- 1Key Laboratory of Optoelectronic Devices and Systems of Ministry of Education and Guangdong Province, College of Physics and Optoelectronic Engineering, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 2International Collaborative Laboratory of 2D Materials for Optoelectronics Science and Technology of Ministry of Education, SZU–NUS Collaborative Innovation Center for Optoelectronic Science & Technology, Institute of Microscale Optoelectronics, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 3Department of Physical Education, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

Under the excitation of ultraviolet, X-ray, and mechanical stress, intense orange luminescence (Mn2+, 4T1 → 6A1) can be generated in Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O crystal in orthorhombic space group of Pmn21. Herein, the multiple energy conversion in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+, that is, photoluminescence (PL), X-ray-induced luminescence, and mechanoluminescence, is investigated. Insight in luminescence mechanisms is gained by evaluating the Mn2+ concentration effects. Under the excitation of metal-to-ligand charge-transfer transition, the most intense PL is obtained. X-ray-induced luminescence shows similar features with PL excited by band edge UV absorption due to the same valence band to conduction band transition nature. Benefiting much from trap levels introduced by Mn2+ impurities, the quenching behavior mechanoluminescence is more like the directly excited PL from Mn2+ d-d transitions. Interestingly, this concentration preference leads to varying degrees of spectral redshift in each mode luminescence. Further, SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ exhibits a good linear response to the excitation power, which makes it potential candidates for applications in X-ray radiation detection and mechanical stress sensing.

Introduction

Luminescent materials could somehow absorb electrical, optical, chemical, thermal, or mechanical energy and turn it into light emission through a radiative transition. In the last centuries, researchers have been working persistently on optimizing of preparation technique, exploring new materials to meet the rising demand for high-performance luminescent materials in applications such as lighting (Meyer and Tappe, 2015; Xu et al., 2016; Zak et al., 2017), display (Withnall et al., 2011; Ballato et al., 2013), sensing (Eliseeva and Bunzli, 2010; Olawale et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014), optoelectronics (Li et al., 2015, 2017), and anti-counterfeiting (Zhang et al., 2018a). While pursuing its state-of-the-art materials by realizing one mode of energy transformation, one single material that could efficiently transform multiple types of energy to light emission has entered people's vision. These materials may bring to life many new appealing applications in the interdisciplinary fields (Singh et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018b, 2020; Jiang et al., 2019; Sang et al., 2019).

During the past decades, mechanoluminescent materials with the capability of converting mechanical energy to light emission are attracting more and more attention for their potential applications in stress sensing, anti-counterfeiting, display, structure fatigue diagnosis, and flexible optoelectronics (Chandra and Chandra, 2011; Jeong et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019; Wang C. et al., 2019; Wang X. et al., 2019; Zuo et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). On the other hand, almost immediately after the discovery of X-rays, people started eagerly to find efficient X-ray phosphors or scintillators that absorb X-ray and emit light (Blasse, 1994; Büchele et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2020). With a strong ability to absorb X-ray photons, impurity-doped ML materials may also be good scintillators with intense X-ray-induced emission and find their application in X-ray detection. Recently, much effort has been independently made to optimize the performance of ML and X-ray phosphors. Starting from the two classic ML materials, that is, Eu2+-doped SrAl2O4 and Mn2+/Cu2+-doped ZnS, in the early stage, many impurity-doped systems have been discovered (Peng et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2019). Among these, some typical oxysulfides notably enriched the color of ML emission due to its good acceptance for a large number of activators (Zhang et al., 2013, 2015). It is proved that some new oxysulfide semiconductors that doped with luminescent ions, for instance, transitional metals and lanthanide ions doped CaZnOS (Huang, 2016; Huang et al., 2017; Du et al., 2019), SrZnOS (Chen et al., 2020), and BaZnOS (Li et al., 2016) single compounds as well as CaZnOS-ZnS heterojunctions (Peng et al., 2020) show novel ML performances that result in diverse applications. Meanwhile, some oxysulfides, such as Gd2O2S-based luminescent material (Büchele et al., 2015), has been commercialized and confirmed to be good X-ray phosphors. As oxysulfides show a strong ability to absorb high-energy X-ray photons, they may be good scintillators to meet the rising demand for radiation detection materials as well.

SrZn2S2O, as a newly discovered oxysulfide semiconductor with close-packed corrugated double layers of ZnS3O tetrahedron in its crystal structure, was first reported by Hans-Conrad zur Loye's group (Tsujimoto et al., 2018) and found to function as a high-stable photocatalyst capable of reducing and oxidizing water (Nishioka et al., 2019). Deducing from its non-central symmetry crystal structure and appropriate band structure, impurity-doped SrZn2S2O could have good ML performance, which was already proved recently (Chen et al., 2020). Herein, we report Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O material could simultaneously respond to UV light or X-ray exposure or mechanical actions with intense orange emission and realize multiple-energy conversions. Besides mechanical stimulation, SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ can also respond to X-ray exposure with strong visible emission. The ML performance is optimized by choosing the optimal preparation condition and tuning the doping concentration. Strong relevance between ML intensity and the applied mechanical force makes SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ a good candidate for dynamic stress visualization. Notably, the differences in quenching behavior provide us a better understanding of the ML process. This multimode energy conversion behavior might be used in manufacturing future sensing devices.

