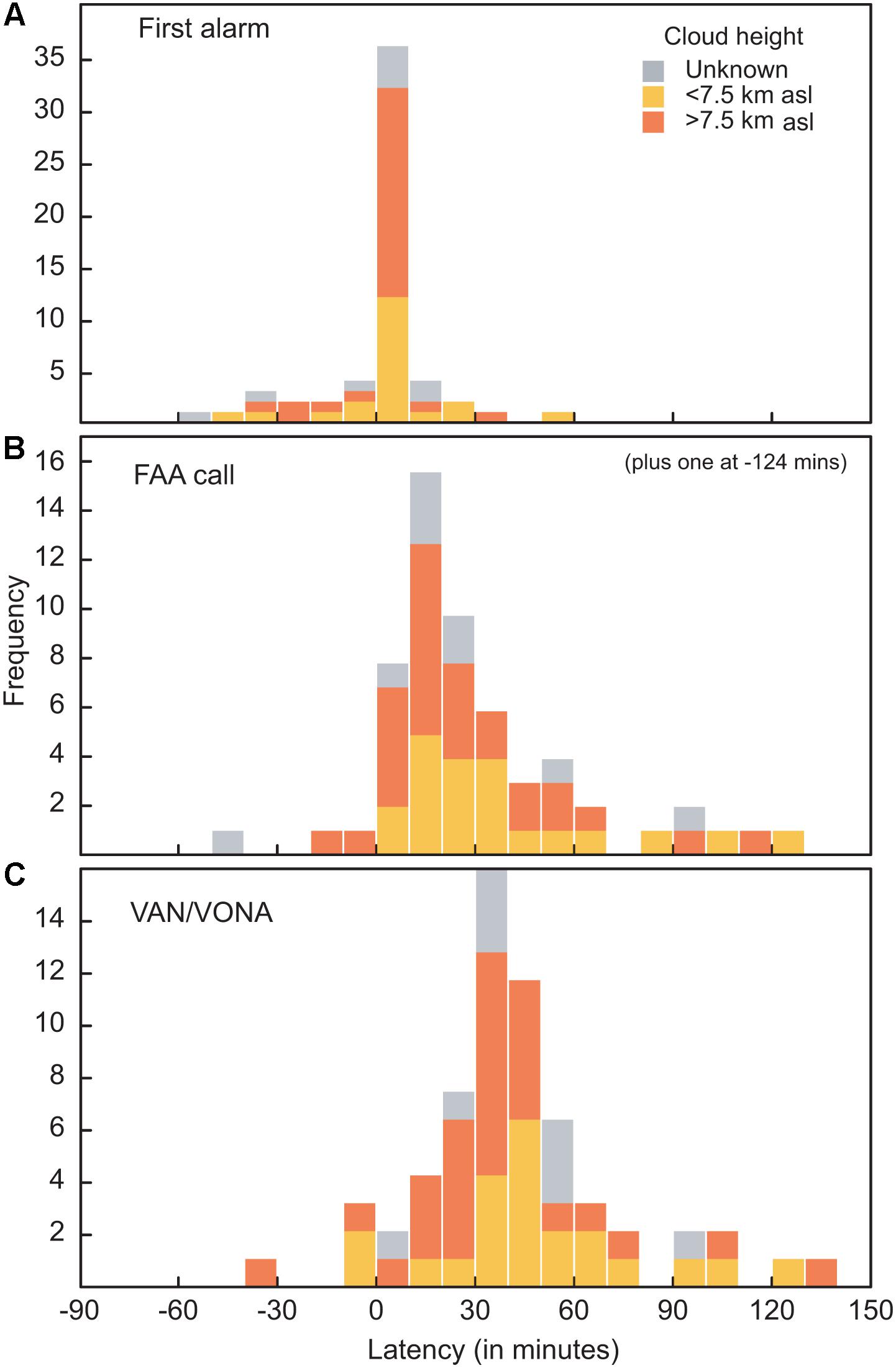

Once all Bogoslof-specific alarms were implemented (after event 7), all but four subsequent events were caught using one or more alarms (Table 1; see exceptions below). RSAM was the first alarm 60% of the time, and infrasound at Okmok was the first alarm 35% of the time. The median latency between event onset and receipt of alarm by observatory staff was 5 min; the mean time was 0 min (Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7. Histograms of latency of (A) first alarm, (B), call to FAA, and (C) VAN issued, for explosive events during the 2016–2017 eruption of Bogoslof.

Three events were detected initially by lightning instead of RSAM or infrasound: 9, 25, and 27 (Table 1), and event 25 was the only event that was detected in real time using only lightning. During this event, wind noise masked any infrasound signal, and telemetry dropouts affected the seismic data.

