Abstract

There is a growing discussion in the legal literature of an emerging global community of courts composed of a network of increasing judicial dialogue across national borders. We investigate the use of foreign persuasive authority in common law countries by analyzing the network of citations to case law in a corpus of over 1.5 million judgments given by the senior courts of twenty-six common law countries. Our corpus of judgments is derived from data available in the vLex Justis database. In this paper we aim to quantify the flow of jurisprudence across the countries in our corpus and to explore the factors that may influence a judge’s selection of foreign jurisprudence. Utilization of foreign case law varies across the countries in our data, with the courts of some countries presenting higher engagement with foreign jurisprudence than others. Our analysis shows that there has been an upward trend in the use of foreign case law over time, with a marked increase in citations across national borders from the 1990s onward, potentially indicating that increased digital access to foreign judgments has served to facilitate and promote comparative analysis. Not only has the use of foreign case law generally increased over time, the factors that may influence the selection of case law have also evolved, with judges gradually casting their research beyond the most influential and well-known foreign authorities. Notwithstanding that judgments emanating from the United Kingdom (chiefly from the courts of England and Wales) constitute the most frequently consulted body of jurisprudence, we find evidence that domestic courts favor citing the case law of countries that are geographically proximal.

1 Introduction

There is a growing discussion in the legal literature of an emerging “global community of courts” composed of a network of increasing judicial dialogue across borders [1–3]. Here we investigate the use of foreign persuasive authority in common law systems by analyzing the network of citations to foreign case law in a corpus of over 1.5 million judgments of the senior courts of twenty-six common law countries. Our corpus of judgments is derived from the vLex Justis database 1. In this paper we aim to quantify the flow of jurisprudence across the countries in our corpus and to explore factors that may influence a judge’s selection of foreign case law.

A fundamental feature of common law legal systems is the doctrine of precedent, which places a binding obligation on judges to follow principles established by coordinate and superior courts in earlier similar cases. This binding obligation to follow the decisions of courts of equal and higher standing (mandatory authorities) stands in contrast to the concept of persuasive authority (optional authority), the most common example of which are decisions of foreign national courts [4].

The concept of persuasive authority is well-known but imprecise [5], yet there has been growing consensus among legal scholars since the late-1990s that “more and more courts, particularly within the common law world, are looking to the judgments of other jurisdictions” [1].

The practice of cross-jurisdictional citation of persuasive authority sits within the broader context of the emergence of what Slaughter describes as a “global community of courts” [2]–the formation of which has been driven by a range of factors, including increasing similarities between the issues facing courts around the world; the international nature of human rights and the proliferation of international courts and tribunals; advances in technology and vastly improved accessibility of foreign jurisprudence; and increased personal contact among judges [1].

Slaughter acknowledges that the phenomenon of “cross-pollination” of judicial thinking via the citation of one nation’s jurisprudence by another is not new and is well established in the Commonwealth [2]. However, Claire L’Heureux-Dubé, a former justice of the Canadian Supreme Court, observes that the contemporary “process of international influences has changed from reception to dialogue. Judges no longer simply receive the cases of other jurisdictions and then apply them or modify them for their own jurisdiction.”[1] Instead, according to L’Heureux-Dubé, “... cross-pollination and dialogue between jurisdictions is increasingly occurring. As judgments in different countries build on each other, mutual respect and dialogue are fostered among appellate courts. Judges around the world look to each other for persuasive authority, rather than some judges being “givers” of law while others are “receivers”. Reception is turning to dialogue [1].”

The cross-pollination of judicial thinking via the citation of optional, yet persuasive, foreign judgments occurs horizontally between nations independently of the doctrine of precedent as opposed to vertically between nations and the decisions of their supranational counterparts by which the national court is either bound2 or at the very least obligated to take into account.3

There is ample support for L’Heureux-Dubé’s conception of judicial dialogue between nations to be found in the decisions of senior common law courts. For example, in the United Kingdom House of Lords case of Fairchild v Glenhaven Funeral Services Ltd.4, which concerned the issue of causation of mesothelioma arising from the appellant’s exposure to asbestos during different periods of employment in breach of each employer’s duty of care, Lord Bingham, having conducted a survey of case law from Australia, South Africa, the United States, France, Germany and Canada, said: “Development of the law in this country cannot of course depend on a head-count of decisions and codes adopted in other countries around the world ... The law must be developed coherently, in accordance with principle, so as to serve, even-handedly, the ends of justice. If, however, a decision is given in this country which offends one’s basic sense of justice, and if consideration of international sources suggests that a different and more acceptable decision would be given in most other jurisdictions, whatever their legal tradition, this must prompt anxious review of the decision in question. In a shrinking world ... there must be some virtue in uniformity of outcome whatever the diversity of approach in reaching that outcome 5.”

Similar sentiments have been expressed, extra-judicially, by former justices of the Canadian Supreme Court [6] and the High Court of Australia [7]. However, the phenomenon of participation in cross-jurisdictional dialogue is not universally embraced. For example, in the United States Supreme Court case of Foster v Florida, 6 in which a death-row inmate sought a writ of certiorari on the grounds that the lengthy delay between his sentencing and execution constituted a violation of his Eighth Amendment rights against cruel and unusual punishment, Justice Thomas denigrated Justice Breyer’s willingness to cite foreign authorities, stating: “While Congress, as a legislature, may wish to consider the actions of other nations on any issue it likes, this Court’s Eighth Amendment jurisprudence should not impose foreign moods, fads, or fashions on Americans 7.”

The discourse in academic articles and the cases themselves present a mixed picture where the use of foreign case law is concerned. The courts of some countries, notably Australia and Canada, appear to have taken advantage of increased access to case law from around the world to engage in comparative analysis and dialogue. However, other common law jurisdictions, most notably the US, appear to have adopted a more restrictive approach to the citation of foreign jurisprudence, rarely reaching beyond their borders when seeking guidance on legal issues [8].

A lack of access to judgment data the spans multiple common law systems has made it difficult to analyze the use of foreign case law at scale. Most earlier work has therefore concentrated on the analysis of interactions with foreign case law by a specific court or a specific territorial jurisdiction, such as the United States. This paper utilizes the case law citation network derived from a substantial corpus of senior and appellate court judgments from twenty-six common law countries to examine how, and to what extent, domestic courts in common law jurisdictions make use of foreign case law. We anchor our analysis in the overarching theme that there is an emerging global community of courts composed of a network of judicial dialogue flowing between national courts via the mechanism of citation to persuasive foreign case law.

We make five core findings. First, the use of foreign case law has followed a consistent upward trend throughout the 20th century to the present, with a pronounced increase in foreign case law utilization from 1990 onward. The timing of this increase appears to correspond to the rise of digital platforms that facilitate more comprehensive and low-cost systems of case law dissemination and retrieval. Second, although all of the countries we examine participate in the citation of foreign case law, the extent to which they do varies, with some countries making more frequent reference to foreign cases than others. Third, while there is evidence of a historical preference among judges to cite foreign cases that are highly influential in their own domestic jurisprudence, this pattern has given way to citation behavior that potentially indicates a shift in attitudes toward the citation of less well-known cases. This shift corresponds to a rapid expansion in the citation networks that is likely attributable to increased online accessibility to case law. Fourth, domestic courts have a general tendency to cite to the jurisprudence of legal systems that are geographically proximal. Finally, in aggregate we find support for the proposition that there is an emerging global community of courts held together by an increasingly seamless web of foreign case law citation. However, that community is dominated by a clique of countries–Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom (chiefly, England and Wales), New Zealand and the United States–that exchange dialogue between themselves and attract the majority of inward citations from the rest of the community.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an outline of previous work applying network analysis to judgment corpora. In Section 3 we present the framework for our study and analyze the global properties of the cross-jurisdictional citation network. Section 4 utilizes the network of citations to explore the extent to which a judge’s decision to cite a particular foreign case is guided by how influential the case is; the degree to which is it well-grounded in established precedent and the country from which it emanates.

2 Related Work

There is a growing line of research that seeks to represent judgment corpora, and their underlying citation structures, as complex networks [9]. Several earlier studies that utilize citation network analysis on judgments have focused on American case law. These studies have aimed to measure the influence of US Supreme Court and Federal Courts of Appeals judges [10,11] and analyze citation patterns between state appellate courts [12–14]. Attention has been directed toward understanding the general internal network dynamics of US Supreme Court decisions [15,16], tracing the evolution of legal principle in that court’s body of jurisprudence [17], measuring the importance of its precedents [18] and evaluating how strategic interactions between Supreme Court justices during the court’s bargaining process affects citations to precedent in the court’s final opinion [19].

Network analysis of citations have also been applied to Canadian [20] and Australian [21] case law, in addition to judgments of international courts and tribunals, including the European Court of Human Rights [22], the Court of Justice of the European Union [23], the International Criminal Court [24,25], the Appellate Body of the World Trade Organization [26] and the International Court of Justice [27].

Other work focused on quantitatively analyzing the use of foreign authority by domestic courts is scarce. A comparative analysis of engagement with foreign case law in the decisions of the highest courts of the United States, Canada and Australia suggests that judges in Canada and Australia promote the use of foreign case law as persuasive authority, particularly in the context of criminal cases, using the case law of other countries both to defend arguments and to refute them, and to clarify a position through comparison and contrast with domestic case law [8]. A survey of US federal court case law citation practice between 1945 and 2005 revealed that citation of foreign decisions is a relatively rare phenomenon in the United States that is generally confined to cases where international issues are squarely presented by the facts [28]. In Australia, an analysis of decisions of the High Court of Australia between 2015 and 2016 found that court tended to cite foreign judicial decisions emanating from jurisdictions that reflect values common to the Australian legal system, particularly where the cited case considers statutory language that is similar to that which is in dispute [29]. Most recently, an analysis of United Kingdom Supreme Court decisions found that citations to foreign jurisprudence occurred in just under 30% of that court’s decisions [30].

The work outlined above focuses on citation activity that is specific to an individual court (e.g., the United States Supreme Court, the European Court of Human Rights etc.) or to an individual territorial jurisdiction (e.g., Australia, Canada, the United States etc). This paper provides a cross-jurisdictional perspective on judicial citation interactions between multiple countries and their respective senior courts.

