Abstract

Background:

Insulin-like Growth Factor I (IGF-I) and Vitamin D are crucial for growth and metabolism, with their levels declining with age. However, their mutual interactions and contributions to body composition remain unclear.

Objectives:

To examine the relationships between IGF-I, Vitamin D, and body composition in geriatric outpatients, and to test the mediational role of IGF-I in the association between Vitamin D and Fat-Free Mass (FFM).

Methods:

One hundred thirty patients were eligible at the Geriatric Outpatient Clinic at the Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. Multimorbidity was evaluated with the Cumulative Illness Rating scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G). Body composition was measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis. Complete blood count, metabolic panel, IGF-I, and 25(OH) Vitamin D were assessed.

Results:

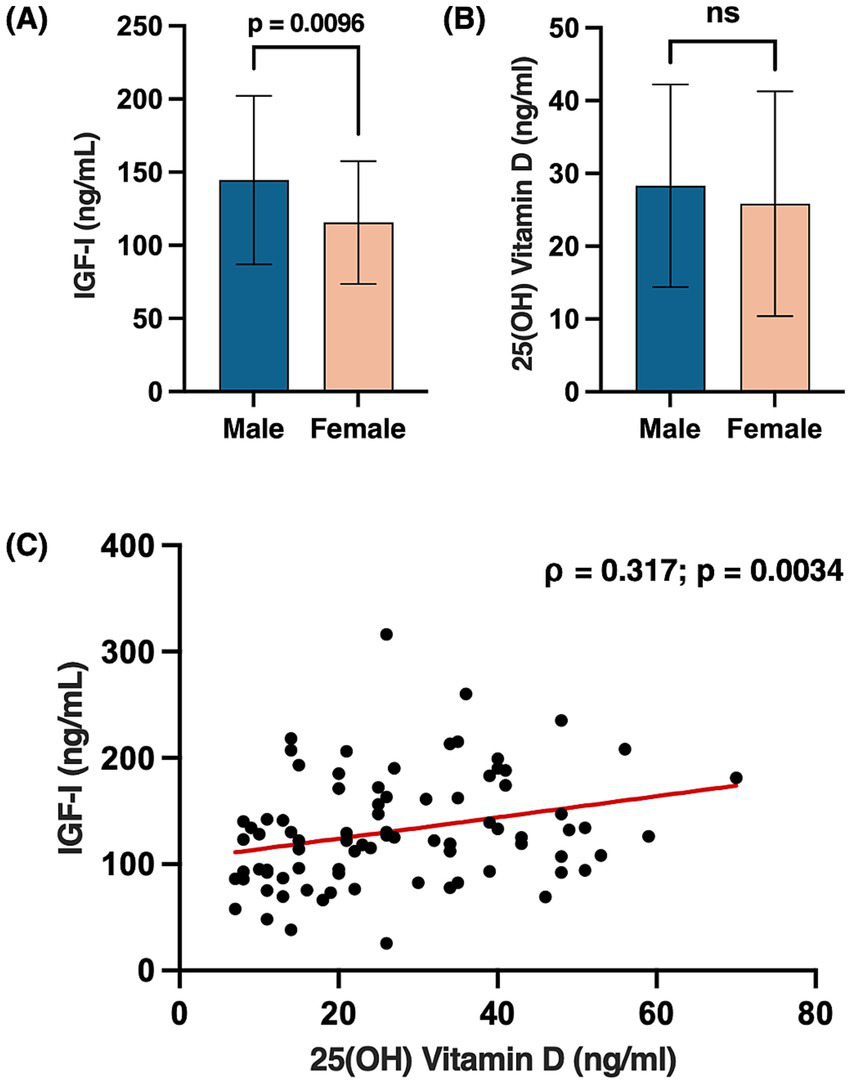

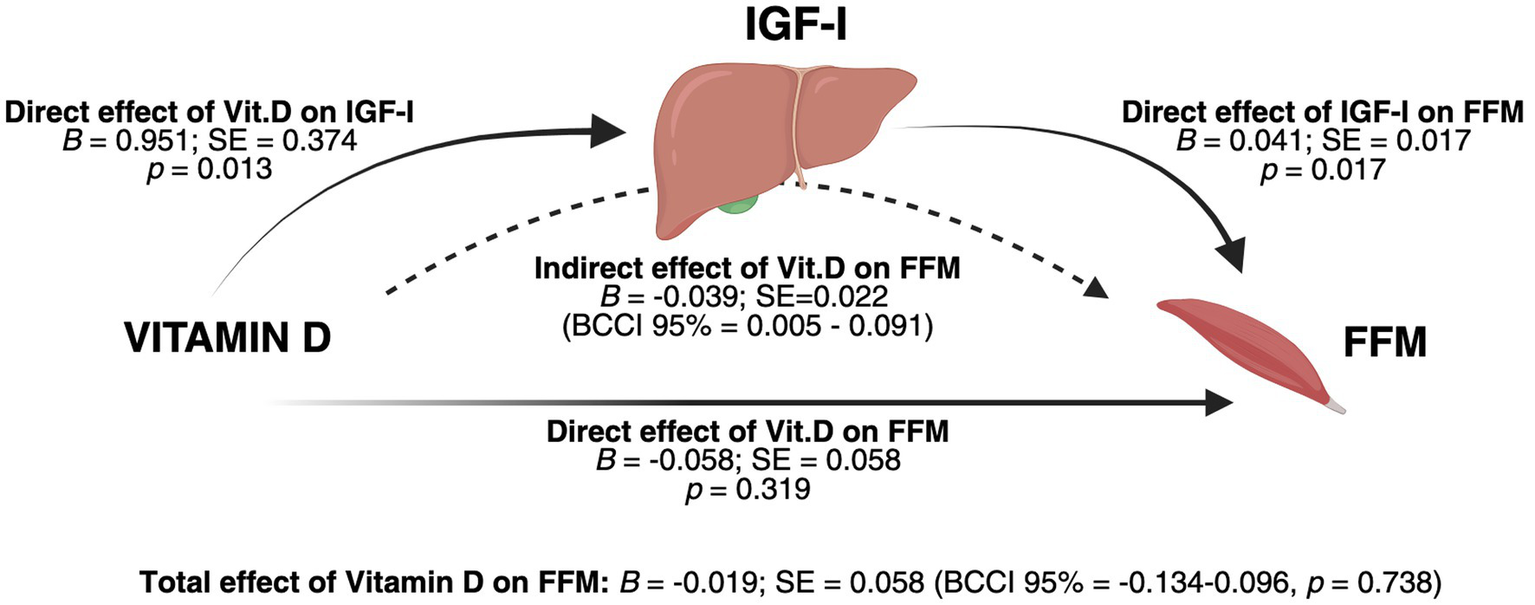

Ninety-one patients were included in the analysis. Mean age was 74.4 ± 7.2 years; 50.5% female. Mean BMI was 28 kg/m2 ± 3.9. Mean CIRS-G total score was 14.14 ± 4.1, and Severity Index (SI) was 1.16 ± 0.32. Median IGF-I was 122.0 ng/mL (IQR, 69.8) with higher levels in males compared to females (p = 0.0096). Mean 25(OH) Vitamin D was 27.04 ng/mL ± 14.69 with no significant sex difference. Level of 25(OH) Vitamin D positively correlated with IGF-I (ρ = 0.317, p = 0.003), while no correlation was found between Vitamin D and body composition parameters. Patients with higher IGF-I exhibited higher Total Body Water (TBW) (p = 0.024), Intracellular Water (ICW) (p = 0.018), FFM (p = 0.022), and Muscle Mass (MM) (p = 0.017), Body Cell Mass (BCM) (p = 0.046). Linear regression analysis showed that IGF-I and male sex predicted FFM (B = 13.933, p < 0.001; B = 0.040; p = 0.034; respectively). The mediation analysis confirmed no significant direct effect of Vitamin D on FFM (direct effect, B = −0.058, p = 0.319, 95% CI: −0.175, 0.058); however, the effect was significant when mediated by IGF-I (indirect effect, B = 0.039, SE = 0.022, 95% CI: 0.005, 0.091).

Conclusion:

These findings provide further evidence of a positive correlation between IGF-I and lean body mass and suggest that IGF-I may mediate the physiological effect of Vitamin D on FFM, highlighting their potential roles in assessing pre-frailty and personalizing nutrition interventions.

1 Introduction

Aging is a complex phenomenon characterized by the dynamic interplay among multiple biological processes, including alterations in mitochondrial function, loss of proteostasis, and dysregulated nutrient-sensing (1, 2). Over time, these mechanisms contribute to phenotypic changes such as modifications in body composition, which may increase the risk for sarcopenia and frailty (3–6). Reduced physical activity and age-related changes to metabolic and hormonal responses may further promote the loss of muscle mass (7–11). Insulin-like Growth Factor I (IGF-I) is a key regulator of growth and development and plays an essential role in the anabolic pathways (12, 13). IGF-I is primarily produced in the liver, where it mediates the actions of Growth Hormone (GH) (14, 15). Furthermore, IGF-I exerts autocrine and paracrine effects in muscle cells, promoting cell differentiation, survival, and repair (16–18). Upon binding to its transmembrane receptors, which consist of two extracellular α-subunits and two transmembrane β-subunits with intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, similar to other hormones (19), IGF-I modulates several intracellular signaling cascades (20, 21). The PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK pathways modulate protein synthesis (22), muscle hypertrophy (23), and satellite cell activation (24, 25), contributing to muscle homeostasis.

IGF-I levels fluctuate throughout the lifespan, beginning with low concentrations in infancy, peaking during adolescence, and tending to decline in adulthood (26, 27). However, the biological role of IGF-I in the aging process is complex, with its effects on health outcomes influenced by metabolic changes and the presence of chronic illnesses (28–30). For example, low IGF-I has been associated with low HDL cholesterol (31), and reduced insulin sensitivity (32), both of which are known risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (33–35). Additionally, low serum IGF-I has been linked to sarcopenia in both animal models and human studies (36, 37). In contrast, higher IGF-I levels have been associated with an increased risk of certain forms of cancer (28, 38).

