- 1Department of Physics, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, United States

- 2Department of Sciences and Mathematics, California State University Maritime Academy, Vallejo, CA, United States

- 3School of Psychology, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia

- 4Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden

- 5Department of Psychology, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, United States

- 6Department of Physics, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 7Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA, United States

We investigate the artistic patterns generated by the pouring technique made famous by Jackson Pollock. To determine if poured patterns can be distinguished based on the artist age, we apply computer analysis techniques to paintings created under controlled conditions by children (four to six years old) and adults (18–25 years old) pouring fluid paint onto horizontal sheets of paper. Both groups of art display a high visual complexity due to the multi-scaled paint structure generated by the pouring process. However, the two groups demonstrate statistically significant differences when this structure is quantified using both multifractal and lacunarity analysis. Whereas the multifractal analysis probes the scaling characteristics of the patterns, lacunarity quantifies clustering in their spatial distributions. We find that the children’s paintings are characterized by smaller fractal dimensions (indicating a reduced contribution of fine structure) and by larger lacunarity parameters (indicating a larger clustering of this fine structure) compared to the adult paintings. We compare these results to those of two famous poured works by Jackson Pollock and Max Ernst as a preliminary step to investigating the potential origins of the fractal and lacunarity variations across artists, which includes motions related to biomechanical balance. Finally, to examine the impact on audiences, we ask observers to rate their perceptions of the paintings. These ratings indicate a rise in interest and pleasantness for paintings with lower fractal dimensions and larger lacunarity.

1 Introduction

The interface between art and science has grown over the past three decades with the advent of statistical analysis of the visual characteristics of art works. Although such studies now encompass a broad range of artistic styles, substantial research has been devoted to paintings generated by pouring paint onto the canvas rather than by using traditional brush contact. A number of Twentieth Century artists pursued this technique, including the European Surrealists [1], the Canadian Les Automatists [2], and the American Abstract Expressionists [3]. The latter featured the most famous proponent of the ‘pouring’ technique, Jackson Pollock [4].

Celebrated as Action Painting, these poured works serve as records of the artists’ encounters with their canvases. In Pollock’s case, this encounter involved him painting in the three-dimensional space above the canvas and then letting gravity condense the fluid paint onto the two-dimensional plane of the canvas laid out across the floor. This dynamic process often unfolded at frantic painting speeds, inviting speculation from art critics and the public alike as to whether it is possible to control the pouring technique. Perhaps all artists are instead destined to generate haphazard records of their encounters with the canvas. This debate has been fueled by the lack of traditional compositional strategies displayed in typical poured works - no center of focus, no left or right, and no up or down [3, 4]. Furthermore, respected scholars have misidentified imitations as masterworks in high profile controversies [5–7], suggesting that Pollock’s specific application of the pouring technique might not be unique.

Statistical analysis offers the possibility of resolving this debate by distinguishing between poured patterns generated by different artists. Fractal analysis, which assesses patterns at multiple size scales, has been proposed as a useful tool for quantifying Pollock’s patterns [8–12]. This choice of analysis was motivated by the possibility that the pouring technique might avoid the size restrictions imposed by hand-brush motions and so free up a broader range of body motions. These could then translate into multi-scaled paint trajectories on the canvas that might not be possible within the constraints of traditional painting techniques. A second motivation derived from the fact that natural scenery is composed of fractal patterns [13]. Many observations (made both by Pollock and subsequent art theorists) highlighted the similarity between his patterns and those found in nature [4].

Initial fractal studies calculated the paintings’ ‘covering’ dimension D0, which quantifies the amount of canvas surface covered by paint at different scales [8–12]. These were quickly followed by multi-fractal studies which employed a spectrum of dimensions, D0 to D50, to assess increasingly sophisticated statistical qualities at different scales [14, 15]. Various scaling measures have since been applied to different visual qualities of Pollock’s paintings [16–29]. Significantly, these fractal approaches received support across the disciplines, ranging from the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot who introduced the term “fractal,” to chief Pollock scholar Francis O’Connor [30, 31].

Whereas many of these studies aimed to gain new insights into the subtle visual characteristics of poured paintings, fractal analysis was also proposed as a potential authenticity tool to distinguish Pollock’s paintings from replicas [5, 6, 11]. Although its application to a high-profile authenticity dispute initially stirred controversy [5, 6], a subsequent artificial intelligence (AI) approach demonstrated a 96% classification accuracy by combining fractal parameters with other pattern-analysis parameters [32]. Of these parameters, the fractal character was found to be the dominant predictor [32]. A similar technique was found to be more accurate than adults and children in distinguishing paintings of abstract expressionists [33]. A more recent AI technique also exploited fractal qualities in poured paintings to distinguish Pollocks with a 99% accuracy [34]. Although our current study is not aimed at developing authenticity tools, it is nevertheless inspired by the fact that different artists have the potential to generate different poured signatures. To investigate the physical origin of such differences, we aim to go beyond the spectrum of fractal dimensions previously used to capture the multi-scaled complexity of poured works.

Previous pattern investigations of art [35, 36] and design strategies such as urban planning [37] have benefitted from a multi-scaled technique known as lacunarity analysis [38]. While fractal analysis quantifies the scaling behavior of the spatial distribution of the paint, lacunarity focuses instead on variations in the voids between the clusters. Introduced by Mandelbrot, the term is derived from “lake” [13] to reflect the geographic analogy with gaps in land distributions. Morphologically, lacunarity probes the textural “clumpiness” originating from translational variations in void sizes at different locations across the canvas. Previously, lacunarity techniques have been applied successfully to a range of physical systems. Examples include categorizing agricultural processes [39], distinguishing geophysical data from different landscapes [40], identifying bone defect patterns in patients afflicted with osteoporosis [41], and investigating the physical distribution of galaxies in the universe [42, 43]. Given this diverse application to natural patterns along with the similarity of Pollock’s work to natural images, it is an obvious extension to translate this statistical tool to the analysis of poured paintings. Lacunarity has the potential to identify new structures and ‘fingerprints’ within poured masterworks. In doing so, this approach might add valuable information for authenticity studies and might also provide a new ‘eye’ on a much debated, revolutionary art technique.

Our research goal is to apply lacunarity analysis to controlled poured-painting experiments with systematic data collection and reproducible analysis. In particular, we will determine whether the lacunarity’s probing of spatial ‘clumpiness’ of poured paint trajectories is sensitive to differences in the body motions of artists of different ages. We will consider two distinct groups of artists - children and adults. These two populations are at different developmental stages of their biomechanical balance physiology. Our investigation is motivated by experiments showing that balancing motion displays non-linear characteristics such as fractal patterns [43–61]. In addition to postural sway during standing, these studies extend to dynamical balance actions during walking [57], sports [58, 59], dancing [60, 61], and martial arts [55]. These biomechanical balance studies build on a growing body of work showing the prevalence of fractals in human physiology [62]. If balance physiology plays a dominant role in the painting process, we hypothesize that distinctly different fractal and lacunarity characteristics will be detected in the final paintings created by the children and adults.

Because our preliminary study does not include a direct measurement of the biomechanical balance of the two artist groups, we discuss additional inter-group factors and how these might contribute to the pattern variations. As a motivation for future experiments, we also make a preliminary comparison with two famous poured works by Jackson Pollock (Number 14, 1948) and Max Ernst (Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly, 1942) [4]. These choices are informed by the potentially differing roles played by balance motion in their specific applications of the pouring technique [4, 30].

Finally, we build on our investigations of generating art by considering the act of observation. Previous studies have shown that observers can distinguish between abstract art created by children and adults [63, 64]. Here, we focus on the adult poured paintings and ask a group of observers to rate them in terms of their perceived pleasantness and interest. Given that the fractal repetition of patterns naturally generates high visual complexity, we also consider the perceived complexity of the poured patterns. The goal is to investigate whether there are correlations between these ratings and the fractal and lacunarity characteristics of the paintings.

2 Methods

2.1 Image generation and acquisition

To examine the potential of lacunarity analysis, we employed ‘Dripfests’ which invited participants to paint in the pouring style of Pollock. The pouring technique is influenced both by artists’ physical motions and their choice of materials. The Dripfests provide a controlled environment which standardizes the materials used - for example, the type of canvas, paint, and painting implement. By doing so, our investigations focus on the impact of the artists’ motions. Our work builds on recent investigations which interpret the pouring process through the scientific lens of fluid dynamics [65, 66]. Whereas these studies considered the role of the painting implement’s speed and height relative to the canvas, our experiments also incorporate the patterns traced out by the changing directions of the artists’ motions.

We recruited 18 children (four to six years old) and 34 adults (18–25 years old) for the Dripfest experiments. No inclusion nor exclusion criteria were applied to applicants. We supplied them with identical horizontal surfaces (sheets of paper with dimensions of 61.6 cm by 95.5 cm) and identical vinyl paint diluted to a common fluidity suitable for pouring. They were each supplied with a container positioned on the ground close to the paper. Because the container was not lifted by the participants, container size was not adjusted across the two age groups in any attempt to adjust for weight. Participants were supplied with identical mixing sticks for them to transfer the paint to the paper through the air. Participants were shown the same examples of Pollock’s poured paints and were issued identical verbal requests “to create a painting like the ones shown.” Clarifications were provided when asked. Each participant was allowed to create just one painting. Participants were allocated 40 min, which exceeded the time needed to perform their task in all cases.

