- 1Laboratory of Functional Physiology and Valorization of Bio-Resources (UR17ES27) at the Higher Institute of Biotechnology of Beja (ISBB), University of Jendouba, Jandouba, Tunisia

- 2National Institute of Technology and Sciences of Kef, University of Jendouba, Jandouba, Tunisia

- 3Laboratory of Physico-Chemistry of Materials (LR01ES19), Faculty of Sciences of Monastir, Monastir, Tunisia

- 4Faculty of Sciences of Gafsa, University of Gafsa, Gafsa, Tunisia

- 5Laboratory of Molecular Chemistry and Natural Substances, University of Moulay Ismail, Faculty of Sciences, Meknes, Morocco

- 6Department of Physics, College of Science, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 7Department of Physics, College of Science, Northern Border University, Arar, Saudi Arabia

- 8Department of Physics, College of Science, University of Ha’il, Ha’il, Saudi Arabia

- 9Laboratory of Advanced Materials and Interfaces (LIMA), University of Monastir, Faculty of Sciences of Monastir, Monastir, Tunisia

An organoammonium-dihydrogenphosphate compound (C7H11N2)H2PO4 was synthesized and characterized. The intra-and intermolecular interactions responsible for the stability of our compound within the crystal lattice have been thoroughly discussed. FT-IR spectroscopic analyses have confirmed the well atomic organization and stability of our compound. Using the RDG and NCI approaches, we identified strong N—H···O and O—H···H hydrogen bonds, along with notable van der Waals (vdW) interactions between the cationic units and the phosphate anion, confirming the key role of non-covalent forces in stabilizing the crystal structure. Intermolecular interactions were further elucidated by Hirshfeld surface analysis. Moreover, dispersion-corrected Density Functional Theory provided insights into chemical reactivity properties. The compound was also analyzed using solid-state spectroscopies. This contribution enhances the understanding of the structural diversity of organic-dihydrogenphosphate compounds.

1 Introduction

Organophosphorus compounds are important in everyday applications ranging from agriculture to medicine and are used in flame retardants and other materials (Montchamp, 2014). Although organophosphorus chemistry is known as a mature and specialized area, researchers would like to develop new methods for synthesizing organophosphorus compounds to improve the safety and sustainability of these chemical processes. In the last years, several syntheses of organic-cation monophosphate crystals have been carried out. During the systematic investigation of interaction between monophosphoric acid with organic molecules, numerous structures of monophosphates with organic cations have been described: (C5H6N5)H2PO4 (Vratislav et al., 1979), (C2H6NO2)H2PO4 (Averbuch-Pouchot et al., 1988), (C5H7N2)H2PO4.H2O (Bag et al., 1991), (C7H10NO)H2PO4 (Eaoud et al., 1999), (C6H22N4) (HPO4)2.2H2O (Kamoun et al., 1991), (C3H12N2)HPO4.H2O (Kamoun and Jouini, 1990), (C4H14N2)HPO4.2H2O (Kamoun et al., 1990) and (C4H15N3)HPO4.2H2O (Kamoun et al., 1995), etc. These complexes have been extensively investigated because of their numerous practical and potential uses in various fields such as biomolecular sciences, catalysts, fuel cell, liquid crystal-material developers and quadratic non-linear optic (Gani and Wilkic, 1955; Mass et al., 1993; Olivier et al., 1995; Oueslati et al., 2005; Wang et al., 1996; Yuichi et al., 1995). The phosphate anions generally observed are the acidic ones [HPO4]2- or [H2PO4]-. Such anions are interconnected by strong hydrogen bonds so as to build infinite networks with various geometries: ribbons (Baouab and Jouini, 1998), chains (Averbuch-pouchot and Durif, 1987; Averbuch-Pouchot et al., 1988), two-dimensional networks (Averbuch-Pouchot et al., 1988; Bagieu-Beucher, 1990; Blessing, 1986) and three-dimensional networks (Averbuch-pouchot et al., 1989).

Molecular crystals are crystalline solids consisting of two or more different molecular entities arranged in a periodic lattice structure and held together by intermolecular non-covalent interactions. The combination of organic amines with inorganic dihydrogenphosphate moieties has garnered significant interest due to the possibility of merging the structural and physicochemical properties of both components, leading to the formation of molecular crystals and salts with particular features (Balamurugan et al., 2010; Belghith et al., 2015; Budzikur et al., 2022; Das et al., 2017; Fujita et al., 2009; Guelmami et al., 2023; Kaabi et al., 2003; Mahé et al., 2013; Mrad et al., 2011; Rayes et al., 2016).

In organoammonium dihydrogenphosphates, the structural integrity of the crystals is primarily derived from a supramolecular hydrogen bonding network, particularly O—H···O and N—H···O hydrogen bonds. In addition, C–H … O hydrogen bonds have been observed, which play a supportive role in determining the crystal packing and overall stability (Fujita et al., 2009; Pandian et al., 2015).

In this context, we report herein the chemical preparation of an organic phosphate material, templated with a 4-dimethylaminopyridine derivative (DMAP). The latter molecule is a cyclic diamine, also called N, N-dimethylpyridin-4-amine (IUPAC name), with the chemical formula (CH3)2NC5H4N (Balachandran et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2007). The crystals of the studied (C7H11N2)H2PO4 were synthesized by slow evaporation at room temperature, and was characterized by using single-crystal X-ray diffraction and infrared spectroscopy IR.

To gain deeper insight into the structural, electronic, and intermolecular interaction profile of (C7H11N2)H2PO4, a comprehensive theoretical investigation was carried out. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed to analyze the frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO), providing essential information on the compound’s electronic reactivity and kinetic stability. The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface was generated to visualize charge distribution and identify potential sites for nucleophilic and electrophilic interactions. Furthermore, the Electron Localization Function (ELF) and Localized Orbital Locator (LOL) analyses were employed to map electron density localization, revealing bonding characteristics and the presence of lone pairs. The NCI and RDG approaches revealed the presence of significant N—H···O and O—H···H hydrogen bonds, as well as dispersive van der Waals contacts between the organic cations and the phosphate anion, highlighting the key role of non-covalent interactions in the molecular assembly. To complement the theoretical approach, Hirshfeld surface analysis was conducted to quantify and visualize the intermolecular interactions within the crystal packing, offering detailed insight into the nature and extent of hydrogen bonding, π–π stacking, and van der Waals forces that stabilize the solid-state structure.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemical preparation

An aqueous solution of monophosphoric acid (85%, d = 1.7) was added to an organic molecule, 4-dimethylaminopyridine, in the molar ratio 1:1. The resulting solution was slowly evaporated at room temperature for 3 weeks until colorless, parallelepipedic crystals of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 were formed. The structure was determined using single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

The 4-dimethylaminopyridinium dihydrogenmonophosphate (C7H11N2)H2PO4 denoted as 4-DMAPMP crystallizes in the triclinic system, with the space group P

2.2 Infrared spectroscopy

IR spectrum was recorded at room temperature with a Biored FTS 6000 (F.T.I.R) spectrometer over the wave number range of 4,000–400 cm-1 with a resolution of about 4 cm-1. Thin transparent pellets were used by compacting an intimate mixture obtained by shaking 2 mg of the sample in 100 mg of KBr.

2.3 Computational details–DFT calculations

All quantum chemical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 software package (Frisch et al., 2009). The molecular geometry of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 was fully optimized in the gas phase using the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method with the B3LYP functional and the 6-31 G(d,p) basis set. Frequency calculations were conducted to ensure that the optimized structure corresponds to a true energy minimum, with no imaginary frequencies observed. The B3LYP functional combined with the 6-31G(d,p) basis set was chosen as it offers a well-established balance between accuracy and computational cost and has been widely employed in similar studies of organic and bioactive molecules, ensuring both reliability of the results and comparability with previous work.

