- 1Faculty of Software, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, Liaoning, China

- 2Faculty of Electrical and Control Engineering, Liaoning Technical University, Huludao, Liaoning, China

Bearing defect detection is crucial for equipment safety and maintenance costs, but challenges remain under complex textured backgrounds, reflective stains, and irregular defect shapes. This paper presents the LSA-YOLO method for industrial field applications, which strengthens detail retention through low-order feature aggregation, improves irregular defect representation through multi-scale residual modeling, and enhances anti-interference ability via a progressive spatial attention mechanism, without the need for additional annotations or complex post-processing. Experimental results on a bearing surface defect dataset show that LSA-YOLO achieves a good balance between precision and efficiency, with an F1 score of 88.1% and mAP@0.5 of 92.6%, significantly outperforming the baseline model. This method is suitable for online quality inspection scenarios, and relevant training details and limitations are discussed in the paper.

1 Introduction

With the rapid advancement of intelligent manufacturing paradigms, rotating machinery has become integral to a vast array of industrial production lines. The operational integrity of this machinery is intrinsically linked to the reliability and safety of the entire production system. As fundamental components, bearings perform the critical functions of supporting rotors, transmitting loads, and mitigating friction. Empirical evidence indicates that bearing failure constitutes a primary cause of mechanical malfunction. Catastrophic failures precipitated by such defects can incur not only substantial economic losses but also severe safety incidents resulting in injury or loss of life. Consequently, within the contemporary Industry 4.0 framework emphasizing high efficiency and low energy consumption, the capacity for early and precise detection of bearing defects has emerged as a critical technological imperative. By virtue of its intrinsic advantages—including non-contact inspection, low implementation cost, and high throughput—computer vision has emerged as a potent methodology for the inspection of bearing surface defects [1–3]. This technology demonstrates significant potential across numerous applications, including quality control, predictive maintenance, and automated in-line inspection.

Notwithstanding the continual advancements in computer vision, existing methodologies for bearing defect detection continue to confront formidable challenges. Conventional algorithms predicated on handcrafted features, such as manually engineered descriptors for edges, textures, and shapes, struggle to contend with the variability inherent in industrial settings, including fluctuations in illumination, specular reflections, and surface contaminants [4, 5]. While deep learning methodologies have catalyzed significant progress, they are not without their own distinct limitations. Although region-based convolutional neural network (R-CNN) variants [6–8] can effectively identify conspicuous defects like large-area spalling and fissures, they exhibit markedly reduced sensitivity to minute anomalies such as pitting and micro-cracks. Similarly, while algorithms in the YOLO family [9–11] offer the advantage of real-time, end-to-end detection, their constrained feature-representation capacity often leads to an increased incidence of both false positives and false negatives, particularly in scenarios involving densely clustered, fine-grained defects. More recently, Transformer-based architectures [12–14] have demonstrated potential for modeling complex backgrounds by leveraging global self-attention mechanisms; however, their substantial parameter counts and prohibitive computational overhead impede their practical deployment on edge-computing platforms. Collectively, these extant methods exhibit suboptimal performance when confronted with the intertwined challenges of extracting features from minuscule defects against complex textural backgrounds, accommodating multi-scale anomalies, and mitigating interference from metallic reflections and stains. Consequently, they fail to satisfy the stringent, multifaceted requirements of industrial applications, where high accuracy, real-time performance, and operational robustness are simultaneously demanded.

To surmount these challenges, we propose a novel bearing defect detection model derived from a YOLO-based framework. Our model is specifically engineered to address the persistent challenges of discriminating defects from confounding surface textures, achieving precise localization of geometrically irregular anomalies, and maintaining robust detection performance within dynamic industrial environments. By integrating innovative feature-enhancement modules within an optimized network architecture, our approach achieves substantial gains in both detection accuracy and generalization capability across a spectrum of surface anomalies, thereby offering a more effective and reliable solution for automated industrial inspection tasks. The principal contributions of this work are as follows:

1. To address the challenge of extracting features from minute defects embedded within complex textural backgrounds, we designed the LRPAN. This architecture establishes an independent pathway for low-order response aggregation and integrates a CSFFC module. This design facilitates the preservation of rich, fine-grained detail from shallow network strata, thereby substantially enhancing both the extraction and the discriminative power of features associated with minute anomalies.

2. To overcome the challenge of precisely localizing defects with irregular morphologies, we introduce the MSRB. By integrating multiple MSEB sub-modules, the MSRB constructs a hierarchical, cascaded architecture for multi-scale feature processing. This design enables the adaptive modeling of anomalies with complex geometries, such as fissures and spalling, thereby surmounting the inherent limitations of conventional rectangular bounding boxes in a delineating such non-uniform contours.

3. To mitigate the high incidence of false positives arising from specular reflections and surface blemishes on metallic substrates, we devised the SPAA module. The SPAA employs a progressive spatial attention aggregation mechanism coupled with an adaptive threshold modulation strategy. This approach facilitates a robust differentiation between authentic defect signatures and spurious signals originating from environmental artifacts, thereby markedly enhancing the detection system’s robustness and stability within complex industrial settings.

2 Related work

In recent years, the rapid development of deep learning technology has brought revolutionary breakthroughs to the field of defect detection [36, 38, 39]. Detection methods based on deep neural networks [41, 45] have gradually become the mainstream technological approach in this field. Differentiated by their network architectures and detection paradigms, these contemporary methods can be broadly categorized into two principal classes: (i) Transformer-based approaches that leverage self-attention mechanisms, and (ii) single-stage, regression-based detection algorithms. In this section, we systematically review the technological trajectory, pivotal innovations, and persistent challenges associated with each of these two paradigms as applied to defect detection tasks.

2.1 Transformer-based defect detection methods

By virtue of their powerful global modeling capabilities and inherent self-attention mechanisms, Transformer architectures are demonstrating distinct advantages within the domain of industrial defect detection. These frameworks facilitate the capture of long-range dependencies between anomalous regions and their surrounding context, thereby offering a novel technological pathway for defect identification within complex industrial settings. Zhang et al. [15], for instance, pioneered the application of the Vision Transformer (ViT) to the detection of surface defects on steel plates. In their approach, an input image is partitioned into a sequence of fixed-size patches, and the self-attention mechanism is subsequently employed to establish global correlations among them. This strategy significantly enhanced the accuracy of defect identification against intricate textural backgrounds. The model achieved exemplary performance on the NEU-DET dataset, substantiating the potential of Transformer architectures for effectively processing complex industrial surface textures.

The advent of the DEtection TRansformer (DETR) architecture and its variants has further propelled advancements in this domain. Fang et al. [16], for instance, developed a modified DETR model for fabric defect inspection. Their model incorporated multi-scale feature fusion and optimized positional encoding, which effectively addressed the challenge of identifying irregularly shaped defects on textile surfaces. In a similar vein, Ji et al. [17] adapted the Deformable DETR for the inspection of printed circuit boards. The deformable attention mechanism enabled the model to selectively focus on salient regions of interest, leading to a marked improvement in the detection accuracy of minute soldering defects. Collectively, these studies underscore the distinct advantages of the Transformer’s global modeling capabilities for resolving industrial defects characterized by irregular morphologies and scale variations. Addressing the imperative for real-time performance, researchers have also engineered several computationally efficient Transformer-based solutions. Wu et al. [18] constructed a system for detecting blade surface defects using RT-DETR. By leveraging a hybrid encoder design and optimizing query selection, their system substantially reduced computational overhead without compromising detection accuracy, facilitating its deployment for real-time, in-line inspection. Furthermore, Wu et al. [19] proposed a lightweight defect detection model based on the Swin Transformer. This model achieved high computational efficiency on resource-constrained edge devices through the implementation of hierarchical windowed attention and the fusion of feature pyramids.

Nonetheless, the direct application of Transformer-based methods to the specific domain of bearing defect detection is fraught with challenges. For instance, while Ji et al. [20] adapted the Vision Transformer (ViT) for identifying defects on bearing raceways, their model—despite performing capably on large-scale defects—exhibited markedly diminished sensitivity to minute anomalies such as pitting and superficial scratches. This limitation was primarily attributed to the ViT’s rigid patch partitioning strategy, which struggles to accommodate the periodic textural features characteristic of bearing surfaces and is consequently prone to misclassifying normal machining marks as genuine defects. Similarly, a DETR-based system developed by Liu et al. [21] demonstrated excellent performance in processing irregular cracks; however, its substantial parameter count and high computational complexity have hindered its widespread adoption in practical industrial settings. Furthermore, a broader challenge facing extant Transformer models is their characteristically slow training convergence and high sensitivity to small datasets, making it difficult to fully exploit their powerful modeling capabilities in scenarios where annotated bearing defect data are inherently scarce [22–24].

Recent studies by Zhang et al. [36] and Xu et al. [37] have proposed Transformer-based defect detection methods, further validating the potential of the Transformer architecture in complex industrial environments. Qiao et al. [40] introduced a self-supervised sensor feature extraction network—Multi-Head Attention Self-Supervised (MAS) representation model, applying a self-supervised contrastive learning method using positive samples for anomaly detection in multidimensional industrial sensor data. Wang et al. [42] proposed a physically interpretable Wavelet-guided Network (WaveGNet) for Machine Intelligence Fault Prediction (MIFP), expanding the feature learning space of CNN through deep frequency separation. Wang et al. [47] utilized a cross-modal fusion module based on a dual multi-head cross-attention mechanism (Dual-MCM) to achieve collaborative interaction of cross-modal information, completing bidirectional deep collaborative representation of internal and external signal features in the fusion process of the robot.

2.2 YOLO-based defect detection methods

Algorithms within the You Only Look Once (YOLO) family have been extensively applied and investigated in the domain of industrial defect detection, primarily owing to their exceptional real-time performance and end-to-end detection architecture. These methods employ a unified regression framework to directly predict object locations and class probabilities in a single pass, thereby obviating the need for complex post-processing stages. This characteristic renders them eminently suitable for industrial applications where high inspection throughput is a critical requirement.

