- 1School of Telecommunications Engineering, Xidian University, Xi’an, China

- 2Luoyang Institute of Science and Technology Library, Luoyang, China

With the rapid development of 6G and the widespread adoption of cloud computing technologies, security issues in distributed cloud computing systems have become increasingly critical. Ensuring user anonymity, legitimate device access, communication security, and efficient authentication has emerged as an urgent challenge. To address these issues, this paper proposes an anonymous, secure, and efficient authentication scheme for 6G cloud computing. The scheme supports both user authentication and device access authentication by integrating Chebyshev chaotic mapping with a multi-factor authentication mechanism. It ensures secure verification of user identities and access devices and protects subsequent session keys. Furthermore, a Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) is deployed on the device side to leverage unique hardware features, providing strong identity recognition and resistance to physical attacks while improving system authentication efficiency. Performance evaluations demonstrate that the proposed scheme reduces computational overhead by an average of 30.45% and communication overhead by an average of 16.32% compared with the baseline scheme. These results confirm that the proposed scheme significantly enhances communication security between authorized users, legitimate devices, and cloud servers in 6G cloud computing environments. By combining chaotic mapping, multi-factor authentication, and PUF-based verification, the scheme achieves robust security, lightweight computation, and strong scalability suitable for next-generation distributed cloud systems.

1 Introduction

With commercialization of the fifth-generation (5G) mobile communication network, major global telecom operators and technology companies are now shifting their research and development focus to the sixth-generation (6G) network. 6G is envisioned not only as a faster, lower-latency and more widely covered communication platform, but also as a transformative infrastructure that enables the true interconnection of everything. This integration is expected to trigger profound societal transformation and technological innovation, laying the foundation for a new era of intelligent infrastructure.

In this transformative process, cloud computing—serving as a core supporting technology—will demonstrate greater capabilities and wider application scenarios in the 6G. Benefiting from 6G’s high data transmission rates, ultra-low latency, high reliability and edge-distributed architecture, cloud computing will overcome the limitations of traditional networks in bandwidth, delay and resource allocation. This will extend computing and service capabilities toward the network edge, enabling faster data processing, lower service response times and more intelligent decision-making [1].

In the realm of smart cities, the integration of cloud computing and 6G can support real-time acquisition and analysis of massive data from high-definition video surveillance, intelligent traffic control systems and public safety management, enabling intelligent scheduling of urban resources and rapid response to events. In the industrial internet, cloud platforms can monitor the operational status of factory equipment and production line data in real time, enabling predictive maintenance and significantly improving production efficiency and equipment utilization [2]. In autonomous driving scenarios, vehicles can maintain high-speed communication with the cloud via 6G networks, uploading sensor data for real-time cloud-based processing to enhance perception and decision-making capabilities. In telemedicine, doctors can use ultra-high-definition imaging and real-time interactive systems to guide surgeries or monitor the health of remote patients, greatly alleviating the imbalance of medical resource distribution. For immersive experiences such as Virtual Reality (VR)/Augmented Reality (AR) and holographic communication, complex graphics rendering and scene generation can be handled in the cloud and transmitted back to the user terminal via the 6G network, ensuring smooth and immersive user experiences [3].

However, as cloud computing continues to evolve, ensuring user privacy and data security within cloud environments has become an urgent issue. In 6G, the scale of user and device access is expected to reach unprecedented levels. Traditional authentication mechanisms may face significant challenges, including excessive latency and computational overhead, in handling such large-scale user access and device authentication. This is particularly true in cloud computing environments, where authentication processes may involve extensive data processing and transmission, placing greater demands on authentication efficiency [4–6]. Moreover, in traditional identity authentication mechanisms, users may need to disclose certain identity information during the authentication process, which poses risks of privacy leakage or exploitation by attackers. Therefore, there is a pressing need to design a cloud computing-based anonymous and secure authentication scheme that not only protects user privacy but also significantly enhances authentication efficiency.

1.1 Related work

At present, extensive research has been conducted both domestically and internationally in the fields of authentication and key agreement, resulting in the proposal of various protocol schemes aimed at ensuring the security of authentication processes and data communications [7–13].

