- 1Department of Mathematics, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan

- 2Department of Mathematics and Statistics, The University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

- 3Department of Mathematics, Cankaya University, Ankara, Turkey

- 4Institute of Space Sciences, Bucharest, Romania

- 5Faculty of Engineering, University of Central Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

This study is concerned with finding a numerical solution to the delay epidemic model with diffusion. This is not a simple task as variables involved in the model exhibit some important physical features. We have therefore designed an efficient numerical scheme that preserves the properties acquired by the given system. We also further develop Euler's technique for a delayed epidemic reaction–diffusion model. The proposed numerical technique is also compared with the forward Euler technique, and we observe that the forward Euler technique demonstrates the false behavior at certain step sizes. On the other hand, the proposed technique preserves the true behavior of the continuous system at all step sizes. Furthermore, the effect of the delay factor is discussed graphically by using the proposed technique.

1. Introduction

One of the greatest threats that the world is facing is Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and its development into Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). This is the disease that attacks the immune system of the human body. There are specific type of white blood cells that fights against disease. HIV interrupts the body's ability to fight the organism, causing disease. When the CD4 cells are decreased up to the certain level, the immune system becomes too weak to defend the body against the infection. The role of mathematical models in studying infectious diseases, such as Hepatitis C and HIV/AIDS, is very significant [1]. Many existing models have studied the HIV/AIDS dynamics without considering the delay factor, which do not provide us with accurate results [2]. It is more realistic to apply the delay model when studying HIV/AIDS disease as it is a better fit to the real phenomenon. The delay models are compatible with the real situation. Models used widely to study the infectious dynamics contain non-linear differential equations without delay, but these models can be made more appropriate and comprehensive to study the viral infection in a better and more concise way. Delay mathematical models have been studied extensively by many researchers [3–7]. Recently, the role of delay factor has been investigated for the biological systems as many biological systems observe the time delay property [8].

Various researchers have pointed out the difficulties and discrepancies in the classical models. They improved the existing models by introducing some key facts, such as diffusion, the time delay, and other related factors. For reference we can see that Pan-Ping Lin discussed epidemic models with diffusion and delays and used Neumann boundary conditions. Many researchers pointed out that in some infectious diseases, such as Hepatitis, AIDS, Cholera etc. [9–12], symptoms do not appear immediately. The individual required a certain period of time after getting the infection before exhibiting symptoms, and this is known as the expose period. In some diseases, a time delay is necessary to investigate the dynamics of the infection. In such types of diseases, the change in the state of infection at any time depends on time as well as on other influencing factors before the moments under consideration [13–15]. It is matter of fact that an individual moves in the community due to many reasons, and so the diffusion term in the model with delay factor is better to use for this study of disease dynamics [16–19]. Thieme and Zhao investigated a reaction diffusion model with delay and studied the spatial spread of the epidemic disease. They found the traveling wave solutions and propagation speed [20–22]. Li et al. addressed the Turing pattern formation on the time-delayed epidemic model [14].

The dynamical behavior of epidemic models with the time delay is the most common and interesting topic that has sparked the interest of researchers nowadays. It is a matter of fact that infection does not spread with the same speed in all parts of the world. In some areas it communicates rapidly, and in others it spreads slowly. This situation can be handled by considering the reaction–diffusion term in the model. In this study, a time-delayed epidemic model for HIV/AIDS infection is studied with reaction diffusion.

Mathematical modeling is a useful tool for the study of the dynamical system relating to difference physical phenomenon [23–28] and the mechanism behind how an infectious disease can spread into a population. The future course of an outbreak and measures to control an epidemic can be predicted through modeling. The basic idea of modeling–to study the rapid rise and fall of the infected population–was given by Kermack and McKendrik [29]. A detailed history of SIR epidemic models may be found in the classical books of Bailey, Murray, and Anderson and May. In this study we discuss the epidemic model of HIV(AIDS) with a delay factor and diffusion. Delay is a comprehensive term used in physical models of epidemiology. Various authors have proposed several epidemic models of delay differential equations for the study of the control of the dynamics of infectious diseases with the help of the delay factor [7, 19, 30–38]. Vaccination may be used as a delay factor for some diseases. Education about a certain disease, i.e., precautions and safety measures for a specific disease, may result in slowing the communication of the disease and may thus act as a delay factor.