In defect detection applications within the steel industry, YOLO-based methods have demonstrated considerable efficacy. Jing et al. [25] developed a system for detecting surface defects on hot-rolled steel plates using YOLOv3. Through data augmentation and multi-scale training strategies, they effectively enhanced the detection accuracy for typical defects such as oxide scale and cracks. This system achieved detection latencies on the order of milliseconds in an operational production line, satisfying the real-time monitoring demands of high-speed rolling processes. Li et al. [26] applied a modified YOLOv4 to the surface quality inspection of cold-rolled steel strips, incorporating an attention mechanism and a focal loss function to markedly improve the identification of minute scratches and punctate defects. Furthermore, a steel pipe defect detection system built on YOLOv5 by Duman et al. [27] utilized a lightweight network design, facilitating deployment on mobile platforms without a significant trade-off in performance and thus providing a viable solution for in-line quality inspection.

YOLO-based approaches have also yielded significant advancements in electronics manufacturing. Li et al. [28] applied YOLOv3 to the inspection of printed circuit boards, mitigating the issue of false negatives in environments with high component density by employing multi-layer feature fusion and an improved non-maximum suppression algorithm. A solder joint quality inspection system developed by Zhang et al. [29], based on YOLOv8, substantially enhanced detection accuracy across various solder defect sizes by introducing deformable convolutions and a multi-scale receptive field enhancement module. Research in the textile industry has similarly leveraged the technical strengths of YOLO. Li et al. [30] proposed a fabric defect detection method using an enhanced YOLOv5 framework. By designing an adaptive anchor box generation strategy and a multi-scale feature enhancement module, their approach effectively contended with challenges posed by complex fabric textures and diverse defect types. The method achieved exemplary performance across multiple textile defect datasets, providing a robust technological foundation for the automated quality control of textiles.

However, in the specific application of bearing defect detection, YOLO-based methods confront a distinct of technical hurdles. A system for bearing raceway inspection constructed by Xing et al. [31] based on YOLOv3, while excellent in terms of detection speed, exhibited limited accuracy in identifying minute pitting and shallow scratches. This limitation is primarily attributed to the difficulty of standard convolutional operations in effectively extracting the fine-grained textural features of bearing surfaces. While Ding et al. [32] improved the feature extraction network of YOLOv8 by incorporating multi-scale dilated convolutions and a channel attention mechanism to enhance performance on bearing inner ring defects, its robustness remained insufficient when confronted with complex illumination conditions and surface contamination.

Furthermore, Xu et al. [37] proposed a novel lightweight information-enhanced fusion network (IEFNet) for anomaly detection in hydroturbine operational sounds. A filter bank computes the sound tensor, which serves as input to the IEFNet feature extraction module. Sound features are extracted through residual block convolutions, and an attention mechanism is used in the feature enhancement fusion module to combine sound features with load information. Li et al. [43] proposed the YOLOv8-GhostConv-SEV2 model based on the lightweight YOLOv8n framework. This model optimizes feature extraction by introducing the GhostConv module and enhances noise suppression capabilities using the SEV2 (Squeeze-and-Excitation Version 2) attention mechanism. Shen et al. [44] extracted multi-scale defect features through the MFE module, optimized feature fusion using the LGFA module, and applied the HDD mechanism to transform detection into a denoising process, thereby reducing prior dependence. Experiments showed that their method improved detection accuracy by 6.1% over specialized methods and adapted well to complex detection scenarios. Wan et al. [46] proposed the FMD-MCNN fault diagnosis method. Vibration signals from the auxiliary gearbox are first collected, then processed by FMD decomposition, reconstruction, and normalization preprocessing. The signals are then input to the MCNN for multi-scale feature extraction and fusion, with fault recognition completed through a softmax classifier.

Extant YOLO-based methodologies [33–35], when applied to bearing defect detection, are encumbered by several key technical bottlenecks. First, conventional feature extraction backbones struggle to effectively discriminate between the benign, periodic textures of the bearing surface and genuine anomalous defects, a limitation that contributes to a high false-positive rate. Second, the reliance on rectangular bounding boxes is fundamentally inadequate for precisely delineating the contours of morphologically irregular defects, such as fissures and spalls. Third, conventional feature fusion strategies often operate at a limited scale, failing to concurrently satisfy the distinct detection requirements of both minute pitting and extensive surface flaws. These persistent challenges collectively delineate a clear trajectory for research and provide significant scope for innovation, particularly for technical advancements built upon the latest generation of the YOLO architecture.

3 Methodology

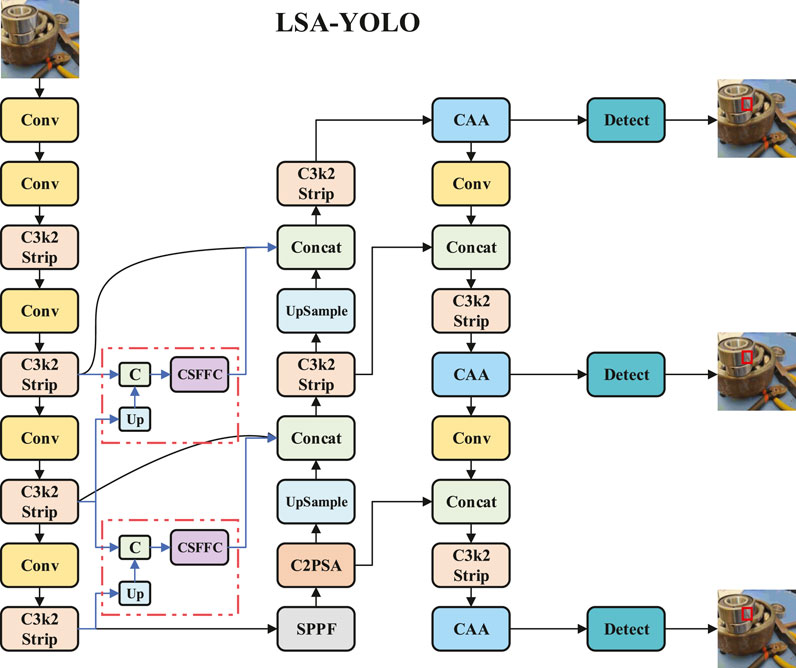

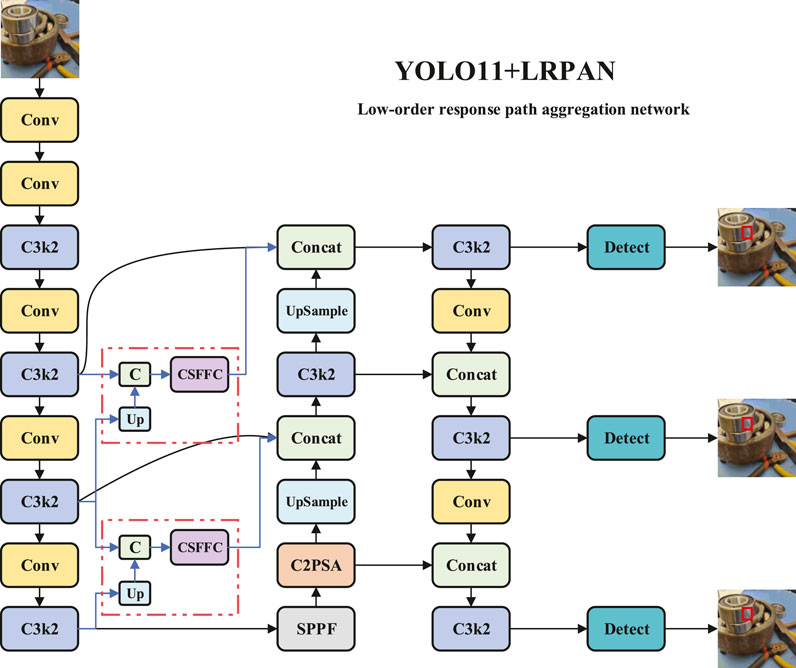

This paper proposes an improved network architecture for bearing defect detection, named LSA-YOLO, with its overall framework illustrated in Figure 1. LSA-YOLO is deeply optimized based on the YOLOv11 architecture, integrating the advantages of multi-scale feature aggregation and attention mechanisms. Furthermore, it incorporates innovative modules specifically designed to address the unique challenges in bearing defect detection, including core technologies for extracting minute defect features under surface texture interference, accurately locating irregularly shaped defects, and suppressing interference from metal surface reflections and stains.

The input image initially undergoes hierarchical feature extraction through a backbone network, generating multi-scale feature maps at different semantic levels. These feature maps contain rich visual information ranging from fine-grained surface textures to high-level semantics, providing a solid representational foundation for subsequent defect detection tasks. The backbone network utilizes MSRB modules instead of conventional C3k2 modules, achieving effective extraction and enhancement of multi-scale features through the integration of MSRB units, which significantly improves the modeling capability for irregularly shaped defects.

To address the challenge of extracting minute defect features from bearing surfaces against complex textural backgrounds, LSA-YOLO introduces the LRPAN module. LRPAN effectively preserves feature representations containing rich detail information from shallow network layers by constructing independent low-order response paths. Additionally, it implements frequency domain feature enhancement through the CSFFC module, establishing dedicated channels from intermediate layers of the backbone network to the feature fusion network. This design ensures the effective preservation of minute defect features throughout their propagation process in deep network layers.

In the feature fusion stage, the network employs an improved FPN structure, which significantly reduces interference from surface textures and enhances the discriminative expressive capability of defect features in complex industrial environments through deep fusion of multi-scale features. To further enhance robustness against interference from metal surface reflections and stains, LSA-YOLO integrates the SPAA module at each detection scale. SPAA effectively distinguishes genuine defect features from environmental interference signals through a progressive spatial attention aggregation mechanism, significantly improving detection stability in complex industrial settings via multi-directional spatial convolution and adaptive weight modulation. The optimized multi-scale feature representations are ultimately processed through a decoupled detection head to accomplish object bounding box regression and category classification tasks. The detection head achieves specialized feature processing through independent classification and regression branches, outputting precise defect location and category information. Through this meticulously designed modular architecture, LSA-YOLO significantly enhances the detection performance of various surface defects on bearings while maintaining real-time detection capabilities, providing a reliable technical solution for practical applications such as industrial quality control and equipment predictive maintenance.

