Abstract

Background:

Ascorbic acid or vitamin C has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may impact markers of inflammation like C-reactive protein (CRP). However, studies specifically on vitamin C and high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) have been scarce.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–2018 dataset including 5,380 U.S. adults aged ≥20 years. Multiple regression models examined the relationship between plasma vitamin C and serum hs-CRP while adjusting for potential confounders. Stratified analyses and curve fitting assessed effect modification and nonlinearity.

Results:

An inverse association was found between plasma vitamin C and serum hs-CRP overall (β = −0.025, 95% CI: −0.033 to −0.017, p < 0.00001) and in subgroups except for the “other Hispanic” subgroup in model II (β = −0.009, 95% CI: (−0.040, 0.023), p = 0.5885). The relationship was nonlinear, with the greatest hs-CRP reduction observed up to a plasma vitamin C level of 53.1 μmol/L.

Conclusion:

The results showed a non-linear negative correlation between vitamin C levels and hs-CRP in adults. These results suggest vitamin C intake may reduce inflammation and cardiovascular risk, but only up to 53.1 μmol/L plasma vitamin C.

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in exploring the possible influence of nutrition on inflammation and its related markers. Vitamin C, another name for ascorbic acid, is an essential micronutrient that participates in various biological processes. Vitamin C has immuno-enhancing and anti-inflammatory properties (1, 2), improving immune cell activity and trafficking while dampening overactive immune responses (3, 4). Additionally, vitamin C confers multiple benefits, such as facilitating collagen synthesis (5, 6), and modulating epigenetic processes (7, 8) highlighting its significance in maintaining overall health.

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a highly accurate indicator of widespread inflammation generated by the liver as an acute-phase reactant (9, 10). High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) assay can measure lower levels of CRP in the blood and is a reliable predictor of cardiovascular disease risk (11–14). hs-CRP reflects the degree of systemic inflammation caused by various inflammatory stimuli, such as cytokines and oxidative stress (15). hs-CRP can also activate endothelial cells and stimulate the production of adhesion molecules and pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are important in the progression of atherosclerosis (16–18). Elevated hs-CRP levels are linked to an elevated risk of events associated with cardiovascular disease, such as myocardial infarction (19, 20), stroke recurrence (21, 22), and mortality (23, 24).

Previous research has discovered an inverse relationship between vitamin C status and CRP (25, 26). However, investigations specifically focusing on the relationship between vitamin C and hs-CRP, a more accurate diagnostic marker, have been limited.

To address this research gap, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 2017–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) involving a large and diverse sample of US adults. The NHANES is a nationally representative study that collects comprehensive data regarding the health, nutritional status, and lifestyle of individuals in the United States. By rigorously considering various confounding factors and conducting subgroup analyses, our study aimed to develop a more nuanced comprehension of the possible connections between vitamin C and hs-CRP. Through accounting for potential effect modifiers and sources of heterogeneity, we sought to contribute valuable insights into the interplay between vitamin C and inflammation markers, shedding light on its potential implications for overall health and disease prevention.

Methods

Study design

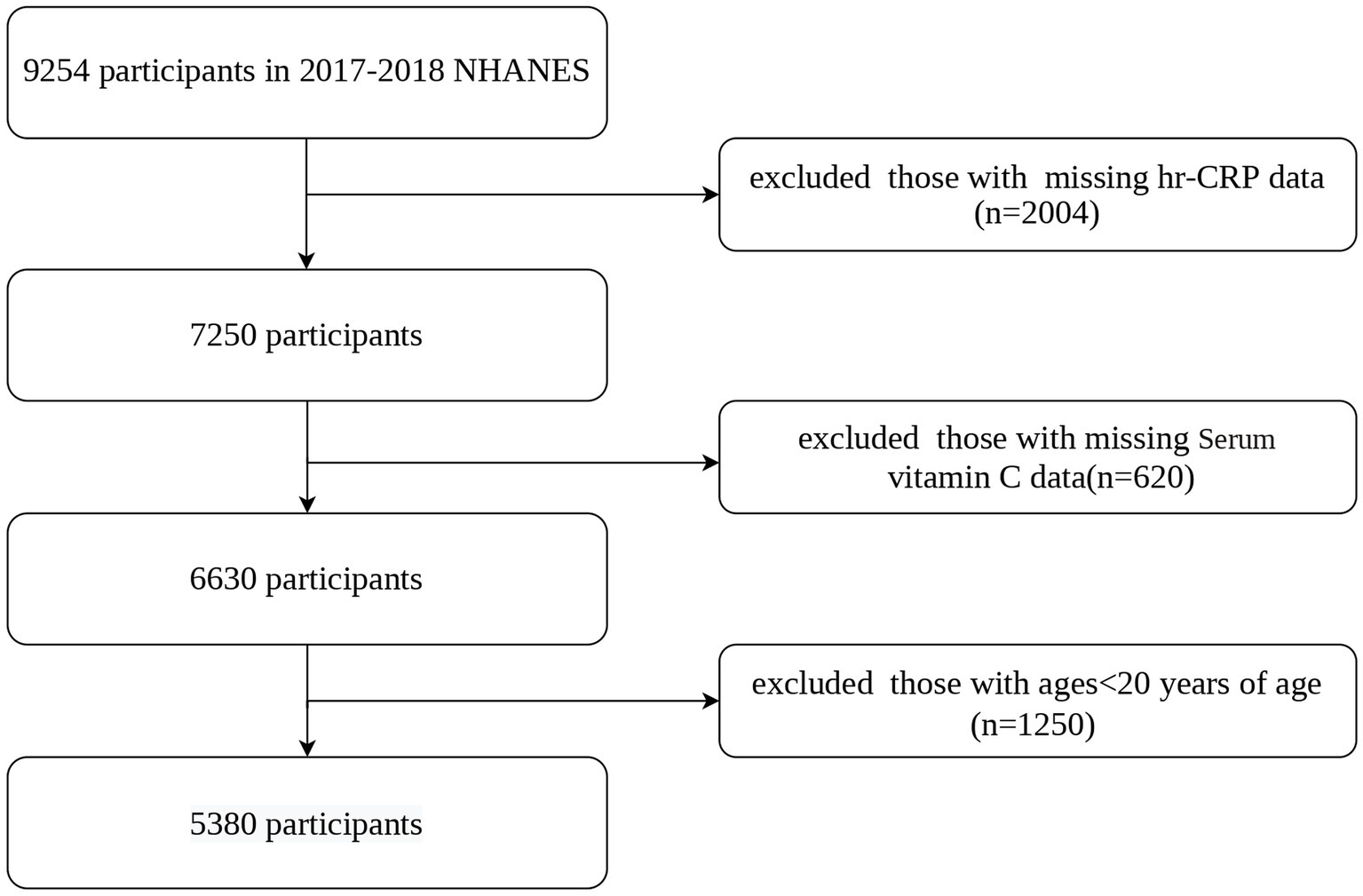

This cross-sectional research examined NHANES 2017–2018 data. The NCHS Research Ethics Review Board approved the procedure (Protocol #2011–17, Protocol #2018–01). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention got written and informed permission from all participants. We included participants aged 20 years and older who had complete data for serum vitamin C and hs-CRP levels, 5,380 adults aged ≥20 years were included out of 9,254 initial participants. Figure 1 illustrates the detailed screening process.

