- 1Aviation Meteorology Technology Research and Application Laboratory of SWATMB, Chengdu, China

- 2Chengdu University of Information Technology, Chengdu, China

In meteorological Cyber–Physical–Social Systems (CPSSs), physical sensors, communication networks, and social interactions naturally form a heterogeneous graph–nodes denote weather sensors or human agents, and edges represent both data links and social ties. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are expressly designed for learning on these graph structures, making them a natural choice for node classification in CPSSs. Nonetheless, their sensitivity to adversarial perturbations–where even minute disturbances can lead to catastrophic performance degradation–poses a critical challenge for secure and trustworthy meteorological monitoring. In this Research Topic, we introduce **Entropy Defense**, a defense mechanism tailored to meteorological CPSS scenarios. We first extend the Kullback–Leibler divergence–well established for measuring distribution similarity–to assess structural distribution consistency among sensor–social nodes. Building on this, we define two complementary metrics, **feature similarity** and **structural similarity**, and pioneer the addition of new edges between vulnerable nodes to restore legitimate information flows while pruning malicious connections during GNN message passing. To validate our approach, we apply Entropy Defense to three representative GNN architectures and evaluate on four diverse GNN datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that Entropy Defense outperforms three state-of-the-art adversarial defenses in both classification accuracy and stability, offering a lightweight, scalable solution for robust, secure meteorological monitoring in CPSSs.

1 Introduction

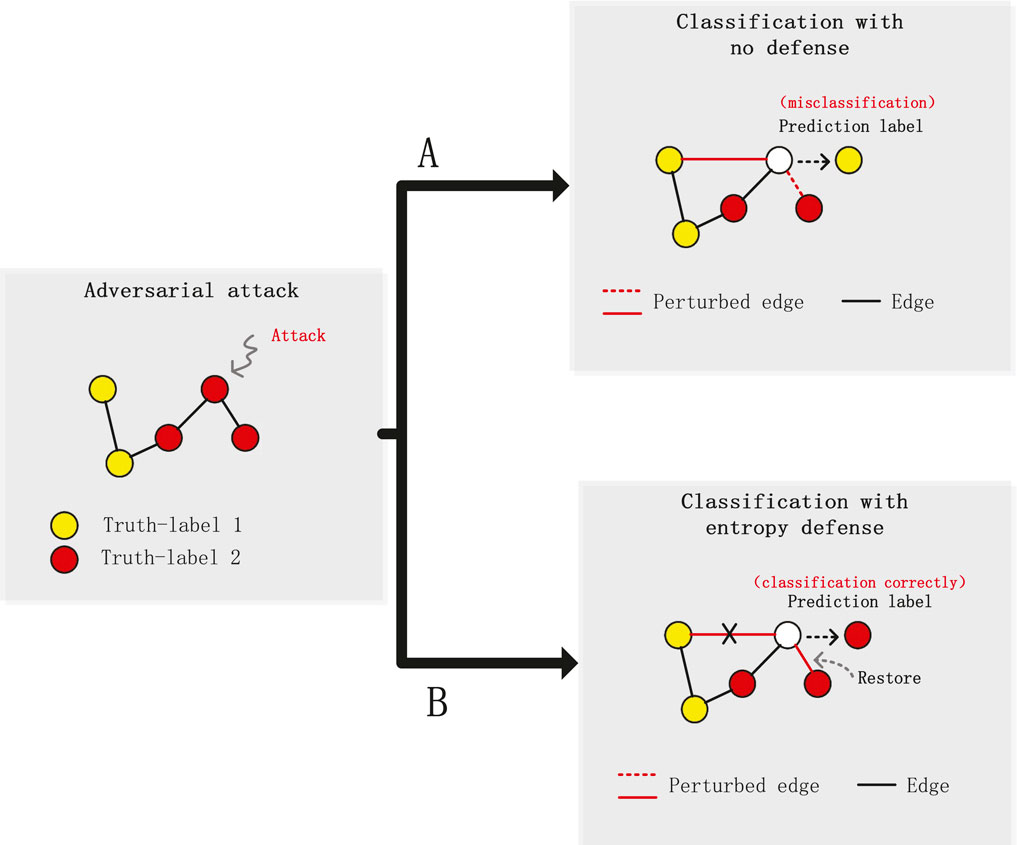

Deep learning has been widely applied in video coding tasks, for instance, Huang et al. [1], Wang et al. [2] and Wang et al. [3]. Similarly, graph deep learning and graph neural networks (GNNs) have achieved significant advances in social network analysis Li et al. [4]; Huang et al. [5]; Guo and Wang [6], biomedicine Shi et al. [7]; Li et al. [8]; Kazi et al. [9], and text categorization Deng et al. [10]; Yao et al. [11]; Zhao and Song [12]. In meteorological Cyber–Physical–Social Systems (CPSSs), interconnected weather sensors, communication networks, and social interactions naturally form heterogeneous graphs that underpin real-time weather monitoring and decision-making. As these networks become more widespread–particularly in critical CPSS domains like meteorological monitoring–effectively representing graphs to address downstream tasks is increasingly critical Wu et al. [13], Huang and Lu [14]. Like their counterpart in traditional neural networks, GNNs are vulnerable to adversarial attacks, a growing concern in the community. The effectiveness of Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNs) in tasks such as node classification is largely due to their feature extraction process, which aggregates node features in a weighted manner. This aggregation, while powerful, also exposes them to the risk of adversarial attacks through small, deliberate perturbations in the graph’s nodes or edges, i.e., adversarial attacks on graphs typically involve the introduction of carefully designed perturbations into the nodes and structures (i.e., edges) of the graph. In particular, graph neural networks are unique in that even if only a very small number of nodes or edges are perturbed, these perturbations can have a cascading effect across the entire graph, further exacerbating the challenge of adversarial attacks. The challenge is compounded by the difficulty in pinpointing which parts of the graph are affected by these attacks. The presence of these perturbations can have a widespread, cascading impact, making defense against such attacks a complex issue that is garnering much research interest. For instance, as depicted in Figure 1A, a graph’s structure perturbation can cause a node, correctly labeled as “2,” to be misclassified as “1” after an attack. Furthermore, Figure 1B demonstrates the impact of alternative perturbations on node classification.

Figure 1. (A) Small perturbations to the graph structure cause misclassification of graph nodes. (B) Graph nodes are classified successfully after using Entropy Defense.

Kullback-Leibler Divergence serves as a valuable metric for assessing the similarity between two probability distributions and has found widespread application as a classical loss function in various machine learning tasks, such as cluster analysis and parameter estimation. Its effectiveness is particularly evident in the realm of complex networks Zhang et al. [15]. Given its utility, it’s only natural to extend the use of Kullback-Leibler Divergence to the domain of graph data–especially sensor–social graphs in CPSS. However, solely relying on Kullback-Leibler Divergence, which primarily quantifies differences between distributions, falls short of our requirements. In this research, we introduce an enhanced iteration of GNN Guard Zhang and Zitnik [16], which we’ve dubbed “Entropy Defense.” Our innovative defensive mechanism is purpose-built to counter adversarial attacks on graph neural networks (GNNs) by curbing the spread of perturbed messages. We accomplish this by harnessing both node feature data and node structural information throughout the GNN’s messaging process. Moreover, our approach aims to faithfully restore the graph structure to its original, unperturbed state.

