Abstract

Background:

Salmonella enterica is a leading cause of foodborne illness worldwide and poultry products, particularly chicken meat and there is growing interest in using plant extracts to protect chicken meat from Salmonella contamination during refrigeration. Solenostemma argel is a medicinal plant traditionally used to treat gastrointestinal disorders and quantitative data on its activity against Salmonella enterica are limited.

Methods:

Methanolic leaf extract was profiled by GC–MS to document major phytochemical classes. Antibacterial activity against clinical/retail S. enterica isolates was evaluated by disc diffusion and broth microdilution to determine inhibition zones, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC). A panel of GC–MS–identified constituents was subjected to in silico computational study based on oral-toxicity prediction and molecular docking against modelled outer-membrane proteins implicated in LPS assembly and membrane integrity (OmpV, LptE) to prioritize plausible membrane-active leads.

Results:

The methanolic extract displayed modest inhibition in disc-diffusion assays (mean inhibition zones were 7.8–9.7 mm). All S. enterica isolates shared a uniform MIC of 12.5 mg/ml; MBCs were strain-dependent (25 mg/ml for one isolate, 100 mg/ml for two isolates), yielding MBC/MIC ratios of 2–8 and indicating primarily bacteriostatic activity for some strains. GC–MS profiling revealed several volatile and semi-volatile metabolites of potential biological interest. However, it is important to note that some peaks, such as 1,3-dioxane and 2-[2-[2-(2-acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol, may represent laboratory-derived contaminants rather than genuine plant metabolites, emphasizing the need for rigorous contamination controls and complementary analytical approaches in future work. In silico docking prioritized a steroidal candidate [Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol] with the highest predicted affinities to OmpV (−7.9 kcal·mol−1) and LptE (−6.7 kcal·mol−1). Toxicity predictions suggested low oral toxicity for the majority of screened constituents.

Conclusion:

The methanolic leaf extract of Solenostemma argel exhibited moderate to weak in vitro anti-Salmonella activity, supported by computational docking results, and provide a foundation for further isolation, purification, and characterization of its active constituents.

1 Introduction

Food safety is a cornerstone of public health, playing a pivotal role in reducing morbidity and mortality, improving population well-being, and supporting economic development. Ensuring a safe food supply depends on rigorous scientific principles and effective regulatory frameworks. As technological advances reshape food production and distribution, updated regulations are essential to guarantee the availability of safe, nutritious foods that promote health across populations (1). Foodborne diseases remain a critical global health challenge, defined as illnesses arising from the consumption of food contaminated by pathogenic microorganisms, spoilage agents, toxins, or harmful chemicals. Contamination can occur at any stage of the food chain from primary production to final consumption (2). Major zoonotic bacterial pathogens responsible for significant illness and mortality include Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli, all of which are frequently linked to contaminated food products (3, 4).

Among these, Salmonella spp. is a leading cause of foodborne disease globally. In the European Union, Salmonella accounts for more than half of all reported foodborne outbreak cases. While poultry, livestock, and their products remain primary reservoirs, contamination is increasingly reported in diverse commodities, including dried foods, infant formula, fresh produce, and other ready-to-eat items (5). Non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) is a major public health burden, causing an estimated 93.8 million infections annually, with approximately 80.3 million linked to food consumption (6). Clinical manifestations range from self-limiting gastroenteritis, commonly caused by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, to more severe forms such as bacteremia, osteomyelitis, and reactive arthritis, often associated with S. typhimurium and S. enteritidis (Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis). Enteric fever, caused by S. typhi and S. paratyphi, and asymptomatic carrier states further complicate control strategies (7, 8). The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Salmonella strains is an escalating threat to effective treatment. Resistance is particularly alarming in isolates from agricultural sources, with high rates reported for sulfamethoxazole (91%), sulfonamides (51%), and ceftiofur (28.9%) (9).

Poultry and poultry products are recognized as major sources of Salmonella, a leading cause of serious foodborne infections in humans. Numerous poultry-associated Salmonella outbreaks have been documented worldwide, and the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella typhi is an escalating concern, particularly across Asia and Africa (10). The contamination of food with Salmonella could be attributed to many reasons, such as improper hygiene during food processing, contaminated water, or poor agricultural practices. Interestingly, the reason varies between locations; non-typhoidal Salmonella contamination is widespread in poultry, meat, and vegetable products in India (11), while in Senegal, high contamination levels were reported in leafy greens such as mint, parsley, and lettuce, with supermarket samples showing higher prevalence than those from open markets (12). Unfortunately, the misuse of antibiotics in agriculture, including in livestock production and crop protection, has compounded the problem by facilitating the transfer of resistance genes along the food chain. Once ingested, these resistant bacteria can horizontally transfer resistance determinants to commensal or pathogenic bacteria in the human gut, further amplifying the antimicrobial-resistance crisis (13, 14). The computational (in silico) studies reported that, the outer membrane of Salmonella sp., specifically OmpV protein, are vital for its survival and interaction with hosts, contributes to membrane integrity and may be involved in nutrient acquisition and host-pathogen binding (15, 16). LptE is an important protein that helps build and transport lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the outer membrane of bacteria (17, 18). Lack of LptE, the LPS cannot be properly inserted, then membrane can be weakened and make the bacteria more to stress and immune attacks. This makes LptE necessary for bacterial survival. Because both OmpV and LptE are indispensable for outer membrane function and virulence (19), they represent attractive molecular targets for the development of novel anti-Salmonella agents. Targeting such non-redundant, membrane-associated proteins offers a strategic approach to hinder bacterial viability and pathogenicity while reducing the likelihood of resistance development.

Solenostemma argel (Del.) Hayne is known as Hargal, an arid plant in the Apocynaceae family. It is the primary source of traditional medicine in a variety of countries, including Sudan, Egypt, Libya, Algeria and Saudi Arabia (20). In traditional medicine, almost all parts of Solenostemma argel (S. argel) are employed in traditional healing practices. Its leaves, bark, and stems are particularly valued for managing ailments such as diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, cough, gastrointestinal spasms, urinary tract infections, rheumatism, as well as liver and kidney diseases (21). Scientific investigations have validated several biological activities of S. argel, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, insecticidal, and nematocidal properties (22). S. argel is rich of some important phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, triterpenes, tannins and saponins (23). However, dose optimization in phytomedicine is essential, as high concentrations may cause hepatic and renal toxicity, whereas lower doses can retain therapeutic efficacy. In rats, doses of 600 mg/kg BW (BW, body weight) induced adverse liver and kidney effects, while lower doses remained beneficial (24). While some biological activities of S. argel have been documented, there is a clear paucity of recent studies on plants from Sudan, where distinct environmental factors may alter their phytochemical composition and associated bioactivities. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the antibacterial potential of S. argel against Salmonella strains isolated from chicken meat, while characterizing its phytochemical composition using GC–MS analysis. Furthermore, the study investigated the interactions of key bioactive compounds with essential Salmonella outer membrane proteins, OmpV (Outer membrane protein V) and LptE (Lipopolysaccharide transport protein E), through molecular docking, integrating experimental and computational approaches to elucidate the mechanistic basis of its anti-Salmonella activity and assess its potential as a natural agent for controlling Salmonella contamination in poultry products.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant collection and extraction

Leaves of S. argel cultivated in Gezira, central Sudan, were collected in 2023 and scientifically identified by a qualified botanist. The plant material was air-dried and stored in well-sealed plastic bags until further use. Prior to extraction, the dried leaves were ground into a fine powder using a mechanical blender. A 50 g portion of the powdered material was macerated in 500 ml of 80% methanol for 7 days with intermittent shaking. The mixture was filtered twice through Whatman No. 1 filter paper, and the filtrate was incubated at 40°C for approximately 2 weeks to allow complete solvent evaporation. The resulting dried methanolic extract was carefully scraped, collected under aseptic conditions, and stored in a clean, airtight container in the fridge until reconstitution for experimental use (25). The dried extract was reconstituted in 80% methanol for antibacterial testing, which does not affect bacterial growth.

2.2 GC–MS analysis

The gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) investigation of the methanolic leaf extract of S. argel was conducted using a Perkin-Elmer Clarus 680 system (Perkin-Elmer, Inc., USA) coupled with an Elite-5MS fused silica capillary column (30 m length × 250 μm internal diameter × 0.25 μm film thickness). Helium gas of high purity (99.99%) was used as the carrier at a constant flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. The injection volume was 1 μl, applied in split mode at a 10:1 ratio, with the injector temperature set at 250°C. The column oven temperature was originally set at 50°C for 3 min, increased at a rate of 10°C/min to 280°C, and then elevated to 300°C, which was sustained for 10 min. Electron ionization was performed at 70 eV with a scan duration of 0.2 s, capturing mass fragments within the range of 40–600 m/z. The identification of phytochemical ingredients was achieved by comparing retention times, peak areas, peak heights, and mass spectral fragmentation patterns with reference compounds in the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) spectrum library (26).

2.3 Bacterial strain isolation and characterization

Chilled chicken samples were purchased from multiple retail outlets in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, and transported to the laboratory in insulated coolers to maintain the cold chain. On receipt, the external surface of each primary package was disinfected with an appropriate surface sterilant, and the package was aseptically opened. Approximately 0.1 ml of the exudate fluid present within each package was aseptically aspirated using a sterile 1 ml syringe and immediately inoculated onto selective/differential media, including Salmonella–Shigella (SS) agar and xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) agar, to facilitate the isolation of Salmonella spp.

A sterile loop was used to streak a single drop of sample onto each plate using a four-quadrant streaking technique to obtain well-separated colonies. Inoculated plates were incubated inverted at 37°C for 24 h. Presumptive Salmonella colonies were sub-cultured onto nonselective agar to obtain pure cultures. Gram staining was performed on pure isolates as part of routine preliminary characterization.