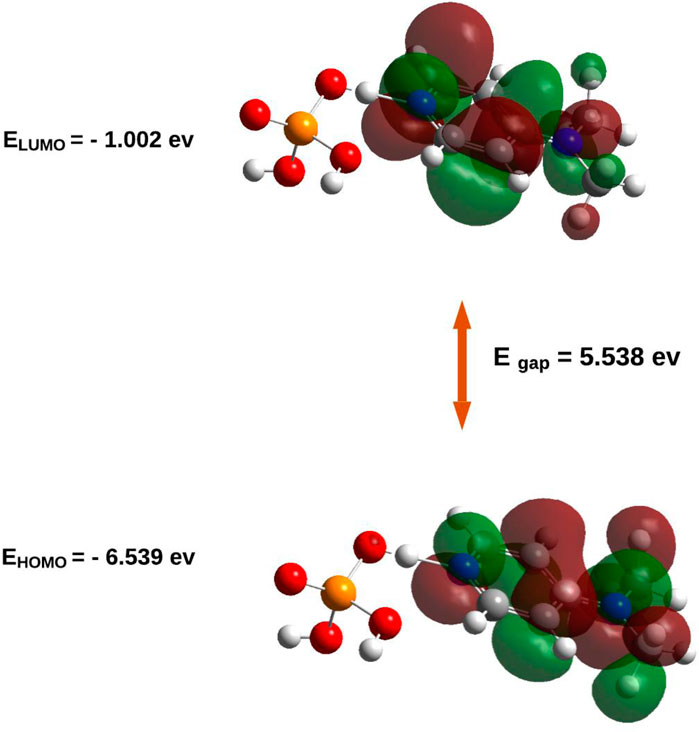

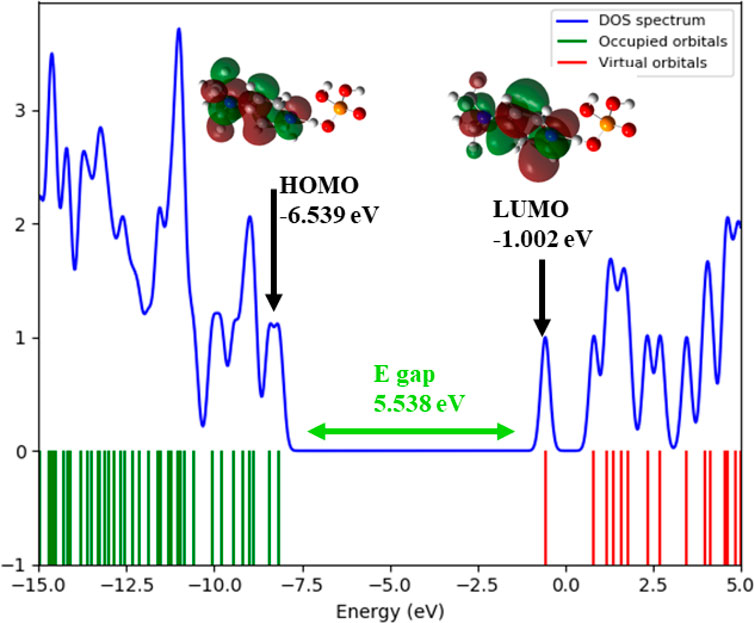

2.4 Frontier molecular orbital (HOMO–LUMO) analysis

The energies and spatial distributions of the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) were extracted from the optimized geometry. The HOMO–LUMO energy gap (ΔE) was calculated to assess the kinetic stability and electronic reactivity of the compound. Orbital visualizations were rendered using GaussView 6.0 (Dennington and Millam, 2000). The Density of States (DOS) was plotted using the GaussSum program (K Boyle et al., 2005).

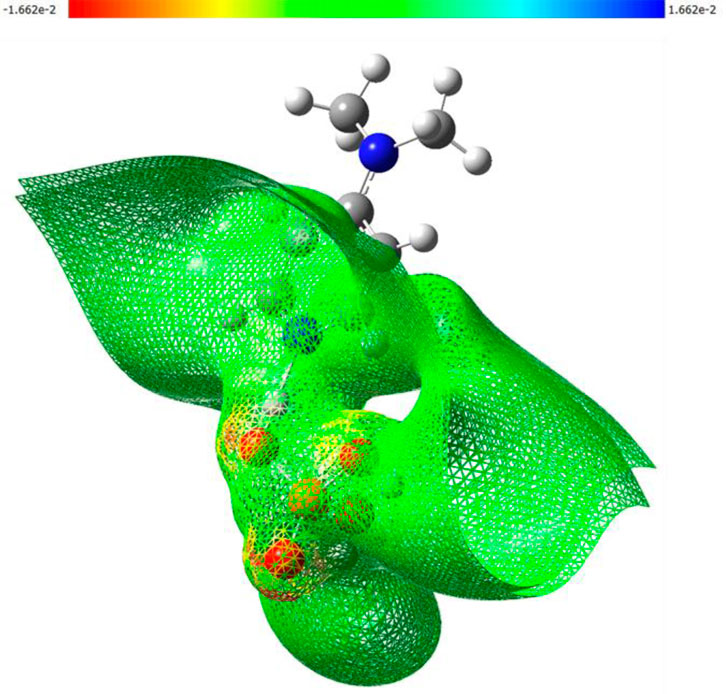

2.5 Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) mapping

The molecular electrostatic potential surface was computed at the same level of theory (B3LYP/6-31 G(d,p)) based on the optimized structure. The MEP was mapped onto the electron density surface (isovalue = 0.001 a.u.) to visualize charge distribution and predict electrophilic and nucleophilic regions. Color-coded surface plots were generated with red, green, and blue regions representing areas of negative, neutral, and positive potential, respectively (Gassoumi et al., 2023).

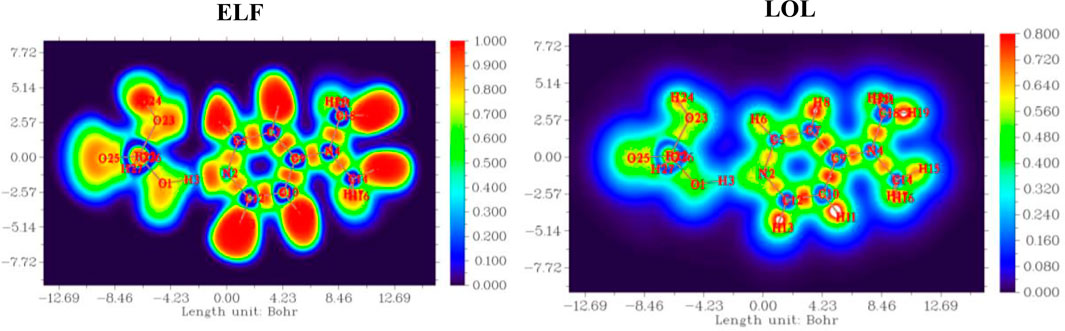

2.6 Electron localization function (ELF) and localized orbital locator (LOL)

ELF and LOL analyses were performed using the Multiwfn program based on the wavefunction file obtained from Gaussian. These topological functions were computed to assess the localization of electron density within covalent bonds and lone pair regions. 2D and 3D visualizations of the ELF and LOL surfaces were produced to identify zones of high electron localization, particularly around bonding regions, heteroatoms, and delocalized systems (Jacobsen, 2008; Lu and Chen, 2012; Zaki et al., 2024).

