Abstract

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has a long history of use in traditional medicine and the modern world to alleviate health conditions, particularly those related to indigestion and nausea. Gingerols are phenolic bioactive compounds found in ginger. It has been suggested that health benefits associated with gingerols may be due to modification of the gut microbiome, especially in disease models. However, the impact of gingerol on a healthy human gut microbiome, and whether age affects gingerol activity, is not well understood. To address this, the impact of 6-gingerol, the most abundant polyphenol found in ginger, on the gut microbiomes of four age groups (infants, children, adults (22–40), and adults (60+)) was determined using SIFR® technology. Following a 24-h incubation with 6-gingerol, microbial community genomic analysis was performed together with metabolic analysis to determine the impact of 6-gingerol on the gut microbiota ex vivo. Using this method, 6-gingerol was determined to have no significant impact on the gut microbiota in terms of community density, community diversity, or short-chain fatty acid production. This study found that, in healthy gut microbiota, 6-gingerol did not have a strong effect within a 24-h period of treatment.

Introduction

The gut microbiota is a complex community of organisms that changes and develops throughout life in response to various stimuli, including hormonal shifts, environmental changes, and activity level (1). However, one of the main mechanisms for modification of the gut microbiota is through dietary alterations (2, 3). Intentional and unintentional alteration of the gut microbiota through dietary intake has been a major focus of research on gut health. Many major dietary modifications cause significant changes to the gut microbiota in terms of its community structure and functional output within as little as 24–48 h (4).

The impact of gut microbial community structure and its functional outputs, on not only gut health but overall health, has resulted in increased interest by both industry producers and consumers to identify dietary changes and to develop supplements that may improve health outcomes. These dietary changes and supplements often include probiotics (live bacterial strains) and prebiotics (dietary fibers) but may also include other small molecules found in fruits, vegetables, and herbs, such as polyphenols (5). Following consumption, the majority of polyphenols (>90%) are unchanged through the digestive system until they reach the colon (6, 7). Upon reaching the colon, the gut microbiota may degrade the polyphenols into intermediary and end products, which have increased bioavailability as compared to the original polyphenols, and their subsequent absorption may be the cause of some health benefits associated with polyphenol consumption (5, 8).

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has a long history of use as a traditional medicine, particularly in the form of herbal tea, which is a major contributor of dietary polyphenols (9). For gastrointestinal health in particular, ginger is often used to alleviate nausea, vomiting, and indigestion (10). Powdered ginger root has also demonstrated effectiveness against gastrointestinal disorders and disease in colitis mouse models by reducing inflammation and modifying the gut microbiome structure (11). There are many different bioactive compounds in ginger, including its polysaccharides, which have been shown to alleviate intestinal inflammation and help to remediate changes to the gut microbiome that occur in colitis mouse models (12). Ginger also contains multiple polyphenols, including: 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, 12-gingerol, and 6-shoagal. Of these, the most abundant is 6-gingerol (13). Previous work using in vitro fermentation of mouse feces found that incubation with an extracted polyphenol mixture from ginger modified the gut microbiota by increasing the abundance of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and increased the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (13).

6-gingerol has shown promise in benefiting health in a number of disease states, including anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity (14, 15). 6-gingerol has also demonstrated efficacy in anti-obesity effects, including modification of the gut microbiota in mice fed a high-fat diet (15). Like many polyphenols, 6-gingerol largely reaches the colon intact and is then transformed by members of the gut microbiota into intermediary and end-products. 6-gingerol is degraded through glycosylation by glycosyltransferases (GT), and specifically by uridine diphosphate-glucose (UDP)-GTs (16). However, little has been done on the impact of 6-gingerol on a healthy gut microbiota, or across age groups.

To address this research gap, we aimed to outline the impact of 6-gingerol on the healthy human gut microbiota across age groups, including breast-fed (BF) infants, children, adults 22–40, and adults over 60 using ex vivo Systematic Intestinal Fermentation Research (SIFR®) technology. DNA sequencing and metabolomic analysis were performed after incubation for 24-h to determine whether 6-gingerol meaningfully modifies the healthy gut microbiota in terms of either structure of function.

