- 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Southampton, Highfield, United Kingdom

- 2Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, Versoix, Switzerland

- 3Center for Physical Sciences and Technology, Vilnius, Lithuania

Strong scaling relations between host galaxy properties (such as stellar mass, bulge mass, luminosity, effective radius etc) and their nuclear supermassive black hole's mass point toward a close co-evolution. In this work, we first review previous efforts supporting the fundamental importance of the relation between supermassive black hole mass and stellar velocity dispersion (MBH-σe). We then present further original work supporting this claim via analysis of residuals and principal component analysis applied to some among the latest compilations of local galaxy samples with dynamically measured supermassive black hole masses. We conclude with a review on the main physical scenarios in favor of the existence of a MBH-σe relation, with a focus on momentum-driven outflows.

1. Introduction

Observational evidence suggests that most local galaxies host a central supermassive black hole (henceforth simply “black hole,” not to be confused with an “ordinary” stellar mass black hole). Indeed, galaxies for which high-resolution data can be acquired show stellar kinematic patterns strongly suggesting the presence of a central massive dark object [1, 2]. The central black hole masses, inferred from dynamical measurements of the motions of stars and/or gas in the host galaxies, appear to scale with galaxy-wide properties (or perhaps bulge-wide properties), such as stellar mass [3, 4] and stellar velocity dispersion [5–10]. The existence of such correlations is remarkable, as the black hole's (sub-parsec scale) sphere of influence is orders of magnitude smaller than the scale of it's host galaxy (kilo-parsec scale). These correlations suggest a close link (a “co-evolution”) between black holes and host galaxies [11, 12].

The existence of massive black holes at the center of galaxies also lends further support to the widely-accepted paradigm that quasars, and more generally Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN), are powered by matter accreting onto a central black hole. The release of gravitational energy from an infalling body of mass m approaching the Schwarzschild radius of a compact object of mass M, is in fact one of the most efficient known processes to release enough energy to explain the large luminosities in AGN. As discussed by Peterson [13], the emission from release of gravitational energy increases with the compactness of the source M/r. Assuming that most of the gravitational energy E powering the emission from an accreting black hole originates from within a few times Rs, say r = 5Rs, one could set E = GMm/5Rs, implying E = 0.1mc2. The latter efficiency η ~ 0.1 of energy conversion in units of the rest-mass energy, is orders of magnitude higher than the efficiency in stellar fusion (η ~ 0.008). Theoretical models have also suggested that the energy/momentum release from the central black hole, routinely known as “AGN feedback,” could have profound consequences on the fate of its host galaxy, potentially driving out a galaxy's gas reservoir, quenching star formation, and shaping the above-mentioned scaling relations [11, 14].

The most prominent and studied scaling relations relate the black hole mass MBH to the stellar velocity dispersion σe [15] and the (stellar) mass of the host bulge, Mbulge [and by extension the luminosity of the bulge Lbulge, see [16]]. Other types of correlations have been proposed in the literature, such as correlations with the bulge light concentration cbulge [17] and even the mass of the surrounding dark matter halo Mhalo [6]. This review will focus on the MBH-σe relation, where σe is the stellar velocity dispersion inferred from spectral absorption lines (see [18], Chapter 2).

The MBH-σe relation has attracted the attention of the astronomical community since its discovery [15], as it is believed to be closely connected to the galaxy/halo gravitational potential well, and thus may be related to the above-mentioned AGN feedback process [12], as further discussed in section 3.2. The relation is of the form:

Ferrarese and Merritt [15] initially retrieved a normalization and slope of, respectively, α = 8.14 ± 1.80 and β = 4.80 ± 0.54, whereas more recent work (e.g., [19]) suggests α = 8.21 ± 0.06 and β = 3.83 ± 0.21. There is some debate in the literature concerning the exact shape of the MBH-σe and its dependence on, for example, morphological type or even environment (see e.g., [20–22] for more details). It has been noted (e.g., [23]) that several overmassive black holes exist on this relation, hosted by galaxies that have undergone fewer than usual mergers, in tension with semi-analytic models [10]. However, these outliers could simply be the result of incorrect modeling of the galactic bulge/disc [24].

Several groups have noted that the MBH-σe relation only weakly evolves with redshift (if at all) (e.g., [25–27]). Supporting work by other groups base their conclusions on direct estimates of the MBH-σe relation on high redshift quasar samples [28], and studies based on comparing the cumulative accretion from AGN with the local black hole mass density, retrieved from assigning to all local galaxies a black hole mass via the MBH-σe relation (e.g., [29, 30]).

On the assumption that all local galaxies host a central black hole, scaling relations could in principle allow us to assign black hole masses to all local galaxies without a direct dynamical mass measurements, thus generating large-scale black hole mass statistical distributions, such as black hole mass functions or correlation functions (see [31, 32] for more focused reviews on this topic). For example, a number of groups have used luminosity, as performed by Shankar et al. [33], Salucci et al. [34], and Marconi et al. [35], or even Sersic index, as performed by Graham et al. [36], to generate black hole mass functions. This procedure of course relies on two assumptions: firstly, that the observer has correctly identified the surrogate observable of black hole mass, and secondly that the established scaling relation is reliable. For example, the MBH-σe and MBH-Lbulge, probably the most commonly used relations, have led to different black hole mass function estimates [19, 37].

An important question is whether the same black hole-galaxy scaling relations hold for both active and inactive galaxies. Several groups suggest that this is indeed the case (e.g., [38–40]). It is important to stress that the samples of nearby (inactive) galaxies on which the black hole-host galaxy relations are based, still remain relatively small, only comprising around ~70–80 objects. A key difficulty relies of course in acquiring sufficiently high-resolution data to allow for dynamical black hole mass measurements (see [1, 2, 41] for reviews of observational challenges).

Indeed, there is a growing body of work [40, 42–46] supporting the view that current dynamical black hole mass samples may indeed be “biased-high,” possibly due to angular resolution selection effects (see [47]), with meaningful consequences for any study based on the “raw” relations. Interestingly, Shankar et al. [44] showed that, via aimed Monte Carlo simulations, irrespective of the presence of an underlying resolution bias, the raw and “de-biased” scaling relations would still share similar slopes and overall statistical properties (e.g., very similar residuals around the mean), with (noticeable) differences arising only in the normalization between observed and de-biased scaling relations. In particular, the MBH-σe was shown to be more robust and the least affected by possible angular resolution effects.

The main aim of this work is 3-fold: (i) to review the evidence in favor of the primary importance of the MBH-σe relation above other black hole scaling relations, (ii) to provide further support to velocity dispersion as the main host galaxy property driving the connection between black holes an their hosts, and iii) to review the main theoretical scenarios that give rise to the MBH-σe relation, with a focus on momentum-driven outflows. In sections 2.2 and 2.3 we will describe original evidence based on residuals and principle component analysis (respectively) in support of the primary role played by MBH-σe. In section 3 we include a description of the theoretical scenarios behind the physical origin of the MBH-σe relation. We then conclude in section 4.

Where cosmological parameters are required, we set h = 0.7, Ωm = 0.3, and ΩΛ = 0.7.

2. The Case for Velocity Dispersion

2.1. Review of Previous Work

Standard regression analyses showed that the MBH-σe has the lowest intrinsic scatter of any black hole scaling relation (e.g., [8, 48, 49]). This alone suggests σe is different from other variables. [50] came to the conclusion that MBH was fundamentally driven by σe due to its relative tightness. This work also tested the possibility for multi-dimensional relations, concluding that the introduction of additional variables barely reduced the scatter with respect to the MBH-σe, suggesting that stellar velocity dispersion remains a fundamental driving parameter. The amount of scatter characterizing diverse black hole scaling relations has been studied by several groups [16, 51]. Marconi and Hunt [16] and Hopkins et al. [51] explored the addition of the effective radius Re to σe to create a “fundamental plane” in the black hole scaling relations, further discussing in Hopkins et al. [52] how this relation naturally arises in their simulations, as a (tilted) correlation between black hole mass and bulge binding energy. This conclusion was supported by Saglia etal. [48], who argued for a multidimensional relation deriving from the bulge kinetic energy (), as originally suggested by Feoli and Mele [53].

de Nicola et al. [54] presented a systematic study of black hole scaling relations on an improved sample of local black holes, confirming that “the correlation with the effective velocity dispersion is not significantly improved by higher dimensionality.” The authors concluded that the MBH-σe is fundamental over multidimensional alternatives, independent of bulge decompositions. This is in line with van den Bosch [49], who claimed that the MBH-Mbulge is mostly a projection of the MBH-σe relation.