Parai et al. [10] based on Gupta’s [9] research, proposed an identity-based three-party authentication key negotiation protocol for resource-constrained IoT devices. They tested and estimated the execution time of the protocol on a Raspberry Pi 4 device, covering security levels from 80 bits to 256 bits. However, since the protocol is based on bilinear pairings, it still has a high computational cost. In 2023, Mookherji et al. [11] proposed a semi-centralized architecture and a certification and key negotiation scheme for smart healthcare systems. In this scheme, the cloud server delegates user registration functionality to fog servers, and users can complete registration by sending requests to fog servers. This scheme claims to effectively address the threat of server single-point compromise. However, fog servers are typically deployed close to the device edge layer and are considered untrusted. Compared to centralized cloud servers, fog servers have higher key management costs and challenges. Qiu et al. [14] addressed the imbalance between practicality and security in three-factor authentication by proposing a lightweight mobile device authentication scheme using chaotic mapping. The scheme utilizes fuzzy verifiers and honeyword techniques to resist offline password guessing attacks. In 2021, Lin et al. [15] introduced an authentication protocol tailored for 5G healthcare IoT systems, enabling patients to access multiple remote medical services using paired credentials. However, due to the absence of timestamps and the use of a public authentication parameter, the scheme is susceptible to Denial of Service (DoS) attacks. Additionally, storing users’ private keys in plaintext on the smart card leaves it vulnerable to card theft attacks. To address identity verification in Wireless Body Area Networks (WBAN), Alzahrani et al. [16] introduced a lightweight protocol that facilitates session key generation between sensor and hub nodes. Nevertheless, it lacks comprehensive mutual authentication among access points, hubs, and sensors, limiting its practical deployment. Nyangaresi et al. [17] proposed a cheme to secure interactions between body sensor units and administrators in WBAN scenarios, achieving forward secrecy through session key generation. Yet, the protocol fails to preserve user anonymity when the gateway node acts as an insider adversary.

Xie et al. [18] designed a scheme for patient monitoring systems using elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and validated its security via formal analysis. However, it does not implement mutual authentication between sensor and relay nodes. Deebak et al. [19] designed a framework for cloud-assisted medical cyber-physical systems based on Chebyshev chaotic maps. A major weakness lies in the registration phase, where user credentials are transmitted in plaintext to the gateway, risking identity exposure. Tu et al. [20] also proposed EAKE-WCI, an anonymous authentication protocol for wearable healthcare devices in cloud environments. While the scheme ensures mutual authentication among users, devices, and servers, it lacks adequate password protection during login, making it vulnerable to guessing attacks. Edwards et al. [21] introduced a distributed authentication framework, incorporating physical tokens, biometrics, and cryptographic keys to validate user identity. Lee et al. [22] developed a three-factor authentication method tailored for sensor-based devices operating in IoT settings. Their approach utilizes Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) and honeypot mechanisms to mitigate threats such as ID/password guessing, brute-force, and eavesdropping attacks. Mirsaraei et al. [23] introduced another three-factor authentication protocol suitable for IoT applications, employing elliptic curve cryptography and smart cards for user registration and identity verification within private blockchain environments. This design is particularly effective for resource-constrained IoT devices. Ghose et al. [25] presented two-factor authentication protocol. Initial verification step is based on traditional credentials (username and password), while the second step leverages persistent associations between the user’s device and an auxiliary unit. Ahmad et al. [26] introduced BAuth-ZKP, a multi-factor authentication protocol designed for smart city. By utilizing blockchain smart contracts, the scheme enables secure user verification without revealing personal identity information. Braeken et al. [27] developed a two-way multi-factor authentication and key exchange mechanism aimed at facilitating secure access to remote sensor nodes. Their approach ensures real-time data retrieval and defends against semi-trusted intermediaries, while preserving user anonymity and untraceability, and mitigating risks from session-specific data leakage. In the healthcare sector, Miao et al. [28] proposed a three-factor authentication protocol for medical IoT systems, leveraging blockchain to manage identity-related data and applying Chebyshev chaotic maps to enhance login and authentication robustness. Zhang et al. [29] presented an ECC-based three-factor scheme involving credentials, passwords, and biometrics for secure interaction among administrators, gateways, and industrial IoT devices. This protocol supports identity revocation and online updates, adapting to dynamic industrial requirements. To enhance cloud network security, Bernard et al. [30] designed a mutual authentication protocol utilizing visual cryptography. The approach employs confidential mappings—specifically visual encryption and challenge-response pairs—along with credential-based verification to counteract weaknesses in traditional cryptographic algorithms. Despite its enhanced security features, the scheme incurs significant computational cost, which limits its efficiency on resource-limited platforms.

