Abstract

Objective:

This scoping review evaluates the breadth of research on avocado intake and health, considering all populations and health outcomes (registered on Open Science Foundation at https://osf.io/nq5hk).

Design:

Any human intervention or observational study where effects could be isolated to consumption of avocado were included. A systematic literature search through April 2024 was conducted (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and CENTRAL) and supplemented by backwards citation screening. Dual screening, data extraction, and conflict resolution were performed by three reviewers and an interactive evidence map was created.

Results:

After deduplication, 8,823 unique records were retrieved; 58 articles met inclusion criteria, comprising 45 unique studies (28 interventions, 17 observational studies). Studies were largely conducted in the United States or Latin America and generally included adults, with overweight/obesity, frequently with elevated lipid concentrations. Interventions assessed the impact of diets enriched in monounsaturated fatty acids, diets higher/lower in carbohydrates, or in free-feeding conditions. Larger amounts of avocados were used in interventions than commonly consumed in observational studies (60–300 vs. 0–10 g/d, respectively). Blood lipids, nutrient bioavailability, cardiovascular risk, glycemia, and anthropometric variables were the most common outcomes reported across all studies.

Conclusion:

Future recommendations for novel research include the study of: European, Asian, adolescent or younger, and senior populations; dose–response designs and longer length interventions; dietary compensation; and the need for greater replication. The results have been made public and freely available, and a visual, interactive map was created to aid in science translation. This evidence map should enable future meta-analyses, enhance communication and transparency in avocado research, and serve as a resource for policy guidance.

Introduction

Consuming nutrient-dense foods is a key component of having a high-quality diet and maintaining general health and wellbeing throughout the lifespan. The 2020–2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommend half of each meal comprise fruits and vegetables (1). The avocado is a nutrient-rich food whose intake is associated with improved diet quality (2, 3). One-third of a medium-sized avocado (50 g) contains approximately 80 kcals, 3.4 g fiber (11% daily value [DV]), 44.5 μg folate (10% DV), 0.73 mg pantothenic acid (15% DV), 85 μg copper (10% DV), 10.5 μg vitamin K (10% DV), 254 mg potassium (7.5% DV), and 4 mg of sodium (0.2% DV) (4, 5). Additionally, avocados have a fatty acid composition rich in monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) (6, 7). Recent research suggests that avocado intake may beneficially impact cognitive functions (8, 9) and skin health (10).

A meta-analysis estimated that every 1% energy replacement of carbohydrates with MUFA (in subjects without disturbances of lipid metabolism or diabetes) can reduce LDL cholesterol by 0.8 mg/dL, triacylglycerol by 1.7 mg/dL, and increase HDL by 0.7 mg/dL (11). To our knowledge, four meta-analyses have assessed the effect of avocados on total cholesterol, triacylglycerols, HDL and LDL cholesterol (12–15). Results between these meta-analyses were heterogenous, as 3/4 found reductions in total cholesterol (13–15), 1/4 found reductions in triacylglycerols (15), 2/4 found increases in HDL (12, 14), 3/4 found reductions in LDL cholesterol (13–15), and the remainder in each case demonstrating a neutral effect of avocado on the blood lipid of interest. Two meta-analyses concluded that avocado intake has minimal impact on body weight or body composition (12, 16), and James-Martin et al. (13) concluded that studies were too heterogenous to meta-analyze outcomes including anthropometrics, glycemia, blood pressure, oxidative stress markers, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.

Despite several meta-analyses assessing avocado intake and health, variability in their methods (inclusion criteria, sub-group analyses, use or lack of observational data, and exclusion of non-English literature) and results complicate definitive conclusions that avocado intake affects circulating lipids (or most other health outcomes). An additional constraint in some reviews (12, 13, 15) was the inability to identify a dose–response effect, given the inclusion of studies that did not specify avocado intake or studies in which the effect could be attributed to foods co-administered with avocado. Establishing a dose–response effect would significantly contribute to the ability to understand how avocado consumption impacts health.

Although several systematic reviews on the topic have been published, each varied substantially in inclusion criteria (12–18). To our knowledge, no review has been conducted systematically with minimal restrictions on study design, duration, population, outcomes, and language. Therefore, the aims of this scoping review were to systematically summarize studies on avocado intake in a single, comprehensive evidence map that can be used to (1) aid in the characterization of participant populations, study designs, dietary patterns, outcomes, and avocado intake reported in the literature, (2) visualize the strengths and gaps of the research on avocados and health, (3) identify and generate ideas for future research, (4) educate the broader nutrition science community on what is known about avocado nutrition, and (5) support future meta-analyses. To maintain relevancy with public policy, this review adapted methods used by the USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (NESR) methodology (19), with some modifications to include numerous study types, those published in non-English languages, and trials conducted in any country.

Methods

This scoping review and evidence map was conducted in accordance with PRISMA-ScR (20) recommendations for scoping reviews and was registered with Open Science Foundation (OSF) at https://osf.io/nq5hk. Contrary to a systematic or narrative review, it was not designed to synthesize the results of each study, but to summarize the quantity and characteristics of the available evidence.

Search strategy

This review aimed to find, assess, and synthesize all intervention and observational studies that quantified avocado intake in humans and associated health outcomes. A systematic literature search was conducted through PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and CENTRAL on October 17th, 2023, with no date restrictions, and again on April 29th, 2024, date restricted to the time between searches. Searches included terms related to the intake of avocado and MUFA and are provided in full detail in the Supplementary methods. The electronic search was supplemented with backward citation screening of all in-scope articles. Backward citation screening was performed using Scite (Henderson, NV, USA)1 or Spidercite (Systematic Review Accelerator, Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia)2 to export all reference lists of in-scope articles, where possible. Exported reference lists were subsequently uploaded to Covidence (Melbourne, Australia)3 and underwent single-review screening (title/abstract and full-text). Where full reference lists could not be exported and imported into Covidence, reference lists were manually screened for inclusion.

Eligibility criteria

The 2025 USDA NESR protocol for dietary patterns and growth, body composition, and risk of obesity (21) was modified to suit an evidence map approach and greater inclusivity of diverse populations (Table 1). Modifications related to an evidence map approach (and not a systematic review) included expansion of criteria by: including cross-sectional and case–control studies and excluding studies on allergenicity and methods validation; removing restrictions on publication dates, population health status, study duration, language, and country; expanding outcomes of interest; and requiring exposure to avocado pulp (not an extract or oil thereof) to be quantified, statistically analyzed with relation to a health outcome, and isolatable in multi-component interventions. Modifications related to inclusivity were inclusion of studies on populations of any health status and those published in any language or country regardless of their Human Development Index, given numerous studies have been published in countries where English is not the primary language (especially Mexico).

Table 1

| NESR protocol criteria1 | Amendments to NESR protocol |

|---|---|

| Study design Include: randomized controlled trials (RCTs, such as individual, cluster, and crossover trials), non-RCTs, observational cohort studies (e.g., prospective or retrospective), nested case–control studies, and mendelian randomization studies. Exclude: uncontrolled trials, cross-sectional studies, ecological studies, case–control studies, reviews, and modeling and simulation studies. | Include: cross-sectional and case–control studies Exclude: studies on allergenicity or methods validation. |

| Publication date January 1980–May 2023 | No date restrictions |

| Population study participants and life stage Children and adolescents (≥ 2 and < 19 years) Adults and older adults (> 19 years) Individuals during pregnancy/postpartum | Humans of any age |

| Population health status Studies that exclusively enrolled participants not diagnosed with a disease OR studies that enrolled some participants: diagnosed with a disease; diagnosed with a disorder that affects feeding/eating or growth (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, eating disorder); with severe undernutrition, failure to thrive/underweight, stunting, or wasting; who became pregnant using Assisted Reproductive Technologies; with multiple gestation pregnancies; receiving pharmacotherapy to treat obesity; pre- or post-bariatric surgery; and/or hospitalized for an illness, injury, or surgery | No restrictions |

| Intervention/Exposure Consumption of avocado. Multi-component intervention in which the isolated effect of the intervention of interest on the outcome(s) of interest is provided or can be determined despite multiple components | Studies must meet all of the following criteria:

|

| Comparator Consumption of different amounts of avocado | Consumption of different amounts of avocado, or an alternative source of dietary fat or macronutrients. |

| Outcome(s) NA | Include: Any outcomes related to human health and statistically analyzed for their relationship to avocado intake. Exclude: Effects of behavioral/dietary patterns on avocado intake. |

| Study duration Intervention length ≥ 12 weeks (in children, adolescents, adults, and older adults only) | No restrictions |

| Sample size No restrictions | No amendments |

| Publication status Peer-reviewed articles published in research journals | No amendments |

| Language Published in English | No restrictions |

| Country Studies conducted in countries classified as high or very high on the Human Development Index the year(s) the intervention/exposure data were collected | No restrictions. |

Eligibility criteria.

Study screening, selection, and data extraction

Dual screening at the title/abstract and full-text levels was conducted by three reviewers in Covidence4. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers or by a senior reviewer. Two reviewers independently extracted all data from each study using pre-defined sheets in Microsoft Excel, and conflicts were resolved through discussion or by a senior reviewer. No automation or AI-based tools were used for classification/categorization during screening or data extraction. Variables were extracted at either the per-study level (e.g., bibliographic information, study design, sample size, country of origin, funding source) or on a per-group level (subject characteristics, avocado and nutrient intakes, and all health outcomes measured). A complete list of all variables extracted is available in Supplementary Tables S1, S2. Data were extracted from both the main text, tables, figures, and all relevant Supplementary material. Only values (e.g., means and variation) related to avocado intake, BMI, age, sex, and blood lipids were extracted, to enable characterizing the participants studied. Where possible, data were extracted as described by the authors and re-classified or transformed for data analysis and visualization.

Data analysis and visualization

Data cleaning, transformation, descriptive analysis, and visualization were performed manually in Excel and Tableau Cloud (Tableau Server Version 2024.1.0). To avoid double-counting secondary analyses of the same study, each publication was classified according to whether it represented the “primary” report and if subsequent publications were conducted on unique populations. References to the count of primary reports indicate whether a given variable was assessed in the first or any subsequent publication from the same primary report unless specified otherwise. For example, the clinical trial NCT01235832 published by Wang et al., in 2015 and 2020 (22, 23) reported the same population but different outcomes. This clinical trial was treated as a single “primary report” rather than two. Conversely, the Persea americana for Total Health Study (NCT02740439) published initially by Edwards et al., 2020 (8) is detailed in three other publications (24–26), each of which differed slightly in the subject populations analyzed. Each publication’s sample size, subject characteristics, and outcomes were treated independently, whereas variables common to all four publications (e.g., study design, country of study) were treated as a single report. For simplicity, nearly all data reported in this manuscript were treated as a single report when multiple publications from the same data source (e.g., a survey, prospective cohort, clinical trial) exist, unless specified otherwise.

