- 1The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2School of Nursing, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 3Xiangya School of Nursing, Central South University, Changsha, China

Background: Diet quality is a determinant of healthy aging and contributes to reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancers, which impose considerable burdens on healthcare systems in China. Despite significant nutritional guidelines, older adults’ adherence to healthy eating remains inadequate. Understanding the determinants is essential for improving their adherence. Eating motivation is a key factor in exploring the reasons behind food choices.

Methods: Brislin’s classical translation model was rigorously utilized to translate the Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS) into Chinese, involving forward translation, back translation, and expert consultation by a panel of healthcare and nutrition specialists. Cognitive interviews were conducted for further adaptation to assess clarity, intelligibility, and cultural appropriateness, following the Cognitive Interviewing Reporting Framework (CIRF). After linguistic adaptation, the Chinese version of TEMS was used on eligible older adults to test the reliability and validity.

Results: Cognitive interviews conducted with 23 participants over 3 iterative rounds revealed issues with item wording, font size, and layout. Additionally, 249 elderly community residents participated in testing the reliability and validity. A total of 12 items were reworded to adapt the instrument to Chinese culture while maintaining their conceptual objectives. Colloquial words were revised and the formatting was adjusted with 1.5 line spacing and a font size of 14 in SimSun font to enhance readability. Practical examples were added to improve item comprehension, particularly for less-educated respondents. The results indicated that Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.772, and the split-half coefficient was 0.871.

Conclusion: This study successfully adapts TEMS to the Chinese context, providing a reliable and culturally sensitive measure of eating motivations, which is crucial for developing effective dietary interventions to enhance diet quality and promote healthy aging. The study underscores the importance of considering linguistic and cultural nuances in cross-cultural instrument adaptation and offers insights for future studies.

1 Introduction

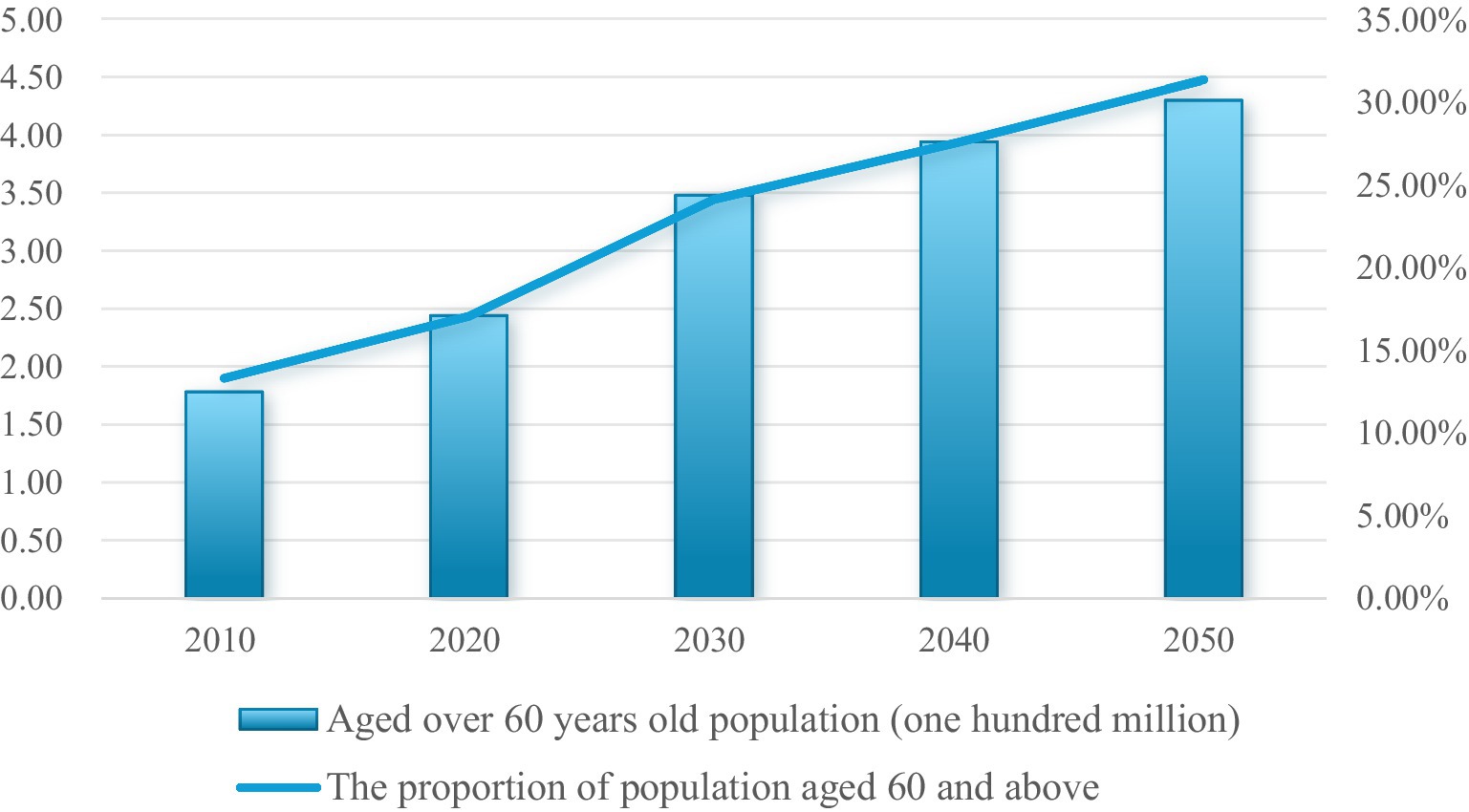

The global demographic shift toward an increasingly aging population is characterized by a growing proportion of older adults and a corresponding increase in age-related diseases. This demographic transition underscores the importance of “healthy aging,” a paradigm aimed at minimizing the risk of age-related diseases and mitigating disability in advanced age (1), particularly in China (Figure 1), which has the largest elderly population in the world (2). Diet quality serves as a fundamental determinant of healthy aging (3), as unhealthy diets significantly contribute to obesity and chronic diseases (4, 5). Obesity, in turn, exacerbates these conditions and accelerates the transition to a poorer nutritional status (6).

Healthy eating can potentially prevent, treat, and even reverse chronic diseases (7–9), and it can contribute to the prevention of age-related syndromes such as frailty and sarcopenia, which significantly impair healthy aging (10, 11). Despite considerable research and nutritional guidelines, adherence to healthy eating among Chinese older adults remains inadequate (12, 13). The prevalence and mortality rates of chronic diseases are on the rise in China (14–16), which impose substantial burdens on healthcare systems (17). Effective measures are urgently needed to intervene in Chinese older adults’ unhealthy eating behaviors and improve their health condition. Identifying the underlying determinants influencing eating behaviors is essential for developing effective interventions to enhance dietary adherence and overall health, promoting healthy aging. One approach concerning individual drivers of eating behavior is to investigate their eating motivation (6). Eating motivation plays a pivotal role in shaping food choices, causes changes in the dietary patterns of older adults, and affects their nutritional health status (18, 19), which is considered a critical approach to understanding “why we eat what we eat” and comprehensively analyzing the determinants of eating behaviors (20, 21). Therefore, identifying the eating motivation characteristics of the elderly may help in the in-depth analysis of their eating behaviors and facilitate targeted measures in the future.