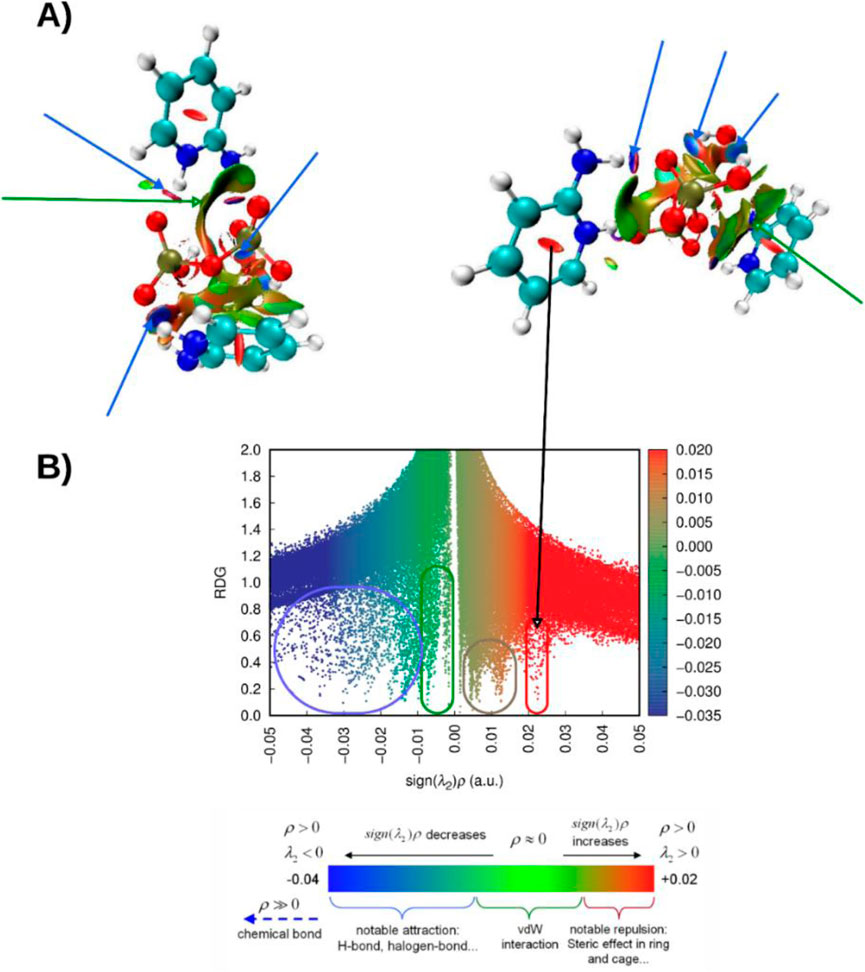

2.7 RDG and NCI analysis

The optimized geometries were employed for the analysis of non-covalent interactions (NCIs) using the Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) method. Wavefunction files (wfn or.fchk) generated from the DFT-optimized structures were used as input for RDG calculations performed with the Multiwfn 3.8 software package.

The RDG function was evaluated across a three-dimensional grid to map regions of low electron density gradient, which are indicative of non-covalent interactions. The nature and strength of these interactions were further characterized using the sign(λ2)ρ descriptor, where ρ denotes the electron density and λ2 is the second eigenvalue of the electron density Hessian matrix. This descriptor distinguishes between attractive (negative sign(λ2)) and repulsive (positive sign(λ2)) interactions, with the density magnitude reflecting interaction strength.

Three-dimensional RDG iso-surfaces were generated and visualized using Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD), typically with an isovalue of 0.5 a.u. The isosurfaces were color-coded according to the value of sign(λ2)ρ: blue regions indicate strong attractive interactions such as hydrogen bonding, green denotes weak dispersive forces like van der Waals interactions, and red highlights repulsive steric effects. Directional arrows were added to facilitate interpretation of interaction sites within the molecular structure.

Additionally, two-dimensional scatter plots of RDG versus sign(λ2)ρ were constructed to provide a quantitative analysis of the identified NCIs. These plots help distinguish between different interaction regimes, enabling a clear classification of bonding, dispersive, and steric contributions. The RDG approach, combining topological and visual analysis, thus provided a comprehensive description of the non-covalent landscape within the studied systems (Medimagh et al., 2023).

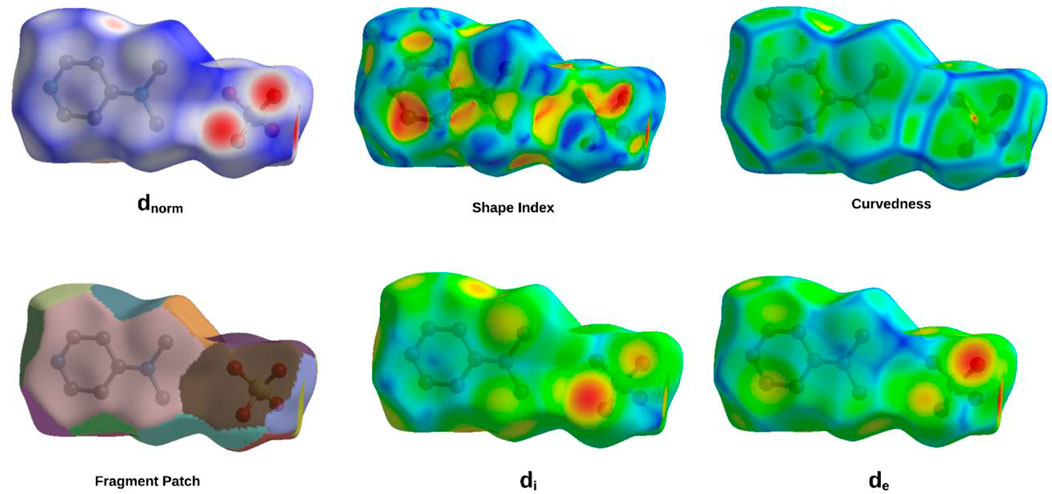

2.8 Hirshfeld surface analysis

Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed using CrystalExplorer 17.5 (Hirshfeld, 1977; Spackman et al., 2021) to quantitatively and visually examine the intermolecular interactions within the crystal structure. The molecular surface was mapped using several descriptors, including the normalized contact distance (dnorm), shape index, curvedness, internal distance (di), and external distance (de). The dnorm mapping was used to highlight regions of close intermolecular contacts, with red, white, and blue areas indicating distances shorter than, equal to, or longer than the sum of van der Waals radii, respectively. The shape index and curvedness surfaces were employed to identify potential π···π stacking interactions and to assess the local surface curvature, respectively. Additionally, fragment patch mapping was conducted to visualize the spatial distribution and identity of adjacent interacting molecules (Spackman and Jayatilaka, 2009; Spackman and McKinnon, 2002).