Experimental

Materials Preparation

The samples were prepared by using a high-temperature solid-state reaction. To obtain x mol% Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O, that is, SrZn2(1−x%)S2O:2x% Mn2+ (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8), high purity of ZnS (99.99%, Aladdin), SrCO3 (99.9%, Aldrich), and MnCO3 (>99%, Sinopharm Group Co. Ltd.) with mole ratio of 2-2x%:1:2x%, were used as starting materials. A total of 20 g of raw materials was precisely weighed and then thoroughly mixed by wet grinding in absolute ethanol. After dried in an oven at 80°C, the raw materials were calcined at 1,000°C for 4 h in Ar atmosphere (purity, 99.99%). The sintered product was grounded into fine powders for subsequent characterization.

Mechanoluminescence Film Fabrication

A “suspension deposition” method is applied to fabricate the mechanoluminescence (ML) film for ML test and exhibition. In a typical case, 0.2 g SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ ML powder and 0.06 g UV curing adhesive (LEAFTOP 9307) were ultrasonically dispersed in ethanol, followed by a rapid transfer into a 3 × 3-cm square frame stainless mold placed on one piece of the ethylene-vinyl acetate-covered poly(ethylene terephthalate) film in a laminating film (Deli, no. 3817). The mold was removed after the volatilization of ethanol; then, the two pieces of ethylene-vinyl acetate-covered poly(ethylene terephthalate) films were folded together very carefully. Subsequently, the film was exposed in UV light to solidify the adhesive and then packaged by going through a thermal laminator.

Characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded by a Bruker D2 phase X-ray diffraction analyzer. Scanning electron microscope images were obtained from a 3 Hitachi SU 8020 scanning electron microscope. Energy-dispersive X-ray element maps were obtained on a HOBIRA EMAX X-ray detector. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured by Hitachi F-4600 spectrophotometer equipped with an R928 photomultiplier detector. The ML emission spectra were recorded by a home-built measuring apparatus with a linear motor, digital push–pull gauge, and QE65pro fiber optic spectrometer (Ocean Optics). The X-ray-induced emission spectra were obtained by Omni-λ 300i spectrograph (Zolix) equipped with an X-ray tube (Model RACA-3, Zolix Instruments Co., Ltd., Beijing, China).

To acquire the ML spectra, we stick the ML film on a quartz glass plate firmly fixed on the table. On the front side, the digital push–pull gauge with a metal attachment is fixed on a platform connected to a linear motor. On the backside, the fiber connected with the QE65pro fiber optic spectrometer is fixed on the same platform over against the metal attachment. The push–pull gauge tunes the acting force of the metal attachment on ML film, and the programmed linear motor controls the movement of the platform. During the test, the motion of metal attachment on ML film generates light emission, whereas the fiber collects the signal synchronously.

Results and Discussion

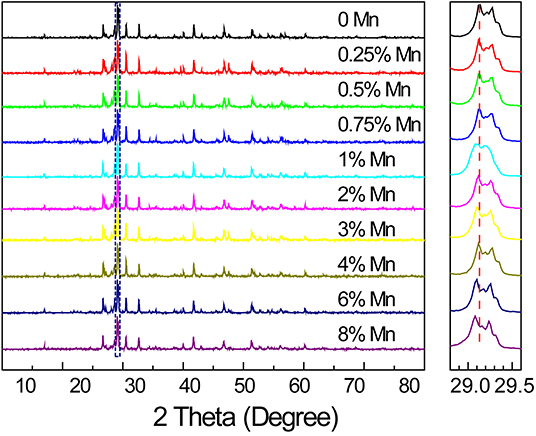

We found that 1,000°C was the most suitable temperature for the preparation of SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ to get a good crystallinity while avoiding any decomposition (Supplementary Figure 1). The experimental XRD pattern of the sample calcined at 1,000°C for 4 h matches well with the theoretical calculated powder X-ray diffraction result based on work of Hans-Conrad Tsujimoto et al. (2018), which indicates that the single phase of SrZn2S2O in orthorhombic space group of Pmn21 (no. 31) was successfully synthesized (Supplementary Figure 2). In the SrZn2S2O crystal structure, each Zn atom is coordinated with 1 O atom and 3 S atoms as ZnS3O tetrahedron, whereas Sr2+ ions vertically separate close-packed corrugated double layers of ZnS3O tetrahedron. Mn2+ will occupy the Zn2+ site due to their close radius (Mn2+ is slightly larger than Zn2+) and similar chemical properties. As a result, the XRD peaks show a slight shift toward lower angle in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ with increasing Mn2+-doping concentration, and there is no second phase found even when Mn2+ concentration is rather high (Figure 1). The success in the synthesis of heavily doped SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ makes it easier for further performance tuning to get the desired material performances. After grinding and sifting, we got fine powder several micrometers in size with no regular shape for all the characterization and property tests. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy verifies the presence of the doped Mn element and its uniform distribution together with Zn, S, Sr, and O elements as a single phase SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 1. X-ray diffraction patterns of SrZn2(1−x%)S2O:2x% Mn2+ with a series of Mn2+ concentrations (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8), and an enlargement of the highest diffraction peak marked by a dotted rectangle is given in the right side.