Methods

Ex vivo fermentation using SIFR®

Ex vivo fermentations were performed by Cryptobiotix (Belgium) using SIFR® technology, similarly to those described previously (17). Fecal samples were collected from 9 healthy donors from each age category: Breastfed infants (0–3 months)(BF infants), children (5–8 years old), adults 22–40 years old, and adults 60+ years old. Fecal collection was performed according to IRB approval from the Ethics committee of the University Hospital Ghent, Belgium (BC-09977). Exclusion criteria included no probiotic, prebiotic, or antibiotic use for 3 months prior to donation. Fermentations were performed for 24 h. Two fermentations were performed for each donor, one with 1.2 mg/L 6-gingerol (Bio-connect, Huissen, The Netherlands) treatment, and one that was the no-substrate control (NSC). Medium M0019 (Cryptobiotix, Ghent, Belgium) was used for fermentation for BF infant donors, M0017 (Cryptobiotix, Ghent, Belgium) was used for fermentations for children and adults.

DNA extraction, library preparation, and 16s rRNA gene sequencing

DNA extraction was performed as described previously using a SPINeasyDNA kit for Soil (BP Biomedicals, Eschwege, Germany) according to the standard instructions (18).

Genomic sequencing was performed targeting the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene using 2×300 bp chemistry on an Illumina Miseq (Illumina, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines (19). Briefly, primers (Integrated DNA technologies, Coralville, IA) amplified the 16S variable region using 2X KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and AMP XP beads (VWR International, Radnor, PA) were used for PCR clean-up. Indexed libraries were generated using NExteraXT Indexes (Ilumina, San Diego, CA). Libraries were combined with 30% PhiX (Illumina) as an internal control and 10pM loaded on a V3 reagent cartridge (Illumina).

Total bacterial cell counts were determined using a BD FACS Verse flow cytometer (BD, Erembodegem, Belgium) as described previously and analyzed using FlowJo V. 10.8.1 (20).

GC-FID analysis of short-chain fatty acids and other metabolic products

SCFA (acetate, propionate, butyrate and valerate) and branched-chain fatty acids (bCFA; sum of isobutyrate, isocaproate and isovalerate) were determined via gas chromatography with flame ionization detection, upon diethyl ether extraction, as previously described (21). Briefly, 0.5 mL samples were diluted in distilled water (1:3), acidified with 0.5 mL of 48% sulfuric acid, after which an excess of sodium chloride was added along with 0.2 mL of internal standard (2-methylhexanoic acid) and 2 mL of diethyl ether. Upon homogenization and separation of the water and diethyl ether layer, diethyl ether extracts were collected and analysed using a Trace 1,300 chromatograph (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Merelbeke, Belgium) equipped with a Stabilwax-DA capillary GC column, a flame ionization detector, and a split injector using nitrogen gas as the carrier and makeup gas. The injection volume was 1 μL and the temperature profile was set from 110 °C to 240 °C. The carrier gas was nitrogen, and the temperatures of the injector and detector were 240 and 250 °C, respectively. pH was measured using an electrode (Hannah Instruments Edge HI2002, Temse, Belgium). Lactate was quantified using an enzymatic method (Enzytec™, R-Biopharm, Darmstadt, Germany).

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Raw reads were processed using DADA2 (22) within the QIIME2 (v 2–23.7) environment (23) with the parameters p-trim-left and p-trim-right = 15; p-trunc-len-f and p-trunc-len-r = 250. ASVs were taxonomically classified against the Silva 138–99 database (24) using a naïve Bayes classifier implemented in scikit-bio (25). A rooted phylogenetic tree was generated using MAFFR and weighted UniFrac distanced calculated. Principle coordinates analysis was implemented using R library ‘ape’ (26) and visualized using tidyverse (27).

Community functional prediction was performed using PICRUSt2 (v.2.5.1) (28). Tests for significantly differentially abundant taxa (phylum and genus level), and functions were performed using MaAsLin3 (29) treatment was used as the fixed effect with door as the random effect. PERMANOVA testing for significant clustering by treatment across all ages or within age groups was performed using pairwise.adonis.2 (30).