Events 34, 43, 47, and 64 were the only confirmed events that did not trigger any alarms after alarms were implemented. Event 34 produced a seismic signal and an ash cloud that reached approximately 7.5 km ASL. Two of six seismic stations that made up the alarm at that time exceeded the alarm threshold, but the alarm needed three stations to trigger. Following this event, alarm thresholds were adjusted. Because the event took place during office hours, staff saw the seismic signal and issued a VAN 48 min after the event occurred (Table 1 and Figure 6). Event 43 was a short-lived, low amplitude event seen seismically but not in infrasound, satellite, or lightning. An observer aboard the R/V Tiglax noted a white plume rising only several thousand feet above sea level. The seismic amplitude for this event was too low to trigger the RSAM alarm. A VAN was issued 106 min after the event. Events 47 and 64 were both very short-lived, seen only in infrasound data during retrospective analysis, and no notifications were issued for either.

Of the 58 alarmed events, 12 had RSAM alarms detect precursory seismicity (Table 1). These all occurred in the first half of the eruptive sequence (December through March). Event 48 on June 10 was preceded by an infrasound alarm about an hour before the main explosion.

Timeliness of Partner Calls

The time between event onset and the call to FAA (the first partner on the formal call-down list) ranged from 124 min before an event (for those for which precursory seismic signals were detected; shown as negative values in Table 1 and Figure 7) to 120 min after event onset (for events which were detected only). Of the 60 events for which we issued notifications, we were able to make the first FAA call prior to event onset four times, and for six additional events the recorded call time was within 5 min of the start of the event.

