- School of Chemical Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece

Artificial intelligence (AI) is redefining the foundations of scientific software development by turning once-static codes into dynamic, data-dependent systems that require continuous retraining, monitoring, and governance. This article offers a practitioner-oriented synthesis for building reproducible, sustainable, and trustworthy scientific software in the AI era, with a focus on soft matter physics as a demanding yet fertile proving ground. We examine advances in machine-learned interatomic and coarse-grained potentials, differentiable simulation engines, and closed-loop inverse design strategies, emphasizing how these methods transform modeling workflows from exploratory simulations into adaptive, end-to-end pipelines. Drawing from software engineering and MLOps, we outline lifecycle-oriented practices for reproducibility, including containerized environments, declarative workflows, dataset versioning, and model registries with FAIR-compliant metadata. Governance frameworks such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework and the EU AI Act are discussed as critical scaffolding for risk assessment, transparency, and auditability. By integrating these engineering and scientific perspectives, we propose a structured blueprint for AI-driven modeling stacks that can deliver scalable, verifiable, and regulatory-ready scientific results. This work positions soft matter physics not just as a beneficiary of AI but as a key testbed for shaping robust, reproducible, and accountable computational science.

1 Introduction

Scientific software has long been the connective tissue of modern research. It translates physical hypotheses into executable form, generates predictions from theoretical models, and validates them against experimental or observational evidence. Historically, this role has been anchored by deterministic simulation codes, statistical analysis packages, and workflow managers designed to prioritize correctness, reproducibility, and computational efficiency. Yet in the era of Artificial Intelligence (AI), this picture is being redrawn. At the heart of the change is the growing centrality of data-driven components—statistical models, deep neural networks, and increasingly foundation models—that behave not as fixed algorithms but as mutable dependencies. These models are intimately tied to evolving datasets, training regimes, and hardware environments. Unlike classical scientific codes, which can often remain valid for decades once validated, AI-driven models degrade over time as data distributions shift, dependencies evolve, and compute platforms change. This mutability stresses classical abstractions of scientific software engineering and makes end-to-end reproducibility fragile unless it is carefully designed in from the outset.

The stakes are particularly high in soft matter physics. Soft matter encompasses polymers, colloids, gels, surfactants, liquid crystals, and biomolecular assemblies—systems governed by large thermal fluctuations [1–3], long-lived metastability [4–6], and multiscale dynamics [7–9]. Conventional atomistic simulations struggle to capture their vast spatiotemporal span, often requiring millions of atoms over microseconds or longer. Coarse-graining can extend these scales, but at the expense of introducing model uncertainty and transferability challenges [10–14]. Meanwhile, inverse design problems—such as creating molecules, nanoparticles, or assemblies with targeted functionality—demand exploration of rugged energy landscapes through costly iterative search [15–19]. This confluence of challenges makes soft matter physics a particularly demanding domain for simulation, but also one where AI-enabled approaches promise transformative gains.

In recent years, three converging trends have begun to reshape the practice of soft matter modeling and the software stacks that support it. The first is the ability to learn physical models directly from data. Machine learning architectures such as equivariant graph neural networks and message-passing models can learn force fields and coarse-grained interactions with near ab initio accuracy but at the cost of classical molecular dynamics [20–26]. By encoding Euclidean symmetries and, in some cases, long-range physics, these networks respect the fundamental invariances of interatomic interactions [27–30]. Frameworks such as NequIP [31], MACE [32], and Allegro [33] have demonstrated that it is possible to replace hand-crafted potentials with machine-learned surrogates that not only faithfully approximate electronic-structure calculations but also generalize across molecular compositions and thermodynamic states. In the context of soft matter, where transferability is a perpetual challenge, these models open possibilities for constructing coarse-grained descriptions that are physically consistent and data-efficient [34, 35, 82].

The second major trend is the integration of differentiable programming into molecular simulation. Modern toolkits built on JAX or PyTorch, such as JAX-MD [36] and TorchMD [37], expose forces, trajectories, and even loss functions to automatic differentiation [38]. This enables gradient-based optimization across the entire simulation pipeline, turning molecular dynamics into a differentiable layer within larger computational graphs. Such capabilities permit direct parameter learning against experimental observables, efficient sensitivity analysis of dynamic processes, and inverse design workflows in which system parameters are tuned to optimize emergent material properties [38–40]. Differentiable simulation blurs the line between physical modeling and optimization, embedding traditional simulation within the broader ecosystem of differentiable scientific computing.

A third development is the arrival of AI-native software practices into physics laboratories. Research software is increasingly designed around principles drawn from modern machine learning operations, including continuous integration of models and data, automated experiment tracking, and infrastructure for reproducibility. The FAIR for Research Software principles [41] extends the widely adopted FAIR framework—findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable—from data to code, recognizing that software is not merely auxiliary to science but a primary research object [42, 43]. Alongside this, practices from industry such as Machine Learning Operations (MLOps) [44–46] are being adapted to manage the lifecycle of scientific machine learning models. Versioning, experiment logging, retraining pipelines, and monitoring of model drift are now entering the practice of computational physics [47–49]. Large language models further complicate and enrich this picture, as they increasingly assist with code authoring, testing, and documentation [50–52]. Their integration can enhance productivity but also raises new questions about provenance, correctness, and scientific accountability. Together, these developments accelerate discovery but also foreground challenges of reliability, reproducibility, and validity.

Concerning LLMs, they have begun to play a non-trivial role in scientific code generation, raising a distinct set of challenges that extend beyond mere functionality. For example, provenance questions become acute: when code is scaffolded or entirely generated by an LLM, scholars must ask “Which version of which model contributed?” and “Which training data or prompt context underlies this snippet?” Recent work highlights that standard provenance frameworks often fail to capture agent-centric metadata such as prompts, model version, and contextual lineage [53–55]. Licensing and intellectual-property concerns are also important: LLMs typically draw upon massive corpora of code under heterogeneous licenses, creating ambiguities around downstream reuse, attribution, and derivative work [56–58]. Meanwhile, traceability and version control become more complex when the code evolves through a hybrid human–machine loop: ensuring that subsequent edits, branch merges, and model-assisted contributions remain auditable is non-trivial [53, 59, 60]. Together, these issues emphasize that adopting LLM-generated code in scientific workflows is not just a productivity win, but a shift that demands explicit governance of provenance, licensing, and version-traceability if reproducibility and accountability are to be preserved [55, 61, 62].

These shifts must be understood against the backdrop of a reproducibility crisis [47, 63, 64] that has affected many areas of computational science. The integration of data-driven models introduces new risks that are absent or less pronounced in traditional simulation. Model boundaries [31, 65] are prone to erosion as applications expand beyond the regimes on which training data are drawn. Training and prediction can become entangled with poorly documented datasets, complicating efforts to disentangle provenance and validity [66, 67]. Configurations of hyperparameters, dependencies, and hardware optimizations often accumulate as invisible technical debt, leading to fragility in software reuse [68–70]. Feedback loops can arise when models trained on generated or biased data reinforce their own errors [71–73]. These failure modes are articulated in the influential notion of “hidden technical debt” in machine learning systems, which emphasized the gap between rapid experimental progress and the challenges of long-term maintainability [61, 74]. Unlike classical simulation codes, which once validated can remain useful for decades, AI-driven systems demand constant monitoring, retraining, and governance [68, 70, 75].

In parallel, the reproducibility movement has articulated frameworks to address these risks. The FAIR principles originally applied to data have been extended to research software, emphasizing that both code and models must be findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable [41, 66]. Communities such as computational biology and software carpentry have emphasized pragmatic rules for sustainable research coding, from documenting provenance to versioning code and data together [42, 48, 49, 76]. These community-driven initiatives demonstrate that reproducibility is not an optional add-on but an essential element of credible scientific practice [63, 77, 78]. Yet AI intensifies the challenge by multiplying the number of mutable dependencies and by entangling software, data, and hardware in ways that make reproducibility nontrivial [47, 67, 79].

