Abstract

Janus transition-metal dichalcogenide (TMD) heterostructures offer unique opportunities for coupling mechanical flexibility with catalytic functionality. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that in-plane SMoSe–XS2 (X = Mo, W) heterostructures spontaneously form sinusoidal superlattices driven by interfacial asymmetry, exhibiting over fivefold enhancement in fracture strain and pronounced size-dependent strength. The periodic profile of Armchair and Zigzag configurations highlights the intrinsic link between structure and mechanical response. Density functional theory calculations further demonstrate that the wrinkled interfaces significantly improve hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity, with Gibbs free energies as low as −0.18 eV, resulting from the upward shift of the Se and S p-band centers near the Fermi level, facilitating optimal H adsorption. This work establishes Janus TMD heterostructure superlattices as promising candidates for multifunctional applications integrating mechanical adaptability and catalytic efficiency.

1 Introduction

In recent years, two-dimensional (2D) materials have been intensively investigated, largely inspired by graphene, which exhibits remarkable physical characteristics (Geim and Novoselov, 2007). The presence of a Dirac cone in graphene enables ultrafast charge transport (Stoller et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2015), however, the zero bandgap significantly limits practical uses, particularly in field-effect transistors (Novoselov et al., 2016). To overcome this drawback, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) have emerged as attractive candidates due to their high carrier mobility (Li et al., 2018). More importantly, their finite bandgaps provide access to diverse functionalities, including photocatalytic water splitting (Liang et al., 2019; Radisavljevic et al., 2011). A notable example is the Janus SMoSe monolayer, synthesized to demonstrate out-of-plane piezoelectricity arising from broken symmetry, with strong potential for spintronic devices (Liu et al., 2016). Thermal transport studies revealed that SMoSe and WS2 possess conductivities of approximately 51.27 W·m–1·K−1 and 47.90 W·m–1·K−1, respectively, both displaying distinct temperature dependence (Qin et al., 2022). Furthermore, SMoSe shows versatility in photocatalysis (Ren et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2025a), nanoelectronics (Ren et al., 2025b), and energy-conversion technologies (Luo et al., 2025). Beyond these, novel magnetic responses and unusual thermal behaviors have also been uncovered in a broader range of 2D systems (Lia et al., 2017; Torun et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2020).

For 2D materials, the effective strength relevant for engineering applications is determined primarily by fracture toughness rather than by the intrinsic bond strength of atoms (Ren et al., 2025c; Ren et al., 2025d). Graphene, for instance, exhibits brittle failure, with a measured fracture toughness close to 4.0 MPa (Cadelano et al., 2010). Interestingly, some layered systems display a negative Poisson’s ratio, such as δ-SiSe (−0.29) (Ren et al., 2022a), Li2B12 (−0.03) (Ren et al., 2022b), B4N (−0.02) (Wang et al., 2019), and δ-CS (−0.19) (Sun and Schwingenschlögl, 2020), which originates from their unique lattice geometry. These auxetic structures hold potential in advanced composites and aerospace technology. Moreover, many 2D systems show remarkable strain-tunable thermal and electronic responses (Huang L. et al., 2025; Huang W. et al., 2025; Ren and Sun, 2025). To broaden their functions, researchers have developed heterostructures. Van der Walls stacks with type-II band alignment, for example, enable efficient charge separation and extend carrier lifetime (Yan et al., 2020). In contrast, in-plane heterostructures rely on covalent connections. A notable case is the MoS2/WSe2 lateral junction, which was recently fabricated (Chiu et al., 2015). Its fracture resistance can be adjusted by the interface design, thermal environment, or preexisting cracks (Ren et al., 2023a). Similarly, Janus SMoSe/WS2 in-plane hybrids have been synthesized (Trivedi et al., 2020), showing intrinsic thermo-mechanical coupling at the interface (Ren et al., 2022c). Even more, ordered lateral superlattices have been experimentally realized, such as WSe2/WS2 (Wu et al., 2019), exhibiting diode-like transport with rectification ratios up to 105. These artificial lattices have attracted widespread interest due to emergent phenomena including mini-Dirac cones (Li et al., 2015), Mott insulating states (Zhao and Schwingenschlögl, 2021), reduced lattice thermal conductivity (Yin et al., 2021) and moiré exciton bands (Torun et al., 2018). Specifically, the Janus SMoSe/WS2 superlattice band alignment can switch from type-I to type-II depending on intrinsic structural parameters, making it suitable for photocatalytic water splitting (Zhang et al., 2023). Its electronic states can also be tuned effectively by external strain or electric fields (Shu et al., 2025). Despite these advances, the mechanical consequences of lateral superlattice architectures remain insufficiently explored. In particular, the intrinsic interfacial bending in Janus SMoSe/WS2 heterostructures largely determines their strength and could provide valuable guidelines for device design. Yet, the bending behavior itself has not been systematically investigated.

In this study, we predict that the in-plane Janus SMoSe–XS2 (X = W, Mo) heterostructure superlattice remains stable, exhibiting a nearly sinusoidal configuration arising from a well-matched interface. Furthermore, its adjustable mechanical responses are examined through molecular dynamics simulations by varying the dimensions of the SMoSe and XS2 domains, revealing an exceptionally stretchable nature.