3 The Common Law Citation Network: Global Properties

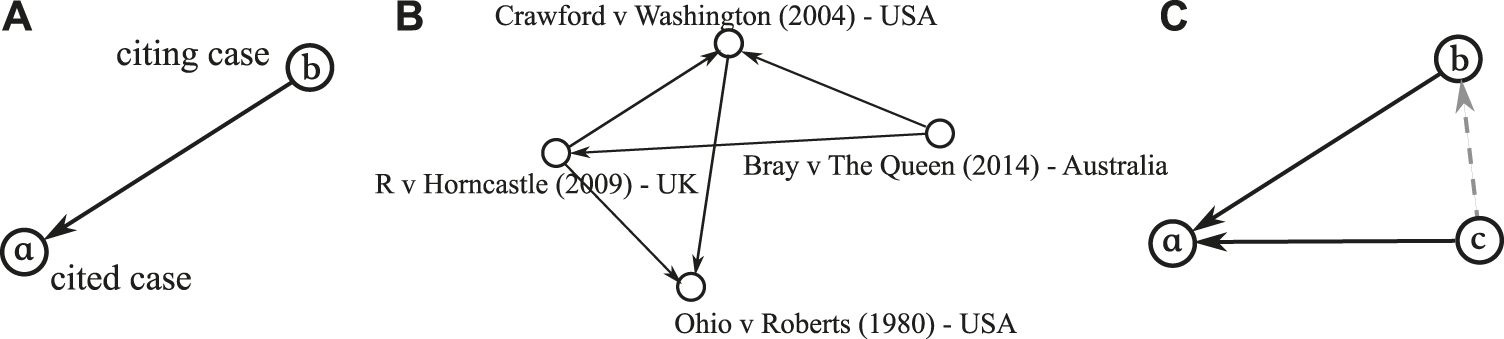

To demonstrate how citations to earlier cases in judicial decisions can be modeled as a network, consider the following example based on a small selection of cases concerning the ability of an accused person to challenge hearsay evidence admitted against them in criminal proceedings. In Crawford v Washington8 the United States Supreme Court held that the Confrontation Clause in the Sixth Amendment prohibited the introduction of testimonial hearsay as evidence at trial unless the declarant was unavailable to give evidence in person and the accused had the prior opportunity to cross-examine the declarant. In its reasoning the court cited, and overruled, an earlier decision of the United States Supreme Court addressing the Confrontation Clause–Ohio v Roberts9. The United States decisions in Crawford and Roberts were both subsequently considered, as persuasive authority, by the United Kingdom Supreme Court in R v Horncastle10. Finally, the United States decision in Crawford and the United Kingdom decision in Horncastle were considered by the Victoria Court of Appeal in Australia in Bray v The Queen11. The relationships between the cases in this example network are shown in Figure 1B.

FIGURE 1

The citation network. (A) Nodes a and b representing cases linked by a directed edge from citing to cited node. (B) The graph for four hearsay cases decided in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States with cross-jurisdictional citation edges. (C) Triads between three citation nodes. It is considered a Triangle if the dotted edge c-b is included in the graph.

Our corpus consists of 1,559,807 judgments covering a rich spread of civil and criminal matters given between 1717 and 2020 by the senior and appellate courts of twenty-six common law systems. In addition to setting out the court’s reasoning for its determination in a given case, the judgments cite principles settled in earlier cases emanating from their own respective domestic legal systems and, to a lesser extent, from cases decided by courts in foreign jurisdictions. These judgments contain citations to 853,287 unique judgments. Citations in the judgments were identified using a proprietary rules-based engine developed by vLex Justis that allows for ambiguous reporter series abbreviations and the accurate resolution of malformed references. Detected citations are reconciled to unique case entities using a database of parallel citations developed and maintained by vLex Justis.

As outlined in Section 1, a fundamental feature of common law systems is the principle that judges are bound by the earlier decisions of judges in superior courts. Notwithstanding that the legal systems of the countries represented in our corpus are not identical, they all broadly conform to a similar hierarchical court structure. Inferior or lower courts sit at the bottom of that hierarchy. In general, inferior courts are concerned with questions of fact and provide the venue within which the majority of legal disputes are resolved at a local level. For example, in the context of the English and Welsh legal system, the majority of civil disputes are heard in the county court (the lowest civil court) and most criminal matters are heard in the magistrates’ court (the lowest criminal court). In contrast, senior or higher courts, which are located higher up the court hierarchy, are generally concerned with questions of law and exercise supervisory and appellate jurisdiction over the courts below them in the hierarchy. All of the countries represented in our corpus have a “court of last resort” that sits at the apex of the court hierarchy. Apex courts in our corpus include the High Court of Australia, the United Kingdom Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court. The jurisdiction of apex courts, such as the United Kingdom Supreme Court, is generally reserved for cases of significant public importance and legal complexity. Accordingly, senior jurisdiction is conferred to courts lower down the hierarchical structure. For example, in England and Wales, the United Kingdom Supreme Court sits at apex of the court hierarchy. The Civil and Criminal Divisions of the Court of Appeal are subordinate to the Supreme Court, but are superior to the High Court; and the High Court is subordinate to the Court of Appeal, but is superior to the county court. Collectively, the United Kingdom Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal and the High Court are the senior or higher courts in the United Kingdom. Earlier work analyzing the use of foreign case law L’Heureux-Dube [1]; Lefler [8]; Tyrrell [30] indicates that the majority of cross-border interactions occur between courts situated at the top or near to the top of the relevant domestic judicial hierarchies. For this reason, we limit the scope of our study to the higher courts of the countries in our corpus.

This paper does not exhaustively cover all of the common law systems available in the vLex Justis collection; judgments of India, Kenya and Sri Lanka, for example, are not included in this study because data on inward and outward citations of cases in judgments emanating from those countries is currently unavailable. Moreover, for the same reason, our corpus does not include data on the number of South African judgments cited by other countries. However, we include South Africa in this study because the data does include foreign cases cited by South African courts. Additionally, our data for the United Kingdom chiefly consists of judgments of the courts of England and Wales, including decisions of the House of Lords and the Supreme Court that consider appeals originating in England and Wales. However, for convenience, we refer to the United Kingdom to describe this portion of the data. Finally, given its leading role in global affairs and the size of the jurisdiction generally, it would be reasonable to assume that the number of inward and outward citations for the United States would be larger than they appear in our data (6,008 outward citations and 7,910 inward citations). In common with the other countries in our data, we have selected courts that sit at the top of the United States court hierarchy. As discussed elsewhere in this paper, the low citation counts are consistent with earlier work which has found that foreign case law utilization is rare in the United States [28].

We construct the complete directed case-to-case network of domestic and cross-jurisdictional citations in which, as per Figure 1A, cases are represented as nodes and citations between them as edges. A directed edge extends from case b (the citing case) to case a (the cited case) if case a is referred to at least once in the judgment of case b. By construction, there are no cycles because a case is only capable of citing earlier decisions. The resulting network is a directed acyclic graph that evolves over time.

A majority of the complete network consists of relationships between cases where both the citing case and the cited case emanate from the same country (domestic citations), in additional to a smaller proportion of relationships where the citing case and the cited case emanate from different countries (foreign citations). Our analysis is principally concerned with relationships falling into the latter category. To construct the second network, the cross-jurisdictional network, we exclude all instances of domestic citation from the data (for example, where a United States case cites another United States case) so that the network only consists of cases that have interacted at least once with a case from a different country. A summary of the data in the cross-jurisdictional network is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Country | Citing cases | Cited cases | Year of earliest citation in XJ network | Year of latest citation in XJ network | Year of earliest citation in complete network | Year of latest citation in complete network | Superior courts included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla | 834 | 15 | 1967 | 2019 | 1842 | 2019 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 2,504 | 23 | 1959 | 2019 | 1808 | 2018 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Australia | 75,919 | 10,387 | 1903 | 2020 | 1,679 | 2020 | Federal Court, High Court, Court of Appeal (Victoria), Supreme Courts (northern territories, New South Wales, Victoria) |

| Bahamas | 11,686 | 43 | 1972 | 2019 | 1718 | 2019 | Supreme Court, Court of Appeal |

| Barbados | 7,616 | 326 | 1950 | 2019 | 1721 | 2017 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Belize | 3,802 | 111 | 1967 | 2019 | 1768 | 2019 | High Court, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court |

| Bermuda | 9,584 | 131 | 1957 | 2020 | 1772 | 2019 | High Court, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court |

| British Virgin Islands | 2,212 | 12 | 1967 | 2019 | 1828 | 2016 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Canada | 17,546 | 12,156 | 1938 | 2020 | 1722 | 2020 | Supreme Court of Canada, federal Court, federal Court of Appeal, Supreme Court (British Columbia), Court of Appeal (Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, nunavaut, Ontario, Yukon territory) |

| Cayman Islands | 1,920 | 57 | 1972 | 2020 | 1813 | 2019 | Court of Appeal |

| Grenada | 1,675 | 11 | 1962 | 2019 | 1777 | 2017 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Guyana | 7,263 | 684 | 1946 | 2017 | 1,687 | 2016 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Hong Kong | 1,712 | 0 | 2019 | 2020 | 1838 | 2020 | High Court, Court of Appeal, Court of Final Appeal |

| Ireland | 30,730 | 2,229 | 1876 | 2020 | 1,682 | 2020 | High Court, Court of Appeal, Court of Criminal Appeal, Supreme Court |

| Jamaica | 27,617 | 872 | 1905 | 2019 | 1,694 | 2019 | Court of Appeal, Supreme Court |

| Malaysia | 43,295 | 2,277 | 1932 | 2020 | 1,687 | 2019 | Supreme Court, High Court, federal Court, Court of Appeal |

| New Zealand | 22,579 | 3,884 | 1964 | 2020 | 1702 | 2020 | High Court, Court of Appeal, Supreme Court |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 1,562 | 1 | 1967 | 2019 | 1774 | 2019 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Saint Lucia | 2,109 | 16 | 1956 | 2019 | 1809 | 2017 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 2,136 | 4 | 1967 | 2020 | 1777 | 2018 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Singapore | 19,063 | 1,542 | 1967 | 2018 | 1725 | 2017 | Court of three judges, High Court |

| South Africa | 21,616 | 1 | 1910 | 2020 | 1763 | 2019 | Supreme Court of Appeal and other courtsa |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 24,641 | 1,319 | 1948 | 2019 | 1707 | 2019 | High Court, Court of Appeal |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | 570 | 0 | 1999 | 2018 | 1875 | 2016 | Supreme Court, Court of Appeal |

| United Kingdom | 10,928 | 313,111 | 1767 | 2020 | 1713 | 2020 | Supreme Court, house of lords, privy council, Court of Appeal (england and wales), Court of Appeal (northern Ireland), High Court (england and wales) |

| United States | 6,008 | 7,910 | 1968 | 2020 | 1,697 | 2019 | United States Supreme Court, State Supreme Courts, United States Courts of Appeals |

Composition of the cross-jurisdictional (XJ) network showing the courts included in our analysis. Citing Cases is the number of unique cases that have at least one outward edge. For example, cases from the United Kingdom cited to a total of 10,928 foreign cases. Cited Cases is the number of unique cases with at least one inward edge. For example, 313,111 cases from the United Kingdom were cited by other countries in the data. The year of the earliest and latest citations are provided for both networks. For the United Kingdom, the year of the earliest case with either an inward or outward edge in the cross-jurisdictional network is 1767 (1713 in the complete network) and the latest is 2020 (also 2020 in the complete network).