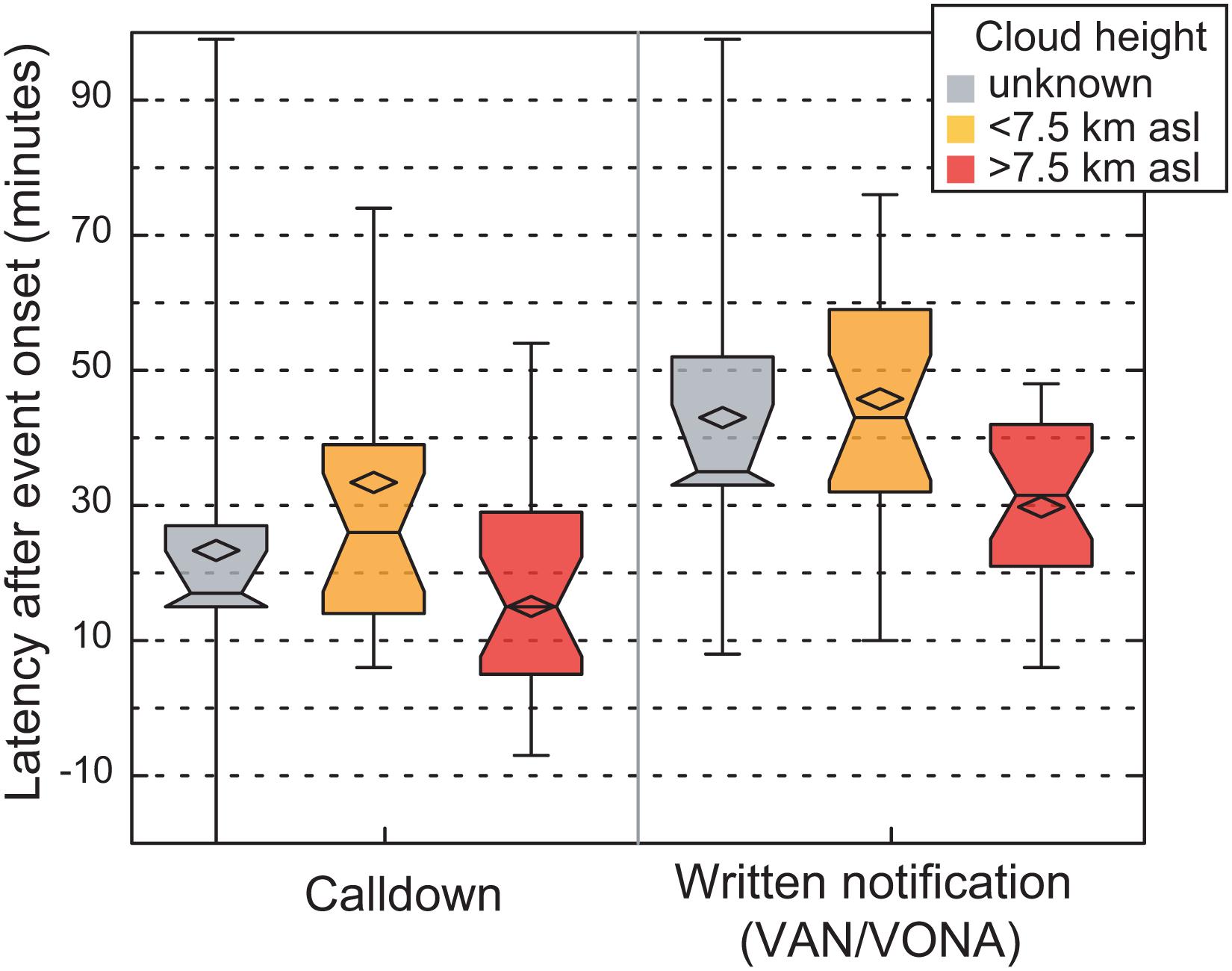

The median and mean latency between event onset and call time for all events were 20 and 27 min, and did not trend appreciably through the eruptive sequence (Figure 6). For larger events that produced plumes >7.5 km asl and were alarmed, median and mean call times were both 15 min; for smaller alarmed events with clouds below 7.5 km asl, median and mean times were longer: 26 and 33 min (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Box-whisker plots showing times of call and VAN/VONA with respect to alarmed explosive event onset (latency). In each case, notched center shows median, bottom and top of box show 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers show 10th and 90th percentiles. Diamonds show means. Outliers are not shown; for full distribution, see Figure 7.

Timeliness of Formal Warning Products

The time between event onset and the first VAN/VONA issued for that event ranged from 33 min before event (those for which precursory seismic signals were detected; shown as negative values in Table 1 and Figures 6, 7) to 127 min after event onset (for events which were detected only). Of the 60 events for which notices were issued, we were able to issue the first notice prior to event onset 4 times (7%).

The median and mean times between event onset and issuance of the first VAN/VONA for each event were 37 and 41 min, respectively. Looking only at events for which alarms were in place, these values drop to 35 and 37 min, respectively. And for events that generated plumes greater than 7.5 km asl, and had alarms in place, the median and mean times to VAN issuance were 32 and 30 min, respectively (Figure 8).

Looking only at events for which no precursory activity was observed, the VAN latency averaged 45 min. This time reflects reaction time when we are in “detect only” mode—typical for most Bogoslof events in this sequence as well eruptions at other unmonitored volcanoes in Alaska (notably Cleveland—see De Angelis et al., 2012). This time reflects the time between event onset and initial alarm, a scientist evaluating the validity of the alarm(s), contacting one or more other duty staff, assessing other data streams, drafting the notice in HANS, and releasing it (e.g., Figure 4C). VANs contain event start time, duration (if not ongoing), data streams used to confirm event, and any information about cloud height and movement. Because all seismic data used during this eruption were distant, increased uncertainty about the precise nature of individual signals led to the desire to use multiple data streams.

As the eruption progressed, AVO scientists became more adept at distinguishing co-eruptive tremor signals from other types of seismicity and became more confident in interpreting these distant signals. This would hopefully lead to decreased latency between event onset and VAN. As seen in Figure 6, however, some events later in the eruptive sequence still had latencies of over 30 min. This is due, in part, to the changing character of the explosive events themselves. Smaller events later in the sequence, such as 63 and 70, with more equivocal signals and fewer data streams were harder to interpret, leading to greater uncertainty and longer time between event onset and notice release.

Discussion

The Bogoslof eruption’s high number of explosive events allowed us develop new operational tools and protocols, and to put these developments into practice. The large number of events also allowed us to retrospectively analyze the factors that affect warnings. For more short-lived sequences, it is not possible to investigate these factors. Below we discuss the factors that impact warning timeliness, the particular hazards posed by Bogoslof and other remote volcanoes and how to cater warnings to those hazards, and finally, implications for future monitoring and forecasting in Alaska and other remote regions.

Factors That Impact Warning Timeliness

The primary factor that influenced our ability to provide timely warnings was, of course, whether precursory seismic activity was detected by the remote networks. For those events that were preceded by seismic precursors, we issued warnings and calls prior to event onset (Figures 4A, 6). That this was possible at all at an unmonitored volcano was due to the relative proximity of the Makushin and Okmok networks, and the significant seismicity of the eruptive sequence, at least for the first few weeks.

Power and Cameron (2018) investigated the time between explosive event onset and initial call down for large ash-producing events at seismically monitored volcanoes in Alaska since 1989. They find that in these instances, reaction time (call time) ranged from <1 to 86 min. Shorter times are for intra-sequence events at Redoubt, Spurr, and Augustine; longer times are for explosions without geophysical precursors.