Multidimensional motivations influence older people’s daily lives and the cultural background that underpins their eating behaviors. Previous researchers have designed questionnaires to systematically assess individuals’ eating motivations. A pioneering effort in this field was the development of the Food Choice Questionnaire (FCQ) by British scholars Steptoe, Pollard, and Wardle in 1995 (22). However, the FCQ’s origins date back to a time when certain critical motivations, such as social and psychological factors, were not completely recognized (6). Subsequent research suggests that older adults eating behaviors are influenced by a complex interplay of personal emotions (23), social relationships, and other factors (24). To address these gaps, the Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS) was developed by a German research team in 2012 after a thorough review of previous quantitative instruments for measuring eating motivations, and 12 experts in nutrition and psychology were invited to be interviewed repeatedly, and 94 motivations were extracted from 241 kinds of motivations for compilation and factor analysis (21). Eventually, TEMS revealed 15 basic motivations for eating behaviors in daily life: likes, habits, needs and hunger, health, convenience, pleasure, traditional eating, natural attention, sociability, price, visual appeal, weight control, emotional regulation, social norms, and social image. TEMS has been recognized as a comprehensive and multifaceted tool (11) and has been widely applied in the United States (25), the United Kingdom (26), and India (19), among others, demonstrating satisfactory reliability and validity.

To our knowledge, there are currently no suitable instruments available to effectively evaluate the eating motivation of older Chinese adults. Our study aims to address this issue by translating and culturally adapting the TEMS to assess the eating motivations of this demographic. This effort is crucial for developing targeted interventions in future research that could improve adherence to healthy eating, enhance nutritional health, and reduce the burden of chronic diseases (27, 28). However, given that previous studies have been conducted in English, the interpretation and comprehension of TEMS items within the Chinese context remain uncertain. Chinese traditional culture possesses distinct characteristics when compared to those of other nations, such as its unique traditional values (“Mianzi” consciousness) (29). Given the linguistic and cultural subtleties, cognitive interviewing plays a crucial role in tailoring the TEMS to the Chinese context, in line with the recommendations of the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN), to enhance the reliability and validity of questionnaires during cross-cultural adaptation (30, 31).

Hence, the primary goal of our study is to refine the TEMS for the Chinese context by identifying problematic items, assessing cultural appropriateness, and ensuring user-friendliness to validate its linguistic adaptation. Our study also seeks to confirm the cross-cultural applicability of TEMS.

2 Materials and methods

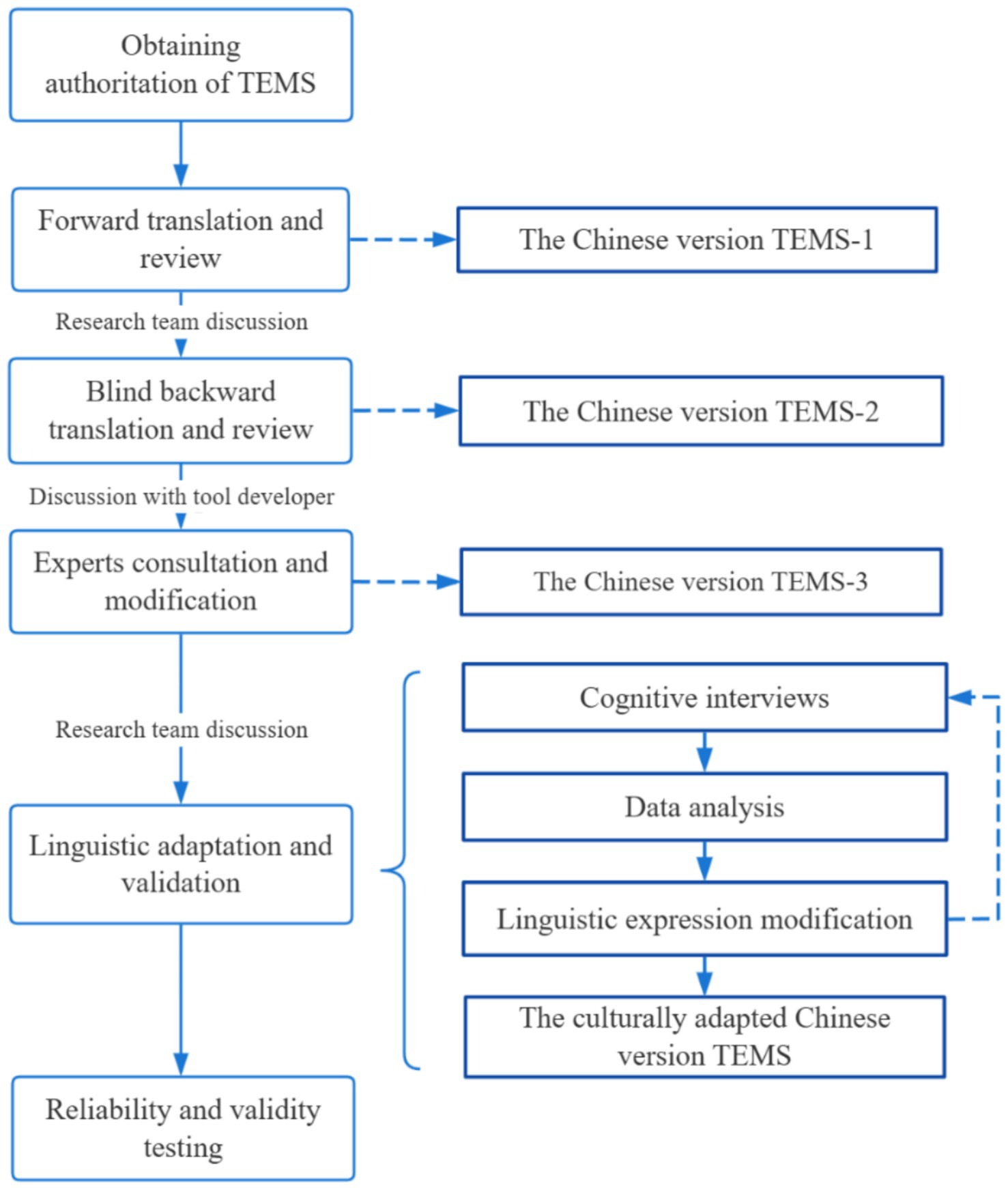

The TEMS original items were translated into Chinese by a panel of healthcare specialists and nutrition specialists, following Brislin’s classical translation model, a comprehensive recommendation of translation, adaptation, and validation of a model for cross-cultural research (32). This study utilized a sequential exploratory mixed-methods design. After the translation finished, cognitive interviews were conducted to ensure linguistic validation, following the Cognitive Interviewing Reporting Framework (CIRF) during the implementation and results report (33). Cognitive interviewing is a recommended method for pre-testing self-report tools to improve their reliability and validity by COSMIN, especially in cross-cultural adjustment and revision of the scale (30, 31). Subsequently, a cross-sectional survey was conducted to validate the Chinese version of the scale.

2.1 Study design

2.1.1 Step 1: forward translation

Two bilingual translators independently translated the original TEMS items and instructions into Chinese (Figure 2). One translator was knowledgeable about healthcare terminology and was fluent in English reading and speaking with 15 years of English study experience (WL). The other translator was a certified professional translator who graduated from Xiamen University and is an American native English speaker who holds a master’s degree in English translation (MW).

2.1.2 Step 2: review the two forward translation versions

The research team members reviewed the two forward translation versions with the original English TEMS, evaluating whether the translation correctly reflected the intended meanings of the original. Any questions that the researchers could not resolve were discussed with the research team until a consensus was reached, and the two forward translation versions were eventually integrated and then modified into the preliminary Chinese version (TEMS-1).