Results

SIFR® technology was used to perform 24-h incubations with 1.2 mg/L 6-gingerol to determine the impact of the polyphenol on the gut microbiome of 4 separate age groups in terms of community structure, relative abundance, and fermentation products. This dose was selected based on the amount of 6-gingerol found in ginger extract (13) and previous work performed that determined 4 g/D of ginger consumption was able to reduce chronic disease (31).

Cell counts were performed using flow cytometry to determine community density and are illustrated in Figure 1A. Consistent with previous literature, there was an age-associated increase in cell count after infancy, as demonstrated by an increase in the density of the gut microbiota in children. The cell density remained the same for adults 22–40 and started to decline for adults 60+. Treatment with 6-gingerol did not significantly impact the density of any of the age groups. Next, two alpha diversity measures were employed to determine whether the intra-sample structure of the gut microbiomes changed with 6-gingerol treatment. The alpha diversity metrics used for these purposes were observed features, and Shannon’s Index, shown in Figures 1B,C. Similarly to what was found with community density, alpha diversity was also lowest for the BF infants, with a significant increase (adjusted p < 0.05) in alpha diversity for the children group. The increase in alpha diversity continued throughout both adult groups, but increases were not significant. Treatment with 6-gingerol only significantly impacted the children age group (adj. p < 0.05) for observed features (Figure 1B). Shannon’s index alpha diversity measures were not impacted significantly by 6-gingerol treatment.

Figure 1

Gut microbiome community structure based on alpha and beta diversity metrics. 6-gingerol groups are shown in dark gold, and non-substrate controls are shown in grey. (A) Cell count determined by flow cytometry, (B) observed features, (C) Shannon’s Index, (D) weighted UniFrac analysis with all age groups together (top) and separated (bottom). Significance was determined for Panels A–C using paired t-tests with Benjamini Hochberg correction. Significance was determined for Panel D using PERMANOVA analysis.

Beta diversity analysis using weighted UniFrac distances and principle coordinates analysis (PCoA) was performed to determine inter-sample diversity. Weighted UniFrac analysis was performed to consider the identity and abundance of the taxa that are shared between samples and is shown in Figure 1D. Similarly to alpha diversity, BF infant samples clustered together, and the other three age groups clustered together, and there was no significant clustering associated with 6-gingerol treatment (PERMANOVA q >> 0.05, see Supplementary Table 1).

