- 1Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Marine Bioresources and Environment, Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Marine Biotechnology, Jiangsu Ocean University, Lianyungang, China

- 2Co-Innovation Center of Jiangsu Marine Bio-industry Technology, Jiangsu Ocean University, Lianyungang, China

- 3Clinical Nutrition Department, Children’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

- 4College of Food Science and Light Industry, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing, China

In aquaculture, the overuse of antibiotic could lead to antimicrobial resistance and destabilize host–microbiota homeostasis. Latilactobacillus sakei, belonging to the genus Latilactobacillus, was included in the list of bacteria that could be used in food in China in 2014. Increasing evidence demonstrated that its antagonistic capacity against a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacteria, indicating its promising potential for application in aquaculture. In this study, the protective effect of three L. sakei (JO12, JO26, JO35), isolated from the intestine of fish and shrimp, on mucosal injury caused by Aeromonas hydrophila in crucian carp under an oral challenge model was investigated. The result showed that compared with LGG, all three L. sakei strains alleviated A. hydrophila induced intestinal barrier damage and inflammation (downregulated intestinal TNF-α/IL-1β, upregulated IL-10, and reduced MyD88) in crucian carp. L. sakei JO35 delivered the greatest improvement in growth and feed efficiency. Compared with the model group, L. sakei JO26 and JO35 significantly decreased the levels of serum acid phosphatase (ACP) and increased intestinal lysozyme, whereas L. sakei JO12 lowerd serum ACP but exacerbated the elevation of intestinal AKP. Microbiome and transcriptome analysis revealed that the protective effect of L. sakei may be associated with the strain’s intestinal colonization capacity and its regulation of phagolysosomal competence (lysosome/phagosome, LAMP) and IgA barrier via pIgR (prominent with JO35).

1 Introduction

With the rapid growth of the global population and the escalating demand for food security, aquaculture has become a vital component in securing sustainable protein sources for humanity. According to data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global aquatic product output reached 179 mill54ion tons in 2022, with farmed aquaculture accounting for over 55% of this total for the first time—a landmark transition from reliance on wild fisheries toward the sustainable cultivation of aquatic resources (1). Aquatic products are characterized by high protein content, low fat levels, and a rich profile of essential amino acids and trace elements, serving as a primary dietary protein source for approximately 3 billion people worldwide, a role that is especially critical in developing countries (2). Furthermore, these products are abundant in micronutrients such as calcium, iron, and vitamin A, which are essential for preventing deficiency-related diseases (3). Notably, the presence of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, including docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), contributes to cardiovascular health and supports neurodevelopment and visual function (4). According to the 2022 China Fisheries Yearbook, China’s total aquatic product output had reached 68.659 million tons, with aquaculture contributing 55.655 million tons, representing 81.06% of the total (5). Jiangsu Province, a leading aquaculture region in China, produced 1.243 million tons of aquatic products in 2023, consistently ranking among the top producers nationwide. The province’s distinctive aquaculture systems include ecologically optimized shrimp-crab polyculture, pond-based healthy freshwater fish farming, and integrated marine shrimp-crab-shellfish cultivation (6).

Despite the high yield and profitability of current aquaculture practices, this model has contributed to significant environmental degradation, including the accumulation of nutrients and organic matter in aquatic systems, which promotes the proliferation of pathogenic bacteria and frequent disease outbreaks among cultured species (7). Bacterial infections are a major cause of economic losses in aquaculture, severely undermining the sector’s profitability. Predominant bacterial pathogens in fish farming include species of Vibrio, Aeromonas, Edwardsiella, Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Micrococcus (8). To mitigate these losses, antibiotics such as sulfonamides, tetracyclines, quinolones, and β-lactams are commonly administered to enhance survival rates in aquatic animals (9). However, the widespread and often inappropriate use of antibiotics has driven the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria within aquaculture environments (10). These resistant bacteria and associated resistance genes pose a significant public health risk, as they can be transmitted to humans via the food chain or through direct contact (11). Furthermore, antibiotic misuse disrupts the gut microbiota of aquatic animals, leading to dysbiosis characterized by diarrhea, bloating, intestinal inflammation, and impaired immune function (12).

.Recent studies have demonstrated that targeted probiotic supplementation across diverse aquaculture species enhances growth performance, optimizes gut microbiota composition, strengthens innate and adaptive immune functions, and improves disease resistance, underscoring probiotics as effective antibiotic alternatives in intensive systems (13). For instance, dietary supplementation with Bacillus subtilis W2Z enhanced crayfish resistance to Aeromonas hydrophila by increasing activities of immune-related enzymes and improving intestinal microbiota composition (14). At a dietary concentration of 108 CFU/g, Clostridium butyricum significantly improved growth performance, beneficially reshaped the gut microbiota, modulated immune markers (downregulating IL-1β, IL-8, NF-κB, MyD88, and TNF-α while increasing serum lysozyme and IgM), and increased resistance to A. salmonicida in triploid rainbow trout (15). Zhang et al. isolated four Bacillus strains with broad-spectrum antibacterial activity from healthy crucian carp; these strains enhanced innate intestinal immunity by reducing pathogenic colonization (16). Similarly, Tan et al. isolated a Staphylococcus sp. from Nile tilapia and demonstrated that diets containing this strain improved growth, immunity, disease resistance, and overall intestinal health (17). Moreover, diets supplemented with Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) preserved intestinal barrier integrity in red tilapia, enhanced immune capacity, and improved growth and health status, supporting the direct inclusion of LGG in aquafeeds as a nutritional supplement (18).

Latilactobacillus sakei, belonging to the genus Latilactobacillus, was first described by Katagiri et al. (19). It is a lactic acid bacterium and was included in China’s list of edible microbial species in 2014, recognizing its safety and suitability for use in food and related applications. It is widely distributed in fermented foods, including flour (20), sourdough (21), fermented cabbage, sausage, sake, as well as in natural environments (22). Research has shown that it is one of the dominant bacterial species in meat products (23). L. sakei exhibits a range of probiotic functions, including inhibiting the growth of pathogenic bacteria, modulating the host immune system, enhancing intestinal barrier function, and improving gut microbiota balance. A growing body of research has demonstrated that L. sakei can produce a series of bacteriocins (24) and displays strong antagonistic activity against Listeria monocytogenes (25) and Staphylococcus aureus (26). For instance, L. sakei L115 exhibited inhibitory activity against Listeria monocytogenes, achieving a 31% reduction in the maximum specific growth rate and a 36% decrease in the maximum population density at 4 °C (27). Another study showed that L. sakei 1,018 in vacuum-packaged beef significantly inhibited the recovery of Escherichia coli throughout the entire storage period following high-pressure processing (28). Reyes-Becerril et al. reported that L. sakei 5–4 exerted a significant ameliorative effect on physiological and inflammatory markers in Carassius auratus infected with A. hydrophila (29). Further studies by the same group demonstrated that L. sakei supplementation improved the immune status and antioxidant capacity of Lutjanus peru (30). L. sakei MN1 was also reported to competitively inhibit the colonization of Vibrio anguillarum in the zebrafish gut by occupying adhesion sites (31).