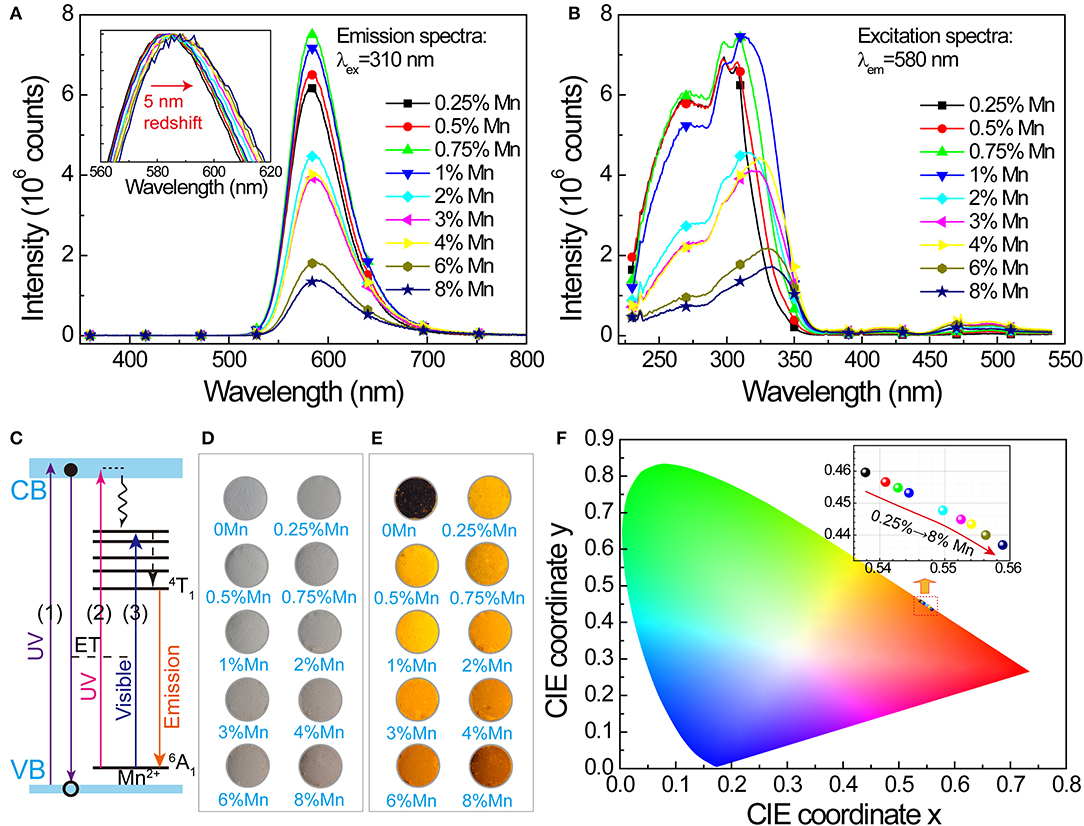

PL properties of Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O are investigated. Under ultraviolet excitation at 310 nm (Figure 2A), a broadband orange emission (~520–700 nm) centered at about 580 nm corresponding to 4T1 → 6A1 transition of Mn2+ in SrZn2S2O lattice. With increasing Mn2+-doping amount, the emission band shows a slight redshift of about 5 nm and a slightly raising band tail at long wavelength due to reduced energy difference by an exchange interaction effect between two neighboring Mn2+ cations (Barthou, 1994; Vink et al., 2001). The emission intensity increases at lower Mn2+ concentrations, and then, a fast decrease is witnessed due to the comprehensive effects of excitation efficiency changes and concentration quenching. The corresponding excitation spectra (Figure 2B) comprise a broad UV band including band edge absorption of SrZn2S2O host at ~270 nm and metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCBCT) (Norberg et al., 2004; Badaeva et al., 2011) absorption of Mn2+ centered at ~320 nm and several smaller bands in the visible light region due to d-d transitions of Mn2+. Among these, the UV band, or more precisely, the MLCBCT band of Mn2+ shows a distinct redshift. Correspondingly, three excitation routes are proposed in the luminescence mechanism depicted in Figure 2C. Namely, route 1 represents the excitonic transition (SrZn2S2O VB → CB transition), route 2 represents the charge-transfer states transition (Mn2+ 3d → CB transition), and route 3 represents d-d transitions of Mn2+ (Mn2+: 6A1(6S) → 4E(4D), 4T2(4D), (4A1,4E)(4G),4T2(4G) or 4T1(4G)), whereas notably, each excitation routes performs inconsistently with increasing Mn2+-doping concentration (Supplementary Figure 4). Because strong concentration quenching of the orange emission occurs when Mn2+ concentration is higher than 4% for Mn2+ direct excitation (route 3), the concentration effects of routes 1 and 2, with a much lower quenching concentration, should be dominated by the host lattice-related excitation process and the energy transfer process.

Figure 2. Photoluminescence in SrZn2(1−x%)S2O:2x% Mn2+, with x = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8. (A) PL spectra under 310 nm excitation. Inset shows a 5-nm redshift of the normalized PL band with increasing doping concentration. (B) Corresponding PLE spectra monitoring 580-nm emission. (C) Luminescence mechanism of SrZn2S2O:Mn expressed by energy level diagram. Optical images of the samples: (D) under daylight lamp lighting and (E) illuminated by 254-nm UV lamp. (F) CIE coordinate (x, y) values obtained from the PL spectra under 310-nm excitation; the inset shows the enlargement of the marked area.

Whereas, the undoped SrZn2S2O is white under daylight lamp lighting, with increasing Mn2+-doping concentration, SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ gets darker and darker pink colors (Figure 2D) owing to the slight absorption of blue and green light by Mn2+ d-d transitions. Illuminated by a 254-nm UV lamp, the undoped SrZn2S2O shows no luminescence, whereas varied orange emission is observed in these doped samples (Figure 2E). Figure 2F displays the chromaticity diagram with International Commission on Illumination (CIE) coordinate (x, y) values obtained from the PL spectra under excitation at 310 nm. All chromaticity points locate in the orange region between the yellow and red region, with increasing Mn2+ concentration; the CIE coordinate (x, y) varies systematically from (0.538, 0.460) to (0.559, 0.437) due to the redshift of PL. To summarize, SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ realizes light energy conversion, especially, UV to orange light conversion with Mn2+ concentration around 1%.