Figure 1

Flowchart of participants selection. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein.

Measurement of serum vitamin C and hs-CRP

Serum vitamin C was obtained and measured using isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection at 650 mV. A standard curve of three concentrations (0.025, 0.150, and 0.500 mg/dL) of an external standard was used for quantification. The NHANES reliability assurance and quality control processes satisfied the standards of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Act of 1988. Serum vitamin C levels were analyzed continuously and categorically according to a prior study (27, 28): deficiency (0–10.99 μmol/L), hypovitaminosis (11–23.99 μmol/L), inadequate (24–49.99 μmol/L), adequate (50–69.99 μmol/L), and saturating (≥70 μmol/L).

Hs-CRP was quantified using a high-sensitivity near-infrared particle immunoassay method in Mobile Examination Centers (CDC-NHANES, 2019). hs-CRP was reported in mg/dL.

Covariates

This study included a variety of covariates: demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, and household income-to-poverty ratio), chronic diseases (hypertension and diabetes), lifestyle behaviors (physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption), examination data (BMI), supplement use, food security and dietary inflammatory index (DII).

The demographic characteristics were categorical variables, such as: sex (male or female); race (Non-Hispanic Black, Other Race – Including Multi-Racial, Non-Hispanic White, Mexican American, or Other Hispanic); and family income-to-poverty ratio (<=1.5, >1.5, <=4.5, >4.5 or Not Recorded).

Chronic illnesses were evaluated using self-reported medical histories. Hypertension has been characterized as having any or all of the following criteria: (1) current usage of antihypertensive medication; (2) previous diagnosis of hypertension by a physician; (3) an average systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher based on four measurements; or (4) a diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher. Diabetes was categorized as “yes”, “no”, “borderline”, and “Not Recorded” based on the following criteria: (1) doctor’s diagnosis of diabetes; (2) current use of hypoglycemic medication; (3) fasting blood glucose of 7.0 mmoL/L or higher; (4) glycated hemoglobin of 6.5% or higher; (5) two-hour oral glucose tolerance test blood glucose of 11.1 mmoL/L or higher; and (6) random blood glucose of 11.1 mmoL/L or higher. Physical activity was classified as “yes”, “no”, and “Not Recorded” based on the World Health Organization guidelines of more than 599 MET minutes/week. Smoking status groups were “never smokers” (less than 100 lifetime cigarettes), “former smokers”, “current smokers”, and “Not Recorded”. Alcohol consumption categories were drinkers, non-drinkers, and Not Recorded based on the past 12 month intake frequency. Food security was evaluated based on the answer to the question, “Are you worried you will run out of food?” It was categorized as “yes”, “no”, or “not recorded”. Supplement use was examined based on the reply to the question. “Any Dietary Supplements Taken?” It was recorded as “Yes”, “No”, or “Not Recorded”. Weight and height measurements were used to determine the body mass index (BMI).

The DII assesses the inflammatory impacts of dietary consumption based on 45 specific nutrients. Each component’s score is determined by calculating the deviation from the global daily mean intake, dividing it by the standard deviation, and converting the resulting Z score to a percentile score. After doubling the percentile score and subtracting it by 1 for a symmetrical distribution, the percentile value is multiplied by the corresponding “overall inflammation effect score” for that nutrient. Summing up all individual DII scores yields the “overall DII score” for each participant. Our study computed the DII score using 28 nutrients, including alcohol, vitamin B12/B6, β-carotene, caffeine, carbohydrate, cholesterol, energy, total fat, fiber, folic acid, iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), niacin, n-3 fatty acids, n-6 fatty acids, protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), riboflavin, saturated fat, selenium (Se), thiamin, vitamins A/C/D/E, and zinc (Zn).

Statistical analysis

Weighted data from NHANES 2017–2018 were produced in compliance with analytical criteria. Vitamin C was assessed using both quintiles and continuous variables. Linear regression models were applied to investigate the connection between vitamin C and hs-CRP. Three different models were built: crude Model was unadjusted; Model I was adjusted for sex, age, and race; and Model II was adjusted for all covariates (sex, age, race, poverty income ratio level, body mass index, food security, supplement use, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol consumption and dietary inflammatory index). Stratified analysis and smooth curve fitting have been applied to further investigate the association between vitamin C and hs-CRP. To determine the independent impacts of Vitamin C on hs-CRP, univariate and stratified analyses were performed. Continuous data are shown as means and standard errors, and categorical variables are shown as percentages. Effect estimates are reported as β coefficients with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. A 0.05 or lower p-value was considered statistically significant. Missing values for BMI were replaced with the mean value, and missing categorical data were analyzed as a single group in the analysis. The entire data analysis had been utilized using R (version 4.2.0; http://www.r-project.org) and Empower Stats (http://www.empowerstats.com; X&Y Solutions Inc.).

Result

We analyzed the data of 5,380 participants from the NHANES 2017–2018. Table 1 presents the weighted characteristics that distinguish the study population according to plasma vitamin C quintiles (range < 11 to > = 70 μmol/L). All the variables showed significant linear trends across the vitamin C quintiles (p < 0.05). The prevalence of hypertension decreased from 45.6% in the lowest vitamin C quintile (<11 μmol/L) to 35.6% in the highest vitamin C quintile (> = 70 μmol/L) (P for trend <0.0001). The mean BMI also decreased from 30.6 ± 8.4 kg/m2 in the lowest vitamin C quintile to 26.7 ± 7.0 kg/m2 in the highest vitamin C quintile (P for trend <0.0001). The proportion of females increased from 46.5% in the lowest vitamin C quintile to 67.7% in the highest vitamin C quintile (P for trend <0.0001). Supplement use increased from 25.0% in the lowest vitamin C quintile to 77.8% in the highest vitamin C quintile (P for trend <0.0001). Never smokers increased from 34.5% in the lowest vitamin C quintile to 57.5% in the highest vitamin C quintile (P for trend <0.0001). We stratified vitamin C and hs-CRP data by vitamin C levels, and Supplementary Table S1 shows a univariate analysis of the relationship between variables and hs-CRP.