On more general grounds it has been suggested that, in terms of galactic scaling relations, velocity dispersion may be statistically more significant and relevant than other galaxy observables (e.g., [55, 56]). Bernardi et al. [57] analyzed the color-magnitude-velocity dispersion relation of a early-type galaxy sample of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), concluding that color-magnitude relations are entirely a consequence of the combination of more fundamental correlations with velocity dispersion.

Bernardi et al. [42] noted that the MBH-σe and MBH-Lbulge predict different abundances of black holes, with the former predicting a smaller number of more massive black holes. Interestingly, the combined σe-L relation (for the dynamically measured black hole sample, e.g., [58]) is inconsistent with the same relation from the SDSS, with smaller Lbulge for given σe (regardless of the band used to estimate luminosity). This suggests that the dynamical sample of local black holes may be biased toward objects with higher velocity dispersion when compared to local galaxies of similar luminosity, which obviously calls into question the accuracy of the raw MBH-σe and MBH-Lbulge relations. While unable to identify the source of the bias, modeling of this effect by Bernardi et al. [42] and Shankar et al. [44] suggested that the bias in the MBH-σe is likely to be small, whereas the MBH-Lbulge is likely to predict over-massive black holes at a fixed galaxy (total) luminosity/stellar mass.

2.2. Residuals Analysis

We start by revisiting the residual analysis on the black hole scaling relations following the method outlined in Shankar et al. [40, 44, 45]. Residuals in pairwise correlations [59] allow for a statistically sound approach to probe the relative importance among variables in the scaling with black hole mass. Residuals are computed as

where the residual is computed in the Y variable (at fixed X) from the log-log-linear fit of Y(X) vs. X, i.e., 〈log Y|log X〉. For each pair of variables, each residual is computed 200 times, and at each iteration five objects at random are removed from the original sample. From the full ensemble of realizations, we then measure the mean slope and its 1σ uncertainty.