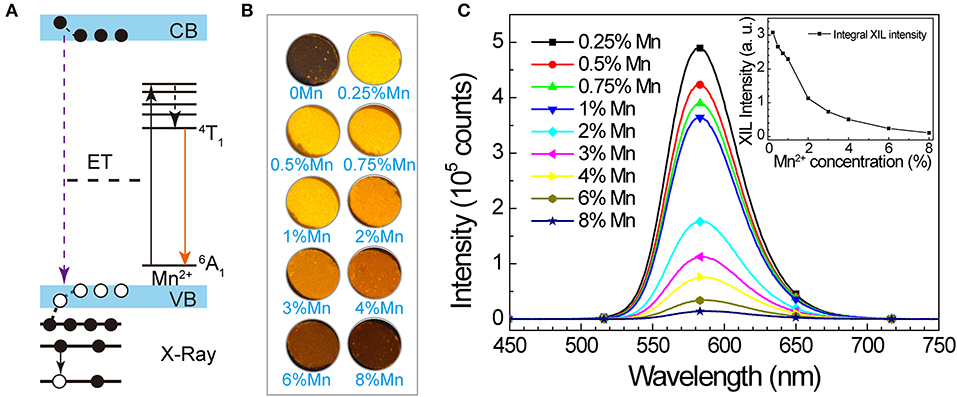

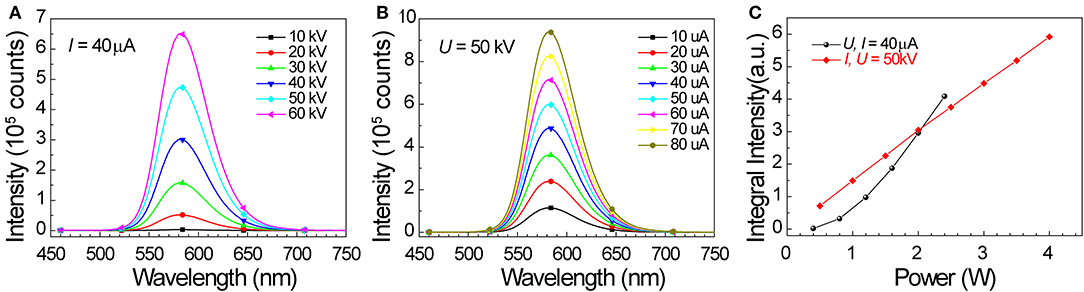

We also studied the potential of SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ in energy conversion from X-ray to visible light. When SrZn2S2O is irradiated by X-ray, a large number of electron-hole pairs will be generated mainly via photoelectric effect when absorbing X-ray energy, and later, Mn2+ is excited by the energy transferred from the electron-hole pair, followed by an orange light emission process (Figure 3A) (Blasse, 1994; Cao et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Observed under X-ray irradiation (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure 4, and Supplementary Video 1), 0.25% Mn2+-doped sample exhibits the most intense orange emission, and the X-ray-induced luminescence (XIL) decreases with increasing Mn2+ concentration. This trend is verified by the XIL spectra (Figure 3C) obtained under excitation of X-ray source operating at U = 50 kV and I = 40 μA, whereas a slight redshift by 3 nm of XIL band is observed. As X-ray irradiation produces electron-hole pairs, which is similar to UV band-edge excitation (PLE route 1), a similar concentration effect is predictable (Supplementary Figure 5). The severe concentration quenching most probably caused by band structure changes of SrZn2S2O brought by Mn2+ doping through the so-called Auger de-excitation effect (White et al., 2011; Peng et al., 2012) resulting in remarkably increased non-radiative transition probability. Lightly Mn2+ impurity-doped is favored for SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ to fulfill the X-ray to visible light energy conversion. We further investigated XIL with varied X-ray source operating conditions (Figure 4). When the operating current is fixed at 40 μA (Figure 4A), the integral XIL intensity increased non-linearly with increasing operating voltage, as X-ray photon with higher energy can generate more electron-hole pairs (Scholze et al., 1996). While fixing operating voltage at 50 kV (Figure 4B), the integral XIL intensity is highly proportional to the operating current, which makes SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ material suite well for X-ray detection application.

Figure 3. X-ray-induced luminescence in SrZn2(1−x%)S2O:2x% Mn2+, with x = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8. (A) Scheme of proposed XIL mechanism in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+. (B) Optical images of the samples under X-ray irradiation. (C) X-ray-induced emission spectra under excitation of X-ray source operating at U = 50 kV and I = 40 μA. Inset shows the integral intensity in relation to Mn2+ concentration.

Figure 4. X-ray-induced emission spectra of 0.25% Mn doped SrZn2S2O under excitation of X-ray source operating at (A) I = 40 μA, U = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 kV, and (B) U = 50 kV, I = 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 μA. (C) Integral XIL intensity obtained from XIL spectra in (A,B) in relation to operating power (P = UI).