2.1.3 Step 3: blind backward translation

The TEMS-1 Chinese version (post-forward translation) was then independently translated back into English by two translators. One translator was a doctoral student at Xiangya Nursing School of Central South University and was familiar with healthcare terminology (JD). The other was a doctoral student at Shanghai Fudan University and has strong proficiency in English language (TOEFL score of 117) with 3 years of overseas study experience (TR). The backward translators had no previous exposure to the original English TEMS.

2.1.4 Step 4: review the two backward translation versions

Similar to the forward translation comparisons, the research team reviewed the two back-translated versions with the original scale and re-translated the items with a concordance rate of less than 90% until the concordance rate reached more than 90%, forming the English back-translated version. A remote video was then conducted with the tool developer to review and determine if it had semantic and conceptual ambiguities (GS). The research team continued to revise according to the advice of the tool developer until a consensus was reached, forming the preliminary Chinese translated version (TEMS-2).

2.1.5 Step 5: expert consultation’

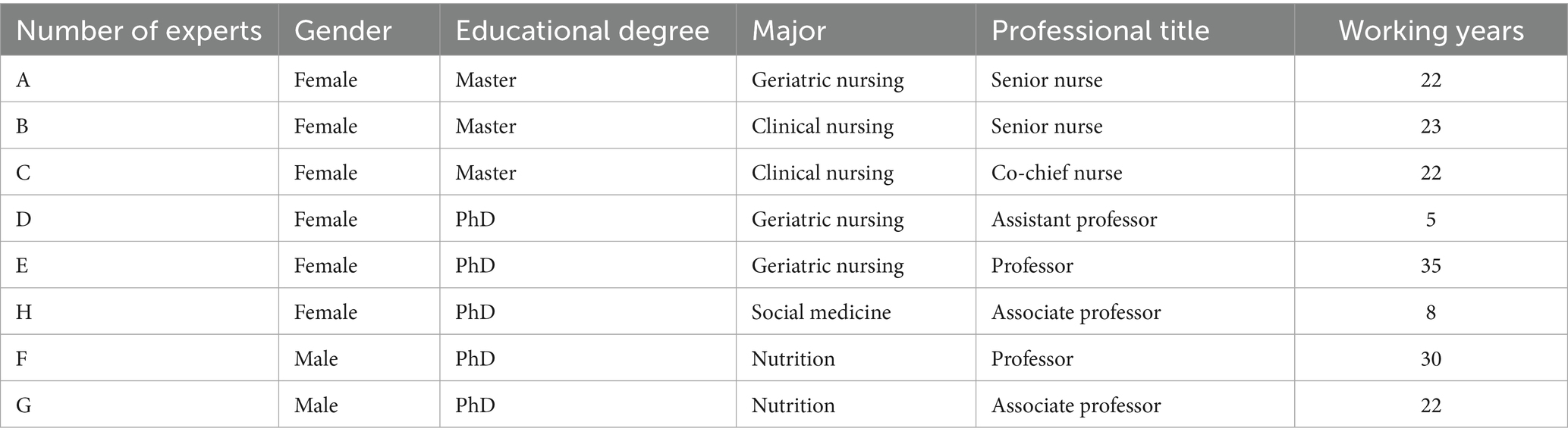

Eight experts in geriatric nursing, geriatrics, and nutrition were invited to evaluate and modify the expression and semantics of the preliminary Chinese version TEMS-2 (Table 1). According to the expert recommendations, the revised Chinese version TEMS-3 was obtained after modification.

The inquiry contents included the following: (1) whether the Chinese translation had the same meaning as the original, (2) whether the wording was used appropriately, (3) the relevance of each item to the assessed content, and (4) whether the expression habits conformed to Chinese culture.

Experts’ selection criteria included the following: (1) having an intermediate professional title and above or master’s degree and above, (2) having rich clinical experience in geriatric medicine or nutrition for 5 years and above, and (3) having abundant knowledge of the development of tools for measuring psychometric characteristics.

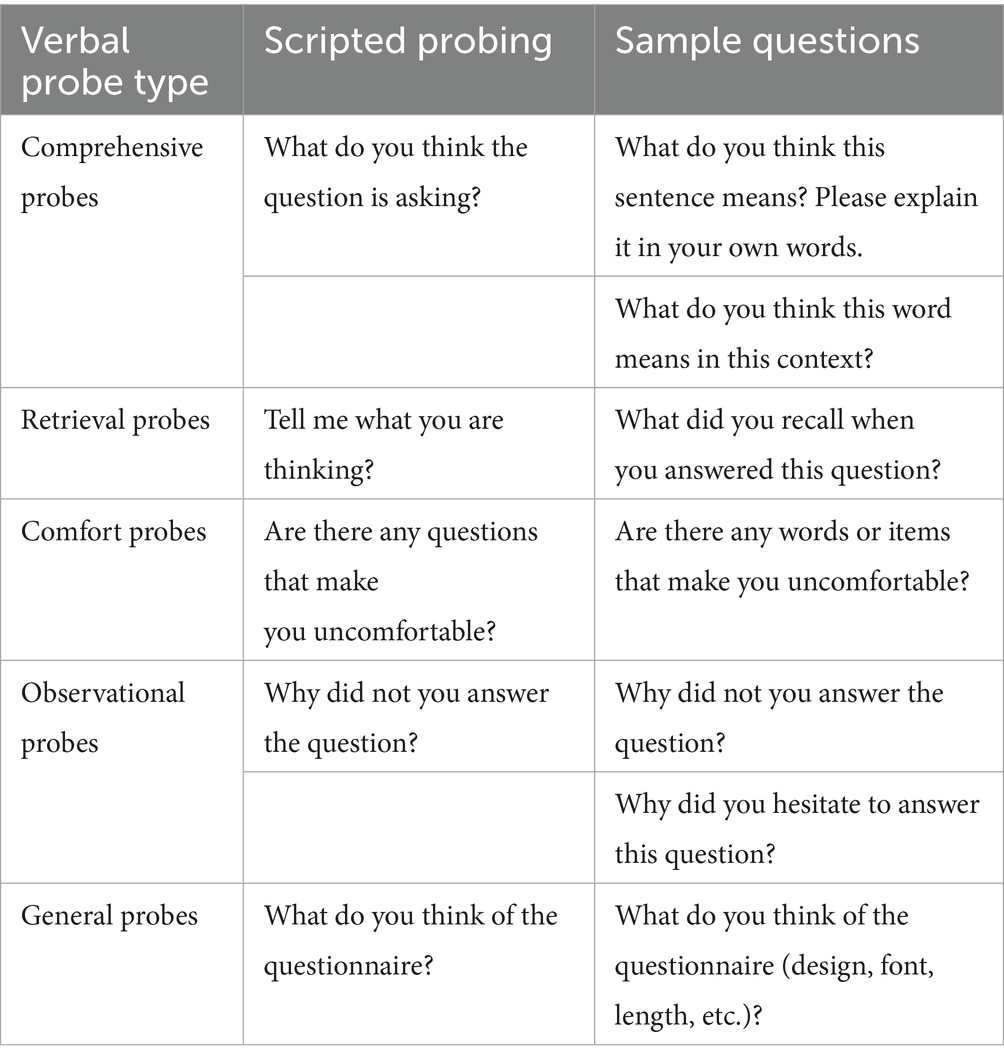

2.1.6 Step 6: cognitive interviews

Linguistic validation assesses how participants understand and respond to the instruments, evaluating the target population’s clarity, intelligibility, appropriateness, and cultural relevance to the target language version (34). Cognitive interview is an effective approach to understanding cognitive biases between researchers and respondents (30). Verbal probing was utilized to conduct linguistic validation, a cognitive interview method. Simultaneously, the research team developed the cognitive interview outline through a comprehensive literature review, categorizing it into five probe categories (Table 2). For cognitive interviews, multiple rounds were conducted, with at least five interviews per round. A total of 20–30 interviews are recommended to ensure thematic saturation (35).