Despite mounting evidence supporting probiotics as viable antibiotic alternatives in aquaculture, strain- and host-specific efficacy remains insufficiently characterized, particularly for L. sakei in freshwater cyprinids. Given L. sakei’s documented antimicrobial activity, immunomodulatory effects, and capacity to stabilize intestinal microbiota across food systems and selected marine and model fish species, its targeted application in crucian carp warrants systematic evaluation. In this study, we investigated the effects of dietary L. sakei strains (JO12, JO26, JO35), compared with LGG, on growth performance, non-specific immunity, resistance to A. hydrophila, gut microbial composition, and intestinal transcriptomic profiles in Carassius auratus.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial species and culture conditions

Aeromonas hydrophila was cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 28 °C. L. sakei strains JO12, JO26, and JO35 were isolated from the intestinal contents of fish and shrimp. LGG was used as the positive control strain. All Lactobacilli were cultured in MRS medium at 37 °C and preserved in glycerol tubes at −80 °C.

2.2 Antimicrobial assay

The A. hydrophila strain was streaked onto LB agar and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h to obtain single colonies. A single colony was then inoculated into LB broth to prepare a bacterial suspension, and the optical density was adjusted to OD600 nm = 0.5 by spectrophotometry. Meanwhile, L. sakei strains JO12, JO26, JO35, and LGG were revived from −80 °C stocks and subcultured twice for activation. Second-passage cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 18 h, and the suspensions were standardized to 1 at OD600 nm = 1.0. Sterile Petri dishes were prepared under a laminar flow hood by pouring 15–18 mL of LB broth agar and allowing it to solidify. Subsequently, 100 μL of the A. hydrophila suspension was evenly spread onto the agar surface. Sterilized Oxford cups were gently placed on the inoculated plates, and 200 μL of each Lactobacilli suspension in MRS broth (OD600 nm = 1.0) was carefully pipetted into the corresponding Oxford cups. Plates were incubated upright at 37 °C for 18 h. Following incubation, the diameters of the inhibition zones around each cup were measured and recorded. All assays were performed in triplicate.

2.3 Animal models

All procedures involving animals were approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Ocean University, China [NO: Jou2024032411 (3)]. A total of 120 crucian carp (Carassius auratus) with an average body length of 8.3 ± 0.3 cm were used. 120 fish were randomly assigned to six groups (PBS, PBS + AH, JO12 + AH, JO26 + AH, JO35 + AH, LGG + AH) and housed in six glass tanks (80 × 50 × 50 cm), each equipped with a closed recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) in glass tanks under laboratory conditions (24 ± 1 °C, 12 h light/12 h dark photoperiod) for 2 weeks. During the adaption period, all fish were fed a commercial diet at 2% of body weight, twice daily. Throughout the experiment, water quality parameters were monitored daily, maintaining pH 7.8 ± 0.5, ammonia nitrogen <0.5 mg/L, nitrite <0.05 mg/L, and dissolved oxygen at approximately 7.0 mg/L. After the adaptation period, fish in the six groups were fed diets containing PBS or L. sakei strains (2 × 109 CFU/g) for 8 weeks. Then, each group was orally gavage of 200 μL sterile PBS or A. hydrophila (2 × 108 CFU per fish) for seven consecutive days. The animal experimental design is shown in Figure 1 and the experimental procedures were performed as previously described (32).

2.4 Growth performance measurement

During the animal experiment, the following growth performance parameters were recorded for each group of crucian carp: initial average body weight (g), final average body weight (g), initial average body length (cm), final average body length (cm), weight gain rate (WGR, %), specific growth rate (SGR, %/d), feed converson ratio (FCR), and condition factor (CF, %). The indices were calculated as follows:

• Initial average body weight (g) = Initial total weight/Initial number of fish.

• Final average body weight (g) = Final total weight/Final number of fish.

• Initial average body length (cm) = Initial total length/Initial number of fish.

• Final average body length (cm) = Final total length/Final number of fish.

• Weight gain rate (WGR, %) = (Final total weight–Initial total weight)/Initial total weight × 100.

• Specific growth rate (SGR, %/d) = [ln (Final average body weight)–ln (Initial average body weight)]/Experimental days × 100.

• Feed conversion ratio (FCR) = Feed intake/(Final average body weight–Initial average body weight).

• Condition factor (CF, %) = (Final body weight / (Final body length)3) × 100.

2.5 Sample collection

After the infection experiment, all fish were anesthetized with 300 mg/L tricaine methane sulfonate (MS-222). Blood samples were collected from the caudal vein using disposable 1 mL syringes pre-moistened with heparin sodium solution (2,800 U/mL). The collected blood was kept in the dark at room temperature for 1 h and then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. Serum was transferred to 2 mL microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −20 °C for subsequent biochemical analyses. Following dissection, three fish per group were selected. A 1 cm segment of mid-intestine was excised and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histology. The remaining intestinal tissues were placed in 2 mL cryovials, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for non-specific immune assays and transcriptomic analysis. Intestinal contents were collected by gentle extrusion, transferred to 2 mL cryovials, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for gut microbiota diversity profiling and sequencing.

2.6 Histological assessment

Mid-intestinal tissue samples (approximately 5 mm) were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered paraformaldehyde, dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Sections 4 μm thick were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). The stained sections were air-dried for 2 weeks and then examined under a light microscope. Tissue morphology was evaluated at multiple magnifications (33).

2.7 Analysis of biochemical indicators

To assess biochemical parameters in the serum and intestinal tissues of A. hydrophila–infected crucian carp fed with L. sakei, approximately 1 cm of intestinal tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of RIPA lysis buffer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. Total protein concentration was determined using a protein assay kit (Shanghai Yuanye Bio, China). The activities of alkaline phosphatase (AKP), acid phosphatase (ACP), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were measured with the corresponding enzyme assay kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering, China). Lysozyme (LZM) activity was quantified using a lysozyme assay kit (Shanghai Meilian Bio, China). The activities of LZM, ACP, AKP, and AKP in intestinal tissues were normalized to protein content and expressed as units per gram of protein (U/gprot). Serum LZM, ACP, AKP, and ALT activities were expressed as units per milliliter of serum (U/mL).

2.8 Cytokine assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Shanghai Keqiao Bio, China) specifically developed and validated for fish were used to quantify tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-10 (IL-10), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88) in serum and intestinal tissues. The ELISA kits were fish TNF-α ELISA kit (KQ114000), fish IL-1β ELISA kit (KQ139942), fish IL-10 ELISA kit (KQ109400), fish IFN-γ ELISA kit (KQ109401), and fish MyD88 ELISA kit (KQ124877). The ELISAs employed a double-antibody sandwich format. Microplates were pre-coated with purified capture antibodies. Samples were added to the wells, followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated detection antibodies, forming an antibody–antigen–HRP complex. After thorough washing, tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate was added for color development. TMB was catalyzed by HRP to produce a blue product that turned yellow upon acidification. Color intensity was directly proportional to the cytokine concentration in the sample. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader, and cytokine concentrations were calculated from standard curves.

2.9 Determination of intestinal flora

A 0.05 g aliquot of each intestinal content sample was mixed with magnetic beads and homogenized using a tissue disruptor. Bacterial DNA was extracted, and the V3–V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and purified. A sequencing library was then constructed from the amplicons, and paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina platform. Raw reads underwent quality control, including merging and filtering, followed by operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering or amplicon sequence variant (ASV) denoising. Alpha- and beta-diversity analyses were performed using QIIME 2 (34).

