- Science news

- Life sciences

- World’s largest rays may be diving to extreme depths to build mental maps of vast oceans

World’s largest rays may be diving to extreme depths to build mental maps of vast oceans

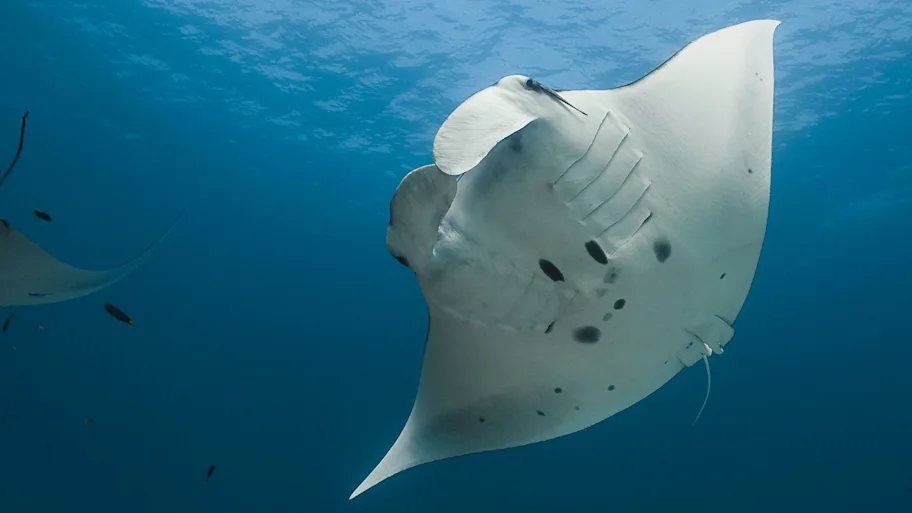

When we leave familiar areas, we might need a moment to reorientate ourselves. Similarly, oceanic manta rays, the largest species of ray which travels thousands of kilometers between habitats, may need to gather information about their new surroundings after moving away from the coasts. They are capable of diving to extreme depths, up to more than 1,200 meters – and a new study showed that this behavior might help them navigate across the open ocean. These extreme dives could help the animals sample environmental cues and allow them to travel between ecosystems.

Many marine species are no strangers to the depths of the oceans. Some animals, like certain sharks, tuna, or turtles, routinely perform extreme dives, whereas for other species such behavior has been observed less frequently.

Now, an international team of researchers working in Peru, Indonesia, and New Zealand tagged oceanic manta rays – the largest species of ray – to learn more about the deep-diving behavior of these animals. They published their results in Frontiers in Marine Science.

“We show that, far offshore, oceanic manta rays are capable of diving to depths greater than 1,200 meters, far deeper than previously thought,” said first author Dr Calvin Beale, who completed his PhD at Murdoch University. “These dives, which are linked with increased horizontal travel afterwards, may play an important role in helping mantas gather information about their environment and navigate across the open ocean.”

Under the sea

The team tagged 24 oceanic manta rays at three sites, Raja Ampat in eastern Indonesia, near Tumbes off the coast of northern Peru, and near Whangoroa in northern New Zealand. They observed mantas’ diving behavior between 2012 and 2022. Eight of the tags, programmed to release after several months, were recovered after floating back to the surface. “It is quite a challenging task, trying to spot a small gray floating object with a short antenna bobbing around in the waves with other flotsam and jetsam,” Beale said. High-frequency data was downloaded every 15 seconds from the recovered tags. The 16 non-recovered tags transmitted summary data via satellite.

In total, 2,705 tag-days of data were recorded. On 79 days, mantas dived to extreme depths, reaching a maximum of 1,250 meters. 71 of these extreme dives, defined as deeper than 500 meters, happened in the waters off New Zealand.

The data showed that New Zealand mantas usually initiated an extreme dive within a day after moving off the continental shelf and into deeper waters. The dives were characterized by a stepped decline and little to no time spent at maximum depths. This suggests that the animals didn’t dive this deep to forage or escape hunters, some of which can reach equal diving depths.

Instead, mantas may use cues such as changes in the Earth's magnetic field strength and gradient, or sample changes in oxygen, temperature, and even light levels. “By diving down and ‘sampling’ these signals, they could build a mental map that helps them navigate across vast, featureless stretches of open ocean,” Beale explained. Sampling deep below the surface may help because at great depths the ocean environment is more stable and predictable than at the surface.

Stepped resurfacing and prolonged periods of recovery back at the surface concluded these dives. They were often followed by extended movement over the next few days, covering distances of more than 200km. This further consolidates the theory that extreme dives may serve other functions than foraging.

Read and download original article

Deep diving

In Peru and Indonesia, few extreme dives were recorded, which might be due to manta rays’ habit of remaining in shallower coastal habitats. In Raja Ampat, for example, the seas are mostly shallow and the few deep-water corridors are relatively short, giving mantas less need to seek navigation information. In New Zealand, however, oceanic manta rays were moving through deep offshore habitats where the seafloor drops away quickly, making extreme dives possible and necessary.

“Understanding the nature and function of deep dives helps explain how animals cross vast, seemingly featureless oceans and connect ecosystems thousands of kilometers apart,” Beale pointed out.

The study used relatively few tags and analyzed behavioral snapshots rather than continuous tracks, the researchers pointed out. They said that future studies should use larger datasets and confirm the function of deep dives performed by oceanic manta rays.

“Our study highlights how dependent migratory species are on both coastal and offshore habitats, stressing the need for international cooperation in their conservation,” Beale concluded. “It also reminds us that the deep ocean – which regulates Earth’s climate and underpins global fisheries – remains poorly understood but vitally important.”

REPUBLISHING GUIDELINES: Open access and sharing research is part of Frontiers’ mission. Unless otherwise noted, you can republish articles posted in the Frontiers news site — as long as you include a link back to the original research. Selling the articles is not allowed.