- Science news

- Frontiers news

- Rhiannon Nichol – Beneath retreating glaciers: Science and stewardship in South Georgia

Rhiannon Nichol – Beneath retreating glaciers: Science and stewardship in South Georgia

Author: Chiara Francesca Paoli

In honor of World Ocean Day 2025, I spoke with Rhiannon Nichol, a marine biologist currently on a 24-month research deployment at King Edward Point Research Station in South Georgia. Her work is part of a long-term project for the British Antarctic Survey (BAS), helping to guide the management of the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Marine Protected Area by the South Georgia Government.

Surrounded by mountains and glaciers, the subantarctic island of South Georgia is a critical haven for wildlife: it hosts five million seals across four species, 65 million breeding birds from 30 species, and supports thriving populations of migratory whales, fish, and Antarctic krill. These krill form a vital link in the Southern Ocean food web.

I spoke with Rhi about her work at the station, the challenges of conducting research in such a remote region, and the impacts of climate change on local ecosystems.

It has now been six months since Rhi left the UK for South Georgia, and she still has 18 months to go before her contract ends—a total of two years spent far from home. “I’ll only be able to go back for one extended holiday at some point,” she shares, “but I've really enjoyed my time so far. South Georgia is absolutely phenomenal.”

Living and working in a Sub-Antarctic region

To begin, I asked Rhi what it is like to live and work in such a remote region, and how many people reside on the island.

“Currently, there are nine people stationed here for the winter—eight from the British Antarctic Survey and one government officer, though we expect a second officer to join us soon, bringing the total to ten. Currently, our team consists of myself and another biologist, Katie, who has already spent a year here and is now guiding me through my training. The rest of the staff at the British Antarctic Survey are responsible for keeping the station fully operational. We have a doctor, two boating officers, two technicians, and a station leader. Together, they ensure everything runs smoothly, especially through the challenges of winter—for example, maintaining the hydroelectric plant and switching to generators when needed. The boating officers are essential to our research, helping us reach sites that aren’t accessible by foot, while the station leader oversees the whole operation and keeps everything on track. This represents our typical winter staffing. There’s also another research station located on Bird Island, just off the coast of South Georgia, which is staffed by four people throughout the winter until October.

“During the summer, the station becomes much busier with additional staff from the South Georgia Government, the South Georgia Heritage Trust (SGHT), and visiting scientists, alongside BAS. The SGHT operates nearby and there’s a small museum about a kilometer from our base. Tourism also picks up significantly, with the museum and two post offices opening to accommodate both visitors and staff—allowing us to send postcards back home. Additionally, a dedicated government maintenance team comes in to work on both heritage sites and station buildings; for example, they fully rebuilt one of our work huts this year. We also host a contracted team focused on removing invasive species—they’re highly effective in their efforts to control invasive weeds across the island. With all these groups combined, our numbers can swell to around 35 people during the peak of summer, and cruise ship visits add even more activity to the area.”

Studying and protecting South Georgia’s ecosystem

We then turned to her research activities and how they contribute to conservation management in the region.

“Much of our research centers on long-term monitoring, which is vital for the conservation and management of South Georgia’s wildlife. We focus on biological studies, particularly monitoring animal populations. For example, during breeding season, we regularly survey elephant seals and Antarctic fur seals, conducting individual counts and photographic surveys to track numbers of males, females, and pups. We even hope to incorporate drone surveys for the elephant seal monitoring in the future. These surveys allow us to pinpoint important milestones, such as peak pupping dates, and help us observe trends within local populations. Throughout the summer, Katie and I hike out to our study colonies every three days, covering about 14 kilometers round trip to capture photos from designated points, which are later processed and analyzed back at the station.

“Our marine research is equally detailed. Every two months, we conduct ship-based surveys—running echo sounder transects to track krill swarms and simultaneously recording observations of marine mammals like whales. When we identify krill swarms, we often perform targeted trawl sampling, bringing back specimens to determine demographic details like length frequency and cohort structure; these samples are sent to be further analyzed in Cambridge. Monitoring krill is crucial here, as so many species—fur seals, birds, penguins, and whales—depend on it. In parallel, we frequently collect other species of plankton samples, and use instruments to record the ocean’s conductivity, temperature, and depth, providing additional insight for broader ecosystem studies.

“Summer brings increased scientific activity, with visiting teams collaborating on various projects. This year, we’ve supported the ‘Hungry Humpbacks’ whale research, as well as studies on highly pathogenic avian influenza, which is present among the island’s bird populations. We assist with sampling and data collection for both in-house and visiting scientists, adapting our schedules to support priority research as needed.

“Fieldwork can be especially demanding during the summer months. Some of our tasks—like certain deployments or sampling—must take place outside of daylight hours, meaning late nights and long, often irregular shifts. While the ship’s data collection systems run continuously, our team balances the workload to ensure everyone gets sufficient rest. No two days are ever quite the same, but the common thread is our commitment to rigorous, ongoing monitoring that enables effective conservation in this dynamic ecosystem.”