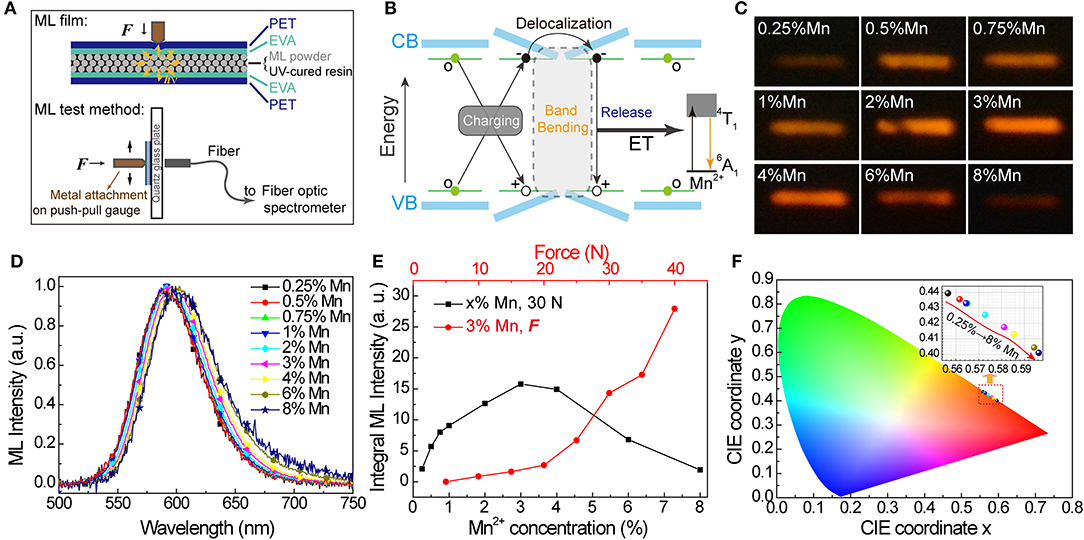

Besides UV light and X-ray energy, the potential of SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ to convert mechanical energy to orange light emission was reported recently by Rong-Jun Xie's group (Chen et al., 2020). As an important aspect of this multiple-energy conversion materials, the mechanoluminscence (ML) in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ was further investigated herein. We fabricated the ML films containing SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ ML powders for ML tests with a structure depicted in Figure 5A (the fabrication process and the test detail are described in the Experimental). Like ZnS:Mn2+ and CaZnOS:Mn2+ ML phosphors (Chandra et al., 2013; Tu et al., 2016), the ML of SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ is also reproducible with no need for extra energy supplement. Intrinsic vacancies and doped Mn2+ impurities bring in trap levels in the bandgap of SrZn2S2O. When mechanical strain is applied, the inner crystal piezopotential generated by a polarization of the non-central symmetry structure tilts the conduction and valence band. The trapped carriers might be released to the tilting energy band, followed by the recombination of electron-hole pairs and energy transfer to Mn2+. ML is produced when the excited Mn2+ returns to ground state through radiative transition (4T1 → 6A1) (Figure 5B) (Du et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020).

Figure 5. Mechanoluminescence in SrZn2(1−x%)S2O:2x% Mn2+, with x = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8. (A) Schematic diagram of the ML film structure and ML test method. (B) Scheme of proposed mechanism for mechanical-to-optical energy conversion. (C) Long exposure photos and (D) ML spectra (normalized) obtained under the same force of 30 N. (E) Integral ML intensity of ML spectra obtained under 30 N for all SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ samples and under varied forces for 3% Mn2+ doped SrZn2S2O. (F) CIE coordinate (x, y) values obtained from the ML spectra.

The Mn2+ concentration effects on ML properties were studied on homemade test equipment. Figure 5C shows the long exposure photos of ML when SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ samples were scraped with a force of 30 N (Figure 5C). Apparently, the ML brightness starts to decrease after increasing to a maximum when Mn2+ concentration is around 3%. The ML spectra were also obtained under 30 N. From the normalized ML spectra in Figure 5D, the redshift of the ML band moving from ~590 nm in 0.25% Mn to ~602 nm in 8% Mn is observed, which is larger than redshift in PL and XIL. Correspondingly, the CIE coordinate (x, y) moves from (0.557, 0.440) to (0.596, 0.401), as shown in Figure 5F. Noticed that severe quenching of ML happens only when the Mn2+-doping concentration is higher than 3% (Figure 5E), which is quite different from the behavior in emissions excited by UV light and X-ray (Supplementary Figure 5) but very similar to emission under excitation of Mn2+ d-d transition (PLE route 3). ML spectra of 0 Mn-doped SrZn2S2O were obtained under the same force of 30 N (Supplementary Figure 6). Pure SrZn2S2O (0 Mn) does not exhibit any ML at all under the test conditions (<50 N). Three percent of Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O is further investigated with changing forces (Figure 5E). The integral ML intensity shows a good linear relationship with the acting force at the beginning. With larger acting force, a bigger slope is observed due to the increased contact area resulting from the deformation of the testing ML film. This linear response to applied mechanical stress makes SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ a good candidate for stress sensing applications. We achieved visualization of dynamic pressure distribution during handwriting on ML film containing 3% Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O phosphors by extracting the grayscale of the recorded long-exposure image (Supplementary Figure 7 and Supplementary Video 2).

Previously, we, respectively, discussed the multiple energy conversion abilities in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ to transform UV, X-ray, or mechanical energy into orange light emission. Noticeably different quenching behaviors have been observed for PL, XIL, and ML with increasing Mn2+-doping concentration. XIL has the lowest quenching concentration, which has a similar trend with PL under host lattice excitation (PLE route 1). ML has the highest quenching concentration, which is more similar to PL under direct d-d excitation (PLE route 3). It is supposed that, to some extent, the ML performance of SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ benefits from trap levels introduced by Mn2+ doping, and this is quite different from the situation in CaZnOS:Mn2+ reported by Zhang et al. (2015). PL under metal-to-ligand charge transfer excitation (PLE route 2) has the mediate quenching concentration.