Similarly, multi-categorical information, such as a study on participants in both the United States (U.S.) and Canada (27) was stored in a single cell (e.g., U.S.; Canada) and then split into multiple rows. Thus, the percentage of primary reports that describe a given multi-categorical variable (e.g., funding sources, weight status, age of participants) may add to over 100%, as the categories are not mutually exclusive. Group and sub-group information (e.g., avocado intake in treatments A and B in males and females) were stored on multiple rows. All counts presented here were de-duplicated but not in the raw database. Unit conversions for avocado intake (e.g., from % energy, frequency, or other form into g/d) are listed within the database itself and in Supplementary Tables S3, S4. Protocols, Supplementary material, interactive visualizations, and raw data are freely available at https://github.com/Traverse-Science/Avocado-Evidence-Map, and archived at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12824839.

Results

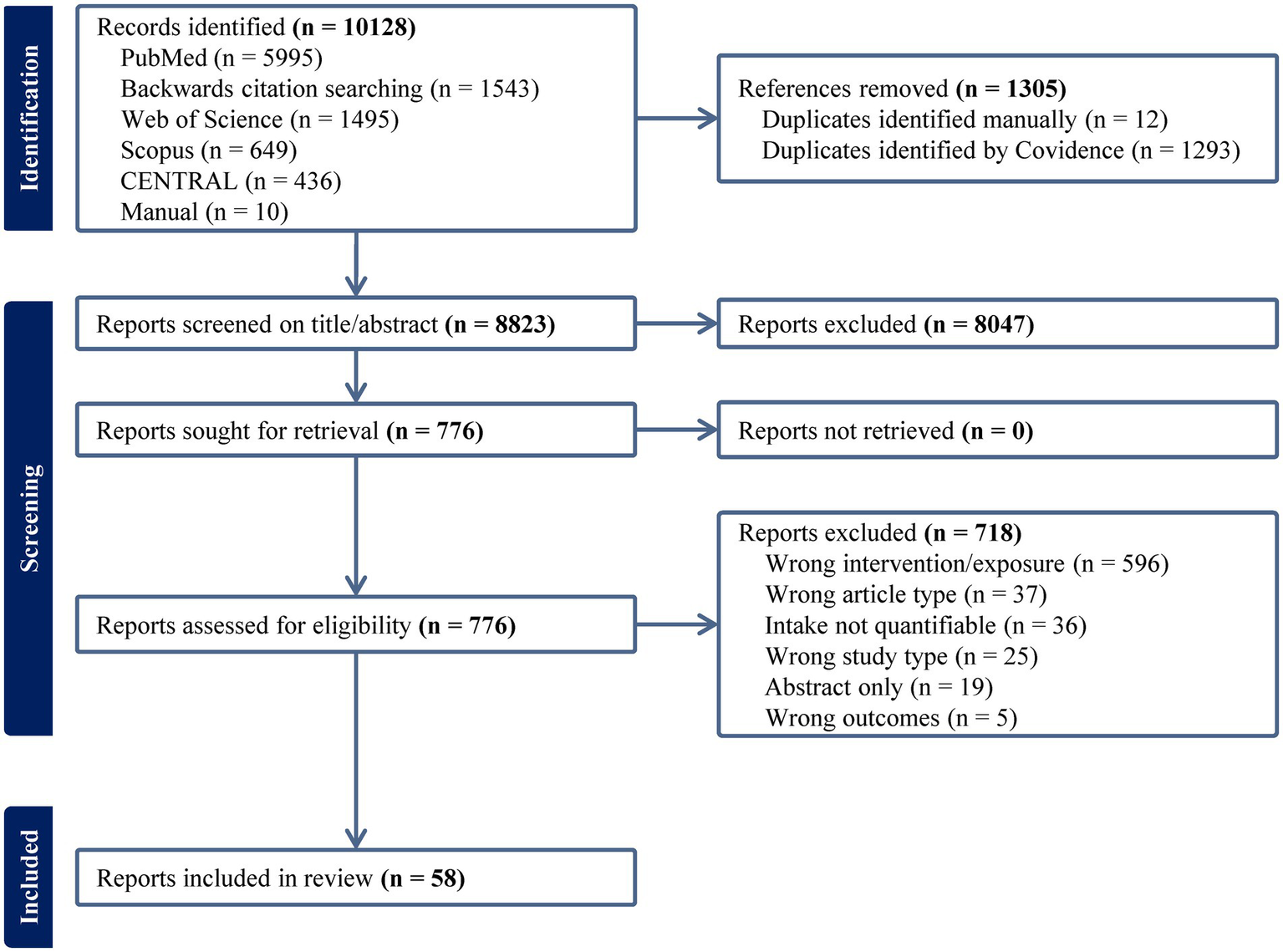

From all sources, 8,823 unique references were identified. At the title/abstract level, 8,047 references were excluded, leaving 776 articles for full-text screening. After the exclusion of 718 articles, 58 articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Most exclusions (596/718, 83%) were made because studies examined an intervention or exposure irrelevant to this review. Thirty-six studies included the study of avocado, but intake was either not specified at all or in insufficient detail. After adjusting for multiple articles from the same trial, 58 publications comprised 53 analyses of unique populations from 45 primary reports (28 interventions, 17 observational studies). Notably, there were numerous studies on the topic of avocado that were excluded from this review. Excluded studies described in previous reviews (12, 13, 15, 18, 28, 29) were excluded based on (1) intake not being quantified (30, 31), (2) provision of avocado with olive oil (32, 33) or olive oil and almonds (30, 31), and (3) single-arm trial designs (34–36). We additionally found other ineligible articles that described the provision of avocado with kiwi (37), nuts (38), multiple other foods (39, 40), lack of a control group (41), or as a pill-based supplement and not part of the diet (42). Although excluding these reduced the size of the evidence map by over 10 studies, it focused the review of interventions to those studies whose reported effects could be isolated to experimental manipulation of avocado intake alone. A list of excluded studies are available in Supplementary Data Sheet 1.

Figure 1

PRISMA diagram for searches performed on 10/17/2023 and 04/29/2024 (mm/dd/yyyy).

Among observational trials, there were five prospective cohorts (Multiethnic Cohort Study, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Nurses’ Health Study I and II, and Health Professionals Follow-up Study) that were analyzed in multiple articles (3, 43–51) (Table 2). Various sampling dates of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey were reported, but these were considered unique given each article (3, 50, 51) investigated different subject populations. Six clinical trials were reported across multiple publications, but these differed in whether they represented a secondary analysis of the same population (23, 52–54) or an analysis of a unique population (24–26, 55, 56) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Primary report | Additional publications | Unique population1 |

|---|---|---|

| Observational studies | ||

| Multiethnic Cohort Study (MEC) | Monroe et al., 2007 (43) Cheng et al., 2024 (80) | Yes |

| Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) | Wood et al., 2023 (45) | Yes |

| Cheng et al., 2023 (46) Carris et al., 2024 (79) | Yes | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (NHS), NHS II, and Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) | Pacheco et al., 2022a (47) NHS (1986–2016), HPFS (1986–2016) | Yes |

| Ericsson et al., 2022 (48) NHS (1986–2014), HPFS (1986–2016) | Yes | |

| Borgi et al., 2016 (49) NHS (1986–2014), NHS II (1999–2011) HPFS (1986–2010) | Yes | |

| National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) | Fulgoni et al., 2013 (50) 2001–2008 | Yes |

| O’Neil et al., 2017 (3) 2001–2012 | Yes | |

| Cheng et al., 2021 (51) 2011–2014 | Yes | |

| Interventions | ||

| Effects of Avocado Intake on the Nutritional Status of Families Trial (NCT02903433) Pacheco et al., 2021 (71) | Pacheco et al., 2022b (55) VanEvery et al., 2023 (56) | Yes |

| Allen et al., 2023 (52) | No | |

| NCT01235832 Wang et al., 2015 (22) | Wang et al., 2020 (23) | No |

| NCT01271829 Wien et al., 2013 (65) | Haddad et al., 2018 (53) | No |

| NCT02479048 Park et al., 2018 (86) | Zhu et al., 2019 (54) | No |

| Persea Americana for Total Health Study (NCT02740439) Edwards, 2020 (8) | Hannon et al., 2020 (24) Khan et al., 2021 (25) Thompson et al., 2021 (26) | Yes |

| Habitual Diet and Avocado Trial (NCT03528031) Lichtenstein et al., 2022 (72) | Petersen et al., 2024 (2) | No |

Publications related to the same primary report.

1An article was considered distinct (i.e., unique) from the primary report if it analyzed a different population, indicated by an analytical sample size different from the primary report, analysis on sub-groups, analysis on a subset of the population from the primary report, or sampled populations on a different time-scale. These may or may not have analyzed the same outcomes as the primary report.