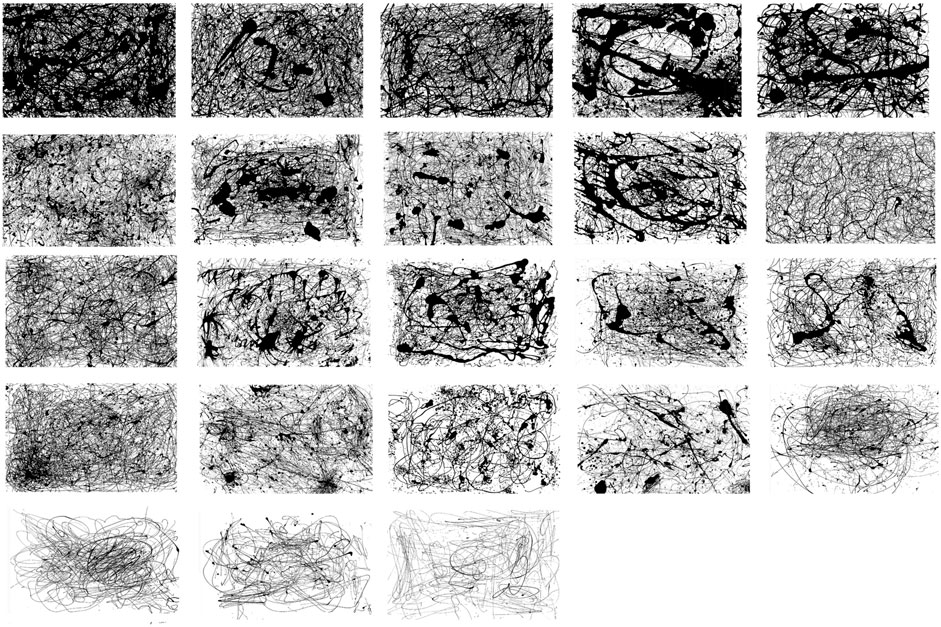

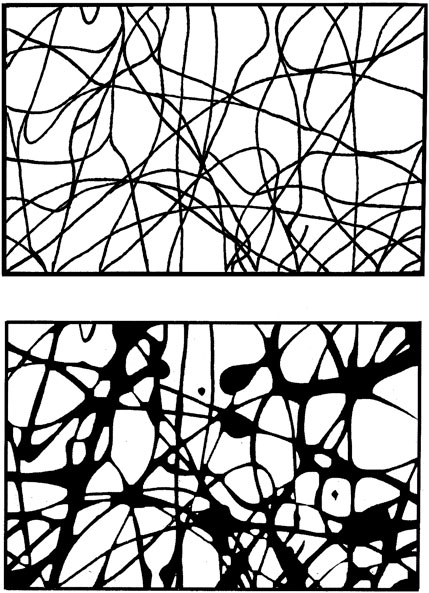

For simplicity of analysis and interpretation, the study considers monochromatic paintings on a white background. The paintings were scanned at a pixel size of 0.3 mm to ensure resolution of the finest paint features (∼1 mm). Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 (57.8 × 78.8 cm) [4] and Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly (75 × 60 cm) [4] were scanned from high-quality prints. The images were thresholded at 50% when converting the grayscale images to binary (black and white) images. Visual inspection confirmed that small variations in the threshold value did not change the visual appearance of the binary image. We also confirmed that the variations did not change the count of the number of the binary image’s black pixels. We note that Ernst planned to tap into his subconscious by using the resulting paint trajectories as a springboard for free association. Accordingly, he perceived the image of a face in the paint trajectories of Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a non-Euclidean Fly [4] and developed the painting further by sketching in a colored face. For the purposes of our study, we are interested in the underlying poured trajectories, and we therefore electronically extracted these trajectories for our analysis using color-separation techniques previously developed for analysis of the painted layers of Jackson Pollock paintings [11]. Figure 1 shows representative examples of the Dripfest paintings.

Figure 1. Representative examples of 23 poured paintings generated during the Dripfest experiments. The first 19 are by adults (Adult19, 13, 32, 34, 7, 3, 18, 27, 23, 12, 9, 26, 16, 20, 29, 31, 4, 5, and 2) and the last four are by children (Child16, 5, 11, and 4).

2.2 Image analysis

2.2.1 Lacunarity analysis

The traditional algorithm for determining the lacunarity of a pattern is the gliding box technique [38]. Consider a painting image of height H and length LT containing occupied pixels (i.e., sites featuring the painted pattern) and unoccupied pixels (sites featuring the painting’s background). A square box of side-length L < LT is placed at one corner of the painting and the density of occupied pixels (s) within the box is determined. The box is then advanced along the painting by a small increment ε = 3 mm, and the density is calculated for each advancement over the painting’s entire length and height. By plotting the number of boxes featuring pixel density s measured for the box size L, the frequency distribution of densities, n(s, L), is then generated. This can be converted to a probability density, p(s, L), by normalizing the density with respect to the total number of boxes NT(L) of box size L. A box is considered to be occupied if it contains one or more occupied pixels. The number of occupied boxes, N(L), is obtained by summing over the boxes of a given size L. The value of L is reduced in equal increments of 3 mm. The first and second moments of this distribution of occupied pixels are calculated as

These first and second moments (Equations 1, 2) relate to the mean and variance of the distribution, respectively. The lacunarity of the pattern at the scale L is then defined by the ratio

Given that Λ(L) is proportional to the distribution’s variance, patterns characterized by large variations in void size will be quantified by large lacunarity, while tightly clustered patterns with little void variation will show low lacunarity. A scaling plot can be generated by repeating this calculation of Λ(L) in Equation 3 for decreasing box sizes and plotting log Λ(L) vs. log(L). The shape of the resulting lacunarity scaling curve yields rich information about the statistical nature of the clustering. For example, pure fractal distributions result in a linear curve on the log-log scaling plot [38].

In addition to the curve’s shape, additional parameters are useful for quantifying the scaling behavior of the pattern. For example, the zeros of the lacunarity curve serve to uniquely identify fundamental scale sizes of the pattern. The difference between the maximum and minimum values of log(Λ(L)) across a given scaling range is defined as the lacunarity depth

and the lacunarity slope (the average rate at which the lacunarity changes with scale) is given by

A pattern with little change in clumpiness as the size scale L is reduced is said to show little “depth”

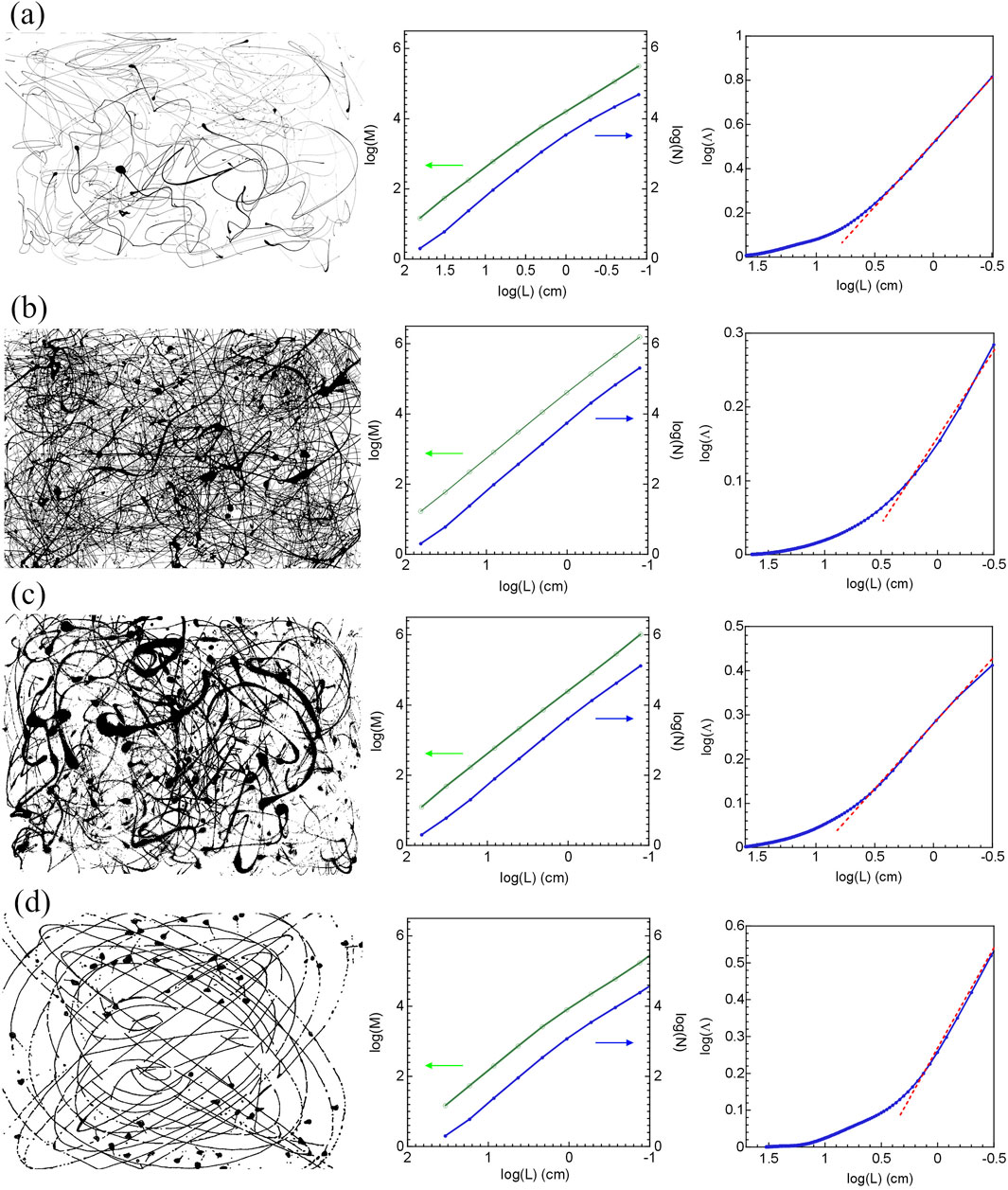

These concepts are demonstrated in Figure 2 for two poured paintings featuring unusual painted features. In each case, the lacunarity scaling curve (Λ(L) vs. log(L)) shows a gradual increase in Λ(L) with decreasing scale L. Measured over identical scaling ranges, the overall change in Λ(L) is larger for the top painting and so it shows greater lacunarity depth and slope. In both cases, a painted feature (a large blob and a dense band) dominates the pattern density at around the 10 cm scale. This can be seen in the scaling plots as a rise in Λ(L). This rise is bigger for the top image because the blob has a higher density.

Figure 2. Demonstrations of the lacunarity analysis. Images of the paintings (61.6 × 95.5 cm) are shown on the left and their lacunarity scaling curves are shown on the right. The top painting is Child1 and the bottom painting is Adult15.