2.10 Transcriptome analysis

Total RNA was extracted from a 0.05 g portion of each intestinal tissue sample, and mRNA was enriched. The mRNA was fragmented, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer primers, and second-strand cDNA was subsequently synthesized. After end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, fragment selection, amplification, and purification, the sequencing library was prepared. The library was quantified, and fragment size distribution was assessed. Libraries that passed quality control were pooled according to effective concentration and target sequencing depth, and sequenced on an Illumina platform. Raw reads were processed with fastp to obtain high-quality clean reads. Clean data quality metrics (Q20, Q30) and GC content were evaluated. The reference genome index was built using HISAT2 (v2.0.5), and paired-end clean reads were aligned to the reference genome with HISAT2 (v2.0.5). Novel gene prediction was performed using StringTie (v1.3.3b). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were analyzed for Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment using clusterProfiler (v3.8.1), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis was conducted to identify functionally significant pathways (35).

2.11 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses and graphical representations were performed using GraphPad Prism (v8.02; San Diego, CA, United States). Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to assess normality, and Levene’s test was used to evaluate homogeneity of variances. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc pairwise comparisons, was conducted to determine significant differences between groups.

3 Results

3.1 Antagonistic activity of Latilactobacillus sakei against Aeromonas hydrophila

Based on our prior experiments, 30 L. sakei strains (JO12, JO16, JO21, JO26, JO29, JO34, JO35, JO41, JO48, JO61, JO62, JO63, JO64, JO94, JO95, JO97, JO101, JO102, JO104, JO105, JO106, JO113, JO114, JO115, JO117, JO118, JO123, JO141, JO142 and JO312) isolated from the intestinal contents of fish and shrimp were initially screened for in vitro antagonistic activity against A. hydrophila. Among these, three L. sakei strains (JO12, JO26 and JO35) with the strongest antagonistic activity against A. hydrophila, along with LGG, were selected for evaluation. Antagonistic activity was assessed using the Oxford cup assay, and the results are presented in Table 1. All strains exhibited measurable inhibitory effects. The Inhibition zones of the three L. sakei strains were greater than 15 mm, with no significant differences among them. The antibacterial ability of all three L. sakei strains was higher than that of LGG.

3.2 Effects of Latilactobacillus sakei on the growth performance of crucian carp

The growth parameters of crucian carp in all groups are presented in Table 2. All probiotic treatments improved the weight gain rate (WGR) of crucian carp relative to the PBS and PBS + AH controls. L. sakei JO35 significantly increased both WGR and specific growth rate (SGR), outperforming all other groups. L. sakei JO12 and L. sakei JO26 also significantly enhanced WGR and SGR compared with the PBS and PBS + AH treatments. Crucian carp treated with L. sakei JO35 exhibited the lowest feed conversion ratio (FCR), and L. sakei JO12 and L. sakei JO26 likewise reduced FCR relative to PBS and PBS + AH. The condition factor (CF) did not differ significantly among groups.

3.3 Effect of Latilactobacillus sakei on the intestinal histological structure of crucian carp

As shown in Figure 2, the layered architecture of the intestinal tissue in the PBS group was clear and intact, with an undamaged mucosal epithelium. Goblet cells were distinctly distributed, and no inflammatory cell infiltration was observed in the submucosa. In the PBS + AH group, mucosal edema was evident, accompanied by inflammatory cell infiltration in the mucosa and submucosa. Treatment with L. sakei JO12, JO26, and JO35 alleviated mucosal edema and reduced lymphocytic infiltration in the intestines of crucian carp. By contrast, the intestinal tissue of fish treated with LGG showed fewer goblet cells, mucosal swelling, epithelial injury, and more pronounced inflammatory cell infiltration compared with the PBS group.

Figure 2. Effect of L. sakei on the intestinal histological structure of Crucian carp (a–f): PBS group (a), PBS + AH group (b), JO12 + AH group (c), JO26 + AH group (d), JO35 + AH group (e), and LGG + AH group (f).

3.4 Effect of Latilactobacillus sakei on biochemical indexes in the serum and intestine of crucian carp

The effects of L. sakei on lysozyme, acid phosphatase (ACP), alkaline phosphatase (AKP), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in the serum and intestines of crucian carp infected with A. hydrophila were evaluated, as shown in Figure 3. Compared with the PBS group, A. hydrophila infection caused a significant increase in intestinal AKP, whereas intestinal lysozyme, ACP, and ALT did not change markedly. Relative to the PBS + AH group, L. sakei JO35 significantly increased serum lysozyme and ACP, while L. sakei JO12 and JO26 significantly increased serum lysozyme. In the serum, A. hydrophila infection significantly increased ACP and AKP levels and did not alter lysozyme or ALT. Treatment with L. sakei JO12, JO26, JO35, and LGG reduced serum ACP in A. hydrophila–infected fish. Moreover, L. sakei JO12 and JO35 significantly increased serum lysozyme levels in infected crucian carp (Figure 3).

Figure 3. (a) Biochemical indexes in intestinal tissues (enzyme activities were normalized to protein content and expressed as U/g prot); (b) biochemical indexes in serum of crucian carp (enzyme activities were expressed as U/mL); LZM, lysozyme; ACP, acid phosphatase; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alglutamyltransferase.

3.5 Effect of Latilactobacillus sakei on the expression of intestinal inflammatory factors in crucian carp

The levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-10 (IL-10), myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88), and tumor necrosis factor-AKPha (TNF-α) in intestinal tissue were quantified. As shown in Figure 4, A. hydrophila infection (PBS + AH) elicited a robust pro-inflammatory response, evidenced by significant increases in TNF-α, IL-1β and MyD88 relative to PBS controls, along with decreases in IL-10 and IFN-γ. Supplementation with L. sakei markedly attenuated this pro-inflammatory surge. All tested L. sakei strains reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ compared with the PBS + AH group. Concomitantly, L. sakei JO12, JO26, and JO35 increased the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the intestines of infected fish, indicating that probiotic intervention alleviated A. hydrophila–induced intestinal inflammation. MyD88, a key adaptor in TLR signaling, was significantly upregulated by infection but was downregulated by L. sakei JO12, JO26, and JO35, suggesting mitigation of TLR–MyD88–dependent inflammatory signaling.

Figure 4. Effect of L. sakei on the expression of intestinal inflammatory factors of crucian carp (a–e).