2.4 Automated identification and antibiotics profiling

Presumptive Salmonella isolates obtained through routine cultural and biochemical procedures were subjected to confirmatory testing using the MicroScan WalkAway 96 Plus system (Beckman Coulter, USA). Pure colonies from 24-h cultures grown on blood agar were suspended in sterile saline to match a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard and subsequently inoculated into the Negative Combo Panel Type 44 (PN B1017-207). The system, which integrates conventional biochemical reactions with fluorogenic substrates, was operated at 35 ± 2°C for 18–24 h. Isolates were identified at the species level, and confirmation as S. enterica was accepted when identification probability was ≥90%. For antibacterial susceptibility testing, the same standardized inoculum was dispensed into the Negative MIC Panel Type 44 (PN B1017-207) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and following CLSI recommendations. Panels were incubated within the WalkAway 96 Plus system at 35 ± 2°C for 16–20 h. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were automatically calculated by the instrument and interpreted according to CLSI breakpoints (27). The antibiotics tested included 25 to 27 antibiotics (Supplementary Figure 1). Prior to experimental procedures, quality control was routinely verified using E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 reference strains.

2.5 Disc diffusion assay

The antibacterial activity of the methanolic extract of S. argel against the 3 isolated and identified Salmonella strains. Collected from chicken was evaluated using the disc diffusion method, adapted with minor modifications from a previously described methodology (28), with minor modifications. Briefly, bacterial suspensions were adjusted to approximately 1 × 106 CFU/ml and uniformly spread over the surface of Mueller-Hinton agar plates using sterile cotton swabs. Sterile filter paper discs (6 mm diameter) saturated with 10 μl of the methanol extract (at 200 mg/ml) were placed onto the inoculated plates, under aseptic conditions. Blank discs saturated with chloramphenicol (2.5 mg/ml) were loaded as positive controls. Prior to the experiment, 80% methanol was tested and showed no inhibitory effect on bacterial growth. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Following incubation, inhibition zone diameters were measured in millimeters. All assays were performed in triplicate, and the results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation.

2.6 Determination of MIC and MBC values

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the methanol extract of S. argel against the tested bacteria was determined using the microbroth dilution method in sterile 96-well microplates, as previously described in standardized protocols. Briefly, each well was filled with 95 μl of double-strength Mueller-Hinton broth, followed by serial dilutions of the test sample (dissolved in 5% DMSO) and chloramphenicol as the reference antibiotic. Subsequently, 10 μl of bacterial suspensions adjusted to 106 CFU/ml were inoculated into each well. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Following incubation, 40 μl of a TTC solution (0.2 μg/ml) was added, and the plates were re-incubated for 2 h. A color change from colorless to red indicated microbial activity. The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration at which no visible bacterial growth was observed. The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined by sub-culturing 50 μl aliquots from wells corresponding to the MIC and higher concentrations onto Mueller-Hinton agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration that completely inhibited bacterial growth. The MBC/MIC ratio was subsequently calculated to distinguish between bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity (29).

2.7 Computational studies of S. argel compounds

2.7.1 Toxicity assessment of S. argel-derived compounds

To assess the potential toxicity of compounds isolated from S. argel, the ProTox 3.0 online platform1 was utilized (accessed on 7 July 2025), as described by (30). This tool applies integrated computational models to predict a variety of toxicological endpoints. The chemical structures of the selected compounds were first converted into simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) format before submission (Supplementary Table S1).

2.7.2 Protein target acquisition and structure modeling

Since crystal structures for the target outer membrane proteins, namely OmpV from S. typhimurium (MipA/OmpV family protein, UniProt ID: A0A634SAW8) and LptE from S. enteritidis (LPS-assembly lipoprotein LptE, UniProt ID: A0A5W2VQP4), were unavailable in the protein data bank (PDB), their respective amino acid sequences were retrieved from UniProt2 in FASTA format. The three-dimensional structures of these proteins were subsequently generated through homology modeling using the Swiss-Model web tools3 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

2.7.3 Refinement and validation of Salmonella outer membrane protein models

To enhance the structural accuracy of the predicted outer membrane proteins, refinement was performed using the ModRefiner tool. The quality of the refined models was evaluated through Ramachandran plot analysis and further validated using the ERRAT and PROCHECK programs, accessed via the SAVES v6.1 server4 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

2.7.4 Binding pocket identification and drug ability assessment

Potential ligand-binding sites within the selected protein structures were identified and analyzed using FPocketWeb 1.0.1 (accessed on 13 July 2025), a web-based tool that applies the FPocket algorithm to detect and evaluate druggable pockets in protein models.

2.7.5 Molecular interaction analysis

Molecular docking of ligands with target receptors was conducted using the CB-Dock2 web server5 (31) (accessed on 10 July 2025), which integrates cavity detection and template-based docking to enhance prediction reliability. To ensure reproducibility, the center coordinates and size of the primary docking cavity identified by CB-Dock2 for each protein are provided in Supplementary Table S8. The protonation states of ionizable residues and ligands were assigned by default for a physiological pH of 7.4 prior to docking simulations. Blind docking was performed, and the conformations with the highest binding affinities were selected for further interaction analysis with the proteins’ amino acid residues. Visualization of the docking results was carried out using Discovery Studio Visualizer (v21.1.0.20298) for 2D interaction diagrams and UCSF ChimeraX (v1.8) for 3D structural representations.

2.8 Statistical analysis

The results were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and all experiments were conducted in triplicate (n = 3). GraphPad Prism 9 and XLSTAT v.2016 were employed to conduct statistical analyses. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was followed by Tukey’s post hoc test to evaluate mean differences, with p < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of bioactive compounds

