Abstract

Objective:

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we aimed to clarify the overall effects of functional foods and dietary supplements in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients.

Methods:

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane library, and Embase from January 1, 2000 to January 31, 2022 were systematically searched to assess the effects of functional foods and dietary supplements in patients with NAFLD. The primary outcomes were liver-related measures, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and hepatic fibrosis and steatosis, while the secondary outcomes included body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), triacylglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C). These indexes were all continuous variables, so the mean difference (MD) was used for calculating the effect size. Random-effects or fixed-effects models were used to estimate the mean difference (MD). The risk of bias in all studies was assessed with guidance provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.

Results:

Twenty-nine articles investigating functional foods and dietary supplements [antioxidants (phytonutrients and coenzyme Q10) = 18, probiotics/symbiotic/prebiotic = 6, fatty acids = 3, vitamin D = 1, and whole grain = 1] met the eligibility criteria. Our results showed that antioxidants could significantly reduce WC (MD: −1.28 cm; 95% CI: −1.58, −0.99, P < 0.05), ALT (MD: −7.65 IU/L; 95% CI: −11.14, −4.16, P < 0.001), AST (MD: −4.26 IU/L; 95% CI: −5.76, −2.76, P < 0.001), and LDL-C (MD: −0.24 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.46, −0.02, P < 0.05) increased in patients with NAFLD but had no effect on BMI, TG, and TC. Probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic supplementation could decrease BMI (MD: −0.57 kg/m2; 95% CI: −0.72, −0.42, P < 0.05), ALT (MD: −3.96 IU/L; 95% CI: −5.24, −2.69, P < 0.001), and AST (MD: −2.76; 95% CI: −3.97, −1.56, P < 0.0001) levels but did not have beneficial effects on serum lipid levels compared to the control group. Moreover, the efficacy of fatty acids for treating NAFLD was full of discrepancies. Additionally, vitamin D had no significant effect on BMI, liver transaminase, and serum lipids, while whole grain could reduce ALT and AST but did not affect serum lipid levels.

Conclusion:

The current study suggests that antioxidant and probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic supplements may be a promising regimen for NAFLD patients. However, the usage of fatty acids, vitamin D, and whole grain in clinical treatment is uncertain. Further exploration of the efficacy ranks of functional foods and dietary supplements is needed to provide a reliable basis for clinical application.

Systematic review registration:

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero, identifier: CRD42022351763.

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), renamed metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) in 2020 (1), is a chronic and progressive metabolic disease characterized by excessive fat deposition in the hepatocytes in the absence of alcohol exposure or other identifiable causes. This may finally lead to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other severe liver diseases (2, 3), adversely impacting people's quality of life. It is reported that the global prevalence of NAFLD is 24.1%, of which the highest are in the Middle East and South America and the lowest are in Africa (4, 5). The prevalence of NAFLD in China is about 30%, and this rate is expected to increase further as obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are gradually becoming the most common diseases in humans (6, 7).

The occurrence and development of NAFLD depend on multiple factors, including metabolic comorbidities, gut microbiome, and environmental and genetic factors (8). Except for the genetic factors that human beings cannot intervene, the other three conditions are closely related to our current lifestyle and affect each other. In particular, they are influenced by a sedentary lifestyle and the intake of high-energy foods, including fried foods, desserts, and soft drinks (9). The habits mentioned above account for obesity, T2DM, and hyperlipidemia, which are major risk factors for NAFLD (10). It is reported that the prevalence of NAFLD is as high as 60–90%, 27–92%, and 28–70% in patients with obesity, hyperlipidemia, and T2DM, respectively (6).

As no approved pharmacological options exist for NAFLD, lifestyle modifications, including increased physical activity and reduced energy intake, remain the first line of therapy (10, 11); however, consistent low-energy intake and exercise are difficult to achieve in both adults and children. Recently, researchers have found that gut microbiota plays an important role in the pathophysiology of metabolic diseases, especially obesity-related disorders, including metabolic syndrome and NAFLD (12). The hypothesis underlying its mechanism is that decreased microbial gene richness leads to a decline in bacteria producing short-chain fatty acids and an increase in bacteria synthesizing lipopolysaccharide, which can induce the development of steatosis and trigger systemic inflammation (13, 14). Early probiotic, prebiotic, symbiotic, and fecal microbiota transfer interventions may prevent NAFLD exacerbation (15, 16). Meanwhile, some investigations have reported that the intake of dietary supplements (such as vitamin D, vitamin E, and fatty acid) (17, 18) and functional foods (such as garlic powder, Nigella sativa, sumac powder, and olive oil) (19–23) may ameliorate and/or reverse NAFLD, which may be due to their antioxidant properties. For example, organosulfur compounds in garlic powder and flavonoids in green tea extract belong to the category of functional foods, but in terms of properties, they exhibit antioxidant activities. Their protection is mainly achieved in NAFLD by decreasing oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (12, 20, 24). Although some functional foods may have other properties, such as anticancer and antimicrobial effects (12, 25), these effects on NAFLD are unclear and need to be further explored.

Some functional foods and dietary supplements may decrease liver damage, such as liver disease without cirrhosis, there are inconsistencies in the results obtained by different studies. Considering the inconsistencies of clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs), we performed this systematic review and meta-analysis to provide clinicians, nutritionists, and other health professionals with relatively unified clinical evidence to help them make relevant clinical decisions, that is, whether functional foods and dietary supplements should be applied to NAFLD management.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Eligibility criteria

This study was only limited to RCTs that reported the effects of functional foods and dietary supplements on liver-related indices in patients suffering from NAFLD, regardless of the method of diagnosis [fibroscan/ultrasonography/elastography technique/magnetic resonance spectroscopy/acoustic structure quantification (ASQ) liver scan/percutaneous liver biopsy/computed tomography (CT)], obesity status, and other metabolic syndrome statuses. Animal or in vitro studies, case reports, abstracts, guidelines, reviews, meta-analyses, and conference proceedings were excluded. Two reviewers determined the inclusion and exclusion criteria jointly and retrieved articles separately.

2.1.1. Inclusion criteria

(1) Patients were adults (≥18-year-old) with NAFLD; (2) interventions in studies included: dietary supplementation (synbiotic, symbiotic, prebiotic, probiotic, vitamin, and omega-3 supplementation) and functional foods only (exhibiting effects, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antimicrobial action); (3) the placebo in the control group was identical in color, shape, size, and packaging to that of the intervention group; (4) the main outcomes were the changes in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST), hepatic fibrosis, and hepatic steatosis; (5) there were no restrictions on the duration of intervention; (6) only publications written in English were chosen, but the country was not a limiting factor.

2.1.2. Exclusion criteria

(1) Patients with advanced liver disease or/and gastrointestinal dysfunction; (2) interventions in studies combined with exercise or/and active lifestyle modification, medicine, weight loss surgery, and enteral and/or parenteral nutrition treatment; (3) studies that did not report transaminase values (AST and/or ALT).

2.2. Search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA). Its protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022351763). One of the researchers was responsible for keyword searches across four major electronic databases: PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane library, and Embase, from January 1, 2000 to January 31, 2022. The search strategy and results were finalized through group discussions.

The search method was as follows: (“non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “NAFLD” OR “nonalcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “fatty liver, nonalcoholic” OR “fatty livers, nonalcoholic” OR “liver, nonalcoholic fatty” OR “livers, nonalcoholic fatty” OR “nonalcoholic fatty liver” OR “nonalcoholic fatty livers” OR “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis” OR “nonalcoholic steatohepatitides” OR “steatohepatitides, nonalcoholic” OR “steatohepatitis, nonalcoholic”) AND (“diet” OR “diets” OR “dietary supplements” OR “dietary supplement” OR “supplements, dietary” OR “dietary supplementations” OR “supplementations, dietary” OR “food supplementations” OR “food supplements” OR “food supplement” OR “supplement, food” OR “supplements, food” OR “nutraceuticals” OR “nutraceutical” OR “nutriceuticals” OR “nutriceutical” OR “neutraceuticals” OR “neutraceutical” OR “herbal supplements” OR “herbal supplement” OR “supplement, herbal” OR “supplements, herbal” OR “nutrients” OR “nutrient” OR “macronutrients” OR “macronutrient” OR “micronutrient” OR “micronutrients” OR “functional food” OR “food, functional” OR “foods, functional” OR “functional foods”) AND (“randomized controlled trial” [publication type] OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “randomized” OR “placebo”).