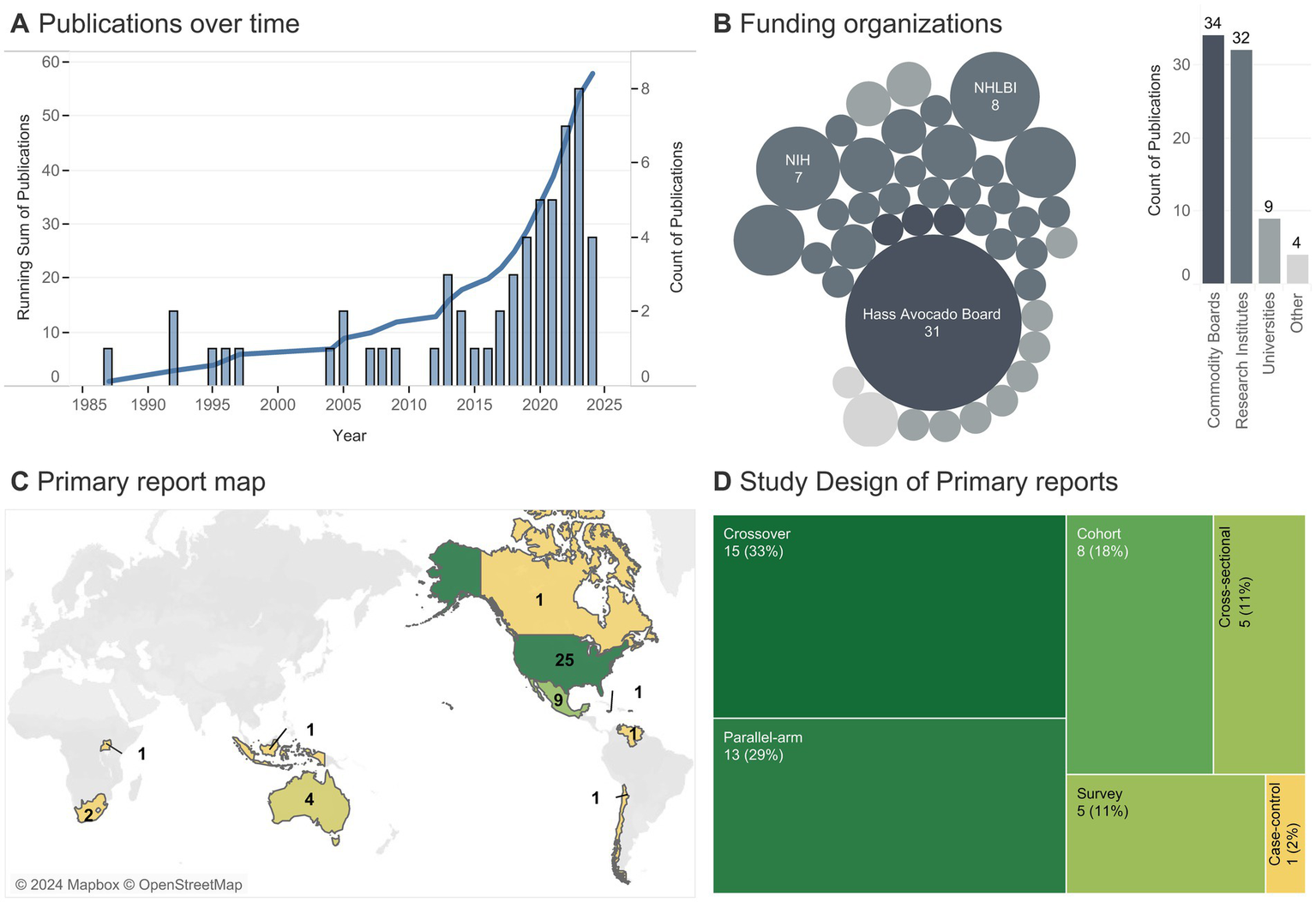

Publishing trends

The earliest in-scope research on avocados began in 1985 (Figure 2), though, to our knowledge, the first study published on avocado intake and health was by Grant et al., 1960 (34); however, that study was out-of-scope given it lacked a control group. A steep rise in publications per year began in 2017, with 29/58 (50%) articles published between 2019–2023. The top five most commonly reported funding organizations (studies could have multiple funding sources), in order, were the Hass Avocado Board (which includes the Avocado Nutrition Center), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), and the USDA. In total, 58% of articles reported funding from commodity boards, 55% from research institutes, 16% from universities, and 7% from other sources (e.g., hospitals or companies). The majority of primary reports were conducted on participants in the Americas (U.S., Mexico, Canada, Jamaica, Chile, and Venezuela) (Figure 2). No studies were conducted in Europe and only one was conducted in Asia (in Indonesia). A small number of studies were conducted in South Africa, Uganda, and Australia. The geographical trend matches the funding source, as there were no funding sources from European/Asian commodity boards, and the only research institute in Asia (Korean International Cooperation Agency) funded a study in South Africa (57). The majority of primary reports were interventions (28/45, 62%) of crossover or parallel-arm design, with the remainder observational trials, typically a prospective cohort (8/45, 18%) or cross-sectional/survey study (10/45, 22%).

Figure 2

Publishing trends. (A) The line indicates the cumulative number of publications per year (totaling 58), with bars detailing yearly publications. (B) Each bubble represents a unique funding source (one article could come from multiple sources), with the size indicating the number of articles associated with a given funding source (smallest bubble = 1 article). (C) Number of primary reports (totaling 45) conducted on participants from a given country (one primary report was conducted in both the U.S. and Canada); color indicates the number of studies. (D) Number of primary reports of a given study design (one primary report analyzed as both a cross-sectional and a cohort).

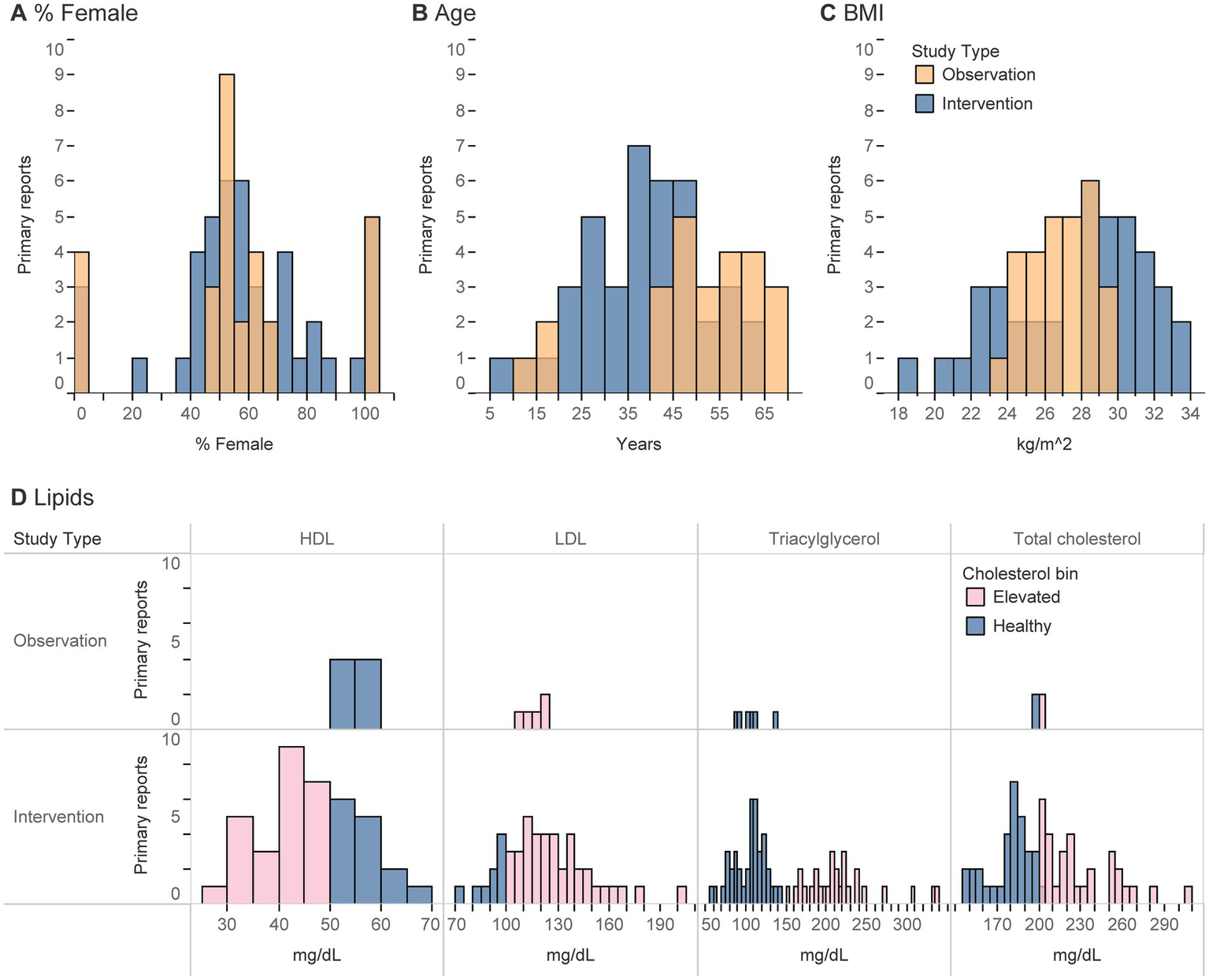

Participant characteristics

The intended population was usually described as “healthy” (no diagnosis of a medical disease/disorder) or described in vague terms such that it was assumed to be about the general population (Table 3). Only seven studies were intentionally designed to study participants with elevated blood lipids or those diagnosed with or at risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). Regardless of the intent, the majority of studies were conducted in adults, fairly balanced in sex with a skew toward females, predominantly in those with overweight/obesity, and those with elevated blood cholesterol (Table 3; Figure 3). Interventions most frequently included individuals of middle (~35–50 yrs) or college ages (~20–35 yrs), and observational studies primarily described participants ages 40 yrs. or older (Figure 3). Intervention studies exhibited a bi-modal-like distribution with participant BMI clustered in ranges of 23–26 or 28+ kg/m2, whereas observational studies reported ranges between these two peaks, from 24–29 kg/m2 (Figure 3).

Table 3

| Characteristic | Count of primary reports n (% total, column-wise) | |

|---|---|---|

| Interventions 28 (100) | Observations 17 (100) | |

| Intended population1 | ||

| Healthy/general population | 18 (64) | 15 (88) |

| Elevated cholesterol/triacylglycerols2 | 6 (21) | 0 |

| T2D or insulin resistance | 2 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Other3 | 3 (11) | 1 (6) |

| Age, yrs4 | ||

| Adolescent or younger (< 18) | 2 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Adult (≥ 18, < 65) | 25 (89) | 13 (76) |

| Senior (≥ 65) | 0 | 3 (18) |

| Sex4 | ||

| Mostly female (> 60% female) | 14 (50) | 10 (59) |

| Balanced (40–60% female) | 14 (50) | 10 (59) |

| Mostly male (< 40% female) | 5 (18) | 4 (24) |

| BMI,4,5 kg/m2 | ||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Healthy weight (≥ 18.5, < 25) | 7 (25) | 4 (24) |

| Overweight or obese (≥ 25) | 17 (61) | 13 (76) |

| Blood lipid concentrations1,2,4–6 | ||

| Healthy (by at least one metric) | 17 (61) | 4 (24) |

| HDL cholesterol | 9 (32) | 4 (24) |

| LDL cholesterol | 4 (14) | 0 |

| Total cholesterol | 14 (50) | 2 (12) |

| Triacylglycerols | 13 (46) | 3 (18) |

| Elevated (by at least one metric) | 17 (61) | 3 (18) |

| HDL cholesterol | 13 (46) | 0 |

| LDL cholesterol | 15 (54) | 3 (18) |

| Total cholesterol | 12 (43) | 2 (12) |

| Triacylglycerols | 9 (32) | |

Participant characteristics.