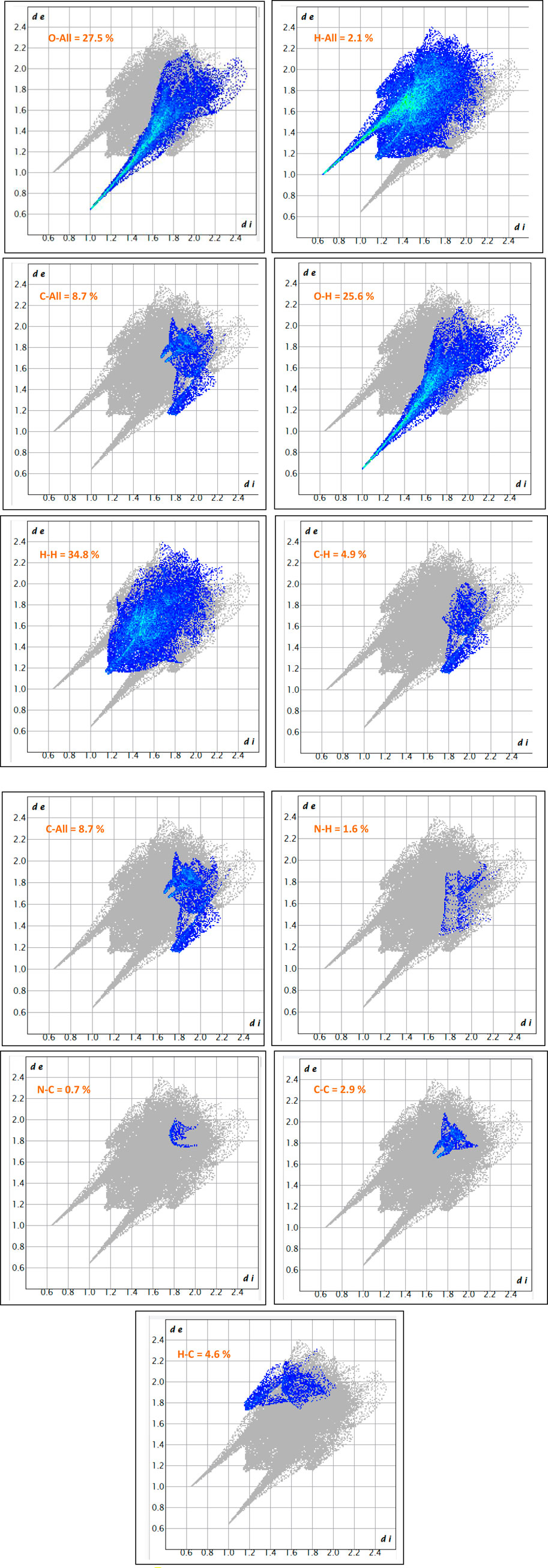

2.9 Fingerprint plot generation

Two-dimensional (2D) fingerprint plots were generated from the Hirshfeld surface data to provide a detailed, quantitative representation of the intermolecular contacts. These plots were constructed by calculating the internal (di) and external (de) distances from each point on the Hirshfeld surface to the nearest atom within the same and neighboring molecules, respectively. The resulting (di, de) pairs were plotted using a color gradient to indicate contact frequency. The overall fingerprint was subsequently decomposed into individual contact contributions (e.g., H···H, N···All, O···H, H···O), allowing for the identification and quantification of each interaction type’s relative contribution to the crystal packing.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Structure description

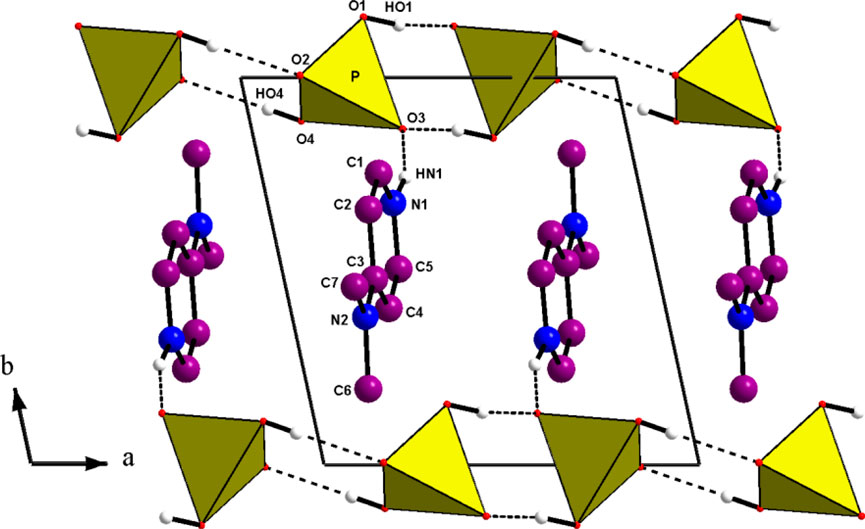

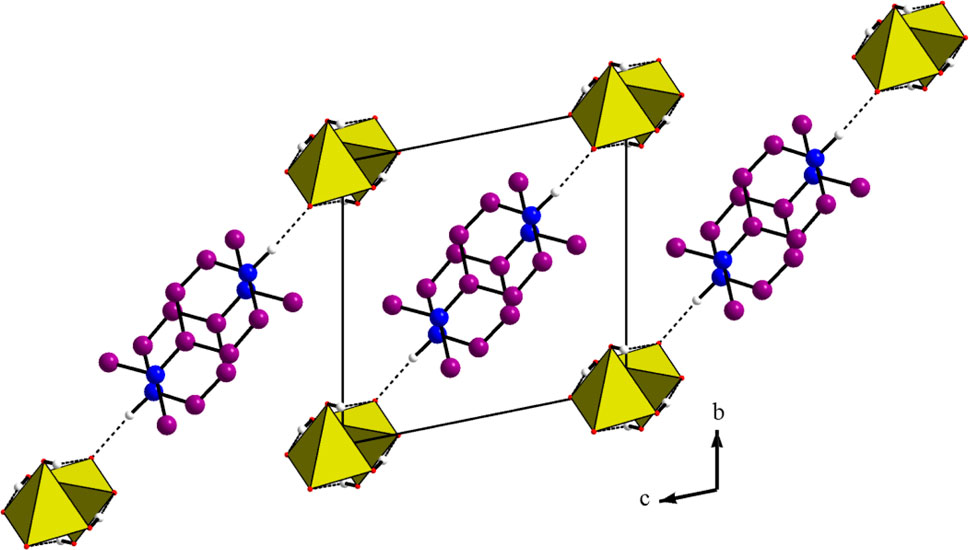

The main feature of the atomic arrangement in (C7H11N2)H2PO4 is the existence of infinite chains with the formula

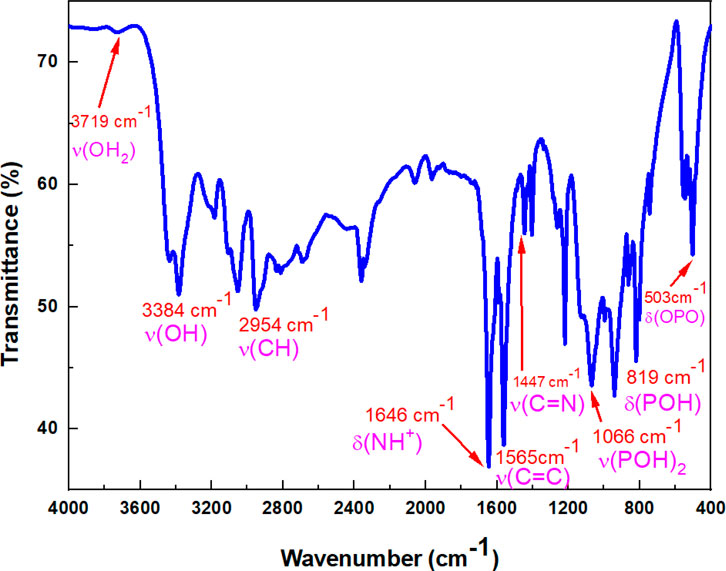

The D(donor)—H…A(acceptor) hydrogen bonds are listed in Table 1 with an upper limit of 1.85(3) Å for the H…A distances and a lower limit of 163.7(1)° for the D—H…A bond angles (Brown, 1976; Steiner and Saenger, 1994). Thus, this structure exhibits two types of hydrogen bonds: O(P)—H…O connects the acidic anions, giving rise to the chains and one N—H…O establishes contact with the anionic chains. This atomic arrangement includes three hydrogen bond donors (1 N and two O atoms) and two hydrogen bond acceptors (two O atoms). The oxygen atom O(2) is single acceptor, whereas O(3) is a twofold acceptor.