PUF is an emerging cryptographic primitive known for its strong resistance to duplication. Min et al. [32] designed an authentication approach that integrates PUF with a dynamic identity mechanism, effectively safeguarding device identities and enhancing privacy at the hardware level. In a subsequent work, Aman et al. [33] developed a PUF-based mutual authentication protocol, enabling secure communication between devices and servers, as well as among devices themselves, thereby expanding its applicability. Shah et al. [34] presented a PUF-enabled authentication mechanism that employs challenge–response pairs and incorporates the AES encryption algorithm to improve overall system security. Zhu et al. [35] introduced a PUF-driven authentication protocol specifically designed for RFID environments, addressing critical security concerns such as unclonability and traceability, while also supporting mutual authentication. In summary, current authentication schemes still have security vulnerabilities and incur high computational and communication costs [24–31].

1.2 Contributions

In this paper, we propose a cloud-based anonymous and secure authentication scheme. Our approach enables mutual authentication between users and access devices, allowing them to securely establish a reliable shared session key. Communication efficiency is also considered in the proposed scheme. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

The security of the proposed scheme is proven under the Random Oracle Model. Additionally, security analysis demonstrates that the proposed scheme can withstand common attacks. Performance comparisons show that the proposed scheme addresses the security shortcomings of existing solutions and has lower computational and communication overhead.

1. This paper proposes an anonymous, secure, and efficient authentication scheme for cloud-based in 6G. The proposed scheme employs Chebyshev chaotic mapping and PUF to construct a lightweight key agreement mechanism. Additionally, by integrating hash functions and a session key update strategy, the scheme ensures user anonymity and forward security of session data. PUF technology is incorporated on the device side, leveraging its unique hardware characteristics to provide robust identity verification and resistance to physical attacks.

2. The security of the proposed scheme is formally proven under the random oracle model. Furthermore, the security analysis demonstrates that the scheme is resilient against common types of attacks. Performance comparisons indicate that the proposed solution addresses the security weaknesses of existing schemes while maintaining low computation and communication overhead.

1.3 Paper organization

The structure of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 outlines the foundational concepts relevant to the proposed scheme. Section 3 details the authentication protocol in depth. Sections 4 and 5 are dedicated to the security assessment and efficiency analysis of the scheme. The final section concludes the study and highlights potential avenues for future exploration.

2 Preliminaries

This section presents the relevant background of proposed scheme, with detailed explanations provided below.

2.1 System architecture

As shown in Figure 1, cloud-based authentication protocol proposed in this paper consists of three main components: cloud servers, users, and access devices. These components are interconnected via a high-speed, highly reliable 6G core network, forming a secure communication architecture that supports large-scale heterogeneous device access.

Cloud Servers: Serving as the central management entities, cloud servers are responsible for identity authentication, key management, secure storage, and data processing.

Users: It refers to individuals or organizations utilizing the system services, including system administrators, household users, and industrial control personnel. Users initiate authentication requests via terminals to access cloud resources or remotely control access devices.

Access Devices: These are intelligent terminal devices deployed in various application environments, equipped with communication, control, and response capabilities. Beyond simply connecting to the cloud platform, they can execute task instructions, report status information, and trigger predefined actions. Depending on the application scenario, access devices include the following:

• Industrial control terminals, actuators, and robots in factory settings, enabling automated operations and status feedback;

• Smart cameras, locks, and lighting systems in home environments, allowing remote control and environmental regulation;

• Embedded intelligent devices in fields such as healthcare, transportation, and energy, capable of edge-level sensing, state synchronization, and policy-based responses.

Access devices engage in mutual authentication with both users and cloud servers via the proposed protocol, ensuring that all communications occur in a trusted and secure environment, thereby preventing unauthorized access and data leakage.

Leveraging the high bandwidth and low latency characteristics of 6G core network, proposed system achieves strong security guarantees while meeting real-time performance requirements and supporting massive connectivity.

2.2 Chebyshev chaotic mapping

Given an integer

From Equation 1, the recursive formula for Chebyshev polynomials is derived as Equation 2 [36–38]:

According to the above formulas, Chebyshev polynomials satisfy the semi-group property. That is, for any two positive integers

The semigroup property [43]: For

where

Chebyshev Polynomial-Based Diffie-Hellman Problem (

2.3 Physical unclonable function

Physical Unclonable Function (PUF) is cryptographic primitives embedded as circuit modules within chips, serving as hardware security mechanisms. They exploit random physical variations introduced during manufacturing, which are uncontrollable and unique to each device. This inherent randomness ensures that producing two identical PUF-enabled devices is practically impossible. Consequently, PUF is increasingly utilized in information security, particularly for lightweight device authentication and as novel factors in multi-factor authentication protocols.