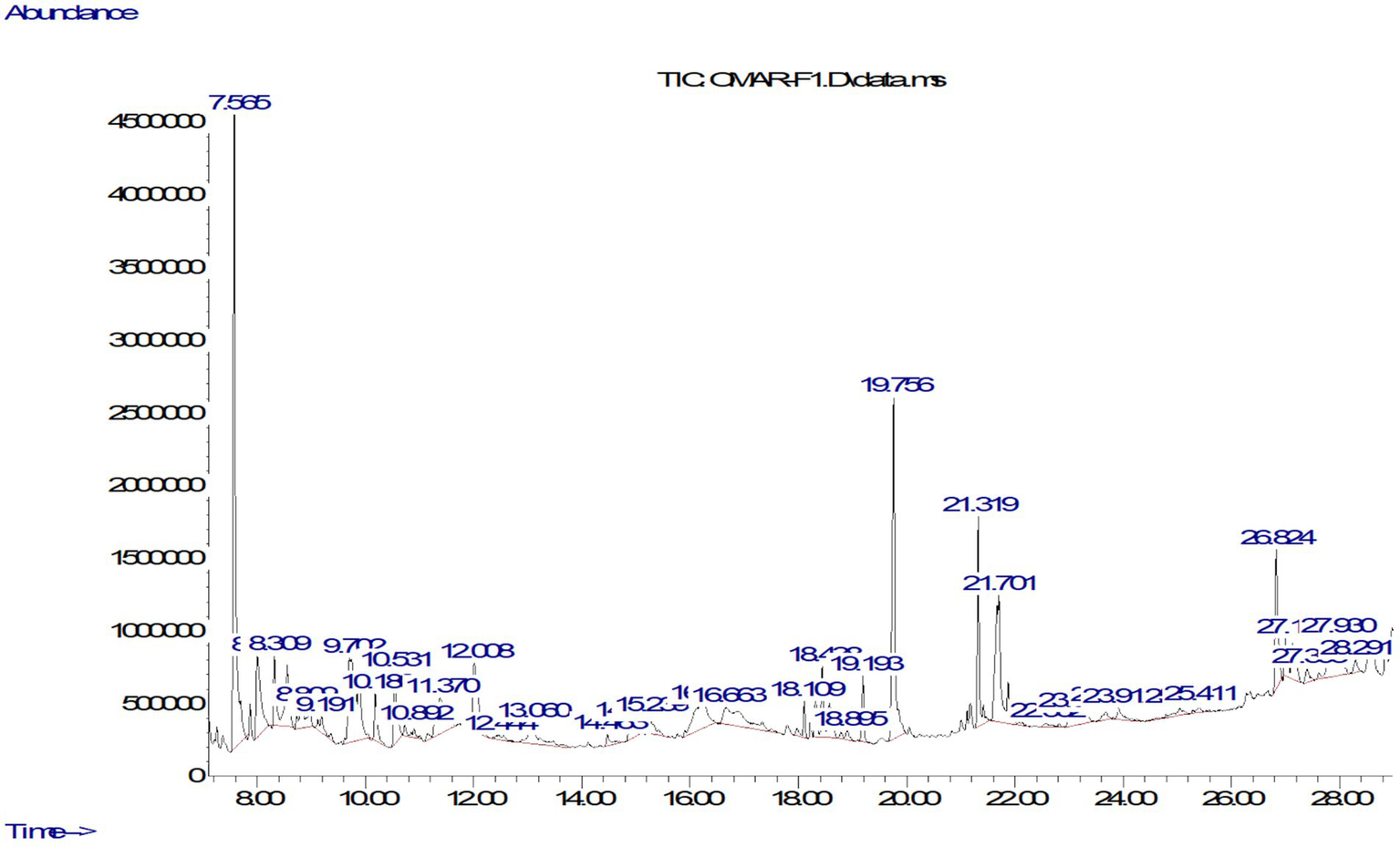

The GC–MS analysis of the extract of S. argel methanolic extract demonstrated a chemical diversity, involving the identification of 32 compounds achieved by employing multiple phytochemical classes including phenolic compounds, fatty acids and derivatives, esters and alcohols, terpenes and steroids, and multiple classes of “others” (Table 1). The compounds were identified by mass spectral matching with the NIST library and ranking based on their normalized peak area (%) indication representing relative abundance (32). The Chromatogram in Figure 1 was in reasonable agreement with the tabled data, particularly for the highest abundance species. Although 1,3-dioxane was clearly detected in the chromatogram with a relatively high peak area (14.07%), it should not be considered a natural component of the plant. These types of chemicals typically originate from external sources, such as leftover solvents or inexpensive plastic containers used during sample collection, storage, or preparation. Therefore, these signals were treated as possible contaminants (not from the plant) instead of natural plant components. The implications of these potential contaminants for phytochemical profiling are discussed in the section on study limitations. Equally, the peak at RT = 19.755 min identified Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester, a saturated fatty acid from plants known to exhibit antibacterial properties, was accurate with both the peak and displayed in the data. Interestingly, separate peaks in the RT = 25.8 to 27.4 min range were identified as long-chain unsaturated fatty acids including Oleic acid, 2-Methyl-Z,Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol (33). These compounds are known for their ability to disrupt microbial and fungal membranes, thus enabling the biological activity of the extract. Phytochemically, the analysis of accumulated concentrations indicates that phenolic compounds are the strongest group at 34.31% of the entire composition as provided in Table 2 (34). The group contains phenolic compounds that feature bioactivity data, such as Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol, and (E)-Stilbene. The second strongest class is “Others” at 22.59%, which also includes various cyclic compounds and possibly synthetic compounds that may be artifacts or misidentified. The next component was fatty acids, and fatty acids and phosphates, at 19.26% of the total. Fatty acids include some highly biologically active molecules or fatty acids: Hexadecanoic acid, Oleic acid, and Linolenic acid (35). The next two components were esters and alcohols at 9.14%, and terpenes and steroids at 8.90%. This group includes compounds such as Phytol and Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol. Overall, the classes of compounds support the traditional uses of the plant, considering that known and bioactive compounds are generally understood to permeate the microbial membranes to interrupt membrane integrity and inactivate oxidative enzymes (36). Fatty acids of the plant provide the ability to destabilize the bacterial cell envelope. Both Phytol and Oleic acid are reported as antifungal and antibacterial compounds (37). Overall these types of chemical processes and compounds provide plausible support for ethnobotanically based use of Rhazya stricta in the treatment of infections and skin conditions (38). However, there are four compounds that may be problematic in respect to their authenticity. These include: 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol and Trimethyl 1,3,3-oxydipropanoate which are not commonly reported in plants and likely included as residual solvents. Potentially some of these compounds may stem from plastic substrates or PCR tubes that are disposable products used in contemporary laboratory techniques. However, there are additional sugars such as D-Galactose, 6-deoxy- and 1-alpha-D-Glucopyranoside, methyl that normally require derivatization prior to GC–MS detection and therefore may also be incorrectly classified due to the usage of a library of products (39). Overall, the GC–MS results show a good representation of the plant’s potential chemical activity as they relate to phenolic compounds and fatty acid phosphates.

Table 1

| Compound | Phytochemical class | Mol weight | RT (min) | Area | Absolute height | Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Dioxane | Others | 88.052 | 7.565 | 13,444,078 | 4,707,884 | 14.07 |

| Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | Phenolic Compounds | 206.32 | 8.001 | 11,424,914 | 378,634 | 11.96 |

| Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17.beta.-ol | Terpenes and Steroids | 270.37 | 8.309 | 8,053,841 | 1,232,894 | 8.43 |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy- | Phenolic Compounds | 128.1 | 8.809 | 7,352,661 | 815,127 | 7.7 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 270.45 | 9.191 | 6,984,525 | 1,245,599 | 7.31 |

| Phytol | Esters and Alcohols | 296.53 | 9.702 | 3,841,973 | 440,999 | 4.02 |

| Oleic Acid | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 282.47 | 10.18 | 3,698,228 | 550,326 | 3.87 |

| 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | Phenolic Compounds | 150.17 | 10.531 | 3,658,127 | 584,274 | 3.83 |

| 2-Furanmethanol, 5-ethyltetrahydro- | Phenolic Compounds | 116.073 | 10.892 | 3,575,890 | 830,048 | 3.74 |

| 2-Furancarboxaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- | Phenolic Compounds | 126.11 | 11.37 | 3,481,926 | 539,467 | 3.64 |

| 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol | Others | 410.225 | 12.008 | 3,370,947 | 828,786 | 3.53 |

| 2-Acetylamino-3-hydroxy-propionic acid | Alkaloids | 119.11 | 12.444 | 3,318,852 | 718,600 | 3.47 |

| (E)-Stilbene | Phenolic Compounds | 180.25 | 13.06 | 3,291,431 | 473,110 | 3.44 |

| 12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z, Z)- | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 298.16 | 14.463 | 3,069,228 | 486,392 | 3.21 |

| Oxeprime, 2,7-dimethyl- | Others | 272.44 | 14.878 | 2,118,339 | 920,014 | 2.22 |

| 2-Propanol, 1-(1-methylethoxy)- | Esters and Alcohols | 104.15 | 15.239 | 2,056,957 | 717,840 | 2.15 |

| 2-Methyl-Z, Z, Z-3,13-octadecadienol | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 280.5 | 16.27 | 1,774,904 | 420,927 | 1.86 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 256.42 | 16.663 | 1,544,173 | 479,010 | 1.62 |

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, (Z, Z, Z)- | Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 278.27 | 18.109 | 1,324,866 | 507,245 | 1.39 |

| Trimethyl 1,3,3-oxydipropanoate | Esters and Alcohols | 190.19 | 18.438 | 1,130,752 | 850,422 | 1.18 |

| Pentanoic acid, 3-methyl-, methyl ester | Esters and Alcohols | 116.16 | 18.895 | 1,101,396 | 577,088 | 1.15 |

| D-Galactose, 6-deoxy- | Carbohydrates and Derivatives | 164.16 | 19.193 | 955,455 | 413,665 | 1 |

| 1-alpha-D-Glucopyranoside, methyl | Carbohydrates and Derivatives | 194.18 | 19.756 | 732,924 | 554,502 | 0.77 |

| 2,3-Dimethyldecane | Others | 170.33 | 21.319 | 732,267 | 473,696 | 0.77 |

| 11-Dodecen-1-ol acetate | Esters and Alcohols | 212.33 | 21.701 | 615,769 | 466,999 | 0.64 |

| Acetamide, N-(3-oxo-4-isoxazolidinyl), (R)- | Alkaloids | 144.12 | 23.083 | 526,131 | 337,788 | 0.55 |

| Tricyclo[7.1.0.0(4,6)]decane-5-carboxamide | Others | 207.16 | 23.678 | 487,079 | 743,358 | 0.51 |

| Cyclopropane carboxamide, 2-cyclopropyl-2-methyl- | Others | 207.16 | 23.912 | 487,079 | 743,358 | 0.51 |

| Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane, 2,6,6-trimethyl- | Terpenes and Steroids | 138.2 | 25.049 | 449,445 | 314,250 | 0.47 |

| 1,3-Cyclohexanediol, 5-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)- | Others | 158.25 | 25.411 | 418,936 | 286,447 | 0.44 |

| 6-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-pyran-2,4-dione | Others | 128.1 | 26.824 | 364,922 | 284,971 | 0.38 |

| Oxirane, 2-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)- | Others | 100.16 | 27.122 | 155,139 | 482,516 | 0.16 |

Chemical compounds identified in the methanolic extract of S. argel using GC–MS analysis.

Figure 1

GC–MS chromatogram of the methanol extract of S. argel.

Table 2

| Phytochemical class | The percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | 34.31 |

| Others | 22.59 |

| Fatty Acids and Derivatives | 19.26 |

| Esters and Alcohols | 9.14 |

| Terpenes and Steroids | 8.9 |

| Alkaloids | 4.02 |

| Carbohydrates and Derivatives | 1.77 |

Percentage composition of phytochemical classes identified in the methanolic extract of S. argel by GC–MS analysis.

3.2 Bacteriological assessment

Automated identification and antibiotic susceptibility profiling of the presumptive Salmonella isolates yielded notable findings (Supplementary Figure S1). Among the four tested samples, sample 1 was identified as Proteus mirabilis rather than Salmonella spp., while the remaining three were confirmed as Salmonella enterica. The antibiotic profiling demonstrated that P. mirabilis was susceptible to all 25 tested antibiotics, suggesting that this isolate likely represents a commensal member of the chicken intestinal microbiota. Its presence on poultry meat is therefore most plausibly attributed to fecal contamination during slaughtering processes. Although P. mirabilis is not recognized as a primary poultry pathogen, it may contribute to cellulitis in broilers and, importantly, has been implicated in human infections following the consumption of contaminated or undercooked poultry (40). These results highlight its potential role as a food safety concern, emphasizing the need for stringent hygiene measures during poultry processing to mitigate risks of cross-contamination and subsequent transmission to consumers. The other samples (number 2, 3, and 4) were all confirmed to be Salmonella enterica. Antibiotic susceptibility profiling revealed that among 25 antibiotics tested, sample 2 was resistant to 6 antibiotics, sample 3 was resistant to 2 antibiotics, while sample 4 was resistant to 6 different antibiotics. These results indicate that samples 2 and 4 are multi-drug resistant (MDR) Salmonella enterica strains. MDR bacteria are widely defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one antimicrobial agent in three or more distinct antimicrobial classes (41).

3.3 Anti-Salmonella activity of S. argel

The results of the disc-diffusion test are shown in Table 3 and (Supplementary Figure S2). The antibacterial activity of S. argel methanol extract compared to chloramphenicol (as a positive control) was assessed against Proteus mirabilis and Salmonella enterica using the disc diffusion method. The extract exhibited inhibition zones ranging from 7.83 ± 0.29 to 10.0 ± 1.0 mm. Statistical analysis revealed that the extract produced comparable inhibitory effects against P. mirabilis and two S. enterica isolates (Samples 1–3; p > 0.05), whereas the inhibition observed against the fourth S. enterica isolate was significantly lower (p < 0.05).

Table 3

| Sample number | Bacterial strain | Mean inhibition zones (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solenostemma argel methanol extract (10 μl/disc from 100 mg/ml) | Chloramphemicol (10 μl/disc from 5 mg/ml) | ||

| 1 | Proteus mirabilis | 10.0 ± 1.0ᵃ | 33.33 ± 0.58ᵃ |

| 2 | Salmonella enterica | 9.67 ± 0.58ᵃ | 7.50 ± 0.50ᶜ |

| 3 | Salmonella enterica | 9.33 ± 0.58ᵃ | 23.33 ± 0.58ᵇ |

| 4 | Salmonella enterica | 7.83 ± 0.29ᵇ | 8.33 ± 0.58ᶜ |

Antibacterial activity of S. argel methanol extract against the selected strains using disc diffusion method.*

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates (n = 3). Mean values labeled with dissimilar letters are significantly different according to Tukey’s honestly significant difference test following one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

The final bacterial density reached approximately 106 CFU/ml.