Soft matter physics provides a compelling proving ground for tackling these challenges. The field is inherently multiscale, spanning length scales from angstroms to microns and time scales from femtoseconds to seconds [11, 12, 80]. Bridging these scales has always required hybrid methods, combining atomistic, coarse-grained, and continuum representations [80]. AI-enabled approaches promise to unify these levels through learned surrogates and differentiable couplings, offering a route to predictive models that maintain fidelity across scales [32, 81, 82]. The rugged free-energy landscapes [83] that characterize soft matter pose another challenge, as metastability and rare events dominate system behavior [84, 85]. Traditional simulation methods struggle to sample these efficiently [86], but AI-assisted sampling and generative models offer new ways to accelerate exploration. Moreover, many problems in soft matter are inherently inverse: designing polymers for mechanical resilience, nanoparticles for drug delivery, or surfactants for targeted self-assembly all require forward modeling of emergent structures and inverse optimization of component design. These dual demands align closely with the strengths of AI, particularly generative models and gradient-based optimization in high-dimensional spaces. Experimental advances further reinforce this potential, as scattering, microscopy, and single-molecule techniques provide increasingly rich datasets that can inform and validate AI-augmented models [87–96].

Although this work focuses on soft matter systems, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) provides a complementary example of how computational science is being reshaped by AI/ML. Both domains face similar challenges: they require solving nonlinear partial differential equations (Navier–Stokes for fluids, reaction–diffusion or elasticity equations for soft matter) over wide spatiotemporal scales, often under uncertainty. In CFD, machine learning has already shown its potential to accelerate simulations and enable real-time control through physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) [97, 98], neural operators [99], and hybrid turbulence models [100]. These advances demonstrate how embedding physical laws into learning architectures can reduce computational cost, improve generalization, and make design space exploration tractable. The lessons learned from AI-augmented CFD—such as the need for differentiable solvers [101, 102], uncertainty-aware active learning [103], and rigorous reproducibility [104–106]—directly inform the strategies we advocate for soft matter modeling, where similar multiscale and data-efficiency issues arise.

Together, these developments sharpen a central question: what should good scientific software look like in an AI-intensive world? The answer cannot simply be to append machine learning modules to existing codes. Rather, what is needed is a lifecycle-oriented approach that integrates domain-specific modeling with robust engineering practices and governance frameworks. Reproducibility must be embedded by design through containerization, workflow automation, and metadata-rich logging. Models must be continuously validated and retrained as data or conditions shift, requiring infrastructure for continuous integration of simulations with evolving datasets. Choices between atomistic, coarse-grained, and AI-augmented models must be guided not only by accuracy requirements but also by sustainability and interpretability. Governance of both data and models must align with emerging standards such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework [107] and EU Regulation [108], evolving regulatory regimes, ensuring transparency, accountability, and ethical use. Finally, stewardship of scientific software in this new regime must be interdisciplinary, bridging physics, computer science, and data science to ensure both scientific validity and engineering robustness.

The aim of this article is to provide a practitioner-oriented synthesis of these themes. We examine the state of the art in AI-accelerated modeling of soft matter, reviewing developments in machine-learned force fields, differentiable simulation frameworks, and inverse design strategies. We analyze how software engineering practices drawn from MLOps, FAIR4RS (FAIR for Research Software), containerization, and LLM-assisted development can be adapted to scientific contexts. We identify the risks and challenges to reproducibility, maintainability, and governance posed by AI-driven scientific software. From this analysis we propose a set of lifecycle-oriented design principles that integrate modeling needs with reproducibility frameworks and governance standards.

By weaving together these strands, we position soft matter physics not merely as a beneficiary of artificial intelligence but as a proving ground for broader questions of how to build scientific software that is accurate, sustainable, and FAIR in an AI-intensive world.

2 From descriptive to executable knowledge: software as the scientific substrate

Scientific understanding is increasingly embedded in executable artifacts—simulators, learned potentials, analysis notebooks, and automated pipelines—shifting the focus from static publications to dynamic, reproducible workflows [42, 66, 109]. In soft matter, this transition is driven by three core challenges. First, multiscale coupling: soft materials exhibit behavior spanning multiple length and time scales, from molecular interactions to mesoscopic assemblies, necessitating models that propagate information across scales without losing fidelity [80, 110–112]. Second, stochastic dynamics and rare events: phenomena such as nucleation, self-assembly, and folding are dominated by fluctuations, requiring simulation strategies capable of capturing rare but critical events [83, 113, 114]. Third, the richness of design spaces: the combinatorial possibilities of sequences, architectures, and interaction parameters demand tools that can efficiently navigate complex landscapes and identify promising candidates [19, 115, 116].

Modern AI-era software responds to these pressures with a suite of complementary approaches. Composable kernels with automatic differentiation (AD) allow force computations to be fully differentiable, enabling end-to-end optimization against experimental observables or higher-level targets, bridging the gap between local interactions and emergent behaviors [36]. Equivariance by construction, through SO(3) or E (3)-equivariant networks, embeds fundamental rotational and translational symmetries directly into model architectures, enhancing sample efficiency and out-of-distribution robustness, which is critical for predicting novel soft matter configurations [31, 82]. Active learning loops leverage uncertainty-aware sampling to maintain compact yet representative training sets, systematically exploring metastable configurations while capturing rare events efficiently [117–120]. Finally, closed-loop inverse design uses differentiable or surrogate-based objectives to steer simulations toward targeted structures, such as colloidal crystals, block copolymer morphologies, or mesophases, integrating prediction, simulation, and evaluation into a single adaptive workflow [121–123].

In computational fluid dynamics (CFD), analogous challenges arise. Realistic flow problems span wide ranges of length and time scales, often coupling to heat transfer, chemical reactions, or multiphase interfaces. Traditional solvers face steep computational costs due to mesh resolution demands and nonlinearities in the governing Navier–Stokes equations, especially in complex geometries or parameter sweeps. Furthermore, the design spaces in CFD—ranging from aerodynamic shapes to microfluidic architectures—are combinatorially rich, requiring tools that can navigate large parameter landscapes efficiently. Modern AI-driven strategies address these barriers: neural operators [99, 124, 125] and differentiable solvers [126–128] provide fast surrogates for PDE solutions [129], enabling real-time exploration of design spaces while retaining accuracy across varying boundary conditions. Automatic differentiation–enabled CFD kernels [130, 131] allow direct gradient computation through flow simulations, bridging high-fidelity physics with optimization and inverse design objectives. Active learning frameworks [132–134] selectively enrich training sets with high-value simulations, avoiding exhaustive mesh refinements or brute-force parameter sweeps. Finally, closed-loop design and control integrate CFD solvers with differentiable objectives—such as drag reduction, pressure distribution, or flow uniformity—yielding adaptive pipelines where simulation, optimization, and evaluation are tightly coupled [135–137].

Collectively, these advances mark a paradigm shift in scientific research: rather than treating simulation, learning, and design as separate steps, they are increasingly intertwined in adaptive, end-to-end workflows capable of addressing the inherent complexity and stochasticity of physical systems.

3 Examples of AI/ML use in soft matter

3.1 ML interatomic and coarse-grained potentials for soft matter

3.1.1 Equivariant message passing for atomistic resolution

Interatomic potentials are mathematical models that describe how atoms interact—essentially, they provide the energy of a system as a function of atomic positions. Traditional potentials (like Lennard–Jones or EAM) use fixed functional forms. Machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) replace those with neural networks or Gaussian processes trained on quantum-mechanical data (e.g., DFT). This allows MLIPs to be much more accurate while remaining computationally cheaper than ab initio calculations. Equivariant MLIPs have advanced rapidly in recent years. Methods such as NequIP [31], see Figure 1, introduced highly sample-efficient E (3)-equivariant convolutions, while MACE [32] leveraged higher-order message passing to achieve fast, accurate force predictions. Allegro further decoupled network capacity from message passing, scaling to millions of atoms at high throughput [33]. Although initially benchmarked on small-molecule datasets like rMD17, these approaches are increasingly applied to condensed-phase and soft-condensed systems, including those with long-range interactions and charge equilibration effects [138].