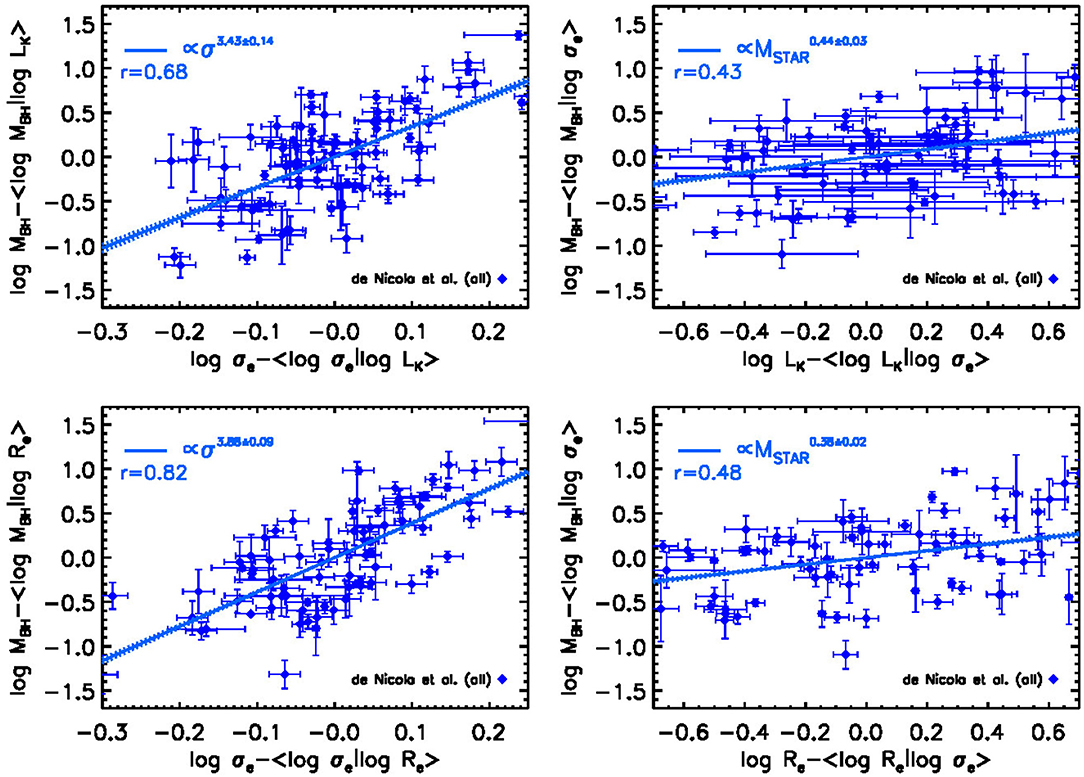

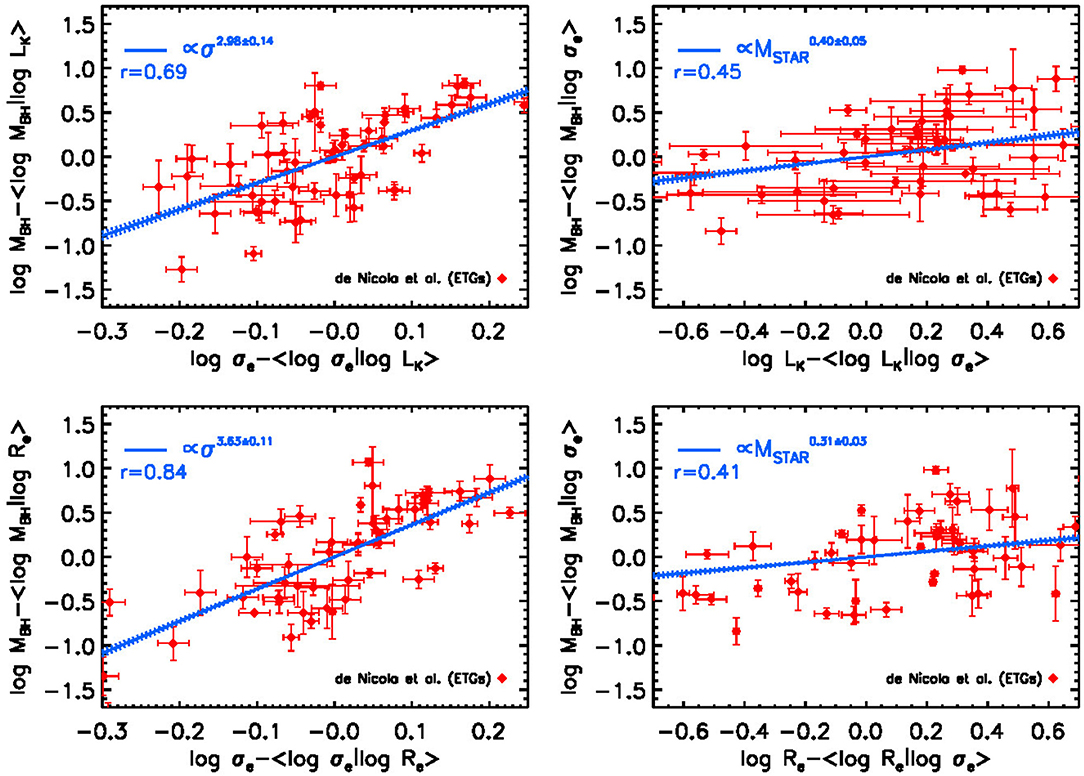

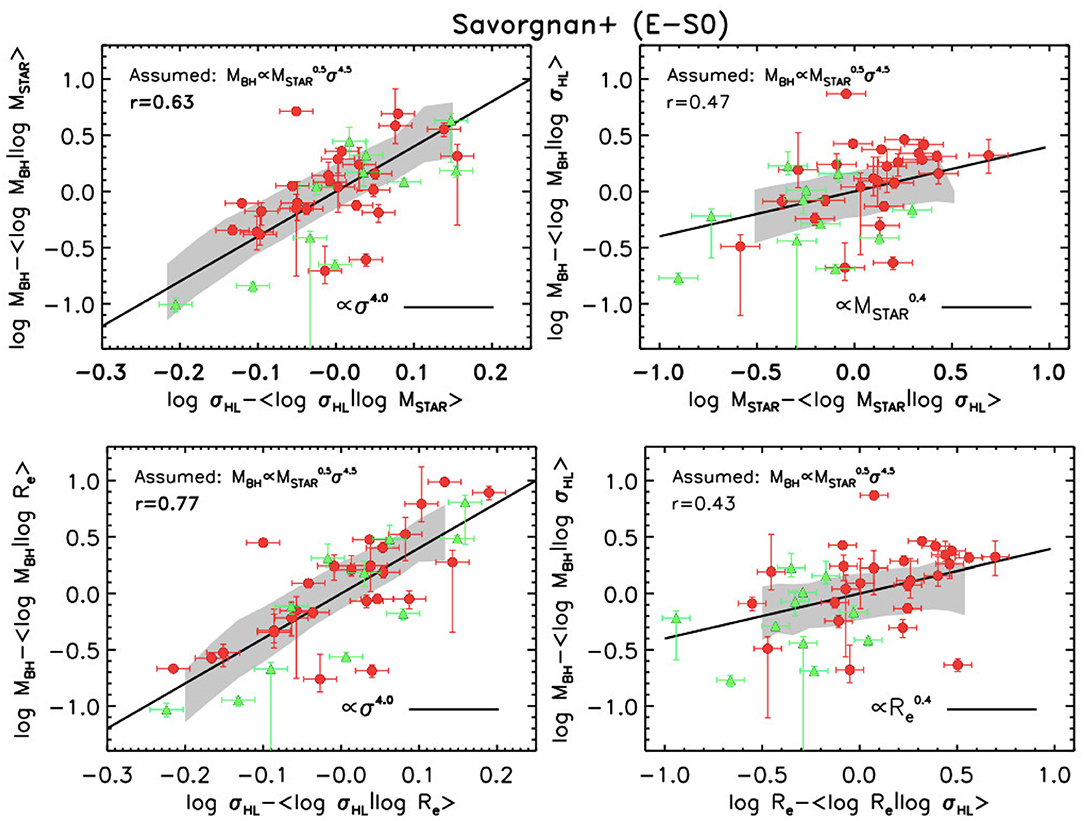

Our results are shown in Figures 1, 2, which show the residuals extracted from the recent homogeneous sample calibrated by de Nicola et al. [54]. Figure 1 shows that black hole mass strongly correlates with velocity dispersion at fixed galaxy luminosity with a Pearson coefficient r ~ 0.7 (top left panel), and even more so at fixed effective radius with r ~ 0.8 (bottom left panel), while the corresponding correlations with stellar luminosity or effective radius are significantly less strong with r ~ 0.4 at fixed velocity dispersion (right panels). Figure 2 shows the residuals restricting the analysis to only early type galaxies (red circles). The residuals appear quite similar in both slopes and related Pearson coefficients. These results further support the findings by Shankar et al. [44] (shown, for comparison, in Figure 3) that velocity dispersion is more fundamental than effective radius and stellar mass, and that even disc-dominated galaxies follow similar scaling relations.

Figure 1. Correlations between residuals from the observed scaling relations, as indicated. The residuals are extracted from the recent homogeneous sample calibrated by de Nicola et al. [54]. It can be clearly seen that black hole mass is strongly correlated with velocity dispersion at fixed galaxy luminosity with a Pearson coefficient r ~ 0.7 (top left panel), and even more so at fixed effective radius with r ~ 0.8 (bottom left panel). Correlations with other relations appear less strong (right panels).

Figure 2. Identical analysis to Figure 1, but only early type galaxies. Correlations with velocity dispersion are comparable.

Figure 3. Figure 5 from Shankar et al. [44] showing correlations between residuals. Correlations with velocity dispersion (left panels) appear to be stronger than other relations. The data is from the sample of Savorgnan et al. [60].

The total slope of the MBH-σe relation can be estimated as , where γ comes from . Since SDSS galaxies tend toward γ ≈ 2.2 [45], and the residuals in Figure 1 yield β ~ 3 and α ~ 0.4, one obtains a total dependence of , consistent with models of black hole growth being regulated by AGN feedback, as further discussed in section 3.2 (e.g., [11, 12, 61, 62]).

2.3. PCA Analysis

We will now present additional original work in favor of the MBH-σe being more fundamental, via Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [63], which is a powerful complementary statistical technique to the residuals analysis presented above. PCA is a mathematical procedure that diagonalizes the covariance matrix of variables in a dataset, providing a set of uncorrelated linearly transformed parameters, called principal components, defined by a set of orthogonal eigenvectors. The new orientation ensures that the first principal component (PC1) contains as much as possible of the variance in the data, and that the maximum of the remaining variance is contained in each succeeding orthogonal principal component (PC2, PC3, etc.). In other words, PCA finds the optimal projection of a number of (possibly correlated) physical observables into a smaller number of uncorrelated variables, revealing which quantities are more responsible for the variance (or, in some sense, for the information) in the dataset. PCA has been widely adopted in extragalactic astronomy, for instance to search for possible dimensionality reduction of the parameter space necessary to describe a sample (e.g., [64, 65]) or to study the mutual dependencies between observed gas- and metallicity-based galaxy scaling relations (e.g., [66–68]). Here we use PCA as an alternative technique to explore the black hole scaling relations. In detail, by quantifying through PCA the robustness of the correlations between MBH and, in turn, σe, L (total luminosity), and Re (the bulge effective radius), we can infer which of these observables provides a more fundamental scaling relation.

2.3.1. Black Hole Scaling Relations

In the PCA analysis we continue to use the dataset from de Nicola et al. [54]. To ensure that quantities with a higher dispersion are not over-weighted, we normalize our variables to their mean values, dividing by the standard deviation of their distributions. We therefore define the new variables (for convenience, in what follows we simply define L = LK):

We perform three different PCA on the 2D-space datasets formed by MBH and, in turn, one among σe, L and Re. The resulting principal component coefficients are reported in Table 1. We account for uncertainties in our results following a commonly adopted method (see e.g., [66, 68]). We perform a Monte Carlo bootstrap running 105 iterations, in each of which we perturb all the analyzed quantities by an amount randomly extracted in a range of values defined by their respective measurement errors. Thus, the reported principal component's coefficients and their errors are computed, respectively, from the average and the standard deviation of the values obtained over all the iterations.

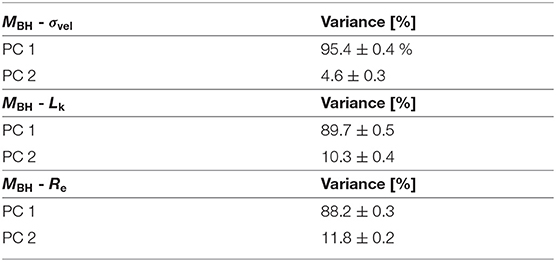

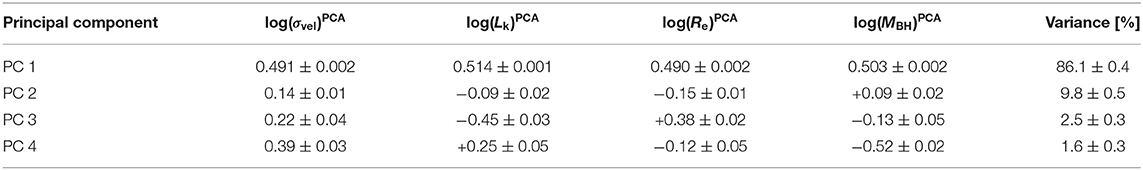

Table 1. The variance percentages contained by the principal components resulting from our PCA on the three 2D-datasets, MBH-σvel, MBH-Lk and MBH-Re, are reported.

