- 1Department of Science, Eurasian Technological University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

- 2Faculty of Physics and Technology, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, Kazakhstan

The total cross-section of the radiative neutron capture reaction 14С(n,γ0+1)15C—for energies ranging from 10 meV to 5 MeV—is considered. Calculations performed in the framework of the modified potential cluster model with forbidden states show an agreement of total cross-section σ (23.3 keV) = 4.75 μb with the presently recommended value 4.86(48) μb by Ma et al., 2020. The efficiency of carbon isotope 15C production is illustrated by the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction rate calculated at temperatures from T9 = 0.001 to T9 = 10. The conventional Maxwell–Boltzmann weighted reaction rate

1 Introduction

The role of carbon isotope 14С in the stellar environment of asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars was examined nearly 30 years ago by Forestini and Charbonnel, 1997, as part of research concerning the nucleosynthesis of light elements in low-metallicity intermediate-mass stars of

The results of [1] are presented as an estimation of isotope abundance in carbon pockets:

These numbers turned out to be reference values, to some extent, for subsequent studies of AGB stars. Some original papers and reviews provide observables for the 12C/13C and 14N/15N ratios in AGB stars [3–6]. Note that ratios in Equation 1 strongly depend on the mutually connected reaction chains, such as neutron-induced reactions

where the evolution of carbon isotopes 12-15C occurs, and finally nitrogen 15N is created. Hydrogen burning, 12-14C(p,γ)13-15N, is the source of nitrogen isotopes, providing the 14N/15N ratio while also regulating the carbon fractions. We are not concerned with the mechanism of 4He combustion since it mainly relates to the outer helium shell of AGB stars, which is beyond the scope of the present work.

We intend to discuss [5], purposely, the situation with the radiative neutron capture reaction 14С(n,γ)15C in the context of the following questions:

i. how reliable is the reaction rate determined today?;

ii. how may modern data on the reaction rate change the isotopic ratio (Equation 1)?;

iii. are there any reasons to shift from the traditional Maxwell–Boltzmann (MB) weighted reaction rate to non-extensive statistics?

While calculating the ratios (Equation 1), Forestini and Charbonnel, 1997 [1], used as input information for the constructed network the rate of the 14С(n,γ)15C reaction obtained in [7], which was nearly a factor of 5 lower than that of the earlier calculations in [8]. As a result, it was concluded that the reaction 14С(n,γ)15C(β−)15N plays an insignificant role in the formation of 15N, with the process of radiative capture of protons 14С(p,γ)15N dominating.

This “factor of 5 difference” triggered, to some extent, the following year’s experimental study of the cross section of 14С(n,γ)15C reaction [9–12]. The value of the total cross section σ(E) at

To determine the consistency of the results on the MB-weighted rate of the 14С(n,γ)15C reaction, we use data from [7, 8, 11, 18, 19] along with the present model calculations to address question (i). Since we employed the modified potential cluster model (MPCM) (see, for details, [21, 22]), the comparison of rates for the neutron-induced reactions 12-14С(n,γ)13-15C calculated within the same framework provides a way to re-estimate the 13C/14C ratio (ii).

Question (iii) is a new issue in the study of the 14С(n,γ)15C reaction. The subject of non-equilibrium phenomena in the context of stars is related to the application of non-extensive Tsallis statistics, as suggested in [23]. For the first time, [24] (final version, 2017 [25]), pointed out the strong sensitivity of thermonuclear reaction rates of light nuclei during Big Bang nucleosynthesis to the non-extensive parameter q. Further investigations concern the effect of Tsallis statistics on primordial BBN in the context of addressing the lithium problem [26, 27]. A summary of the research [24, 25] suggested extending the study of non-extensive effects to the formation of nuclei with masses beyond the BB seeds, i.e., with