To assess the efficacy of Entropy Defense, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation on four diverse datasets, subjecting them to various attack scenarios, including direct targeted attacks, influence targeted attacks, and non-targeted attacks. We compared the performance of Entropy Defense against three contemporary state-of-the-art GNN defense methods. Our experimental results demonstrate that Entropy Defense surpasses existing approaches in terms of both defense performance and stability. This research not only provides a promising solution to enhance the resilience of GNNs against adversarial attacks but also underscores the significance of incorporating node feature and structure information in the defense strategy.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• We propose a new idea in graph adversarial defense: defending against adversarial attacks by connecting new edges (existing defenses usually defend against adversarial attacks by pruning suspicious edges or reducing the weights of suspicious edges). Our approach is very effective for nodes with strong edginess (i.e., few neighbors), as we will show in the experimental section.

• We improve the existing filter in GNN Guard Zhang and Zitnik [16] in graph adversarial defense messaging by using two evaluation metrics, node structure and node characteristics, for malicious message screening.

• We validate the effectiveness of our proposed Entropy Defense approach through extensive experiments. We compare it against three leading defense methods, apply it across three different graph neural network models and four datasets, and establish new benchmarks in node classification performance.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work, while Section 3 defines the problem and provides preliminary information. We detail our proposed method in Section 4 and present experimental results in Section 5. Finally, we conclude our paper and suggest avenues for future research in Section 6.

2 Related work

In this section, we discuss adversarial attacks and adversarial defenses of graphs that are closely related to this work.

2.1 Graph neural networks

Graph neural networks (GNNs) have experienced significant advances in recent years, especially when it comes to addressing machine learning problems with graph data. Two primary categories of GNN methods have come to prominence: spectral-based and spatial-based methods.

Spectral-based methods leverage graph spectral theory to learn node representations within a graph Bruna et al. [17], Defferrard et al. [18], Kipf and Welling [19]. The notion of applying the Fourier basis to graphsBruna et al. [17] was initially introduced to extend the convolution operation from traditional Euclidean data to graph-structured data, sparking a new perspective on graph convolution. Building on this, Defferrard et al. developed ChebNet, utilizing Chebyshev polynomials as the basis for convolutional filters. Following this, researchers like Kipf simplified this approach with the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN), which applies a first-order approximation to further ease the computation in spectral graph networks. Another significant development is the Simple Graph Convolution (SGC) Wu et al. [20], which streamlines graph convolution down to a linear model’s simplicity while still retaining robust performance.

The second category defines graph convolution through the aggregation and transformation of local neighborhood information in the spatial domain Gilmer et al. [21], Hamilton et al. [22], Velickovic et al. [23]. Take, for example, the Diffusion Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) Atwood and Towsley [24], which interprets graph convolution as the diffusion of information across the graph, assigning specific probabilities to the movement of information from one node to its neighbors. Another innovation is the Graph Attention Network (GAT) Velickovic et al. [23] introduced by Velickovic and colleagues. GAT differentiates itself by assigning varying attention weights to neighboring nodes, which refines the information aggregation process. These spatial methods are distinct in how they handle information transfer and aggregation, thereby broadening the arsenal of GNN tools for diverse applications.

2.2 Adversarial attacks on graphs

Adversarial attacks on graphs can be divided into two principal categories based on when they occur in the model’s lifecycle: poisoning attacks and evasion attacks. Poisoning attacks happen during the training phase, where attackers introduce harmful data into the training set, thereby corrupting the model’s learning process and its eventual performance. Evasion attacks, however, take place during the testing phase or in practical applications, where attackers manipulate nodes or edges to create adversarial examples, aiming to fool the model into misclassifying or failing to recognize these manipulated cases.

2.2.1 Poisoning attacks

A well-known study in poisoning attacks is nettack Zügner et al. [25], which uses a scoring function to assess the impact of graph perturbations on the target model’s performance. It employs a greedy algorithm to strategically alter the graph’s structure. This approach looks for locally optimal changes that can most disrupt the model’s learning. Another novel approach by Liu et al. [26] and colleagues introduced a label poisoning technique. This method capitalizes on the similarity between decoupled graph convolutional networks and label propagation, enabling significant performance degradation without needing graph structure details, relying solely on node features. Researchers like Zügner and Günnemann [27] have also implemented meta-learning to tackle the two-layer programming challenge posed by cyber-attacks, generating adversarial examples by subtle modifications in the graph that lead to incorrect model outputs.

2.2.2 Evasion attacks

Wang et al. [28] reformulates evasion attacks against GNNs as related to computing label influence on label propagation, and proposes an influence-based evasion attack against GNNs that does not require knowledge of the GNN model. Zhang et al. [29] uses mutual information to measure the long-term gain of each perturbation and proposes a method called projection ordering attack that reduces the adaptation cost of learning a new attack strategy. Dai et al. [30] deliberately select nodes to inject triggers and target class labels during the poisoning phase to perform an undetectable graph backdoor attack with a limited attack budget.

The variety of these methods, tailored to different attack models and stages, greatly contributes to the ongoing research into adversarial attacks on graph neural networks. This body of work not only deepens our understanding of such attacks but also offers robust tools to address security challenges inherent in machine learning models that process graph data.

2.3 Defense on graphs

While neural networks have revolutionized various fields Gilmer et al. [21], Velickovic et al. [23], Kipf and Welling [19], securing graph neural networks (GNNs) against adversarial attacks proves more complex than defending against attacks on images Goodfellow et al. [31] and text Jia and Liang [32], aNonetheless, there have been some inventive strides in this area. A technique known as GNN-Jaccard Wu et al. [33] applies a simple edge-weight initialization strategy to fend off adversarial attacks, yielding commendable results. Another method, GNN-SVD, Entezari et al. [34] sprotects against network assaults by rebuilding the graph with lower-order singular components, lessening the impact of higher-order adversarial perturbations. RobustGCN Zhu et al. [35] enhances the resilience of the network by incorporating Gaussian distributions into the nodes’ representations within each convolutional layer. This approach aids in fortifying the model against potential disruptions. Furthermore, GNN Guard Zhang and Zitnik [16] introduces a novel defensive mechanism. It assesses the links in node features during the message-passing phase, allowing it to detect inconsistencies and mitigate the attack’s effects strategically. Despite these advances, ensuring the adversarial robustness of GNNs remains a formidable challenge, with much room for improvement and innovation in the field.

3 Preliminaries

Before diving into the core discussions, let’s establish the notational groundwork that we’ll rely on throughout this paper. It’s important to note that all vectors will be assumed to be in column form unless mentioned otherwise. When referring to matrices,

3.1 Graph representation and node classification

We define

In the context of GNN’s node classification task, our objective is to devise a function

where

3.2 Kullback-Leibler divergence

In this work, we also focus on relative entropy (Kullback-Leibler divergence), a fundamental concept in probability and information theory, and an asymmetric measure of the difference between two probabilities. For two probabilities, P and Q, the relative entropy can be formulated as Equation 2:

Given two probability distributions, P and Q, the relative entropy is expressed as: Let P and Q be probability distributions, each with n components.