2. Mathematical Model

Unlike some other viruses, the human body cannot get rid of HIV completely. Once you have HIV, you have it for life. Furthermore, HIV can lead to the disease AIDS if left untreated. No effective cure for HIV currently exists, but, with proper care, treatment, and medical aid, HIV can be controlled. Li and Ma [37] studied the asymptotic properties of the HIV-1 Infection Model with time delay in 2006. The following model was proposed by Abdullahi and Nweze [39] in 2011. There were several variables and parameters:

S = Proportion of susceptible individuals

I = Proportion of infected individuals

R = Proportion of recovered individuals

b = Recruitment rate of the population

μ = Death rate

β = Rate at which susceptible individuals will become Infected

k = Rate at which infected individuals will become recovered

α0 = Death Rate of Infected population

α1 = Death Rate of Recovered population

N = Total population

and N = S + I + R

where τ is the incubation period. This is a time during which an infected individual will become infectious, i.e., they can spread the infection further. The incidence rate βS(t − τ)I(t − τ)e−μτ appearing in the second equation of system (1) represents the rate at time t − τ at which susceptible individuals are leaving the susceptible class and entering the infectious class at time t. Therefore, the fraction e−μτ follows on from the assumption that the death of individuals follows a linear law given by the term −μτ [38]. The compartmental (SIR) model is designed for an HIV/AIDS model that comprises three non-linear equations that involve ordinary derivatives and a delay factor. The assumption is made that all the individuals in the population are intermixing freely with each other, so the individuals of one area cannot be distinguished from the individuals of the other area. If the situation is different from this, then disease may communicate with different rates in different areas; it thus becomes necessary to model the problem depending upon space as well as time. It seems practical to take into account the diffusion factor for the study of underlying disease, justifying the study of the spread of disease in space. The delayed delay reaction equations obtained from the model are

The second order partial derivatives in the model with respect to x (the space variable) describe the diffusion in space. The term βS(t − τ)I(t − τ)e−μτ in the second equation of model addresses the incidence rate at moment (t − τ). This term is developed by using the law of mass action in epidemiology [40]. At this particular term the (t − τ) susceptible exit their compartment and join the infected class. Meanwhile, the factor e−μτ reveals that the death of an individual at time τ obeys the linear law as expressed by −μτ. This fact can be followed from the assumption made in the model as discussed [41]. The time delay (τ > 0) is a specific time (incubation period) of the disease in which a pathogen reflects the symptoms in the individual. After this period of the time, the infected individual become infectious and can spread disease in the susceptible population. Since R is not present in the first two equations of the above system, we can consider

With the initial set of conditions being

and homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions.

2.1. Qualitative Behavior

The epidemic models exhibit two types of steady states: the infected steady state and uninfected steady state. The steady states employed by the delay epidemic model of HIV/AIDS dynamics are given as Uninfected steady (US) state and Infected steady (IS) state where , when d1 = d2 = d3 = 0 is the reproductive number of the HIV/AIDSS epidemic model. When R0 < 1 the disease is going to be at an end and when R0 > 1 then disease will spread further.

3. Numerical Modeling

Numerical modeling involves the study of methods to find approximate solutions to differential equations. In recent times, numerical solutions of delay differential equations are of great import due to the versatility of the modeling processes in different fields [42–48]. Various physical systems involving delay differential equations possesses the physical phenomenon like population sizes, concentration, density and pressure etc. required the positive solution. The numerical technique used to solve these systems must preserve the positive solution of delay differential equations. It is not an easy business to find the numerical solution of these systems as they demonstrate some important physical properties that should be preserved by a numerical method [49–51]. In general, the numerical schemes for special mathematical models, such as population dynamics and concentration profile, are a substance that do not show specific properties attached to the situation, such as positivity, boundedness, etc. These computational methods, if such properties are guaranteed, lead to some more restrictions on the choices of step sizes, which pay a high computational cost. In our case, however, we propose a numerical algorithm that not only handle the structural properties of the dynamical system but also provide a convergent solution for large step sizes, which means a very low computational cost. In this study, we design an efficient numerical technique for the solution for delayed reaction–diffusion epidemic models. This technique preserves all the important structures of the continuous delayed reaction–diffusion epidemic systems, such as positivity, stability of equilibrium points, etc. We also further develop the Euler technique for the proposed continuous system in order to validate the efficacy of our proposed technique.

3.1. Forward Euler Finite Difference Method

The Finite Difference Method is a numerical method that deals in mathematical sciences to solve differential equations by discretization. The Forward Euler technique is a widely used, well-known numerical technique in which derivatives are discretized by finite differences. In this approximation method, forward difference is used for the time derivative and central difference is implemented on the space derivative. By applying this technique on the system (4) and (5), we have

where

3.2. Stability Analysis of Forward Euler Method

As for as stability of the forward Euler technique for where the system under study is concerned, we first implement the Von-Neumann stability within the scheme (6). The Von Neumann stability method is very efficient and widely used method to see the stability of the finite difference schemes. First, we consider the scheme (6),

Put into the above scheme and use linearization, and we have

The difference scheme is stable if amplification factor, |ξ| ≤ 1. We thus get . After some simplifications, we have . Again, by following the same steps as implemented on scheme (6), first consider the Equation (7)

Put into the above scheme and use linearization, and we have

as |ξ| < 1 and ξ−m < 1 we have .