2 Elements of MPCM input data for the 14C(n,γ0+1)15C reaction

The details of the study of the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction in the framework of the MPCM are presented in [28]. In this study, we still consider radiative E1 neutron capture on 14С, scattering p-waves to the ground state (GS) and first excited state (1st ES) of 15C, with respective quantum numbers

where V0 is the potential depth and α is a parameter defining the asymptotic decrease in the potential at long relative distances r. Parameters V0 and α in Equation 3 are fitted for the bound states so that they match the channel binding energy Еb, charge radius Rch, and matter radius Rm. A set of parameters is found for each partial wave with quantum numbers JLS. The nodal or nodeless r-dependence of the relative wave functions is determined by the classification of orbital symmetry using Young diagrams, as implemented for the

Another experimental characteristic is the asymptotic normalization coefficient

Table 1. Parameters of the ground and excited state potential for 15C nucleus in the n14C channel and results of MPCM calculations of Еb, Rch, Rm, and Cw with the listed parameters V0 and α.

To calculate Rch(15C) and Rm(15C), we follow the definitions from [21]. The input numerical information includes the masses of the constituent particles, mn = 1.008665 amu and

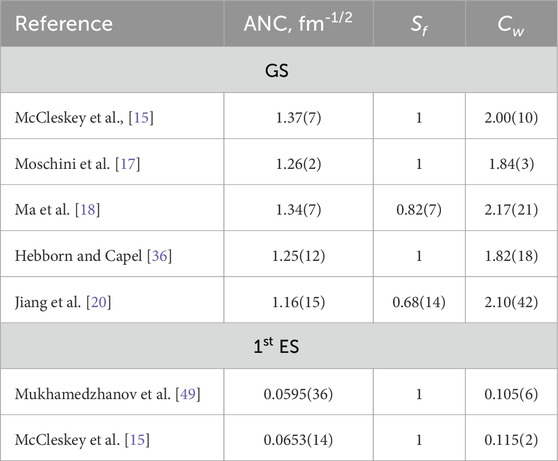

The results for Cw in Table 1 were obtained over the interval 7–27 fm. Selected later data on the ANC and their recalculated values for Cw, presented in Table 3, show reasonable agreement with the MPCM results for the GS, as well as for the first excited state.

Initially, we proceeded from the data in work [37], where for the resonant states 2P1/2 at 3.103 MeV and 2P3/2 at 4.657 MeV, the reaction 14С(n,γ)15C does not occur, which means that these states are excited or formed in stripping or pickup reactions. In some studies, the narrow resonance at 3.103 MeV (Гn = 42 keV) is included in 14С(n,γ)15C cross-section calculations as a Breit–Wigner resonance; for example, see recent references [18, 20]. Their estimates show that its contribution is very small, even compared to the capture to the first excited state.

In the present study, we assume the 2P1/2 and 2P3/2 states to be non-resonant in the n + 14C channel. Since in the MPCM, the partial 2P waves do not contain forbidden states [22, 28], which are present in the spectrum of solutions of the Schrödinger equation only as bound states and require sufficiently deep attractive potentials [21], we assume the corresponding potentials to be zero.

Our choice of the zero depth for the P-wave scattering interaction potentials is supported by Ref. [16], where the role of different interaction parameters sets in the continuum

3 Total cross sections of the n14C capture reaction

Comparison of the total cross sections for the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction, calculated using the MPCM potential parameters from Table 1, with experimental data is presented in Figure 1a. It is clearly observed that there is a noticeable input from the (n,γ1) capture to the first ES starting from energies

Figure 1. Total cross sections of the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction. Experiment:

Note that the data by [12] are the result of a recalculation of the Coulomb breakup of 15C and corresponds to the photodisintegration reaction

Figure 1b illustrates the total cross sections for Ec.m. shows the results from our earlier work [28]. These cross sections are somewhat lower than the present cross sections since in [28], the radial matrix elements for the cross sections were calculated only up to 30 fm. Based on the low binding energy

The energy dependence of σ(Ec.m.) at

The constant A = 1.002 μb·keV-1/2 in equation 4 is determined from a single point of

The thermal cross section is too small to be measured; therefore, the available experimental value of

Figure 2 shows the neutron capture cross section divided by E1/2, i.e.,

Figure 2. Total cross sections of the radiative n14С capture divided by E1/2. The inset shows the comparison of the theoretical calculations of [13, 18] and the MPCM results.