In contrast, chloramphenicol demonstrated markedly higher inhibition against P. mirabilis (33.33 ± 0.58 mm) compared with all S. enterica isolates (p < 0.05). Among S. enterica, the response was strain-dependent: one isolate exhibited intermediate sensitivity (23.33 ± 0.58 mm), while the remaining two were significantly less susceptible (7.50 ± 0.50 and 8.33 ± 0.58 mm). These findings highlight the consistent but moderate antibacterial effect of S. argel extract across strains, while chloramphenicol showed variable activity ranging from strong inhibition of P. mirabilis to markedly reduced efficacy against certain S. enterica isolates. To our knowledge, this study presents the first investigation into the anti-Salmonella activity of S. argel specifically against Salmonella enterica. Existing reports indicate weak to negligible activity, the aqueous, butanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of S. argel were reported to exhibit no antibacterial activity. In contrast, the diethyl ether extract demonstrated moderate efficacy against P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (42). The aqueous extract of S. argel exhibited a 17 mm inhibition zone against Escherichia coli at a concentration of 25% (w/v) (43). The ethanolic leaf extract of S. argel exhibited superior antibacterial activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae compared to its methanolic counterpart (44). Consequently, methanol may not be the optimal solvent for the efficient extraction of much antibacterial compounds from this plant.

As shown in Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S3, the MIC of S. argel methanolic extract was consistent across all tested isolates at 12.5 mg/ml. However, the MBC varied between 25 and 100 mg/ml. Consequently, the calculated MBC/MIC ratios ranged from 2 to 8. Ratios of 2 observed against P. mirabilis and one S. enterica isolate indicated bactericidal activity, while ratios of 8 in two S. enterica isolates suggested primarily bacteriostatic effects. These findings highlight that the extract exerted growth inhibition at a uniform MIC, but bactericidal activity was strain-dependent and required higher concentrations in certain isolates. When compared with the positive control chloramphenicol, the extract displayed a weaker antibacterial activity profile. Chloramphenicol exhibited much lower MIC values (<0.078–0.312 mg/ml) but showed variable bactericidal capacity: one isolate demonstrated a clear bactericidal effect (MBC/MIC ≥1), whereas others were bacteriostatic with ratios exceeding 4, including one as high as ~20. This comparison demonstrates that, while chloramphenicol exhibited markedly greater potency, the S. argel extract was still capable of exerting bactericidal activity against selected strains, although at comparatively higher concentrations. These findings highlight its possibility of being supplementary antimicrobial source and emphasize the need for purification and characterization of its active constituents in future investigations, which may reveal compounds with enhanced and more consistent antibacterial efficacy. Our assumption is based on the fact that a tested compound is classified as bactericidal if the MBC/MIC ratio is ≤4.0. Conversely, a ratio exceeding 4.0 indicates bacteriostatic/fungistatic properties (45). Importantly, the disparity between the extract and chloramphenicol highlights the limited potency of S. argel compared with conventional antibiotics, although its activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens remains noteworthy. Previous research on S. argel’s antibacterial properties has largely focused on broader bacterial targets or used different extraction methods. The reported MIC of 12.5 mg/ml for S. argel is notably high, indicating weak antimicrobial activity. In natural product research, plant extracts with MIC values above 1.5 mg/ml are generally considered to have poor or negligible activity. For instance, extracts with MIC values between 0.6 and 1.5 mg/ml are classified as moderate inhibitors, while those above 1.5 mg/ml are regarded as weak inhibitors (46).

Table 4

| Sample number | Bacterial strain | Solenostemma argel methanol extract (mg/ml) | Effect of extract | Chloramphenicol (mg/ml) | Effect of antibiotic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | MIC | MBC | MBC/MIC | ||||

| 1 | Proteus mirabilis | 12.5 | 25 | 2 | Bactericidal | <0.078 | 1.25 | >16.0 | Bacteriostatic |

| 2 | Salmonella enterica | 12.5 | 25 | 2 | Bactericidal | 0.312 | 1.25 | 4.01 | Bacteriostatic |

| 3 | Salmonella enterica | 12.5 | 100 | 8 | Bacteriostatic | <0.078 | 0.078 | ≥1.0 | Bactericidal |

| 4 | Salmonella enterica | 12.5 | 100 | 8 | Bacteriostatic | 0.312 | 6.25 | 20.03 | Bacteriostatic |

The results of MIC and MBC tests of S. argel methanol extract compared to the positive control (chloramphenicol).

Sulieman et al. (47) examined aqueous extracts of S. argel against Gram-negative bacteria, including Salmonella typhi, reporting successful inhibition in disc diffusion assays. However, MIC/MBC data were not provided, limiting quantitative comparison in terms of potency (47). A comprehensive review of S. argel’s phytochemical and pharmacological properties described its general antimicrobial potential, but with minimal emphasis on quantitative anti-Salmonella data (20). Future investigations should focus on isolating the antibacterial constituents of S. argel using diverse solvents and extraction methodologies. In addition, in vivo studies are essential to validate and substantiate the traditional use of this plant in treating abdominal disorders.

On the other side, while our results provide useful baseline data on the antibacterial properties of S. argel extract, it is crucial to situate them within the broader challenge of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial strains and to explore possible mechanistic implications. MDR in Salmonella and other gram-negative pathogens is increasingly common, reducing therapeutic options and increasing urgency for novel antimicrobials such as ESBL-producing Salmonella (48). The variation we observed in extract sensitivity among different S. enterica isolates, some being bactericidal at moderate doses, others only bacteriostatic at much higher concentrations, likely reflects genetic or phenotypic heterogeneity, possibly including differences in outer membrane structure, efflux pump activity, or other resistance determinants. Moreover, our GC–MS profiling suggests the presence of both phenolic acids (or related phenolic compounds) and fatty acids among the volatile or semi-volatile constituents. Phenolic compounds, such as gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, and vanillic acid, have been shown in S. typhimurium to disrupt the bacterial outer membrane, lead to membrane permeabilization, inhibit virulence gene expression, and affect growth even in MDR pathogens (49). Free fatty acids are likewise reported in the literature to act via multiple mechanisms: destabilizing membranes, uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation, interrupting electron transport chains, and inhibiting nutrient uptake (50). Accordingly, the antibacterial activity of S. argel extract likely arises from both independent and synergistic actions of phenolics and fatty acids: phenolics may disrupt membrane integrity or regulatory elements (e.g., virulence factors, outer membrane proteins), while fatty acids could enhance this effect by further permeabilizing membranes or inducing metabolic dysfunction. This synergy may explain why some strains are killed at lower concentrations, whereas others are only inhibited at higher doses. Future work should fractionate the extract to test phenolic and fatty acid fractions individually and in combination, alongside profiling bacterial resistance determinants. Such studies would clarify strain-specific responses and could guide optimized formulations to overcome MDR phenotypes.

3.4 Computational assessment

A non-toxic rating for oral use is crucial for drug candidates, particularly those taken orally, as it reduces the risk of adverse in the body. In silico toxicity analysis of 19 S. argel-derived compounds was showed a mainly favorable safety profile (Table 5), with the majority falling into toxicity classes 4 to 6, based on LD₅₀ values predicted by ProTox-II. (E)-Stilbene, Hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, and 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol compounds were classified as non-toxic (Class 6) with 100% prediction accuracy. Organ toxicity predictions were showed most compounds inactive for hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity (Supplementary Table S2). While a few compounds such as Oleic acid (Class 2) and 2-Furancarboxaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- (Class 3) showed higher oral toxicity risks, their organ toxicity scores remained largely inactive. Compound 3 (Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol) demonstrated no detectable toxicity (LD50 = 5,010 mg/kg, Class 6) with strong binding ability, this compound shows great promise as a drug candidate. To confirm the predicted low-toxicity profile of the identified compounds, further studies should therefore include experimental assays to validate cytotoxicity, organ-specific toxicity, and systemic safety, before considering clinical translation.

Table 5

| Compound name | LD50 (mg/kg) | Predicted toxicity class* | Average similarity (%) | Prediction accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Dioxane | 2,000 | 4 | 71.9 | 69.26 |

| Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 2,820 | 5 | 188.31 | 70.97 |

| Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol | 5,010 | 6 | 77.18 | 68.26 |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy- | 595 | 4 | 60.38 | 68.07 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 5,000 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

| Phytol | 1,016 | 4 | 76.9 | 69.26 |

| Oleic Acid | 48 | 2 | 100 | 100 |

| 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 1,920 | 4 | 85.3 | 70.97 |

| 2-Furancarboxaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- | 79 | 3 | 47.53 | 54.26 |

| 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol | 11,000 | 6 | 100 | 100 |

| 2-Acetylamino-3-hydroxy-propionic acid | 1,300 | 4 | 61.83 | 68.07 |

| (E)-Stilbene | 920 | 4 | 100 | 100 |

| 12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z, Z)- | 5,000 | 5 | 70.79 | 69.26 |

| 2-Propanol, 1-(1-methylethoxy)- | 4,400 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

| 2-Methyl-Z, Z, Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 1,016 | 4 | 81.36 | 70.97 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | 900 | 4 | 100 | 100 |

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid | 4,260 | 5 | 79.3 | 69.26 |

| Pentanoic acid, 3-methyl-, methyl ester | 5,000 | 5 | 87.5 | 70.97 |

| 6-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-pyran-2,4-dione | 595 | 4 | 60.38 | 68.07 |

Predicted oral toxicity of S. argel compounds from ProTox-II web server.

Class 1: fatal if swallowed (LD50 ≤ 5); Class 2: fatal if swallowed (5 < LD50 ≤ 50); Class 3: toxic if swallowed (50 < LD50 ≤ 300); Class 4: harmful if swallowed (300 < LD50 ≤ 2,000); Class 5: may be harmful if swallowed (2,000 < LD50 ≤ 5,000); Class 6: nontoxic (LD50 > 5,000).