3.3 Entropy defense: problem formulation

Similar to GNN Guard Zhang and Zitnik [16], Entropy Defense offers a robust defensive strategy that can be seamlessly integrated into any Graph Neural Network (GNN) framework. This allows the creation of a novel GNN variant, hereafter denoted as such, designed to remain impervious to poisoning attacks. A standout feature of this approach is its ability to maintain accurate prediction capabilities even when trained on compromised graphs.

3.3.1 Problem (defense against poisoning attacks on graphs)

During a poisoning attack, adversaries manipulate the graph’s structure and node attributes (note: this work does not cover node insertion and deletion attacks). Such alterations can substantially impair the GNN’s functionality. Taking G′ to represent the graph G post-attack, our objective can be articulated as follows:

Where

In this study, we present a defensive strategy for semi-supervised node classification, focusing on safeguarding node prediction accuracy from adversarial attacks. While our aim is to minimize the total impact as outlined in Equation 3, direct optimization is unfeasible due to the unpredictability of graph G’s structure pre-attack. Our solution is an innovative message-passing technique: when an attack introduces a false edge, our method detects and halts message transmission for that edge, emphasizing genuine edges. Conversely, if a legitimate edge is removed, we strive to reinstate it, thereby approximating the graph’s original structure.

4 Entropy defense

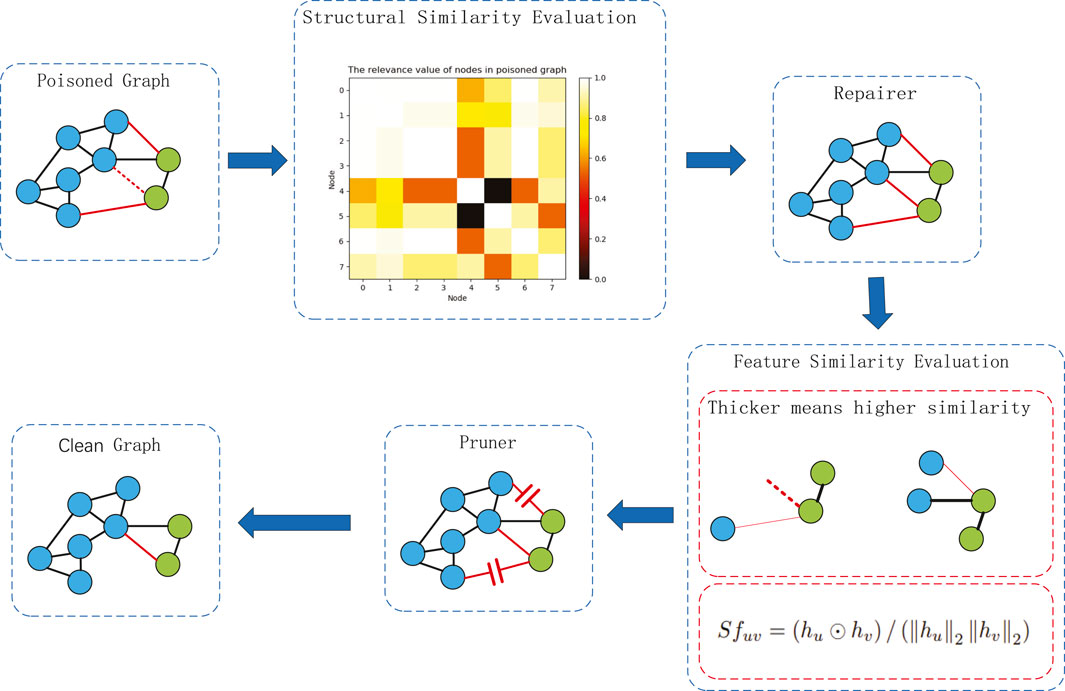

In this section, we unveil Entropy Defense, our proposed methodology to mitigate the effects of adversarial attacks on graph neural networks, specifically those that aim to poison the training data. Our defense mechanism is predicated on two key operations: “repairing” the graph structure by creating new edges based on nodes’ edginess and it’s structure and “pruning” the graph by removing edges that are likely to be malicious, based on node similarity and the importance of neighboring nodes.

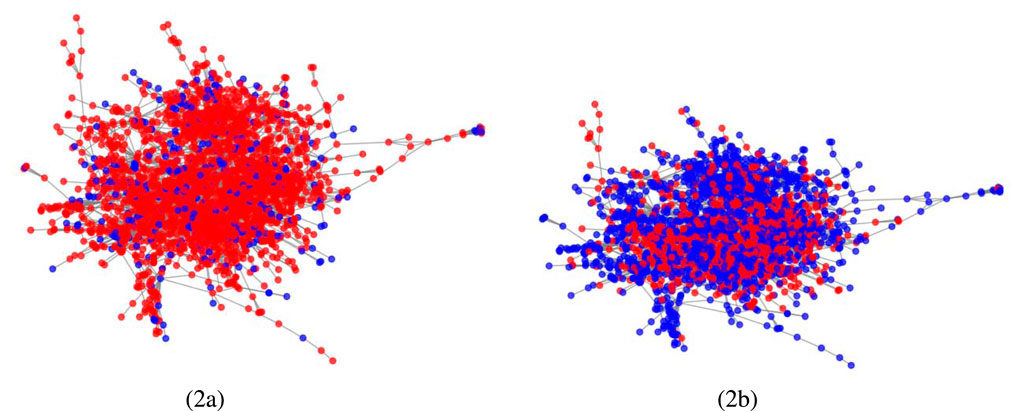

A body of research, exemplified by works such as Jin et al. Jin et al. [36], classifies malicious graph attacks into two primary strategies: the introduction of deceptive edges between nodes with differing features and labels, and the removal of authentic edges connecting nodes with similar features or identical labels. Guided by this understanding, Entropy Defense is rooted in two core principles: the identification and elimination of spurious edges during the message-passing phase, and the restoration of pruned genuine edges, with particular emphasis on nodes of low degree, which have been demonstrated to be particularly vulnerable to adversarial attacks Zügner et al. [25]. For a visual representation of the impact of our approach, please refer to Figure 2.

Figure 2. Node classification performance under attack (Red indicates misclassified nodes and blue indicates correctly classified nodes.). (a) No defense. (b) Entropy defense.

4.1 Similarity estimation

Distinct from Zhang and Zitnik [16] that gauges node similarity solely based on nodal characteristics, Entropy Defense assesses similarity utilizing both local structural attributes and node features. Our focus on local structure is grounded in the realization that after several rounds of message passing, the direct influence between distant nodes fades, making the concept of global structure less relevant for assessing the similarity between any two given nodes. This attenuation of influence is a form of information decay which supports the rationale for a local-structure-centric similarity metric. Therefore, we utilize the variability of local structural information to assess the structural similarity between node pairs. This is consistent with insights from studies on complex networks Zhang et al. [15], which we draw upon to inform our approach. Local structural attributes, which include metrics such as node degree or other graph-specific measures, provide a snapshot of a node’s immediate network neighborhood. By analyzing these local structural features, we can discern the similarity or dissimilarity between nodes, which is instrumental in identifying edges that may have been artificially introduced or wrongfully removed by an attacker. Our approach to similarity estimation is therefore two-fold: it combines node features with local structural properties to obtain a robust measure of similarity that can withstand the subtleties of adversarial graph manipulation. This enhanced measure allows us to more accurately prune malicious edges without inadvertently disrupting the graph’s inherent structure, thereby preserving the integrity and utility of the graph for downstream tasks such as node classification.