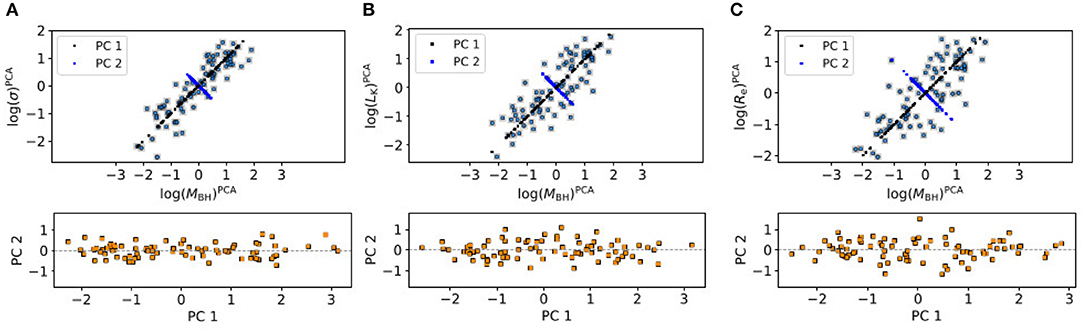

In the upper panels of Figure 4 we show the determined mutually orthogonal eigenvectors drawn onto the planes defined by the 2D-space datasets consisting of log(MBH)PCA and, in turn, log(σe)PCA, log(L)PCA, and log(Re)PCA. The three datasets, projected into the principal components, are shown in the lower panels of Figure 4. We find that, although in all three cases PC2 contains only a small fraction of the total variance (see Table 1), confirming that an overall good physical correlation exists among the variables, in the MBH-σe relation PC2 is minimized and the dataset can be very well-described uniquely by the PC1. In detail, we find that in the MBH-σe relation 95.4 ± 0.4% of the variance is contained into PC1 (with the little remaining information contained in PC2), while lower amount of variance are contained in the PC1 of the MBH - L relation (89.7 ± 0.5%) and in the PC1 of the MBH - Re relation (88.2 ± 0.3 %).

Figure 4. Upper panels: the orientations of the mutually orthogonal eigenvectors resulting from our 2D-space PCA are drawn onto the log(MBH)PCA-log(σe)PCA (A), log(MBH)PCA-log(Lk)PCA (B), and log(MBH)PCA-log(Re)PCA (C) planes. Lower panels: the projections of the three 2D-space datasets into the principal components are shown.

Since in all the three cases PC2 contains a little variance, we can set it to zero to obtain a linear approximation of the correlation among our observables from the PCA projected datasets. Thus, we obtain the following PCA model predictions:

where the non-normalized variables are restored (as defined in the equations discussed above), and the errors on the parameters are computed propagating the uncertainties on the principal component coefficients and on the mean values of the distributions.

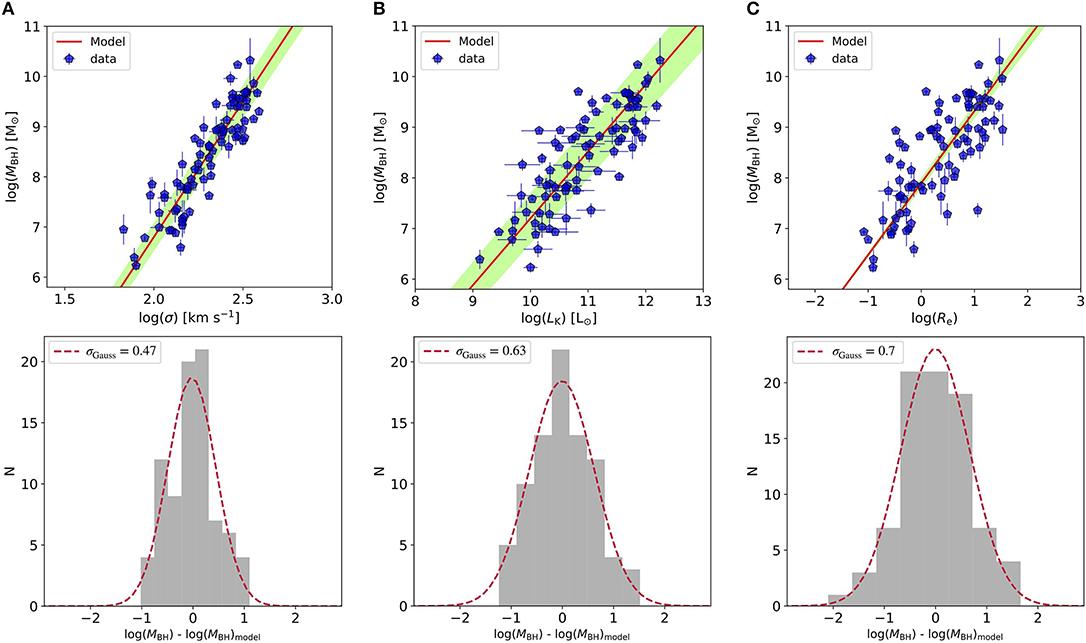

In the upper panels of Figure 5 we show a comparison between the observations in our 2D-space datasets and the PCA model relations, while in the lower panels we show the distributions of the corresponding residuals. We find that the relation for which our PCA model can better reproduce the data is the MBH - σe, with a Gaussian 1σ scatter of σ ~ 0.47. For the MBH - L and MBH - Re relations, our PCA model yields larger scatters in the residuals, respectively σ ~ 0.63 and σ ~ 0.7. These larger scatters are linked to the lower variance contained by PC1 in the samples respect to the MBH - σe case, and therefore a more significant loss of information when setting PC2 to zero.

Figure 5. Upper panels: a comparison between observations (blue points) and the 2D-space PCA model predictions (red lines) of the MBH - σe (A), MBH - Lk (B), and MBH - Re (C) relations is shown. The green shaded regions represent the scatters on the model relations. Lower panels: the distributions of the residuals are shown (gray histograms), along with their Gaussian fits (red dashed lines).

Altogether, our 2D-space PCA analysis suggests that, among σe, L and Re, σe is the observable that better correlates with MBH. The MBH-σe is the more fundamental scaling relation, with more than 95% of the information contained in the PC1 and only a scatter of σ ≲ 0.5 in the residuals between the data and the PCA model relation.

2.3.2. 4D-Space PCA

As a complementary way of exploring the mutual dependencies among the observables in our sample, we perform a PCA in the 4D-space defined by MBH, σe, L and Re.

We find that PC1 contains 86.1 ± 0.4% of the variance, confirming that the full set of four observables can be approximately well-described by a 2D surface. PC2 contains 9.8 ± 0.4% of the variance, meaning that accounting for a third dimension could recover ~10 % of the information, while PC3 and PC4 contains only ~2% (see Table 2). Following the same scheme discussed in section 2.3.1, setting to zero the PC that contain less variance, we obtain the best PCA model relation that expresses MBH in terms of the other observables in the dataset:

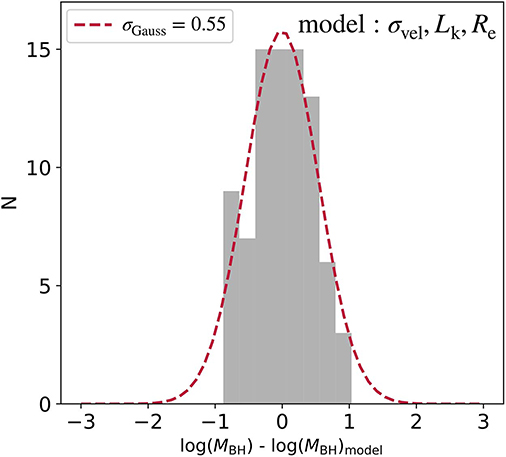

Consistently with the result obtained in section 2.3.1, we find that the primary dependence is attributed to σe, i.e., the quantity that better describes MBH. L and Re have a secondary and tertiary dependence, respectively, with relatively much lower weights (~16 and ~10%, computed as the ratios between the coefficients) with respect to σe Interestingly, as shown in Figure 6, the residuals obtained from the 4D-space PCA model relation are worse (σ ~ 0.55) than in the 2D-space PCA model relation obtained trough the optimal projection of the MBH-σe space. This effect is likely to be ascribed to some intrinsic noise introduced when adding Lk and Re in a 4D-space.