3.6 Effect of Latilactobacillus sakei on the intestinal flora of crucian carp

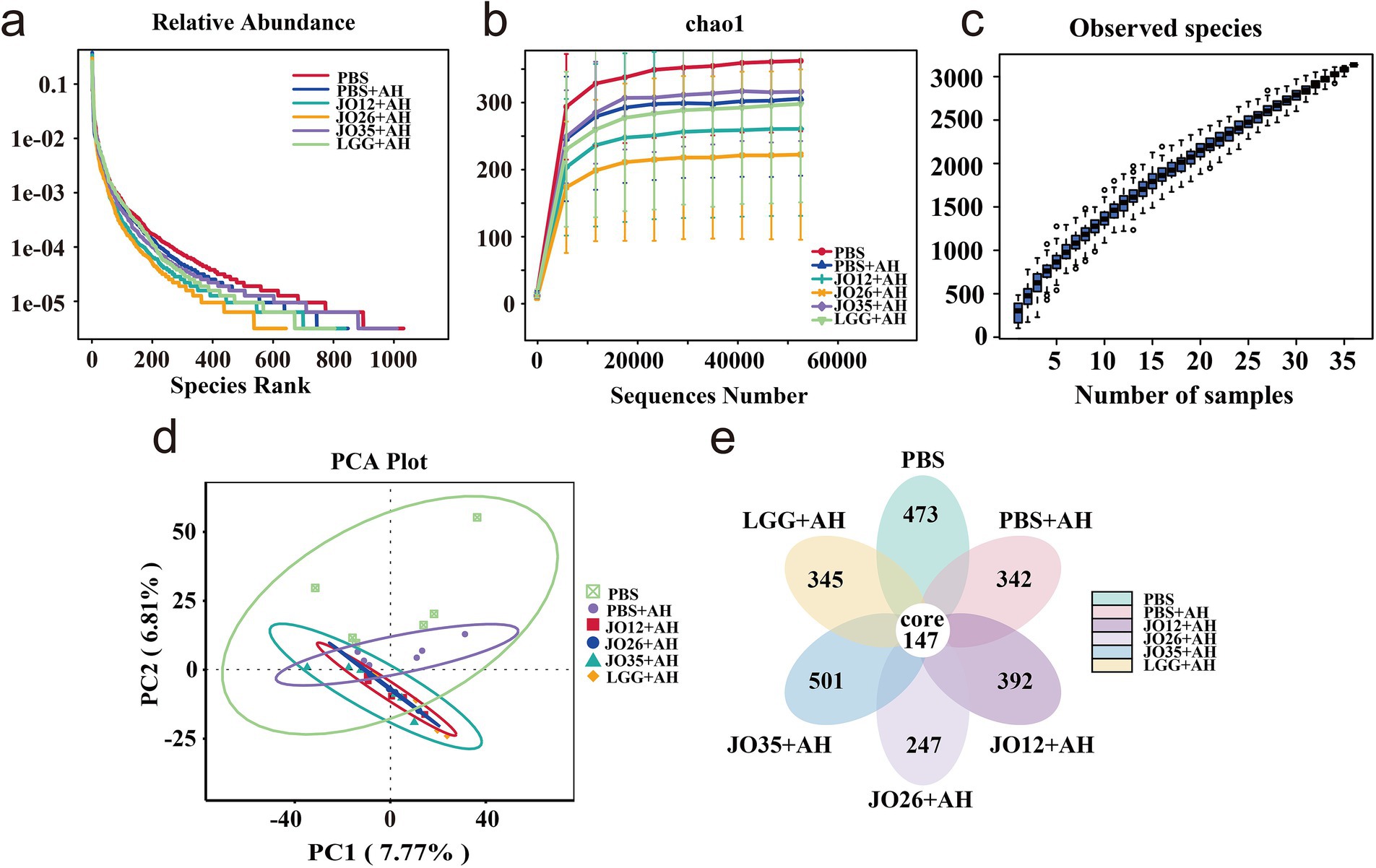

As shown in Figure 5, rarefaction curves plateaued for all groups, and species accumulation increased smoothly without sharp rises, indicating adequate sequencing depth and sample size for robust diversity assessment. The PBS group displayed the widest, flattest Chao1 curve, reflecting greater richness and evenness. Infection with A. hydrophila (PBS + AH) reduced both metrics and shifted community structure, as evidenced by clear separation from PBS in PCA space. A Venn diagram revealed 147 core features shared across groups. The number of unique features was highest in JO35 + AH and PBS, intermediate in JO12 + AH and PBS + AH, and lowest in JO26 + AH and LGG + AH, supporting a diversity-preserving effect most pronounced for L. sakei JO35.

Figure 5. Sequencing depth and diversity analysis based on OTUs. (a) Rarefaction curve, the horizontal coordinate is the number of sequencing strips randomly selected from the samples, the vertical coordinate is the number of OTUs obtained based on the number of sequencing strips, and different samples are represented by using different colored curves; (b) Chao1 curve, the horizontal coordinate is the ordinal number sorted by the abundance of OTUs, the vertical coordinate is the relative abundance of the corresponding OTUs, different samples are represented using different colored dash lines; (c) Species accumulation curve; (d) PCA plot; (e) Vene diagram.

As shown in Figure 6, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) bar plots and column charts indicate 21 dominant OTUs across the six groups. At the phylum level, the gut microbiota was dominated by Fusobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidota, and Firmicutes across groups. Infection with A. hydrophila increased Proteobacteria, whereas L. sakei JO12 (12.69%), JO26 (13.67%), and JO35 (17.41%) reduced Proteobacteria levels in the intestines of crucian carp. Compared with the PBS group, A. hydrophila infection increased the relative abundance of Bacteroidota, whereas supplementation with L. sakei JO35 reduced Bacteroidota levels. Firmicutes decreased markedly in the intestines of crucian carp after A. hydrophila infection across all treatment groups compared with PBS. At the genus level, Cetobacterium constituted more than 40% of the community in all groups, with the highest relative abundance in JO12 + AH (61.01%) and the lowest in LGG + AH (43.75%). In the PBS group, Bacteroides accounted for 2.99%, whereas the proportions in PBS + AH, JO12 + AH, JO26 + AH, JO35 + AH, and LGG + AH were 8.84, 12.31, 16.89, 6.08, and 16.27%, respectively. The abundance of Aeromonas, a key pathogen indicator, was reduced most effectively by L. sakei JO12 (3.64%) and JO35 (5.42%) compared with PBS + AH (7.06%), but was higher in JO26 + AH (8.43%) and LGG + AH (11.20%).

Figure 6. Effect of L. sakei on the intestinal flora of crucian carp. (a) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) bar plot; (b) Column diagram of microbial composition (LEFSE analysis); (c) Diagram of the composition of the overall flora structure based on the phylum level; (d) Diagram of the composition of the overall flora structure based on the genus level.

T-test analysis of the intestinal flora at the genus level showed that the PBS group had higher abundances of ZOR0006 and several putatively beneficial or environmental genera (e.g., Rhizobium, Rhodobacter, Phreatobacter), whereas the PBS + AH group was enriched in Acinetobacter and Succinatimonas (originally “Succinisipra”). Compared with the PBS + AH group, L. sakei JO12 significantly increased the abundance of Latilactobacillus in the intestine of crucian carp. L. sakei JO35 markedly increased the abundances of Aurantimicrobium, Rhizobium, Pseudorhodobacter, Phreatobacter (corrected from “Phrestobacter”), and Latilactobacillus. All three strains—L. sakei JO12, JO26, and JO35—attenuated the A. hydrophila–induced increase in Acinetobacter. LGG significantly increased the abundance of Rhodobacter. Latilactobacillus abundance was significantly higher in the JO12 + AH and JO35 + AH groups than in PBS + AH, with non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals and p-values below 0.05 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. T-text analysis of the intestinal flora of crucian carp based on genus level. (a) PBS vs. PBS + AH; (b) PBS + AH vs. JO12 + AH; (c) PBS + AH vs. JO26 + AH; (d) PBS + AH vs. JO35 + AH; (e) PBS + AH vs. LGG + AH; (f) Abundance of Latilactobacillus in JO12 + AH and JO35 + AH group.