The initial step involves determining the local structure of each node, enabling the generation of the set of probability distributions for the node. Consider the networks of node

The probability set of node i denoted as Equation 5:

The elements in

When the total degree of node

Where

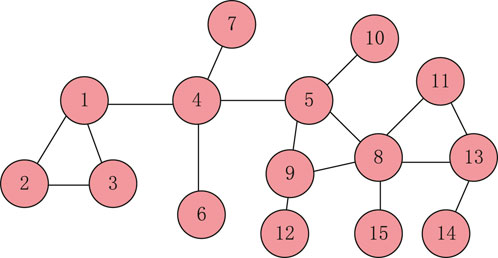

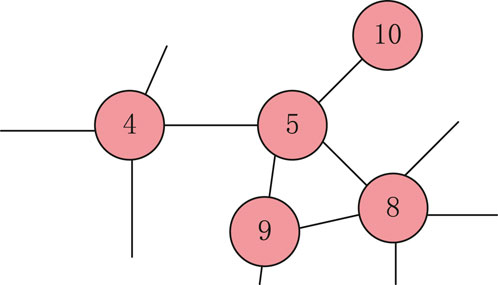

To better describe the method, we illustrate it with a simple network A, as shown in Figure 3, and a local network of node 5, as shown in Figure 4.

The node set

The degree set

Thus the total degree

Before calculating the relative entropy, we also need to preprocess the order of the elements in the probability set to ensure the accuracy of the similarity measure (in this work, we use descending order), and the processed probability set is shown in Equation 11:

In order to prevent zeros in the probability set from creating problems for the calculation of relative entropy and to avoid this problem, it is also necessary to change the definition of relative entropy as Equation 12:

Where

The relative entropy value of each pair of nodes indicates the difference in the local structure of each pair of nodes. Since the cross-entropy is asymmetric, in order to unify the relevance value of each pair of nodes, the correlation value

Thus, the relevance matrix

The elements of the node similarity matrix are defined as Equation 16:

Where

4.1.1 Quantify the feature similarity of each node

Unlike quantifying the structural similarity of nodes by considering the local structure of a node concerning all other nodes, when quantifying the feature similarity of nodes, we only consider the feature similarity of a node concerning its neighboring nodes. If

Where

4.2 Repairer & pruner strategy

Our approach’s precomputation was detailed in Section 4.1. This segment outlines our methodology for countering adversarial attacks through edge restoration and pruning. As illustrated in Figure 5, accessing a pristine graph is challenging, making the detection of perturbed nodes and the restoration of severed edges complex.

Nodes with a lower degree, as evidenced by Research Zügner et al. [25], are more susceptible to attacks, leading us to deduce that these nodes are primary targets.

Within our strategy, we evaluate attacked nodes based on their structural similarities to their immediate neighbors. Our initial step involves determining the accumulated structural similarity for each node to its adjacent counterparts, represented as Equation 18:

Here,

where

where

4.2.1 Pruner mechanism

A common poisoning attack strategy involves linking nodes exhibiting contrasting features or highly disparate local configurations. In this context, eliminating dubious edges emerges as a robust defensive mechanism against these perturbative edge insertions. When restoring edges, there’s a risk of linking nodes with analogous structures but differing features. To avert erroneous restorations, we opt for edge pruning. Preceding the pruning procedure, we standardize the feature similarity amongst the immediate neighboring nodes, symbolized by

Where

Finally, we prune the edges by updating the importance weight

It means only edges filtered twice by feature importance and structural importance are allowed to exist, and the GNN may ignore perturbed edges connecting different nodes.

4.3 Layer-Wise Graph Memory

In order to prevent edge pruning operations from destabilizing the GNN, we follow the Layer-Wise Graph Memory, which plays well in GNN Guard Zhang and Zitnik [16], to effectively achieve a robust estimation of important weights and smooth evolution of edge pruning. It is applied to each GNN layer, preserving part of the memory of the pruned graph structure of the previous layer, defined as Equation 25:

where

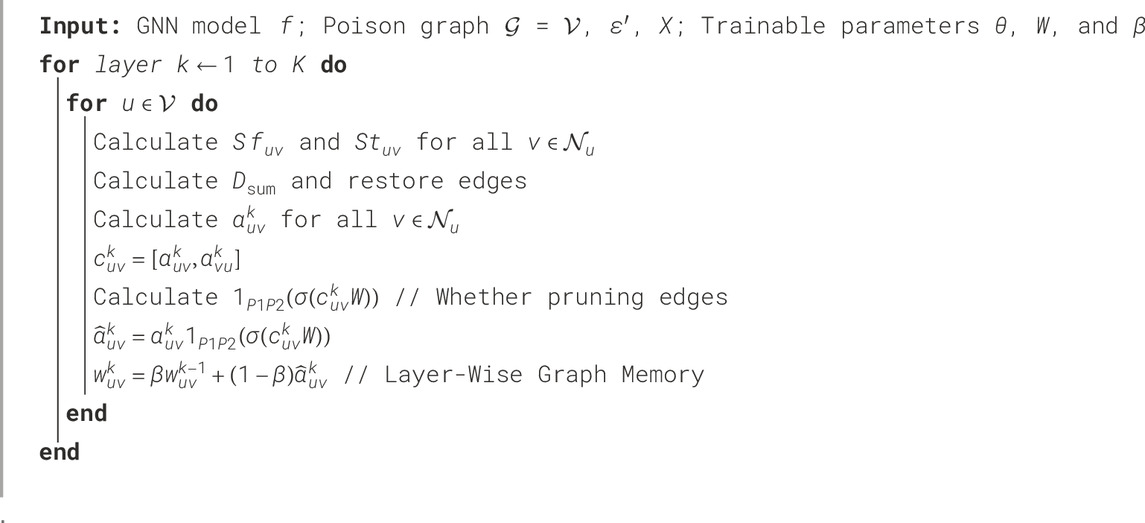

4.4 Overview of entropy defense

Algorithm 1 outlines the Entropy Defense strategy, which is designed to be a flexible defense mechanism that can be adopted within any graph neural network framework to fortify it against poisoning attacks. The underlying process of the algorithm is an iterative restoration of the graph structure during the GNN’s message-passing phase, coupled with the dynamic adjustment of defense coefficients that weigh the importance of edges based on structural and feature similarity.

The importance weight

In the broader context of adversarial defense for graphs, Entropy Defense offers a distinct approach when compared with other GNN defenders. For instance, GNN-Jaccard identifies potential threats by detecting suspicious edges during GNN preprocessing. In contrast, GNN-SVD relies solely on graph structures for its defensive mechanism. Notably, akin to GNNGuard, Entropy Defense dynamically adjusts the defense coefficients across each GNN layer. While GNNGuard exclusively employs node features to eliminate suspicious edges, Entropy Defense leverages both node features and the node’s local structure for this purpose. What sets our approach apart is the innovative strategy we introduce for thwarting adversarial attacks.