For all Dripfest paintings we employ box sizes ranging from L = 4 pixels (∼1mm, corresponding to the finest observed paint feature) up to L = 2048 pixels (∼61 cm, corresponding to the width of the sheet of paper). The smallest L value examined (the fine-scale “cut-off”) is set at 2.5 mm to avoid resolution issues and the largest (the coarse-scale ‘cut-off’) is set to L = 31 cm to match the scaling range used in the fractal analysis (see below). A linear slope is fitted to the scaling region that generates the largest R2. Although the L range of this linear region typically spans from the smallest analyzed L value up to a “transition” value of approximately 5 cm, the precise range varies between paintings. Accordingly, we do not measure ς based on the slope of this linear fit. Instead, we adopt a standardized approach of calculating the slope based on the lacunarity depth

2.2.2 Fractal dimension

Fractal dimension D0 describes how the patterns occurring at different magnifications combine to build the resulting fractal shape of the painting [8, 13]. For a painting consisting simply of a smooth line (i.e., containing no fractal structure), D0 has a value of 1, while for a completely filled canvas (again containing no fractal structure), its value is 2. However, the repeating patterns of a fractal line cause the line to begin to occupy space at different size scales. As a consequence, its D0 value lies between 1 and 2. For a poured painting featuring many fractal lines, its D0 value will similarly lie between 1 and 2.

Whereas the traditional method for lacunarity studies is the gliding box technique, the traditional algorithm for determining the fractal dimension of a pattern is the box-counting technique [13]. The two methods share various commonalities, and the box counting technique can be seen as a subset of the gliding box technique. Following the same procedure as the lacunarity analysis, the square box of side-length L < LT is placed at one end of the painting and the box is advanced along the painting by increment ε. Instead of calculating the density s of occupied pixels within each box, the ‘box counting’ technique simply determines if the box contains any occupied pixels. The number of occupied boxes, N(L), is summed for the given box size L. The scale invariance of fractals is generated by the power law N(L) ∼ L−D0 [13] and so D0 can be extracted by fitting the slope of the linear region of the scaling plot log(N) vs. log(L).

The box-counting method therefore assesses the coverage of the pattern at different size scales and the extracted fractal dimension is referred to as the covering dimension. The steeper slopes for high D0 fractals are indicative of the higher number of occupied boxes at fine scales when compared to an equivalent low D0 fractal. As such, the D0 value has an important impact on the visual appearance of fractal patterns. For fractals described by low D0 values, the small content of fine structure builds a very smooth, sparse shape. However, for fractals with D0 values closer to 2, the larger amount of fine structure builds a shape full of intricate, detailed structure [12, 67, 68]. More specifically, because the D0 value charts the relative contributions of fine to coarse structure, D0 serves as a convenient measure of the visual complexity generated by the repeating patterns.

2.2.3 Multifractal theory

Covering dimension belongs to a “multifractal” spectrum of dimensions. Accordingly, D0 joins an infinite number of dimensions Dq, -

where pi(L) is the relative density of the pattern contained in the box discussed earlier.

The logarithmic slope τ(q) of the partition function Z(q,L) is related to the multifractal dimension Dq according to the relationship

In the limit q = 0, the expression for Z(q, L) in Equation 6 reduces to N and we obtain our standard relationship N(L) ∼ L−D in which D = D0. When

It has been shown [38] that in the case of linearity, the slope ς of the lacunarity spectrum Λ(r) yields the correlation dimension according to the relationship

where E is the dimension of the space in which the fractal pattern is embedded (E = 2 for our two-dimensional canvases). Therefore, measuring correlation dimension becomes a second approach to probing lacunarity. A convenient measure of the depth of a multifractal is defined as ΔD = D0 −

A multifractal analysis is performed on each painting by plotting log(N) vs. log(L) to extract D0 and log(M) as calculated in Equation 9 vs. log(L) to extract D2. Some of the scaling plots feature a distinct ‘knee’ at around the 5 cm transition reported in the lacunarity analysis. This knee is indicative of a bi-fractal behavior, whereby the scaling behavior switches between different slopes and therefore different fractal dimensions below and above the transition. Previous Pollock studies have discussed the pouring technique in terms of two interactive pattern-generation processes [8–11]. Pollock’s motions across the canvas are expected to dominate patterns above an approximate transition of 5 cm, while patterns below this scale are expected to be dominated by the paint dynamics of the fluid paint. This model will be considered in more detail in the Discussion section. Previous Pollock investigations employed a bi-fractal fit to the data to quantify the “knee” feature in the scaling plots [11]. These included the transition L value at which the “knee” occurs and the associated change in slopes. Because the knee feature is not the focus of the current study, here we report qualitative observations of their occurrence.

Because of the limited size scales associated with the two scaling behaviors, here we fit the data across the combined size range in part to gain a larger fitting range, but also to emphasize the interactive character of the two fractal generation processes (see Discussion). This approach also ensures that the fractal and lacunarity parameters are analyzed across the same sizes. Both dimensions (D0 and D2) are calculated by linear regression performed on the scaling plot data within the combined range. Using this approach, the linear range spans from 8 pixels to 1024 pixels, corresponding to spanning from 2.5 mm to 31 cm.

Although extended, we emphasize that the fitting range is nevertheless limited compared to infinitely repeating mathematical fractals. Instead, the paintings bear a closer resemblance to so-called ‘limited-range fractals’. These are typical of physical objects due to restrictions on their smallest and largest possible patterns [71]. In our case, the smallest patterns are limited by the finest paint lines (∼1 mm) and the largest are limited by the reduced counting statistics for the larger boxes (the limit of the linear regression fitting procedure is 31 cm, corresponding to only 6 boxes covering the canvas area). Because of their limited range, and also because they quantify two scaling behaviors (below and above the 5 cm transition), we adopt the term ‘effective dimension’ for D0 and D2.

2.3 Image perceptual ratings experiments

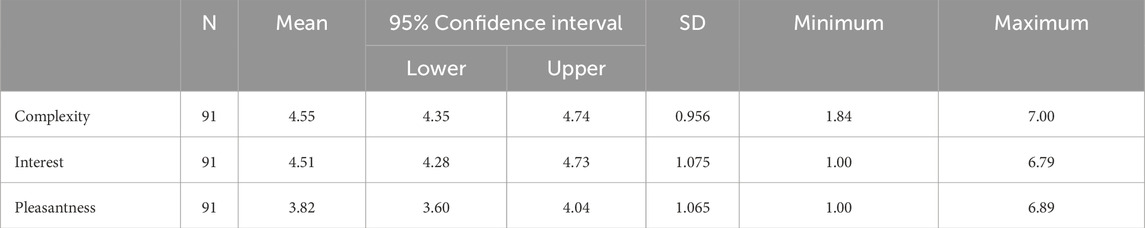

To investigate perceived complexity, visual interest, and pleasantness of poured paintings varying in lacunarity, we recruited 91 participants (23 females, 68 males, 1 nonbinary) via the online recruitment platform, Amazon MTurk. The inclusion criterion was normal or corrected to normal vision. No exclusion criteria were applied to applicants. The average age of participants was 33.85 years (SD = 10.70 years). Most participants were from the USA (68 participants or 74.7%), followed by India (11 participants or 13.2%) and the UK (8 participants or 8.8%). Prior to beginning the experiment, all participants were provided information before indicating their consent. Participants were reimbursed with US$2.50 for their participation.

Because our research focus is on responses to the visual complexity of the painted patterns, 15 of the paintings generated by adults were excluded from this study. These excluded paintings contained features that resembled recognizable patterns such as crosses, diagonal lines, or straight lines. Accordingly, participants rated a total of 19 poured paintings by adults, shown in Figure 1. None of the children’s paintings were included because of the significant difference between adult and children poured paintings’ properties in both fractal dimension and visual appearance.

Each painting was rated on the three bipolar scales to assess their perceived complexity (1-simple to 7-complex), pleasantness (1-unpleasant to 7-pleasant), and interest (1-boring to 7-interesting). Pleasantness was used as the term to assess aesthetic appeal because it was considered to be a broader, more general visual quality than beauty. The paintings were positioned in the middle of the screen and were scaled to subtend 55% of the screen size vertically and horizontally. On each trial, the sliders were positioned below the painting image with the “unpleasant-pleasant” slider on the top, “simple-complex” slider in the middle, and “boring-interesting” slider at the bottom. Before the ratings commenced, participants previewed all paintings to familiarize themselves with their appearance. During the preview stage, paintings were shown without sliders and in a quick succession with each painting displayed for 1.5 s. During the rating phase, the exposure to each painting was unlimited. Participants spent on average 8.6 s (SD = 9.1 s) viewing each painting per trial.

2.4 Human subjects protocols

Adult image generation was granted a protocol exemption from the UO Institutional Review Board. Subject recruitment was conducted starting 01/05/2004, and the paintings were generated during the first two weeks of June 2004 (01/06/2004–15/06/2004). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

Children’s image generation was performed under the UO protocol “Language, Cognition, and Social Cognitive Development” and was approved by the UO Institutional Review Board on 09/11/2001 under an expedited review, given that the data was collected during standard preschool activities and required no experimental intervention beyond consent. The paintings were generated starting on 25/03/2002 and ending on 13/12/2002. The children’s parents gave their written informed consent and their children gave verbal informed consent.

All experimental procedures for the perception experiments were approved by the UNSW Human Research Ethics (UNSW HREAP-C) Advisory Panel for the period starting 20/11/2017 and ending 20/11/2022. Data was collected during a 24-hour period starting on 31/03/2018. All participants provided their written informed consent for the study.

3 Results

3.1 Painting analysis

Figure 3 shows the results of the analysis applied to four paintings: example adult and child paintings, and also to Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 and Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly. The two Dripfest images are representative of the general visual appearances of adult and children’s paintings (see also Figure 1). The adult paintings have higher paint densities than those of the children and they also typically display a larger degree of ‘splatter’ (i.e., larger variation in the width of the paint trajectories).