3.7 Effect of Latilactobacillus sakei on the expression of transcriptional genes in the intestinal contents of crucian carp

In Figure 8A, biological replicates clustered tightly with Pearson R2 values predominantly ≥0.95 within each treatment, confirming robust sequencing quality, whereas between-group correlations were lower, consistent with treatment-specific transcriptional programs. In Figure 8B, samples in the PBS + AH group separated strongly from those in the PBS group, indicating that A. hydrophila infection induced profound alterations in the intestinal transcriptomic landscape of crucian carp. Samples in the JO12 + AH and JO35 + AH groups shifted away from PBS + AH and toward PBS, while samples in the JO26 + AH and LGG + AH groups occupied intermediate positions, suggesting partial remediation. Consistent with these results, Figure 8c showed that A. hydrophila infection (B vs. A) yielded the largest number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Relative to PBS + AH, JO12 + AH and JO35 + AH displayed higher total DEG counts (with balanced up- and down-regulation), reflecting broader host regulatory effects, whereas JO26 + AH and LGG + AH exhibited fewer changes, indicative of weaker modulation. Figure 8d demonstrated a substantial core of infection-responsive genes shared among all infected groups. Notably, JO12 + AH and JO35 + AH possessed larger pools of unique DEGs and greater overlap with samples in the PBS group than with PBS + AH. Collectively, L. sakei JO12 and JO35 exerted the most pronounced corrective effects on A. hydrophila–induced dysregulation of the intestinal transcriptome in crucian carp, followed by LGG and L. sakei JO26.

Figure 8. Effect of L. sakei on the transcriptional gene expression in the intestinal contents of crucian carp. (a) Heatmap of inter-sample peaeson correlation; (b) PCA plot of global gene expression; (c) Histogram of differentially expressed gene counts per pairwise comparison (up- and downregulated genes); (d) Vene diagrams of shared and unique differentially expressed genes among groups.

The top 20 significantly enriched KEGG pathways for each pairwise comparison are shown in Figure 9. In Figure 9A, A. hydrophila infection elicited pronounced enrichment of innate immune and inflammatory pathways concomitant with metabolic reprogramming in crucian carp, including lysosome, phagosome, PPAR signaling, FoxO signaling, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, multiple amino acid and carbohydrate metabolic pathways, as well as retinol metabolism and ferroptosis-related processes. Relative to PBS + AH group, Figure 8B showed that L. sakei JO12 supplementation significantly enriched pathways in PPAR signaling, lysosome, glycosaminoglycan degradation, carbon metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation. L. sakei JO26 supplementation significantly enriched Toll-like receptor signaling, C-type lectin receptor signaling, PPAR signaling, amino acid and carbohydrate metabolic and drug metabolism (cytochrome P450). L. sakei JO35 supplementation significantly enriched peroxisome, PPAR signaling and multiple amino acid metabolic pathways. LGG supplementation significantly enriched efferocytosis, lysosome and nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism (Figure 10).

Figure 9. Bubble chart of top 20 significantly enriched KEGG pathways for each pairwise comparison: (a) PBS vs. PBS + AH; (b) PBS + AH vs. JO12 + AH; (c) PBS + AH vs. JO26 + AH; (d) PBS + AH vs. JO35 + AH; (e) PBS + AH vs. LGG + AH.

Figure 10. Differentially expressed genes enriched in key immune and metabolic pathways. Green indicating consistent downregulation in all three samples, red indicating consistent upregulation in all three samples, and yellow indicating inconsistent changes across samples.

Differentially expressed genes involved in the lysosome pathway (ko04142), the intestinal immune network for IgA production (ko04672), and the phagosome pathway (ko04145) for each pairwise comparison are shown in Figure 9. Compared with the PBS group, A. hydrophila infection markedly upregulated the expression of genes in lysosomal components (LGMN, TPP1, GALC, GUSB, LAMAN, NEU1, GNS, and LYRLA3), membrane transporters (ABCA2), and associated factors (saposin, CLN5, MCOLN1, and LITAF family members), as well as phagosomal components (Rab5/7, RILP, v-ATPase, CALR, and calnexin) and an IgA-axis node (CXCR4) in the intestine of crucian carp. Supplementation with L. sakei JO12 markedly attenuated the A. hydrophila–induced upregulation of these intestinal transcripts, including genes associated with lysosomal components (LGMN, TPP1, GALC, GUSB, LAMAN, NEU1, GNS, LYRLA3, and LITAF) and phagosomal components (Rab5, RILP, and CALR). L. sakei JO35 exhibited the most pronounced restorative effect, promoting downregulation of genes associated with lysosomal (LAMP) and phagosomal (TAP, MHC II, and COLEC11) profiles. Moreover, L. sakei JO12, JO26, JO35, and LGG all increased the expression of multiple genes involved in IgA synthesis.

4 Discussion

Aeromonas hydrophila is among the most prevalent pathogens in aquaculture. Infection with A. hydrophila could disrupt the intestinal barrier of fish, precipitating dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, metabolic derangements, and ensuing systemic manifestations (36, 37). Antibiotic overuse in aquaculture has accelerated the emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance and frequently disrupts host–microbiota homeostasis, with consequences for fish health and potential spillover risks to humans via the food chain (38, 39). In this study, effect of three L. sakei strains (JO12, JO26, JO35) and LGG on A. hydrophila-infected crucian carp was determined. Growth, histology, serum and intestinal biochemical indices, cytokine profiles, 16S rRNA sequencing, and intestinal transcriptomics of crucian carp were measured. LGG was used as a positive control strain in this article. Our multidimensional design aligns with recent calls for mechanistic probiotic evaluation across host, microbiome, and molecular layers in aquatic species, moving beyond growth-only endpoints and toward causal axes of mucosal protection and immunometabolic reprogramming (40, 41).

First, in vitro antagonism established that all three L. sakei strains produced larger inhibition zones than LGG against A. hydrophila, suggesting a robust capacity to secrete antimicrobial metabolites and/or competitively interfere with pathogen growth (Table 1). Although Oxford cup assays do not fully recapitulate intestinal conditions (pH, bile, mucus, microbe–microbe interactions), these results justified in vivo testing. Following this, experimental diets supplemented with L. sakei JO12, JO26, and JO35, and with LGG, according to established feed preparation protocols were formulated. Fish were randomly allocated to the respective diet groups, with a commercial feed group serving as the control. Body length and body weight were recorded at baseline and at the end of the trial and growth performance was calculated using standard formulas (Table 2). In vivo, crucian carp receiving L. sakei JO35 displayed the highest weight gain rate and specific growth rate and the lowest feed conversion ratio. These findings indicate enhanced nutrient utilization and metabolic efficiency in the presence of L. sakei. These observations are consistent with recent Litopenaeus vannamei studies in which Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis improved growth via pathogen suppression and metabolic optimization (42). Differences between strains in our study likely reflect genomic determinants (bacteriocins, EPS architecture, adhesins) and acid/bile tolerance influencing colonization and metabolite output (43).

