- 1Clinical Biochemistry Department, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Food, Nutrition, and Lifestyle Research Unit, King Fahd for Medical Research Centre, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 3Physiological Sciences Department, Fakeeh College for Medical Sciences, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 4King Fahd Medical Research Center, Regenerative Medicine Unit, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 5Medical Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

- 6Mansoura-Manchester Medical Program for Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt

- 7Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

This review aimed to investigate the relationship between endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, insulin resistance, and the potential mitigating effects of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet, Ketogenic diet (LCHF-KD). A detailed literature search using databases to achieve a comprehensive overview. The keywords of the search were “endoplasmic reticulum stress,” “insulin resistance,” “metabolic syndrome,” and “low carbohydrate-high fat diet, molecular mechanism, Biochemical effects, Metabolic effects, Signaling pathways.” Insulin resistance is a metabolic disorder characterized by decreased cell sensitivity to insulin, resulting from the interplay between genetic and environmental factors. It can act as both a result and trigger of uncontrolled endoplasmic reticulum stress. This condition is associated with several disruptions, including impaired endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial transport, disordered signaling pathways, macrophage dysfunction, autophagy, immune function, inflammatory responses, dysregulation of antioxidant responses, and altered expression of genes involved in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. LCHF-KD has been shown to alleviate insulin resistance associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Finally, it is concluded that ER stress plays a crucial role in the development of insulin resistance and metabolic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and obesity. Therapeutic strategies, including chemical chaperones and unfolding protein response (UPR) modulators, were used to alleviate ER stress. Dietary interventions, such as the low-carbohydrate, high-fat ketogenic diet (LCHF-KD), also reduce ER stress and improve metabolic health by modulating inflammation and oxidative stress. Combining these with conventional dietary therapies and personalized medicine approaches may enhance treatment outcomes and prevent the progression of metabolic disorders.

Introduction

Insulin resistance (IR) is a pathological condition characterized by the diminished ability of cells to uptake glucose in response to insulin (1). IR is characterized by combined hyperinsulinemia and chronic hyperglycemia and is recognized as the pathogenic mechanism of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (2). Furthermore, IR is linked to metabolic syndrome. The Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) of the National Cholesterol Education Program defines metabolic syndrome as the presence of three or more of the following five specific clinical criteria. These include abdominal obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, reduced HDL cholesterol, hypertension, and hyperglycemia. This definition underscores the role of insulin resistance and central obesity as central features of metabolic syndrome and highlights the associated risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (3). The high global incidence of IR and its pathogenesis has substantial risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, underscoring its impact on morbidity and mortality (4).

The pathophysiology of IR involves complex biochemical and molecular pathways, including the impairment of insulin receptor signaling (5), alterations in glucose transporter (GLUT) expression (6), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, and chronic inflammation (7). Beyond impaired glucose homeostasis, IR also causes abnormalities in lipid metabolism. It exacerbates dyslipidemia by increasing plasma-free fatty acids, hypertriglyceridemia, and the formation of small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (sdLDL-C), which contributes to the development of atherosclerosis (8).

The Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) is the largest organelle of the eukaryotic cell and is central for protein folding, maturation, and trafficking (9). Under conditions of cellular stress, the amount of newly synthesized proteins decreased to allow time for protein folding in the ER. This folding delay can lead to the accumulation of misfolded and unfolded proteins within the ER lumen, a phenomenon known as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (9). In response, several signaling pathways are activated collectively as the unfolded protein response (UPR), which aims to restore endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis by enhancing protein folding capacity, decreasing protein synthesis, and degrading misfolded proteins (10, 11).

Chronic ER stress is associated with the development of a variety of pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative diseases (12), cancer (13), and metabolic disorders (14). In particular, ER stress interferes with insulin signaling pathways, contributing to the development of metabolic diseases and insulin resistance (15, 16).

The low-carb, high-fat diet (LCHF), commonly known as the ketogenic diet (KD), is adopted for its distinctive approach to weight loss and health enhancement. The low-carb, high-fat ketogenic diet (LCHF-KD) is characterized by its low-carbohydrate, high-fat, and moderate-protein composition. Typically, carbohydrates provide less than 10% of total energy intake, fats contribute approximately 70–75%, and proteins account for about 15–20%. This macronutrient distribution promotes a metabolic shift from glucose to fat utilization, leading to increased ketone body production and improved metabolic flexibility (17). The underlying rationale behind the ketogenic diet is its ability to shift the body’s primary energy source from glucose, derived from carbohydrates, to ketones, which are produced through the oxidation of fat. This metabolic adaptation takes several days to weeks. During this period, the body undergoes considerable modifications in its energy metabolism (18).

The LCHF-KD offers several health benefits, including weight loss, improved glycemic control, and enhanced neurological function, particularly in conditions such as epilepsy, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. These health benefits are mainly attributed to the neuroprotective properties of ketone bodies (19). The LCHF-KD is a potential intervention to improve insulin resistance (20) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (21). The impact of the LCHF-KD on ER stress and insulin resistance is based on the alteration of substrate availability and utilization that, in turn, alleviates ER stress and enhances insulin signaling pathways (20, 21). Moreover, ketone bodies generated during the LCHF-KD exhibit anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, which improve mitochondrial function and thereby reduce ER stress while enhancing insulin sensitivity (22).

Despite significant progress in understanding the complex relationship between ER stress and insulin resistance (IR), many aspects remain unclear. Critical unanswered questions involve identifying the specific molecular triggers of ER stress in insulin-dependent tissues and understanding how these triggers differ among individuals with varying genetic backgrounds and lifestyles. Additionally, the effects of particular nutrients versus overall dietary patterns on ER stress and insulin resistance are not fully understood, indicating a need for more detailed research into how individual dietary components impact these pathways, particularly LCHF-KD. Furthermore, there is a significant gap in understanding the variability in susceptibility to insulin resistance and related metabolic disorders in response to ER stress, as well as the influence of genetic factors, epigenetic changes, and differences in microbiome composition. So, the primary research question for this review is: “How does ER stress contribute to insulin resistance in metabolic syndromes, and can LCFH-KD mitigate these effects?

This review article aims to provide a comprehensive examination of the role of ER stress in the development and progression of IR, with a particular focus on the underlying molecular mechanisms that link ER stress to impaired insulin signaling. It explores how ER stress contributes to metabolic dysfunctions commonly observed in insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and their related comorbidities. Moreover, the review critically evaluates the potential protective effects of a LCHF-KD in mitigating ER stress-induced insulin resistance. By synthesizing evidence from experimental and clinical studies, it investigates how alterations in dietary composition, specifically carbohydrate restriction and increased fat intake, can influence ER stress responses and thereby enhance insulin sensitivity. This integrated analysis underscores the importance of nutritional interventions in modulating cellular stress mechanisms and enhancing metabolic outcomes. Furthermore, this review contributes to the evolving fields of nutrition, metabolism, and personalized medicine by providing insights that support the development of personalized dietary strategies for preventing and managing insulin resistance and associated metabolic disorders.

Methods

In this scoping review, we aimed to investigate the relationship between endoplasmic reticulum stress, insulin resistance, and the potential mitigating effects of a LCHF-KD. The authors conducted a comprehensive literature search using databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar to gain a detailed overview. The keywords of the search were “endoplasmic reticulum stress,” “insulin resistance,” “metabolic syndrome,” and “low carbohydrate-high fat diet, molecular mechanism, Biochemical effects, Metabolic effects, Signaling pathways.” The search included peer-reviewed research articles published within the last 20 years (2005–2025) to ensure the inclusion of the most current data.

The inclusion criteria encompass randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, experimental animal studies, and cross-sectional studies that investigate the interplay between ER stress and insulin resistance in IR- related conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Research investigating the impact of dietary interventions, specifically LCHF-KD intake, was also included. Only peer-reviewed articles published in English are used in the current review to ensure scientific validity. In contrast, our exclusion criteria included reviews, opinion pieces, editorials, and non-empirical reports that do not contribute original data. Studies that did not focus on the impact of LCHF-KD or addressed other dietary interventions were also excluded, as were those carried out exclusively on animal models with no clinical implications.

The selection of articles involved a two-step process: an initial screening of titles and abstracts to discard studies that did not meet the criteria, followed by a thorough review of full texts to assess their relevance based on predefined inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and information collection, including publication year, methodology, and key findings related to our research question, were conducted and analyzed to assess the relationship between ER stress and metabolic health outcomes, particularly in the context of LCHF-KD interventions. Then, the results from the various studies were integrated to outline the connections between ER stress, insulin resistance, and the effects of LCHF-KD.