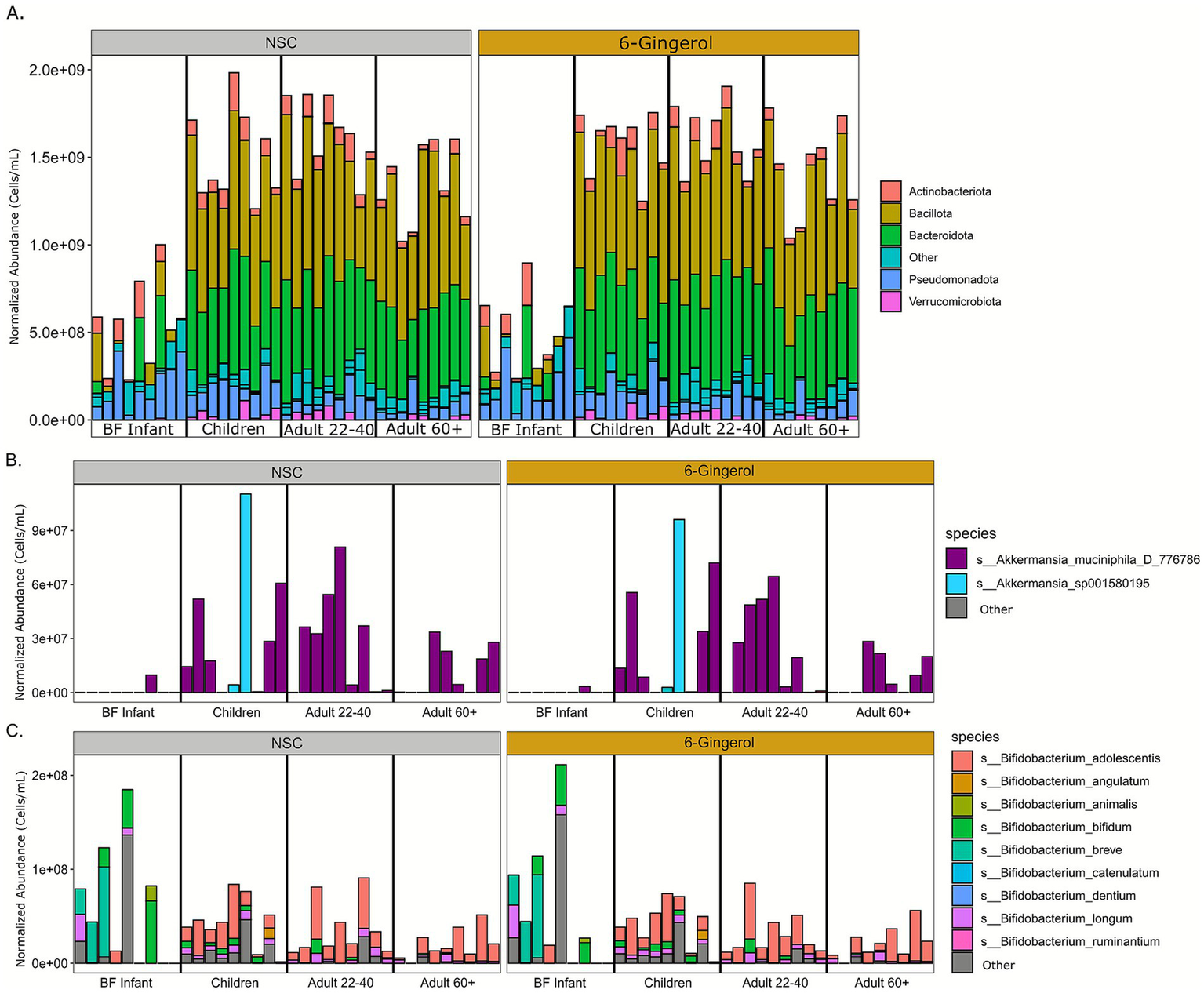

Next, bacterial abundance was normalized to cell count data to determine whether there were any changes in taxa abundance with 6-gingerol treatment. At the phylum level, as shown in Figure 2A, there were no significant changes in any age group due to 6-gingerol treatment. Rather, there was a continuation of the expected pattern that the gut microbiota reaches structural stability early in childhood (1). This expected pattern includes the development of communities that are dominated by Bacteriodota and Firmicutes (Bacilota) phyla. Statistical analysis determined no significant changes with respect to 6-gingerol treatment at any age, or any taxonomic level. Previous studies have shown that polyphenols extracted from ginger have increased species within Akkermansia, therefore the Akkermansia abundance data was extracted and shown in Figure 2B. In this figure, the BF infants had the lowest density of Akkermansia present compared with other age groups, but the species that was present was Akkermansia muciniphila. Similarly to overall bacterial abundance, A. muciniphila increased in abundance for children, where there was also another species present in a few of the donors, Akkermansia sp001580195. This species was not present in the adult 22–40 group, and, after childhood, Akkermansia decreases in abundance over the course of the age groups. Bifidobacterium relative abundance was also extracted for closer exploration due to its known divergence in abundance between age groups (Figure 2C). Here, the data continues to demonstrate expected age progression, as it is shown that the BF infants have the highest abundance of Bifidobacterium, as well as the most diversity of species present, whereas throughout the aging process there is a decrease in overall abundance of Bifidobacterium, as well as a decrease in diversity. Treatment with 6-gingerol did not change this outcome.

Figure 2

Taxon abundance analysis normalized to cell count data. (A) Phylum relative abundance, (B)Akkermansia abundance, (C)Bifidobacterium abundance.

As certain enzymes from the GT1 family (primarily UDP-glycosyltransferases) have been shown capable of glycosylating 6-gingerol, we searched the predicted functional metagenome for genes from this family. There was one possible candidate associated with a member of the Paraclostridium genus but this was present in only a single untreated sample at very low read counts. Effectively, the gut microbiomes profiled here do not appear to contain the bacterial functional potential for the degradation of 6-gingerol.