Figure 1. The NeqIP network architecture (a) A molecular or atomic system is represented as a graph, where nodes correspond to atoms and edges encode pairwise interactions within a specified cutoff, thereby defining local atomic neighborhoods. (b) Atomic numbers are embedded into initial scalar features (ℓ = 0), which are iteratively refined through a sequence of interaction blocks, yielding scalar and higher-order equivariant tensor features. (c) Each interaction block applies an equivariant convolution over the local graph to update atomic representations while preserving rotational symmetry. (d) The convolution operation is constructed as the tensor product of a learnable radial function R(r) of the interatomic distance and the spherical harmonic projection of the interatomic unit vector, which is subsequently contracted with neighboring atomic features. The resulting features are processed by an output block to predict atomic energies, which are aggregated to yield the total energy of the system. Reprinted from [31], licensed under CC BY.

For soft matter applications, polymer melts, ionic liquids, and other polar systems require careful treatment of long-range and many-body interactions [138–141]. Modern MLIPs integrate global charge equilibration and cutoff-aware message passing, enhancing transferability across densities and phases. Hybrid invariant/equivariant architectures or explicit polarization models are recommended for hydrated or strongly polar materials [138, 140, 142, 143]. Deployment strategies typically start with compact equivariant architectures (e.g., NequIP-like models) and scale only if model uncertainty remains significant. Active learning, coupled with on-the-fly molecular dynamics, can enrich training sets in regions of high epistemic uncertainty [144–148]. Validation should emphasize kinetic observables, such as transport and relaxation times, rather than force mean absolute error alone, as soft matter is often highly dynamics-sensitive.

3.1.2 Coarse-graining with GNNs

At the mesoscale, coarse-grained (CG) models reduce the number of degrees of freedom while retaining essential thermodynamic and kinetic properties [149]. Graph neural network (GNN)-based CG approaches have emerged [150], enabling simultaneous learning of mapping operators [151–153] and CG force fields [154, 155]. Iterative decoding schemes have also been explored to reconstruct atomistic detail from CG representations, maintaining consistency across resolutions [156, 157]. Recent work by [152], has formalized a workflow for machine learning–based coarse-graining (ML-CG) that integrates data preparation, mapping generation, force-field training, and validation under a unified framework, ensuring systematic benchmarking and thermodynamic transferability across state points. This workflow emphasizes curating representative training data, choosing an expressive yet physically meaningful model class (e.g., message-passing neural networks), and employing rigorous metrics such as free energy differences, structural distributions, and transport coefficients to evaluate CG model quality. A schematic of the ML-CG can be seen in Figure 2a.

Figure 2. (a) Workflow for machine learning–based coarse-graining (ML CG). Atomistic (AA) molecular dynamics simulations are first performed to generate trajectory data, which are mapped to a coarse-grained (CG) representation via a chosen mapping scheme (here, center-of-mass mapping). Reference forces on the CG beads are then computed using the force-matching (multiscale coarse-graining) formalism. These force–configuration pairs form the training data for a machine learning model based on the Hierarchically Interacting Particle Neural Network with Tensor Sensitivity (HIP-NN-TS) architecture, which learns the many-body CG force field. The trained model is then used to run CG molecular dynamics simulations, and the resulting structural and thermodynamic properties (e.g., radial distribution functions) are compared against AA results to evaluate model accuracy and transferability across state points. Reprinted from [152], licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. (b) Overview of the Deep Supervised Graph Partitioning Model (DSGPM) framework for coarse-grained mapping prediction. The molecular graph is first encoded by projecting one-hot atom and bond types into an embedding space and augmenting with atom degree and cycle indicators. These features are iteratively updated through message-passing neural network layers (NNConv) and gated recurrent units (GRU) to produce atom embeddings. The embeddings are L2-normalized and combined to form a learned affinity matrix, which is then used in a spectral clustering step to predict coarse-grained partitions. Training is guided by a metric-learning objective combining a cut triplet loss (encouraging separation of atoms across CG beads) and a non-cut pair loss (encouraging similarity of atoms within the same CG bead). Reprinted from [151], licensed under CC BY 3.0.

In parallel, graph neural network–based mapping prediction has been advanced by frameworks such as the Deep Supervised Graph Partitioning Model (DSGPM) [151], which treats CG mapping as a node-partitioning problem on a molecular graph–see Figure 2b. DSGPM jointly optimizes partition assignments and a supervised loss function to reproduce target CG mappings, incorporating chemical priors (e.g., functional groups, ring structures) to produce chemically interpretable partitions. This allows automatic discovery of optimal mapping operators that preserve structural and thermodynamic features while remaining generalizable to new molecules or state points.

Best practices for CG modeling include treating the mapping as a learned graph partition constrained by chemical and physical priors, combining force-matching with relative entropy or thermodynamic constraints to enhance transferability, and employing uncertainty-aware or ensemble training to prevent mode collapse in rugged energy landscapes [81, 158–161].

3.1.3 Differentiable MD engines

Differentiable molecular dynamics engines, such as JAX-MD [36] and TorchMD [37], allow gradients to flow through the simulation loop, enabling direct optimization of parameters against experimental data, trajectory alignment, or inverse design objectives. For soft matter, differentiability facilitates the tuning of coarse-grained potentials, nonbonded interactions, field-theory parameters, and differentiable constraints in mesoscale models, providing a unified framework for learning and simulation [162–165]. Building on this paradigm, differentiable molecular simulation (DMS) approaches–see Figure 3, such as that proposed by Greener and Jones [162], demonstrate that it is possible to learn all parameters in a CG protein force field directly from differentiable simulations. Their work couples a neural-network-based CG potential with a fully differentiable MD integrator, optimizing parameters end-to-end by backpropagating through complete trajectories. This enables direct minimization of loss functions defined on structural and thermodynamic properties (e.g., native-state stability, contact maps) without requiring hand-tuned potentials. The DMS framework thus provides a powerful route to data-driven CG force fields with improved accuracy and transferability, bridging simulation and learning in a single, differentiable pipeline.

Figure 3. Differentiable molecular simulation (DMS) method. (A) Analogy between a recurrent neural network (RNN) and DMS, where the same learnable parameters are reused at each step. (B) Learning the potential: a schematic shows how the energy function, initially flat at the start of training, adapts during training to stabilise native protein structures. (C) Force calculation: forces are derived from the learned potential using finite differences between adjacent energy bins, driving atoms toward native-like distances. Reprinted from [162], licensed under CC BY 4.0.

3.2 Inverse design and self-assembly

3.2.1 Learning to target phases and structures

Deep learning has become a transformative tool for mapping microscopic interaction parameters or building-block designs directly to emergent structures, enabling a paradigm shift from trial-and-error exploration to data-driven materials discovery. A landmark example is the work by Coli et al. [121], who employed deep-learning-based inverse design to train surrogate models that map colloidal particle interactions to target crystal structures. This approach dramatically accelerates the discovery process compared with brute-force searches in high-dimensional parameter spaces. Their approach can be seen schematically in Figure 4.