The S. argel compounds displayed varied physicochemical properties (Table 6), with LogP values ranging from 0.46 to 4.99. Ten compounds were showed favorable oral bioavailability. Most compounds complied with RO5, suggesting potential for oral bioavailability. LogP values ranged from 0.46 to 4.99, with acceptable hydrogen bond donor and acceptor counts across most compounds, highlight its relevance for future pharmacological and bioavailability studies. Notably, Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol, a promising docking hit, showed only one RO5 violation, possessing a LogP of 2.94 and 1 hydrogen bond donor and acceptor.

Table 6

| Compound name | Hydrogen bonds | LogP* (iLogPo/w) | Molar refractivity | RO5 violation** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptor Donor | |||||

| 1,3-Dioxane | 2 | 0 | 1.49 | 21.4 | 0 |

| Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | 1 | 1 | 2.65 | 67 | 0 |

| Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol | 1 | 1 | 2.94 | 79 | 1 |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy- | 4 | 2 | 1.19 | 32.39 | 0 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 2 | 0 | 4.41 | 85.12 | 1 |

| Phytol | 1 | 1 | 4.48 | 97.99 | 1 |

| Oleic Acid | 2 | 1 | 3.8 | 85.13 | 1 |

| 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | 1 | 0 | 2.29 | 43.02 | 0 |

| 2-Furancarboxaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- | 3 | 1 | 0.94 | 30.22 | 0 |

| 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy] ethoxy]ethanol | 5 | 1 | 2.37 | 45.19 | 0 |

| 2-Acetylamino-3-hydroxy-propionic acid | 4 | 3 | 0.46 | 32.08 | 0 |

| (E)-Stilbene | 0 | 0 | 2.72 | 61.81 | 1 |

| 12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z,Z)- | 1 | 0 | 4.5 | 92.69 | 1 |

| 2-Propanol, 1-(1-methylethoxy)- | 2 | 1 | 2.12 | 33.2 | 0 |

| 2-Methyl-Z,Z,Z-3,13-octadecadienol | 1 | 1 | 4.99 | 93.66 | 1 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | 2 | 1 | 3.85 | 80.8 | 1 |

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid | 2 | 1 | 3.62 | 79.38 | 0 |

| Pentanoic acid, 3-methyl-, methyl ester | 2 | 0 | 2.3 | 37.05 | 0 |

| 6-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-pyran-2,4-dione | 4 | 2 | 1.19 | 32.39 | 0 |

Physicochemical properties and drug-likeness of S. argel compounds.

Octanol–water partition coefficient.

Lipinski rule of five.

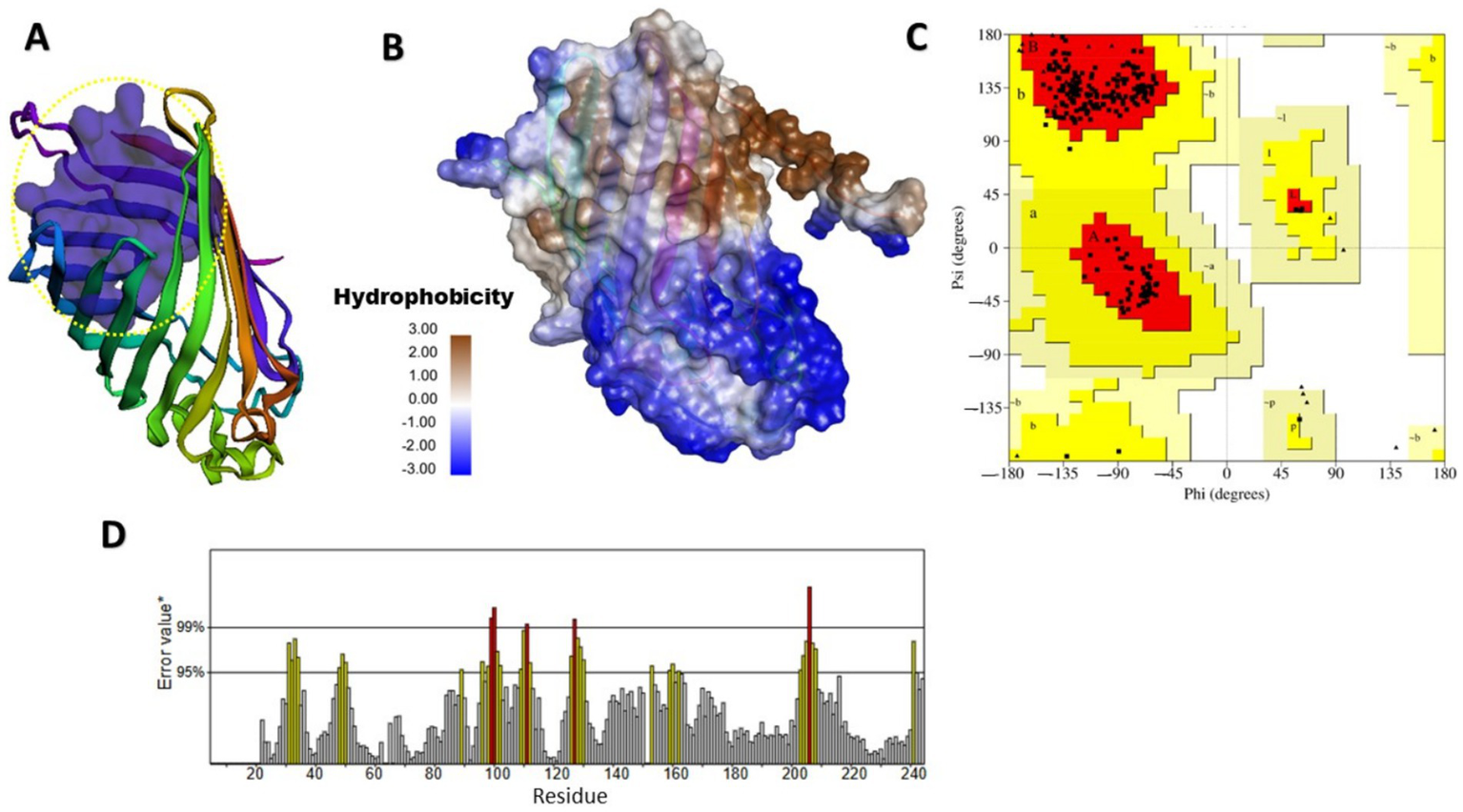

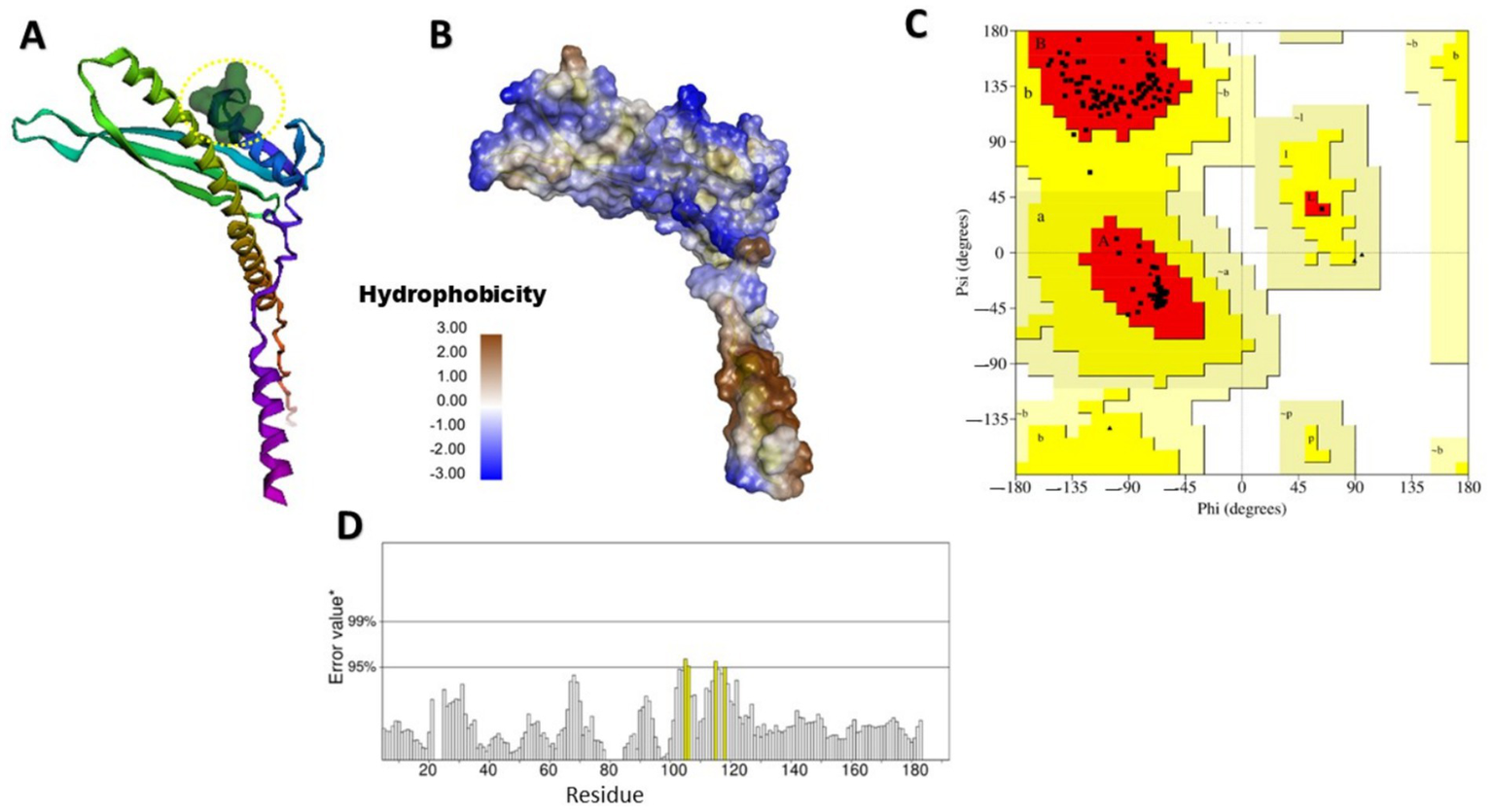

The structural characteristics of the Salmonella outer membrane proteins, OmpV and LptE (LPS), were predicted using AlphaFold2, with details summarized in Supplementary Table S3. OmpV and LptE proteins were modeled as monomers using the AlphaFold v2 method with a high sequence identity (99.60 and 99.49%) respectively, and full coverage (1.00) with their respective templates. Sequence similarity values were 0.63 for OmpV and 0.60 for LPS, indicating strong conservation. The Global Model Quality Estimation (GMQE) scores were 0.79 for OmpV and 0.88 for LPS, supporting the reliability of the predicted models for subsequent structural and functional analyses for further computational analyses. Following refinement, the quality of the OmpV and LPS protein models was assessed (Supplementary Figure S5; Supplementary Tables S4, S5). Based on comprehensive evaluation of GDT-HA, RMSD, MolProbity, clash score, poor rotamers, and Ramachandran favored regions (over 97% residues in core regions), model 3 was selected for OmpV, and model 5 for LPS, as they demonstrated the most balanced and optimal structural characteristics, and confirm the high quality and reliability of these models.