3.1 LRPAN

The conventional YOLOv11 network, when processing bearing surface defect detection, tends to confuse normal processing marks with actual defects due to its standard feature fusion strategy that primarily relies on high-level semantic information. When confronted with complex periodic textural backgrounds on bearing surfaces, the effective information of minute defect features is gradually lost during propagation through deep network layers. To address this critical issue, this paper proposes an innovative network architecture named LRPAN, specifically designed to enhance the extraction and preservation capabilities of minute defect features on bearing surfaces. As shown in Figure 2, LRPAN effectively preserves feature representations containing rich detailed information from shallow network layers by constructing independent low-order response paths.

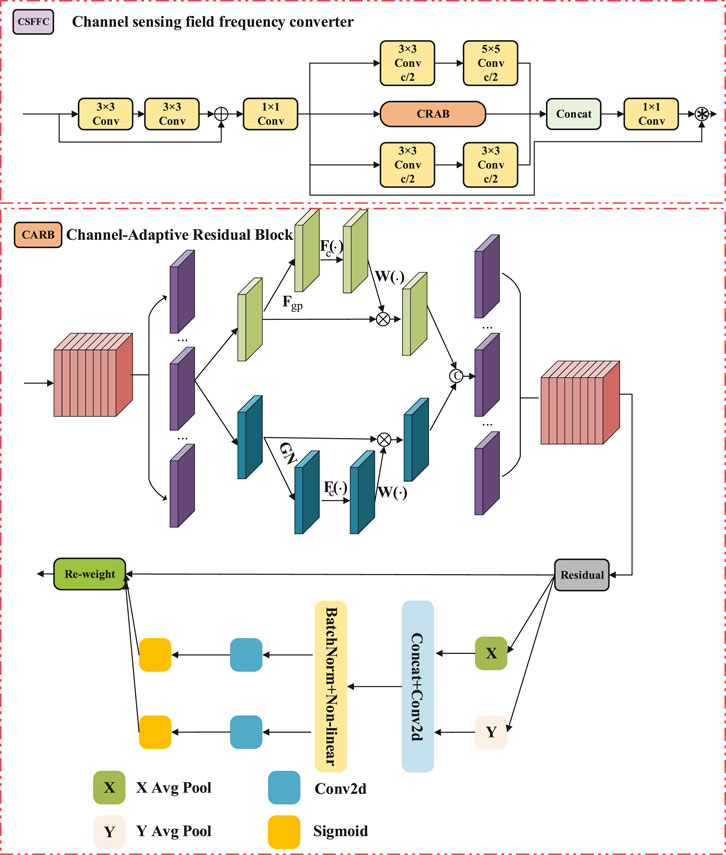

Furthermore, through the incorporation of the CSFFC module, it achieves frequency domain feature enhancement, significantly improving the recognition accuracy of minute defects against complex textural backgrounds. The core concept of the LRPAN network structure is to incorporate dedicated low-order response aggregation channels in addition to the conventional top-down feature fusion pathway, as illustrated in Figure 2. This architecture initially extracts low-order feature responses from the intermediate layer feature maps (P4 and P3 layers) of the backbone network, establishing cross-scale feature associations through upsampling operations. The LRPAN module aggregates low-level response paths to retain the detailed information from the shallow layers of the network. Its output is used for subsequent feature fusion. Specifically, the feature aggregation process of LRPAN can be formulated as Equation 1:

where,

where,

The frequency-domain operations in this module play a crucial role in enhancing defect feature expression by focusing on periodic patterns in the data. Frequency-domain convolution, as part of this transformation, effectively captures global periodic characteristics, which is particularly beneficial when dealing with periodic textures and fine defects. This ability significantly improves the model’s robustness in detecting defects under complex backgrounds.

To further enhance the adaptability of feature expression, the CSFFC module integrates a Channel-Adaptive Residual Block (CARB) unit, which achieves adaptive feature adjustment through a dual-path channel reweighting mechanism. The dual-path multiplication is employed to integrate features from two parallel processing branches: one focusing on high-frequency components and the other on low-frequency components. This allows the model to simultaneously capture fine-grained, high-resolution details along with global, coarse patterns. The two paths are combined through learnable weights, which are adaptive to the importance of each channel’s contribution. The channel attention weight calculation formula for CARB as shown in Equation 4:

where,

The final feature fusion process is achieved through multi-scale feature aggregation, deeply integrating the output of the low-order response path with the traditional FPN path, as shown in Equation 5:

where,

As shown in Figure 3, the LRPAN network effectively addresses the insufficient feature expression problem of traditional YOLOv11 in detecting minor defects on bearing surfaces by constructing an independent low-order response aggregation path and introducing the frequency-domain-aware CSFFC module. This structure not only maintains the real-time advantages of the original network but also significantly enhances the recognition capability of minor defects against complex texture backgrounds, providing more reliable and precise technical support for bearing quality inspection. The innovative design of LRPAN enables the network to achieve comprehensive capture and effective utilization of multi-scale defect features without significantly increasing computational overhead.

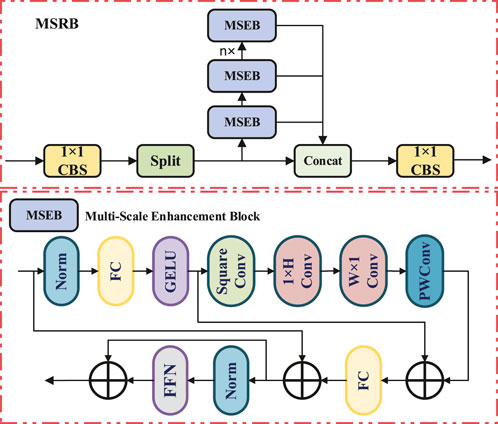

3.2 MSRB

The traditional YOLOv11 network, when processing bearing defect detection, primarily uses fixed convolution kernel sizes in its standard C3k2 module for feature extraction. When faced with irregularly shaped bearing defects such as cracks and spalling, it lacks adaptive modeling capability for multi-scale spatial geometric features, resulting in insufficient boundary localization accuracy and difficulty in accurately describing the true contour shape of defects. To address this critical issue, this paper proposes an innovative module named MSRB, specifically designed to enhance the network’s precise localization capability for irregularly shaped defects. By integrating multiple MSEB submodules, MSRB constructs a hierarchical cascaded multi-scale feature processing architecture that can effectively capture geometric shape information at different spatial scales, significantly improving the precise localization performance for complex-shaped defect boundaries.

The core design of the MSRB module lies in achieving adaptive modeling of irregular defect shapes through a multi-scale feature decomposition and recombination mechanism, as shown in Figure 4. The module first performs channel-wise standardization processing on the input features through

where,

MSEB, as the core submodule of MSRB, adopts a progressive multi-scale convolution strategy to capture shape features at different granularities. Through a carefully designed processing chain of Norm

where

To further bolster the model’s capacity for representing irregular morphologies, the Multi-Scale Enhancement Block (MSEB) module incorporates an adaptive spatial weight modulation mechanism. This mechanism learns the relative importance of different spatial locations, which in turn facilitates a shape-sensitive feature enhancement process. The weight calculation for this mechanism is formulated as shown in Equation 9:

where

This function is designed to capture the interdependencies between local and global features by performing a global context extraction process, which is then fused with the spatial features. It enhances the model’s ability to detect defects, particularly in complex backgrounds where contextual understanding is necessary to distinguish between actual defects and background noise. The output of this function is combined with the spatial features in Equation 9 to adaptively adjust the channel weights for better feature expression.

By introducing

The final output of the Multi-Scale Enhancement Block (MSEB) is generated via a multi-path feature fusion process, which involves a weighted combination of feature representations from different scales as shown in Equation 11:

where

3.3 SPAA (spatial progressive attention aggregation)

The standard attention mechanism within the conventional YOLO framework, when applied to bearing defect detection, primarily relies on global feature statistics to generate attention weights. This approach exhibits a limited capacity for adaptive perception of the local spatial environment. Consequently, when confronted with the complex illumination changes and surface contaminants characteristic of metallic bearing surfaces, the network is susceptible to being confounded by regions of high specular reflection and superficial blemishes, which impairs the accurate identification of true defect features. To overcome this critical limitation, we introduce an innovative module termed SPAA, specifically engineered to enhance the network’s robustness against such interference. As illustrated in Figure 5, the SPAA module institutes a progressive spatial attention aggregation mechanism that facilitates a robust differentiation between authentic defect signatures and spurious signals arising from environmental artifacts. This is achieved through multi-directional spatial convolutions and adaptive weight modulation, which collectively enhance detection stability substantially in complex industrial settings.

The core design principle of the SPAA module is the effective suppression of interference signals via a progressive aggregation of spatial information, as depicted in Figure 5. The process commences with a global average pooling operation to extract global contextual information from the input feature map. Subsequently, a

where

To more effectively process the direction-specific textural features characteristic of bearing surfaces, the SPAA module incorporates a direction-sensitive spatial convolution strategy. This strategy employs distinct, strip-like convolutional kernels for the vertical and horizontal axes, enabling the model to capture textural variation patterns along these discrete orientations effectively. The feature enhancement process along the vertical axis can be formulated as shown in Equation 13:

where

where

The SPAA module further incorporates an adaptive threshold modulation mechanism to enhance suppression capability against interference signals. This mechanism dynamically adjusts attention thresholds by learning statistical characteristics of input features, computed as shown in Equation 15:

where

The SPAA module uses the Progressive Spatial Attention Aggregation mechanism to distinguish between real defects and interference signals. The final output

where

In Equation 16, the adaptive threshold mechanism dynamically defines an adaptive threshold

The theoretical foundation of the adaptive threshold mechanism is based on statistical principles such as mean and standard deviation. By calculating the mean and standard deviation of the feature map

By leveraging its progressive spatial attention aggregation and adaptive threshold modulation mechanisms, the SPAA module effectively addresses the insufficient robustness of conventional attention mechanisms when confronted with specular reflections and surface blemishes on metallic components. This architecture not only accurately identifies and suppresses a variety of environmental interference signals but also augments its sensitivity to authentic defect signatures through its direction-sensitive convolutional design. The innovative design of the SPAA module therefore enables the network to maintain stable detection performance amidst the complexities of industrial environments, which substantially enhances the practicality and reliability of the overall bearing defect detection system. This provides a crucial technical safeguard for its practical deployment in industrial settings.