Figure 4. (A) Candidate interaction parameters are drawn from a multivariate Gaussian distribution, and each set is used to run a simulation of particle self-assembly. (B) Configurations from these simulations are evaluated by a convolutional neural network (CNN) trained to classify phases from their diffraction patterns, providing a fitness score based on similarity to the target structure. (C) The covariance matrix adaptation evolutionary strategy (CMA-ES) updates the Gaussian distribution, shifting it toward regions of parameter space that yield higher fitness, thereby iteratively refining the design until the target phase is stabilized. Reprinted from [121], licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Recent follow-up studies extend these methods to increasingly complex systems. For example, Wang et al. [166] applied enhanced sampling techniques in combination with deep learning to predict open and intricate crystal structures that are otherwise difficult to access. Similarly, multiobjective inverse design frameworks now allow simultaneous optimization of competing criteria such as nucleation kinetics, yield, and structural robustness [167], illustrating the growing sophistication of AI-guided materials design.

A common “design loop” pattern has emerged in these workflows:

1. Propose: candidate designs are suggested using surrogates, large language models, or genetic algorithms.

2. Simulate/evaluate: candidates are evaluated through molecular dynamics (MD), Monte Carlo (MC), density functional theory (DFT), or self-consistent field theory (SCFT) simulations.

3. Update: the design model is refined using Bayesian optimization or active learning strategies to prioritize promising regions of parameter space.

4. Iterate: the loop continues until design constraints or target properties are satisfied.

Increasingly, differentiable simulation engines enable gradients of observables—such as order parameters or structure factors—to be backpropagated directly to design parameters, further accelerating convergence and allowing for end-to-end differentiable inverse design pipelines.

3.2.2 DNA-programmed and patchy colloids

Programmable DNA linkers and patchy colloids offer unprecedented control over interparticle interactions, making them a natural playground for AI-assisted self-assembly design. By encoding specific binding patterns into DNA strands or particle patches, researchers can direct the formation of complex structures with nanoscale precision. Recent demonstrations include the seeded growth of DNA-coated colloids into macroscopic photonic crystals [168], highlighting the potential for optical materials with tunable properties. In parallel, Liu et al. [169] demonstrated the inverse design of DNA-origami lattices using computational pipelines, where ML-guided design predicts sequences and assembly pathways that yield target lattice architectures. These approaches exemplify how the combination of programmable building blocks and AI enables the rational engineering of functional materials from the bottom up.

3.2.3 Polymer sequence and architecture design

In soft materials, polymer sequence and architecture strongly influence macroscopic properties, from mechanical performance to self-assembled morphologies. Active-learning workflows now explore vast polymer sequence spaces by coupling physics-based simulators with ML surrogates, forming closed-loop systems where computational predictions inform experimental synthesis and vice versa [170]. In parallel, molecular simulation of coarse-grained systems using machine learning has emerged as a powerful strategy to accelerate exploration of chemical and conformational space. By leveraging ML-derived force fields or coarse-grained potentials, these methods can capture essential molecular interactions at a fraction of the computational cost of all-atom simulations. When integrated into active-learning pipelines, such coarse-grained ML models enable rapid screening of polymer sequence variants, identification of design rules, and prediction of emergent material properties under experimentally relevant conditions [159].

Coarse-grained and reverse-mapped simulations of long-chain atactic polystyrene [171] show how coarse models parameterized via iterative Boltzmann inversion can replicate chain conformation, thermodynamics, and entanglements in high molecular weight melts. Work on isotactic polypropylene [172] shows how coarse grain potentials can be crafted to preserve fine structural features like helicity. On the dynamics/rheology side, the viscoelastic behavior of melts has been studied in multiscale frameworks (e.g., expanded ensemble Monte Carlo + nonequilibrium MD) [173] to access mechanical and time-dependent properties. A recent ML-hybrid coarse-graining framework [174] directly ties into these strategies, enforcing both bottom-up structure matching and top-down density/thermodynamics, while delivering transferability.

These collective efforts illustrate how ML methods are increasingly able to augment and extend older hierarchical/coarse-grained simulation approaches. By combining efficient sampling (connectivity altering MC, reverse mapping), richly parameterized CG force fields, and ML surrogates/optimization loops, one can push toward materials design frameworks that not only predict but optimize polymer sequence and architecture for target behaviors (mechanical moduli, morphology, rheology, etc.), possibly with experimental feedback in closed form.

3.3 Physics-informed machine learning and hybrid models in computational fluid dynamics

The rapid progress of ML/AI has opened new opportunities in computational fluid dynamics (CFD), where traditional numerical solvers often face challenges related to computational cost, high-dimensional parameter spaces, and complex nonlinear dynamics. Physics-informed machine learning (PIML) offers a promising path forward by embedding governing physical laws, such as the Navier–Stokes equations, directly into learning architectures. This integration enables models to generalize better, respect conservation principles, and require less data than purely data-driven approaches. Hybrid models, which combine conventional numerical solvers with ML components, further enhance predictive accuracy and efficiency, making them attractive tools for turbulence modeling, multiscale simulations, and real-time flow prediction.

3.3.1 Physics-informed machine learning in fluid mechanics

Physics-Informed Machine Learning (PIML) represents a paradigm in which governing equations, symmetries, and physical constraints are embedded directly into the learning process. By integrating physics into the model architecture or loss functions, PIML approaches reduce the reliance on large datasets and mitigate unphysical predictions in extrapolative regimes. The article by Karniadakis et al. [98] played a pivotal role in catalyzing interest in these methods, providing a comprehensive overview of approaches such as physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), operator learning, and symbolic regression for equation discovery [98, 175–177].

Applications of PIML are rapidly expanding into soft condensed matter systems, where accurate modeling of complex fluids and materials is often limited by experimental sparsity or computational cost. Operator learning and neural operators can efficiently approximate field-to-field mappings, such as predicting stress or flux distributions from concentration or velocity fields, across varying geometries and boundary conditions [178–182]. In parallel, hyperdensity functional theory (HDFT), which generalizes classical density functional theory to arbitrary thermal observables, has been combined with ML representations to accelerate the computation of thermodynamic properties and phase behavior [183–186].

PINNs–see Figure 5–and hybrid residual models have shown particular promise in this domain. By enforcing the underlying differential equations as constraints, PINNs can regularize sparse experimental or simulation data, providing physically consistent interpolations [175, 187, 188]. Hybrid residual models, where machine learning predicts corrections to a baseline theory such as DFT or self-consistent field theory (SCFT), allow the combination of robust theoretical frameworks with data-driven flexibility, enhancing generalization in low-data regimes [189–194].

Figure 5. Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) are a class of machine learning models that incorporate physical laws, typically expressed as partial differential equations (PDEs), into the training process of neural networks. Unlike traditional neural networks, which rely solely on data-driven learning, PINNs embed the governing equations of the system directly into their loss function. This allows them to simultaneously fit available observational data and enforce consistency with the underlying physics. In practice, the input to a PINN (e.g., spatial or temporal coordinates) passes through a neural network to predict a physical quantity of interest (such as velocity, pressure, or displacement). The model then computes derivatives of this output with respect to the inputs using automatic differentiation. These derivatives are used to evaluate the residuals of the governing PDEs, which are minimized alongside the data mismatch during training. By combining data with physical constraints, PINNs can achieve robust generalization, require less training data, and provide physically consistent solutions even in regions where data is sparse or unavailable. This makes them particularly powerful for scientific computing, engineering design, and modeling complex systems governed by physics. In the figure, input spatial coordinates x and y are fed into the neural network, which produces corresponding outputs of the real and imaginary parts of the complex physical quantities (P and Q). During each iteration, the neural network computes the derivatives using automatic differentiation, while also incorporating physics-based regularization. After each iteration, the loss function (L) is updated to include weighted losses from both the neural network and the physics PDE residuals. Training of the neural network continues until the loss function falls below a specified tolerance level (error bound) and stops once the tolerance is achieved. Reprinted from [195], licensed under CC BY.