5 Experiments

We start by describing the experimental setup. We then compare the Entropy Defense with existing GNN defenders (Section 5.1) and design experiments to demonstrate the feasibility of our approach (Section 5.2). The experimental section details the validation of the Entropy Defense mechanism. The authors aim to showcase its effectiveness against various adversarial attacks compared to existing state-of-the-art defenses and to highlight the efficacy of their approach specifically in the context of low-degree nodes, which are deemed to be more vulnerable to attacks.

5.1 Datasets

The experiments are conducted on commonly used citation network datasets - Cora McCallum et al. [37], Citeseer Sen et al. [38], and an extended version of Cora (Cora ML)McCallum et al. [37] - as well as the ogbn-arxivHu et al. [39] dataset, providing a mix of undirected graphs with binary features and a directed graph with digital node characteristics.

5.2 Data availability

The dataset used in this study is provided by the authors of GNNGuard: Defending Graph Neural Networks against Adversarial Attacks and is publicly available on GitHub at the following link: https://github.com/mims-harvard/GNNGuard. The dataset is used in accordance with the original authors’ terms and conditions.

5.3 Baselines

To evaluate the effectiveness of Entropy Defense, we use the adversarial attack repository DeepRobust Li et al. [40] to compare it to state-of-the-art GNN and defense models, including GCN, GIN, JK-NET, GNN-Jaccard, GNN-SVD, and GNNGuard. These represent a diverse set of approaches for GNN architecture and adversarial defense strategies.

• GCN Kipf and Welling [19]: Although there are many different GNN variants, GCN remains the most representative of them all.

• GIN Xu et al. [41]: GIN generates node embeddings by aggregating neighborhood information using an isomorphism insensitive aggregator, and has gained attention in the field of graph representation learning due to its expressiveness and effectiveness in handling a wide range of graph-structured data. It is often used as a baseline to defend against adversarial attacks.

• JK-NET Xu et al. [42]: JK-NET enhance the expressiveness and performance of graph neural networks by combining and aggregating information from multiple “jumping” layers, showcasing its potential to enhance the expressiveness and effectiveness of graph representation learning.

• GNN-Jaccard Wu et al. [33]: GCN-Jaccard filters the edges of nodes whose Jaccard similarity of connected features is less than a threshold to preprocess the network. The method exploits the fact that attackers tend to connect nodes with different features or different labels.

• GNN-SVD Entezari et al. [34]: Since nettack is a high-rank attack, GNN-SVD reconstructs a low-rank approximation of the graph, significantly reducing the impact of adversarial attacks. While its initial goal is to defend against nettack, it can be directly extended to non-targeted and random attacks.

• GNNGuard Zhang and Zitnik [16]: GNNGuard is one of the most effective preprocessing methods available for defense against adversarial attacks (especially direct attacks). It is based on neighbor importance estimation to detect suspicious edges and mitigates the negative impact of predictions by removing or reducing their weight in neural messaging.

5.4 Setup

• Adversarial attacks. We compare the model to a baseline of three adversarial attacks: direct targeted attack Zügner et al. [25], influence targeted attack Zügner et al. [25], and non-targeted attack (Mettack Zügner and Günnemann [27]). In direct targeted attack, we set

• GNN models. We combine the Entropy Defense approach with three GNNs (GCN Kipf and Welling [19], JK-NET Xu et al. [42], GIN Xu et al. [41]) and show the defense performance of these models against adversarial attacks.

• Defense algorithms. We compare our approach with three existing state-of-the-art defense algorithms: GNN-SVD Entezari et al. [34], GNN-Jaccard Wu et al. [33], and GNNGuard Zhang and Zitnik [16].

We further investigate the feasibility of our approach for low-rank nodes in Section 5.2. We selected 30 correctly classified target nodes (10 nodes with the largest classification margin, 10 random nodes, and 10 nodes with the smallest margin) to compare with GNNGuard Zhang and Zitnik [16] under the GCN model and three different datasets (Cora, Citeseer, Cora_Ml).