2.1.7 Step 7: reliability and validity test

After linguistic validation, the Chinese version of TEMS was administered to eligible older adults within the Chinese community to further verify its reliability and validity. To allow cross-validation (36), we enrolled 249 participants, although a sample size of 200 participants would have been sufficient for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (37).

2.2 Setting and participant recruitment

The study was conducted from February to June 2023 in Changsha communities, China. Convenience sampling was used to recruit participants, who were 60 years or older and had no enteral or parenteral nutrition supplements. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and interviews were carried out face-to-face by an experienced researcher (WL) in a quiet room in the communities of Hunan Province. Following the guidelines, participants for each round of interviews were distinct, meaning that individuals interviewed in one round did not overlap with those in subsequent rounds (38).

.The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants aged 60 years or older, (2) individuals capable of effective communication and able to independently complete the questionnaire, (3) voluntary participation confirmed by signed informed consent, and (4) no enteral or parenteral nutrition supplements or voluntary restrictive diets within 1 month before the assessment. The exclusion criteria included older adults in the acute stage of any disease that may adversely affect nutritional status, energy intake, or nutrient absorption.

2.3 Data analysis

This study conducted data sorting and results reporting following CIRF (33). The interview process was audio recorded, transcribed in time by one researcher (WL), and reviewed by other researchers (CX and JD). Five probe categories of cognitive interviewing were considered as individual themes for data analysis and were listed separately in an Excel sheet. Then, interview transcripts were entered into NVivo qualitative software and analyzed for cognitive requirements and linguistic issues. Investigator triangulation was used for data analysis to ensure the integrity and reliability of research results, which involved two researchers independently analyzing the same interview transcripts, avoiding the unilateral observation and understanding of a single researcher, to ensure higher reliability of the research results (34, 39).

2.4 Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Nursing and Behavioral Medicine Research Ethics Committee of Xiangya Nursing School of Central South University in China (E202320). Permission and authorization were obtained from the original scale developer to translate the TEMS into Chinese. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

3 Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

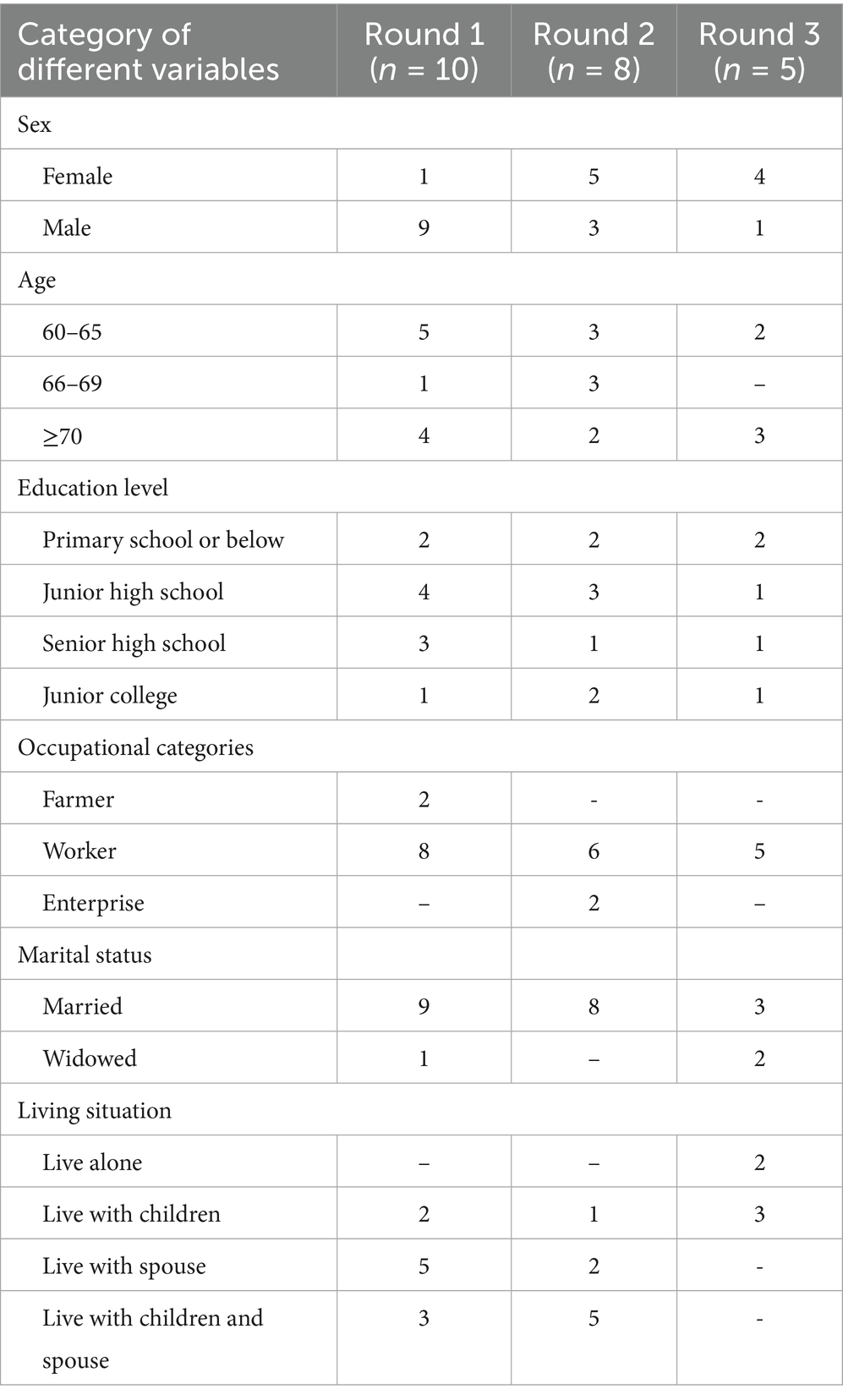

All translated items demonstrated ≥90% concordance in the initial back-translation evaluation, meeting our predefined quality threshold; therefore, no re-translation was required. Thus, three iterative rounds of cognitive interviews were conducted, and a total of 23 older adults participated. Interviewees in each round did not coincide; that is, the participants interviewed in each round were different. There were 10 interviewees in the first round of cognitive interviews, and the participants were coded as 1. P1–1. P10 according to the interview sequence. In addition, eight interviewees in the second round were coded as 2. P1–2. P8, and five interviewees in the third round were coded as 3. P1–3. P5 (Table 3). The final sample included 10 women and 13 men, ranging from 60 to 78 years old (mean: 67.217 years). Most of the participants were less educated (junior high school or below, 60.87%).