The current scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines (23). A standardized data charting tool was employed to extract essential information from each study, including study design, participant characteristics, interventions or exposures, outcomes, and key results. Data extraction was independently conducted by two authors, with any disagreements resolved through discussion. The results were synthesized through narrative analysis to identify existing patterns and gaps in the literature. Since the review was based exclusively on previously published studies and did not involve the use of individual patient data, ethical approval was not required under institutional policies. The PRISMA-ScR flow chart is presented in Figure 1.

Understanding insulin resistance

IR is a metabolic disorder characterized by reduced cellular sensitivity to insulin (6). As a result of this condition, there is an inadequate response to normal insulin levels, causing a higher secretion of insulin (hyperinsulinemia) and glucose (hyperglycemia) in the bloodstream (24). Hyperinsulinemia is thus considered a compensatory mechanism for suppressed insulin action (25). IR is also characterized by insufficient insulin-mediated blood glucose regulation, dyslipidemia, and increased adipocyte lipolysis. These associated metabolic conditions are collectively known as insulin resistance syndrome or metabolic syndrome (26). Moreover, IR plays a key pathological role in many leading mortality diseases, such as T2DM, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases (27). Figure 2 demonstrates the most common chronic metabolic diseases that IR may induce.

Figure 2. Chronic metabolic diseases may be induced by insulin resistance, created in BioRender. Eldakhakhny, B. (2025), https://BioRender.com/r39m848.

The pathogenesis of insulin resistance

The pathogenesis of IR mainly results from the interaction between genetic/hereditary and environmental factors. This interaction disrupts internal environment homeostasis, exhibiting as chronic subclinical inflammation, persistent hypoxia, lipotoxicity, immune dysregulation, and metabolic dysfunctions (26).

Genetic/hereditary factors

The incidence of IR is frequently observed in families and certain ethnic groups, suggesting an important role for genetic and hereditary factors in the development of this condition. However, the complete genetic constitution of this disease has not yet been fully elucidated (28). Nevertheless, several genetic factors associated with IR have been identified, including mutations in insulin-related genes that produce mutant human insulins, genetic defects in the insulin signaling system, and genetic defects related to substance metabolism (29). The most common genetic mutations and their associations are listed in Table 1.

Environmental, health, and lifestyle factors

Besides genetic factors, several interconnected environmental and lifestyle-related factors contribute to the development of insulin resistance (IR). Obesity is considered the most prominent. Central or visceral obesity impairs insulin function by disrupting glucose uptake and increasing hepatic glucose output. The accumulation of adipose tissue induces systemic insulin resistance (IR) through endocrine dysregulation and chronic inflammation. Elevated levels of free fatty acids (FFAs), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) promote insulin resistance in key metabolic tissues such as the liver, muscle, and adipose tissue (30, 31).

Conditions associated with elevated levels of insulin-antagonistic hormones—such as chronic hyperglycemia, pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly, and critical illness—can significantly aggravate IR. These physiological and pathological states are characterized by increased secretion of hormones such as glucagon, cortisol, growth hormone, catecholamines, and placental lactogen, which counteract the action of insulin. The resulting hormonal imbalance disrupts metabolic homeostasis by promoting inflammation, impairing insulin receptor signaling, and altering glucose and lipid metabolism, particularly in the liver, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle. This ultimately reduces peripheral insulin sensitivity and increases the risk of developing metabolic disorders, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (32–35).

A range of pharmacological agents has also been implicated in the development of insulin resistance. Glucocorticoids, statins, antipsychotics, immunosuppressants, and protease inhibitors impair insulin sensitivity by interfering with insulin signaling, generating oxidative stress, or modulating metabolic pathways (33).

Additionally, aging is associated with reduced insulin secretion, impaired glucose tolerance, and a progressive decline in insulin sensitivity. Age-related factors, including sarcopenia, central adiposity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress, contribute to these effects. Reduced mitochondrial β-oxidation and lower glycolytic enzyme levels in muscle and liver tissues further exacerbate IR in elderly individuals (36, 37).

Table 2 provides a concise overview of various health and lifestyle factors contributing to IR’s development. These include central obesity, the impact of diseases, medications, and aging on IR. It highlights the interplay between metabolic changes, such as chronic hyperglycemia, and the persistent use of specific drugs like glucocorticoids and statins. Additionally, it lists physiological changes associated with aging, including mitochondrial dysfunction and increased adiposity.

Table 2. The most common environmental factors and their associations with the development of insulin resistance.

Cellular organelle interactions and vesicle-mediated communication in stress responses: implications for the development of insulin resistance

The complex interactions between cellular organelles are essential for maintaining metabolic homeostasis, and their dysregulation plays a crucial role in the development of IR. One of the key organelles involved is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which is responsible for protein folding and calcium (Ca2+) homeostasis. When overwhelmed by misfolded proteins or calcium imbalance, the ER initiates the unfolded protein response (UPR), a stress signaling cascade. Chronic ER stress activates inflammatory pathways, particularly the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), which impair insulin receptor signaling and contribute to peripheral and hypothalamic insulin resistance (IR) (38, 39).

Mitochondria, as the primary site of oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis, are crucial for energy-intensive processes such as insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. Impaired mitochondrial function leads to decreased ATP availability and reduced metabolic flexibility in insulin-responsive tissues, such as skeletal muscle and the liver, thereby promoting systemic IR (40). Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction is often accompanied by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). When the antioxidant regulatory system, particularly involving PGC-1α, is overwhelmed, ROS accumulation interferes with insulin receptor substrate (IRS) phosphorylation and amplifies inflammatory signaling, thereby further exacerbating insulin resistance, especially in the contexts of aging and metabolic overload (40). A closely related structure, the mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM), forms contact sites between the ER and mitochondria, playing a critical role in lipid transfer, calcium exchange, and the coordination of stress signaling. Dysfunctional MAMs impair these processes, triggering ER stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, especially in the hypothalamus, where they have been implicated in the pathogenesis of central insulin resistance (38).

Additionally, vesicle trafficking within the ER-endomembrane system, which involves transport between the ER, Golgi apparatus, and plasma membrane, is crucial for the proper localization of insulin receptors and glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4). This process relies on coat protein complexes (COPI/COPII) and SNARE-mediated vesicle fusion. Disruptions in vesicular transport can hinder insulin receptor recycling and GLUT4 translocation, thereby contributing to peripheral insulin resistance (39).

Moreover, exosome-like vesicles (ELVs), which are secreted from various cells and contain biologically active cargo such as proteins, lipids, and RNAs, serve as mediators of intercellular communication. Pathological ELVs derived from inflamed or metabolically stressed cells can impair pancreatic β-cell function or induce IR in distant tissues by delivering inflammatory or inhibitory signals (41).

Finally, broad organelle crosstalk, including dynamic interactions among the ER, mitochondria, lysosomes, and peroxisomes, is essential for nutrient sensing, redox regulation, and metabolic adaptation. Disruption of this crosstalk impairs the cellular response to metabolic demands and stress, thereby fostering the progression of insulin resistance (39). These organelle-level disruptions represent converging mechanisms that underlie the complex pathophysiology of IR across different tissues and systems.

Table 3 summarizes the fundamental roles of subcellular organelle interactions in maintaining cellular homeostasis and details how imbalances in these interactions contribute to the development of insulin resistance.

Table 3. The subcellular organelles dysfunction and its associations with the development of insulin resistance.

The intracellular stressors that contribute to the development of insulin resistance

Insulin resistance arises from complex interactions among inflammatory, metabolic, and cellular stress pathways. Key contributors include the activation of inflammatory mediators such as NF-κB, JNK, and TLR4, which impair insulin receptor substrate (IRS) signaling (42, 43). Immune cells, such as M1 macrophages and CD8+ T cells, exacerbate inflammation, whereas Tregs and M2 macrophages can enhance insulin sensitivity (44, 45). Hypoxia in adipose tissue promotes IR via HIF-1α-induced inflammation and ceramide accumulation, although muscle hypoxia may enhance GLUT4 translocation (3, 46). Lipotoxicity, triggered by excessive free fatty acids, leads to ER stress, oxidative stress, and β-cell dysfunction (47, 48). High levels of ROS activate stress kinases that disrupt insulin signaling (49, 50). Genotoxic and mitochondrial stress amplify dysfunction (51), while impaired autophagy worsens ER stress and FGF21 resistance (52, 53).

Table 4 summarizes how factors such as inflammation, hypoxia, lipotoxicity, oxidative stress, genotoxic stress, and dysregulation of apoptosis and autophagy impact key metabolic target tissues, thereby impairing the normal metabolic functions of insulin. Table 4 briefly describes the mechanisms through which these influences employ their effects, including the roles of immune cells, inflammatory pathways, and the direct impact of lipid metabolites on insulin signaling pathways.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance

As mentioned above, the ER is a central organelle in cellular physiology, playing a pivotal role in protein synthesis, lipid metabolism, and calcium storage and signaling. It is crucial for maintaining cellular function and survival under both normal and stressful conditions (54). The ER extends throughout the cytoplasm, consisting of the rough ER (rER) and smooth ER (sER). The rER, studded with ribosomes, is where the synthesis of membrane-bound and secretory proteins takes place. Meanwhile, sER lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid synthesis, metabolism, and detoxification processes (55). The ER is responsible for the proper folding and post-translational modifications of proteins, ensuring they achieve their correct three-dimensional structure and function properly. Additionally, the ER regulates intracellular calcium levels, which are critical for numerous cellular processes, including muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release, and cell death (56).