T2D, type 2 diabetes. 1Intended population was categorized according to subject health status at baseline/time of analysis, not at follow-up. If participants were not explicitly stated as healthy, the “general population” was assumed to be the target, unless inclusion criteria specified otherwise or authors reported intentional recruitment of participants with a specific disease/disorder. 2Given the intended population was not always specified, some trials did not consider their participants to have elevated blood lipids. This is shown by the discrepancy between the five primary reports (22, 23, 58–61) that explicitly recruited participants with dyslipidemia compared to 21 primary reports that reported at least one group of participants with elevated blood lipids at some point during the study. 3“Other” category includes conditions such as hookworm (57), metabolic syndrome (67, 77), and prostate cancer (82). 4Categories are not mutually exclusive, and not all studies reported each variable. Where values do not sum to 100% was typically in relation to incomplete reporting, or reporting of the same variable over multiple sub-groups (e.g., BMI in multiple age-groups, or lipids across males/females). 5Values represent the number of primary reports that described a given characteristic (using an absolute value, mean, or median) of any group/sub-group at any point during the study. For example, a hypothetical study wherein an analytical group had a high value (e.g., BMI, cholesterol) at baseline that lowered after follow-up would be counted in multiple ranges. Values were presented this way as not all studies reported participant characteristics at baseline. 6Classified according to any of HDL, LDL, or total cholesterol, where healthy was designated (all in mg/dL) as 125–200 total cholesterol, < 100 LDL cholesterol, > 50 HDL cholesterol, and < 150 triacylglycerols, using ranges set at https://medlineplus.gov/cholesterollevelswhatyouneedtoknow.html. Although HDL > 40 is considered healthy for males, most studies did not separate the data by sex. Healthy concentrations were based on guidelines for women given greater representation of females across studies.

Figure 3

(A-D) Histograms represent the number of primary reports that described a given participant characteristic (using an absolute value, mean, or median) of any analytical group/sub-group at any point during a study. (D) For lipids, values were classified as healthy if in the ranges of 125–200 for total cholesterol, < 100 for LDL, > 50 for HDL, and < 150 for triacylglycerols (all in mg/dL).

Despite the relatively small number of primary reports (22, 23, 58–61) that explicitly recruited participants for their elevated blood lipids (18%, Table 3), all interventions that reported blood lipid concentrations (17/28 primary reports) detailed elevated blood lipid concentrations by at least one metric (HDL, LDL, total cholesterol, or triacylglycerols) at some point during the study (Table 3). Participants were most likely to be rated as having elevated lipids, or conversely least likely to be rated as healthy, according to HDL and LDL concentrations. These characteristics were infrequently reported among observational studies.

Design of dietary interventions

There were four different designs of dietary control among intervention trials: (1) Constant macronutrient intake between groups (on a % energy basis) with enrichment of MUFA from avocado, (2) Higher vs. lower carbohydrate/fat intake (on a % energy basis) with avocado as a primary fat source, (3) Free feeding of avocado with no control over macronutrient intake or energy consumption, and (4) Studies not concerned with macronutrient intake (Table 4). Habitual intake studies represent the most translatable designs as they allow for potential dietary compensation; however, it can be difficult to isolate whether the resulting changes can be attributed to the intake of avocado itself independent of dietary compensation.

Table 4

| Count of primary reports of interventions, n (%) 28 (100) | Comparator | |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental control of energy from macronutrients | Avocado consumption with replacement of other foods 19 (68) | Avocado consumption on top of habitual/other dietary intake 12 (43) |

| Macronutrients constant between groups 8 (29) | MUFA enrichment 8 (29) | 11 (4) |

| Macronutrients allowed to deviate between groups 16 (57) | Higher vs lower CHO 92 (32) | Free feeding 92 (32) |

| Control of macronutrients not reported 5 (18) | 3 (11) | 2 (7) |

Design of macronutrient intake in interventions.

CHO, carbohydrates. 1Macronutrients (on a % energy basis), but not energy, were held constant (53, 65), hence why it’s possible to maintain equivalent macronutrient intake between groups without replacement. This primary report also included a group that controlled intake with replacement of other foods and is represented under the “MUFA enrichment” group. 2Two studies included both an ad libitum habitual intake group and an arm with controlled intake with replacement of other foods and are represented in both comparator columns (6, 59).

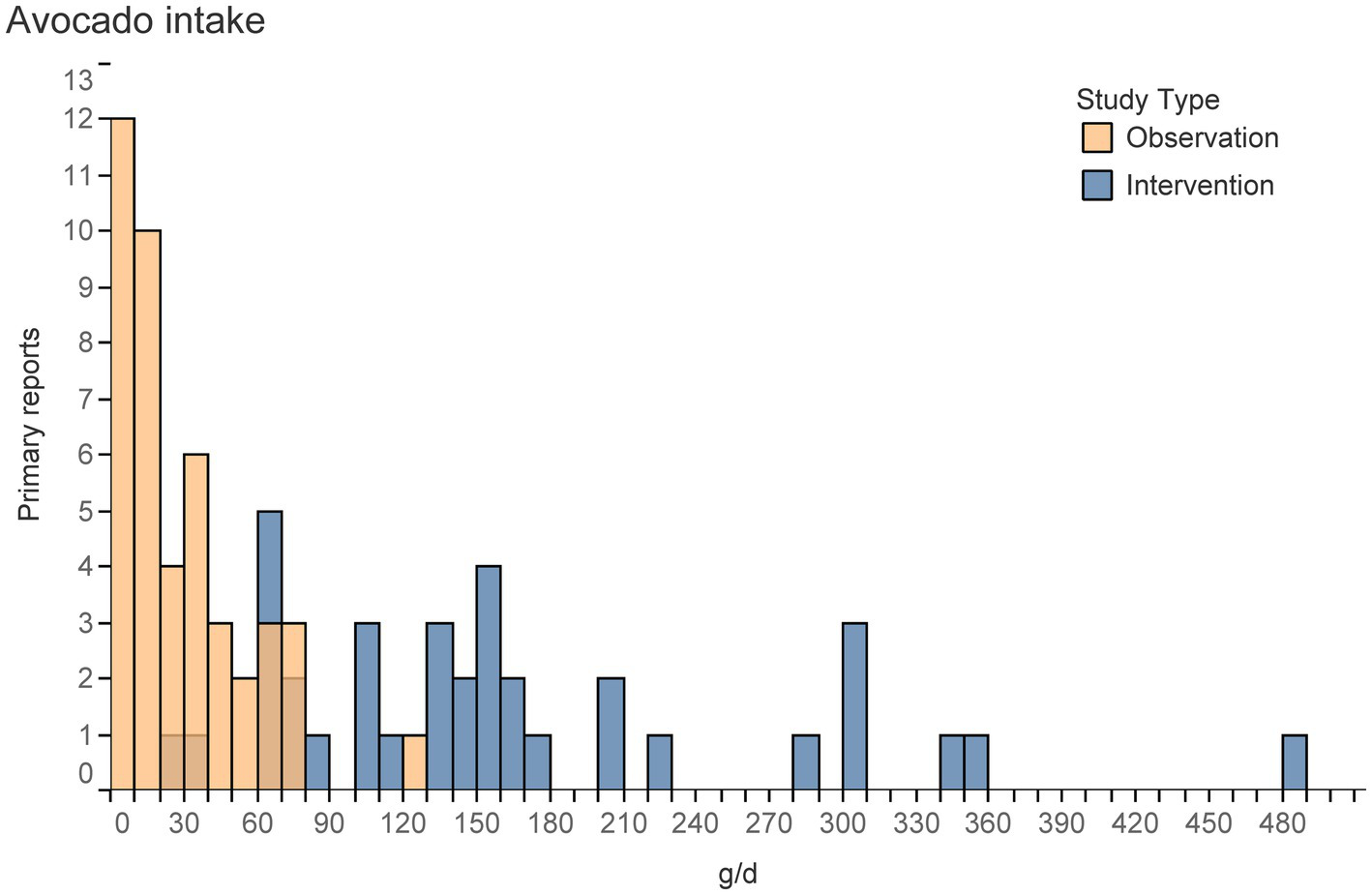

The most common comparators included the consumption of some avocado to no avocado (Table 5). However, observational trials more frequently included dose–response evaluations. Among the observational trials, most primary reports (44%) assessed the intake of whole, raw avocado, but not avocado from all food sources. In such cases, participants who consumed guacamole but not whole avocado would be considered “non-consumers” of avocado. Only 2/17 observational primary reports (62, 63) estimated intake from all food sources of avocado. This is likely why the most common intake of avocados was reported between 0–10 g/d (7% of an avocado/d, assuming 1 avocado = 150 g) among observational trials (Figure 4). Among interventions, intakes of avocado spanned between 30–490 g/d (or per meal, in the case of acute studies) but was most commonly 60–70, 150–160, 210–220, or 300–310 g/d (Figure 4). Such amounts are roughly equivalent to 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 whole avocados/d (assuming the average avocado weighs 150 g). The difference in exposure to avocado varies by upwards of 5-10x between observational and intervention trials.

Table 5

| Characteristic | Count of primary reports, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Interventions | Observations | |

| Comparator1 | 28 (100) | 17 (100) |

| No avocado | 26 (93) | 8 (47) |

| Less avocado | 1 (4) | 3 (18) |

| Dose–response | 1 (4) | 8 (47) |

| Avocado Source1 | ||

| Whole, raw avocado only | NA | 1 (6) |

| Avocado and guacamole | NA | 5 (29) |

| All sources | NA | 3 (18) |

| Not specified | NA | 10 (59) |

| As directed (in designed meals or as desired) | 28 (100) | NA |

| Intended energy balance of participants1,2 | ||

| Not applicable (acute studies) | 8 (29) | NA |

| No intent (ad libitum, free-living, habitual) | 9 (32) | NA |

| Weight loss | 4 (14) | NA |

| Weight maintenance | 7 (25) | NA |

| Weight gain | 0 | NA |

| Intended energy balance between groups1,2 | ||

| No intent | 8 (29) | NA |

| Hypocaloric | 0 | NA |

| Isocaloric | 18 (64) | NA |

| Hypercaloric | 5 (18) | NA |

| Nutrient intake ascertainment method3 | ||

| FFQ or custom questionnaire | 2 (7) | 11 (65) |

| 24-h dietary recalls | 2 (7) | 6 (35) |

| 3-7d food/diet records | 2 (7) | 0 |

| Prescribed/controlled | 9 (32) | 0 |

| Not applicable | 9 (32) | 0 |

| None reported | 4 (14) | 0 |

Dietary characteristics.