Appellate Division, Cape Town - Bloemfontein, Appellate Division, Pietermaritzburg - Cape Town, Appellate Division, Pretoria, Appellate Division, Pretoria - Bloemfontein, Appellate Division, Privy Council, Bhisho High Court, Bophuthatswana Appellate Division, Bophuthatswana High Court, Bophuthatswana Supreme Court, Cape Provincial Division, Ciskei Appellate Division, Ciskei High Court, Ciskei Supreme Court, Constitutional Court, Constitutional Court, Zimbabwe, Durban and Coast Local Division, East London Circuit Local Division, Eastern Cape Division, Eastern Districts Local Division, Free State Division, Bloemfontein, Free State Division, Bloemnfontein, Gauteng Division, Pretoria, Gauteng Local Division, Johannesburg, Griqualand-West Local Division, Hooggeregshof van Venda, KwaZulu-Natal Division, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal Division, Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal High Court, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal High Court, Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal Local Division, Durban, Lesotho High Court, Maseru, Limpopo Division, Polokwane, Mpumalanga Division (Main Seat), Mpumalanga Division, Nelspruit, Natal Provincial Division, North Gauteng High Court, Pretoria, North West Division, Mahikeng, North West High Court, Mafikeng, North West High Court, Mahikeng, Northern Cape Division, Orange Free State Provincial Division, Privy Council, Rhodesia and Nyasaland Court of Appeal, South Eastern Cape Division, South Eastern Cape Local Division, South Gauteng High Court, Johannesburg, Southern African Development Community Tribunal, Supreme Court of Appeal, Supreme Court of Namibia, Transkei Appellate Division, Transkei Division, Transkei High Court, Transkei Supreme Court, Transvaal Provincial Division, Venda High Court, Venda Supreme Court, Western Cape Division, Cape Town, Western Cape High Court, Cape Town, Witwatersrand Local Division.

3.1 Global Properties of the Networks

We begin by analyzing the global properties of the complete and cross-jurisdictional networks. A summary of the global properties of both networks is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| Complete network | Cross-jurisdiction network | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nodes | 1,711,626 | 169,131 | 9.88 |

| Edges | 12,656,156 | 355,598 | 2.81 |

| Average clustering coefficient | 0.019 | 0.006 | |

| Density | 4.32 | 1.24 | |

| Transitivity | 0.06 | 0.003 |

Properties of the complete and cross-jurisdictional networks.

The first feature of interest emerges from a comparison of the size of both networks. As mentioned above, we construct the cross-jurisdictional network of citation interactions between cases emanating from different countries by excluding all cases that do not have at least one interaction (either as a citing or a cited case) with a case emanating from a different country. We retain 9.88 percent of the nodes in the complete network and 2.81 percent of the edges. This yields the insight that a reasonably large number of the cases in our corpus have engaged, whether actively as a citing case or passively as a cited case, in the practice of citation of foreign case law.

We also compute the density, average clustering coefficient and transitivity of both networks. The average clustering coefficient is a global measure of the abundance of triangles present in the network. In the context of a case law citation network, a triangle exists where case b cites case a and both cases a and b are cited by case c (see Figure 1C). Given that instances of domestic citation (citations between two cases that emanate from the same country) have been removed from the cross-jurisdictional network, for both networks we compute the clustering coefficient for a case, ν, by dividing the number of edges between ν’s neighbours by the number of edges between ν’s neighbors that do not emanate from the same country. In other words, if node j has nearest neighbors with connections between nodes in different jurisdictions, the local clustering coefficient isand is the average clustering coefficient of the network

Transitivity measures the fraction of possible triangles by identifying the number of triads in the network. A triad of nodes in our networks exists where case a is cited by cases b and c, but no edge exists between cases b and c.

In common with other real-world complex networks, such as social networks [31]; ecological systems [32]; and patent citation networks [33], the complete and cross-jurisdictional networks present low density (4.32 and 1.24, respectively). In the complete network, the coefficients of average clustering and transitivity are four orders of magnitude greater than the global density. In the cross-jurisdictional network, the average clustering coefficient and transitivity are two orders of magnitude greater than that network’s density. Both networks present global properties that are similar to those found in a similar study that focused on the citation network in a corpus of judgments from the International Criminal Court [25].

The complete network presents clustering behavior that is an order of magnitude higher than its cross-jurisdictional counterpart (see Table 2). This is expected, because the cross-jurisdictional network was constructed by pruning all nodes from the complete network that did not have at least one interaction (as the citing or cited case) with a foreign case. The comparatively low degree of clustering in the cross-jurisdictional network provides an indication that instances in which three or more cases become linked through citation are rare. We analyze this further in Section 3.2.

3.2 Degree Distributions

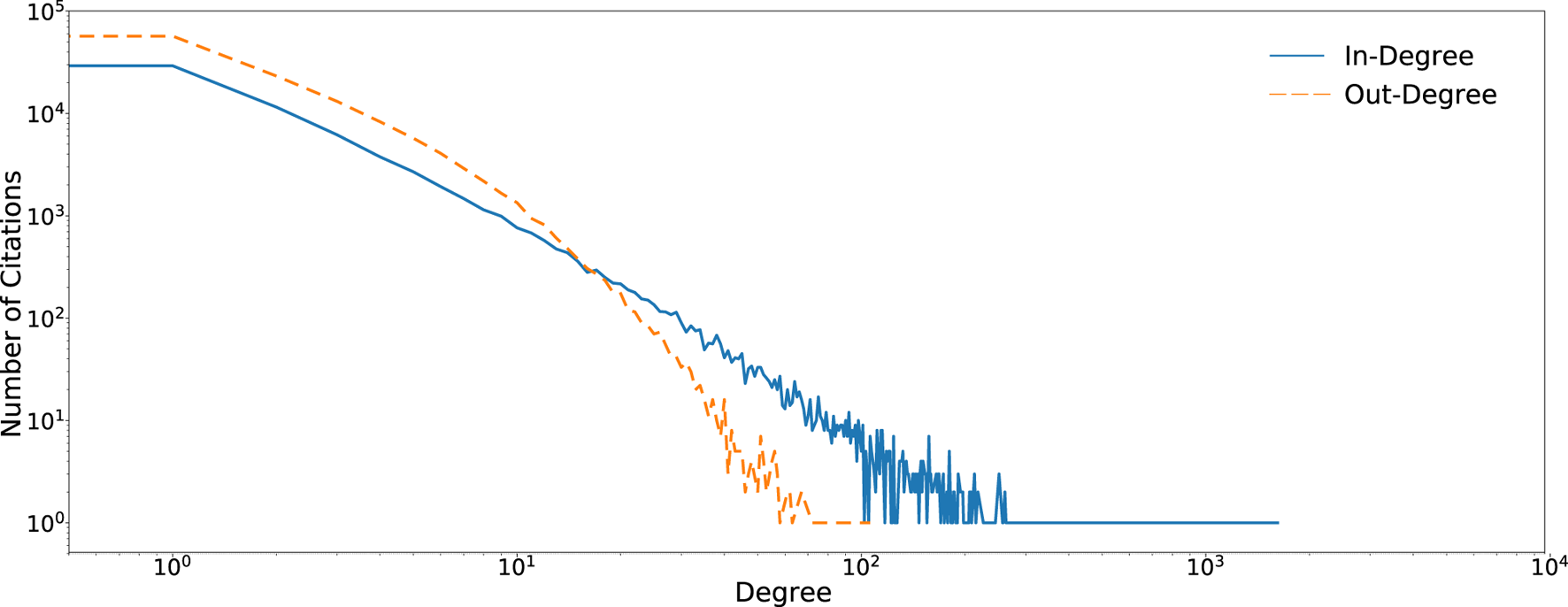

The degree distribution of a network is a fundamental quantity measured in most analyses of complex networks. In this section we analyze the distribution of inward citations (citations to a case) and outward citations (citations from a case) in the cross-jurisdictional network. The inward and outward degree distributions examined in earlier studies of case law citation networks constructed from the decisions of the US Supreme Court, European Court of Human Rights and the International Criminal Court have each exhibited two common characteristics. First, their inward and outward degree distributions are heterogeneous. Second, both distributions appear to follow a pattern whereby most decisions in the network are cited by relatively few cases, whereas a small number of decisions are cited by many cases. The same pattern applies to the inverse scenario, where most decisions in the network cite relatively few other cases, whereas a minority of decisions cite many cases. Similar patterns have been widely observed in the degree distributions of other large networks, including scientific paper citation networks [34], patent citation networks [35, 36], the structure of the World-Wide Web [37] and social networks [38]. It has been argued that these distributions are the consequence of a process of “preferential attachment” [39, 40] which would indicate, in the context of a judicial citation network, that the more a case has been cited by past cases, the greater the likelihood that it will be cited by future cases. The inward and outward degree distributions in our cross-jurisdictional network, as can be seen in the log-log plots in Figure 2, share these properties.

FIGURE 2

Log-log distributions of inward and outward citations in the cross-jurisdictional network.

There is evidence of the process of preferential attachment in the cross-jurisdictional network. We observe that 611 cases ranked in the 99th and 100th percentiles by inward citation count constitute a quarter of the total inward citations in the entire cross-jurisdictional network. Examining this small population of 611 cases with high indegrees, which we will refer to as super authorities [41, 42], provides initial insights into the dominance of case law emanating from specific countries in the cross-jurisdictional network. We find that the majority (80.4%) of citations in the cross-jurisdictional network were to United Kingdom super authorities, while the second largest group of most cited cases were Canadian super authorities, with 17.3% of the share of inward citations. The dominance of super authorities from the United Kingdom (chiefly, England and Wales) and Canada persists when we limit the pool of cited cases to those decided in or after 2000. However, the proportion of United Kingdom super authorities declines to 67.2%, while the proportion of Canadian cases in the top two percentiles of inward citation count rises to 23.2%.