At the mucosal interface, histology demonstrated that A. hydrophila provoked mucosal edema and leukocytic infiltration, consistent with barrier disruption and active inflammation. L. sakei JO12, JO26 and JO35 alleviated these lesions, preserving goblet cells and mucosal architecture, whereas LGG failed to confer comparable protection in this model. Biochemical markers supported these findings and infection elevated intestinal ACP and AKP, markers linked to inflammatory activation and membrane transport remodeling, respectively. L. sakei broadly reduced serum ACP, JO12 and JO35 increased intestinal lysozyme, a key effector of innate antibacterial defense. In intestine, JO35 enhanced lysozyme and ACP, suggesting a systemic facet to the probiotic response. This pattern mirrored recent reports that LGG enhanced mucin production and attenuate epithelial damage under pathogen challenge in fish (44). The comparatively weaker performance of LGG in our study may underscore host- and context-specificity of probiotic action (45).

TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10, IFN-γ, and MyD88 were inflammation-related cytokines involved in innate immunity in the intestines of crucian carp (46, 47). A. hydrophila infection increased TNF-α and IL-1β and decreased IL-10 in the intestine of crucian carp. L. sakei JO12, JO26 and JO35 supplementation reversed these trends by lowering TNF-α and IL-1β across strains and elevating IL-10. MyD88 was a central adaptor for most Toll-like receptors and was reduced by all L. sakei strains in infected intestines of crucian carp. A mouse study reported that dietary administration of Lactobacillus agilis SNF7 reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and increased IL-10, suggesting a potential anti-inflammatory immunomodulatory capacity of Lactobacillus strains (48). However, extrapolation from mammals to teleost fish should be made cautiously, because mucosal immune organization and immunoglobulin isotypes differ substantially between species. Thus, mammalian findings are supportive but not directly transferable, and fish-specific mechanistic validation is required. In crucian carp, our result indicated a directionally similar shift toward controlled inflammation under L. sakei supplementation. In addition, feeding Lactobacillus delbrueckii ameliorated A. hydrophila–induced intestinal inflammation in crucian carp by downregulating the mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-8, TNF-α, and NF-κB p65 (49). This was consistent with the findings in our study.

Microbiome analyses revealed ecological hallmarks of disease and recovery. A. hydrophila infection increased Proteobacteria and reduced Firmicutes in the intestine of crucian carp echoing dysbiosis signatures linked to oxygen/ROS-driven bloom of facultative anaerobes and barrier permeability (50, 51). L. sakei supplementation reversed Proteobacteria expansion and suppressed Acinetobacter, an opportunistic, antibiotic-resistant genus, and only L. sakei JO35, reduced Bacteroidota (52). This trajectorie parallel recent fish studies demonstrating probiotic-driven suppression of Proteobacteria blooms and enrichment of beneficial commensals, often tied to restoration of hypoxic niches and reduction of epithelial oxygenation (53). Increased Latilactobacillus abundance in the intestine of crucian carp under L. sakei JO12 and JO35 groups supports direct niche establishment, while broader increases in beneficial taxa (Rhizobium lineage) may reflect cross-feeding and redox normalization in the gut ecosystem (54). Notably, only L. sakei JO12 and JO35, but not JO26 or LGG, significantly increased the intestinal abundance of Latilactobacillus in A. hydrophila–infected crucian carp. This discrepancy likely reflects strain-specific differences in intestinal colonization capacity, including adhesion to mucus and epithelial surfaces, resistance to bile salts and low pH, and ecological competitiveness within the resident microbiota. The rarefaction and PCA results confirm adequate sampling depth and a probiotic-driven community trajectory away from the dysbiotic state.

Our transcriptomic analysis identified DEGs predominantly enriched in immune and mucosal defense pathways, notably lysosome (ko04142), phagosome (ko04145), and the intestinal immune network for IgA production (ko04672). These signatures align with canonical PRR–PAMP recognition and downstream transcriptional activation of antimicrobial programs, consistent with host responses to pathogenic stimuli (55, 56). A. hydrophila infection markedly upregulated multiple lysosomal hydrolases and accessory factors, but selectively reduced the expression of LAMP family members, which are critical for phagosome–lysosome fusion. L. sakei JO26 prominently influenced TLR/C-type lectin receptor signaling and xenobiotic/drug metabolism. L. sakei LGG impacted lysosome and nicotinamide pathways but with weaker phenotypic rescue in the intestine of crucian carp. Supplementation with L. sakei JO26, JO35 and LGG restored LAMP expression, suggesting recovery of endolysosomal competence and more efficient resolution of infection (57). Complement-related readouts further supported enhanced opsonophagocytosis: JO26 increased iC3b, reinforcing CR3/CR4-dependent uptake. THBS1 (TSP1) was upregulated across probiotic groups, indicating immunoregulatory effects via CD36/CD47 that may aid controlled inflammation and tissue repair (58). L. sakei JO35 elevated IgA-related signatures and restored pIgR expression, strengthening epithelial transcytosis and sIgA-mediated immune exclusion at the lumen (55). Although IGH decreased in the JO12 group, the overall enhancement of the IgA network and pIgR points to a targeted, low-inflammation containment strategy rather than nonspecific humoral amplification. This study has limitations and causality between specific microbial changes and immune reprogramming requires validation via gnotobiotic or microbiota-transfer experiments in the future. Combinatorial or synbiotic formulations that potentiate JO35’s benefits may be also tested.

In conclusion, dietary L. sakei—particularly strain JO35—enhances growth performance, stabilizes intestinal microbial ecosystems, and restores mucosal immune homeostasis in crucian carp challenged with A. hydrophila. By reducing pathogen burden, reinforcing IgA-mediated exclusion, and reactivating lysosome–phagosome competence while tempering excessive TLR–MyD88 signaling, L. sakei provides a biologically coherent, antibiotic-sparing strategy to prevent and control enteric infections in aquaculture. These findings support the incorporation of L. sakei JO35 into standardized feeding protocols in aquatic animal aquaculture as an antibiotic-sparing probiotic to improve health and growth while limiting antimicrobial use. L. sakei JO12 ranked as a close second, L. sakei JO26 displayed selective advantages (complement opsonization via iC3b), and LGG’s effects were context-dependent and generally weaker in this model. Future work should test causality using gnotobiotic carp, targeted inhibition of TLR–MyD88 and PPAR pathways, and loss-of-function approaches for pIgR/LAMP orthologs. It will also be important to employ comparative genomics and secretomics to delineate strain-specific functional determinants.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1406500.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Ocean University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

YZ: Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Project administration. RL: Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. TZ: Supervision, Writing – original draft. HH: Visualization, Writing – original draft. GA: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. ZR: Visualization, Writing – original draft. JC: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. JJ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province [BK20230691], Open-end Funds of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Marine Bioresources and Environment [SH20191204], Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province [SY202339X1] and Open-end Funds of Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Marine Bioresources and Environment [SH20221202].