5.5 Defense against targeted and non-targeted attacks

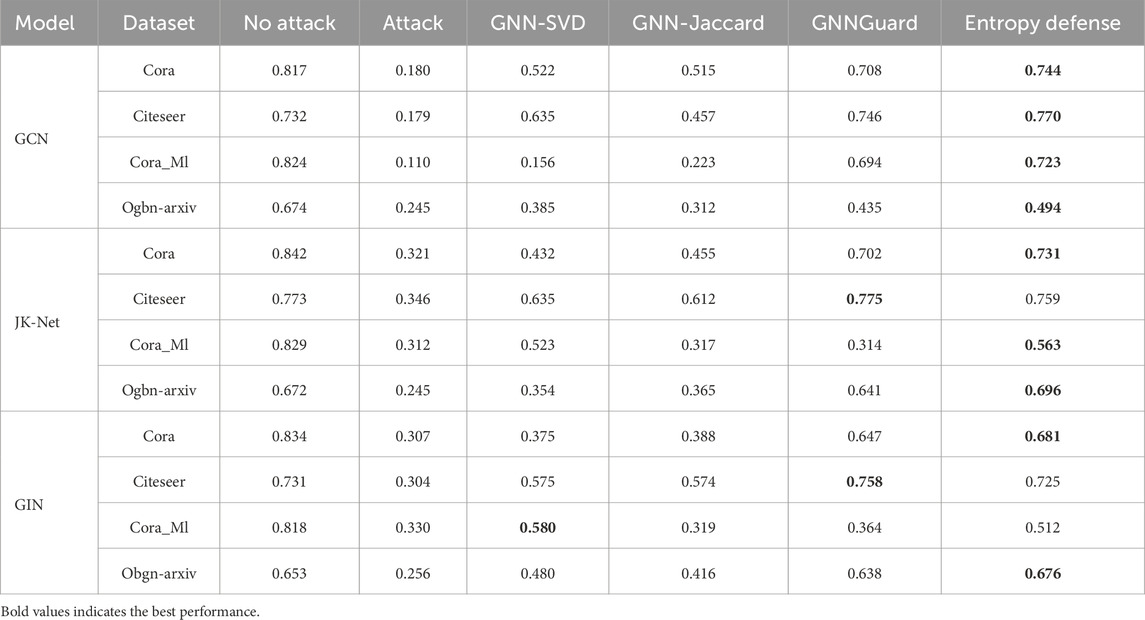

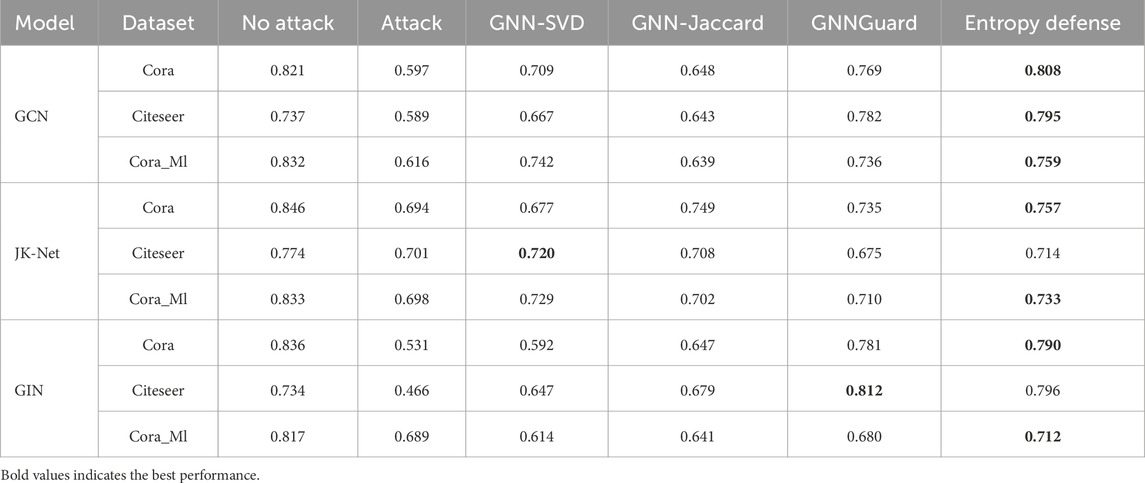

1. Direct targeted attack. We observe in Table 3 that the direct targeted attack is an extremely harmful attack that effectively degrades the performance of all GNN models. The results suggest that Entropy Defense outperforms other methods in most cases and significantly on the Cora ML datasetAs shown in the table our method outperforms other methods on the attacked target nodes in most cases. Especially on the Cora_Ml dataset, GNNGuard, which is currently the most effective method against direct targeted attacks, is actually not as effective. Although in some cases our method is not the most effective, it is clear that significant progress has been made.

2. Results for influence targeted attack. As shown in Table 2, Entropy Defense generally outperforms other baseline defense algorithms in terms of classification accuracy. And it is clear that the attack effect of the influence targeted attack is much smaller than that of the direct targeted attack (by looking at the “Attack” and “No-Attack” columns in Tables 2, 3), suggesting that part of the perturbation information is dispersed during the information transmission.

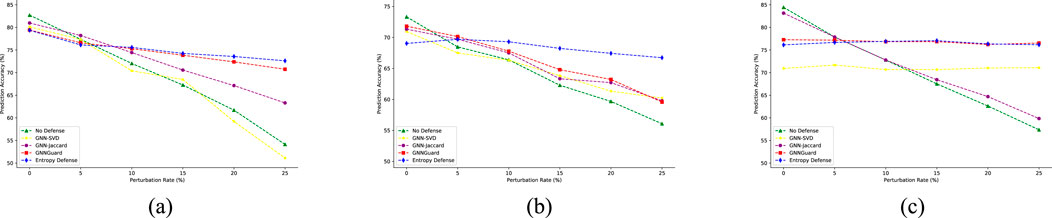

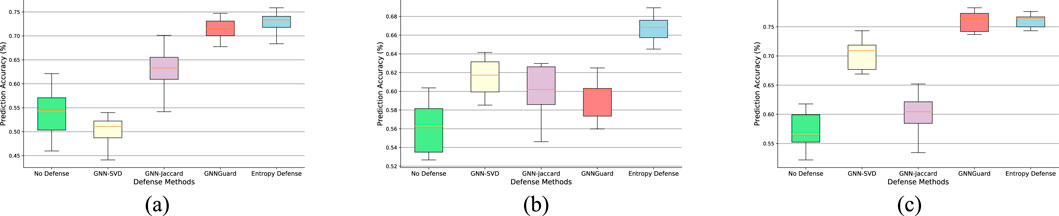

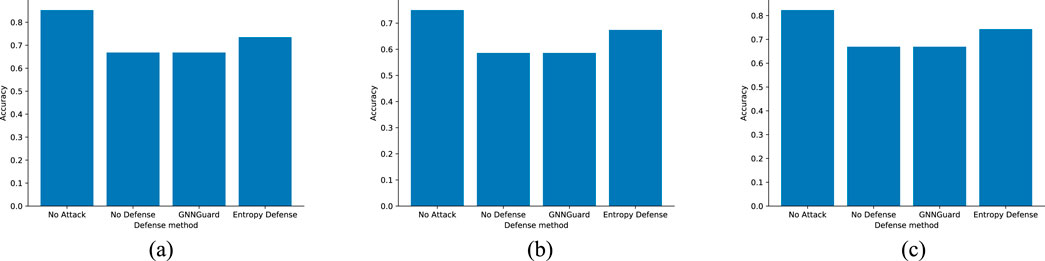

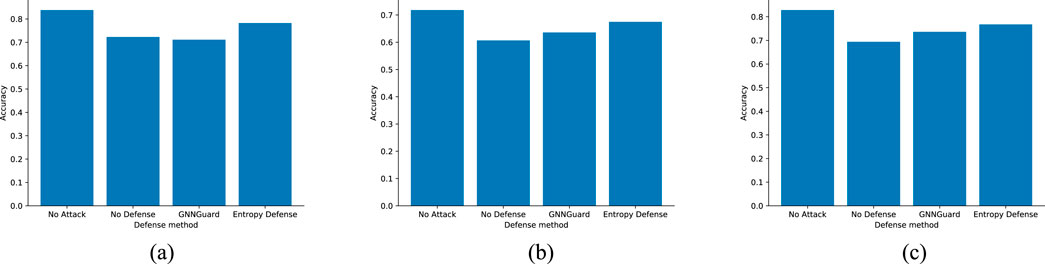

3. Results for non-targeted attack. As shown in Figure 6, our method clearly outperforms other methods. In particular, on the Citeseer dataset, our model improves the classification accuracy of GCN by more than 10% at a 25% perturbation rate, and we also improve it by at least 8% compared to the other baselines. GNN-Jaccard performs well at low perturbations, but GNN-Jaccard only preprocesses the perturbation map once, which is not able to cope with high perturbations. GCN-SVD is designed for targeted attacks and is not well adapted to non-targeted adversarial attacks. GNN-Guard is also a powerful defense method, however, it can be observed from Figures 6, 7 that our method is better than his in terms of both overall performance and stability.

Figure 6. Node classification performance under non-targeted attack (mettack). (a) Cora. (b) Citeseer. (c) Cora_Ml.

Figure 7. Node classification performance under 25% pertubation rate non-targeted attack (mettack). (a) Cora. (b) Citeseer. (c) Cora_Ml.

5.6 Result: importance of repairer

In the previous subsection, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of our proposed framework. In this section, our goal is to understand the feasibility of our restore edge operation.