For soft matter applications, it is particularly important to encode symmetries and conservation laws early in the modeling process, as this reduces the risk of unphysical extrapolations. Operator learning is advantageous for field-to-field mappings, since neural operators can efficiently generalize across different geometries and boundary conditions [178, 179, 196]. At the same time, hybrid residual models that learn corrections to existing theoretical frameworks improve predictive accuracy while maintaining consistency with established physics [189, 190, 192]. Emerging trends in PIML for soft matter include the integration of machine learning with coarse-grained simulations and kinetic models, which enables the study of multiscale phenomena and complex non-equilibrium processes with greater efficiency and accuracy [180, 181, 194].

3.3.2 Integration of ML in CFD

In the realm of CFD, the integration of machine learning techniques has been transformative. Machine learning models, particularly PINNs, have been employed to solve complex fluid dynamics problems governed by partial differential equations (PDEs) [98]. These models incorporate physical laws directly into the learning process, allowing for accurate predictions even with limited data.

For instance, in the study by Cai et al. [180], PINNs are applied to simulate three-dimensional wake flows and supersonic flows, demonstrating their capability to handle complex fluid dynamics scenarios. Similarly, in biomedical applications, PINNs have been utilized to model blood flow in arteries, providing insights into hemodynamics without the need for extensive experimental data.

Moreover, recent advancements have focused on enhancing the training strategies for PINNs to improve their performance in stiff fluid problems. A novel approach called “re-initialization” has been proposed by Raisi et al. [175], which periodically modulates the training parameters of the PINN model. This strategy enables the model to escape local minima and effectively explore alternative solutions, leading to more accurate and physically plausible results in simulations of fluid flows at high Reynolds numbers.

3.3.3 Hybrid models and surrogates in CFD

Hybrid models that combine traditional CFD methods with machine learning techniques have shown promise in accelerating simulations and improving accuracy. These models leverage the strengths of both approaches: the physical rigor of CFD and the data-driven adaptability of machine learning.

For example, in turbulence modeling, machine learning algorithms such as Tensor Basis Random Forests (TBRF) have been used to predict Reynolds stress anisotropy and integrated into Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) solvers, yielding results close to Direct Numerical Simulation/Large Eddy Simulation (DNS/LES) references with physical consistency [197]. Physics-informed ML approaches have also been developed to correct discrepancies in RANS-modeled Reynolds stresses using DNS data, improving predictions in high-Mach-number turbulent flows [198]. Iterative ML-RANS frameworks that seamlessly integrate ML algorithms with transport equations of conventional turbulence models have demonstrated enhanced predictive capability across varying Reynolds numbers, including separated flows [199]. Broader reviews underscore the blend of ML corrections and classical closure modeling—for example, through tensor basis neural nets, gene-expression programming, and physically informed field inversion—highlighting the importance of preserving physical compatibility while enhancing model flexibility [200].

Additionally, machine learning-based surrogates have been developed to replace expensive CFD simulations in optimization problems. These surrogate models rapidly approximate flow behaviors across design parameters, enabling efficient design iteration in engineering contexts [201]. Comparative studies indicate that while polynomial regression surrogates are efficient and suitable for capturing interaction effects, Kriging-based models often offer superior exploration and predictive accuracy across complex design spaces [202].

4 Why AI changes scientific software?

Scientific software has always mediated between hypotheses and evidence. What is different now is the centrality of data-driven components—statistical models, deep nets, and increasingly, foundation models—that behave like mutable dependencies tied to evolving data and compute environments. This mutability stresses classical software engineering abstractions and makes end-to-end reproducibility harder if not explicitly designed in from the start. The work by Sculley et al. [68] on “hidden technical debt” in ML systems captures the mismatch between quick experimental wins and long-term maintainability, highlighting ML-specific risks such as boundary erosion, data entanglement, configuration debt, and feedback loops.

In parallel, the reproducibility movement codified the FAIR principles for research objects, while the computational biology and software carpentry communities articulated pragmatic rules for reproducible analysis and “good enough” practices for everyday research code [61, 203].

When LLMs are leveraged for code generation in scientific workflows, additional layers of complexity emerge around verification protocols, documentation standards, and bias mitigation. First, ensuring physical correctness of LLM-generated code (for example, that a simulation correctly enforces conservation laws or boundary conditions) may require formal verification or embedded test-suites. Councilman et al. [204] proposes formal query languages and symbolic interpreters to verify that generated code matches user intent. Second, documentation standards must evolve: contributions from generative AI should be explicitly versioned, timestamped, and tagged with model-identifier and prompt context, so that audits can trace “human vs. model vs. hybrid” authorship. Provenance frameworks like PROV-AGENT [53] underscore the need to capture prompts, agent decisions and model versions in end-to-end workflows. Third, scientific workflows must account for model bias and automation-bias: for instance, LLMs may over-produce boilerplate or mirror biases embedded in their training code corpora (e.g., skewed co-authorship networks, under-representation of certain methodologies). Auditing and bias-mitigation frameworks for LLMs emphasise transparent documentation of training data sources, limitations, and periodic external review [205]. In sum, embedding LLMs into scientific computational pipelines must be accompanied by codified verification protocols, upgraded documentation practices, and bias-aware governance if we are to maintain scientific integrity, reproducibility, and accountability.

These trends converge on a question: what should “good” scientific software look like in an AI- intensive world? This paper proposes a lifecycle-oriented answer grounded in peer-reviewed methods, industry-tested practices, and governance frameworks.

4.1 Research agenda and open issues

Scientific software increasingly incorporates ML/AI components, introducing unique challenges that traditional software engineering practices do not fully address. These challenges arise from the centrality of data, non-deterministic computation, complex provenance requirements, and evolving governance expectations. Data must be treated as a first-class dependency, as ML/AI systems are exceptionally sensitive to the distributional properties of their training and evaluation datasets. As datasets evolve—through the addition of new samples, schema revisions, error corrections, or re-labeling—model behavior may shift in ways that compromise replicability. Without explicit dataset versioning and documentation, reproducing earlier results becomes infeasible. Sculley et al. highlighted data dependencies as a key source of “hidden technical debt” in ML systems, and recent work on data versioning emphasizes that it is not enough to track file revisions: schema, feature encodings, and labeling functions must also be recorded to preserve the semantics of the experiment [206].

ML/AI pipelines further complicate reproducibility because of their inherent non-determinism and hardware variability. Stochastic elements such as random initialization, minibatch shuffling, parallel execution order, and non-deterministic GPU kernels can lead to divergent model outcomes. Moreover, floating-point arithmetic differences across hardware accelerators exacerbate this variability. Exact bitwise reproducibility may therefore be infeasible, but statistical reproducibility—achieved through reporting distributions, confidence intervals, and variance across multiple runs—remains attainable. The reproducibility literature recommends controlling random seeds, pinning library versions, and specifying hardware to mitigate uncontrolled variability [66, 207].

Ensuring reproducibility also requires careful experiment tracking and provenance capture. Reproducible computational science depends on documenting the full set of experimental degrees of freedom: hyperparameters, preprocessing pipelines, data versions, model checkpoints, software stack, and hardware configuration. Provenance-aware workflows, supported by tools such as DVC or Collective Knowledge, enable rigorous auditability and repeatability [208]. Neglecting this leads to “configuration debt,” where small, undocumented changes produce irreproducible results [68].

Scientific credibility also depends on robust benchmarking and statistical rigor. Over-tuning to a single benchmark, omitting variance estimates, or reporting only the best-case result risks producing fragile conclusions. Best practice calls for repeated trials, ablation studies, and reporting of uncertainty intervals to distinguish genuine improvements from noise [67, 209].

Moreover, when ML/AI systems are applied to sensitive domains such as health, climate modeling, or biosecurity, they carry significant societal risks. The NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) provides a voluntary approach for documenting and mitigating risks [107], while the EU AI Act establishes a binding risk-tiered regulatory regime with explicit obligations for high-risk system [108]. Both frameworks emphasize documentation, monitoring, incident response, and human oversight as first-class concerns for scientific ML software.