To examine the extent to which the cases in this group of super authorities possess landmark12 qualities, we calculated the proportion of the top ranking 100 cases emanating from courts in the United Kingdom (which are mainly decisions from the English and Welsh jurisdiction) by indegree that had been reported in England and Wales’ leading series of law reports, The Law Reports, published by the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales since 1865. For a case to be selected for inclusion in The Law Reports it must exhibit, in the view of that series’ editors, the potential to have longstanding significance as a precedent 13. In general, cases selected for inclusion in The Law Reports are published in that series within a year to eighteen months from the date of judgment.

We found that 86 of the top ranking 100 United Kingdom cases by inward citations had been reported in that series of law reports and that 66 of these cases were decisions of the United Kingdom

apexcourts: the Supreme Court, the House of Lords and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. This suggests that there is a correlation between the indegree of a case and the status of that case as a landmark authority. This indication is supported by an inspection of the top three ranking United Kingdom cases, all of which are generally regarded as seminal decisions:

• American Cyanamid Company v Ethicon Ltd., 14 the leading authority on applications for interim relief. 1,477 inward citations.

• Associated Provincial Picture Houses Ltd. v Wednesbury Corporation, 15 a leading case in the sphere of judicial review that established the test of unreasonableness in public body decision making. 860 inward citations.

• Donoghue v Stevenson, 16 established the foundations of the tort of negligence. 719 inward citations.

While using The Law Reports as a benchmark provides a useful guide for ascertaining the correspondence between indegree and the status of a case as a landmark authority, there are limitations to this approach. Inclusion of a case in The Law Reports amounts to a prediction on the part of that series’ editors as to the likelihood that the case in question bears the marker of a landmark authority. Publication in that series of law reports therefore has the potential to enhance the visibility and the perceived impact of a given reported case to users of case law, thereby increasing the likelihood that it will be discovered and cited in future cases when compared to a case that was not reported in that series. One way to control for this effect, which we leave for future work, may be to examine the rate of citation to a case for a period prior to (generally, a year to eighteen months) and following its publication in The Law Reports. Moreover, it has been recognized that citation counts are biased by the age of the cited unit. For example, in the context of academic paper citation networks, the number of citations received by a paper depends on the age of the paper [43]. Older papers have more time to acquire citations than more recent papers–an advantage that is enhanced by the phenomenon of preferential attachment [44, 45]. Both the complete and cross-jurisdictional networks are subject to this bias.

3.3 Average Clustering as a Function of Degree

In their analysis of the citation network constructed from a corpus of International Criminal Court decisions Tarissan and Nollez-Goldbach [25] observed a pattern under which the local clustering coefficient of a decision was inversely proportional to its indegree: decisions with high indegree presented low clustering, whereas decisions with low indegree presented higher local clustering. The authors of that study explain this pattern by noting that small indegree cases in their network tended to deal with esoteric issues pertaining to the court’s procedure that raised specific and technical points of law, while larger degree cases addressed substantive issues of broader application. A similar pattern has been observed in other growing directed networks, such as scientific paper author collaboration networks [46].

Translating this trend into the context of our cross-jurisdictional network, it would suggest that large degree cases establish general principles that are applicable to a wide range of factually disparate disputes: case a establishes principles or rules of general application that are relevant to the issues to be determined in cases b and c, but the factual and legal matrices of cases b and c do not overlap sufficiently for either of those cases to cite the other. The inverse scenario in which low degree cases present higher clustering would suggest that low degree cases have a tendency to address specific factual and legal issues that are relevant to small cliques of cases entering the network.

We compute the average local clustering coefficient (using the approach outlined in Section 3.1) as a function of indegree to explore whether a similar relationship exists in our networks and compare our results to random networks. For both networks, we generate a random network using the degree distribution of the respective real network as the configuration model, removing all self-looping and parallel edges from the generated network. We then randomly assign a country attribute to each node in the generated random network, following the distribution of countries in the respective real network (i.e., the proportion of Canadian nodes in the random cross-jurisdictional network is equal to the proportion of Canadian nodes in the real cross-jurisdictional network). Finally, all edges between nodes from the same country were removed from the random version of the cross-jurisdictional network. Our results are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3

Local average clustering coefficient of cases as a function of indegree. (A) The complete network (B) The cross-jurisdiction network. Cases with high degrees present lower clustering coefficients. The complete and cross-jurisdictional networks are shown in blue, their randomized counterparts are shown in orange.

There is some evidence of a correlation between indegree and local clustering in the cross-jurisdictional network (Figure 3B), although it is weak. In the random cross-jurisdictional network, shown in orange, the clustering coefficient of cases with low indegree is small before increasing at higher indegrees. There is deviation between both networks at low degree, with the cross-jurisdictional network presenting higher clustering for cases with low inward citations. However, the deviation between the real and the random network is less distinct at high degree. High degree nodes in both networks present low clustering, although the coefficient is larger in the cross-jurisdictional network than in the random cross-jurisdictional. As can be seen, the majority of the cases in the cross-jurisdictional network have high degree. It is therefore possible, even when compared with the random network, that the presence of higher clustering at low degree in the cross-jurisdiction is the product of chance rather than the phenomenon observed by Tarissan and Nollez-Goldbach [25].

The opposite pattern is observed in the complete network (Figure 3A), which demonstrates a trend of increased clustering for cases with higher inward citations compared to cases with fewer citations. This trend is also reflected in the random complete network. However, clustering at high indegree in the complete network exhibits far more variability than that observed in the random complete network. This variability may indicate the presence of cases in the complete network that act as frequently cited hubs of jurisprudence on legal issues that are common or prominent across a range of countries in our network. Deeper analysis, which we reserve for future work, could be directed to confirm and explore the presence of these hub cases and the role they may play in diffusing key common law concepts across nations.

3.4 Evolution of the Cross-Jurisdictional Network Over Time

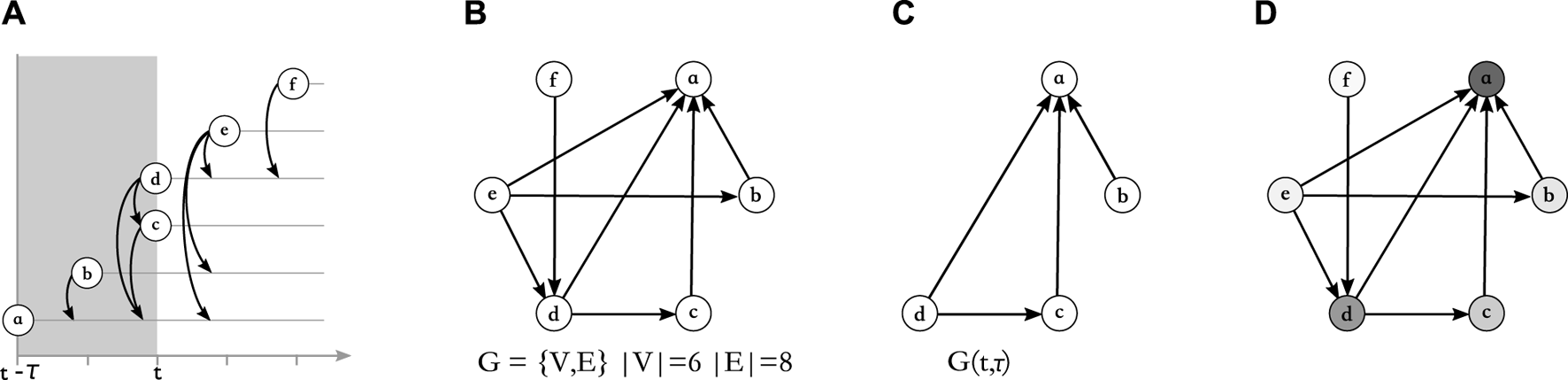

Our focus now turns to exploring how the cross-jurisdictional network has evolved over time. To enable this we follow the temporal window approach of Steer et al. [47]. This approach allows us to view the exact state of the networks at any point throughout its lifetime and move through this history at different temporal levels of granularity. By filtering out older entities shorter term patterns may be extracted which would otherwise be obscured by the full data aggregate.

The temporal window approach is illustrated in Figure 4. In Figure 4A the evolution of a network is plotted over time, showing new vertices joining the network and which existing nodes they are connected to. This can be envisioned within our cross-jurisdictional network context where new judgments are published, citing previously established judgments and, therefore, generating edges. Aggregating all of these vertices and edges together will create the latest version of the graph G, seen in the middle of the figure, which is what typical graph analysis will be performed on. Lastly, in Figure 4C, we can see a windowed view of the graph . This consists of the graph as it would have existed at time t and with a set window size of τ.

FIGURE 4

Temporal graph. (A) Windowing procedure to construct the graph (B) Complete graph G with 6 nodes and 8 edges (C) Sub-graph (D) Authority score. Example where the shade of each node represents its Authority score. Node a has high authority.

3.4.1 Growth of the Cross-Jurisdictional Network

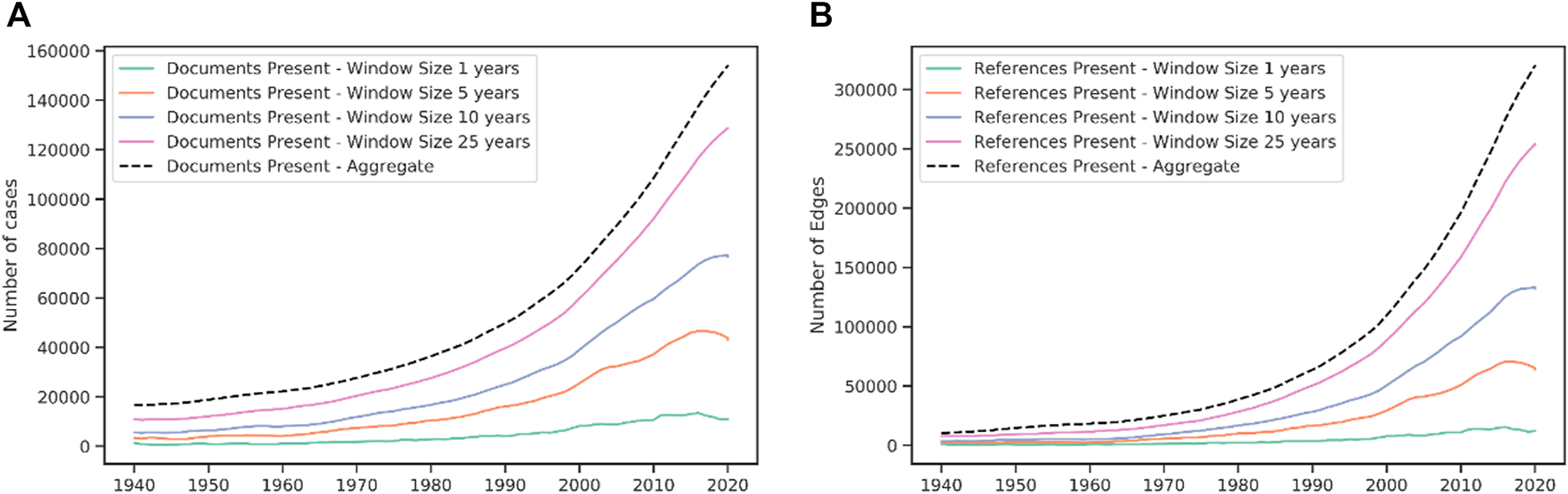

We begin our temporal analysis of the cross-jurisdictional network by investigating the growth of the network, based on the number of nodes and edges present, between 1940 and 2020. This temporal period is chosen because as Table 1 shows, the majority of citation interactions in the corpus selected for this study begin in the mid-twentieth century. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5

Evolution of the cross-jurisdictional network. (A) Nodes and (B) edges present over time and four window widths, .