The ER is a dynamic cellular organelle whose complex activities are influenced by various internal and external factors, including low oxygen (hypoxia) or hypoglycemia levels, elevated temperature, acidosis, alterations in calcium concentration, the redox environment, and energy availability (57). These effectors can disrupt the ER’s normal functions, leading to ER stress and affecting the protein folding process within its lumen (58). Protein folding depends on the interactions among chaperone proteins, foldases, and glycosylating enzymes alongside suitable calcium levels and an oxidizing environment (59). When ER stress occurs, the protein folding process is disrupted, resulting in the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins. This ER stress triggers the unfolded protein response (UPR), a cellular mechanism and hallmark of ER stress (60).

The UPR is a cellular adaptive mechanism triggered by the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins within the ER. Under physiological conditions, the UPR restores ER homeostasis by attenuating protein synthesis, upregulating molecular chaperones, and enhancing the degradation of misfolded proteins (61, 62). Chronic activation of the UPR is a common pathology in obesity and metabolic stress (63). The chronic activation of the UPR can induce inflammation, oxidative stress, and IR (64). The UPR is mediated through three major ER stress sensors: IRE1 (inositol-requiring enzyme 1), PERK (protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase), and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6). IRE1 can activate JNK, which phosphorylates insulin receptor substrates (IRS) on serine residues, impairing insulin signaling. PERK phosphorylates eIF2α, upregulating ATF4 and CHOP, which contribute to apoptosis and β-cell dysfunction. ATF6 enhances ER chaperone expression but may also promote inflammation under prolonged stress. UPR also interacts with mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammatory pathways, amplifying metabolic derangements. Thus, while initially protective, prolonged UPR activation contributes to the development of systemic insulin resistance (65, 66).

The accumulation of unfolded, improperly folded, insoluble, and damaged proteins leads to marked impairment of cellular functions alongside proteotoxic effects that threaten cell survival. Cells defend themselves through the UPR, which plays a fundamental role in preserving intact proteins that are correctly folded and processed, thereby alleviating this threat (67). When terminally misfolded and irreparable, proteins are eliminated from the cell through one of two processes. The first is ER-associated degradation (ERAD), which transports these damaged proteins into the cytoplasm for breakdown and elimination by the proteasome. The second mechanism, aggresomal formation, occurs. This mechanism includes accumulating the damaged proteins and cellular waste into juxtanuclear complexes for recycling via autophagy (68). Closely linking autophagy to ER stress is a process known as ER-phage (69, 70).

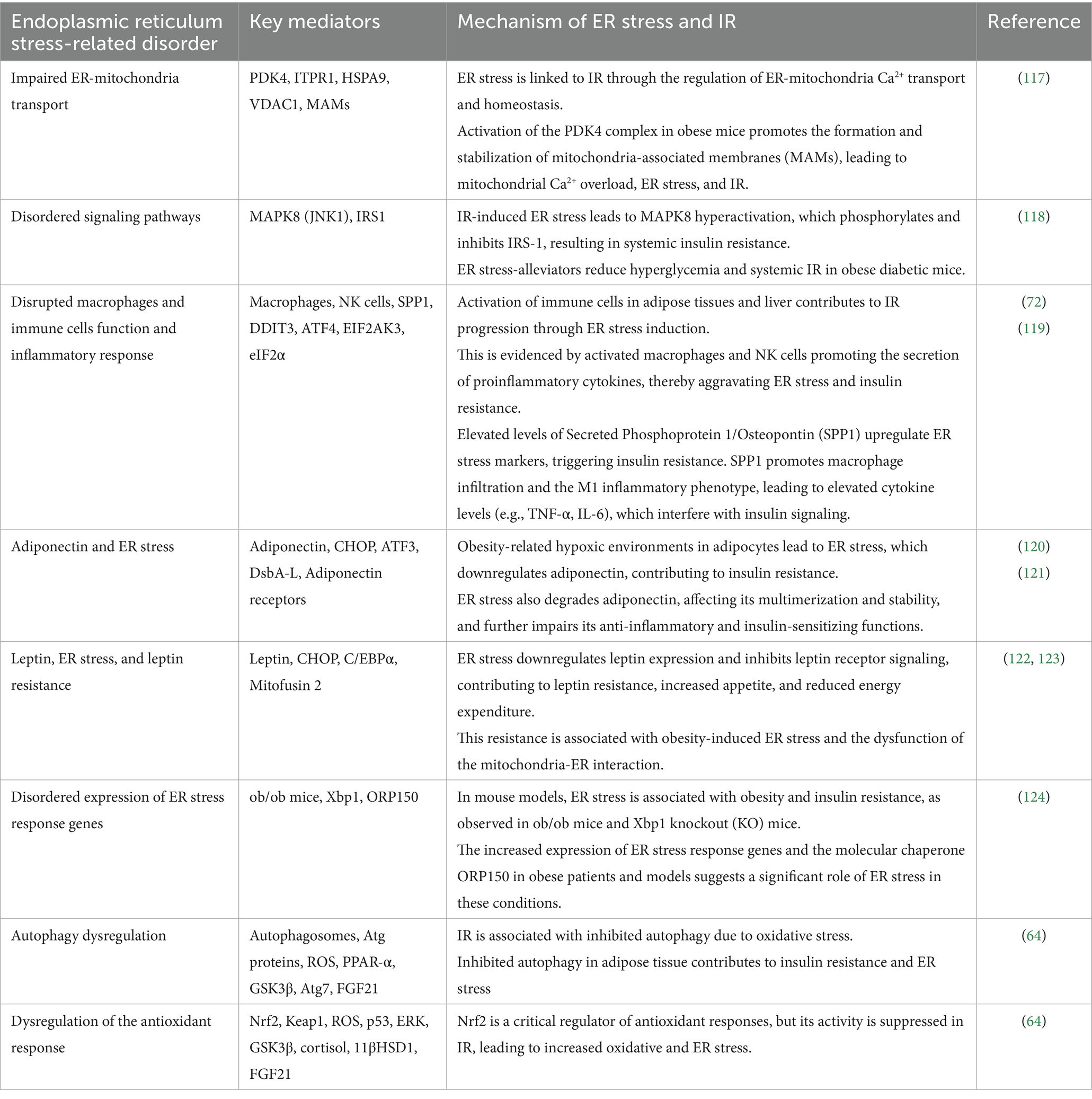

As previously noted, the ER collaborates with other subcellular organelles and plays a crucial role in protein and lipid metabolism, steroid biosynthesis, and calcium homeostasis, in addition to its primary metabolic function of protein folding. Impairment in these processes results in perturbed ER homeostasis, commonly referred to as ER stress (71). Insulin resistance can serve as both a cause and consequence of an unchecked ER stress response (72). Table 5 illustrates the various mechanisms through which insulin resistance and endoplasmic reticulum stress are interconnected.

The protective role of LCHF-KD

The ketogenic diet (KD) was introduced in the 1920s as a treatment for epilepsy. The KD is characterized by its low carbohydrate content, high fat content, and moderate protein content, aligning with the principles of fasting. Over the last decades, the application has expanded to include managing obesity and achieving quick weight loss. It has been investigated for potential other health issues such as type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, various cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases, and during pregnancy (73).

This diet regimen aims to achieve physiological ketosis, utilizing ketones as an alternative energy source to glucose. There are multiple variations of the KD, all sharing the common goal of markedly limiting carbohydrate intake. A standard ketogenic diet typically involves consuming under 50 g of carbohydrates daily, approximately 75% dietary fat, and protein intake between 1 and 1.4 g per kilogram of body weight (74). Therefore, it is referred to as a low-carbohydrate, high-fat ketogenic diet (LCHF-KD).

Restricting carbohydrate intake, which is normally the primary energy source for body tissues, leads to reduced insulin production, decreased fat storage, and increased glucose production through the process of gluconeogenesis. However, this glucose production is insufficient for the body’s needs, causing a shift in the primary energy source to fat breakdown and the production of ketone bodies (KBs) in the liver, which is the main target of the LCHF-KD. These ketone bodies can also cross the blood–brain barrier to fuel the central nervous system (21, 73, 75).