2 Geometric structure and computational methods

In this study, molecular dynamics calculations were performed using the Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) (Plimpton, 1995). Atomic configurations were visualized through the OVITO software package (Stukowski, 2009). The in-plane SMoSe–WS2 heterostructure was modeled with the Stillinger–Weber (SW) potential formulated by Jiang, which has been widely applied to transition metal dichalcogenides due to its reliable description of structural and elastic behavior (Jiang, 2018; Jiang et al., 2013). The Stillinger–Weber (SW) potential was parameterized using a valence force field (VFF) framework (Jiang, 2015). Previous studies have demonstrated that both the VFF and SW models can accurately reproduce the experimentally measured phonon spectrum of MoS2 (Wakabayashi et al., 1975). Therefore, the molecular dynamics simulations employed in this work, which are based on the SW potential, are regarded as reliable. Besides, the stress–strain response and Young’s modulus of MoS2 derived from this potential agree well with experimental measurements (Bertola et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2013), confirming its suitability for mechanical investigations of these layered crystals.

The SMoSe–XS2 lateral superlattice was designed as illustrated in Figure 1a, where the number of SMoSe and XS2 segments is determined by the parameter N. Periodic boundary conditions were imposed along the x, y, and z directions. The characteristic lengths of the SMoSe, XS2, and heterostructure domains were denoted as L1, L2, and L0, respectively. Different heterostructure configurations were considered, as shown in Figures 1b–e: armchair SMoSe/MoS2 (A1), armchair SMoSe/WS2 (A2), zigzig SMoSe/MoS2 (Z1), and zigzig SMoSe/WS2 (Z2). Recent experiments have demonstrated the successful synthesis of lateral MoSSe/WSSe heterostructures featuring zigzag interfaces via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) (Trivedi et al., 2020). In that work, triangular MoSe2 monolayers were first grown, followed by epitaxial growth of WSe2 from the one-dimensional edges of the MoSe2 domains. Although MoSSe/WSSe heterostructures with armchair interfaces have not yet been experimentally realized, previous studies have shown that the orientation of 2D material domains–zigzag or armchair–can be precisely controlled through growth–etching–regrowth strategies in CVD processes (Huang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2018). These advances suggest that catalytic applications based on MoSSe/WSSe heterostructures are likely to become experimentally accessible in the near future. First, the SMoSe–XS2 system was optimized at 300 K for 10 ps using the NPT ensemble (isothermal–isobaric conditions). Subsequently, the system was equilibrated for 2,000 ps under the NVT ensemble with a Nosé–Hoover thermostat. Finally, a 2000 ps relaxation was performed using the NVE ensemble (constant volume and energy). During this stage, both the total energy and temperature exhibited stable fluctuations, confirming that the system had reached equilibrium. The effective layer thickness of the system was set to 0.61 nm (Jiang et al., 2013).

FIGURE 1

(a) Schematic illustration of the in-plane Janus SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice, assembled with four interface configurations: (b) A1, (c) A2, (d) Z1, and (e) Z2. The spheres in blue, pink, grey and yellow denote Mo, Se, W and S atoms, respectively.

For the mechanical assessment, uniaxial stretching was applied at a strain rate of 2 × 108 s–1 in a specified direction, implemented through the fix/deform command in LAMMPS (Plimpton, 1995). The system temperature was maintained at 300 K, and zero pressure was applied along the y-axis during tensile deformation. To investigate the mechanical behavior of the SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice, the normal stress was tracked throughout the simulations. The atomic virial stress of Se, S, Mo, and W atoms is determined by Equation 1

Here, , mi and vi are the volume correspond to the mass, velocity vector, and spatial volume of atom i, respectively. The interatomic force exerted by atom j on atom i is denoted as Fij, and the distance between these atoms is rij. The symmetric stress tensor (σi) consists of components σxx, σyy, σzz, σxz, σxy and σyz; however, for a two-dimensional system, σxz, σyz and σzz are negligible. Additionally, each atom’s volume is calculated as the initial relaxed system volume divided by the total atom count.

As for simulations of Gibbs free energy, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP). The projector augmented-wave (PAW) method was applied to describe the interaction between core and valence electrons. Exchange–correlation effects were treated within the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) framework, employing the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional. To account for long-range van der Waals interactions, Grimme’s DFT-D3 correction was included. The plane-wave cut-off energy was set to 550 eV, and a 15 × 15 × 1 Monkhorst–Pack k-point mesh was used to sample the Brillouin zone. A vacuum layer of 25 Å was introduced to prevent spurious interactions between periodic images and the total energy convergence threshold was set to 10−5 eV.

3 Results and discussion

The optimized lattice parameters of SMoSe, WS2 and MoS2 monolayers are 3.228 Å, 3.175 Å and 3.180 Å, respectively, as determined in our earlier study through first-principles calculations (Ren et al., 2022c). The lattice mismatch (ϕ) at the SMoSe–WS2 and SMoSe–MoS2 interface is approximately 1.6% and 0.15%, respectively, which is obtained as Equation 2:where aSMoSe and aXS2 demonstrate the lattice parameters of the SMoSe and XS2 monolayers. Then, we further calculated the binding energy (Eb) of the A1, A2, Z1, and Z2 stacking SMoSe–WS2 and SMoSe–MoS2 interface by Equation 3:where ESMoSe, EXS2 and ESMoSe–XS2 represent the energy of the SMoSe, XS2 and SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure, respectively. Then, the binding energy A1, A2, Z1 and Z2 configuration is calculated as −0.24 eV·Å–1, –0.18 eV·Å–1, –0.21 eV·Å–1 and –0.26 eV·Å–1, respectively, which is lower than that of the reported graphene/biphenylene interface (about −0.14 eV·Å–1) (Ren et al., 2022d). The obtained binding energy also demonstrates the stability of the studied SMoSe–XS2 (X = W, Mo) system.