Table 2. The coefficients and the variance of the principal components resulting from our 4D-space (MBH-σe-L-Re) PCA are reported.

Figure 6. The distribution of the residuals computed subtracting the 4D-space PCA model predictions to the observed MBH is shown (gray histogram), along with its Gaussian fits (red dashed line).

3. Theoretical Perspective

As we have seen, a growing body of work is pointing to the fundamental importance of the MBH-σe. A key perspective that we have so far neglected in regards to black hole scaling relations is that of the theoretical modeller, which we will explore in this section.

The parameters of the galaxy that correlate with MBH tell us which physical processes are most important in setting the black hole mass. Each parameter is related to certain physical quantities. For example, velocity dispersion is naturally related to the mass of the galaxy's spheroidal component, and by extension to its gravitational potential. In the simplest case, modeling the bulge as an isothermal density profile, gas density is and its weight (the product of the gas mass and gravitational acceleration) is . Therefore, modeling a connection between the upper limit of the black hole mass and the weight of the gas surrounding it may indeed be a good starting point to explaining the correlation. Alternatively, if the SMBH mass were controlled by stellar processes, such as turbulence driven by stellar feedback, we would expect a strong correlation between MBH and stellar mass. Similarly, if the rate of SMBH feeding from large-scale reservoirs were an important constraint, a correlation with the bulge size Re or dynamical timescale tdyn ≃ Re/σe might emerge. The fact that such correlations are not seen suggests that these processes are secondary to the host's gravitational potential.

A very promising group of models that have emerged over the past two decades are those based on AGN feedback [11, 12, 69, 70]. The common argument is that AGN luminosity transfers energy to the surrounding gas and at some point drives it away, quenching further black hole growth. These models are generally capable of explaining not only the σe relation, but also the presence of quasi-relativistic nuclear winds and large-scale massive outflows observed in many active galaxies. Other models that presume either no causal connection between galaxy and black hole growth [71, 72] or those that claim the black hole to be merely a passive recipient of a fraction of the gas used to build up the bulge [73–75] make no predictions regarding outflows and generally connect the black hole mass to the mass, rather than velocity dispersion, of the galaxy bulge.

There are several ways of transferring AGN power to the surrounding gas, e.g., radiation, winds and/or jets [70]. Jets are typically efficient on galaxy cluster scales, heating intergalactic gas and prevent it from falling back into the galaxy [76]. This process, referred to as “maintenance mode” of feedback, prevents the SMBH mass from growing above the limit established by the MBH-σe relation. Jets are considered to be the primary form of feedback in AGN that accrete at low rates and have luminosities L < 0.01LAGN [77]. The opposite type of feedback is known as “quasar mode,” and it is believed to be most efficient in more luminous AGN. Here, again, there are two possibilities in which energy can be transferred. Directly coupling AGN luminosity to the gas in the interstellar medium is possible if the gas is dusty (due to a very high opacity, see [78]). On the other hand, dust evaporates when shocked to the temperatures expected within AGN outflows [79], potentially limiting the impact of radiation-driven outflows. A much more promising avenue is to connect the AGN with the surrounding gas via a quasi-relativistic wind [80]. Such a model naturally produces both a MBH-σe relation similar to the observed one, and outflow properties in excellent agreement with observations, both within galaxies [81–83] and on intergalactic scales in galaxy groups [84].

3.1. AGN Wind-Driven Feedback

AGN are highly variable on essentially all timescales and are known to occasionally reach the Eddington luminosity

where κe.s ≃ 0.346 cm2 g−1 is the electron scattering opacity. Under such circumstances, the geometrically thin accretion disc produces a quasi-spherical wind that self-regulates to an optical depth τ ~ 1 [85]. Therefore, each photon emitted by the AGN will, on average, scatter only once before escaping to infinity, and the wind carries a momentum rate

where Ṁw is the wind mass flow rate, vw is the wind velocity and LAGN ≡ lLEdd is the AGN luminosity, where l is the Eddington ratio. By writing , we find the wind velocity to be

where ≡ w/BH. The value of ṁ is highly uncertain, but should not be extremely different from unity. To see this, consider the extreme ends of the possible range of BH. If the accretion rate on to the accretion disc is significantly below Eddington, no wind is produced, while if the accretion rate rises above the Eddington limit, the wind moderates the accretion flow. Overall, the highest possible average accretion rate is the dynamical rate:

where fg ≃ 0.16 is the cosmological gas fraction and σ ≡ 200σ200 km s−1 is the velocity dispersion in the galaxy [80, 86]. In deriving the second equality, we used the MBH − σ relation that is derived below, in Equation (19). Therefore, in most cases, the SMBH feeding rate is not significantly higher than the Eddington rate, unless MBH is well below the observed relation. As a result, we take ṁ ~ 1 for the rest of this section. This leads to the final expression for the AGN wind velocity

which is very close to the average velocity in observed winds [87, 88]. The kinetic power of the wind is

The wind rapidly reaches the interstellar medium (ISM) surrounding the AGN and shocks against it. The shock is strong, since vw/σ ≫ 1, and the wind heats up to a temperature

where mp is the proton mass, and kb is the Boltzmann constant. The most efficient cooling process at this temperature is Inverse Compton (IC) cooling via interaction with AGN photons [89]. Most of the photons interact with electrons in the shocked wind, and a two-temperature plasma develops [89]. The actual cooling timescale then depends on the timescale for energy equilibration between electrons and protons. As a result, cooling is highly inefficient and the shocked wind can expand as an approximately adiabatic bubble.

The subsequent evolution of the expanding bubble depends on the density structure of the ISM. Most of the energy stored in the hot wind bubble escapes through the low-density channels and creates a large-scale outflow [90]. Denser clouds, however, remain and are mainly affected by the direct push of the wind material. These two situations create two kinds of outflow, known as energy-driven and momentum-driven, respectively. The latter kind is responsible for establishing the MBH − σe relation.

3.2. The Predicted Relation

Momentum-driven outflows push against the dense clouds surrounding the black hole. These clouds are the most likely sources of subsequent black hole feeding, therefore their removal quenches further black hole growth for a significant time and establishes the MBH-σe relation [62, 91, 92]. Considering the balance between AGN wind momentum and the weight of the gas Wgas leads to a critical AGN luminosity required for clearing the dense gas:

where the second equality assumes that the gas distribution and the background gravitational potential are isothermal, i.e., ρ = σ2/(2πGR2) [91]. Equating this critical luminosity with the Eddington luminosity of the black hole allows us to derive a critical mass [92]:

This value is very close to the observed one, although it has a slightly shallower slope. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that the black hole still grows during the time while it drives the gas away [93]. As the gas is pushed away, it joins the energy-driven outflow. This outflow coasts for approximately an order of magnitude longer than the AGN phase inflating it and stalls at a distance [94]

where tAGN is the duration of the driving phase and the energy-driven outflow velocity is [81, 95]

By equating Rstall with either the bulge radius or the virial radius of the galaxy, we obtain the time tAGN for which the galaxy must be active in order to quench further accretion on to the black hole and find , since R ∝ σe on average [this relation arises from the Fundamental plane of galaxies, see [96, 97]]. Note that this growth does not need to happen all at once: as long as the outflow is still progressing by the time the next episode begins, the system behaves as if it was powered by a continuously shining AGN [98].

This extra growth steepens the MBH-σe relation beyond the simpler analytical prediction and brings it more in line with observations [93]. Furthermore, it shows that galaxy radius may be an important secondary parameter determining the final black hole mass.