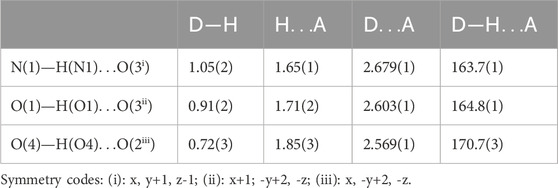

3.2 Infrared spectroscopy

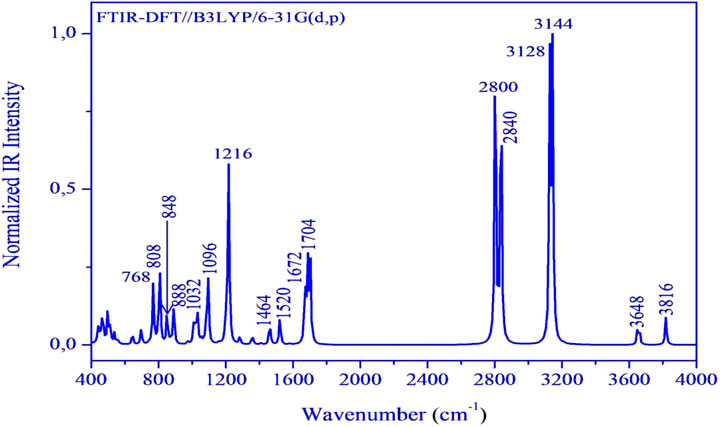

The IR spectrum of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 is depicted in Figure 3. Table 2 describes the spectral data and the band assignments of our compound.

The unperturbed PO43- ion is a tetrahedron with point group symmetry Td. The normal modes of vibrations have wave numbers at approximately 938, 420, 1,017 and 567 cm-1 for n1(A1), n2(E), n3(F2), and n4(F2), respectively (Nakamoto, 1986). All of these modes are Raman active, whereas the triply degenerate modes n3 and n4 are infrared active. The group-theoretical analysis shows that the number of normal modes of PO4 tetrahedron is given by the representation

3.3 Theoretical FT-IR spectrum

Herein, we have meticulously examined the vibrational assignments of the functional groups present in our material. The infrared spectrum of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 is illustrated in Figure 4. The calculated frequencies have been scaled by a factor of 0.9608 to account for anharmonic effects. Notably, vibrational modes of varying intensities-low, medium, and high-are observed at 3,666 cm-1, 3,505 cm-1, 3,005 cm-1, 2,850 cm-1, 2,729 cm-1, and 2,690 cm-1 corresponding to the stretching vibrations of–OH, –NH, –CH, –CH3 groups and harmonics, which corroborate the experimental vibrational frequencies, which are localized at 3,433 cm-1 to 3,725 cm-1, 2,829 cm-1 and 3,020 cm-1, 2,815 cm-1, 2,692 cm-1, respectively. The bending modes observed, ranges from 1,407 cm-1 to 1,638 cm-1 are attributed to various functional groups including–OH, –CH3, –NH, –C=N, –C=C, as well as skeletal stretching vibrations. These frequencies have been experimentally confirmed to fall within the same range. The streaching modes corresponding to the P(OH)2 groups are observed at 992 cm-1 and 1,053 cm-1, confirming experimental findings at 996 cm-1 and 1,066 cm-1. Furthermore, the frequency values ranging from 738 cm-1 to 853 cm-1, which were experimentally recorded between 746 cm-1 and 864 cm-1 are associated with the vibrations of the phosphate group ω(PO2), ρ(PO2), and g(P–O–H) stretching vibrations. Finally, frequency peaks below 600 cm-1, specifically at 484 cm-1 and 499 cm-1 are linked to the assignments of PO2 and O–P–O groups. It is concluded that a strong correlation between the theoretical and experimental results substantiates the robust atomic organization and stability of our compound within the crystal lattice.

3.4 Hirshfeld surface analysis

The fingerprint plot analysis, displayed in Figures 5, 6, reveals a well-defined hierarchy of intermolecular contacts that collectively orchestrate its crystal packing. Dominating the interaction landscape, N-involved contacts (N–All) account for an exceptional 57.6% of the Hirshfeld surface, with sharp spikes at low di and de values signifying strong, directional hydrogen bonds—confirming nitrogen’s central role in stabilizing the supramolecular framework. These are robustly complemented by H…H contacts (34.8%), whose broad, diffuse region reflects widespread van der Waals forces, essential for efficient packing and void minimization. Oxygen-mediated interactions, particularly O…H (25.6%) and H…O (21.7%), display distinct low-distance spikes characteristic of classical hydrogen bonding motifs (e.g., O–H…O, C–H…O), cumulatively contributing nearly 47.3%, and underscoring the critical role of oxygen atoms in forming a dense, directional hydrogen-bond network. The broader O–All category (27.5%) reinforces the oxygen atoms’ significance as key interaction sites. Beyond these major contributors, C-involved interactions (C–All: 8.7%, C–H: 5.1%, H–C: 4.6%) and minor contacts involving C–C (3.2%), N–C (2.2%), and O–O (2.1%) offer structural fine-tuning, enabling subtle but meaningful adjustments to the packing efficiency and cohesion. Lesser interactions like N–H (1.6%), O–C (0.6%), and H–All (2.1%) play marginal roles, reflecting either low-frequency occurrences or weaker binding scenarios. Altogether, this quantitative contact mapping firmly establishes nitrogen-mediated hydrogen bonding as the principal force steering the crystal assembly, reinforced by a robust hydrogen-bond network involving oxygen and a supportive matrix of van der Waals and dispersive contacts. Such detailed insight into atomic-level interactions provides a solid basis for understanding the compound’s stability, packing behavior, and potential functional properties in the solid state.

Figure 6. Hirshfeld surface maps of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 highlighting key intermolecular interactions via Dnorm, Di, De, fragment patch, curvedness, and shape index.

The comprehensive Hirshfeld surface analysis of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 (Figure 6), integrating the dnorm, Shape Index, Curvedness, di, and de surfaces, reveals a cohesive picture of the compound’s intricate intermolecular landscape. The dnorm surface clearly highlights pronounced red spots—particularly on the oxygen atoms of the phosphor group—signifying strong, localized contacts such as O–H…O hydrogen bonds, which dominate the crystal cohesion. Complementing this, widespread white areas suggest close packing dominated by non-specific van der Waals interactions, while the diffuse blue regions point to zones of lower contact density or minor voids. The Shape Index further refines this picture, displaying characteristic adjacent red and blue triangular motifs on the aromatic regions, indicative of π…π stacking interactions; this underscores the role of precise shape complementarity in molecular alignment. The curvedness surface adds another dimension, with flat, low-curvature zones (green/yellow) corresponding to extended stacking or planar contacts, and highly curved patches (blue/red) identifying discrete localized interactions at molecular peripheries. Meanwhile, the di and de surfaces offer a spatial dissection of internal versus external electron density, with red zones on the de map—particularly around oxygen atoms—confirming the close proximity of hydrogen donors from neighboring molecules, thus corroborating the hydrogen bonding observed in the dnorm map. Altogether, this multi-surface interpretation illustrates how (C7H11N2)H2PO4 balances strong directional hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, and van der Waals forces to stabilize its crystal lattice. These qualitative observations can be further quantified via two-dimensional fingerprint plots, offering a statistical breakdown of each contact type’s contribution to the overall solid-state architecture.