PUF operates using a challenge-response mechanism: input signals, termed challenges, are processed by the PUF to generate unique responses, collectively forming Challenge-Response Pairs (CRPs). In a typical authentication setup, the PUF circuit is embedded within the authentication server. During registration, the server receives challenges from authenticating devices, processes them via its PUF module, and generates corresponding responses, which can be stored as CRPs in a database for future verification. Due to the uniqueness and tamper-resistance of PUF, these responses remain consistent and unforgeable. An ideal PUF satisfies three critical properties:

1. Uniqueness: Identical challenges input to the same PUF always yield identical responses, while different PUFs produce different responses even when presented with identical challenges.

2. One-wayness: Given a known response, it is computationally infeasible to derive the original challenge that produced it.

3. Tamper-resistance: Physical attacks damage the PUF’s physical structure, thereby disrupting its challenge-response behavior and rendering its authentication function unusable.

These characteristics make PUF particularly suitable for secure, hardware-level identity verification in resource-constrained environments.

3 Proposed scheme

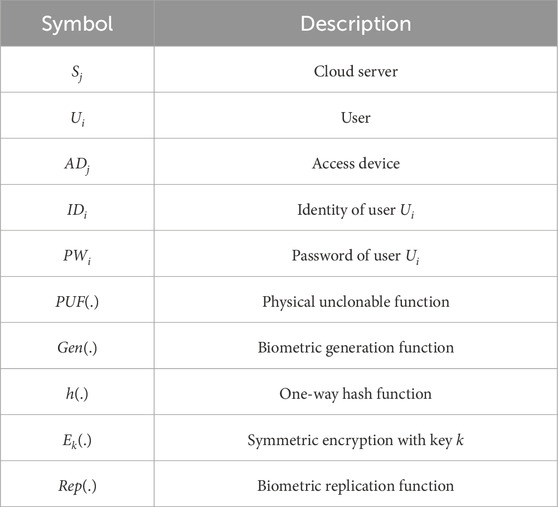

This section provides a comprehensive explanation of the proposed scheme, which is built upon an enhanced Chebyshev chaotic map. Table 1 outlines the symbols and cryptographic operations utilized throughout the scheme.

3.1 System initialization

Cloud server

3.2 Registration

3.2.1 Access device registration

Step 1: Access device

Step 2: Upon receiving

Step 3: The access device

3.2.2 User registration

Step 1:

Step 2: When

Step 3: Upon receiving SC,

3.3 Login and authentication

At this phase, user and the access device complete authentication and key agreement through the cloud server. The process is illustrated in Figure 3.

Step 1: The user

Step 2:

Step 3: Access device

Step 4: Upon receiving

Step 5: Upon receiving the message, the user computes

Step 6: Upon receiving the message,

4 Security analysis

In this section, we conduct a security analysis of the proposed scheme under the Random Oracle Model (ROM). Furthermore, additional security properties are examined through semantic evaluation [45–47].

4.1 Formal security proof using ROM

The security of session keys can be formally proven through rigorous mathematical analysis of the protocol within the Random Oracle Model (ROM).

Participants: Entities involved in the scheme include the user

Accepted: Instance

Partnering: Instances

1. Both instances must be in the accepted state.

2.

3.

Freshness: Instances

It is assumed that adversary

Semantic Security:

where

Proof: Five distinct games

Game

Game

In this game, within the random oracle model, adversary

Game

Building upon the previous game,

Game

Building upon Game

1.

2.

3.

In addition, due to the use of fuzzy extractors, false positives may occur. The probability that adversary

Therefore, we obtain the following result:

Game

In Game

In Game

According to Equations 6–12, we obtain:

4.2 Semantic analysis

In this section, we discuss the main safety features. We have conducted a comprehensive analysis of the plan to demonstrate that the proposed approach can achieve these safety features [48].

1. User Anonymity: During the registration phase, message is transmitted over a secure channel. Therefore, if an attacker attempts to launch an illegal attack, their only option is to perform cryptanalysis using the information intercepted from the user’s smart card (SC) and non-secure channel. Suppose the attacker has stolen the user’s smart card SC and conducted a power analysis attack to extract the parameters stored in the card. Even so, the SC does not contain the user’s identity information. Any attempt to recover the identity would inevitably encounter the difficulty of inverting the hash function. Moreover, even if the attacker intercepts communication over the non-secure channel, the use of anonymous identities by the user prevents the attacker from obtaining the user’s real identity.