4 Experimental results and analysis

4.1 Dataset and experimental setup

4.1.1 Dataset description

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed LSA-YOLO model for bearing defect detection, we conducted experiments using a purpose-built bearing surface defect dataset. The dataset comprises three typical types of bearing surface defects—grooves (aocao), abrasions (cashang), and scratches (huahen)—which cover the most common bearing quality issues encountered in real industrial production. All images were collected from actual industrial environments and exhibit rich sample diversity and high annotation accuracy.

The dataset contains a total of 6,542 high-quality images, with all images standardized to a resolution of 640

The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets at an approximate ratio of 7:1:1: the training set contains 5,106 images for parameter learning and feature representation; the validation set contains 718 images for hyperparameter tuning and training monitoring; and the test set contains 718 images for final performance evaluation and comparative analysis. This partitioning strategy ensures both sufficient training and reliable evaluation results. Due to the restrictions of the original license, we do not redistribute the dataset. Researchers can reproduce the experiments by obtaining the original data and using the accompanying file list, split index, and preprocessing scripts provided in this manuscript. For academic purposes, access support can also be requested through the corresponding author with a reasonable request.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the defect samples within the dataset exhibit a significant class imbalance, a characteristic that mirrors the differential occurrence rates of various defect types in real-world industrial scenarios. The defect classes are defined as follows: Grooves, which typically manifest as localized depressions on the bearing surface with relatively regular geometries; Abrasions, which primarily present as linear or striate patterns of surface damage, often exhibiting pronounced directionality; and Scratches, which appear as amorphous surface markings with complex and often ill-defined boundaries. Furthermore, the dataset incorporates images captured under varied illumination conditions and against diverse textural backgrounds, replete with varying degrees of specular reflection and surface contaminants. These factors introduce substantial technical challenges for detection algorithms and thereby more faithfully simulate the complexities of authentic industrial inspection environments.

To address the class imbalance issue present in the dataset, we employed a class weighting strategy during training by adjusting the weights of each class in the loss function. Specifically, categories with fewer samples (such as abrasions and scratches) were assigned higher weights in the loss function to reduce the model’s bias toward the more frequent categories (such as grooves). Additionally, to further improve the model’s performance across all classes, we applied oversampling and undersampling methods to adjust the distribution of the training data. These strategies effectively mitigated the negative impact of class imbalance on model training, ensuring that the model could learn from the minority class samples effectively and improve overall detection performance.

4.1.2 Experimental setup

All experiments in this study were conducted on a high-performance computing platform equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU (24GB VRAM), Intel Core i9-12900K CPU, and 64GB DDR4 RAM. The experiments used the PyTorch 1.12.0 deep learning framework, together with CUDA 11.6 and cuDNN 8.3.2 acceleration libraries, to ensure efficient model training and inference. All experiment codes were run in the Windows 11 operating system environment, with Python 3.8 as the programming language. During model training, all input images were uniformly resized to a resolution of 640

To enhance the model’s generalization ability, various data augmentation methods were applied during training, including random horizontal flipping (probability 0.5), random rotation (

4.2 Dataset analysis

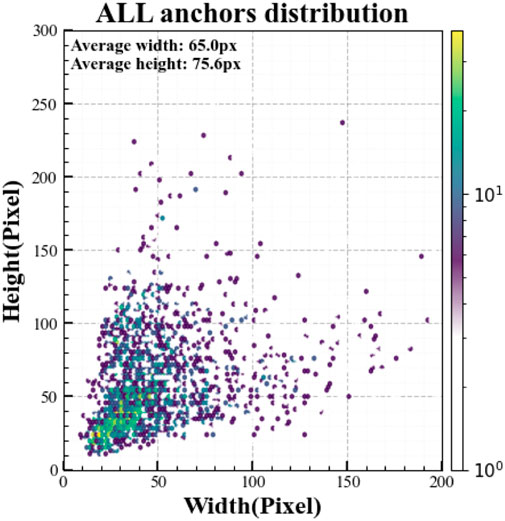

As depicted in Figure 7, the distribution of bounding box widths and heights within the dataset exhibits distinct clustering patterns. The majority of targets are concentrated within a width range of 0–80 pixels and a height range of 0–120 pixels, underscoring a prevalence of small-scale objects. The mean bounding box width is 65.0 pixels and the mean height is 75.6 pixels, indicating that defects on bearing surfaces typically manifest as small, irregularly shaped regions. Concurrently, the presence of instances with dimensions exceeding 150 pixels indicates that the dataset also contains a representative sample of medium- and large-scale defects. This distributional characteristic imposes stringent requirements on the detection algorithm. On one hand, the model must possess high sensitivity to small objects to prevent false negatives (missed detections). On the other hand, it must demonstrate robust multi-scale adaptability to ensure the accurate detection of larger defects. Accordingly, our algorithmic design incorporates low-level response aggregation and a multi-scale residual architecture, a strategy intended to enhance overall detection performance across a range of defect scales while preserving a strong capacity for small-object detection.

4.3 Comparative experiments

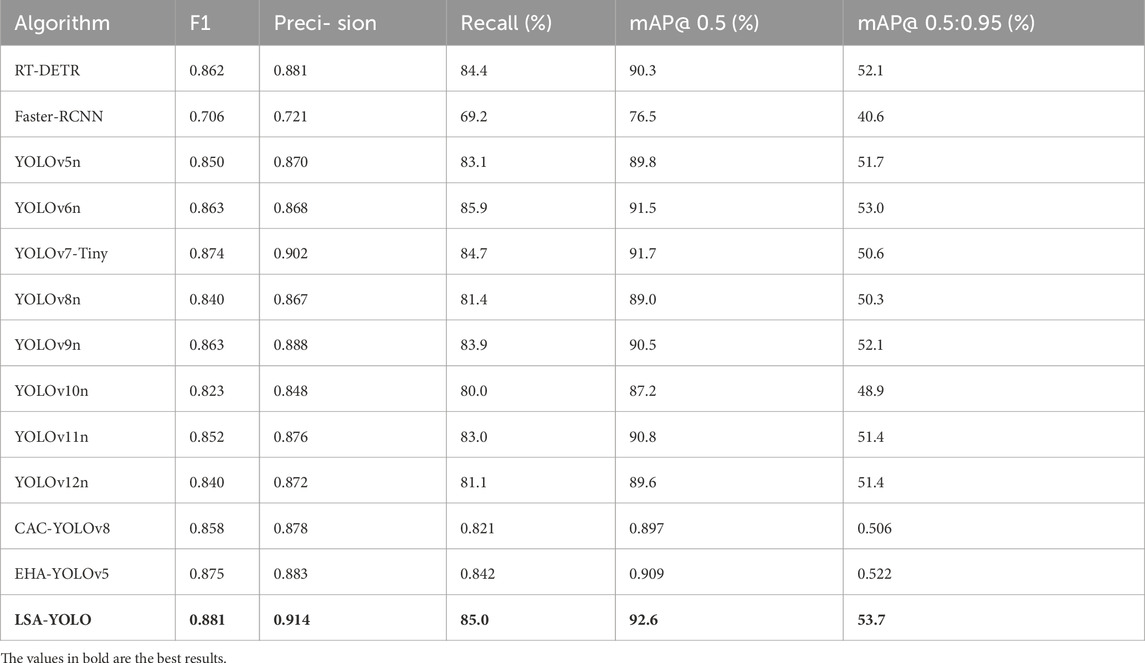

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of LSA-YOLO on the task of bearing surface defect detection, we benchmarked it against ten representative detection methods using five standard evaluation metrics: F1-score, Precision, Recall, mAP@0.5, and mAP@0.5:0.95. The baseline models included two general-purpose detectors (RT-DETR and Faster R-CNN) and eight lightweight algorithms from the YOLO series (YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-Tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9n, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, and YOLOv12n). The experimental results, detailed in Table 1, demonstrate that LSA-YOLO achieved the highest performance across all evaluated metrics, attaining an F1-score of 0.881, a Precision of 0.914, a Recall of 0.850, an mAP@0.5 of 0.926, and an mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.537. Relative to the next-best performing model, YOLOv7-Tiny, LSA-YOLO demonstrated an improvement of 0.7–3.1 percentage points across these metrics. When compared to the YOLOv5n baseline, our model achieved a more substantial improvement, ranging from 1.9 to 4.4 percentage points. This underscores its superior, well-rounded performance in both detection completeness (recall) and localization precision.

Among the general-purpose detectors, RT-DETR exhibited a relatively balanced precision and recall, with a Precision of 0.881, Recall of 0.844, F1-score of 0.862, and mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 reaching 0.903 and 0.521, respectively. Although its Transformer-based global feature modeling mechanism ensures strong detection stability, its bounding box localization accuracy at high IoU thresholds still falls short of LSA-YOLO, lagging by 1.6 percentage points on mAP@0.5:0.95. This indicates that LSA-YOLO holds an advantage in multi-scale detail modeling and complex defect localization.

In contrast, the overall performance of Faster R-CNN was significantly poorer, with a Precision of 0.721, Recall of 0.692, F1-score of 0.706, and mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.765 and 0.406, respectively—a gap of 13–19 percentage points compared to LSA-YOLO. This result reveals that traditional two-stage detectors are prone to missed detections and false positives in scenarios involving minute defects and strong interference. LSA-YOLO, through the introduction of progressive spatial attention aggregation and multi-scale residual blocks, effectively suppresses interference from metal surface reflections and stains, thereby enhancing its ability to localize irregularly shaped defects.