The growth of the network was modest in the fifty years between 1940 and 1990, with an approximate increase of 28,000 cases and 60,000 edges present in the network over that period. The size of the network accelerates from 1990 onward, with a three-fold increase from 60,000 cases in 1990 to 181,618 cases in 2020. The increase in edges in the network is even more striking, rising from approximately 70,000 edges in 1990 to 384,336 edges in 2020. The growth in cases entering the network from 1990 may be attributable to the rise in the use of digital systems to author, store and disseminate case law [1, 48, 49] and the fact that as time passes the stock of precedent increases–there are more earlier cases available to be cited.

3.4.2 Average Case Degree

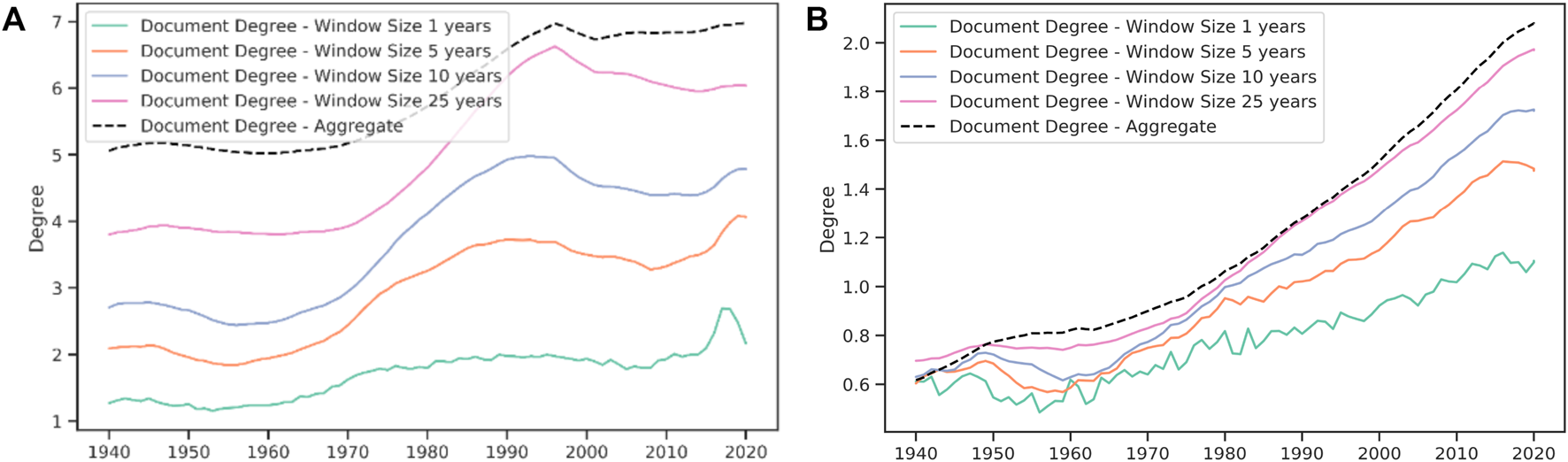

The increase in the number edges in the network raises the question as to whether judges have increased the number of cases cited in their judgments. To explore this, we analyzed the mean degree of the cases in the complete network and the cross-jurisdictional network between 1940 and 2020. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6

Distribution of case average degree. (A) The complete network (B) The cross-jurisdiction network. Window widths..

Both networks present an increase in mean degree over time. The mean degree of cases in the complete network, shown in Figure 6A rises from five in 1940 to 7 in 2020, with a noticeable increase occurring between 1970 and 2000, at which point the mean degree plateaus. The mean degree of cases in the cross-jurisdictional network, shown in Figure 6B are lower, rising from a mean of 0.6 in 1940 to 2 in 2020. This indicates that judges have progressively increased the amount of case law cited in their judgments over time, both in the complete network, which includes domestic citations, and in the cross-jurisdictional network.

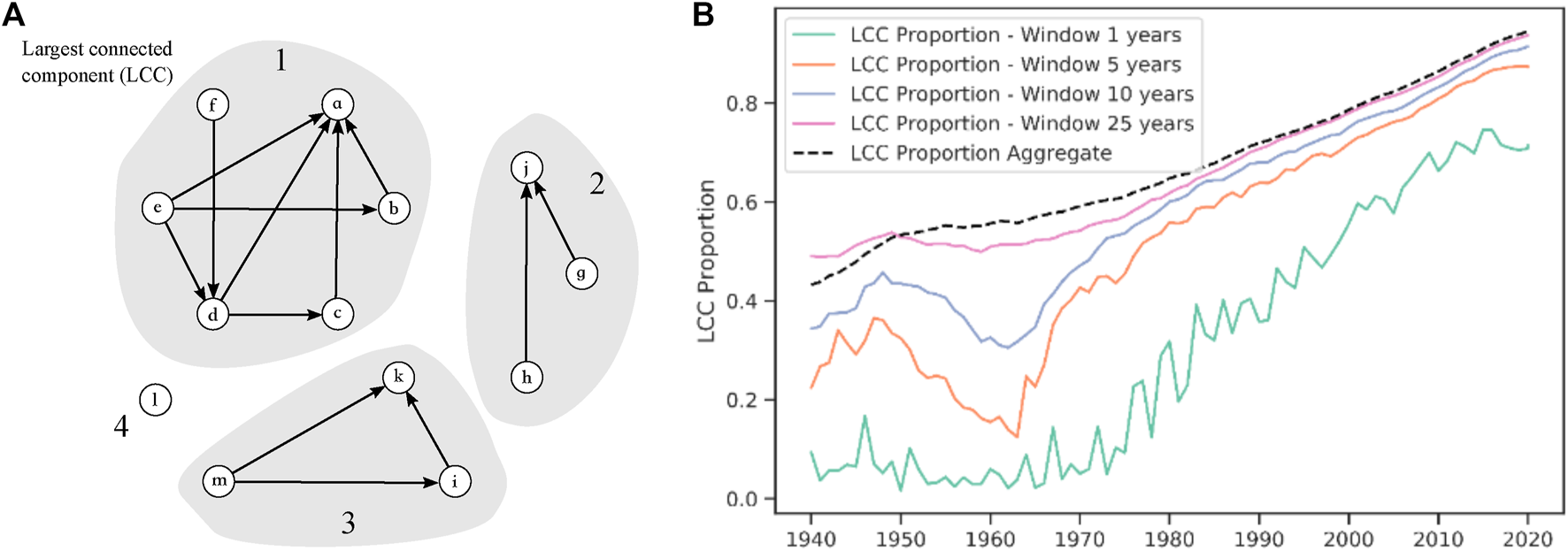

Our conclusion that judges have increased the number of cases they cite in their judgments over time leads to the possibility that the network of foreign citations has grown progressively more connected over the same period. This is supported by a temporal analysis of the growth of the largest connected component in the cross-jurisdictional network, the results of which are shown in Figure 7. In the context of a case law citation network, a component is a set of cases for which each pair of cases are linked by at least one path through the network (see Figure 7A).

FIGURE 7

Connected components. (A) Connected components on for a graph at time t illustrating the largest connected component (LCC). (B) Temporal connected components with five window widths showing the change in the proportion of the LLC in the cross-jurisdictional network.

The trend presented by our analysis of the growth of the largest connected component in the cross-jurisdiction network in Figure 7B shows that the size of that component has more than doubled from where it stood in 1940 at approximately 45% of the network to approximately 95% of the network in 2020. The presence of a single giant component in the network is consistent with the findings of earlier analyses of case law networks [18, 22]. This may be an indication that the body of foreign persuasive authority cited by the countries in the cross-jurisdictional network has achieved a some degree of integration over the passage of time. When citing foreign cases, domestic judges are sampling from, and contributing to, a progressively more seamless web of case law [16] as opposed to fragmented isolated clusters of authority. However, we also observe in Figure 7B that the size of the largest component in the cross-jurisdictional network temporarily decreased between 1955 and 1965 when τ is set to a window size of 5 and 10 years. This reduction in the size of largest component is likely due to the fact that the majority of non-United Kingdom judgments in our corpus entered the network during this period, which led to the temporary creation of smaller components that were subsequently assimilated into the largest component once they were cited by later cases.