Additionally, functional analysis of the gut microbiome was performed by evaluating measures of fermentation, including pH values and gas production (Figure 3). Following 24 h of incubation, the pH of the BF infant group was highest regardless of treatment. As age progressed, there was a decrease in pH for the children and adults 22–40, and then a slight increase for the adults 60+. While there were some variations in pH values with 6-gingerol treatment, none were statistically significant. In terms of gas production, BF infant incubations produced the least gas, and the value increased with the age of the study groups. Once again, while there were slight variations with 6-gingerol treatment, none reached the level of statistical significance. Next, SCFA analysis was performed to determine production of total branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA), SCFAs, and then SCFAs of interest: acetate, butyrate, propionate, and valerate. Lactate was also measured using GC-FID. As is typical, the BF infants had the lowest production of all of these measures except for lactate. Similarly to the results found above, for the rest of the fatty acids, there was an increase in age from BF infants to children, and then the values remain steady for adults 22–40 and adults 60+. As is the case of gas production and pH levels, there was some fluctuation in fatty acid levels with 6-gingerol treatment, however none of those changes were statistically significant.

Figure 3

Functional analysis of the microbiome. Statistics were performed using paired t-tests and Benjamini Hochberg false discovery rate correction.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of the polyphenol 6-gingerol, one of the main bioactive compounds in ginger on the healthy human gut microbiome across age groups ex vivo. Following 24-h incubation, genomic and metabolic analyses were performed to find changes due to 6-gingerol treatment. Overall, this study confirmed previous work that the gut microbiome reaches maturity at early childhood, as expressed by the significant changes found between the BF infants and all other age groups, in all categories of analysis demonstrated here (1, 32).

The mechanism of degradation of 6-gingerol by the gut microbiota has not been thoroughly elucidated. To our knowledge, there is only one known mechanism of modification by a member of the gut microbiota, and that is by B. subtilis, through glycosyltransferases, particularly BsUGT489, which transforms 6-gingerol into 5 byproducts of the glycosylation reaction (16). Through a thorough analysis of the current data, however, we found very limited results for either the presence of B. subtilis or the presence of GT family type 1. In fact, we found only one potential candidate from a single donor. This indicates that either most of the individual donors in this experiment are lacking the ability to modify 6-gingerol into its byproducts or that there is a lack of literature available on how the gut microbiota degrades 6-gingerol.

6-gingerol only minimally impacted the healthy gut microbiome ex vivo at any age group tested here. In fact, the only statistically significant change due to 6-gingerol treatment was a decrease in observed features of the children age group. This was somewhat surprising, given findings by others that 6-gingerol impacts the gut microbiome by increasing microbial diversity, increasing certain beneficial taxa including A. muciniphila, and increasing the production of SCFAs (14, 15, 33, 34). However, most of the studies available use mouse models of disease, such as obesity models with high-fat diets or colitis models. Taken together, these results may indicate that 6-gingerol has an ability to positively influence gut health of those with conditions that include inflammation. The study by Wang et al. (34) demonstrated that 6-gingerol decreased inflammatory factors, including TNF-α, LPS, and IL-6. Since this study design does not include mammalian tissue, our results are limited in only determining impacts on the gut microbiota alone. Therefore, our results indicate that 6-gingerol has limited impact on the gut microbiota of healthy individuals at the dose of 1.2 mg/L. This is in line with previous results from our group exploring the impact of different polyphenols extracts of spices that are often used for their health benefits with respect to gut health, such as cinnamon, turmeric, and cumin (35). Other work performed by our group to look at the impact of extracts known to have harmful effects on the gut microbiota, such as Senna seed has shown drastic changes to the gut microbiota over a similar time frame (17). Taken together, this may be an indication that polyphenols that benefit the health of the gut microbiota could do so by providing a stabilizing effect on a healthy gut microbiota as opposed to an induction of major changes to the gut microbiota structure or function, however this assertion requires more detailed study.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with accession number: PRJNA1372016, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1372016.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee University of Ghent; project BC-09977. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

KM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AN: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing. LL: Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the USDA In-House Project 8072-41000-108-00-D, “In Vitro Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystems: Effect of Diet.” This research used resources provided by the SCINet project of the USDA Agricultural Research Service, ARS project number 0500-00093-001-11-D. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

Mention of trade names or commercial products in this article is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2025.1711783/full#supplementary-material

References

1.