Based on this, we constructed self-assembled superlattices with A1, A2, Z1, and Z2 stacking configurations. For the A1 and A2 models, the starting length and width are 620.168 Å and 51.265 Å, respectively. In contrast, the Z1 and Z2 configurations possess initial dimensions of 716.328 Å in length and 52.397 Å in width. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed along the x, y, and z-axes. In the present study, the overall dimensions of the SMoSe–WS2 superlattice are kept constant, while the lengths of the SMoSe and WS2 regions are treated as adjustable parameters.

Firstly, we examine how the length ratio L1/L2 influences the optimized geometry. After full relaxation, the equilibrium structures of the A1 and A2 SMoSe–WS2 superlattice under varying L1/L2 are displayed in Figure 2. The A1 configuration remains nearly flat, maintaining a smooth monolayer surface, as illustrated in Figures 2a,c,e,g,i. In contrast, the A2 arrangement exhibits periodic folding driven by interfacial curvature, as depicted in Figures 2b,d,f,h,j. Notably, when Lm/Ln approaches unity, the A2 phase evolves into a highly ordered sinusoidal sheet, as shown in Figure 2j. Such an intrinsic morphology differs fundamentally from previously reported wrinkled or folded monolayers induced by external mechanical strain (Li et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2012). A similar effect is observed in the heterostructure superlattice formed with a zigzag interface.

FIGURE 2

The optimized configurations are illustrated in both top and side views: (a,c,e,g,i) correspond to the A1 heterostructure, while (b,d,f,h,j) represent the A2 heterostructure. The ratios of L1 to L2 are set as (a,b) 1/9, (c,d) 2/8, (e,f) 3/7, (g,h) 4/6, and (i,j) 5/5, respectively.

Inspired by the intriguing spontaneous bending observed in the SMoSe–XS2 superlattice, we investigated the quantitative features of its trajectory. To examine the tunable characteristics of this system, the lengths of the SMoSe and XS2 segments were constrained such that L = L1 = L2, as illustrated in Figure 1. The number of periods N was chosen as 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64, corresponding to lengths of 16.53 nm, 8.47 nm, 4.29 nm, 2.86 nm, and 1.87 nm, respectively, in both A1 and A2 superlattices. For the Z1 and Z2 configurations, the lengths are 18.89 nm, 9.35 nm, 5.45 nm, 3.25 nm, and 2.24 nm, respectively. The atomic coordinates along the z-axis were extracted and averaged, with the intermediate positions taken as zero. This allowed us to construct the trajectory of the superlattice. Curve fitting revealed that the side-view profiles of the relaxed structures conform remarkably well to a Fourier form. The fitted Fourier expressions for the armchair and zigzag SMoSe–XS2 superlattices with varying L are displayed in Figure 3a.

FIGURE 3

(a) The Fourier-fitted profile of the structural evolution in the SMoSe–WS2 superlattice and (b) the corresponding amplitude plotted as a function of L.

As shown in Figure 3b, the amplitude of the sinusoidal bending increases with larger L. This trend arises because each SMoSe or XS2 segment is subject to opposing intrinsic stresses on its boundaries. When the segment length L1 (or L2) is too short, the section resists bending, thereby reducing the wave amplitude. Additionally, the trajectory functions in Figure 3a can be represented as y = asin(bx) + ccos(dx) + e, and the corresponding fitting parameters are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| | a | b | c | d | e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2 L = 16.53 | 0.78 | 0.35 | −4.45 | 0.36 | 0.085 |

| A2 L = 8.47 | 0.92 | 0.56 | −0.85 | 0.56 | 0.063 |

| Z2 L = 18.89 | −4.35 | 0.33 | −4.52 | 0.38 | −0.021 |

| Z2 L = 9.35 | 0.87 | 0.42 | −1.45 | 0.42 | −0.018 |

The extracted values describing the motion functions of the SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice.

The fracture response of SMoSe and XS2 monolayers was evaluated. Under uniaxial loading along the armchair orientation, SMoSe fails at a strain of 0.125 with a breaking stress of 13.31 GPa, whereas MoS2 (or WS2) reaches 0.140 (or 0.151) strain and 19.85 GPa or (20.11 GPa) stress. When stretched in the zigzag orientation, SMoSe ruptures at 0.140 strain with 12.36 GPa stress, while MoS2 (or WS2) endures up to 0.130 (or 0.145) strain and 17.06 GPa MoS2 (or 18.56 GPa) stress. These results clearly show that XS2 exhibits superior strength compared with SMoSe. Consequently, in the SMoSe–XS2 superlattice, the earliest cracks form within the SMoSe domain, as illustrated in Figure 4. Figures 4a–d show the crack nucleation for heterostructures with A1, A2, Z1, and Z2 interfaces. Moreover, tensile loading along the zigzag axis produces greater atomic stress and initiates longer cracks. In addition, compared with A1 (or Z1) stacking, the A2 (or Z2) configuration demands higher critical stress before fracture occurs.