Figure 3. Representative examples of analysis performed on Child8 (row (a)), Adult9 (row (b)), Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 (row (c)) and Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly (row (d)). The left column shows the painting image, the middle image shows fractal scaling plots (log(M) and log(N) vs. log(L)) and the right column shows the lacunarity analysis (log(

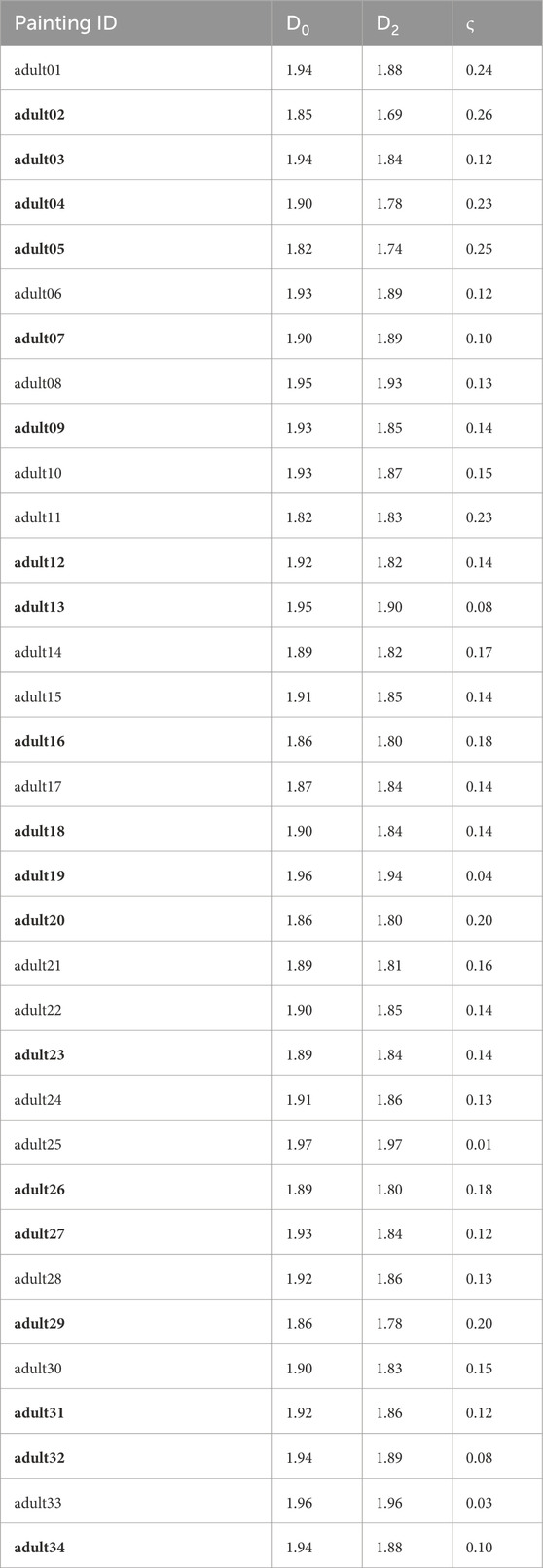

Considering the scaling plots shown in the second column in Figure 3, the covering dimension analysis (the blue data line plotted relative to the right y axis) and correlation dimension analysis (the green data line plotted relative to the left y axis) are shown for the full range of box sizes - from 1 mm up to 61 cm. All paintings reveal a mild knee feature at approximately 5 cm caused by an increase in slope at the larger scales (the top and bottom paintings are examples of distinct knees). The dimensions extracted from the linear regression method applied across the combined range are listed in Tables 1, 2. We note that the D2 values are typically slightly smaller than the corresponding D0 values. The values of both dimensions are typically larger for the adult paintings than for the children’s. The histograms of the covering and correlation dimensions shown in Figure 4 emphasize these findings.

Table 1. A list of the D0, D2, and ς values for the adult paintings (The bolded labels signify paintings that are shown in Figure 1).

Table 2. A list of the D0, D2, and ς values for the children’s paintings (the bolded labels signify paintings that are shown in Figure 1).

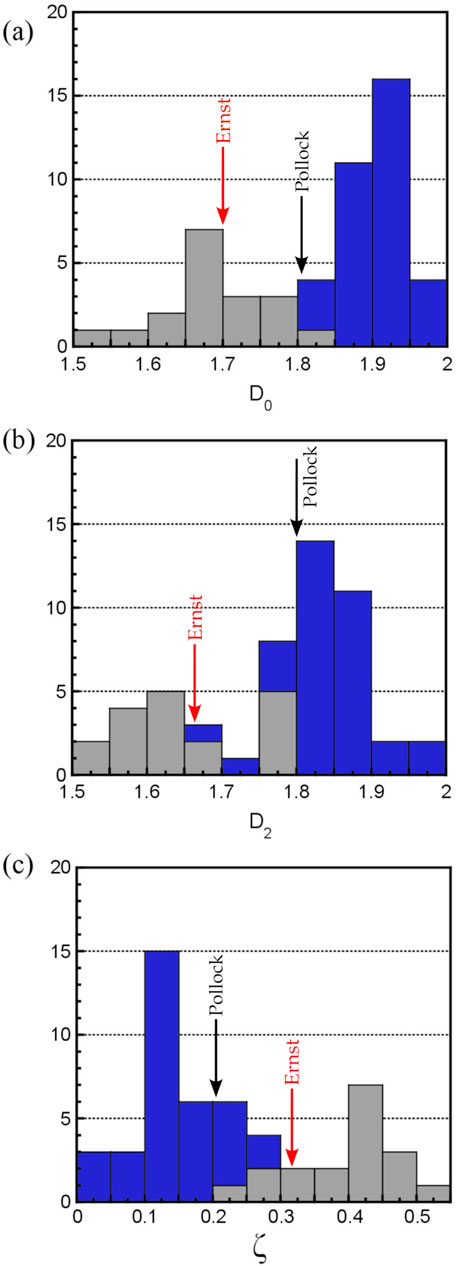

Figure 4. Histograms comparing the adult and children painting scaling parameters: (a) D0, (b) D2 and (c) ς. In each case, blue columns signify the adult paintings and gray columns signify the children’s paintings. The values for Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 are indicated by the black arrows and Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly by the red arrows.

Figure 3 also shows the results of the lacunarity analysis for the four paintings. The lacunarity curves suggest a change in behavior at around the 5 cm transition, similar to that of the dimension curves. In each case, the red dashed line shows a fit to the approximately linear region observed at the smallest scales. While the linear region approximates to the sizes dominated by the paint dynamics, the precise range and shape of the curves vary. The ς values calculated from the lacunarity depth observed across the full size range (Methods) are listed in Tables 1 and 2 and plotted in the histogram in Figure 4c. They are typically larger for the children’s paintings than for those of the adults. In each of the histograms, the values for Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 are indicated by the black arrow and Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly by the red arrow. Whereas the former lies within the adult distribution, the latter lies within the children’s.

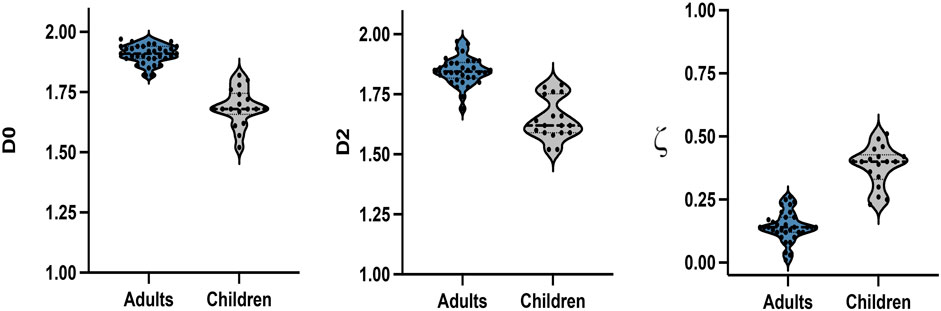

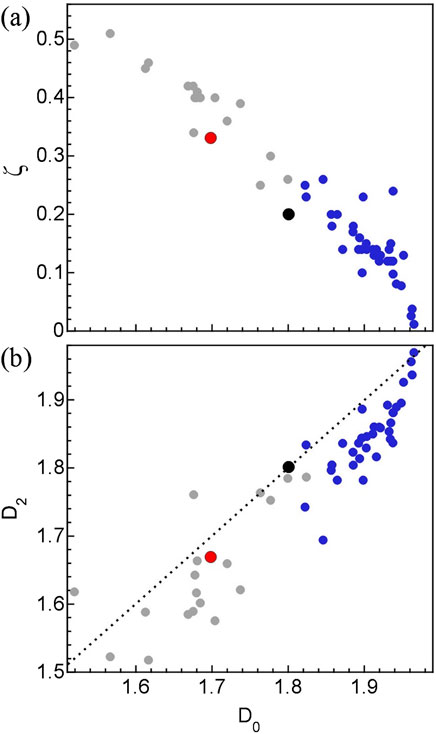

Figure 5 depicts the distribution of the three scaling parameters for paintings generated by the adults and children. Detailed descriptive statistics for the scaling parameters of the two samples of poured paintings are provided in Table 3 below.

Figure 5. The violin plots depicting the distribution of D0 (left panel), D2 (middle panel) and ς (right panel) scaling parameters for paintings produced by adults (blue) and children (gray).

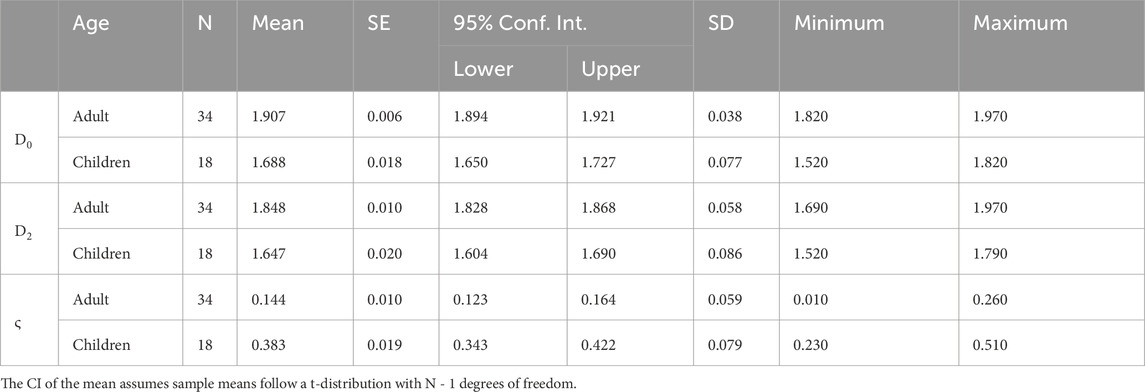

Table 3. A compilation of statistical analyses of the D0, D2, and ς values of the adult and child paintings.