FFQ, food frequency questionnaire. 1This is a multi-categorical option, thus rows within this category may not sum to 100%. 2Energy balance of the participants and balance between groups were classified according to the described intent of the authors, and not the actual energy balance achieved in the study. Actual energy balance was frequently not possible to determine or may have differed from what was intended, especially in the case of free-feeding studies. 3Reporting of a method for ascertaining nutrient intake does not indicate whether nutrient intakes themselves were analyzed and/or reported.

Figure 4

Histogram represents the number of primary reports that described a given level of avocado intake (e.g., using an absolute value, mean, median, or quantiles) of any group/sub-group at any point during a study. Excludes groups with non-zero intakes from control groups or non-consumers.

Among the interventions, the intended energy balance of participants was either not relevant (29%, in acute studies), not explicitly controlled (32%, among habitual intake or ad libitum designs), or either a weight maintenance (25%) or weight loss (14%) design (Table 5). Sixty-four percent of interventions controlled intake such that comparisons between groups were isocaloric, 29% allowed energy intake to deviate (purposefully or due to dietary compensation), and a small proportion (18%) assessed avocado intake in a hypercaloric design. Such hypercaloric designs were more common in bioavailability or acute intake studies comparing avocado intake to the lack thereof or to different foods (53, 64–68).

Observational trials used either a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) or food/diet record, and 88% of observational trials described the energy intake of participants compared to 65% of interventions. Intervention trials usually controlled nutrient/food intake through a prescribed diet, did not report nutrient intake at all (14%), or did so using a FFQ, 24-h recall, or 3-7d food record (7%) (Table 5).

Reporting nutrient intake was usually completed (Table 6), with 75% or fewer primary reports of interventions reporting energy or macronutrient contributions to energy. Although 88% of observational trials reported energy intake, ≤ 47% reported macronutrient contributions to energy (Table 6). Despite the objective of many studies being to investigate cardiovascular-related events and biomarkers (Figure 5), only 5/28 and 7/28 interventions reported cholesterol or fiber intake, respectively. Vitamins, minerals, and carotenoid consumption were similarly reported infrequently, however observational reports described vitamin and mineral intake more frequently than interventions (Table 6).

Table 6

| Characteristic1 | Count of primary reports, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Interventions 20 (100) | Observations 17 (100) | |

| Energy | 13 (65) | 15 (88) |

| Fat, % E | 15 (75) | 8 (47) |

| Saturated fatty acids | 8 (40) | 6 (35) |

| MUFA | 9 (45) | 7 (41) |

| PUFA | 8 (40) | 7 (41) |

| Carbohydrate, % E | 15 (75) | 7 (41) |

| Dietary fiber | 7 (35) | 8 (47) |

| Total sugars | 1 (5) | 0 |

| Protein, % E | 15 (75) | 6 (35) |

| Vitamins A, B, C, D, E or K | 3 (15) | 5 (29) |

| Minerals | ||

| Calcium | 2 (10) | 4 (24) |

| Copper, iron, phosphorus, or zinc | 1 (5) | 2 (12) |

| Magnesium | 1 (5) | 6 (35) |

| Potassium | 2 (10) | 6 (35) |

| Sodium | 2 (10) | 5 (29) |

| Lutein/zeaxanthin, lycopene, or carotene | 2 (10) | 1 (6) |

| Other | ||

| Cholesterol | 5 (25) | 2 (12) |

| Alcohol | 2 (10) | 8 (47) |

Studies reporting nutrient intake.1

% E, % of total energy. 1Includes either planned or actual nutrient intakes of the entire diet (measured at any point in time, baseline or follow-up) and excludes eight primary reports of acute studies on avocado-containing meals (not the entire diet), where the background diet would not be expected to have been reported. Intakes were not counted if reports provided partial information such as the composition of experimental meals but not intake of all other nutrients. Unless specified otherwise, counts include any unit described (g/kg, g/d, % E, etc.).

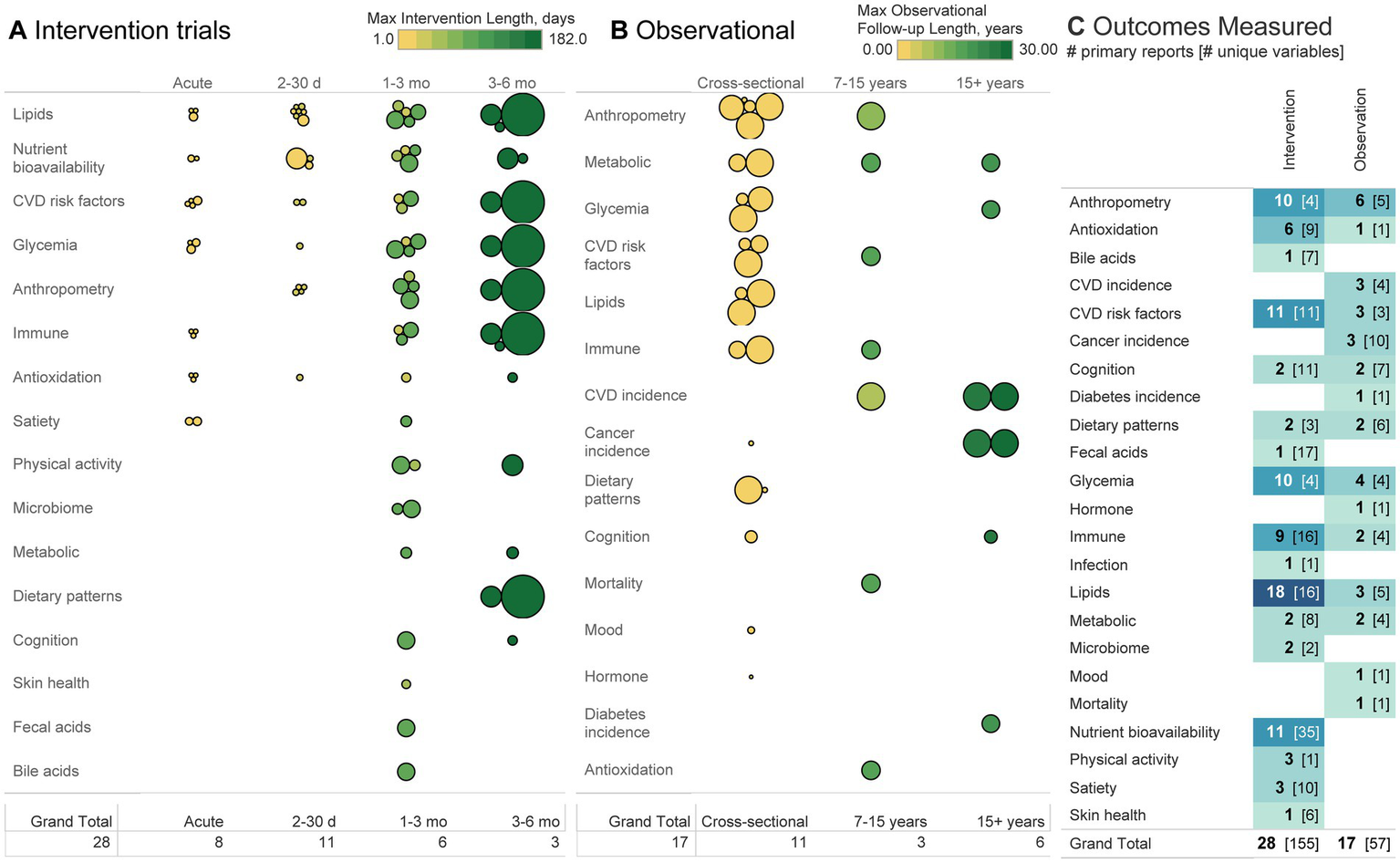

Figure 5

(A, B) Each bubble represents a primary report, organized according to sample size (size of bubble), length of intervention/follow-up (observational cohorts may have multiple follow-up periods according to different analyses and may thus be listed over multiple follow-up lengths), and a broad classification of the outcomes studied. (C) Heatmap depicts the number of primary reports and the number of distinct variables measured within the subdomain listed. For example, 10 interventions measured anthropometric outcomes using four different variables (e.g., weight, BMI, body fat, and body size). Each of those four variables may have then used a different method of measurement (not depicted), such as describing body fat using total fat % or mass of visceral adipose tissue. The greater the number in brackets, the greater the heterogeneity between studies in variables reported and methods of measurement used.

Outcomes

Among intervention trials, lipids, nutrient bioavailability, CVD risk factors (e.g., blood pressure/flow/structure/function or biomarkers, excluding anthropometrics and lipids), anthropometrics, and glycemia were the most common outcomes measured (Figure 5). Nutrient bioavailability was measured with the greatest heterogeneity (34 variables were measured across 11 studies) compared to anthropometrics or glycemia, where four variables were measured across 10 trials. Outcomes whose number of variables measured exceeded the number of primary reports indicate high heterogeneity and where greater replication would be valuable. Trials lasting longer than one month tended to have larger sample sizes than those of shorter duration. Fourteen of 28 primary interventions (50%) were conducted within one month or shorter, 11 conducted for 1–3 months (39%), and three for 3–6 months (11%).

Among observational trials, anthropometry, CVD incidence, and glycemia were the most commonly measured. Most measures were analyzed in a cross-sectional design (11/17 primary observational reports), whether that be a national survey or otherwise. CVD incidence was not measured among any cross-sectional studies and was the outcome analyzed in the greatest number of cohort studies (47, 49, 69). Follow-up lengths for all outcomes were usually 10+ years, with only one cohort study (69) reporting a shorter follow-up period. Outside of cross-sectional studies only 1–2 studies have been conducted on any given outcome, representing a general lack of longitudinal data across all topics.

Discussion

The objective of this scoping review was to systematically identify and characterize the body of evidence related to consumption of avocado and health, specifically in studies where the effect of the exposure was isolatable (compared to multi-component exposures containing avocado). Overall, research was primarily focused on cardiometabolic outcomes, with emerging domains including that of antioxidation, gut health, skin health, cognition, and immunity. Most studies evaluated participants in adulthood, typically overweight, and fairly balanced between sexes.