3.2 First-round cognitive interview

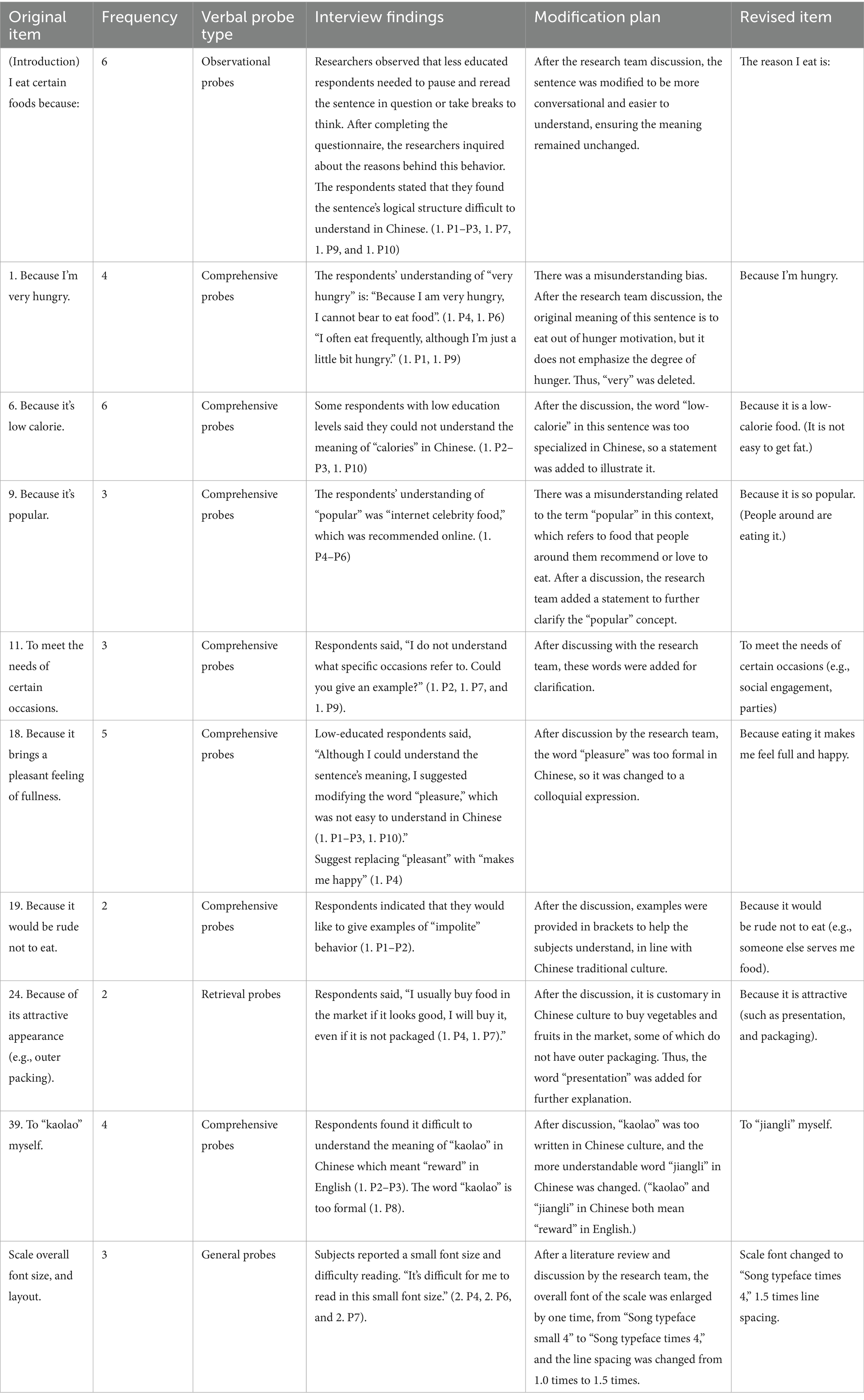

In this round, 10 participants (1. P1–1. P10) were involved and pointed out that there were ambiguities in the wording of 8 items, as well as indicated that font size and scale layout needed improvement. Based on the interview results, the research team analyzed the frequency, suggestions, and content of the questions raised by the participants in response to the questionnaire items. After discussion and modification, specific modification plans are detailed in Table 4. The modified TEMS scale was used for the second-round cognitive interview.