FIGURE 4

The crack nucleation of SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice with (a,c) A1 and (b,d) A2 interfaces. L is 16.53 nm and 18.89 nm, respectively, in (a,b) and (b,d).

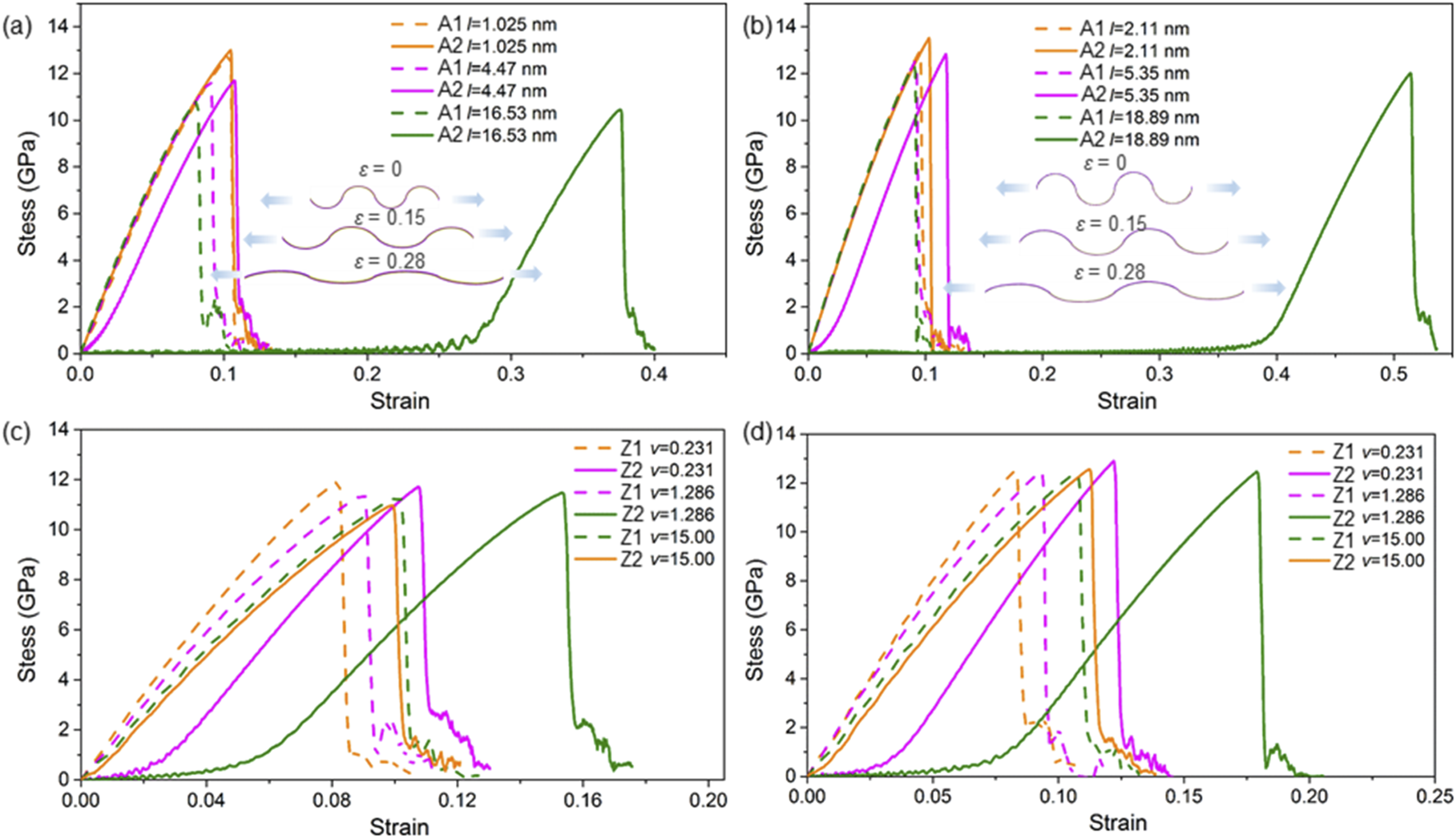

To explore the strain–stress characteristics of the SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice, we analyzed how the armchair and zigzag configurations respond under external uniaxial strain. The nonlinear elastic behavior is illustrated in Figure 5. Notably, the fracture strength of the A1 (or Z1) and A2 (or Z2) SMoSe–XS2 superlattices is similar when L equals 1.02 nm (or 1.25 nm). In contrast, the tensile failure process of the A2 and Z2 configurations is significantly extended, as depicted in Figures 5a,b. Prior to reaching strains of 0.29 and 0.41, respectively, the stress levels in these structures remain comparatively low. This behavior arises because the relaxed state of A2 and Z2 superlattices adopts a bent geometry, which must be flattened before catastrophic fracture occurs, as shown as insets of Figures 5a,b. Additionally, the fracture stress of the SMoSe–XS2 heterostructures exceeds that of the MoS2/WS2 system (12.01 GPa along the zigzag direction and 12.68 GPa along the armchair direction) for N = 4 (Qin et al., 2019). Furthermore, the fracture strain for N = 4 is significantly higher than that of the MoS2/WS2 heterostructure (10% along the zigzag direction and 9.8% along the armchair direction). In addition, the stress–strain behavior of the A1 heterostructure superlattice with L = 1.14 nm was evaluated using DFT. Besides, the stress–strain behavior of the Z1 and Z2 heterostructure superlattice with different L1/L2 is also calculated as Figures 5c,d, which still presents the enhanced mechanical properties of SMoSe components. It is worth noting that the enhanced fracture strain also larger than that of investigated MoSSe/WSSe heterostructure (about 0.32) (Ren et al., 2023a), Si-Ge heterostructure (about 0.30) (Zhao et al., 2024), SiC grain boundaries (about 0.34) (Ren et al., 2023b).