Independent t-tests confirm that there are statistically significant differences in scaling parameters between paintings produced by adults and children for all three scaling parameters. For D0, the paintings produced by adults (M = 1.907) exhibit higher average values than those produced by children (M = 1.688) and this difference is statistically significant (t(50) = 13.8, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 4.01). Similarly, the paintings produced by adults (M = 1.848) compared to those produced by children (M = 1.647) have significantly higher average D2 values (t(50) = 10.0, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.92). Finally, the average lacunarity slope

3.2 Perceptual ratings results

The 15 adult paintings excluded from the perception study feature recognizable objects. There are no statistically significant differences between the included and excluded paintings regarding their lacunarity (t(32) = −0.504, p = 0.617, Cohen’s d = 0.174), D0 (t(32) = 0.716, p = 0.479, Cohen’s d = −0.247), or D2 (t(32) = −2.073, p = 0.046, Cohen’s d = −0.716) when adjusted for multiple comparisons. The 19 selected paintings are therefore representative of the whole group in terms of their fractal and lacunarity parameters.

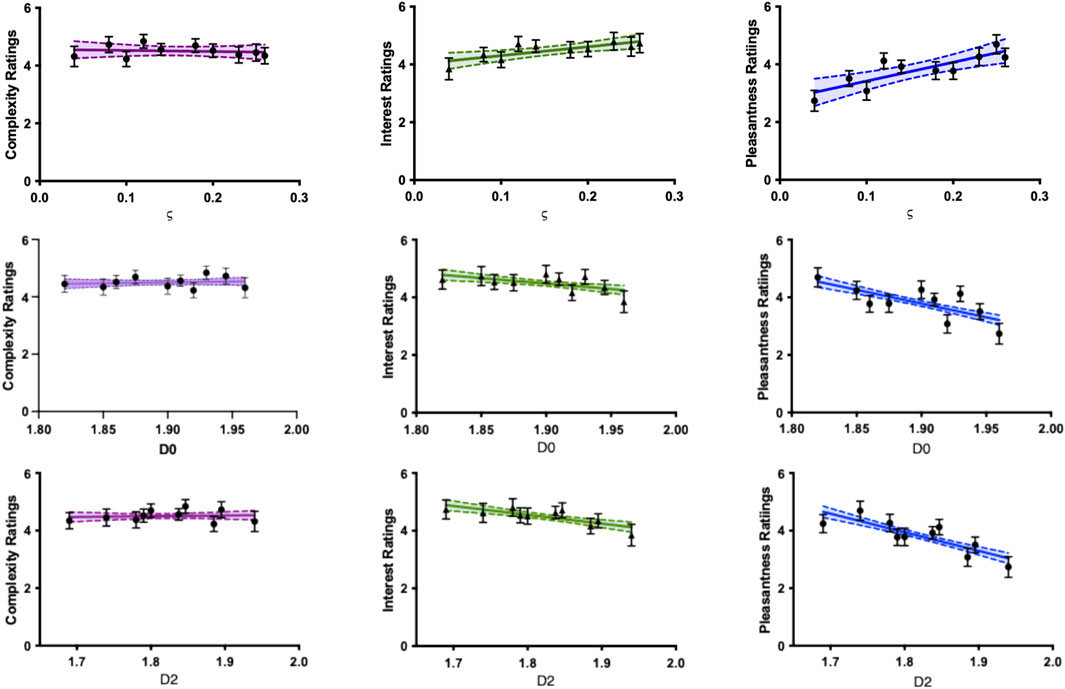

The descriptive statistics for the ratings of complexity, interest and pleasantness are shown in Table 4. The three types of ratings are positively correlated with Pearson coefficients of correlation ranging from 0.270 (p = 0.01) between complexity and pleasantness, to 0.586 (p < 0.001) between complexity and interest. The correlation between ratings of interest and pleasantness is 0.539 (p < 0.01). The average ratings of perceived complexity, interest, and pleasantness as a function of image lacunarity slope ς values are depicted in the top row of Figure 6. We fitted a linear regression model to the complexity, interest, and pleasantness ratings with lacunarity values as a predictor. While there is no statistically significant relationship between lacunarity and perceived complexity (F(1,908) = 0.369, p = 0.529, R2 = 0.0004), the associations between lacunarity and perceived interest (F(1,908) = 21.97, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.024) and pleasantness (F(1,908) = 91.87, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.092) are modest, but statistically significant.

Figure 6. Results of the perceptual rating experiment. Top row: The average ratings of visual complexity (left), interest (middle), and pleasantness (right) are plotted against ς for selected Dripfest paintings. Middle and bottom rows: The average ratings of visual complexity (left), interest (middle), and pleasantness (right) are plotted against fractal scaling dimensions D0 (middle) and D2 (bottom) for selected Dripfest paintings. Error bars represent 95% Confidence Intervals. Colored lines in each panel represent linear regression fits to the data, with shaded regions representing 95% Confidence intervals.

In the middle and bottom rows of Figure 6, we show the same ratings of complexity, interest and pleasantness as a function of fractal dimensions D0 and D2. The linear regression model fitted to the complexity, interest, and pleasantness ratings with D0 and D2 as predictors revealed a similar, but inverse relationship to that observed with lacunarity. The association between D0 and D2 and perceived complexity is not significant (D0: F1,908 = 0.378, p = 0.539, R2 = 0.0004; D2: F1,908 = 0.173, p = 0.677, R2 = 0.0002). The association between D0 and D2 and perceived interest (D0: F1,908 = 11.71, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.0127; D2: F1,908 = 22.11, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.0238) and pleasantness (D0: F1,908 = 67.56, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.069; D2: F1,908 = 90.21, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.092) is again modest, but significant.

4 Discussion

4.1 The interplay between fluid and motion dynamics

We begin with a review of Pollock’s pouring technique to emphasize the relevant size scales over which his patterns were generated. Painting in the air above the canvas, his paint trajectories served as a direct record of his motions. These records capture the multi-scaled movements of his body mechanics, including his hands, arms, torso, and legs. Whereas his motion dynamics defined the direction of the paint trajectories, the shape of their splattered edges was dictated by the second part of the process - the fluid dynamics that evolved under the pull of gravity and subsequent interaction with the canvas. These two interactive patterns can be viewed as the ‘skin’ and ‘bones’ of his poured patterns: the bones represent the trajectories that map out his travels around the canvas (motion dynamics) and the skin represents the splattered variations in the trajectory widths (fluid dynamics).

This interplay between the motion and fluid dynamics is presented schematically in Figure 7. The trajectory patterns (the bones) dominate at scales larger than approximately 5 cm, while the splatter from the fluid dynamics (the skin) dominate below this size transition [9–11]. Both types of patterning feature multi-scaled structure quantified by covering dimensions. We label these dimensions as D0T (the 0 subscript signifies that it is a covering dimension and the subscript T signifies that it is quantifying the trajectory dynamics) and D0S (the subscript S signifies that it is quantifying the spatter dynamics). Because distinct physical factors influence these two processes, the difference in the values of D0T and D0S is expected to vary from artist to artist [11]. Large differences will result in the appearance of the ‘knee’ in the scaling curves at around 5 cm (Figure 3). As with previous Pollock studies [11], the Dripfest painting knees reflect a steeper slope at larger scales (i.e., D0T > D0S). Low splatter paintings potentially create more distinct knees (e.g., the top and bottom paintings of Figure 3) because of the splatter’s lower D0S. Future quantitative studies will examine knee size and occurrence in detail using bi-fractal fits.

Figure 7. Schematic representation of the ‘bones’ (top) and the “skin” and “bones” (bottom) of the poured patterns.

Defining the two size regimes and their associated dimensions is important for investigating the difference between the adult and children’s paintings. We first focus on the lower size regime dominated by the fluid dynamics. The value of D0S is influenced by material parameters such as paint density and viscosity, along with the surface texture and porosity of the canvas. However, these factors are standardized across the two groups of painters in our study and so do not factor into the observed inter-group variations. Differences in artistic technique can also influence the dynamics of the falling paint. Previously, two research groups have interpreted Pollock’s poured paintings in terms of the physics of fluid dynamics [65, 66]. Along with the properties of the paint, these investigations incorporated the height and speed of the painting implement (including both linear and rotational actions) into their fluid dynamics equations. The conditions required to achieve fluid “jets” (continuous flows of paint) rather than discrete drips were examined, along with the potential to manipulate the stability of this flow process (including mastering an instability known as “coiling”). Similar to Pollock’s work [65], both the adult and children’s works are typically dominated by stable jets of paint.

Changes in direction of the artists’ motions are also expected to influence the fluid dynamics. Visual inspection (see, for example, Figures 1, 3) shows that, at the lower size scales dominated by the fluid dynamics process, the children’s trajectories are not splattered and are instead characterized by smoother edges (i.e., with lower D0S values approaching one-dimensional lines). In contrast, the adult paintings feature multi-scaled splatter spreading out from their trajectories. This splatter features an abundance of fine scale structure indicative of high dimensional fractals. These differences in splatter and their associated D0S values could originate from the artists’ motions. Motions characterized by higher D0T values will feature many fine-scale twists and turns in the artist’s directions across the canvas, and this promotes splatter patterns with high D0S values. This emphasizes the interactive nature of the patterns in the two scaling regimes. For conditions such as our Dripfests, in which the materials are standardized, we can therefore expect a degree of correlation between D0T and D0S. This expectation is supported by the observation that all three of our scaling parameters - D0, D2, and

4.2 The potential role of the Artist’s biomechanical balance

Having discussed the sensitivity of D0, D2, and

Of particular interest for the poured painting experiment is the way the two groups accommodate their stability limits. Children have narrower limits, are less accurate in judging them, less cautious as they approach them, and approach them more frequently [89, 94]. Due to their lower coordinated muscle responses, they often over-correct and take longer to restabilize after reaching their limits [83, 89]. During the poured painting task, children would therefore be expected to spend more time close to their limits and change direction less fluidly when responding to them. Children use strategies that minimize their degrees of freedom [90], resulting in more pre-planned ballistic responses [89, 95, 96]. They also restrict themselves to completing one response before initiating the next and directional changes become less fluid [95]. Taken together, these results suggest that the children’s group might show simpler, one-dimensional trajectories that change direction less often when compared to the richer, more varied trajectories of the adults.