LCHF-KD also enhances fat metabolism in muscles, even in endurance athletes. Over the past four decades, various adaptations and strategies involving LCHF have been studied, including both ketogenic and non-ketogenic forms. Since 2012, research has increasingly examined the potential benefits of ketogenic LCHF-KD on endurance performance, noting significant metabolic changes and suggesting that these diets can maximize fat oxidation rates and increase ketone production, thereby providing additional energy sources for muscles and the central nervous system (74, 76).

We discussed the physiological effects of LCHF-KD in detail and published the findings in 2022 (73). The LCHF-KD exerts multiple beneficial effects across metabolic, inflammatory, mitochondrial, and epigenetic pathways. One of its primary effects is the improvement of insulin sensitivity, achieved through carbohydrate restriction, which lowers insulin secretion and mitigates hyperinsulinemia, a key driver of insulin resistance (73, 77). By stabilizing blood glucose levels, LCHF-KD also contributes to the inhibition of protein glycation. This effect reduces the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), harmful compounds implicated in diabetes-related vascular complications and atherosclerosis (73, 78).

At the mitochondrial level, LCHF-KD ameliorates dysfunction and oxidative stress by maintaining mitochondrial membrane potential and optimizing the efficiency of the electron transport chain (ETC). It also decreases the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and upregulates the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway, leading to enhanced expression of detoxifying enzymes (73, 79).

A major contributor to the anti-inflammatory effect of the ketogenic diet is β-hydroxybutyrate (ßOHB), a ketone body that inhibits inflammasome activation and crosses the blood–brain barrier to activate the HCA2 receptor, thereby reducing neuroinflammation and providing neuroprotection (73, 80). Emerging evidence also supports its role in fighting malignancy-associated features. By restricting glucose availability, LCHF-KD disrupts the Warburg effect, thereby inhibiting tumor growth. Furthermore, it enhances the efficacy of PI3K inhibitors by lowering insulin levels and preventing the reactivation of oncogenic pathways (73, 81).

In lipid metabolism, the LCHF-KD shows promise in preventing dyslipidemia by lowering triglyceride levels and shifting LDL-C particles toward larger, less atherogenic forms while maintaining or increasing HDL-C levels (73, 82).

On a molecular level, LCHF-KD impacts the epigenome by elevating intracellular adenosine levels, which inhibit DNA methylation and histone deacetylases (HDACs). This results in increased histone acetylation and modulation of gene expression, contributing to long-term metabolic and protective effects (73, 83). Moreover, the LCHF-KD diet has a positive impact on the gut microbiota, promoting beneficial species such as Akkermansia and reducing pro-inflammatory microbes. These changes reinforce the intestinal barrier, lower systemic inflammation, and improve metabolic outcomes such as insulin sensitivity (73, 84, 85).

Overall, LCHF-KD emerges as a multifaceted intervention with systemic effects that extend beyond weight loss, encompassing metabolic regulation, cellular protection, and epigenetic modulation, as summarized in Table 6. This table presents the metabolic impact of LCHF-KD and its mechanisms.

Experimental evidence on the impact of LCHF-KD on insulin resistance-related ER stress

The KD, characterized by its LCHF composition, has been extensively studied across various health contexts, including its impact on metabolic diseases, neuroprotection, and ER stress (86).

Lei et al. (87) have provided insights into how nutritional ketosis influences ER stress and its effects on insulin signaling in the liver. During early lactation, a period of negative energy balance, dairy cows often exhibit elevated levels of β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) and fatty acids, indicative of ketosis. Their study highlights that many markers exhibit a link between insulin resistance and increased activation of ER stress pathways, such as IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6. These findings are significant as they suggest a link between exacerbated ER stress and impaired liver function. Notably, the study demonstrates that inhibiting ER stress reverses these adverse effects, suggesting that targeting ER stress may mitigate hepatic insulin resistance (87) through nutritional ketosis.

In another study focusing on skeletal muscle, the effects of a KD on induced insulin resistance were analyzed, showing potential benefits in alleviating insulin resistance through ER stress modulation. In mouse muscle cells, KD reversed the activation of key ER stress markers (IRE1 and BIP) and enhanced cellular glucose uptake by improving insulin signaling. This mitigating effect was particularly evident in the restoration of the AKT/GSK3β pathway and the increase in Glut4 protein translocation to the cell membrane. These results suggest that the ketogenic diet affects liver health and skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity, at least in part, by modulating ER stress (88).

Furthermore, the KD’s role in neuroprotection, particularly concerning hypoglycemia-induced brain injury and stroke, has been demonstrated. In mice subjected to hypoglycemic conditions or stroke models, KD has been shown to exert protective effects by modifying gut microbiota, enhancing dendritic spine morphology, and reducing neuronal apoptosis. These neuroprotective effects were linked to the suppression of ER stress pathways like IRE1-XBP1 and ATF6. Additionally, in stroke models, KD inhibited the TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway, a part of the innate immune response linked to inflammation and ER stress, further underscoring the diet’s potential to mitigate ER stress and protect against neurological damage (87).

To further elucidate the role of the KD in modulating ER stress, focused on its neuroprotective effects in stroke models, a particular study investigated the influence of KD on the nucleotide-binding domain (NOD)-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, which is a critical component in the inflammatory response and has been implicated in the pathogenesis of stroke (89). Their findings demonstrated that mice on KD exhibited increased resilience against the effects of stroke. Mechanistically, KD appeared to reduce the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the brain. This reduction in NLRP3 inflammasome activity was associated with a decrease in ER stress induction. Notably, the study also highlighted the role of βOHB, a ketone body produced during ketosis, which inhibits mitochondrial dysfunction by preventing the mitochondrial translocation of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)—a process involved in mitochondrial fission and a contributor to cellular stress. Additionally, βOHB’s role in suppressing ER stress-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation emphasizes its potential as a therapeutic agent (89).

At the level of insulin resistance-related vascular pathology and endothelial dysfunction, the experimental study by Eldakhakhny et al. provides compelling evidence that a LCHF-KD diet can effectively ameliorate ERstress in the context of insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction (86). Using a dexamethasone (DEX)-induced metabolic syndrome rat model, the study divided 40 male Sprague–Dawley rats into four groups: a control group, a DEX-treated group receiving a standard diet, a DEX-treated group receiving an LCHF-KD diet, and a DEX-treated group receiving a HCLF-KD diet. The DEX-treated animals exhibited clear signs of metabolic syndrome, including increased body mass index, insulin resistance (as evidenced by elevated HOMA-IR), and histological signs of aortic endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and enhanced expression of ER stress markers, such as CHOP, PINK1, and BNIP3. Remarkably, animals in the DEX + LCHF-KD group showed significant improvements across all measured parameters. ER stress markers were downregulated to near-control levels, and ultrastructural analysis revealed the restoration of normal ER morphology, a reduction in autophagosomes, and preserved mitochondrial integrity (86). The study also demonstrated that the LCHF-KD diet decreased oxidative stress markers and normalized autophagy-related gene expression (p62, LC3, BECN-1), suggesting improved cellular homeostasis. These findings confirm that the LCHF-KD diet exerts a protective effect against insulin resistance-induced ER stress and endothelial dysfunction, underscoring its therapeutic potential as a non-pharmacological dietary strategy for managing metabolic syndrome and related vascular complications (86).

These recent studies strongly support the idea that the LCHF-KD has a beneficial role in managing ER stress across different biological systems. Whether by improving hepatic insulin sensitivity, enhancing muscle glucose uptake in insulin-resistant mice, protecting neural tissue from hypoglycemic damage and stroke, and mitigating vascular endothelial dysfunctions, LCHF-KD appears to modulate endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways effectively. These findings enhance our understanding of the ketogenic diet’s multifaceted roles in health and disease and highlight potential therapeutic targets for conditions associated with elevated endoplasmic reticulum stress. Thus, LCHF-KD offers a promising avenue for further research and therapeutic exploration.

Understanding the role of the LCHF in mitigating stress-related insulin resistance

The LCHF-KD diet has demonstrated multiple protective roles in mitigating ER stress and improving insulin sensitivity through diverse molecular mechanisms. Firstly, it reduces lipotoxicity by enhancing lipid metabolism and decreasing glucotoxicity, which is achieved through the downregulation of SREBP-1c and upregulation of PPAR-α and CPT1, promoting β-oxidation and reducing ceramide synthesis and intracellular lipid accumulation, ultimately decreasing ER burden (90–92). The LCHF-KD diet also enhances insulin sensitivity through the protective effects of βOHB, which inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome and JNK pathway and activates AMPK, thereby improving downstream insulin signaling (93). Its anti-inflammatory effects are mediated through the suppression of NF-κB and JNK pathways, reduction of TNF-α and IL-6, and inhibition of TLR4-mediated inflammatory responses, all of which contribute to improved IRS-1/Akt signaling (73, 80, 94). In terms of its antioxidant effects, the LCHF diet activates the Nrf2 pathway. It enhances the expression of antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase, thereby reducing mitochondrial ROS and lipid peroxidation and protecting the ERfrom oxidative damage (73, 95, 96). It also improves hormonal regulation, as lower insulin levels resulting from LCHF-KD intake diminish IRE1 and PERK activation, thereby maintaining ER homeostasis and reducing the accumulation of misfolded proteins (66). Additionally, the LCHF-KD diet enhances autophagy, which facilitates the clearance of misfolded proteins and damaged organelles from the ER. This effect is driven by AMPK activation and mTOR inhibition, along with the upregulation of autophagy-related proteins such as Atg5/7 and LC3-II (86). Moreover, the LCHF-KD modulates the gut microbiota by reducing the population of LPS-producing bacteria and increasing the population of microbes that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) suppress histone deacetylases (HDACs) and inflammatory gene expression while reducing intestinal permeability, thereby limiting systemic inflammation and ER stress (97). Together, these interconnected mechanisms highlight the therapeutic potential of the LCHF-KD diet in addressing insulin resistance and ER stress-associated metabolic dysfunction.

