- 1Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, Washington, DC, United States

- 2School of Medicine, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 3George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, United States

Objective: This secondary analysis tested the relationship of a plant-based diet index (PDI), healthful PDI (hPDI), and unhealthful PDI (uPDI), with weight loss in adults with type 1 diabetes.

Methods: Fifty-eight adults with type 1 diabetes were randomized to follow an ad libitum low-fat vegan (n = 29) or a portion-controlled, energy-restricted diet (n = 29) for 12 weeks. Food records were analyzed and PDI indices were calculated. A repeated measure ANOVA, Spearman correlations, and a linear regression model were used for statistical analysis.

Results: The PDI score increased on the vegan diet (p < 0.001) from 51.8 to 60.4, and did not change on the portion-controlled diet [effect size +6.0 (95% CI + 1.0 to +10.9); p = 0.02]; the hPDI increased on both diets, more on the vegan diet [effect size +9.1 (95% CI + 3.7 to +14.5); p = 0.002]; and uPDI increased on the vegan diet, and did not change on the portion-controlled diet [effect size +7.3 (95% CI + 1.9 to +12.7); p = 0.01]. Changes in PDI and hPDI scores correlated with changes in body weight [r = −0.35; p = 0.04 for PDI; and r = −0.52; p = 0.001 for hPDI], even after adjustment for changes in energy intake [r = −0.37; p = 0.04 for PDI; and r = −0.53; p = 0.001 for hPDI]. An increase in hPDI by 6.1 points was associated with a 1-kg weight loss (p = 0.01). There was no association between the changes in uPDI and changes in body weight (r = −0.07; p = 0.68).

Conclusion: The study results suggest that replacing animal foods with plant foods is an effective strategy for weight loss in adults with type 1 diabetes. The inclusion of “unhealthy” plant-based foods did not impair weight loss, and these benefits were independent of energy intake.

Clinical trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT04944316.

Introduction

People following plant-based diets have been shown to have lower body weight and lower risk of type 2 diabetes. Based on observational data, an attempt has been made to categorize the healthfulness of plant foods, using plant-based (PDI), unhealthful (uPDI), and healthful (hPDI), dietary indices (1). However, a previous randomized trial in overweight adults has shown that eating plant foods (both from the so-called healthful and unhealthful categories), instead of animal products, was associated with weight loss (2). The potential role, if any, of PDI in adults with type 1 diabetes has yet to be explored.

A previously published randomized clinical trial showed that, compared to a portion-controlled diet, a vegan diet resulted in a clinically significant weight loss and improvements in insulin sensitivity in adults with type 1 diabetes (3). This secondary analysis tested the associations of PDI, uPDI, and hPDI with changes in body weight in adults living with type 1 diabetes.

Methods

The study methods have been described in detail previously (3). Briefly, this randomized trial took place in 2021–2022 in Washington, DC. Adults diagnosed with type 1 diabetes were enrolled. The study protocol was approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board on February 03, 2021. The study participants signed an informed consent.

Dietary interventions

The participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to an ad libitum low-fat vegan diet (n = 29) or a portion-controlled, energy-restricted diet (n = 29). The low-fat vegan diet was free of all animal products and consisted of only plant foods. The portion-controlled diet emphasized portion control and keeping carbohydrate intake steady. Both groups met weekly online and were supported by registered dietitians. The participants tracked all their meals via Cronometer (Cronometer Inc., Revelstoke, Canada). The participants were instructed to keep their physical activity and their medications constant throughout the study. Insulin was modified in response to repeated hypoglycemia. All outcomes were measured at week 0 and 12.

At week 0 and 12, a detailed food record was filled out for three consecutive days and analyzed by a registered dietitian certified in the Nutrition Data System for Research (4). The PDI, uPDI, and hPDI were assessed (1). “Healthful” plant-based foods, as defined by the PDI system, include fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, oils, coffee and tea, and “unhealthful” plant-based foods include fruit juice, sugar-sweetened beverages, refined grains, potatoes, and sweets (1).