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Naylor, RL, Goldburg, RJ, Primavera, JH, Kautsky, N, Beveridge, MC, Clay, J, et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies. Nature. (2000) 405:1017–24. doi: 10.1038/35016500

2. Jaiswal, S, Rasal, KD, Chandra, T, Prabha, R, Iquebal, MA, Rai, A, et al. Proteomics in fish health and aquaculture productivity management: status and future perspectives. Aquaculture. (2023) 566:739159. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.739159

3. Maulu, S, Nawanzi, K, Abdel-Tawwab, M, and Khalil, HS. Fish nutritional value as an approach to children's nutrition. Front Nutr. (2021) 8:780844. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.780844,

4. von Schacky, C. Importance of EPA and DHA blood levels in brain structure and function. Nutrients. (2021) 13:1074. doi: 10.3390/nu13041074,

5. Bondad-Reantaso, MG, MacKinnon, B, Karunasagar, I, Fridman, S, Alday-Sanz, V, Brun, E, et al. Review of alternatives to antibiotic use in aquaculture. Rev Aquac. (2023) 15:1421–51. doi: 10.1111/raq.12786

6. Sun, Z, Luo, J, Xu, Y, Zhai, J, Cao, Z, Ma, J, et al. Coordinated dynamics of aquaculture ponds and water eutrophication owing to policy: a case of Jiangsu province, China. Sci Total Environ. (2024) 927:172194. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172194,

7. Aly, SM, and Fathi, M. Advancing aquaculture biosecurity: a scientometric analysis and future outlook for disease prevention and environmental sustainability. Aquac Int. (2024) 32:8763–89. doi: 10.1007/s10499-024-01589-y

8. Guo, S, Zhang, Z, and Guo, L. Antibacterial molecules from marine microorganisms against aquatic pathogens: a concise review. Mar Drugs. (2022) 20:230. doi: 10.3390/md20040230,

9. Van Boeckel, TP, Brower, C, Gilbert, M, Grenfell, BT, Levin, SA, Robinson, TP, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. PNAS. (2015) 112:5649–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503141112,

10. Cabello, FC, Godfrey, HP, Tomova, A, Ivanova, L, Dölz, H, Millanao, A, et al. Antimicrobial use in aquaculture re-examined: its relevance to antimicrobial resistance and to animal and human health. Environ Microbiol. (2013) 15:1917–42. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12134,

11. Founou, LL, Founou, RC, and Essack, SY. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: a developing country-perspective. Front Microbiol. (2016) 7:1881. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01881,

12. Xiong, J-B, Nie, L, and Chen, J. Current understanding on the roles of gut microbiota in fish disease and immunity. Zool Res. (2018) 40:70–6. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.069,

13. Hai, N. The use of probiotics in aquaculture. J Appl Microbiol. (2015) 119:917–35. doi: 10.1111/jam.12886,

14. Zhang, Z-L, Li, J-J, Xing, S-W, Lu, Y-P, Zheng, P-H, Li, J-T, et al. A newly isolated strain of Bacillus subtilis W2Z exhibited probiotic effects on juvenile red claw crayfish, Cherax quadricarinatus. Aquaculture. (2024) 585:740700. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2024.740700

15. Wang, C, Li, F, Wang, D, Lu, S, Han, S, Gu, W, et al. Enhancing growth and intestinal health in triploid rainbow trout fed a low-fish-meal diet through supplementation with Clostridium butyricum. Fishes. (2024) 9:178. doi: 10.3390/fishes9050178

16. Zhang, DX, Kang, YH, Zhan, S, Zhao, ZL, Jin, SN, Chen, C, et al. Effect of Bacillus velezensis on Aeromonas veronii-induced intestinal mucosal barrier function damage and inflammation in crucian carp (Carassius auratus). Front Microbiol. (2019) 10:2663. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02663,

17. Tan, HY, Chen, S-W, and Hu, S-Y. Improvements in the growth performance, immunity, disease resistance, and gut microbiota by the probiotic Rummeliibacillus stabekisii in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immun. (2019) 92:265–75. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.06.027,

18. Sewaka, M, Trullas, C, Chotiko, A, Rodkhum, C, Chansue, N, Boonanuntanasarn, S, et al. Efficacy of synbiotic Jerusalem artichoke and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-supplemented diets on growth performance, serum biochemical parameters, intestinal morphology, immune parameters and protection against Aeromonas veronii in juvenile red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Fish Shellfish Immun. (2019) 86:260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.11.026,

19. Katagiri, H, Kitahara, K, Fukami, K, and Sugase, M. The characteristics of the lactic acid bacteria isolated from moto, yeast mashes for Saké manufacture. Bull Agr Chem Soc Japan. (1934) 10:156–7. doi: 10.1080/03758397.1934.10857096

20. Coda, R, Kianjam, M, Pontonio, E, Verni, M, Di Cagno, R, Katina, K, et al. Sourdough-type propagation of faba bean flour: dynamics of microbial consortia and biochemical implications. Int J Food Microbiol. (2017) 248:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.02.009,

21. Moroni, AV, Arendt, EK, and Dal Bello, F. Biodiversity of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in spontaneously-fermented buckwheat and teff sourdoughs. Food Microbiol. (2011) 28:497–502. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.10.016,

22. Chaillou, S, Daty, M, Baraige, F, Dudez, A-M, Anglade, P, Jones, R, et al. Intraspecies genomic diversity and natural population structure of the meat-borne lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus sakei. Appl Environ Microb. (2009) 75:970–80. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01721-08,

23. Chaillou, S, Chaulot-Talmon, A, Caekebeke, H, Cardinal, M, Christieans, S, Denis, C, et al. Origin and ecological selection of core and food-specific bacterial communities associated with meat and seafood spoilage. ISME J. (2015) 9:1105–18. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.202,

24. Møretrø, T, Aasen, I, Storrø, I, and Axelsson, L. Production of sakacin P by Lactobacillus sakei in a completely defined medium. J Appl Microbiol. (2000) 88:536–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00994.x,

25. Bolívar, A, Costa, JCCP, Posada-Izquierdo, GD, Bover-Cid, S, Zurera, G, and Pérez-Rodríguez, F. Quantifying the bioprotective effect of Lactobacillus sakei CTC494 against Listeria monocytogenes on vacuum packaged hot-smoked sea bream. Food Microbiol. (2021) 94:103649. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2020.103649

26. Gao, Y, Jia, S, Gao, Q, and Tan, Z. A novel bacteriocin with a broad inhibitory spectrum produced by Lactobacillus sake C2, isolated from traditional Chinese fermented cabbage. Food Control. (2010) 21:76–81. doi: 10.1016/J.FOODCONT.2009.04.003

27. Costa, JCCP, Bolívar, A, Valero, A, Carrasco, E, Zurera, G, and Pérez-Rodríguez, F. Evaluation of the effect of Lactobacillus sakei strain L115 on Listeria monocytogenes at different conditions of temperature by using predictive interaction models. Food Res Int. (2020) 131:108928. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108928,

28. Wang, L, Kong, X, and Jiang, Y. Recovery of high pressure processing (HPP) induced injured Escherichia coli O157: H7 inhibited by Lactobacillus sakei on vacuum-packed ground beef. Food Biosci. (2021) 41:100928. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2021.100928

29. Reyes-Becerril, M, Ascencio-Valle, F, Macias, ME, Maldonado, M, Rojas, M, and Esteban, MÁ. Effects of marine silages enriched with Lactobacillus sakei 5-4 on haemato-immunological and growth response in Pacific red snapper (Lutjanus peru) exposed to Aeromonas veronii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2012) 33:984–92. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.08.014

30. Reyes-Becerril, M, Angulo, C, Estrada, N, Murillo, Y, and Ascencio-Valle, F. Dietary administration of microalgae alone or supplemented with Lactobacillus sakei affects immune response and intestinal morphology of Pacific red snapper (Lutjanus peru). Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2014) 40:208–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.06.032,