FIGURE 5

The stress–strain responses of the SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure superlattice are shown for (a,c) armchair and (b,d) zigzag interfaces with varying (a,b) lengths L and (c,d) ratio of L1/L2; the inset shows the side-view schematic illustrating the structural evolution of the A2 heterostructure under uniaxial tension.

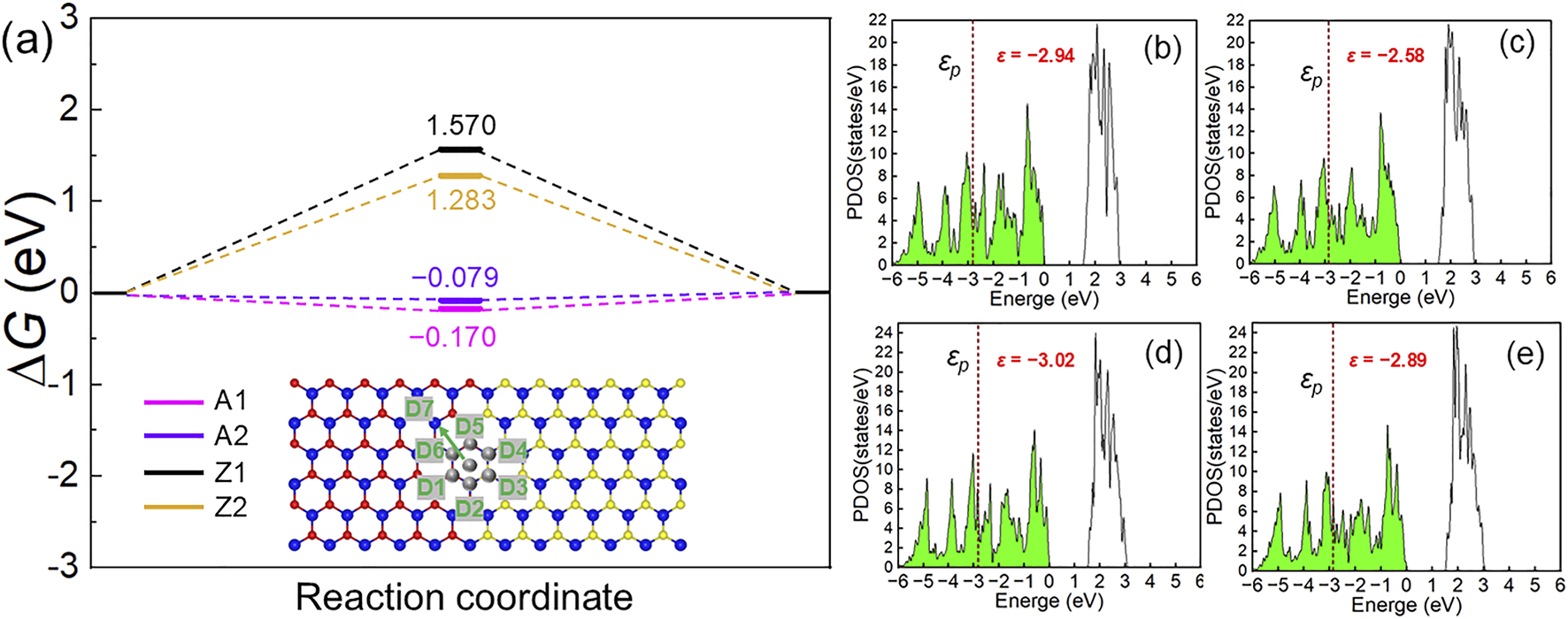

Beyond the obtained mechanical robustness, these SMoSe–XS2 heterostructures also exhibit intriguing electronic characteristics that may influence their catalytic behavior. Therefore, to further explore their functional potential, we investigated their hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity. The symmetric regions (D1–D7, shown as inset of Figure 6a) near the interface were examined to identify the most active sites. The most favorable H* adsorption occurs at D7 in the A1, A2, Z1 and Z2 configurations, decided by the lowest binding energies as −0.45 eV, −0.31 eV, 2.10 eV and 1.71 eV, respectively, which is calculated by Equation 4:where EH+SMoSe–XS2, ESMoSe–XS2 and EH represent the total energy of the H absorbed SMoSe–XS2 system, pure SMoSe–XS2 and H, respectively.