To verify the performance difference between the YOLO11n and LSA-YOLO models, we conducted an independent sample t-test. The results showed a p-value of 0.03, indicating a statistically significant difference in F1 scores between the two models. Specifically, the F1 score of the LSA-YOLO model is significantly higher than that of YOLO11n, demonstrating that LSA-YOLO performs better in the defect detection task.

In summary, the performance advantages of LSA-YOLO primarily stem from the synergistic effect of its innovative designs. The LRPAN network structure preserves rich shallow-layer details through its low-order response path and channel-aware modules. The MSRB module enhances multi-scale feature representation and the ability to model complex geometric defects, while the SPAA module significantly improves the model’s robustness in interference-prone scenarios. These improvements not only surpass existing methods on individual metrics but, more importantly, maintain a leading edge under the strict mAP@0.5:0.95 evaluation standard, validating its broad applicability and engineering value in industrial defect detection.

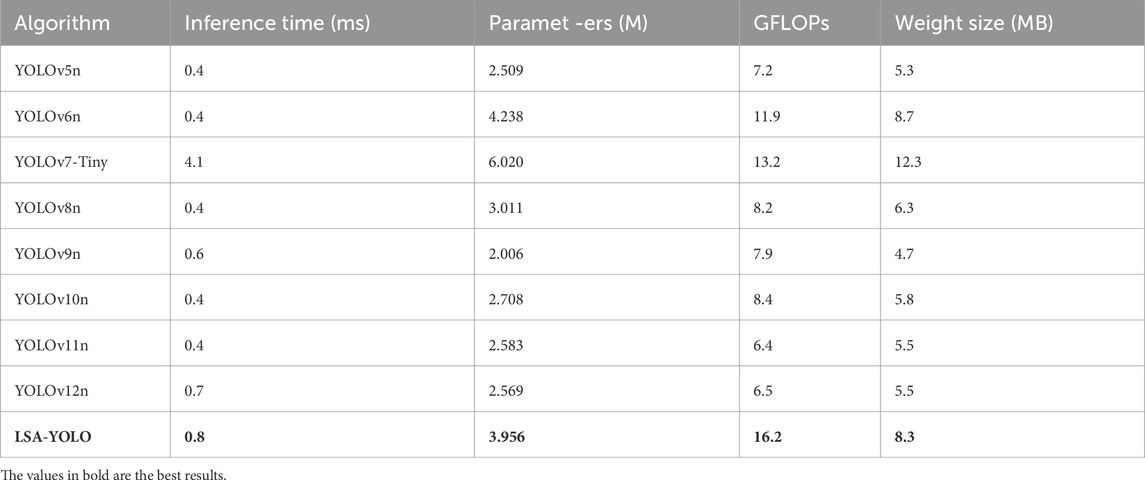

Based on the computational complexity and inference efficiency analysis in Table 2, the LSA-YOLO model significantly improves detection accuracy by introducing three innovative modules: LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA. Specifically, the model’s parameter count increases to 3.956 million, with GFLOPs reaching 16.2 and a model size of 8.3MB. This is in contrast to the lighter YOLOv5n (2.509 million parameters, 7.2 GFLOPs) and YOLO11n (2.583 million parameters, 6.4 GFLOPs), which have relatively lower computational costs. However, the inference time of LSA-YOLO is only 0.8 m, which, although slightly higher than models like YOLOv6, YOLOv8, and YOLOv10 (with 0.4 m inference time), represents a minimal increase and is fully acceptable, especially given the high detection accuracy it maintains. Further analysis shows that the LSA-YOLO model achieves an mAP@0.5 of 92.6%, which is 2-3 percentage points higher than other baseline models. This result indicates that, despite the increased computational complexity, the accuracy improvement is significant, demonstrating the potential of LSA-YOLO in handling complex industrial scenarios. Particularly in tasks like bearing defect detection, LSA-YOLO effectively balances computational cost and detection accuracy, meeting the dual demands of precision and real-time performance in practical applications.

Overall, by optimizing the model architecture, LSA-YOLO successfully enhances both accuracy and robustness while making reasonable compromises in computational cost. Although the increase in parameters and GFLOPs may lead to higher hardware requirements, the increase in inference time is only 0.4 m, still meeting the real-time detection needs of industrial environments. Therefore, considering its advantages in detection accuracy and real-time inference, LSA-YOLO holds significant potential for applications in industrial defect detection and other fields.

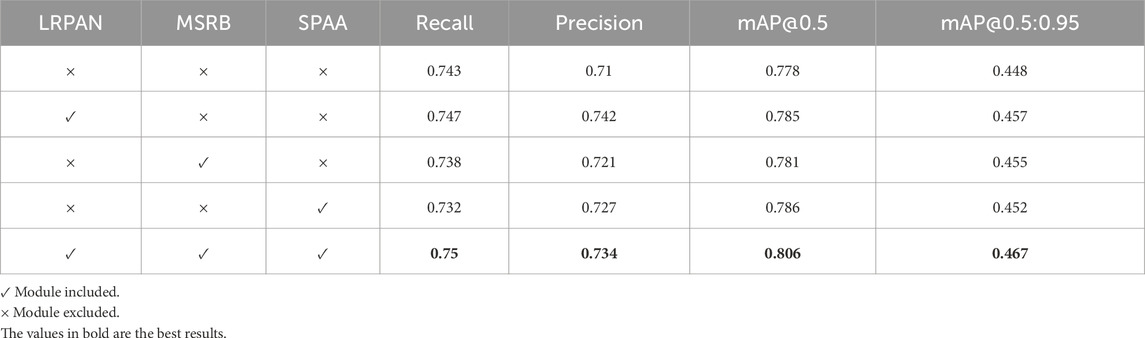

4.4 Ablation studies

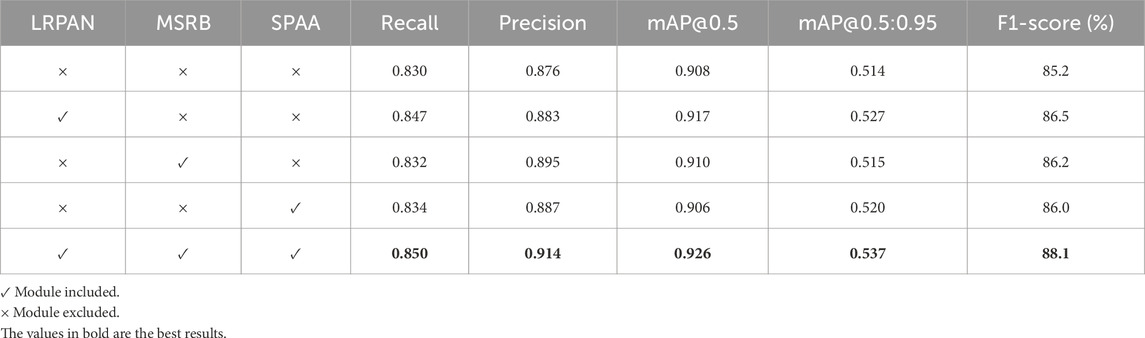

To thoroughly analyze the effectiveness of each core module in LSA-YOLO and their synergistic mechanisms, a systematic ablation study was designed. By progressively introducing the LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA modules, we quantitatively assessed the contribution of each component to the overall performance and verified their collaborative enhancement effects. The baseline YOLO network served as the reference model, evaluated on the bearing surface defect dataset by examining key metrics such as Recall, Precision, mean Average Precision (mAP), and F1-score.

As shown in Table 3, the ablation results clearly demonstrate the individual contributions and synergistic effects of each module. In the baseline configuration (no modules enabled), the model achieved a Recall of 83.0%, Precision of 87.6%, mAP@0.5 of 90.8%, mAP@0.5:0.95 of 51.4%, and an F1-score of 85.2%.

When the LRPAN network was introduced alone, performance improved significantly: Recall increased to 84.7% (+1.7%), Precision to 88.3% (+0.7%), mAP@0.5% to 91.7% (+0.9%), mAP@0.5:0.95% to 52.7% (+1.3%), and the F1-score to 86.5% (+1.3%). This result fully validates the effectiveness of LRPAN in preserving detail information and enhancing the extraction of minute defect features through its low-order response aggregation path and CSFFC module.

The standalone introduction of the MSRB module also led to performance gains, particularly in Precision, which rose from 87.6% to 89.5% (+1.9%), with mAP@0.5 reaching 91.0% (+0.2%) and the F1-score increasing to 86.2% (+1.0%). This indicates that MSRB’s multi-scale cascaded architecture effectively enhances the model’s ability to recognize irregularly shaped defects, thereby reducing the false positive rate. The SPAA module’s primary contribution was in improving anti-interference capabilities, raising Precision to 88.7% (+1.1%), mAP@0.5:0.95% to 52.0% (+0.6%), and the F1-score to 86.0% (+0.8%), proving its effectiveness in distinguishing true defects from environmental noise.

When all three modules were integrated, LSA-YOLO exhibited a remarkable synergistic effect. The fully configured model achieved a Recall of 85.0%, Precision of 91.4%, mAP@0.5 of 92.6%, mAP@0.5:0.95 of 53.7%, and an F1-score of 88.1%. Compared to the baseline, these figures represent improvements of 2.0%, 3.8%, 1.8%, 2.3%, and 2.9%, respectively. Notably, the performance increase of the complete model significantly exceeds the simple sum of the individual modules’ contributions, indicating a strong synergy between LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA. LRPAN provides high-quality detailed features that lay the foundation for MSRB’s multi-scale processing. The attention aggregation mechanism of SPAA further enhances the discriminative power of these multi-scale features. Together, they form a complete technical chain from feature extraction and multi-scale adaptation to attention enhancement, achieving a comprehensive improvement in bearing defect detection performance.