Table 1

| Vitamin C categories (μmol/L) | <11 | > = 11, <24 | > = 24, <50 | > = 50, <70 | > = 70 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean + SD (years) | 48.812 ± 16.894 | 45.144 ± 16.664 | 46.334 ± 17.415 | 45.746 ± 18.489 | 47.106 ± 22.721 | 0.01742 |

| BMI mean + SD (kg/m2) | 30.599 ± 8.414 | 32.072 ± 8.303 | 30.524 ± 7.505 | 28.642 ± 6.688 | 26.731 ± 6.995 | <0.00001 |

| hs-CRP mean + SD (mg/L) | 5.808 ± 10.424 | 5.042 ± 9.525 | 4.491 ± 9.643 | 3.046 ± 5.030 | 2.776 ± 4.853 | <0.00001 |

| DII | 2.470 ± 1.593 | 2.148 ± 1.507 | 1.591 ± 1.752 | 1.167 ± 1.850 | 1.262 ± 1.852 | <0.00001 |

| Sex (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| Female | 46.503 | 41.351 | 46.041 | 48.019 | 67.731 | |

| Male | 53.497 | 58.649 | 53.959 | 51.981 | 32.269 | |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 9.342 | 10.889 | 13.634 | 10.528 | 8.413 | |

| Other Race- including multi-racial | 8.991 | 8.924 | 12.231 | 11.309 | 8.794 | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 72.203 | 69.231 | 52.828 | 60.502 | 68.352 | |

| Mexican American | 5.197 | 6.804 | 12.211 | 10.279 | 7.931 | |

| Other Hispanic | 4.266 | 4.152 | 9.096 | 7.382 | 6.510 | |

| Supplement use (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| Yes | 24.981 | 34.273 | 51.871 | 60.009 | 77.837 | |

| No | 75.019 | 65.661 | 48.079 | 39.964 | 22.130 | |

| Not Recorded | 0.000 | 0.066 | 0.050 | 0.027 | 0.032 | |

| Food insecure (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| No | 63.586 | 70.348 | 70.117 | 75.949 | 75.619 | |

| Yes | 33.960 | 25.661 | 25.370 | 21.002 | 20.387 | |

| Not recorded | 2.454 | 3.991 | 4.512 | 3.049 | 3.994 | |

| Physical activity (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| No | 10.947 | 10.630 | 12.151 | 9.193 | 10.628 | |

| Yes | 60.575 | 63.582 | 65.066 | 68.905 | 58.345 | |

| Not recorded | 28.478 | 25.787 | 22.783 | 21.902 | 31.026 | |

| Family PIR (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| <=1.5 | 32.783 | 25.868 | 23.784 | 19.385 | 18.478 | |

| >1.5, <=4.5 | 36.847 | 33.032 | 37.380 | 38.408 | 40.599 | |

| >4.5 | 19.933 | 30.521 | 27.402 | 32.412 | 31.004 | |

| Not recorded | 10.437 | 10.579 | 11.435 | 9.795 | 9.919 | |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| No drinking | 8.801 | 4.663 | 6.371 | 6.065 | 7.201 | |

| Drinking | 63.286 | 73.297 | 72.774 | 70.758 | 60.548 | |

| Not recorded | 27.913 | 22.040 | 20.856 | 23.177 | 32.252 | |

| Smoking status (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| Former | 21.791 | 26.263 | 25.897 | 23.027 | 22.141 | |

| Never | 34.510 | 47.847 | 55.223 | 58.366 | 57.518 | |

| Now | 43.551 | 25.075 | 16.910 | 14.010 | 7.493 | |

| Not recorded | 0.149 | 0.815 | 1.970 | 4.597 | 12.848 | |

| Diabetes (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| No | 77.475 | 69.248 | 71.873 | 79.204 | 81.872 | |

| Borderline | 5.314 | 9.893 | 8.929 | 6.065 | 5.880 | |

| Yes | 17.211 | 19.226 | 18.471 | 13.793 | 11.333 | |

| Not recorded | 0.000 | 1.634 | 0.727 | 0.938 | 0.914 | |

| Hypertension (%) | <0.00001 | |||||

| Yes | 45.627 | 41.374 | 40.903 | 34.592 | 35.585 | |

| No | 54.373 | 58.445 | 58.250 | 63.701 | 57.672 | |

| Not recorded | 0.000 | 0.180 | 0.846 | 1.706 | 6.743 |

Weighted characteristics of the study population based on vitamin C quintiles.

Mean ± SD for continuous variables: p-value was calculated by weighted linear regression model. % for categorical variables: p-value was calculated by weighted chi-square test. BMI, body mass index; PIR, household income-to-poverty ratio; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; DII, dietary inflammatory index.

In Table 2, we carried out a multivariate regression analysis to analyze the relationship between vitamin C (μmol/L) and hs-CRP (mg/L) levels while adjusting for various covariates. The Crude Model revealed a significant negative relationship between vitamin C and hs-CRP (β = −0.034, 95% CI: −0.041 to −0.027, p < 0.00001). After adjusting for sex, age, and race/ethnicity in Model I, the negative association remained highly significant (β = −0.038, 95% CI: −0.045 to −0.031, p < 0.00001). Further adjustments for additional covariates in Model II also showed a strong negative association (β = −0.024, 95% CI: −0.032 to −0.016, p < 0.00001). Furthermore, the categorical analysis revealed that increased vitamin C levels resulted in gradually reduced hs-CRP levels, with the strongest effect observed in the highest category (> = 70 μmol/L, β = −2.383 to −3.032).

Table 2

| Variable | Crude model | Model I | Model II |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) p-value | β (95%CI) p-value | β (95%CI) p-value | |

| Vitamin C (μmol/L) | −0.034 (−0.041, −0.027) <0.00001 | −0.038 (−0.045, −0.031) <0.00001 | −0.024 (−0.032, −0.016) <0.00001 |

| Vitamin C categories (μmol/L) | |||

| <11 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| > = 11, <24 | −0.766 (−1.750, 0.219) 0.12752 | −0.619 (−1.598, 0.360) 0.21510 | −0.971 (−1.928, −0.015) 0.04663 |

| > = 24, <50 | −1.317 (−2.212, −0.422) 0.00395 | −1.316 (−2.209, −0.422) 0.00391 | −1.215 (−2.105, −0.325) 0.00747 |

| > = 50, <70 | −2.762 (−3.651, −1.873) <0.00001 | −2.742 (−3.626, −1.857) <0.00001 | −2.129 (−3.027, −1.231) <0.00001 |

| > = 70 | −3.032 (−3.935, −2.129) <0.00001 | −3.300 (−4.202, −2.399) <0.00001 | −2.383 (−3.327, −1.440) <0.00001 |

| P for trend | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Relationship between vitamin C (μmol/L) and hs-CRP (mg/L) levels in different models.

CI, confidence interval; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Crude Model no covariates were adjusted. Model I adjusted for sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Model II adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status and alcohol consumption, dietary inflammatory index.