4 A Global Community of Courts

4.1 Overview of Foreign Citations by Country

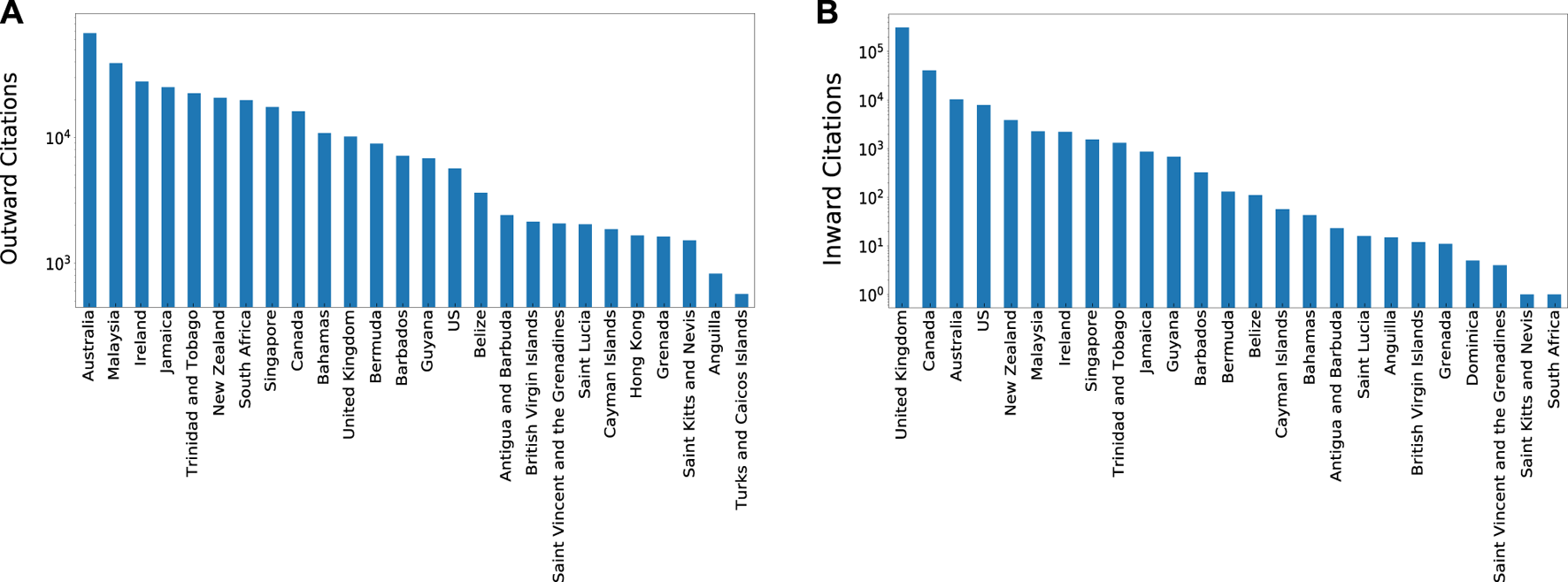

In the last section we presented our analysis of the fundamental global properties of the cross-jurisdictional network, along with an investigation of how the network has evolved over time. Our focus in this section turns to address the extent to which the cross-jurisdictional network reveals evidence of the emergence of a global community of courts formed by the cross-border flow of persuasive authority. The legal scholarship in this area presents a mixed picture in which the extent to which specific domestic legal systems are willing to engage with foreign case law varies considerably. Lefler’s [8] analysis of the judgments of the US Supreme Court, the Canadian Supreme Court and the High Court of Australia found that judges in Australia and Canada promote the use of foreign case law, particularly in criminal cases. The United Kingdom Supreme Court also makes regular reference to jurisprudence of other countries [30]. In contrast, earlier work indicates that American judges make relatively little use of foreign case law [8, 28]. Figure 8 show the log-scale quantities of foreign cases cited by and citing to each country in the network. Three points of interest emerge. The first is the dominance of cases emanating from the United Kingdom as the most cited legal system in the network. This is likely due to historical factors which are discussed further in Section 4.2. The second concerns Australia, which stands out as the most prolific user, by volume, of foreign authority–this trend is consistent Lefler’s [8] findings. The third relates to the United States. Notwithstanding that the use of foreign case law by United States courts has proven to be a contentious issue in the discourse of American legal scholars [42, 50], our data suggests that in contrast to comparable jurisdictions–such as the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia–the instances of United States engagement with foreign case law are rare. This is consistent with earlier work which found that American courts make scarce use of foreign case law [28]. Despite the fact that United States judgments appear to be relatively isolated from the influence of foreign jurisprudence, they form the fourth most consulted body of jurisprudence in the cross-jurisdictional network, after the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia.

FIGURE 8

Citation distributions in the cross-jurisdictional network. (A) Outward citations for each country (B) Inward citations per country. Australia is shown to be the most prolific user of foreign case law by outward citations. Judgments of courts in the United Kingdom, chiefly courts of England and Wales, are the most cited source of case law.

4.2 Considerations Relevant to the Citation of Foreign Case Law

Our analysis shows that although the courts of all countries in our corpus engage in the citation of foreign case law, the extent to which they do so varies. In all cases the volume of citations to foreign case law are dwarfed by the volume of citations to domestic law. The variability in interactions with foreign case law across the countries in the cross-jurisdictional network suggests the existence of deeper considerations on the part of judges when reaching beyond their domestic law to persuasive judgments given by the courts of other countries.

We begin from the basic legal and constitutional imperative that in order to maintain their institutional and decision legitimacy, national courts will generally seek to resolve the legal issues before them in accordance with the content of their own binding domestic law. From this imperative, we assume that where the resolution of legal issues presented by a case appears to require, and the doctrine of precedent permits, the use of authority by which the court is not bound (persuasive authority), the court will prefer domestic persuasive authority over foreign authority. Accordingly, we proceed on the basis that national courts will generally refer to foreign case in limited circumstances as a matter of last resort where 1) the content of domestic law (binding or otherwise) is inconclusive as to the issues presented; 2) the content of domestic law is conclusive, but leads to an “unjust” 17 outcome and the court has the latitude to depart from established principle; or 3) the issues of the case squarely present an international dimension [28].

In this section, we test three assumptions to explore the extent to which the selection of foreign case law is guided by the citing court’s perception of how influential and well-reasoned a foreign case is and the country from which it emanates.

Assumption 1: “Importance” of foreign cases: Our first assumption relates to the perceived “importance” of foreign cases. On the most straightforward view, an “important” case is a case that has subsequently been cited by many important later cases. In view of the evidence that citation of foreign case law is a minority occurrence that arguably deviates from the strict goal of settling domestic legal questions in accordance with domestic law, we assume it is more likely than not that courts will have historically tended to confine themselves to the citation of foreign cases that exhibit high importance and influence in the jurisdictions from which they emanate. However, we assume that the emphasis courts place on the perceived influence of a foreign case as a prerequisite for citation will have declined over time as the practice of foreign citation has grown more commonplace.We use the authority score computed by the hyperlink-induced topic search algorithm (HITS) [51] as a proxy for the importance of a case: important cases are those with high authority scores and less important cases are those with low authority scores. We compute HITS over successive temporal partitions of the complete network to analyze how the authority scores of cases cited in the cross-jurisdictional network between 1940 and 2020 change over time. A reduction in the mean authority score of cases cited over time may provide an indication that judges have grown less concerned about limiting themselves to citing foreign cases that are regarded as having particular importance or weight of authority.

Assumption 2: “Grounding” of foreign cases: Our second assumption examines the extent to which cited foreign cases are “well-grounded” in their own domestic jurisprudence. On the most straightforward view, a “well-grounded” case is a case that it itself cited many earlier important cases. In common with Assumption 1, we assume that judges will have historically preferred to cite foreign cases that were well-grounded in their own domestic case law when they were decided. However, we assume that as the practice of foreign citation has grown more commonplace over time, the emphasis a judge may place on how well-grounded a case is will have reduced.We use the hub score computed by HITS as a proxy for how well-grounded a case is: well-grounded cases are those with high hub scores and less well-grounded are those with low hub scores. We compute HITS over successive temporal partitions of the network to analyze how the hub scores of cases cited in the cross-jurisdictional network between 1940 and 2020 change over time. A reduction in the mean hub score of cases cited over time may provide an indication that judges have grown less concerned about limiting themselves to citing foreign cases that are regarded as having been well-grounded in their own domestic law.

Assumption 3: Geographic proximity: Homophily, the principle that similarity breeds connection, has been found to influence a range of network settings, including paper citation networks [52] and social networks [53]. A recent study examining an Australian case law citation network observed that judges in that country generally favoured the jurisprudence of countries that reflect their social values and legal traditions [29]. There are any number of points of similarity between national legal systems, including socioeconomic factors, language, style of constitution and government. A further point of similarity, which we explore, is geographic proximity. Our third assumption is that judges will tend to favour the citation of foreign case law that emanates from countries that are geographically proximal. We use the geographic distance between the countries in our data as a proxy for similarity, where countries separated by low distance are assumed to be more similar than countries separated by larger distance.

4.2.1 The Importance and Grounding of Cited Foreign Cases

In their analysis of over 30,000 majority opinions of the United States Supreme Court, Fowler and Jeon [17] explore the ways in which the citation network could be harnessed to identify cases that are the most important or influential for establishing precedent. At the most basic level, as we have shown in our analysis of the 100 most frequently cited United Kingdom cases in the cross-jurisdictional network, it is possible to rely on degree centrality–a classic and intuitive measure of importance [54]. However, Fowler and Jeon’s study argues that degree centrality fails to fully utilize the information in the case law citation network because all inward citations are treated equally and that, when estimating the importance of a case, we should ideally be able to account for the cases that those cases themselves cite. This is made clearer with an example. Suppose case a is cited by a case of considerable importance, case x, and that case b is cited by a case of low importance, case y. This would indicate that case a is more important than case b, because case x is more important than case y.

An alternative strategy to the calculation of importance considered by that paper is eigenvector centrality, which computes the importance of nodes in a network based on the centrality of its neighboring nodes [55]. Eigenvector centrality was also discounted by Fowler and Jeon as an appropriate measure of importance for case law because that approach only treats nodes associated by an inward edge as neighbors for the purposes of the calculation. Fowler and Jeon regarded this as problematic because the importance of a case is simultaneously dependent on the importance of the cases citing it and the importance of the cases that it itself cites. For example, if case a is cited by case x, which cited many important cases, and case b is cited by case y, which mainly cited cases of low importance, then case a may be said to be more important than case b, because case x is well-grounded in important cases and case y is not.

The approach adopted by Fowler and Jeon to assess importance, which we follow in this paper, is the hyperlink-induced topic search algorithm (HITS) [51]. HITS uses two related but distinct scores of importance: the authority score and the hub score. In the context of a case law citation network, an authority is a case that is extensively cited by other cases in the network and a hub is a case that itself cites many other cases in the network. The relationship between authorities and hubs is mutually reinforcing–a good authority is generally a case that cites many good hubs; a good hub is a case that cites many good authorities. The authority score for a given case depends on 1) the number of cases it has been cited by; and 2) the hub scores of the cases it cites. This is illustrated in Figure 4D. Meanwhile, the hub score for a given case depends on 1) the number of cases it cites; and 2) the authority scores of the cases it cites 18.