FIGURE 6

The calculated Gibbs free energy of (a) SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure interface; the projected p-orbital density of states of S or Se atoms for H adsorption sites of (b) A1, (B) A2, (B) Z1 and (B) Z2 SMoSe–XS2 heterostructures.

The calculated Gibbs free energies (ΔG) for HER are −0.170, −0.079, 1570 and 1.283 eV for the A1, A2, Z1 and Z2 configurations, respectively. One can see that the wrinkled configurations (A2 and Z2) exhibit enhanced HER activity comparing with that of flat structure (A1 and Z1). The enhanced HER catalytic activity of the reverse SMoSe–XS2 heterostructure can be further understood from the projected band center (εp) analysis. The formation of Se–H and S–H bonds is primarily governed by the p orbitals of Se and S atoms at the active sites, therefore, the position of the p orbital relative to the Fermi level is critical for H* adsorption. As shown in Figures 6b–e, the density of states (DOS) of the atoms at the active sites reveals that the –|εp| of the A2 and Z2 configurations configuration lies closer to the Fermi level than that of A1 and Z1 one, explaining the stronger H adsorption on the former structures. Thus, such wrinkled SMoSe–XS2 interface also can improve the HER activity.

4 Conclusion

In summary, this work reveals that Janus SMoSe–XS2 (X = Mo, W) heterostructures can spontaneously form sinusoidal superlattices due to interfacial asymmetry, leading to exceptional mechanical flexibility and stability. The resulting wrinkled configurations exhibit a substantial increase in fracture strain and tunable strength, governed by periodic structural modulation. Beyond mechanical robustness, the same interfacial characteristics enhance the catalytic performance for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), with the A2 interface showing nearly ideal hydrogen adsorption free energy. The improved activity originates from the optimized electronic structure and the p-band alignment of S and Se atoms near the Fermi level. These findings demonstrate that structural asymmetry in Janus TMD heterostructures can synergistically engineer both mechanical and catalytic functionalities, offering a viable strategy for designing multifunctional 2D materials.

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

JL: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. LX: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The authors thank the Research Projects of Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX3081) and the Shenzhen Polytechnic Research Fund (6023310003K).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Bertolazzi S. Brivio J. Kis A. (2011). Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2. ACS Nano5, 9703–9709. 10.1021/nn203879f

2

Cadelano E. Palla P. L. Giordano S. Colombo L. (2010). Elastic properties of hydrogenated graphene. Phys. Rev. B82, 235414. 10.1103/physrevb.82.235414

3

Chiu M. H. Zhang C. Shiu H. W. Chuu C. P. Chen C. H. Chang C. Y. et al (2015). Determination of band alignment in the single-layer MoS2/WSe2 heterojunction. Nat. Commun.6, 7666. 10.1038/ncomms8666

4

Cooper R. C. Lee C. Marianetti C. A. Wei X. Hone J. Kysar J. W. (2013). Nonlinear elastic behavior of two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide. Phys. Rev. B87, 035423. 10.1103/physrevb.87.035423

5

Geim A. K. Novoselov K. S. (2007). The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater.6, 183–191. 10.1038/nmat1849

6

Huang C. Wu S. Sanchez A. M. Peters J. J. Beanland R. Ross J. S. et al (2014). Lateral heterojunctions within monolayer MoSe2-WSe2 semiconductors. Nat. Mater.13, 1096–1101. 10.1038/nmat4064

7

Huang L. Shu H. Wang G. Mu W. Li J. Ren K. (2025a). Thermal transport characteristics of wrinkle interface in ultraflexible MoSSe-WX2 (X = S, Se) heterostructure. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces17, 57594–57602. 10.1021/acsami.5c11058

8

Huang W. Su Y. Ren K. Liu Y. Qin H. (2025b). Manipulating hydrogen evolution reaction in Janus MoSSe monolayer via defect and strain engineering. Phys. status solidi (b), 2500128. 10.1002/pssb.202500128

9

Jiang J.-W. (2015). Parametrization of Stillinger–Weber potential based on valence force field model: application to single-layer MoS2 and black phosphorus. Nanotechnology26, 315706. 10.1088/0957-4484/26/31/315706

10

Jiang J.-W. (2018). Misfit strain-induced buckling for transition-metal dichalcogenide lateral heterostructures: a molecular dynamics study. Acta Mech. Solida Sin.32, 17–28. 10.1007/s10338-018-0049-z

11

Jiang J.-W. Park H. S. Rabczuk T. (2013). Molecular dynamics simulations of single-layer molybdenum disulphide (MoS2): Stillinger-Weber parametrization, mechanical properties, and thermal conductivity. J. Appl. Phys.114, 064307. 10.1063/1.4818414

12

Li H. Contryman A. W. Qian X. Ardakani S. M. Gong Y. Wang X. et al (2015). Optoelectronic crystal of artificial atoms in strain-textured molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Commun.6, 7381. 10.1038/ncomms8381

13

Li R. Cheng Y. Huang W. (2018). Recent progress of Janus 2D transition metal chalcogenides: from theory to experiments. Small14, 1802091. 10.1002/smll.201802091

14

Liang L. Zhang J. Sumpter B. G. Tan Q.-H. Tan P.-H. Meunier V. (2017). Low-frequency shear and layer-breathing modes in Raman scattering of two-dimensional materials. ACS Nano11, 11777–11802. 10.1021/acsnano.7b06551