Additionally, Table 3 displays the correlation between vitamin C levels (μmol/L) and hs-CRP levels (mg/L) in various subgroups stratified by age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. The findings demonstrate a negative connection between vitamin C and hs-CRP in all subgroups and models, except for the “other Hispanic” subgroup in model II (β = −0.007, 95% CI: (−0.038, 0.024), p = 0.6429).The strength of the negative correlation varied among subgroups, with the “other race – including multi-racial” subgroup showing the strongest correlation (β = −00.051, 95% CI: (−0.074, −0.029), p < 0.0001 in model II), and the “former smoker” subgroup showing the weakest correlation (β = −0.013, 95% CI: (−0.028, 0.002), p = 0.0791 in model II).

Table 3

| Crude Model | Model I | Model II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β (95%CI) p-value | β (95%CI) p-value | β (95%CI) p-value | |

| Subgroup analysis stratified by age | |||

| <60 | −0.035 (−0.043, −0.026) <0.0001 | −0.0369 (−0.047, −0.030) <0.0001 | −0.020 (−0.029, −0.010) <0.0001 |

| > = 60 | −0.034 (−0.046, −0.022) <0.0001 | −0.038 (−0.050, −0.027) <0.0001 | −0.029 (−0.041, −0.017) <0.0001 |

| Subgroup analysis stratified by sex | |||

| Male | −0.035 (−0.046, −0.024) <0.0001 | −0.035 (−0.046, −0.024) <0.0001 | −0.025 (−0.037, −0.014) <0.0001 |

| Female | −0.040 (−0.050, −0.031) <0.0001 | −0.041 (−0.050, −0.031) <0.0001 | −0.023 (−0.033, −0.013) <0.0001 |

| Subgroup analysis stratified by race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −0.042 (−0.066, −0.018) 0.0005 | −0.042 (−0.066, −0.018) 0.0006 | −0.027 (−0.051, −0.004) 0.0235 |

| Other race – including multi-racial | −0.062 (−0.085, −0.039) <0.0001 | −0.067 (−0.090, −0.045) <0.0001 | −0.051 (−0.074, −0.029) <0.0001 |

| Non-Hispanic White | −0.029 (−0.037, −0.021) <0.0001 | −0.035 (−0.043, −0.026) <0.0001 | −0.021 (−0.030, −0.012) <0.0001 |

| Mexican American | −0.041 (−0.069, −0.014) 0.0035 | −0.040 (−0.068, −0.013) 0.0040 | −0.025 (−0.052, 0.002) 0.0741 |

| Other Hispanic | −0.020 (−0.052, 0.012) 0.2177 | −0.026 (−0.057, 0.006) 0.1172 | −0.007 (−0.038, 0.024) 0.6429 |

| Subgroup analysis stratified by smoking status | |||

| Former | −0.016 (−0.031, −0.001) 0.0360 | −0.023 (−0.038, −0.008) 0.0029 | −0.013 (−0.028, 0.002) 0.0791 |

| Never | −0.036 (−0.046, −0.026) <0.0001 | −0.043 (−0.053, −0.033) <0.0001 | 0.027 (−0.036, −0.017) <0.0001 |

| Now | −0.039 (−0.059, −0.020) <0.0001 | −0.039 (−0.059, −0.020) <0.0001 | −0.029 (−0.048, −0.010) 0.0024 |

| Not recorded | −0.029 (−0.065, 0.007) 0.1091 | −0.031 (−0.067, 0.005) 0.0880 | −0.028 (−0.063, 0.007) 0.1196 |

| Subgroup analysis stratified by alcohol consumption | |||

| No drinking | −0.046 (−0.070, −0.021) 0.0003 | −0.053 (−0.077, −0.028) <0.0001 | −0.034 (−0.058, −0.010) 0.0059 |

| Drinking | −0.025 (−0.034, −0.016) <0.0001 | −0.032 (−0.041, −0.023) <0.0001 | −0.016 (−0.026, −0.006) 0.0011 |

| Not recorded | −0.052 (−0.065, −0.040) <0.0001 | −0.050 (−0.063, −0.037) <0.0001 | −0.035 (−0.049, −0.021) <0.0001 |

Stratified analysis of the correlation between vitamin C (μmol/L) and hs-CRP (mg/L).

CI, confidence interval; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Crude Model no covariates were adjusted. Model I adjusted for sex, age, and race/ethnicity except the subgroup variable. Model II adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status and alcohol consumption, dietary inflammatory index except the subgroup variable.