A large prospective study involving over 7,000 individuals, stratified by age, described a U-shaped relationship between IGF-I levels and the risk of cancer, CVD, and all-cause mortality, suggesting that both low and high circulating IGF-I levels may increase the risk of such conditions (39). IGF-I levels are also influenced by factors such as physical activity and nutrient intake, further contributing to variability in research findings (40–44). In this regard, previous studies suggest a correlation between Vitamin D and IGF-I (45–48), although randomized controlled trials have yielded inconsistent results (49–51). Furthermore, the mechanisms underlying these observations remain elusive. Indeed, hepatocytes do not consistently express the nuclear Vitamin D receptor (VDR), while non-parenchymal liver cells have been shown to express VDR (52), suggesting a potential role of Vitamin D in modulating IGF-I bioavailability (53). Moreover, evidence suggests that IGF-I may stimulate the enzyme 1-α-hydroxylase in the kidneys, which converts 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25 OH Vitamin D) into its active form, calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D) (54, 55). In addition to the described effect of IGF-I on body composition, Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with depressive symptoms (56), frailty (57), muscle weakness (58), and an increased risk for falls (59, 60). Given the age-associated decline of both IGF-I and Vitamin D (27, 61), this study aimed to (i) examine the relationships between IGF-I, Vitamin D, and parameters of body composition; (ii) explore the clinical variables associated with IGF-I levels; and (iii) test IGF-I as a mediator in the relationship between Vitamin D and FFM in geriatric outpatients.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and criteria

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Geriatric Outpatient Clinic at Policlinico Umberto I University Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy. Participants with the following criteria were considered eligible: age ≥65 years, written informed consent to participate in the study, no contraindications to body composition analysis according to the device manufacturer instructions, and independence in both the activities of daily living (ADL) and the instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Exclusion criteria were: a body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2, a history of alcohol misuse (more than 7 standard drinks per week for women and more than 14 standard drinks per week for men), alterations in liver enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) beyond the normal reference range, an estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) < 50 mL/min/1.73 m2, reported weight fluctuation in the past 3 months (>10% of total body weight), poorly controlled T2DM or individuals receiving insulin therapy, and history of cancer treated with radiation or chemotherapy in the past 5 years. Patients with acute medical conditions were excluded. A total of 130 patients were consecutively enrolled. IGF-I measurements were completed for 92 patients due to an unexpected shortage of reagents in the laboratories. One patient was excluded for not meeting the study criteria, leading to 91 patients in the final analysis.

2.2 Assessments

A Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) was performed for each participant, which included a detailed clinical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, and a review of all relevant diagnostics. The Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (CIRS-G) was then completed and reviewed by two physicians. Any discrepancies in the CIRS-G scores were resolved with a third physician. For the analysis, the CIRS-G was calculated excluding the psychiatric item (item 14), resulting in a 13-item scale. Physical activity levels were evaluated using the self-reported Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE). All patients provided their informed consent, and the study was approved by the local board of Sapienza University of Rome and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2.1 Body composition

After the initial visit, enrolled participants returned to the clinic for anthropometric measurements (i.e., weight, height, and waist circumference). Body composition was assessed using bioimpedance analysis (BIA 101, AKERN, Italy), conducted between 8:30 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. with participants fasted overnight. BIA was performed following a 5-min rest in the supine position, with the participant’s upper limbs abducted at a 30° angle and lower limbs at a 45° angle. Bioelectrical data and body composition parameters were then collected, and reported as follows: Total Body Water (TBW) in liters, Intra- and Extracellular Water (ICW and ECW, respectively) in liters, Fat-Free mass (FFM) in kilograms, Muscle Mass (MM) in kilograms, Body Cell Mass (BCM) in kilograms, and Fat Mass (FM) in kilograms.