15

Liang S. J. Cheng B. Cui X. Miao F. (2019). Van der Waals Heterostructures for High-Performance Device Applications: challenges and Opportunities. Adv. Mater32, 1903800. 10.1002/adma.201903800

16

Liu Y. Weiss N. O. Duan X. Cheng H.-C. Huang Y. Duan X. (2016). Van der Waals heterostructures and devices. Nat. Rev. Mater.1, 16042. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.42

17

Luo Y. He W. Ren K. Zhang C. Zuo L. Shang F. et al (2025). Advancements in Janus two-dimensional materials: from basic theory to practical applications. Ceram. Int.51, 39353–39372. 10.1016/j.ceramint.2025.06.183

18

Novoselov K. S. Mishchenko A. Carvalho A. Castro Neto A. H. (2016). 2D materials and van der Waals heterostructures. Science353, 9439. 10.1126/science.aac9439

19

Plimpton S. (1995). Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys.117, 1–19. 10.1006/jcph.1995.1039

20

Qin H. Pei Q. X. Liu Y. Zhang Y. W. (2019). The mechanical and thermal properties of MoS2-WSe2 lateral heterostructures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.21, 15845–15853. 10.1039/c9cp02499a

21

Qin H. Ren K. Zhang G. Dai Y. Zhang G. (2022). Lattice thermal conductivity of Janus MoSSe and WSSe monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.24, 20437–20444. 10.1039/d2cp01692c

22

Radisavljevic B. Radenovic A. Brivio J. Giacometti V. Kis A. (2011). Single-layer MoS2 transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol.6, 147–150. 10.1038/nnano.2010.279

23

Ren K. Sun M. (2025). Thermal transport in 2D materials. J. Appl. Phys.137, 130402. 10.1063/5.0267691

24

Ren K. Wang S. Luo Y. Chou J.-P. Yu J. Tang W. et al (2020). High-efficiency photocatalyst for water splitting: a Janus MoSSe/XN (X = Ga, Al) van der Waals heterostructure. J. Phys. Phys. D. Appl. Phys.53, 185504. 10.1088/1361-6463/ab71ad

25

Ren K. Ma X. Liu X. Xu Y. Huo W. Li W. et al (2022a). Prediction of 2D IV–VI semiconductors: auxetic materials with direct bandgap and strong optical absorption. Nanoscale14, 8463–8473. 10.1039/d2nr00818a

26

Ren K. Yan Y. Zhang Z. Sun M. Schwingenschlögl U. (2022b). A family of LixBy monolayers with a wide spectrum of potential applications. Appl. Surf. Sci.604, 154317. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.154317

27

Ren K. Qin H. Liu H. Chen Y. Liu X. Zhang G. (2022c). Manipulating interfacial thermal conduction of 2D Janus heterostructure via a thermo‐mechanical coupling. Adv. Funct. Mater.32, 2110846. 10.1002/adfm.202110846

28

Ren K. Chen Y. Qin H. Feng W. Zhang G. (2022d). Graphene/biphenylene heterostructure: interfacial thermal conduction and thermal rectification. Appl. Phys. Lett.121, 082203. 10.1063/5.0100391

29

Ren K. Zhang G. Zhang L. Qin H. Zhang G. (2023a). Ultraflexible two-dimensional Janus heterostructure superlattice: a novel intrinsic wrinkled structure. Nanoscale15, 8654–8661. 10.1039/d3nr00429e

30

Ren K. Huang L. Shu H. Zhang G. Mu W. Zhang H. et al (2023b). Impacts of defects on the mechanical and thermal properties of SiC and GeC monolayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.25, 32378–32386. 10.1039/d3cp04538b

31

Ren K. Wang F. Liu T. Qin H. Jing Y. (2025a). Wrinkles in 2D TMD heterostructures: unlocking enhanced hydrogen evolution reaction catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A13, 20859–20867. 10.1039/d5ta00681c

32

Ren K. Wang K. Luo Y. Sun M. Altalhi T. Yakobson B. I. et al (2025b). Ultralow Frequency Interlayer Mode from Suppressed van der Waals Coupling in Polar Janus SMoSe/SWSe Heterostructure. Mater. Today Phys.53, 101689. 10.1016/j.mtphys.2025.101689

33

Ren K. Zhuang Z. Wang K. Wei Y. Li J. Shu H. (2025c). Machine learning speeds up predicting the mechanical properties of SiC nanophononic heterostructures. J. Phys. Chem. C192, 15462–15470. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5c04526

34

Ren K. Lv C. Wang Y. Zhang C. Wang D. (2025d). Deep learning interatomic potential for boron phosphide: accurate prediction of mechanical and thermal properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 10.1039/D5CP01433F

35

Shu H. Wang F. Ren K. Guo J. (2025). Strain-tunable optoelectronic and photocatalytic properties of 2D GaN/MoSi2P4 heterobilayers: potential optoelectronic/photocatalytic materials. Nanoscale17, 3900–3909. 10.1039/d4nr04545a

36

Song Q. An M. Chen X. Peng Z. Zang J. Yang N. (2016). Adjustable thermal resistor by reversibly folding a graphene sheet. Nanoscale8, 14943–14949. 10.1039/c6nr01992g