At first glance, it may seem that the large number of studies conducted on cardiometabolic outcomes renders the topic sufficiently studied. However, take the adjacent measure anthropometry for example. With respect to policy guidance, the USDA NESR protocol commonly uses a study duration cutoff of ≥12 weeks (sometimes as long as 6 months) in their eligibility criteria for studies on body composition (21, 70). In this scoping review, 10 primary interventions evaluated anthropometry (e.g., body weight, BMI, or body fat), two of which were conducted for ≥12 weeks (the Habitual Diet and Avocado trial, and the Effects of Avocado Intake on the Nutritional Status of Families trial) (71, 72). Both measured BMI, and one measured body fat (72). From this perspective, the size of the body of evidence quickly shrinks. Conversely, of the 11 studies on nutrient bioavailability, two have been measured on an acute scale (66, 68). Thus, there is more to learn regarding avocado’s impact on nutrient bioavailability on an acute scale. In general, nearly every topic outside of cardiometabolic-related outcomes represents a novel gap in the research, regardless of study design.

Despite only a few exclusively investigating the impact of avocado intake in populations with dyslipidemia, most studies sampled populations with elevated blood lipid concentrations. In some cases this issue is not serious and simply related to heterogenous populations and the report of participants across a range of healthy and elevated levels. For example, Alvizouri-Muñoz et al. (6), report subjects with 2.29–2.68 mmol/L LDL (88–103 mg/dL), thus subjects were in both the “healthy” and “elevated” categories. In other cases, reporting has serious implications for future meta-analysis. For example, Scott et al. (9) and Colquhuon et al. (73) do not explicitly report their subjects as having elevated lipids, yet subjects in both studies do. Unfortunately, this can create confusion, as a later meta-analysis (13) considered the participants in Scott et al. (9) as normocholesterolemic, despite meeting criteria for hypercholesterolemia based on LDL. For other studies lipid status was not discernible (74) given only the change from baseline, and not the actual baseline values, were reported. To avoid confusion, we recommend that (1) researchers avoid explicit uses of the term “healthy” unless well-defined, (2) researchers avoid publishing change-from-baseline-data without also reporting the raw baseline values, and (3) that future reviewers use the summary or baseline data to make such conclusions, rather than the terminology used by original authors.

Translating between interventions and observational data

Observational studies typically measured a distinct population compared with interventions (either younger or older than interventions, with a typical or overweight but not obese BMI) and reported much lower intakes of avocado than interventions (Figure 4). Figure 5 indicates both the heterogeneity in outcomes measured between the two designs as well as the general dearth of observational studies. Ultimately, the observational data and interventions were conducted on separate populations, exposure levels, and endpoints, and may be ill-suited for substantiating the other’s findings. This gap represents a promising opportunity for future epidemiological studies. We recommend a review to identify existing observational data that measured avocado intake for further secondary analysis. Doing so would bolster the available epidemiological evidence across a wide range of exposures, populations, and endpoints, thus filling some gaps between intervention and observational trials. This may be achievable by specifically identifying observational data in Europe. Despite no published research on the topic from participants in Europe, in 2023 Europe accounted for the second highest global import of avocado (0.76 billion kg), 7x higher than the next largest import region (Canada at 0.11 billion kg), and 60% that of the U.S. (1.26 billion kg) (75). Thus, the high import of avocado into Europe makes the region a novel research population and potential source for secondary data on avocado consumption and health. Replicating observational studies conducted in the US in other countries in subjects of diverse race/ethnicity, socioeconomic position, gender identity, and health disparities would also satisfy methodological recommendations to help evaluate diet-health relationships stated in the Scientific Report of the 2025 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (76).

Availability of data for causal inference

The ability to make causal inferences about the impact of avocado intake and health is limited by a few characteristics of the body of literature, most notably the ability to account for dose–response effects and dietary compensation from avocado consumption.

First, one of 28 interventions (77) study evaluated a dose–response effect in a controlled trial. While doing so was more common among observational trials, intervention studies assessed high intakes of avocado (typically >50 g/d), whereas observational studies reported low intakes of avocado (typically 0–40 g/d), an underestimate that is likely related to only 2/17 observational primary reports calculating intake from all food sources of avocado (62, 63) (Figure 4). The difference in avocado consumption between interventions and observational trials complicates the comparison of findings from one study design to the other.

More importantly, there is limited understanding of dietary compensation from avocado intake. A third of trials provided avocado in a free-feeding context, and numerous trials either did not measure, analyze, or report nutrient intakes (Tables 5, 6). Such characteristics limit the ability to experimentally isolate or statistically evaluate the effect of the background diet. To overcome such limitations, we recommend the following. First, future interventions should consider using a dose–response design to identify if increasing avocado intake has a causal impact on health. Second, estimation of exposure to avocado in observational studies should estimate intake from all possible food sources (e.g., raw avocado pulp, guacamole, sushi, etc.). Estimation of avocado intake from food frequency questionnaires may be more accurate than from 24-h recalls or 3-7d food diaries in populations that consume avocado infrequently. Third, all studies (including those of acute nature) should measure and report energy, macronutrient, and micronutrient intake at the start and end of the trial or follow-up period. Doing so would enable quantification of potential dietary compensation and the ability to control for the background dietary pattern. Lastly, alongside macronutrient and MUFA intake, fiber should be considered a critical nutrient to control for. Fiber has a known, beneficial impact on cardiovascular health, and in the United States there are approved health claims related to fiber intake and coronary heart disease (21 CFR 101.77, 21 CFR 101.81). Yet, existing study designs of interventions were primarily designed to control energy, MUFA, and/or macronutrient intake (Table 4). Fiber intake could be used among interventions with a free-feeding design or observational trials as an additional measure to statistically control for.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review addresses many of the limitations present in previous publications, most importantly by focusing the review to studies wherein effects of intake could be isolated to quantifiable intake of avocado. Although omitting studies with multi-food interventions reduced the amount of in-scope literature, it enabled the identification of research from which causal relationships between avocado intake and health could be inferred. Although we did not systematically perform an umbrella review, we identified 36 articles (2, 3, 10, 43, 45–57, 62, 63, 65–67, 69, 77–89) that were not described in recent systematic reviews (12–16, 28, 29), indicating this review comprehensively captured the body of literature and is distinct from other systematic reviews. Second, the translation of studies in Spanish allowed inclusion of several studies (59, 60, 67, 77, 87), which is particularly critical given the cultural importance of avocado intake in Latin American populations. The use of backward citation screening identified two observational studies that were not identified from database searching (49, 84), both of which used terms related to fruit and vegetable intake but not related to avocado or MUFA in the abstract. This finding highlights the possibility that not all possible observational studies were identified, specifically, those articles that only report avocado intake in full-texts or supplementary data. Such articles will likely not be found by database searching unless using a very broad search strategy including fruit and vegetable terms and full-text review of epidemiological research with secondary outcomes on avocado intake, requiring a substantially larger screening process.

Conclusions and future directions

We identified 58 articles comprising 45 unique studies on avocado intake and health. Research has been well-replicated among participants living in the Americas, in adults with high blood lipid concentrations, and on anthropometric and cardiovascular outcomes. Future studies to overcome the limiting factors of the research include: greater study of participants outside of the Americas across a wider age range, designs of interventions or epidemiological analyses that account for dietary compensation or other dietary patterns, and evaluation of the dose–response pattern. Such studies would help build causal evidence delineating whether avocado or the broader dietary patterns are responsible for the effects observed. Specific gaps in the research are listed below.

There has been no research conducted in European or Asian regions (except Indonesia), with most research conducted in the U.S. and Mexico, typically related to cardiovascular outcomes.

Adolescent or younger and senior populations have been understudied, especially with respect to interventions.

Most studies sampled populations with elevated blood lipid concentrations (likely endemic to the general population), with a minority exclusively investigating the impact of avocado intake in dyslipidemic populations.

There is a translational gap between observational and intervention studies according to the analyzed population’s age, weight, amount of avocado consumed, and endpoints measured. Further, some observational studies did not account for all sources of avocado intake.

There is limited understanding of dietary compensation from avocado intake. Although several trials provided avocado in a free-feeding context, and numerous trials either did not measure, analyze, or report nutrient intakes.

There were almost no dose–response evaluations in controlled trials.

Although the number of interventions appears high, over half were conducted in short interventions of one month or less. Relatively little is known about the effects of avocado intake for longer than one month.

The full results are detailed in a publicly available interactive evidence map. The resource should help educate the broader community on the available research and enable more efficient and informed methods of planning future research.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. Protocols, Supplementary material, and raw data are freely available at https://github.com/Traverse-Science/Avocado-Evidence-Map.

Author contributions

SF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TP: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. RF: Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AV: Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – review & editing. CW: Writing – review & editing. PS: Writing – review & editing. LD: Writing – review & editing. JK: Writing – review & editing. NF: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Avocado Nutrition Center (ANC) funded the research and author NAF (employee thereof) edited manuscript drafts and has read and approved the final version. NAF had no involvement in study design, collection, or analysis of the data.

Conflict of interest

SF has ownership in Traverse Science. TP, SF, and RF are employees of Traverse Science. NF is an employee of Avocado Nutrition Center. PS is the founder of SP Nutraceuticals Inc. AV, MM, CW, PS, LD, and JK serve as advisory board members of Avocado Nutrition Center.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1488907/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^https://scite.ai/home, last accessed 05/09/2024.

2.^https://sr-accelerator.com/#/spidercite, last accessed 04/02/2024.

4.^Available at: www.covidence.org.

References

1.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th Edn. Available online at: http://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

2.

PetersenKSSmithSLichtensteinAHMatthanNRLiZSabateJet al. One avocado per day as part of usual intake improves diet quality: exploratory results from a randomized controlled trial. Curr Dev Nutr. (2024) 8:102079. doi: 10.1016/j.cdnut.2024.102079

3.

O’NeilCNicklasTFulgoniV. Avocado consumption by adults is associated with better nutrient intake, diet quality, and some measures of adiposity: National Health and nutrition examination survey, 2001-2012. Intern Med Rev. (2017) 3:422. doi: 10.18103/imr.v3i4.422

4.

DreherMLFordNA. A comprehensive critical assessment of increased fruit and vegetable intake on weight loss in women. Nutrients. (2020) 12:1919. doi: 10.3390/nu12071919

5.

FordNASpagnuoloPKraftJBauerE. Nutritional composition of Hass avocado pulp. Food Secur. (2023) 12:2516. doi: 10.3390/foods12132516

6.

Alvizouri-MuñozMCarranza-MadrigalJHerrera-AbarcaJEChávez-CarbajalFAmezcua-GastelumJL. Effects of avocado as a source of monounsaturated fatty acids on plasma lipid levels. Arch Méd Res. (1992) 23:163–7. PMID:

7.

DreherMLDavenportAJ. Hass avocado composition and potential health effects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2013) 53:738–50. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.556759

8.