Significantly, a growing body of research focuses on the non-linear patterns in people’s postural sway [44–61]. When maintaining balance, the body exhibits multi-scaled sways as an effective biomechanical mechanism for positioning the body relative to the feet and these have been quantified by Lyapunov exponents [44] and fractal dimensions [45]. Differences have been measured between healthy and balance-challenged participants [45], between younger and older adults [47], and also across infant development [48]. Intriguingly, balancing with eyes closed suggests that postural instability increases with a loss of visual information [46]. This might have relevance for activities such as the pouring process that unfold at speeds sufficiently high to limit observations. In addition to stationary balance, fractal characteristics also appear in dynamic activities such as walking [57] and running [58]. While the role of postural sway motion during stationary stance is to fine-tune body motions with centimeter-sized variations, dynamic balance mechanisms require larger sized patterns [58]. Thus, the dynamic balance mechanisms associated with the pouring technique can be expected to span across a significant size range of the scaling plots shown in Figure 3.

A potential interpretation of Figure 4a is that the covering dimensions of the poured patterns (i.e., their D0 values) are being influenced by the fractal characteristics of their biomechanical balance motions. If this is the case, the high D0 values observed in the adult paintings might be indicative of multi-scaled swaying motions that promote their dynamic stability through an effective positioning of their body’s center of mass. In particular, the large contributions from fine scale correctional sways appear to be important. In contrast, the lower D0 values of children’s paintings might arise because their immature biomechanical balance lacks these fine scale corrections. Although speculative, this is consistent with the above developmental research highlighting that younger participants suppress their natural motions as a control strategy, resulting in one-dimensional trajectories that turn infrequently.

Figure 8b shows that the paintings’ D2 values are typically lower than their D0 values. This fall off in dimension with increasing q is expected for multi-fractals and is a signature of their multi-fractal depth. Although the focus of our experiment is on D2 because of its relationship to lacunarity, we note that the fall off continues for higher fractal dimensions. For example, the adult mean values of D0, D2 and D50 are 1.86, 1.84 and 1.82, respectively. The inverse relationship between

Figure 8. (a) A plot of lacunarity slope ς against covering dimension D0, and (b) a plot of correlation dimension D2 against D0. In each case, the blue dots represent paintings by adults and the gray dots represent children’s paintings. The black dot represents Pollock’s Number 14, 1948 and the red dot Ernst’s Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly. In (b), the dashed line represents the condition D0 = D2.

It is interesting to speculate that the low ς values of the adult patterns indicate biomechanical motions of high spatial uniformity that further promote the body’s ability to position its center of mass effectively. In contrast, the clumpiness generated by the children’s ill-coordinated muscle responses leads to spatial gaps in this positioning at fine scales. Such speculations emphasize the need for future experiments that employ measurements of dynamic balance to clarify the role of spatial uniformity in fractal swaying motions. We stress that to date balance research has not benefitted from lacunarity analysis.

Having discussed the potential connection between biomechanical balance motion and the pouring technique for the Dripfest paintings, we finally consider the two example works by Pollock and Ernst. The results of Figures 4, 8 show that Pollock’s painting fits within the adult distributions for D0, D2, and

Ernst’s values lie within the children’s distribution. Although Ernst guided the pendulum with his hands, the paint can was nevertheless constrained by the pendulum string. This partial suppression of natural body motions and inclusion of simpler pendulum oscillations reduces fine scale actions and their spatial uniformity. This could explain his painting’s resemblance to those generated by the limited biomechanical balance actions of the children. Although these speculations are intriguing, we emphasize the preliminary nature of examining only one example of each of these two famous artists’ work.

4.3 Artistic variations beyond biomechanical balance

Scientific investigations of artistic processes are often challenging due to the interplay of a range of psychological and physical factors that contribute to human creativity. The current study serves only as a preliminary step in understanding the factors that drive the pouring technique. In particular, our study did not involve direct measurements of the artists’ biomechanical balance. Although our study builds on experimental demonstrations of the differing biomechanical balance of children and adults [84, 88–94], future experiments should investigate groups of artists with measured differences in their biomechanical balance. Even these proposed groups will feature inter-group variations that go beyond balance. To help inform these future experiments, and to also expand on the factors discussed above for the current experiment, we now consider a selection of additional human factors that might contribute to the pattern variations generated by the children and adults.

We first consider the physical size differences between the two groups. Based on growth charts, the average heights for the children and adults of our study are 110 cm and 168 cm, respectively. Height has been found to influence biomechanical balance even for people of the same age, with additional heights of 10 cm being sufficient to induce instability [97]. Taller artists might also launch paint from a larger distance above the canvas, resulting in a more splattered appearance and contributing to an additional rise in D0S beyond the motion-induced effect described in Section 4.1. This is not inevitable, however. The adults and children had the freedom to vary the painting implement height by adjusting their body angles. To gauge the magnitude of the required adjustments, a simple geometric argument suggests that an adult could match the implement height of an upright child by adopting a full-body lean angle of 40°. Photographs of Pollock painting show that he commonly adopted lean angles of 45°, emphasizing that body height does not necessarily impact D0S directly. We therefore recommend that future experiments use visual recordings to facilitate a quantitative analysis of launch position during painting.

In terms of arm span, growth charts show average values for the children and adults of 105 cm and 163 cm, respectively. Both spans are larger than the 61.5 cm by 95.5 cm dimensions of the sheets of paper, suggesting that both groups could reach over all regions of their paintings with relative ease. Indeed, the artistic challenge more likely relates to ensuring that an appropriate amount of the paint is directed to the canvas rather than landing beyond its boundaries. Recent investigations of Pollock’s work shows that the fractal quality of his patterns deteriorate towards the edge of the work [34]. Even though some paint trajectories left his canvases, the edge was nevertheless important for Pollock’s compositions. If we assume that children and adults are similarly aware of the edge, future experiments should consider sheets of paper that are scaled according to artist reach to explore motion differences related to the physical confinement of their compositions.

Moving on to the artists’ ocular vision, the discussion in Section 4.2 highlights the importance of visual information for maintaining postural stability [47]. Furthermore, investigations of embodied experiences when viewing abstract art reveal that the observer’s postural sway is impacted by the specific visual characteristics of the artwork [98, 99]. Differences in vision might therefore impact the act of creating poured paintings. Typically, children have developed 20/20 acuity along with the ability to accommodate their focus by 5–6 years old. Similar to adults, they can be expected to have normal or corrected vision. Previous studies showing that children and adults can distinguish between various abstract expressionist paintings confirm both groups’ ability to recognize artistic features [63, 64]. In terms of viewing fractal patterns specifically, recent studies found that observers as young as three years old show the same aesthetic preferences as adults [100].

Although children have the acuity to view the same details as the adults, their behavioral approaches to creating art might differ substantially from adults. In particular, although identical instructions were given to the two groups, their interpretation of these instructions and more generally their creative strategies for generating art might differ. This is particularly relevant to pourings, with Pollock’s Action Painting celebrated not just for the completed painting but also for the act of painting [4]. The children and adults might balance this ‘end product’ and ‘action’ differently when replicating Pollock.

Children might also lose concentration more readily. As an example of how this might impact the fractal character of the paintings, the adults typically painted for longer periods than the children and accordingly generated higher density art works. A previous study of Pollock’s work revealed that paintings with higher densities have higher D0S values [10]. This can be understood by returning to the box-counting analysis (see Methods). A higher D0S value indicates a larger number of occupied boxes at small box sizes, suggesting that adding extra amounts of paint contributed mainly to increasing the fine structure. Based on longer painting duration for the adults, we should therefore expect their paintings to be characterized by higher D0S values than those of the children. Figures 3, 4a are consistent with this prediction.

4.4 Perception experiments

Differences in visual perception could also affect the creation process. Previous studies have shown that adults [63] and children [64] can distinguish (adult) abstract expressionist paintings from abstract art created by children. Intriguingly, whereas the adults displayed an aesthetic preference for the abstract expressionist paintings (whether these were labelled correctly or as being made by the children), children preferred paintings that were labelled as being by children even when the label was incorrect [64]. Experiments such as these emphasize the subtle perceptual differences between age groups. The fractal dimensions of Pollock’s work evolved over a decade, suggesting that he could influence the results of his pouring process based on his evolving visual preferences [4]. Given that the children and adults of our study were considerably less experienced and only had one attempt at painting, any capacity to adapt the unfolding patterns based on their perceptions would be intuitive rather than learned.

Our current study focusses on perceptions of the visual complexity generated by the pouring process. Previous perception studies have shown that fractals can induce pareidolia, whereby observers perceive images of common objects in the repeating patterns [101]. To allow participants to respond purely to the complexity, we removed paintings that featured recognizable patterns, whether real or perceived. In the Methods section, we noted that D0 serves as a mathematical measure of the visual complexity arising from the patterns generated at multiple scales. Previous behavioral research has confirmed that people’s perception of complexity increases with D0 [12, 67, 68]. To determine if the texture provided by the clumpiness of the repeating patterns also modifies the visual complexity, it is necessary to limit variations in D0 by considering paintings with similar values. Accordingly, none of the children’s paintings were included because of the significant difference between adult and children poured paintings’ properties in both fractal dimension and visual appearance.

The perception evaluation findings suggest that there are not variations in perceived complexity with changes in paintings’

Although not driven by complexity, there is nevertheless an increase in pleasantness and interest rating in relation to increasing amounts of lacunarity (top row of Figure 6). The clumpiness associated with lacunarity is either influencing these qualities in a manner that goes beyond complexity or perhaps in a manner that observers cannot articulate as being complexity. As expected from the relationships between the paintings’

Finally, we emphasize the limited scaling ranges over which the D0, D2 and

5 Conclusion

In this study, we showed that the artistic patterns generated by the pouring technique can be distinguished based on the artists’ ages. By integrating multi-fractal analysis with lacunarity analysis, we showed that the children’s paintings are characterized by smaller fractal dimensions (indicating a reduced contribution of fine structure) and by larger lacunarity parameters (indicating a larger clustering of this fine structure) than the adult paintings. Our study analyzed the fractal and lacunarity measures across the combined size range spanning above and below the transition length of 5 cm. This was motivated by the expected interplay between the motion dynamics that dominate above 5 cm and the fluid dynamics that dominate below 5 cm. Although this approach successfully distinguished the adult and children’s paintings, the two size regimes show additional distinct behaviors–the smaller scales typically exhibit lower dimensions and more linear lacunarity plots than the larger scales. Future studies will therefore fit the two size regimes separately to identify further differences between the adult and children’s paintings.