3.3 Second-round cognitive interview

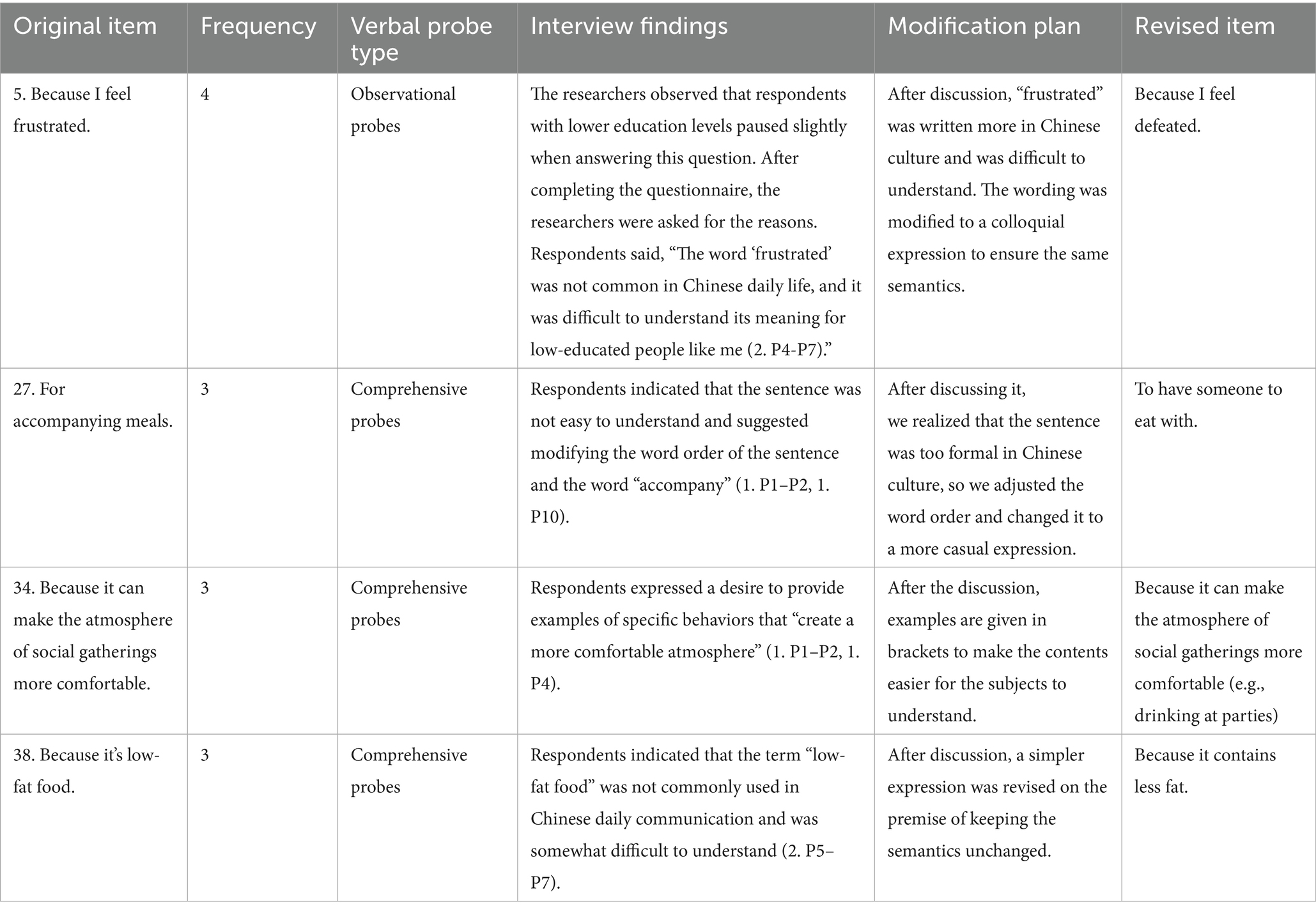

Eight participants (2. P1–2. P8) were recruited for the second-round cognitive interview after the initial revision of the TEMS scale. Notwithstanding these adjustments, participants still raised questions about identifying ambiguities within certain item phrasings. Utilizing the data derived from the second-phase cognitive interview, the research team conducted a rigorous analysis of the frequency and specifics of participants’ suggestions related to particular items. These findings were subsequently deliberated upon and integrated into the scale’s iterative refinement. A detailed exposition of the identified issues and the corresponding revisionary strategies is documented in Table 5. Following this interview, third-round cognitive interviews were conducted, employing the newly optimized TEMS scale.

3.4 Third-round cognitive interview

Five participants (3. P1–3. P5) were assembled, employing the scale refined following the second-round discussions for the third-round cognitive interview. Feedback revealed that participants generally found the scale items to be precise and intelligible, with phrasing consistent with traditional Chinese cultural values. No additional inquiries arose during the interviews, indicating a saturation of cognitive data. Consequently, the cross-cultural adjustment of the TEMS for the Chinese context was successfully achieved.

3.5 Reliability and validity of the TEMS Chinese version

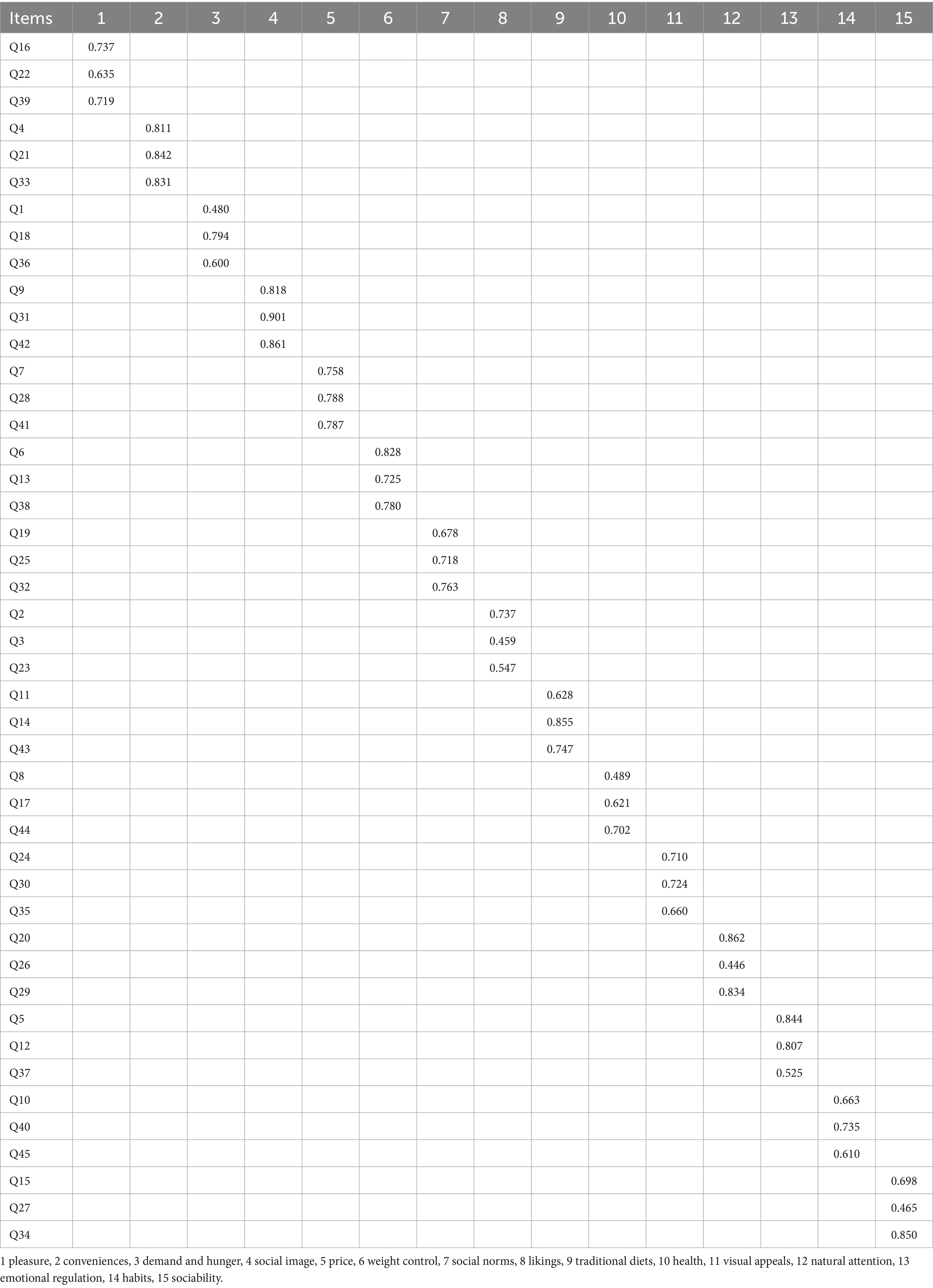

The Chinese version of TEMS was used on 249 eligible older adults living in the community for testing reliability and validity. The results showed that Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.772, the split-half coefficient was 0.871, the content validity index (S-CVI) was 0.930, and the range of the item content validity index (I-CVI) was 0.500–1.000. Additionally, the results of the exploratory factor analysis indicate that Bartlett’s sphericity test (X2 = 5219.724, df = 990, p < 0.001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value is 0.799, exceeding 0.600. Fifteen common factors were extracted, with a cumulative contribution rate of 73.535%, including likes, habits, needs and hunger, health, convenience, pleasure, traditional diet, natural concern, social interaction, price, visual appeal, weight control, emotional regulation, social norms, and social image. The loading value of each item ranges from 0.446 to 0.901 (Table 6), exceeding 0.400, confirming that reliability and validity are good.

4 Discussion

This study adhered rigorously to Brislin’s classical translation model to translate TEMS into Chinese, involving translation, back-translation, and expert consultation (32). High-quality translation and linguistic validation are the basis of psychometric and statistical testing (34). Nevertheless, practical data collection reveals challenges, such as participants with lower educational backgrounds having a limited understanding of the scale content, which may lead to misinterpretations and incorrect responses, thus deviating from the information the researchers intended to gather (40). These issues distort the data and compromise the quality of the scale. Researchers identify these as response errors, a significant barrier to the effectiveness of surveys, as designers often overestimate respondents’ comprehension of the content (41).

In this study, cognitive interviews were conducted to evaluate whether participants’ judgments of the content aligned with the original intent or introduced ambiguities. Subsequent refinements were made to ensure the content was accurate and conveyed in Chinese clearly, consistent with traditional Chinese cultural norms. Previous studies have shown that cognitive interviewing is valuable for understanding respondents’ comprehension and interpretation of questionnaires (42), a critical method for testing and refining questionnaires during cross-cultural linguistic adaptation (43). This process effectively minimized cultural discrepancies and resolved response errors (44, 45).