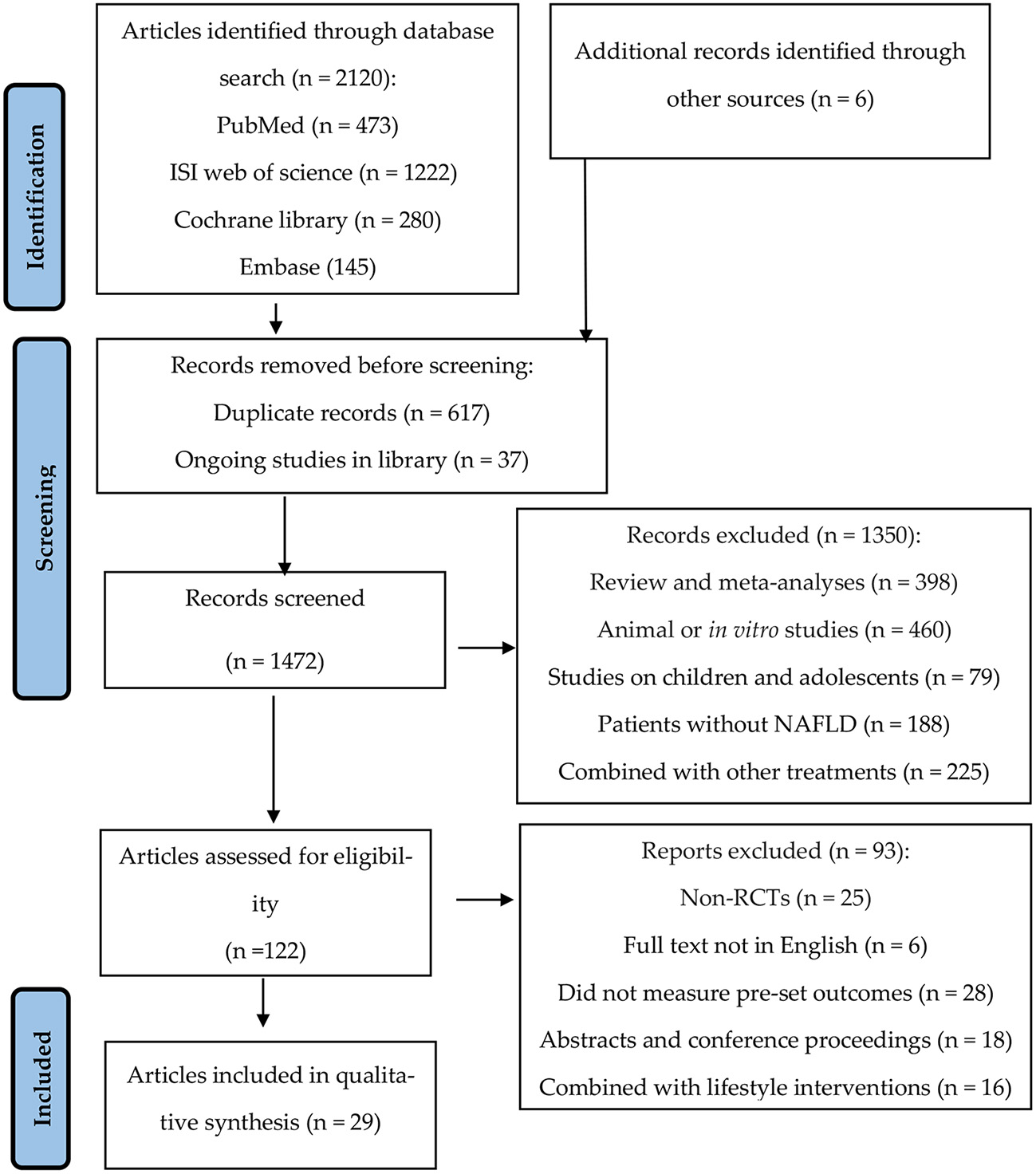

Literature was managed using a software program (EndNote X8.1, Thomson Reuters, New York, USA), in which the “find duplicates” function was used to eliminate duplicate papers. The studies inconsistent with our eligibility criteria were screened out using the title and abstract. The remaining articles were fully read, and the qualified studies were chosen according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 1). All stages of the selection process were repeated by another author, and the differences were solved through group discussion.

Figure 1

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram detailing the study selection process for systematic literature review.

2.3. Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The data from each trial were extracted independently by two authors using a standardized, pre-designed data-extraction form. The data included: (1) study characteristics (first author's name, year of publication, country, and sample size); (2) baseline patient characteristics (targeted population and age); (3) intervention characteristics (type and dose in the intervention and control groups and duration of follow-up); (4) main outcomes (outcome measures and the changes to outcome measures post-intervention). The risk of bias in all studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (RoB2) provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (26). The tool contains seven domains, including method of sequence generation, concealment, blinding, blinded outcome, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases. All these domains were respectively classified as low risk, high risk, and unclear risk of bias according to the guideline in the Cochrane Handbook. The trial was considered to have “good” quality if it was low-risk for at least three items, “fair” if it was low-risk for two items, and “weak” if it was low-risk for less than two items (27, 28). The quality assessment was separately done by two authors. There was little disagreement between them.

2.4. Outcome measures

The primary outcomes were liver-related measures, such as transaminase values (AST and/or ALT), and hepatic fibrosis and steatosis. Secondary outcomes included anthropometric measurements [such as body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC)] and lipid analyses [triacylglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)].

2.5. Statistical analysis

The mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) between intervention and placebo groups at baseline and post-intervention were used for each parameter in this review and meta-analysis. I2 value was used to evaluate heterogeneity. When the I2 value was < 50%, the fixed-effects model was used; otherwise, the random-effects model was adopted. We used a narrative synthesis when the data were too heterogeneous to be aggregated or when there were only a few articles on intervention measures (29). The publication bias was evaluated using Begg's rank correlation test and Egger's regression asymmetry test. Sensitivity analysis was carried out to define whether the overall effect depended on any particular study. The statistical significance was assessed at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using Review Manager 5.4 and Stata 12.0.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1. We selected 2,120 articles through keywords and six articles through references, from which 617 duplicate and 37 ongoing studies were removed. Next, we excluded 1,350 studies after screening the title and abstract. A total of 122 studies were considered eligible and needed a full-text review. Finally, 93 articles were excluded after reading the full text because of the following reasons: non-RCTs; full text not in English; did not measure pre-set outcomes (AST/ALT/hepatic fibrosis and steatosis); abstracts and conference proceedings; and combined with lifestyle interventions (physical exercise and/or weight loss diet). Finally, 29 articles were included in this review and meta-analysis.

3.2. Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. Fifteen trials (20, 21, 23, 30–41) evaluated phytonutrients; six trials (42–47) evaluated probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic; three trials (48–50) evaluated coenzyme Q10; three trials (51–53) evaluated fatty acids; and one trial (54, 55) evaluated vitamin D and whole grain separately in the management of NAFLD. The duration of the intervention varied from 4 weeks to 18 months. The patients were all adults, and the studies were from different countries, including Iran, Korea, Brazil, North America, the United Kingdom, Italy, Malaysia, and China. Among the 29 included studies, 23 (79.31%) articles studied patients with NAFLD only, 2 (6.90%) articles studied NAFLD patients with diabetes, and 4 (13.79%) articles were on overweight/obese patients with NAFLD. The study design of all included RCTs was parallel (Table 1).

Table 1

| References | Country | Sample size | Target population | Age (years) | Duration | Intervention group | Control group | Outcomes measures | Changes to outcome measures post intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aller et al. (42) | Spain | 30 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 3 months | Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus | Starch | BMI/weight/FM/WHR/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/insulin/ HOMA/TNF-α/ALT/AST/GGT | ↓ALT/AST/GGT |

| Sangouni et al. (23) | Iran | 90 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 12 weeks | Garlic powder | Starch | Hepatic steatosis/weight/BMI/WC/ALT/ASL/GGT/ALP/ TC/TAG/HDL/LDL | ↓Hepatic steatosis/ALT/ASL/GGT/TC/HDL/LDL |

| Pezeshki et al. (30) | Iran | 80 | NAFLD with obesity | 20–50 | 12 weeks | Green tea extract | Placebo | Weight/BMI/ALT/AST/ALP | ↓ALT/AST/ALP |

| Asgharian et al. (43) | Iran | 80 | NAFLD | 18–60 | 8 weeks | Probiotic | Starch | Steatosis grade/ALT/AST/CRP/weight/BMI | ↓Steatosis grade |

| Han et al. (31) | Korea | 96 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 8 weeks | SPB-201 | Crystallin cellulose | ALT/AST/blood RT/ALP/glucose/BUN/Cr/UA | ↓ALT/AST |

| Soleimani et al. (garlic) (20) | Iran | 110 | NAFLD | 20–70 | 15 weeks | Garlic powder | Placebo | Weight/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/FBS/HbA1c/ALT/AST/ hepatic steatosis | ↓Hepatic steatosis/weight/TC/TG/LDL/FBS/HbA1c/ ALT/AST |

| Soleimani et al. (Propolis) (32) | Iran | 54 | NAFLD | 18–60 | 4 months | Poplar propolis | Placebo | Weight/fat mass/fat free mass/FBS/insulin/HOMA-IR/QUICKI/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/Hs-CRP/albumin/ALP/ALT/AST/GGT/T-Bil/D-Bil/hepatic steatosis | ↓Hs-CRP//hepatic steatosis |

| Scorletti et al. (DHA) (53) | UK | 103 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 15 months | DHA/EPA | Olive oil | BMI/WC/FBS/MRI subcutaneous fat/MRI visceral fat/HbA1c/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/AST/ALT/liver fat/liver fibrosis score/NAFLD fibrosis score | ↑HDL |

| Scorletti et al. (synbiotics) (44) | UK | 104 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 10 months | Polymerization | Maltodextrin | Weight/BMI/fat/FBS/HbA1c/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/ AST/ALT/GGT/MRS-measured liver/ELF score | ↓NAFLD fibrosis score |

| Jafarvand et al. (48) | Iran | 44 | NAFLD | 20–65 | 4 weeks | CoQ10 | Placebo | BMI/WC/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/AST/ALT | ↓WC/AST |