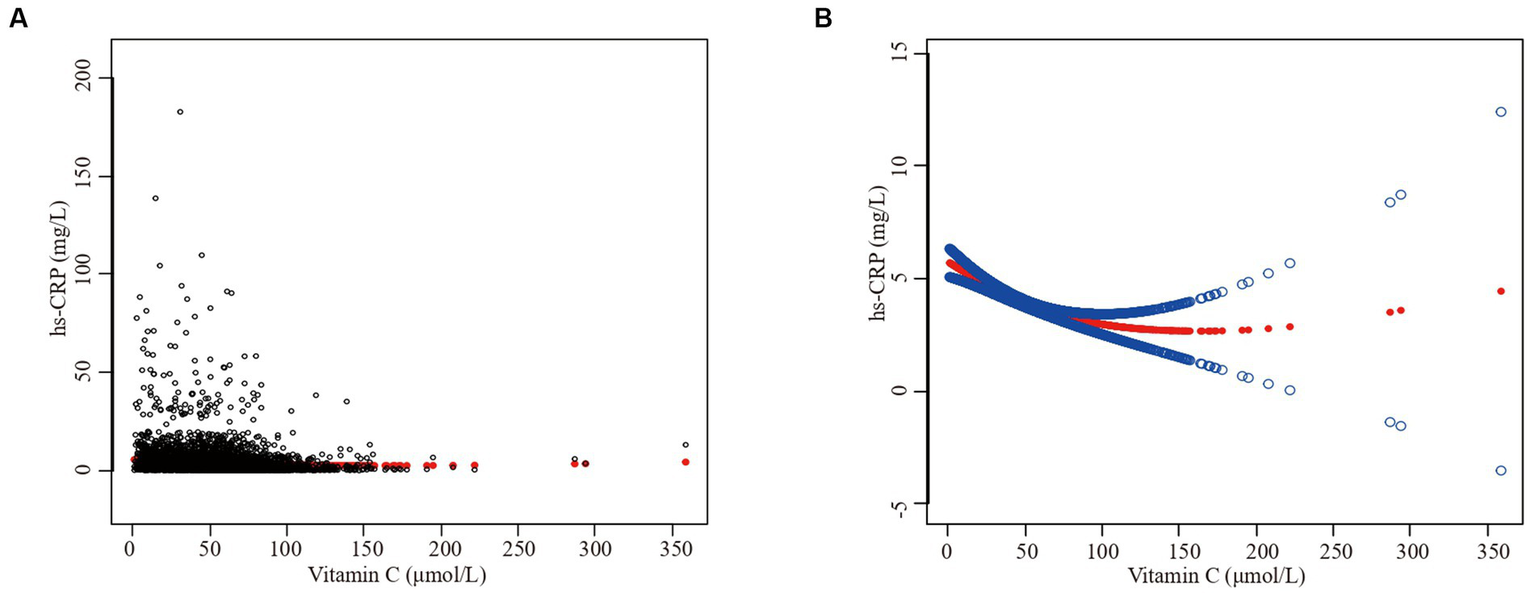

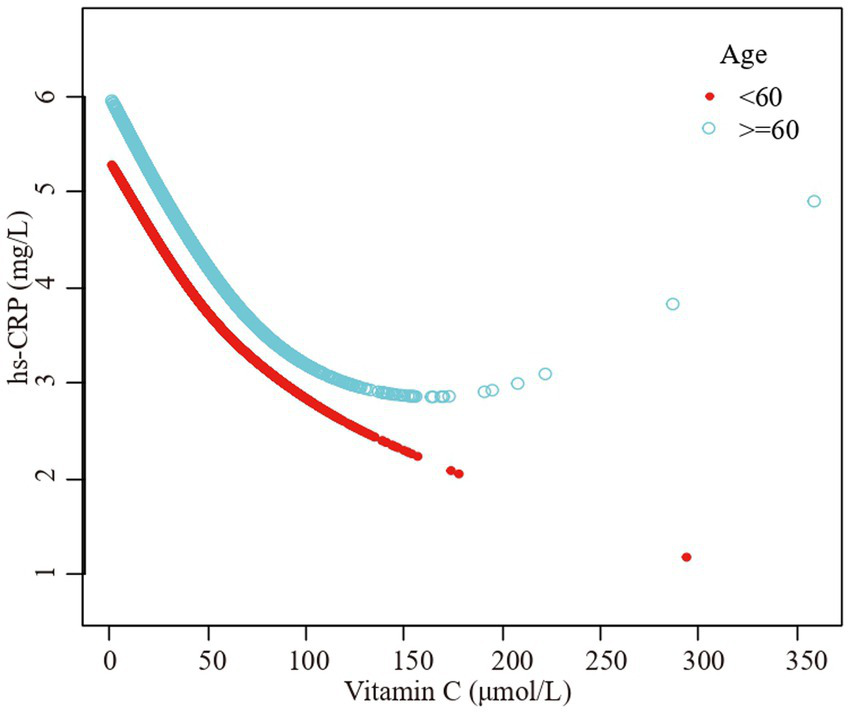

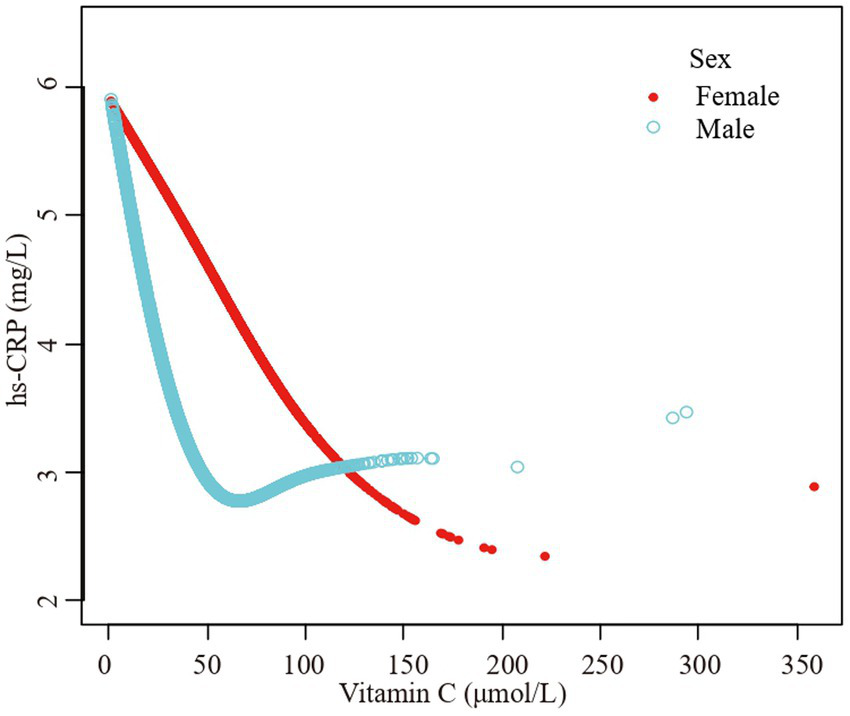

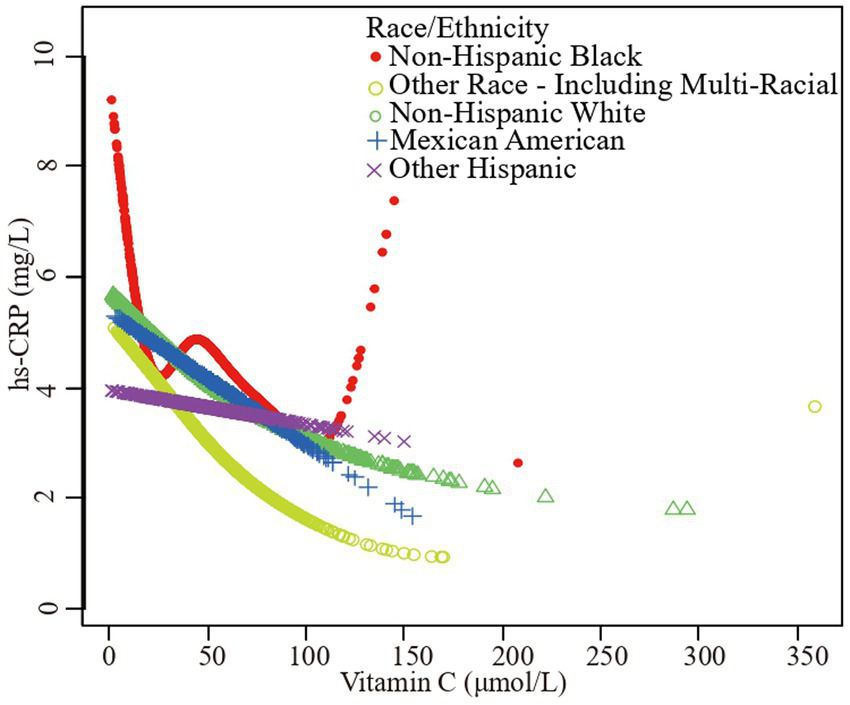

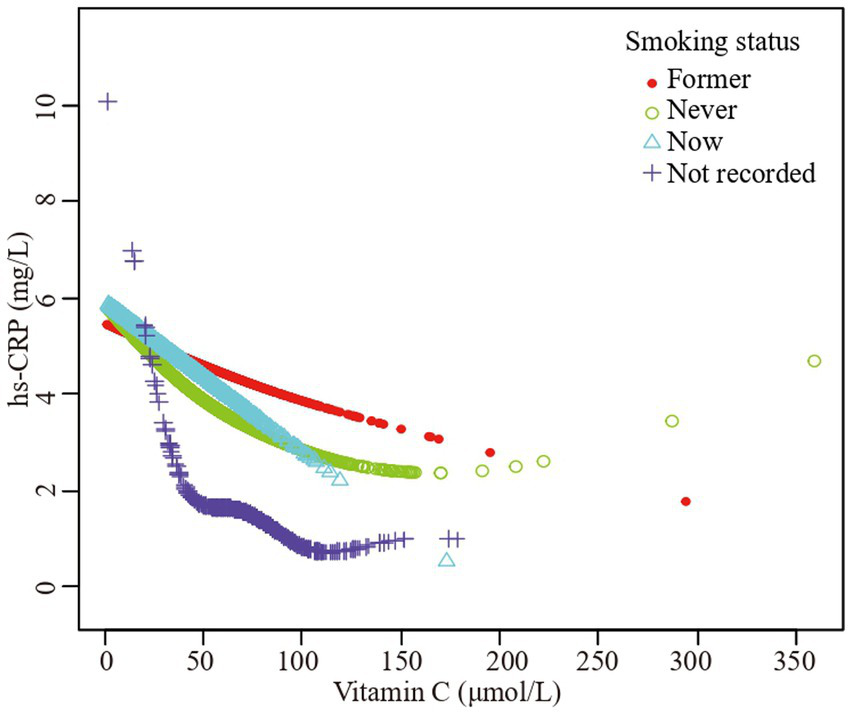

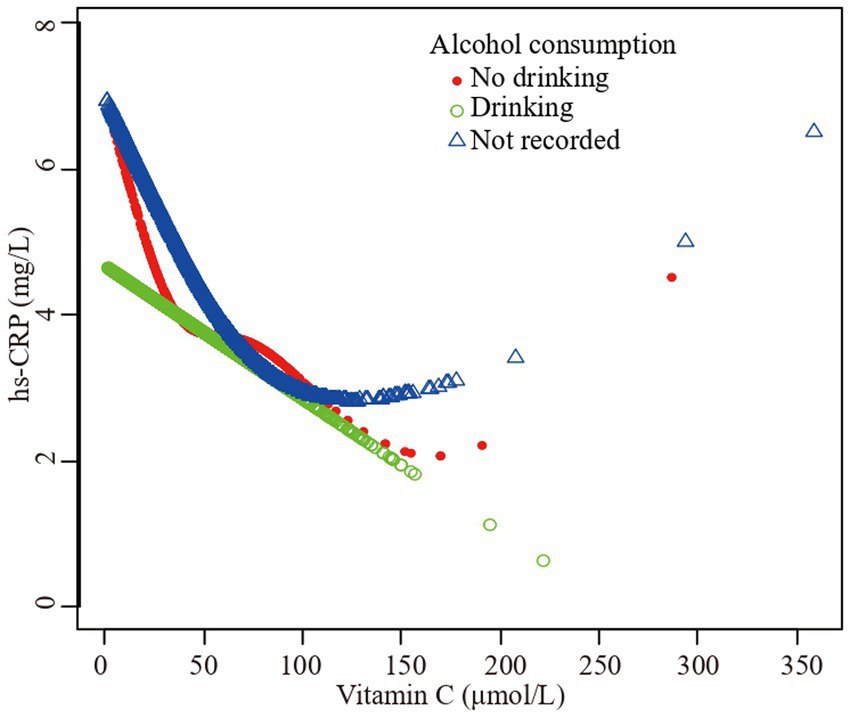

Furthermore, we employed a smooth curve fitting approach to investigate the potential nonlinear connection between vitamin C and hs-CRP, leading to consistent results, as depicted in Figures 2–7. In addition, we ran a log-likelihood ratio test and compared the one-line linear regression model to the two-segment regression model. A two-step recursive technique was used to determine the infection point, K = 53.1. The results showed an optimal level of vitamin C, approximately 53.1 μmol/L, which was associated with the most significant reduction in hs-CRP levels. The results are shown in Table 4.

Figure 2

The association between vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. (A) Each black point represents a sample. (B) Solid redline represents the smooth curve fit between variables. Blue bands represent the 95% of confidence interval from the fit. Sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status, dietary inflammatory index and alcohol consumption were adjusted.

Figure 3

The association vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein stratified by age. Sex, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status, dietary inflammatory index and alcohol consumption were adjusted.

Figure 4

The association vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein stratified by sex. Age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status, dietary inflammatory index and alcohol consumption were adjusted.

Figure 5

The association vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein stratified by race/ethnicity. Age, sex, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status, dietary inflammatory index and alcohol consumption were adjusted.

Figure 6

The association vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein stratified by smoking status. Sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, dietary inflammatory index and alcohol consumption were adjusted.

Figure 7

The association vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein stratified by alcohol consumption. Sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, dietary inflammatory index and smoking status were adjusted.