The potential roles and the mechanisms by which a LCHF mitigates ER stress-related insulin resistance are presented in Table 7. Table 7 illustrates the diet’s impact on metabolic stability, inflammatory response, antioxidant capacity, and other factors, highlighting how these elements contribute to enhanced insulin sensitivity and cellular health.

Discussion

The increasing prevalence of metabolic diseases has encouraged the evaluation of dietary interventions as potential therapeutic strategies. Among these, the LCHF-KD has garnered attention for its role in modulating ER stress and mitigating insulin resistance, suggesting its potential applicability in personalized medicine.

According to the mechanisms mentioned above, the LCHF-KD could mitigate ER stress-related insulin resistance by inhibiting lipotoxicity (92), increasing insulin sensitivity with concordant prevention of insulin resistance (21), having anti-inflammatory Effects (94), the antioxidant effect (96), improving hormonal balance (98), augmenting autophagy (86), and modulating the gut microbiota population (97).

The potential of the LCHF-KD in personalized medicine has gained attention (99). The intervention of the LCHF-KD in personalized medicine depends on its compliance with the metabolic states and genetic backgrounds of each individual (100). Accordingly, healthcare providers can adapt the LCHF-KD to optimize its impact on ER stress and insulin sensitivity by evaluating a subject’s genetic predisposition to insulin resistance and metabolic profile. The role of the LCHF-KD within this framework is particularly convincing due to its direct impact on metabolic processes related to endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin resistance.

Personalized medicine studies the genetic variations influencing an individual’s response to the LCHF-KD (101). Genes involved in various metabolic and inflammatory pathways, such as fatty acid metabolism (FTO, APOE), insulin secretion (TCF7L2, IRS1), and inflammation (TNFα, IL6), play significant roles in determining dietary efficacy and individual adaptations. Consequently, genetic variations affecting fat metabolism require modifications in dietary fat types or amounts to optimize health outcomes and prevent undesirable LCHF-KD-related effects (101, 102).

To maximize the benefits of LCHF-KD interventions, healthcare providers must utilize comprehensive metabolic profiling, including assessments of glucose metabolism, lipid levels, and inflammatory markers, both in the short term (103) and long term (104). This understanding enables the personalization of nutritional recommendations based on genetic predispositions and metabolic states. For example, introducing omega-3 supplements with antioxidant effects can be specifically recommended to those who have observed increases in oxidative stress or inflammation, ensuring the diet’s effectiveness and safety (93). Furthermore, gut microbiome composition is a crucial consideration in contemporary dietary planning. The microbiota’s composition, population, and roles in metabolizing fats and carbohydrates significantly determine the outcomes of an LCHF-KD (105). Therefore, personalizing diet plans based on microbiome analysis could enhance insulin sensitivity and reduce ERstress, providing a targeted approach to managing metabolic diseases.

To further illustrate the cumulative findings across experimental and clinical studies, Table 8 summarizes the available evidence demonstrating the modulatory effects of the LCHF-KD on ER stress and insulin resistance. The table integrates data from in vivo experimental animal and human clinical studies, highlighting how dietary-induced ketosis influences ER-stress signaling pathways and insulin sensitivity through molecular, metabolic, and anti-inflammatory mechanisms.

Table 8. Summary of experimental and clinical evidence on the effect of low-carbohydrate, high-fat ketogenic diet (LCHF-KD) on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and insulin resistance.

Despite the potential for personalized LCHF-KD interventions in managing ER stress-related insulin resistance, it is of great significance. Still, several challenges arise when implementing LCHF-KD in the prevention and treatment of ER stress-related insulin resistance. These limitations and challenges include ensuring patient compliance, understanding long-term impacts, and integrating this approach within broader medical guidelines.

So, the current study recommends that to augment the therapeutic use of the LCHF-KD in personalized medicine for managing ER stress-related insulin resistance, Physicians and healthcare providers should receive dedicated training to customize the diet based on individual genetic and metabolic profiles. Collaborative care teams, including dieticians and physicians, should closely monitor and adjust patient diets and improve compliance. Education and awareness programs for the patient’s needs can enhance motivation and compliance. Furthermore, research should focus on identifying genetic markers and metabolic profiles that predict diet responsiveness, assessing long-term health impacts across diverse populations, and exploring the role of the gut microbiome.

Conclusion

The relationship between ER stress and metabolic disease, particularly insulin resistance, is gaining increasing attention in the scientific community. Emerging research highlights the promising potential of targeting ER stress as a novel and effective strategy for preventing and managing insulin resistance and associated metabolic disorders. ER stress has been implicated in the development of insulin resistance, a pivotal element in numerous metabolic diseases, including T2DM, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases.

The potential of therapeutic agents that alleviate ER stress holds substantial promise. Targeting ER stress represents a cornerstone in the prevention and treatment of metabolic diseases. By integrating advanced therapeutic agents, strategic dietary interventions, and conventional therapies, we can enhance our approach to these health challenges, offering hope for better management and, ultimately, prevention of these conditions.

Dietary interventions also play a critical role in managing ER stress. LCHF-KD has been demonstrated to reduce ER stress markers in experimental models. These dietary components may exert their beneficial effects by modulating inflammation and oxidative stress, which are closely intertwined with ER stress. The LCHF-KD can diminish the ER’s overall burden, thereby improving insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic health.

Combining these novel therapeutic agents and dietary strategies with conventional therapies could revolutionize the management of metabolic diseases. By incorporating strategies aimed at reducing ER stress, it is possible to address one of the root causes of metabolic disorders, potentially improving therapeutic outcomes and reducing the incidence of disease progression.

Understanding the precise dietary factors that affect ER stress and insulin resistance, the mechanisms through which they exert their effects, and how these interact with individual genetic and lifestyle factors are critical areas for the personalized medicine approach.

Author contributions

BE: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FG: Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Investigation, Resources. YA: Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GA: Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Software. FA: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SA: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Visualization. SE: Data curation, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision, Validation. TS: Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Data curation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. AE: Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge BioRender for providing the tools necessary to create Figure 1, which is included in this manuscript and was made in BioRender. Eldakhakhny, B. (2025) https://BioRender.com/r39m848. The publication agreement number is BQ281KIPBG.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. OpenAI GPT-4O was utilized to assist with language refinement, improve clarity, and ensure consistency in formatting across written sections of the manuscript. The authors independently developed the content, including all ideas, data interpretation, and conclusions. Generative AI was not used to generate or analyze data, nor did it replace the authors' intellectual contributions to the manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Rahman, MS, Hossain, KS, Das, S, Kundu, S, Adegoke, EO, Rahman, MA, et al. Role of insulin in health and disease: an update. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:6403. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126403,

2. Pansuria, M, Xi, H, Li, L, Yang, XF, and Wang, H. Insulin resistance, metabolic stress, and atherosclerosis. Front Biosci (Schol Ed). (2012) 4:916. doi: 10.2741/s308,

3. Wang, HH, Lee, DK, Liu, M, Portincasa, P, and Wang, DQ. Novel insights into the pathogenesis and management of the metabolic syndrome. Pediatric Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. (2020) 23:189. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2020.23.3.189,

4. Gómez-Hernández, A, de Las Heras, N, López-Pastor, AR, García-Gómez, G, Infante-Menéndez, J, González-López, P, et al. Severe hepatic insulin resistance induces vascular dysfunction: improvement by liver-specific insulin receptor isoform a gene therapy in a murine diabetic model. Cells. (2021) 10:2035. doi: 10.3390/cells10082035,

5. Boucher, J, Kleinridders, A, and Kahn, CR. Insulin receptor signaling in normal and insulin-resistant states. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2014) 6:a009191. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009191,

6. Petersen, MC, and Shulman, GI. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. (2018) 98:2133–223. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00063.2017,