Finally, long-term maintainability remains a pressing concern, as ML pipelines accumulate technical debt over time—often more quickly than traditional scientific code due to data entanglement, rapidly evolving dependencies, and ad hoc experimentation. Empirical studies of self-admitted technical debt in ML software show that data preprocessing and model training code are common sources of persistent debt that hinders maintainability and reproducibility [59]. Designing modular, testable components and adopting continuous integration practices are therefore critical for sustainable scientific AI development.

4.1.1 Standardized evaluation sets and living benchmarks

Scientific AI would benefit from evaluation suites that are durable, community-maintained, and transparent about their evolution. Benchmarks should include versioning, change logs, and clear governance for updates so that results remain comparable over time. For example, the work by Olson et al. [210] is a curated, evolving collection of datasets that standardizes dataset formats and provides meta-feature analyses to expose gaps in benchmark diversity. Similarly, Takamoto et al. [211] introduces a suite of tasks based on partial differential equations; it provides both simulation data and baselines, along with extensible APIs so future contributions and new PDE tasks can be added. Another recent work by Wang et al. [212], argues for carefully curated benchmark suites (rather than single-score leaderboards) to expose trade-offs in fairness metrics and prevent superficial optimization. Yet in many scientific fields, such living benchmarks are still rare; community stewardship, funding, and infrastructure to host evolving benchmark standards remain gaps.

4.1.2 Auditable training data and provenance

While standardized benchmarks help evaluate models fairly, transparency about training data provenance is equally critical. Transparency in the provenance of training data—including licensing, consent, content authenticity, and lineage—has become increasingly recognized as critical, especially as models consume large, diverse, and partially opaque datasets. A number of recent works provide promising solutions, but implementation remains sporadic and many gaps persist. One such system is Atlas [213], which proposes a framework enabling fully attestable ML pipelines. Atlas leverages open specifications for data and software supply chain provenance to collect verifiable records of model artifact authenticity and end-to-end lineage metadata. It integrates trusted-hardware and transparency logs to enhance metadata integrity while preserving data confidentiality during pipeline operations. Another is PROV-IO+ [214], which targets scientific workflows on High Performance Computing (HPC) platforms. PROV-IO + offers an I/O-centric provenance model covering both containerized and non-containerized workflows, capturing fine-grained environmental and execution metadata with relatively low overhead. Automated provenance tracking in data science scripts is also addressed by tools like Vamsa [215], which extract provenance information from Python scripts without requiring changes to user code; for example, Vamsa infers which dataset columns were used in feature/label derivations with high precision and recall. A more domain-spanning review is by Gierend et al. [216], which examines the state of provenance tracking in biomedical contexts. They find that although many frameworks and theoretical models exist, completeness of provenance coverage is often lacking—especially concerning licensing, consent, and downstream lineage metadata. Αnother systematic literature review that focuses specifically on healthcare systems is by Ahmed et al. [217]. It highlights how GDPR and similar regulatory pressures increase demand for provenance, but notes that many current provenance technologies fail to capture sufficient context (who created data, under what consent, under what license) or do so in ways that do not scale. Finally, Schelter et al. [218] propose correctness checks and metadata computation based on the provenance of training data and feature matrices; for instance, determining whether test and training sets originate from overlapping data records via lineage queries, which helps guard against data leakage.

4.1.3 Debt-aware design

Machine learning systems accumulate technical debt in many forms: tangled pipelines, configuration debt, insufficient tests, and feedback loops that degrade model quality over time. Empirical studies are starting to quantify this. For instance, Bhatia et al. [59] show that ML projects often admit twice as much debt (in code comments) as non-ML projects, particularly in data preprocessing and model generation components. Another recent work by Pepe et al. [219] categorizes DL-specific technical debt, showing patterns of suboptimal choices tied to configuration, library dependencies, and model experimentation. Further, Ximenes et al. [220] identifies dozens of specific issues in ML workflows that contribute to debt, with data preprocessing being especially debt-heavy. The community would benefit from standardized metrics for ML debt, tool support for detecting and refactoring debt, and best practices to avoid it.

4.1.4 Executable publication

End-to-end re-executability is essential for reproducibility in scientific AI. Interactive formats like Jupyter notebooks improve transparency but often suffer from hidden state, missing dependency specifications, and ad hoc execution order, which introduce drift unless workflows are version-pinned and validated via continuous integration (CI). Wang et al. [221] report that over 90% of notebooks lack declared dependency versions (SnifferDog can recover many missing environment metadata); Saeed Siddik et al. [222] document hidden state and out-of-order execution and recommend explicit environment files plus CI; and Grayson et al. [223] quantify that a significant fraction of workflows from curated registries fail due to missing dependencies, environment mismatches, or undocumented configuration—even when containerized.

Publication models increasingly treat code, data, and workflows as a single research object: Peer et al. [224] propose integrating artifact review and metadata creation into publication, but adoption is uneven due to limited infrastructure and weak journal policies. The FORCE11 Software Citation Principles [203] define minimal metadata for citable software (identifiers, versioning, authorship, access, persistence), and journals such as SoftwareX and JOSS now support software publications. Nonetheless, reproducibility studies [221, 223] show many notebooks still fail to pin dependencies or reproduce reliably, underscoring the need for explicit dependency management and CI-based execution to ensure long-term recomputability.

4.1.5 Regulatory-grade documentation

As regulatory regimes such as the EU AI Act come into force, the need for documentation that meets audit and compliance requirements—beyond good research reporting—has become increasingly clear. Existing practices like Model Cards and Datasheets provide useful scaffolds but often lack the completeness or structure demanded by regulation. Recent work seeks to make documentation “regulatory-gr ade” by design. Lucaj et al. [225] introduce open-source templates for documenting data, model, and application components across the AI lifecycle, explicitly aligning with EU AI Act technical documentation requirements to ensure traceability and reproducibility. Golpayegani et al. [226] propose a framework for human- and machine-readable risk documentation that is interoperable, updatable, and exchangeable between stakeholders. Brajovic et al. [227] extend Model and Data Cards with “use-case” and “operation” cards to better support certification, third-party audits, and compliance. Bogucka et al. [228] contribute an impact assessment template grounded in the EU AI Act, NIST AI RMF, and ISO 42001, co-designed with practitioners and shown to be more comprehensive than baseline reports.

AI governance in scientific contexts benefits from formal frameworks that ensure ethical, robust, and legally compliant systems. The NIST AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0) [107] provides a voluntary but comprehensive structure around governance, risk identification, measurement, and monitoring. Scientific teams can adapt it by maintaining risk registers for failure modes (e.g., hallucination, prompt injection, content provenance errors), defining internal controls, and assigning governance responsibilities. Its Generative AI profile highlights risks specific to foundation models, such as misleading outputs and adversarial attacks, and suggests mitigation strategies.

The European Union’s AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) establishes a binding, tiered risk regime. High-risk AI systems must provide technical documentation, implement rigorous data governance (with representative and accurate datasets), enable human oversight, ensure robustness, and perform post-market monitoring. The Act came into force in August 2024, with most high-risk obligations phased in by August 2026 [229]. Scientific software in high-risk domains—such as medical devices or decision-support systems—must align development workflows with these requirements, including dataset annotation, evaluation documentation, deployment traceability (e.g., logs), and incident monitoring. These regulations do not replace sound engineering practice but formalize it, embedding documentation, monitoring, and traceability as core, non-optional elements of trustworthy scientific AI development.

4.2 From reproducibility to recomputability: principles that travel

Reproducible computational science requires that code, data, parameters, and environments be published in a form that others can rerun. Seminal commentaries and “Ten Simple Rules” have made this agenda mainstream across fields. In practice, recomputability relies on four pillars: (i) capture of code + environment; (ii) declarative workflows; (iii) verifiable provenance; and (iv) complete reporting (92,93).