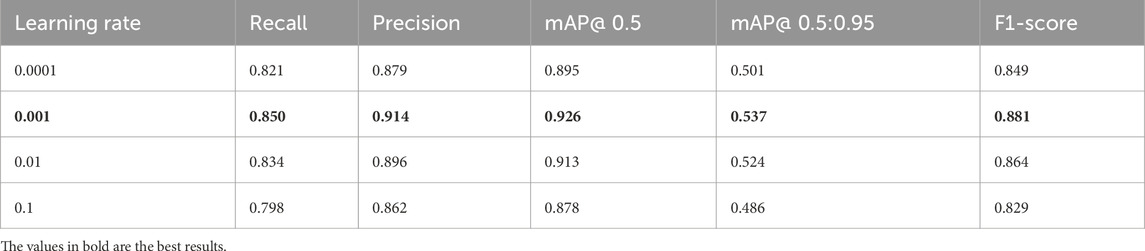

4.5 Learning rate experiment

The learning rate is a critical hyperparameter that directly influences the convergence speed and final performance of the model. To determine the optimal learning rate for the bearing defect detection model, we conducted comparative experiments with four values: 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, and 0.1. All other hyperparameters were kept constant (batch size = 32, epochs = 200, optimizer = Adam). The results are shown in Table 4.

The experimental results show that the choice of learning rate has a significant impact on the performance of the LSA-YOLO model. With a learning rate of 0.0001, the model converged too slowly, failing to fully learn the data’s underlying patterns after 200 epochs. All metrics were at a low level: Recall was 82.1%, Precision was 87.9%, mAP@0.5 was 89.5%, mAP@0.5:0.95 was 50.1%, and the F1-score was 84.9%.

When the learning rate was set to 0.001, LSA-YOLO achieved its optimal performance, with all evaluation metrics reaching their peak values: Recall at 85.0%, Precision at 91.4%, mAP@0.5 at 92.6%, mAP@0.5:0.95 at 53.7%, and an F1-score of 88.1%. At this learning rate, the model achieved sufficient parameter optimization while maintaining a good convergence speed, allowing the three core modules (LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA) to function optimally and effectively balancing the model’s learning capacity and generalization performance.

Increasing the learning rate to 0.01 resulted in a slight decline in performance, with Recall at 83.4%, Precision at 89.6%, mAP@0.5 at 91.3%, mAP@0.5:0.95 at 52.4%, and an F1-score of 86.4%. This suggests that the faster parameter updates began to affect the model’s stable convergence.

When the learning rate was further increased to 0.1, the large update steps led to an unstable training process and a significant drop in performance. Recall fell to 79.8%, Precision to 86.2%, mAP@0.5% to 87.8%, mAP@0.5:0.95% to 48.6%, and the F1-score was only 82.9%. This demonstrates that an excessively high learning rate disrupts the model’s convergence, causing parameters to oscillate around the optimal solution without effectively converging. In conclusion, a learning rate of 0.001 is the optimal choice for LSA-YOLO in the bearing defect detection task. This setting ensures that the model achieves the best detection performance within a reasonable training time, providing an important hyperparameter reference for subsequent industrial deployment.

4.6 Testing in a new scene for generalization

To evaluate the generalization ability of the proposed LSA-YOLO model in new scenarios, we conducted experiments on the widely used benchmark dataset, NEU-DET. The NEU-DET dataset contains a variety of defect types and presents considerable challenges, making it an ideal choice for assessing the model’s adaptability to unseen data.

In this section, we performed an ablation study to analyze the performance of the LSA-YOLO model on the NEU-DET dataset. The main objective of the ablation study was to evaluate the contributions of the key components in the LSA-YOLO architecture, including the Low-level Response Path Aggregation Network (LRPAN), Multi-Scale Enhancement Block (MSRB), and Stepwise Spatial Attention Aggregation (SPAA) modules. By systematically removing or modifying these components, we comprehensively assessed their impact on the overall performance and examined how they affected defect detection accuracy in unseen data.

Ablation Study Results are presented in Table 5. By progressively removing the modules, we observed significant effects on the model’s performance. First, with only the LRPAN module, the model achieved a balanced Recall (0.747) and Precision (0.742), but the mAP@0.5 (0.785) and mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.457) were relatively lower. This suggests that while the LRPAN module effectively improves the recall rate for defect detection, it has not fully optimized detection accuracy and localization capabilities. When the MSRB module was added, there was an improvement in precision, with mAP@0.5 rising to 0.781, and a slight increase in mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.455). However, it is noteworthy that Recall slightly decreased, indicating that the MSRB module plays a crucial role in improving the model’s precision but may result in missing some small defects. Overall, the MSRB module enhanced the model’s ability to perceive defects at various scales.

Most notably, the addition of the SPAA module significantly improved the model’s performance across all evaluation metrics, especially with a substantial increase in mAP@0.5 (0.806) and mAP@0.5:0.95 (0.467). This result indicates that the SPAA module plays a critical role in integrating global and local features and enhancing the model’s adaptability to complex backgrounds. By using progressive spatial attention aggregation and adaptive threshold modulation, the SPAA module effectively suppresses interference signals while amplifying genuine defect features, resulting in higher detection accuracy under complex conditions.

In summary, the ablation study validates the unique contributions of each module in the LSA-YOLO architecture, particularly the SPAA module, which significantly enhances the model’s generalization ability when dealing with industrial data containing complex backgrounds and diverse defect types. These results demonstrate that LSA-YOLO is highly adaptable to defect detection tasks in unseen data and exhibits strong robustness, especially in handling complex real-world industrial applications with various defect types and backgrounds.

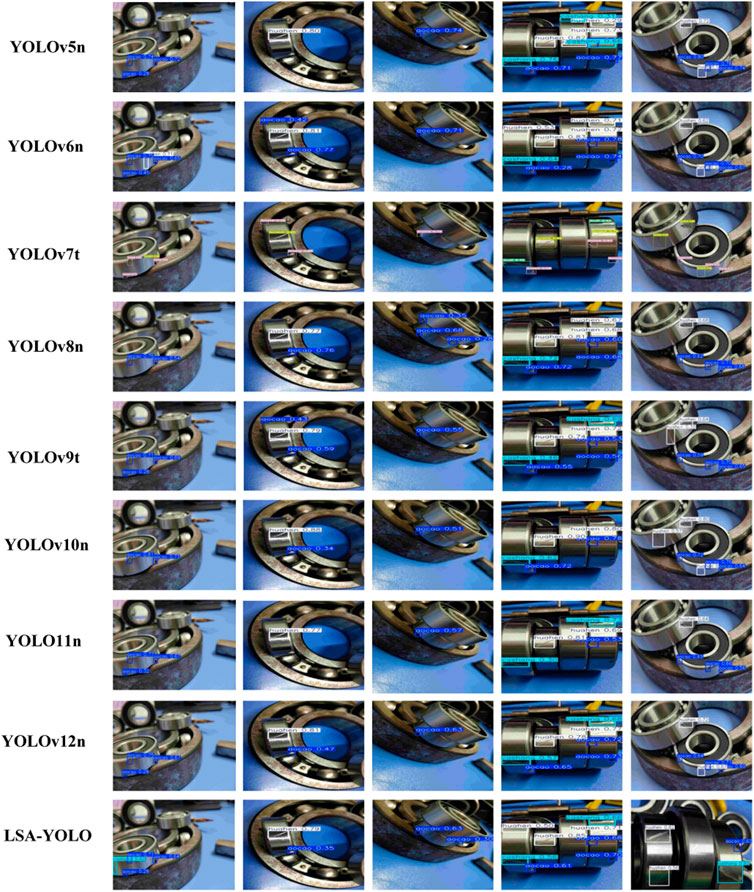

4.7 Comparison of detection results

To visually demonstrate the superior performance of LSA-YOLO in bearing surface defect detection, this study selected five typical bearing samples for a comparative analysis of detection results. Figure 8 shows the detection effects of nine models—YOLOv5n, YOLOv6n, YOLOv7-Tiny, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9-Tiny, YOLOv10n, YOLOv11n, YOLOv12n, and LSA-YOLO—on the same test samples. By comparing the detection accuracy, miss rate, bounding box localization precision, and confidence score distribution of each model, we comprehensively evaluate the technical advantages of LSA-YOLO.

From the perspective of detection completeness, LSA-YOLO demonstrated a significant advantage. In the detection of defects on the inner ring of the bearing in the first column, conventional YOLO models commonly exhibited missed detections. YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n failed to effectively identify some of the minute defect areas. In contrast, LSA-YOLO, leveraging the detail preservation capabilities of its LRPAN network structure, successfully detected all defect targets with confidence scores above 0.89. In the detection of surface defects on the outer ring in the second column, YOLOv7-Tiny and YOLOv9-Tiny had clear missed detections. LSA-YOLO not only achieved complete detection but also had significantly higher detection confidence scores than other models, reflecting the effectiveness of the SPAA module in suppressing background interference and enhancing defect feature response.

In terms of detection accuracy and bounding box localization, LSA-YOLO also showed outstanding performance. The results for the irregular crack defect in the third column show that the bounding box localization of traditional YOLO models had noticeable deviations; models like YOLOv6n and YOLOv11n produced detection boxes that did not accurately cover the entire contour of the defect area. In contrast, LSA-YOLO, through the multi-scale cascaded processing architecture of the MSRB module, achieved precise localization of complex geometric defects. The overlap between the bounding box and the actual defect area was significantly improved, with confidence scores maintained at a high level above 0.85.

In the composite defect detection scenario in the fourth column, LSA-YOLO was able to accurately identify multiple different types of defect targets simultaneously, whereas some traditional models like YOLOv12n only detected a subset of the defects, indicating that LSA-YOLO is more robust in complex detection scenarios.

Particularly noteworthy is LSA-YOLO’s advantage in detecting small-object defects, as shown in the fifth column. The minute defect in this sample occupies less than 1% of the image area, making it a classic small-object detection challenge. Most traditional YOLO models suffered from severe missed detections; YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, and YOLOv10n completely failed to detect the defect. While YOLOv6n and YOLOv7-Tiny produced detection results, their confidence scores were low (between 0.3 and 0.5). LSA-YOLO, through the synergistic action of its three core modules, not only successfully detected the minute defect but did so with a high confidence score of 0.82. This fully validates the technical advantages of the LRPAN network in preserving details, the MSRB module in multi-scale feature processing, and the SPAA module in attention aggregation.