7. Lee, SH, Park, SY, and Choi, CS. Insulin resistance: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Diabetes Metab J. (2022) 46:15–37. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2021.0280,

8. Uehara, K, Santoleri, D, Whitlock, AEG, and Titchenell, PM. Insulin regulation of hepatic lipid homeostasis. Compr Physiol. (2023) 13:4785–809. doi: 10.1002/j.2040-4603.2023.tb00269.x

9. da Silva, DC, Valentão, P, Andrade, PB, and Pereira, DM. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in cancer and neurodegenerative disorders: tools and strategies to understand its complexity. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 155:104702. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104702,

10. Wang, M, and Kaufman, RJ. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature. (2016) 529:326–35. doi: 10.1038/nature17041,

11. Siwecka, N, Rozpędek, W, Pytel, D, Wawrzynkiewicz, A, Dziki, A, Dziki, Ł, et al. Dual role of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated unfolded protein response signaling pathway in carcinogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:4354. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184354,

12. Esmaeili, Y, Yarjanli, Z, Pakniya, F, Bidram, E, Łos, MJ, Eshraghi, M, et al. Targeting autophagy, oxidative stress, and ER stress for neurodegenerative disease treatment. J Control Release. (2022) 345:147–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.03.001,

13. Mujumdar, N, Banerjee, S, Chen, Z, Sangwan, V, Chugh, R, Dudeja, V, et al. Triptolide activates unfolded protein response leading to chronic ER stress in pancreatic cancer cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. (2014) 306:G1011–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00466.2013,

14. Oakes, SA, and Papa, FR. The role of endoplasmic reticulum stress in human pathology. Annu Rev Pathol. (2015) 10:173–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104649,

15. Flamment, M, Hajduch, E, Ferré, P, and Foufelle, F. New insights into ER stress-induced insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 23:381–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.003,

16. Brown, M, Dainty, S, Strudwick, N, Mihai, AD, Watson, JN, Dendooven, R, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress causes insulin resistance by inhibiting delivery of newly synthesized insulin receptors to the cell surface. Mol Biol Cell. (2020) 31:2597–629. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-01-0013,

17. Jeziorek, M, Szuba, A, Kujawa, K, and Regulska-Ilow, B. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet versus moderate-carbohydrate and fat diet on body composition in patients with lipedema. Diab Metab Syndr Obes Targets Therapy. (2022) 15:2545–61. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S377720,

18. Zhu, H, Bi, D, Zhang, Y, Kong, C, Du, J, Wu, X, et al. Ketogenic diet for human diseases: the underlying mechanisms and potential for clinical implementations. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2022) 7:11. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00831-w,

19. Gough, SM, Casella, A, Ortega, KJ, and Hackam, AS. Neuroprotection by the ketogenic diet: evidence and controversies. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:782657. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.782657,

20. Paoli, A, Bianco, A, Moro, T, Mota, JF, and Coelho-Ravagnani, CF. The effects of ketogenic diet on insulin sensitivity and weight loss, which came first: the chicken or the egg? Nutrients. (2023) 15:3120. doi: 10.3390/nu15143120,

21. Bima, A, Eldakhakhny, B, Alamoudi, AA, Awan, Z, Alnami, A, Abo-Elkhair, SM, et al. Molecular study of the protective effect of a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet against brain insulin resistance in an animal model of metabolic syndrome. Brain Sci. (2023) 13:1383. doi: 10.3390/brainsci13101383,

22. Kolb, H, Kempf, K, Röhling, M, Lenzen-Schulte, M, Schloot, NC, and Martin, S. Ketone bodies: from enemy to friend and guardian angel. BMC Med. (2021) 19:313. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-02185-0,

23. Tricco, AC, Lillie, E, Zarin, W, O'Brien, KK, Colquhoun, H, Levac, D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850,

24. Kahn, SE, Hull, RL, and Utzschneider, KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. (2006) 444:840–6. doi: 10.1038/nature05482,

25. Czech, MP. Insulin action and resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. (2017) 23:804–14. doi: 10.1038/nm.4350,

26. Zhao, X, An, X, Yang, C, Sun, W, Ji, H, and Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1149239. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1149239,

27. Saklayen, MG. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. (2018) 20:12. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0812-z,

28. Lin, HF, Boden-Albala, B, Juo, SH, Park, N, Rundek, T, and Sacco, RL. Heritabilities of the metabolic syndrome and its components in the northern Manhattan family study. Diabetologia. (2005) 48:2006–12. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1892-2,

29. Wan, ZL, Huang, K, Xu, B, Hu, SQ, Wang, S, Chu, YC, et al. Diabetes-associated mutations in human insulin: crystal structure and photo-cross-linking studies of a-chain variant insulin Wakayama. Biochemistry. (2005) 44:5000–16. doi: 10.1021/bi047585k,

30. Abd El-Kader, SM, and Al-Jiffri, OH. Impact of weight reduction on insulin resistance, adhesive molecules and adipokines dysregulation among obese type 2 diabetic patients. Afr Health Sci. (2018) 18:873–83. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i4.5,

31. Ye, J. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in obesity. Front Med. (2013) 7:14–24. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0262-6,

32. Machado, FVC, Pitta, F, Hernandes, NA, and Bertolini, GL. Physiopathological relationship between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and insulin resistance. Endocrine. (2018) 61:17–22. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1554-z,

33. Rafacho, A, Ortsäter, H, Nadal, A, and Quesada, I. Glucocorticoid treatment and endocrine pancreas function: implications for glucose homeostasis, insulin resistance and diabetes. J Endocrinol. (2014) 223:R49–62. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0373,

34. Cristin, L, Montini, A, Martinino, A, Pereira, JS, Giovinazzo, F, and Agnes, S. The role of growth hormone and insulin growth factor 1 in the development of non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis: a systematic review. Cells. (2023) 12:517. doi: 10.3390/cells12040517,

35. Janssen, J. New insights into the role of insulin and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in the metabolic syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:8178. doi: 10.3390/ijms23158178,

36. Krentz, AJ, Viljoen, A, and Sinclair, A. Insulin resistance: a risk marker for disease and disability in the older person. Diab Med. (2013) 30:535–48. doi: 10.1111/dme.12063,

37. Vieira-Lara, MA, Dommerholt, MB, Zhang, W, Blankestijn, M, Wolters, JC, Abegaz, F, et al. Age-related susceptibility to insulin resistance arises from a combination of CPT1B decline and lipid overload. BMC Biol. (2021) 19:154. doi: 10.1186/s12915-021-01082-5,

38. Sun, Y, and Ding, S. ER–mitochondria contacts and insulin resistance modulation through exercise intervention. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:9587. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249587,

39. Huang, J, Meng, P, Wang, C, Zhang, Y, and Zhou, L. The relevance of organelle interactions in cellular senescence. Theranostics. (2022) 12:2445–64. doi: 10.7150/thno.70588,

40. Keenan, SN, Watt, MJ, and Montgomery, MK. Inter-organelle communication in the pathogenesis of mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance. Curr Diab Rep. (2020) 20:20. doi: 10.1007/s11892-020-01300-4,

41. Ge, Q, Xie, X, Xiao, X, and Li, X. Exosome-like vesicles as new mediators and therapeutic targets for treating insulin resistance and β-cell mass failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Res. (2019) 2019:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2019/3256060,

42. Yuan, M, Konstantopoulos, N, Lee, J, Hansen, L, Li, ZW, Karin, M, et al. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylates or targeted disruption of Ikkbeta. Science. (2001) 293:1673–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1061620,

43. Yin, J, Peng, Y, Wu, J, Wang, Y, and Yao, L. Toll-like receptor 2/4 links to free fatty acid-induced inflammation and β-cell dysfunction. J Leukoc Biol. (2014) 95:47–52. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313143,

44. Apostolopoulos, V, de Courten, MP, Stojanovska, L, Blatch, GL, Tangalakis, K, and de Courten, B. The complex immunological and inflammatory network of adipose tissue in obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2016) 60:43–57. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500272,

45. Orliaguet, L, Dalmas, E, Drareni, K, Venteclef, N, and Alzaid, F. Mechanisms of macrophage polarization in insulin signaling and sensitivity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). (2020) 11:62. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00062,

46. O'Neill, HM, Maarbjerg, SJ, Crane, JD, Jeppesen, J, Jørgensen, SB, Schertzer, JD, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) beta1beta2 muscle null mice reveal an essential role for AMPK in maintaining mitochondrial content and glucose uptake during exercise. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:16092–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105062108,

47. Lipke, K, Kubis-Kubiak, A, and Piwowar, A. Molecular mechanism of lipotoxicity as an interesting aspect in the development of pathological states-current view of knowledge. Cells. (2022) 11:844. doi: 10.3390/cells11050844,

48. Chaurasia, B, and Summers, SA. Ceramides - lipotoxic inducers of metabolic disorders. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 26:538–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.07.006,