We follow Fowler and Jeon [17] and use the authority score as a proxy for the importance of cases in the network to test Assumption 1, which assumes that the emphasis courts place on the perceived importance of a foreign case when considering whether to cite it will have been historically greater than it is in present times. The framework underlying Assumption 1 draws on two strands. First, the evidence in the literature and in the cases indicating the phenomenon of “cross-pollination” of judicial wisdom [1] suggests that judges are beginning to cast a wider net when it comes to the citation of foreign case law. There is an increase in cases cited per judgment over time in the cross-jurisdictional network in Figure 6B. The motivations driving wider citation of foreign jurisprudence, particularly in cases involving human rights, appear to stem from the recognition among an increasing community of judges that they are fellow professionals engaged in a common endeavor that transcends national borders [2] and improved accessibility of foreign case law online [1, 48, 49]. We therefore assume that the more widely judges are prepared to cite foreign authority, the less emphasis they will place on the “importance” of those authorities.

The second strand we draw on is the “strategic legitimation” model explored by Lupu and Voeten (2011) in their analysis of the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) use of its own body of jurisprudence. In that study Lupu and Voeten found that the selection of authority by ECtHR judges is guided by a strategic concern to persuade the domestic parties, particularly national governments, to comply with the court’s decisions by demonstrating impartial and careful decision-making [56]. Strategic legitimation was analyzed through the prism of the extent to which the ECtHR grounds its decisions in its own precedent, using the hub score calculated by HITS as the proxy for how “well-grounded” a given decision is in the court’s body of case law. The overarching hypothesis running through that analysis, which the authors confirmed, was that the ECtHR seeks to promote its institutional legitimacy by taking care to ground its decisions, particularly those bearing on controversial issues, in a thorough survey of its own case law.

Returning to our core assumption that domestic courts are subject to the legal and constitutional imperative to decide the cases before them in accordance with their own domestic law, the model of strategic legitimation operates as a counterbalancing check on the freedom of judges to sample and incorporate foreign jurisprudence in their judgments. In the context of this cross-jurisdictional analysis, therefore, there is a tension between the advantages of participation in cross-border judicial dialogue and the countervailing concern not to undermine institutional and decisional legitimacy by over liberally citing foreign case law.

To examine how the emphasis placed by judges on the perceived importance of foreign cases changes over time, we compute the authority and hub scores for all of the cases in the complete network across nine temporal partitions. We use the complete network for this computation because the importance of a case is a product of all of its citation activity, including citations to and from other cases emanating from the same country. The first partition contains all cases and their relationships between 1767 (the year of the oldest case in the network) and 1940; the second partition from 1767 to 1950; and so on, where the terminal year is incremented by ten years in each partition until it reaches 2020, at which point authority scores are computed for all of the cases in the complete network. This temporal partition approach was deployed by Fowler and Jeon [17] in order to analyze the rise and fall of a case’s authority score over time and allows us to overcome the fact that authority and hub scores would be frozen in a static network. To enable us to compare the evolution of the authority scores with a null network for each partition of the complete network, we generate a random equivalent using the degree distributions from the corresponding partition of the complete network and compute HITS on that random partition.

Given that the majority of the cases in the cross-jurisdictional network date from the mid-twentieth century, we start our analysis of the authority scores from 1940 stepping forward in time toward 2020 in ten year windows. For the first window, we induce the sub-graph of all cases cited between 1940 and 1950 from the cross-jurisdictional network and calculate the mean of the authority scores for that set of cases from the first partition of the complete network (1767–1950). For the next step, we slide the window forward in time to 1950 to 1960 and repeat the procedure against the second partition (1767–1960) of the authority score computed in the complete network, and so on. We repeat this procedure on the complete network to enable a comparison between purely cross-jurisdictional citation interactions one the one hand, and a complete representation of all citation activity, including domestic citation activity, on the other. We replicate this procedure on the random networks.

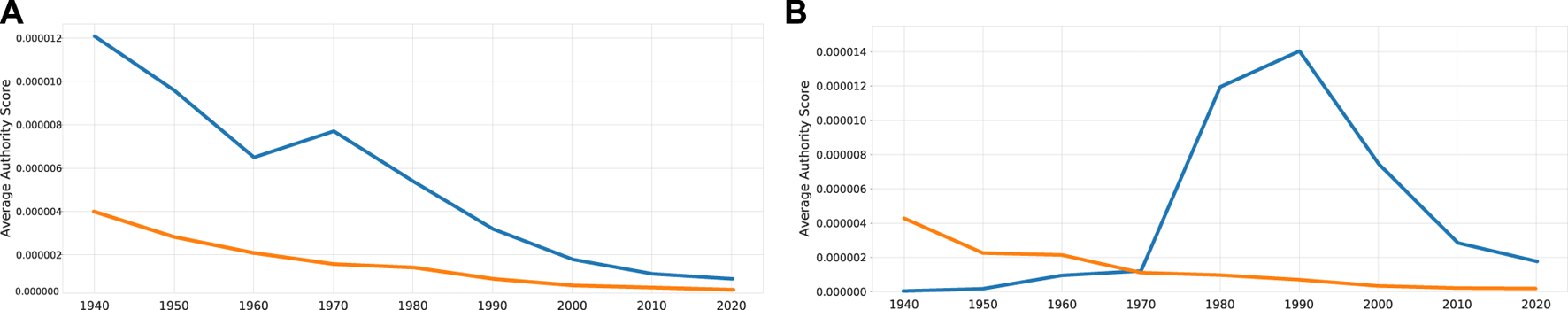

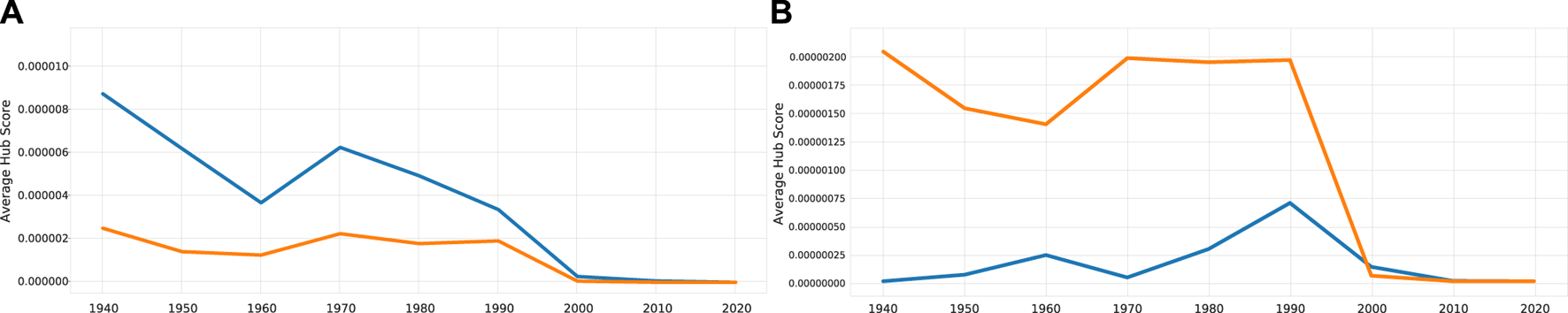

The evolution of authority scores of cases cited in the complete and cross-jurisdictional networks between 1940 and 2020, along with the authority scores computed in the random networks, are shown in Figures 9A,B, respectively.

FIGURE 9

Authority scores of (A) The complete network and (B) the cross-jurisdictional network between 1940 and 2020. For the real networks the authority scores are shown in blue, for the random networks the scores are shown in orange.

Our temporal analysis of authority scores in the complete network (Figure 9A), shows that the authority scores of cases cited steadily decreases over time. The same trend can also be observed in the evolution of the authority scores in the randomized version of the complete network, shown in orange, however the average score in the random network is consistently lower across the examined time period. The trend in the authority scores of cases cited in the cross-jurisdictional network (Figure 9B) is less uniform. We observe, in contrast to the complete network, that the authority scores of cited cases start off low between 1940 and 1970, before sharply increasing between 1970 and 1990, where they peak. This peak in scores is likely due to the fact that in our data most of the citation activity starts in the mid-twentieth century. The peak in scores over this period indicates that extensive citation was being made to a select group of cases of heavily cited cases. From 1990, the average authority score proceeds to steadily decline over the following 30 years toward 2020.

The analysis of the authority scores in the cross-jurisdictional network and the complete network both demonstrate a steady decline in the authority score of cases cited over time, although the points at which the decline commences differ. This is consistent with Assumption 1, which proposes that the preference of judges to cite high importance cases will have reduced over time as the practice of foreign citation grows more widespread. However, the fact that the trend of decreasing authority scores is mirrored in the random networks provides an indication that the fall in importance, as measured by the authority score, may in fact be a consequence of the growth in the size of the network rather than a conscious decision on the part of judges to cite lower impact cases, as envisaged by Assumption 1.

The decline in authority scores in the cross-jurisdictional network begins in 1990. From this point in time we observe two patterns that are common to both networks: a steep increase in the number of cases entering the networks (Figure 5A; Section 3.4) and an increase in the number of cases cited per case (Figure 5B). The period from 1990 onward is marked by increased digitization both of the judgments themselves and the platforms used to facilitate their dissemination and retrieval. Technological advances in the online legal research domain in particular have significantly increased the ease with which judges and lawyers are able to access foreign jurisprudence and engage in comparative analysis [48,49]. Prior to the widespread digitization of legal sources, discovery of case law, both foreign and domestic, largely depended on access to printed collections of law reports or to textbooks, both of which tended to be limited to the treatment of well-known cases. The ability to access foreign case law in volume online is likely to have resulted in a broadening of the horizons of judges, enabling them to simultaneously cast their nets wider across a growing number of bodies of foreign jurisprudence and deeper into case law pertaining to esoteric issues.

Accordingly, it is difficult to decouple the emphasis placed by judges on the importance of a foreign case when considering whether to cite it from the effects of dramatically improved accessibility of foreign case law over time and its apparent effect on the growth of the networks. However, the overall trend is that over time, and certainly since the advent of digital access to case law, citations to foreign authority have increased and the importance of the cases that are being cited, as measured by their authority scores, has decreased. This, in turn, indicates an increased willingness among judges to make use of foreign case law and a reduced tendency to confine reference to landmark cases.

Assumption 2 proposes that the preference of judges to cite cases that are well-grounded in existing case law will have reduced over time as the practice of foreign citation grows more widespread. We use the hub score computed by HITS as a proxy for how well-grounded a case is in earlier authority.