3.5 Electronic properties

The results of this analysis are summarized in Figures 7, 8.

Figure 7. HOMO/LUMO energies and orbital visualization calculated at B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level of theory.

Figure 8. 3D-MEP surfaces illustrating the electrostatic potential distribution calculated at B3LYP/6-31G (d,p) level of theory.

The electronic properties of (C7H11N2)H2PO4were elucidated through an analysis of its frontier molecular orbitals (Figure 8). The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), with an energy of −6.539 eV, is primarily localized on the organic cation, exhibiting significant electron density around the nitrogen atoms and their adjacent carbon centers. This spatial distribution suggests that these regions are the most accessible for electron donation, influencing the compound’s nucleophilic character. Conversely, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) was calculated at −1.002 eV, with its electron density also largely concentrated over the organic cation, particularly around the nitrogen atoms and the conjugated ring system. This indicates the primary sites for electron acceptance, defining the compound’s electrophilic nature. The substantial energy gap (Egap) between the HOMO and LUMO was determined to be 5.538 eV. This relatively large energy gap is indicative of the compound’s significant kinetic stability, suggesting that considerable energy is required for electronic excitation or charge transfer processes, thereby contributing to its overall chemical inertness under typical reaction conditions.

This electronic structure is further supported by the Density of States (DOS) spectrum, which offers a more comprehensive view of the distribution of electronic states across the energy range. As depicted in Figure 9, the DOS plot reveals that the electronic states are densely populated below the Fermi level, corresponding to the occupied orbitals (green lines), with a sharp decrease in state density near the HOMO level (−6.54 eV). Above the Fermi level, a clear gap is observed before the reappearance of virtual orbitals (red lines), commencing at the LUMO level (−1.001 eV). The total DOS profile, represented by the blue curve, confirms the absence of states within this 5.537 eV energy window, thus reinforcing the presence of a wide HOMO–LUMO gap. This electronic configuration corroborates the high chemical stability and low reactivity of the compound under ambient conditions, consistent with its insulator-like behavior.

Figure 9. . Density of States (DOS) plot that illustrates the HOMO, LUMO, and energy gap of (C7H11N2)H2PO4.

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface of (C7H11N2)H2PO4, as depicted in Figure 8, provides a comprehensive visualization of its charge distribution and potential sites for intermolecular interactions. The map clearly identifies regions of pronounced negative potential (red contours, reaching −1.662 × 10−2 a.u.) predominantly centered on the oxygen atoms of the dihydrogen phosphate. This high electron density on the phosphate oxygen atoms renders them potent nucleophilic sites and efficient hydrogen bond acceptors, critical for forming stabilizing interactions within the crystal lattice. In contrast, while positive potential regions (blue contours) are less intensely visualized on the organic cation, the overall surface of the organic moiety appears neutral to slightly positive (green to yellow), indicating the delocalization of the positive charge associated with the protonated nitrogen atom. The distinct electrostatic separation between the anionic and cationic components, as visualized by the MEP map, supports the formation of a robust hydrogen-bonding network and highlights the importance of electrostatic forces in the crystal packing arrangement.

3.6 Electron localization function (ELF) and localized orbital locator (LOL) analysis

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the electron localization patterns and bonding characteristics within the complex, both the Electron Localization Function (ELF) and the Localized Orbital Locator (LOL) were computed, as presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Electron localization function (ELF) and localized orbital locator (LOL) maps of (C7H11N2)H2PO4.

Both functions consistently revealed prominent regions of high electron localization (red to yellow contours, approaching values of 1.0) around the atomic nuclei, corresponding to the tightly bound core electrons. Critically, these high-localization basins extended between bonded atoms (C-C, C-N, C-H), unequivocally depicting the presence of localized electron pairs forming strong covalent bonds. Furthermore, distinct high-ELF and high-LOL basins were identified on the nitrogen atoms, signifying either localized lone pairs or highly polarized electron density associated with the N-H bonds in the protonated species. Intermediate values (green to cyan) were observed across the heterocyclic ring system, indicative of a degree of electron delocalization that contributes to its overall stability and aromatic character. These complementary analyses, while derived from different theoretical frameworks, consistently underscore the localized nature of core and bonding electrons, providing robust visual evidence for the compound’s intrinsic bonding topology and highlighting specific electron-rich regions that are fundamental to its chemical reactivity and propensity for intermolecular interactions.

3.7 NCI-RDG analysis results

Figure 11 presents a comprehensive analysis of non-covalent interactions (NCIs) within the studied molecular systems, employing the Reduced Density Gradient (RDG) method. This approach provides both visual and quantitative insights into weak intermolecular and intramolecular forces, contributing to a deeper understanding of the electronic factors underlying molecular association, structural stability, and reactivity.

Figure 11. (A) NCI analysis of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 displayed in lateral and axial views, illustrating the spatial distribution of non-covalent interactions. (B) Corresponding RDG scatter plot highlighting the interaction regions within the compound (C7H11N2)H2PO4.

The figure includes a scatter plot of RDG values plotted against sign(λ2)ρ, where ρ denotes the electron density and λ2 is the second eigenvalue of the electron density Hessian matrix. This representation offers a topological and energetic characterization of the observed interactions. The RDG values, shown on the y-axis, tend toward zero in regions of significant interactions and increase in regions with minimal or no interaction. The x-axis, sign(λ2)ρ, distinguishes attractive interactions (negative values) from repulsive ones (positive values), while the electron density magnitude reflects the strength of the interaction. A color gradient overlays the plot to visually reinforce the classification of different interaction types based on their electronic signatures.

The distribution of points reveals three main interaction regimes. On the left side, strong attractive interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and halogen bonding, form a dense cluster characterized by highly negative sign(λ2)ρ values and low RDG. The central region, where sign(λ2)ρ values approach zero, corresponds to weak dispersive forces, including van der Waals interactions. On the right, positive sign(λ2)ρ values and low RDG indicate strong repulsive interactions, typically resulting from steric hindrance.

In this analysis, steric repulsions appeared to occupy a relatively small portion of the scatter plot. In contrast, strong attractive interactions such as hydrogen bonding, specifically NH···O and OH···H contacts, were clearly identified by the prominent green-blue and blue RDG isosurfaces. Additionally, a broad green isosurface, indicative of van der Waals interactions, was observed between the two cationic unit [C7H11N2]+ and the anion [H2PO4]-. This spatial feature supports previous computational findings and aligns well with the experimental data, reinforcing the structural relevance of these non-covalent contacts.

4 Conclusion

In this study, we synthesized a novel organoammonium–dihydrogenphosphate hybrid compound, (C7H11N2)H2PO4. They were characterized by X-ray diffraction. The results of IR spectroscopy confirm the molecular structure of the studied compound and were found to be in good agreement with X-ray diffraction observations.

The structural and electronic investigations of (C7H11N2)H2PO4 provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors governing its crystal stability and molecular behavior. Hirshfeld surface analysis revealed that nitrogen-mediated hydrogen bonding plays a central role in the crystal architecture, establishing a directional network that forms the backbone of the supramolecular assembly. Additionally, strong O–H···O interactions involving the phosphate oxygen atoms significantly reinforce lattice cohesion. The presence of π–π stacking and van der Waals forces further contributes to an efficient and orderly molecular packing.