2.2.2 Blood tests and biomarkers

Blood samples were collected from the participants and sent to a local laboratory. All samples were handled and analyzed according to standard practices for measuring hematological parameters, including complete blood count, serum electrolytes, metabolic panel, albumin, folate, Vitamin B12, 25(OH) Vitamin D, IGF-I, and C-reactive protein (CRP).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 29.0.2; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies or percentages, while continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), depending on the distribution of the data. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to assess associations between variables. To compare numerical data between groups, either Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used, based on the normality of the data distribution. All tests were two-tailed, and a p-values less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To investigate the factors independently associated with FFM, a multivariate linear regression model was constructed using the variables of interest. Prior to analysis, the fundamental assumptions of linear regression were assessed. To test the hypothesis of IGF-I as a mediator in the relationship between Vitamin D and FFM, a mediation analysis was conducted using the model described by Preacher and Hayes (62). Specifically, we employed Model 4 of the SPSS PROCESS Macro to test the indirect effect of the independent variable [25(OH) Vitamin D] on the dependent variable (FFM) through the mediator (IGF-I) (63). The analysis utilized 5,000 bootstrap samples to estimate the indirect effect and construct 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mediation effect. Original figures were prepared using GraphPad Prism (version 10.4.1 for Mac, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, United States) and BioRender.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

The analysis included 91 patients (50.5% women). The mean age of participants was 74.4 ± 7.2 years, and the mean BMI was 28.0 ± 3.9 kg/m2. The prevalence of hypertension was 76.9%, while dyslipidemia and Impaired Fasting Glucose (IFG)/T2DM were present in 59.3 and 28% of the participants, respectively. Atrial fibrillation, Coronary Heart Disease (CHD), and history of Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIA) were each present in 6.5% of participants. The mean CIRS-G score was 14.4 ± 4.1 while the severity index was 1.16 ± 0.32, suggesting a moderate level of multimorbidity. Clinical characteristics of patients are reported in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1

| Parameters | Participants (N = 91) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 74.4 ± 7.2 |

| Females, n (%) | 46 (50.5) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28 ± 3.9 |

| Body weight, kg | 73 ± 12.5 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 99.2 ± 10.2 |

| Blood count | |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.8 ± 1.23 |

| Lymphocytes,103/μL | 2 ± 0.83 |

| Platelets, 103/μL | 223 (74.5) |

| Kidney and liver function | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.88 ± 0.2 |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 81.67 ± 19.4 |

| AST, U/L | 21.3 ± 11.2 |

| ALT, U/L | 19.5 ± 16 |

| Hormones, metabolism and inflammation | |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 94.4 ± 17.7 |

| Fasting Insulin, μUI/mL | 9.3 (7.5) |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.6 (0.53) |

| IGF-I, ng/mL | 122 (69.8) |

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 196.5 ± 33.8 |

| LDL, mg/dL | 117.3 ± 33.3 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 58 ± 13 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 111 ± 40 |

| CRP, μg/L | 2000 (2525) |

| Nutrition and physical activity | |

| Total Protein, g/dL | 71.4 ± 7.9 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.5 ± 0.2 |

| Folate (ng/mL) | 8 (4.1) |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 322 (246) |

| 25(OH) Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 27.04 ± 14.69 |

| PASE score | 116 ± 58.96 |

Patient characteristics and blood parameters.

Data are presented as mean (± SD) or median (IQR). Glucose, total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, triglycerides, folate, vitamin B12, and Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) were available for 88 patients; insulin for 82 patients, AST and ALT were available for 81 patients, C-reactive protein (CRP), 78 patients.

Table 2

| Clinical characteristics | Participants (N = 91) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension, n (%) | 70 (76.9) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 54 (59.3) |

| IFG/T2DM, n (%) | 26 (28) |

| TIA, n (%) | 6 (6.5) |

| CHD, n (%) | 6 (6.5) |

| Atrial Fibrillation, n (%) | 6 (6.6) |

| CIRS-G (TS) | 14.4 ± 4.1 |

| CIRS-G (SI) | 1.16 ± 0.32 |

| Medications* | |

| Antihypertensives (%) | 80 |

| Antiplatelet (%) | 62 |

| Oral hypoglycemics (%) | 16 |

| Lipid lowering (%) | 43 |

Prevalence of cardiometabolic disorders and level of multimorbidity.

Data are presented as percentages or mean (± SD). CIRS-G (TS): Cumulative Illness Rating scale for geriatrics (Total Score); CIRS-G (SI): Cumulative Illness Rating scale for Geriatrics (Severity Index). IFG, impaired fasting glucose; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. TIA, transient ischemic attack; CHD, coronary heart disease. *Most prevalent medications prescribed for cardiometabolic disorders were available for 68 patients.

3.2 Relationship between IGF-I, vitamin D, and parameters of body composition

The median IGF-I level was 122.0 ng/mL (IQR, 69.8), while the mean 25(OH) Vitamin D level was 27.04 ng/mL (±14.69 SD). IGF-I levels were significantly higher in males compared to females (p = 0.0096), whereas no significant sex differences were observed for the 25(OH) Vitamin D (Figures 1A,B). Levels of 25(OH) Vitamin D positively correlated with IGF-I (ρ = 0.317, p = 0.003) (Figure 1C), while no significant correlations were found between 25(OH) Vitamin D and body composition parameters. As expected, parameters of muscularity were higher in males compared to females (ICW: p < 0.001; FFM: p < 0.001; MM: p < 0.001; BCM: p < 0.001), while no significant sex differences were observed for FM (p = 0.272). In an exploratory sex-stratified analysis, a positive trend was observed between IGF-I and BCM in females only (ρ = 0.256, p = 0.086). Additionally, a direct correlation between FM and CRP was found in the overall cohort (ρ = 0.387, p < 0.001).

Figure 1

Sex differences in circulating levels of IGF-I (A) and 25(OH) Vitamin D (B). Bars represent mean ± SD. Scatter plot showing the Spearman correlation between 25(OH) Vitamin D and IGF-I levels, with a fitted regression line (C); p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Created with BioRender.com. Vicinanza, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/l25t663.

Given the lack of consistent sex-specific associations between IGF-I and parameters of muscularity, the cohort was subsequently dichotomized based on the median IGF-I level, resulting in two subgroups: low (IGF-I ≤ 122.0 ng/mL) and high (IGF-I > 122.0 ng/mL). As summarized in Table 3, significant clinical differences between the two groups were observed for number of males (high IGF-I vs. low IGF-I, 29 vs. 18; p = 0.017) and 25(OH) Vitamin D levels (high IGF-I vs. low IGF-I, 30.37 ± 15.04 vs. 23.45 ± 2.14 ng/mL; p = 0.031).