From the perspective of confidence score distribution, LSA-YOLO demonstrated higher detection reliability. Statistical analysis showed that the average detection confidence of LSA-YOLO was 0.86, significantly higher than the 0.65–0.75 range of other models. This indicates that LSA-YOLO can not only accurately identify defect targets but also has a higher degree of certainty in its results, which is of great importance for practical applications in industrial quality inspection. Overall, the visual detection results confirm that LSA-YOLO exhibits comprehensive technical advantages in bearing surface defect detection, offering a more reliable and precise solution for the field of industrial defect detection.

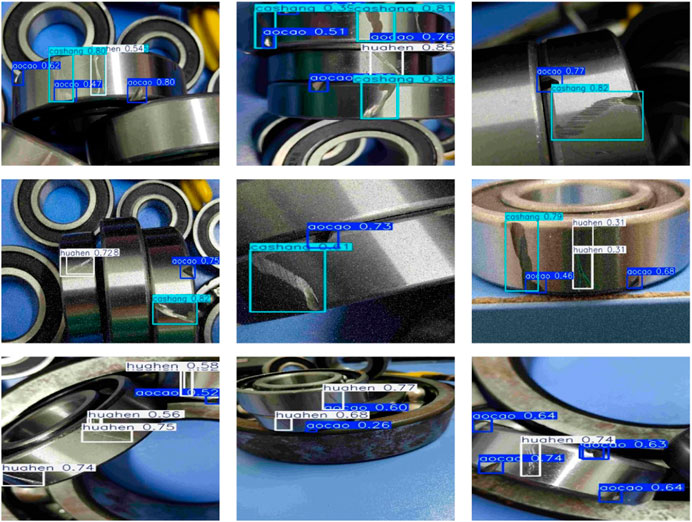

4.8 Analysis of detection results

To further validate the detection performance of LSA-YOLO in real-world industrial environments, this section provides an in-depth analysis of nine representative bearing defect detection cases. Figure 9 illustrates LSA-YOLO’s performance on various defect types, including abrasions (ceshang), grooves (gocao), and scratches (huahen). By connecting these results to the three core innovations of this paper—LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA—we analyze the technical advantages and practical value of LSA-YOLO in complex industrial scenarios.

Analyzing from the perspective of the LRPAN network’s detail preservation capability, the detection results in Figure 9 fully validate its excellent performance against complex texture backgrounds. In the top-left image, the bearing surface features intricate metallic textures and reflective interference, where traditional methods often struggle to accurately extract minute defect features. LSA-YOLO, through LRPAN’s low-order response aggregation path and CSFFC module, successfully identified multiple abrasion defects with confidence scores of 0.34, 0.52, and 0.80, demonstrating the model’s ability to effectively retain rich detail from shallow network layers. The middle image in the second row presents an even more challenging scenario with strong metallic reflections. LSA-YOLO still accurately located a groove defect (confidence 0.73), fully showcasing LRPAN’s technical advantage in detail feature extraction.

The multi-scale feature processing capability of the MSRB module is well-demonstrated in the results. The top-middle image shows a typical multi-object detection scene with defects of varying sizes and shapes. LSA-YOLO, through MSRB’s hierarchical cascaded architecture, successfully identified all defect types, with confidence scores of 0.31 for abrasion, 0.51 for groove, and 0.35 for scratch. Particularly noteworthy is the detection of complex defect shapes in the bottom-left image. The scratch defect exhibits an irregular linear distribution. The MSRB module, through the synergy of its multiple MSEB sub-modules, achieved adaptive modeling of this complex geometry, yielding good confidence levels between 0.52 and 0.75 and effectively overcoming the limitations of traditional rectangular bounding boxes in describing irregular defect contours.

The anti-interference capability of the SPAA module is prominent in several detection cases. The top-right image shows a typical scene with metallic surface reflections, where strong lighting variations can easily create false-positive interference. LSA-YOLO, using SPAA’s progressive spatial attention aggregation mechanism, accurately distinguished between true defects and environmental noise, achieving confidence scores of 0.82 for abrasion and 0.77 for groove, well above any potential interference threshold. In the middle-right image, various types of surface stains and reflective interference are present. The adaptive threshold modulation strategy of the SPAA module effectively suppressed these interferences, ensuring accurate identification of true defects. Scratches were detected with confidence scores of 0.31–0.40, and grooves with a reliable 0.63–0.79.

From an overall performance perspective, the results in Figure 9 demonstrate excellent synergy among the three innovative modules. In the complex detection scenario of the bottom-middle image—with multiple defect types, irregular shapes, and strong background interference—LSA-YOLO accurately detected all defect targets through LRPAN’s detail extraction, MSRB’s multi-scale adaptation, and SPAA’s attention aggregation. Confidence scores for scratches ranged from 0.26 to 0.77, and for grooves was 0.60, fully validating the effectiveness of the modules working in concert. The bottom-right image further highlights LSA-YOLO’s superior performance in dense defect detection, where multiple scratches and grooves were accurately identified with stable confidence levels between 0.63 and 0.74.

An analysis of all detection results in Figure 9 reveals that LSA-YOLO maintains a good confidence distribution across different defect types, with an average detection confidence above 0.58. High-confidence detections (¿0.7) accounted for about 35%, and medium-confidence detections (0.4–0.7) for about 45%. This distribution indicates that LSA-YOLO has stable detection performance and strong generalization ability. In summary, the analysis of detection results confirms that LSA-YOLO, through the synergy of its three core innovative modules, effectively addresses the key technical challenges in bearing surface defect detection, providing a reliable technical solution for industrial quality inspection.

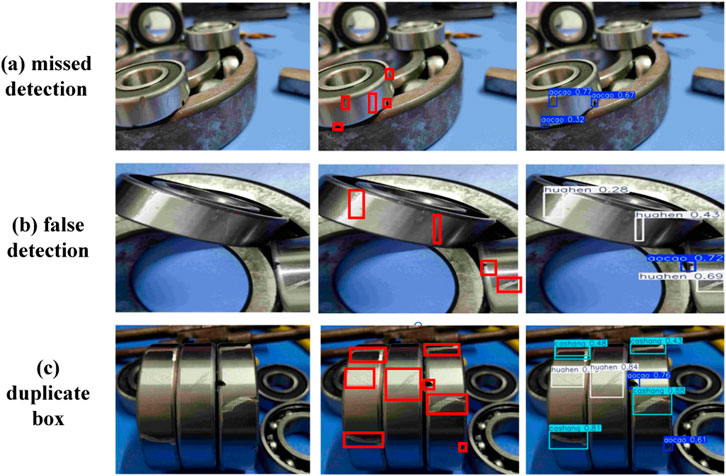

Although the proposed LSA-YOLO model has shown good performance in defect detection, there are still some failure cases observed in certain test scenarios as shown in Figure 10, primarily including missed detections, false detections, and duplicate boxes. Missed detection occurs when the model fails to detect certain actual defects, especially when the defects are small or the background is complex. This indicates that the model’s sensitivity to small defects and its ability to handle complex backgrounds need improvement. False detection happens when the model incorrectly identifies non-defective regions as defects, particularly in areas with complex textures or irregular shapes. This affects the accuracy and precision of detection, suggesting that the model faces challenges in distinguishing between background and defects during feature extraction. Duplicate boxes occur when the model generates multiple overlapping bounding boxes for the same defect, leading to redundant detections. This is usually due to the model being overly sensitive to certain features or insufficient post-processing. While this issue is relatively minor, it still impacts detection efficiency and precision.

These failure cases provide valuable insights for further improving the model, particularly in enhancing its sensitivity to small defects, reducing background noise interference, and optimizing post-processing algorithms. Addressing these issues will help improve the model’s robustness and accuracy in complex industrial scenarios, strengthening its adaptability and performance in real-world applications.

5 Conclusion

This study addresses the key technical challenges in bearing surface defect detection—namely, interference from complex texture backgrounds, difficulty in extracting minute defect features, and inaccurate localization of irregularly shaped defects—by proposing the LSA-YOLO network architecture. This architecture integrates three core modules: LRPAN, MSRB, and SPAA, which respectively achieve detail information preservation, optimized modeling of irregular defects, and effective differentiation between true defects and environmental interference. Experimental results show that LSA-YOLO achieves outstanding performance on a bearing defect dataset, with an F1-score of 88.1%, Precision of 91.4%, Recall of 85.0%, mAP@0.5 of 92.6%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 53.7%, representing a significant improvement over existing state-of-the-art methods. At the same time, the model maintains excellent computational efficiency, with a parameter count of 3.956 million and an inference time of just 0.8 m, meeting the demands of real-time industrial inspection. This research provides an effective solution for the advancement of bearing defect detection technology and holds significant application value in fields such as industrial equipment safety, predictive maintenance, and quality control. It also offers a valuable reference for surface defect detection of other industrial components. Future work will further explore the model’s adaptability to a wider range of industrial defect types, optimize its lightweight design for deployment on edge computing devices, and expand its application to multi-modal industrial detection data fusion.

Data availability statement

Data supporting this study can be obtained from the corresponding author as needed.