Complementary insights from molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) mapping highlighted distinct zones of negative potential over the phosphate group, identifying key sites for nucleophilic interactions and hydrogen bond formation, while the organic cation exhibited a more delocalized, slightly positive surface. Electron Localization Function (ELF) and Localized Orbital Locator (LOL) analyses confirmed the presence of highly localized electron basins along covalent bonds and lone pairs, particularly around the nitrogen atoms, with moderate delocalization across the aromatic system contributing to overall electronic stability. Using the RDG and NCI approaches, we identified strong NH···O and OH···H hydrogen bonds, along with notable van der Waals interactions between the cationic units and the phosphate anion, confirming the key role of non-covalent forces in stabilizing the crystal structure.

Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis demonstrated that both the HOMO and LUMO are primarily localized on the organic cation, with a significant HOMO–LUMO energy gap (5.538 eV) indicating considerable kinetic stability and limited intrinsic reactivity under ambient conditions.

Collectively, the synergy between directional hydrogen bonding, electrostatic complementarity, covalent bonding topology, and electronic delocalization elucidates the fundamental interactions responsible for the compound’s solid-state integrity and its stable, well-ordered crystal structure.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

LG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. KZ: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. NA: Investigation, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. HK: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. BG: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. MB: Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2025-2222-02”. The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R11), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2025.1701702/full#supplementary-material

References

Averbuch-pouchot, M. T., and Durif, A. (1987). Structures of ethylenediammonium monohydrogentetraoxophosphate (V) and ethylenediammonium monohydrogentetraoxoarsenate (V). Acta Cryst. C43, 1894–1896. doi:10.1107/S0108270187089716

Averbuch-Pouchot, M. T., Durif, A., and Guitel, J. C. (1988). Structures of glycine monophosphate and glycine cyclo-triphosphate. Acta Cryst. C44, 99–102. doi:10.1107/S0108270187008539

Averbuch-pouchot, M. T., Durif, A., and Guitel, J. C. (1989). Structure of ethylenediammonium dihydrogentetraoxophosphate (V) pentahydrogenbis [tetraoxophosphate (V)]. Acta Cryst. C45, 421. doi:10.1107/S0108270188011977

Bagieu-Beucher, M., and Masse, R. (1991). Structure of 4-aminopyridinium dihydrogentetraoxophosphate (V) monohydrate. Acta Cryst. C47, 1642–1645. doi:10.1107/S0108270191001518

Bagieu-Beucher, M. (1990). Structure of cytosinium dihydrogenmonophosphate. Acta Cryst. C46, 238–240. doi:10.1107/S0108270189006177

Balachandran, V., Rajeswari, S., and Lalitha, S. (2014). Thermal and magnetic properties and vibrational analysis of 4-(dimethylamino) pyridine: a quantum chemical approach. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 124, 277–284. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2014.01.023

Balamurugan, P., Jagan, R., and Sivakumar, K. (2010). Dihydrogen phosphate mediated supramolecular frameworks in 2- and 4-chloroanilinium dihydrogen phosphate salts. Acta Crystallogr. C66 (3), o109–o113. doi:10.1107/S0108270110001940

Baouab, L., and Jouini, A. (1998). Crystal structures and thermal behavior of two new organic monophosphates. J. Solid State Chem. 141, 343–351. doi:10.1006/jssc.1998.7933

Belghith, S., Bahrouni, Y., and Ben Hamada, L. (2015). Synthesis, crystal structure and characterization of a new dihydrogenomonophosphate: (C7H9N2O)H2PO4. Open J. Inorg. Chem. 05 (04), 122–130. doi:10.4236/ojic.2015.54013

Ben Hamada, L., and Jouini, A. (2006). Experimental and theoretical study of hybrid dihydrogen phosphate system: insights into bulk growth, chemical etching, non-linear optical properties, and antimicrobial activity. J. Mater. Res. Bull. 41, 1917–1924. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3921223/v1

Blessing, R. H. (1986). Hydrogen bonding and thermal vibrations in crystalline phosphate salts of histidine and imidazole. Acta Cryst. B42, 613–621. doi:10.1107/S0108768186097641

Brown, I. D. (1976). On the geometry of O–H⋯ O hydrogen bonds. Acta Crystallogr. A32, 24–31. doi:10.1107/S0567739476000041

Budzikur, D., Kinzhybalo, V., and Ślepokura, K. (2022). Crystal engineering and structural diversity of 2-aminopyridinium hypodiphosphates obtained by crystallization and dehydration. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 24 (24), 4417–4429. doi:10.1039/d2ce00261b

Das, R., Pathak, N., Choudhury, S., Borah, S., and Mahanta, S. P. (2017). Dihydrogenphosphate recognition: assistance from the acidic OH moiety of the anion. J. Mol. Struct. 1148, 81–88. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.07.029

Eaoud, Z., Kamoun, S., Mhiri, T., and Jaud, J. (1999). Crystal structure of triethylentetraammonium bis monohydrogenmonophosphate dihydrate, [NH3(CH2)2NH2(CH2)2NH2(CH2)2NH3] (HPO4)2 .2H2O. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 29 (5), 541–545. doi:10.1023/a:1009588517216

Farrugia, L. J. (1997). ORTEP-3 for Windows-a version of ORTEP-III with a graphical user interface (GUI). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 565. doi:10.1107/S0021889897003117

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2009). Gaussian 09, Revis. C.01.

Fujita, K., MacFarlane, D. R., Noguchi, K., and Ohno, H. (2009). Tetramethylammonium dihydrogen phosphate hemihydrate. Acta Crystallogr. E65 (4), 797. doi:10.1107/S1600536809009179

Gani, D., and Wilkic, J. (1955). Crystal structure of a new organic dihydrogenomonophosphate (C6H8N3O)2(H2PO4)2, chem. Sos. Rev. 24, 55. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2006.03.005

Gassoumi, B., Ahmed Mahmoud, A. M., Nasr, S., Karayel, A., Özkınalı, S., Castro, M. E., et al. (2023). Revealing the effect of Co/Cu (d7/d9) cationic doping on an electronic acceptor ZnO nanocage surface for the adsorption of citric acid, vinyl alcohol, and sulfamethoxazole ligands: DFT-D3, QTAIM, IGM-NCI, and MD analysis. Mater. Chem. Phys. 309, 128364. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.128364

Guelmami, L., Gharbi, A., and Jouini, A. (2012). 4-Dimethylaminopyridinium dihydrogenmonophosphate (C7H11N2)H2PO4: synthesis, structural, 31P, 13C NMR and thermal investigations. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 42, 549–554. doi:10.1007/s10870-012-0277-x

Guelmami, L., Hajji, M., and Guerfel, T. (2023). Structural, physico-chemical analyses, hirshfeld surface, and DFT calculations of a mixed phosphate-based compound templated by 4-dimethylaminopyridine (C7H11N2)2H2P2O7.H3PO4. J. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 763 (1), 28–46. doi:10.1080/15421406.2023.2194570

Haile, S. M., Calkins, P. M., and Boysen, D. (1998). Structure and vibrational spectrum of β-Cs3(HSO4)2[H2−x(P1−x, Sx)O4] (X∼0.5), a new superprotonic conductor, and a comparison withα-Cs3(HSO4)2(H2PO4). J. Solid State Chem. 139, 373–387. doi:10.1006/jssc.1998.7861

Hirshfeld, F. L. (1977). Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theor. Chim. Acta 44, 129–138. doi:10.1007/bf00549096

Jacobsen, H. (2008). Localized-orbital locator (LOL) profiles of chemical bonding. Can. J. Chem. 86, 695–702. doi:10.1139/v08-052

Kaabi, K., Rayes, A., Ben Nasr, C., Rzaigui, M., and Lefebvre, F. (2003). Synthesis and crystal sructure of a new dihydrogenomonophosphate (4-C2H5C6H4NH3)H2PO4. Mater. Res. Bull. 38 (5), 741–747. doi:10.1016/S0025-5408(03)00072-2