Table 3

| Parameter | High IGF-I ≥122.0 ng/mL |

Low IGF-I levels <122.0 ng/mL |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 46) | (N = 47) | ||

| Age, years | 74.0 ± 7.5 | 74.7 ± 6.9 | 0.588 |

| Males, n (%) | 29 (63) | 18 (38) | 0.017 |

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.9 ± 4.1 | 28.3 ± 4.2 | 0.669 |

| Body weight, kg | 75.2 ± 13.9 | 72.1 ± 12.3 | 0.266 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 101.3 ± 10.5 | 98.1 ± 10.6 | 0.154 |

| Nutrition and hormones | |||

| Folate (ng/mL) | 7.70 (4) | 7.95 (4.3) | 0.941 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 361 (277) | 337 (249) | 0.366 |

| 25 OH Vitamin D (ng/mL) | 30.37 ± 15.04 | 23.45 ± 2.14 | 0.031 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 45.15 ± 2.34 | 44.91 ± 2.58 | 0.658 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 88 (24) | 95 (19) | 0.382 |

| Fasting Insulin, μUI/mL | 9.3 (7.1) | 9 (9.53) | 0.579 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.6 (0.70) | 5.5 (0.5) | 0.342 |

| Physical activity | |||

| PASE score | 116.5 ± 63.76 | 118.6 ± 54.94 | 0.867 |

| Inflammation and comorbidity | |||

| C-reactive protein, μg/mL | 2000 (2700) | 2200 (2550) | 0.889 |

| CIRS-G (TS) | 12.47 ± 0.67 | 12.37 ± 0.54 | 0.455 |

| CIRS-G (SI) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.956 |

Clinical variables according to high (≥122.0 ng/mL) and low (<122.0 ng/mL) levels of IGF-I.

Data are presented as mean (± SD) or median (IQR). Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used based on the normality of the data distribution; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and indicated in bold. CIRS-G (TS): Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (Total Score); CIRS-G (SI): Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (Severity Index); PASE: Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

In terms of body composition, patients with higher IGF-I exhibited significantly greater values, compared to low IGF-I, for the following parameters: TBW (41.69 ± 8.7 Lt vs. 37.70 ± 7.92 Lt; p = 0.024), ICW (21.50 [IQR, 8.6] Lt vs. 17.55 [IQR, 9.3] Lt; p = 0.018), FFM (52.23 ± 11.06 kg vs. 47.11 ± 9.90 kg; p = 0.022), MM (33.26 ± 7.45 kg vs. 29.45 ± 7.52 kg, p = 0.017) and BCM (26.66 ± 9.46 kg vs. 24.77 ± 8.90 kg; p = 0.046). No significant difference in FM was observed between the two groups (Table 4).

Table 4

| Body composition measures | High IGF-I ≥122.0 ng/mL |

Low IGF-I levels <122.0 ng/mL |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| TBW, Lt | 41.69 ± 8.7 | 37.70 ± 7.92 | 0.024 |

| ICW, Lt | 21.50 (8.6) | 17.55 (9.3) | 0.018 |

| ECW, Lt | 20.06 (7.2) | 18.25 (4.28) | 0.116 |

| FFM, kg | 52.23 ± 11.06 | 47.11 ± 9.90 | 0.022 |

| MM, kg | 33.26 ± 7.45 | 29.45 ± 7.52 | 0.017 |

| BCM, kg | 26.66 ± 9.46 | 24.77 ± 8.90 | 0.046 |

| FM, kg | 25.59 ± 6.83 | 26.62 ± 7.42 | 0.491 |

Body composition parameters according to high and low levels of IGF-I.

Data is presented as mean (± SD) or median (IQR). Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used based on the normality of the data distribution; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and indicated in bold. TBW, total body water; ICW, intracellular water; ECW, extracellular water; FFM, fat-free mass; MM, muscle mass; BCM, body cell mass; FM, fat mass.

Linear regression analysis was performed to identify factors independently associated with FFM. The analysis revealed that IGF-I levels (B = 0.40, p = 0.034) and male sex (B = 13.933, p < 0.001) were independently and significantly associated with FFM. No significant associations were found for age (p = 0.154), 25(OH) Vitamin D (p = 0.398), levels of physical activity (PASE score) (p = 0.425), and level of multimorbidity (CIRS-G score) (p = 0.645) (Table 5).

Table 5

| Variable | B | S. E. | t | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | −0.193 | 0.143 | −1.441 | −0.461 | 0.074 | 0.154 |

| Male | 13.933 | 1.872 | 7.443 | 10.198 | 17.667 | <0.001 |

| IGF-I (ng/mL) | 0.40 | 0.019 | 2.159 | 0.003 | 0.077 | 0.034 |

| 25(OH) Vitamin D (ng/mL) | −0.53 | 0.062 | −0.850 | −0.177 | 0.071 | 0.398 |

| PASE score | −0.13 | 0.016 | −0.802 | −0.045 | 0.019 | 0.425 |

| CIRS-G (TS) | 0.691 | 1.494 | 0.463 | −2.289 | 3.671 | 0.645 |

Linear regression analysis with FFM (Fat-Free Mass) as a dependent variable.

CIRS-G (TS), Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics (Total Score); PASE, Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant and indicated in bold.

3.3 Mediation analysis

Although our analysis found no significant associations between Vitamin D and FFM, we hypothesized that the effect of Vitamin D on FFM could be mediated by IGF-I. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a mediation analysis, using 25(OH) Vitamin D as the independent variable, FFM as the dependent variable, and IGF-I as the mediator, adjusting for age and sex. The results of the mediation analysis showed a significant positive effect of Vitamin D on IGF-I (B = 0.951; SE = 0.374, p = 0.013). In turn, IGF-I was positively associated with FFM (B = 0.041; SE = 0.017, p = 0.017). As expected, the direct effect of Vitamin D on FFM was not significant (B = −0.058; SE = 0.058, p = 0.319), nor was the total effect of Vitamin D on FFM (B = −0.019; SE = 0.058, 95% CI: −0.134, 0.096, p = 0.738). However, the indirect effect of Vitamin D on FFM through IGF-I was significant (B = 0.039; SE = 0.022, 95% CI: 0.005, 0.091) with male sex being a significant covariate in the model (B = 12.555, p < 0.001). Results of the mediation analysis are reported in Figure 2, integrated with the associated graphical representation of the theoretical framework.