Author contributions

HJ: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition, Methodology. ML: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – review and editing. CH: Writing – original draft, Validation. JP: Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project no. 62173171), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (Project no. 2022-MS-397), and the Fuxin Gongda Chengpu Electric Co., Ltd. (Project no. 2025-H0015).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Fuxin Gongda Chengpu Electric Co., Ltd. (Project no. 2025-H0015). The funder had the following involvement in the study: data collection and analysis.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Xu J, Zuo Z, Wu D, Li B, Li X, Kong D, et al. Bearing defect detection with unsupervised neural networks. Shock and Vibration (2021) 2021:9544809. doi:10.1155/2021/9544809

2. Lei L, Sun S, Zhang Y, Liu H, Xie H. Segmented embedded rapid defect detection method for bearing surface defects. Machines (2021) 9(2):40. doi:10.3390/machines9020040

3. Liu B, Yang Y, Wang S, Bai Y, Zhang J. An automatic system for bearing surface tiny defect detection based on multi-angle illuminations. Optik (2020) 208:164517. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2020.164517

4. Stachowiak GP, Stachowiak GW, Podsiadlo P. Automated classification of wear particles based on their surface texture and shape features. Tribology Int (2008) 41(1):34–43. doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2007.04.004

5. Anami BS, Nandyal SS, Govardhan A. A combined color, texture and edge features based approach for identification and classification of Indian medicinal plants. Int J Computer Appl (2010) 6(12):45–51. doi:10.5120/1122-1471

6. Liyun X, Boyu LI, Hong MI, Xingzhong L. Improved faster R-CNN algorithm for defect detection in powertrain assembly line. Proced CIRP (2020) 93:479–84. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2020.04.031

7. Yixuan L, Dongbo W, Jiawei L, Hui W. Aeroengine blade surface defect detection system based on improved faster RCNN. Int Journal Intelligent Systems (2023) 2023:1992415. doi:10.1155/2023/1992415

9. Wang CY, Bochkovskiy A, Liao HYM. YOLOv7: trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (2023). p. 7464–75.

10. Wang CY, Yeh IH, Mark Liao HY. Yolov9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2402.13616 (2024) 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-72751-1_1

11. Wang A, Chen H, Liu L, Chen K, Lin Z, Han J. Yolov10: real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv Neural Inf Process Sys (2024) 37:107984–108011. doi:10.52202/079017-3429

12. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process Sys (2017) 30.

13. Zhang H, Li F, Liu S, Zhang L, Su H, Zhu J, et al. Dino: detr with improved denoising anchor boxes for end-to-end object detection. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2203.03605 (2022).

14. Dai X, Chen Y, Yang J, Zhang P, Yuan L, Zhang L. Dynamic detr: end-to-end object detection with dynamic attention. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (2021). p. 2988–2997.

15. Zhang Y, Li K, Li K, Wang L, Zhong B, Fu Y. Image super-resolution using very deep residual channel attention networks[C]. In: Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) (2018). p. 286–301.

16. Fang H, Lin S, Hu J, Chen J, He Z. CPF-DETR: an end-to-end DETR model for detecting complex patterned fabric defects. Fibers Polym (2025) 26(1):369–82. doi:10.1007/s12221-024-00809-9

17. Ji L, Huang C, Li H, Han W, Yi L. MS-DETR: a real-time multi-scale detection transformer for PCB defect detection. Signal Image Video Process. (2025) 19(3):203. doi:10.1007/s11760-024-03757-2

18. Wu D, Wu R, Wang H, Cheng Z, To S. Real-time detection of blade surface defects based on the improved RT-DETR. J Intell Manufacturing (2025) 1–13. doi:10.1007/s10845-024-02550-9

19. Wu F, Gong Y. Lightweight lswin transformer fusion steel surface model defect detection method research, 13213. SPIE (2024). 659–64.

20. Ji M, Zhao G. Devit: deformable convolution based-vision transformer for bearing fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans Instrumentation Meas (2024) 73:1–13. doi:10.1109/tim.2024.3440383

21. Liu M, Wang H, Du L, Ji F, Zhang M. Bearing-detr: a lightweight deep learning model for bearing defect detection based on rt-detr. Sensors (2024) 24(13):4262. doi:10.3390/s24134262

22. Zhou AY, Farimani AB. FaultFormer: pretraining transformers for adaptable bearing fault classification. IEEE Access (2024) 12:70719–28.

23. Mirzaeibonehkhater M, Labbaf-Khaniki MA, Manthouri M. Transformer-based bearing fault detection using temporal decomposition attention mechanism. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2402.11245 (2024).

24. Bao Z, Du J, Zhang W, Wang J, Qiu T, Cao Y. A transformer model-based approach to bearing fault diagnosis. In: International conference of pioneering computer scientists, engineers and educators. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore (2021). p. 65–79.

25. Jing J, Zhuo D, Zhang H, Liang Y, Zheng M. Fabric defect detection using the improved YOLOv3 model. J Engineered Fibers Fabrics (2020) 15:1558925020908268. doi:10.1177/1558925020908268

26. Li M, Wang H, Wan Z. Surface defect detection of steel strips based on improved YOLOv4. Comput Electr Eng (2022) 102:108208. doi:10.1016/j.compeleceng.2022.108208

27. Duman B. A real-time green and lightweight model for detection of liquefied petroleum gas cylinder surface defects based on YOLOv5. Appl Sci (2025) 15(1):458. doi:10.3390/app15010458

28. Li J, Chen Y, Li W, Gu J. Balanced-YOLOv3: addressing the imbalance problem of object detection in PCB assembly scene. Electronics (2022) 11(8):1183. doi:10.3390/electronics11081183

29. Zhang H, Du H. Improved THT solder joint in PCB defect detection model based on YOLOv8[C]//2023 3rd international conference on computer science and blockchain (CCSB). IEEE (2023). p. 83–7.

30. Li F, Xiao K, Hu Z, Zhang G. Fabric defect detection algorithm based on improved YOLOv5. The Vis Computer (2024) 40(4):2309–24. doi:10.1007/s00371-023-02918-7

31. Xing Z, Zhang Z, Yao X, Qin Y, Jia L. Rail wheel tread defect detection using improved YOLOv3. Measurement (2022) 203:111959. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2022.111959

32. Ding P, Zhan H, Yu J, Wang R. A bearing surface defect detection method based on multi-attention mechanism Yolov8. Meas Sci Technology (2024) 35(8):086003. doi:10.1088/1361-6501/ad4386

33. Yang D, Ma C, Yu G, Chen Y. Automatic defect detection of pipelines based on improved OFG-YOLO algorithm. Measurement (2025) 242:115847. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.115847

34. Ruan S, Zhan C, Liu B, Wan Q, Song K. A high precision YOLO model for surface defect detection based on PyConv and CISBA. Scientific Rep (2025) 15(1):15841. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91930-z

35. Liu Y, Liu Y, Guo X, Ling X, Geng Q. Metal surface defect detection using SLF-YOLO enhanced YOLOv8 model. Scientific Rep (2025) 15(1):11105. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-94936-9

36. Zhang S, He Y, Gu Y, He Y, Wang H, Wang H, et al. UAV based defect detection and fault diagnosis for static and rotating wind turbine blade: a review. Nondestructive Test Eval (2025) 40(4):1691–1729. doi:10.1080/10589759.2024.2395363

37. Xu X, Deng J, Lin H, Li Z, Wen H. Lightweight anomalous detection of hydro turbine operation sound using fusion network enhanced by load information. IEEE Trans Instrumentation Meas (2025) 74:1–13. doi:10.1109/tim.2025.3533632

38. Wang J, Song Y, He T. A novel adaptive monitoring framework for detecting the abnormal states of aero-engines with maneuvering flight data. Reliability Eng and Syst Saf (2025) 258:110910. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2025.110910

39. Chen J, Sun L, Song Y, Geng Y, Xu H, Xu W. 3D surface highlight removal method based on detection mask. Arabian J Sci Eng (2025) 1–13. doi:10.1007/s13369-025-10573-4

40. Qiao Y, Lü J, Wang T, Liu K, Zhang B, Snoussi H. A multihead attention self-supervised representation model for industrial sensors anomaly detection. IEEE Trans Ind Inform (2023) 20(2):2190–2199.

41. Hu C, Zhao C, Shao H, Deng J, Wang Y. TMFF: Trustworthy multi-focus fusion framework for multi-label sewer defect classification in sewer inspection videos. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst Video Technology (2024) 34:12274–87. doi:10.1109/tcsvt.2024.3433415

42. Wang H, Li YF, Men T, Li L. Physically interpretable wavelet-guided networks with dynamic frequency decomposition for machine intelligence fault prediction. IEEE Trans Syst Man, Cybern: Syst (2024) 54(8):4863–4875. doi:10.1109/tsmc.2024.3389068

43. Li Z, Xiao L, Shen M, Tang X. A lightweight YOLOv8-based model with squeeze-and-excitation version 2 for crack detection of pipelines. Appl Soft Comput (2025) 177:113260. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113260

44. Shen X, Wang Y, Ma Y, Li L, Niu Y, Yang Z, et al. A multi-expert diffusion model for surface defect detection of valve cores in special control valve equipment systems. Mech Syst Signal Process (2025) 237:113117. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2025.113117

45. Wan A, Zhang F, Khalil ALB, Cheng X, Ji X, Wang J, et al. A novel GA-PSO-SVM model for compound fault diagnosis in gearboxes with limited data. IEEE Sensors J (2025) 25:30431–43. doi:10.1109/jsen.2025.3576761

46. Wan A, Zhu Z, Khalil ALB, Cheng X, Ji X, Wang J, et al. Fault diagnosis of helicopter accessory gearbox under multiple operating conditions based on feature mode decomposition and multi-scale convolutional neural networks. Appl Soft Comput (2025) 180:113403. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2025.113403

Keywords: bearing defect detection, industrial vision, multi-scale feature processing, attention mechanism, robust detection

Citation: Jin H, Li M, Huang C and Peng J (2025) LSA-YOLO: a bearing surface defect detection method based on low-order response aggregation and progressive attention. Front. Phys. 13:1722962. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2025.1722962

Received: 11 October 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Sauro Succi, Italian Institute of Technology (IIT), ItalyReviewed by:

Njitacke Tabekoueng Zeric, University of Buea, CameroonOguzhan Das, Milli Savunma Universitesi Hava Astsubay Meslek Yüksekokulu, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Jin, Li, Huang and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haibo Jin, amluaGFpYm9AbG50dS5lZHUuY24=

Haibo Jin

Haibo Jin Mengjiao Li2

Mengjiao Li2