31. Nácher-Vázquez, M, Iturria, I, Zarour, K, Mohedano, ML, Aznar, R, Pardo, MÁ, et al. Dextran production by Lactobacillus sakei MN1 coincides with reduced autoagglutination, biofilm formation and epithelial cell adhesion. Carbohydr Polym. (2017) 168:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.03.024,

32. Dong, Y, Yang, Y, Liu, J, Awan, F, Lu, C, and Liu, Y. Inhibition of Aeromonas hydrophila-induced intestinal inflammation and mucosal barrier function damage in crucian carp by oral administration of Lactococcus lactis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2018) 83:359–67. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.041

33. Yin, Z, He, B, Ying, Y, Zhang, S, Yang, P, Chen, Z, et al. Fast and label-free 3D virtual H&E histology via active phase modulation-assisted dynamic full-field OCT. npj. Imaging. (2025) 3:12. doi: 10.1038/s44303-025-00068-0

34. Wu, Y, Fan, H, Feng, Y, Yang, J, Cen, X, and Li, W. Unveiling the gut microbiota and metabolite profiles in guinea pigs with form deprivation myopia through 16S rRNA gene sequencing and untargeted metabolomics. Heliyon. (2024) 10:491. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30491,

35. Muley, VY. Host transcriptional responses to viral infections: RNA-Seq analysis with Rsubread, HISAT2, and STAR with public RNA-Seq data. Methods Mol Biol. (2025) 2927:23–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-4546-8_2,

36. An, J, Liu, Y, Wang, Y, Fan, R, Hu, X, Zhang, F, et al. The role of intestinal mucosal barrier in autoimmune disease: a potential target. Front Immunol. (2022) 13:871713. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.871713,

37. Kong, W, Huang, C, Tang, Y, Zhang, D, Wu, Z, and Chen, X. Effect of Bacillus subtilis on Aeromonas hydrophila-induced intestinal mucosal barrier function damage and inflammation in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Sci Rep. (2017) 7:1588. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01336-9,

38. Abdel-Raheem, SM, Khodier, SM, Almathen, F, Hanafy, A-ST, Abbas, SM, Al-Shami, SA, et al. Dissemination, virulence characteristic, antibiotic resistance determinants of emerging linezolid and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus spp. in fish and crustacean. Int J Food Microbiol. (2024) 418:110711. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2024.110711,

39. Limbu, SM, Chen, LQ, Zhang, ML, and Du, ZY. A global analysis on the systemic effects of antibiotics in cultured fish and their potential human health risk: a review. Rev Aquac. (2021) 13:1015–59. doi: 10.1111/raq.12511

40. Amenyogbe, E, Chen, G, Wang, Z, Huang, J, Huang, B, and Li, H. The exploitation of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in aquaculture: present study, limitations and future directions: a review. Aquac Int. (2020) 28:1017–41. doi: 10.1007/s10499-020-00509-0

41. Llewellyn, MS, Boutin, S, Hoseinifar, SH, and Derome, N. Teleost microbiomes: the state of the art in their characterization, manipulation and importance in aquaculture and fisheries. Front Microbiol. (2014) 5:207. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00207,

42. Li, J, Cen, J, Zhou, Q, Zheng, X, Wu, Z, Li, Z, et al. Dietary probiotic intervention strategies of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis co-cultured in Litopenaeus vannamei with low fishmeal diet: insights from immune enhancement, anti-Vibrio and ammonia nitrogen stress. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (2025) 164:110414. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2025.110414,

43. Xiao, Y, Zhao, J, Zhang, H, Zhai, Q, and Chen, W. Mining genome traits that determine the different gut colonization potential of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species. Microb Genom. (2021) 7:000581. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000581

44. Ngamkala, S, Satchasataporn, K, Setthawongsin, C, and Raksajit, W. Histopathological study and intestinal mucous cell responses against Aeromonas hydrophila in Nile tilapia administered with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Vet World. (2020) 13:967–74. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.967-974,

45. Plata, G, Srinivasan, K, Krishnamurthy, M, Herron, L, and Dixit, P. Designing host-associated microbiomes using the consumer/resource model. MSystems. (2025) 10:e01068–24. doi: 10.1101/2023.04.28.538625,

46. Li, K, Wei, X, and Yang, J. Cytokine networks that suppress fish cellular immunity. Dev Comp Immunol. (2023) 147:104769. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2023.104769,

47. Saikh, KU. MyD88 and beyond: a perspective on MyD88-targeted therapeutic approach for modulation of host immunity. Immunol Res. (2021) 69:117–28. doi: 10.1007/s12026-021-09188-2,

48. Feng, M, Cheng, J, Su, Y, Tong, J, Wen, X, Jin, T, et al. Lactobacillus agilis SNF7 presents excellent antibacteria and anti-inflammation properties in mouse diarrhea induced by Escherichia coli. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:13660. doi: 10.3390/ijms252413660,

49. Zhang, C, Pu, C, Li, S, Xu, R, Qi, Q, and Du, J. Lactobacillus delbrueckii ameliorates Aeromonas hydrophila-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and immunosuppression of Cyprinus carpio huanghe var NF-κB/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Comp Biochem Phys C. (2024) 285:110000. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2024.110000,

50. Shin, N-R, Whon, TW, and Bae, J-W. Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol. (2015) 33:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.011,

51. Winter, SE, and Bäumler, AJ. Dysbiosis in the inflamed intestine: chance favors the prepared microbe. Gut Microbes. (2014) 5:71–3. doi: 10.4161/gmic.27129,

52. Cain, AK, and Hamidian, M. Portrait of a killer: uncovering resistance mechanisms and global spread of Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Pathog. (2023) 19:e1011520. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011520,

53. Charalambous, A, Grivogiannis, E, Dieronitou, I, Michael, C, Rahme, L, and Apidianakis, Y. Proteobacteria and Firmicutes secreted factors exert distinct effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection under normoxia or mild hypoxia. Meta. (2022) 12:449. doi: 10.3390/metabo12050449,

54. Levy, R, and Borenstein, E. Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rules. PNAS. (2013) 110:12804–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300926110,

55. Macpherson, AJ, Yilmaz, B, Limenitakis, JP, and Ganal-Vonarburg, SC. IgA function in relation to the intestinal microbiota. Annu Rev Immunol. (2018) 36:359–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053238,

56. Takeuchi, O, and Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. (2010) 140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022

57. Ellis, A. Immunity to bacteria in fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. (1999) 9:291–308. doi: 10.1006/fsim.1998.0192

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, crucian carp, inflammation, Latilactobacillus sakei, transcriptom

Citation: Zhao Y, Li R, Zhu T, Hu H, An G, Ren Z, Cui J and Jiang J (2026) Latilactobacillus sakei strains protect crucian carp against Aeromonas hydrophila–induced intestinal injury in an oral challenge model. Front. Nutr. 13:1768111. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2026.1768111

Edited by:

Bowen Li, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yuge Jiang, Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, ChinaYuncong Xu, China Agricultural University, China

Copyright © 2026 Zhao, Li, Zhu, Hu, An, Ren, Cui and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinchi Jiang, amlhbmdqaW5jaGlAMTI2LmNvbQ==

Yan Zhao1,2

Yan Zhao1,2 Jinchi Jiang

Jinchi Jiang