49. Iwakami, S, Misu, H, Takeda, T, Sugimori, M, Matsugo, S, Kaneko, S, et al. Concentration-dependent dual effects of hydrogen peroxide on insulin signal transduction in H4IIEC hepatocytes. PLoS One. (2011) 6:e27401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027401,

50. Son, Y, Cheong, Y-K, Kim, N-H, Chung, H-T, Kang, DG, and Pae, H-O. Mitogen-activated protein kinases and reactive oxygen species: how can ROS activate MAPK pathways? J Signal Transd. (2011) 2011:792639. doi: 10.1155/2011/792639,

51. Yuzefovych, LV, LeDoux, SP, Wilson, GL, and Rachek, LI. Mitochondrial DNA damage via augmented oxidative stress regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy: crosstalk, links and signaling. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e83349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083349,

52. Portovedo, M, Ignacio-Souza, LM, Bombassaro, B, Coope, A, Reginato, A, Razolli, DS, et al. Saturated fatty acids modulate autophagy's proteins in the hypothalamus. PLoS One. (2015) 10:e0119850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119850,

53. Gong, Q, Hu, Z, Zhang, F, Cui, A, Chen, X, Jiang, H, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 improves hepatic insulin sensitivity by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 in mice. Hepatology. (2016) 64:425–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.28523,

54. Adams, CJ, Kopp, MC, Larburu, N, Nowak, PR, and Ali, MMU. Structure and molecular mechanism of ER stress signaling by the unfolded protein response signal activator IRE1. Front Mol Biosci. (2019) 6:11. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2019.00011,

55. Alberts, B, Johnson, A, Lewis, J, Raff, M, Roberts, K, and Walter, P. Molecular biology of the cell. Bray D. Cell movements: from molecules to motility. 2nd ed: New York, NY: Garland Science. (2002).

56. Lemmer, IL, Willemsen, N, Hilal, N, and Bartelt, A. A guide to understanding endoplasmic reticulum stress in metabolic disorders. Mol Metab. (2021) 47:101169. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101169,

57. Schönthal, AH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: its role in disease and novel prospects for therapy. Scientifica. (2012) 2012:1–26. doi: 10.6064/2012/857516,

58. Ron, D, and Walter, P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 8:519–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199,

59. Chatterjee, BK, Puri, S, Sharma, A, Pastor, A, and Chaudhuri, TK. Molecular chaperones: structure-function relationship and their role in protein folding In: A Asea and P Kaur, editors. Heat shock proteins. Cham: Springer (2018)

60. Malhotra, JD, and Kaufman, RJ. The endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell Dev Biol. (2007) 18:716–31. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.09.003,

61. Ozcan, U, Cao, Q, Yilmaz, E, Lee, AH, Iwakoshi, NN, Ozdelen, E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. (2004) 306:457–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160,

62. Hotamisligil, GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. (2010) 140:900–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034,

63. Fernandes-da-Silva, A, Miranda, CS, Santana-Oliveira, DA, Oliveira-Cordeiro, B, Rangel-Azevedo, C, Silva-Veiga, FM, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress as the basis of obesity and metabolic diseases: focus on adipose tissue, liver, and pancreas. Eur J Nutr. (2021) 60:2949–60. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02542-y,

64. Onyango, AN. Cellular stresses and stress responses in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. (2018) 2018:4321714. doi: 10.1155/2018/4321714,

65. Sharma, RB, and Alonso, LC. Lipotoxicity in the pancreatic beta cell: not just survival and function, but proliferation as well? Curr Diab Rep. (2014) 14:492. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0492-2,

66. Kumar, V, and Maity, S. ER stress-sensor proteins and ER-mitochondrial crosstalk-signaling beyond (ER) stress response. Biomolecules. (2021) 11:173. doi: 10.3390/biom11020173,

67. McLaughlin, T, Medina, A, Perkins, J, Yera, M, Wang, JJ, and Zhang, SX. Cellular stress signaling and the unfolded protein response in retinal degeneration: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Mol Neurodegener. (2022) 17:25. doi: 10.1186/s13024-022-00528-w,

68. Oikonomou, C, and Hendershot, LM. Disposing of misfolded ER proteins: a troubled substrate's way out of the ER. Mol Cell Endocrinol. (2020) 500:110630. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110630,

69. Yin, JJ, Li, YB, Wang, Y, Liu, GD, Wang, J, Zhu, XO, et al. The role of autophagy in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced pancreatic β cell death. Autophagy. (2012) 8:158. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.2.18807

70. Wilkinson, S. ER-phagy: shaping up and destressing the endoplasmic reticulum. FEBS J. (2019) 286:2645–63. doi: 10.1111/febs.14932,

71. Ariyasu, D, Yoshida, H, and Hasegawa, Y. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and endocrine disorders. Int J Mol Sci. (2017) 18:382. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020382,

72. Dasgupta, A, Bandyopadhyay, GK, Ray, I, Bandyopadhyay, K, Chowdhury, N, De, RK, et al. Catestatin improves insulin sensitivity by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress: in vivo and in silico validation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. (2020) 18:464. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.02.005,

73. Nuwaylati, D, Eldakhakhny, B, Bima, A, Sakr, H, and Elsamanoudy, A. Low-carbohydrate high-fat diet: a SWOC analysis. Meta. (2022) 12:1126. doi: 10.3390/metabo12111126,

74. Burke, LM. Ketogenic low-CHO, high-fat diet: the future of elite endurance sport? J Physiol. (2021) 599:819–43. doi: 10.1113/JP278928,

75. Masood, W, Annamaraju, P, Khan Suheb, MZ, and Uppaluri, KR. (2024). Ketogenic diet. [Updated 16 June 2023]. StatPearls [Internet]; Treasure Island: StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL.

76. Shaw, DM, Merien, F, Braakhuis, A, Maunder, ED, and Dulson, DK. Effect of a ketogenic diet on submaximal exercise capacity and efficiency in runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2019) 51:2135–46. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002008,

77. Napoleão, A, Fernandes, L, Miranda, C, and Marum, AP. Effects of calorie restriction on health span and insulin resistance: classic calorie restriction diet vs. ketosis-inducing diet. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1302. doi: 10.3390/nu13041302,

78. Drabińska, N, Juśkiewicz, J, and Wiczkowski, W. The effect of the restrictive ketogenic diet on the body composition, haematological and biochemical parameters, oxidative stress and advanced glycation end-products in young Wistar rats with diet-induced obesity. Nutrients. (2022) 14:4805. doi: 10.3390/nu14224805,

79. Jang, J, Kim, SR, Lee, JE, Lee, S, Son, HJ, Choe, W, et al. Molecular mechanisms of neuroprotection by ketone bodies and ketogenic diet in cerebral ischemia and neurodegenerative diseases. Int J Mol Sci. (2023) 25:124. doi: 10.3390/ijms25010124,

80. Youm, YH, Nguyen, KY, Grant, RW, Goldberg, EL, Bodogai, M, Kim, D, et al. The ketone metabolite β-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med. (2015) 21:263–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.3804,

81. Barrea, L, Caprio, M, Tuccinardi, D, Moriconi, E, Di Renzo, L, Muscogiuri, G, et al. Could ketogenic diet "starve" cancer? Emerging evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2022) 62:1800–21. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1847030,

82. Alnami, A, Bima, A, Alamoudi, A, Eldakhakhny, B, Sakr, H, and Elsamanoudy, A. Modulation of dyslipidemia markers Apo B/Apo a and triglycerides/HDL-cholesterol ratios by low-carbohydrate high-fat diet in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. (2022) 14:1903. doi: 10.3390/nu14091903,

83. He, Y, Cheng, X, Zhou, T, Li, D, Peng, J, Xu, Y, et al. β-Hydroxybutyrate as an epigenetic modifier: underlying mechanisms and implications. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e21098. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21098,

84. Santangelo, A, Corsello, A, Spolidoro, GCI, Trovato, CM, Agostoni, C, Orsini, A, et al. The influence of ketogenic diet on gut microbiota: potential benefits, risks and indications. Nutrients. (2023) 15:3680. doi: 10.3390/nu15173680,

85. Almoghrabi, YM, Eldakhakhny, BM, Bima, AI, Sakr, H, Ajabnoor, GMA, Gad, HM, et al. The interplay between nutrigenomics and low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets in personalized healthcare. Front Nutr. (2025) 12:1595316. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1595316,

86. Eldakhakhny, B, Bima, A, Alamoudi, AA, Alnami, A, Abo-Elkhair, SM, Sakr, H, et al. The role of low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet in modulating autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress in aortic endothelial dysfunction of metabolic syndrome animal model. Front Nutr. (2024) 11:1467719. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2024.1467719,