3.3. Proposed Finite Difference Method

The non-standard finite difference scheme is made up of a general set of methods in numerical analysis that provide numerical solutions for differential equations by constructing a discrete model [52]. It was first introduced by R. E. Mickens in 1989. The proposed finite difference scheme [49] is designed with the help of ideas given by Mickens [52].

and

Theorem 1. The numerical scheme (9) and (10) proposed for the delayed SIR epidemic reaction–diffusion model of HIV/AIDS dynamics shows the positive solution unconditionally with the initial conditions, if and as well as and

Proof.

and

We will prove this theorem by using a mathematical induction method. By ensuring n = 0 we achieve

which shows that clearly

which implies that , supposing that the result is true for n = r

and

Now we need to prove that the result is true for n = r + 1

and

By using the values of and we have and . Hence, by the principle of mathematical induction, it is proved that and . Further in the notation and is the discretization of time while i represents the space variable. The same process can be performed by allotting different values to i, as i = 0 in the first step, then replacing it with i = 1, 2, 3, ···N − 1 for the hypothesis step, and lastly, we can easily prove the results for i = N, the inductive step. □

3.4. Stability Analysis of Proposed Finite Difference Method

The Von Neumann technique is once again applied to the proposed scheme to check the stability. For this we have

Put into the above scheme and use linearization, and we have

which implies that and hence ξ < 1. The scheme for Equation (5) is

In a similar fashion, we substitute into the above and apply linearization.

After simplification, we have

which implies that ξ < 1 as ξ−m < 1.

3.5. Consistency Analysis

While considering the series expansion purposed by Taylor in our proposed FD method, we produced a consistency analysis:

Similarly, for the Forward Euler technique we obtained the expression

Now, putting the values , and into the above and simplifying them, we get

Put k′ = handh → 0, where the expression given above takes the form as (4).

The proposed technique for a susceptible compartment is

Now, putting the values , and into the above and simplifying them, we get

Put k′ = h3 with h approaching zero 0, and the equation given above reshapes as (4). The Taylor series expansions of , and are

The forward Euler technique for an infectious compartment is

Now, putting the values of , and into the above and simplifying them, we get,

Putting k′ = h, as h converges to zero, the equation given above becomes the same as (5).

The proposed technique for an infectious compartment is

Now, putting the values of , and into the above and simplifying them, we get,

letting h → 0 and setting the k′ = h3 above exactly as (5).

4. Numerical Test and Simulations

In this section, we present the example related to the model and furnished the numerical simulations with some suitable conditions as mentioned below.

with f1(x) = 0.8 and f2(x) = 0.2 and boundary couples set of conditions are no flux.

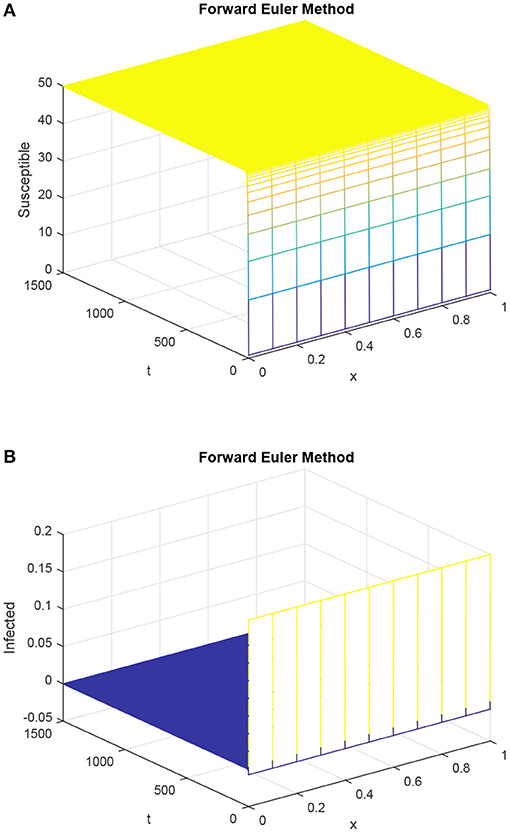

Figure 1 tells us the story about the false behavior of the forward Euler technique. The graph (B) of the infected population in this figure describes the negative values of the solution. The negative solution is not a part of the continuous model as population sizes always remain positive.

Figure 1. Susceptible population and infected population with the help of Euler method (forward), where dynamics of S and I as shown in (A,B) with h = 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 1.5. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