Statistical analysis

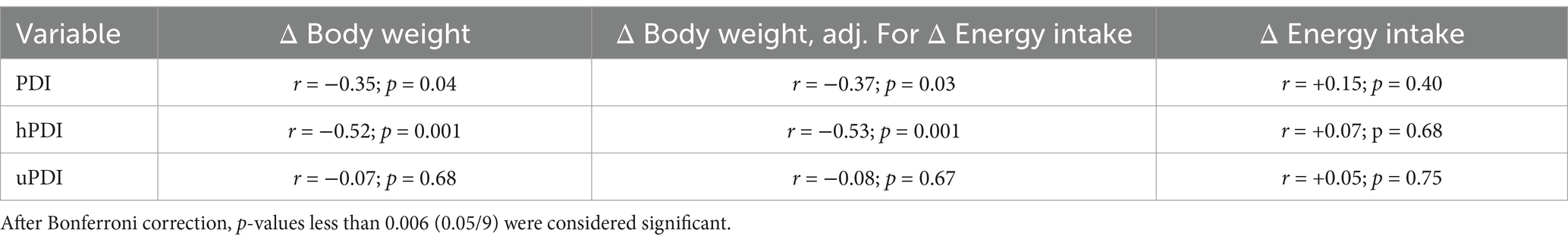

A repeated-measure ANOVA model was performed by a statistician blinded to the dietary interventions. Paired comparison t-tests were used to assess any within-group changes. Spearman correlations were used to test the relationship between changes in PDI, hPDI, and uPDI and in body weight, first unadjusted, and then adjusted for changes in energy intake, and also correlations between changes in PDI, hPDI, and uPDI, and changes in energy intake. Bonferroni correction was used, and p-values less than 0.006 (0.05/9) were presented as significant. A linear regression model was used to determine whether changes in PDI and hPDI were independent predictors of weight loss.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Fifty-eight adults were randomized to follow a vegan (n = 29) or a portion-controlled (n = 29) diet (Supplementary Figure 1). The attrition rates were similar in both groups. There was no difference between the groups in energy intake.

PDI, hPDI, uPDI

The PDI score increased on the vegan diet (p < 0.001) from 51.8 to 60.4, and did not change on the portion-controlled diet [effect size +6.0 (95% CI + 1.0 to +10.9); p = 0.02]; the hPDI increased on both diets, more on the vegan diet [effect size +9.1 (95% CI + 3.7 to +14.5); p = 0.002]; and uPDI increased on the vegan diet, and did not change on the portion-controlled diet [effect size +7.3 (95% CI + 1.9 to +12.7); p = 0.01]. As expected, compared to the portion-controlled diet, the intake of all animal foods was significantly reduced on the vegan diet. Furthermore, the scores for the “healthful” plant foods changed as follows: legumes, whole grains, and fruits significantly increased, while the scores for vegetable oils and nuts significantly decreased (as the consumption of these foods decreased) on the vegan diet. On the portion-controlled diet, only the score for whole grains increased. The scores for “unhealthful” plant foods had no significant change on either diet, with the exception of a reduced score in refined grains on the portion-controlled diet (see Table 1).

Table 1. Plant-based dietary index (PDI), healthful (hPDI), and unhealthful plant-based dietary index (uPDI), and the individual food components at baseline and 12 weeks.

Associations with changes in body weight

The participants lost 5.2 kg on the vegan diet (p < 0.001), while there was no change on the portion-controlled diet [effect size −4.3 kg (−6.1 to −2.4); p < 0.001]. The changes in PDI and hPDI scores were associated with changes in body weight (r = −0.35; p = 0.04 for PDI; and r = −0.52; p = 0.001 for hPDI) and remained largely unchanged after adjustment for changes in energy intake (r = −0.37; p = 0.04 for PDI; and r = −0.53; p = 0.001 for hPDI]. There was no correlation between the changes in uPDI and changes in body weight [r = −0.07; p = 0.68; see Table 2). A 1-kg weight loss was associated with an increase in hPDI by 6.1 points (p = 0.01). No correlation was observed between changes in PDI, hPDI, or uPDI, and changes in energy intake (Table 2).

Table 2. Spearman correlations between changes in body weight and changes in the plant-based dietary index (PDI), healthy plant-based dietary index (hPDI), and unhealthy plant-based dietary index (uPDI).

Discussion

The study demonstrated that replacing animal products with plant foods resulted in weight loss in adults with type 1 diabetes. An increase in hPDI was a predictor of weight loss, independent of changes in energy intake. No association was observed between changes in PDI, hPDI, or uPDI, and changes in energy intake, suggesting that the health benefits of replacing animal products with plant foods are independent of energy intake. These findings are consistent with previous studies.