As a final note, the extra black hole growth while clearing the galaxy also depends on its spin. Since a rapidly spinning black hole produces more luminosity and drives a faster outflow than a slow-spinning one, the latter has to be active for longer and grow more before it clears the gas from the galaxy. Although present-day estimates of black hole spins are not robust or numerous enough to test this prediction in detail, this might become possible in the near future [99].

In general, theoretical models based on momentum-driven outflows are capable of naturally explaining the relationship between black hole mass and velocity dispersion, primarily due to the latter acting as a tracer of the host's gravitational potential well. In addition, these models could account for secondary, weaker dependencies on, e.g., galaxy stellar mass or size, which may still be allowed by current data as discussed above (see e.g., Figures 1, 5 and [44]).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper we have reviewed previous evidence for the MBH-σe being the most fundamental of all black hole-host galaxy scaling relations (among those discovered so far) and we have presented new evidence based on the statistical analysis of the sample recently compiled by de Nicola et al. [54]. Both residuals [(e.g., [44]) and PCA analyses point to σe being more fundamental than both stellar luminosity/mass or effective radius in their correlation to central black hole mass.

Theoretically, as reviewed by King and Pounds [80], the MBH-σe arises as a consequence of AGN feedback. In short, the black hole in these models is expected to grow until it becomes massive enough to drive energetic/high-momentum large-scale winds that can potentially remove residual gas, inhibiting further star formation and black hole growth. The limiting mass reached by the black hole, which ultimately depends on the potential well of the host, naturally provides an explanation for the existence of the MBH-σe relation.

Its fundamental nature and lower inclination toward selection biases [in comparison to other scaling relations, e.g., [44]] make the MBH-σe relation the ideal benchmark for statistical studies of black holes in a variety of contexts. The MBH-σe relation should always be the one adopted to constrain the fvir factor used in reverberation mapping studies (see e.g., [100]) to infer black hole masses from active galaxies (e.g., [40]). The MBH-σe relation also provides more robust large-scale clustering predictions in black hole mock catalogs [46]. Furthermore, pulsar timing array predictions of the gravitational wave background (e.g., [101]) are strongly dependent on the normalization of the black hole scaling relations [44, 102], but they should be based on the MBH-σe rather than on the MBH-M* relation (see [103]).

The shape and scatter of the MBH-σe relation could yield important information on the evolutionary channels of black hole growth. For example, its scatter could retain memory of the merger histories of the host galaxies [10]. More broadly speaking, global star formation and black hole growth from continuity equation argument modeling is known to peak at around z ~ 2 (e.g., [104, 105]). This is in itself consistent with the idea that black holes and their hosts may be co-evolving, and understanding how the MBH-σe relation precisely evolves over cosmic time or change as a function of environment could set invaluable constraints on the mechanisms behind black hole growth (e.g., [106–108]).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CM was the primary author and wrote the background and review sections. FS provided the supervision, edited the manuscript, and provided the calculations of the residuals. MG performed and wrote the section on PCA analysis. KZ wrote the section on theoretical models.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

CM acknowledges funding from the ESPRC for his Ph.D. FS acknowledges partial support from a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowship. We thank de Nicola and Alessandro Marconi for sharing their data in electronic format. We acknowledge extensive use of the Python libraries astropy, matplotlib, numpy, pandas, and scipy.

References

1. Ferrarese L, Ford H. Supermassive black holes in galactic nuclei: past, present and future research. Soc Sci Res. (2005) 116:523–624. doi: 10.1007/s11214-005-3947-6

2. Kormendy J, Ho LC. Coevolution (or not) of supermassive black holes and host galaxies. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. (2013) 51:511–653. doi: 10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101811

3. Magorrian J, Tremaine S, Richstone D, Bender R, Bower G, Dressler A, et al. The demography of massive dark objects in galaxy centers. Astron J. (1998) 115:2285–305. doi: 10.1086/300353

4. Häring N, Rix HW. On the Black Hole Mass-Bulge Mass Relation. Astrophys J Lett. (2004) 604: L89–92. doi: 10.1086/383567

5. Gebhardt K, Bender R, Bower G, Dressler A, Faber SM, Filippenko AV, et al. A relationship between nuclear black hole mass and galaxy velocity dispersion. Astrophys J Lett. (2000) 539:L13–6. doi: 10.1086/312840

6. Ferrarese L. Beyond the bulge: a fundamental relation between supermassive black holes and dark matter halos. Astrophys J. (2002) 578:90–7. doi: 10.1086/342308

7. Tremaine S, Gebhardt K, Bender R, Bower G, Dressler A, Faber SM, et al. The slope of the black hole mass versus velocity dispersion correlation. Astrophys J. (2002) 574:740–53. doi: 10.1086/341002

8. Gültekin K, Richstone DO, Gebhardt K, Lauer TR, Tremaine S, Aller MC, et al. The M-σ and M-L relations in galactic bulges, and determinations of their intrinsic scatter. Astrophys J. (2009) 698:198–221. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/698/1/198

9. McConnell NJ, Ma CP. Revisiting the scaling relations of black hole masses and host galaxy properties. Astrophys J. (2013) 764:184. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/764/2/184

10. Savorgnan GAD, Graham AW. Overmassive black holes in the MBH-σ diagram do not belong to over (dry) merged galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2015) 446:2330–2336. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu2259

12. Granato GL, De Zotti G, Silva L, Bressan A, Danese L. A physical model for the coevolution of QSOs and their spheroidal hosts. Astrophys J. (2004) 600:580–94. doi: 10.1086/379875

13. Peterson BM. An Introduction to Active Galactic Nuclei. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1997).

14. King A. Supermassive black hole accretion and feedback. Saas-Fee Adv Course. (2019) 48:95. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-59799-6_2

15. Ferrarese L, Merritt D. A fundamental relation between supermassive black holes and their host galaxies. Astrophys J Lett. (2000) 539:L9–12. doi: 10.1086/312838

16. Marconi A, Hunt LK. The relation between black hole mass, bulge mass, and near-infrared luminosity. Astrophys J Lett. (2003) 589:L21–4. doi: 10.1086/375804

17. Graham AW, Erwin P, Caon N, Trujillo I. A correlation between galaxy light concentration and supermassive black hole mass. Astrophys J Lett. (2001) 563:L11–4. doi: 10.1086/338500

18. Mo H, van den Bosch FC, White S. Galaxy Formation and Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2010).

19. Tundo E, Bernardi M, Hyde JB, Sheth RK, Pizzella A. On the inconsistency between the black hole mass function inferred from M∙-σ and M∙-L correlations. Astrophys J. (2007) 663:53–60. doi: 10.1086/518225

20. Lauer TR, Faber SM, Richstone D, Gebhardt K, Tremaine S, Postman M, et al. The masses of nuclear black holes in luminous elliptical galaxies and implications for the space density of the most massive black holes. Astrophys J. (2007) 662:808–34. doi: 10.1086/518223

21. Wyithe JSB. A log-quadratic relation between the nuclear black hole masses and velocity dispersions of galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2006) 365:1082–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2005.09721.x

22. Hu J. The black hole mass-stellar velocity dispersion correlation: bulges versus pseudo-bulges. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2008) 386:2242–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13195.x

23. van den Bosch RCE, Gebhardt K, Gültekin K, van de Ven G, van der Wel A, Walsh JL. An over-massive black hole in the compact lenticular galaxy NGC 1277. Nature. (2012) 491:729–31. doi: 10.1038/nature11592

24. Savorgnan GAD, Graham AW. Explaining the reportedly overmassive black holes in early-type galaxies with intermediate-scale discs. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2016) 457:320–7. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv2713

25. Gaskell CM. An improved [O III] line width to stellar velocity dispersion calibration: curvature, scatter, and lack of evolution in the black-hole mass versus stellar velocity dispersion relationship. arXiv. (2009) 0908.0328.