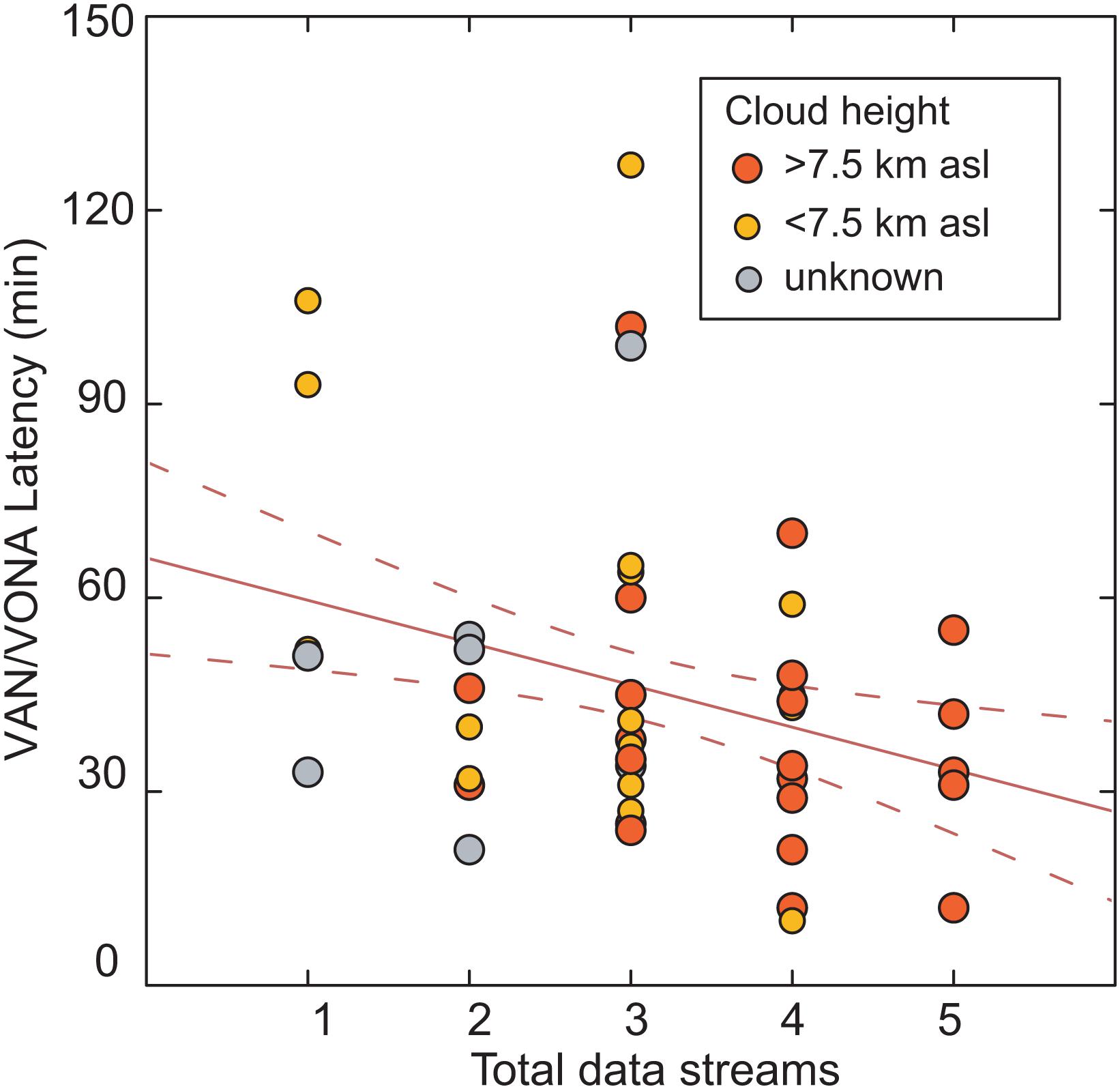

For the Bogoslof events with no detectable precursors and for which only detection was possible, notifications were typically issued faster for larger explosions, because there was less uncertainty associated with these events (Figures 7, 8). In general, larger events “lit up” more of the primary real-time and near-real-time data streams that we used to monitor Bogoslof—seismic, infrasound, lightning, satellite, and observer reports. Our latency improved (got smaller) with an increasing number of available data streams (Figures 4B,C, 9). Whereas uncertainty has been discussed as playing a role in hindering accurate forecasts of the onset of impending activity (e.g., Marzocchi et al., 2012; Doyle et al., 2014), we also show that uncertainty can impact the ability to confirm and characterize activity after it has started. In general, decreasing the uncertainty in the character of the event gave us more confidence in our forecasts and allowed us to issue them sooner. For smaller events with fewer corroborating data, it took longer to (a) confirm an event and (b) determine its magnitude (Figure 4C).

FIGURE 9. Scatter plot showing latency of VAN/VONA, in minutes, versus number of monitoring data streams (seismicity, infrasound, satellite remote sensing, lightning, and/or observer reports) available for each explosive event. This plot excludes explosions for which precursory seismicity was detected, which highlights that when trying to characterize detected events, more data streams decrease uncertainty and lead to faster notifications.