Finding specific binding sites on target proteins is crucial for designing small-molecule drugs. Figures 2, 3 illustrate the predicted and structural quality assessment for OmpV and LPS proteins, respectively, identified using FPocketWeb 1.0.1. Analysis of these pockets (Supplementary Tables S7,S8) revealed that OmpV has a druggable pocket (0.998), while LPS possesses (0.758) respectively. Further validation with PROCHECK (Supplementary Tables S6,S7) confirmed the excellent stereochemical quality of both refined models, with over 97% of residues in core Ramachandran regions and no bad contacts, confirming their suitability for molecular docking studies. FPOCKETWEB analysis showed that both Ompv and LPS proteins have druggable pockets, scoring 0.998 and 0.758, respectively.

Figure 2

Modeled and structural quality assessment of MipA/OmpV family protein. (A) Identification of a rigid, exclusively apolar druggable pocket (Score: 0.998) in OmpV and hydrophobicity (score: 12.839) for lipid-Based ligand binding (Yellow dashed circular); (B) Hydrophobicity; (C) Ramachandran plot analysis, created using SAVES v6.1 web tool; (D) OmpV protein ERRAT evaluation obtained from the SAVES v6.1 web tool.

Figure 3

Modeled and structural quality assessment of LPS-assembly lipoprotein LptE. (A) Identification of a rigid, exclusively apolar druggable pocket (Score: 0.758) in LPS and hydrophobicity (score: −20.00) for lipid-Based ligand binding (Yellow dashed circular); (B) Hydrophobicity; (C) Ramachandran plot analysis, created using SAVES v6.1 web tool; (D) LPS protein ERRAT evaluation obtained from the SAVES v6.1 web tool.

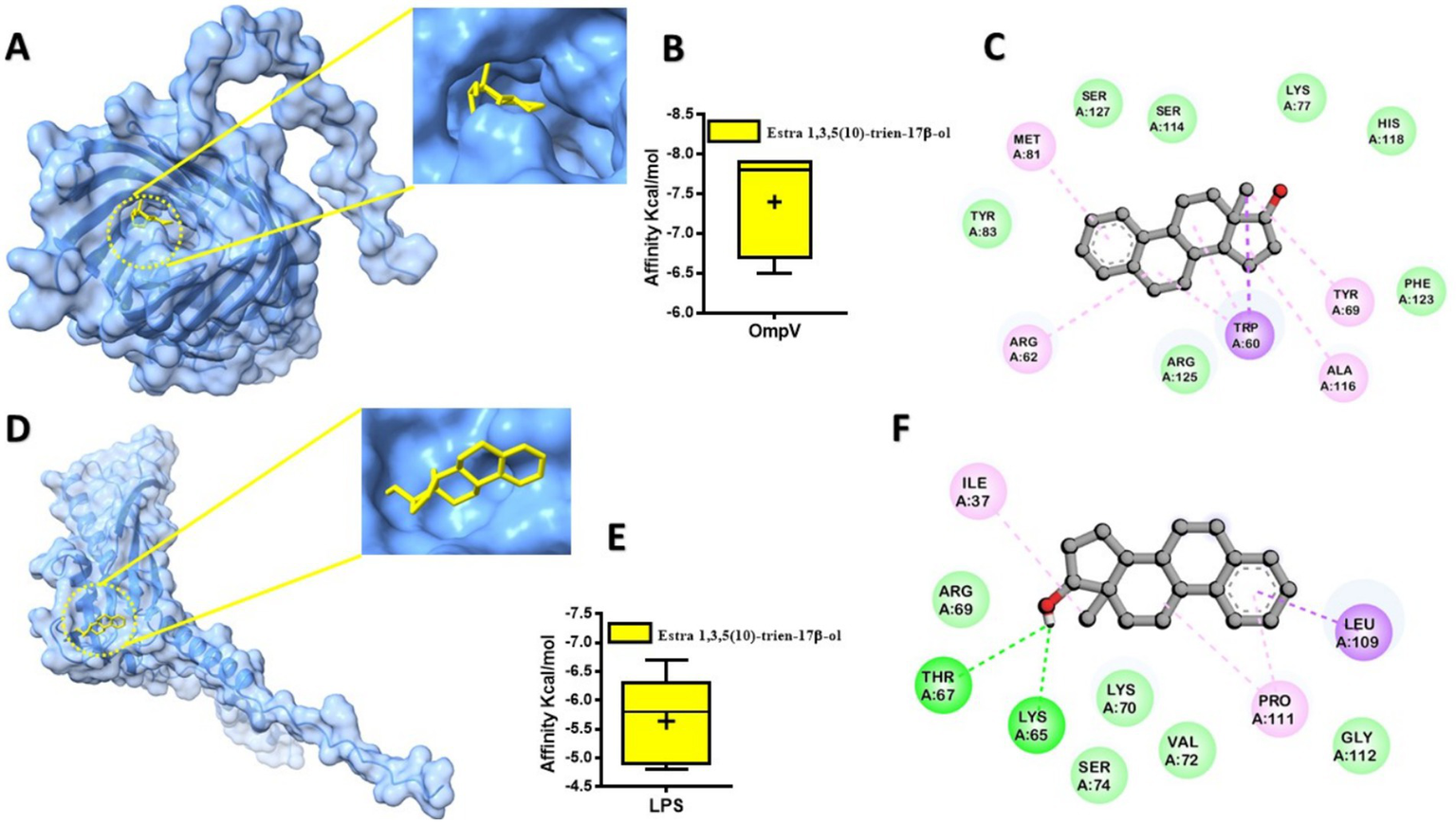

Molecular docking simulations were performed to investigate the binding interactions between Solenostemma argel-derived compounds and the OmpV and LPS proteins, with binding affinities summarized in Table 7. Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol (Compound No. 3) emerged as the most promising candidate, exhibiting the highest binding affinities of −7.9 kcal/mol (estimated Ki = 1.65 μM) for OmpV and −6.7 kcal/mol (estimated Ki = 12.0 μM) for LPS. The lower Ki value for OmpV suggests a stronger potential inhibition of this outer membrane protein. Other compounds also showed notable binding, with Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- and Phytol both achieving −6.6 kcal/mol against OmpV, and 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy- showing −5.1 kcal/mol against LPS. Figure 4 visually represents these interactions, showing the docked conformation of Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol within the binding pockets of OmpV (Figure 4A) and LPS (Figure 4D). The corresponding box plots (Figure 4B for OmpV and Figure 4E for LPS) illustrate a relatively tight distribution of predicted binding affinity scores, indicating consistent and stable binding poses. Furthermore, 2D interaction maps (Figures 4C,F) detail the key amino acid residues involved in the interactions of Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol with OmpV and LPS, respectively. LptE, on the other hand, is essential for the proper assembly of LPS in the outer membrane, which is vital for maintaining membrane integrity and facilitating LPS transport (19), making them attractive antibacterial targets. Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol demonstrates binding affinity to both OmpV and LPS suggests could has a potential mechanism for disrupting the outer membrane defense systems in Salmonella species. Computational docking analyses further elucidated that these interactions are stabilized by the formation of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic region with amino acid residues within the binding sites. In particular, it has been reported that compounds such as estradiol and estrogen have antimicrobial effects, including membrane-targeting activity in P. aeruginosa biofilm structure (51), possibly interfere with bilayers or interfering with efflux and transport proteins. The double dubious capacity seen in this study highlights the ability of the connection for multi-scarcity bans, which can help reduce bacterial resistance development. However, further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to confirm its efficacy.

Table 7

| Compound name | OmpV* | LPS** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcal/mol | μM | kcal/mol | μM | |

| 1,3-Dioxane | −3.5 | 2709.7 | −3.3 | 3798.5 |

| Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- | −6.6 | 14.4 | −5.4 | 109.5 |

| Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol | −7.9 | 1.6 | −6.7 | 12.2 |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy- | −4.9 | 254.7 | −5.1 | 181.7 |

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | −5 | 215.2 | −4.2 | 830.8 |

| Phytol | −6.6 | 14.4 | −5.5 | 92.5 |

| Oleic Acid | −5.6 | 78.1 | −4.4 | 592.7 |

| 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol | −5.5 | 92.5 | −4.5 | 500.6 |

| 2-Furancarboxaldehyde, 5-(hydroxymethyl)- | −4.6 | 422. 8 | −4.1 | 983.7 |

| 2-[2-[2-[2-(2-Acetyloxyethoxy)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethanol | −4.5 | 500.6 | −3.9 | 1378.9 |

| 2-Acetylamino-3-hydroxy-propionic acid | −4.8 | 301.6 | −4.5 | 500.6 |

| (E)-Stilbene | −6.8 | 10.3 | −5.2 | 153.5 |

| 12-Octadecadienoyl chloride, (Z, Z)- | −6 | 39.7 | −4.9 | 254.7 |

| 2-Propanol, 1-(1-methylethoxy)- | −4.1 | 983.7 | −3.8 | 1632.7 |

| 2-Methyl-Z, Z, Z-3,13-octadecadienol | −5.8 | 55.7 | −4 | 1164.7 |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid | −5.7 | 65.9 | −4 | 1164.7 |

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid | −6.1 | 33.6 | −4.7 | 357.1 |

| Pentanoic acid, 3-methyl-, methyl ester | −4.5 | 500.6 | −4.3 | 701.7 |

| 6-Methyl-2,3-dihydro-pyran-2,4-dione | −4.8 | 301.6 | −5.1 | 181.7 |

Molecular docking scores (ΔG) and estimated inhibition constants (Ki) of S. argel-derived compounds.