| Askari et al. (33) | Iran | 50 | NAFLD | 20–66 | 12 weeks | Cinnamon | Wheat flour | FBS/QUICKI/HOMA/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/ASL/ALT/ GGT/hs-CRP | ↓FBS/HOMA/T/LDL/TG/ASL/ALT/GGT/hs-CRP |

| Farsi et al. (49) | Iran | 42 | NAFLD | 19–54 | 12 weeks | CoQ10 | Starch | Weight/WC/HC/WHR/BMI/NAFLD/grade/TNF-α/adiponection/leptin/hs-CRP/AST/ALT/GGT/AST to ALT ratio | ↓hs-CRP/AST/GGT/NAFLD grade/TNF-α/leptin; ↑adiponection |

| Izadi et al. (34) | Iran | 70 | NAFLD | 20–55 | 8 weeks | Sour tea powder | Placebo | Weight/BMI/WC/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/AST/ALT | ↓TG/ALT/AST/ |

| Barchetta et al. (54) | Italy | 65 | NAFLD with DM | 25–70 | 24 weeks | Cholecalciferol | Placebo | Hepatic fat fraction/BMI/WC/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/FBG/HbA1c/AST/ALT/r-GT/AST to ALT/FHOMA-IR/QUICKI/adiponectin | No difference |

| Bae et al. (35) | Korea | 78 | NAFLD with DM | 20–70 | 12 weeks | Carnitine-orotate complex | Placebo | Weight/BMI/WC/FBS/HbA1c/HOMA-IR/HOMA-B/AST/ALT/γ-GT/TG/HDL/LDL/CT attenuation | ↓ALT/HbA1c/liver attenuation values |

| Cansanção et al. (52) | Brazil | 44 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 6 months | n-3 PUFA | Olive oil | ALT/AST/ALP/GGT/FBS/HbA1c/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/BMI/BMI/WC/WHR/liver fibrosis | ↓ALP/liver fibrosis |

| Hosseinikia et al. (36) | Iran | 90 | NAFLD | 18–65 | 12 weeks | Quercetin | Placebo | BMI/WHR/ALT/AST/GGT/TNF-α/hs-CRP/TC/TG/HDL/LDL | ↓BMI/WHR/TNF-α |

| Farhangi et al. (50) | Iran | 44 | NAFLD | 20–65 | 4 weeks | CoQ10 | Placebo | FSG/insulin/HOMA-IR/QUICKI/AST/ALT/vaspin/chemerin/pentraxin | ↓AST |

| Masoumeh et al. (55) | Iran | 112 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 12 weeks | Whole grain foods | Usual cereals | Grade of fatty liver/ALT/AST/GGT/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/FBS/HOMA-IR/QUICKI/insulin | ↓Grade of fatty/liver/ALT/AST/GGT |

| Darand et al. (21) | Iran | 50 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 12 weeks | Nigella sativa seed powder | Starch | Weight/BMI/WC/HC/WHR/ALT/AST/GGT/hs-CRP/TNF-α/NF-κB/fibrosis grade/steatosis/percentage of steatosis | ↓hs-CRP/TNF-α/NF-κb/percentage of steatosis |

| Mohamad Nor et al. (45) | Malaysia | 46 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 6 months | Multi-strain probiotics | Placebo | Liver stiffness/AST/ALT/GGT/steatosis score/fibrosis score/BMI/TG/TC/fasting glucose | No difference |

| Mohammad Shahi et al. (37) | Iran | 42 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 8 weeks | Phytosterol | Starch | AST/ALT/GGT/AST to ALT ratio/TC/TG/LDL/HDL/LDL to HDL ratio/VLDL/TC to HDL ratio/TNF-α/hs-CRP/adiponectin/leptin | ↓AST/ALT/LDL |

| Rashidmayvan et al. (51) | Iran | 44 | NAFLD | 20–60 | 8 weeks | NS oil | Paraffin oil | Weight/BMI/WC/WHR/FBS/TG/TC/HDL/LDL/VLDL/insulin/AST/ALT/GGT/TNF-α/hs-CRP | ↓TG/TC/HDL/LDL/VLDL/FBS/AST/ALT/TNF-α/hs-CRP; ↑HDL |

| Zhang et al. (38) | China | 74 | NAFLD | 25–65 | 12 weeks | Anthocyanin | Maltodextrin | Weight/BMI/WC/HC/WHR/AST/ALTNAFLD fibrosis score/TC/TG/LDL/DL/FBG/insulin/HOMA-IR/OGTT | ↓ALT/HOMA-IR/2-h glucose |

| Chong et al. (47) | UK | 42 | NAFLD | 25–70 | 10 weeks | VSL#3® probiotic | Placebo | TC/TG/LDL/HDL/HbA1c//HOMA-IR/TAC/hs-CRP/ALT/AST/mode ASQ/NAFLD fibrosis risk score | No difference |

| Navekar et al. (39) | Iran | 46 | NAFLD with overweight/obesity | 20–60 | 12 weeks | Turmeric powder | Placebo | FBS/insulin/HOMA-IR/leptin/AST/ALT | ↓FBS/insulin/HOMA-IR/leptin |

| Ahn et al. (46) | Korea | 68 | NAFLD with overweight or obesity | 19–75 | 12 weeks | Six bacterial species | Placebo | Weight/BMI/visceral fat/total fat mass/total body fat/visceral fat grade/WHR/CAP/liver stiffness/intra-hepatic fat fraction/TG/TC/glucose/insulin/AST/ALT/HOMA-I/total muscle mass/skeletal muscle/HDL/LPS/TNF-α | ↓Intra-hepatic fat fraction/TG/weight |

| Cicero et al. (40) | Iran | 65 | NAFLD | ≥18 | 8 weeks | Phospholipidated curcumin | Placebo | Weight/BMI/leptin/adiponectin/leptin:adiponectin/FBS/TG/TC/LDL/HDL/AST/ALT | ↓leptin/leptin: adiponectin; ↑adiponectin/HDL |

| Namkhah et al. (41) | Iran | 44 | NAFLD with overweight/obesity | 20–65 | 4 weeks | Naringenin | Placebo | NAFLD grades/NFS levels/weight/BMI/WC/AST/ALT/TG/TC/HDL/LDL | ↓NAFLD grades/TG/TC/LDL; ↑HDL |

Characteristics of included trials.

NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; SPB-201, powdered-water extract of Artemisia annua; DM, diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; WC, weight circumference; WHR, waist to height ratio; FBS, fasting blood sugar; HOMA–IR, homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triacylglyceride; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CRP, C-reactive protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; UK, the United Kingdom. ↓, indicated a decrease in outcome measures. ↑, indicated an increase in outcome measures.