Figure 2

Integrated graphical representation of the mediation model and conceptual framework. Results of the mediation analysis were obtained after controlling for age and sex. The analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of 25(OH) Vitamin D on fat-free mass (FFM) through IGF-I as a mediator, suggesting a physiological regulatory pathway in which Vitamin D influences FFM by modulating IGF-I in the liver. Male sex was a significant covariate in the model (B = 12.555, p < 0.001). BCCI: Bias-corrected confidence intervals; SE = Standard Error. Created with BioRender.com. Vicinanza, R. (2025) https://BioRender.com/c27j696.

4 Discussion

The present study investigated the relationships between IGF-I, Vitamin D, and body composition parameters in geriatric outpatients with moderate multimorbidity. Our findings showed that (i) IGF-I positively and significantly correlated with Vitamin D, (ii) higher IGF-I, but not Vitamin D, was significantly associated with parameters of muscularity, and along with male sex, was an independent predictor of FFM, (iii) IGF-I was an indirect mediator of the effect of Vitamin D on FFM, although no significant direct or total effects were found.

The observed relationship between Vitamin D and IGF-I was consistent with previous findings (46, 64–66), including a Mendelian randomization study demonstrating a positive association between IGF-I and 25(OH) Vitamin D levels (45). Additionally, a 12-week intervention study with oral Vitamin D3 supplementation resulted in a dose-dependent increase of IGF-I in adults (67), and similar results were found with 6-month supplementation in overweight patients (68). However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials yielded mixed results (49). In animal models, VDR knockout mice exhibited reduced IGF-I levels (69), although the precise mechanisms through which Vitamin D may modulate IGF-I production and bioavailability remain unclear (70). In vitro studies suggested that non-parenchymal liver cells (e.g., stellate cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells), rather than hepatocytes, express the VDR (52). In turn, the binding of the VDR to the Vitamin D Responsive Element (VDRE) has been shown to activate the promoter regions of the Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3 (IGFBP-3) gene, the primary binding protein for IGF-I, in several cell types (71, 72). On the other hand, IGF-I has been shown to stimulate 1α-hydroxylase enzyme in renal cells, while treatment with IGF-I has been reported to significantly increase Vitamin D levels in healthy individuals (55). Taken together, these studies support the existence of a mutual nutrient-hormone interaction that should be considered in clinical practice, particularly in the assessment of Vitamin D deficiency, opening new windows of opportunity to explore treatment strategies.

Regarding the second aim of the study, consistent with previous observations (10, 37), we found that higher IGF-I levels were associated with TBW, ICW, MM, BCM and FFM. Supporting the role of IGF-I in maintaining healthy body composition, particularly in older adults, the InChianti study demonstrated that lower IGF-I concentrations were associated with an increased risk of sarcopenia (73). Other studies have shown that reduced serum concentrations of IGF-I correlated with increased frailty measures (74), decreased functional outcomes (75–78), and a reduced number of motor units (79). However, the exploratory analysis of variables found no significant association between IGF-I and the PASE scores, likely due to the low levels of physical activity within the cohort (80, 81). As expected, CRP was associated with FM (82, 83).

The relationship between IGF-I and clinical outcomes is complex, as both low and high IGF-I concentrations have been associated with increased risk of cancer, CVD, and all-cause mortality (39, 84). Rahmani et al. suggested that IGF-I levels between 120 and 160 ng/mL were associated with positive clinical outcomes and reduced mortality risk (85). Notably, consistent with this observation, in our cohort the median IGF-I value was 122 ng/mL, and no significant associations were found between IGF-I and levels of multimorbidity evaluated with the CIRS-G. Moreover, only participants with no history of cancer in the past 5 years were included, allowing this research to focus primarily on the role of IGF-I on body composition.

Although no associations were found between Vitamin D and parameters of muscularity in our cohort, such evidence has been observed in both human studies and animal models (24, 58, 86, 87). Therefore, we hypothesized a nutrient-hormone interaction where Vitamin D stimulates IGF-I in the liver, which in turn could mediate the effect of Vitamin D on FFM. Using a mediation analysis, previously implemented in the context of multimorbidity (88), we found that IGF-I was an indirect-only mediator for the effect of Vitamin D on FFM, while no significant direct or total effects were observed. Although speculative, these findings suggest a potential regulatory pathway through which Vitamin D may influence lean body mass via IGF-I. Thus, considering this pathway in the clinical setting could further support the evaluation of nutritional status and the assessment of pre-frailty.

Regarding the methods used for this statistical model, we acknowledge that in a typical mediation analysis, a significant relationship between the independent and dependent variable is generally considered a prerequisite for examining the indirect effect (89). Nevertheless, according to Rucker et al. and Preacher and Hayes, the absence of a significant direct or total effect does not preclude the investigation into the indirect effect if the theoretical framework or the rationale behind the analysis supports its plausibility (90, 91). Therefore, considering the described roles of both IGF-I and Vitamin D on lean body mass, we developed an integrated model to illustrate the mediation analysis results alongside the proposed physiological regulatory pathway that may underlie the observed associations (Figure 2).

However, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design did not allow for the determination of causality or the directionality of the observed associations. Second, the relatively small sample size constrained our ability to perform statistically robust stratifications by age and sex, limiting further investigation of subgroup differences without the loss of statistical power. Consequently, we conducted exploratory sex-stratified analyses with a limited number of participants and low intra-group variance, which may reduce the generalizability and reproducibility of our findings compared to larger studies. Furthermore, although free IGF-I is widely used to measure its serum levels (92), a more comprehensive evaluation of IGF-I bioavailability should also include IGFBP-3. Another limitation is the reliance on a self-administered questionnaire to evaluate physical activity levels, although we inferred the physical function of participants from indices of muscularity, measured with the BIA, and combined with assessment of ADLs and IADLs. Additionally, dietary intake was only partially collected with medical history, and more detailed information about the intake of macronutrients should be addressed. On the other hand, when the participants were divided by IGF-I levels, no significant clinical differences were found between the two groups aside from the variables of interest, indicating a relatively homogeneous sample. Moreover, examining the role of IGF-I in patients with multimorbidity offered a more real-life approach, particularly in geriatric medicine, since research in this population is often underrepresented.

In conclusion, these findings provide additional evidence of (i) a positive correlation between IGF-I and Vitamin D and (ii) the positive effect of IGF-I on parameters of muscularity. Finally, the mediation model suggests that IGF-I may contribute to the physiological effect of Vitamin D on FFM, with possible implications for assessing pre-frailty and personalizing nutrition interventions in this demographic.

Further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms and establish causality of these relationships.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics committee of the Policlinico Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RV: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JP: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. VM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MM: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. GI: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. PP: Writing – review & editing. EE: Writing – review & editing. MB: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. AM: Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Flaminia Crisciotti, Sciaila Bernardini, Elisa D’Ottavio, for their contributions to the organization and collection of clinical data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1.

López-Otín C Blasco MA Partridge L Serrano M Kroemer G . Hallmarks of aging: an expanding universe. Cell. (2023) 186:243–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.11.001

2.