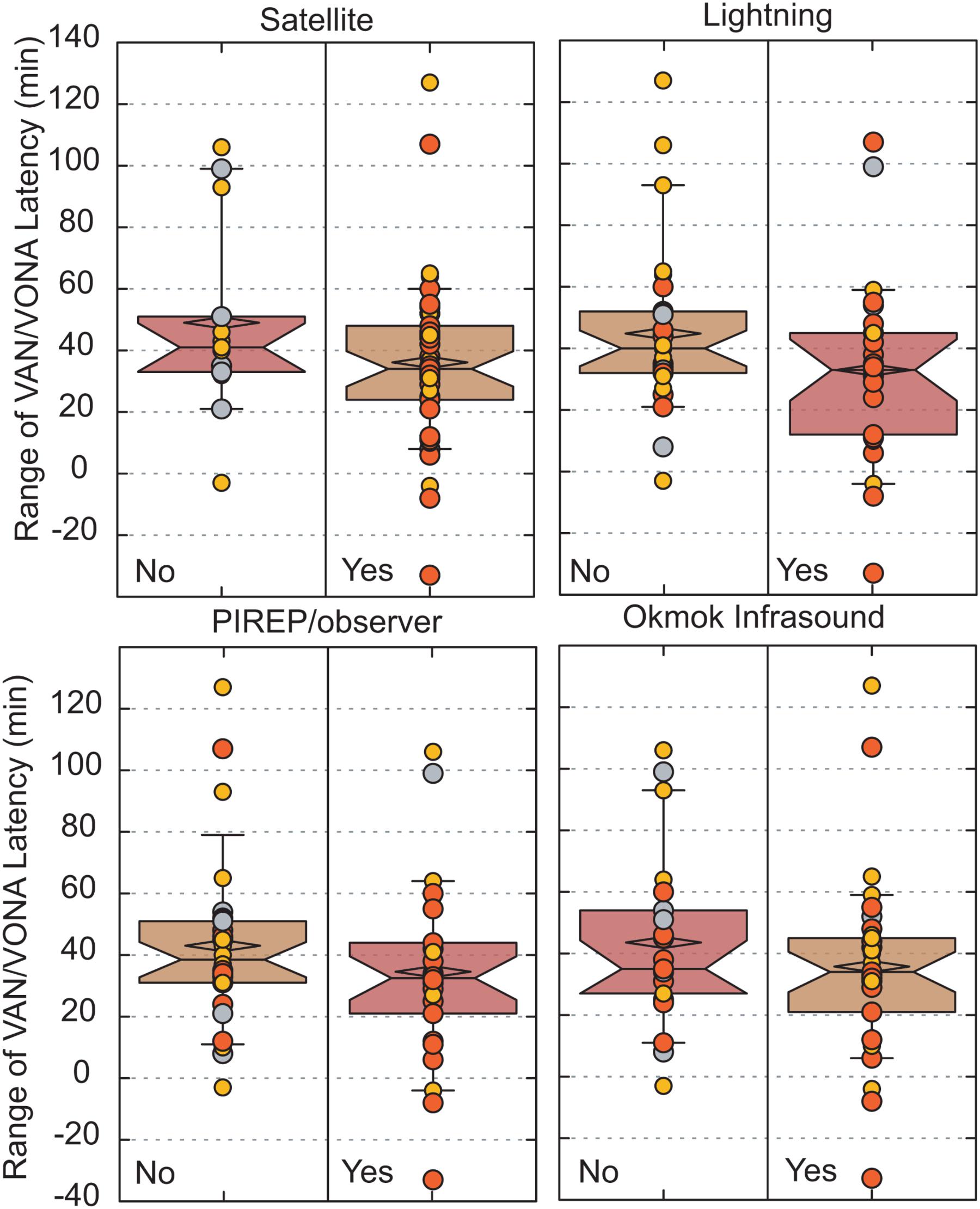

In addition to the overall number of available data streams, some types of data were more impactful in issuing timely warnings. Figure 10 shows the distribution of VAN/VONA latency with and without four main data streams (this analysis was not done for seismic data, which was available for all but two of the events). The biggest decreases in warning time come when lightning and satellite data were available, which caused average decreases in notification time of 13 and 11 min, respectively. Because lightning is otherwise so rare in the area around Bogoslof, its presence was excellent confirmation of activity, greatly decreasing uncertainty. And because ash-cloud height, normally related to mass eruption rate, was perhaps the most important factor in evaluating the hazard posed by each event, having satellite confirmation of the event combined with estimates of cloud height also allowed us to issue notifications more quickly.

FIGURE 10. Box-whisker plots showing effects of the presence or absence of individual data streams on latency of notifications for those events 6–70 for which notifications were issued. In each case, notched center shows median, bottom and top of box show 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers show 10th and 90th percentiles. Diamonds show means.

It is also important to point out that the timeliness we are evaluating here has a distinct human factor—a number of different scientists, at various times of day or night, were responsible for releasing notices and making calls to partners. There will be natural variability in the speed with which different scientists can perform these duties. Despite implementing standardized protocols, the poor quality of the data (due to eruption of an unmonitored volcano) and decision to not have full-time staffing but to instead rely on alarms, undoubtedly led to slightly increased and variable latencies.

Warnings to Match the Hazards

Bogoslof is a remote volcano and the primary hazard is posed to aviation by ash clouds generated during explosive eruptions. Unlike volcanoes that are near large populations and infrastructure, where warnings related to volcano hazards may initiate complex and costly evacuations and public concern, warnings about activity at Bogoslof led to fairly straightforward actions to ensure that aircraft would divert around any ash-bearing cloud. In this case, the use of straightforward color codes and warnings was effective for managing the crisis (Papale, 2017).