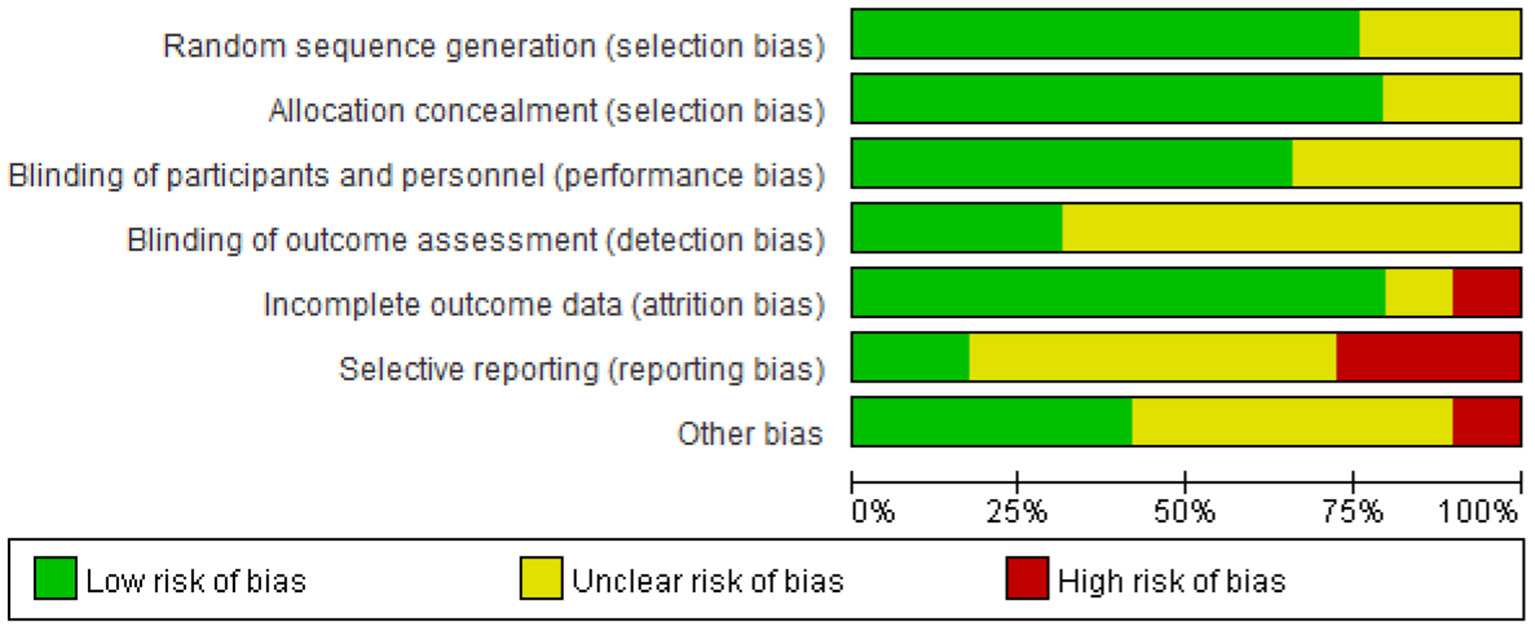

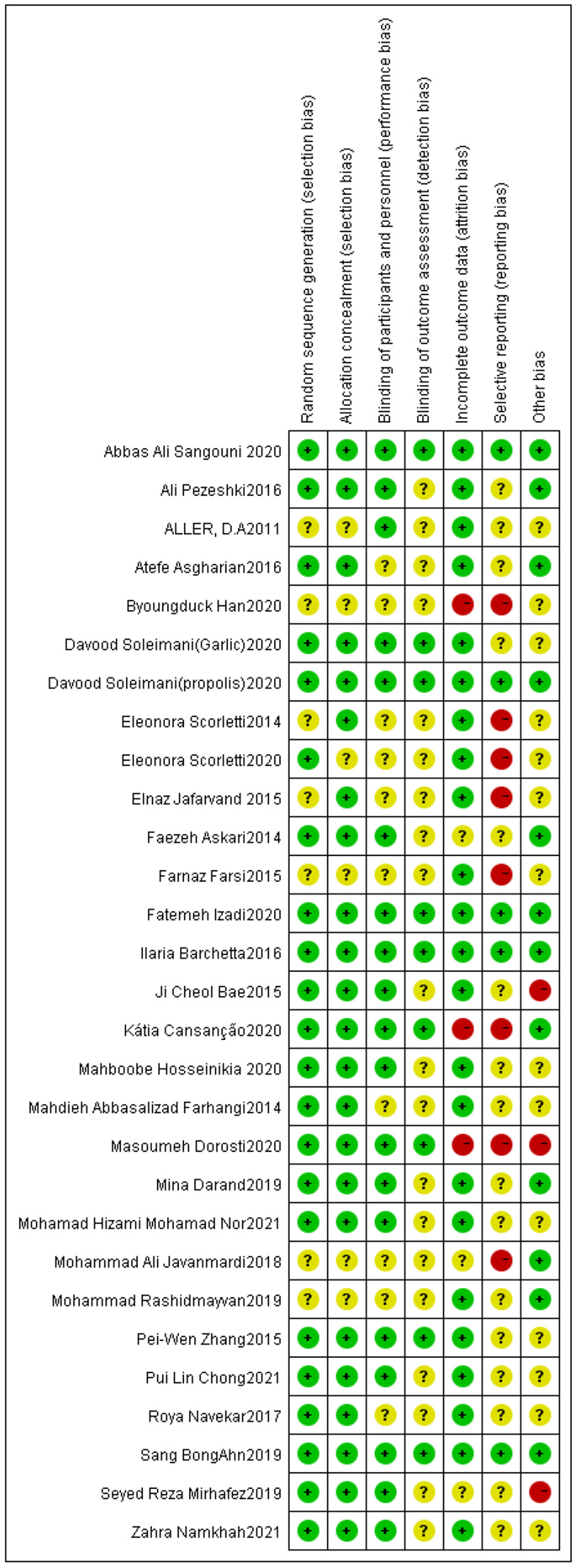

3.3. Risk of bias in studies

Out of all the studies, 21 trials (20, 21, 23, 30, 32–36, 38–41, 43, 45–47, 50, 52, 54, 55) had “good” quality, while five trials (42, 44, 48, 51, 53) were “fair”. Additionally, the remaining three trials (31, 37, 49) were “weak”. Figures 2, 3 show the results of each source of bias.

Figure 2

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 3

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.4. Effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on anthropometric parameters

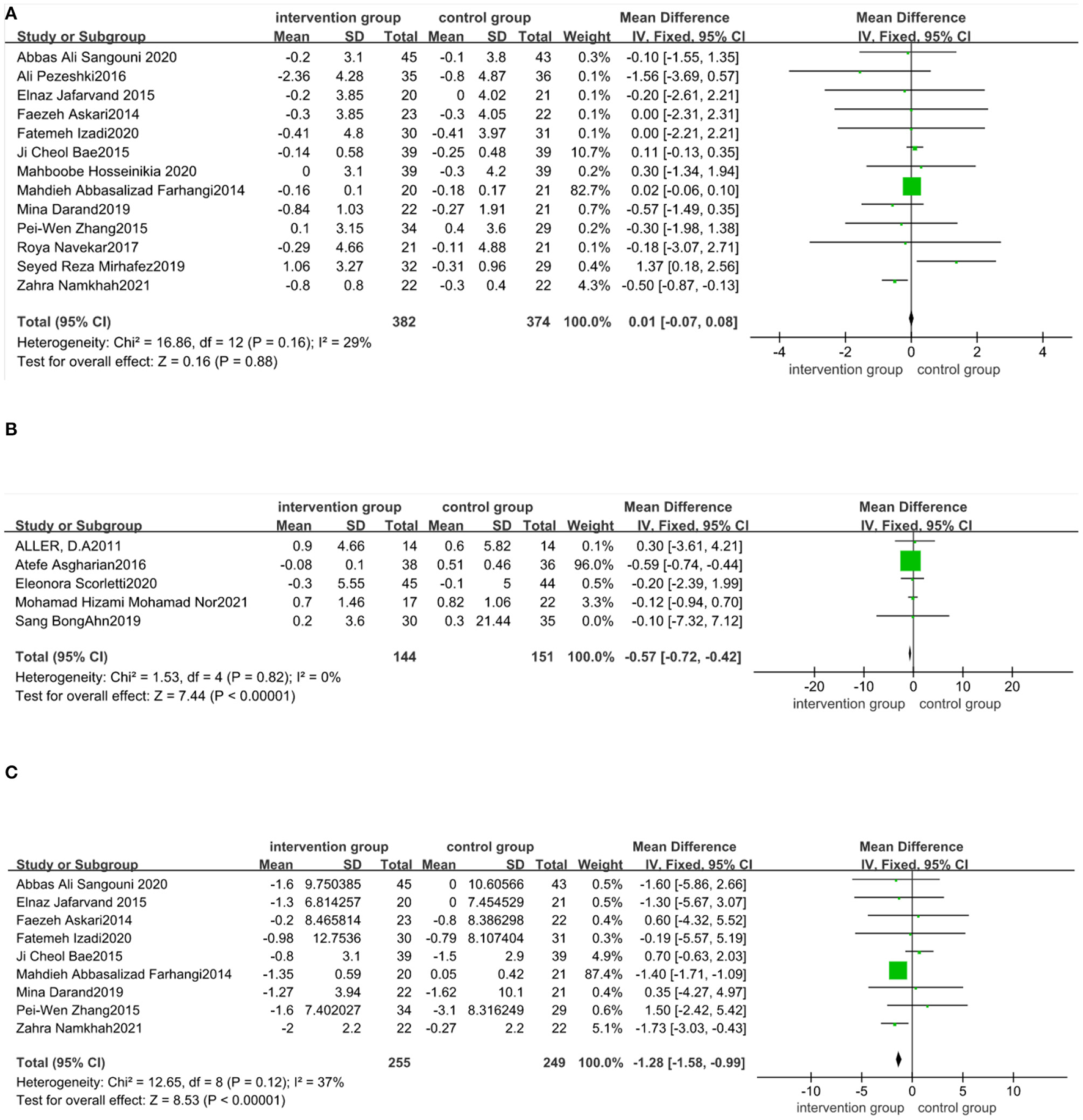

The effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on BMI was examined in 22 clinical trials. It was seen that 13 out of 22 trials (21, 23, 30, 33–36, 38–41, 48, 50) were about antioxidants (phytonutrients and coenzyme Q10), five (42–46)on probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic, three (51–53) on fatty acids, and one (54) on vitamin D. The meta-analysis showed no significant effect of antioxidants on BMI compared to the placebo (MD: 0.01 kg/m2; 95% CI: −0.07, 0.08, P > 0.05) (Figure 4A). There was no heterogeneity in these included studies (I2 = 29.0%, P = 0.16). As shown in Figure 4B, BMI significantly decreased (MD: −0.57 kg/m2; 95% CI: −0.72, −0.42, P < 0.05) after taking probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic in NAFLD patients, with no heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.82). Sensitivity analysis showed that the overall effect did not depend on any single study (Appendix S1 in the Supplementary material 1).

Figure 4

Forest plot of the effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on anthropometric indices (effect of A: antioxidants on BMI; B: probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on BMI; and C: antioxidants on WC).

The proportion and type of fatty acids varied between the three studies; oil composition contained docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)/eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)/linoleic acid/oleic acid and linolenic acid. Three studies used different oils as a placebo. All three studies showed that BMI did not change significantly in NAFLD patients after using fatty acids (51–53). Barchetta et al. (54) reported that BMI did not change after taking vitamin D and placebo.