37

Stoller M. D. Park S. Zhu Y. An J. Ruoff R. S. (2008). Graphene-based ultracapacitors. Nano Lett.8, 3498–3502. 10.1021/nl802558y

38

Stukowski A. (2009). Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO–the Open visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng.18, 015012. 10.1088/0965-0393/18/1/015012

39

Sun M. Schwingenschlögl U. (2020). δ-CS: a direct-band-gap semiconductor combining auxeticity, ferroelasticity, and potential for high-efficiency solar cells. Phys. Rev. Appl.14, 044015. 10.1103/physrevapplied.14.044015

40

Torun E. Miranda H. P. C. Molina-Sánchez A. Wirtz L. (2018). Interlayer and intralayer excitons in MoS2/WS2 and MoSe2/WSe2 heterobilayers. Phys. Rev. B97, 245427. 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.245427

41

Torun E. Paleari F. Milosevic M. V. Wirtz L. Sevik C. (2023). Intrinsic Control of Interlayer Exciton Generation in Van der Waals Materials via Janus Layers. Nano Lett.23, 3159–3166. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c04724

42

Trivedi D. B. Turgut G. Qin Y. Sayyad M. Y. Hajra D. Howell M. et al (2020). Room-temperature synthesis of 2D Janus crystals and their heterostructures. Adv. Mater32, 2006320. 10.1002/adma.202006320

43

Wakabayashi N. Smith H. Nicklow R. (1975). Lattice dynamics of hexagonal MoS2 studied by neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B12, 659–663. 10.1103/physrevb.12.659

44

Wang J. Deng S. Liu Z. Liu Z. (2015). The rare two-dimensional materials with Dirac cones. Natl. Sci. Rev.2, 22–39. 10.1093/nsr/nwu080

45

Wang B. Wu Q. Zhang Y. Ma L. Wang J. (2019). Auxetic B4N monolayer: a promising 2D material with in-Plane negative poisson's ratio and large anisotropic mechanics. ACS Appl. Mater Interfaces11, 33231–33237. 10.1021/acsami.9b10472

46

Wu X. Wang X. Li H. Zeng Z. Zheng B. Zhang D. et al (2019). Vapor growth of WSe2/WS2 heterostructures with stacking dependent optical properties. Nano. Res.12, 3123–3128. 10.1007/s12274-019-2564-8

47

Yan Y. Zeng Z. Huang M. Chen P. (2020). Van der waals heterojunctions for catalysis. Mater. Today Adv.6, 100059. 10.1016/j.mtadv.2020.100059

48

Yang N. Ni X. Jiang J.-W. Li B. (2012). How does folding modulate thermal conductivity of graphene?Appl. Phys. Lett.100, 093107. 10.1063/1.3690871

49

Yin Y. Hu Y. Li S. Ding G. Wang S. Li D. et al (2021). Abnormal thermal conductivity enhancement in covalently bonded bilayer borophene allotrope. Nano. Res.15, 3818–3824. 10.1007/s12274-021-3921-y

50

Zhang C. Li M. Y. Tersoff J. Han Y. Su Y. Li L. J. et al (2018). Strain distributions and their influence on electronic structures of WSe2-MoS2 laterally strained heterojunctions. Nat. Nanotechnol.13, 152–158. 10.1038/s41565-017-0022-x

51

Zhang K. Guo Y. Ji Q. Lu A. Y. Su C. Wang H. et al (2020). Enhancement of van der Waals Interlayer Coupling through Polar Janus MoSSe. J. Am. Chem. Soc.142, 17499–17507. 10.1021/jacs.0c07051

52

Zhang C. Ren K. Wang S. Luo Y. Tang W. Sun M. (2023). Recent progress on two-dimensional van der Waals heterostructures for photocatalytic water splitting: a selective review. J. Phys. Phys. D. Appl. Phys.56, 483001. 10.1088/1361-6463/acf506

53

Zhao N. Schwingenschlögl U. (2021). Dipole-induced ohmic contacts between monolayer Janus MoSSe and bulk metals. Npj 2D Mater. Appl.5, 72. 10.1038/s41699-021-00253-w

54

Zhao L. Huang L. Wang K. Mu W. Wu Q. Ma Z. et al (2024). Mechanical and lattice thermal properties of Si-Ge lateral heterostructures. Molecules29, 3823. 10.3390/molecules29163823

55

Zhou J. Lin J. Huang X. Zhou Y. Chen Y. Xia J. et al (2018). A library of atomically thin metal chalcogenides. Nature556, 355–359. 10.1038/s41586-018-0008-3

Summary

Keywords

Janus transition metal dichalcogenides, in-plane heterostructure superlattice, mechanical properties, hydrogen evolution reaction, SMoSe–XS2

Citation

Li J and Xiong L (2025) Wrinkled Janus SMoSe–XS2 (X = Mo, W) heterostructures: coupling mechanical flexibility with enhanced HER. Front. Chem. 13:1720281. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2025.1720281

Received

07 October 2025

Revised

30 October 2025

Accepted

31 October 2025

Published

19 December 2025

Volume

13 - 2025

Edited by

Shu Wang, Harbin University of Science and Technology, China

Reviewed by

Guangzhao Wang, Yangtze Normal University, China

Changlong Sun, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Li and Xiong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianping Li, szyljp0170@szpu.edu.cn

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.