The average distance between two neighboring Mn2+ in SrZn2S2O lattice decreases with increasing Mn2+-doping concentration resulting in the formation of more and more Mn2+ pairs. Due to the exchange interaction effect, the energy difference between the ground state and the first excited state reduces when Mn2+ pairs are formed, leading to a redshift of emission band observed in all three energy conversion modes (Barthou, 1994; Vink et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2015). Further, the differences in XIL, PL, and ML color with the same concentration as well as their color ranges manipulated by Mn2+ concentration effect (Supplementary Figure 8) could be explained by the preferences in Mn2+ doping concentration. Take the case of ML who prefers high Mn2+ concentration; paired Mn2+ will always emit a larger proportion of longer wavelength photons, which makes ML more reddish than PL and XIL. As Mn2+ concentration increases, more Mn2+ pairs will form in SrZn2S2O lattice, and they emit an even larger proportion of longer wavelength photons leading to more redshift. The study of concentration quenching behaviors offers a better understanding of multiple energy conversion mechanisms in SrZn2S2O:Mn2+.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented Mn2+-doped SrZn2S2O crystals that display multimode energy conversion by turning X-ray, ultraviolet, and mechanical force energy into orange visible light energy via Mn2+ emission from 4T1 → 6A1 transition. The varied excitation mode in XIL, PL, and ML leads to performance sensitivity to doped Mn2+ impurities. By controlling Mn2+ concentration, we have obtained the most intense XIL with relatively low Mn2+ concentration and ML with much higher Mn2+ concentration, which both have a linear response to the corresponding excitation energy. The redshift of emission spectra is observed in luminescence from all three conversion modes, and the different preferences in Mn2+ impurities are believed to be responsible for the range of color change manipulated by Mn2+ doping concentration. This SrZn2S2O:Mn2+ with the ability of multimode energy conversion may find its application in X-ray, UV, and mechanical stress sensing and detection and multiple energy driving light sources and displays.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

RM and DP conceived the study, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. RM, SM, CW, ZW, YW, SQ, and DP carried out the material synthesis, characterization, and measurements. RM, YS, and DP analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61875136), Shenzhen Fundamental Research Project (201708183000260, JCYJ20190808170601664), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (No. 2020A1515011315), Shenzhen Peacock Plan (20171010874C), and Scientific Research Foundation as Phase II construction of high level University for the Youth Scholars of Shenzhen University (No. 000002110223).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Chen Xian for his help in PL tests, Mr. Jiang Fuchun for conducting the X-ray diffraction characterization, and the Electron Microscopy Center of Shenzhen University for the scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00752/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Video 1. X-ray induced luminescence of 0.25% Mn2+ doped SrZn2S2O.

Supplementary Video 2. Mechanoluminescence of the 3% Mn2+ doped SrZn2S2O.

References

Badaeva, E., May, J. W., Ma, J., Gamelin, D. R., and Li, X. (2011). Characterization of excited-state magnetic exchange in Mn2+-doped ZnO quantum dots using time-dependent density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 20986–20991. doi: 10.1021/jp206622e

Ballato, J., Lewis, J. S., and Holloway, P. (2013). Display applications of rare-earth-doped materials. MRS Bull. 24, 51–56. doi: 10.1557/S0883769400053070

Barthou, C. (1994). Mn2+ concentration effect on the optical properties of Zn2SiO4:Mn phosphors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 141:524. doi: 10.1149/1.2054759

Büchele, P., Richter, M., Tedde, S. F., Matt, G. J., Ankah, G. N., Fischer, R., et al. (2015). X-ray imaging with scintillator-sensitized hybrid organic photodetectors. Nat. Photonics 9, 843–848. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2015.216

Cao, J., Chen, W., Chen, L., Sun, X., and Guo, H. (2016). Synthesis and characterization of BaLuF5: Tb3+ oxyfluoride glass ceramics as nanocomposite scintillator for X-ray imaging. Ceramics Int. 42, 17834–17838. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.08.114

Chandra, V. K., and Chandra, B. P. (2011). Suitable materials for elastico mechanoluminescence-based stress sensors. Opt. Mater. 34, 194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2011.08.003

Chandra, V. K., Chandra, B. P., and Jha, P. (2013). Self-recovery of mechanoluminescence in ZnS:Cu and ZnS:Mn phosphors by trapping of drifting charge carriers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103:161113. doi: 10.1063/1.4825360

Chen, C., Zhuang, Y., Tu, D., Wang, X., Pan, C., and Xie, R.-J. (2020). Creating visible-to-near-infrared mechanoluminescence in mixed-anion compounds SrZn2S2O and SrZnSO. Nano Energy 68:104329. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104329

Chen, Q., Wu, J., Ou, X., Huang, B., Almutlaq, J., Zhumekenov, A. A., et al. (2018). All-inorganic perovskite nanocrystal scintillators. Nature 561, 88–93. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0451-1

Du, Y., Jiang, Y., Sun, T., Zhao, J., Huang, B., Peng, D., et al. (2019). Mechanically excited multicolor luminescence in lanthanide ions. Adv. Mater. 31:e1807062. doi: 10.1002/adma.201807062

Eliseeva, S. V., and Bunzli, J. C. (2010). Lanthanide luminescence for functional materials and bio-sciences. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 189–227. doi: 10.1039/B905604C

Hu, Z., Deibert, B. J., and Li, J. (2014). Luminescent metal-organic frameworks for chemical sensing and explosive detection. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 5815–5840. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00010B