In a large observational study, higher PDI and hPDI scores correlated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes; however, no correlation was observed for uPDI (5). Similar results came from a metabolomic analysis (6). This is, of course, not surprising, because the PDI was developed by identifying dietary factors associated with diabetes in these same cohorts. A previous randomized clinical trial in overweight adults showed, however, that the increase in all three plant-based indices correlated with weight loss. Instead of consuming animal foods, all plant foods (both “healthful” and “unhealthful”) resulted in weight loss (2). While oil and nuts are classified among the “healthful” plant foods, their consumption significantly decreased on the low-fat vegan diet, which likely contributed to the observed weight loss. There was no significant change in the consumption of the individual “unhealthful” plant food components on the vegan diet, which means that the increase in uPDI was driven by excluding animal products, so the absence of an association between changes in uPDI and changes in body weight in this study is not surprising.

The study has some important strengths, mainly the randomized, parallel design. The limitations include the collection of self-reported food records, cumbersome meal and blood glucose monitoring, which contributed to a substantial dropout rate.

In conclusion, these findings suggest that instead of consuming animal foods, eating plant foods, both “healthful” and “unhealthful,” may be an effective strategy for weight loss in adults with type 1 diabetes. The inclusion of “unhealthful” plant foods did not impair weight loss, and these benefits were independent of energy intake.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Chesapeake Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

HK: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Project administration. IF: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RS: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. JH: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Project administration. TZ-M: Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. RH: Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. NB: Resources, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was funded by the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine.

Acknowledgments

Kahleova had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors confirm that the following manuscript is a transparent and honest account of the reported research. This research is related to a previous study by the same authors titled Effect of a Dietary Intervention on Insulin Requirements and Glycemic Control in type 1 Diabetes: A 12-Week Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Diabetes. 2024 Summer;42(3):419-427. doi: 10.2337/cd23-0086. The previous study reported the main clinical outcomes, and the current submission is focusing on the plant-based dietary index, and its association with changes in body weight. The study is following the methodology explained in Does diet quality matter? A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2024 Mar;78(3):270-273. doi: 1038/s41430-023-01371-y.

Conflict of interest

HR, IF, RS, JH, TZ-M, and RH received compensation from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine for their work on this study. NB is an Adjunct Professor of Medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine. He serves without compensation as president of the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine and Barnard Medical Center in Washington, DC, nonprofit organizations providing educational, research, and medical services related to nutrition. He writes books and articles and gives lectures related to nutrition and health and has received royalties and honoraria from these sources.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1605769/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Satija, A, Bhupathiraju, SN, Rimm, EB, Spiegelman, D, Chiuve, SE, Borgi, L, et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med. (2016) 13:e1002039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039

2. Kahleova, H, Brennan, H, Znayenko-Miller, T, Holubkov, R, and Barnard, ND. Does diet quality matter? A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. (2024) 78:270–3. doi: 10.1038/s41430-023-01371-y

3. Kahleova, H, Znayenko-Miller, T, Smith, K, Khambatta, C, Barbaro, R, Sutton, M, et al. Effect of a dietary intervention on insulin requirements and glycemic control in type 1 diabetes: a 12-week randomized clinical trial. Clin Diabetes. (2024) 42:419–27. doi: 10.2337/cd23-0086

4. Schakel, SF, Sievert, YA, and Buzzard, IM. Sources of data for developing and maintaining a nutrient database. J Am Diet Assoc. (1988) 88:1268–71. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(21)07997-9

5. Chen, Z, Drouin-Chartier, J-P, Li, Y, Baden, MY, Manson, JAE, Willett, WC, et al. Changes in plant-based diet indices and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes in women and men: three U.S. prospective cohorts. Diabetes Care. (2021) 44:663–71. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1636

Keywords: diet quality, nutrition, plant-based, portion-controlled, vegan, Plant-based dietary index, Body weight, type 1 diabetes

Citation: Kahleova H, Fischer I, Smith R, Himmelfarb J, Znayenko-Miller T, Holubkov R and Barnard ND (2025) Plant-based dietary index and body weight in people with type 1 diabetes: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. Front. Nutr. 12:1605769. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1605769

Edited by:

Luciana Baroni, Scientific Society for Vegetarian Nutrition, ItalyReviewed by:

Mariana Del Carmen Fernández-Fígares, University of Granada, SpainThomas Campbell, University of Rochester, United States

Copyright © 2025 Kahleova, Fischer, Smith, Himmelfarb, Znayenko-Miller, Holubkov and Barnard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hana Kahleova, aGFuYS5rYWhsZW92YUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Hana Kahleova

Hana Kahleova Ilana Fischer1

Ilana Fischer1 Neal D. Barnard

Neal D. Barnard