4 14C(n,γ0+1)15C reaction rate

The astrophysical rate of the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction, calculated in MPCM, is shown in Figure 3. We approximated the MPCM reaction rates using an expression of the form

Figure 3. Rate of the 14C(n,γ)15C reaction. MPCM reaction rates: red solid curve, –GS + first ES; blue dashed curve, GS. Inset: comparison of the reaction rates from [18] (dot magenta curve), [11] (dash-dot-dot blue curve), and [19] (dash-dot black curve) normalized to the MPCM rate.

Corresponding parameters ai for the GS and total reaction rates are provided in Table 5 according (Equation 5). The approximation yields χ2 = 0.0005 and χ2 = 0.0006, respectively, with an accuracy of 5% for the calculated reaction rates.

Table 5. Reaction rate approximation parameters for (Equation 5).

The inset in Figure 3 shows a comparison of present results and reaction rates calculated by [11], [18], and [19] normalized to the rate of the present work. The rate [18] based on the ANC formalism in the interval

In Figure 3, we do not present the results from [20] directly, but we compare our reaction rate with the tabulated data of [20]. The authors note that their rate is ∼25% lower than that provided in [11] and ∼2.5–4 times higher than that provided in [7]. Comparison with our rate shows that our data exceeds the rate from [20] by a factor of 1.20. We may conclude that our results are more consistent with those reported in [11, 18, 19].

5 12-14C(n,γ)13-15C reaction rates and 12C/13C and 13C/14C ratios

Answer to question (i): The MPCM passed the cross-check; therefore, reliable data on the rate of the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction may be considered well determined today within ∼10% accuracy. This conclusion allows us to discuss possible corrections to the isotopic ratios 12C/13C, 13C/14C, and 14N/15N, following sequence 2 by comparing the early values from Ref. [1] (Equation 1) and addressing question (ii). The first observation concerns the near factor-of-5 difference in the reaction rates reported by [7] and [8], as shown in Figure 4. This difference changes the ratio

Further changes in isotopic ratios may come from the results on reaction rates of the radiative neutron capture on carbon isotopes 12C(n,γ)13C [38] 13C(n,γ)14C [39], and 14C(n,γ)15C (present work) calculated in the same model—MPCM. These rates are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Comparison of the astrophysical 12C(n,γ0+1+2+3)13C [38], 13C(n,γ0+1+2)14C [39], and 14C(n,γ0+1)15C reaction rates in the range T9 = 0.01–10. Colored areas correspond to the interchange of the reaction rates (see comments in text).

Radiative neutron capture reactions may change the balance of 13C/14C as the ratio of reaction rates

Comparison of 13C(n,γ0+1+2)14C and 14C(n,γ0+1)15C rates in Figure 5 shows the temperature intervals where slow production of 15C exceeds the creation of 14C. The low energy interval is T9 = 0.1–0.2, which refers to the equality of the corresponding reaction rates

The production of 14С in low-metallicity AGB stars is provided by two reactions: 13C(n,γ)14С and 14N(n,p)14C [40, 41]. Measurements by Wallner et al. [41] reported cross section at 23.3 keV

In simpler terms, the ratio of these two reactions 13C(n,γ)14С and 14N(n,p)14C is approximately two orders of magnitude. Hence, the relative concentrations of accumulated nuclei 13C and 14N set the balance between these two reactions, which provides the abundance of 14C sufficient for a change in the elemental content of carbon pockets. Reaction 14N(n,p)14C changes the ratio 14N/15N, and at the same time, this ratio may be affected by increasing the number of 15N via the reaction

6 Rate of the 14C(n,γ0)15C reaction with Tsallis statistics

It has been established that thermal pulses arise during the evolution of AGB stars and lead to temperature and density fluctuations in the convective envelope, which can locally disrupt the equilibrium particles’ velocity distribution [1, 2]. The Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution may also be violated due to turbulence and sudden energetic events, such as helium and hydrogen flashes. This provides the motivation for applying Tsallis statistics [23–25], κ-distributions [43–45], and superstatistics [46] when calculating nuclear reaction rates in AGB models.