Nine studies (21, 23, 33–35, 38, 41, 48, 50) reported the effect of supplements on WC. Our meta-analysis reported that WC declined significantly in nine antioxidant trials compared to the control group (MD: −1.28 cm; 95% CI: −1.58, −0.99, P < 0.05). The effect was homogeneous across the included trials (I2 = 37%, P = 0.12) (Figure 4C). The effects of probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on WC have not been reported. Sensitivity analysis showed that the exclusion of any trials did not affect the results (Appendix S2 in the Supplementary material 1). Four studies (51–54) noted no changes in the WC after taking fatty acid (three trials) and vitamin D (one trial).

No publication bias was found for BMI (Begg's test P = 0.82; Egger's test P = 0.600) and WC (Begg's test P = 0.348; Egger's test P = 0.829).

3.5. Effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on the liver function

Twenty-nine datasets evaluated the effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on ALT. Eighteen out of 29 trials were about antioxidants (phytonutrients and coenzyme Q10), six (42–47) on probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic, three (51–53) on fatty acids, one (55) on whole grain, and one (54) on vitamin D.

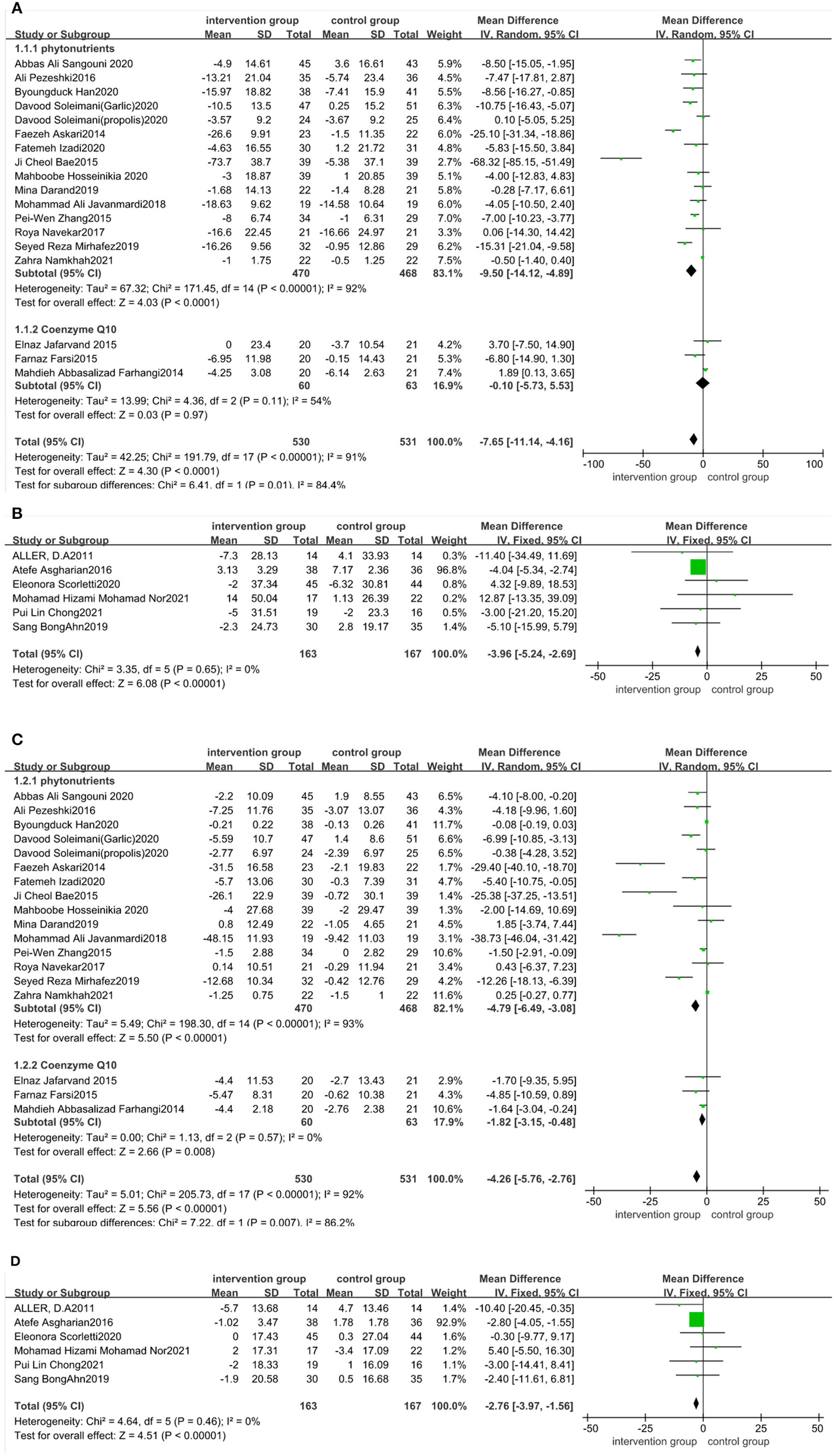

There was a statistical significance in the mean difference of ALT levels in the antioxidant-supplemented group compared to the control group (MD: −7.65 IU/L; 95% CI: −11.14, −4.16, P < 0.0001). There was high heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 91%, P < 0.00001). Subgroup analysis based on the type of antioxidants (phytonutrients or coenzyme Q10) was performed using data from 18 studies. There was statistically significant difference in ALT reductions between phytonutrients group and control group (MD: −9.5 IU/L; 95% CI: −14.12, −4.89, P < 0.0001), but high heterogeneity of these studies still existed (I2 = 92%, P < 0.00001). Heterogeneity was attenuated among those studies taking coenzyme Q10 (I2 = 54%, P = 0.11) (Figure 5A), but the ALT reductions had no difference. The intake of probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic supplements led to a more significant decrease in ALT compared with control (MD: −3.96 IU/L; 95% CI: −5.24, −2.69, P < 0.001), with no heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.65) (Figure 5B). Sensitivity analysis indicated that no trial changed the pooled effect size (Appendix S3 in the Supplementary material 1). Publication bias were seen for ALT (Begg's test P = 0.722; Egger's test P = 0.016).

Figure 5

Forest plot of the effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on liver function (effect of A: antioxidants on ALT; B: probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on ALT; C: antioxidants on AST; and D: probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on AST).

The effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on AST levels was examined in 29 clinical trials. The literature distribution on AST was consistent with that on ALT. Our meta-analysis revealed a significant reduction in AST levels after taking antioxidant supplements (MD: −4.26 IU/L; 95% CI: −5.76, −2.76, P < 0.00001), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 92%, P < 0.00001). Studies of phytonutrients or coenzyme Q10 were subgroup analyzed. The AST reductions were significantly different between the phytonutrients group and control group (MD: −4.79 IU/L; 95% CI: −6.49, −3.08, P < 0.00001), with high heterogeneity among those studies (I2 = 93%, P < 0.00001). Meanwhile, the AST reductions had significant difference in studies taking coenzyme Q10 (MD: −1.82 IU/L; 95% CI: −3.15, −0.48, P = 0.008), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.57) (Figure 5C). The AST levels after taking probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic showed a decrease in the antioxidant-supplemented group compared to the control group (MD: −2.76; 95% CI, −3.97, −1.56, P < 0.0001), with no heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%, P = 0.46) (Figure 5D). Sensitivity analysis revealed that no specific study affected pooled effects (Appendix S4 in the Supplementary material 1). publication bias was seen for AST levels (Begg's test P = 0.985; Egger's test P = 0.000).

In three trials (51–53) on fatty acids, Rashidmayvan et al. (51) reported that Nigella sativa oil containing linoleic acid, oleic acid, and linolenic acid reduced ALT and AST levels, whereas Cansanção et al. (52) and Scorletti et al. (53) found that supplements containing DHA and EPA did not affect ALT and AST levels. Barchetta et al. (54) did not observe any discrepancy in AST and ALT levels between the vitamin D and control groups. Masoumeh et al. (55) found that ALT and AST levels decreased significantly after taking whole grain compared to the control group. The outcome indicators of hepatic fibrosis and steatosis were too few to be described.