26. Salviander S, Shields GA. The black hole mass-stellar velocity dispersion relationship for quasars in the sloan digital sky survey data release 7. Astrophys J. (2013) 764:80. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/764/1/80

27. Shen Y, Greene JE, Ho LC, Brand tWN, Denney KD, Horne K, et al. The sloan digital sky survey reverberation mapping project: no evidence for evolution in the M∙−σ* relation to z 1. Astrophys J. (2015) 805:96. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/805/2/96

28. Woo J, Treu T, Malkan MA, Blandford RD. Cosmic evolution of black holes and spheroids. III. TheMBH-* relation in the last six billion years. Astrophys J. (2008) 681:925–30. doi: 10.1086/588804

29. Shankar F, Bernardi M, Haiman Z. The Evolution of the M BH−σ relation inferred from the age distribution of local early-type galaxies and active galactic nuclei evolution. Astrophys J. (2009) 694:867–78. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/867

30. Zhang X, Lu Y, Yu Q. The cosmic evolution of massive black holes and galaxy spheroids: global constraints at redshift z <-0.5ex~1.2. Astrophys J. (2012) 761:5. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/761/1/5

31. Shankar F. The demography of supermassive black holes: growing monsters at the heart of galaxies. New Astron Rev. (2009) 53:57–77. doi: 10.1016/j.newar.2009.07.006

32. Graham AW, Scott N. The (black hole)-bulge mass scaling relation at low masses. Astrophys J. (2015) 798:54. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/798/1/54

33. Shankar F, Salucci P, Granato GL, De Zotti G, Danese L. Supermassive black hole demography: the match between the local and accreted mass functions. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2004) 354:1020–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08261.x

34. Salucci P, Szuszkiewicz E, Monaco P, Danese L. Mass function of dormant black holes and the evolution of active galactic nuclei. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (1999) 307:637–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.02659.x

35. Marconi A, Risaliti G, Gilli R, Hunt LK, Maiolino R, Salvati M. Local supermassive black holes, relics of active galactic nuclei and the X-ray background. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2004) 351:169–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07765.x

36. Graham AW, Driver SP, Allen PD, Liske J. The millennium galaxy catalogue: the local supermassive black hole mass function in early- and late-type galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2007) 378:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.11770.x

37. Lauer TR, Tremaine S, Richstone D, Faber SM. Selection bias in observing the cosmological evolution of the M∙-σ and M∙-L relationships. Astrophys J. (2007) 670:249–60. doi: 10.1086/522083

38. Reines AE, Volonteri M. Relations between central black hole mass and total galaxy stellar mass in the local universe. Astrophys J. (2015) 813:82. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/813/2/82

39. Caglar T, Burtscher L, Brand B, Brinchmann J, Davies RI, Hicks EKS, et al. LLAMA: The MBH - −⋆ Relation of the Most Luminous Local AGNs. Les Ulis: EDP Sciences (2019).

40. Shankar F, Bernardi M, Richardson K, Marsden C, Sheth RK, Allevato V, et al. Black hole scaling relations of active and quiescent galaxies: addressing selection effects and constraining virial factors. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2019) 485:1278–92. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz376

41. Faber SM. The demography of massive galactic black holes. Adv Space Res. (1999) 23:925–36. doi: 10.1016/S0273-1177(99)00217-3

42. Bernardi M, Sheth RK, Tundo E, Hyde JB. Selection bias in the M∙-σ and M∙-L correlations and its consequences. Astrophys J. (2007) 660:267–75. doi: 10.1086/512719

43. van den Bosch RCE, Gebhardt K, Gültekin K, Yıldırım A, Walsh JL. Hunting for supermassive black holes in nearby galaxies with the Hobby-Eberly telescope. Astrophys J Suppl. (2015) 218:10. doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/218/1/10

44. Shankar F, Bernardi M, Sheth RK, Ferrarese L, Graham AW, Savorgnan G, et al. Selection bias in dynamically measured supermassive black hole samples: its consequences and the quest for the most fundamental relation. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2016) 460:3119–42. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw678

45. Shankar F, Bernardi M, Sheth RK. Selection bias in dynamically measured supermassive black hole samples: dynamical masses and dependence on Sérsic index. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2017) 466:4029–39. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw3368

46. Shankar F, Allevato V, Bernardi M, Marsden C, Lapi A, Menci N, et al. Constraining black hole-galaxy scaling relations from the large-scale clustering of active galactic nuclei and implied mean radiative efficiency. arXiv. (2019) 1910.10175. doi: 10.1038/s41550-019-0949-y

47. Merritt D. Dynamics and Evolution of Galactic Nuclei. Woodstock: Princeton University Press (2013).

48. Saglia RP, Opitsch M, Erwin P, Thomas J, Beifiori A, Fabricius M, et al. The SINFONI black hole survey: the black hole fundamental plane revisited and the paths of (co)evolution of supermassive black holes and bulges. Astrophys J. (2016) 818:47. doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/818/1/47

49. van den Bosch RCE. Unification of the fundamental plane and super massive black hole masses. Astrophys J. (2016) 831:134. doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/831/2/134

50. Beifiori A, Courteau S, Corsini EM, Zhu Y. On the correlations between galaxy properties and supermassive black hole mass. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2012) 419:2497–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19903.x

51. Hopkins PF, Hernquist L, Cox TJ, Robertson B, Krause E. An observed fundamental plane relation for supermassive black holes. Astrophys J. (2007) 669:67–73. doi: 10.1086/521601

52. Hopkins PF, Hernquist L, Cox TJ, Robertson B, Krause E. A theoretical interpretation of the black hole fundamental plane. Astrophys J. (2007) 669:45–66. doi: 10.1086/521590

53. Feoli A, Mele D. Is there a relationship between the mass of a Smbh and the kinetic energy of its host elliptical galaxy? Int J Mod Phys D. (2005) 14:1861–72. doi: 10.1142/S0218271805007528

54. de Nicola S, Marconi A, Longo G. The fundamental relation between supermassive black holes and their host galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2019) 490:600–12. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2472

55. Bernardi M, Roche N, Shankar F, Sheth RK. Curvature in the colour-magnitude relation but not in colour-σ: major dry mergers at M* > 2 1011 M? Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2011) 412:684–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17984.x

56. Bernardi M, Roche N, Shankar F, Sheth RK. Evidence of major dry mergers at M* > 2 1011 M from curvature in early-type galaxy scaling relations? Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2011) 412:L6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2010.00982.x

57. Bernardi M, Sheth RK, Nichol RC, Schneider DP, Brinkmann J. Colors, magnitudes, and velocity dispersions in early-type galaxies: implications for galaxy ages and metallicities. Astron J. (2005) 129:61–72. doi: 10.1086/426336

58. Yu Q, Tremaine S. Observational constraints on growth of massive black holes. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2002) 335:965–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05532.x

59. Sheth RK, Bernardi M. Plain fundamentals of fundamental planes: analytics and algorithms. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2012) 422:1825–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19757.x

60. Savorgnan GAD, Graham AW, Marconi Ar, Sani E. Supermassive black holes and their host spheroids. II. The red and blue sequence in the MBH-M*, sph diagram. Astrophys J. (2016) 817:21. doi: 10.3847/0004-637X/817/1/21

61. Fabian AC. The obscured growth of massive black holes. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (1999) 308:L39–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.03017.x

62. King A. Black Holes, Galaxy Formation, and the MBH-σ Relation. Astrophys J Lett. (2003) 596:L27–9. doi: 10.1086/379143

64. Lara-López MA, Cepa J, Bongiovanni A, Pérez García AM, Ederoclite A, Castañeda H, et al. A fundamental plane for field star-forming galaxies. Astron Astrophys. (2010) 521:L53. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201014803

65. Hunt L, Magrini L, Galli D, Schneider R, Bianchi S, Maiolino R, et al. Scaling relations of metallicity, stellar mass and star formation rate in metal-poor starburstsI. A fundamental plane. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2012) 427:906–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21761.x

66. Bothwell MS, Maiolino R, Peng Y, Cicone C, Griffith H, Wagg J. Molecular gas as the driver of fundamental galactic relations. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2016) 455:1156–70. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv2121

67. Hunt L, Dayal P, Magrini L, Ferrara A. Coevolution of metallicity and star formation in galaxies to z ~ 3.7I. A fundamental plane. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2016) 463:2002–19. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stw1993

68. Ginolfi M, Hunt LK, Tortora C, Schneider R, Cresci G. Scaling relations and baryonic cycling in local star-forming galaxies. arXiv. (2019) 1907.06654.