Huang, B. (2016). Energy harvesting and conversion mechanisms for intrinsic upconverted mechano-persistent luminescence in CaZnOS. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 25946–25974. doi: 10.1039/C6CP04706H

Huang, B., Peng, D., and Pan, C. (2017). “Energy Relay Center” for doped mechanoluminescence materials: a case study on Cu-doped and Mn-doped CaZnOS. Phys. Chem. Phys. 19, 1190–1208. doi: 10.1039/C6CP07472C

Jeong, S. M., Song, S., Joo, K.-I., Kim, J., Hwang, S.-H., Jeong, J., et al. (2014). Bright, wind-driven white mechanoluminescence from zinc sulphide microparticles embedded in a polydimethylsiloxane elastomer. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 3338–3346. doi: 10.1039/C4EE01776E

Jiang, T., Zhu, Y. F., Zhang, J. C., Zhu, J., Zhang, M., and Qiu, J. (2019). Multistimuli-responsive display materials to encrypt differentiated information in bright and dark fields. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29:1906068. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201906068

Li, L., Wong, K.-L., Li, P., and Peng, M. (2016). Mechanoluminescence properties of Mn2+-doped BaZnOS phosphor. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 8166–8170. doi: 10.1039/C6TC02760A

Li, X., Cao, F., Yu, D., Chen, J., Sun, Z., Shen, Y., et al. (2017). All inorganic halide perovskites nanosystem: synthesis, structural features, optical properties and optoelectronic applications. Small 13:1603996. doi: 10.1002/smll.201603996

Li, X., Rui, M., Song, J., Shen, Z., and Zeng, H. (2015). Carbon and graphene quantum dots for optoelectronic and energy devices: a review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4929–4947. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201501250

Lian, L., Zheng, M., Zhang, W., Yin, L., Du, X., Zhang, P., et al. (2020). Efficient and reabsorption-free radioluminescence in Cs3Cu2I5 nanocrystals with self-trapped excitons. Adv. Sci. 7:2000195. doi: 10.1002/advs.202000195

Liu, J., Rijckaert, H., Zeng, M., Haustraete, K., Laforce, B., Vincze, L., et al. (2018). Simultaneously excited downshifting/upconversion luminescence from lanthanide-doped core/shell fluoride nanoparticles for multimode anticounterfeiting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28:1707365. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201707365

Liu, L., Xu, C.-N., Yoshida, A., Tu, D., Ueno, N., and Kainuma, S. (2019). Scalable elasticoluminescent strain sensor for precise dynamic stress imaging and onsite infrastructure diagnosis. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4:1800336. doi: 10.1002/admt.201800336

Meyer, J., and Tappe, F. (2015). Photoluminescent materials for solid-state lighting: state of the art and future challenges. Adv. Opt. Mater. 3, 424–430. doi: 10.1002/adom.201400511

Nishioka, S., Kanazawa, T., Shibata, K., Tsujimoto, Y., Zur Loye, H. C., and Maeda, K. (2019). A zinc-based oxysulfide photocatalyst SrZn2S2O capable of reducing and oxidizing water. Dalton Trans 48, 15778–15781. doi: 10.1039/C9DT03699G

Norberg, N. S., Kittilstved, K. R., Amonette, J. E., Kukkadapu, R. K., Schwartz, D. A., and Gamelin, D. R. (2004). Synthesis of colloidal Mn2+:ZnO quantum dots and high-TC ferromagnetic nanocrystalline thin films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9387–9398. doi: 10.1021/ja048427j

Olawale, D. O., Dickens, T., Sullivan, W. G., Okoli, O. I., Sobanjo, J. O., and Wang, B. (2011). Progress in triboluminescence-based smart optical sensor system. J. Luminesci. 131, 1407–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2011.03.015

Peng, B., Liang, W., White, M. A., Gamelin, D. R., and Li, X. (2012). Theoretical evaluation of spin-dependent auger de-excitation in Mn2+-doped semiconductor nanocrystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 11223–11231. doi: 10.1021/jp2118828

Peng, D., Chen, B., and Wang, F. (2015). Recent advances in doped mechanoluminescent phosphors. ChemPlusChem 80, 1209–1215. doi: 10.1002/cplu.201500185

Peng, D., Jiang, Y., Huang, B., Du, Y., Zhao, J., Zhang, X., et al. (2020). A ZnS/CaZnOS heterojunction for efficient mechanical-to-optical energy conversion by conduction band offset. Adv. Mater. 32:e1907747. doi: 10.1002/adma.201907747

Sang, J., Zhou, J., Zhang, J., Zhou, H., Li, H., Ci, Z., et al. (2019). Multilevel static-dynamic anticounterfeiting based on stimuli-responsive luminescence in a niobate structure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 20150–20156. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b03562

Scholze, F., Rabus, H., and Ulm, G. (1996). Measurement of the mean electron-hole pair creation energy in crystalline silicon for photons in the 50–1500 eV spectral range. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 2974–2976. doi: 10.1063/1.117748

Singh, S. K., Singh, A. K., and Rai, S. B. (2011). Efficient dual mode multicolor luminescence in a lanthanide doped hybrid nanostructure: a multifunctional material. Nanotechnology 22:275703. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/27/275703

Teng, L., Zhang, W., Chen, W., Cao, J., Sun, X., and Guo, H. (2020). Highly efficient luminescence in bulk transparent Sr2GdF7:Tb3+ glass ceramic for potential X-ray detection. Ceramics Int. 46, 10718–10722. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.01.079