MipA/OmpV family protein; *OmpV: Outer membrane protein V. **LPS-assembly lipoprotein LptE. Ki values were calculated from the docking scores (ΔG) using the equation Ki = exp.(ΔG/RT), where R = 1.987 × 10−3 kcal·mol−1·K−1 and T = 298.15 K. Ki values are reported in micromolar (μM).

Figure 4

Predicted protein-ligand interaction. The docked compounds are shown in a stick model, colored yellow. (A)A modeled in OmpV docked with Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol; (B)box plot represented binding affinity scores from computational predictions of Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol’s interaction with OmpV protein.; (C)2D interaction of ligand with key residues; (D) human LPS docked with Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol; (E)box plot represented binding affinity scores from computational predictions of Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol’s interaction with LPS protein; (F)2D interaction of ligand with key residues. With the box plot showing a relatively tight distribution of predicted poses around this value.

Studies on S. argel have shown antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities. Here is not much direct proof that Estra-1,3,5(10)-trien-17β-ol works against Salmonella or interacts with OmpV/LPS, but its steroidal structure, which is similar to estrogen, suggests that it could have a wide range of biological effects.

3.5 Limitations of the study

While this study provides a quantitative baseline for the anti-Salmonella activity of S. argel methanolic leaf extract, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the work was conducted exclusively in vitro, relying on disc diffusion and microdilution assays. Consequently, the results do not demonstrate whether the extract retains activity under more complex conditions such as real food matrices (for example, chicken meat during refrigeration) or in vivo environments such as the animal or human gastrointestinal tract. Stability of the active compounds, their potential sensory impacts, and interactions with food components were not assessed, and these factors are critical for practical application in food safety. Second, the phytochemical characterization was restricted to GC–MS profiling, which primarily captures volatile and semi-volatile constituents. Non-volatile but potentially bioactive metabolites such as polyphenols, alkaloids, or glycosides may have been overlooked, limiting the comprehensiveness of the chemical analysis. Third, all assays were performed with crude methanolic extract; the reported MIC and MBC values therefore reflect the combined action of multiple constituents and do not allow identification of specific active principles or potential synergistic effects. Fourth, the microbiological panel was relatively limited, comprising only three Salmonella enterica isolates, which restricts generalization across diverse serovars and clinically relevant resistant strains. Finally, the in-silico component relied on homology modelling and docking predictions, which are valuable for hypothesis generation but cannot confirm biochemical binding or functional inhibition without experimental validation.

It is also important to note that some compounds detected in the GC–MS analysis, such as 1,3-dioxane (14.07%), are highly likely to represent contaminants introduced from organic solvents or plasticware rather than authentic plant-derived metabolites. Similarly, signals corresponding to compounds such as 2-[2-[2-(2-acetyloxyethoxy) ethoxy] ethoxy] ethanol are suspected to have originated from laboratory consumables or leaching during storage in plastic containers. Because we did not carry out complementary confirmatory analyses (for example, LC–MS/MS with authentic standards or alternative extraction and storage conditions), we cannot fully exclude the contribution of such artifacts. Recognizing this limitation is critical to avoid overinterpretation of the GC–MS data. We therefore recommend that future investigations incorporate rigorous contamination controls, use glassware and solvent blanks, and apply orthogonal analytical techniques to distinguish genuine phytochemicals from external impurities. Addressing this point will ensure greater accuracy in the phytochemical profiling of S. argel and strengthen the reliability of subsequent bioactivity correlations.

3.6 Future perspectives

To translate these preliminary findings into validated antimicrobial leads and practical interventions, a staged, mechanistic program of work is recommended. The immediate priority should be bioactivity-guided fractionation of the methanolic extract (liquid–liquid partitioning followed by chromatographic separation) to isolate and structurally characterize the compounds responsible for antibacterial activity; identities must be confirmed by LC–MS/MS and NMR. Concurrently, focused mechanistic assays are needed to test the membrane-targeting hypothesis suggested by GC–MS and docking: these should include membrane-integrity assays (e.g., propidium iodide uptake, membrane potential probes), LPS-interaction or displacement assays, and efflux-pump activity measurements. Given the public-health importance of antibiotic resistance, systematically testing synergy with frontline antibiotics (FICI determinations for ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, ampicillin, and others) will establish whether S. argel fractions can potentiate existing drugs or mitigate resistance. Target validation should move beyond docking to biochemical and biophysical binding assays (for example, SPR or ITC) using recombinant outer-membrane proteins prioritized by in silico screens. Once active fractions or pure compounds are identified, in vivo evaluation in an appropriate Salmonella infection model (avian or murine, depending on the intended application) is essential to characterize efficacy, dosing, and safety; standard toxicology panels and histopathology must accompany these studies. Finally, because solvent selection and extraction methodology strongly influence phytochemical yield and bioactivity, parallel optimization of extraction (testing solvents such as ethyl acetate, diethyl ether, and supercritical CO₂) should be performed to maximize recovery of potent constituents and to develop reproducible preparations suitable for downstream formulation and scale-up.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the methanolic leaf extract of Solenostemma argel exhibits moderate in vitro activity against the tested Salmonella strains. The GC–MS profile, rich in phenolic constituents and fatty-acid derivatives, lends phytochemical support to the plant’s ethnobotanical use and suggests mechanisms consistent with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects. Because the traditional use of S. argel for abdominal complaints may not reflect direct antibacterial action alone, our findings underscore the need to evaluate other physiological and host-directed effects and to test efficacy in appropriate in vivo models. Importantly, antibacterial principals may be polar and therefore poorly recovered by the present methanolic protocol; consequently, systematic studies using alternative solvents and extraction techniques are warranted. The detection of possible analytical artifacts also highlights the necessity of rigorous sample handling and orthogonal compound confirmation (LC–MS/MS, NMR). Ultimately, bioactivity-guided isolation and structural characterization of individual compounds, followed by mechanistic and in vivo validation, will be essential to determine the true therapeutic potential of S. argel and to explore its promise as a source of novel anti-Salmonella agents for food-safety applications, particularly in poultry production.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because Ethical approval was not required as this study utilized bacterial isolates obtained from commercially purchased, Slaughtered chilled chicken meat. No live animals were involved in the research. Written informed consent was not obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study because Informed consent was not applicable for this study. Bacterial isolates were obtained from chilled chicken meat purchased randomly from various commercial retailers. The samples were standard food commodities, not obtained from any private animal owners or farms, making consent unnecessary.

Author contributions

AA: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. MD: Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Writing – original draft. HI: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MA: Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing. EA: Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2501).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI tools were utilized solely for language refinement and proofreading. All concepts, analyses, and interpretations presented in this manuscript are entirely our original work.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1694017/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1.^ https://tox.charite.de/protox3/

3.^ https://swissmodel.expasy.org/

References

1.

Fung F Wang H-S Menon S . Food safety in the 21st century. Biom J. (2018) 41:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2018.03.003

2.

Mohammad A-M Chowdhury T Biswas B Absar N . Food poisoning and intoxication: a global leading concern for human health. In: Grumezescu AM, Holban AM, editors. Food safety and preservation. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press, Elsevier (2018). 307–52.

3.

Abebe E Gugsa G Ahmed M . Review on major food-borne zoonotic bacterial pathogens. J Trop Med. (2020) 2020:4674235. doi: 10.1155/2020/4674235

4.

Ishaq A Manzoor M Hussain A Altaf J Rehman Su Javed Z et al . Prospect of microbial food borne diseases in Pakistan: a review. Braz J Biol. (2021) 81:940–53. doi: 10.1590/1519-6984.232466

5.

Ehuwa O Jaiswal AK Jaiswal S . Salmonella, food safety and food handling practices. Foods. (2021) 10:907. doi: 10.3390/foods10050907

6.

Majowicz SE Musto J Scallan E Angulo FJ Kirk M O'Brien SJ et al . The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis. (2010) 50:882–9. doi: 10.1086/650733

7.

Nair A Balasaravanan T Malik S Mohan V Kumar M Vergis J et al . Isolation and identification of Salmonella from diarrheagenic infants and young animals, sewage waste and fresh vegetables. Vet World. (2015) 8:669–73. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2015.669-673

8.

Ramos J García-Corbeira P Aguado J Alés J Soriano F . Classifying extraintestinal non-typhoid Salmonella infections. QJM. (1996) 89:123–6. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.2.123

9.

Moraes DMC Almeida AMDS Andrade MA Nascente E Duarte S Nunes I et al . Antibiotic resistance profile of Salmonella Sp. isolates from commercial laying hen farms in Central-Western Brazil. Microorganisms. (2024) 12:669. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12040669

10.

Marchello CS Carr SD Crump JA . A systematic review on antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella typhi worldwide. Am J Trop Med Hyg. (2020) 103:2518–27. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0258

11.

Dudhane RA Bankar NJ Shelke YP Badge AK Badge A . The rise of non-typhoidal Salmonella infections in India: causes, symptoms, and prevention. Cureus. (2023) 15:46699. doi: 10.7759/cureus.46699

12.

Sarré FB Dièye Y Seck AM Fall C Dieng M . High level of Salmonella contamination of leafy vegetables sold around the Niayes zone of Senegal. Horticulturae. (2023) 9:97. doi: 10.3390/horticulturae9010097

13.

Manyi-Loh C Mamphweli S Meyer E Okoh A . Antibiotic use in agriculture and its consequential resistance in environmental sources: potential public health implications. Molecules. (2018) 23:795. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040795

14.