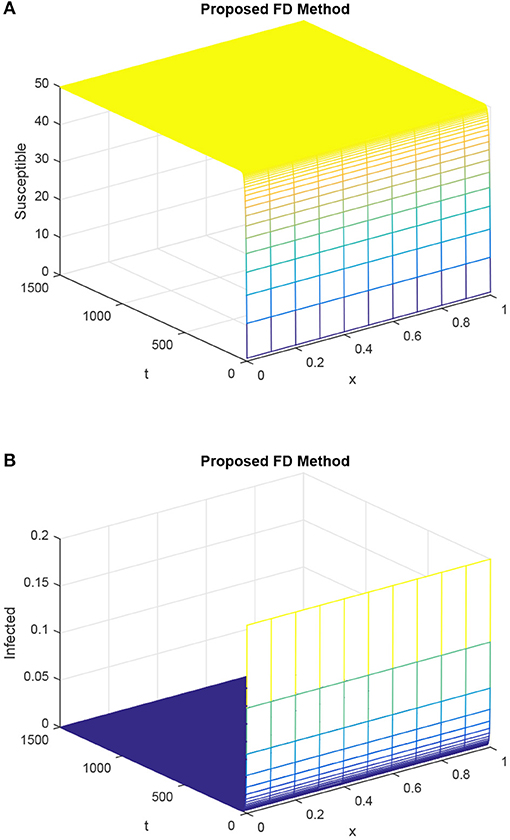

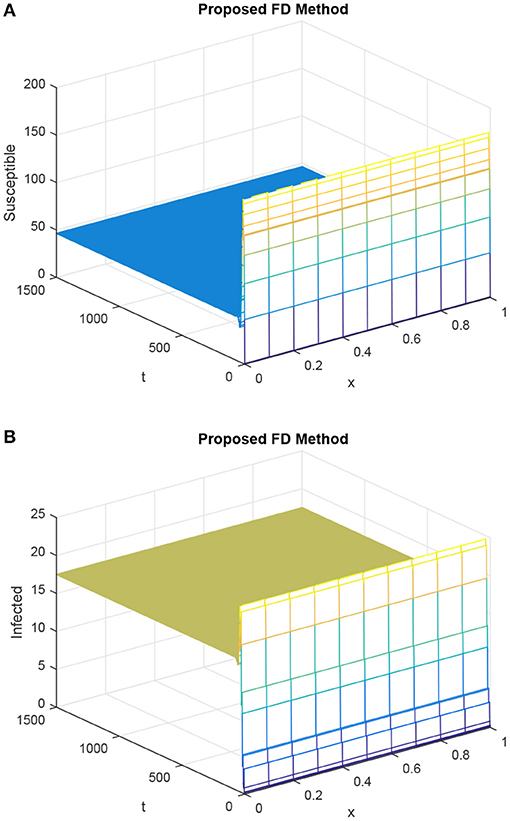

As in Figure 1, the same values of the parameters are considered in Figure 2. The simulations of the proposed technique in Figure 2 are presented for the uninfected point and demonstrate that it preserves the positivity of the solution, which is the part of the solution of the delayed epidemic model with diffusion.

Figure 2. Susceptible population and infected population dynamics by our proposed FD technique with the time step h = 0.1, R1, and R2 kept equal and selected as 0.15, τ = 1.5. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

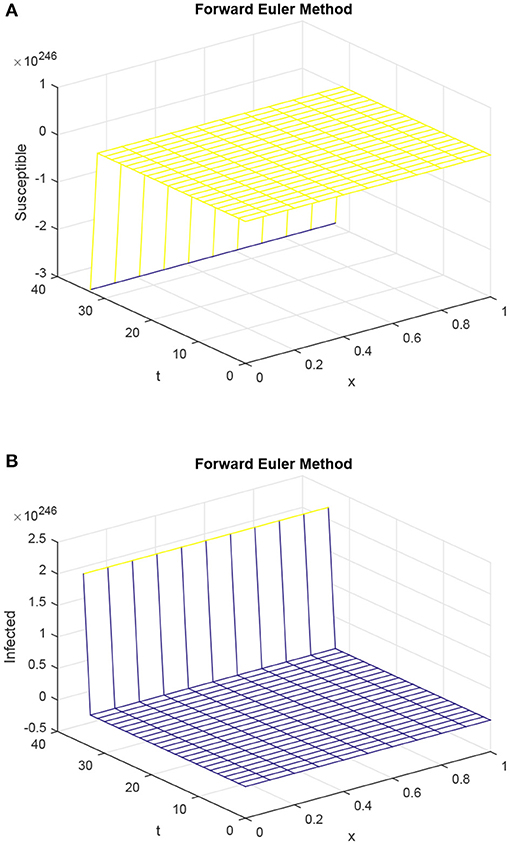

Once again, the forward Euler technique could not retain the actual behavior of the diffusive epidemic model of HIV/AIDS, as shown in Figure 3. In the Figure 3 graphs, the simulations are taken at infected steady states and the reproductive value exceeded one. The IS states are stable, and so the system (3)–(5) converges to it. Forward Euler technique, however, fails in this regard and shows the divergence behavior.