2. Replay Attack: Replay attack refers to the scenario where an attacker intercepts a message that has previously been authenticated by

3. User Impersonation Attack: Whether it is an unregistered illegal user or a malicious legitimate user, in order to impersonate a legitimate user

4. Session Key Security: Based on the proposed scheme, after mutual authentication and key exchange between the user and the device, a session key for subsequent communication can be negotiated. The session key is given by

5. Perfect Forward Security: The session key between the user and the device node is denoted as

6. Man-in-the-middle attacks: Assume that

7. Insider Privilege Attack: Insider Privilege Attack refers to a situation where a legitimate system administrator turns into a malicious attacker and exploits their legitimate privileges to access confidential system information. As a result, insider privilege attacks often pose a greater threat than external attacks. In this protocol, once

8. Mutual Authentication: In this protocol, mutual authentication is achieved between the user

9. Device Node Forgery Attack: Suppose attacker

5 Performance analysis

In this subsection, we compare the proposed scheme with other existing scheme.

5.1 Function

In this subsection, the proposed scheme is compared with other existing protocols. The proposed scheme can effectively resist various types of attacks and largely meets the relevant security and functional requirements. In the table, a check mark (√) indicates that the protocol satisfies the corresponding security or functional requirement, while a cross mark (×) indicates that it does not. F1–F10 represent abbreviations for different attack types and functional features, with corresponding explanations provided below Table 2.

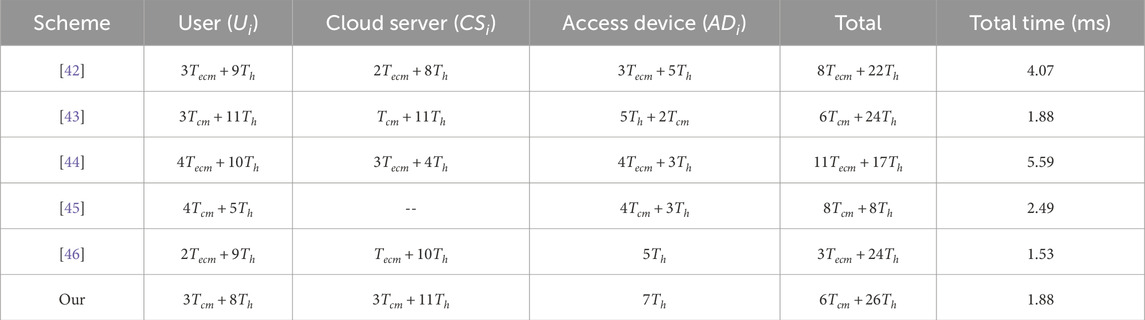

5.2 Computation overhead

This subsection presents a comparison of the computational overhead of the proposed schemes. The comparison is based on the computational efforts required by the protocol entities during the authentication and key agreement processes. The computation times are uniformly defined as follows: hash function, elliptic curve scalar multiplication, and chaotic map computation cost are denoted as

As shown in Table 3 and Figure 4, the proposed scheme exhibits significant advantages in multiple aspects. In terms of total computational cost, the Our scheme has a total of

Regarding total execution time, the Our scheme achieves a time of 1.88030, which is only slightly higher than that of [46] (1.53252) and [43] (1.87992), but significantly better than other schemes such as [42] (4.07076) and [44] (5.59188). This demonstrates that the Our scheme performs excellently in terms of efficiency and can meet high-performance requirements.

Furthermore, in terms of task distribution, the Our scheme maintains a balanced computational load among the user, cloud server, and access device. Specifically, the user side is responsible for

In summary, our scheme demonstrates strong overall advantages in computational efficiency, execution time, and load distribution, making it well-suited for practical deployment and widespread application.

5.3 Communication overhead

Table 4 and Figure 5 present a comparison of the communication overhead between the proposed protocol and five related protocols. For the sake of a fair comparison, the lengths of various parameters are uniformly set as follows: 160 bits for the Chebyshev polynomial, 320 bits for points on the elliptic curve, 160 bits for hash values, 128 bits for random nonces, 32 bits for the identities of the user and the access device node, 32 bits for timestamps, and 128 bits for blocks used in symmetric encryption and decryption. In addition, the communication process in the proposed protocol involves several potential components, including the user terminal, the PUF module embedded in the device, the encryption/decryption unit, the secure communication channel (e.g., TLS/SSL), and the core cloud server with its key management and auditing modules. These components together ensure the reliability, confidentiality, and integrity of message exchanges, forming the foundation for a fair and meaningful comparison of communication overhead.

As shown in Table 4, the proposed scheme demonstrates a significant advantage in terms of communication cost, achieving a total of 2,144 bits, which is relatively low compared to all the referenced schemes.