Tsujimoto, Y., Juillerat, C. A., Zhang, W., Fujii, K., Yashima, M., Halasyamani, P. S., et al. (2018). Function of tetrahedral ZnS3O building blocks in the formation of SrZn2S2O: a phase matchable polar oxysulfide with a large second harmonic generation response. Chem. Mater. 30, 6486–6493. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02967

Tu, D., Peng, D., Xu, C.-N., and Yoshida, A. (2016). Mechanoluminescence properties of red-emitting piezoelectric semiconductor MZnOS:Mn2+ (M = Ca, Ba) with layered structure. J. Ceramic Soc. Japan 124, 702–705. doi: 10.2109/jcersj2.15301

Vink, A. P., de Bruin, M. A., Roke, S., Peijzel, P. S., and Meijerink, A. (2001). Luminescence of exchange coupled pairs of transition metal ions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148:E313. doi: 10.1149/1.1375169

Wang, C., Dong, L., Peng, D., and Pan, C. (2019). Tactile sensors for advanced intelligent systems. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2019:1900090. doi: 10.1002/aisy.201900090

Wang, C., Peng, D., and Pan, C. (2020). Mechanoluminescence materials for advanced artificial skin. Sci. Bull. 65,1147–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.03.034

Wang, X., Peng, D., Huang, B., Pan, C., and Wang, Z. L. (2019). Piezophotonic effect based on mechanoluminescent materials for advanced flexible optoelectronic applications. Nano Energy 55, 389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.11.014

Wang, X. D., Wolfbeis, O. S., and Meier, R. J. (2013). Luminescent probes and sensors for temperature. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 7834–7869. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60102a

White, M. A., Weaver, A. L., Beaulac, R., and Gamelin, D. R. (2011). Electrochemically controlled auger quenching of Mn2+ photoluminescence in doped semiconductor nanocrystals. ACS Nano 5, 4158–4168. doi: 10.1021/nn200889q

Withnall, R., Silver, J., Harris, P. G., Ireland, T. G., and Marsh, P. J. (2011). AC powder electroluminescent displays. J. Soc. Information Display 19:798. doi: 10.1889/JSID19.11.798

Xu, Z., Xia, Z., Lei, B., and Liu, Q. (2016). Full color control and white emission from CaZnOS:Ce3+,Na+,Mn2+ phosphors via energy transfer. J. Mater. Chem. C 4, 9711–9716. doi: 10.1039/C6TC03016E

Xu, Z., Xia, Z., and Liu, Q. (2018). Two-step synthesis and surface modification of CaZnOS:Mn2+ phosphors and the fabrication of a luminescent poly(dimethylsiloxane) film. Inorg. Chem. 57, 1670–1675. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b03060

Zak, P. P., Lapina, V. A., Pavich, T. A., Trofimov, A. V., Trofimova, N. N., and Tsaplev, Y. B. (2017). Luminescent materials for modern light sources. Russian Chem. Rev. 86, 831–844. doi: 10.1070/RCR4735

Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Tao, J., and Zhu, Y. (2018a). Study on the light-color mixing of rare earth luminescent materials for anti-counterfeiting application. Mater. Res. Express 5:046201. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aab7da

Zhang, J.-C., Wang, X., Marriott, G., and Xu, C.-N. (2019). Trap-controlled mechanoluminescent materials. Progress Mater. Sci. 103, 678–742. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2019.02.001

Zhang, J.-C., Zhao, L.-Z., Long, Y.-Z., Zhang, H.-D., Sun, B., Han, W.-P., et al. (2015). Color manipulation of intense multiluminescence from CaZnOS:Mn2+ by Mn2+ concentration effect. Chem. Mater. 27, 7481–7489. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b03570

Zhang, J. C., Pan, C., Zhu, Y. F., Zhao, L. Z., He, H. W., Liu, X., et al. (2018b). Achieving thermo-mechano-opto-responsive bitemporal colorful luminescence via multiplexing of dual lanthanides in piezoelectric particles and its multidimensional anticounterfeiting. Adv. Mater. 30:e1804644. doi: 10.1002/adma.201804644

Zhang, X., Zhao, J., Chen, B., Sun, T., Ma, R., Wang, Y., et al. (2020). Tuning multimode luminescence in Lanthanide(III) and Manganese(II) Co-Doped CaZnOS crystals. Adv. Opt. Mater. 8:2000274. doi: 10.1002/adom.202000274

Zhang, Z.-J., Feng, A., Chen, X.-Y., and Zhao, J.-T. (2013). Photoluminescence properties and energy levels of RE (RE = Pr, Sm, Er, Tm) in layered-CaZnOS oxysulfide. J. Appl. Phys. 114:213518. doi: 10.1063/1.4842815

Keywords: light emission, mechanoluminescence, multimode luminescence, X-ray, SrZn2S2O

Citation: Ma R, Mao S, Wang C, Shao Y, Wang Z, Wang Y, Qu S and Peng D (2020) Luminescence in Manganese (II)-Doped SrZn2S2O Crystals From Multiple Energy Conversion. Front. Chem. 8:752. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00752

Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 21 July 2020;

Published: 04 September 2020.

Edited by:

Guohua Jia, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Zhiguo Xia, University of Science and Technology Beijing, ChinaHai Guo, Zhejiang Normal University, China

Copyright © 2020 Ma, Mao, Wang, Shao, Wang, Wang, Qu and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dengfeng Peng, cGVuZ2RlbmdmZW5nQHN6dS5lZHUuY24=

Ronghua Ma1

Ronghua Ma1