- Science News

- Life sciences

- Microbial colonisers of Arctic soils are sensitive to future climate change

Microbial colonisers of Arctic soils are sensitive to future climate change

A view across Kongsfjorden to the Midtre Lovenbreen glacier where the research was conducted. Image credit: James A. Bradley

A team of researchers from the University of Bristol have recently shown that ecosystems created by melting glaciers in the Arctic are sensitive to climate change and human activity.

— By Nick Fraser

According to data from NASA, 2016 was the hottest year on record for our planet, with global average temperatures reaching levels nearly 1 °C warmer than during the mid-20th century. In the Arctic regions, positive feedback loops cause temperatures to rise even faster, a process known as Arctic amplification.

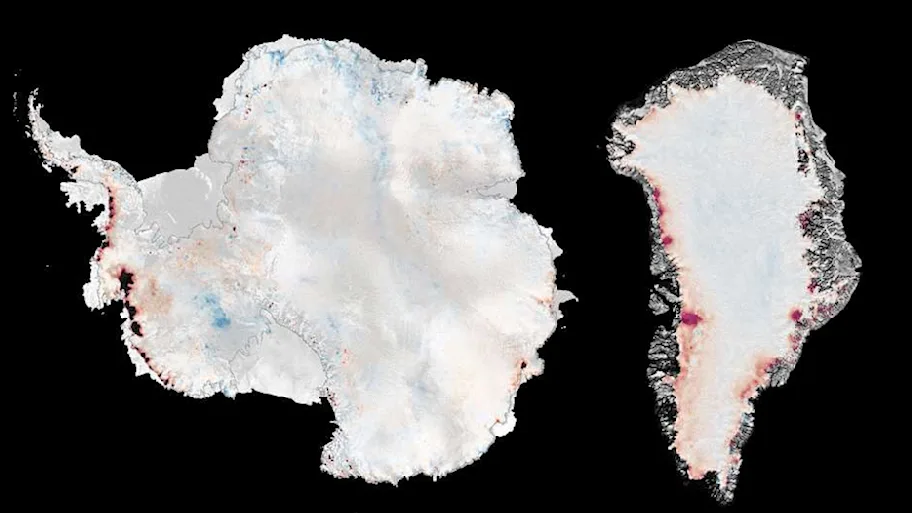

Warming of the Arctic has manifested itself through the melting and retreat of glaciers, exposing vast landscapes previously covered by ice. Such changes are thought to have an important effect on the delicate microbial ecosystems that colonise these newly exposed soils, yet relatively little is known about their exact responses to future climate change scenarios.

A new study by a team of researchers from the University of Bristol, recently published in Frontiers in Earth Science, has attempted to address this problem using new computational modelling software. Lead author James Bradley, from the School of Geographical Sciences and Cabot Institute at the University of Bristol (and now based at the University of Southern California), explains: “It is challenging to predict the effects of future climate change with field and laboratory experiments alone. It takes decades to feasibly monitor long term ecological change. Recently designed modelling software allows us to manipulate and simulate experimental conditions over century timescales to enable long-term predictions of the effects of climate change on ecosystems.”

The researchers’ efforts focused on the areas surrounding the Midtre Lovénbreen glacier in Svalbard, a site that has changed dramatically in the past years. Glaciers have melted away, retreating by tens of metres, and exposed soils to the atmosphere for the first time in thousands of years. The rate of melting is expected to increase in the coming years as Arctic temperatures increase further.

Their findings showed that future climate change in the Arctic over the next two centuries may enhance microbial growth and respiration rates, increasing CO2 emissions from soils. Enhanced microbial activity also may increase nutrient availability and encourage plants to grow in these extreme environments.

Bradley stresses the importance of the results: “This research provides evidence that Arctic ecosystems are sensitive to predicted climate change resulting from human activity. This evidence should be used in environmental assessments of the effects of climate change, and by government and inter-governmental organisations seeking to minimise the effects of human activity on the delicate and fragile ecosystems of Polar regions.”

As the Arctic continues to warm, and glaciers retreat further, Bradley says that more work is needed to complete our understanding ecosystem dynamics in this region: “Future work should focus on generating increasingly robust field data, and increasing the understanding of the processes that lead to plant colonisation in recently exposed Arctic soils.”