Figure 3. Graphs of susceptible population and infected population using Euler method for forward difference, with h = 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 1.5. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

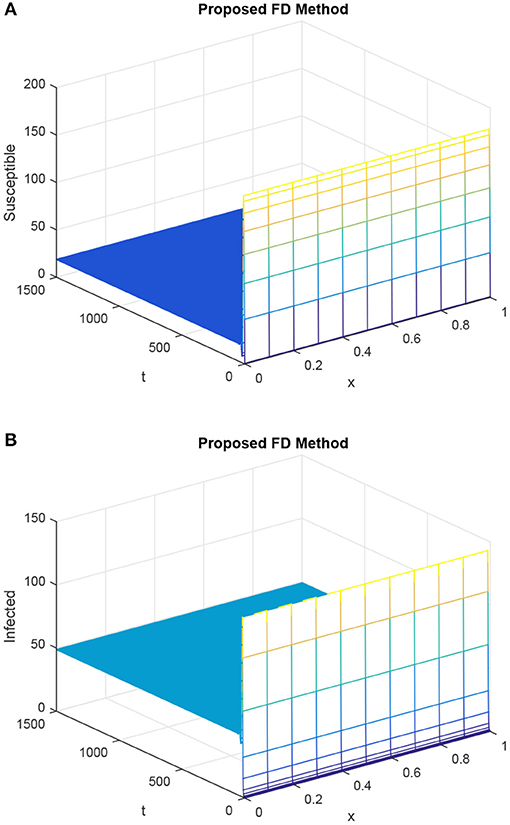

As compared to the forward Euler technique, the proposed technique approached the IS state and sustained the positive solution of the continuous delayed reaction–diffusion epidemic system, as depicted in Figure 4. It revealed that the proposed technique preserved the positive solution of the given delayed reaction–diffusion epidemic system. The proposed technique also captured the stability of true steady states, which are possessed by the HIV/AIDS delay epidemic model.

Figure 4. Sketch of susceptible population and infected population, giving the selection of values as h = 0.1 and choosing R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 1.5 (with proposed scheme). (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