In addition to the specific-event-driven warnings that were issued by AVO and the Anchorage VAAC with respect to airborne ash, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) imposed a TFR around Bogoslof Island from January 9 to October 9, 2017, with a radius of 10 nautical miles that reached from sea level to 12.2 km asl.

Additionally, Marine Weather Statements (for ashfall on a marine environment) were issued by the Anchorage WFO and broadcast via United States Coast Guard (USCG) for most of the 64 explosive events due to the busy marine shipping lanes and proximity to Dutch Harbors, the nation’s busiest marine fishing port. Describing the hazards local to Bogoslof during frequent explosions, AVO worked with the USCG to issue a Local Notice to Mariners (LNM) for a six nautical mile radius of the island beginning January 31, 2017, for the duration of the eruption; LNM’s are issued weekly on the Coast Guard’s website. Based on wind direction and intensity of the eruption, ashfall was only expected to make landfall on about six of the 64 explosive events and advisories for communities were issued for each. Depending on wind speed, dispersion models suggest that trace ashfall reached as far as ∼200 km from the volcano, and typical onset of ashfall in the nearby community of Dutch Harbor was anywhere from ∼2 to 5 h after the beginning of an explosion.

Toward Rapid Detection of Eruptions at Remote Volcanoes

Although our multidisciplinary approach to monitoring yielded a response that resulted in zero encounters between aircraft and ash clouds, Bogoslof also highlighted the challenges in volcano science and monitoring in Alaska and elsewhere, especially where ground-based monitoring is absent. The ideal in eruption forecasting is to be able to warn of future volcanic activity, and for much of the sequence we were limited to timely detection.

The USGS uses a threat assessment framework to define threat levels at each United States volcano based on exposure and hazard factors and to prioritize future efforts to expand the monitoring network to include more in situ monitoring (Ewert, 2007). Because of Bogoslof’s remote location, it falls in the moderate-threat category, and therefore, will not be a priority for in situ monitoring in the short term.

The Bogoslof eruption showed, however, that even without in situ monitoring, new tools can allow us to rapidly detect the onset of explosive activity, characterize the resulting cloud, and forecast hazards associated with the eruption. In the past 10 years, new installation and analysis tools have expanded the use of infrasound to monitor activity in Alaska and elsewhere (De Angelis et al., 2012; Fee et al., 2013). While infrasound has primarily been used as a detection and not a forecasting tool, detection may be sufficient for remote volcanoes where the main hazard is posed by airborne ash clouds that may impact aviation or deposit ash on distant communities. In addition to infrasound, Bogoslof clearly identified the benefits of lightning as a rapid detection tool. Integrated alarm systems that look at these and other data streams in concert will allow observatories to decrease false positives and rapidly identify activity at unexpected volcanoes.

Finally, as part of the National Volcano Early Warning System, the USGS has proposed a 24/7 Volcano Watch Office that would take full advantage of real-time monitoring networks and improve delivery of hazard information to key users (Ewert et al., 2006; United States Geological Survey [USGS], 2007). Such a watch office might have caught the initial explosive events from Bogoslof in December 2016, especially if integrated alarms are developed further. A watch office would also likely decrease latencies in ongoing eruptions such as Bogoslof since it would eliminate the “activation energy” that is present when responding to alarms. Scientists who staff such a watch office would need to monitor multiple, interdisciplinary data streams and be prepared to rapidly take action in the event of explosive activity.

Conclusion

For eruptions of remote volcanoes whose explosive ash clouds pose hazards to aviation and downwind communities, short-term forecasting and detection using remote tools can provide the necessary information to mitigate risks. During the 2016–2017 eruption of Bogoslof, which lacks an in situ monitoring network, this type of response was accomplished using a multi-disciplinary approach that included seismic, infrasound, lightning, and remote sensing data combined with observer reports, automated alarms, observatory protocols and communication tools, and ash dispersion modeling. Information about the onset time and duration of explosive events, and the height and movement of resulting volcanic clouds, was conveyed using telephone calls to partner agencies as well as written warnings.

Of the 60 explosive events for which notifications were issued, aviation authorities were notified by phone an average of 22 min after event, and written notice was issued an average of 37 min after onset. For more significant events that produced clouds higher than 7.5 km asl, these averages drop to 15 and 30 min, respectively. This improvement in timeliness is because larger events are typically seen in more data types, decreasing uncertainty about the existence and character of the eruption.

Future advancements in short-term forecasting and detection at volcanoes such as Bogoslof would be possible by improved alarm integration, better regional networks of infrasound and lightning sensors, decreased latency to receipt of satellite imagery, and 24/7 staffing of volcano observatories.