EdwardsCGWalkAMThompsonSVReeserGEErdmanJWBurdNAet al. Effects of 12-week avocado consumption on cognitive function among adults with overweight and obesity. Int J Psychophysiol. (2020) 148:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2019.12.006

9.

ScottTMRasmussenHMChenOJohnsonEJ. Avocado consumption increases macular pigment density in older adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Nutrients. (2017) 9:919. doi: 10.3390/nu9090919

10.

HenningSMGuzmanJBThamesGYangJTsengCHeberDet al. Avocado consumption increased skin elasticity and firmness in women - a pilot study. J Cosmet Dermatol. (2022) 21:4028–34. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14717

11.

MensinkRPZockPLKesterADKatanMB. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. (2003) 77:1146–55. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1146

12.

MahmassaniHAAvendanoEERamanGJohnsonEJ. Avocado consumption and risk factors for heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutrition. (2018) 107:523–36. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqx078

13.

James-MartinGBrookerPGHendrieGAStonehouseW. Avocado consumption and cardiometabolic disease risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2022) 124:233–248.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2022.12.008

14.

OkobiOEOdomaVAOkunromadeOLouise-OluwasanmiOItuaBNdubuisiCet al. Effect of avocado consumption on risk factors of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Cureus. (2023) 15:e41189. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41189

15.

PeouSMilliard-HastingBShahSA. Impact of avocado-enriched diets on plasma lipoproteins: a meta-analysis. J Clin Lipidol. (2016) 10:161–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.10.011

16.

ConceiçãoARFraizGMRochaDMUPBressanJ. Can avocado intake improve weight loss in adults with excess weight? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Res. (2022) 102:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2022.03.005

17.

SchoeneckMIggmanD. The effects of foods on LDL cholesterol levels: a systematic review of the accumulated evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2021) 31:1325–38. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2020.12.032

18.

ImamuraFMichaRWuJHYde Oliveira OttoMCAbioyeAMozaffarianD. Effects of saturated fat, polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, and carbohydrate on glucose-insulin homeostasis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomised controlled feeding trials. PLoS Med. (2016) 13:e1002087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002087

19.

SpillMKEnglishLKRaghavanRCallahanEGüngörDKingshippBet al. Perspective: USDA nutrition evidence systematic review methodology: grading the strength of evidence in nutrition- and public health-related systematic reviews. Adv Nutr. (2022) 13:982–91. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmab147

20.

TriccoACLillieEZarinWO’BrienKKColquhounHLevacDet al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/m18-0850

21.

BousheyCArdJBazzanoLHeymsfieldSMayer-DavisESabatéJet al. Dietary patterns and growth, size, body composition, and/or risk of overweight or obesity: a systematic review. Alexandria, VA: USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (2020).

22.

WangLBordiPLFlemingJAHillAMKris-EthertonPM. Effect of a moderate fat diet with and without avocados on lipoprotein particle number, size and subclasses in overweight and obese adults: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Hear Assoc. (2015) 4:e001355. doi: 10.1161/jaha.114.001355

23.

WangLTaoLHaoLStanleyTHHuangK-HLambertJDet al. A moderate-fat diet with one avocado per day increases plasma antioxidants and decreases the oxidation of small, dense LDL in adults with overweight and obesity: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. (2020) 150:276–84. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz231

24.

HannonBAEdwardsCGThompsonSVReeserGEBurdNAHolscherHDet al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms related to lipoprotein metabolism are associated with blood lipid changes following regular avocado intake in a randomized control trial among adults with overweight and obesity. J Nutr. (2020) 150:1379–87. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa054

25.

KhanNAEdwardsCGThompsonSVHannonBABurkeSKWalkADMet al. Avocado consumption, abdominal adiposity, and Oral glucose tolerance among persons with overweight and obesity. J Nutr. (2021) 151:2513–21. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab187

26.

ThompsonSVBaileyMATaylorAMKaczmarekJLMysonhimerAREdwardsCGet al. Avocado consumption alters gastrointestinal Bacteria abundance and microbial metabolite concentrations among adults with overweight or obesity: a randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. (2021) 151:753–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxaa219

27.

HeskeyCOdaKSabatéJ. Avocado intake, and longitudinal weight and body mass index changes in an adult cohort. Nutrients. (2019) 11:691. doi: 10.3390/nu11030691

28.

CaldasAPSChavesLOSilvaLLDMoraisDDCDe AlfenasR. Mechanisms involved in the cardioprotective effect of avocado consumption: a systematic review. Int J Food Prop. (2017) 20:1675–1685:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10942912.2017.1352601

29.

TabeshpourJRazaviBMHosseinzadehH. Effects of avocado (Persea americana) on metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive systematic review. Phytother Res. (2017) 31:819–37. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5805

30.

BerryEEisenbergSFriedlanderYHaratsDKaufmannNNormanYet al. Effects of diets rich in monounsaturated fatty acids on plasma lipoproteins—the Jerusalem nutrition study. II monounsaturated fatty acids vs carbohydrates. Am J Clin Nutr. (1992) 56:394–403. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.394

31.

BerryEEisenbergSHaratzDFriedlanderYNormanYKaufmannNet al. Effects of diets rich in monounsaturated fatty acids on plasma lipoproteins—the Jerusalem nutrition study: high MUFAs vs high PUFAs. Am J Clin Nutr. (1991) 53:899–907. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.899

32.

Lerman-GarberIIchazo-CerroSZamora-GonzálezJCardoso-SaldañaGPosadas-RomeroC. Effect of a high-monounsaturated fat diet enriched with avocado in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. (1994) 17:311–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.4.311

33.

Lerman-GarberIGulias-HerreroAPalmaMEVallesVEGuerreroLAGarciaEGet al. Response to high carbohydrate and high monounsaturated fat diets in hypertriglyceridemic non-insulin dependent diabetic patients with poor glycemic control. Diabet Nutr Metabol Clin Exp. (1995) 8:339–45.

34.

GrantWC. Influence of avocados on serum cholesterol. P Soc Exp Biol Med. (1960) 104:45–7. doi: 10.3181/00379727-104-25722

35.

MeyerBJDeBEJPBrownJMMBielerEUMeyerACGreyPC. The effect of a predominantly fruit diet on athletic performance. Plant Foods Man. (1975) 1:233–9. doi: 10.1080/03062686.1975.11904174

36.

Diaz-PerillaMToroCA. Efecto de la adición de aguacate a la alimentación habitual sobre los niveles de lípidos en personas con dislipidemia. Univ Sci. (2004) 9:49–58.

37.

Olmedilla-AlonsoBRodríguez-RodríguezEBeltrán-de-MiguelBSánchez-PrietoMEstévez-SantiagoR. Changes in lutein status markers (serum and Faecal concentrations, macular pigment) in response to a lutein-rich fruit or vegetable (three pieces/day) dietary intervention in Normolipemic subjects. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3614. doi: 10.3390/nu13103614

38.

GardnerCDOffringaLCHartleJCKapphahnKCherinR. Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults and adults with obesity: a randomized pilot trial. Obesity. (2016) 24:79–86. doi: 10.1002/oby.21331

39.

Muñoz-PérezDMGonzález-CorreaCHMuñozEYASánchez-GiraldoMCarmona-HernándezJCLópez-MirandaJet al. Effect of 8-week consumption of a dietary pattern based on fruit, avocado, whole grains, and trout on postprandial inflammatory and oxidative stress gene expression in obese people. Nutrients. (2023) 15:306. doi: 10.3390/nu15020306

40.

Muñoz-PérezDMGonzalez-CorreaCHAstudillo-MuñozEYPorras-HurtadoGLSanchez-GiraldoMLopez-MirandaJet al. Alternative foods in cardio-healthy dietary models that improve postprandial Lipemia and Insulinemia in obese people. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2225. doi: 10.3390/nu13072225

41.

TaylorMKBurnsJM. An experimental ketogenic diet for Alzheimer disease was nutritionally dense and rich in vegetables and avocado. Curr Dev Nutr. (2019) 3:nzz003. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz003

42.

SousaFHValentiVEPereiraLCBuenoRRPratesSAkimotoANet al. Avocado (Persea americana) pulp improves cardiovascular and autonomic recovery following submaximal running: a crossover, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:10703. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67577-3

43.

MonroeKRMurphySPHendersonBEKolonelLNStanczykFZAdlercreutzHet al. Dietary Fiber intake and endogenous serum hormone levels in naturally postmenopausal Mexican American women: the multiethnic cohort study. Nutr Cancer. (2007) 58:127–35. doi: 10.1080/01635580701327935

44.

ChengFWRodríguez-RamírezSShamah-LevyTPérez-TepayoSFordNA. Association between avocado consumption and diabetes in Mexican adults: results from the 2012, 2016, and 2018 Mexican National Health and nutrition surveys. J Acad Nutr Diet. (2024) 125:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2024.04.012

45.

WoodACGoodarziMOSennMKGadgilMDGracaGAllisonMAet al. Associations between Metabolomic biomarkers of avocado intake and Glycemia in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Nutr. (2023) 153:2797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.07.013

46.

ChengFWFordNAWoodACTracyR. Avocado consumption and markers of inflammation: results from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur J Nutr. (2023) 62:2105–13. doi: 10.1007/s00394-023-03134-8

47.

PachecoLSLiYRimmEBMansonJESunQRexrodeKet al. Avocado consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease in US adults. J Am Hear Assoc. (2022) 11:e024014. doi: 10.1161/jaha.121.024014

48.

EricssonCIPachecoLSRomanos-NanclaresAEcsedyEGiovannucciELEliassenAHet al. Prospective study of avocado consumption and Cancer risk in U.S Men and Women. Cancer Prev Res. (2022) 16:211–8. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.capr-22-0298

49.

BorgiLMurakiISatijaAWillettWCRimmEBFormanJP. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the incidence of hypertension in three prospective cohort studies. Hypertension. (2016) 67:288–93. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.115.06497

50.

FulgoniVLDreherMDavenportAJ. Avocado consumption is associated with better diet quality and nutrient intake, and lower metabolic syndrome risk in US adults: results from the National Health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 2001–2008. Nutr J. (2013) 12:1. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-1

51.

ChengFWFordNATaylorMK. US older adults that consume avocado or guacamole have better cognition than non-consumers: National Health and nutrition examination survey 2011–2014. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:746453. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.746453

52.

AllenTSDoedeALKingCMBPachecoLSTalaveraGADenenbergJOet al. Nutritional avocado intervention improves physical activity measures in Hispanic/Latino families: a cluster RCT. AJPM Focus. (2023) 2:100145. doi: 10.1016/j.focus.2023.100145

53.