Although the primary motivation for the current study is not authentication research, our lacunarity analysis nevertheless highlights that there are detectable variations between different artists who have used the pouring technique. Previous AI techniques developed to distinguish poured paintings benefitted from including fractal parameters [32, 34]. Since AI and machine learning ‘pipelines’ already integrate a range of texture descriptors including lacunarity-like measures (see, for example, [32, 36]), future work could examine whether explicit lacunarity metrics provide additional discriminative power for poured paintings. Furthermore, due to its broad reach across disciplines, previous forms of fractal analysis have helped to establish a connection between the multi-scaled patterns generated by pouring paint and those found in natural scenery [8–12]. Lacunarity parameters could add to the toolbox of pattern analysis techniques capable of quantifying this comparison.

We compared children (four to six years old) and adults (18–25 years old) because these two populations are at different developmental stages in terms of their balance physiology. However, our study did not measure the artists’ biomechanical balance. Accordingly, it serves simply as a preliminary exploration of the various factors that generate the fractal patterns. Our future studies will employ motion sensors attached to the artists during Dripfests. This will allow a direct comparison of their fractal balance motions and the resulting poured patterns within their paintings. The future studies will also include surveys related to the participants’ physical and visual limitations, along with questions aimed at determining individual interpretations of the art creation process.

We also included two art works by Jackson Pollock and Max Ernst because of the different roles played by biomechanical balance in their specific applications of the pouring technique. Our future investigations will expand our lacunarity studies to a larger collection of art by Pollock and other poured artists. The current perception study shows that observers’ ratings of pleasantness and interest increase with increased lacunarity depth. It will be informative to determine whether the relatively high lacunarity of this one Pollock painting within the adult distribution is a consistent characteristic across a broader range of his work. Along with Claude Monet’s cataracts [103], Vincent van Gogh’s psychological challenges [104], and Willem de Kooning’s Alzheimer’s condition [105], art historical discussions of Pollock’s limited biomechanical balance serve as a reminder that conditions that present challenges in aspects of our daily lives can lead to magnificent achievements in art. Affirming this idea through science serves as an additional motivation for future experiments that quantify the relationship between artists’ conditions and the patterns that they create.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Oregon Institutional Review Board, and University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants or the participants’ legal guardians.

Author contributions

MF: Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Software, Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis. CV: Writing – review and editing, Investigation, Formal Analysis. AA: Investigation, Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Resources. DB: Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Methodology. BS: Resources, Visualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Methodology. JM: Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Visualization, Software, Conceptualization, Resources. RT: Writing – review and editing, Methodology, Visualization, Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. JM was a KITP Scholar at the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics. The KITP Scholars Program is supported in part by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. NSF PHY-1748958. RT is a Cottrell Scholar of the Research Council for Science Advancement. The children’s Dripfest was supported by University of Oregon Psychology Department’s undergraduate grant.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Author BS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

2. Mureika JR, Taylor RP. The Abstract Expressionists and Les Automatistes: a shared multi-fractal depth? Signal Process (2013) 93(3):573–8. doi:10.1016/j.sigpro.2012.05.002

6. Miller AI. Colliding worlds: how cutting-edge science is redefining contemporary art. 1st ed. New York, NY: W. W. Norton (2014).

8. Taylor RP, Micolich AP, Jonas D. Fractal analysis of Pollock’s drip paintings. Nature (1999) 399:422. doi:10.1038/20833

9. Taylor RP, Micolich AP, Jonas D. Fractal expressionism. Phys World (1999) 12(10):25–8. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/12/10/21

10. Taylor RP, Micolich AP, Jonas D. The construction of Jackson Pollock's fractal drip paintings. Leonardo (2002) 35:203–7. doi:10.1162/00240940252940603

11. Taylor RP, Guzman R, Martin TP, Hall G, Micolich AP, Jonas D, et al. Authenticating Pollock paintings using fractal geometry. Pattern Recognition Lett (2007) 28:695–702. doi:10.1016/j.patrec.2006.08.012

12. Taylor R, Spehar B, Hagerhall C, Van Donkelaar P. Perceptual and physiological responses to Jackson Pollock’s fractals. Front Hum Neurosci (2011) 5:60. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2011.00060

13. Mandelbrot BB. The fractal geometry of nature. 3rd ed. New York: W. H. Freeman and Comp. (1983).

14. Mureika JR, Cupchik GC, Dyer CC. Multifractal fingerprints in the visual arts. Leonardo (2004) 37:53–6. doi:10.1162/002409404772828139

15. Mureika JR, Dyer CC, Cupchik GC. Multifractal structure in nonrepresentational art. Phys Rev E (2005) 72:046101. doi:10.1103/physreve.72.046101

16. Mureika JR. Fractal dimensions in perceptual color space: a comparison study using Jackson Pollock’s art. Chaos (2005) 15:043702. doi:10.1063/1.2121947

17. Taylor RP. Order in Pollock’s chaos. Scientific Am (2002) 287:116–21. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1202-116

18. Taylor RP, Micolich AP, Jonas D. Response to “Fractal Analysis: revisiting Pollock’s Paintings”. Nat Brief Commun Arising (2006) 444:E10–11. doi:10.1038/nature05399

19. Jones-Smith K, Mathur H. Fractal analysis: revisiting Pollock’s paintings. Nat Brief Commun Arising (2006) 444:E9–10. doi:10.1038/nature05398

20. Redies C. A universal model of esthetic perception based on the sensory coding of natural stimuli. Spat Vis (2007) 21:97–117. doi:10.1163/156856807782753886

21. Redies C, Hasenstein J, Denzler J. Fractal-like image statistics in visual art: similar to natural scenes. Spat Vis (2007) 21:137–48. doi:10.1163/156856807782753921

22. Graham DJ, Field DJ. Statistical regularities of art images and natural scenes: Spectra, sparseness and non-linearities. J Spat Vis (2007) 21:149–64. doi:10.1163/156856807782753877

23. Lee S, Olsen S, Gooch B. Simulating and analysing Jackson Pollock's paintings. J Mathematics Arts (2007) 1:73–83. doi:10.1080/17513470701451253

24. Cernuschi C, Herczynski A, Martin D. Abstract expressionism and fractal geometry. In: E Landau E, and C Cernuschi, editors. Pollock matters. Boston: McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College (2007). p. 91–104.

25. Coddington J, Elton J, Rockmore D, Wang Y. Multi-fractal analysis and authentication of Jackson Pollock paintings. Proc SPIE (2008) 6810:68100F. doi:10.1117/12.765015

26. Graham DJ, Field DJ. Variations in intensity for representative and abstract art, and for art from eastern and Western hemispheres. Perception (2008) 37:1341–52. doi:10.1068/p5971

27. Alvarez-Ramirez J, Ibarra-Valdez C, Rodriguez E, Dagdug L. 1/f-Noise structure in pollock’s drip paintings. Physica A (2008) 387:281–95. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2007.08.047

28. Alvarez-Ramirez J, Echeverria JC, Rodriguez E. Performance of a high-dimensional R/S analyis method for hurst exponent estimation. Physica A (2008) 387:6452–62. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2008.08.014

29. Mohammad I, Stork DG. Multiple visual features for the computer authentication of Jackson Pollock's drip paintings: beyond box counting and fractals. In: Proc. SPIE 7251, image processing: machine vision applications II (2009). p. 72510Q.

32. Shamir L. What makes a Pollock Pollock: a machine vision approach. Int J Arts Technol (2015) 8(1):1. doi:10.1504/ijart.2015.067389

33. Shamir L, Nissel J, Winner E. Distinguishing between abstract art by artists vs. children and animals: comparison between human and machine perception. ACM Trans Appl Perception (2016) 13(3):1–17. doi:10.1145/2912125

34. Smith JH, Holt C, Smith NH, Taylor RP. Using machine learning to distinguish between authentic and imitation Jackson Pollock poured paintings: a tile-driven approach to computer vision. PLOS One (2024) 19(6):e0302962. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0302962

35. Swartz A, Skelton AE, Mather G, Bosten JM, Maule J, Franklin A. The perceived beauty of art is not strongly calibrated to the statistical regularities of real-world scenes. Scientific Rep (2024) 14:19368. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69689-6

36. Quan Y, Xu Y, Sun Y, Luo Y. Lacunarity analysis on image patterns for texture classification. In: IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (2014). p. 161–7. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2014.28

37. Myint SW, Lam N. Examining lacunarity approaches in comparison with fractal and spatial autocorrelation techniques for urban planning. Photogrammetric Eng Sensing (2005) 71(8):927–37. doi:10.14358/PERS.71.8.927

38. Allain C, Cloitre M. Characterizing the lacunarity of random and deterministic fractal sets. Phys Rev A (1991) 44(6):3552–8. doi:10.1103/physreva.44.3552

39. Plotnick RE, Gardner RH, O’Neill RV. Lacunarity indices as a measure of landscape texture. Landscape Ecol (1993) 8(3):201–11. doi:10.1007/BF00125351

40. Scott R, Kadum H, Salmaso G, Calaf M, Cal R. A lacunarity-based index for spatial heterogeneity. Earth Space Sci (2002) 9:e2021EA002180. doi:10.1029/2021ea002180

41. Dougherty G, Henebry G. Lacunarity analysis of spatial pattern in CT images of vertebral trabecular bone for assessing osteoporosis. Med Eng Phys (2002) 24(2):129–38. doi:10.1016/s1350-4533(01)00106-0

42. Labini FS, Montuori M, Pietronero L. Scale invariance of galaxy clustering. Phys Rep (1998) 293(2-4):61–226. doi:10.1016/s0370-1573(97)00044-6

43. Mureika JR, Dyer CC. Multifractal analysis of packed Swiss cheese cosmologies. Gen Relativity Gravitation (2004) 36(1):151–84. doi:10.1023/B:GERG.0000006699.45969.49

44. Yamada N. Chaotic swaying of the upright posture. Hum Mov Sci (1995) 14:711–26. doi:10.1016/0167-9457(95)00032-1

45. Manabe Y, Honda E, Shiro Y, Kenichi K, Kohira I, Kashihara K, et al. Fractal dimension analysis of static stabilometry in Parkinson's disease and spinocerebellar ataxia. Neurol Res (2001) 23:397–404. doi:10.1179/016164101101198613

46. Doyle TLA, Dugan EL, Humphries B, Newton RU. Discriminating between elderly and young using a fractal dimension analysis of centre of pressure. Int J Med Sci (2004) 1:11–20. doi:10.7150/ijms.1.11

47. Harbourne RT, Stergiou N. Nonlinear analysis of the development of sitting postural control. Dev Psychobiol (2003) 42(4):368–77. doi:10.1002/dev.10110

48. Blaszczyk JW, Klonowski W. Postural stability and fractal dynamics. Acta Neuro Exp (2001) 61:105–12. doi:10.55782/ane-2001-1390

49. Kelty-Stephen DG, Furmanek MP, Mangalam M. Multifractality distinguishes reactive from proactive cascades in postural control. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals (2021) 142:110471. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110471

50. Kelty-Stephen DG, Furmanek MP, Mangalam M. Hypothetical control of postural sway. J R Soc Interf (2021) 18:20200951. doi:10.1098/rsif.2020.0951

51. Stambolieva K. Fractal properties of postural sway during quiet stance with changed visual and proprioceptive inputs. J Physiol Sci (2011) 61(2):123–30. doi:10.1007/s12576-010-0129-4

52. Kuznetsov N, Bonnette S, Gao J, Riley MA. Adaptive fractal analysis reveals limits to fractal scaling in center of pressure trajectories. Ann Biomed Eng (2013) 41(8):1646–60. doi:10.1007/s10439-012-0646-9

53. Deffeyes JE, Kochi N, Harbourne RT, Kyvelidou A, Stuberg WA, Stergiou N. Nonlinear detrended fluctuation analysis of sitting center-of-pressure data as an early measure of motor development pathology in infants. Nonlinear Dyn Psychol Life Sci. (2009) 13(4):351–68. Available online at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19781135/.