Sagar P Aseem A Banjara SK Veleri S . The role of food chain in antimicrobial resistance spread and one health approach to reduce risks. Int J Food Microbiol. (2023) 391:110148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2023.110148

15.

Liu Q. Yi J. Liang K. Zhang X. Liu Q. Outer membrane vesicles derived from Salmonella enteritidis protect against the virulent wild-type strain infection in a mouse model. J Microbiol Biotechnol. (2017) 27:1519–28. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1705.05028

16.

Roy Chowdhury A Sah S Varshney U Chakravortty D . Salmonella Typhimurium outer membrane protein a (OmpA) renders protection from nitrosative stress of macrophages by maintaining the stability of bacterial outer membrane. PLoS Pathog. (2022) 18:e1010708. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010708

17.

Chimalakonda G Ruiz N Chng S-S Garner RA Kahne D Silhavy TJ . Lipoprotein LptE is required for the assembly of LptD by the β-barrel assembly machine in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:2492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019089108

18.

Ruiz N Chng S-S Hiniker A Kahne D Silhavy TJ . Nonconsecutive disulfide bond formation in an essential integral outer membrane protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2010) 107:12245–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007319107

19.

Malojčić G Andres D Grabowicz M George AH Ruiz N Silhavy TJ et al . LptE binds to and alters the physical state of LPS to catalyze its assembly at the cell surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2014) 111:9467–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402746111

20.

Abdel-sattar E El-Shiekh RA . A comprehensive review on Solenostemma argel (Del.) Hayne, an Egyptian medicinal plant. Bull Fac Pharm Cairo Univ. (2024) 62:1050. doi: 10.54634/2090-9101.1050

21.

Ahmed IAM Alqah HAS Saleh A Al-Juhaimi FY Babiker EE Ghafoor K et al . Physicochemical quality attributes and antioxidant properties of set-type yogurt fortified with argel (Solenostemma argel Hayne) leaf extract. LWT Food Sci Technol. (2021) 137:110389. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110389

22.

Teia FKF . A review of Solennostemma argel: phytochemical, pharmacological activities and agricultural applications. J Ayurvedic Herb Med. (2018) 4:99–101. doi: 10.31254/jahm.2018.4211

23.

Farah A.A. Ahmed E.H. (2017). Beneficial antibacterial, antifungal and anti-insecticidal effects of ethanolic extract of Solenostemma argel leaves. Mediterranean J Biosci.1:184–191.

24.

Osman H Shayoub MEH Babiker EM Elhag MM Osman HM . The effect of ethanolic leaves extract of Solenostemma argel on blood electrolytes and biochemical constituents of albino rats. Sudan J Sci. (2015) 6:48–52. doi: 10.53332/sjs.v6i1.384

25.

Abdallah EM . Antibacterial activity of fruit methanol extract of Ziziphus spina-christi from Sudan. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. (2017) 6:38–44. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.605.005

26.

Konappa N Udayashankar AC Krishnamurthy S Pradeep CK Chowdappa S Jogaiah S . GC–MS analysis of phytoconstituents from Amomum nilgiricum and molecular docking interactions of bioactive serverogenin acetate with target proteins. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:16438. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73442-0

27.

Elbehiry A Marzouk E Abalkhail A Abdelsalam MH Mostafa ME Alasiri M et al . Detection of antimicrobial resistance via state-of-the-art technologies versus conventional methods. Front Microbiol. (2025) 16:1549044. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1549044

28.

Al-Mijalli SH Mrabti HN Abdallah EM Assaggaf H Qasem A Alenazy R et al . Acorus calamus as a promising source of new antibacterial agent against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus: deciphering volatile compounds and mode of action. Microb Pathog. (2025) 200:107357. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2025.107357

29.

El Hachlafi N Mrabti HN Al-Mijalli SH Jeddi M Abdallah EM Benkhaira N et al . Antioxidant, volatile compounds; antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and dermatoprotective properties of cedrus atlantica (endl.) manetti ex carriere essential oil: in vitro and in silico investigations. Molecules. (2023) 28:5913. doi: 10.3390/molecules28155913

30.

Banerjee P Kemmler E Dunkel M Preissner R . ProTox 3.0: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. (2024) 52:W513–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae303

31.

Liu Y Yang X Gan J Chen S Xiao ZX Cao Y . CB-Dock2: improved protein–ligand blind docking by integrating cavity detection, docking and homologous template fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. (2022) 50:W159–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac394

32.

McGlynn DF Yee LD Garraffo HM Geer LY Mak TD Mirokhin YA et al . New library-based methods for nontargeted compound identification by GC-EI-MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. (2025) 36:389–99. doi: 10.1021/jasms.4c00451

33.

Nabi M Tabassum N Ganai BA . Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of Skimmia anquetilia NP Taylor and airy Shaw: a first study from Kashmir Himalaya. Front Plant Sci. (2022) 13:937946. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.937946

34.

Farag SM Essa EE Alharbi SA Alfarraj S El-Hassan GA . Agro-waste derived compounds (flax and black seed peels): toxicological effect against the West Nile virus vector, Culex pipiens L. with special reference to GC–MS analysis. Saudi J Biol Sci. (2021) 28:5261–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.05.038

35.

Lopez A Bellagamba F Moretti VM . Fatty acids. In: Toldrá F, Nollet L, editors. Handbook of seafood and seafood products analysis. Boca Raton, FL, United States: CRC Press (2024). 387–406.

36.

Mashaal K Shabbir A Shahzad M Mobashar A Akhtar T Fatima T et al . Amelioration of rheumatoid arthritis by Fragaria nubicola (wild strawberry) via attenuation of inflammatory mediators in Sprague Dawley rats. Medicina. (2023) 59:1917. doi: 10.3390/medicina59111917

37.

Salman HA Yaakop AS Al-Rimawi F Makhtar AMA Mousa M Semreen MH et al . Ephedra alte extracts' GC-MS profiles and antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens (MRSA). Heliyon. (2024) 10:e27051. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27051

38.

García M Magi MS García MC . Harnessing Phytonanotechnology to tackle neglected parasitic diseases: focus on Chagas disease and malaria. Pharmaceutics. (2025) 17:1043. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics17081043

39.

Liu J Feng X Liang L Sun L Meng D . Enzymatic biosynthesis of D-galactose derivatives: advances and perspectives. Int J Biol Macromol. (2024) 267:131518. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131518

40.

Yu Z Joossens M van den Abeele A-M Kerkhof P-J Houf K . Isolation, characterization and antibiotic resistance of Proteus mirabilis from Belgian broiler carcasses at retail and human stool. Food Microbiol. (2021) 96:103724. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103724

41.

Magiorakos AP Srinivasan A Carey RB Carmeli Y Falagas ME Falagas ME et al . Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

42.

Kebbab-Massime R Labed B Boutamine-Sahki R . Evaluation of antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of Methanolic extracts of flavonoids obtained from the leaves of Solenostemma argel plant collected in the region of Tamanrasset, Algeria. J Plant Biochem Physiol. (2017) 5:1–5. doi: 10.4172/2329-9029.1000173

43.

Ahamed NSI Kehail MAA Abdelrahim YM . The chemical composition of argel (Solenostemma argel) and black seeds (Nigella sativa) and their antibacterial activities. Int J Front Sci Technol Res. (2022) 3:52–56. doi: 10.53294/ijfstr.2022.3.2.0057

44.

Sharaf SMA Ali HTA Salah MG Kamel Z . Antibacterial activity of Solenostemma argel extracts against extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Egypt J Med Microbiol. (2024) 33:1–8. doi: 10.21608/ejmm.2024.313255.1309

45.

Abdallah EM . Antibacterial activity of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. calyces against hospital isolates of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Acute Dis. (2016) 5:512–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joad.2016.08.024

46.

Mogana R Adhikari A Tzar MN Ramliza R Wiart CJBCM . Antibacterial activities of the extracts, fractions and isolated compounds from Canarium patentinervium Miq. Against bacterial clinical isolates. BMC Complement Med Ther. (2020) 20:55. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-2837-5

47.

Sulieman A Elzobair WM Abdel-Rahim AM . Antimicrobial activity of the extract of solenostemma argel (harjal) plant. J Sci Technol. (2009) 10:120–34.

48.

Mumbo MT Nyaboga EN Kinyua JK Muge EK Mathenge SG Rotich H et al . Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Salmonella spp. and Escherichia coli isolated from fresh Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fish marketed for human consumption. BMC Microbiol. (2023) 23:306. doi: 10.1186/s12866-023-03049-8

49.

Alvarado-Martinez Z Bravo P Kennedy NF Krishna M Hussain S Young AC et al . Antimicrobial and antivirulence impacts of phenolics on Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. Antibiotics. (2020) 9:668. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9100668

50.

Obukhova ES Murzina SA . Mechanisms of the antimicrobial action of fatty acids: a review. Appl Biochem Microbiol. (2024) 60:1035–43. doi: 10.1134/S0003683824605158

51.

Al-Zawity J Afzal F Awan A Nordhoff D Kleimann A Wesner D et al . Effects of the sex steroid hormone estradiol on biofilm growth of cystic fibrosis Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2022) 12:941014. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.941014

Summary

Keywords

secondary metabolites, antibacterial activity, plants, natural products, computational biology, food-safety, poultry

Citation

Alhudhaibi AM, Dahab M, Idriss H, Almoteri MF and Abdallah EM (2025) Antibacterial properties of Solenostemma argel (Del.) Hayne against Salmonella strains from chicken meat: integrated GC–MS phytochemical profiling and molecular docking analysis. Front. Nutr. 12:1694017. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1694017

Received

27 August 2025

Accepted

14 October 2025

Published

29 October 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Yuan Su, The University of Tennessee Knoxville United States

Reviewed by

Zhiyong Wu, Northeast Agricultural University, China

Othman El Faqer, Hassan II University of Casablanca, Morocco

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Alhudhaibi, Dahab, Idriss, Almoteri and Abdallah.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Abdulrahman Mohammed Alhudhaibi, amalhudhaibi@imamu.edu.sa; Emad M. Abdallah, 140208@qu.edu.sa

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.