4.2.1 Environments and packaging

Managing computational environments and dependencies is a persistent challenge in reproducible research. Tools like ReproZip [230] help alleviate this by tracing operating system calls to automatically capture all the files, libraries, environment variables, and configuration parameters used during an experiment, then packaging them into a portable bundle [231]. This portable bundle can be unpacked and executed on a different system—be it via Docker, Vagrant, or chroot setups—allowing reviewers or other researchers to reproduce results without manually installing dependencies [232]. Importantly, these generated packages include rich metadata and a workflow specification, which facilitate not only reproducibility but also review by enabling reviewers to explore and vary experiments with minimal effort [233]. In addition, extensions allow bundles to be unpacked and executed through a web browser interface, further lowering the barrier for reproducibility and streamlining reproducibility checks during journal review processes [232].

4.2.2 Executable narratives

Tools like Jupyter notebooks have become one of the most influential tools for open and reproducible science, popularizing the concept of executable papers [234] — documents that interleave prose, code, and results in a single narrative. This format promotes transparency by allowing readers to inspect methods, rerun analyses, and explore alternative scenarios interactively. Their adoption spans a wide range of domains, from bioinformatics and computational physics to social sciences and education [49, 235–237]. However, the growing reliance on notebooks has also triggered systematic studies of reproducibility, revealing common pitfalls such as hidden state, missing dependencies, or non-deterministic outputs [238]. To address these issues, best practices have been proposed, including pinning dependencies to specific versions to avoid “code rot,” parameterizing notebooks to make analyses reusable across datasets and experiments, and enforcing continuous execution (e.g., restarting kernels and running all cells in order before publishing) to ensure a clean, deterministic workflow [237, 239]. Collectively, these practices are helping to transform notebooks from ad hoc exploratory artifacts into rigorously reproducible and reviewable scientific records.

4.2.3 Workflows

Scientific workflow management systems such as Snakemake [240] and Nextflow [241] enable users to define pipelines in a declarative manner, transforming a collection of individual computational tasks into coherent, reproducible workflows. In these frameworks, each step—or rule in Snakemake and process in Nextflow—is declared in terms of its inputs, outputs, and execution logic, while the workflow engine orchestrates the execution order and handles dependencies automatically [242]. This declarative abstraction brings clarity and maintainability to pipeline design, facilitates reproducibility through versioning and container integration, and enables seamless scalability across local, HPC, and cloud environments [243], aligning naturally with FAIR and provenance capture [61]. Furthermore, the use of domain-specific languages built on familiar programming languages—Python for Snakemake and Groovy for Nextflow—strikes a balance between expressivity and readability, appealing to bioinformatics practitioners with programming proficiency.

4.2.4 Reporting standards

FAIR, Model Cards, and Datasheets. Reporting standards are a cornerstone of transparent and trustworthy AI and data-driven research. The FAIR principles provide a widely adopted “north star” for managing data, code, and metadata, emphasizing persistent identifiers, rich machine-readable metadata, provenance tracking, and use of shared vocabularies [63, 66, 203, 244]. While FAIR primarily addresses the technical infrastructure required to make research objects reusable, additional community-driven efforts have emerged to capture the social and contextual dimensions of machine learning artifacts. Among these, Model Cards provide structured documentation for trained machine learning models, summarizing intended uses, performance metrics, trade-offs, and known limitations to guide responsible deployment [245]. Similarly, Datasheets for Datasets standardize dataset reporting by describing motivation, composition, collection methods, preprocessing steps, and potential biases, enabling users to assess suitability and ethical implications before use [246, 247]. Together, these frameworks complement FAIR by adding human-interpretable context and domain-specific guidance. Recent extensions have sought to broaden this ecosystem. Proposals like “FAIR 2.0” emphasize semantic interoperability and machine-actionable services that enhance cross-domain data integration [244], while specialized frameworks such as DAIMS [248] focus on reproducibility and regulatory compliance in medical and clinical AI datasets. Collectively, FAIR, Model Cards, Datasheets, and their extensions are converging toward a multi-layered approach to reporting, where technical, ethical, and contextual considerations are captured in complementary ways to support reproducibility, interpretability, and accountability in computational research.

4.3 Architecture patterns for AI-enabled scientific software

4.3.1 Data-centric pipelines

Modern scientific ML systems increasingly treat data as a first-class asset and design pipelines around its controlled evolution. Raw experimental or observational data are stored in read-only “immutable zones,” protected by cryptographic digests to ensure integrity. From these immutable sources, derived datasets are curated, schema-validated, and versioned, with their lineage, consent information, and known hazards documented in datasheets [246]. The orchestration of data extraction, transformation, training, and evaluation steps is typically expressed as a declarative directed acyclic graph (DAG) using workflow engines such as Snakemake or Nextflow. Each pipeline stage is coupled with explicit environment specifications—using Conda environments or container images—which strengthens portability and reproducibility across systems [249]. To guarantee consistent experimental outcomes, dataset and feature versioning are adopted as standard practice. Content-addressed storage and snapshotting ensure that identical data hashes yield identical training sets, eliminating ambiguity introduced by evolving datasets. Feature stores with explicit contracts enforce stable, well-documented feature definitions and prevent silent breakages when features change. Each trained model artifact is coupled with a manifest that captures the full provenance of data, code, and configuration, often aligning with W3C PROV principles to enable rigorous traceability and reproducibility [250].

4.3.2 MLOps-aware lifecycles

The software lifecycle is increasingly extended to incorporate ML-specific processes, giving rise to a “continuous science” approach. Experiment tracking systems automatically record hyperparameters, data hashes, random seeds, metrics, and model artifacts, ensuring that every run is fully auditable and reproducible. Candidate models are promoted to registries with semantic versioning and are accompanied by Model Cards that document their intended use, performance characteristics, and ethical considerations [61]. Classical DevOps pipelines are similarly extended with continuous integration, delivery, and training (CI/CD/CT) capabilities. These pipelines incorporate continuous training triggers, model drift detectors, and shadow deployments, enabling the safe rollout of retrained models when data distributions evolve [251, 252]. Once deployed, operational monitoring expands beyond traditional measures of system uptime and latency to include data quality checks—such as monitoring for missingness or schema violations—real-time model performance on evaluation slices, and fairness or robustness indicators. In the event of detected regressions, incident response playbooks specify immediate rollback to previous model versions, minimizing the risk of propagating errors in production [218].

While the discussion above draws heavily from mature industrial MLOps stacks, most academic scientific environments operate under fundamentally different constraints. Research laboratories typically have small development teams, reliance on heterogeneous and sometimes outdated HPC environments, and budgets tied to 2–3-year grant cycles that rarely support long-term DevOps engineering roles. Continuous deployment, automated retraining, feature stores, and 24/7 monitoring may therefore be aspirational rather than feasible [253, 254].

An emerging distinction is thus between industrial-grade MLOps, emphasizing reliability at scale, operational risk management, and ongoing maintenance, and academic-grade MLOps, which prioritizes recomputability, transparent provenance, low-cost automation, and knowledge transfer across student turnover. Academic-grade workflows tend to benefit most from lightweight components: version-controlled experiment tracking, containerized execution environments, and periodic—not continuous—retraining schedules [255, 256]. Cloud-based managed services such as GitHub Actions, GitLab CI, and low-cost experiment trackers (e.g., Weights & Biases academic tiers, MLflow on institutional clusters) help reduce infrastructure burden while preserving visibility into the full model lifecycle [257, 258]. In many cases, “minimum viable MLOps” aligned with FAIR principles—clear metadata, accessible artifacts, and documented pipelines—is sufficient to ensure a scientific software system can be understood, reused, and extended after the original project ends [254, 255]. Developing a shared vocabulary for academic-grade MLOps may help align software sustainability expectations between domain scientists, grant agencies, and research software engineers, enabling reproducibility without imposing industry-scale operational complexity.