HaddadEWienMOdaKSabatéJ. Postprandial gut hormone responses to Hass avocado meals and their association with visual analog scores in overweight adults: a randomized 3 × 3 crossover trial. Eat Behav. (2005) 31:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.08.001

54.

ZhuLHuangYEdirisingheIParkEBurton-FreemanB. Using the avocado to test the satiety effects of a fat-Fiber combination in place of carbohydrate energy in a breakfast meal in overweight and obese men and women: a randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. (2019) 11:952. doi: 10.3390/nu11050952

55.

PachecoLSBradleyRDAndersonCAMAllisonMA. Changes in biomarkers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) upon access to avocados in Hispanic/Latino adults: secondary data analysis of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. (2022) 14:2744. doi: 10.3390/nu14132744

56.

VanEveryHPachecoLSSunEAllisonMAGaoX. The impact of avocado intake on anthropometric measures among Hispanic/Latino children and adolescents: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2023) 56:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.04.020

57.

KimESAdrikoMAidahWOsekuKCLokureDSabapathyKet al. The impact of dual- versus single-dosing and fatty food co-administration on albendazole efficacy against hookworm among children in Mayuge district, Uganda: results from a 2x2 factorial randomised controlled trial. PLoS Neglected Trop Dis. (2023) 17:e0011439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0011439

58.

Carranza-MadrigalJHerrera-AbarcaJEAlvizouri-MunozMAlvarado-JimenezMDRChavez-CarbajalF. Effects of a vegetarian diet vs. a vegetarian diet enriched with avocado in hypercholesterolemic patients. Arch Med Res. (1997) 28:537. Available at: https://europepmc.org/article/med/9428580–41.

59.

CarranzaJAlvizouriMAlvaradoMRChávezFGómezMHerreraJE. Effects of avocado on the level of blood lipids in patients with phenotype II and IV dyslipidemias. Arch del Inst Cardiol Mex. (1995) 65:342–8.

60.

Anderson-VazquezHESoralysCRosaLCoromotoGIL. Effect of consumption of avocado (Persea Americana mill) on the lipid profile in adults with dyslipidemia. An Venez Nutr. (2009) 22:84–9.

61.

LedesmaRLMunariACFDomínguezBCHMontalvoSCLunaMHHJuárezCet al. Monounsaturated fatty acid (avocado) rich diet for mild hypercholesterolemia. Arch Méd Res. (1996) 27:519–23.

62.

ProbstYGuanVNealeE. Avocado intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in a representative survey of Australians: a secondary analysis of the 2011–2012 national nutrition and physical activity survey. Nutr J. (2024) 23:12. doi: 10.1186/s12937-024-00915-7

63.

Segovia-SiapcoGPaalaniMOdaKPribisPSabatéJ. Associations between avocado consumption and diet quality, dietary intake, measures of obesity and body composition in adolescents: the teen food and development study. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4489. doi: 10.3390/nu13124489

64.

LiZWongAHenningSMZhangYJonesAZerlinAet al. Hass avocado modulates postprandial vascular reactivity and postprandial inflammatory responses to a hamburger meal in healthy volunteers. Food Funct. (2013) 4:384–91. doi: 10.1039/c2fo30226h

65.

WienMHaddadEOdaKSabatéJ. A randomized 3x3 crossover study to evaluate the effect of Hass avocado intake on post-ingestive satiety, glucose and insulin levels, and subsequent energy intake in overweight adults. Nutr J. (2013) 12:155. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-155

66.

KopecRECooperstoneJLSchweiggertRMYoungGSHarrisonEHFrancisDMet al. Avocado consumption enhances human postprandial Provitamin a absorption and conversion from a novel high–β-carotene tomato sauce and from carrots. J Nutr. (2014) 144:1158–66. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.187674

67.

Raya-FariasACarranza-MadrigalJCampos-PerezYCortes-RojoCSanchez-PerezTA. Avocado inhibits oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction induced by the intake of a hamburger in patients with metabolic syndrome. Med Int Méx. (2018) 34:840–7. doi: 10.24245/mim.v34i6.2117

68.

UnluNZBohnTClintonSKSchwartzSJ. Carotenoid absorption from salad and salsa by humans is enhanced by entrye addition of avocado or avocado oil. J Nutr. (2004) 135:431–6. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.3.431

69.

MongeASternDCortés-ValenciaACatzín-KuhlmannALajousMDenova-GutiérrezE. Avocado consumption is associated with a reduction in hypertension incidence in Mexican women. Br J Nutr. (2023) 129:1976–83. doi: 10.1017/s0007114522002690

70.

Mayer-DavisELeidyHMattesRNaimiTNovotnyRSchneemanBet al. Beverage consumption and growth, size, body composition, and risk of overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Alexandria, VA: USDA Nutrition Evidence Systematic Review (2020).

71.

PachecoLSBradleyRDDenenbergJOAndersonCAMAllisonMA. Effects of different allotments of avocados on the nutritional status of families: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4021. doi: 10.3390/nu13114021

72.

LichtensteinAHKris-EthertonPMPetersenKSMatthanNRBarnesSVitolinsMZet al. Effect of incorporating 1 avocado per day versus habitual diet on visceral adiposity: a randomized trial. J Am Hear Assoc. (2022) 11:e025657. doi: 10.1161/jaha.122.025657

73.

ColquhounDMooresDSomersetSHumphriesJ. Comparison of the effects on lipoproteins and apolipoproteins of a diet high in monounsaturated fatty acids, enriched with avocado, and a high-carbohydrate diet. Am J Clin Nutr. (1992) 56:671–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.4.671

74.

HenningSMYangJWooSLLeeR-PHuangJRasmusenAet al. Hass avocado inclusion in a weight-loss diet supported weight loss and altered gut microbiota: a 12-week randomized, parallel-controlled trial. Curr Dev Nutr. (2019) 3:nzz068. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz068

75.

Hass Avocado Board. (2024). Global Trade Reports. Available online at: https://hassavocadoboard.com/global-trade-reports/?region=EU&weight=kgs (Accessed August 29, 2024)

76.

CarranzaJAlvizouri-MunozMRodriguez-BarronACamposYHerreraAHerreraJet al. Lower quantities of avocado as daily source of monounsaturated fats: effect on serum and membrane lipids, endothelial function, platelet aggregation and C-reactive protein in patients with metabolic syndrome. Medicina Interna de México. (2004) 20:409–16.

77.

BallotDBaynesRDBothwellTHGilloolyMMacfarlaneJMacphailAPet al. The effects of fruit juices and fruits on the absorption of iron from a rice meal. Br J Nutr. (1987) 57:331–43. doi: 10.1079/bjn19870041

78.

CarrisNWMhaskarRCoughlinEBraceyETipparajuSMReddyKRet al. Association of Common Foods with inflammation and mortality: analysis from a large prospective cohort study. J Med Food. (2024) 27:267–74. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2023.0203

79.

ChengFWParkS-YHaimanCAWilkensLRMarchandLLFordNA. Avocado and guacamole consumption and colorectal Cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Nutr Cancer. (2024) 76:372–8. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2024.2320950

80.

GuanVXNealeEPProbstYC. Consumption of avocado and associations with nutrient, food and anthropometric measures in a representative survey of Australians: a secondary analysis of the 2011–2012 National Nutrition and physical activity survey. Br J Nutr. (2022) 128:932–9. doi: 10.1017/s0007114521003913

81.

JacksonMDWalkerSPSimpson-SmithCMLindsayCMSmithGMcFarlane-AndersonNet al. Associations of whole-blood fatty acids and dietary intakes with prostate cancer in Jamaica. Cancer Causes Control. (2012) 23:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9850-4

82.

KhorAGrantRTungCGuestJPopeBMorrisMet al. Postprandial oxidative stress is increased after a phytonutrient-poor food but not after a kilojoule-matched phytonutrient-rich food. Nutr Res. (2014) 34:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.04.005

83.

MaoXChenCXunPDaviglusMLSteffenLMJacobsDRet al. Intake of vegetables and fruits through Young adulthood is associated with better cognitive function in midlife in the US general population. J Nutr. (2019) 149:1424–33. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz076

84.

MoralesGBalboa-CastilloTFernández-RodríguezRGarrido-MiguelMGuidoniCMSirtoliRet al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in Chilean university students: a cross-sectional study. Cad Saúde Pública. (2023) 39:e00206722. doi: 10.1590/0102-311xen206722

85.

ParkEEdirisingheIBurton-FreemanB. Avocado fruit on postprandial markers of cardio-metabolic risk: a randomized controlled dose response trial in overweight and obese men and women. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1287. doi: 10.3390/nu10091287

86.

Prado-ZavalaLMCampos-PerezYAyala-AcevesFCarranza-MadrigalJ. Avocado has better endothelial effects than other foods in apparently healthy young men. Med Interna México. (2020) 36:476–84. doi: 10.24245/mim.v36i4.3238

87.

SennMKGoodarziMORameshGAllisonMAGraffMYoungKLet al. Associations between avocado intake and measures of glucose and insulin homeostasis in Hispanic individuals with and without type 2 diabetes: results from the Hispanic community health study/study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2023) 33:2428–39. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2023.08.002

88.

UtariRSetyaningsihYSuwondoA. The effect of giving avocados (Persea americana mill) and guava (Psidium guajava Linn) on hemoglobin levels in traditional Rice farmers. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. (2020) 448:012027. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/448/1/012027

89.

Carranza-MadrigalJAlvizouri-MunozMAbarcaJEHCarbajalFC. Avocado as source of monounsaturated fatty acid: its effects in serum lipids, glucose metabolism and rheology in patients with type 2 diabetes. Medicina Interna de México. (2008) 24:267–72.

Summary

Keywords

Persea americana, public health, obesity, cardiovascular health, dietary patterns

Citation

Fleming SA, Paul TL, Fleming RAF, Ventura AK, McCrory MA, Whisner CM, Spagnuolo PA, Dye L, Kraft J and Ford NA (2025) Exploring avocado consumption and health: a scoping review and evidence map. Front. Nutr. 12:1488907. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1488907

Received

30 August 2024

Accepted

13 January 2025

Published

10 February 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Gabriele Rocchetti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Reviewed by

Eduard Baladia, Academia Española de Nutrición y Dietética, Spain

Elizabeth J. Johnson, Tufts University, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Fleming, Paul, Fleming, Ventura, McCrory, Whisner, Spagnuolo, Dye, Kraft and Ford.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stephen A. Fleming, engage@traversescience.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.