Specifically, compared to the highest communication cost in [43] (3,232 bits), the proposed scheme reduces the overhead by approximately 33.7%. It also achieves reductions of about 24.7% compared to [42] (2,848 bits), 21.2% compared to [44] (2,720 bits), and 23.9% compared to [46] (2,816 bits). Although [45] has the lowest communication cost (1,760 bits), it likely involves trade-offs in terms of computational complexity, security mechanisms, or functional completeness; otherwise, it would not be outperformed by more efficient schemes.

Overall, the proposed scheme effectively reduces communication overhead while maintaining system security and functional integrity. It achieves a communication cost optimization of approximately 20%–35% compared to most existing schemes, making it well-suited for bandwidth- and energy-constrained environments such as the Internet of Things and edge computing.

6 Conclusion

This paper presents an anonymous and secure authentication scheme for 6G cloud environments by combining Chebyshev chaotic mapping with the PUF mechanism. The scheme achieves secure identity verification, session key confidentiality, and resistance to common network attacks, while experiments demonstrate significant improvements in authentication efficiency and reductions in computational and communication overhead. Limitations remain regarding large-scale scalability, cross-vendor PUF compatibility, and sensitivity of chaotic parameters, which open meaningful directions for future research. Overall, the scheme offers a promising security solution for high-concurrency 6G cloud systems and provides a foundation for further exploration.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SY: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ZJ: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Chen J, Li T, Zhang Y, You T, Lu Y, Tiwari P, et al. Global-and-local attention-based reinforcement learning for cooperative behaviour control of multiple UAVs. IEEE Trans Vehicular Technol (2023) 73(3):4194–206. doi:10.1109/tvt.2023.3327571

2. Miao J, Ning X, Hong S, Wang L, Liu B. Secure and efficient authentication protocol for supply chain systems in artificial intelligence-based internet of things. IEEE Internet Things J (2025) 12:39532–42. doi:10.1109/jiot.2025.3592401

3. Bai Z, Miao H, Miao J, Xiao N, Sun X. Artificial intelligence-driven cybersecurity applications and challenges. Innovative Appl AI (2025) 2(2):26–33. doi:10.70695/AA1202502A09

4. Farhoudi M, Shokrnezhad M, Taleb T, Li R, Song J. Discovery of 6G services and resources in edge-cloud-continuum. IEEE Netw (2024) 39:223–32. doi:10.1109/mnet.2024.3438096

5. Chen J, Shu Q, Lu Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y. QCTF: a quantized communication and transferable fusion framework for multi-agent collaborative perception. IEEE Trans Intell Transportation Syst (2025) 26:15013–27. doi:10.1109/TITS.2025.3574725

6. Razaque A, Khan M, Yoo J, Alotaibi A, Alshammari M, Almiani M. Blockchain-enabled heterogeneous 6G supported secure vehicular management system over cloud edge computing. Internet Things (2024) 25:101115. doi:10.1016/j.iot.2024.101115

7. Xiao Y, Gao S. 5GAKA-LCCO: a secure 5G authentication and key agreement protocol with less communication and computation overhead. Information (2022) 13(5):257. doi:10.3390/info13050257

8. Chen J, Ren C, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Li Q, et al. Dual-centralized Q-Network-Based reinforcement learning for cooperative path planning of multiple UAVs. IEEE Trans Intell Transportation Syst (2025) 26:13232–46. doi:10.1109/TITS.2025.3587392

9. Gupta DS, Parai K, Obaidat MS. Efficient and secure design of id-3paka protocol using ECC[C]//2021 international conference on computer, information and telecommunication systems (CITS). IEEE (2021). p. 1–5.

10. Parai K, Gupta DS, Islam SKH. IoT-ID3PAKA: efficient and robust ID-3PAKA protocol for resource-constrained IoT devices. IEEE Internet Things J (2023) 11:10304–13. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3325583

11. Mookherji S, Odelu V, Prasath R, Das AK, Park Y. Fog-based single sign-on authentication protocol for electronic healthcare applications. IEEE Internet Things J (2023) 10:10983–96. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3242903

12. Xiong L, Wang JK, Yu L, Xiong N, Wu H. An efficient privacy-preserving access control scheme for cloud computing services. IEEE Trans Consumer Electron (2025) 71:6642–58. doi:10.1109/tce.2025.3534833

13. Soni P, Pradhan J, Pal AK, Islam SH. Cybersecurity attack-resilience authentication mechanism for intelligent healthcare system. IEEE Trans Ind Inform (2022) 19(1):830–40. doi:10.1109/tii.2022.3179429