54. Di MR, Rubega M, Antonini A, Formaggio E, Masiero S, Del Felice A. Fractal analysis of lower back acceleration profiles in balance tasks. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biolsco (2021) 7381–4. doi:10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9629870

55. Sabar R, Rostafa M, Ramezani A, Tanbakoosaz A. Postural control assessment in wushu using fractal dimension analysis. Proc 21st Iranian Conf Biomed Eng (Icbme) IEEE (2014). doi:10.1109/ICBME.2014.7043945

56. Amoud H, Abadi M, Hewson D, Michel-Pellegrino V, Doussot M, Duchêne J. Fractal time series analysis of postural stability in elderly and control subjects. J Neuroengineering Rehabil (2007) 4:12. doi:10.1186/1743-0003-4-12

57. Hausdorff JM, Purdon PL, Peng CK, Ladin Z, Wei JY, Goldberger AL. Fractal dynamics of human gait: stability of long-range correlation in stride interval fluctuations. J Appl Physiol (1996) 80(5):1448–57. doi:10.1152/jappl.1996.80.5.1448

58. Roach S, Boydston C, Taylor RP, inventors; Project Dasein LLC, assignee. Machine Learning and Fractal Analysis Process for Classifying Motion. United States Patent 11733781 (2023).

59. Kodama K, Yamagiwa H, Yasuda K. Fractal dynamics in a whole-body dynamic balance sport, slacklining: a comparison of novices and experts. Non-linear Dyn Psychol Life Sci. (2023) 27(1):15–28.

60. Pálya Z, Kiss RM. Comprehensive linear and nonlinear analysis of the effects of spinning on dynamic balancing ability in Hungarian folk dancers. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil (2024) 16(1):57. doi:10.1186/s13102-024-00850-4

61. Coubard OA, Ferrufino L, Nonaka T, Zelada O, Bril B, Dietrich G. One month of contemporary dance modulates fractal posture in aging. Front Aging Neurosci (2014) 6:17. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00017

63. Hawley-Dolan A, Winner E. Seeing the mind behind the art: people can distinguish abstract expressionist paintings from highly similar paintings by children, chimps, monkeys, and elephants. Psychol Sci (2011) 22(4):435–41. doi:10.1177/0956797611400915

64. Hawley-Dolan A, Winner E. Can young children distinguish abstract expressionist art from superficially similar works by preschoolers and animals? J Cogn Development (2016) 17(1):18–29. doi:10.1080/15248372.2015.1014488

65. Herczynski A, Cernuschi C, Mahadevan L. Painting with drops, jets, and sheets. Phys Today (2011) 64:31–6. doi:10.1063/1.3603916

66. Palacios B, Rosario A, Wilhelmus MM, Zetina S, Zenit R. Pollock avoided hydrodynamic instabilities to paint with his dripping technique. PLOS ONE (2019) 14(10):e0223706. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223706

67. Spehar B, Clifford CWG, Newell BR, Taylor RP. Universal aesthetic of fractals. Computer Graphics (2003) 27(5):813–20. doi:10.1016/s0097-8493(03)00154-7

68. Taylor RP. The potential of biophilic fractal designs to promote health and performance: a review of experiments and applications. Sustainability (2021) 13(2):823. doi:10.3390/su13020823

70. Hentschel HGE, Procaccia I. The infinite number of generalized dimensions of fractals and strange attractors. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena (1983) 8(3):435–44. doi:10.1016/0167-2789(83)90235-x

71. Avnir D, Biham O, Lidar D, Malcai O. Is the geometry of Nature fractal? Science (1998) 279(5347):39–40. doi:10.1126/science.279.5347.39

72. Rival C, Ceyte H, Olivier I. Developmental changes of static standing balance in children. Neurosci Lett (2005) 376(2):133–6. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.042

73. Ferber-Viart C, Ionescu E, Morlet T, Froehlich P, Dubreuil C. Balance in healthy individuals assessed with equitest: maturation and normative data for children and young adults. Int J Pediatr Otothinolaryngology (2007) 71(7):1041–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.03.012

74. Godoi D, Barela JA. Body sway and sensory motor coupling adaptation in children: effects of distance manipulation. Developmental Psychobiology (2008) 50(1):77–87. doi:10.1002/dev.20272

75. Greffou S, Bertone A, Hanssens JM, Faubert J. Development of visually driven postural reactivity: a fully immersive virtual reality study. J Vis (2008) 8(11):15. doi:10.1167/8.11.15

76. Forssberg H, Nashner LM. Ontogenetic development of postural control in man-adaptation to altered support and visual conditions during stance. J Neurosci (1982) 2(5):545–52. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.02-05-00545.1982

77. Wann JP, Mon-Williams M, Rushton K. Postural control and coordination disorders: the swinging room revisited. Hum Movement Sci (1998) 17(4-5):491–513. doi:10.1016/s0167-9457(98)00011-6

78. Cherng RJ, Chen JJ, Su FC. Vestibular system in performance of children and young adults under altered sensory conditions. Perceptual Mot Skills (2001) 92(3):1167–79. doi:10.2466/pms.92.3.1167-1179

79. Barela JA, Jeka JJ, Clark JE. Postural control in children-coupling to dynamic somatosensory information. Exp Brain Res (2003) 150(4):434–42. doi:10.1007/s00221-003-1441-5

80. Baumberger B, Isableu B, Fluckiger M. The visual control of stability in children and adults: postural readjustments in a ground optical flow. Exp Brain Res (2004) 159(1):33–46. doi:10.1007/s00221-004-1930-1

81. Sparto PJ, Redfern MS, Jasko JG, Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Furman JM. The influence of dynamic visual cues for postural control in children aged 7-12 years. Exp Brain Res (2006) 168(4):505–16. doi:10.1007/s00221-005-0109-8

82. Bair WN, Kiemel T, Jeka JJ, Clark JE. Development of multisensory reweighting for posture control in children. Exp Brain Res (2007) 183(4):435–46. doi:10.1007/s00221-007-1057-2

83. Sundermier L, Woollacott M, Roncesvalles N, Jensen J. The development of balance control in children: comparisons of EMG and kinetic variables and chronological and developmental groupings. Exp Brain Res (2001) 136(3):340–50. doi:10.1007/s002210000579

84. Roncesvalles MNC, Woollacott MH, Jensen JL. Development of lower extremity kinetics for balance control in infants and young children. J Mot Behav (2001) 33(2):180–92. doi:10.1080/00222890109603149

85. Figura F, Cama G, Capranica L, Guidetti L, Pulejo C. Assessment of static balance in children. J Sports Med Phys Fitness (1991) 31(2):235–42.

86. Riach CL, Starkes JL. Velocity of centre of pressure excursions as an indicator of postural control systems in children. Gait and Posture (1994) 2(3):167–72. doi:10.1016/0966-6362(94)90004-3

87. Newell KM, Slobounov SM, Slobounova BS, Molenaar PCM. Short-term non-stationarity and the development of postural control. Gait and Posture (1997) 6(1):56–62. doi:10.1016/s0966-6362(96)01103-4

88. Kirshenbaum N, Riach CL, Starkes JL. Non-linear development of postural control and strategy use in young children: a longitudinal study. Exp Brain Res (2001) 140(4):420–31. doi:10.1007/s002210100835

89. Riach CL, Starkes JL. Stability limits of quiet standing postural control in children and adults. Gait and Posture (1993) 1(2):105–11. doi:10.1016/0966-6362(93)90021-r

90. Assaiante C, Amblard B. An ontogenetic model for the sensorimotor organization of balance control in humans. Hum Movement Sci (1995) 14(1):13–43. doi:10.1016/0167-9457(94)00048-j

91. Hay L, Redon C. Feedforward versus feedback control in children and adults subjected to a postural disturbance. Exp Brain Res (1999) 125(2):153–62. doi:10.1007/s002210050670

92. Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Sparto PJ, Redfern MS, Furman JM. Contribution of vision to balance in children four to eight years of age. Ann Otology Rhinology Laryngol (2007) 116(9):653–7. doi:10.1177/000348940711600905

93. Olivier I, Palluel E, Nougier V. Effects of attentional focus on postural sway in children and adults. Exp Brain Res (2008) 185(2):341–5. doi:10.1007/s00221-008-1271-6

94. Klevberg GL, Anderson DI. Visual and haptic perception of postural affordances in children and adults. Hum Movement Sci (2002) 21(2):169–86. doi:10.1016/s0167-9457(02)00100-8

95. Hay L. Spatial-temporal analysis of movements in children: motor programs versus feedback in the development of reaching. J Mot Behav (1979) 11(3):189–200. doi:10.1080/00222895.1979.10735187

96. Saavedra S, Woollacott M, van Donkelaar P. Effects of postural support on eye hand interactions across development. Exp Brain Res (2007) 180(3):557–67. doi:10.1007/s00221-007-0874-7