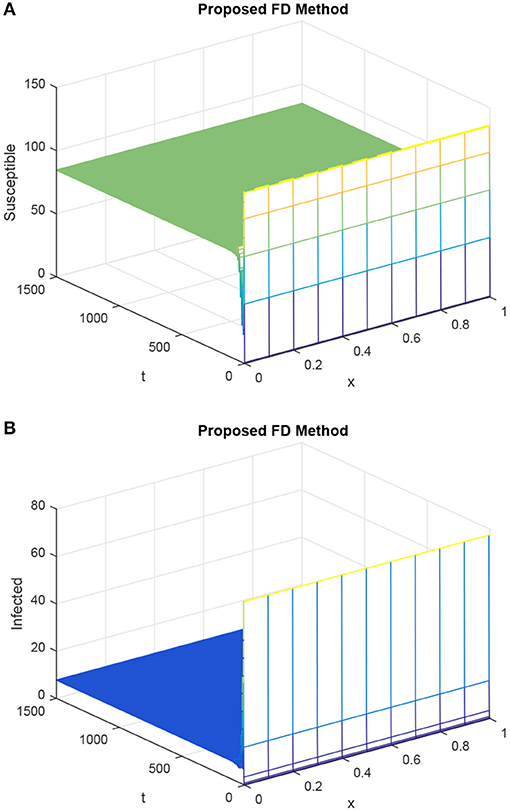

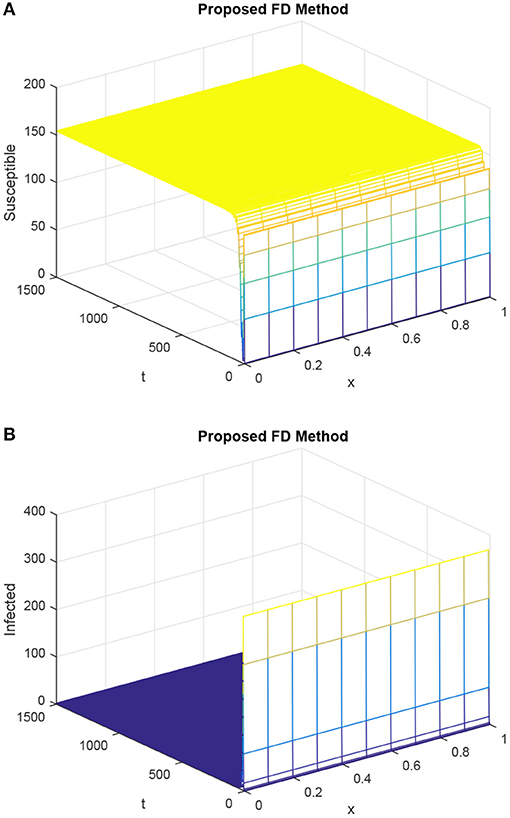

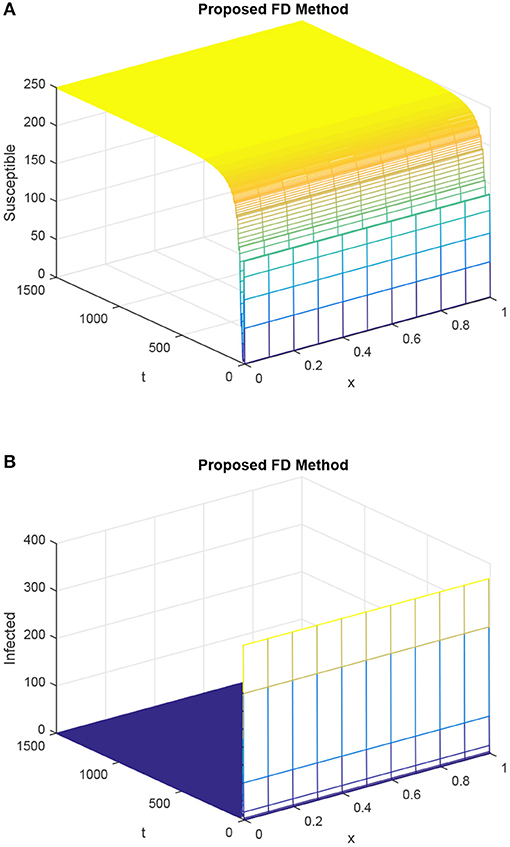

In Figures 5–8, we study the behavior of delay factor τ on HIV/AIDS dynamics. All the graphs in these figures are the graphs of the susceptible and infected population at the uninfected steady state. We vary the value of delay factor τ from 6 to 15. When the delay factor is increased, the infection in the population is decreased and susceptibility is increased. This discussion validates the fact that delay factor help to control the spread of disease in HIV/AIDS dynamics.

Figure 5. Dynamics of susceptible population and infected population considering h as 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 6. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

Figure 6. Graphs (A,B) for susceptible population and infected population considering the proposed method, given h = 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 9. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

Figure 7. Mesh graphs for the susceptible population and infected population by our proposed method, giving the parametric values as h = 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 12. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

Figure 8. Discretized graphs of the susceptible population and infected population for our designed FD scheme, giving h = 0.1 and R1 = R2 = 0.15, τ = 15. (A) Mesh graph of S. (B) Mesh graph of I.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we have proposed the use of the delay epidemic model of HIV/AIDS dynamics with diffusion and applied two numerical techniques to assess the behavior of the solution of the continuous reaction–diffusion system with a delay factor. The techniques used to solve the proposed epidemic system are the well-known forward Euler technique and proposed unconditionally positivity preserving technique. The reaction–diffusion delayed HIV/AIDS epidemic model revealed a positive solution as the variables involved were the population sizes. The forward Euler technique, however, provided the negative values of the solution, which were not the part of the solution of the model under study. On the other hand, the proposed technique exhibited the same behavior as the solution of the HIV/AIDS delayed reaction–diffusion epidemic model. It preserved the positivity of the solution unconditionally and showed the convergence toward the true steady states of the HIV/AIDS reaction–diffusion system with a delay, as demonstrated in the simulations. The control of the spread of disease with the help of a delay factor was verified by the simulations. In future the proposed method will be applied to multi-dimensional delayed reaction diffusion epidemic models. Similarly, structure-preserving numerical techniques may be designed for fractional reaction diffusion systems with and without a time delay as well as stochastic models associated with diffusion and time delay. Furthermore, the Lie algebra approach may also be investigated for the above mentioned models [53, 54].

Author Contributions

MR and NA: conceptualization. MJ and NA: methodology. NA: software. DB and MR: validation. MJ and NA: formal analysis. MR and MAR: investigation. MAR: resources. MR: data curation. MJ: writing–original draft preparation. DB, MR, and MAR: writing–review and editing. MR, NA, and MJ: visualization. MAR and MR: supervision and project administration.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Martcheva M. An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology. Vol. 61. New York, NY: Springer (2015).

2. Liu Z. Dynamics of positive solutions to SIR and SEIR epidemic models with saturated incidence rates. Nonlin Anal Real World Appl. (2013) 14:1286–99. doi: 10.1016/j.nonrwa.2012.09.016

3. Liu J. Bifurcation analysis for a delayed seir epidemic model with saturated incidence and saturated treatment function. J Biol Dyn. (2019) 13:461–80. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2019.1631965

4. Ruschel S, Pereira T, Yanchuk S, Young L. An SIQ delay differential equations model for disease control via isolation. J Math Biol. (2019) 79:1–31. doi: 10.1007/s00285-019-01356-1

5. Cai L, Li X, Ghosh M, Guo B. Stability analysis of an HIV-aids epidemic model with treatment. J Comput Appl Math. (2009) 229:313–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2008.10.067

6. Young LS, Ruschel S, Yanchuk S, Pereira T. Consequences of delays and imperfect implementation of isolation in epidemic control. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:3505. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39714-0

7. Chan Chí N, Ávila Vales E, García Almeida G. Analysis of a HBV model with diffusion and time delay. J Appl Math. (2012) 2012:1–25. doi: 10.1155/2012/578561

8. Elaiw AM, Raezah AA, Alo BS. Dynamics of delayed pathogen infection models with pathogenic and cellular infections and immune impairment. AIP Adv. (2018) 8:025323. doi: 10.1063/1.5023752

9. Beretta E, Takeuchi Y. Global stability of an SIR epidemic model with time delays. J Math Biol. (1995) 33:250–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00169563

10. Kadder A. On the dyanmics of a delayed sir epiemic model with a modified saturated incidence rate. Electron J Differ Equat. (2009) 1:1–7.