4.4 Testing and verification for data and models

Testing AI-enabled scientific software must extend far beyond simple unit tests; it needs to cover data integrity, model behavior, reproducibility, and robustness under changing conditions. Without such a thorough testing and verification regime, scientific conclusions risk being fragile, untrustworthy, or non-reproducible.

A reimagined “testing pyramid” for AI systems begins with verification at the data and software component level and builds up to more global model and system tests. At the base are unit and property tests: these verify correctness of data transformations, feature-engineering routines, and numerical stability under edge cases (for example, ensuring scaling, normalization, or interpolation functions behave well when confronted with missing or extreme values). In parallel, schema contracts and data validation checks must be enforced at pipeline boundaries to ensure that inputs and outputs maintain expected formats, distributions, and statistical properties (such as ranges, missingness, and label balance).

At the model level, verification includes deterministic “smoke tests” in which seeded runs are used to confirm basic correctness and detect glaring issues (such as exploding gradients or failures to converge). Further up, metamorphic testing strategies are essential where exact oracles are unavailable: if certain input transformations should lead to predictable output relationships (such as invariance, monotonicity, or symmetry), metamorphic relations can be used to detect faults. An example is the recent study by Reichert et al. [259], which shows how metamorphic testing can uncover differences in model behavior even when traditional calibration/validation passed. Regression tests using fixed evaluation sets also guard against unintended degradations of performance after refactoring or retraining.

Robustness and distribution-shift testing are also indispensable. Scientific models frequently face scenarios outside their original training regime: shifts in input distributions, unseen subpopulations, or perturbed environmental conditions. Evaluations should therefore report not just aggregate metrics, but also performance broken down by relevant subgroups and under explicit shifts. Documentation frameworks such as Model Cards recommend that model developers list limitations, intended use cases, and failure modes to help users understand where a model may or may not generalize. The work by Mitchell et al. [61] is a proposing approach for such structured documentation.

Finally, reproducibility checks should be built into both the development pipeline and the peer review process. Authors should publish code or scripts that regenerate figures, archive intermediate artifacts (datasets, feature transformations, model checkpoints), and specify seed settings and hardware details. The peer-review community is increasingly endorsing “artifact evaluation” tracks or badges to incentivize reproducible submissions. In related work, Liang et al. [260] examin how well model documentation practices currently fulfill transparency and reproducibility goals. Also, Amith et al. [261] propose ways to ensure model documentation is computable, structured, and machine-interpretable.

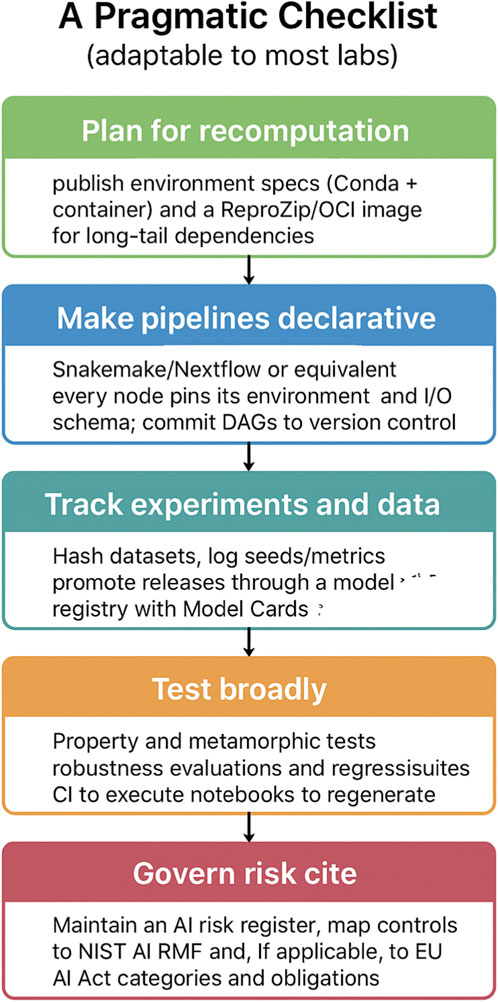

5 A pragmatic checklist (adaptable to most labs)

To promote reproducibility and transparency, research workflows should be designed with recomputation in mind - see Figure 6. This requires publishing detailed environment specifications, such as Conda configurations paired with container images, and supplementing them with tools like ReproZip or OCI images to safeguard against long-tail dependencies. Beyond environment management, computational pipelines should be made declarative. Frameworks such as Snakemake or Nextflow, or their equivalents, allow each node to explicitly define its environment and input–output schema. These directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) should be committed to version control to ensure consistency and traceability over time.

Figure 6. A pragmatic checklist for reproducible and responsible research. The checklist outlines five key practices adaptable to most laboratory settings: planning for recomputation through published environment specifications; making computational pipelines declarative and version-controlled; systematically tracking experiments and datasets; conducting broad testing, including robustness and regression evaluations; and governing risk through structured registers and compliance with established frameworks.

Equally critical is the systematic tracking of experiments and data. Datasets should be hashed, and experimental seeds and metrics rigorously logged to guarantee reproducibility across runs. Model releases should be promoted through a registry that includes standardized documentation, such as Model Cards, to capture intended use and performance characteristics. Once pipelines and data management are in place, testing must extend beyond simple validation. Property-based and metamorphic testing, robustness evaluations, and regression testing should be systematically employed. Continuous integration pipelines can be used to automatically execute notebooks and regenerate results, ensuring that updates do not compromise earlier findings.

Finally, responsible research demands proactive governance of risk. This entails maintaining an AI risk register and aligning controls with established frameworks such as the NIST AI Risk Management Framework. Where relevant, compliance with regulatory frameworks, such as the European Union’s AI Act, should also be ensured. Mapping obligations to these categories not only mitigates risks but also fosters trustworthiness and accountability in research practices.

5.1 Practical blueprint: building an AI-era soft-matter stack

The development of an AI-era soft-matter simulation stack involves a structured, multi-stage workflow that integrates computational modeling with machine learning. Figure 7 illustrates a structured workflow for constructing an AI-driven soft-matter modeling stack, integrating multiscale simulations, machine learning, and uncertainty quantification. The process begins with problem framing, where the appropriate resolution—ranging from atomistic to coarse-grained to field-level representations—is selected according to the target observables. This step ensures that subsequent modeling efforts are aligned with the scientific questions of interest. Following this, a data strategy is established, which involves curating initial seed datasets, defining active-learning policies to iteratively improve model performance, and maintaining detailed provenance records to guarantee reproducibility.

Figure 7. Practical blueprint for constructing an AI-era soft-matter simulation stack. The workflow progresses through six key stages: (1) Problem framing—selecting resolution and target observables; (2) Data plan—curating seed data, defining active-learning policies, and logging provenance; (3) Model choice—deploying equivariant GNNs for atomistic scales, GNN-CG for mesoscale, and physics-informed hybrids for field models; (4) Differentiable loop—enabling end-to-end training with JAX-MD/TorchMD and exposing order parameters as losses; (5) VVUQ gates—validating kinetics and thermodynamics while calibrating uncertainties; and (6) FAIR and DevEx—ensuring reproducibility, containerization, and compliance with FAIR4RS guidelines.

The modeling stage leverages modern machine learning architectures tailored to the system scale: equivariant graph neural networks are employed for atomistic systems, coarse-grained GNNs for mesoscale representations, and hybrid physics-informed networks for continuum or field-level models. These models are integrated within a differentiable training loop, often implemented using frameworks such as JAX-MD or TorchMD, which allows order parameters and physical observables to be directly exposed as loss functions, enabling end-to-end optimization of both predictive accuracy and physical consistency.