The application of Tsallis statistics is our first step toward examining non-extensive effects in stellar plasma, for example, the 14С(n,γ0)15C reaction, which may be incorporated into the analysis of the processes occurring in the carbon pockets of AGB stars [1, 4, 6]. The reason for applying Tsallis statistics concerns several aspects. The interpretation of non-extensive parameter q in the velocity distribution fq(v) is quite straightforward; i.e., in case, q > 1, the Maxwell–Boltzmann fMB(v) symmetric distribution is violated due to a damping in the number of particles with high energies, whereas case q < 1 implies an enhancement in the low energy component in the fq(v) distribution compared to the fMB(v). We also find that the Tsallis formalism is rather simple in application for calculating reaction rate integrals as it allows for convergent control of the results to those of the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution.

Following [24] and [25], we recalculated the rate of the 14С(n,γ)15C reaction simulating the non-extensive effect of Tsallis statistics versus the Maxwell–Boltzmann by changing the velocity distribution from fMB(v) to fq(v). Explicit expressions and normalizing conditions for the velocity distributions of non-relativistic particles with an energy

Note that

In the case of

The integral over the Maxwellian-weighted cross section (Equation 6) determines the reaction rate, which was derived in detail by Iliadis and is provided in a general form [47]:

In the case of Tsallis statistics and following definition for fq(v) distribution (Equation 7), Equation 11 can be transformed to

In Figure 6 the results of the calculated

Figure 6. Reaction rates calculated for the Tsallis statistics:

Figure 7 shows the numerical difference in reaction rates, considering the effect of the non-equilibrium Tsallis distribution compared to the MB distribution for

In [20] Jiang et al., implemented the calculated 14С(n,γ)15C reaction rate

Note that we have implemented a simplified calculation procedure, assuming that the effect of the center-of-mass correction, introduced by [26, 27], is not essential, as the seed nucleus 14C is much heavier than the light species with comparable masses involved at the stage of primordial BBN.

7 Conclusion

In summary, we show that the MPCM results on 14С(n,γ0+1)15C are in good agreement with those reported in [18, 19]. Benchmark cross section

The obtained values of reaction rates can be confidently conceived as the reference ones for the re-estimation of 12C/13C, 13C/14C, and 14N/15N via the neutron-induced reactions 12C(n,γ0+1+2+3)13C, 13C(n,γ0+1+2)14C, and 14C(n,γ0+1)15C calculated in MPCM. We determined the temperature windows where the interchange of reaction rates is observed:

Here, in order to finalize the values of isotopic ratios, it is reasonable to consider the reaction rates 12-14C(n,γ)13-15C together with the proton-induced reactions 12-14C(p,γ)13-15N calculated in the same model. We took a step forward toward this goal by calculating the MPCM rate for the 12C(p,γ)13N reaction [48].

The Tsallis statistics allow one to vary the numerical values of the 14С(n,γ0+1)15C reaction rate, as illustrated in the present calculations for the range of the non-extensive parameter

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

AT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. NB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. BY: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. SD: Software, Validation, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. AP19676483).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Forestini M, Charbonnel C. Nucleosynthesis of light elements inside thermally pulsing AGB stars. Astron Astrophys Suppl Ser (1997) 123:241–72. doi:10.1051/aas:1997348

2. Forestini M, Guelin M, Cernicharo J. 14C in AGB stars: the case of IRC+10216. Astron Astrophys (1997) 317:883–8.

3. Karakas AI, Lattanzio JC. The dawes review 2: nucleosynthesis and stellar yields of Low- and intermediate-mass single stars. Publ Astron Soc Aust 31:e030. (2014) doi:10.1017/pasa.2014.21