11. Zhang J, Jin Z, Yan J. Stability and Hopf bifurcation in a delayed competition system. Nonlin Anal Theor Methods Appl. (2009) 70:658–670. doi: 10.1016/j.na.2008.01.002

12. Abta A, Kadder A, Alaoui TH. Global stability for delay SIR and SEIR epidemic models with saturated incidence rates. Electron J Differ Eqaut. (2012) 2012:1–13.

13. Ma Z, Zhou Y, Wang W. Mathematical Models and Dynamics of Infectious Diseases. Beijing: China Sciences Press (2004).

14. Li J, Sun GQ, Jin Z. Pattern formation of an epidemic model with time delay. Phys A. (2014) 403:100–9. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2014.02.025

15. Sun GQ, Chakrabort A, Liu QX, Jin Z, Anderson KE, Li BL. Influence of time delay and nonlinear diffusion on herbivore outbreak. Commun Nonlin Sci Numer Simul. (2014) 19:1507–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2013.09.016

16. Sun G, Jin Z, Liu QX, Li L. Pattern formation in a s-i model with nonlinear incidence rates. J Stat Mech. (2007) 11:P11011. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2007/11/P11011

17. Sun GQ, Jin Z, Liu QX, Li L. Chaos induced by breakup of waves in a spatial epidemic model with nonlinear incidence rate. J Stat Mech. (2008) 8:P08011. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/08/P08011

18. Wang K, Wang W, Song S. Dynamics of an hbv model with diffusion and delay. J Theor Biol. (2008) 253:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.11.007

19. Xu R, Ma ZE. An HBV model with diffusion and time delay. J Theor Biol. (2009) 257:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.01.001

20. Capasso V, Maddalena L. A nonlinear diffusion system modeling the spread of oro-faecal diseases. In: Lakshmikanthan V, editor. Nonlinear phenomena in mathematical science. New York, NY: Academic Press (1981), 207–217.

21. Capasso V, Maddalena L. Convergence to equilibrium states for a reaction-diffusion system modeling the spatial spread of a class of bacterial and viral diseases. J Math Biol. (1981) 13:173–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00275212

22. Thieme HR, Zhao XQ. Asymptotic speeds of spread and traveling waves for integral equations and delayed rection-diffusion models. J Differ Equat. (2003) 195:430–70. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0396(03)00175-X

23. Al-khedhairi A, Matouk AE, Khan I. Chaotic dynamics and chaos control for the fractional-order geomagnetic field model. Chaos Solit Fract. (2019) 128:390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2019.07.019

24. Abro KA, Khan I, Nisar KS. Novel technique of Atangana and Baleanu for heat dissipation in transmission line of electrical circuit. Chaos Solit Fract. (2019) 129:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2019.08.001

25. Tassaddiq A, Khan I, Nisar KS. Heat transfer analysis in sodium alginate based nano-fluid using MoS2 nano-particles Atangana–Baleanu fractional model. Chaos Solit Fract. (2020) 130:109445. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2019.109445

26. Aleem M, Asjad MI, Shaheen A, Khan I. MHD Influence on different water based nanofluids (TiO2, Al2O3, CuO) in porous medium with chemical reaction and Newtonian heating. Chaos Solit Fract. (2020) 130:109437. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2019.109437

27. Khan MA, Saddiq SF, Islam S, Khan I, Shafie S. Dynamic behavior of leptospirosis disease with saturated incidence rate. Int J Appl Comput Math. (2016) 2:435–52. doi: 10.1007/s40819-015-0102-2

28. Khan MA, Ullah S, Ching DL, Khan I, Islam S, Gul T. A mathematical study of an epidemic disease model spread by rumors. J Comput Theor Nanosci. (2016) 13:2856–66. doi: 10.1166/jctn.2016.4929

29. Kermack WO, McKcndrick AG. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc R Soc A. (1927) 115:700–21.

30. Elaiw AM, AlShamrani NH. Stability of an adaptive immunity pathogen dynamics model with latency and multiple delays. Math Method Appl Sci. (2018) 36:125–42. doi: 10.1002/mma.5182

31. Zhang F, Li J, Zheng C, Wang L. Dynamics of an HBV/HCV infection model with intracellular delay and cell proliferation. Commun Nonlinear Sci Numer Simul. (2017) 42:464–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2016.06.009

32. Roy PK, Chatterjee AN, Greenhalgh D, Khan QJA. Long term dynamics in a mathematical model of HIV-1 infection with delay in different variants of the basic drug therapy model. Nonlinear Anal Real World Appl. (2013) 14:1621–33. doi: 10.1016/j.nonrwa.2012.10.021

33. Hobiny AD, Elaiw AM, Almatrafi AA. Stability of delayed pathogen dynamics models with latency and two routes of infection. Adv Differ Equat. (2018) 2018:276. doi: 10.1186/s13662-018-1720-x