The trends in the evolution of the average hub scores closely resemble those of the authority scores. In the complete network, shown in Figure 10A the hub scores start high and steadily decline over time. The same steady decline is reflected in the movement of the hub score in the random network, shown in orange. The evolution of the hub score in the cross-jurisdictional network and the random model generated from its degree distribution, shown in Figure 10B, is less straightforward. The hub scores in the cross-jurisdictional model are generally low throughout the observed period. The scores are seen to peak in 1990 and then to continually decline from that point onward. As with our analysis of the evolution of the authority scores, this trend is consistent with Assumption 2. However, the movement of the hub score in the random cross-jurisdictional network provides strong evidence that the decline in hub scores from 1990 onward is a consequence of the increasing size of the network rather than a conscious change in approach on the part of judges.

FIGURE 10

Hub scores of cited cases in (A) the complete network and (B) the cross-jurisdictional network between 1940 and 2020. For the real networks the hub scores are shown in blue, for the random networks the scores are shown in orange.

As with our analysis of the evolution of the authority scores, our analysis of the hub scores do not provide sufficient evidence to enable us to state that the reduction in hub scores is a direct consequence of judges lowering their attention to how well-grounded a particular foreign case is in the domestic authority of the country from which it emanates. Rather, the rise of widespread digital access to case law from 1990 onward is likely to be playing the prominent role in this respect.

Our analysis of the authority score raises a general question as to its effectiveness of as a measure of importance in large evolving case law citation networks. In their study, Fowler and Jeon [17] compared the top ten ranking cases by authority score in their network with three sets of expert rankings of the most influential United States Supreme Court decisions and found that all but one of those cases appeared in at least two of the three sets of rankings. Their analysis therefore revealed a strong association between the authority score and importance. In order to evaluate the validity of the authority when applied to the data in our network, we compare the relationship between case indegree and authority score (the independent variables) with whether a case has been reported in the leading series of law reports for England and Wales, The Law Reports. We use the inclusion of the case in The Law Reports as a proxy for importance and this serves as our dependant variable. For this comparison, we induce the sub-graph of citations internal to the United Kingdom from the complete network and compute the authority scores in that network. Then for each measure (authority score and indegree), we sample to the top 100 cases, the bottom 60 cases and 60 additional cases around the middle yielding 280 cases for each measure. We then manually check whether the cases for each measure were reported in The Law Reports. The results of a logistic regression, along with Pearson correlation scores, on the relationship between these measures and importance, shown in Table 3, indicate that there is a significant relationship between indegree and importance using The Law Reports as a benchmark. The authority score, on the other hand, has a weaker association with importance in our data.

TABLE 3

| Independent variable | Coef | Standard error | p-value | Pearson correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authority score | 92.8268 | 91.998 | 0.313 | 0.06 |

| Indegree | 0.0081 | 0.001 | 0.0 | 0.55 |

Relationship between importance and indegree/authority in United Kingdom cases. N = 280. Coefficients and standard errors calculated using logit. The dependant variable is whether the case was reported in The Law Reports.

4.2.2 The Role of Geographic Proximity

In Assumption 3, we draw on Spottiswood’s [29] study of the High Court of Australia and assume that in making choices as to which foreign country to cite from, judges will generally favor the jurisprudence of countries that share similar values. We use geographic proximity as the proxy for similarity and assume that countries that are close in distance are more likely to share values than countries that are separated by larger distances.

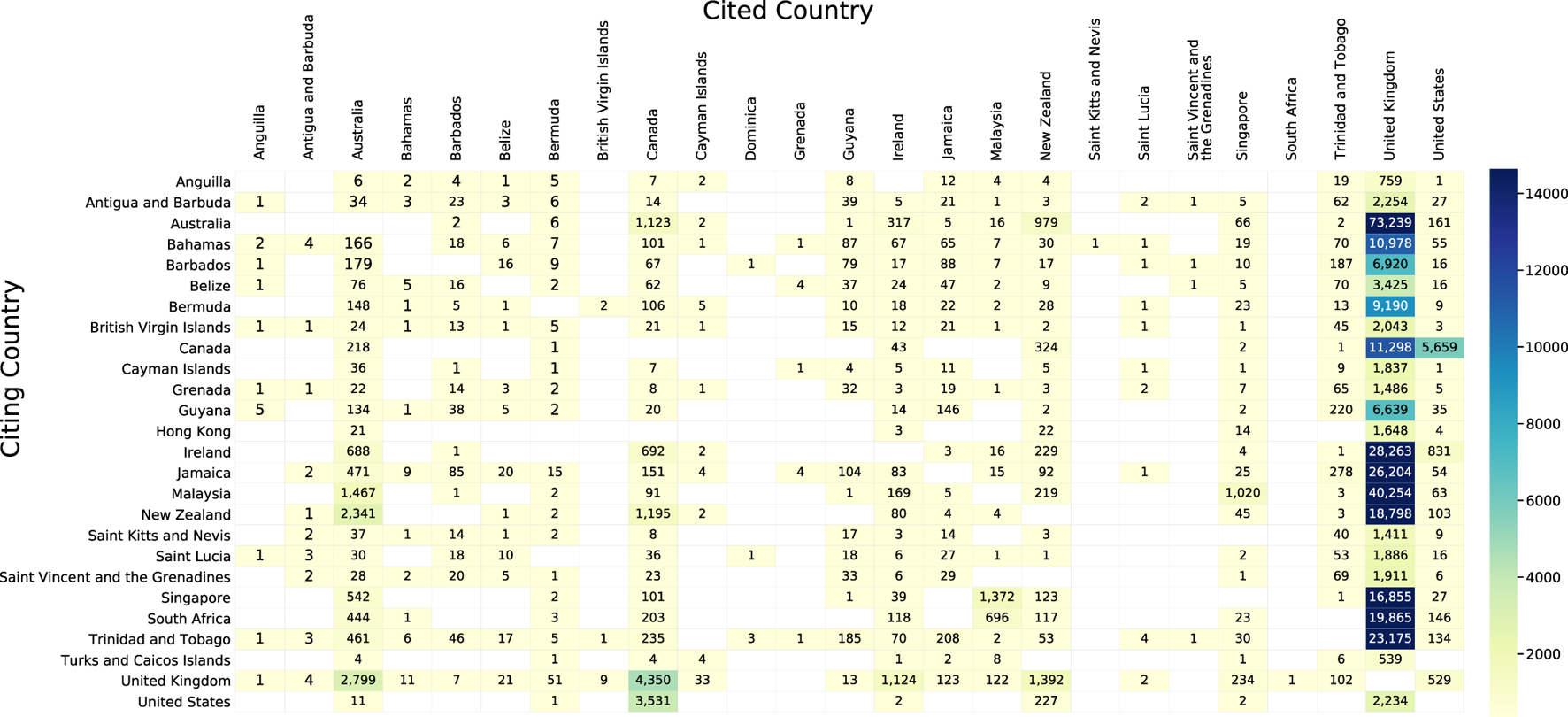

United Kingdom We plot the matrix of citation interactions between the countries in the cross-jurisdictional network in Figure 11. Virtually all countries, with the exception of the United States, direct the bulk of their outward citations toward the United Kingdom. This is likely due to historic factors: all of the countries in the network were at some point subject to British imperial rule and, as a consequence, have systems of law modeled on that used in England. Moreover, all countries, with the exception of the United States and the United Kingdom itself, at some point had the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as their final court of appeal (this remains the case for twelve of the countries in the network).

FIGURE 11

Heatmap of citations between countries in the cross-jurisdictional network. Citing countries are show on the left axis and citing countries are shown on the top axis.

North America 58% of United States outward citations were to Canadian cases. In this respect, our findings are broadly consistent with those of Zaring [28]. 64% of outward Canadian citations were to decisions emanating from courts in the United Kingdom. This is not surprising given Canada’s close historic ties with the United Kingdom. However, the second country most cited by Canada is the United States, the decisions of which amount to 31.7% of Canada’s outward citations.

Asia-Pacific When references to decisions of courts in the United Kingdom are removed, Malaysian courts are seen to prefer the case law of Singapore (33.5% of Malaysian outward citations) and Australia (48.2%), and to a lesser extent, New Zealand (7.2%). New Zealand directs most of its non-United Kingdom outward citations to its closest neighbor, Australia (63.1% of New Zealand’s non-United Kingdom outward citations). The flow of outward citations from Australia to New Zealand is also high (36.5% of Australia’s non-United Kingdom citations), although Australian courts are shown to have a stronger preference for Canadian jurisprudence (41.9%).

Caribbean Countries in the Caribbean region stand out as the most cosmopolitan users of foreign case law, spreading their outward citations across neighboring jurisdictions in the region. However, outward citations to foreign case law by courts in Caribbean jurisdictions are concentrated on Australia, Canada, United Kingdom and the United States.

To gain a clearer understanding of the extent to which geographic distance between countries influences the selection of foreign case law, we analyze the extent to which there is a negative correlation between distance and citation count. A strong negative correlation would provide support for Assumption 3. We calculate the log distances in kilometres between the capital cities of each pair of countries in our data along with the total inward and outward citations between each pair. Owing to its peculiar role from a historical perspective, we exclude the United Kingdom from our analysis. Further, in view of the fact that countries in the Caribbean region cite to many different countries, we compute the correlations both with and without these countries. Our analysis is shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Country | Pearson correlation coef (w/Caribbean) | Pearson correlation coef (w/o caribbean) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | −0.055 | −0.565 |

| United States | −0.409 | −0.727 |

| Canada | −0.391 | −0.649 |

| Australia | −0.776 | −0.759 |

| New Zealand | −0.789 | −0.773 |

| Singapore | −0.889 | −0.888 |

| Malaysia | −0.938 | −0.929 |

| South Africa | −0.408 | −0.408 |

| Hong Kong | −0.305 | −0.305 |

| Ireland | 0.268 | 0.075 |

Correlations between log geographic distance and number of citations. Geographic distance is measured in kilometres between national capital cities. “Overall,” shown in bold, denotes correlation calculated on all country pairs (excluding the United Kingdom). Correlations for individual countries are calculated using only the subset of country pairs each country belongs to. Larger negative values indicate stronger negative correlations between distance and citation count.

When the Caribbean data is included in the analysis, the overall correlation is weak (−0.055), although the strength of the correlation is high in countries situated in Asia and Australasia. In contrast, the negative correlation becomes stronger (−0.565) when we exclude Caribbean citation activity, with a marked increase in the observed correlation for Canada and the United States. The correlation for Ireland is weak in both scenarios because as shown in Figure 11 the majority of Ireland’s citations are to the United Kingdom, which was excluded from the analysis.