Martino C Dilmore AH Burcham ZM Metcalf JL Jeste D Knight R . Microbiota succession throughout life from the cradle to the grave. Nat Rev Microbiol. (2022) 20:707–20. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00768-z,

2.

Flint HJ . The impact of nutrition on the human microbiome. Nutr Rev. (2012) 70:S10–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00499.x,

3.

Ramos S Martín MÁ . Impact of diet on gut microbiota. Curr Opin Food Sci. (2021) 37:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2020.09.006

4.

David LA Maurice CF Carmody RN Gootenberg DB Button JE Wolfe BE et al . Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. (2014) 505:559–63. doi: 10.1038/nature12820,

5.

Edwards C Havlik J Cong W Mullen W Preston T Morrison D et al . Polyphenols and health: interactions between fibre, plant polyphenols and the gut microbiota. Nutr Bull. (2017) 42:356–60. doi: 10.1111/nbu.12296,

6.

Williamson G Manach C . Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. II. Review of 93 intervention studies. Am J Clin Nutr. (2005) 81:243S–55S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.243S,

7.

Ozdal T Sela DA Xiao J Boyacioglu D Chen F Capanoglu E . The reciprocal interactions between polyphenols and gut microbiota and effects on bioaccessibility. Nutrients. (2016) 8:78. doi: 10.3390/nu8020078,

8.

Wang X Qi Y Zheng H . Dietary polyphenol, gut microbiota, and health benefits. Antioxidants. (2022) 11:1212. doi: 10.3390/antiox11061212,

9.

Zamora-Ros R Knaze V Rothwell JA Hémon B Moskal A Overvad K et al . Dietary polyphenol intake in Europe: the European prospective investigation into Cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. Eur J Nutr. (2016) 55:1359–75. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0950-x,

10.

Nikkhah Bodagh M Maleki I Hekmatdoost A . Ginger in gastrointestinal disorders: a systematic review of clinical trials. Food Sci Nutr. (2019) 7:96–108. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.807,

11.

Guo S Geng W Chen S Wang L Rong X Wang S et al . Ginger alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis severity by improving the diversity and function of gut microbiota. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:632569. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.632569

12.

Hao W Chen Z Yuan Q Ma M Gao C Zhou Y et al . Ginger polysaccharides relieve ulcerative colitis via maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and gut microbiota modulation. Int J Biol Macromol. (2022) 219:730–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.032,

13.

Wang J Chen Y Hu X Feng F Cai L Chen F . Assessing the effects of ginger extract on polyphenol profiles and the subsequent impact on the fecal microbiota by simulating digestion and fermentation in vitro. Nutrients. (2020) 12:3194. doi: 10.3390/nu12103194,

14.

Zahoor A Yang C Yang Y Guo Y Zhang T Jiang K et al . 6-Gingerol exerts anti-inflammatory effects and protective properties on LTA-induced mastitis. Phytomedicine. (2020) 76:153248. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153248,

15.

Alhamoud Y Ahmad MI Abudumijiti T Wu J Zhao M Feng F et al . 6-gingerol, an active ingredient of ginger, reshapes gut microbiota and serum metabolites in HFD-induced obese mice. J Funct Foods. (2023) 109:105783. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2023.105783

16.

Chang T-S Ding H-Y Wu J-Y Lin H-Y Wang T-Y . Glycosylation of 6-gingerol and unusual spontaneous deglucosylation of two novel intermediates to form 6-shogaol-4′-O-β-glucoside by bacterial glycosyltransferase. Appl Environ Microbiol. (2024) 90:e00779–24. doi: 10.1128/aem.00779-24,

17.

Narrowe AB Lemons JM Mahalak KK Firrman J Abbeele PV Baudot A et al . Targeted remodeling of the human gut microbiome using Juemingzi (Senna seed extracts). Front Cell Infect Microbiol. (2024) 14:1296619. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2024.1296619,

18.

Firrman J Narrowe A Liu L Mahalak K Lemons J den Van Abbeele P et al . Tomato seed extract promotes health of the gut microbiota and demonstrates a potential new way to valorize tomato waste. PLoS One. (2024) 19:e0301381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0301381,

19.