69. Harrison CM. Impact of supermassive black hole growth on star formation. Nat Astron. (2017) 1:0165. doi: 10.1038/s41550-017-0165

71. Peng CY. How mergers may affect the mass scaling relation between gravitationally bound systems. Astrophys J. (2007) 671:1098–107. doi: 10.1086/522774

72. Jahnke K, Macciò AV. The non-causal origin of the black-hole-galaxy scaling relations. Astrophys J. (2011) 734:92. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/734/2/92

73. Haan S, Schinnerer E, Emsellem E, García-Burillo S, Combes F, Mundell CG, et al. Dynamical evolution of AGN host galaxies in/out-flow rates in seven NUGA galaxies. Astrophys J. (2009) 692:1623–61. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/692/2/1623

74. Anglés-Alcázar D, Özel F, Davé R. Black hole-galaxy correlations without self-regulation. Astrophys J. (2013) 770:5. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/770/1/5

75. Anglés-Alcázar D, Özel F, Davé R, Katz N, Kollmeier JA, Oppenheimer BD. Torque-limited growth of massive black holes in galaxies across cosmic time. Astrophys J. (2015) 800:127. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/800/2/127

76. McNamara BR, Nulsen PEJ. Heating hot atmospheres with active galactic nuclei. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. (2007) 45:117–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.astro.45.051806.110625

77. Merloni A, Heinz S. Measuring the kinetic power of active galactic nuclei in the radio mode. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2007) 381:589–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2007.12253.x

78. Fabian AC, Vasudevan RV, Gandhi P. The effect of radiation pressure on dusty absorbing gas around active galactic nuclei. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2008) 385:L43–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00430.x

79. Barnes DJ, Kannan R, Vogelsberger M, Marinacci F. Radiative AGN feedback on a moving mesh: the impact of the galactic disc and dust physics on outflow properties. arXiv. (2018).

80. King A, Pounds K. Powerful outflows and feedback from active galactic nuclei. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys. (2015) 53:115–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev-astro-082214-122316

81. Zubovas K, King A. Clearing out a galaxy. Astrophys J Lett. (2012) 745:L34. doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/745/2/L34

82. Cicone C, Maiolino R, Sturm E, Graciá-Carpio J, Feruglio C, Neri R, et al. Massive molecular outflows and evidence for AGN feedback from CO observations. Astron Astrophys. (2014) 562:A21. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322464

83. Menci N, Fiore F, Feruglio C, Lamastra A, Shankar F, Piconcelli E, et al. Outflows in the disks of active galaxies. Astrophys J. (2019) 877:74. doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab1a3a

84. Lapi A, Cavaliere A, Menci N. Intracluster and intragroup entropy from quasar activity. Astrophys J. (2005) 619:60–72. doi: 10.1086/426376

85. King AR, Pounds KA. Black hole winds. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2003) 345:657–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06980.x

86. King AR. AGN have underweight black holes and reach Eddington. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2010) 408:L95–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2010.00938.x

87. Tombesi F, Cappi M, Reeves JN, Palumbo GGC, Yaqoob T, Braito V, et al. Evidence for ultra-fast outflows in radio-quiet AGNs. I. Detection and statistical incidence of Fe K-shell absorption lines. Astron Astrophys. (2010) 521:A57. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/200913440

88. Tombesi F, Sambruna RM, Reeves JN, Braito V, Ballo L, Gofford J, et al. Discovery of ultra-fast outflows in a sample of broad-line radio galaxies observed with Suzaku. Astrophys J. (2010) 719:700–15. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/719/1/700

89. Faucher-Giguère CA, Quataert E. The physics of galactic winds driven by active galactic nuclei. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2012) 425:605–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21512.x

90. Zubovas K, Nayakshin S. Energy- and momentum-conserving AGN feedback outflows. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2014) 440:2625–35. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu431

91. Murray N, Quataert E, Thompson TA. On the maximum luminosity of galaxies and their central black holes: feedback from momentum-driven winds. Astrophys J. (2005) 618:569–85. doi: 10.1086/426067

92. King AR. Black hole outflows. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2010) 402:1516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.16013.x

93. Zubovas K, King AR. The M-σ relation in different environments. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2012) 426:2751–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21845.x

94. King AR, Zubovas K, Power C. Large-scale outflows in galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2011) 415:L6–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3933.2011.01067.x

95. King A. The AGN-starburst connection, galactic superwinds, and MBH−σ. Astrophys J Lett. (2005) 635:L121–3. doi: 10.1086/499430

96. Djorgovski S, Davis M. Fundamental properties of elliptical galaxies. Astrophys J. (1987) 313:59–68. doi: 10.1086/164948

97. Cappellari M, Scott N, Alatalo K, Blitz L, Bois M, Bournaud F, et al. The ATLAS3D project-XV. Benchmark for early-type galaxies scaling relations from 260 dynamical models: mass-to-light ratio, dark matter, fundamental plane and mass plane. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2013) 432:1709–41. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stt562

98. Zubovas K. Tidal disruption events can power the observed AGN in dwarf galaxies. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2019) 483:1957–69. doi: 10.1093/mnras/sty3211

99. Zubovas K, King A. Slow and massive: low-spin SMBHs can grow more. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2019) 489:1373–8. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stz2235

100. Vestergaard M, Peterson BM. Determining central black hole masses in distant active galaxies and quasars. II. Improved optical and UV scaling relationships. Astrophys J. (2006) 641:689–709. doi: 10.1086/500572

101. Kramer M, Champion DJ. The European pulsar timing array and the large European array for pulsars. Classic Quant Gravity. (2013) 30:224009. doi: 10.1088/0264-9381/30/22/224009

102. Sesana A, Vecchio A, Colacino CN. The stochastic gravitational-wave background from massive black hole binary systems: implications for observations with pulsar timing arrays. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2008) 390:192–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13682.x

103. Rosado PA, Sesana A, Gair J. Expected properties of the first gravitational wave signal detected with pulsar timing arrays. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2015) 451:2417–33. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv1098

104. Shankar F, Weinberg DH, Miralda-Escudé J. Self-consistent models of the AGN and black hole populations: duty cycles, accretion rates, and the mean radiative efficiency. Astrophys J. (2009) 690:20–41. doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/20

105. Delvecchio I, Gruppioni C, Pozzi F, Berta S, Zamorani G, Cimatti A, et al. Tracing the cosmic growth of supermassive black holes to z 3 with Herschel. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2014) 439:2736–54. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu130

106. Hirschmann M, Dolag K, Saro A, Bachmann L, Borgani S, Burkert A. Cosmological simulations of black hole growth: AGN luminosities and downsizing. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2014) 442:2304–24. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu1023

107. Fontanot F, Monaco P, Shankar F. Interpreting the possible break in the black hole-bulge mass relation. Mon Not R Astron Soc. (2015) 453:4112–20. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv1930

Keywords: supermassive black holes, velocity dispersion, galaxies, scaling relations, principal component analysis

Citation: Marsden C, Shankar F, Ginolfi M and Zubovas K (2020) The Case for the Fundamental MBH-σ Relation. Front. Phys. 8:61. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2020.00061

Received: 20 December 2019; Accepted: 26 February 2020;

Published: 17 March 2020.

Edited by:

Elisabeta Lusso, University of Florence, ItalyReviewed by:

Antonio Feoli, University of Sannio, ItalySusanna Bisogni, Harvard University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Marsden, Shankar, Ginolfi and Zubovas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Christopher Marsden, Yy5tYXJzZGVuQHNvdG9uLmFjLnVr

Christopher Marsden

Christopher Marsden Francesco Shankar

Francesco Shankar Mitchele Ginolfi

Mitchele Ginolfi Kastytis Zubovas

Kastytis Zubovas