4. Palmerini S, Busso M, Vescovi D, Naselli E, Pidatella A, Mucciola R, et al. Presolar grain isotopic ratios as constraints to nuclear and stellar parameters of asymptotic giant branch star nucleosynthesis. Astrophys J (2021) 921:7. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac1786

5. Herwig F. Evolution of asymptotic giant branch stars. Annu Rev Astron Astrophys (2005) 43:435–79. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.43.072103.150600

6. Choplin A, Siess L, Goriely S. Proton ingestion in asymptotic giant branch stars as a possible explanation for J-type stars and AB2 grains. Astron Astrophys (2024) 691:L7. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202451013

7. Beer H, Wiescher M, Kaeppeler F, Goerres J, Koehler PE. A measurement of the C-14(n, gamma)C-15 cross section at a stellar temperature of kT = 23.3 keV. Astrophys J (1992) 387:258. doi:10.1086/171077

8. Wiescher M, Gorres J, Thielemann F-K. Capture reactions on C-14 in nonstandard big bang nucleosynthesis. Astrophys J (1990) 363:340. doi:10.1086/169348

9. Horvath A, Weiner J, Galonsky A, Deak F, Higurashi Y, Ieki K, et al. Cross section for the astrophysical 14C(n,γ)15C reaction via the inverse reaction. Astrophys J (2002) 570:926–33. doi:10.1086/339726

10. Reifarth R, Heil M, Plag R, Besserer U, Dababneh S, Dörr L, et al. Stellar neutron capture rates of 14C. Nucl Phys A (2005) 758:787–90. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.05.141

11. Reifarth R, Heil M, Forssén C, Besserer U, Couture A, Dababneh S, et al. The 14C(n,γ) cross section between 10 keV and 1 MeV. Phys Rev C (2008) 77:015804. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.77.015804

12. Nakamura T, Fukuda N, Aoi N, Imai N, Ishihara M, Iwasaki H, et al. Neutron capture cross section of 14C of astrophysical interest studied by coulomb breakup of 15C. Phys Rev C (2009) 79:035805. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.79.035805

13. Timofeyuk NK, Baye D, Descouvemont P, Kamouni R, Thompson IJ. 15C−15F charge symmetry and the 14C(n,γ)15C reaction puzzle. Phys Rev Lett (2006) 96:162501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.162501

14. Summers NC, Nunes FM. Extracting (n,γ) direct capture cross sections from coulomb dissociation: application to 14C(n,γ)15C. Phys Rev C (2008) 78:011601. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.78.011601

15. McCleskey M, Mukhamedzhanov AM, Trache L, Tribble RE, Banu A, Eremenko V, et al. Determination of the asymptotic normalization coefficients for 14C + n ↔ 15C, the 14C(n,γ)15C reaction rate, and evaluation of a new method to determine spectroscopic factors. Phys Rev C (2014) 89:044605. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.89.044605

16. Capel P, Nollet Y. Reconciling coulomb breakup and neutron radiative capture. Phys Rev C (2017) 96:015801. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.96.015801

17. Moschini L, Yang J, Capel P. 15C: from halo effective field theory structure to the study of transfer, breakup, and radiative-capture reactions. Phys Rev C (2019) 100:044615. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.100.044615

18. Ma T, Guo B, Pang D, Li Z, Su Y, Li X, et al. New determination of astrophysical 14C(n, γ)15C reaction rate from the spectroscopic factor of 15C. Sci China Phys Mech Astron (2020) 63:212021. doi:10.1007/s11433-019-9411-2

19. Bhattacharyya A, Datta U, Rahaman A, Chakraborty S, Aumann T, Beceiro-Novo S, et al. Neutron capture cross sections of light neutron-rich nuclei relevant for r-process nucleosynthesis. Phys Rev C (2021) 104:045801. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.104.045801