Tenchov R Sasso JM Wang X Zhou QA . Aging hallmarks and progression and age-related diseases: a landscape view of research advancement. ACS Chem Neurosci. (2024) 15:1–30. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.3c00531

3.

Larsson L Degens H Li M Salviati L Lee Y Thompson W et al . Sarcopenia: aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev. (2019) 99:427–511. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00061.2017

4.

Roubenoff R . Sarcopenia: effects on body composition and function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2003) 58:M1012–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.11.M1012

5.

Billot M Calvani R Urtamo A Sánchez-Sánchez JL Ciccolari-Micaldi C Chang M et al . Preserving mobility in older adults with physical frailty and sarcopenia: opportunities, challenges, and recommendations for physical activity interventions. Clin Interv Aging. (2020) 15:1675–90. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S253535

6.

Zhou H Ding X Luo M . The association between sarcopenia and functional disability in older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. (2024) 28:100016. doi: 10.1016/j.jnha.2023.100016

7.

Goodpaster BH Park SW Harris TB Kritchevsky SB Nevitt M Schwartz AV et al . The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2006) 61:1059–64. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059

8.

Hajek A König HH . Longitudinal predictors of functional impairment in older adults in Europe – evidence from the survey of health, ageing and retirement in Europe. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0146967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146967

9.

Palmer AK Jensen MD . Metabolic changes in aging humans: current evidence and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Invest. (2022) 132:e158451. doi: 10.1172/JCI158451

10.

Baumgartner RN Waters DL Gallagher D Morley JE Garry PJ . Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mech Ageing Dev. (1999) 107:123–36. doi: 10.1016/S0047-6374(98)00130-4

11.

Houston DK Nicklas BJ Ding J Harris TB Tylavsky FA Newman AB et al . Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: the health, aging, and body composition (health ABC) study. Am J Clin Nutr. (2008) 87:150–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.1.150

12.

Barclay RD Burd NA Tyler C Tillin NA Mackenzie RW . The role of the IGF-1 signaling cascade in muscle protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in aging skeletal muscle. Front Nutr. (2019) 6:146. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2019.00146

13.

Velloso CP . Regulation of muscle mass by growth hormone and IGF-I. Br J Pharmacol. (2008) 154:557–68. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.153

14.

Ohlsson C Mohan S Sjögren K Tivesten Å Isgaard J Isaksson O et al . The role of liver-derived insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocr Rev. (2009) 30:494. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0010

15.

Takahashi Y . The role of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I in the liver. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:1447. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071447

16.

Jennische E Hansson HA . Regenerating skeletal muscle cells express insulin-like growth factor I. Acta Physiol Scand. (1987) 130:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08144.x

17.

Canicio J Gallardo E Illa I Testar X Palacín M Zorzano A et al . p70 S6 kinase activation is not required for insulin-like growth factor-induced differentiation of rat, mouse, or human skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology. (1998) 139:5042–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6360

18.

Coolican SA Samuel DS Ewton DZ McWade FJ Florini JR . The mitogenic and myogenic actions of insulin-like growth factors utilize distinct signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. (1997) 272:6653–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6653

19.

Vicinanza R Coppotelli G Malacrino C Nardo T Buchetti B Lenti L et al . Oxidized low-density lipoproteins impair endothelial function by inhibiting non-genomic action of thyroid hormone–mediated nitric oxide production in human endothelial cells. Thyroid. (2013) 23:231–8. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0524

20.

Laviola L Natalicchio A Giorgino F . The IGF-I signaling pathway. Curr Pharm Des. (2007) 13:663–9. doi: 10.2174/138161207780249146

21.

Hakuno F Takahashi SI . 40 years of IGF1: IGF1 receptor signaling pathways. (2018). Available online at: https://jme.bioscientifica.com/view/journals/jme/61/1/JME-17-0311.xml (Accessed September 30, 2024).

22.

Ahmad SS Ahmad K Lee EJ Lee YH Choi I . Implications of insulin-like growth Factor-1 in skeletal muscle and various diseases. Cells. (2020) 9:1773. doi: 10.3390/cells9081773

23.

Yoshida T Delafontaine P . Mechanisms of IGF-1-mediated regulation of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Cells. (2020) 9:1970. doi: 10.3390/cells9091970

24.

Barton-Davis ER Shoturma DI Sweeney HL . Contribution of satellite cells to IGF-I induced hypertrophy of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. (1999) 167:301–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00618.x

25.

Clemmons DR . Role of IGF-I in skeletal muscle mass maintenance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2009) 20:349–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.002

26.

Löfqvist C Andersson E Gelander L Rosberg S Blum WF Wikland KA . Reference values for IGF-I throughout childhood and adolescence: a model that accounts simultaneously for the effect of gender, age, and puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:5870–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.12.8117

27.

Janssen JAMJL . IGF-I and the endocrinology of aging. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. (2019) 5:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coemr.2018.11.001

28.

Svensson J Carlzon D Petzold M Karlsson MK Ljunggren Ö Tivesten Å et al . Both low and high serum IGF-I levels associate with Cancer mortality in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97:4623–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2329

29.

Hawkes CP Grimberg A . Insulin-like growth factor-I is a marker for the nutritional state. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. (2015) 13:499–511.

30.

Milman S Huffman DM Barzilai N . The Somatotropic Axis in human aging: framework for the current state of knowledge and future research. Cell Metab. (2016) 23:980–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.014

31.

Liang S Hu Y Liu C Qi J Li G . Low insulin-like growth factor 1 is associated with low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and metabolic syndrome in Chinese nondiabetic obese children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Lipids Health Dis. (2016) 15:112. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0275-7

32.

Succurro E Andreozzi F Marini MA Lauro R Hribal ML Perticone F et al . Low plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 levels are associated with reduced insulin sensitivity and increased insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. (2009) 19:713–9. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.12.011

33.

van Bunderen CC van Nieuwpoort IC van Schoor NM Deeg DJH Lips P Drent ML . The Association of Serum Insulin-like Growth Factor-I with mortality, cardiovascular disease, and Cancer in the elderly: a population-based study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2010) 95:4616–24. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0940

34.

Sanders JL Guo W O’Meara ES Kaplan RC Pollak MN Bartz TM et al . Trajectories of IGF-I predict mortality in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2018) 73:953–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx143

35.

Kubo H Sawada S Satoh M Asai Y Kodama S Sato T et al . Insulin-like growth factor-1 levels are associated with high comorbidity of metabolic disorders in obese subjects; a Japanese single-center, retrospective-study. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:20130. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23521-1

36.

Ascenzi F Barberi L Dobrowolny G Villa Nova Bacurau A Nicoletti C Rizzuto E et al . Effects of IGF-1 isoforms on muscle growth and sarcopenia. Aging Cell. (2019) 18:e12954. doi: 10.1111/acel.12954

37.