Firrman J Friedman ES Hecht A Strange WC Narrowe AB Mahalak K et al . Preservation of conjugated primary bile acids by oxygenation of the small intestinal microbiota in vitro. MBio. (2024) 15:e00943-24. doi: 10.1128/mbio.00943-24,

20.

den Van Abbeele P Deyaert S Thabuis C Perreau C Bajic D Wintergerst E et al . Bridging preclinical and clinical gut microbiota research using the ex vivo SIFR(®) technology. Front Microbiol. (2023) 14:1131662. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1131662,

21.

De Weirdt R Possemiers S Vermeulen G Moerdijk-Poortvliet TC Boschker HT Verstraete W et al . Human faecal microbiota display variable patterns of glycerol metabolism. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. (2010) 74:601–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00974.x,

22.

Callahan BJ McMurdie PJ Rosen MJ Han AW Johnson AJA Holmes SP . DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. (2016) 13:581–3. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869,

23.

Bolyen E Rideout JR Dillon MR Bokulich NA Abnet CC Al-Ghalith GA et al . Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. (2019) 37:852–7. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9,

24.

Quast C Pruesse E Yilmaz P Gerken J Schweer T Yarza P et al . The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. (2012) 41:D590–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219,

25.

Bokulich NA Kaehler BD Rideout JR Dillon M Bolyen E Knight R et al . Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. (2018) 6:90. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z,

26.

Paradis E Schliep K . Ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics. (2019) 35:526–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty633,

27.

Wickham H Averick M Bryan J Chang W McGowan LDA François R et al . Welcome to the Tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. (2019) 4:1686. doi: 10.21105/joss.01686

28.

Douglas GM Maffei VJ Zaneveld JR Yurgel SN Brown JR Taylor CM et al . PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat Biotechnol. (2020) 38:685–8. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6,

29.

Nickols WA Kuntz T Shen J Maharjan S Mallick H Franzosa EA et al . MaAsLin 3: refining and extending generalized multivariable linear models for meta-omic association discovery. bioRxiv. (2024). doi: 10.1101/2024.12.13.628459,

30.

Martinez Arbizu P. . pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise multilevel comparison using adonis. R package version 0.4 (2020) Available online at: https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis. (Accessed December 16, 2025).

31.

Wang Y Yu H Zhang X Feng Q Guo X Li S et al . Evaluation of daily ginger consumption for the prevention of chronic diseases in adults: a cross-sectional study. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif). (2017) 36:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.05.009,

32.

Ling Z Liu X Cheng Y Yan X Wu S . Gut microbiota and aging. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2022) 62:3509–34. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1867054,

33.

Abdullah Ahmad N Xiao J Tian W Khan NU Hussain M et al . Gingerols: preparation, encapsulation, and bioactivities focusing gut microbiome modulation and attenuation of disease symptoms. Phytomedicine. (2025) 136:156352. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156352

34.

Wang K Kong L Wen X Li M Su S Ni Y et al . The positive effect of 6-gingerol on high-fat diet and streptozotocin-induced Prediabetic mice: potential pathways and underlying mechanisms. Nutrients. (2023) 15:824. doi: 10.3390/nu15040824,

35.

Mahalak KK Narrowe AB Liu L Firrman J Lemons JM Van den Abbeele P et al . The ex vivo effects of ethanolic extractions of black cumin seed, turmeric root, and Ceylon cinnamon bark on the human gut microbiota. PLoS One. (2025) 20:e0334824.

Summary

Keywords

6-gingerol, ginger, gut microbiome, polyphenols, short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs)

Citation

Mahalak KK, Narrowe AB, Firrman J, Lemons JMS and Liu L (2026) The ginger polyphenol 6-gingerol elicits minimal changes in an ex vivo human gut microbiome. Front. Nutr. 12:1711783. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2025.1711783

Received

23 September 2025

Revised

04 December 2025

Accepted

10 December 2025

Published

26 January 2026

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

J. Fernando Ayala-Zavala, National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), Mexico

Reviewed by

Tingying Jiao, Fudan University, China

Suresh Kumar, National Institute of Biologicals, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Mahalak, Narrowe, Firrman, Lemons and Liu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karley K. Mahalak, karley.mahalak@usda.gov

†PRESENT ADDRESS: Johanna M. S. Lemons The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.