Table 4

| Models | β (95%CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Model I | ||

| One line effect | −0.017 (−0.034, 0.000) | 0.0511 |

| Model II | ||

| Infection point (K) | 53.1 | |

| Vitamin C < 53.1 (μmol/L) | −0.091 (−0.139, −0.043) | 0.0002 |

| Vitamin C > 53.1 (μmol/L) | −0.006 (−0.024, 0.012) | 0.5094 |

| P for log-likelihood ratio test | 0.001 | |

Threshold effect analysis of vitamin C (μmol/L) and hs-CRP (mg/L) using piece-wise linear regression.

Model I, one-line linear regression; Model II, two-segment regression. β was the effect size and the 95% CI indicated the confidence interval adjusted for sex, age, race/ethnicity, family poverty income ratio level, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, physical activity, food insecure, supplement use, body mass index, smoking status and alcohol consumption, dietary inflammatory index.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional investigation, we analyzed the relationship between vitamin C and hs-CRP using the NHANES 2017–2018 database. Multiple regression models, stratified analysis, and smooth curve fitting were applied to investigate the linear and nonlinear association between vitamin C and hs-CRP. The results revealed a non-linear negative correlation between vitamin C levels and hs-CRP in adults. A significant decrease of hs-CRP was observed until vitamin C reached 53.1 μmol/L.

Our findings are consistent with prior research that found a negative relationship between vitamin C and hs-CRP in different populations and settings. Lin et al. (29) found a high prevalence of low plasma vitamin C in a subtropical region, which was linked to high hs-CRP levels. Several studies found lower plasma vitamin C and higher hs-CRP levels in patients with chronic diseases such as respiratory diseases (30), hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (31) compared to healthy controls or placebo groups. Other studies reported that vitamin C supplementation or intake significantly reduced CRP levels in various subgroups such as males, non-smokers, healthy subjects, younger people, and at doses <500 mg/day (32). Some studies also found an inverse connection between CRP and vitamin C levels in special populations such as pregnant women with depression and anxiety (33) and patients with septic cardiomyopathy (34).