Bian A Ma Y Zhou X Guo Y Wang W Zhang Y et al . Association between sarcopenia and levels of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 in the elderly. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2020) 21:214. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03236-y

38.

Knuppel A Fensom GK Watts EL Gunter MJ Murphy N Papier K et al . Circulating insulin-like growth factor-I concentrations and risk of 30 cancers: prospective analyses in UK biobank. Cancer Res. (2020) 80:4014–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-1281

39.

Mukama T Srour B Johnson T Katzke V Kaaks R . IGF-1 and risk of morbidity and mortality from Cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and all causes in EPIC-Heidelberg. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2023) 108:e1092–105. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad212

40.

Kim JH Kim SJ Lee J Shin CH Seo JY . Factors affecting IGF-I level and correlation with growth response during growth hormone treatment in LG growth study. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0252283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252283

41.

Maggio M De Vita F Lauretani F Buttò V Bondi G Cattabiani C et al . IGF-1, the cross road of the nutritional, inflammatory and hormonal pathways to frailty. Nutrients. (2013) 5:4184–205. doi: 10.3390/nu5104184

42.

Moran S Chen Y Ruthie A Nir Y . Alterations in IGF-I affect elderly: role of physical activity. Eur Rev Aging Phys Act. (2007) 4:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s11556-007-0022-1

43.

Watts EL Perez-Cornago A Appleby PN Albanes D Ardanaz E Black A et al . The associations of anthropometric, behavioural and sociodemographic factors with circulating concentrations of IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2 and IGFBP-3 in a pooled analysis of 16,024 men from 22 studies. Int J Cancer. (2019) 145:3244–56. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32276

44.

Arturi F Succurro E Procopio C Pedace E Mannino GC Lugarà M et al . Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with low circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-I. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:E1640–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1227

45.

Gou Z Li F Qiao F Maimaititusvn G Liu F . Causal associations between insulin-like growth factor 1 and vitamin D levels: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front Nutr. (2023) 10:1162442. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1162442

46.

Bogazzi F Rossi G Lombardi M Tomisti L Sardella C Manetti L et al . Vitamin D status may contribute to serum insulin-like growth factor I concentrations in healthy subjects. J Endocrinol Investig. (2011) 34:e200–3. doi: 10.3275/7228

47.

Ciresi A Giordano C . Vitamin D across growth hormone (GH) disorders: from GH deficiency to GH excess. Growth Hormon IGF Res. (2017) 33:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2017.02.002

48.

Gómez JM Maravall FJ Gómez N Navarro MA Casamitjana R Soler J . Relationship between 25-(OH) D3, the IGF-I system, leptin, anthropometric and body composition variables in a healthy, randomly selected population. Horm Metab Res. (2004) 36:48–53. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814103

49.

Kord-Varkaneh H Rinaldi G Hekmatdoost A Fatahi S Tan SC Shadnoush M et al . The influence of vitamin D supplementation on IGF-1 levels in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. (2020) 57:100996. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100996

50.

Meshkini F Abdollahi S Clark CCT Soltani S . The effect of vitamin D supplementation on insulin-like growth factor-1: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. (2020) 50:102300. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102300

51.

Trummer C Schwetz V Pandis M Grübler MR Verheyen N Gaksch M et al . Effects of vitamin D supplementation on IGF-1 and calcitriol: a randomized-controlled trial. Nutrients. (2017) 9:623. doi: 10.3390/nu9060623

52.

Gascon-Barré M Demers C Mirshahi A Néron S Zalzal S Nanci A . The normal liver harbors the vitamin D nuclear receptor in non-parenchymal and biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology. (2003) 37:1034–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50176

53.

Moreno-Santos I Castellano-Castillo D Lara MF Fernandez-Garcia JC Tinahones FJ Macias-Gonzalez M . IGFBP-3 interacts with the vitamin D receptor in insulin signaling associated with obesity in visceral adipose tissue. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:2349. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112349

54.

Kamenický P Mazziotti G Lombès M Giustina A Chanson P . Growth hormone, insulin-like growth Factor-1, and the kidney: pathophysiological and clinical implications. Endocr Rev. (2014) 35:234–81. doi: 10.1210/er.2013-1071

55.

Bianda T Hussain MA Glatz Y Bouillon R Froesch ER Schmid C . Effects of short-term insulin-like growth factor-I or growth hormone treatment on bone turnover, renal phosphate reabsorption and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 production in healthy man. J Intern Med. (1997) 241:143–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.94101000.x

56.

Bersani FS Ghezzi F Maraone A Vicinanza R Cavaggioni G Biondi M et al . The relationship between vitamin D and depressive disorders. Riv Psichiatr. (2019) 54:229–34. doi: 10.1708/3281.32541

57.

Marcos-Pérez D Sánchez-Flores M Proietti S Bonassi S Costa S Teixeira JP et al . Low vitamin D levels and frailty status in older adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2286. doi: 10.3390/nu12082286

58.

Aspell N Laird E Healy M Lawlor B O’Sullivan M . Vitamin D deficiency is associated with impaired muscle strength and physical performance in community-dwelling older adults: findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Clin Interv Aging. (2019) 14:1751–61. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S222143

59.

Tan L He R Zheng X . Effect of vitamin D, calcium, or combined supplementation on fall prevention: a systematic review and updated network meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. (2024) 24:390. doi: 10.1186/s12877-024-05009-x

60.

Murad MH Elamin KB Abu Elnour NO Elamin MB Alkatib AA Fatourechi MM et al . The effect of vitamin D on falls: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:2997–3006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1193

61.

Haitchi S Moliterno P Widhalm K . Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in seniors – a retrospective study. Clin Nutr ESPEN. (2023) 57:691–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2023.07.005

62.

Andrew FH Michael DS Leslie BS Preacher KJ Hayes AF . SAGE research methods – the SAGE sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research – contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. (2025). Available online at: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/edvol/sage-srcbk-adv-data-analysis-methods-comm-research/chpt/contemporary-approaches-assessing-mediation-communication (Accessed February 5, 2025).

63.

Hayes AF . Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: a regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press (2018).

64.

Li W Yu T . Relationship between 25-hydroxyvitamin D and IGF1: a cross-sectional study of the third National Health and nutrition examination survey participants. J Health Popul Nutr. (2023) 42:35. doi: 10.1186/s41043-023-00374-6

65.

Hyppönen E Boucher BJ Berry DJ Power C . 25-Hydroxyvitamin D, IGF-1, and metabolic syndrome at 45 years of age: a cross-sectional study in the 1958 British birth cohort. Diabetes. (2008) 57:298–305. doi: 10.2337/db07-1122

66.