34. Manna K, Hattaf K. Spatiotemporal dynamics of a generalized HBV infection model with capsids and adaptive immunity. Int J Appl Comput Math. (2019) 5:65. doi: 10.1007/s40819-019-0651-x

35. Hattaf K, Yousfi N. A generalized HBV model with diffusion and two delays. Comput Math Appl. (2015) 69:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.camwa.2014.11.010

36. Kang C, Miao H, Chen X, Xu J, Huang D. Global stability of a diffusive and delayed virus dynamics model with Crowle-Martin incidence function and CTL immune response. Adv Differ Equat. (2017) 2017:324. doi: 10.1186/s13662-017-1332-x

37. Li D, Ma W. Asymptotic properties of a HIV-1 infection model with time delay. J Math Anal Appl. (2007) 335:683–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmaa.2007.02.006

38. Kaddar A, Abta A, Alaoui HT. A comparison of delayed SIR and SEIR epidemic models. Nonlin Anal Model Cont. (2011) 16:181–90. doi: 10.15388/NA.16.2.14104

39. Abdullahi YM, Nweze O. A simulation of an sir mathematical model of HIV transmission dynamics using the classical Euler's method. Shiraz Med J. (2011) 12:196–202.

40. Cooke KL. Stability analysis for a vector disease model. Rocky Mount J Math. (1979) 9:31–42. doi: 10.1216/RMJ-1979-9-1-31

41. Wilson EB, Worcester J. The law of mass action in epidemiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1945) 31:24–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.31.1.24

42. Ali MA, Rafiq M, Ahmad MO. Numerical analysis of a modified SIR epidemic model with the effect of time delay. Punjab Univ J Math. (2019) 51:79–90.

43. Geng Y, Xu J, Hou J. Discretization and dynamic consistency of a delayed and diffusive viral infection model. Appl Math Comput. (2018) 316:282–95. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2017.08.041

44. Hattaf K, Yousfi N. A numerical method for a delayed viral infection model with general incidence rate. J King Saud Univ Sci. (2016) 28:368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2015.10.003

45. Manna K. A non-standard finite difference scheme for a diffusive HBV infection model with capsids and time delay. J Differ Equat Appl. (2017) 23:1901–11. doi: 10.1080/10236198.2017.1371147

46. Orbele HJ, Pesch HJ. Numerical treatment of delay differential equations by Hermite interpolation. Numer Math. (1981) 37:235–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01398255

47. Shah R, Hassan K, Kuman P, Arif M, Baleanu D. Natural transform decomposition method for solving fractional-order partial differential equations with proportional delay. Mathematics. (2019) 7:532. doi: 10.3390/math7060532

48. Xu J, Geng Y. Dynamic consistent NSFD scheme for a delayed viral infection model with immune response and nonlinear incidence. Discrete Dyn Nat Soc. (2017) 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1155/2017/3141736

49. Ahmed N, Rafiq M, Rehman MA, Iqbaland MA, Iqbal MS. Numerical modeling of three dimensional Brusselator reaction diffusion system. AIP Adv. (2019) 9:015205. doi: 10.1063/1.5070093

50. Ahmed N, Tahira SS, Rafiq M, Rehman MA, Ali M, Ahmad MO. Positivity preserving operator splitting nonstandard finite difference methods for SEIR reaction diffusion model. Open Math. (2019) 17:313–30. doi: 10.1515/math-2019-0027

51. Ahmed N, Jawaz M, Rafiq M, Rehman MA, Ali M, Ahmad MO. Numerical modeling of SEIQV epidemic model with saturated incidence rate. J Appl Environ Biol Sci. (2018) 8:17–29.

52. Mickens RE. Nonstandard Finite Difference Models of Differential Equations. London: World Scientific (1994).

53. Shang Y. A Lie algebra approach to susceptible-infected-susceptible epidemics. Electron J Differ Equat. (2012) 233:1–7.

Keywords: epidemic model with diffusion, time delay, HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), positivity, finite difference method, simulations

Citation: Jawaz M, Ahmed N, Baleanu D, Rafiq M and Rehman MA (2020) Positivity Preserving Technique for the Solution of HIV/AIDS Reaction Diffusion Model With Time Delay. Front. Phys. 7:229. doi: 10.3389/fphy.2019.00229

Received: 25 September 2019; Accepted: 10 December 2019;

Published: 15 January 2020.

Edited by:

Mustafa Inc, Firat University, TurkeyReviewed by:

Ilyas Khan, Ton Duc Thang University, VietnamYilun Shang, Northumbria University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2020 Jawaz, Ahmed, Baleanu, Rafiq and Rehman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nauman Ahmed, bmF1bWFuLmFobWQwMUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Muhammad Jawaz1,2

Muhammad Jawaz1,2 Nauman Ahmed

Nauman Ahmed Dumitru Baleanu

Dumitru Baleanu Muhammad Rafiq

Muhammad Rafiq