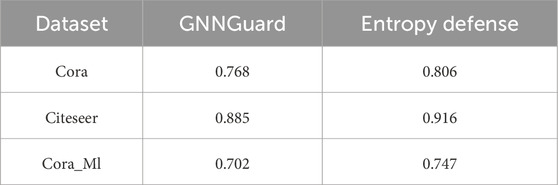

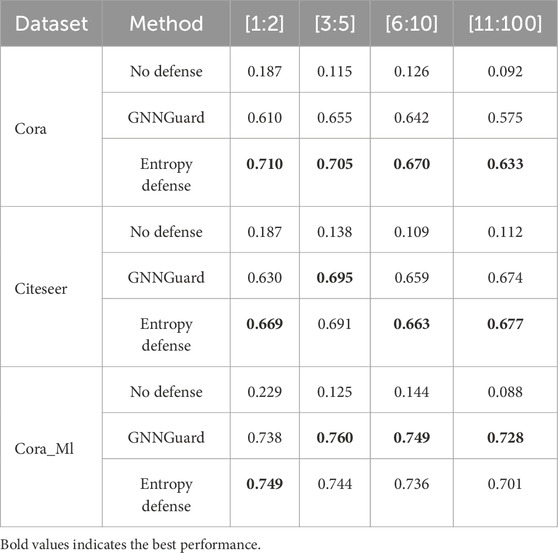

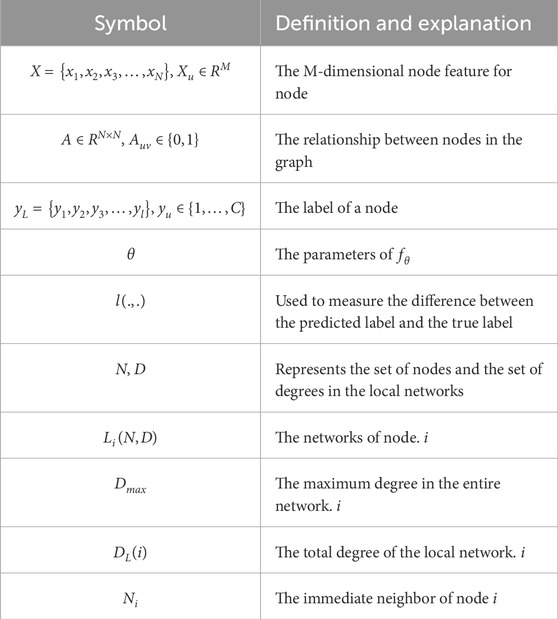

As can be seen from Figure 8, low-degree nodes still account for the majority in the dataset, and low-degree nodes are more vulnerable to attacksZügner et al. [25], so to defend against adversarial attacks more effectively, starting from the low-degree nodes is undoubtedly a better choice. Table 4 confirms our idea, we selected 1% nodes with the smallest node degree for testing, and the results show that our method performs better than GNNGuard on low degree nodes.

Table 2. Defense performance (multi-class classification accuracy) against influence targeted attacks.

Table 4. Node classification performance under 25% pertubation rate non-targeted attack (mettack) for 1% nodes with the smallest node degree.

To make our method more convincing, we randomly selected 30 nodes with different degree distributions on the graph after the Nettack attack and verified our conjecture by randomly cropping a neighboring edge of these nodes. The experimental results in Table 5 show that for low-rank nodes, the cropping neighbor edge attack renders the excellent defense method such as GNNGuard Zhang and Zitnik [16] ineffective, while our method is significantly better for low-rank nodes.

Table 5. Defense performance (multi-class classification accuracy) against nettack and extra prune perturbation with different degree distribution nodes.

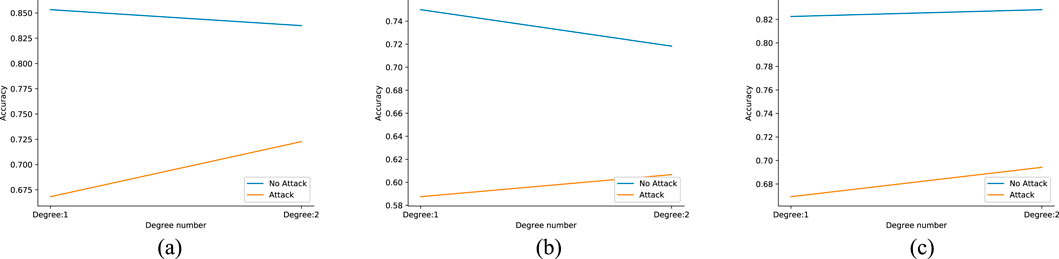

As can be seen in Figure 8, low-rank nodes make up a large percentage of the entire graph. We deliberately tested the effect of the attack of randomly pruning an edge against 30 low-rank nodes on three datasets, and the experiments show that the protection effect of GNNGuard Zhang and Zitnik [16] against this attack is very small, and even reduces the prediction effect. On the other hand, our method is very effective in protecting against this attack, and can even approach the prediction accuracy before the attack. Figures 9, 10 show the experimental results.

Figure 9. Defense performance against the prune attack on nodes of degree 1. (a) Cora. (b) Citeseer. (c) Cora_Ml.

Figure 10. Defense performance against the prune attack on nodes of degree 2. (a) Cora. (b) Citeseer. (c) Cora_Ml.

We focus on low-rank nodes, so we found an interesting phenomenon in our experiments, and Figure 11 illustrates our findings. In low-rank nodes (we refer here to nodes with degree 1 and degree 2), except in the Cora_Ml dataset, an increase in degree instead decreases the prediction accuracy of the node and increases the resistance of the graph itself to the pruning edge attack. This also confirms our judgment that our defense method against low-rank nodes connecting edges is effective.

Figure 11. Low-ranked nodes of varying degrees under prune attack. (a) Cora. (b) Citeseer. (c) Cora_Ml.

6 Conclusion

In this study, we introduced Entropy Defense, a novel algorithm designed to safeguard neural networks against poisoning attacks. At its core, Entropy Defense operates by calculating the similarity between local structures of nodes, enabling it to selectively reduce edges. This approach adeptly minimizes the negative impacts during information transfer within GNNs, leaning heavily on both feature and structural similarities of nodes–two pivotal elements for a robust defense. As a result, Entropy Defense has the capability to reconstruct the graph structure extensively and eliminate potential deceptive edges. This method is underpinned by the concept of network homogeneity. A standout feature of our work is the innovative strategy to counteract adversarial attacks, emphasizing the restoration of the graph structure to its original, unperturbed state. Looking ahead, our objective is to refine our approach in line with established models, aiming to develop an even more effective and resilient algorithm, while also exploring applications beyond node classification.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://github.com/mims-harvard/GNNGuard.

Author contributions

ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. ZZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Huang Y, Yu J, Wang D, Lu X, Dufaux F, Guo H, et al. Learning-based fast splitting and directional mode decision for vvc intra prediction. IEEE Trans Broadcasting (2024) 70:681–92. doi:10.1109/TBC.2024.3360729

2. Wang D, Zhu C, Sun Y, Dufaux F, Huang Y. Efficient multi-strategy intra prediction for quality scalable high efficiency video coding. IEEE Trans Image Process (2019) 28:2063–74. doi:10.1109/TIP.2017.2740161

3. Wang D, Sun Y, Zhu C, Li W, Dufaux F, Luo J. Fast depth and mode decision in intra prediction for quality shvc. IEEE Trans Image Process (2020) 29:6136–50. doi:10.1109/TIP.2020.2988167

4. Li C, Ma J, Guo X, Mei Q. Deepcas: an end-to-end predictor of information cascades. In: Proceedings of the 26th international conference on world wide web (2016).