3.6. Effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on lipid profiles

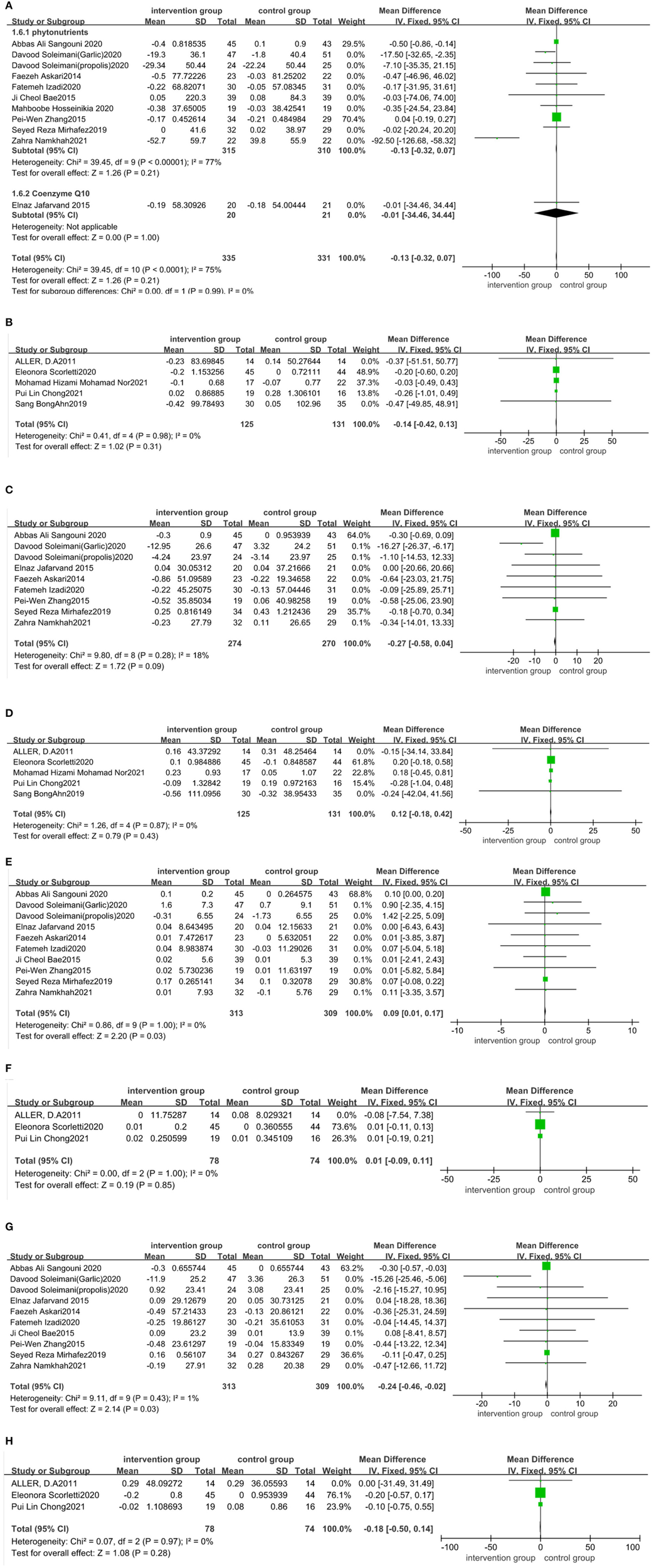

Eighteen trials (20, 23, 32–36, 38, 40–42, 44–48, 51, 53–55) assessed the effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on TG. The quantitative analysis of TG values indicated no significant reduction in TG after antioxidant supplementation [11 trials (20, 23, 32–36, 38, 40, 44, 48)] (MD: −0.13 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.32, 0.07, P > 0.05) with high heterogeneity (I2 = 75%, P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). We were not able to perform a subgroup analysis to assess the source of heterogeneity as the number of papers on coenzyme Q10 subgroup was small. Our meta-analysis of five trials (43–47) involving probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic intake illustrated that these supplements had an unnoticeable effect on TG reduction (MD: −0.14 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.42, 0.13, P > 0.05), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P > 0.05) (Figure 6B). Sensitivity analysis showed that the results did not depend on any single study (Appendix S5 in the Supplementary material 1).

Figure 6

Forest plot of the effect of functional foods and dietary supplements on lipid profiles (effect of A: antioxidants on TG; B: probiotic/ symbiotic/prebiotic on TG; C: antioxidants on TC; D: probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on TC; E: antioxidants on HDL-C; F: probiotics/symbiotic/prebiotic on HDL-C; G: antioxidants on LDL-C; and H: probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic on LDL-C).

Consistently, nine datasets (30, 32–35, 39, 41, 42, 49) indicated no significant reduction in TC levels after taking antioxidant supplements compared to the control group (MD: −0.27 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.58, 0.04, P > 0.05) (Figure 6C), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 18%, P > 0.05). Five datasets (43–47) on probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic supplements reported no significant decrease in TC levels after intervention (MD: 0.12 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.18, 0.42, P > 0.05) (Figure 6D), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P > 0.05). The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that excluding either study from the analysis did not change the overall effect (Appendix S6 in the Supplementary material 1).

The pooled effect size of 10 trials (30, 32–36, 39, 41, 42, 49) reported a significant impact of the antioxidant supplements on HDL-C (MD: 0.09 mg/dL; 95% CI: 0.01, 0.17, P < 0.05) and LDL-C (MD: −0.24 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.46, −0.02, P < 0.05), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P > 0.05; I2 = 1%, P > 0.05, respectively) (Figures 6E, G). Three trials (43–45) reported no significant effect of probiotic, symbiotic, and prebiotic supplementation on HDL-C (MD: 0.01 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.09, 0.11, P > 0.05) and LDL-C (MD: −0.18 mg/dL; 95% CI: −0.5, 0.14, P > 0.05), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P > 0.05 for both) (Figures 6F, H). We performed a sensitivity analysis and found that excluding a particular study from the analysis did not change the overall effect on HDL-C and LDL-C (Appendices S7, S8 in the Supplementary material 1).

Four trials (52–55) reported no difference in TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C levels of DHA/EPA, vitamin D, or whole grainarms of the trial. Rashidmayvan et al. (51) reported that Nigella sativa oil decreased TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C levels with significant differences between the NS seed and placebo groups.

No evidence of publication bias was seen for TG (Begg's test P = 0.753; Egger's test P = 0.120), TC (Begg's test P = 0.488; Egger's test P = 0.424), LDL-C (Begg's test P = 0.913; Egger's test P = 0.0.138), and HDL-C (Begg's test P = 0.743; Egger's test P = 0.084).

4. Discussion

NAFLD is considered a metabolic disorder that is closely related to lifestyle. The number of studies about the relationship between diet, nutrition, food, and NAFLD has increased in recent years (56), but there have been no recommendations in the guidelines in terms of this relationship. This systematic review and meta-analysis summarized the adjuvant therapy effects of various nutritional interventions on NAFLD, including antioxidants, probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic, fatty acid supplements, vitamin D, and whole grain, providing guidance for clinical application.

A total of 1,907 patients from 29 trials were included in this review. Eighteen trials assessed the impact of antioxidants on NAFLD. The mechanism may be related to their antioxidant activity and the ability to scavenge free radicals, such as inhibiting the early formation of lipid peroxides in the liver, blocking the transmission process of free radicals by interrupting the chain reaction, or indirectly scavenging free radicals by acting on enzymes related to free radicals (57, 58). For humans, it can reduce liver inflammation, decrease oxidative stress, inhibit lipid oxidation in serum, and finally reduce serum aminotransferase and improve serum lipids (24). This meta-analysis found that the antioxidants significantly reduced WC, ALT, AST, and LDL-C and increased HDL-C in NAFLD patients but did not change the BMI, TC, and TG levels. This meta-analysis found that the antioxidants significantly reduced WC, ALT, AST, and LDL-C and increased HDL-C in NAFLD patients but did not change the BMI, TC, and TG levels. The positive results were consistent with the action mechanism of antioxidants, whose hypolipidemic properties were related to the reduction of liver adipogenesis (20). With the action of antioxidants, inflammation induced by hepatocyte steatosis was improved, and ALT/AST levels were significantly decreased. WC, which is closely related to visceral fat deposition (59), also decreased significantly. Moreover, the amount of cholesterol decreased, especially oxidized LDL, HDL increased (60), which was consistent with the results of this study. On the other hand, TC reflects the sum of all LDL-C, HDL-C and VLDL in serum. In this study, LDL-C decreased and HDL-C increased, so the resulting overall lack of change can be understood. The lack of significant changes in TG may be due to the fact that only a small part of TG is synthesized by the body itself, and most TG is obtained from diet, which is influenced by many factors (61). Finally, elevated BMI is not a prerequisite for the diagnosis of NAFLD, and many of the included studies included patients with normal BMI, so it is not difficult to understand the lack of changes in BMI levels caused by antioxidants. However, due to the different dosages and types of antioxidants used in each trial, its effect should be further investigated in clinical application.

Six randomized trials indicated that taking probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic decreased BMI, ALT, and AST levels but did not have favorable effects on blood lipid levels compared to the control group. The results were inconsistent with the previous review (62). This difference might be related to the type of strains. Studies have shown that different strains have different effects on liver function and blood lipid levels (12, 15, 63). However, since few trials were included in the study, the respective effects of probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic could not be compared through subgroup analysis. In general, their adjuvant therapeutic effect on NAFLD is clear. The potential mechanism may involve regulating human metabolism by decreasing inflammatory markers and altering lipid profile (3). However, the dose and duration of their clinical application are ill-defined; therefore, more multi-central clinical research is needed to provide detailed guidance in the future.

Three RCTs reported the role of fatty acid supplementation in the treatment of NAFLD, but the results showed significant heterogeneity, which might be related to the dosage and durations of the trials. The dosages ranged from 1,000 to 4,000 mg, and the durations were from 8 to 24 weeks (51–53), which was in agreement with the result of another review (64). Therefore, additional trials are needed to demonstrate the effectiveness of fatty acids in NAFLD patients.

The effect of vitamin D may be related to reduced inflammatory markers (65), while whole grain could change intestinal microbial metabolites (66, 67). There were only a few articles on vitamin D and whole grain in this study because several interventions combined physical exercise with other supplements had to be excluded. At present, vitamin D combined with other treatments has been proven as an adjunctive therapy to improve liver function for NAFLD patients (68, 69). However, the articles on whole grain were scarce; therefore, larger sample size studies will be needed to provide evidence for the use of the low-cost whole grain.