14. Qiu S, Wang D, Xu G, Kumari S. Practical and provably secure three-factor authentication protocol based on extended chaotic-maps for Mobile lightweight devices. IEEE Trans Dependable Secure Comput (2020) 19(2):1–1351. doi:10.1109/tdsc.2020.3022797

15. Lin TW, Hsu CL, Le TV, Lu CF, Huang BY. A Smartcard-Based user-controlled single sign-on for privacy preservation in 5G-IoT telemedicine systems. Sensors (2021) 21(8):2880. doi:10.3390/s21082880

16. Alzahrani BA, Irshad A, Albeshri A, Alsubhi K. A provably secure and lightweight patient-healthcare authentication protocol in wireless body area networks. Wireless Personal Commun (2021) 117(1):47–69. doi:10.1007/s11277-020-07237-x

17. Nyangaresi VO. Provably secure pseudonyms based authentication protocol for wearable ubiquitous computing Environment[C]//2022 international conference on inventive computation technologies (ICICT). IEEE (2022). p. 1–6.

18. Xie Q, Liu D, Ding Z, Tan X, Han L. Provably secure and lightweight patient monitoring protocol for wireless body area network in IoHT. J Healthc Eng (2023) 2023(1):4845850. doi:10.1155/2023/4845850

19. Deebak BD, Hwang SO. A cloud-assisted medical cyber-physical system using a privacy-preserving key agreement framework and a chebyshev chaotic map. IEEE Syst J (2023) 17(4):5543–54. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2023.3303460

20. Tu S, Badshah A, Alasmary H. EAKE-WC: efficient and anonymous AuthenticatedKey exchange scheme for wearable computing. IEEE Trans Mobile Computing (2023) 1:1–12. doi:10.1109/TMC.2023.3297854

21. Edwards J, Aparicio-Navarro FJ, Maglaras L. FFDA: a novel four-factor distributed authentication Mechanism[C]//2022 IEEE international conference on cyber security and resilience (CSR). Rhodes, Greece: IEEE (2022). p. 376–81.

22. Lee J, Oh J, Kwon D, Kim M, Yu S, Jho NS, et al. PUFTAP-IoT: PUF-based three-factor authentication protocol in IoT environment focused on sensing devices. Sensors (2022) 22(18):7075. doi:10.3390/s22187075

23. Ghafouri Mirsaraei A, Barati A, Barati H. A secure three-factor authentication scheme for IoT environments. J Parallel Distributed Comput (2022) 169:87–105. doi:10.1016/j.jpdc.2022.06.011

24. Zhang L, Zhu Y, Ren W, Zhang Y, Choo KKR. Privacy-preserving fast three-factor authentication and key agreement for IoT-Based E-Health systems. IEEE Trans Serv Comput (2023) 16(2):1324–33. doi:10.1109/tsc.2022.3149940

25. Ghose N, Gupta K, Lazos L. ZITA: zero-interaction two-factor authentication using contact traces and In-band proximity verification. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing (2023). p. 1–16.

26. Ahmad MO, Tripathi G, Siddiqui F, Alam MA, Ahad MA, Akhtar MM, et al. BAuth-ZKP—a blockchain-based multi-factor authentication mechanism for securing smart cities. Sensors (2023) 23(5):2757. doi:10.3390/s23052757

27. Braeken A. Highly efficient bidirectional multifactor authentication and key agreement for real-time access to sensor data. IEEE Internet Things J (2023) 10(23):21089–99. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3284501

28. Miao J, Wang Z, Wu Z, Ning X, Tiwari P. A blockchain-enabled privacy-preserving authentication management protocol for internet of medical things. Expert Syst Appl (2024) 237:121329. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121329

29. Zhang Z, Huang W, Huang Y, Liao Y, Zhou S. A domain isolated tripartite authenticated key agreement protocol with dynamic revocation and online public identity updating for IIoT. IEEE Internet Things J (2024) 11:15616–32. doi:10.1109/jiot.2023.3349005

30. Bernard EB, Chen C, Shirui W, Guo H, Liu J. A secure mutual authentication protocol based on visual cryptography technique for IoT-Cloud. Chin J Electron (2024) 33(1):43–57. doi:10.23919/cje.2022.00.339

31. Pappu R, Ravikanth B, Recht J, Gershenfeld N. Physical one-way functions. Science (2002) 297(5589):2026–30. doi:10.1126/science.1074376

32. Min Z, Yao X, Hong L. Physical unclonable function based authentication protocol for unit IoT and ubiquitous IoT[C]//international conference on identification. IEEE Computer Society (2016). p. 179 184.