5. Huang Z, Wang Z, Zhang R. Cascade2vec: learning dynamic cascade representation by recurrent graph neural networks. IEEE Access (2019) 7:144800–12. doi:10.1109/access.2019.2942853

6. Guo Z, Wang H. A deep graph neural network-based mechanism for social recommendations. IEEE Trans Ind Inform (2021) 17:2776–83. doi:10.1109/tii.2020.2986316

7. Shi C, Xu M, Zhu Z, Zhang W, Zhang M, Tang J. Graphaf: a flow-based autoregressive model for molecular graph generation. ArXiv abs/2001 (2020):09382.

8. Li X, Zhang Y, Wang J, Lu M, Lin H. Knowledge-enhanced dual graph neural network for robust medicine recommendation. 2022 IEEE Int Conf Bioinformatics Biomed (BIBM) (2022) 477–82.

9. Kazi A, Cosmo L, Ahmadi S-A, Navab N, Bronstein MM. Differentiable graph module (dgm) for graph convolutional networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Machine Intelligence (2023) 45:1606–17. doi:10.1109/tpami.2022.3170249

10. Deng Z, Sun C, Zhong G, Mao Y. Text classification with attention gated graph neural network. Cogn Comput (2022) 14:1464–73. doi:10.1007/s12559-022-10017-3

11. Yao L, Mao C, Luo Y. Graph convolutional networks for text classification. ArXiv abs/1809 (2018):05679.

12. Zhao Y, Song X. Textgcl: graph contrastive learning for transductive text classification. In: 2023 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN) (2023). p. 1–8.

13. Wu C, Liu X, Ding K, Xin B, Lu J, Liu J, et al. Attack detection model for bcot based on contrastive variational autoencoder and metric learning. J Cloud Comput (2024) 13:125. doi:10.1186/s13677-024-00678-w

14. Huang Y, Lu X. Editorial: security, governance, and challenges of the new generation of cyber-physical-social systems. Front Phys (2024) 12:1464919. doi:10.3389/fphy.2024.1464919

15. Zhang Q, Li M, Deng Y. Measure the structure similarity of nodes in complex networks based on relative entropy. Physica A-statistical Mech Its Appl (2018) 491:749–63. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2017.09.042

16. Zhang X, Zitnik M (2020). Gnnguard: defending graph neural networks against adversarial attacks. ArXiv abs/2006.08149

17. Bruna J, Zaremba W, Szlam A, LeCun Y. Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs. CoRR abs/1312.6203 (2013).

18. Defferrard M, Bresson X, Vandergheynst P. Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering. In: Neural information processing systems (2016).

19. Kipf T, Welling M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. ArXiv abs/1609 (2016):02907.

20. Wu F, Zhang T, de Souza AH, Fifty C, Yu T, Weinberger KQ. Simplifying graph convolutional networks. In: International conference on machine learning (2019).

21. Gilmer J, Schoenholz SS, Riley PF, Vinyals O, Dahl GE. Neural message passing for quantum chemistry. In: International conference on machine learning (2017).

22. Hamilton WL, Ying Z, Leskovec J. Inductive representation learning on large graphs. In: Neural information processing systems (2017).

23. Velickovic P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio’ P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. ArXiv abs/1710 (2017):10903.

24. Atwood J, Towsley DF. Diffusion-convolutional neural networks. In: Neural information processing systems (2015).

25. Zügner D, Akbarnejad A, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on neural networks for graph data. In: Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining (2018).

26. Liu G, Huang X, Yi X. Adversarial label poisoning attack on graph neural networks via label propagation. In: European conference on computer vision (2022).

27. Zügner D, Günnemann S. Adversarial attacks on graph neural networks via meta learning. ArXiv abs/1902.08412 (2019).

28. Wang B, Zhou T, Lin M-B, Zhou P, Li A, Pang M, et al. Evasion attacks to graph neural networks via influence function. ArXiv abs/2009 (2020):00203.

29. Zhang H, Wu B, Yang X, Zhou C, Wang S, Yuan X, et al. Projective ranking: a transferable evasion attack method on graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the 30th ACM international conference on information & knowledge management (2021).

30. Dai E, yin Lin M, Zhang X, Wang S. Unnoticeable backdoor attacks on graph neural networks. In: Proceedings of the ACM web conference 2023 (2023).

31. Goodfellow IJ, Shlens J, Szegedy C. Explaining and harnessing adversarial examples. CoRR abs/1412 (2014) 6572.

32. Jia R, Liang P (2017). Adversarial examples for evaluating reading comprehension systems. ArXiv abs/1707.07328

33. Wu H, Wang C, Tyshetskiy YO, Docherty A, Lu K, Zhu L. Adversarial examples for graph data: deep insights into attack and defense. In: International joint conference on artificial intelligence (2019).

34. Entezari N, Al-Sayouri SA, Darvishzadeh A, Papalexakis EE. All you need is low (rank): defending against adversarial attacks on graphs. In: Proceedings of the 13th international conference on web search and data mining (2020).

35. Zhu D, Zhang Z, Cui P, Zhu W. Robust graph convolutional networks against adversarial attacks. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining (2019).

36. Jin W, Li Y, Xu H, Wang Y, Tang J (2020). Adversarial attacks and defenses on graphs: a review and empirical study. ArXiv abs/2003.00653

37. McCallum A, Nigam K, Rennie JDM, Seymore K. Automating the construction of internet portals with machine learning. Inf Retrieval (2000) 3:127–63. doi:10.1023/a:1009953814988

38. Sen P, Namata G, Bilgic M, Getoor L, Gallagher B, Eliassi-Rad T. Collective classification in network data. In: The AI magazine (2008).

39. Hu W, Fey M, Zitnik M, Dong Y, Ren H, Liu B, et al. Open graph benchmark: datasets for machine learning on graphs. ArXiv abs/2005 (2020):00687.

40. Li Y, Jin W, Xu H, Tang J. Deeprobust: a pytorch library for adversarial attacks and defenses. ArXiv abs/2005 (2020):06149.

41. Xu K, Hu W, Leskovec J, Jegelka S. How powerful are graph neural networks? ArXiv abs/1810.00826 (2018).

Keywords: meteorological monitoring, CPSSs, graph neural networks, adversarial defense, entropy defense

Citation: Lai M and Zhou Z (2025) Entropy defense-by-restore: a GNN-empowered security and trust framework for meteorological cyber-physical-social systems. Front. Phys. 13:1659899. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1659899

Received: 04 July 2025; Accepted: 29 October 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jianping Gou, Southwest University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yuan Tang, Chengdu University of Technology, ChinaTianxi Huang, Chengdu Textile College, China

Yuqi Li, CUNY, United States

Copyright © 2025 Lai and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zeyu Zhou, dmVyaXR5b3dlbnM5NjE2QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Ming Lai1

Ming Lai1 Zeyu Zhou

Zeyu Zhou

![Three pie charts comparing degree distributions. Chart (a) for Cora shows segments: 47.3% [3:5], 36.2% [1:2], 12.7% [6:10], 3.8% [11:100]. Chart (b) for Citeseer shows segments: 52.2% [1:2], 32.0% [3:5], 12.0% [6:10], 3.8% [11:100]. Chart (c) for Cora_MI shows segments: 34.5% [1:2], 33.1% [3:5], 20.3% [6:10], 12.1% [11:100].](https://www.frontiersin.org/files/Articles/1659899/fphy-13-1659899-HTML/image_m/fphy-13-1659899-g008.jpg)