Most participants in the cognitive interviews had lower educational levels (junior high school level or below). Previous studies have shown that targeting respondents with lower educational levels in cognitive interviews is more effective (46). If this group accurately comprehends the scale content, it suggests that the scale is both intelligible and accurately conveys its intended meaning, thereby enhancing its content validity (46). This study identifies a preference among respondents, particularly those with lower educational levels, for clear explanations, concise presentations, straightforward logical sequences, and colloquial language. Our findings indicate that researchers often perceive terms deemed easy to understand as difficult to read by participants. Consequently, written words and technical terms in the original language were translated into more colloquial words in the Chinese version; these were not commonly used in Chinese daily communication and were somewhat difficult to understand for low-educated participants. In addition, we found that degree adverbs should be used with caution in sentence expressions, which tend to lead to response errors. Furthermore, providing examples significantly enhances participants’ comprehension of the scale items. Respondents prefer adding examples alongside technical terms to facilitate their understanding of the intended meaning. Additionally, our study reveals that a text format featuring 1.5 line spacing and a font size of 14 in SimSun font is deemed more readable and suitable for older participants. This preference likely arises from age-related visual impairments, which make simpler formatting and larger fonts more accessible for older respondents.

The TEMS factor structure demonstrated cross-cultural consistency, with our Chinese version replicating the same 15-factor solution as the Brazilian adaptation (6). Both studies achieved satisfactory psychometric properties (Cronbach’s α = 0.772 vs. 0.60–0.94 in Brazil), confirming measurement robustness across cultures. Notably, cultural variations emerged in motive prominence—traditional diet factors loaded strongly in our Chinese sample, while sociability motives were more salient in Brazil. These findings suggest that while TEMS captures universal eating motivations, their relative importance may reflect cultural values.

Meanwhile, our study has some limitations. As a dissertation project constrained by time limitations, this study prioritized establishing internal consistency and construct validity. Future research should incorporate test–retest assessments to fully address temporal stability according to Aldridge et al.’s comprehensive framework (47). Besides, although convenience sampling facilitated efficient participant recruitment, we acknowledge that this approach may affect the generalizability of our findings. The sample may not fully represent the broader population due to potential selection biases inherent in this method. We suggest that future studies employ probability sampling methods. In this study, cognitive interviews were conducted and analyzed in Chinese, and the subsequent translation of results and interviewee quotes into English may introduce bias. This translation process limits all researchers’ access to the original records. However, researcher triangulation was utilized to ensure the integrity of the data analysis.

5 Conclusion

Although time-consuming, cognitive interviewing is a crucial component of instrument development and a valuable method for identifying issues that might otherwise remain undetected and compromise the instrument’s effectiveness. It allows for the detection of linguistic and cultural nuances in cross-cultural instrument adaptation. Feedback from participants on question clarity and overall usefulness enabled researchers to make immediate adjustments. This iterative process enhanced the face validity of the instrument, which is expected to increase respondents’ willingness to participate and improve the instrument’s practical utility. Following further quantitative testing, the finalized TEMS will offer medical professionals an effective tool for assessing eating motivation among older Chinese adults.

Data availability statement

To protect participants’ privacy, the raw data that supports the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors exclusively for legitimate research purposes, ensuring adherence to ethical standards.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Xiangya Nursing School of Central South University in China. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LW: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. XC: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. HF: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. SC: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Guangzhou Science and Technology Key Project (Grant no. K0220090).

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the translation committee and interview participants for their time, support, and advice throughout the research process. Besides, all authors appreciate Professor Gudrun Sproesser, Mark Waters, and Ronglin Tang’s efforts and assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1676552.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

TEMS, The Eating Motivation Survey; FCQ, Food Choice Questionnaire; CIRF, Cognitive Interviewing Reporting Framework; COSMIN, Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Measurement Instruments.

References

1. Cosco, TD, Prina, AM, Perales, J, Stephan, BCM, and Brayne, C. Lay perspectives of successful ageing: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. BMJ Open. (2013) 3:e002710. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002710

2. Gao, S, Sun, S, Sun, T, Lu, T, Ma, Y, Che, H, et al. Chronic diseases spectrum and multimorbidity in elderly inpatients based on a 12-year epidemiological survey in China. BMC Public Health. (2024) 24:8006. doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-18006-x

3. Atallah, N, Adjibade, M, Lelong, H, Hercberg, S, Galan, P, Assmann, KE, et al. How healthy lifestyle factors at midlife relate to healthy aging. Nutrients. (2018) 10:10. doi: 10.3390/nu10070854

4. Neuhouser, ML. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res. (2019) 70:3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2018.06.002

5. Piche, M, Tchernof, A, and Despres, J. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. (2020) 126:1477–500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316101

6. Sproesser, G, Muniz Moraes, JM, Renner, B, and Alvarenga, MDS. The eating motivation survey in Brazil: results from a sample of the general adult population. Front Psychol. (2019) 10:10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02334

7. Garcia-Hermoso, A, Ezzatvar, Y, Francisco Lopez-Gil, J, Ramirez-Velez, R, Olloquequi, J, and Izquierdo, M. Is adherence to the Mediterranean diet associated with healthy habits and physical fitness? A systematic review and meta-analysis including 565 421 youths. Brit J Nutr. (2022) 128:1433–44. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520004894

8. Gauci, S, Young, LM, Arnoldy, L, Lassemillante, A, Scholey, A, and Pipingas, A. Dietary patterns in middle age: effects on concurrent neurocognition and risk of age-related cognitive decline. Nutr Rev. (2022) 80:1129–59. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuab047

9. Kojima, G, Avgerinou, C, Iliffe, S, and Walters, K. Adherence to Mediterranean diet reduces incident frailty risk: systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2018) 66:783–8. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15251

10. Cruz-Jentoft, AJ, Kiesswetter, E, Drey, M, and Sieber, CC. Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res. (2017) 29:43–8. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0709-0

11. Rempe, HM, Sproesser, G, Gingrich, A, Spiegel, A, Skurk, T, Brandl, B, et al. Measuring eating motives in older adults with and without functional impairments with the eating motivation survey (TEMS). Appetite. (2019) 137:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2019.01.024

12. Middleton, KR, Anton, SD, and Perri, MG. Long-term adherence to health behavior change. Am J Lifestyle Med. (2013) 7:395–404. doi: 10.1177/1559827613488867

13. Ter Borg, S, Verlaan, S, Hemsworth, J, Mijnarends, DM, Schols, JMGA, Luiking, YC, et al. Micronutrient intakes and potential inadequacies of community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Br J Nutr. (2015) 113:1195–206. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515000203

14. Cai, Y, Cui, X, Su, B, and Wu, S. Changes in mortality rates of major chronic diseases among populations aged over 60 years and their contributions to life expectancy increase-China, 2005-2020. China CDC Wkly. (2022) 4:866. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2022.179

15. Xu, QQ, Yan, YF, Chen, H, Dong, WL, Han, LY, and Liu, S. Predictions of achievement of sustainable development goal to reduce age-standardized mortality rate of four major non-communicable diseases by 2030 in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. (2022) 43:878–84. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20211028-00830