The inverse connection between vitamin C and hs-CRP is thought to be mediated by several potential mechanisms involving antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin C. First, as an antioxidant, vitamin C is essential for scavenging reactive oxygen species and decreasing oxidative stress, which in turn helps to reduce the inflammatory cascade (35–37). Second, vitamin C is believed to possess anti-inflammatory properties, potentially through its ability to enhance immune cell function and preserve endothelial integrity (38, 39). Third, vitamin C may contribute to the reduction of inflammation by inhibiting the apoptosis of endothelial cells and monocytes (38), both of which are associated with the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis (40).

However, research on the relationship between vitamin C and CRP levels has also shown inconsistent results. Several studies found a non-significant difference in CRP levels between vitamin C and placebo teams among sepsis patients (41, 42). A meta-analysis found no overall significant influence of vitamin C and E co-supplementation on plasma CRP levels, with varied results in different populations (43). Another study reported that 100% orange juice intake for 4 weeks significantly reduced interleukin-6 levels but had no significant effect on CRP concentrations (44). The inconsistent findings regarding vitamin C and CRP across studies may be due to differences in several factors such as study design, participants, vitamin C doses, intervention duration, and confounding factors.

Besides these factors, our research has several limitations that should be mentioned. First, the cross-sectional method makes it impossible to demonstrate causality throughout vitamin C and hs-CRP. Second, we used the NHANES database, which only represents the adult population aged 20 years old and above in the United States. Therefore, we cannot generalize our results to other age groups or populations outside of the United States. Third, the lack of detailed reporting on the standardized timing of blood collection may have influenced the measured biomarkers. Further investigation is necessary to validate and extend our findings to broader demographics and explore the underlying mechanisms between vitamin C and hs-CRP using more robust study designs. Moreover, there could be additional combined factors that were not thoroughly considered, which could impact the correlation between vitamin C and hs-CRP. Further investigation is required to validate and broaden our findings to broader demographics and explore the underlying mechanisms between vitamin C and hs-CRP using more robust study designs.

Despite these limitations, our study also has some strengths and innovations that should be highlighted. One of the strengths is that we utilized a weighted nationally representative sample comprising a diverse multiracial population, ensuring that our findings are highly representative of the entire population. Another innovation is that we added new insights by exploring the nonlinear relationship between vitamin C and hs-CRP through the implementation of smooth curve fitting. Intriguingly, our results revealed an optimal level of vitamin C, approximately 53.1 μmol/L, which was associated with the most significant reduction in hs-CRP levels. This observation suggests that a higher intake of vitamin C might be beneficial in mitigating inflammation and reducing cardiovascular risk, but only up to a certain threshold. We recommend following the current nutritional guidelines and obtaining adequate vitamin C from food sources to determine the optimal vitamin C intake, rather than relying excessively on supplements, before further research is conducted. These findings have significant implications for both public health and therapeutic practice.

Conclusion

Based on our study, we demonstrated a negative and nonlinear relationship between plasma vitamin C and hs-CRP in an overall representative sample of US adults. Our findings suggest that optimal vitamin C intake may have anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective effects, but further research is warranted to establish the causal relationship and the underlying mechanisms. We recommend increasing vitamin C intake to optimal levels for reducing inflammation and cardiovascular risk, but further research is warranted to establish the causal relationship and the underlying mechanisms.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics approved all NHANES protocols, and written informed consents were obtained from all participants or their proxies. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ND: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. ZZ: Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Investigation, Writing – original draft. KL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Changsha Natural Science Foundation (kq2208445), Changsha Central Hospital (YNKY202306).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1290749/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Mason SA Keske MA Wadley GD . Effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: a GRADE-assessed systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:618–30. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1893

2.

Patel JJ Ortiz-Reyes A Dhaliwal R Clarke J Hill A Stoppe C et al . IV vitamin C in critically ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. (2022) 50:e304–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005320

3.

Ang A Pullar JM Currie MJ Vissers MCM . Vitamin C and immune cell function in inflammation and cancer. Biochem Soc Trans. (2018) 46:1147–59. doi: 10.1042/BST20180169

4.

Bae M Kim H . Mini-review on the roles of vitamin C, vitamin D, and selenium in the immune system against COVID-19. Molecules. (2020) 25:5346. doi: 10.3390/molecules25225346

5.

Burzle M Hediger MA . Functional and physiological role of vitamin C transporters. Curr Top Membr. (2012) 70:357–75. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394316-3.00011-9

6.

DePhillipo NN Aman ZS Kennedy MI Begley JP Moatshe G LaPrade RF . Efficacy of vitamin C supplementation on collagen synthesis and oxidative stress after musculoskeletal injuries: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. (2018) 6:232596711880454. doi: 10.1177/2325967118804544

7.

Young JI Zuchner S Wang G . Regulation of the epigenome by vitamin C. Annu Rev Nutr. (2015) 35:545–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071714-034228

8.

Peters C Kouakanou L Kabelitz D . A comparative view on vitamin C effects on alphabeta- versus gammadelta T-cell activation and differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. (2020) 107:1009–22. doi: 10.1002/JLB.1MR1219-245R

9.

Du Clos TW . C-reactive protein as a regulator of autoimmunity and inflammation. Arthritis Rheum. (2003) 48:1475–7. doi: 10.1002/art.11025

10.

Ridker PM . From C-reactive protein to Interleukin-6 to Interleukin-1: moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection. Circ Res. (2016) 118:145–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306656

11.

Rifai N Ridker PM . High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: a novel and promising marker of coronary heart disease. Clin Chem. (2001) 47:403–11. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/47.3.403

12.

Ledue TB Rifai N . Preanalytic and analytic sources of variations in C-reactive protein measurement: implications for cardiovascular disease risk assessment. Clin Chem. (2003) 49:1258–71. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1258

13.

Ridker PM . High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk: rationale for screening and primary prevention. Am J Cardiol. (2003) 92:17K–22K. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00774-4

14.

Ridker PM Bhatt DL Pradhan AD Glynn RJ MacFadyen J Nissen SE et al . Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet. (2023) 401:1293–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00215-5

15.

Wu J Xia S Kalionis B Wan W Sun T . The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiovascular aging. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:615312. doi: 10.1155/2014/615312

16.

Calabro P Golia E Yeh ET . CRP and the risk of atherosclerotic events. Semin Immunopathol. (2009) 31:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0149-4

17.

Eisenhardt SU Habersberger J Murphy A Chen YC Woollard KJ Bassler N et al . Dissociation of pentameric to monomeric C-reactive protein on activated platelets localizes inflammation to atherosclerotic plaques. Circ Res. (2009) 105:128–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190611

18.