This review has several limitations. Although our study showed that functional food and dietary supplements improved AST and ALT in patients with NAFLD, the source of all heterogeneity could not be explained by the subgroup analysis, especially most of the studies did not identify the stage of NAFLD and the included subjects in some studies were from a single ethnicity- mainly from Asia. Moreover, functional foods and dietary supplements used in these articles were produced in different countries with various dosages, which might have an impact on the results. Multi-center clinical research from different countries should be carried out to explore effective doses using uniform sources of functional foods and dietary supplements in the clinic. In addition, we only searched studies published in English in databases such as PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Cochrane library, and Embase. Thus, additional relevant studies might exist, and additional reviews may be required.

5. Conclusion

The current study suggests that antioxidant and probiotic/symbiotic/prebiotic supplements alone or in combination with other therapies may be a promising regimen for NAFLD patients. However, the usage of fatty acids, vitamin D, and whole grain in clinical treatment is uncertain. Further exploration of the efficacy ranks of functional foods and dietary supplements is needed to provide a reliable basis for clinical application.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

H-hY and L-lW conceived, designed the study, searched databases, screened articles, extracted data, and performed statistical analyses. P-hZ contributed to the revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY22H160002).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank TopEdit (www.topeditsci.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1014010/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ASQ, acoustic structure quantification; AST, aspartate transaminase; BMI, body mass index; CI, Confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; FBS, fasting blood sugar; GGT, glutamyltransferase; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HOMA–IR, homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MAFLD, metabolic-associated fatty liver disease; MD, mean differences; NAFLD, Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acid; QUICKI, quantitative insulin sensitivity check index; RCTs, Randomized controlled trials; RoB2, Risk of Bias Tool; SPB-201, powdered-water extract of Artemisia annua; TC, total cholesterol; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; TG, triacylglyceride; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist to height ratio.

References

1.

EslamMNewsomePNSarinSKAnsteeQMTargherGRomero-GomezMet al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. (2020) 73:202–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.045

2.

GibsonPSLangSDhawanAFitzpatrickEBlumfieldMLTrubyHet al. Systematic review: nutrition and physical activity in the management of paediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2017) 65:141–9. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001624

3.

MaJZhouQLiH. Gut microbiota and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: insights on mechanisms and therapy. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1–21. 10.3390/nu9101124

4.

MarchesiniGBugianesiEBurraPMarraFMieleLAlisiA. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults 2021: a clinical practice guideline of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver (AISF), the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and the Italian Society of Obesity (SIO). Digest Liver Dis. (2022) 54:170–82. 10.1016/j.dld.2021.04.029

5.

YounossiZMKoenigABAbdelatifDFazelYHenryLWymerM. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. (2016) 64:73–84. 10.1002/hep.28431

6.

Chinese Medical Association Fatty Liver Expert Committee. Guidelines of prevention and treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a 2018 update. Infect Dis Info. (2018) 31:393–706. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2018.03.008

7.

WuYZhengQZouBYeo YH LiXLiJet al. The epidemiology of NAFLD in mainland china with analysis by adjusted gross regional domestic product: a meta-analysis. Hepatol Int. (2020) 14:259–69. 10.1007/s12072-020-10023-3

8.

CotterTGRinellaM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 2020: the state of the disease. Gastroenterology. (2020) 158:1851–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.052

9.

European European Association for the Study of the Liver European European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetologia. (2016) 59:1121–40. 10.1007/s00125-016-3902-y

10.

ZouTTZhangCZhouYFHanYJXiongJJWuXXet al. Lifestyle interventions for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2018) 30:747–55. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001135

11.

KatsagoniCNGeorgoulisMPapatheodoridisGVPanagiotakosDBKontogianniMD. Effects of lifestyle interventions on clinical characteristics of patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. Metabolism. (2017) 68:119–32. 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.12.006

12.

HrncirTHrncirovaLKverkaMHromadkaRMachovaVTrckovaEet al. Gut microbiota and nafld: Pathogenetic mechanisms, microbiota signatures, and therapeutic interventions. Microorganisms. (2021) 9:1–18. 10.3390/microorganisms9050957

13.

Aron-WisnewskyJWarmbrunnMVNieuwdorpMClementK. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: modulating gut microbiota to improve severity?Gastroenterology. (2020) 158:1881–98. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.049

14.

Aron-WisnewskyJVigliottiCWitjesJLePHolleboomAGVerheijJet al. Gut microbiota and human nafld: Disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 17:279–97. 10.1038/s41575-020-0269-9

15.

LeungCRiveraLFurnessJBAngusPW. The role of the gut microbiota in NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2016) 13:412–25. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.85

16.

KhanMYMihaliABRawalaMSAslamASiddiquiWJ. The promising role of probiotic and synbiotic therapy in aminotransferase levels and inflammatory markers in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 31:703–15. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001371

17.

AminHLAgahSMousaviSNHosseiniAFShidfarF. Regression of non-alcoholic fatty liver by vitamin d supplement: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Arch Iran Med. (2016) 19:631–8. Available online at: www.aimjournal.ir/Article/1053

18.

KomolafeOBuzzettiELindenABestLMJMaddenAMRobertsDet al. Nutritional supplementation for nonalcohol-related fatty liver disease: a network meta-analysis. Cochr Database Syst Rev. (2021) 7:1–366. 10.1002/14651858.CD013157.pub2

19.

CiceroAFGCollettiABellentaniS. Nutraceutical approach to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (nafld): the available clinical evidence. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1–18. 10.3390/nu10091153

20.

SoleimaniDPaknahadZRouhaniMH. Therapeutic effects of garlic on hepatic steatosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Metabolic Syndr Obes Targets Therapy. (2020) 13:2389–97. 10.2147/DMSO.S254555

21.

DarandMDarabiZYariZSaadatiSHedayatiMKhonchehAet al. Nigella sativa and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Comp Ther Med. (2019) 44:204–9. 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.04.014

22.

KazemiSShidfarFEhsaniSAdibiPJananiL. Eslami O. The effects of sumac (Rhus coriarial) powder supplementation in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled trial. Comp Ther Clin Pract. (2020) 41:101259. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101259

23.

SangouniAAAzarMRMHAlizadehM. Effect of garlic powder supplementation on hepatic steatosis, liver enzymes and lipid profile in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind randomised controlled clinical trial. Br J Nutr. (2020) 124:450–6. 10.1017/S0007114520001403

24.

SabirUIrfanHMUmerINiaziZRAsjadHMM. Phytochemicals targeting nafld through modulating the dual function of forkhead box o1 (foxo1) transcription factor signaling pathways Naunyn Schmiedebergs. Arch Pharmacol. (2022) 395:741–55. 10.1007/s00210-022-02234-2

25.

EkhlasiGShidfarFAgahSMeratSHosseiniAF. Effects of pomegranate and orange juice on antioxidant status in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Vitamin Nutr Res. (2015) 85:292–8. 10.1024/0300-9831/a000292

26.

HigginsJTDeeksJAltmanDG. Special topics in statistics. In: Higgins JT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (Updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration (2011). Available online at: www.handbook.cochrane.org (accessed December 19, 2022).

27.

SavovicJTurnerRMMawdsleyDJonesHEBeynonRHigginsJPTet al. Association between risk-of-bias assessments and results of randomized trials in cochrane reviews: the robes meta-epidemiologic study. Am J Epidemiol. (2018) 187:1113–22. 10.1093/aje/kwx344

28.

MichaelisRTangVWagnerJLModiACLaFranceWC.Jr.GoldsteinLHet al. Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of psychological treatments for people with epilepsy on health-related quality of life. Epilepsia. (2018) 59:315–32. 10.1111/epi.13989

29.

SuzanneRSharptonBMEmilyH-T. Gut microbiome–targeted therapies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Clin Nutr. (2019) 110:139–49. 10.1093/ajcn/nqz042

30.

PezeshkiASafiSFeiziAAskariGKaramiF. The effect of green tea extract supplementation on liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Prev Med. (2015) 7:1–6. 10.4103/2008-7802.173051

31.

HanBKimS-MNamGEKimS-HParkS-JParkY-Ket al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centered clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of artemisia annua l. Extract for improvement of liver function. Clin Nutr Res. (2020) 9:258–70. 10.7762/cnr.2020.9.4.258

32.

SoleimaniDRezaieMRajabzadehFGholizadeh NavashenaqJAbbaspourMMiryanMet al. Protective effects of propolis on hepatic steatosis and fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) evaluated by real-time two-dimensional shear wave elastography: a randomized clinical trial. Phytotherapy Res. (2021) 35:1669–79. 10.1002/ptr.6937

33.

AskariFRashidkhaniBHekmatdoostA. Cinnamon may have therapeutic benefits on lipid profile, liver enzymes, insulin resistance, and high-sensitivity c-reactive protein in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Nutr Res. (2014) 34:143–8. 10.1016/j.nutres.2013.11.005

34.

IzadiFFarrokhzadATamizifarBTarrahiMJEntezariMH. Effect of sour tea supplementation on liver enzymes, lipid profile, blood pressure, and antioxidant status in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. Phytother Res. (2021) 35:477–85. 10.1002/ptr.6826

35.

BaeJCLeeWYYoonKHParkJYSonHSHanKA. Improvement of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with carnitine-orotate complex in type 2 diabetes (corona) a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. (2015) 38:1245–52. 10.2337/dc14-2852

36.