Mortensen C Mølgaard C Hauger H Kristensen M Damsgaard CT . Winter vitamin D3 supplementation does not increase muscle strength, but modulates the IGF-axis in young children. Eur J Nutr. (2019) 58:1183–92. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1637-x

67.

Ameri P Giusti A Boschetti M Bovio M Teti C Leoncini G et al . Vitamin D increases circulating IGF1 in adults: potential implication for the treatment of GH deficiency. Eur J Endocrinol. (2013) 169:767–72. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0510

68.

Al-Daghri NM Yakout SM Wani K Khattak MNK Garbis SD Chrousos GP et al . IGF and IGFBP as an index for discrimination between vitamin D supplementation responders and non-responders in overweight Saudi subjects. Medicine. (2018) 97:e0702. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010702

69.

Song Y Fleet JC Kato S . Vitamin D receptor (VDR) knockout mice reveal VDR-independent regulation of intestinal calcium absorption and ECaC2 and Calbindin D9k mRNA. J Nutr. (2003) 133:374–80. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.2.374

70.

Ameri P Giusti A Boschetti M Murialdo G Minuto F Ferone D . Interactions between vitamin D and IGF-I: from physiology to clinical practice. Clin Endocrinol. (2013) 79:457–63. doi: 10.1111/cen.12268

71.

Peng L Malloy PJ Feldman D . Identification of a functional vitamin D response element in the human insulin-like growth factor binding Protein-3 promoter. Mol Endocrinol. (2004) 18:1109–19. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0344

72.

Matilainen M Malinen M Saavalainen K Carlberg C . Regulation of multiple insulin-like growth factor binding protein genes by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Nucleic Acids Res. (2005) 33:5521–32. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki872

73.

Volpato S Bianchi L Cherubini A Landi F Maggio M Savino E et al . Prevalence and clinical correlates of sarcopenia in community-dwelling older people: application of the EWGSOP definition and diagnostic algorithm. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. (2014) 69:438–46. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt149

74.

Doi T Makizako H Tsutsumimoto K Hotta R Nakakubo S Makino K et al . Association between insulin-like growth factor-1 and frailty among older adults. J Nutr Health Aging. (2018) 22:68–72. doi: 10.1007/s12603-017-0916-1

75.

van Nieuwpoort IC Vlot MC Schaap LA Lips P Drent ML . The relationship between serum IGF-1, handgrip strength, physical performance and falls in elderly men and women. Eur J Endocrinol. (2018) 179:73–84. doi: 10.1530/EJE-18-0076

76.

Onder G Liperoti R Russo A Soldato M Capoluongo E Volpato S et al . Body mass index, free insulin-like growth factor I, and physical function among older adults: results from the ilSIRENTE study. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. (2006) 291:E829–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00138.2006

77.

Cappola AR Bandeen-Roche K Wand GS Volpato S Fried LP . Association of IGF-I levels with muscle strength and mobility in older women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:4139–46. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.9.7868

78.

Barbieri M Ferrucci L Ragno E Corsi A Bandinelli S Bonafè M et al . Chronic inflammation and the effect of IGF-I on muscle strength and power in older persons. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2003) 284:E481–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00319.2002

79.

Jarmusch S Baber L Bidlingmaier M Ferrari U Hofmeister F Hintze S et al . Influence of IGF-I serum concentration on muscular regeneration capacity in patients with sarcopenia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. (2021) 22:807. doi: 10.1186/s12891-021-04699-3

80.

Washburn RA Smith KW Jette AM Janney CA . The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. (1993) 46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4

81.

Washburn RA McAuley E Katula J Mihalko SL Boileau RA . The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): evidence for validity. J Clin Epidemiol. (1999) 52:643–51. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00049-9

82.

Visser M Bouter LM McQuillan GM Wener MH Harris TB . Elevated C-reactive protein levels in overweight and obese adults. JAMA. (1999) 282:2131–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2131

83.

Zuliani G Volpato S Galvani M Blè A Bandinelli S Corsi AM et al . Elevated C-reactive protein levels and metabolic syndrome in the elderly: the role of central obesity data from the InChianti study. Atherosclerosis. (2009) 203:626–32. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.038

84.

Zhang WB Ye K Barzilai N Milman S . The antagonistic pleiotropy of insulin-like growth factor 1. Aging Cell. (2021) 20:e13443. doi: 10.1111/acel.13443

85.

Rahmani J Montesanto A Giovannucci E Zand H Barati M Kopchick JJ et al . Association between IGF-1 levels ranges and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Aging Cell. (2022) 21:e13540. doi: 10.1111/acel.13540

86.

Kirwan R Isanejad M Davies IG Mazidi M . Genetically determined serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D is associated with Total, trunk, and arm fat-free mass: a Mendelian randomization study. J Nutr Health Aging. (2022) 26:46–51. doi: 10.1007/s12603-021-1696-1

87.

Sun X Tanisawa K Zhang Y Ito T Oshima S Higuchi M et al . Effect of vitamin D supplementation on body composition and physical fitness in healthy adults: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Nutr Metab. (2019) 75:231–7. doi: 10.1159/000504873

88.

Vicinanza R Bersani FS D’Ottavio E Murphy M Bernardini S Crisciotti F et al . Adherence to Mediterranean diet moderates the association between multimorbidity and depressive symptoms in older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2020) 88:104022. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2020.104022

89.

Baron RM Kenny DA . The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1986) 51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

90.

Rucker DD Preacher KJ Tormala ZL Petty RE . Mediation analysis in social psychology: current practices and new recommendations. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. (2011) 5:359–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x

91.

Preacher KJ Hayes AF . Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. (2008) 40:879–91. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

92.

Chen JW Højlund K Beck-Nielsen H Sandahl Christiansen J Ørskov H Frystyk J . Free rather than Total circulating insulin-like growth factor-I determines the feedback on growth hormone release in Normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2005) 90:366–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0039

Summary

Keywords

aging, body composition, fat-free mass, frailty, IGF-I, insulin-like growth factor-I, multimorbidity, vitamin D

Citation

Vicinanza R, Frizza A, Pollard JA, Mazza V, De Martino MU, Imbimbo G, Pignatelli P, Ettorre E, Del Ben M and Molfino A (2025) Aging and IGF-I: relationships with vitamin D and body composition. A mediation analysis. Front. Nutr. 12:1585696. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1585696

Received

01 March 2025

Accepted

30 May 2025

Published

24 June 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Carlo Pedrolli, Azienda Provinciale per i Servizi Sanitari (APSS), Italy

Reviewed by

Elena Succurro, University of Magna Graecia, Italy

Francesco S. Celi, UConn Health, United States

Benjamin Trujillo-Hernandez, University of Colima, Mexico

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Vicinanza, Frizza, Pollard, Mazza, De Martino, Imbimbo, Pignatelli, Ettorre, Del Ben and Molfino.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roberto Vicinanza, Roberto.vicinanza@usc.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.