The challenges and risks of working in an isolated region

As our conversation shifted to the realities of working on South Georgia, Rhi described the region’s unique challenges.

“Weather in South Georgia changes rapidly, with strong winds and rough seas that can completely disrupt research plans. Travel between different areas of the island often depends on boat support, and we frequently have to postpone or adjust our work because it becomes impossible, or even dangerous, to get where we need to be. Flexibility is vital: you learn to seize any break in the weather to head out to field sites or launch sea trips, because calm days are few and far between. Even ocean research requires careful coordination, as we need suitable conditions and have to work around other priorities for ship time.

“Now that winter is arriving, snow covers the ground and conditions will become increasingly inhospitable. This change in the environment means that we have to be much more cautious, especially with snowpack and avalanche risk. We carry specialized equipment to assess snow safety before going out, but moving around outside the station still requires careful planning.

“The remoteness of South Georgia adds another layer of complexity. We’re around four days’ sail from the nearest hospital or external help. While we do have a doctor and a medical facility on station, our medical resources are necessarily limited, and evacuation for anything serious would take time and could only happen by ship—helicopters are out of range. This means we place a strong emphasis on safety and prevention; it’s not about dealing with emergencies as they happen, but rather doing everything possible to ensure those emergencies never arise in the first place.”

Visible signs of climate change

I then asked Rhi about the impact of climate change on South Georgia and its ecosystems.

“Although I’ve only been stationed on South Georgia for half a year—so I don’t have my own long-term baseline to draw on—the signs of climate change here are undeniable. The most striking evidence is the rapid retreat of glaciers, exposing new ground that invasive species can quickly colonize. South Georgia has been significantly impacted by the introduction of various invasive species, both plants and animals, primarily brought by human activity in the past. While there are ongoing eradication efforts, the retreating ice is creating connections between areas that used to be isolated, helping invasive species spread further and posing a threat to local species.

“The effects of climate change are even visible on our navigational charts: there are now areas of waters that are uncharted because glaciers once stood there, and areas that used to be solid land are now open sea, accessible by boat for the first time. Places we previously couldn’t reach are opening up as the ice retreats.”

Gender representation in marine science

We ended our conversation by exploring her views on gender representation within marine science.

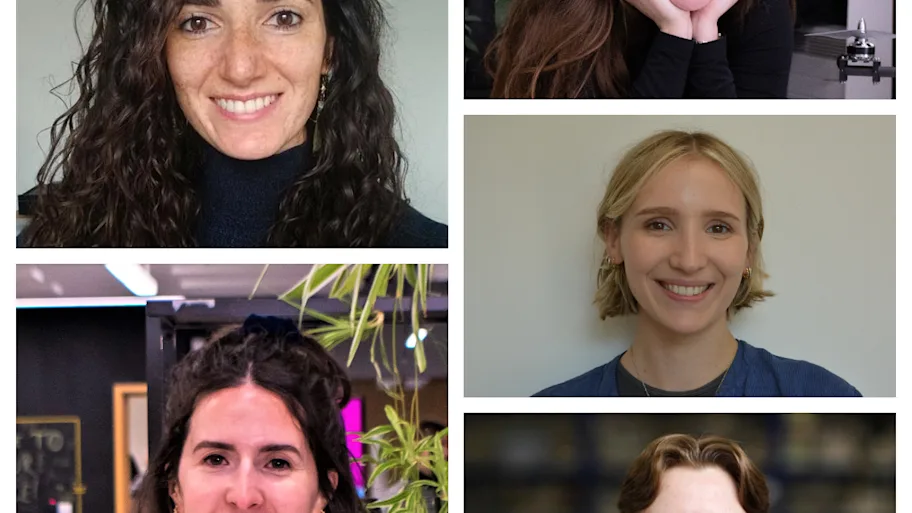

“In my experience, both here and in previous roles, I’ve worked in teams that were quite gender balanced. For instance, here at the station we have an equal number of men and women, and both marine biologists on site —including myself — are women. I also work under excellent female managers, which has been inspiring.

“Of course, some parts of marine biology—and other scientific fields—remain male dominated, while others may have more women. It really depends on the area. However, I’ve noticed genuine efforts to make the field more accessible and supportive for women, especially given the challenges involved in fieldwork.

“Overall, it’s encouraging to see a genuine commitment to breaking down gender barriers—I think we’re seeing real progress in creating a more inclusive and balanced environment. For example, at Pre-Deployment Training ahead of going south, time was dedicated to talking about menstrual hygiene in the field and on the station, which everyone attended, not just people who menstruate, helping to break the taboo around an important aspect of health in the field. Likewise, at a previous marine roles, I have seen initiatives such as ‘menopause cafes’ to discuss things surrounding menopause and to give a judgement-free space not only for people experiencing menopause to receive support, but also for people who aren’t directly affected to learn how colleagues may be impacted.”

Frontiers is a signatory of the United Nations Publishers Compact. This interview has been published in support of United Nations Sustainability Development Goal 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls and United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14: Conserve and sustainability use oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.