HosseinikiaMOubariFHosseinkiaRTabeshfarZSalehiMGMousavianZet al. Quercetin supplementation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutr Food Sci. (2020) 50:1279–93. 10.1108/NFS-10-2019-0321

37.

Mohammad ShahiMAli JavanmardiMSaeed SeyedianSHossein HaghighizadehM. Effects of phytosterol supplementation on serum levels of lipid profiles, liver enzymes, inflammatory markers, adiponectin, and leptin in patients affected by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr. (2018) 37:651–8. 10.1080/07315724.2018.1466739

38.

ZhangPWChen FX LiDLingWHGuoHH. A consort-compliant, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial of purified anthocyanin in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medicine. (2015) 94:e758. 10.1097/MD.0000000000000758

39.

NavekarRRafrafMGhaffariAAsghari-JafarabadiMKhoshbatenM. Turmeric supplementation improves serum glucose indices and leptin levels in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver diseases. J Am Coll Nutr. (2017) 36:261–7. 10.1080/07315724.2016.1267597

40.

CiceroAFGSahebkarAFogacciFBoveMGiovanniniMBorghiC. Effects of phytosomal curcumin on anthropometric parameters, insulin resistance, cortisolemia and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease indices: a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur J Nutr. (2020) 59:477–83. 10.1007/s00394-019-01916-7

41.

NamkhahZNaeiniFMahdi RezayatSMehdiYMansouriSJavad Hosseinzadeh-AttarM. Does naringenin supplementation improve lipid profile, severity of hepatic steatosis and probability of liver fibrosis in overweight/obese patients with NAFLD? A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Int J Clin Pract. (2021) 75:e14852. 10.1111/ijcp.14852

42.

AllerRDe LuisDAIzaolaOCondeRGonzalez SagradoMPrimoDet al. Effect of a probiotic on liver aminotransferases in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients: a double blind randomized clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2011) 15:1090–5. Available online at: https://web.p.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=b2e2ef50-a141-459c-8598-bded15c98bbb%40redis

43.

AsgharianAAskariGEsmailzadeAFeiziAMohammadiV. The effect of symbiotic supplementation on liver enzymes, c-reactive protein and ultrasound findings in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. (2016) 7:1–6. 10.4103/2008-7802.178533

44.

ScorlettiEAfolabiPRMilesEASmithDEAlmehmadiAAlshathryAet al. Synbiotics alter fecal microbiomes, but not liver fat or fibrosis, in a randomized trial of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. (2020) 158:1597–610.e1597. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.031

45.

Mohamad NorMHAyobNMokhtarNMRaja AliRATanGCWongZet al. The effect of probiotics (MCP (®) BCMC (®) strains) on hepatic steatosis, small intestinal mucosal immune function, and intestinal barrier in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1–17. 10.3390/nu13093192

46.

AhnSBJunDWKangBKLimJHLimSChungMJ. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a multispecies probiotic mixture in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:5688. 10.1038/s41598-019-42059-3

47.

ChongPLLaightDAspinallRJHigginsonACummingsMHA. randomised placebo controlled trial of VSL#3(®) probiotic on biomarkers of cardiovascular risk and liver injury in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. (2021) 21:144. 10.1186/s12876-021-01660-5

48.

JafarvandEFarhangiMAAlipourBKhoshbatenM. Effects of coenzyme q10 supplementation on the anthropometric variables, lipid profiles and liver enzymes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. (2016) 11:35–42. 10.3329/bjp.v11i1.24513

49.

FarsiFMohammadshahiMAlavinejadPRezazadehAZareiMEngaliKA. Functions of coenzyme q10 supplementation on liver enzymes, markers of systemic inflammation, and adipokines in patients affected by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr. (2016) 35:346–53. 10.1080/07315724.2015.1021057

50.

FarhangiMAAlipourBJafarvandEKhoshbatenM. Oral coenzyme q10 supplementation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: effects on serum vaspin, chemerin, pentraxin 3, insulin resistance and oxidative stress. Arch Med Res. (2014) 45:589–95. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.11.001

51.

RashidmayvanMMohammadshahiMSeyedianSSHaghighizadehMH. The effect of nigella sativa oil on serum levels of inflammatory markers, liver enzymes, lipid profile, insulin and fasting blood sugar in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. J Diabetes Metab Disord. (2019) 18:453–9. 10.1007/s40200-019-00439-6

52.

CansançãoKCitelliMCarvalho LeiteNLópez de Las HazasMCDávalosATavares do CarmoMDGet al. Impact of long-term supplementation with fish oil in individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a double blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1–12. 10.3390/nu12113372

53.

ScorlettiEBhatiaLMcCormickKGCloughGFNashKHodsonLet al. Effects of purified eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Results from the welcome* study. Hepatology. (2014) 60:1211–21. 10.1002/hep.27289

54.

BarchettaIDel BenMAngelicoFDi MartinoMFraioliALa TorreGet al. No effects of oral vitamin d supplementation on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Med. (2016) 14:92. 10.1186/s12916-016-0638-y

55.

MasoumehDJafary HeidarlooAFarnushBMohammadA. Whole-grain consumption and its effects on hepatic steatosis and liver enzymes in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Br J Nutr. (2020) 123:328–36. 10.1017/S0007114519002769

56.

Al-JiffriOAl-SharifFMAbd El-KaderSMAshmawyEM. Weight reduction improves markers of hepatic function and insulin resistance in type-2 diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. Afr Health Sci. (2013) 13:667–72. 10.4314/ahs.v13i3.21

57.

SanaRSangamRAdityaUArchanaRohitA. Current treatment paradigms and emerging therapies for NAFLD/NASH. Front Biosci. (2021) 26:206–37. 10.2741/4892

58.

RivesCFougeratAEllero-SimatosSLoiseauNGuillouHGamet-PayrastreLet al. Oxidative stress in NAFLD: role of nutrients and food contaminants. Biomolecules. (2020) 10:1702. 10.3390/biom10121702

59.

RobertRIanJNShizuyaYIrisSJaapSPaoloMet al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2020) 16:177–89. 10.1038/s41574-019-0310-7

60.

MillarCLDuclosQBlessoCN. Effects of dietary flavonoids on reverse cholesterol transport, HDL metabolism, and HDL function. Adv Nutr. (2017) 8:226–39. 10.3945/an.116.014050

61.

FarhangiMAVajdiMFathollahiP. Dietary total antioxidant capacity (TAC), general and central obesity indices and serum lipids among adults: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. (2022) 92:460–22. 10.1024/0300-9831/a000675

62.

AmirHHamedMMaryamMEhsanG. Efficacy of synbiotic supplementation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials: synbiotic supplementation and NAFLD. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2019) 59:2494–505. 10.1080/10408398.2018.1458021

63.

LomanBRHernandez-SaavedraDAnRRectorRS. Prebiotic and probiotic treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. (2018) 76:822–39. 10.1093/nutrit/nuy031

64.

ParkerHMJohnsonNABurdonCACohnJSO'ConnorHTGeorgeJ. Omega-3 supplementation and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. (2012) 56:944–51. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.08.018

65.

BjelakovicMNikolovaDBjelakovicGGluudC. Vitamin d supplementation for chronic liver diseases in adults. Cochr Database Syst Rev. (2021) 8:Cd011564. 10.1002/14651858.CD011564.pub3

66.

TovarJNilssonAJohanssonMBjörckI. Combining functional features of whole-grain barley and legumes for dietary reduction of cardiometabolic risk: a randomised cross-over intervention in mature women. Br J Nutr. (2014) 111:706–14. 10.1017/S000711451300305X

67.

AngelinoDMartinaARosiAVeronesiLAntoniniMMennellaIet al. Glucose- and lipid-related biomarkers are affected in healthy obese or hyperglycemic adults consuming a whole-grain pasta enriched in prebiotics and probiotics: a 12-week randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. (2019) 149:1714–23. 10.1093/jn/nxz071

68.

GuoXFWangCYangTLiSLi KL LiD. Vitamin D and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Funct. (2020) 11:7389–99. 10.1039/D0FO01095B

69.

SharifiNAmaniRHajianiECheraghianB. Does vitamin d improve liver enzymes, oxidative stress, and inflammatory biomarkers in adults with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? A randomized clinical trial. Endocrine. (2014) 47:70–80. 10.1007/s12020-014-0336-5

Summary

Keywords

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, antioxidants, phytonutrients, probiotics, symbiotics, prebiotics

Citation

Wang L-l, Zhang P-h and Yan H-h (2023) Functional foods and dietary supplements in the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Nutr. 10:1014010. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1014010

Received

08 August 2022

Accepted

30 January 2023

Published

14 February 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

Azizah Ugusman, National University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Reviewed by

Jozaa Z. ALTamimi, Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University, Saudi Arabia; Feilong Guo, Nanjing General Hospital of Nanjing Military Command, China; Mahdieh Khodarahmi, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Wang, Zhang and Yan.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui-hui Yan ✉ yandoublehui@zju.edu.cnPian-hong Zhang ✉ zrlcyyzx@zju.edu.cn

This article was submitted to Clinical Nutrition, a section of the journal Frontiers in Nutrition

†ORCID: Lei-lei Wang orcid.org/0000-0002-3714-2892

Pian-hong Zhang orcid.org/0000-0002-0525-1701

Hui-hui Yan orcid.org/0000-0001-7992-3358

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.