20. Jiang Y, He Z, Luo Y, Xin W, Chen J, Li X, et al. New determination of the 14C(n,γ)15C reaction rate and its astrophysical implications. Astrophys J (2025) 989:231. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ade5b3

21. Dubovichenko SB, Uzikov YN. Astrophysical S-factors of reactions with light nuclei. Phys Particles Nuclei (2011) 42:251–301. doi:10.1134/S1063779611020031

22. Dubovichenko SB. Radiative neutron capture: primordial nucleosynthesis of the universe. Berlin: De Gruyter (2019).

23. Tsallis C. Possible generalization of boltzmann-gibbs statistics. J Stat Phys (1988) 52:479–87. doi:10.1007/BF01016429

24. Hou SQ, He JJ, Parikh A, Daid K, Bertulani C. Big-bang nucleosynthesis verifies classical maxwell-boltzmann distribution (2014) Available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1408.4422 (Accessed Feburary 07, 2025).

25. Hou SQ, He JJ, Parikh A, Kahl D, Bertulani CA, Kajino T, et al. Non-extensive statistics to the cosmological lithium problem. Astrophys J (2017) 834:165. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/2/165

26. Kusakabe M, Kajino T, Mathews GJ, Luo Y. On the relative velocity distribution for general statistics and an application to big-bang nucleosynthesis under tsallis statistics. Phys Rev D (2019) 99:043505. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.99.043505

27. Bertulani CA. Shubhchintak. Primordial nucleosynthesis with non-extensive statistics. Eur Phys J Spec Top (2024) 233:2831–42. doi:10.1140/epjs/s11734-024-01216-0

28. Dubovichenko S, Dzhazairov-Kakhramanov A, Afanasyeva N. Radiative neutron capture on 9Be, 14C, 14N, 15N and 16O at thermal and astrophysical energies. Int J Mod Phys E (2013) 22:1350075. doi:10.1142/S0218301313500754

29. Mukhamedzhanov AM, Tribble RE. Connection between asymptotic normalization coefficients, subthreshold bound states, and resonances. Phys Rev C (1999) 59:3418–24. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.59.3418

30. Yamaguchi T, Hachiuma I, Kitagawa A, Namihira K, Sato S, Suzuki T, et al. Scaling of charge-changing interaction cross sections and point-proton radii of neutron-rich carbon isotopes. Phys Rev Lett (2011) 107:032502. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.032502

31. Zhao JW, Sun B-H, Tanihata I, Xu JY, Zhang KY, Prochazka A, et al. Charge radii of 11−16C, 13−17N and 15−18O determined from their charge-changing cross-sections and the mirror-difference charge radii. Phys Lett B (2024) 858:139082. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2024.139082

32. Zhao JW, Sun B-H, Tanihata I, Terashima S, Prochazka A, Xu JY, et al. Isospin-dependence of the charge-changing cross-section shaped by the charged-particle evaporation process. Phys Lett B (2023) 847:138269. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2023.138269

33. Li LY, Tu XL, Zhang JT, Zhang GQ. Nuclear matter distribution radius compilation and evaluation: NMRCE2025. At Data Nucl Data Tables (2025) 166:101747. doi:10.1016/j.adt.2025.101747

34. Kanungo R, Horiuchi W, Hagen G, Jansen GR, Navratil P, Ameil F, et al. Proton distribution radii of 12-19C illuminate features of neutron halos. Phys Rev Lett (2016) 117:102501. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.117.102501

35. Dobrovolsky AV, Korolev GA, Tang S, Alkhazov GD, Colò G, Dillmann I, et al. Nuclear matter distributions in the neutron-rich carbon isotopes 14−17C from intermediate-energy proton elastic scattering in inverse kinematics. Nucl Phys A (2021) 1008:122154. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2021.122154

36. Hebborn C, Capel P. Halo effective field theory analysis of one-neutron knockout reactions of 11Be and 15C. Phys Rev C (2021) 104:024616. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.104.024616