87. Li, C, Ma, Y, Chai, X, Feng, X, Feng, W, Zhao, Y, et al. Ketogenic diet attenuates cognitive dysfunctions induced by hypoglycemia via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent pathways. Food Funct. (2024) 15:1294–309. doi: 10.1039/D3FO04007K,

88. Ma, Q, Jiang, L, You, Y, Ni, H, Ma, L, Lin, X, et al. Ketogenic diet ameliorates high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in mouse skeletal muscle by alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2024) 702:149559. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2024.149559,

89. Guo, M, Wang, X, Zhao, Y, Yang, Q, Ding, H, Dong, Q, et al. Ketogenic diet improves brain ischemic tolerance and inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome activation by preventing Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front Mol Neurosci. (2018) 11:86. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00086,

90. Snel, M, Jonker, JT, Schoones, J, Lamb, H, de Roos, A, Pijl, H, et al. Ectopic fat and insulin resistance: pathophysiology and effect of diet and lifestyle interventions. Int J Endocrinol. (2012) 2012:983814. doi: 10.1155/2012/983814,

91. Yuan, X, Wang, J, Yang, S, Gao, M, Cao, L, Li, X, et al. Effect of the ketogenic diet on glycemic control, insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism in patients with T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Diabetes. (2020) 10:38. doi: 10.1038/s41387-020-00142-z,

92. Sakr, HF, Sirasanagandla, SR, Das, S, Bima, AI, and Elsamanoudy, AZ. Low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet for improvement of glycemic control: mechanism of action of ketosis and beneficial effects. Curr Diabetes Rev. (2023) 19:e110522204580. doi: 10.2174/1573399818666220511121629,

93. Yang, J, Fernández-Galilea, M, Martínez-Fernández, L, González-Muniesa, P, Pérez-Chávez, A, Martínez, JA, et al. Oxidative stress and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: effects of Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation. Nutrients. (2019) 11:872. doi: 10.3390/nu11040872,

94. Santamarina, AB, Mennitti, LV, de Souza, EA, Mesquita, LMS, Noronha, IH, Vasconcelos, JRC, et al. A low-carbohydrate diet with different fatty acids' sources in the treatment of obesity: impact on insulin resistance and adipogenesis. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland). (2023) 42:2381–94. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2023.09.024,

95. Zhang, W, Chen, S, Huang, X, Tong, H, Niu, H, and Lu, L. Neuroprotective effect of a medium-chain triglyceride ketogenic diet on MPTP-induced Parkinson's disease mice: a combination of transcriptomics and metabolomics in the substantia nigra and fecal microbiome. Cell Death Discov. (2023) 9:251. doi: 10.1038/s41420-023-01549-0,

96. Wan, SR, Teng, FY, Fan, W, Xu, BT, Li, XY, Tan, XZ, et al. BDH1-mediated βOHB metabolism ameliorates diabetic kidney disease by activation of NRF2-mediated antioxidative pathway. Aging. (2023) 15:13384–410. doi: 10.18632/aging.205248,

97. Lathigara, D, Kaushal, D, and Wilson, RB. Molecular mechanisms of Western diet-induced obesity and obesity-related carcinogenesis-a narrative review. Meta. (2023) 13:675. doi: 10.3390/metabo13050675,

98. Kumar, S, Behl, T, Sachdeva, M, Sehgal, A, Kumari, S, Kumar, A, et al. Implicating the effect of ketogenic diet as a preventive measure to obesity and diabetes mellitus. Life Sci. (2021) 264:118661. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118661,

99. Webster, CC, Murphy, TE, Larmuth, KM, Noakes, TD, and Smith, JA. Diet, diabetes status, and personal experiences of individuals with type 2 diabetes who self-selected and followed a low carbohydrate high fat diet. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. (2019) 12:2567–82. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S227090

100. Iatan, I, Huang, K, Vikulova, D, Ranjan, S, and Brunham, LR. Association of a low-carbohydrate high-fat diet with plasma lipid levels and cardiovascular risk. JACC Adv. (2024) 3:100924. doi: 10.1016/j.jacadv.2024.100924,

101. Aronica, L, Volek, J, Poff, A, and D'agostino, DP. Genetic variants for personalised management of very low carbohydrate ketogenic diets. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. (2020) 3:363–73. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2020-000167,

102. McCullough, D, Harrison, T, Boddy, LM, Enright, KJ, Amirabdollahian, F, Schmidt, MA, et al. The effect of dietary carbohydrate and fat manipulation on the metabolome and markers of glucose and insulin metabolism: a randomised parallel trial. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3691. doi: 10.3390/nu14183691,

103. Cipryan, L, Maffetone, PB, Plews, DJ, and Laursen, PB. Effects of a four-week very low-carbohydrate high-fat diet on biomarkers of inflammation: non-randomised parallel-group study. Nutr Health. (2020) 26:35–42. doi: 10.1177/0260106020903206,

104. Perissiou, M, Borkoles, E, Kobayashi, K, and Polman, R. The effect of an 8 week prescribed exercise and low-carbohydrate diet on cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese individuals: a randomised controlled trial. Nutrients. (2020) 12:482. doi: 10.3390/nu12020482,

105. Burén, J, Ericsson, M, Damasceno, NRT, and Sjödin, A. A ketogenic low-carbohydrate high-fat diet increases LDL cholesterol in healthy, young, normal-weight women: a randomized controlled feeding trial. Nutrients. (2021) 13:814. doi: 10.3390/nu13030814,

106. Herman, R, Kravos, NA, Jensterle, M, Janež, A, and Dolžan, V. Metformin and insulin resistance: a review of the underlying mechanisms behind changes in GLUT4-mediated glucose transport. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:1264. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031264,

107. Chakera, AJ, Steele, AM, Gloyn, AL, Shepherd, MH, Shields, B, Ellard, S, et al. Recognition and management of individuals with hyperglycemia because of a heterozygous glucokinase mutation. Diabetes Care. (2015) 38:1383–92. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2769,

108. Brown, AE, and Walker, M. Genetics of insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. (2016) 18:75. doi: 10.1007/s11886-016-0755-4,

109. Al-Suhaimi, EA, and Shehzad, A. Leptin, resistin and visfatin: the missing link between endocrine metabolic disorders and immunity. Eur J Med Res. (2013) 18:12. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-18-12,

110. Kumar, S, Gupta, V, Srivastava, N, Gupta, V, Mishra, S, Mishra, S, et al. Resistin 420C/G gene polymorphism on circulating resistin, metabolic risk factors and insulin resistance in adult women. Immunol Lett. (2014) 162:287–91. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.07.009,

111. Al-Beltagi, M, Bediwy, AS, and Saeed, NK. Insulin-resistance in paediatric age: its magnitude and implications. World J Diabetes. (2022) 13:282–307. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i4.282,

112. Mackenzie, RW, and Elliott, BT. Akt/PKB activation and insulin signaling: a novel insulin signaling pathway in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diab Metab Syndr Obes Targets Therapy. (2014) 7:55–64. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S48260,

113. Kwon, H, Jang, D, Choi, M, Lee, J, Jeong, K, and Pak, Y. Alternative translation initiation of Caveolin-2 desensitizes insulin signaling through dephosphorylation of insulin receptor by PTP1B and causes insulin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol basis Dis. (2018) 1864:2169–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.03.022,

114. Darwish, HS, Alrahbi, B, Almamri, H, Noone, M, Osman, H, and Abdelhalim, A. Genomic study of TCF7L2 gene mutation on insulin secretion for type 2 DM patients: a review. Ann Res Rev Biol. (2022) 37:86–93. doi: 10.9734/arrb/2022/v37i1230560,

115. Ricci, C, Pastukh, V, Leonard, J, Turrens, J, Wilson, G, Schaffer, D, et al. Mitochondrial DNA damage triggers mitochondrial-superoxide generation and apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2008) 294:C413–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00362.2007,

116. Suzuki, M, Aoshiba, K, and Nagai, A. Oxidative stress increases Fas ligand expression in endothelial cells. J Inflamm (Lond). (2006) 3:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-3-11,

117. Thoudam, T, Ha, CM, Leem, J, Chanda, D, Park, JS, Kim, HJ, et al. PDK4 augments ER-mitochondria contact to dampen skeletal muscle insulin signaling during obesity. Diabetes. (2019) 68:571–86. doi: 10.2337/db18-0363,

118. Ajoolabady, A, Liu, S, Klionsky, DJ, Lip, GYH, Tuomilehto, J, Kavalakatt, S, et al. ER stress in obesity pathogenesis and management. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 43:97–109. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2021.11.011,

119. Wu, J, Wu, D, Zhang, L, Lin, C, Liao, J, Xie, R, et al. NK cells induce hepatic ER stress to promote insulin resistance in obesity through osteopontin production. J Leukoc Biol. (2020) 107:589–96. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MA1119-173R,