33. Aman MN, Chua KC, Sikdar B. Mutual authentication in IoT systems using physical unclonable functions. IEEE Internet Things J (2017) 4(5):1327–40. doi:10.1109/jiot.2017.2703088

34. Shah T, Venkatesan S. Authentication of IoT device and IoT server using secure vaults, 819 (2018). p. 824.

35. Zhu F, Li P, Xu H, Wang R. A lightweight RFID mutual authentication protocol with PUF. Sensors (2019) 19(13):2957–78. doi:10.3390/s19132957

36. Mo J, Hu Z, Shen W. A provably secure three-factor authentication protocol based on chebyshev chaotic mapping for wireless sensor network. IEEE Access (2022) 10:12137–52. doi:10.1109/access.2022.3146393

37. Truong TT, Tran MT, Duong AD. Improved Chebyshev polynomials-based authentication scheme in client-server environment. Security Commun Networks (2019) 2019(1):1–11. doi:10.1155/2019/4250743

38. He K, Ren Z. A new three-factor authentication scheme using Chebyshev chaotic map for peer-to-peer industrial internet of things. Computer Networks (2024) 247:110450. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110450

39. Kumar N, Ali R. Blockchain-enabled authentication framework for maritime transportation system empowered by 6G-IoT. Comput Networks (2024) 244:110353. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2024.110353

40. Yuan M, Tan H, Zheng W, Vijayakumar P, Alqahtani F, Tolba A. A robust ECC-based authentication and key agreement protocol for 6G-based smart home environments. IEEE Internet Things J (2024) 11(18):29615–27. doi:10.1109/jiot.2024.3392498

41. Kumar N, Ali R. A smart contract-based 6G-enabled authentication scheme for securing internet of nano medical things network. Ad Hoc Networks (2024) 163:103606. doi:10.1016/j.adhoc.2024.103606

42. Zhao X, Li D, Li H. Practical three-factor authentication protocol based on elliptic curve cryptography for industrial internet of things. Sensors (2022) 22(19):7510. doi:10.3390/s22197510

43. Irshad A, Chaudhry SA, Xie Q, Li X, Farash MS, Kumari S, et al. An enhanced and provably secure chaotic map-based authenticated key agreement in multi-server architecture. Arabian J Sci Eng (2018) 43:811–28. doi:10.1007/s13369-017-2764-z

44. Thakur G, Prajapat S, Kumar P, Chen CM. A privacy-preserving three-factor authentication system for IoT-enabled wireless sensor networks. J Syst Architecture (2024) 154:103245. doi:10.1016/j.sysarc.2024.103245

45. Li F, Yu X, Cui Y, Yu S, Sun Y, Wang Y, et al. An anonymous authentication and key agreement protocol in smart living. Comput Commun (2022) 186:110–20. doi:10.1016/j.comcom.2022.01.019

46. Abdi Nasib Far H, Bayat M, Kumar Das A, Fotouhi M, Pournaghi SM, Doostari MA. LAPTAS: lightweight anonymous privacy-preserving three-factor authentication scheme for WSN-based IIoT. Wireless Networks (2021) 27(2):1389–412. doi:10.1007/s11276-020-02523-9

47. Cui J, Yu J, Zhong H, Wei L, Liu L. Chaotic map-based authentication scheme using physical unclonable function for internet of autonomous vehicle. IEEE Trans Intell Transportation Syst (2022) 24(3):3167–81. doi:10.1109/tits.2022.3227949

Keywords: 6G, efficiency, authentication, anonymous, secure, cloud computing

Citation: Ying S and Jiang Z (2025) Efficient and secure authentication scheme with user anonymity based on cloud computing in 6G. Front. Phys. 13:1647836. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1647836

Received: 16 June 2025; Accepted: 28 October 2025;

Published: 26 November 2025.

Edited by:

Chengyi Xia, Tianjin Polytechnic University, ChinaReviewed by:

Devishree Naidu, Shri Ramdeobaba College of Engineering and Management, IndiaZhang Zhipeng, Tianjin Polytechnic University, China

Copyright © 2025 Ying and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Songpeng Ying, MjQwMTIxMDAwNDRAc3R1LnhpZGlhbi5lZHUuY24=

Songpeng Ying

Songpeng Ying Zhilin Jiang2

Zhilin Jiang2

![Bar chart showing computation overhead in milliseconds across six categories labeled as references [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], and](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1647836/fphy-13-1647836-HTML/image_m/fphy-13-1647836-g004.jpg)

![Bar chart comparing communication overhead in bits across six categories: [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], and](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1647836/fphy-13-1647836-HTML/image_m/fphy-13-1647836-g005.jpg)