Data Availability

All datasets analyzed for this study are included in the manuscript and the Supplementary File S1.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the tools and approaches used during the eruption response. KW, AW, JL, DS, MH, and MC compiled the data on explosive events. MC and AW created the figures and compiled data on observatory alarm and warning times. MC analyzed the response data. MC, AW, MH, JL, DS, HS, and KW wrote the text.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by the USGS Volcano Hazards Program.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The eruption response was performed by a large team at AVO, which is a cooperative program of the United States Geological Survey, the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys, and the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feart.2018.00122/full#supplementary-material

FILE S1 | Text file of the Information Statement released by the Alaska Volcano Observatory on January 31, 2018.

Footnotes

- ^https://avo.alaska.edu/volcanoes/activity.php?volcname=Bogoslof&page=impact&eruptionid=1301

- ^http://wwlln.net/

- ^http://volcano.ssec.wisc.edu/

- ^http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vns/

- ^https://avo.alaska.edu/pdfs/cit3996_2017.pdf

References

Behnke, S. A., and McNutt, S. R. (2014). Using lightning observations as a volcanic eruption monitoring tool. Bull. Volcanol. 76:847. doi: 10.1007/s00445-014-0847-1

Behnke, S. A., Thomas, R. J., McNutt, S. R., Schneider, D. J., Krehbiel, P. R., Rison, W., et al. (2013). Observations of volcanic lightning during the 2009 eruption of Redoubt Volcano. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 259, 214–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.12.010

Bull, K. F., and Buurman, H. (2013). An overview of the 2009 eruption of Redoubt Volcano, Alaska. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 259, 2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.06.024

Cameron, C. E., Prejean, S., Coombs, M., Wallace, K., Power, J., and Roman, D. (2018). Alaska Volcano Observatory alert and forecasting timeliness: 1989–2017. Front. Earth Sci. 6:86. doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00086

Coombs, M. L., Bull, K. F., Vallance, J. W., Schneider, D. J., Thoms, E. E., Wessels, R. L., et al. (2010). Chapter 8, Timing, Distribution, and Volume of Proximal Products of the 2006 Eruption of Augustine Volcano, eds J. A. Power, M. L. Coombs, and J. T. Freymueller (Juneau, AK: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1769), 145–185.

De Angelis, S., Fee, D., Haney, M., and Schneider, D. (2012). Detecting hidden volcanic explosions from Mt. Cleveland Volcano, Alaska with infrasound and ground-coupled airwaves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39:21312. doi: 10.1029/2012GL053635

Doyle, E., McClure, J., Paton, D., and Johnston, D. M. (2014). Uncertainty and decision making: volcanic crisis scenarios. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 10, 75–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2014.07.006

Endo, E. T., and Murray, T. (1991). Real-time Seismic Amplitude Measurement (RSAM): a volcano monitoring and prediction tool. Bull. Volcanol. 53, 533–545. doi: 10.1007/BF00298154

Ewert, J., Guffanti, M., Cervelli, P., and Quick, J. (2006). The National Volcano Early Warning System (NVEWS). Los Angles, CA: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2006–3142.

Ewert, J. W. (2007). System for ranking relative threats of U.S. volcanoes. Nat. Haz. Rev. 8:4. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)1527-698820078:4(112)

Fee, D., and Matoza, R. S. (2013). An overview of volcano infrasound: from Hawaiian to Plinian, local to global. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 249, 123–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.09.002

Fee, D., McNutt, S. R., Lopez, T. M., Arnoult, K. M., Szuberla, C. A. L., and Olson, J. V. (2013). Combining local and remote infrasound recordings from the 2009 Redoubt Volcano eruption. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 259, 100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.09.012

Gardner, C. A., and Guffanti, M. C. (2006). U.S. Geological Survey’s Alert Notification System for Volcanic Activity. Los Angles, CA: U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2006-3139, 4.

Guffanti, M., and Miller, T. (2013). A volcanic activity alert-level system for aviation: review of its development and application in Alaska. Nat. Hazards 69, 1519–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11069-013-0761-4

Haney, M., Van Eaton, A., Lyons, J., Kramer, R. L., Fee, D., and Iezzi, A. M. (2018). Volcanic thunder from explosive eruptions at Bogoslof volcano, Alaska. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 3429–3435. doi: 10.1002/2017GL076911

Hotovec, A., Prejean, S., Vidale, J., and Gomberg, J. (2013). Strongly gliding harmonic tremor during the 2009 eruption of Redoubt Volcano. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 259, 89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.01.001

Hutchins, M. L., Holzworth, R. H., Brundell, J. B., and Rodger, C. J. (2012). Relative detection efficiency of the world wide lightning location network. Radio Sci. 47:RS6005. doi: 10.1029/2012RS005049

Li, B., and Ghosh, A. (2017). Near-continuous tremor and low-frequency earthquake activities in the Alaska-Aleutian subduction zone revealed by a mini seismic array. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5427–5435. doi: 10.1002/2016GL072088

Malone, S. D., Boyko, C., and Weaver, C. S. (1983). Seismic Precursors to the Mount St. Helens Eruptions in 1981 and 1982. Science 221, 1376–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.221.4618.1376

Marzocchi, W., and Bebbington, M. S. (2012). Probabilistic eruption forecasting at short and long time scales. Bull. Volcanol. 74, 1777–1805. doi: 10.1007/s00445-012-0633-x

Marzocchi, W., Newhall, C., and Woo, G. (2012). The scientific management of volcanic crises. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 247, 181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.08.016

Mastin, L., and Witter, J. (2000). The hazards of eruptions through lakes and seawater. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 97, 195–214. doi: 10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00174-2

McGimsey, R. G., Neal, C. A., and Doukas, M. P. (1995). Volcanic Activity in Alaska: Summary of Events and Response of the Alaska Volcano Observatory 1992. Los Angles, CA: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 9, 26.