16. Yin, P, Qi, J, Liu, Y, Liu, J, You, J, Wang, L, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and mortality of four major chronic non-communicable diseases-China, 1990-2017. China CDC Wkly. (2019) 1:32–7. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2019.012

17. Rafacz, SD. Healthy eating: approaching the selection, preparation, and consumption of healthy food as choice behavior. Perspect Behav Sci. (2019) 42:647–74. doi: 10.1007/s40614-018-00190-y

18. Sofi, F, Cesari, F, Abbate, R, Gensini, GF, and Casini, A. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and health status: meta-analysis. BMJ. (2008) 337:1344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1344

19. Sproesser, G, Ruby, MB, Arbit, N, Rozin, P, Schupp, HT, and Renner, B. The eating motivation survey: results from the USA, India and Germany. Public Health Nutr. (2018) 21:515–25. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017002798

20. Deci, EL, and Ryan, RM. The\what\ and \why\ of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. (2000) 11:227–68. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

21. Renner, B, Sproesser, G, Strohbach, S, and Schupp, HT. Why we eat what we eat. The eating motivation survey (TEMS). Appetite. (2012) 59:117–28. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.004

22. Steptoe, A, Pollard, TM, and Wardle, J. Development of a measure of the motives underlying the selection of food: the food choice questionnaire. Appetite. (1995) 25:267–84. doi: 10.1006/appe.1995.0061

23. Kaiser, B, Gemesi, K, Holzmann, SL, Wintergerst, M, Lurz, M, Hauner, H, et al. Stress-induced hyperphagia: empirical characterization of stress-overeaters. BMC Public Health. (2022) 22:12488. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12488-9

24. Kim, C. Food choice patterns among frail older adults: the associations between social network, food choice values, and diet quality. Appetite. (2016) 96:116–21. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.015

25. Uyen, TXP, and Chambers, E. Data on motivations of food choices obtained by two techniques: online survey and in-depth one-on-one interview. Data Brief. (2018) 21:1370–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.10.108

26. Pechey, R, Monsivais, P, Ng, Y, and Marteau, TM. Why don't poor men eat fruit? Socioeconomic differences in motivations for fruit consumption. Appetite. (2015) 84:271–9. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.022

27. Mei, D, Deng, Y, Li, Q, Lin, Z, Jiang, H, Zhang, J, et al. Current status and influencing factors of eating behavior in residents at the age of 18∼60: a cross-sectional study in China. Nutrients. (2022) 14:14. doi: 10.3390/nu14132585

28. Rankin, A, Bunting, BP, Poinhos, R, van der Lans, IA, Fischer, ARH, Kuznesof, S, et al. Food choice motives, attitude towards and intention to adopt personalised nutrition. Public Health Nutr. (2018) 21:2606–16. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018001234

29. Bu, X, Nguyen, HV, Nguyen, QH, Chen, C, and Chou, TP. Traditional or fast foods, which one do you choose? The roles of traditional value, modern value, and promotion focus. Sustain For. (2020) 12:549. doi: 10.3390/su12187549

30. Mokkink, LB, Terwee, CB, Patrick, DL, Alonso, J, Stratford, PW, Knol, DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. (2010) 63:737–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

31. Thorvaldsdottir, KB, Halldorsdottir, S, Johnson, RM, Sigurdardottir, S, and Saint Arnault, D. Adaptation of the barriers to help-seeking for trauma (BHS-TR) scale: a cross-cultural cognitive interview study with female intimate partner violence survivors in Iceland. J Patient Report Outcomes. (2021) 5:295. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00295-0

32. Jones, PS, Lee, JW, Phillips, LR, Zhang, X, and Jaceldo, KB. An adaptation of Brislin's translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs Res. (2001) 50:300–4. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00008

33. Boeije, H, and Willis, G. The cognitive interviewing reporting framework (CIRF) towards the harmonization of cognitive testing reports. Methodology. (2013) 9:87–95. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000075

34. Hu, J, Gifford, W, Ruan, H, Harrison, D, Li, Q, Ehrhart, MG, et al. Translation and linguistic validation of the implementation leadership scale in Chinese nursing context. J Nurs Manag. (2019) 27:1030–8. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12768

35. Hodiamont, F, Hock, H, Ellis-Smith, C, Evans, C, De Wolf-Linder, S, Junger, S, et al. Culture in the spotlight-cultural adaptation and content validity of the integrated palliative care outcome scale for dementia: a cognitive interview study. Palliat Med. (2021) 35:962–71. doi: 10.1177/02692163211004403

36. Bunsuk, C, Suwanno, J, Klinjun, N, Kumanjan, W, Srisomthrong, K, Phonphet, C, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the Thai version of self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory Version 4.C. Int J Nurs Sci. (2023) 10:332–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.06.019

37. Anthoine, E, Moret, L, Regnault, A, Sebille, V, and Hardouin, J. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual Life Outcomes. (2014) 12:176–6. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0176-2

38. Egger-Rainer, A. Enhancing validity through cognitive interviewing. A methodological example using the epilepsy monitoring unit comfort questionnaire. J Adv Nurs. (2019) 75:224–33. doi: 10.1111/jan.13867

39. Tobin, GA, and Begley, CM. Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. J Adv Nurs. (2004) 48:388–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x

40. Drennan, J. Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs. (2003) 42:57–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02579.x

41. Mes, MA, Chan, AHY, Wileman, V, Katzer, CB, Goodbourn, M, Towndrow, S, et al. Patient involvement in questionnaire design: tackling response error and burden. J Pharm Policy Pract. (2019) 12:17. doi: 10.1186/s40545-019-0175-0

42. Pohontsch, N, and Meyer, T. Cognitive interviewing - a tool to develop and validate questionnaires. Rehabilitation (Stuttg). (2015) 54:53–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1394443

43. Park, H, Sha, MM, and Pan, Y. Investigating validity and effectiveness of cognitive interviewing as a pretesting method for non-English questionnaires: findings from Korean cognitive interviews. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2014) 17:643–58. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2013.823002

44. Balza, JS, Cusatis, R, McDonnell, SM, Basir, MA, and Flynn, KE. Effective questionnaire design: how to use cognitive interviews to refine questionnaire items. J Neonatal-Perinatal Med. (2022) 15:345–9. doi: 10.3233/NPM-210848

45. Wang, X, Ruan, H, Hu, J, Nicole, D, Jiang, L, Yang, Y, et al. The cognitive interview method in translating the general anesthesia patient satisfaction questionnaire. Nurs J Chin PLA. (2019) 36:42–5. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1008-9993.2019.11.011

46. Garfield, K, Husbands, S, Thorn, JC, Noble, S, and Hollingworth, W. Development of a brief, generic, modular resource-use measure (ModRUM): cognitive interviews with patients. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:6364. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06364-w

Keywords: eating motivation, food choice, linguistic validation, cognitive interview, healthy aging

Citation: Wu L, Chen X, Feng H and Cheng S (2025) Cross-cultural translation and linguistic validation of the eating motivation survey among older adults in the Chinese context. Front. Nutr. 12:1610598. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1610598

Edited by:

Monica Tarcea, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, RomaniaReviewed by:

Özge Cemali, Trakya University, TürkiyeAnisoara Pop, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences and Technology of Târgu Mureş, Romania

Copyright © 2025 Wu, Chen, Feng and Cheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shouzhen Cheng, MjIxODM1MTY0MUBxcS5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Lina Wu1,2†

Lina Wu1,2† Shouzhen Cheng

Shouzhen Cheng