Siegel D Devaraj S Mitra A Raychaudhuri SP Raychaudhuri SK Jialal I . Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and psoriasis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2013) 44:194–204. doi: 10.1007/s12016-012-8308-0

19.

Ridker PM . Inflammatory biomarkers and risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, and total mortality: implications for longevity. Nutr Rev. (2007) 65:S253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00372.x

20.

Satoh K Shimokawa H . High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: still need for next-generation biomarkers for remote future cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J. (2014) 35:1776–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu115

21.

Zhou Y Han W Gong D Man C Fan Y . Hs-CRP in stroke: a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. (2016) 453:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2015.11.027

22.

Wang Y Li J Pan Y Wang M Meng X Wang Y . Association between high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and prognosis in different periods after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack. J Am Heart Assoc. (2022) 11:e025464. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.025464

23.

Li Y Zhong X Cheng G Zhao C Zhang L Hong Y et al . Hs-CRP and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. (2017) 259:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.02.003

24.

Yao SM Zheng PP Wan YH Dong W Miao GB Wang H et al . Adding high-sensitivity C-reactive protein to frailty assessment to predict mortality and cardiovascular events in elderly inpatients with cardiovascular disease. Exp Gerontol. (2021) 146:111235. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111235

25.

Block G Jensen CD Dalvi TB Norkus EP Hudes M Crawford PB et al . Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic Biol Med. (2009) 46:70–7. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.030

26.

Jafarnejad S Boccardi V Hosseini B Taghizadeh M Hamedifard Z . A meta-analysis of randomized control trials: the impact of vitamin C supplementation on serum CRP and serum hs-CRP concentrations. Curr Pharm Des. (2018) 24:3520–8. doi: 10.2174/1381612824666181017101810

27.

Crook J Horgas A Yoon SJ Grundmann O Johnson-Mallard V . Insufficient vitamin C levels among adults in the United States: results from the NHANES surveys, 2003–2006. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3910. doi: 10.3390/nu13113910

28.

Crook JM Horgas AL Yoon SL Grundmann O Johnson-Mallard V . Vitamin C plasma levels associated with inflammatory biomarkers, CRP and RDW: results from the NHANES 2003–2006 surveys. Nutrients. (2022) 14:1254. doi: 10.3390/nu14061254

29.

Lin YT Wang LK Hung KC Chang CY Wu LC Ho CH et al . Prevalence and predictors of insufficient plasma vitamin C in a subtropical region and its associations with risk factors of cardiovascular diseases: a retrospective cross-sectional study. Nutrients. (2022) 14:1108. doi: 10.3390/nu14051108

30.

Abuhajar SM Taleb MH Ellulu MS . Vitamin C deficiency and risk of metabolic complications among adults with chronic respiratory diseases: a case-control study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2021) 43:448–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.03.007

31.

Ellulu MS Rahmat A Ismail P Khaza'ai H Abed Y . Effect of vitamin C on inflammation and metabolic markers in hypertensive and/or diabetic obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2015) 9:3405–12. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S83144

32.

Safabakhsh M Emami MR Zeinali Khosroshahi M Asbaghi O Khodayari S Khorshidi M et al . Vitamin C supplementation and C-reactive protein levels: findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Complement Integr Med. (2020). doi: 10.1515/jcim-2019-0151

33.

Carr AC Bradley HA Vlasiuk E Pierard H Beddow J Rucklidge JJ . Inflammation and vitamin C in women with prenatal depression and anxiety: effect of multinutrient supplementation. Antioxidants (Basel). (2023) 12:941. doi: 10.3390/antiox12040941

34.

Lee MT Jung SY Baek MS Shin J Kim WY . Early vitamin C, hydrocortisone, and thiamine treatment for septic cardiomyopathy: a propensity score analysis. J Pers Med. (2021) 11:610. doi: 10.3390/jpm11070610

35.

Block G Jensen CD Morrow JD Holland N Norkus EP Milne GL et al . The effect of vitamins C and E on biomarkers of oxidative stress depends on baseline level. Free Radic Biol Med. (2008) 45:377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.04.005

36.

Abdoulhossein D Taheri I Saba M Akbari H Shafagh S Zataollah A . Effect of vitamin C and vitamin E on lung contusion: a randomized clinical trial study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). (2018) 36:152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2018.10.026

37.

du W Fan HM Zhang YX Jiang XH Li Y . Effect of flavonoids in hawthorn and vitamin C prevents hypertension in rats induced by heat exposure. Molecules. (2022) 27:866. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030866

38.

May JM Qu ZC . Transport and intracellular accumulation of vitamin C in endothelial cells: relevance to collagen synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. (2005) 434:178–86. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.10.023

39.

Lefferts EC Hibner BA Lefferts WK Lima NS Baynard T Haus JM et al . Oral vitamin C restores endothelial function during acute inflammation in young and older adults. Physiol Rep. (2021) 9:e15104. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15104

40.

Chaghouri P Maalouf N Peters SL Nowak PJ Peczek K Zasowska-Nowak A et al . Two faces of vitamin C in hemodialysis patients: relation to oxidative stress and inflammation. Nutrients. (2021) 13:791. doi: 10.3390/nu13030791

41.

Fowler AR Truwit JD Hite RD Morris PE DeWilde C Priday A et al . Effect of vitamin C infusion on organ failure and biomarkers of inflammation and vascular injury in patients with sepsis and severe acute respiratory failure: the CITRIS-ALI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. (2019) 322:1261–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11825

42.

Rosengrave P Spencer E Williman J Mehrtens J Morgan S Doyle T et al . Intravenous vitamin C administration to patients with septic shock: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Crit Care. (2022) 26:26. doi: 10.1186/s13054-022-03900-w

43.

Fouladvand F Falahi E Asbaghi O Abbasnezhad A . Effect of vitamins C and E co-supplementation on serum C-reactive protein level: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prev Nutr Food Sci. (2020) 25:1–8. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2020.25.1.1

44.

Cara KC Beauchesne AR Wallace TC Chung M . Effects of 100% Orange juice on markers of inflammation and oxidation in healthy and at-risk adult populations: a scoping review, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Adv Nutr. (2022) 13:116–37. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab101

Summary

Keywords

vitamin C, ascorbic acid, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, inflammation, NHANES

Citation

Ding N, Zeng Z, Luo J and Li K (2023) The cross-sectional relationship between vitamin C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels: insights from NHANES database. Front. Nutr. 10:1290749. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1290749

Received

19 September 2023

Accepted

30 October 2023

Published

10 November 2023

Volume

10 - 2023

Edited by

George Pounis, Harokopio University, Greece

Reviewed by

Mari Luz Moreno, Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir, Spain; Naheed Aryaeian, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Ding, Zeng, Luo and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Keng Li, doctorlikeng@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.