Miller, T., McGimsey, R., Richter, D., Riehle, J., Nye, C., Yount, M., et al. (1998). Catalog of the Historically Active Volcanoes of Alaska. Juneau, AK: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 98-582, 104.

Neal, C. A., Murray, T. L., Power, J. A., Adleman, J. N., Whitmore, P. M., and Osiensky, J. M. (2010). Chapter 28, Hazard information Management, Interagency Coordination, and Impacts of the 2005–2006 Eruption of Augustine Volcano, eds J. A. Power, M. L. Coombs, J. T. Freymueller (Juneau, AK: U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1769), 645–667.

Okal, E. (2008). The generation of T waves by earthquakes. Adv. Geophys. 49, 1–65. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2687(07)49001-X

Papale, P. (2017). Rational volcanic hazard forecasts and the use of volcanic alert levels. J. Appl. Volcanol. 6:13. doi: 10.1186/s13617-017-0064-7

Powell, T., and Neuberg, J. (2003). Time dependent features in tremor spectra. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 128, 177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2012.01.001

Power, J., and Cameron, C. E. (2018). Analysis of the Alaska volcano observatory’s response time to volcanic explosions—1989 to 2016. Front. Earth Sci. 6:72. doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00072

Prata, A. J. (1989). Observations of volcanic ash clouds in the 10-12 micron window using AVHRR/2 data. Intl. J. Rem. Sens. 10, 751–761. doi: 10.1080/01431168908903916

Rose, W. I., Delene, D. J., Schneider, D. J., Bluth, G. J. S., Krueger, A. J., Sprod, I., et al. (1995). Ice in the 1944 Rabaul eruption cloud; implications for volcano hazard and atmospheric effects. Nature 375, 477–479. doi: 10.1038/375477a0

Schwaiger, H. F., Denlinger, R. P., and Mastin, L. G. (2012). Ash3D: a finite-volume, conservative numerical model for ash transport and Tephra deposition. J. Geophys. Res. 117:B04204. doi: 10.1029/2011JB008968

Sparks, R. S. J. (2003). Forecasting volcanic eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 210, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00124-9

Tepp, G. (2018). A repeating event sequence alarm for monitoring volcanoes. Seismol. Res. Lett. 89, 1863–1876. doi: 10.1785/0220170263

United States Geological Survey [USGS] (2007). Facing Tomorrow’s Challenges–U.S. Geological Survey Science in the Decade 2007–2017. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1309.

Van Eaton, A. R. Á., Amigo, D., Bertin, L. G., Mastin, R. E., Giacosa, J., and González, O. (2016). Volcanic lightning and plume behavior reveal evolving hazards during the April 2015 eruption of Calbuco volcano, Chile. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3563–3571. doi: 10.1002/2016GL068076

Waythomas, C. F., and Cameron, C. E. (2018). Historical Eruptions and Hazards at Bogoslof Volcano. Alaska: U. S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5085.

Keywords: eruption forecasting, Alaska, volcano monitoring, Bogoslof, volcanic infrasound, volcanic lightning, volcano seismology, hazard communication

Citation: Coombs ML, Wech AG, Haney MM, Lyons JJ, Schneider DJ, Schwaiger HF, Wallace KL, Fee D, Freymueller JT, Schaefer JR and Tepp G (2018) Short-Term Forecasting and Detection of Explosions During the 2016–2017 Eruption of Bogoslof Volcano, Alaska. Front. Earth Sci. 6:122. doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00122

Received: 19 March 2018; Accepted: 10 August 2018;

Published: 03 September 2018.

Edited by:

Nicolas Fournier, GNS Science, New ZealandReviewed by:

Stephen R. McNutt, University of South Florida, United StatesJan Marie Lindsay, University of Auckland, New Zealand

Silvio De Angelis, University of Liverpool, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2018 Coombs, Wech, Haney, Lyons, Schneider, Schwaiger, Wallace, Fee, Freymueller, Schaefer and Tepp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle L. Coombs, bWNvb21ic0B1c2dzLmdvdg==

Michelle L. Coombs

Michelle L. Coombs Aaron G. Wech

Aaron G. Wech Matthew M. Haney

Matthew M. Haney John J. Lyons

John J. Lyons David J. Schneider1

David J. Schneider1 David Fee

David Fee Janet R. Schaefer

Janet R. Schaefer