37. Ajzenberg-Selove F. Energy levels of light nuclei A = 13–15. Nucl Phys A (1991) 523:1–196. doi:10.1016/0375-9474(91)90446-D

38. Dubovichenko SB, Burkova NA. Rate of radiative n12C decay at temperatures from 0.01 T9 to 10 T9. Russ Phys J (2021) 64:216–27. doi:10.1007/s11182-021-02319-0

39. Dubovichenko SB. n13C capture reaction rate. Russ Phys J (2022) 65:208–15. doi:10.1007/s11182-022-02624-2

40. Lugaro M, Herwig F, Lattanzio JC, Gallino R, Straniero O. Process nucleosynthesis in asymptotic giant branch stars: a test for stellar evolution. Astrophys J (2003) 586:1305–19. doi:10.1086/367887

41. Wallner A, Bichler M, Buczak K, Dillmann I, Käppeler F, Karakas A, et al. Accelerator mass spectrometry measurements of the 13C(n,γ)14C and 14N(n,p)14C cross sections. Phys Rev C (2016) 93:045803. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.93.045803

42. Torres-Sánchez P, Praena J, Porras I, Sabaté-Gilarte M, Lederer-Woods C, Aberle O, et al. Measurement of the 14N(n,p)14C cross section at the CERN n_TOF facility from subthermal energy to 800 keV. Phys Rev C (2023) 107:064617. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.107.064617

43. Kong H, Xie H, Liu B, Tan M, Luo D, Li Z, et al. Enhancement of fusion reactivity under Non-Maxwellian distributions: effects of drift-ring-beam, slowing-down, and kappa super-thermal distributions. Plasma Phys Control Fusion (2024) 66:015009. doi:10.1088/1361-6587/ad1008

44. Squarer BI, Presilla C, Onofrio R. Enhancement of fusion reactivities using Non-Maxwellian energy distributions. Phys Rev E (2024) 109:025207. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.109.025207

45. Livadiotis G. Kappa distributions: statistical physics and thermodynamics of space and astrophysical plasmas. Universe (2018) 4:144. doi:10.3390/universe4120144

46. Ourabah K. Reaction rates in quasiequilibrium states. Phys Rev E (2025) 111:034115. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.111.034115

47. Iliadis C. Nuclear physics of stars. Second. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH and Co. KGaA (2015).

48. Dubovichenko SB, Burkova NA, Tkachenko AS, Samratova A. Reaction rate of radiative p12C capture in a modified potential cluster model. Chin Phys C (2025) 49:044104. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/ada34d

Keywords: n14C system, radiative capture, thermonuclear reaction rate, potential cluster model, Tsallis statistics

Citation: Tkachenko AS, Burkova NA, Yeleusheva BM and Dubovichenko SB (2025) Estimation of the effect of Tsallis non-extensive statistics on the 14C(n,γ)15C reaction rate. Front. Phys. 13:1688864. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1688864

Received: 19 August 2025; Accepted: 30 September 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Chong Qi, Royal Institute of Technology, SwedenReviewed by:

Danyang Pang, Beihang University, ChinaRuirui Xu, China Institute of Atomic Energy, China

Copyright © 2025 Tkachenko, Burkova, Yeleusheva and Dubovichenko. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: A. S. Tkachenko, dGthY2hlbmtvLmFsZXNzeWFAZ21haWwuY29t

†ORCID: A.S. Tkachenko, orcid.org/0000-0002-9319-0135; N.A. Burkova, orcid.org/0000-0002-3122-1944; B.M. Yeleusheva, orcid.org/0000-0002-8739-1969; S.B. Dubovichenko, orcid.org/0000-0002-7747-3426

A. S. Tkachenko

A. S. Tkachenko N. A. Burkova

N. A. Burkova B. M. Yeleusheva

B. M. Yeleusheva S. B. Dubovichenko

S. B. Dubovichenko