Kamoun, S., and Jouini, A. (1990). Etude calorimétrique et structure cristalline du putrescinium monohydrogénomonophosphate dihydrate NH3(CH2)4NH3HPO42H2O. J. Solid State Chem. 89, 67–74. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(90)90294-8

Kamoun, S., Jouini, A., and Daoud, A. (1990). Bis (N, N, N', N'-tetramethylethylenediammonium) cyclotetraphosphate tetrahydrate. Acta Cryst. C4, 1481. doi:10.1107/S0108270196012139

Kamoun, S., Jouini, A., and Daoud, A. (1991). Structure du propanediammonium-1,3 monohydrogénomonophosphate monohydrate. Acta Cryst. C47, 117. doi:10.1107/S0108270190003122

Kamoun, S., Daoud, A., Elfakir, A., Quarton, M., and Ledoux, I. (1995). Linear and nonlinear optical properties of N-diethylendiammonium monohydrogenmonophosphate dihydrate. Solid State Commun. 94, 893–897. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(95)00184-0

Lu, T., and Chen, F. (2012). Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592. doi:10.1002/jcc.22885

Mahé, N., Nicolaï, B., Allouchi, H., Barrio, M., Do, B., Céolin, R., et al. (2013). Crystal structure and solid-state properties of 3, 4-diaminopyridine dihydrogen phosphate and their comparison with other diaminopyridine salts. Cryst. Growth Des. 13 (2), 708–715. doi:10.1021/cg3014249

Mass, R., Bagieu-Bleucher, M., Pecaul, J., Levy, J. P., and Zyss, J. (1993). Design of organic–inorganic polar crystals for quadratic nonlinear optics. Nonlinear Opt. 5, 413.

Medimagh, M., Issaoui, N., Gatfaoui, S., Kazachenko, A. S., Al-Dossary, O. M., Kumar, N., et al. (2023). Investigations on the non-covalent interactions, drug-likeness, molecular docking and chemical properties of 1,1,4,7,7- pentamethyldiethylenetriammonium trinitrate by density-functional theory. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 35 (4), 102645. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2023.102645

Montchamp, J. L. (2014). Phosphinate chemistry in the 21st century: aviable alternative to the use of phosphorus trichloride in organophosphorus synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1, 77–87. doi:10.1021/ar400071v

Mrad, M. L., Ammar, S., Ferretti, V., Rzaigui, M., and Ben Nasr, C. (2011). Synthesis, crystal structure and characterization of a new Octane-1, 8-diammonium bis (dihydrogenmonophosphate). Open J. Inorg. Chem. 01 (01), 1–8. doi:10.4236/ojic.2011.11001

Nakamoto, K. (1986). IR and Ra spectra of inorganic and coordinated compounds. New York: Wiley- Interscience.

Olivier, S., Kuparman, A., Coombs, N., Lough, A., and Ozin, G. A. (1995). Lamellar aluminophosphates with surface patterns that mimic diatom and Radiolarian microskeletons. Nature 378, 47–50. doi:10.1038/378047a0

Oueslati, A., Ben Nasr, C., Durif, A., and Lefebvre, F. (2005). Synthesis and characterization of a new organic dihydrogen phosphate–arsenate: [H2(C4H10N2)] [H2(As, P)O4]2. Mater. Res. Bull. 40, 970–980. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2005.02.017

Pandian, T. S., Choi, Y., Srinivasadesikan, V., Lin, M. C., and Kang, J. (2015). A dihydrogen phosphate selective anion receptor based on acylhydrazone and pyrazole. New J. Chem. 39 (1), 650–658. doi:10.1039/C4NJ01063A

Rayes, A., Dadi, A., Mahbouli Rhouma, N., Mezzadri, F., and Calestani, G. (2016). Synthesis and crystal structure of 4-fluorobenzylammonium dihydrogen phosphate, [FC6H4CH2NH3]H2PO4. Acta Crystallogr. E72 (12), 1812–1815. doi:10.1107/S2056989016018090

Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. A64, 3–8. doi:10.1107/S2053229614024218

Singh, S., Das, G., Singh, O. V., and Han, H. (2007). Development of more potent 4-dimethylaminopyridine analogues. Org. Lett. 9 (3), 401–404. doi:10.1021/ol062712l

Spackman, M. A., and Jayatilaka, D. (2009). Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm J. 11, 19–32. doi:10.1039/B818330A

Spackman, M. A., and McKinnon, J. J. (2002). Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. CrystEngComm J. 4, 378–392. doi:10.1039/b203191b

Spackman, P. R., Turner, M. J., McKinnon, J. J., Wolff, S. K., Grimwood, D. J., Jayatilaka, D., et al. (2021). CrystalExplorer: a program for hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals. Cryst. Explor. 3.1, 1006–1011. doi:10.1107/S1600576721002910

Steiner, Th., and Saenger, W. (1994). Lengthening of the covalent O–H bond in O–H⋯ O hydrogen bonds re-examined from low-temperature neutron diffraction data of organic compounds. Acta Crystallogr. B50, 348–357. doi:10.1107/S0108768193011966

Vratislav, L., Huml, K., and Zachov´a, J. (1979). The crystal and molecular structure of adeninium phosphate, C5H6N5+.-H2PO4. Acta Cryst. B35, 1148. doi:10.1107/S0567740879005768

Wang, J. T., Savinell, R. F., Wainright, J., Litt, M., and Yu, M. (1996). A fuel cell using acid doped polybenzimidazole as polymer electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 41, 193–197. doi:10.1016/0013-4686(95)00313-4

Yuichi, K., Takayoshi, K., Koichi, K., and Kagaku Kaishi, N. (1995). “Syntheses and polymerization of unsaturated dibasic acid derivatives,”Soc. Polym. Sci. 12. 971. doi:10.1295/koron1944.23.348

Zaki, K., Ouabane, M., Guendouzi, A., Sbai, A., Sekkate, C., Bouachrine, M., et al. (2024). From farm to pharma: investigation of the therapeutic potential of the dietary plants Apium graveolens L., Coriandrum sativum, and Mentha longifolia, as AhR modulators for immunotherapy. Comput. Biol. Med. 181, 109051. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2024.109051

Keywords: dimethylaminopyridinium dihydrogenmonophosphate, IR spectroscopy, DFT calculations, Hirshfeld surfaces analysis, molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) calculation, electron localization function (ELF), localized orbital locator (LOL) analysis

Citation: Guelmami L, Dhifet M, Zaki K, Alwadai N, Khmissi H, Bouzidi M, Gassoumi B and Bouachrine M (2025) Synthesis, structural characterization, spectroscopic analyses, DFT-modeling, and RDG-NCI assessment of 4-dimethylaminopyridinium dihydrogen monophosphate. Front. Chem. 13:1701702. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2025.1701702

Received: 10 September 2025; Accepted: 20 October 2025;

Published: 17 November 2025.

Edited by:

Renjith Thomas, Mahatma Gandhi University, IndiaReviewed by:

Konda Reddy Karnati, Bowie State University, United StatesJacek E. Nycz, University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland

Copyright © 2025 Guelmami, Dhifet, Zaki, Alwadai, Khmissi, Bouzidi, Gassoumi and Bouachrine. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mondher Dhifet, bW9uZGhlcmRoaWZldF8yMDA1QHlhaG9vLmZy; Bouzid Gassoumi, Z2Fzc291bWlib3V6aWQyMDE2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Lelfia Guelmami1,2

Lelfia Guelmami1,2 Mondher Dhifet

Mondher Dhifet Bouzid Gassoumi

Bouzid Gassoumi Mohammed Bouachrine

Mohammed Bouachrine